The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- Xin LAI, Yuanfa GONG. 2017.

- Relationship between Atmospheric Heat Source over the Tibetan Plateau and Precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing Region during Summer. 2017.

- J. Meteor. Res., 31(3): 555-566

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-017-6045-2

Article History

- Received May 3, 2016

- in final form October 7, 2016

The Sichuan–Chongqing region is located in inland China. It marks a transition zone between large-scale plateau topography and China’s eastern plains. It has a subtropical climate, influenced by tropical and subtropical monsoons; however, its climate exhibits great variation and periods of flood/drought occur with high frequency. Consequently, many studies have investigated the different aspects of these phenomena in this region (Li and Rui, 1997; Tan and Ma, 1997; Chen and Hao, 2001; Qi et al., 2011; Liao et al., 2012). Many factors affect the flood/drought in the Sichuan–Chongqing region. Luo et al. (1982) used data over a 13-yr period to unravel a relation between the South Asian high and the floods/droughts in eastern China. They found that when the South Asian high is situated to the east, floods tend to occur in western Sichuan Province. Conversely, a westerly circulation pattern brings rainy weather to eastern Sichuan , resulting in floods, whereas no rain (drought) occurs in the west of Sichuan. Li (2000) also highlighted that, during periods of severe drought (flood) on the eastern side of the Tibetan Plateau (TP), the preceding 100-hPa height over the TP is low (high); during June and July, the South Asian high body and center are further north (south) and west (east) than normal, and the 100-hPa height exhibits negative (positive) departures over the eastern side of the TP. Ma et al. (2003) showed that when the monsoon is weakened, the TP’s monsoon low pressure is situated further west, and the Sichuan basin experiences drought in early summer. Conversely, during flood years, the monsoon is strong and the low pressure is further east. Zhou et al. (2008, 2011) and Chen et al. (2010) analyzed drought–flood coexistence in the west and east of the Sichuan–Chongqing basin from the perspective of large-scale circulation, and Cen et al. (2014a) from the perspective of the atmospheric heat source (<Q1>) over the TP and its surrounding areas. The different patterns of water vapor transport in drought and flood years in the Sichuan–Chongqing region were also investi-gated by Jiang et al. (2007) and Mao et al. (2010).

Droughts and floods are actually a reflection of atmospheric circulation anomalies, and these anomalies are often forced by <Q1>. The TP is the highest and the most complex plateau on the earth; it exerts a huge heat source on the atmosphere in the Northern Hemisphere during boreal spring and summer (Flohn, 1957, 1960; Ye and Gao, 1979), and the thermal forcing of the TP plays an important role in China’s climate and weather. In spring, the thermal conditions over the TP are represented by sensible heat, and there has been a significant decreasing trend in spring sensible heat over the TP during the last three decades, and these reductions in sensible heat over the TP have weakened the monsoon circulation and postponed the seasonal reversal of the land–sea thermal contrast in East Asia, thus having an important influence on the precipitation in China in summer (Duan et al., 2008, 2011, 2012a, b; Wang et al., 2014).

In summer, the atmosphere over the TP in the upper troposphere acts as a heat source (Ye and Gao, 1979), and <Q1> over the eastern TP in summer exhibits a good positive correlation with summer rainfall over the Yangtze River basin and its surround regions (Yang, 2001; Jian et al., 2004, 2006). When <Q1> over the TP is strengthened, anomalous southwesterly airflow prevails at lower levels over South China and, at the same time, there is northerly wind anomaly to the north of the Yangtze River, which strengthens the convergence at lower levels over the Yangtze River basin. The convection over eastern and southern Asian monsoon areas is strengthened, and the precipitation from Sichuan to the lower Yangtze River is larger than normal (Zhao and Chen, 2001a, b; Zhou et al., 2009). Jiang et al. (2016) pointed out that the enhanced convection over southeastern TP may feed back positively to the precipitation over southeastern TP by pumping more water vapor from the southern boundary, since the latent heat over southeastern TP could induce lower-tropospheric southwesterly flow to the southeast of the TP. The thermal conditions over the TP also cause changes in the circulation in mid–high latitudes (i.e., the Tibetan high and western Pacific subtropical high), subsequently influencing rainfall over North China (Zhao et al., 2003), and <Q1> over the TP also impacts the plateau monsoon (Cen et al., 2014b; Bai and Hu, 2016). The vertical profile of <Q1> over the TP can also influence the precipitation over Northwest China by affecting the vertical circulation over the TP and its surrounding area (Wei et al., 2009). These studies raise the question of whether <Q1> is important to occurrences of floods/droughts in the Sichuan–Chongqing region. Therefore, in this paper, the relationship between <Q1> and the precipitation over the Sichuan–Chongqing region during summer is studied by using composite and correlation analysis. Through determining the possible causes for the rainfall anomalies, it is expected that the occurrence of floods/droughts in the Sichuan–Chongqing region can be understood more comprehensively.

2 Data and methodsA daily precipitation dataset from 42 meteorological stations in the Sichuan–Chongqing region, compiled by the Chinese National Meteorological Information Center from 1961 to 2007, is used in this study. This is complemented by NCEP–NCAR reanalysis data on a 2.5° × 2.5° grid from 1961 to 2007, which include surface pressure, temperature, vertical velocity, zonal and meridional wind components at 17 standard pressure levels, and relative humidity at 8 levels.

The apparent heat source Q1 (Yanai et al., 1973) is computed from

| ${Q_1} = {c_p}\left[ {\frac{{\partial T}}{{\partial t}} + {V} \cdot \nabla T + {{\left({\frac{p}{{{p_0}}}} \right)}^k}\omega \frac{{\partial \theta }}{{\partial p}}} \right], $ | (1) |

where T is the temperature; θ is the potential temperature; ω is the vertical p-velocity; p0 = 1000 hPa; k = R/cp; R and cp are the gas constant and the specific heat at constant pressure of dry air, respectively; and V is the horizontal wind. The heat source of the whole air column is calculated through the vertical integration of Q1 from pt (= 100 hPa) to ps (the pressure at the ground surface):

| $\begin{array}{l} \left\langle {{Q_1}} \right\rangle = \frac{1}{g}\int_{{p_{\rm{t}}}}^{{p_{\rm{s}}}} {{Q_1}} \;{\rm{d}}p\\ = \frac{{{c_p}}}{g}\int_{{p_{\rm{t}}}}^{{p_{\rm{s}}}} {\left[ {\frac{{\partial T}}{{\partial t}} + V \cdot \nabla T + {{\left( {\frac{p}{{{p_0}}}} \right)}^k}\omega \frac{{\partial \theta }}{{\partial p}}} \right]{\rm{d}}p} . \end{array}$ | (2) |

The parameter <Q1> consists of the local time change term, the horizontal advection term, and the vertical advection term.

