The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- Maoyuan LOU, Chao LI, Shifeng HAO, Juan LIU. 2017.

- Variations of Winter Precipitation over Southeastern China in Association with the North Atlantic Oscillation. 2017.

- J. Meteor. Res., 31(3): 476-489

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-017-6103-9

Article History

- Received June 7, 2016

- in final form October 19, 2016

2. Zhejiang Institute of Meteorological Sciences, Hangzhou 310008;

3. Zhejiang Meteorological Service Center, Hangzhou 310017

As winter monsoon prevails, cold-season rainfall in China exhibits considerable variability. Winter precipitation is important for air pollution removal, drought amelioration, and transportation management. On account of deteriorating air quality, winter haze has become increasingly severe over China in recent years (Chen and Wang, 2015; Wang et al., 2015). Heavy precipitation is helpful for cleaning of dirty air and removal of haze. Winter precipitation can also increase soil moisture, which is good for crop growth in the succeeding spring. Continuous heavy precipitation sometimes comes along with cold air intrusions (Wen et al., 2009), which can result in severe snowstorms and lead to transportation disruption. For example, a prolonged period of freezing rain and snowstorms struck southeastern China in January 2008, bringing huge economic losses (Wen et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2009). Thus, improving understanding of winter precipitation variations and associated physical mechanisms over China, especially for persistent events, is of great scientific and economic value.

A number of studies have investigated the climatic features of the East Asian winter monsoon (EAWM) (Compo et al., 1999; Huang et al., 2003; Jhun and Lee, 2004), but most of them are from the perspective of surface air temperature (e.g., Li and Zhang, 2013). Following the severe snowstorms in January 2008, increasing attention has been paid to wintertime precipitation variability in China. China’s winter precipitation occurs mainly over the area south of the Yellow River, with pronounced interannual variability (Wang and Feng, 2011; Liu et al., 2012). Using seasonal mean data and empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis, Wang and Feng (2011) obtained two major modes of winter precipitation anomalies in China. The precipitation anomaly in southeastern China shows a monopole pattern, with its maximum center over South China in the first leading EOF mode (EOF1), and a dipole pattern in EOF2 (Wang and Feng, 2011). The overall precipitation in southeastern China is negatively correlated with the intensity of the EAWM (Zhou, 2011). Southerly wind anomalies dominate over the east flank of East Asia during weak EAWM years, which induces more rain over southeastern China (Zhou, 2011). Although the southerly wind anomaly could alter the transport of moisture for winter precipitation over southeastern China, it is less useful when it comes to explaining the dipole precipitation anomaly pattern over this region.

Persistent precipitation is always characterized by large-scale features, referred to in this study as the “precipitation regime.” As teleconnections represent persistent or recurring circulation patterns (Dole, 1986; Barnston and Livezey, 1987), the precipitation regime over China has also been investigated with regard to teleconnections in the middle and high latitudes (Wen et al., 2009; Li and Sun, 2015). The Arctic Oscillation (AO) and North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) are two of the most important teleconnections in the middle and high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere (Ambaum et al., 2001). During positive AO phases, the EAWM tends to be weaker (Wu and Wang, 2002), which may cause more rainfall over eastern China (Zhou and Wu, 2010). A more recent study (Chen et al., 2014) showed that EAWM variability has northern and southern components, and only the northern component is associated with changes in the mid- to high-latitude circulation systems. The NAO shares some common features with the AO but has a clearly different physical meaning (Ambaum et al., 2001), and is associated with the atmospheric patterns over the Euro–Atlantic sector (Hurrell, 1995; Wettstein and Mearns, 2002). Recent studies have reported regime transitions of the NAO (e.g., Cassou, 2008; Luo et al., 2012) associated with persistent low temperature and precipitation in the northeastern United States, Europe, and even Northwest China (Archambault et al., 2010; Luo et al., 2014; Li and Zhang, 2015). Watanabe (2004) argued the NAO signal might extend towards East Asia and North Pacific along the Asian jet waveguide during the decaying stage of the NAO in late winter (e.g., February).

The above-mentioned studies are mostly based on monthly mean data (e.g., Wang and Feng, 2011; Zhou, 2011). In fact, monthly atmospheric circulation is always characterized by quasi-stationary patterns. Thus, the synoptic features of winter precipitation cannot be fully identified by monthly mean data. Through a case study, Li and Sun (2015) argued that the heavy precipitation over southeastern China during 13–17 December 2013 was related to a negative-to-positive phase transition of NAO. However, the relationship between NAO transition and precipitation over China remains ambiguous. More stringent composite and diagnostic analyses have shown that a downstream extension of the NAO occurs in the decaying stage of NAO events, but is not obvious in its developing stage (e.g., Watanabe, 2004).

The aim of the present paper is to investigate the synoptic-scale variation/regime-shifting features of wintertime precipitation over southeastern China and their association with the atmospheric teleconnection pattern NAO. Section 2 describes the data and methods used. The precipitation regimes over southeastern China are identified and presented in Section 3. In Section 4, we investigate the circulation features of the precipitation regimes from a synoptic viewpoint. Section 5 examines the teleconnection patterns of NAO in the middle and high latitudes that drive the precipitation regimes. Section 6 concludes the study.

2 Data and methodsThis study uses daily precipitation data on a 0.5° × 0.5° latitude–longitude grid for 1951–2007, provided by the Asian Precipitation–Highly-Resolved Observational Data Integration Towards the Evaluation of Water Resources (APHRODITE) project (Yatagai et al., 2012). This gridded precipitation dataset utilizes a large number of observations and has good representation over China (Han and Zhou, 2012). Another daily gridded precipitation dataset, from Xie et al. (2007, hereafter XIE07), is also used, for a case study. The daily mean atmospheric reanalysis data, on a 2.5° × 2.5° latitude–longitude grid, are from the NCEP–NCAR reanalysis (Kalnay et al., 1996). Variables analyzed include geopotential height, surface air temperature, and zonal and meridional winds. The daily NAO index is from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)/Climate Prediction Center (CPC; http://www.cpc.noaa.gov/).

In this study, “winter” refers to December–January–February. For the daily average fields, the climatology is defined by a 57-yr mean value for each calendar day of winter, and then the daily anomaly is defined as the deviation from the 7-day smoothed daily climatology. A k-means cluster analysis is applied to the daily precipitation anomaly to study the spatial and temporal features of winter precipitation variations over southeastern China, following the procedures used by Cassou (2008).

The wave activity flux formulated by Takaya and Nakamura (2001) is used to study the propagation features of Rossby waves. The formulation of the wave activity flux is

| $\!\!W =\! \frac{1}{{2\left| {\,\bar{U\,\,}} \right|}}\left\{ \begin{array}{l}\!\!\!\bar u(\varphi '{_x}^2 - \varphi '{\varphi _{xx}}') + \bar v({\varphi _x}'{\varphi _y}' - \varphi '{\varphi _{xy}}'),\,\\\!\!\!\bar u({\varphi _x}'{\varphi _y}' - \varphi '{\varphi _{xy}}') + \bar v(\varphi '{_y}^2 - \varphi '{\varphi _{yy}}'),\,\end{array} \right.$ | (1) |

