Ferdinand Tönnies distinguished between "community" and "society". He believed, from the social connection perspective, that "community" and "society" are formulated based on people's essential will and arbitrary will. Community emphasizes the strong relationship between people who are living together permanently. Societies are formed based on diverse cultures and are typically characterized by weak relationships between people that are temporarily and superficially living together. Therefore, "community should be explained as a dynamic organism while society should be explained as mechanical togetherness and a man-made product" (Tönnies, 1999).

After experiencing industrialization and urbanization, the issue of whether or not communities exist has always been a focal point for dispute (Weber, 2006; Wirth, 1938; Gans, 1962, 1977; Suttles, 1968; Feng Gang, 2002; Wang Xiaozhang, 2002; Gui Yong, 2005; Gui Yong & Huang Ronggui, 2006). There are two main theories. One is "communities disappearing" which believes human groups that were small in size and mutually familiar, shared many things in common, and commonly existed in the pre-industrial society have disappeared with industrialization and urbanization (Weber, 2006; Wirth, 1938; Christenson, 1979; Baldassare, 1986; Cheng Yukun & Zhoumin, 1998), and instead of them are disembedded communities with frequent contact, while geographic communities are just neighborhoods (Wang Xiaozhang & Wang Zhiqiang, 2003; Gui Yong, 2005; Gui Yong & Huang Ronggui, 2006). The other idea is "communities existing" which believes social transition caused by urbanization did not cause urban communities to collapse and did not cause them to disappear, and residents in urban communities can make themselves become a safe base where mutual help can be provided and residents can connect with the external world (Gans, 1962, 1977; Suttles, 1968; Stacey, 1969; Fisher; 1976). In addition, there are also scholars studying the existence of communities based on moral needs from a "mutually beneficial" perspective (Feng Gang, 2002) and discussing whether or not communities should exist from the perspective of functionalism (Wang Xiaozhang, 2002).

However, from the view of the author, this dispute lacks strict logic and empirical data. For instance, the viewpoint of "communities existing" in China has not proved that communities exist and it just explains that after the unit system broke up, it urgently needed a functional substitute, which only explains communities exist, but does not provide logical proof for their existence. Furthermore, when studying the existence of communities from the perspective of moral needs, though the perspective is novel, it cannot be proved and it is also difficult to provide people with a clear understanding. Scholars with the theory of "disembedded communities" observe the relations between communities only in terms of economic relations and draw the conclusion that unlike the previous close relations that existed within the units to obtain resources and services, modern communities only have weak connections. In fact, this viewpoint mixes the difference between organization and community, so we cannot understand the disappearance of communities only from this perspective and need to analyze the social relations among people in communities instead.

This dispute has actually led to an area of misunderstanding. Ferdinand Tönnies (1999: 65) pointed out, "wherever people mutually connect and identify with each other based on their will and through organic ways is a community in certain ways". Therefore, the key point of the issue is not whether or not communities exist but what types of communities exist. To answer this question, we must first address what standards used to classify them. In other words, what dimensions we use to measure communities and different modes of the combination of these dimensions that form the basis of different types of communities.

This study tries to avoid the dispute of whether or not communities exist and proposes the concept of "community identity" which switches the focus to looking at what indicators should be used for measuring communities and distinguishing between different types of communities.

DIMENSIONS AND INDICATORS FOR "THE NATURE OF COMMUNITY"Before formulating the system for measuring "community identity", we determined three principles for selecting indicators: (1) Based on the strategy for analyzing empirical data, if there is an argument about the concept of "community identity" but indicator selection has something in common with indicator selection during previous empirical studies, then the indicator selection is applicable for this study. (2) As "community identity" is a new concept that the author brings up and there are not many articles about community characteristics, when referring to relevant issues the author takes several dimensions related to the influence of urbanization on communities as key variables for the study of community identity, because these dimensions are elements that can be used to judge communities. (3) Follow the principle of considering the whole picture and keeping things simple. Under permitted conditions, the author uses several dimensions to measure "community identity" in order to ensure the scale has an enhanced structural validity. To ensure the feasibility of research, the dimensions should not be too complex.

After reviewing relevant research works on communities, the author concludes the following five dimensions are important when looking to measure "community identity".

