扩展功能

文章信息

- 莫秀洪, 莫麒颖, 卢宪旺, 关洪武, 张卫兵, 孙宝军, 冀贺莲, 田雅慧, 赵大鹏

- MO Xiuhong, MO Qiying, LU Xianwang, GUAN Hongwu, ZHANG Weibing, SUN Baojun, JI Helian, TIAN Yahui, ZHAO Dapeng

- 天津盘山风景名胜区人类干扰对野生动物活动节律影响的初步研究

- Preliminary Study on the Influence of Human Disturbance on the Activity Rhythm of Wild Animals in the Tianjin Panshan Scenic Spot

- 四川动物, 2022, 41(1): 30-41

- Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2022, 41(1): 30-41

- 10.11984/j.issn.1000-7083.20210150

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2021-04-25

- 接受日期: 2021-11-10

2. 中国天津盘山风景名胜区管理局,天津 301900

2. Tianjin Panshan Scenic Spot Administration Bureau, Tianjin 301900, China

人类与野生动物的共存关系是人与自然关系的一个重要方面(赵广华等,2013; 黄雯怡,2020),也是当今保护生物学领域热点研究方向之一(郑华等,2003; Webb & Blumstein,2005; Gill,2007; 蒋志刚等,2016)。开发利用自然资源、扩张活动范围等人类活动对野生动物的生存产生了潜在影响(Miller et al., 1998; Beale & Monaghan,2004; Lamb et al., 2020)。蒋志刚等(2016)研究发现,中国被列为“极危”的哺乳动物物种所受威胁中有23%的威胁因子来自人类干扰。不同形式的人类干扰不同程度影响着野生动物的取食方式、行为节律、自然分布、生境选择、种群数量、繁殖策略等方面(Knight & Fitzner,1985; Burger & Gochfeld,1998; 刘建泉,杨建红,2004; 刘子成等,2012)。

面对人类干扰,部分野生动物会在生理(Schoech et al., 2004)、形态(Møller,2009)、遗传(Carrete & Tella,2017)、行为(Gaynor et al., 2018)等方面产生响应表达。在行为响应表达方面,首先,野生动物会调整自身时空活动节律(Kaartinen et al., 2005),来自欧洲等6大洲的62种哺乳动物在人类干扰频繁区域的夜间活动增加了1.36倍(Gaynor et al., 2018),西班牙城市公园的欧亚乌鸫Turdus merula通过改变自身栖息地空间以应对人类访客(Fernández-Juricic et al., 2001); 其次,野生动物会调整对人类干扰的耐受性,一些鸟类城市化的时间越长,其对人类干扰的耐受程度就越高(Samia et al., 2015),美洲绿鹭Butorides virescens在人类干扰不规律和不频繁的地点会改变觅食行为,而在人类干扰较规律的地点可能会选择忍耐(Moore et al., 2016); 再次,野生动物会改变鸣叫节律以应对人类干扰带来的噪音,新疆歌鸲Luscinia megarhynchos在工作日的鸣叫音量高于周末(Brumm,2004),欧亚大山雀Parus major在嘈杂的环境下可能会因为同伴无回应而不再重复或删除某些特定的鸣叫音律(Slabbekoorn & Ripmeester,2008)。

自20世纪90年代以来,红外相机技术逐渐广泛被应用于我国野生动物资源多样性调查和保护研究工作(李晟等,2014)。本研究基于红外相机技术,选择天津盘山风景名胜区为研究地点,重点关注人类干扰对野生鸟类和哺乳类活动节律的影响效应,比较分析其季节和海拔差异,并探究不同强度人类干扰对野生动物活动节律的影响,为天津自然保护地野生动物资源综合保护管理以及人与自然和谐共存提供科学参考依据。

1 研究方法 1.1 研究地概况天津盘山风景名胜区位于天津市蓟州区城西12 km,坐落于燕山南麓,雄踞于燕山山脉与华北平原的分界点,总面积110.9 km2。地势北高南低,最高峰挂月峰864.4 m; 属于暖温带季风型气候,四季分明,年降水量800 mm左右; 主要植被类型包括针叶林、阔叶林、针阔混交林等(张宇硕等,2021)。

1.2 相机布设与数据收集基于GIS将天津盘山风景名胜区整体划分为1 km×1 km的监测网格,从中选取40个网格,优先在每个网格中心位置布设1台红外相机(型号:BG526),具体布设位点结合实际山形地貌特点和野生动物活动痕迹。红外相机选择安装于合适的树干或岩石上,距离地面高度约0.5 m,可适当增加倾角或俯角; 参数设置为1 s的拍摄间隔、3张连拍、中度敏感度等。监测时间为2019年7月—2020年8月,每3个月进行一次维护,包括置换电池和存储卡。

1.3 数据分析根据研究区域气候特点划分季节:春季3—5月,夏季6—8月,秋季9—11月,冬季12月至翌年2月。监测区域划分为4个海拔区段:海拔区段Ⅰ(50~249 m)、海拔区段Ⅱ(250~449 m)、海拔区段Ⅲ(450~649 m)和海拔区段Ⅳ(650~849 m)。根据《中国兽类野外手册》(Smith,解焱,2009)、《中国哺乳动物多样性及地理分布》(蒋志刚,2015)和《中国鸟类分类与分布名录》(郑光美,2017)鉴定鸟类与哺乳类和确定鸟类的居留方式。