where u and v are the zonal and meridional wind components, and

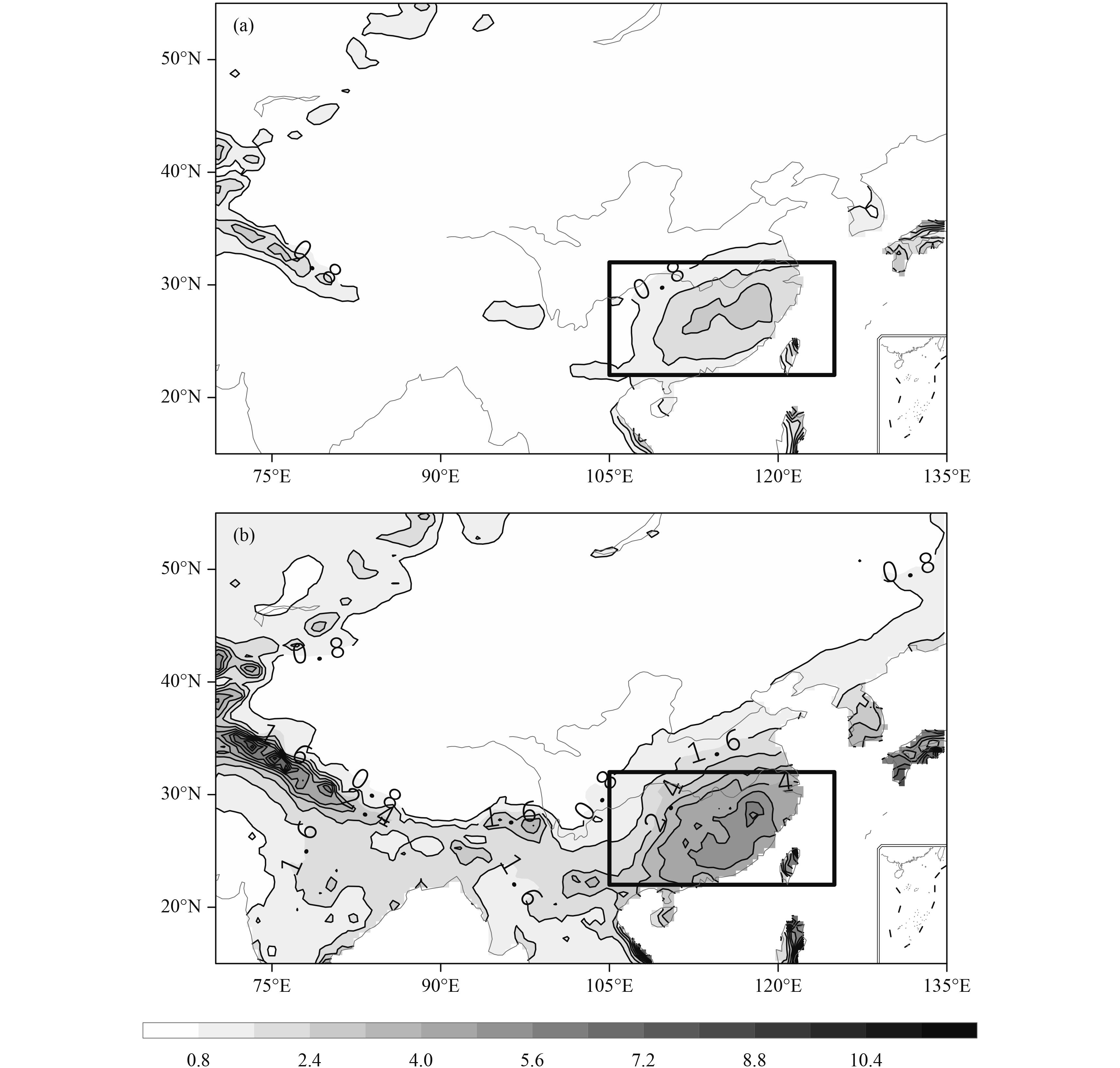

This part of the study uses cluster analysis to examine the spatial and temporal features of wintertime precipitation variations in southeastern China. It is important to first examine the climatology of wintertime daily rainfall in China (Fig. 1a) as the basis for precipitation regime analysis. Winter precipitation occurs mainly over southeastern China (including central eastern China and South China). The maximum value of precipitation reaches 2.8 mm over the Yangtze River basin (around 28°N), which is close to the climatological center value derived from seasonal mean data (Wang and Feng, 2011; Li and Ma, 2012). Despite similar spatial distributions of the precipitation climatology, the distribution of standard deviation of daily precipitation is quite different from that of the seasonal mean. For the latter, the maximum is found over South China where the interannual variation is more prominent (Li and Ma, 2012). In comparison, the maximum center of standard deviation derived from the daily precipitation data is found over the Yangtze River basin (Fig. 1b), which is quite close to the climatological center. The differences between such standard deviation distributions suggest that the synoptic-scale variation of winter precipitation is more prominent over the Yangtze River basin.

|

| Figure 1 The (a) climatology and (b) standard deviation of wintertime (December–January–February) daily rainfall (shaded; mm) based on the APHRODITE (Asian Precipitation–Highly-Resolved Observational Data Integration Toward Evaluation of Water Resources) data for the period 1951–2007. Contour intervals are 0.8 mm. The rectangular box represents southeastern China (22°–32°N, 105°–125°E). |

Given the climatology of winter precipitation, the region for southeastern China is selected as 22°–32°N, 105°–125°E (rectangular box in Fig. 1). The daily precipitation anomalies are weighted by the cosine of latitude to avoid the latitudinal effect. This latitudinal weighting was also used by Cassou (2008). A k-means cluster analysis is performed on the weighted daily precipitation anomalies over the selected domain. We choose k = 3 as the optimal number for the regime analysis, based on Brownian noise statistics (Michelangeli et al., 1995). We also increase k slightly (e.g., k = 4) and find that the first three regimes are robust.

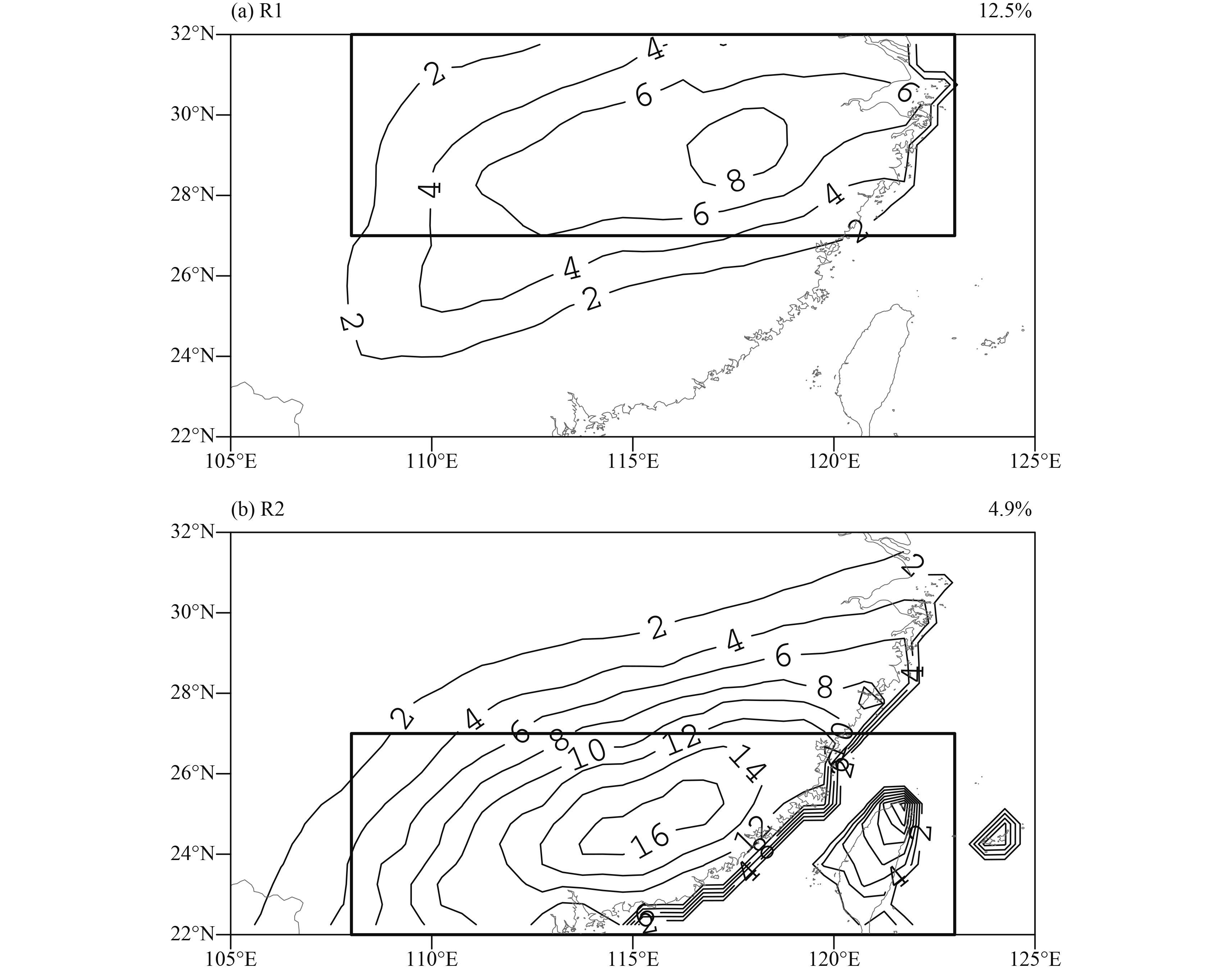

The first regime (R0) displays no obvious precipitation anomalies over southeastern China against the winter climatology, and accounts for 82.6% of wintertime days (figure omitted). We calculate the area average of daily rainfall over southeastern China for the days that are recognized as R0. Low rainfall dominates southeastern China on R0 days; area-averaged daily rainfall of less than 1 mm day–1 accounts for 67.6% of R0 days. As the main concern of this study is wintertime precipitation variation, we discard this regime in the following analyses. For the second regime (R1), a precipitation anomaly center with a maximum value of about 8 mm is found over the Yangtze River basin (around 30°N), which is quite close to the climatology and standard deviation center (Fig. 1). The third regime (R2) happens less than half as often as R1, with a maximum center of about 16 mm over the Pearl River basin (around 25°N). We also apply EOF analysis to the daily precipitation and obtain similar patterns (figure omitted). Thus, the derived cluster patterns are reasonable for the following synoptic analysis of precipitation regimes over southeastern China.

