扩展功能

文章信息

- 徐传飞, 伍仕鑫, 孙磊, 蔡欣

- XU Chuanfei, WU Shixin, SUN Lei, CAI Xin

- MicroRNA在哺乳动物精子发生中的作用

- The Roles of MicroRNAs in Mammalian Spermatogenesis

- 四川动物, 2016, 35(5): 789-796

- Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2016, 35(5): 789-796

- 10.11984/j.issn.1000-7083.20160081

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2016-04-12

- 接受日期: 2016-07-20

哺乳动物不育的发病机制以及相关的致病因素一直以来都是动物育种中的难点问题,且大多数哺乳动物的不育都是由雄性生殖障碍引起,如弱精症、无精症,而这些生殖障碍通常是由于雄性生殖细胞的形成以及成熟缺陷导致。哺乳动物精子发生是一个多步骤发展的复杂过程,并涉及错综复杂的基因表达调控过程,包括转录和转录后水平的调控,其中任何一个环节出错都可能导致雄性不育。二倍体生殖细胞经过一系列细胞分裂、分化过程后形成成熟的精子,并通过精卵细胞的结合才能发育成成熟个体,所以哺乳动物精子发生在生殖发育以及物种延续中具有重要作用。近年来,对microRNA(miRNA)越来越多的研究表明其在精子发生以及早期胚胎发育等过程中发挥着重要作用,阐明miRNA在哺乳动物生命活动中的作用及其机理将对转录后基因调节领域的发展具有深远影响。本文着重围绕miRNA的合成及作用机制以及其在精子发生过程中的调控作用进行综述。

1 miRNA的发现、来源和作用机制 1.1 miRNA的发现miRNA是一类来源于内源性基因长20~24 nt的单链非编码调控RNA序列,是非编码RNA家族的重要成员之一。对miRNA的研究最早始于1993年,在秀丽隐杆线虫Caenorhabditis elegans的胚后发育阶段,一种22 nt的RNA分子lin-4通过与lin-14 mRNA的3'端碱基配对的方式抑制核蛋白lin-14的表达来调控线虫的发育进程(Lee et al., 1993;Wightman et al., 1993)。此后,在2000年又发现存在于线虫幼虫时期的miRNA let-7通过下调基因lin-41来减缓基因lin-29的抑制作用(Slack et al., 2000)。随着在动植物中发现的miRNA种类和数量的增多,研究者也越来越重视其转录后水平对靶基因的调控作用。

