The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- Lei ZHANG, Tim LI. 2017.

- Physical Processes Responsible for the Interannual Variability of Sea Ice Concentration in Arctic in Boreal Autumn since 1979. 2017.

- J. Meteor. Res., 31(3): 468-475

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-017-6105-7

Article History

- Received September 13, 2016

- in final form November 20, 2016

2. Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA

It has been well documented in the previous literatures that the Arctic sea ice concentration (ASIC) has been declining in recent decades (e.g., Johannessen et al., 1995, 1999; Serreze et al., 2007; Comiso et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2014), with a noticeable interannual variability. Change in ASIC not only exerts great local socioeconomic impact (e.g., influence on shipping routes; change in the fresh water flux), but also affects the climate conditions remotely through the atmospheric teleconnection (Honda et al., 2009; Deser et al., 2010; Overland and Wang, 2010; Blüthgen et al., 2012; Francis and Vavrus, 2012; Jaiser et al., 2012). Given its substantial impact, exploring the physical mechanism for the ASIC variability is clearly of great societal and scientific interests.

Cause of the ASIC variability in the past few decades has been examined in numerous studies (e.g., Zhang et al., 2000; Serreze et al., 2007; Stroeve et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2008; Kay et al., 2011; Francis and Vavrus, 2012), and there has been an intense debate on the relative importance of the dynamic and thermodynamic processes that contribute to the ASIC variability (e.g., Hilmer and Lemke, 2000; Serreze et al., 2007; Kay et al., 2012). The surface-albedo feedback (Hall, 2004; Winton, 2006; Gorodetskaya et al., 2008), horizontal heat transport (Holland and Bitz, 2003; Shimada et al., 2006; Mahlstein and Knutti, 2011), and the longwave radiative feedback that involves changes in air temperature, moisture, and cloudiness, have all been considered as important processes for the ASIC variability (Boer and Yu, 2003; Boé et al., 2009). In contrast, it is also argued that anomalous ice motion is crucial for the ASIC changes (Zhang et al., 2000; Makshtas et al., 2003; Vavrus and Harrison, 2003).

In this study, we mainly focus on the physical processes that cause the observed interannual variability of ASIC in the recent decades. The remaining part of this paper is organized as follows. The data and method are des-cribed in Section 2. Physical mechanism for the ASIC interannual variability during boreal autumn is analyzed in Section 3. A conclusion is given in the last section.

2 Data and methodSea ice concentration dataset from Hadley Center (Rayner et al., 2003) is employed in this study. Atmospheric 3-D winds, sea level pressure (SLP), precipitable water, and total cloud cover from NCEP2 reanalysis datasets, precipitation data from Global Precipitation Climatology Project (GPCP) (Huffman et al., 2009), and monthly sea surface temperature (SST) dataset from NOAA Optimum Interpolation SST v2 (Reynolds et al., 2002) are analyzed. Besides, monthly surface heat fluxes from NCEP reanalysis 2.0 datasets are also used for analysis (Kanamitsu et al., 2002). All the datasets cover the period of 1979–2015 except for the SST data, which start from the year 1982. Composite analysis is used to examine the differences of ASIC, surface heat fluxes, and other atmospheric fields between lower- and higher-than normal ice years.

As will be shown in the following section, numerical experiments are conducted to examine the role of the tropical forcing in the ASIC interannual variability through the atmospheric teleconnection. The atmospheric general circulation model (AGCM) experiments were conducted by using the Max Planck Institute (MPI) ECHAM4.6 at T42 horizontal resolution (corresponding to 2.8125° × 2.8125° grid resolution) with 19 vertical levels (Roeckner et al., 1996). This model has been shown to simulate the climate mean state reasonably well and has been widely used for climate research (e.g., Zhang and Li, 2016). For both control run (CTRL) and sensitivity experiment, the model was integrated for 20 years, and results from the last 15 years are analyzed. The experiment design is described in more details in Section 3.