Sense of Community Identity and BelongingFerdinand Tönnies (1999: 65) classified communities into three types: kinship community, geographic community and spiritual community. According to his classifications, urban communities can only be classified as geographic communities. However, at that time the only geographic communities he saw were village neighborhoods where people had land next to each other which ensured people had frequent contact, were familiar with each other and become accustomed to one another. People also had mutual work, rules and administration and even shared the same gods in their faith (Tönnies, 1999: 66). However, in current urban communities, except for living in closer proximity, people have no mutual means of production, do not work together and do not share the same gods in their faith. Then can communities like this be described as actual communities? In the opinion of Ferdinand Tönnies, community is a unity of people's will and is a primitive or natural state. Mutual relationships between people are natural and unconscious relationships in life. Human wills, each one housed in a physical body, are related to one another by descent, gender and kinship (Tönnies, 1999: 58). When describing people's internal will in relation to community, he named it "essential will". 1

1. "Essential will" is opposed to "arbitrary will". "Arbitrary will" refers to a behavioral model based on rational judgment for a group to achieve a goal. The distinction between the two is a key element to determine whether a grouping is a community or society.

Max Weber also had a penetrating analysis. He pointed out that under special circumstances, the average situation or pure mode, as long as the society is based on social action and participants have the feeling (emotional or traditional) that they belong to a unity, it should be referred to as a "community". If social action is rationally-driven through an equitable share of profits (value rational or instrumentally rational) or is a rationally-driven profitable relationship, then the social relation should be called a "society" (Weber, 2000: 62). Obviously, Max Weber did not take into account the objective basis of social relations, and rather than looking at kinship, industry or professional division of labor, what he cared more about was whether the overall feelings of participants are emotional or rational feelings.

The above description shows that if you want to determine a community, you have to find indicators that can reflect the "essential will" of residents. In the author's opinion, according to existing empirical studies, the indicator that can most directly reflect the essential will is "sense of community identity and belonging". First, it directly reflects people's feelings towards their community and this emotion is not "arbitrary will" but "essential will". Second, the indicator is frequently used in empirical studies and this is in line with the first principle for the selection of indicators.

FamiliarityIn the 1930s, there were scholars that paid attention to the influence of urbanization on people's lifestyles because the influence directly pointed at the existence of communities. The author takes the influence as an important dimension to measure "community identity".

L. Wirth proposed three important variables that influence urban people's way of life, namely population size, population density and population heterogeneity. In his opinion, an increase in population strengthens the heterogeneity between people including differences in occupation, culture and mindset and such differences will make a community far from a homogeneous community (Wirth, 1938). On the contrary, if the homogeneity of residents in a community is high, the community is more like a homogeneous community. Increases in the size, density and heterogeneity of a population leads to people having less contact with each other and fewer primary groups, with people mostly having contact with secondary groups. People become mutually unfamiliar, each person plays different social roles and between them they become dehumanized and only have superficial social relations. Therefore, familiarity is an important indicator to determine a community.

According to the viewpoint of "community existing", H. Gans (1977) proposed that urbanization has led to colorful ways of life but not a single way of life that was pointed out by L. Wirth. When urban communities experience pressure, opportunity and restriction from extensive social transition, the inevitable outcome is diversified lifestyles and ways of operating in communities and this diversification is closely related to diversified choices and needs of residents in communities. Suttles (1968) also drew similar conclusions through studies that social transition caused by urbanization did not cause urban communities to collapse and did not cause them to disappear, and through residents, urban communities can make themselves become a safe base where mutual help can be provided and residents can connect with the external world. Therefore, it is easy to see through studies by H. Gans et al that although they admit the diversified residential status of urban communalities, they do not think this will lead to the collapse of communities and on the contrary believe it can help to satisfy diversified needs in communities.

However, their difference is the influence of the size, density and heterogeneity of population on communities, but familiarity is at the core. Therefore, we need to pay attention to this variable because it is used to directly determine community identity.

TrustTrust in the community is always an important issue in community studies. In the author's opinion, it reflects the degree of trust between residents in communities which is consistent with the spontaneous feeling required in the original meaning of community. In addition, on a deeper level it reflects the relationship between people in communities, which surpasses a simple sense of identity and belonging and mutual interaction.

In the previous studies, trust refers to internal trust within an organization or is understood as one dimension of social capital. However, in the author's opinion, this does not prevent it from becoming an indicator for measuring community identity, because in a certain sense a community is an organization which does not refer to an organization in economics that is organically united to achieve mutual objectives, but an organization that is mechanically united. To a certain extent, community reflects social capital, particularly collective social capital.