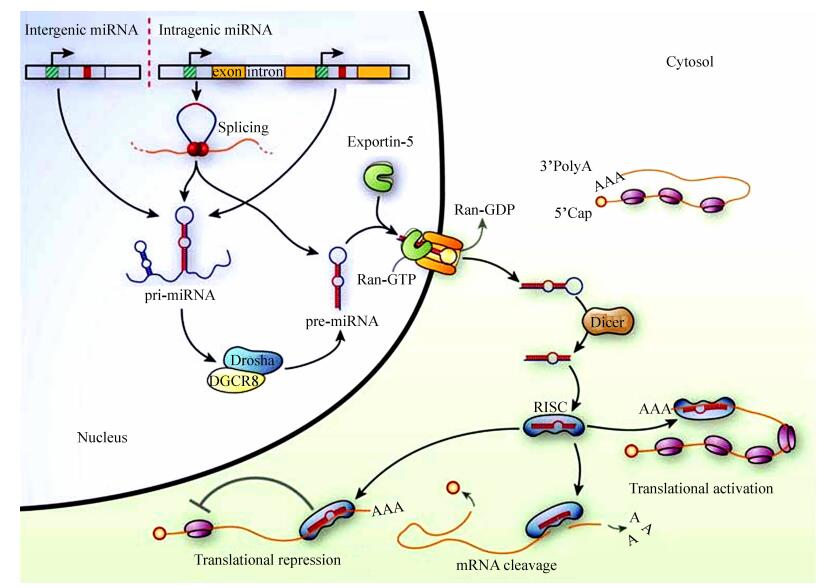

1.2 miRNA的来源成熟的miRNA是长约22 nt的不编码蛋白质的短序列RNA,其合成过程主要包括2个步骤:miRNA基因转录形成的初级miRNA(pri-miRNA)通过剪切形成长约70 nt的前体miRNA(pre-miRNA)以及pre-miRNA通过剪切形成长约22 nt的成熟miRNA(图 1)。大多数人类miRNA和普通mRNA的形成过程一样,是在RNA聚合酶Ⅱ的作用下先形成双链pri-miRNA,后在5'端加M7G帽以及3'端加ploy(A)尾结构(Kim,2005)。但并不是所有的pri-miRNA都在RNA聚合酶Ⅱ的催化下形成,如分布在人类19号染色体上Alu重复序列中的miRNA簇的转录依赖于RNA聚合酶Ⅲ的催化(Borchert et al., 2006)。核糖核酸酶Drosha RNase Ⅲ(Lee et al., 2003)的RⅢDa和RⅢDb两亚基分别对pri-miRNA的5'和3'端进行剪切后形成具有发夹结构的pre-miRNA,长度约70 nt,且在3'端悬挂2 nt的核糖核苷酸(Han et al., 2004)。动物中的Drosha酶是约160 kDa的保守蛋白,其二级结构包括2个串联的RNase Ⅲ区域(RⅢDs)和1个具有结合催化作用的双链RNA区域(dsRBD)(Han et al., 2004)。在黑腹果蝇Drosophila melanogaster和人类细胞中,Drosha酶可以与DGCR8蛋白分别形成约500 kDa和650 kDa的复合体,并且该复合体对pri-miRNA剪切过程被称为“Microprocess”(Denli et al., 2004;Gregory et al., 2004),而DGCR8蛋白具有与双链RNA结合的能力,通过与Drosha酶氨基端脯氨酸富集区域的表面相互作用,能稳定Drosha酶对pri-miRNA的结合作用,从而促进Drosha酶的剪切作用(Han et al., 2004;Wang et al., 2007)。有一种假设认为DGCR8蛋白能够识别pri-miRNA在发夹结构单链与双链的结合区域,并使Drosha酶在此解旋约1个螺旋结构后形成直链(Han et al., 2006)。此外,也有假设认为pri-miRNA的终端环状结构也能影响Drosha酶的剪切作用(Zhang & Zeng,2010)。除一些特别的miRNA由单独的基因转录通过剪切形成,形成大多数miRNA的基因既可编码miRNA簇又可编码一种miRNA或者一种蛋白(Bartel,2004)。除上述过程之外,在非典型miRNA的形成路径中,一些内含子miRNA不需要核糖核酸酶的作用,而是在一种miRNA新亚型mirtron的作用下,通过拼接形成具有发夹结构的pre-miRNA,从而跳过Drosha酶/DGCR8蛋白复合体的处理过程(Westholm & Lai,2011;Li et al., 2012)。

|

| 图 1 miRNA的合成及作用机制示意图(Olde Loohuis et al., 2012) Fig. 1 The biogenesis and mechanism of miRNA(Olde Loohuis et al., 2012) 由基因间区或基因编码区或非编码区转录形成的pri-miRNA在Drosha酶/DGCR8蛋白复合体的作用下形成长度约70 nt且具有发夹结构的pre-miRNA,并通过转运蛋白Exportin-5进入细胞质; pre-miRNA经Dicer酶作用形成成熟miRNA,并通过与含AGO蛋白的复合体结合形成miRISC; miRNA通过同靶mRNA的3'端相互作用调控基因的表达。 Pri-miRNA transcripts, transcribed from intergenic genes or genes coded within introns of coding or non-coding genes, are processed into a pre-miRNA by the Drosha/DGCR8 complex, creating a 70~80 nts, hairpin-looped molecule, which is then shuttled out of the nucleus via the exportin-5 mediated transport; cytoplasmatic digestion of the pre-miRNA is facilitated by Dicer, resulting in mature miRNAs which associate with Argonaute-containing complexes to form the RNA induced silencing complex; miRNAs modulate gene expression by pairing with sequences in the 3'UTRs of target mRNAs. |

| |

以上过程都发生在细胞核内,而pre-miRNA必须通过核孔复合体进入到细胞质内才能形成成熟的miRNA。转运蛋白Exportin-5(Exp5)通过识别悬挂在3'端的2 nt结构并结合在pre-miRNA发夹结构上,在Ran-GTP(the GTP bound form of Ran GTPase)的供能下,pre-miRNA通过核孔进入细胞质内(Yi et al., 2003)。正是由于Exp5的功能才能确保pre-miRNA向细胞质的有效释放以及pre-miRNA的完整性;而Ran-GTP在细胞质中的浓度低于在细胞核中的浓度,pre-miRNA又与Exp5相分离(Lund et al., 2004)。在细胞质中,Dicer RNase Ⅲ酶能识别pre-miRNA并剪切形成约22 nt的miRNA(Grishok et al., 2001;Ketting et al., 2001)。然后miRNA先后在Dicer RNase Ⅲ酶和其他一些蛋白质的作用下形成单链的成熟miRNA(Hutvagner et al., 2001)。正常条件下,成熟的miRNA只有一条链能对转录后的RNA产生相应的调控作用,剩下的一条链通常在酶的作用下水解,水解链主要取决于每条链5'端的相对热力学稳定性(Schwarz et al., 2003)。内部具有相对较低稳定性的单链能与核糖核蛋白结合形成非对称性的miRNA诱导的基因沉默复合物(miRNA-induced silencing complex,miRISC)(Khvorova et al., 2003;Schwarz et al., 2003),而pre-miRNA的发夹结构能影响Dicer酶的识别作用,从而剪切形成不同对称性的小干扰RNA (small interfering RNA, siRNA)样的“茎臂结构”(stem-arm construct),正是由于这种结构的不对称性才影响在形成有效miRISC过程中不同成熟miRNA的挑选作用(Lin et al., 2005)。