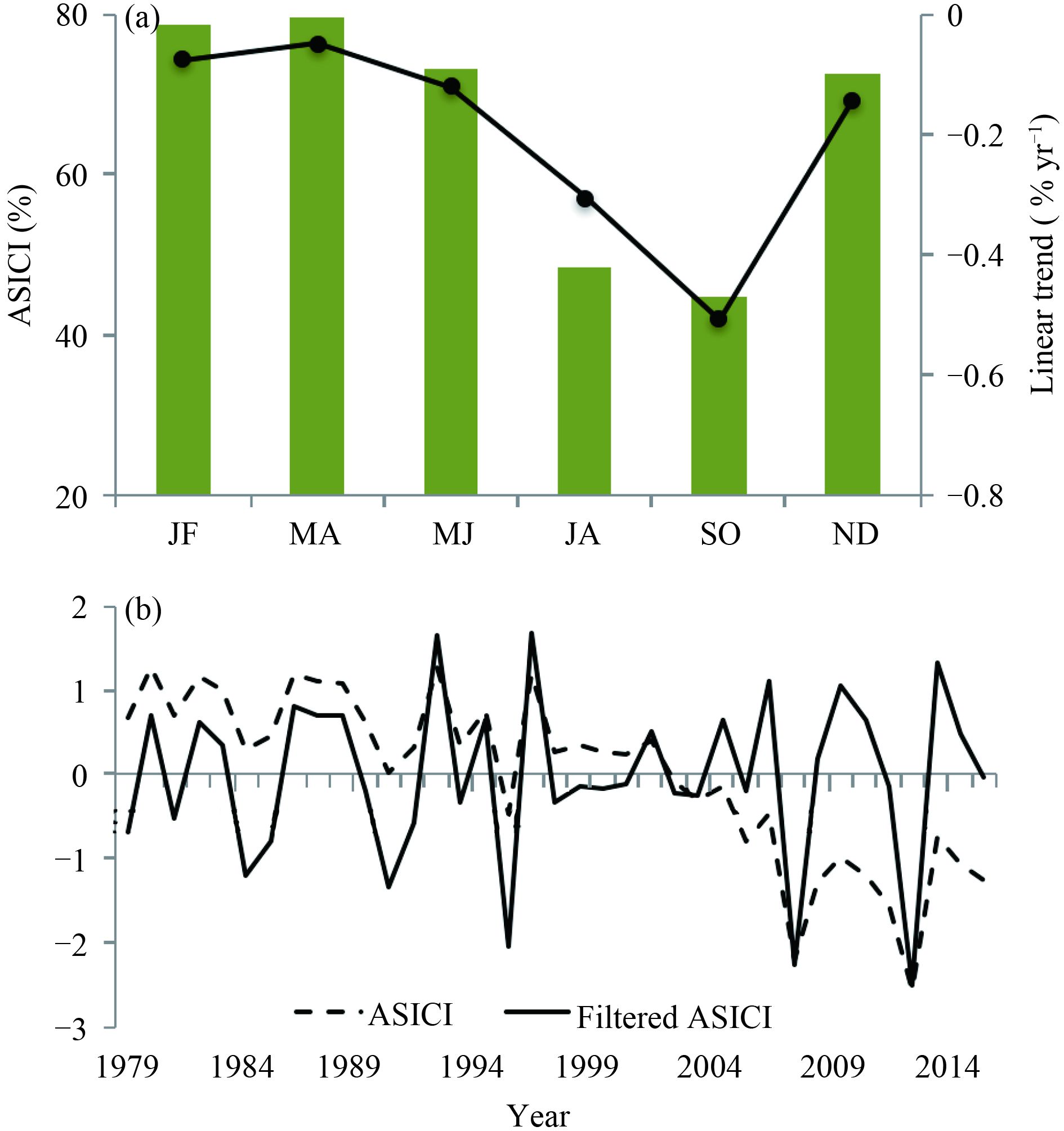

3 Physical mechanism for the ASIC interannual variabilityAn ASIC index (ASICI) is defined to analyze the ASIC variability, which is the area averaged sea ice concentration to the north of 66.5°N. Climatologically, ASICI exhibits a pronounced seasonal evolution, with a minimum in September and October (SO), and a peak in March and April (Fig. 1a). Linear trends of the two month-mean ASICI during 1979–2015 are negative all year around, with the most evident decreasing trend in SO (Fig. 1a). On top of the long-term trend, ASIC exhibits a significant year-to-year variation as well. The variance of ASICI on the interannual timescale (after removing the long-term linear trend) also peaks in SO (figure omitted). The reason why ASIC exhibits the most significant variability in SO is due to the smaller and thinner ice cover in that season (Fig. 1a), which makes the sea ice more susceptible to break-up and more easily affected by other forcing (e.g., Meier et al., 2005; Stroeve et al., 2008).

|

| Figure 1 (a) Climatological annual cycle of two-month mean ASICI (bar; %) and the long-term linear trend of ASICI (line; % yr–1); (b) Time evolution of the normalized September–October (SO) ASICI (solid) and filtered ASICI (dashed line, period greater than 10 yr removed). |