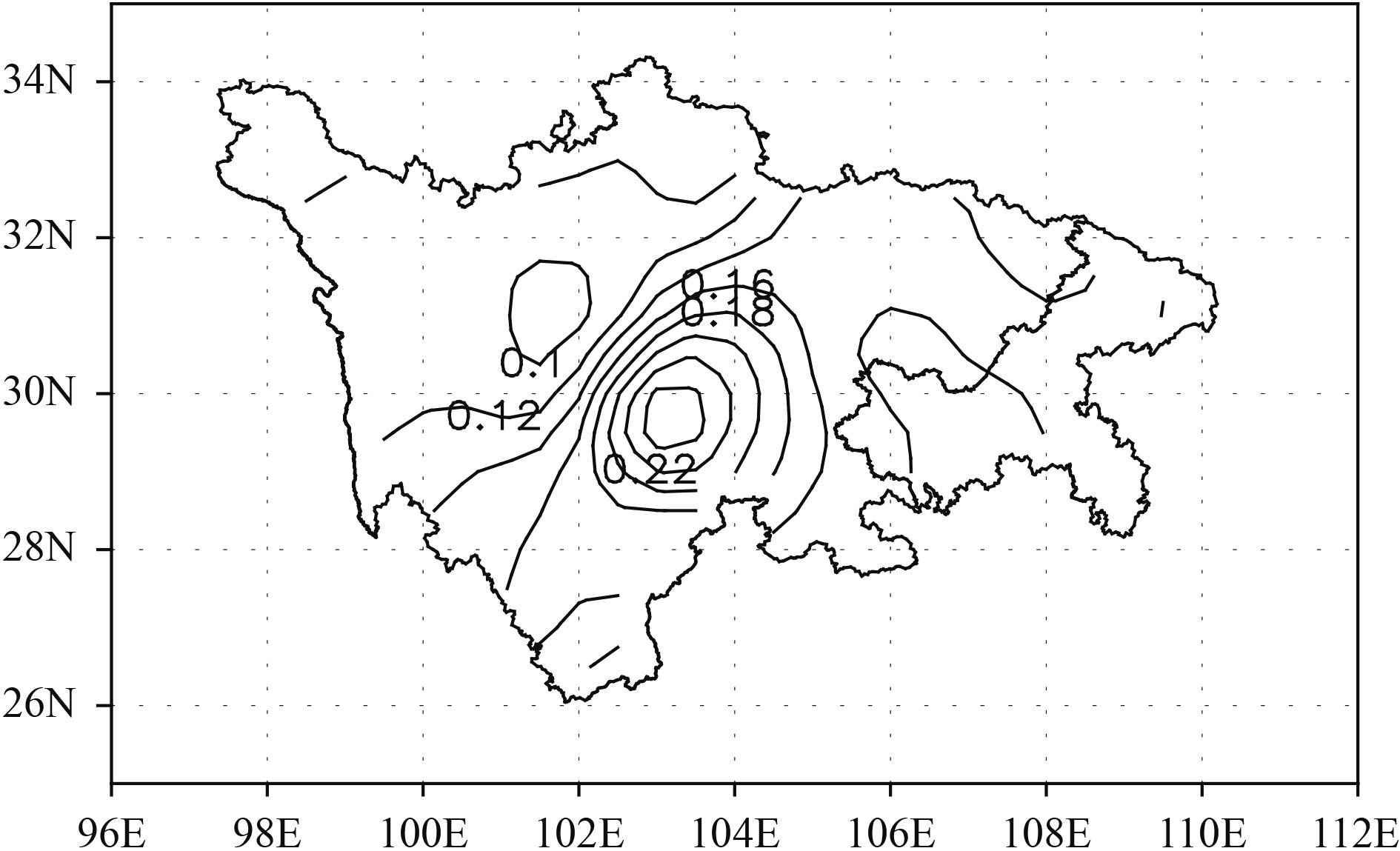

3 Variation of summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing regionTo clarify the features of the variation of regional precipitation, the dataset between 1961 and 2007 from the 42 stations is analyzed by using the empirical orthogonal function. The variance of the first eigenvector accounts for 94.2%, representing the average conditions of many years, and reflecting the distribution of summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region. The first eigenvector is shown in Fig. 1. It can be seen that the Sichuan–Chongqing region is a positive area, which includes the regions of Ya’an, Leshan, Chengdu, and Yibin, constituting an area with an isotimic value exceeding 0.16; therefore, the summer precipitation center is located over this region. We choose the entire Sichuan–Chongqing region for our investigation of the summer precipitation anomaly.

|

| Figure 1 Spatial distribution of the first empirical orthogonal function mode for precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region in summer. |