1.3 miRNA的作用机制miRISC对于miRNA的处理以及RNA的干扰必不可少,并且至少由miRNA、蛋白Dicer、TRBP和AGO四种物质构成。TRBP蛋白是人类免疫缺陷病反式激活RNA结合蛋白(human immunodeficiency virus trans-activating response RNA-binding protein),是Dicer复合体不可或缺的物质(Chendrimada et al., 2005)。在哺乳动物细胞中,AGO蛋白是唯一行使mRNA分解功能的蛋白质,它在抑制翻译过程也具有重要作用(Liu et al., 2004;Pratt & MacRae,2009)。大多数miRNA同靶mRNA的3'端相互作用,且几乎所有的miRNA通过与靶mRNA部分互补配对的方式抑制该mRNA的翻译过程(Olsen & Ambros,1999;Millar & Waterhouse,2005;Behm-Ansmant et al., 2006;Ameres & Zamore,2013)。因此,人们猜测哺乳动物miRNA主要通过抑制翻译过程或者降解mRNA而不是内切核苷酸降解的方式发挥其调控功能(Ameres & Zamore,2013)。在哺乳动物中,一些miRISC能够识别靶mRNA的5'端M7G帽子部位并抑制翻译过程(Pillai et al., 2005),随后则引起mRNA的降解(Ameres & Zamore,2013),但对于miRNA作用机制的真实调控过程还有待进一步揭示。有趣的是,尽管哺乳动物miRNA通常在miRISC其他组成部分的协助下,抑制翻译过程或者直接使靶mRNA降解,但miRNA也可能促进转录和翻译过程。例如,在神经元细胞发育过程中,miR-128通过抑制无义介导的衰变途径(the nonsense-mediated decay pathway)来促进mRNA的表达(Bruno et al., 2011)。在细胞周期停滞期间,有一些miRNA,如miR-369-3调控AU序列同AGO蛋白以及脆性X智力迟钝蛋白1(fragile X mental retardation protein 1)的结合,从而上调正常增殖细胞的翻译过程(Vasudevan et al., 2007)。此外,与动物miRNA相反,植物miRNA对于靶mRNA表现出更多的互补性且比动物miRNA具有更高同源性(Millar & Waterhouse,2005;Ameres & Zanore,2013)。

2 miRNA对精原细胞自我更新以及分化的影响精子发生是一个高度复杂协调的过程,成熟的精子都来源于共同的精原干细胞(spermatogonia stem cells, SSCs)。SSCs是一群位于生精上皮底部,具有高度自我更新和多向分化潜能的细胞,是精子发生的起始细胞。而SSCs的自我更新能维持干细胞数量稳定以及精子发生的持续进行。在成年哺乳动物中,SSCs能通过重复的有丝分裂形成Apaired(Apr)和Aligned(Aal)精原细胞,Aal精原细胞经有丝分裂形成Aal(4)、Aal(8)、Aal(16)精原细胞,进一步分化形成A1型精原细胞,再经过增殖分裂形成A2型、A3型、A4型精原细胞,而A4型精原细胞成熟形成B型精原细胞,再经过有丝分裂形成初级精母细胞,最终经过减数分裂分化形成成熟精子(Oatley & Brinster,2008)。

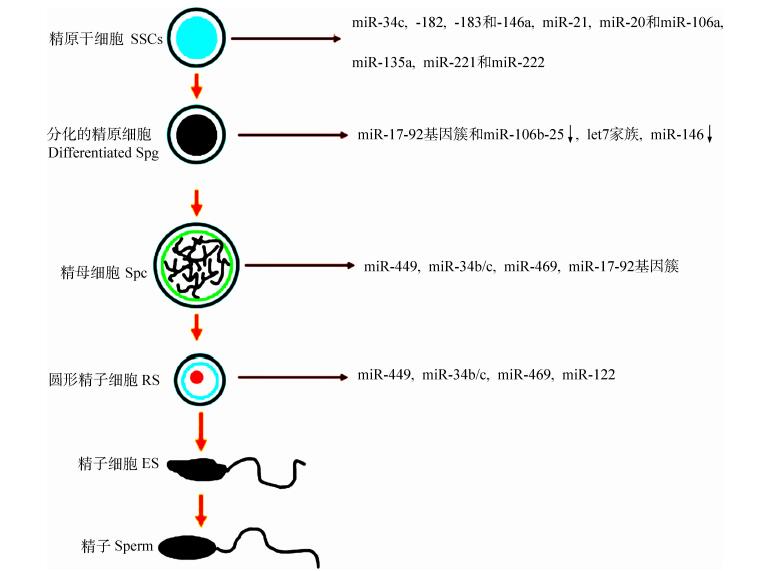

近年来,通过miRNA的微阵列以及逆转录PCR等技术,在小鼠的睾丸中发现大量的miRNA表达谱,并且有许多miRNA在精原细胞的自我更新以及分化过程中具有重要作用。Niu等(2011)利用高通量测序技术发现,相比Thy1-睾丸支持细胞以及间质细胞等多种睾丸体细胞,miR-34c、miR-182、miR-183以及miR-146a都在体外Thy1+ SSCs中优先表达。在SSCs的培养中发现,miR-21的短暂抑制增加了生殖细胞凋亡的数量,并且在通过移植手术的受体小鼠睾丸组织中,减少了供体生殖细胞精子发生的数量。此外,在体外SSCs的生殖细胞培养中发现,miR-21受转录因子ETV5的调控,而转录因子ETV5对SSCs的自我更新至关重要(Tyagi et al., 2009),并且miR-21的增强子区域具有转录因子ETV5的结合区域。这表明miR-21在调控SSCs的自我更新中具有重要作用。通过对患隐睾症动物的睾丸研究发现,miR-135a通过调控foxO1(fork head box protein 1)来影响SSCs的数目恒定(Moritoki et al., 2014)。除此之外,miR-20和miR-106a在转录后的水平上通过靶向基因STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3)和Ccnd1 (CyclinD1)促进SSCs的更新(图 2)。