In view of the cluster patterns (Fig. 2), central eastern China is defined as the region (27°–32°N, 108°–123°E) (rectangular box in Fig. 2a) and South China is defined as (22°–27°N, 108°–123°E) (box in Fig. 2b). These definitions are used throughout the following analyses.

|

| Figure 2 Spatial modes (contour; %) of wintertime precipitation regimes in southeastern China obtained via k-means cluster analysis for 1951–2007: (a) Regime 1 (R1); (b) Regime 2 (R2). Contour intervals are 2 mm. Each percentage represents the occurrence frequency of the regime. The rectangular boxes represent central eastern China (27°–32°N, 108°–123°E) in (a), and South China (22°–27°N, 108°–123°E) in (b). |

Persistent wintertime precipitation is our main concern in this study. Based on the cluster analysis results, a major R1 event (R1 event hereafter) is defined when at least 4 consecutive days are recognized as R1, while a major R2 event (R2 event hereafter) is determined when at least 3 consecutive days appear as R2. Different thresholds for the two major regime events are selected for adequate cases. Table 1 provides information on the 18 R1 and 9 R2 events that are selected. The average duration is 4.8 days for R1 events, which is longer than that for R2 events (about 3.7 days).

| No. | Major R1 event onset date | Major R1 event end date | Duration | Major R2 event onset date | Major R2 event end date | Duration |