Therefore, trust reflects one dimension of community and is hereby used as an indicator for community nature.

CohesionTo determine a community, we not only need to observe residents' sense of community belonging, mutual familiarity and degree of trust, but also the need to measure if residents can harmoniously get along with each other without conflict. Residents in a community may have a strong sense of community identity and high familiarity, but conflict is likely to exist between them and sometimes may be prominent. For instance, conflicts regarding benefits may appear more obvious.

When measuring social capital "cohesion" is usually used to find the degree of harmony in a community (De Silva, 2006; Gui Yong, 2008). In the author's opinion, communities should have a high degree of harmony which reflects a degree of friendliness between residents in communities. Therefore, it can be used as a dimension for measuring "community identity".

ParticipationIn the 1950s, some scholars responded to L. Wirth's urbanization and proposed other factors that influence urbanization. Bell et al (Bell & Boat, 1957) pointed out that L. Wirth neglected the fact that different areas in cities have different conditions and may experience different influences from urbanization. They analyzed the difference in community participation by people in cities from different families and with different economic status. S. Greer (1956) further pointed out that in the past only economic and ethnic differences were analyzed when searching for influences from urbanization without analyzing the influence generated in areas with similar economic status and ethnic groups. Therefore, he analyzed the influence of urbanization on community participation by residents.

Since whatever factors are used to explain different influences from urbanization, "participation" is persistently used to determine influences from urbanization, i.e. to explain whether or not communities have collapsed. This shows "participation" can be used as another indicator for measuring "community identity" which is in line with the second principle for selecting indicators. In the author's opinion, participation represents a high degree of community identity, because previously mentioned dimensions focus on the sense of identity and belonging of residents or mutual familiarity and interaction, but actions of residents are not naturally derived. Participation fills in the gaps. In Table 1, we can clearly and directly see the five aforementioned dimensions and relevant theories and meanings.

| Table 1 Five Dimensions to Measure "community identity" |

The above dimensions are not simply put together, but have a consistent logic. You can say it is a continuous process from individual to community, from interaction to trust, and from mindset to action. When talking specifically, sense of community identity and belonging measures the feeling of individuals towards the whole community, familiarity measures the frequency of contact between people, and trust refers to the deep trust held in people's minds.

Can this relationship be upgraded to collective action? First, we need to consider community cohesion and see whether residents in a community have the potential to be effectively organized. Then we can analyze whether or not residents actually participate in community activities. Therefore, the scale is a united process from external to internal and from low level to high level. None of these dimensions are dispensable. After having determined the dimensions for "community identity", based on relevant existing research works and China's actual conditions, the author designed complete measurement indicators (see Table 2).

| Table 2 Specific Indicators for Measuring "community identity" |

Because previously there were no methods for directly measuring "community identity", we referred to methods for measuring other similar concepts. Take the methods used for measuring "social capital in a community" (Onyx & Bullen, 2000; Gui Yong & Huang Ronggui, 2008) for instance, "social capital in a community" is a community stratification level concept that is usually measured by first collecting individual data and then gathering together all the data before finally obtaining indicators.

Similarly, "community identity" is also a community-level concept. After individual data is collected, analysis of the collective dataset is carried out. Although the data is not used to directly measure community-level, it is easy to obtain and is reliable. If the sample size is large enough and random sampling is adopted, this method of collection is acceptable. Although community-level measurement can avoid ecological fallacy, indicators obtained are usually imprecise which will influence the validity of data.

This study takes Shanghai urban communities as a whole to test the aforementioned scale for "community identity". Community in this study is defined as a basic residential unit for urban residents in China, because such units are areas that can form a closed community in terms of psychology, behavior and daily interaction. Grassroots organizations (such as property owner committees and community activity groups) that are spontaneously formed can prove this, which show that a sense of identity and belonging, frequent interaction and community activities can be formed in communities.

The data for this study was collected in 2006 and 2007. The survey was carried out by making home visits to families and asking them to complete the questionnaire. The surveyed people were permanent Shanghai residents aged over 18 (people with a registered residence outside Shanghai must have been in Shanghai for six months). The survey used the following order "district-street-residents' committee-family-interviewed person" to randomly select samples and interviewers ultimately determined who would be interviewed based on random data confirmed by the study team. 52 communities were finally selected and 1, 720 valid samples were obtained, amongst which males accounted for 47.45% and females accounted for 52.55%; married people accounted for 72.2% and single people accounted for 27.7%; people aged 18-40 accounted for 41.0%, those aged 40-60 accounted for 40.1% and those aged over 60 accounted for 18.9%.