|

| 图 2 不同miRNA在哺乳动物睾丸中不同的表达方式 Fig. 2 The expression patterns of miRNAs in various types of cells in mammalian testis 不同miRNA(miR-34c、 -182、 -183、 -146a、 miR-21、 miR-20、 miR-106a、 miR-135a、 miR-221和miR-222)参与SSCs的自我更新;miR-17-92基因簇和miR-106b-25、let7家族、miR-146则参与调控SSCs的分化;miR-449、miR-34b/c、miR-469则存在于精母细胞和精子细胞中;而miR-34a、-34b、-34c和miR-122则与精子发育相关(Yao et al.,2015)。 Numerous miRNAs (e.g.miR-34c, -182, -183 and -146a, miR-21, miR-20, miR-106a, miR-135a, miR-221, and miR-222) have been shown to regulate SSCs self-renewal; miR-17-92 cluster, miR-106b-25, let-7 family and miR-146 are involved in the regulation of mouse spermatogonial differentiation; miR-449, miR-34b/c and miR-469 are located in mouse spermatocytes and spermatids, while miR-34a, -34b, -34c and miR-122 are associated with sperm development (Yao et al., 2015). |

| |

精原细胞分化是一个涉及维甲酸(retinoic acid,RA)信号并受基因表达精确调控的过程。RA是维生素A(vitamin A)的代谢产物,在由Aal精原细胞分化形成A1型精原细胞过程中,RA具有至关重要的作用,对于缺乏维生素A的小鼠,其精原细胞分化受阻于此过程(Griswold et al., 1989)。而miRNA也是精原细胞分化过程中的重要调控因子。RA通过抑制Lin 28基因的表达能显著引起mirlet7 miRNAs的感应,从而抑制精原细胞分化过程中靶基因Mycn(N-myc)、Ccnd 1、Col1a2 (collagen type Ⅰ alpha 2 chain)的表达(Tong et al.,2011)。miR-17-92(Mirc1)以及miR-106b-25(Mirc3)在RA诱导的精原细胞分化过程中明显受到抑制,但却能反过来促进基因Bim(BCL2-Like 11)、Kit(CD117)、Socs 3 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 3)、Stat 3的表达,小鼠胚胎miR-17-92敲除后导致小鼠的睾丸缩小、附睾少精以及精子发生缺陷(Tong et al.,2011)。而基因Kit是精原细胞的标识,也涉及精原细胞的分化过程。虽然这些基因是否是miR-17-92以及miR-106b-25的靶基因还有待进一步研究,但这些与精原细胞分化有关的基因在未分化的精原细胞中受到miR-17-92以及miR-106b-25的抑制,而在精原细胞分化的过程中,miR-17-92以及miR-106b-25的抑制又诱导这些基因的表达则得到证实(Tong et al.,2011)。miR-146在精原细胞分化的过程中具有调节RA的作用效果,miR-146过表达时具有阻碍精原细胞中RA信号的作用效果,而miR-146的表达抑制时则会导致协同效应。miR-146能直接与基因Med 1 (mediator complex subunit 1)结合并抑制其表达,MED1主要通过调控来自于细胞核激素的受体信号来影响细胞的分化,且还能直接与RA受体相结合,但是对于RA诱导的转录效果影响还有待进一步研究,而miR-146表达或抑制将改变Med 1基因的表达。对于RA处理过的精原细胞,当miR-146的过量表达时,会抑制基因Kit、Stra 8 (stimulated by retinoic acid gene 8)以及Sohlh 2 (spermatogenesis-and oogenesis-specific basic helix-loop-helix 2)的上调,当miR-146表达受到抑制时,会促进这些基因的上调(Huszar & Pavne,2013)。这就表明了miR-146在RA诱导的精原细胞分化路径中通过调控靶基因来影响精原细胞的分化过程。此外,miR-34c在不同的物种细胞增殖、细胞凋亡以及细胞分化的过程中发挥作用(Corney et al., 2007)。Yu等(2014)发现,miR-34c通过靶向基因Nanos 2调控SSCs的分化,并且促进Nanos3、Scp3 (single-cell protein 3)和Stra 8等减数分裂相关基因的表达。以往的研究已表明,Nanos 2 基因属于在进化上保守且具有能与RNA结合局域的NANOS家族,能够抑制SSCs的分化且维持SSCs的自我更新(Shen & Xie,2010)。在小鼠雄性生殖干细胞中,Nanos 2基因能够抑制减数分裂,反过来维持SSCs的稳定(Suzuki & Saga,2008;Sada et al., 2012)。Stra 8基因的表达是雌雄生殖细胞进入减数分裂的标志,并且是减数分裂开始不可或缺的。而Nanos 3基因在不同物种的生殖细胞发育过程中发挥作用,如果蝇、青蛙、老鼠以及人类(Julaton & Reijopera,2011)。在未分化的精原细胞中,Nanos 2基因在抑制基因Nanos 3、Scp3、Stra8的表达,并使SSCs或者精原细胞保持未分化的状态上具有重要作用。当小鼠睾丸组织成熟时,miR-34c通过靶向基因Nanos 2消除基因Nanos3、Scp3、Stra8的抑制状态,并促进SSCs或者精原细胞向分化状态转变(Yu et al., 2014)。