相对多度指数(relative abundance index,RAI)的计算公式如下:RAI=Ai/T×100,其中,Ai代表第i类(i=1, 2, ……, n)动物的独立有效照片数,T代表每个位点相机总的有效监测日(Ohashi et al., 2012, 潘秋荣等,2019)。独立有效照片为同一相机位点含同种个体的有效照片,且间隔时间至少为30 min(O'Brien et al., 2003)。为比较季节差异,选择RAI前5位的留鸟和哺乳类进行数据分析。将人类RAI>0的位点定义为有人类干扰位点区域,将人类RAI=0的位点定义为无人类干扰位点区域。以RAI=1为界限,将存在人类干扰的位点分为高强度人类干扰区域(RAI≥1)与低强度人类干扰区域(RAI<1)。采用各时间段相对丰度指数(time period relative abundance index,TRAI)描述全天候人类干扰和野生动物活动节律的特征(Azlan & Sharma,2006; 陈向阳等,2019): TRAI= Tij/Ni×100,其中,Tij代表该区域内第i类动物或人类干扰在第j个时间段(j=1, 2, …, 12,以每2 h为一个时间段)的有效照片数; Ni代表第i类动物的独立有效照片总数,采用Origin 2021绘制人类干扰和动物活动节律折线图。

应用SPSS 26.0中的Friedman检验和Wilcoxon检验分析人类干扰的季节差异。应用Kruskal-Wallis H检验和Mann-Whitney U检验分析人类干扰的海拔差异。应用R x64 4.0.2中的activity包和overlap包分析在有人类干扰位点区域与无人类干扰位点区域之间的鸟类和哺乳类的活动节律差异(Ridout & Linkie, 2009)。

2 研究结果 2.1 物种多样性与人类干扰的季节和海拔差异共获得有效照片14 942张,其中独立有效照片3 058张(鸟类:1 305张; 哺乳类:1 753张),RAI前5位的留鸟为红嘴蓝鹊Urocissa erythroryncha(RAI=1.82)、山噪鹛Garrulax davidi(RAI=1.40)、环颈雉Phasianus colchicus(RAI=1.07)、山斑鸠Streptopelia orientalis(RAI=0.81)和喜鹊Pica pica(RAI=0.71);哺乳类为松鼠Sciurus vulgaris (RAI=3.34)、岩松鼠Sciurotamias davidianus(RAI= 3.17)、蒙古兔Lepus tolai(RAI=3.17)、亚洲狗獾Meles leucurus(RAI=1.51)和猪獾Arctonyx collaris(RAI=0.57)。

监测范围内存在人类干扰的位点25个,占总位点数的62.5%。人类干扰整体无显著季节差异(χ2=3.105 0,df=3.000 0,P=0.376 0),夏季和冬季显著高于春季,春季和夏季,春季和冬季存在显著差异,而秋季和春季、夏季和秋季、夏季和冬季、秋季和冬季之间无显著差异(表 1)。人类干扰无显著海拔区段差异(K=0.656 0,df=3.000 0,P=0.884 0),海拔区段之间也无显著差异(表 1)。

| 因子 | 比较 | Z | P |

| 季节 | 春季vs.夏季 | -2.328 0 | 0.020 0 |

| 春季vs.秋季 | -1.924 0 | 0.054 0 | |

| 春季vs.冬季 | -1.988 0 | 0.047 0 | |

| 夏季vs.秋季 | -0.196 0 | 0.845 0 | |

| 夏季vs.冬季 | -0.722 0 | 0.470 0 | |

| 秋季vs.冬季 | -0.497 0 | 0.619 0 | |

| 海拔区段 | Ⅰ vs. Ⅱ | -0.381 0 | 0.703 0 |

| Ⅰ vs. Ⅲ | -1.009 0 | 0.313 0 | |

| Ⅰ vs. Ⅳ | -0.235 0 | 0.814 0 | |

| Ⅱ vs. Ⅲ | -0.143 0 | 0.886 0 | |

| Ⅱ vs. Ⅳ | -0.444 0 | 0.657 0 | |

| Ⅲ vs. Ⅳ | -0.302 0 | 0.763 0 |

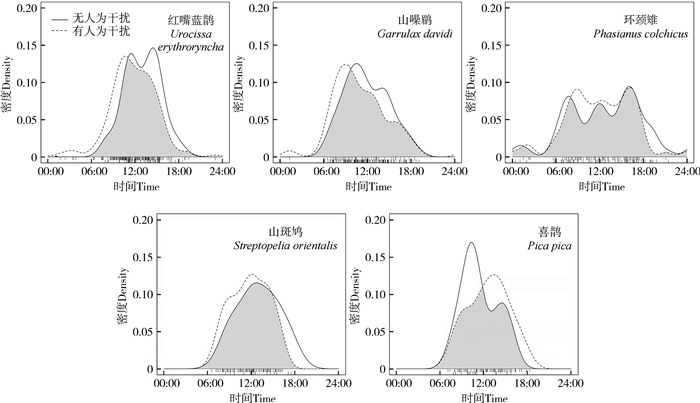

无人类干扰时,红嘴蓝鹊的活动节律存在2个活动高峰(11:00—12:00、15:00—16:00),但在有人类干扰时只有1个(08:00—10:00);山噪鹛、环颈雉、山斑鸠、喜鹊的区域间活动节律不存在显著分化。无人类干扰时,山噪鹛的活动节律存在2个活动高峰(10:00—12:00、13:00—15:00),而在有人类干扰时只有1个(07:00— 09:00);环颈雉的活动节律在有、无人类干扰时均存在3个活动高峰,第一个活动高峰在时间和峰值上出现差异(无人类干扰:06:00—08:00;有人类干扰:08:00—10:00),第二和第三个活动高峰相同(11:00—13:00、17:00—18:00);山斑鸠的活动节律在有、无人类干扰时均只存在1个活动高峰(12:00—13:00);无人类干扰时,喜鹊的活动节律存在2个活动高峰(08:00—10:00、13:00—15:00),而在有人类干扰时只有1个(12:00—15:00)(表 2; 图 1)。