In the author's opinion, "community identity" refers to characteristics of community and is a collective concept. Therefore, when analyzing scales for measuring "community identity", the unit is community. The author gathered all indicators for measuring individual data to be used for community measurement then calculated the mean score of each indicator for each community, and then carried out exploratory factor analysis. Factor analysis adopts the maximum likelihood estimation method and determines the number of factors based on the principle that the eigenvalue is more than 1. After abstracting factor loadings matrix, varimax rotation was used to clarify the structure and meaning of the factor loadings matrix. After having determined indicators of dimensions for "community identity" based on factor analysis results, the author tested the "community identity" scale's reliability and validity.

In addition, the formation of the scale provides a basis for us to further classify communities. The author then classified the surveyed communities into several types and analyzed their characteristics.

ANALYSIS OF DATA IN THE SCALE FOR "THE NATURE OF COMMUNITY" Factor Analysis11. In order to improve factor analysis, the author appropriately adjusted the values for the questions in the scale. First, the values for the first question in the "trust" dimension are from high to low whereas the values for other variables in the scale are from low to high, so it needed to set the values again in reverse and deleted the "Don't know" responses (93 people answered "Don't know" in the tr1, accounting for 5.42%; 341 people answered "Don't know" in the tr3, accounting for 19.88%). Second, the values that were 1 or 2 were reassigned the values 2 or 4 to ensure the mean value would be near 3 which approaches the mean value of five-point scale; values that were 4 for items in the pa2 remained the same. Last, continuous variables were cut into variables with five values based on the principle of equal proportions to make the values consistent. All of these adjustments would facilitate factor analysis.

The scale designed in the study has 25 items. A database was obtained after gathering information from each community and taking mean scores and then exploratory factor analysis was carried out on the 25 items. Based on the principle that the eigenvalue is more than 1, 7 factors were abstracted (see Table 3) and 77.6% of the variance was explained.

| Table 3 "Community Identity" Factor Loadings Matrix |

Although certain items have overlapping meanings and are presented as loadings on two factors, for instance, Tr1 shows high loadings on factor 5 (0.532) and factor 6 (0.543), but the whole structure is clear and the meaning is also clear.

According to results of the factor analysis, the author adjusted the original scale structure and changed it into 7 dimensions respectively named "familiarity" (Factor 1), "sense of community identity and belonging" (Factor 2), "feeling of common interests" (Factor 3), "mutual help" (Factor 4), "cohesion" (Factor 5), "participation" (Factor 6) and "trust" (Factor 7). Compared to the original design, we can see: (1) "Sense of community identity and belonging" is divided into "sense of community identity and belonging" and "feeling of common interests"; (2) The 8 indicators for measuring "familiarity" are divided into two parts: the first six indicators load on "familiarity" and the last two indicators load on "mutual help"; (3) For the three indicators originally designed for measuring "trust", because the first indictor Tr1 ("Generally speaking, do you believe most residents are trustworthy or you should be more careful when in contact with other residents") loaded on "participation", this was put together with the two indicators that measure "participation"; (4) Pa3 loaded Factor 4 (mutual help), so its code was changed. See Table 3 for changes to codes for items.

Validity AnalysisScale validity usually has three types: construct validity, content validity and criterion validity. For criterion validity, we need to select an indicator or test tool based on existing theories to analyze the relationship between the scale and criterion. Because it is difficult to find theories and test indicators relevant to "community identity" in this study, the criterion validity test has not been implemented. However, this does not imply the scale has low validity but there are probably no other better test models to support it. Therefore, the author carried out analysis of the other two validity tests, namely construct validity and content validity.

Construct validity tends to test the correlation between the final structure shown and measured values. The ideal method for this is factor analysis which looks at whether or not the results of factor analysis correspond to the measurement dimensions originally designed by the author. It is easy to see in Table 3 that the results of factor analysis not only fully include the five dimensions originally designed by the author, but also generate another two dimensions (feeling of common interests and mutual help) that have clear meanings and can reflect "community identity". In terms of indicators from factor analysis that reflect construct validity, the factor loading for each test item is high (basically between 0.6-0.9) and the cumulative variance explained or cumulative contribution rate reaches 77.6% which can be considered to be relatively high (see Table 3). The cumulative contribution rate reflects the cumulative degree of validity of common factors towards the scale, so these indicators can reflect the high construct validity of the scale.