3 miRNA对精母细胞减数分裂以及精子变态发育的影响减数分裂是有性生殖个体在形成生殖细胞过程中发生的一种特殊分裂方式,在个体的繁殖和生命周期中处于核心地位。在减数分裂期间,染色体会经历一系列错综复杂的结构变化。在经过一个较有丝分裂更长的S期后,生殖细胞进入第一次减数分裂的前期(Zickler & Kleckner,1998)。根据染色体在此期间的形态特征,分为细线期、偶线期、粗线期、双线期以及终变期。最近研究发现,在小鼠睾丸中显著表达的miR-449主要存在于精母细胞和圆形精子细胞中,并且在减数分裂过程中能够抑制E2F-pRb(E2F transcription factor-retinoblastoma protein pathway)路径的活性,而miR-34b/c和miR-449表现出相同的调控作用(Bouhallier et al., 2010;Bao et al., 2012;Wu et al., 2014)。对于缺少miR-34b/c或者miR-449的个体没有造成任何明显的可识别表型,但是miR-34b/c以及miR-449的同时缺陷则会导致不育(Wu et al., 2014)。这就表明,对于特定miRNA调控的表型,需要采用二倍或者三倍的miRNA敲除法才可能消除不同miRNA功能冗余的影响。而miRNA-34簇也在牛精子中被发现(Tscherner et al., 2014)。此外miR-34c在小鼠粗线期精母细胞中通过靶向转录因子1(activating transcription factor 1,ATF1)调控精母细胞的凋亡(Liang et al., 2012)。而ATF1在小鼠早期胚胎发育阶段调节维持细胞活性的信号是必不可少的(Bleckmann et al., 2002;Persengiev & Green,2003)。这些研究都表明miR-34家族在精子发生过程中的重要性。

精母细胞经过减数分裂后产生圆形的单倍体精子细胞,再经过变态发育分化形成成熟精子,而染色质的浓缩是细胞核浓缩形成成熟精子必不可少的。这一过程通过过渡蛋白(transition protein,TP)替换组蛋白,反过来又被精蛋白(protamine,Prm)替换来实现,所以TP和Prm在精子细胞延伸的变态发育过程至关重要。在小鼠粗线期的精母细胞以及圆形精子细胞中,miR-469通过与基因TP2和Prm2的mRNA编码区域相结合,从而造成mRNA的降解并抑制其表达,这对于精子发生后期精子成熟具有重要作用(Dai et al., 2011)。而miR-122a在减数分裂以及减数分裂后的精子细胞中大量存在,通过与TP 2基因mRNA的3'端非翻译区相结合来抑制其表达,这表明miR-122a在精子发生后期具有重要作用(Yu et al., 2005)。在小鼠的睾丸中发现大量miR-18,并在精子发生的过程中呈特定细胞表达,通过下调热休克转录因子2(heat shock transcription factor 2)来影响胚胎发育以及配子的形成(Bjork et al., 2010)。除此之外,更多的可能调控精子变态发育过程的miRNA还有待研究。

4 miRNA相关蛋白对于精子发生的影响miRNA相关的Dicer、Drosha等蛋白在初级精母细胞减数分裂的粗线期发挥功能,其调控作用已通过大量啮齿动物基因敲除模型得到证实。由于缺少Dicer,生殖细胞的早期发育、精原细胞分化、精子变态发育及其稳定性也受到影响(Maatouk et al., 2008;Romero et al., 2011)。小鼠胚胎细胞和精原细胞由于缺少Dicer表现出低下的增生能力,而精子发生也停滞于精原细胞的早期增殖与分化阶段(Hayashi et al., 2008)。此外,通过敲除AMH基因(anti-Mullerian hormone)导致小鼠睾丸支持细胞中Dicer的缺失,并引起精子的缺陷和附睾的持续退化以及小鼠的不育(Papaioannou et al., 2009)。在出生后小鼠的精原细胞早期发育过程中,特定生殖细胞中Dicer的敲除将导致睾丸的萎缩以及曲细精管中精子发生阻滞,但最明显的缺陷表现在精子细胞的延伸阶段(Korhonen et al., 2011)。而出生后小鼠精原细胞中Dicer的敲除将导致精子发生阻滞,并伴随大量miRNA的缺失、睾丸转录组的表达失调以及性染色体基因的过度表达(Greenlee et al., 2012)。而小鼠表达有缺陷的DGCR8蛋白会增加精母细胞的凋亡以及精子细胞成熟过程中的缺陷,从而产生畸形精子甚至无精症(Zimmermann et al., 2014)。除Dicer和DGCR8外,Drosha和AGO4在精子的发生过程中也具有重要作用。Drosha对于正常精子形态的形成至关重要,其缺陷能够造成生殖细胞在减数分裂和减数分裂后的畸形(Wu et al., 2012)。而AGO4富集于精母细胞的细胞核中,使精母细胞从有丝分裂到减数分裂顺利完成,其功能的丧失将会抑制生殖细胞在减数分裂Ⅰ阶段某些特定miRNA的表达(Mathioudakis et al., 2012)。