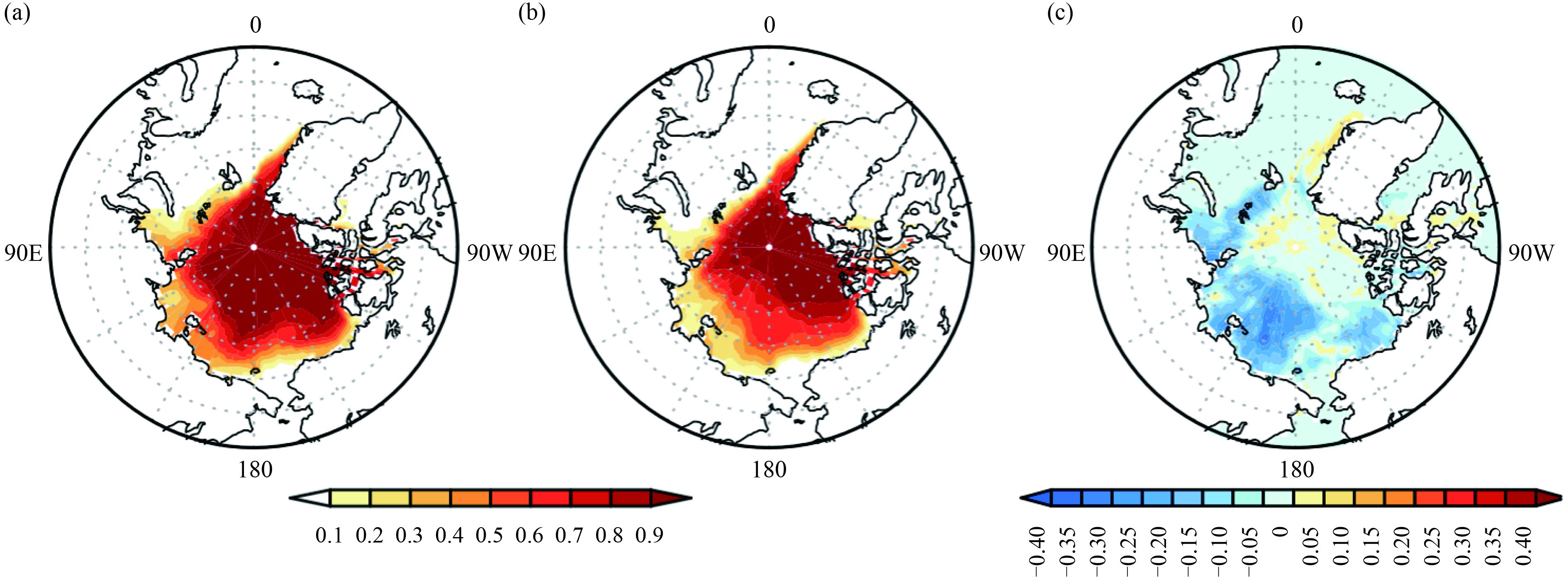

Time evolution of the normalized ASICI in SO indeed exhibits a prominent decreasing trend and a significant interannual variability (Fig. 1b). To examine the physical mechanism for the ASIC interannual variability, the years with absolute standard deviation (std) of the detrended normalized ASICI greater than 1 are picked out (Fig. 1b). The selected higher-than-normal ice years are 1992, 1996, 2006, 2009, and 2013; lower-than-normal ice years are 1984, 1990, 1995, 2007, and 2012. The ASIC difference between lower and higher ice years exhibits the most pronounced reduction at the edge of the perennial ice cover (Fig. 2), where the sea ice is thinner and more vulnerable.

|

| Figure 2 Distributions of SIC in SO to the north of 60°N during (a) higher-than-normal ice years and (b) lower-than-normal ice years. (c) Difference between lower and higher ice years (lower–higher). |