| 物种 | △ | P | CI-lower | CI-upper |

| 红嘴蓝鹊 | 0.825 7 | 0.041 0 | 0.700 0 | 0.923 8 |

| 山噪鹛 | 0.857 5 | 0.170 0 | 0.741 9 | 0.955 0 |

| 环颈雉 | 0.878 0 | 0.705 0 | 0.775 1 | 0.950 9 |

| 山斑鸠 | 0.870 3 | 0.361 0 | 0.676 5 | 1.014 4 |

| 喜鹊 | 0.780 2 | 0.101 0 | 0.578 9 | 0.935 0 |

| 松鼠 | 0.775 2 | < 0.000 1 | 0.699 7 | 0.850 1 |

| 岩松鼠 | 0.853 5 | 0.024 0 | 0.779 3 | 0.920 8 |

| 蒙古兔 | 0.853 4 | 0.039 0 | 0.764 1 | 0.930 0 |

| 亚洲狗獾 | 0.842 0 | 0.641 0 | 0.713 8 | 0.948 0 |

| 猪獾 | 0.668 6 | 0.448 0 | 0.488 4 | 0.842 9 |

|

| 图 1 鸟类在有、无人类干扰下的活动节律比较 Fig. 1 Comparison of activity rhythm of birds with or without human disturbance |

| |

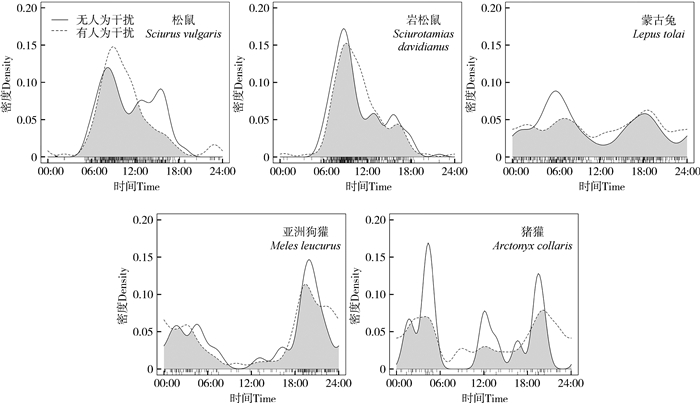

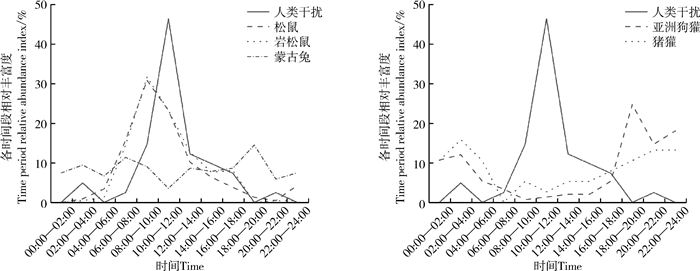

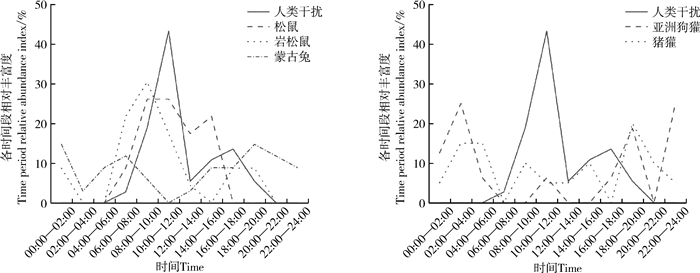

松鼠的活动节律在无人类干扰时存在3个活动高峰(06:00—08:00、11:00—13:00、14:00—16:00),而在有人类干扰时只有1个(08:00—10:00);岩松鼠的活动节律在无人类干扰时存在3个活动高峰(07:00—08:00、12:00—13:00、15:00—17:00),而在有人类干扰时只有2个(07:00—09:00、16:00—18:00);蒙古兔的活动节律在无人类干扰时存在2个活动高峰(05:00—07:00、15:00—19:00),而在有人类干扰时有3个(00:00—03:00、05:00—07:00、16:00—19:00)。夜行性哺乳类亚洲狗獾和猪獾的区域间活动节律无显著分化。亚洲狗獾的活动节律在有、无人类干扰时均存在2个活动高峰(02:00—06:00、18:00—20:00),但其出现时间有差异(无人类干扰:05:00—06:00、19:00—20:00;有人类干扰:02:00—05:00、18:00—19:00);无人类干扰时猪獾的活动节律存在3个活动高峰(05:00—06:00、11:00—13:00、19:00—20:00),有人类干扰时只有2个(01:00—06:00、19:00—21:00)(表 2; 图 2)。

|

| 图 2 哺乳类在有、无人类干扰下的活动节律比较 Fig. 2 Comparison of activity rhythm of mammals with or without human disturbance |

| |

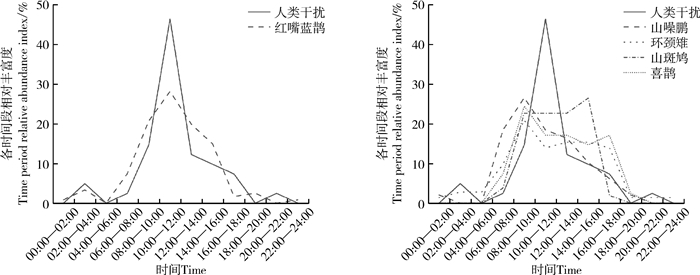

在低强度人类干扰区域内,红嘴蓝鹊活动高峰时段与人类干扰时段存在较多重叠,表现为不避开人类干扰高峰时段; 山噪鹛、环颈雉、山斑鸠、喜鹊在人类干扰时段活动强度均较高(图 3)。