5 总结与展望近年来大量研究已表明,miRNA在哺乳动物精子发生过程,包括有丝分裂、减数分裂以及精子变态发育阶段,都具有重要的调控作用。虽然部分miRNA的某些调控功能已得到确定,但大部分miRNA的功能尚不明确,而miRNA的详细作用机制也尚未完全阐明。在哺乳动物精子发生过程中,不同miRNA调控作用表达的空间连续性以及交互作用也有待进一步研究。此外,大部分miRNA的调控作用都是通过研究啮齿动物模型取得的,是否这些miRNA在人类及其他哺乳动物的精子发生过程中具有同样的调控作用还有待考证。最近的研究表明隐睾症患者的精原干细胞在体外能通过诱导分化形成单倍体精子并成功受精形成能发育到八细胞阶段的胚胎细胞(Yang et al., 2014),阐明其中涉及miRNA的调控作用可能为男性不育提供新的治疗方法。作为重要表观遗传调控因子的miRNA是在不改变基因序列的情况下调控基因表达,因此更多新miRNA的发现有利于开发灵活且安全的男性避孕新技术。

| Ameres SL, Zamore PD. 2013. Diversifying microRNA sequence and function[J]. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology , 14(8) : 475–488. DOI:10.1038/nrm3611 |

| Bao J, Li D, Wang L, et al. 2012. MicroRNA-449 and microRNA-34b/c function redundantly in murine testes by targeting E2F transcription factor retinoblastoma protein (E2F-pRb) pathway[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry , 287(26) : 21686–21698. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M111.328054 |

| Bartel DP. 2004. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function[J]. Cell , 116(2) : 281–297. DOI:10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5 |

| Behm-Ansmant I, Rehwinkel J, Doerks T, et al. 2006. MiRNA degradation by miRNAs and GW182 requires both CCR4: NOT deadenlase and DCPI: DCP2 decapping complexes[J]. Genes Development , 20(14) : 1885–1898. DOI:10.1101/gad.1424106 |

| Bjork JK, Sandqvist A, Elsing AN, et al. 2010. miR-18, a member of Oncomir-1, targets heat shock transcription factor 2 in spermatogenesis[J]. Development , 137(19) : 3177–3184. DOI:10.1242/dev.050955 |

| Bleckmann SC, Blendy JA, Rudolph D, et al. 2002. Activating transcription factor 1 and CREB are important for cell survival during early mouse development[J]. Molecular and Cellular Biology , 22(6) : 1919–1925. DOI:10.1128/MCB.22.6.1919-1925.2002 |

| Borchert GM, Lanier W, Davidson BL. 2006. RNA polymerase Ⅲ transcribes human microRNAs[J]. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology , 13(12) : 1097–1101. |

| Bouhallier F, Allioli N, Lavial F, et al. 2010. Role of miR-34c microRNA in the late steps of spermatogenesis[J]. RNA , 16(4) : 720–731. DOI:10.1261/rna.1963810 |

| Bruno IG, Karam R, Huang L, et al. 2011. Identification of a microRNA that activates gene expression by re-pressing nonsense-mediated RNA decay[J]. Molecular Cell , 42(4) : 500–510. DOI:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.018 |

| Chendrimada TP, Gregory RI, Kumaraswamy E, et al. 2005. TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing[J]. Nature , 436(7051) : 740–744. DOI:10.1038/nature03868 |

| Corney DC, Flesken-Nikitin A, Godwin AK, et al. 2007. MicroRNA-34b and microRNA-34c are targets of p53 and cooperate in control of cell proliferation and adhesion-independent growth[J]. Cancer Research , 67(18) : 8433–8438. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1585 |

| Dai L, Tsai-Morris CH, Sato H, et al. 2011. Testis-specific miRNA-469 up-regulated in gonadotropin-regulated testicular RNA helicase(GRTH/DDX25)-null mice silences transition protein 2 and protamine 2 messages at sites within coding region: implications of its role in germ cell development[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry , 286(52) : 44306–44318. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M111.282756 |

| Denli AM, Tops BB, Plasterk RH, et al. 2004. Processing of primary microRNAs by the microprocessor complex[J]. Nature , 432(7014) : 231–235. DOI:10.1038/nature03049 |

| Greenlee AR, Shiao MS, Snyder E, et al. 2012. Deregulated sex chromosome gene expression with male germ cell-specific loss of Dicer1[J]. PLoS ONE , 7(10) : e46359. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0046359 |

| Gregory RI, Yan KP, Amuthan G, et al. 2004. The microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs[J]. Nature , 432(7014) : 235–240. DOI:10.1038/nature03120 |

| Grishok A, Pasquinelli AE, Conte D, et al. 2001. Genes and mechanisms related to RNA interference regulate expression of the small temporal RNAs that control C.elegans developmental timing[J]. Cell , 106(1) : 23–34. DOI:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00431-7 |

| Griswold MD, Bishop PD, Kim KH, et al. 1989. Function of vitamin A in normal and synchronized seminiferous tubules[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences , 564 : 154–172. DOI:10.1111/nyas.1989.564.issue-1 |

| Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, et al. 2004. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing[J]. Genes & Development , 18(24) : 3016–3027. |

| Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, et al. 2006. Molecular basis for the recognition of primary microRNAs by the Drosha-DGCR8 complex[J]. Cell , 125(5) : 887–901. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.043 |

| Hayashi K, Chuva de Sousa Lopes SM, Kaneda M, et al. 2008. MicroRNA biogenesis is required for mouse primordial germ cell development and spermatogenesis[J]. PLoS ONE , 3(3) : e1738. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0001738 |

| Huszar JM, Pavne CJ. 2013. MicroRNA 146 (Mir146) modulates spermatogonial differentiation by retinoic acid in mice[J]. Biology of Reproduction , 88(1) : 15. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod.112.103747 |

| Hutvaqner G, McLachlan J, Pasquinelli AE, et al. 2001. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA[J]. Science , 293(5531) : 834–838. DOI:10.1126/science.1062961 |