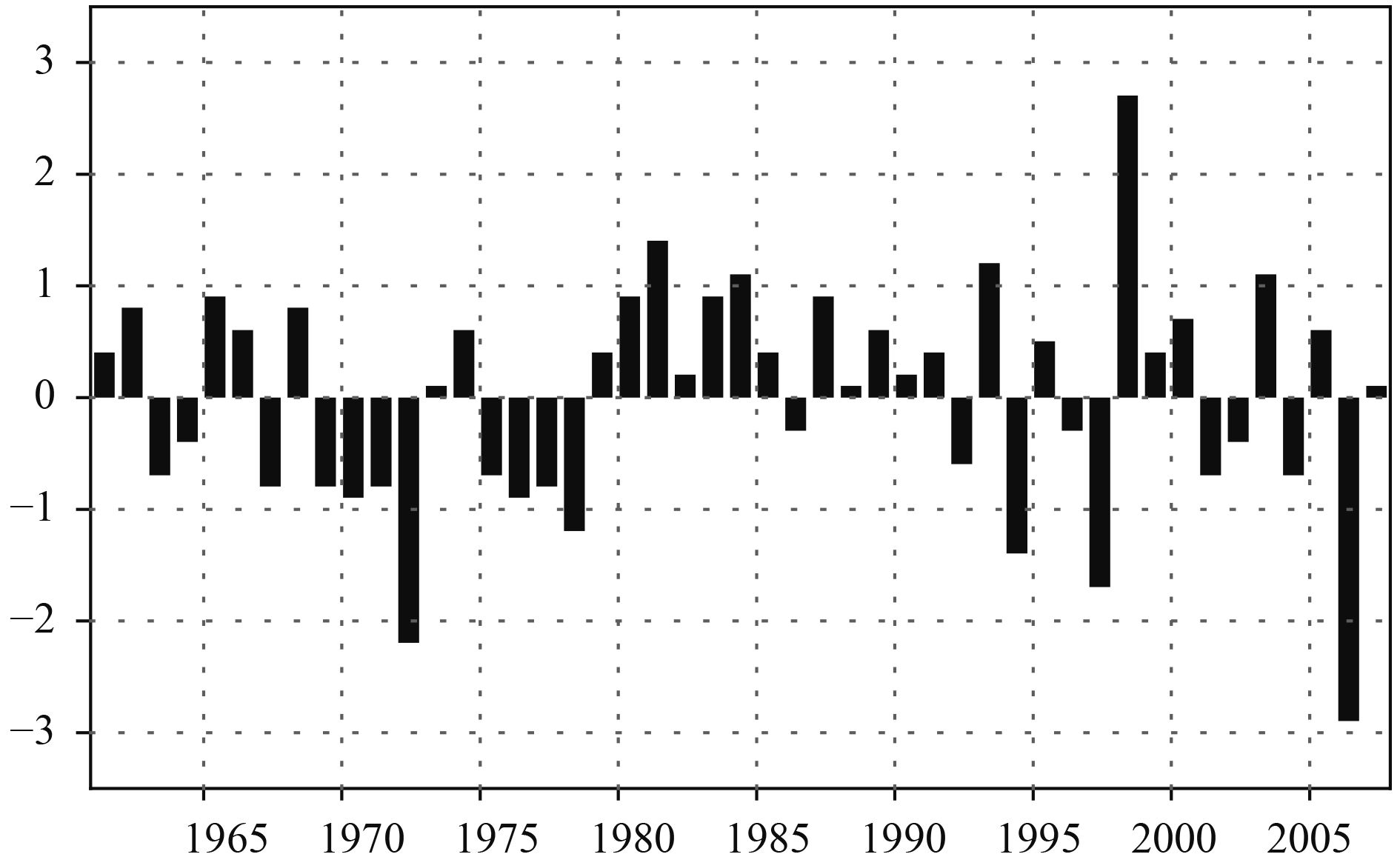

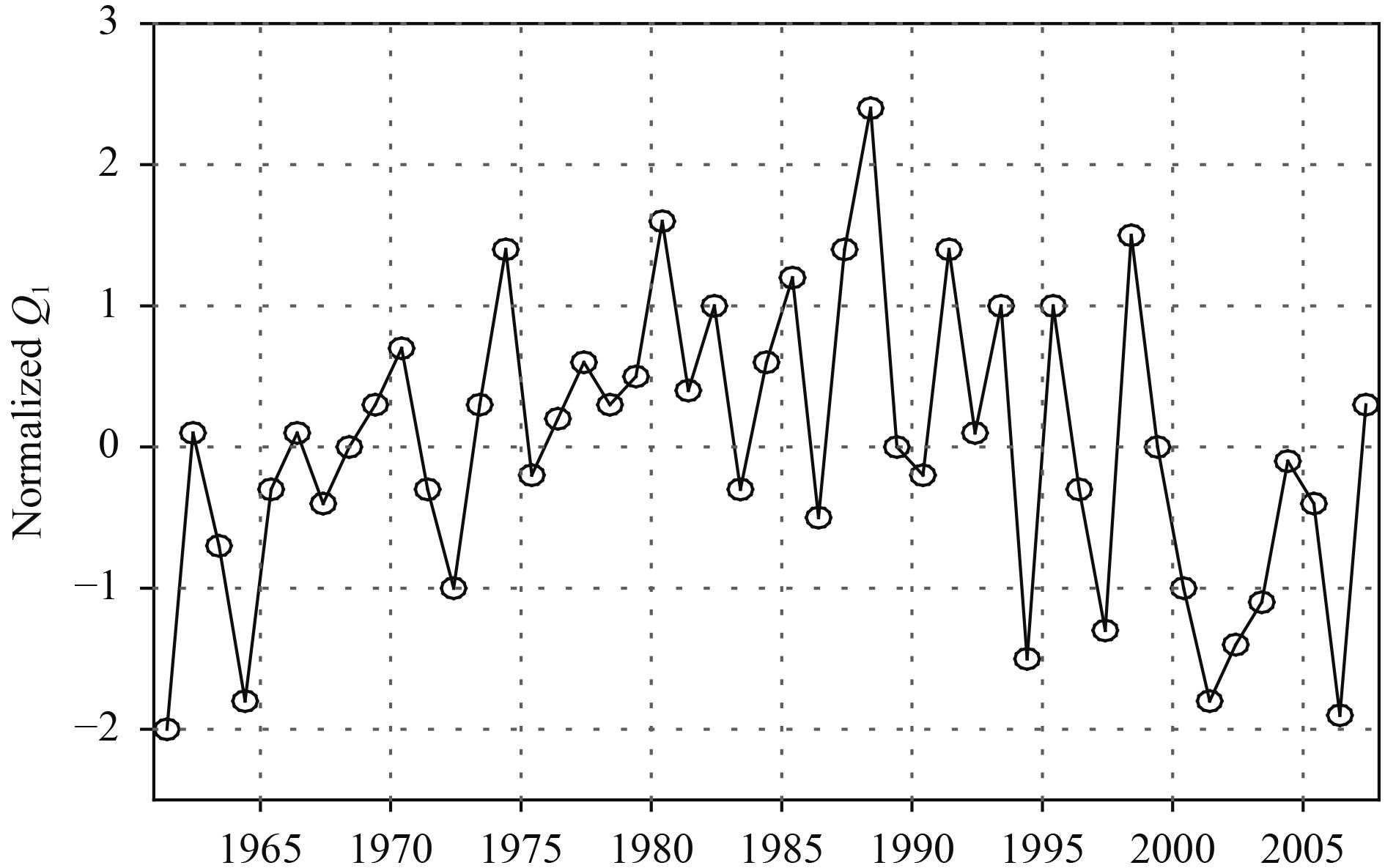

Figure 2 depicts the normalized precipitation of the 42 meteorological stations, revealing that the precipitation possesses remarkable interannual variation. In the 1970s, the precipitation in summer is less than normal and, in the 1980s, it is greater than normal. From the early 1990s, there is a noticeable trend of interannual variation in summer precipitation, and the years with the greatest and least precipitation emerge as 1998 and 2006, respectively. To study the causes of the summer precipitation anomalies in the Sichuan–Chongqing region, five years are selected (1981, 1984, 1993, 1998, and 2003) in which the value of normalized precipitation exceeds one standard deviation in Fig. 2, representing greater precipitation than normal. A further five years (1972, 1978, 1994, 1997, and 2006) are selected in which the value of normalized precipitation is below one negative standard deviation, representing precipitation that is less than normal.

|

| Figure 2 Time series of normalized precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region in summer. |

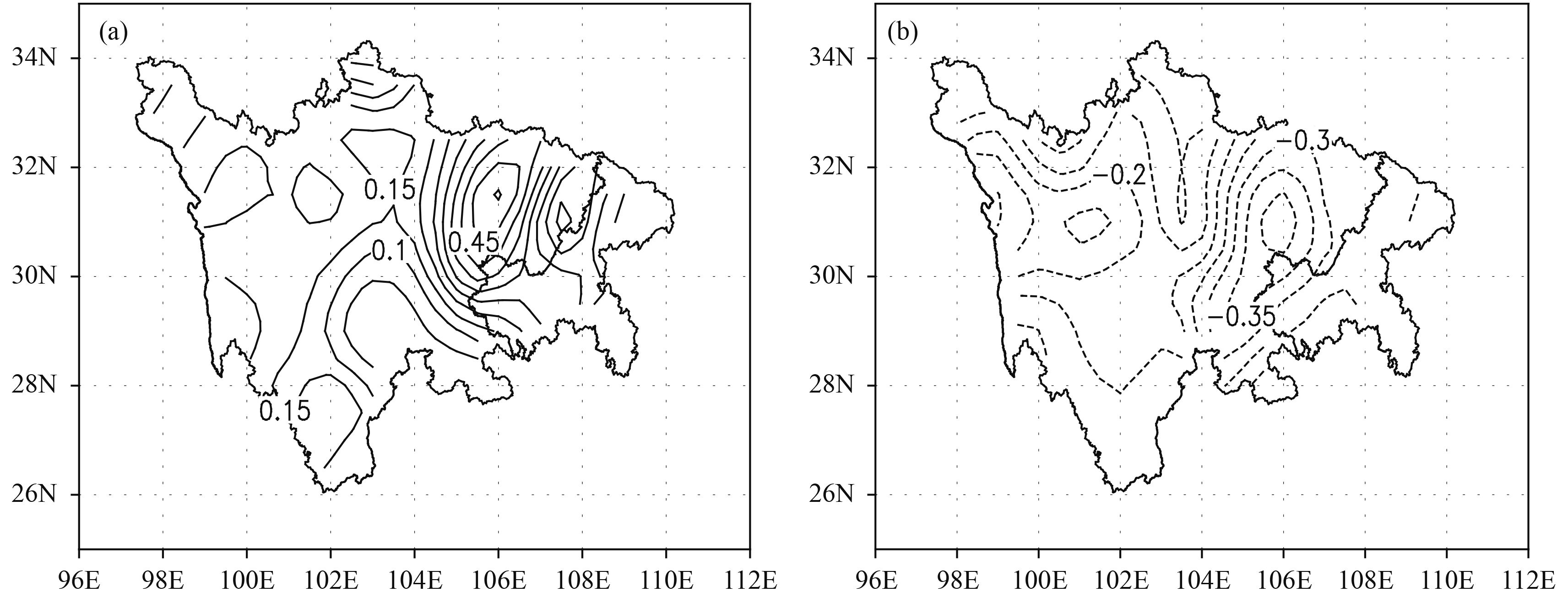

One may question whether it is reasonable to choose the entire Sichuan–Chongqing region for the study of precipitation. Figure 3 depicts the composite departure percentage precipitation distribution for those years with greater and less precipitation. For the years of greater precipitation, shown in Fig. 3a, the precipitation across the entire Sichuan–Chongqing region is 10% higher than normal. The precipitation over northeastern and northwestern Sichuan basin and most of the central Sichuan basin is over 30% higher than normal; the center of this zone in Langzhong is in excess of 50% higher than normal. Conversely, for the years with less precipitation (Fig. 3b), the precipitation across the entire Sichuan–Chongqing region is 10% below normal. In northeastern and northwestern Sichuan basin and most of the central Sichuan basin, the precipitation is 30% below normal; the center of this zone in Nanchong is 40% below normal. Therefore, the summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region has a consistent trend of increase or decrease; it is reasonable to select the entire Sichuan–Chongqing region for the study of the precipitation anomalies.