|

| 图 3 鸟类在低强度人类干扰下的活动节律 Fig. 3 Activity rhythm of birds with lower intensity human disturbance |

| |

在高强度人类干扰区域内,红嘴蓝鹊在人类干扰高峰时段活动强度较在低强度下的低; 环颈雉、山斑鸠、喜鹊在人类干扰高峰时段活动强度均较低; 在该区域未监测到山噪鹛(图 4)。

|

| 图 4 鸟类在高强度人类干扰下的活动节律 Fig. 4 Activity rhythm of birds with higher intensity human disturbance |

| |

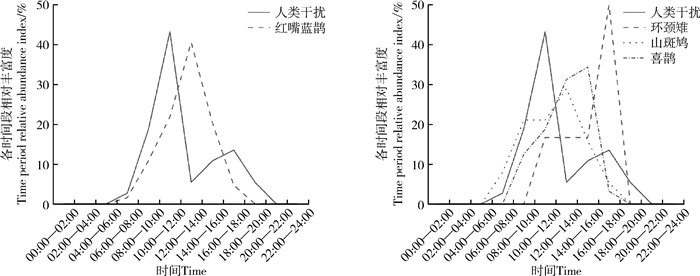

在低强度人类干扰区域内,松鼠、岩松鼠在人类干扰时段活动强度较高,均表现为不避开人类干扰高峰时段; 蒙古兔在人类干扰高峰时段活动强度最低; 亚洲狗獾、猪獾均以夜间活动为主(图 5)。

|

| 图 5 哺乳类在低强度人类干扰下的活动节律 Fig. 5 Activity rhythm of mammals with lower intensity human disturbance |

| |

在高强度人类干扰区域内,松鼠在14:00—16:00的活动强度较在低强度下的高,岩松鼠在夜间和黄昏时的活动强度较在低强度下的高,均表现为在非人类干扰高峰时段较活跃; 蒙古兔在夜间的活动强度较在低强度下的高,在日间的活动强度低; 亚洲狗獾、猪獾以夜间活动为主(图 6)。

|

| 图 6 哺乳类在高强度人类干扰下的活动节律 Fig. 6 Activity rhythm of mammals with higher intensity human disturbance |

| |

面对人类干扰,野生动物个体会有不同的行为响应,耐受性较高的个体可能表现出容忍行为,而耐受性较低的个体可能会发生迁移行为(Bejder et al., 2009)。使用交通工具(Tarr et al., 2010)、散步(Wallace,2016)等非致命的人类干扰活动可能导致野生动物短期或长期的应激生理反应(Coetzee & Chown,2016)。当人类干扰长期或连续出现时,野生动物会在避免生存风险与进行必要日常活动之间权衡,从而作出进一步行为响应(Frid & Dill,2002; Haigh et al., 2017),它们可能对人类干扰习惯化或敏感化,即由于人类干扰刺激而导致的反应的相对减弱或增强(Bejder et al., 2009; Weston et al., 2012)。本研究中山噪鹛、环颈雉、山斑鸠、喜鹊的活动节律在有、无人类干扰区域间不存在显著分化。这些鸟类均可在人类干扰较频繁的地区觅食或生存(张青霞,薛红忠,2000; 吴丽荣,2005; 牛俊英等,2008; 程晓福,殷小慧,2009),这表明相关物种面对人类干扰时具有较高水平的耐受性(Bonier et al., 2007; Mikula,2014; Samia et al., 2015),这可能是上述研究物种的活动节律面对人类干扰时未发生显著变化的原因。

本研究中红嘴蓝鹊的活动节律在有、无人类干扰区域间存在显著分化,且研究结果表明在低强度人类干扰下的活动高峰时段与人类干扰时段相同,表现为不避开人类干扰高峰时段。已有研究发现,红嘴蓝鹊更适宜在山区生境类型生存(李炳华,1984; 付玉冰,2018),相较于在城市化生境中的优势物种,红嘴蓝鹊对人类干扰的耐受性较低(孙丰硕,2016),其活动节律可能易受到人类干扰的影响。鸟类可利用人类产生的垃圾作为食物(Fernández-Juricic et al., 2002; Webb & Blumstein,2005),并可能利用人类的存在来作为非人类捕食者的“盾牌”(Berger,2007),这对生存于受人类干扰地区的一些个体来说,可减少或抵消风险感知的能量分配(McGiffin et al., 2013; Storch,2013),据此推测在受到人类干扰地区生存的部分红嘴蓝鹊个体选择建立起对人类干扰的习惯化(Fernández-Juricic et al., 2002; Pauli et al., 2016; 鲍明霞等,2019),提高了对人类干扰的耐受性(Moore et al., 2016),以减少分配过多的风险感知,避免不必要的能量消耗而浪费采食机会(葛晨,2012),这与其他研究中野生鸟类面对人类干扰的反应基本一致,西美鸥Larus occidentalis的分布主要基于对人类干扰的耐受性,耐受性较强的个体优先选择码头附近的栖息地并利用人类垃圾提供的食物,耐受性较差的个体则分布在人类干扰少的区域(Webb & Blumstein,2005); 麻雀Passer montanus的警戒距离与到人类干扰频繁区域的距离呈正相关(张凡梦等,2021)。