Content validity is also referred to as face validity or logical validity. Logic analysis and statistical analysis are usually used to determine it. The "community identity" scale in this study is obtained based on existing theories, which has several different but consistent measurement dimensions. The measured content is a continuous process from individual to community, from interaction to trust, and from psychology to action. Therefore, it has a consistently strong logic. In terms of statistical analysis, a frequently used indicator for testing content validity is correlation coefficient, i.e. the coefficient for the correlation of the score for each item and total scores. We can see from Table 4 that most correlation coefficients are high and significant. This shows most test items can effectively reflect the content that the scale needs to measure and the content is consistent. Although correlation coefficients for some items are relatively low, they are acceptable from the perspective of the entire content of the scale.

| Table 4 Indicators for Measuring "Community Identity" (modified version) |

In the author's opinion, there are two steps required to complete reliability analysis. Step 1 is to analyze the indicators for each dimension to obtain the Cronbach's alpha for each dimension and then observing if the indicators for each dimension can stably and consistently reflect the dimension. Step 2 is to observe the reliability for the seven dimensions as a whole and see if they can stabalize and consistently reflect the concept of "community identity" (see Table 4).

We can see from Table 4 that the Cronbach's alpha is distributed between 0.550-0.915. Though the coefficients for trust and participation are only 0.550 and 0.562 respectively, they are acceptable. This shows that the selected indicators have a consistently strong logic and the measurement is stable. From the perspective of the whole scale, Cronbach's alpha obtained from the standard item is 0.852, which shows it is stable when using the whole scale to measure the concept of "community identity".

CLASSIFICATION OF COMMUNITIES BASED ON "THENATURE OF COMMUNITY"After the formulation of the scale and testing for its validity and reliability, we believe using the scale can measure the concept of "community identity".

One of the important purposes for formulating the scale for "community identity" is to classify communities. There have been classifications of communities in previous studies, for instance, based on the structure and characteristics of communities they have been classified into rural communities and urban communities; based on community functions, communities have been classified into agricultural communities, industrial communities, military communities and cultural communities; based on community formulation, system communities have been classified into geographical communities, occupational communities and interest-based communities (Shi Hao, 2001). In addition, there are also scholars that have classified communities based on existing survey data and research into traditional neighborhoods, government-owned residential communities, commodity housing communities for residents with high incomes, commodity housing communities for residents with low to medium incomes and marginal communities, and made detailed comparisons in terms of the year when the community was established, spatial characteristics, facilities, management approach and the characteristics of residents (Wang Ying, 2002).

However, these classification methods did not take into account the core characteristic of community being an "integrated whole". While this study tries to resolve the disputes on communities, it also tries to fill in the gap of community classifications. Therefore, the author classified communities according to the dimensions for "community identity".

Based on factor scores for the 7 dimensions in the scale for "community identity", the author tried to carry out cluster analysis on these communities and classify them. However, if the 7 dimensions were used for cluster analysis, too much information would be hidden and complex classifications would arise from different combinations. It is not a case of the more variables are added, the better the cluster analysis is, because the addition of one or two inappropriate variables will cause quite different classifications (Zhang Wentong, 2002). Therefore, we need to reduce the dimensions and choose the dimensions that have the strongest explanatory power and are the most important. The author selected the first three dimensions that have the strongest explanatory power (familiarity, sense of community identity and belonging, and feeling of common interests) and they together explained 44% of the variance. Before cluster analysis is carried out, we need to determine whether or not these variables are suitable for cluster analysis.