| 1 | 23 Feb 1951 | 27 Feb 1951 | 5 | 15 Feb 1952 | 17 Feb 1952 | 3 |

| 2 | 12 Feb 1959 | 17 Feb 1959 | 6 | 2 Dec 1953 | 6 Dec 1953 | 5 |

| 3 | 2 Feb 1972 | 7 Feb 1972 | 6 | 18 Feb 1959 | 23 Feb 1959 | 6 |

| 4 | 25 Feb 1973 | 28 Feb 1973 | 4 | 21 Jan 1964 | 23 Jan 1964 | 3 |

| 5 | 2 Feb 1975 | 7 Feb 1975 | 6 | 22 Feb 1990 | 24 Feb 1990 | 3 |

| 6 | 4 Dec 1975 | 8 Dec 1975 | 5 | 3 Jan 1992 | 5 Jan 1992 | 3 |

| 7 | 13 Dec 1984 | 18 Dec 1984 | 6 | 9 Feb 1992 | 11 Feb 1992 | 3 |

| 8 | 24 Feb 1988 | 29 Feb 1988 | 6 | 17 Feb 1994 | 19 Feb 1994 | 3 |

| 9 | 24 Dec 1991 | 27 Dec 1991 | 4 | 16 Feb 1998 | 19 Feb 1998 | 4 |

| 10 | 3 Jan 1993 | 6 Jan 1993 | 4 | |||

| 11 | 18 Feb 1993 | 21 Feb 1993 | 4 | |||

| 12 | 7 Jan 1998 | 10 Jan 1998 | 4 | |||

| 13 | 9 Dec 2001 | 12 Dec 2001 | 4 | |||

| 14 | 15 Jan 2002 | 18 Jan 2002 | 4 | |||

| 15 | 13 Feb 2003 | 16 Feb 2003 | 4 | |||

| 16 | 22 Dec 2004 | 28 Dec 2004 | 7 | |||

| 17 | 7 Feb 2005 | 10 Feb 2005 | 4 | |||

| 18 | 17 Jan 2006 | 20 Jan 2006 | 4 |

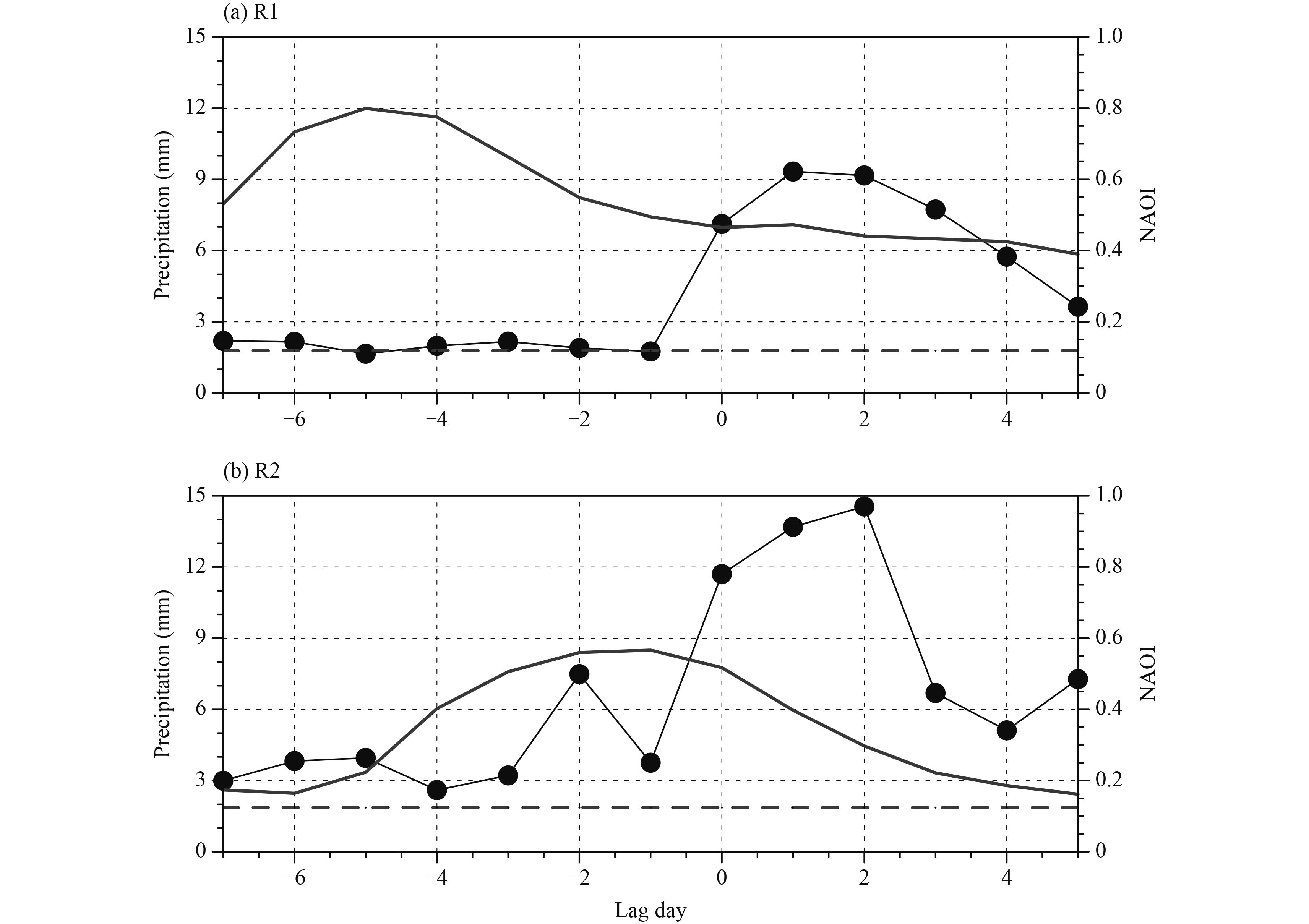

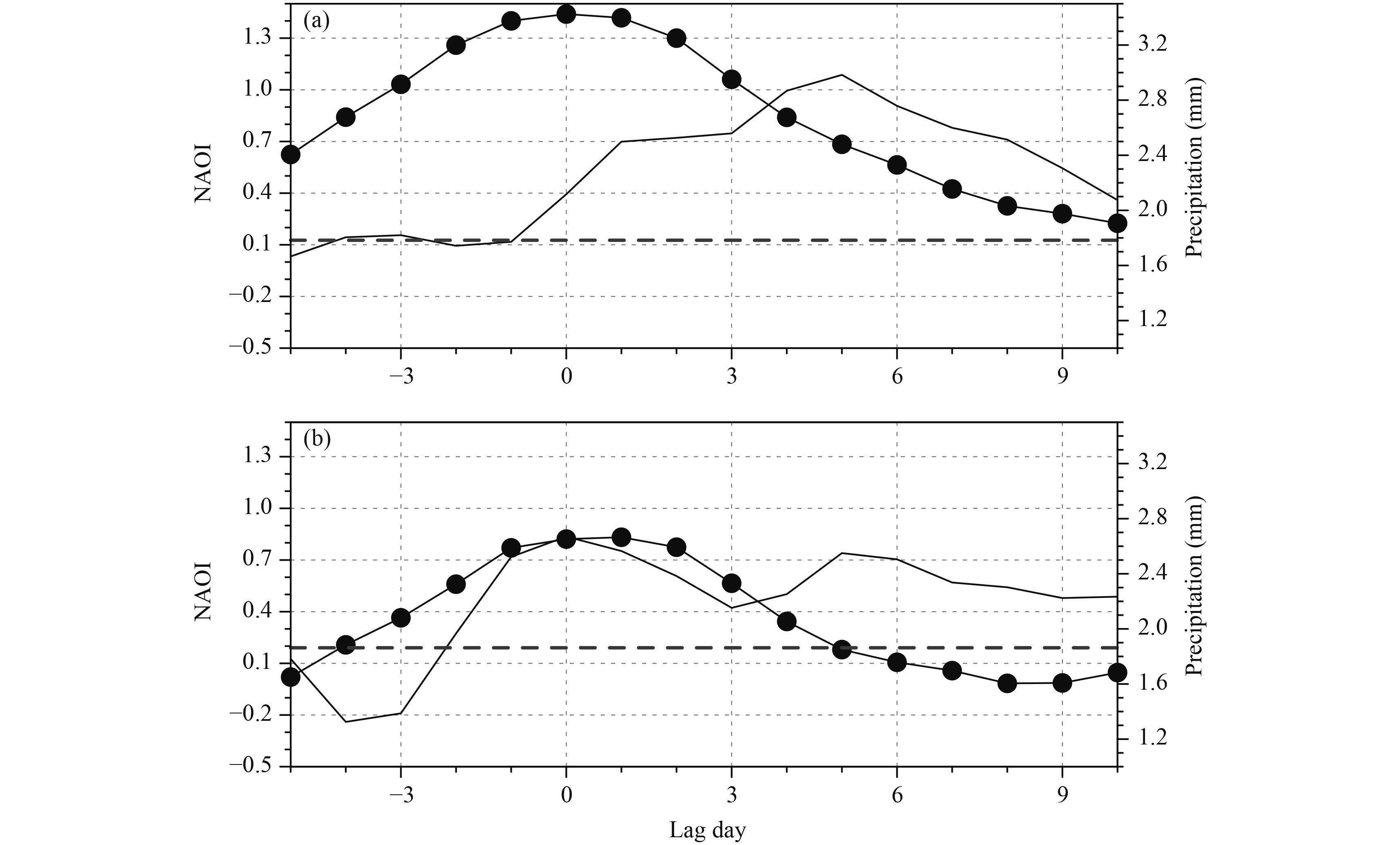

Figure 3 displays time series of area-averaged precipitation and the NAO index for R1 and R2 regime events. Here, day(0) is defined as the onset date of each major precipitation regime event. Both types of regime events occur during the decaying period of the positive NAO (NAO+). Precipitation increases to about 8–10 mm over central eastern China during the evolution of R1 events, which lags the peak index of NAO by about 5–6 days. About 5 days prior to the onset date of a major R1 event, the NAO index reaches a peak value of about 0.8, which is recognized here as a strong NAO+ event. In contrast, the R2 events occur during the decaying phase of medium NAO+, with a peak index of about 0.6. Compared with the R1 events, precipitation is markedly enhanced to 12–15 mm over South China on day(2), which lags the peak index of the NAO by about 4 days. There is another smaller peak of about 7 mm on day(–2) of the R2 events. Precipitation is indeed much greater over South China during the evolution of the R2 events, which is in agreement with the greater amplitude of R2 in the cluster analysis results (Fig. 2).

|

| Figure 3 Temporal evolution of the area-averaged precipitation (thin lines with dots; mm) and the rainfall climatology (thick dashed lines; mm) calculated over all wintertime calendar days in (a) central eastern China for the major Regime 1 (R1) events and (b) South China for the major Regime 2 (R2) events. The thick solid lines without dots in (a) and (b) represent the composite NAO (North Atlantic Oscillation) index (NAOI) for the two major regime events. Day(0) is defined as the onset date of a major regime event. |

Persistent precipitation is always characterized by large-scale features and coherence with synoptic-scale systems (Leathers et al., 1991). A lead–lag composite analysis of circulation is conducted for the synoptic features of the major precipitation regime events in this section.