不同程度的人类干扰对野生动物的影响程度不同(Qiu et al., 2019),当可见视野范围内的人类干扰不断增加,野生动物个体的警惕性也会随之增加(Pays et al., 2012); 当感知风险过高时,鸟类等野生动物可能根据当前生存情况而改变自身行为(Mikula,2014),通过调节活动节律来回避人类干扰,也可能会从人类干扰强度高的地区向强度低的地区迁移(Wallace,2016)。本研究中5种留鸟均表现为在低强度人类干扰高峰时段活动强度较高,而在高强度人类干扰高峰时段活动强度低,这与先前其他鸟类的相关研究结果基本一致,大凤头燕鸥Thalasseus bergii在繁殖期往往不会使用人类高度干扰的地点(Schlacher et al., 2013); 白冠长尾雉Syrmaticus reevesii为应对人类干扰显示出错峰活动的现象(石江艳等,2020); 当自然环境中出现较频繁的人类干扰时,非地栖鸟类会选择主动回避(徐婉芸等,2020)。

3.2 人类干扰对哺乳类活动节律的影响人类干扰常被野生动物视为一种近似于捕食的风险,通过影响野生动物规避风险的所需能量和失去的机会成本,间接影响它们的生境适应度和种群动态(Frid & Dill,2002)。人类的存在可减少一些非人类捕食者的存在,使部分个体被捕食的风险降低,野生动物可能会因此选择生活在受人类干扰的地区(Li et al., 2011); 然而在人类主导的景观中,人类干扰对野生动物行为的影响甚至超过了栖息地和自然捕食者的影响(Ciuti et al., 2012),人类干扰对野生哺乳动物的直接压力被认为是它们在人类干扰地区数量稀少的重要原因之一(Ohashi et al., 2012; Paudel et al., 2012)。本研究发现,松鼠和岩松鼠的活动节律在有、无人类干扰区域间存在显著分化,且研究结果表明,松鼠和岩松鼠在低强度人类干扰下的活跃时段与人类干扰时段相同,而在高强度人类干扰下的个体在人类干扰高峰时段相对较弱、具有更多的晨昏或夜间活动。这可能是由于松鼠和岩松鼠中不同个体对外界刺激的耐受性具有差异,以一种非随机的方式分布在受不同强度人类干扰影响的区域(Martin & Reale,2008),即耐受性较强的个体分布在人类干扰强度较高区域,而耐受性较弱的个体分布在较低区域,这与Haigh等(2017)的研究结果相同,松鼠可以利用邻近景区的花园(中度干扰),也有些个体可以在景区关闭时使用野生动物园景区的栖息地(高度干扰)。这种行为与前人研究结果中野生哺乳动物应对日间人类干扰的行为表现类似,喜欢探索或温顺的花栗鼠Tamias striatus在人类经常出没的地区更为常见,其毛发中的皮质醇含量随温顺程度的增加而增加(Martin & Reale,2008),而皮质醇含量越高一定程度反映动物个体对外界刺激的耐受性越高(Palme et al., 2005)。

本研究中区域间活动节律同样存在显著分化的蒙古兔,其在不同强度人类干扰下均表现为回避,且相较于低强度人类干扰区域的个体,在高强度人类干扰区域的个体具有更多的夜间活动,这可能是由于蒙古兔提高了对人类干扰的警觉性(Ciuti et al., 2012),一方面它们可能选择缩短了觅食时间(Pays et al., 2012),使自身活动节律发生改变,从而避开人类干扰高峰(Beckmann & Berger,2003); 另一方面也可能由于人类直接与野生动物竞争空间和资源(Corradini et al., 2021),许多个体选择避开人类干扰频繁时段使用栖息地,或者不选择人类干扰频繁的区域作为栖息地(Martin et al., 2010; Murray & Clair,2015)。这些行为表现与前人相关研究结果基本一致,例如:马鹿Cervus elaphus面对人类干扰提高了自身警惕性,减少了觅食时间(Ciuti et al., 2012); 在人类干扰频繁的区域,非洲有蹄类动物的饮水行为会从白天转移到晚上(Crosmary et al., 2012)。

上述研究对象中的松鼠、岩松鼠为昼行性动物(王维禹,2018),蒙古兔在昼夜均活动(张相锋等,2019),而本研究结果显示,区域间活动节律不存在显著分化的哺乳类物种猪獾和亚洲狗獾均为夜行性动物(李峰,蒋志刚,2014),其原因可能是人类干扰的影响往往发生在白天(Ohashi et al., 2012),夜行性动物不受直接影响(Reilly et al., 2017)。但本研究结果也表明,相较于低强度人类干扰区域内的个体,高强度人类干扰区域内的个体在夜间的活动强度更强,而少量日间活动的强度也更弱,这与前人的研究结果有相似之处,例如:狼Canis lupus表现出对人类干扰的时空回避(Hebblewhite & Merrill,2008); 棕熊Ursus arctos会尽量选择人类干扰少的区域作为栖息地(Martin et al., 2010); 狍Capreolus capreolus会调整其对栖息地的使用来应对人类干扰(Bonnot et al., 2013); 野猪Sus scrofa在人类干扰频繁时,基本只在夜间活动(Podg órski et al., 2013); 美洲狮Puma concolor在人类干扰强度大的地方会调整昼夜活动,增加夜间活动(Wang et al., 2015)。

综上所述,本研究基于红外相机技术重点关注天津盘山风景名胜区人类干扰对相对丰富度较高的留鸟和哺乳类活动节律的潜在影响,可以为相关自然保护地的野生动物综合保护与管理提供基础科学参考依据。由于红外相机技术自身局限性,对非地栖鸟类物种监测相对有限。建议今后相关研究综合应用多种技术方法,在更多研究地点开展系统比较研究,全面评估不同程度人类干扰对各类野生动物物种的影响效应。