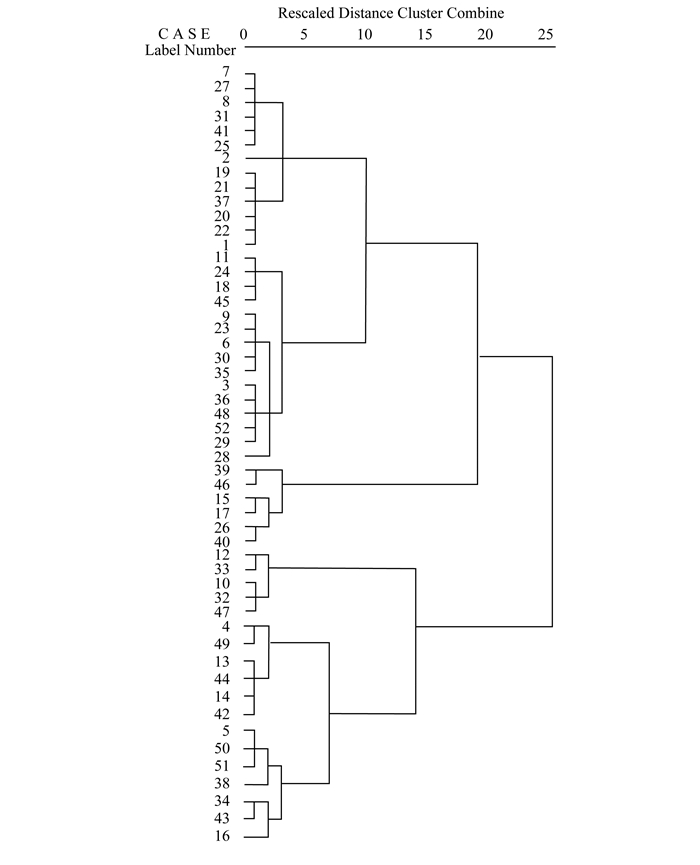

After further analysis, the author discovered they were suitable for cluster analysis because the factor values for the three dimensions are not correlated with clear differences for different individual cases and these values have been standardized. Therefore, this study adopted Hierarchical Cluster Analysis. To gauge the distance measure, several methods such as the shortest distance method and the longest distance method were tried. After making comparisons, Ward's method was considered to be the best-see Figure 1 for the detailed clustering process.

|

Figure 1 Ward's Method: Community Dendrogram |

After classification and removing the singular value "2", according to the distance in the cluster analysis the remaining 51 communities were classified based on the three dimensions for "community identity". See the classifications of communities in Table 5.

| Table 5 Community Classifications |

Based on the classifications in Table 5, the author clustered together the same types of communities and specifically analyzed the characteristics of each type and ultimately named the type from the perspective of "community identity". First, the scores for the three factors used to classify communities were divided and the score for each factor was divided into three ranges (high, medium and low). Then according to the classifications in Table 5, the author determined which range the mean factor score for each type was in and further determined the characteristics of different types of communities that were classified through cluster analysis (see community types in Table 6).

| Table 6 Characteristics of Communities |

In order to further understand each type of community, the author specifically analyzed the average satisfaction, average personal and family monthly income, education, occupation, housing type, average age, average period of residence, job position, company type and property ownership type (see Table 6).

Based on the personal and family monthly income shown in Table 6, we can tentatively classify communities into high, medium and low end communities. The fifth and sixth types of communities can be considered as high end communities while the first, second and fourth types of communities can be considered as medium end communities, with the third type of community as the low end communities. From the period of residence we can see that the average period of residence for high end communities is short (around four years), around 10 years for medium end communities except for the fourth type of community, and low end communities have the longest period of residence (around 17 years). The author renamed the six types of communities according to what they show in the dimensions for "community identity" (see Table 7).

| Table 7 New Names for Communities |

According to the classifications and names, the author analyzed the characteristics of these communities.

In terms of education, we discovered that in high end communities (communities where residents have a weak sense of belonging and close-knit communities) residents with an education of university and above account for about 50%, but the percentage is only around 20% in medium and low end communities with most residents having an education of senior high school or below.

It should be noted that the percentage of residents with an education of senior high school and below in "communities with high familiarity between residents" is the highest (75.2%) and the average age of residents in these communities is 49.7 (see Table 7), and most residents in these communities are jobless or retired, accounting for 55% which is higher than that in the two types of high end communities (around 30%) and three types of medium end communities (around 40%). These communities mainly consist of old low-rise housing which accounts for 85% of all housing types (see Table 8). This shows residents in communities that consist of old low-rise housing have low levels of education, are old, and their familiarity and sense of community identity and belonging are high, which is consistent with the previous knowledge of communities.

| Table 8 Educational Background, Housing Type and Property Ownership Type Distribution in Different Types of Communities |