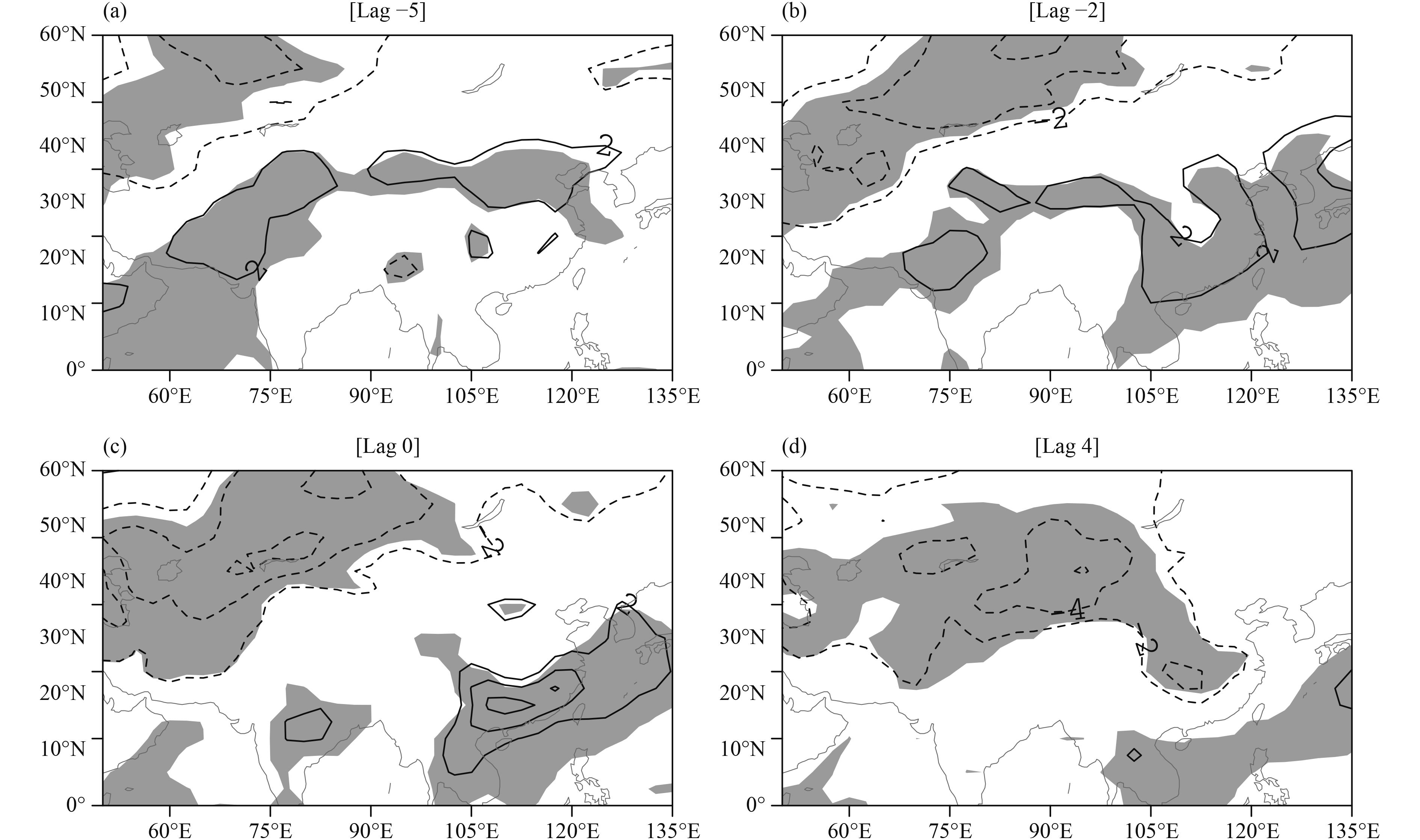

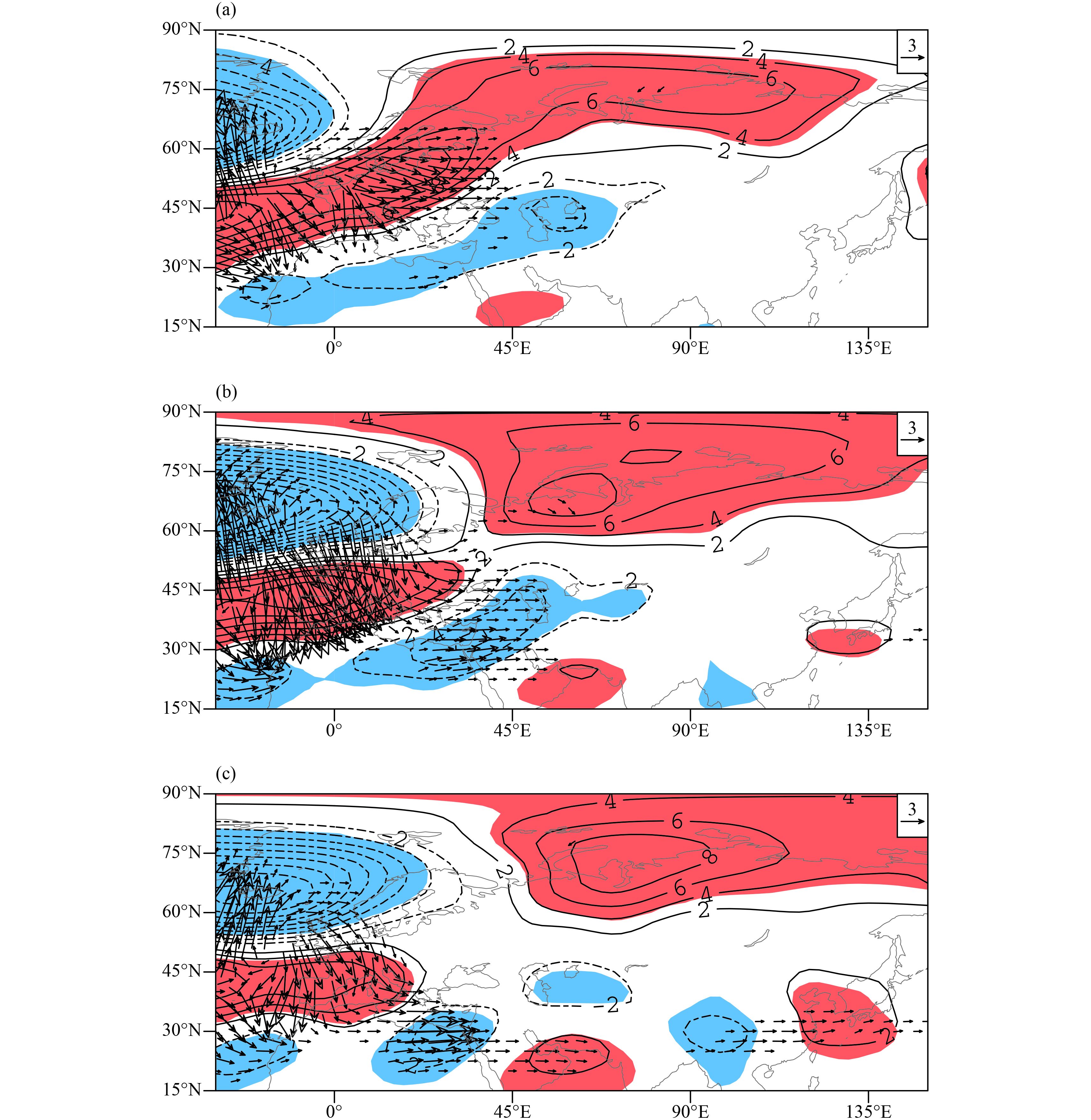

Figure 4 displays composites of the 300-hPa geopotential height field and their anomalies, and 850-hPa wind, for R1 events. On day(–5), a low–high dipole of 300-hPa geopotential height anomalies is clear over the Euro–Atlantic sector, which shows an NAO+ like pattern. The NAO+ like dipole is also manifested in the NAO index composites (Fig. 3a). Downstream of the NAO+ like pattern, there is a northeast–southwest-tilted band of negative anomalies extending from Lake Baikal to the eastern Mediterranean. In the following days, the NAO+ like dipole weakens over the Atlantic sector, with noticeable attenuation of the Icelandic low and eastward migration of the Azores high to eastern Europe (around 45°E). The tilted negative anomaly strengthens and migrates slowly eastward along 45°N with time. Superposed on the absolute geopotential height (thin contours in Figs. 4a1–a4), the tilted negative anomaly represents an enhanced trough over Lake Baikal. On day(0), the northeast–southwest-tilted trough migrates further to the east of Lake Baikal. Northerly winds at 850 hPa are obvious behind the tilted trough, and bring cold air southward (Figs. 4b3, 5c ). On the other hand, downstream propagation of a wave-train-like anomaly exists from the eastern Mediterranean to the western Pacific along the Asian jet stream. A high anomaly shows up over the eastern coast of East Asia (around 135°E), which represents a strengthened subtropical anticyclone over the western Pacific (Wen et al., 2009; Zhou et al., 2009). In agreement with the strengthened subtropical anticyclone, southerly winds enhance significantly at 850 hPa and transport moist air northeastward. The southerly winds are strongest on day(0), which corresponds to significant warming over southeastern China (Fig. 5c). Precipitation is obvious as cold air and warm air converge during the ensuing days. On day(4), the tilted trough over the east of Lake Baikal migrates further eastward. Consequently, cold air dominates over eastern China (Fig. 5d) and precipitation tends to weaken (Fig. 3a).

|

| Figure 4 Temporal evolution of composite (a1–a4) 300-hPa geopotential height (thin contours, every 8 dam) and departures from the climatology (thick contours, every 4 dam), and (b1–b4) 850-hPa wind (m s−1; plotted where speeds exceed 5 m s−1) on (a1, b1) day(–5), (a2, b2) day(–2), (a3, b3) day(0), and (a4, b4) day(4) for the major Regime 1 (R1) events. Shading denotes statistical significance at the 95% confidence level for 300-hPa geopotential height anomalies in (a), and for 850-hPa meridional winds in (b). |

|

| Figure 5 Temporal evolution of composite daily surface air temperature anomalies (contours; K) on (a) day(–5), (b) day(–2), (c) day(0), and (d) day(4) for the major Regime 1 (R1) events. Contour intervals are 2 K and shading denotes statistical significance at the 95% confidence level against the wintertime climatology. |

The circulation composites for R2 are displayed in Fig. 6. On day(–2), a classical NAO+ like dipole is also observed over North Atlantic. A more cramped anticyclone anomaly is dominant over the western Pacific. Consistent with the cramped anticyclone anomaly (Fig. 6a2), southeasterly winds at 850 hPa are dominant over South China (Fig. 6b2). Precipitation is enhanced in the warm area and accounts for the small peak of precipitation on day(–2) (Fig. 3b). In the following days, the NAO+ like dipole exhibits distinct eastward migration. A wave-train-like anomaly chain along 30°N is also obvious during the positive lag days of R2. Precipitation is enhanced again during eastward propagation of the anomalous low over South China. Compared with R1, enhanced southerly winds are limited over South China at 850 hPa during the evolution of R2. This difference in 850-hPa winds may contribute to the meridional displacement of precipitation between the two precipitation regimes.

|

| Figure 6 As in Fig. 4, but for the major Regime 2 (R2) events. |

Section 4 revealed the decaying features of the NAO during the evolution of the two precipitation regimes. The NAO is one of the most prominent persistent large-scale flow patterns, and our ability to forecast it is high—by as much as two weeks in advance (Johansson, 2007). As such, a question arises as to whether the two precipitation regimes always occur in the decaying periods of the NAO. If this were the case, it would be valuable for medium-range forecasts of wintertime large-scale precipitation over southeastern China. The precipitation features during the evolution of the NAO are discussed in this section.

5.1 Statistical resultsTo clarify the precipitation features during the evolution of the NAO, different amplitudes of NAO+ events are objectively identified based on the daily NAO index. A strong NAO+ event is defined as when the daily NAO is greater than 1.0 and persists for at least 4 consecutive days; whereas, if the peak amplitude falls within the range of 0.6–1.0 and lasts at least 4 days, it is classed as a medium NAO+ event. Following Archambault et al. (2010) and Luo et al. (2014), only those NAO+ events whose NAO index is reduced to less than 0.3 within 7 days after the peak are retained. The 7-day window used in this filtering procedure is based on the two-week timescale of NAO events (Feldstein, 2003). Ultimately, we identify 26 (11) strong (medium) NAO+ events.