|

| Figure 3 The precipitation anomaly departure percentage of (a) greater and (b) less precipitation years in the Sichuan–Chongqing region. |

Zhao and Chen (2001a) reported that <Q1> during spring over the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau is a good indicator of subsequent summer rainfall over the valleys of the Yangtze and Huaihe River. Liu et al. (2002) showed that the diabatic heating over the southern and southeastern TP is stronger than normal, which forces a Rossby wave train to induce the western Pacific subtropical high to move southward, and the convergence of the south and north flows over the Huaihe River results in more rainfall in this region. The Sichuan–Chongqing region is located in the eastern TP, and it marks a transition zone between large-scale plateau topography and China’s eastern plains; thus, the precipitation anomalies are also affected by <Q1> over the TP. In summer, the average value of <Q1> over the TP is 93.61 W m–2, and the average values of the vertical advection term, the horizontal advection term, and the local time change term, which constitute <Q1>, are 106.36, –16.85, and 4.1 W m–2, respectively. Because the value of the horizontal advection term is negative, offsetting part of the heat source, the value of the vertical advection term is bigger than <Q1>. Furthermore, the value of the local time change term is relatively small, so the vertical advection term and the horizontal advection term have an important influence on <Q1> over the TP. Meanwhile, the correlation between <Q1> and the vertical advection term, and the correlation between <Q1> and the horizontal advection term are calculated, and the correlation coefficients are 0.72 and 0.39, respectively, both passing the 99% confidence level; however, the correlation between <Q1> and the local time change term is only –0.05. This shows that <Q1> over the TP is closely related to the vertical advection term and the horizontal advection term. Therefore, separating <Q1> into its three components is necessary for this study. To determine which term affects precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region the most, this section investigates the relationship between the atmospheric heat source (including the individual local time term, the horizontal advection term, and the vertical advection term) and the summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region.