鲍明霞, 杨森, 杨阳, 等. 2019. 城市常见鸟类对人为干扰的耐受距离研究[J]. 生物学杂志, 36(1): 55-59. |

陈向阳, 范俊功, 王鹏华, 等. 2019. 利用红外相机技术对河北太行山东坡南段的鸟兽调查[J]. 兽类学报, 39(5): 575-584. |

程晓福, 殷小慧. 2009. 宁夏六盘山自然保护区环颈雉秋季栖息地的选择[J]. 野生动物, 30(4): 193-196, 200. |

付玉冰. 2018. 浙江天童国家森林公园鸦科鸟类繁殖期行为时间分配研究[D]. 上海: 华东师范大学.

|

葛晨. 2012. 人类干扰下的野生鸟类警戒行为研究[D]. 南京: 南京大学.

|

黄雯怡. 2020. 人与野生动物关系的历史考察和现实反思[J]. 南京社会科学, (8): 52-57, 65. |

蒋志刚. 2015. 中国哺乳动物多样性及地理分布[M]. 北京: 科学出版社.

|

蒋志刚, 李立立, 罗振华, 等. 2016. 通过红色名录评估研究中国哺乳动物受威胁现状及其原因[J]. 生物多样性, 24(5): 552-571. |

李炳华. 1984. 红嘴蓝鹊的繁殖习性[J]. 野生动物, (1): 18-20. |

李晟, 王大军, 肖治术, 等. 2014. 红外相机技术在我国野生动物研究与保护中的应用与前景[J]. 生物多样性, 22(6): 685-695. |

李峰, 蒋志刚. 2014. 狗獾夜间活动节律是受人类活动影响而形成的吗?基于青海湖地区的研究实例[J]. 生物多样性, 22(6): 758-763. |

刘建泉, 杨建红. 2004. 人类活动对甘肃境内国家重点保护野生动物的影响[J]. 安全与环境学报, 4(5): 29-33. |

刘子成, 李乐, 万冬梅, 等. 2012. 人类干扰导致的草原不同程度退化对繁殖鸟类多样性的影响[J]. 四川动物, 31(5): 720-724. |

牛俊英, 马朝红, 马书钊, 等. 2008. 河南黄河湿地国家级自然保护区不同生境鸟类多样性分析[J]. 四川动物, 27(5): 905-906, 934. |

潘秋荣, 叶辉, 韩婉诗, 等. 2019. 利用红外相机技术对广东东源康禾省级自然保护区林下鸟兽群落组成及其特征的研究[J]. 林业与环境科学, 35(6): 67-73. |

石江艳, 杨海, 华俊钦, 等. 2020. 利用红外相机研究白冠长尾雉活动节律与人为干扰的关系[J]. 生物多样性, 28(7): 796-805. |

Smith AT, 解焱. 2009. 中国兽类野外手册[M]. 长沙: 湖南教育出版社.

|

孙丰硕. 2016. 不同城市化水平鸟类群落特征及城区鸟类对生境因子的选择[D]. 北京: 北京林业大学.

|

王维禹. 2018. 长白山国家级自然保护区松鼠种群数量时空变化[D]. 哈尔滨: 东北林业大学.

|

吴丽荣. 2005. 山西芦芽山自然保护区山噪鹛的生态观察[J]. 四川动物, 24(4): 156-157. |

徐婉芸, 刘琰冉, 梦梦, 等. 2020. 利用红外相机数据分析藏东南地区物种对人为干扰的耐受性[J]. 生态学杂志, 39(9): 3164-3173. |

张凡梦, 鄢冉, 刘恣妍, 等. 2021. 北京城区麻雀的逃逸距离及其影响因素[J]. 四川动物, 40(2): 160-168. |

张青霞, 薛红忠. 2000. 历山保护区山斑鸠的繁殖习性[J]. 四川动物, 19(4): 239-240. |

张相锋, 郭锋, 彭阿辉, 等. 2019. 京新高速公路哈腾套海保护区段野生动物通道监测研究[J]. 野生动物学报, 40(4): 848-854. |

张宇硕, 卢宪旺, 关洪武, 等. 2021. 天津盘山风景名胜区哺乳动物和鸟类多样性[J]. 野生动物学报, 42(3): 774-782. |

赵广华, 田瑜, 唐志尧, 等. 2013. 中国国家级陆地自然保护区分布及其与人类活动和自然环境的关系[J]. 生物多样性, 21(6): 658-665. |

郑光美. 2017. 中国鸟类分类与分布名录[M]. 第三版. 北京: 科学出版社.

|

郑华, 欧阳志云, 赵同谦, 等. 2003. 人类活动对生态系统服务功能的影响[J]. 自然资源学报, 18(1): 118-126. |

Azlan JM, Sharma DSK. 2006. The diversity and activity patterns of wild felids in a secondary forest in Peninsular Malaysia[J]. Oryx, 40(1): 36-41. DOI:10.1017/S0030605306000147 |

Beale CM, Monaghan P. 2004. Human disturbance: people as predation-free predators?[J]. Journal of Applied Ecology, 41(2): 335-343. DOI:10.1111/j.0021-8901.2004.00900.x |

Beckmann JP, Berger J. 2003. Rapid ecological and behavioural changes in carnivores: the responses of black bears (Ursus americanus) to altered food[J]. Journal of Zoology, 261(2): 207-212. DOI:10.1017/S0952836903004126 |