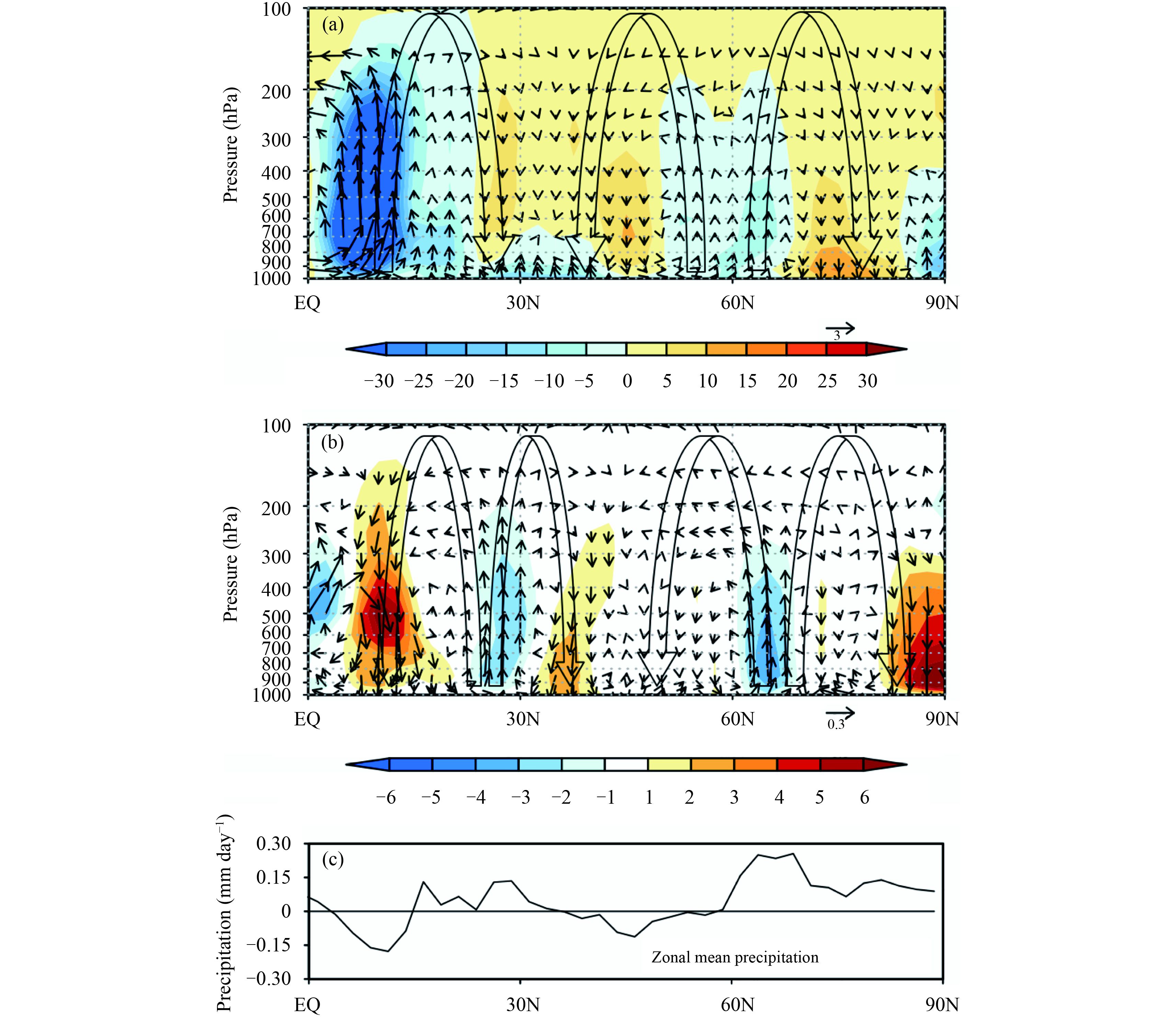

To explore the large-scale features that affect the ASIC interannual variability, composites of the large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns during lower and higher ASIC years are examined. We focus on the tropospheric conditions in July and August (JA), that is, two months before the largest ASIC variability (SO), to examine the processes that affect the tendency of the ASIC. Climatologically, strong ascending branch of the Hadley cell and the associated abundant rainfall are located to the north of the equator in boreal summer. During lower-than-normal ASIC years, the Hadley cell is strengthened and shifted poleward, accompanied by a similar poleward shift in the tropical precipitation (Fig. 3). Meanwhile, the meridional overturning circulations (Hadley cell, Ferrell cell, and thermally direct cell over the polar region) over the Northern Hemisphere shift poleward as well (Fig. 3b).

|

| Figure 3 (a) zonal mean vertical p-velocity (shading; 10–3 Pa s–1) and meridional overturning circulation (vector; m s–1 for meridional wind and –10–2 Pa s–1 for the vertical p-velocity) in JA in higher-than-normal ice year. (b) Same as (a) but for the differences between lower and higher ice years (lower–higher). (c) Differences of the zonal mean precipitation between lower and higher ice years (lower–higher; mm day–1). |