Figure 7 displays the time series of composite NAO index and area-averaged precipitation for the selected NAO events. Day(0) is defined as the occurrence date of the peak NAO index value for each chosen NAO+ event. For a strong NAO+ event, the NAO index reaches a peak of above 1.3 on day(0), and reduces to about 0.4 on day(5). During the decaying period of strong NAO+ events, the area-averaged precipitation is obviously enhanced over central eastern China. The NAO index leads the area-averaged precipitation over central eastern China by about 4 days, which is slightly shorter than the analysis of R1 in Section 3. For a medium NAO+ event, the NAO index reaches about 0.8 on day(0), and reduces to less than 0 on day(5). During the evolution of a medium NAO+ event, the area-averaged precipitation over South China reaches two local maxima above 2.4 mm on day(0) and day(5). These two maxima of area-averaged precipitation over South China are consistent with the analysis of R2 in Section 3.

|

| Figure 7 Time series of composite NAO index (NAOI; lines with dots) for (a) strong NAO events and (b) medium NAO events. Day(0) is defined as the occurrence date of the maximum amplitude of the NAO index for strong NAO events in (a), and for medium NAO events in (b). The solid line without dots denotes the area-averaged precipitation over central eastern China in (a), and over South China in (b). The thick dashed lines indicate the regional-averaged precipitation climatology calculated over all wintertime calendar days. |

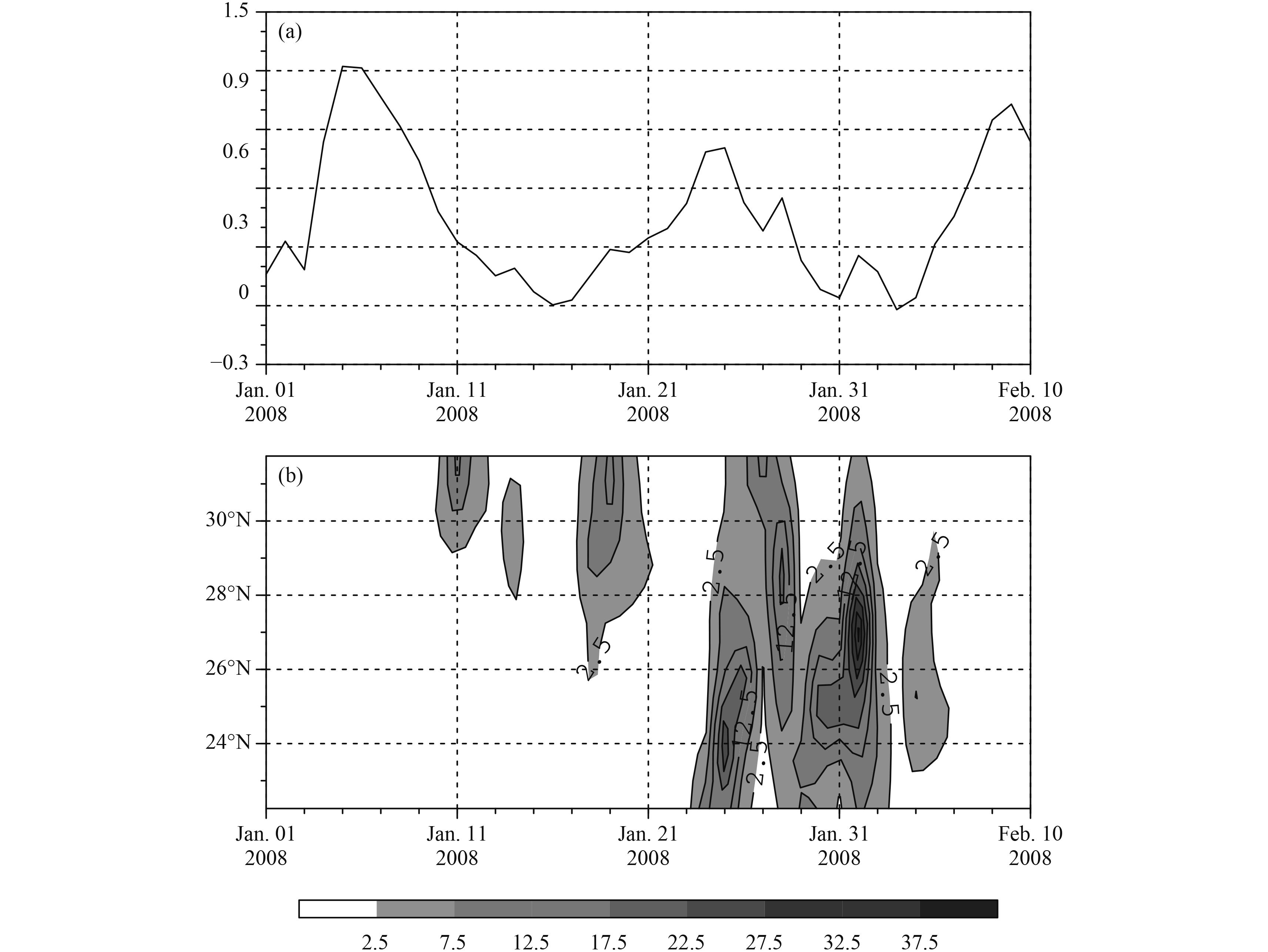

As mentioned in the introduction, severe snowstorms hit southeastern China in January 2008. The snowstorms occurred in four major periods, and were associated with the activities of the Ural blocking and the East Asian jet stream (Wen et al., 2009). Here, we examine the snowstorms from the perspective of the NAO using the XIE07 precipitation dataset (Fig. 8). There are two decays of NAO+ in January 2008. The first took place during the first half of January, with a peak index value of about 1.2 on 5 January. This can be recognized as a strong NAO+ decaying event. About 5 days after this peak, precipitation enhanced along 30°N in the first two consecutive periods and was coherent with the spatial pattern of R1. The second decay of NAO+ happened during the second half of January, with a maximum index value of about 0.8 on 26 January. This can be considered as a medium NAO+ decaying event. The third period of precipitation occurred at the peak of the medium NAO+ event. The fourth period of precipitation occurred at the end of the medium NAO+ event and lagged the peak NAO index by about five days. The third and fourth periods of precipitation happened mainly over South China (24°–28°N) during the second decay of NAO+ and coincided with the spatial pattern of R2. The much larger amount of precipitation during the second half of January was coherent with the greater amplitude of R2 in the cluster analysis (Fig. 2b). The severe snowstorm in January 2008 is not an exceptional case; it can be considered as an example of the association between different amplitudes of NAO+ in decaying periods and precipitation over southeastern China.

|

| Figure 8 (a) Temporal evolution of the daily NAO index and (b) time–latitude cross-section of precipitation (mm) averaged between 108° and 123°E, during 1 January–10 February 2008. |

A possible mechanism responsible for the association between the synoptic evolution of the NAO and the precipitation regimes over southeastern China is elucidated. Figure 9 displays the composite 300-hPa geopotential height anomalies and corresponding Rossby wave activity fluxes for the synoptic evolution of strong NAO+ events. An NAO+ dipole is evident over North Atlantic, and an anomalous high is dominant over western Siberia, which is coherent with the prototype of the NAO (Barnston and Livezey, 1987). The anomalous high over western Siberia exhibits quasi-stationary features during the lag period. Northerly wind and cold air prevail along the eastern flank of the Siberian high. Precipitation would then strengthen with the cold air intrusion. In the mid–low latitudes, three anomalous lows appear over North Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the Bay of Bengal. During the decaying phase of NAO+, a wave-train-like anomaly chain enhances along the Asian jet waveguide (around 30°N) with the downstream propagation of a Rossby wave (Hoskins and Ambrizzi, 1993; Watanabe, 2004). At the rear of the anomaly chain, an anomalous high becomes enhanced over western Pacific and represents the enhanced subtropical anticyclone (Figs. 9b, c). In agreement with the enhanced subtropical anticyclone, southerly winds intensify significantly at 850 hPa (Fig. 10a). Precipitation tends to enhance with the low latitude migration of anomalies. The downstream migration of precipitation along 30°N for R1 (figure omitted) suggests a major role played by the wave-train-like anomaly in the mid–low latitudes.

|

| Figure 9 Temporal evolution of composite 300-hPa geopotential height anomalies (contours, every 2 dam) and corresponding Rossby wave activity fluxes (vectors; m2 s–2) on (a) day(0), (b) day(3), and (c) day(5) for strong NAO events. Shading denotes statistical significance at the 95% confidence level for the 300-hPa geopotential height anomalies. |