Bejder L, Samuels A, Whitehead H, et al. 2009. Impact assessment research: use and misuse of habituation, sensitisation and tolerance in describing wildlife responses to anthropogenic stimuli[J]. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 395: 177-185. DOI:10.3354/meps07979 |

Berger J. 2007. Fear, human shields and the redistribution of prey and predators in protected areas[J]. Biology Letters, 3(6): 620-623. DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0415 |

Bonier F, Martin PR, Wingfield JC. 2007. Urban birds have broader environmental tolerance[J]. Biology Letters, 3(6): 670-673. DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0349 |

Bonnot N, Morellet N, Verheyden H, et al. 2013. Habitat use under predation risk: hunting, roads and human dwellings influence the spatial behaviour of roe deer[J]. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 59(2): 185-193. DOI:10.1007/s10344-012-0665-8 |

Brumm H. 2004. The impact of environmental noise on song amplitude in a territorial bird[J]. Journal of Animal Ecology, 73(3): 434-440. DOI:10.1111/j.0021-8790.2004.00814.x |

Burger J, Gochfeld M. 1998. Effects of ecotourists on bird behaviour at Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge, Florida[J]. Environmental Conservation, 25(1): 13-21. DOI:10.1017/S0376892998000058 |

Carrete M, Tella JL. 2017. Inter-individual variability in fear of humans and relative brain size of the species are related to contemporary urban invasion in birds[J/OL]. PLoS ONE, 6(4): e18859[2021-01-10]. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0018859.s001.

|

Ciuti S, Northrup JM, Muhly TB, et al. 2012. Effects of humans on behaviour of wildlife exceed those of natural predators in a landscape of fear[J/OL]. PLoS ONE, 7(11): e50611[2021-01-20]. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0050611.

|

Coetzee BW, Chown SL. 2016. A meta-analysis of human disturbance impacts on Antarctic wildlife[J]. Biological Reviews, 91(3): 578-596. DOI:10.1111/brv.12184 |

Corradini A, Randles M, Pedrotti L, et al. 2021. Effects of cumulated outdoor activity on wildlife habitat use[J/OL]. Biological Conservation, 253: 108818[2021-01-10]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108818.

|

Crosmary WG, Valeix M, Fritz H, et al. 2012. African ungulates and their drinking problems: hunting and predation risks constrain access to water[J]. Animal Behaviour, 83(1): 145-153. DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2011.10.019 |

Fernández-Juricic E, Jimenez M, Lucas E. 2001. Alert distance as an alternative measure of bird tolerance to human disturbance: implications for park design[J]. Environmental Conservation, 28(3): 263-269. DOI:10.1017/S0376892901000273 |

Fernandez-Juricic E, Jimenez MD, Lucas E. 2002. Factors affecting intra- and inter-specific variations in the difference between alert distances and flight distances for birds in forested habitats[J]. Canadian Journal of Zoology-Revue Canadienne De Zoologie, 80(7): 1212-1220. DOI:10.1139/z02-104 |

Frid A, Dill LM. 2002. Human-caused disturbance stimuli as a form of predation risk[J/OL]. Ecology and Society, 6(1): 11[2021-01-20]. https://doi.org/10.5751/es-00404-060111.

|

Gaynor KM, Hojnowski CE, Carter NH, et al. 2018. The influence of human disturbance on wildlife nocturnality[J]. Science, 360(6394): 1232-1235. DOI:10.1126/science.aar7121 |

Gill JA. 2007. Approaches to measuring the effects of human disturbance on birds[J]. IBIS, 149(1): 9-14. |

Haigh A, Butler F, O'Riordan R, et al. 2017. Managed parks as a refuge for the threatened red squirrel (Sciurus vulgaris) in light of human disturbance[J]. Biological Conservation, 211: 29-36. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2017.05.008 |

Hebblewhite M, Merrill E. 2008. Modelling wildlife-human relationships for social species with mixed-effects resource selection models[J]. Journal of Applied Ecology, 45(3): 834-844. |

Kaartinen S, Kojola I, Colpaert A. 2005. Finnish wolves avoid roads and settlements[J]. Annales Zoologici Fennici, 42(5): 523-532. |

Knight RL, Fitzner RE. 1985. Human disturbance and nest site placement in black-billed magpies[J]. Journal of Field Ornithology, 56(2): 153-157. |

Lamb C, Ford A, McLellan B, et al. 2020. The ecology of human-carnivore coexistence[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(30): 17876-17883. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1922097117 |

Li C, Monclús R, Maul TL, et al. 2011. Quantifying human disturbance on antipredator behavior and flush initiation distance in yellow-bellied marmots[J]. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 129(2-4): 146-152. DOI:10.1016/j.applanim.2010.11.013 |

Martin J, Basille M, Moorter BMV, et al. 2010. Coping with human disturbance: spatial and temporal tactics of the brown bear (Ursus arctos)[J]. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 88(9): 875-883. DOI:10.1139/Z10-053 |

Martin JG, Reale D. 2008. Animal temperament and human disturbance: implications for the response of wildlife to tourism[J]. Behavioural Processes, 77(1): 66-72. DOI:10.1016/j.beproc.2007.06.004 |

McGiffin A, Lill A, Beckman J, et al. 2013. Tolerance of human approaches by common mynas along an urban-rural gradient[J]. Emu-Austral Ornithology, 113(2): 154-160. DOI:10.1071/MU12107 |

Mikula P. 2014. Pedestrian density influences flight distances of urban birds[J]. Ardea, 102(1): 53-60. DOI:10.5253/078.102.0105 |