Associated with such changes, anomalous surface outflow shows up over the northern Polar region (Fig. 3b), which turns into easterly anomaly due to the Coriolis force and reduces the surface wind speed (Fig. 4b). Besides, the enhanced meridional circulation during lower-than-normal ASIC years leads to a descending motion anomaly and a higher SLP at the North Pole, which is surrounded by an ascending motion anomaly and anomalous surface convergence over the lower latitude (Figs. 3b, 4b). Such anomalous circulations induce a ring-like positive cloudiness change (Fig. 4a). Kay and Gettelman (2009) found that the year-to-year variation of the cloudiness over Arctic in boreal summer is primarily controlled by the large-scale atmospheric circulation, not the newly opened ocean water because of limited air–sea coupling. Indeed, there are pronounced discrepancies between the positive cloudiness and the negative ASIC (Figs. 2c, 4a; correlation coefficient about –0.22). In contrast, the cloud difference resembles the patterns of surface convergence and SLP difference (Figs. 4a, b). The spatial correlation coefficient between cloudiness difference and SLP anomaly is –0.48. The pattern of the precipitable water anomaly also resembles that of the surface convergence anomaly (figure omitted).

|

| Figure 4 (a) Differences of the total cloud cover (shading) and surface divergence fields (contour; with interval 0.5 × 10–6 s–1) in JA between lower and higher ice years. (b) Differences of SLP (shading; hPa) and surface zonal wind (contour; m s–1). |