To interpret the result in Fig. 9, we employ the zonal phase speed equation of the linear Rossby wave (Luo et al., 2010),

| ${c_x} = U - \frac{{({β} - {U^{''}})}}{{{k^2} + {m^2}}}, $ | (2) |

where U is basic zonal wind,

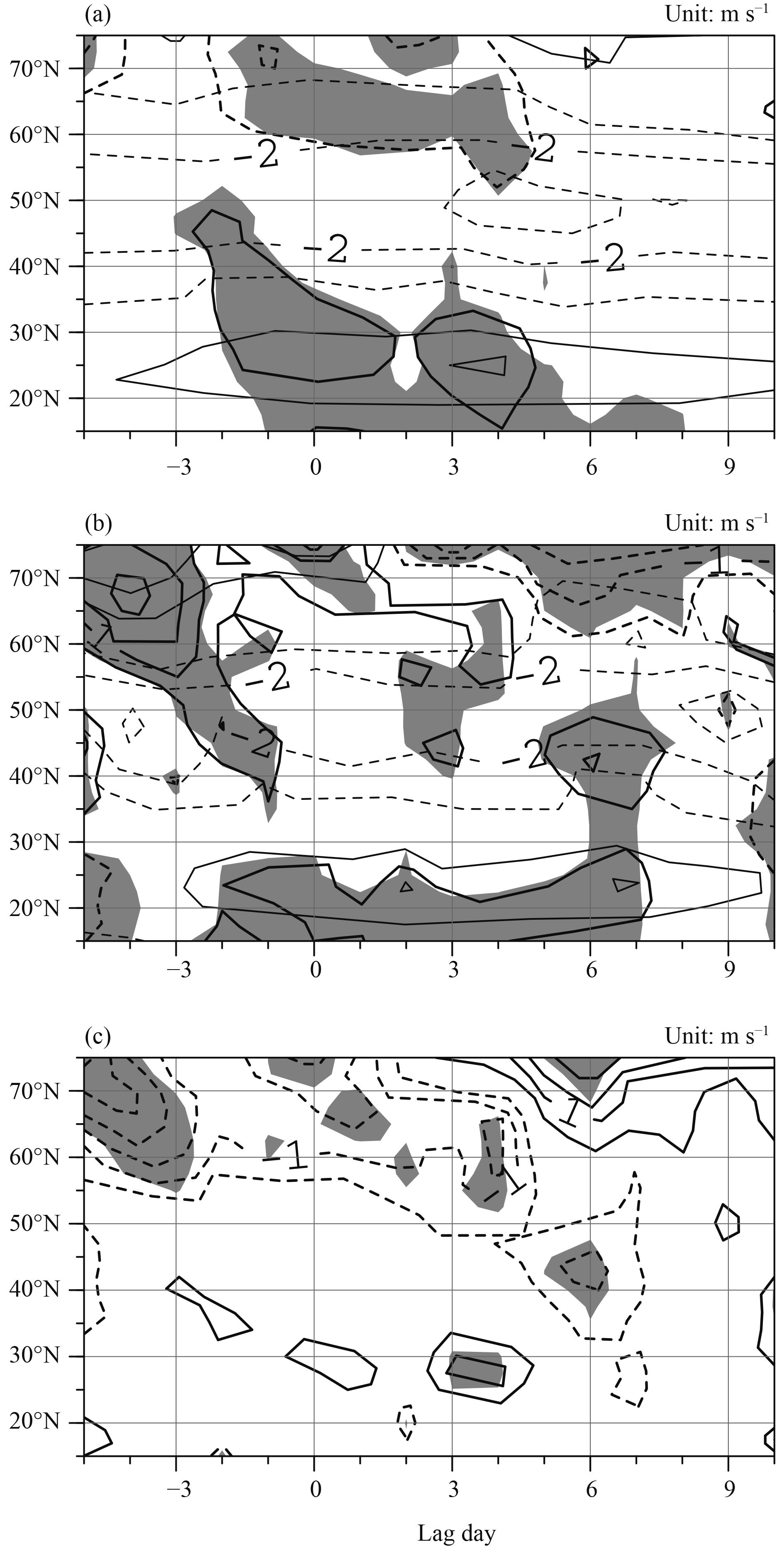

The circulation features of medium NAO+ events bear resemblance to strong NAO+ events at the upper levels. The circulation differences at the lower levels (e.g., 850 hPa) are more prominent between NAO+ events of different amplitudes, and may be responsible for the meridional displacement of precipitation. Figure 10 displays composites of 850-hPa wind for strong and medium NAO+ events, and their difference. The atmospheric circulation features at lower levels are distinct between NAO+ events of different amplitudes. The strengthened southerly winds expand to north of 30°N for strong NAO+ events, while they are limited to south of 25°N for medium NAO+ events. This is clear in the difference between the 850-hPa winds (Fig. 10c), and may account for the latitudinal difference in precipitation between strong and medium NAO+ events.

|

| Figure 10 Time–latitude cross-section of 850-hPa wind (thin contours), and departure from climatology (thick contours), from day(–5) to day(+10), for (a) strong NAO+ events, (b) medium NAO+ events, and (c) their difference (thick contours). Contour interval: 1.0 m s–1. Shading denotes statistical significance at the 90% confidence level for 850-hPa meridional wind anomalies in (a, b), and for meridional wind difference in (c). |

This paper studies the synoptic features of precipitation regimes in southeastern China during wintertime, and their relation to the teleconnections over the North Atlantic Ocean. The results show that precipitation occurs mainly over the Yangtze and Pearl River basins, in two major separate precipitation regimes (R1 and R2). Time-lagged analysis shows that the two precipitation regimes are connected with the decaying phases of NAO+ events. When a strong NAO+ begins to decay, the downstream propagation of a wave-train-like anomaly is obvious, with an enhanced subtropical anticyclone over the western Pacific. As the strengthened southerly winds expand northeastward along the western flank of the western Pacific subtropical anticyclone, precipitation is enhanced over the Yangtze River basin. During the decaying phase of medium NAO+ events, southerly winds are confined to the area south of 25°N, and precipitation is mainly limited in South China. Thus, R1 is connected with the decay of strong NAO+ events, while R2 accompanies the decay of medium NAO+ events. As NAO+ leads the precipitation regimes by several days, the finding of this study is useful in medium-range forecasts of wintertime precipitation over southeastern China. It should be noted, however, that only the association between NAO decay and persistent precipitation regimes has been discussed. Small-scale precipitation may be controlled by regional mesoscale systems and is not in the scope of this study.

The two precipitation regimes are also investigated from the perspective of other teleconnections. A number of studies have examined the impacts of the Eurasian teleconnection (EU) on the temperature and precipitation over East Asia (Sung et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2014). The circulation pattern for R2 (Fig. 6) also bears resemblance to the EU pattern. However, the precipitation occurs mainly over North China during negative EU phases (Wang and Zhang, 2015). There is no obvious precipitation anomaly over southeastern China during the evolution of the EU (figure omitted).

Finally, it should be noted that, in this paper, a blocking ridge tends to become enhanced over the Ural Mountains (60°E) on day(0) of the evolution of strong NAO+ events (Fig. 10a). However, the Ural blocking can take place during both phases of the NAO (Li et al., 2012), but with different synoptic characteristics. As the Ural blocking has important effects on the EAWM (Li, 2004), a more comprehensive discussion on the relationship between the Ural blocking and the NAO is currently under way and will be reported in a future paper.