| Julaton VT, Reijo Pera RA. 2011. NANOS3 function in human germ cell development[J]. Human Molecular Genetics , 20(11) : 2238–2250. DOI:10.1093/hmg/ddr114 |

| Ketting RF, Fischer SE, Bernstein E, et al. 2001. Dicer functions in RNA interference and in synthesis of small RNA involved in developmental timing in C[J]. elegans[J]. Genes & Development , 15(20) : 2654–2659. |

| Khvorova A, Reynolds A, Jayasena SD. 2003. Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias[J]. Cell , 115(2) : 209–216. DOI:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00801-8 |

| Kim VN. 2005. MicroRNA biogenesis: coordinated cropping and dicing[J]. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology , 6(5) : 376–385. DOI:10.1038/nrm1644 |

| Korhonen HM, Meikar O, Yadav RP, et al. 2011. Dicer is required for haploid male germ cell differentiation in mice[J]. PLoS ONE , 6(9) : e24821. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0024821 |

| Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. 1993. . elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small rnas with antisense complementarity to lin-14[J]. Cell , 75(5) : 843–854. DOI:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-Y |

| Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, et al. 2003. The nuclear RNase Ⅲ Drosha initiates microRNA processing[J]. Nature , 425(6956) : 415–419. DOI:10.1038/nature01957 |

| Li Y, Wang HY, Wan FC, et al. 2012. Deep sequencing analysis of small non-coding RNAs reveals the diversity of microRNAs and piRNAs in the human epididymis[J]. Gene , 497(2) : 330–335. DOI:10.1016/j.gene.2012.01.038 |

| Liang X, Zhou D, Wei C, et al. 2012. MicroRNA-34c enhances murine male germ cell apoptosis through targeting ATF1[J]. PLoS ONE , 7(3) : e33861. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0033861 |

| Lin SL, Chang D, Ying SY. 2005. Asymmetry of intronic pre-miRNA structures in functional RISC assembly[J]. Gene , 356 : 32–38. DOI:10.1016/j.gene.2005.04.036 |

| Liu J, Carmell MA, Rivas FV, et al. 2004. Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi[J]. Science , 305(5689) : 1437–1441. DOI:10.1126/science.1102513 |

| Lund E, Guttinger S, Calado A, et al. 2004. Nuclear export of microRNA precursors[J]. Science , 303(5654) : 95–98. DOI:10.1126/science.1090599 |

| Maatouk DM, Loveland KL, McManus MT, et al. 2008. Dicer1 is required for differentiation of the mouse male germline[J]. Biology of Reproduction , 79(4) : 696–703. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod.108.067827 |

| Mathioudakis N, Palencia A, Kadlec J, et al. 2012. The multiple Tudor domain-containing protein TDRD1 is a molecular scaffold for mouse Piwi proteins and piRNA biogenesis factors[J]. RNA , 18(11) : 2056–2072. DOI:10.1261/rna.034181.112 |

| Millar AA, Waterhouse PM. 2005. Plant and animal microRNAs: similarities and differences[J]. Functional & Integrative Genomics , 5(3) : 129–135. |

| Moritoki Y, Hayashi Y, Mizuno K, et al. 2014. Expression profiling of microRNA in cryptorchid testes: miR-135a contributes to the maintenance of spermatogonial stem cells by regulating FoxO1[J]. The Journal of Urology , 191(4) : 1174–1180. DOI:10.1016/j.juro.2013.10.137 |

| Niu Z, Goodyear SM, Rao S, et al. 2011. MicroRNA-21 regulates the self-renewal of mouse spermatogonial stem cells[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 108(31) : 12740–12745. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1109987108 |

| Oatley JM, Brinster RL. 2008. Regulation of spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal in mammals[J]. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology , 24 : 263–286. DOI:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175355 |

| Olde Loohuis NF, Kos A, Martens GJ, et al. 2012. MicroRNA networks direct neuronal development and plasticity[J]. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences , 69(1) : 89–102. DOI:10.1007/s00018-011-0788-1 |

| Olsen PH, Ambros V. 1999. The lin-4 regulatory RNA controls developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans by blocking LIN-14 protein synthesis after the initiation of translation[J]. Developmental Biology , 216(2) : 671–680. DOI:10.1006/dbio.1999.9523 |

| Papaioannou MD, Pitetti JL, Ro S, et al. 2009. Sertoli cell dicer is essential for spermatogenesis in mice[J]. Developmental Biology , 326(1) : 250–259. DOI:10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.011 |

| Persengiev SP, Green MR. 2003. The role of ATF/CREB family members in cell growth, survival and apoptosis[J]. Apoptosis , 8(3) : 225–228. DOI:10.1023/A:1023633704132 |

| Pillai RS, Bhattacharyya SN, Artus CG. 2005. Inhibition of translational initiation by let-7 microRNA in human cells[J]. Science , 309(5740) : 1573–1576. DOI:10.1126/science.1115079 |

| Pratt AJ, MacRae IJ. 2009. The RNA-induced silencing complex: a versatile gene-silencing machine[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry , 284(27) : 17897–17901. DOI:10.1074/jbc.R900012200 |

| Romero Y, Meikar O, Papaioannou MD, et al. 2011. Dicer1 depletion in malegerm cells leads to infertility due to cumulative meiotic and spermatogenic defects[J]. PLoS ONE , 6(10) : e25241. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0025241 |