Miller S, Knight R, Miller C. 1998. Influence of recreational trails on breeding bird communities[J]. Ecological Applications, 8(1): 162-169. DOI:10.1890/1051-0761(1998)008[0162:IORTOB]2.0.CO;2 |

Møller AP. 2009. Successful city dwellers: a comparative study of the ecological characteristics of urban birds in the western Palearctic[J]. Oecologia, 159(4): 849-858. DOI:10.1007/s00442-008-1259-8 |

Moore AA, Green MC, Huffman DG, et al. 2016. Green herons (Butorides virescens) in an urbanized landscape: does recreational disturbance affect foraging behavior?[J]. The American Midland Naturalist, 176(2): 222-233. DOI:10.1674/0003-0031-176.2.222 |

Murray MH, Clair CCS. 2015. Individual flexibility in nocturnal activity reduces risk of road mortality for an urban carnivore[J]. Behavioral Ecology, 26(6): 1520-1527. DOI:10.1093/beheco/arv102 |

O'Brien TG, Kinnaird MF, Wibisono HT. 2003. Crouching tigers, hidden prey: Sumatran tiger and prey populations in a tropical forest landscape[J]. Animal Conservation, 6(2): 131-139. DOI:10.1017/S1367943003003172 |

Ohashi H, Saito M, Horie R, et al. 2012. Differences in the activity pattern of the wild boar (Sus scrofa) related to human disturbance[J]. European Journal of Wildlife Research, 59(2): 167-177. |

Palme R, Rettenbacher S, Touma C, et al. 2005. Stress hormones in mammals and birds: comparative aspects regarding metabolism, excretion, and noninvasive measurement in fecal samples[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1040(1): 162-171. DOI:10.1196/annals.1327.021 |

Paudel PK, Kindlmann P, Gordon I, et al. 2012. Human disturbance is a major determinant of wildlife distribution in Himalayan midhill landscapes of Nepal[J]. Animal Conservation, 15(3): 283-293. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2011.00514.x |

Pauli BP, Spaul RJ, Heath JA. 2016. Forecasting disturbance effects on wildlife: tolerance does not mitigate effects of increased recreation on wildlands[J]. Animal Conservation, 20(3): 251-260. |

Pays O, Blanchard P, Valeix M, et al. 2012. Detecting predators and locating competitors while foraging: an experimental study of a medium-sized herbivore in an African savanna[J]. Oecologia, 169(2): 419-430. DOI:10.1007/s00442-011-2218-3 |

Podgórski T, Bas G, Jędrzejewska B, et al. 2013. Spatiotemporal behavioral plasticity of wild boar (Sus scrofa) under contrasting conditions of human pressure: primeval forest and metropolitan area[J]. Journal of Mammalogy, 94(1): 109-119. DOI:10.1644/12-MAMM-A-038.1 |

Qiu L, Han H, Zhou H, et al. 2019. Disturbance control can effectively restore the habitat of the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca)[J/OL]. Biological Conservation, 238: 108233[2021-01-10]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108233.

|

Reilly ML, Tobler MW, Sonderegger DL, et al. 2017. Spatial and temporal response of wildlife to recreational activities in the San Francisco Bay ecoregion[J]. Biological Conservation, 207: 117-126. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.11.003 |

Ridout MS, Linkie M. 2009. Estimating overlap of daily activity patterns from camera trap data[J]. Journal of Agricultural, Biological, and Environmental Statistics, 14(3): 322-337. DOI:10.1198/jabes.2009.08038 |

Samia DSM, Nakagawa S, Nomura F, et al. 2015. Increased tolerance to humans among disturbed wildlife[J/OL]. Nature Communications, 6(1): 8877[2021-01-12]. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9877.

|

Schlacher TA, Nielsen T, Weston MA. 2013. Human recreation alters behaviour profiles of non-breeding birds on open-coast sandy shores[J]. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 118: 31-42. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2012.12.016 |

Schoech SJ, Bowman R, Reynolds SJ. 2004. Food supplementation and possible mechanisms underlying early breeding in the Florida scrub-jay (Aphelocoma coerulescens)[J]. Hormones and Behavior, 46(5): 565-573. DOI:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.06.005 |

Slabbekoorn H, Ripmeester EA. 2008. Birdsong and anthropogenic noise: implications and applications for conservation[J]. Molecular Ecology, 17(1): 72-83. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03487.x |

Storch I. 2013. Human disturbance of grouse-why and when?[J]. Wildlife Biology, 19(4): 390-403. DOI:10.2981/13-006 |

Tarr NM, Simons TR, Pollock KH. 2010. An experimental assessment of vehicle disturbance effects on migratory shorebirds[J]. Journal of Wildlife Management, 74(8): 1776-1783. DOI:10.2193/2009-105 |

Wallace P. 2016. Managing human disturbance of wildlife in coastal areas[J]. New Zealand Geographer, 72(2): 133-143. DOI:10.1111/nzg.12124 |

Wang Y, Allen ML, Wilmers CC. 2015. Mesopredator spatial and temporal responses to large predators and human development in the Santa Cruz Mountains of California[J]. Biological Conservation, 190: 23-33. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2015.05.007 |

Webb NV, Blumstein DT. 2005. Variation in human disturbance differentially affects predation risk assessment in western gulls[J]. The Condor, 107(1): 178-181. DOI:10.1093/condor/107.1.178 |

Weston MA, McLeod EM, Blumstein DT, et al. 2012. A review of flight-initiation distances and their application to managing disturbance to Australian birds[J]. Emu: Austral Ornithology, 112(4): 269-286. DOI:10.1071/MU12026 |

2022, Vol. 41

2022, Vol. 41