It is interesting to note that in terms of housing types, if we believe the fact that around 85% of old low-rise housing is seen in "communities with high familiarity between residents" is one of the important reasons that residents in such communities have high familiarity, then why do 81% of "communities where residents show no concern for each other" also consist of old low-rise housing? The author believes there must be other factors that affect the emergence of "communities where residents show no concern for each other". It is difficult to distinguish between the two types of communities in terms of average period of residence (both around 17 years) and average age (both around 48) and even occupations. However, the author found some clues when looking at property ownerships (see Table 8). The percentage of sold off government housing in "communities where residents show no concern for each other" is 20% higher than "communities with high familiarity between residents", while the percentage of government-owned dwellings in "communities with high familiarity between residents" is 15% higher than "communities where residents show no concern for each other", and its percentage of old private houses is also high. This shows the level of "community identity" for communities that consist of old government housing is high, but once government houses are sold, neighbors may have less contact and are no longer old neighbors. In other words, residents in the communities that consist of government housing probably used to be colleagues working in the same work unit and were mutually familiar, but the new owners of these houses are people from different places who are mutually unfamiliar. However, this is just a hypothesis and requires further empirical data to support it.

There is also another pair of data sets that can be compared, both are high end communities, why is one type "close-knit communities" and the other "communites where residence have a weak sense of belonging, " have a relatively low level of "community identity"? In the author's opinion, it is difficult to distinguish between the two types of communities only in terms of the average period of residence (both around 4 years), average age (both around 42) and education (similar distribution, see Table 8). However, the author found some clues when looking at property ownership. In terms of housing type, "close-knit communities" consist of 13% of Lilong housing which is a two-story building that houses more than one family, whereas "communities where residents have a weak sense of belonging" have no such housing. Residents in the 13% of Lilong housing are probably one reason that strengthens "community identity".

In addition, we should compare the first two types of medium end communities where residents both exhibit a strong feeling of common interests and low familiarity. Their main difference is in terms of the sense of community identity and belonging, with that for the first type of communities being strong and for the second type of communities being weak, but generally the sense of community identity and belonging for both of the types of communities are weak. This is reflected in: first, for communities where residents have a strong sense of community identity and belonging, average family monthly income is RMB 1, 200 higher than the other type of communities and average personal monthly income is RMB 400 higher; second, in terms of housing type, the percentage of old low-rise housing in medium end communities where residents have a weak sense of belonging is around 30% higher than medium end communities where residents have a strong sense of belonging, but the percentages of new low-rise housing and high-rise housing in communities where residents have a strong sense of belonging are respectively 20% and 10% higher than those in communities where residents have a weak sense of belonging. This shows residents that live in new low-rise housing and high-rise housing have a stronger sense of community identity and belonging than those that live in old low-rise housing.

CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSIONThe author has discovered that most studies on communities question whether or not communities exist in contemporary cities and few studies specifically focus on the empirical measurement of communities. As long as a group of people live together in the same area for a period of time, a community will form. The author calls it "community identity". The issue is not whether or not communities exist in contemporary cities, but in what ways they exist.

Community classifications in this study are based on sample data from a survey carried out in Shanghai. One possible problem is the sample data does not include all types of communities such as communities where the transient population lives. Of course, community types in Shanghai cannot cover all community types in all of China's cities. However, these classifications are a useful attempt to do so. More importantly, this attempt has changed the ingrained views towards community studies and how we can raise questions, and extend away from the areas of misunderstanding.

Based on the above knowledge, future work in this field will focus on formulating more effective measurement tools, using different data and methods to test reliability and validity, and improving measurement systems. In addition, community types can be supplemented through measurement data from different areas to make up for the limitation of regional data. After improvements are made through several empirical studies, the measurement system for "community identity" will gradually become more stable and community classifications will become more clear and more accurate.

Baldassare, Mark. 1986. "Residential Satisfaction and the Community Question." Socilology and Social Research 70(2): 139-142. |

Bell, et al.. 1957. "Urban Neighborboods and Informal Social Relations." American Journal of Sociology 4. |

Cheng, Yushen and Min Zhou. 1998. "Review for International Studies of Urban Communities." Sociological Studies 4. [ 程玉申, 周敏. 1998. 国外有关城市社区的研究评述. 社会学研究, 4(4).] |

Christenson, James A.. 1979. "Urbanism and Community Sentiment: Ectending Wirth's Model." Social Science Quarterly 60(3): 384-400. |

De Silva, Mary. 2006. "System Review of the Methods Used in Studies of Social Capital and Mental Health. " In Social Capital and Mental Health, edited by Kwame McKenzir & Trudy Harpham. London: Jessica Kingsley Publisher.

|

Dong, Hui and Liya Hu. 2000. "Direction for the Cultural Development of Urban Communities." Society, (2). [ 董卉, 胡丽亚. 2000. 城市社区文化建设的方向. 社会, (2).] |