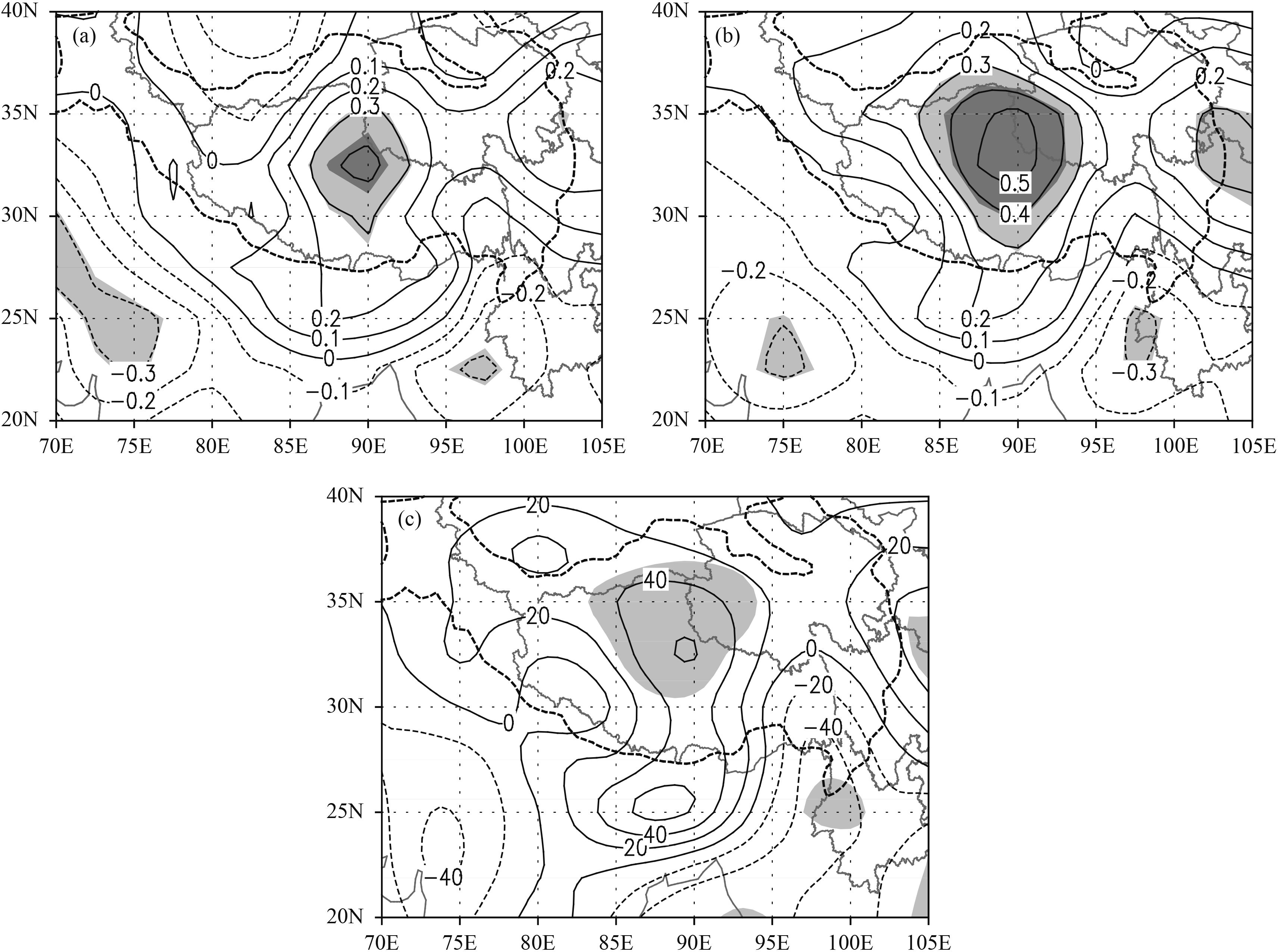

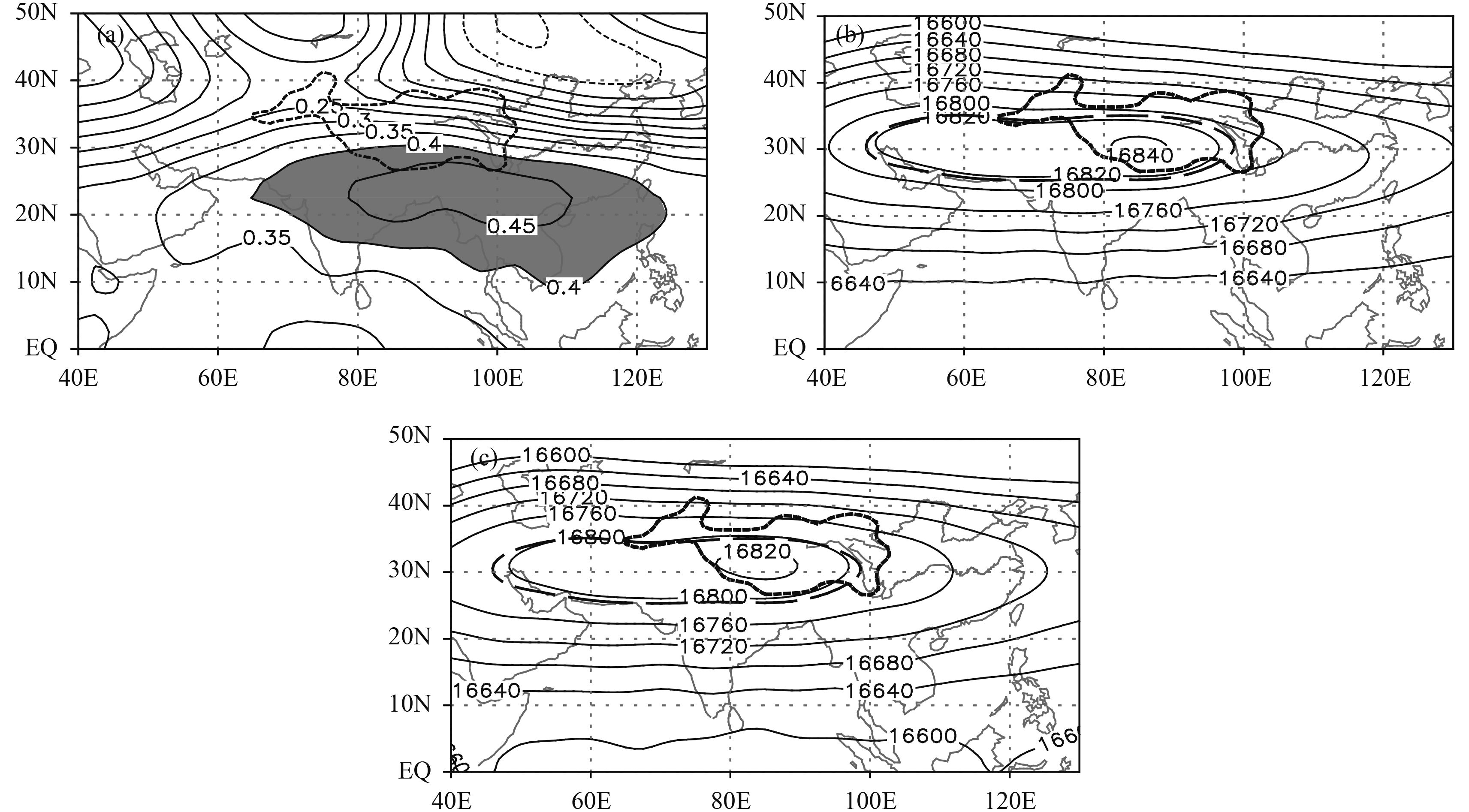

To investigate the relationship between <Q1> over the TP and the summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region, correlation analysis is conducted between the summer precipitation and <Q1>, as well as the local time change term, the horizontal advection term, and the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the TP. Figure 4a depicts the correlation of <Q1> over the TP with precipitation. The correlation passes the statistical test at the 95% confidence level in most parts of the central TP, and the central values pass the test at the 99% confidence level. Figure 4b shows the correlation between the vertical advection term over the TP and precipitation, which exhibits remarkable positive values over the central TP. Compared with Fig. 4a, the region that passes the test at the 95% confidence level is extended significantly to cover almost the entire central TP. The correlation coefficients over most parts of the central TP pass the test at the 99% confidence level. The precipitation has negative correlation with the horizontal advection term of <Q1> over northern central TP, whereas it has positive correlation with the local time change term over southern TP; however, only a small region passes the test at the 95% confidence level. Thus, over the central TP, the vertical advection term of <Q1> has a more significant effect on summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region than either <Q1>, the local time change term, or the horizontal advection term of <Q1>.

|

| Figure 4 Correlation between precipitation anomalies and the (a) <Q1> (atmospheric heat source) and (b) vertical advection term of <Q1>, over the TP, and (c) the composite difference in the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the TP between the years of greater and less precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region. The thick dashed line indicates the topography higher than 3000 m. Light (dark) shading indicates the 95% (99%) confidence level, as determined by the Student’s t test. |

The composite difference distribution of <Q1>, the local time change term, the vertical advection term, and the horizontal advection term of <Q1> over the TP and its adjacent regions in the Sichuan–Chongqing region, between the years of greater and less precipitation, is determined. It is shown that the composite difference distributions of <Q1>, the local time change term, and the horizontal advection term, over the TP and its adjacent regions, are not significantly different between the years of greater and less precipitation. However, in relation to the vertical advection term of <Q1> (Fig. 4c), there is a significant heat source region (passing the statistical test at the 95% confidence level) located in the central TP, for which a central value above 60 W m–2 is found near 33°N, 90°E. Therefore, the value of the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is strengthened in the years of greater precipitation, whereas the values of <Q1>, the local time change term, and the horizontal advection term, exhibit no significant difference. This is further testament to the fact that the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP has an important influence on the summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region. When the value of the vertical advection term of <Q1> is strengthened, the precipitation increases, and vice versa. Thus, we select the central TP (27.5°–37.5°N, 85°–95°E) as the key area that affects the precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region, and use the average value of the vertical advection term of <Q1> over this region as a key parameter.

To further investigate the relationship between the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP and summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region, the normalized mean of the vertical advection term of <Q1> in the key area is computed (Fig. 5). Figures 5 and 2 show that the change trend of the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP has a significant correlation with the precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region; the correlation coefficient is 0.485 and it passes the statistical test at the 99% confidence level. Especially in the years of greater precipitation (1981, 1984, 1993, and 1998), the vertical advection of <Q1> is strengthened, while it is weakened in the years of less precipitation (1972, 1994, 1997, and 2006). Thus, the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP indeed has an important influence on the summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region.

|

| Figure 5 Time series of the normalized mean vertical advection term of <Q1> (atmospheric heat source) over the central Tibetan Plateau from 1961 to 2007. |

Section 4 shows that the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP has an important influence on the summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region. We infer that <Q1> over the TP may also affect the circulation, weather, and climate over the TP and its adjacent regions. Thus, in this section, the relationship between the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP and the atmospheric circulation is discussed, and the causes for the anomalies of summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing are analyzed.

5.1 Upper tropospheric circulationPrevious studies have demonstrated that summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region is related closely to the South Asian high (Luo et al., 1982; Li, 2000). Thus, we begin by analyzing the effect of the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP on the South Asian high. Figure 6a shows the distribution of the correlation coefficient between the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP and the 100-hPa geopotential height field. The area in which the positive correlation passes the 99% confidence level can be seen to extend from the Indian Peninsula, across the Bay of Bengal, to the South China Sea. Therefore, when the value of the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is strengthened, the 100-hPa geopotential height is also strengthened from the Indian Peninsula, across the Bay of Bengal, to the South China Sea. This results in a shift of the South Asian high further than normal to the south and east. Li (2000) highlighted that this circulation pattern is favorable for enhanced precipitation to occur over the eastern side of the TP. Meanwhile, Fig. 6b presents the composite 100-hPa geopotential height field for the years of greater precipitation, which reveals an eastern ridge point of 16800 gpm located near 105°E, and a ridge line located near 30°N. Compared with the multi-year mean of the 100-hPa geopotential height field, the South Asian high is revealed to shift further than normal to the south and east. This is validated further by the fact that when the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is strengthened, the South Asian high shifts further than normal to the south and east, which leads to greater precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region. Conversely, when the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is weakened, the South Asian high shifts further than normal to the north and west. This circulation pattern is similar to the composite 100-hPa geopotential height field in the years of less precipitation (Fig. 6c), and results in less summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region.

|

| Figure 6 (a) Correlation between the vertical advection term of <Q1> (atmospheric heat source) over the central Tibetan Plateau and 100-hPa height field, and (b, c) the composite of 100-hPa height field for the (b) greater and (c) less precipitation years in the Sichuan–Chongqing region. The thick short dashed line indicates the topography higher than 3000 m. The shaded regions in (a) indicate the greater than 99% confidence level. The thicker long dashed line in (b, c) indicates the multi-year mean (16800 gpm). |