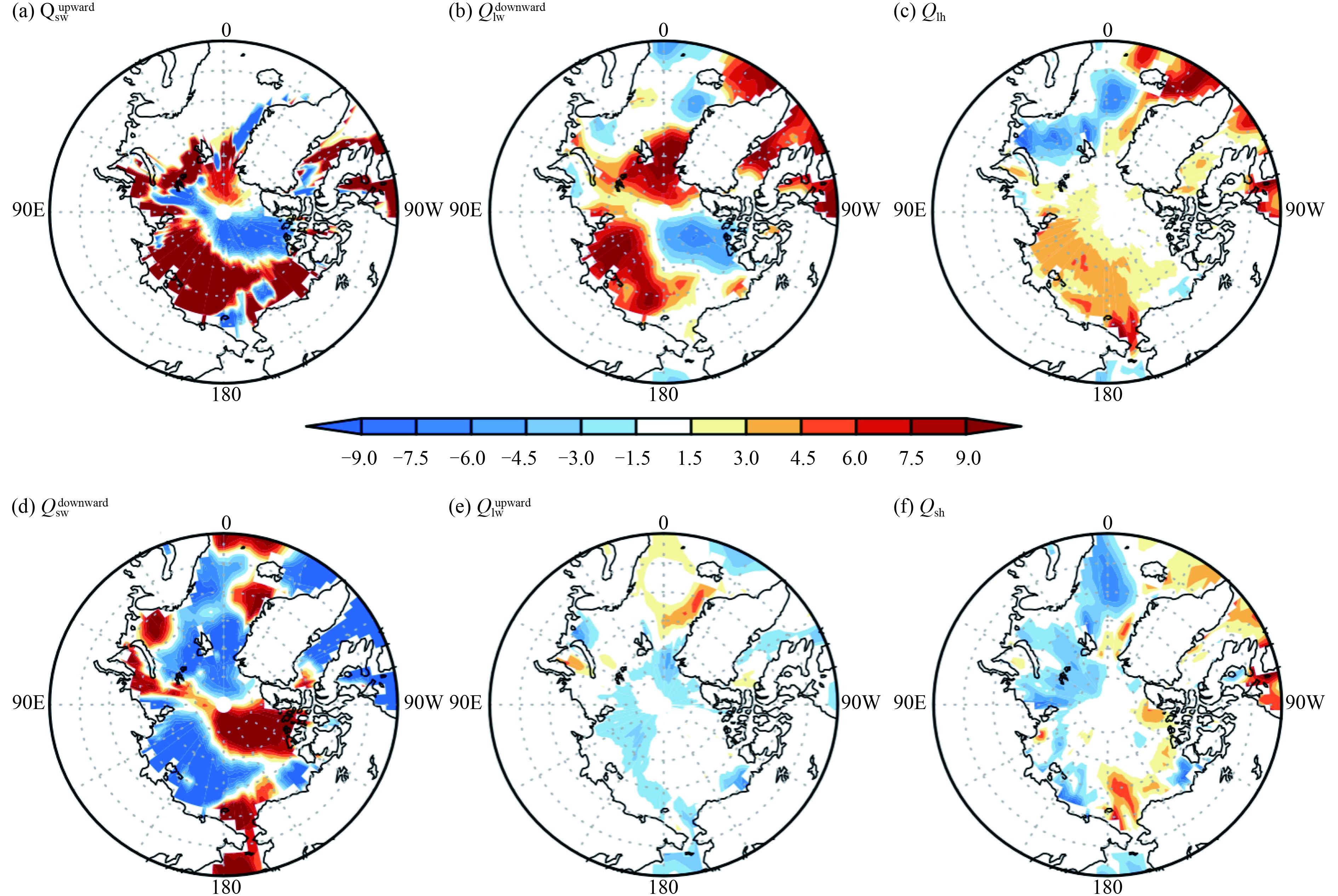

These changes in the tropospheric conditions may affect SST and SIC in Arctic substantially through changes in the surface heat fluxes (Fig. 5). For instance, less surface latent heat flux (Qlh) associated with the aforementioned surface easterly anomaly (opposing the mean state wind), which is further related to the enhanced meridional circulation over the Northern Polar region, contributes to the surface warming and ASIC reduction (Fig. 5c). We also find that the pattern of the positive surface downward longwave radiation (

|

| Figure 5 Spatial patterns of differences of the surface heat fluxes (W m–2) in JA between lower and higher ice years (lower–higher): (a) upward shortwave radiation, (b) downward longwave radiation, (c) surface latent heat flux, (d) downward shortwave radiation, (e) upward longwave radiation, and (f) sensible heat flux. Positive values mean that ocean receives heat. |