| Ambaum M. H. P., Hoskins B. J., Stephenson D. B., 2001: Arctic Oscillation or North Atlantic Oscillation?. J. Climate, 14, 3495–3507. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(2001)014<3495:AOONAO>2.0.CO;2 |

| Archambault H. M., Keyser D., Bosart L. F., 2010: Relationships between large-scale regime transitions and major cool-season precipitation events in the northeastern United States. Mon. Wea. Rev., 138, 3454–3473. DOI:10.1175/2010MWR3362.1 |

| Barnston A. G., Livezey R. E., 1987: Classification, seasonality and persistence of low-frequency atmospheric circulation patterns. Mon. Wea. Rev., 115, 1083–1126. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1987)115<1083:CSAPOL>2.0.CO;2 |

| Cassou C., 2008: Intraseasonal interaction between the Madden-Julian Oscillation and the North Atlantic Oscillation. Nature, 455, 523–527. DOI:10.1038/nature07286 |

| Chen H. P., Wang H. J., 2015: Haze days in north China and the associated atmospheric circulations based on daily visibility data from 1960 to 2012. J. Geophys. Res., 120, 5895–5909. |

| Chen Z., Wu R. G., Chen W., 2014: Distinguishing inter-annual variations of the northern and southern modes of the East Asian winter monsoon. J. Climate, 27, 835–851. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00314.1 |

| Compo G. P., Kiladis G. N., Webster P. J., 1999: The horizontal and vertical structure of East Asian winter monsoon pressure surges. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 125, 29–54. DOI:10.1002/qj.49712555304 |

| Dole R. M., 1986: Persistent anomalies of the extratropical Northern Hemisphere wintertime circulation: Structure. Mon. Wea. Rev., 114, 178–207. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1986)114<0178:PAOTEN>2.0.CO;2 |

| Feldstein S. B., 2003: The dynamics of NAO teleconnection pattern growth and decay. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 129, 901–924. DOI:10.1256/qj.02.76 |

| Han Z. Y., Zhou T. J., 2012: Assessing the quality of APHRODITE high-resolution daily precipitation dataset over contiguous China. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 36, 361–373. |

| Hoskins B. J., Ambrizzi T., 1993: Rossby wave propagation on a realistic longitudinally varying flow. J. Atmos. Sci., 50, 1661–1671. DOI:10.1175/1520-0469(1993)050<1661:RWPOAR>2.0.CO;2 |

| Huang R. H., Zhou L. T., Chen W., 2003: The progresses of recent studies on the variabilities of the East Asian monsoon and their causes. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 20, 55–69. DOI:10.1007/BF03342050 |

| Hurrell J. W., 1995: Decadal trends in the North Atlantic Oscillation: Regional temperatures and precipitation. Science, 269, 676–679. DOI:10.1126/science.269.5224.676 |

| Jhun J. G., Lee E. J., 2004: A new East Asian winter monsoon index and associated characteristics of the winter monsoon. J. Climate, 17, 711–726. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<0711:ANEAWM>2.0.CO;2 |

| Johansson Å., 2007: Prediction skill of the NAO and PNA from daily to seasonal timescales. J. Climate, 20, 1957–1975. DOI:10.1175/JCLI4072.1 |

| Kalnay E., Kanamitsu M., Kistler R., et al.,1996: The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 77, 437–471. DOI:10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077<0437:TNYRP>2.0.CO;2 |

| Leathers D. J., Yarnal B., Palecki M. A., 1991: The Pacific/North American teleconnection pattern and United States climate. Part I: Regional temperature and precipitation associations. J. Climate, 4, 517–528. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(1991)004<0517:TPATPA>2.0.CO;2 |

| Li C., Ma H., 2012: Relationship between ENSO and winter rainfall over Southeast China and its decadal variability. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 29, 1129–1141. DOI:10.1007/s00376-012-1248-z |

| Li C., Zhang Q. Y., 2013: January temperature anomalies over Northeast China and precursors. Chinese Sci. Bull., 58, 671–677. DOI:10.1007/s11434-012-5467-6 |

| Li C., Sun J. L., 2015: Role of the subtropical westerly jet waveguide in a southern China heavy rainstorm in December 2013. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 32, 601–612. DOI:10.1007/s00376-014-4099-y |

| Li C., Zhang Q. Y., 2015: An observed connection between wintertime temperature anomalies over Northwest China and weather regime transitions in North Atlantic. J. Meteor. Res., 29, 201–213. DOI:10.1007/s13351-015-4066-2 |

| Li C., Zhang Q. Y., Ji L. R., et al.,2012: Interannual variations of the blocking high over the Ural Mountains and its association with the AO/NAO in boreal winter. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 26, 163–175. DOI:10.1007/s13351-012-0203-3 |

| Li S. L., 2004: Impact of Northwest Atlantic SST anomalies on the circulation over the Ural Mountains during early winter. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan, 82, 971–988. DOI:10.2151/jmsj.2004.971 |

| Liu G., Ji L. R., Wu R. G., 2012: An east–west SST anomaly pattern in the midlatitude North Atlantic Ocean associated with winter precipitation variability over eastern China. J. Geophys. Res., 117(D15), D15104. DOI:10.1029/2012JD017960 |

| Liu Y. Y., Wang L., Zhou W., et al.,2014: Three Eurasian teleconnection patterns: Spatial structures, temporal variability, and associated winter climate anomalies. Climate Dyn., 42, 2817–2839. DOI:10.1007/s00382-014-2163-z |

| Luo D. H., Zhu Z. H., Ren R. C., et al.,2010: Spatial pattern and zonal shift of the North Atlantic Oscillation. Part I: A dynamical interpretation. J. Atmos. Sci., 67, 2805–2826. DOI:10.1175/2010JAS3345.1 |

| Luo D. H., Cha J., Feldstein S. B., 2012: Weather regime transitions and the interannual variability of the North Atlantic Oscillation. Part I: A likely connection. J. Atmos. Sci., 69, 2329–2346. DOI:10.1175/JAS-D-11-0289.1 |

| Luo D. H., Yao Y., Feldstein S. B., 2014: Regime transition of the North Atlantic Oscillation and the extreme cold event over Europe in January–February 2012. Mon. Wea. Rev., 142, 4735–4757. DOI:10.1175/MWR-D-13-00234.1 |

| Michelangeli P. A., Vautard R., Legras B., 1995: Weather regimes: Recurrence and quasi stationarity. J. Atmos. Sci., 52, 1237–1256. DOI:10.1175/1520-0469(1995)052<1237:WRRAQS>2.0.CO;2 |

| Sung M. K., Lim G. H., Kwon W. T., et al.,2009: Short-term variation of Eurasian pattern and its relation to winter wea-ther over East Asia. Int. J. Climatol., 29, 771–775. DOI:10.1002/joc.v29:5 |

| Takaya K., Nakamura H., 2001: A formulation of a phase-independent wave-activity flux for stationary and migratory quasigeostrophic eddies on a zonally varying basic flow. J. Atmos. Sci., 58, 608–627. DOI:10.1175/1520-0469(2001)058<0608:AFOAPI>2.0.CO;2 |

| Wang H. J., Chen H. P., Liu J. P., 2015: Arctic sea ice decline intensified haze pollution in eastern China. Atmos. Oceanic Sci. Lett., 8, 1–9. |

| Wang L., Feng J., 2011: Two major modes of the wintertime precipitation over China. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 35, 1105–1116. |

| Wang N., Zhang Y. C., 2015: Evolution of Eurasian teleconnection pattern and its relationship to climate anomalies in China. Climate Dyn., 44, 1017–1028. DOI:10.1007/s00382-014-2171-z |

| Watanabe M., 2004: Asian jet waveguide and a downstream extension of the North Atlantic Oscillation. J. Climate, 17, 4674–4691. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-3228.1 |

| Wen M., Yang S., Kumar A., et al.,2009: An analysis of the large-scale climate anomalies associated with the snowstorms affecting China in January 2008. Mon. Wea. Rev., 137, 1111–1131. DOI:10.1175/2008MWR2638.1 |

| Wettstein J. J., Mearns L. O., 2002: The influence of the North Atlantic–Arctic Oscillation on mean, variance, and extremes of temperature in the northeastern United States and Canada. J. Climate, 15, 3586–3600. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(2002)015<3586:TIOTNA>2.0.CO;2 |

| Wu B. Y., Wang J., 2002: Winter Arctic Oscillation, Siberian high and East Asian winter monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett., 29, 3-1–3-4. DOI:10.1029/2002GL015373 |

| Xie P. P., Yatagai A., Chen M. Y., et al.,2007: A gauge-based analysis of daily precipitation over East Asia. J. Hydrometeor., 8, 607–626. DOI:10.1175/JHM583.1 |

| Yatagai A., Kamiguchi K., Arakawa O., et al.,2012: APHRODITE: Constructing a long-term daily gridded precipitation dataset for Asia based on a dense network of rain gauges. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 93, 1401–1415. DOI:10.1175/BAMS-D-11-00122.1 |

| Zhou L. T., 2011: Impact of East Asian winter monsoon on rainfall over southeastern China and its dynamical process. Int. J. Climatol., 31, 677–686. DOI:10.1002/joc.v31.5 |

| Zhou L. T., Wu R. G., 2010: Respective impacts of the East Asian winter monsoon and ENSO on winter rainfall in China. J. Geophys. Res., 115(D2), D02107. DOI:10.1029/2009JD012502 |

| Zhou W., Chan J. C. L., Chen W., et al.,2009: Synoptic-scale controls of persistent low temperature and icy weather over southern China in January 2008. Mon. Wea. Rev., 137, 3978–3991. DOI:10.1175/2009MWR2952.1 |

2017, Vol. 31

2017, Vol. 31