| Sada A, Hasegawa K, Pin PH, et al. 2012. NANOS2 acts downstream of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor signaling to suppress differentiation of spermatogonial stem cells[J]. Stem Cells , 30(2) : 280–291. DOI:10.1002/stem.790 |

| Schwarz DS, Hutvagner G, Du T, et al. 2003. Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex[J]. Cell , 115(2) : 199–208. DOI:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00759-1 |

| Shen R, Xie T. 2010. NANOS: a germline stem cell's guardian angel[J]. Journal of Molecular Cell Biology , 2(2) : 76–77. DOI:10.1093/jmcb/mjp043 |

| Slack FJ, Basson M, Liu Z, et al. 2000. The lin-41 RBCC gene acts in the C[J]. elegans heterochronic pathway between the let-7 regulatory RNA and the LIN-29 transcription factor[J]. Molecular Cell , 5(4) : 659–669. |

| Suzuki A, Saga Y. 2008. Nanos2 suppresses meiosis and promotes male germ cell differentiation[J]. Genes Development , 22(4) : 430–435. DOI:10.1101/gad.1612708 |

| Tong MH, Mitchell D, Evanoff R, et al. 2011. Expression of Mirlet7 family microRNAs in response to retinoic acid-induced spermatogonial differentiation in mice[J]. Biology of Reproduction , 85(1) : 189–197. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod.110.089458 |

| Tong MH, Mitchell DA, McGowan SD, et al. 2012. Two miRNA clusters, Mir-17-92 (Mi-rc1) and Mir-106b-25 (Mirc3), are involved in the regulation of spermatogonial differentiation in mice[J]. Biology of Reproduction , 86(3) : 72. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod.111.096313 |

| Tscherner A, Gilchrist G, Smith N, et al. 2014. MicroRNA-34 family expression in bovine gametes and preimplantation embryos[J]. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology , 12 : 85. DOI:10.1186/1477-7827-12-85 |

| Tyagi G, Carnes K, Morrow C, et al. 2009. Loss of Etv5 decreases proliferation and RET levels in neonatal mouse testicular germ cells and causesan abnormal first wave of spermatogenesis[J]. Biology of Reproduction , 81(2) : 258–266. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod.108.075200 |

| Vasudevan S, Tong Y, Steitz JA. 2007. Switching from repression to activation: micro-RNAs can up-regulate translation[J]. Science , 318(5858) : 1931–1934. DOI:10.1126/science.1149460 |

| Wang Y, Medvid R, Melton C, et al. 2007. DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal[J]. Nature Genetics , 39(3) : 380–385. DOI:10.1038/ng1969 |

| Westholm JO, Lai EC. 2011. Mirtrons: microRNA biogenesis via splicing[J]. Biochimie , 93(11) : 1897–1904. DOI:10.1016/j.biochi.2011.06.017 |

| Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. 1993. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C[J]. elegans[J]. Cell , 75(5) : 855–862. DOI:10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4 |

| Wu J, Bao J, Kim M, et al. 2014. Two miRNA clusters, miR34b/c and miR-449, are essential for normal brain development, motile ciliogenesis, and spermatogenesis[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of Ameria , 111(28) : E2851–7. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1407777111 |

| Wu Q, Song R, Ortogero N, et al. 2012. The RNase Ⅲ enzyme DROSHA is essential for microRNA production and spermatogenesis[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry , 287(30) : 25173–25190. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M112.362053 |

| Yang S, Ping P, Ma M, et al. 2014. Generation of haploid spermatids with fertilization and development capacity from human spermatogonial stem cells of cryptorchid patients[J]. Stem Cell Reports , 3(4) : 663–675. DOI:10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.08.004 |

| Yao C, Liu Y, Sun M, et al. 2015. MicroRNAs and DNA methylation as epigenetic regulators of mitosis, meiosis and spermiogenesis[J]. Reproduction , 150(1) : R25–34. DOI:10.1530/REP-14-0643 |

| Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, et al. 2003. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs[J]. Genes Development , 17(24) : 3011–3016. DOI:10.1101/gad.1158803 |

| Yu M, Mu H, Niu Z, et al. 2014. miR-34c enhances mouse spermatogonial stem cells differentiation by targeting Nanos2[J]. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry , 115(2) : 232–242. DOI:10.1002/jcb.24655 |

| Yu Z, Raabe T, Hecht NB. 2005. MicroRNA Mirn122a reduces expression of the posttranscriptionally regulated germ cell transition protein 2 (Tnp2) messenger RNA (mRNA) by mRNA cleavage[J]. Biology of Reproduction , 73(3) : 427–433. DOI:10.1095/biolreprod.105.040998 |

| Zhang X, Zeng Y. 2010. The terminal loop region controls microRNA processing by Drosha and Dicer[J]. Nucleic Acids Research , 38(21) : 7689–7697. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkq645 |

| Zickler D, Kleckner N. 1998. The leptotene-zygotene transition of meiosis[J]. Annual Review of Genetics , 32 : 619–754. DOI:10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.619 |

| Zimmermann C, Romero Y, Warnefors M, et al. 2014. Germ cell-specific targeting of DICER or DGCR8 reveals a novel role for endo-siRNAs in the progression of mammalian spermatogenesis and male fertility[J]. PLoS ONE , 9(9) : E107023. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0107023 |

2016, Vol. 35

2016, Vol. 35