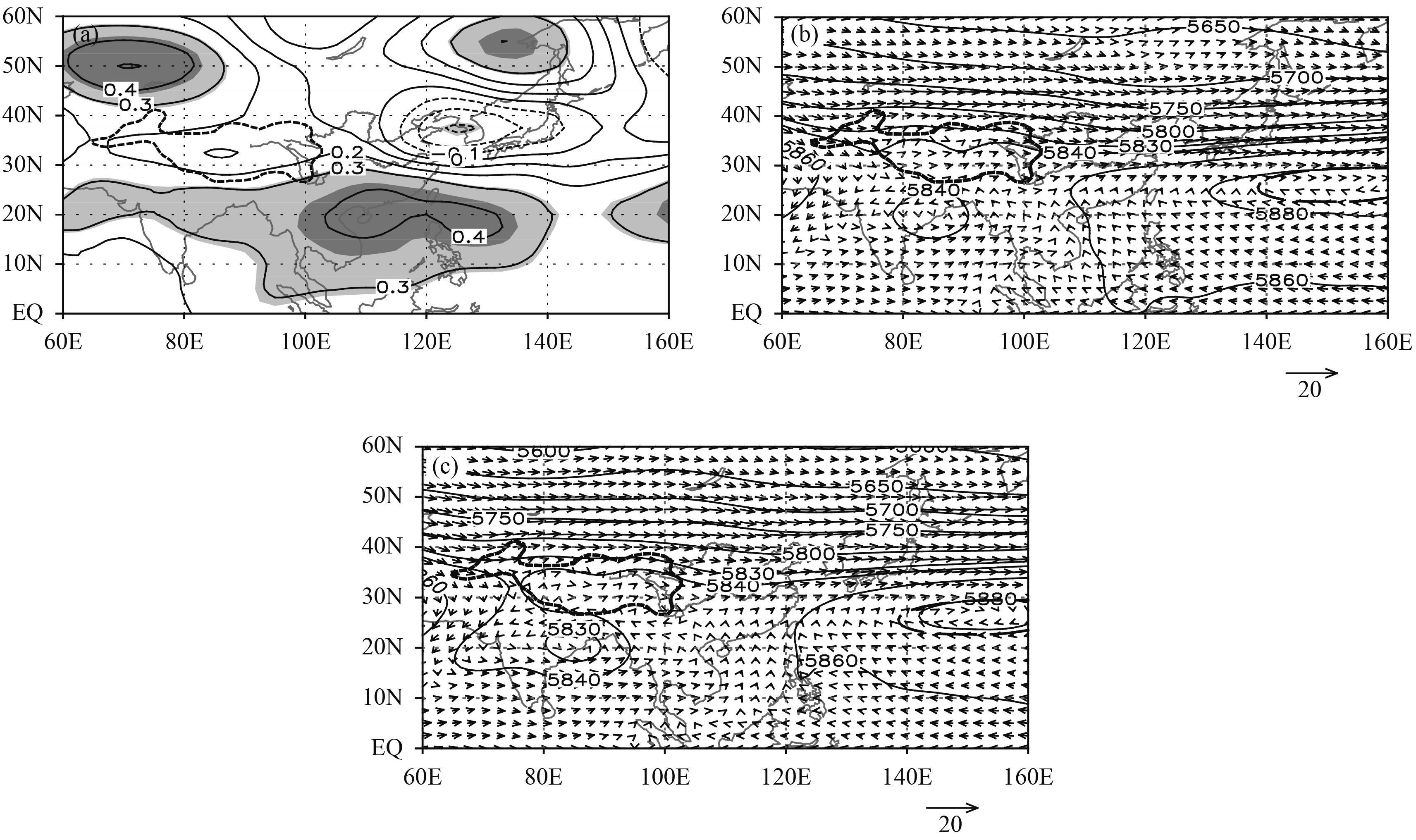

Figure 7a shows the distribution of the correlation coefficient between the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP and the 500-hPa geopotential height field. In the low latitude regions, the area in which the positive correlation coefficient passes the statistical test at the 95% confidence level covers a wide range from the Indian Peninsula, across the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea, to the east of the Philippines. Moreover, the area from northern South China Sea to the east of the Philippines passes the test at the 99% confidence level. This indicates that when the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is strengthened, the 500-hPa geopotential height from the Indian Peninsula, across the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea, to the east of the Philippines, is also strengthened. This is beneficial to the shift of the western Pacific subtropical high further than normal to the south and west, and the Indian low is weakened, which leads to warm moist air moving from the low latitude oceans to the Sichuan–Chongqing region. In the high latitudes, there is a positive correlation region located in the Ural Mountains and its adjacent regions and in northeastern Northeast China (passing the statistical test at the 95% confidence level), which is conducive to the formation of two ridges and one trough, leading to dry cool air moving southward to the Sichuan–Chongqing region. Conversely, when the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is weakened, the position of the South Asian high moves to the north and west, the subtropical high moves further to the east and north, and the Indian low is strengthened. This circulation pattern is unfavorable for the movement of warm moist air from the low latitude oceans toward the Sichuan–Chongqing region. Similarly, it becomes difficult for the dry cool air in the north to move southward when there are two troughs and one ridge in the high latitudes.

|

| Figure 7 (a) Correlation between the vertical advection term of <Q1> (atmospheric heat source) over the central Tibetan Plateau and the 500-hPa height field, and (b, c) the composite of 500-hPa height and wind fields for years with (b) greater and (c) less precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region. The thick short dashed line indicates the topography higher than 3000 m. Light (dark) shading in (a) indicates the greater than 95% (99%) confidence level. The thick long dashed line in (b, c) indicates the multi-year mean (5880 gpm). |

Figures 7b and 7c present the composite 500-hPa geopotential height field and wind field in the years of greater and less precipitation, respectively. For years of greater precipitation (Fig. 7b), the Indian low is significantly weaker than in years of less precipitation (Fig. 7c). The western Pacific subtropical high is strengthened, and the ridge line of 5880 gpm of the subtropical high is further to the west and south relative to the multi-year mean. This causes the southeasterly winds on the west side of the subtropical high to advance to the Sichuan–Chongqing region. Then, they shift to southwesterly and converge with the westerly from the midlatitudes, forming a circulation pattern that is beneficial for enhanced precipitation in this region. In the years of less precipitation (Fig. 7c), the subtropical high is weakened, and the ridge line of 5880 gpm is further to the east and north relative to the multi-year mean. This causes the easterly flow on the south side of the subtropical high to shift completely to the south on the east side of 110°N, and is thus unable to advance westward to the Sichuan–Chongqing region. Therefore, the Sichuan–Chongqing region is affected by the westerly flow from the midlatitudes; as the Indian low is strengthened, the westerly flow shifts into northeasterly, which enhances the divergence over the Sichuan–Chongqing region, leading to reduced precipitation.

To sum up, when the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is strengthened (weakened), the western Pacific subtropical high shifts further than normal to the south and west (east and north), the Indian low is weakened (strengthened), and two ridges and one trough (two troughs and one ridge) form in the high latitudes, which lead to greater (less) precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region.