Feng, Gang. 2002. "How Do Modern Communities Come into Existence?." Zhejiang Academic Journal, (2). [ 冯钢. 2002. 现代社区何以可能. 浙江学刊, (2).] |

Fischer, C.S.. 1976. The Urban Experience. New York: Harcourt.

|

Gans, H. J. 1977. "Urbanism and Sub-Urbanism as Ways of Life: A Re-Evaluation of Definitions. " In American Urban History (2nd ed. ). Edited by Callow, A. B. Jr. London: Oxford University Press: 507-521.

|

Gans, H.J.. 1962. The Urban Villagers. New York: Free Press.

|

Greer, S.. 1956. "Urbanism Reconsidered: A Comparative Study of Local Areas in a Metropolis." American Sociological Review 1. |

Gui, Yong and Ronggui Huang. 2006. "Urban Communities: Communities or 'Isolated Neighborhoods'." Journal of Central China Normal University, (6). [ 桂勇, 黄荣贵. 2006. 城市社区:共同体还是互不相关的邻里. 华中师范大学学报, (6).] |

Gui, Yong. 2005. "Is It Possible for Urban Communities: Comparative Analysis of Rural Neighborhoods and Urban Neighborhoods." Journal of Guizhou Normal University, (6). [ 桂勇. 2005. 城市社区是否可能?关于农村邻里空间与城市邻里空间的比较分析. 贵州师范大学学报, (6).] |

Ladewing, H. and G.C. McCann. 1980. "Community Satisfaction: Theory and Measurement." Rural Sociology 45: 110-131. |

Li, Tingyu. 2001. "Community Development and Participation by Residents." Hubei Social Sciences, (12). [ 李婷玉. 2001. 社区发展与居民参与. 湖北社会科学, (12).] |

Li, Wei. 2001. "Fostering a Sense of Community Belonging." Dongyue Forum, (2). [ 李炜. 2001. 论社区归属感的培育. 东岳论坛, (2).] |

Ma, Weihong, Qinlei Huang and Yong Gui. 2000. "Analysis of Factors that Influence Participation of Shanghai Residents." Society, (6). [ 马卫红, 黄沁蕾, 桂勇. 2000. 上海市居民参与意愿影响因素分析. 社会, (6).] |

Stacey, M.. 1969. "The Myth of Community Studies." British Journal of Sociology 20: 134-146. DOI:10.2307/588525 |

Suttles, G.D.. 1968. The Social Order of the Slum: Ethnicity and Territory in the Inner City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

|

Tönnies, Ferdin. 1999. Community and Society. Beijing: The Commercial Press. [ 滕尼斯. 1999. 共同体与社会. 北京: 商务印书馆.]

|

Wang, Chunguang. 2002. "Control or Gather: Thoughts on Current Community Development." Zhejiang Academic Journal, (2). [ 王春光. 2002. 控制还是聚合?对当前社区建设的几点反思. 浙江学刊, (2).] |

Wang, Xiaozhang and Zhiqiang Wang. 2003. "From Communities to Disembedded Communities: Modern Communities and Community Development." Academic Forum, (6). [ 王小章, 王志强. 2003. 从社区到脱域的共同体:现代性视野下的社区和社区建设. 学术论坛, (6).] |

Wang, Xiaozhang. 2002. "What Are Communities and What Do They Do?." Zhejiang Academic Journal, (2). [ 王小章. 2002. 何谓社区与社区何为. 浙江学刊, (2).] |

Weber, M.. 2006. Economy and Society. Beijing: The Commercial Press. [ 韦伯. 2006. 经济与社会. 北京: 商务印书馆.]

|

Wirth, L. 1938. "Urbanism as a Way of Life. " In Cities and Society, edited by P. Hatt & A. J. Jr. Reiss. Glencoe: The Free Press: 46-64.

|

Zhang, Wei. 2001. "Community Participation: Driving Community Development: Case Study of Suojin Village Community in Nanjing." Society, (1). [ 张卫. 2001. 社区参与:社区建设与发展的推动力--对南京市锁金村社区的个案分析. 社会, (1).] |

Zhang, Wentong. 2002. Teaching Course for SPSSⅡStatistical Analysis. Beijing: Beijing Hope Electronic Press. [ 张文彤. 2002. SPSSⅡ统计分析教程. 北京: 北京希望电子出版社.]

|

2011, Vol. 31

2011, Vol. 31