5.3 Lower tropospheric circulationThe monsoon readily influences the summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region because of its special geographical position. Figure 8a presents the distribution of the correlation coefficient between the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP and the 850-hPa wind field. When the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is strengthened, there is a significant belt of easterly winds extending from the Arabian Sea across the Bay of Bengal to the eastern Philippines Sea. Part of this shifts into a southerly wind over the Indochina Peninsula and the Bay of Bengal and its adjacent regions, and advances northward to the south of the TP, and a counterclockwise circulation occurs along the edge of the TP, entering the Sichuan–Chongqing region. On the other hand, a cyclonic circulation locates in the Yellow and Japan seas and adjacent regions to the north of 20°N, and a northeasterly wind on the circulation’s northwest side moves southward to the Sichuan–Chongqing region. This wind brings dry cool air from the high latitudes, which converges over the Sichuan–Chongqing region with the warm moist air from the low latitudes. This enhances ascent, which is beneficial for an increase in precipitation.

|

| Figure 8 (a) Correlation between the vertical advection term of <Q1> (atmospheric heat source) over the central TP and the 850-hPa wind field, and (b, c) the composite difference of 850-hPa wind anomaly for years with (b) greater and (c) less precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region. The black area in (a) represents the TP, and the gray shading indicates the greater than 95% confidence level. The TP is represented by the blank area in (b, c). |

Meanwhile, from the composite 850-hPa wind anomaly in the years of greater precipitation (Fig. 8b), it can be seen that the southerly wind anomaly, on the west side of an anticyclonic anomaly over the Indochina Peninsula, advances to the south flank of the TP and then along its southern edge. This causes a counterclockwise flow over the Sichuan–Chongqing region, which converges with the northeasterly wind anomaly from the northwest side of the cyclonic anomaly over the Yellow and Japan seas and adjacent regions, resulting in abundant precipitation. This wind field pattern is similar to that shown in Fig. 8a, which illustrates further that the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP may affect the precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region by affecting the lower tropospheric circulation. At the same time, the wind field anomaly in the years of less precipitation (Fig. 8c) is similar to the wind field pattern that forms under a weakened vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP (i.e., opposite to the wind pattern in Fig. 8a).

The above analysis shows that the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP does affect the precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region by affecting the atmospheric circulation. When the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is strengthened (weakened), the South Asian high shifts further than normal to the south and east (north and west), the western Pacific subtropical high shifts further than normal to the south and west (north and east), the Indian low is weakened (strengthened), and two ridges and one trough (two troughs and one ridge) form in the high latitudes. Thus, the ascending motion is strengthened (weakened) over the Sichuan–Chongqing region, which induces increased (reduced) summer precipitation. At the same time, because of the influence of the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP, the east–west movements of the western Pacific subtropical high and the South Asian high accord in opposite ways with the work of Tao and Zhu (1964).

6 Impact of the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the TP on water vapor transportPrecipitation is not only associated with atmospheric circulation, but also with the transport and flux divergence of water vapor, among many other factors. Therefore, in this section, the influence of the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP on water vapor transport is discussed.

Figure 9a depicts the distribution of the correlation coefficient between the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP and the vertically integrated water vapor transport. When the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is strengthened, there is a significant belt of water vapor transport from the eastern Philippine Sea, across the South China Sea and the Bay of Bengal, to the Arabian Sea, bringing warm moist air from the western Pacific progressively to the further west. Then, the water vapor in the Bay of Bengal and adjacent regions transport northward to the south of the TP, and along the edge of the TP, and move counterclockwisely to the Sichuan–Chongqing region, bringing abundant warm moist air to this region. To the north of 20°N, there is a cyclonic water vapor transport circulation located in the region from eastern China to Japan and adjacent regions. The northeasterly water vapor transport that originates from the northwest side of the circulation can easily reach the Sichuan–Chongqing region and converge with the warm moist air from the low latitudes, resulting in enhanced precipitation. Conversely, when the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is weakened, less water vapor is transported into the Sichuan–Chongqing region, and water vapor divergence and descent motion reduce the precipitation in this region.

|

| Figure 9 (a) Correlation between the vertical advection term of <Q1> (atmospheric heat source) over the central Tibetan Plateau and the vertically integrated moisture transport, and (b, c) the composite difference in the vertically integrated moisture transport anomalies in years with (b) greater and (c) less precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region. The thick dashed line indicates the topography higher than 3000 m. The shading in (a) represents the greater than 95% confidence level. |

By contrasting the composite vertically integrated water vapor transport anomaly of the years of greater and less precipitation, it is clear that the pattern of vertically integrated water vapor transport anomalies in the years of greater precipitation (Fig. 9b) is similar to that in Fig. 9a. There is a significant anomalous anticyclonic circulation of water vapor transport located near the northern Indochina Peninsula, and an anomalous cyclonic circulation of water vapor transport located in the region from eastern China to the vicinity of Japan. This brings warm moist air from the low latitude oceans and dry cool air from high latitudes, which then converge over the Sichuan–Chongqing region and the associated forced ascent induces enhanced precipitation locally. Conversely, the pattern of the vertically integrated water vapor transport anomaly in the years of less precipitation (Fig. 9c) is opposite to that in Fig. 9a. It is difficult for the warm moist air from the low latitudes to reach the Sichuan–Chongqing region, resulting in less precipitation there.

In brief, when the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is strengthened, more water vapor is transported to the Sichuan–Chongqing region, with subsequent convergence and ascent, resulting in augmented precipitation. When this term is weakened, less water vapor is transported to the Sichuan–Chongqing region, and convergence is decreased, which results in less precipitation in this region.

Overall, the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP affects the summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region by affecting the atmospheric circulation over the TP and adjacent regions. When the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is strengthened, the western Pacific subtropical high shifts further than normal to the south and west, such that the easterly wind from the south side of the western Pacific subtropical high helps the westward transport of water vapor from the western Pacific. Near the Bay of Bengal, the northerly wind on the east side of the Indian low can transport water vapor to the southern edge of the TP. With a weakened Indian low and a strengthened counterclockwise circumferential motion along the edge of the TP, additional water vapor is transported eastward to the Sichuan–Chongqing region, bringing abundant warm moist air to this region. At the same time, the circulation pattern of two ridges and one trough in the high latitudes supports the transport of dry cool air southward. This converges with the warm moist air from the low latitudes over the Sichuan–Chongqing region, and the strengthened ascent results in enhanced precipitation. When the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is weakened, the western Pacific subtropical high shifts further than normal to the north and east, the Indian low is strengthened, and the clockwise circumferential motion along the edge of the TP is strengthened. This is unfavorable for the movement of warm moist air from the low latitude oceans to the Sichuan–Chongqing region; thus, weakened ascending motion in this region leads to less precipitation.

7 ConclusionsThis paper investigates the relationship between the <Q1> over the TP and summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region using the methods of synthetic and correlation analysis. The main conclusions are as follows.

(1) The vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is one of the key factors affecting summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region.

(2) When the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is strengthened (weakened), the South Asian high shifts further than normal to the south and east (north and west), the western Pacific subtropical high shifts further than normal to the south and west (north and east), the Indian low is weakened (strength-ened), and two ridges and one trough (two troughs and one ridge) form in the high latitudes, which are beneficial (unfavorable) for airflow from the north and south to converge over the Sichuan–Chongqing region. The re-sulting ascending motion is strengthened (weakened), which induces enhanced (reduced) precipitation.

(3) The vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP exhibits significant influences on the water vapor transport in the Sichuan–Chongqing region in summer. When the vertical advection term of <Q1> over the central TP is strengthened (weakened), abundant (less) water vapor is transported to the Sichuan–Chongqing region, resulting in greater (less) precipitation in this region.

In this study, the influence of the vertical advection of <Q1> over the central TP on the summer precipitation anomaly in the Sichuan–Chongqing region is analyzed statistically; however, further verification is needed through numerical simulation. Although many factors could impact upon the summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region, this paper focuses on the vertical advection of <Q1> over the central TP. Other factors, such as the plateau monsoon and the westerly circulation, also influence the summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region to some extent, so the variations of the vertical advection of <Q1> over the central TP and the summer precipitation in the Sichuan–Chongqing region are not in-phase in certain years. Thus, the interaction between different factors should be emphasized in further studies.

| Bai B. R., Hu Z. Y., 2016: Indicative significance of thermal effects over the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau to the onset of plateau summer monsoon. Plateau Meteor., 35, 329–336. |

| Cen S. X., Gong Y. F., Lai X., 2014a: Impact of heat source over Qinghai–Xizang Plateau and its surrounding areas on rainfall in Sichuan–Chongqing basin in summer. Plateau Meteor., 33, 1182–1189. |

| Cen S. X., Gong Y. F., Lai X., et al.,2014b: The relationship of the thermal contrast between the eastern Tibetan Plateau and its northern side with the plateau monsoon and the precipitation in the Yangtze River basin in summer. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 72, 256–265. |

| Chen Q. L., Ni C. J., Wan W. L., 2010: Features of summer precipitation change of the Chuanyu basin and its relationship with large-scale circulation. Plateau Meteor., 29, 587–594. |

| Chen W. X., Hao K. J., 2001: Analysis on the character of rainfall changing over Sichuan basin in the 20th century. Journal of Sichuan Meteorology, 21, 37–39. |

| Duan A. M., Wu G. X., 2008: Weakening trend in the atmospheric heat source over the Tibetan Plateau during recent decades. Part I: Observations. J. Climate, 21, 3149–3164. DOI:10.1175/2007JCLI1912.1 |

| Duan A. M., Li F., Wang M. R., et al.,2011: Persistent weakening trend in the spring sensible heat source over the Tibetan Plateau and its impact on the Asian summer monsoon. J. Climate, 24, 5671–5682. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00052.1 |

| Duan A. M., Wu G. X., Liu Y. M., et al.,2012a: Weather and climate effects of the Tibetan Plateau. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 29, 978–992. DOI:10.1007/s00376-012-1220-y |

| Duan A. M., Wang M. R., Lei Y. H., et al.,2012b: Trends in summer rainfall over China associated with the Tibetan Plateau sensible heat source during 1980–2008. J. Climate, 26, 261–275. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00669.1 |

| Flohn H., 1957: Large-scale aspects of the summer monsoon in South and East Asia. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan, 75, 180–186. |

| Flohn, H., 1960: Recent investigations on the mechanism of the " summer monsoon” of southern and eastern Asia. Symposium on Monsoons of the World, Hindu Union Press, 75–88. |

| Jian M. Q., Luo H. B., Qiao Y. T., 2004: On the relationships between the summer rainfall in China and the atmospheric heat sources over the eastern Tibetan Plateau and the western Pacific warm pool. J. Trop. Meteor., 10, 133–143. |

| Jian M. Q., Qiao Y. T., Yuan Z. J., et al.,2006: The impact of atmospheric heat sources over the eastern Tibetan Plateau and the tropical western Pacific on the summer rainfall over the Yangtze River basin. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 23, 149–155. DOI:10.1007/s00376-006-0015-4 |

| Jiang X. W., Li Y. Q., Li C., et al.,2007: Characteristics of summer water vapor transportation in Sichuan basin and its relationship with regional drought and flood. Plateau Meteor., 26, 476–484. |

| Jiang X. W., Li Y. Q., Yang S., et al.,2016: Interannual variation of summer atmospheric heat source over the Tibetan Plateau and the role of convection around the western Maritime continent. J. Climate, 29, 121–138. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-15-0181.1 |

| Li C., Rui J. X., 1997: Relationship between the rainfall pattern in Sichuan basin in flood season with the rain bands in China. Journal of Sichuan Meteorology, 17, 2–5. |

| Li Y. Q., 2000: Analysis of circulation variations over the Tibetan Plateau and drought–flood anomalies on its eastern side. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 24, 470–476. |

| Liao G. M., Yan J. P., Hu N. N., et al.,2012: Analysis on temporal series of precipitation and drought–flood about the recent 50 years in the east of Sichuan basin. Resources and Environment in the Yangtze Basin, 21, 1160–1166. |

| Liu X., Li W. P., Wu G. X., 2002: Interannual variation of the diabatic heating over the Tibetan Platean and the Northern Hemispheric circulation in summer. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 60, 267–277. |

| Luo S. W., Qian Z. A., Wang Q. Q., 1982: The climatic and synoptical study about the relation between the Qinghai–Xizang high pressure on the 100-mb surface and the flood and drought in East China in summer. Plateau Meteor., 1, 1–10. |

| Ma Z. F., Gao W. L., Liu F. M., et al.,2003: A study on monsoon circulations of drought and wet years on the east side of Qinghai–Xizang Plateau in early summer. Plateau Meteor., 22, 1–7. |

| Mao W. S., Zhu K. Y., Huang K. W., et al.,2010: Characteristics of water vapor transport of summer precipitation anomalies in Sichuan–Chongqing region. Journal of Natural Resources, 25, 280–290. |

| Qi D. M., Li Y. Q., Chen Y. R., et al.,2011: Spatial–temporal variations of drought and flood intensities in Sichuan region in the last 50 years. Plateau Meteor., 30, 1170–1179. |

| Tan Y. B., Ma Z. F., 1997: Study of the characteristics of precipitation change in Sichuan for June–August and the predicting factor. Journal of Sichuan Meteorology, 17, 6–10. |

| Tao S. Y., Zhu F. K., 1964: The 100-mb flow patterns in southern Asia in summer and its relation to the advance and retreat of the western Pacific subtropical anticyclone over the far east. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 34, 385–396. |

| Wang Z. Q., Duan A. M., Wu G. X., 2014: Time-lagged impact of spring sensible heat over the Tibetan Plateau on the summer rainfall anomaly in East China: Case studies using the WRF model. Climate Dyn., 42, 2885–2898. DOI:10.1007/s00382-013-1800-2 |

| Wei N., Gong Y. F., He J. H., 2009: Structural variation of an atmospheric heat source over the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau and its influence on precipitation in Northwest China. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 26, 1027–1041. DOI:10.1007/s00376-009-7207-7 |

| Yanai M., Esbensen S., Chu J. H., 1973: Determination of bulk properties of tropical cloud clusters from large-scale heat and moisture budgets. J. Atmos. Sci., 30, 611–627. DOI:10.1175/1520-0469(1973)030<0611:DOBPOT>2.0.CO;2 |

| Yang H., 2001: Anomalous atmospheric circulation, heat sources, and moisture sinks in relation to great precipitation anomalies in the Yangtze River valley. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 18, 972–983. |

| Ye, D. Z., and Y. X. Gao, 1979: The Meteorology of the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau. Science Press, Beijing, 278 pp. (in Chinese) |

| Zhao P., Chen L. X., 2001a: Climatic features of atmospheric heat source/sink over the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau in 35 years and its relation to rainfall in China. Sci. China (Series D), 44, 858–864. DOI:10.1007/BF02907098 |

| Zhao P., Chen L. X., 2001b: Interannual variability of atmospheric heat source/sink over the Qinghai–Xizang (Tibetan) Plateau and its relation to circulation. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 18, 106–116. DOI:10.1007/s00376-001-0007-3 |

| Zhao S. R., Song Z. S., Ji L. R., 2003: Heating effect of the Tibetan Plateau on rainfall anomalies over North China during rainy season. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 27, 881–893. |

| Zhou C. Y., Li Y. Q., Fang J., et al.,2008: Features of the summer precipitation in the west and east of Sichuan and Chongqing basin and on the eastern side of the plateau and the relating general circulation. Plateau and Mountain Meteorology Research, 28, 1–9. |

| Zhou C. Y., Li Y. Q., Bu Q. L., et al.,2011: Features of drought–flood coexistence in west and east of Sichuan–Chongqing basin in midsummer and its relating background of atmospheric circulation. Plateau Meteor., 30, 620–627. |

| Zhou X. J., Zhao P., Chen J. M., et al.,2009: Impacts of thermodynamic processes over the Tibetan Plateau on the Northern Hemispheric climate. Sci. China (Series D), 52, 1679–1693. DOI:10.1007/s11430-009-0194-9 |

2017, Vol. 31

2017, Vol. 31