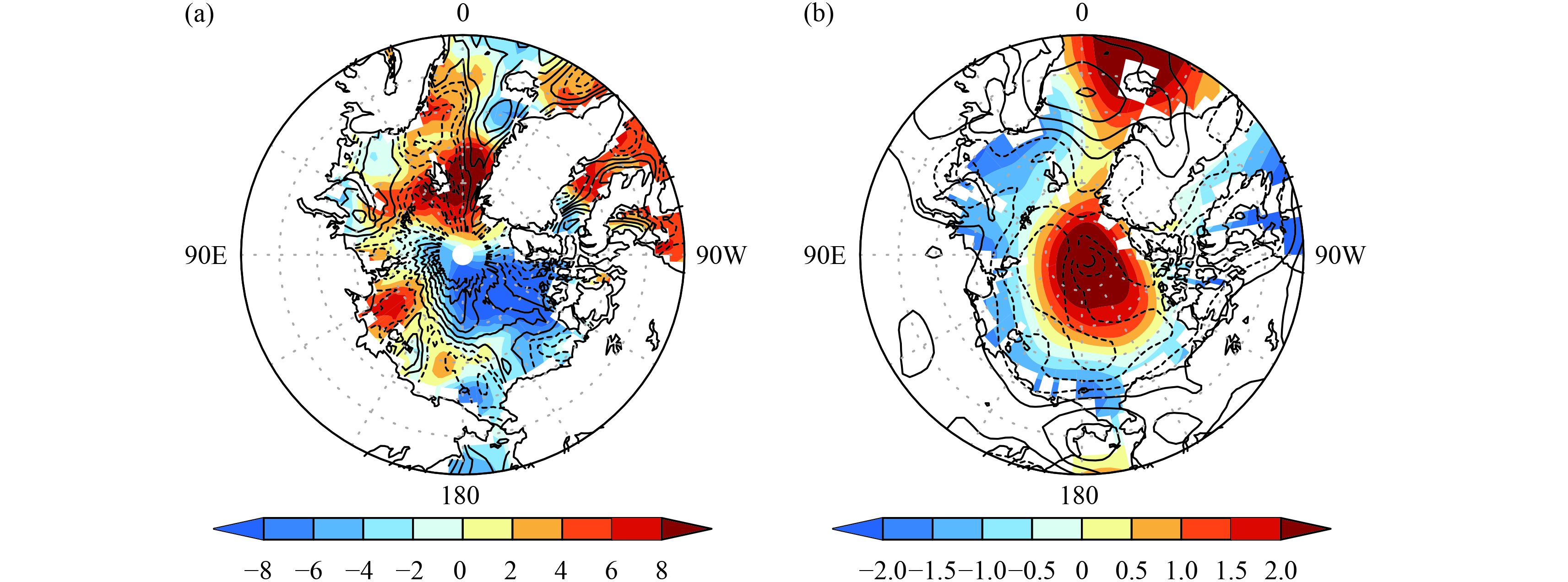

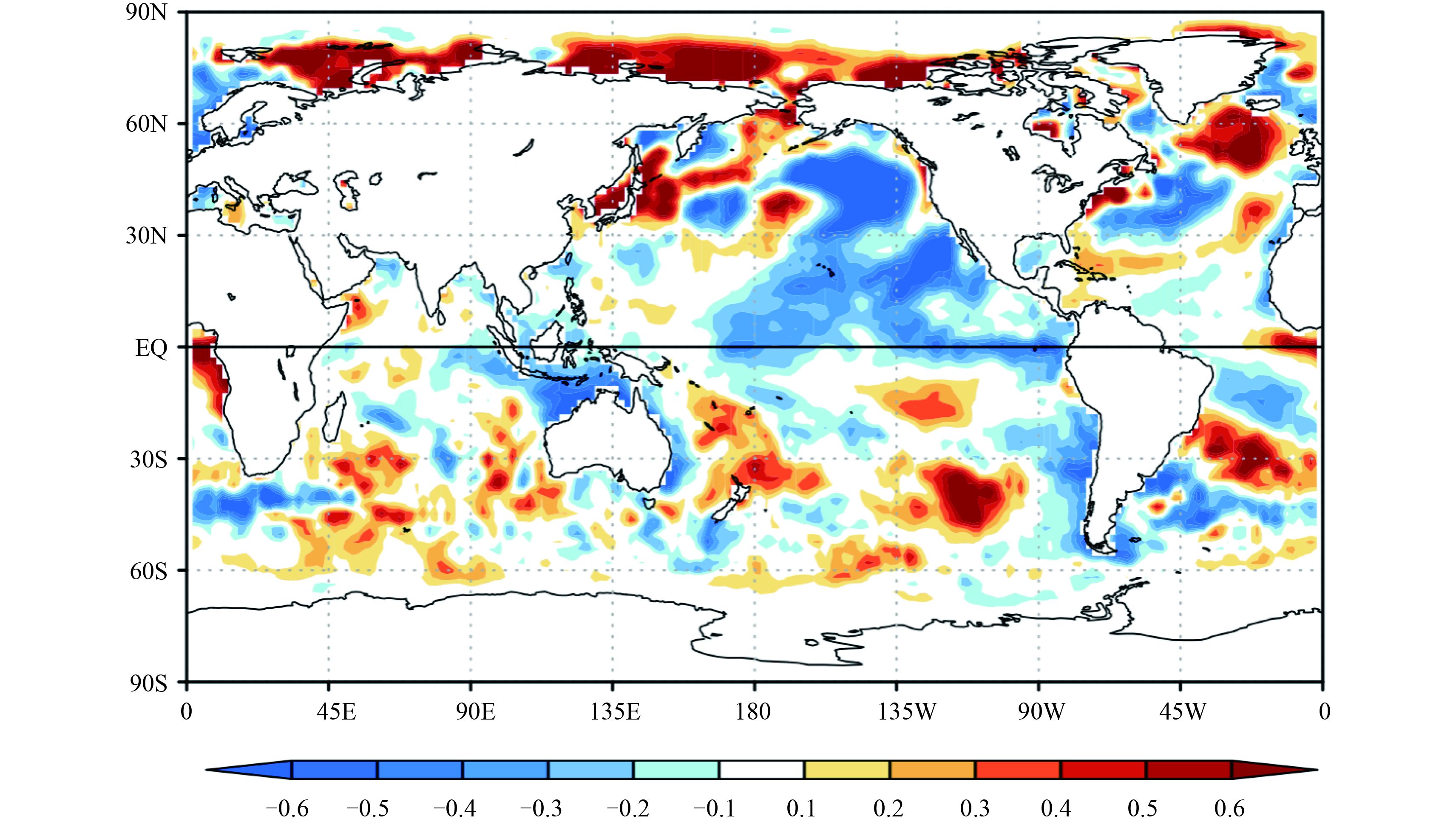

Hence, it is clear that the ASIC interannual variability is closely related to the anomalous large-scale meridional circulations over the Northern Hemisphere. Composite analysis of SST further reveals that the anomalous atmospheric circulation over Arctic seems related to the remote tropical forcing (Fig. 6). We note that SST is consistently lower in most of the tropical region during lower-than-normal ASIC years. Since the rising branch of the Hadley cell and high SST are located in the Northern Hemisphere in boreal summer (Fig. 3a), such SST anomalies may lead to a stronger meridional SST gradient to the north of the equator (Figs. 3b, 6), which may thereby induce the northward shift and strengthening of the Hadley cell. As a result, all of the meridional cells in the Northern Hemisphere shift poleward, which may subsequently affect the ASIC through changes in the surface heat fluxes.

|

| Figure 6 Differences of the SST field (K) in JA between lower and higher ice years (lower–higher). |

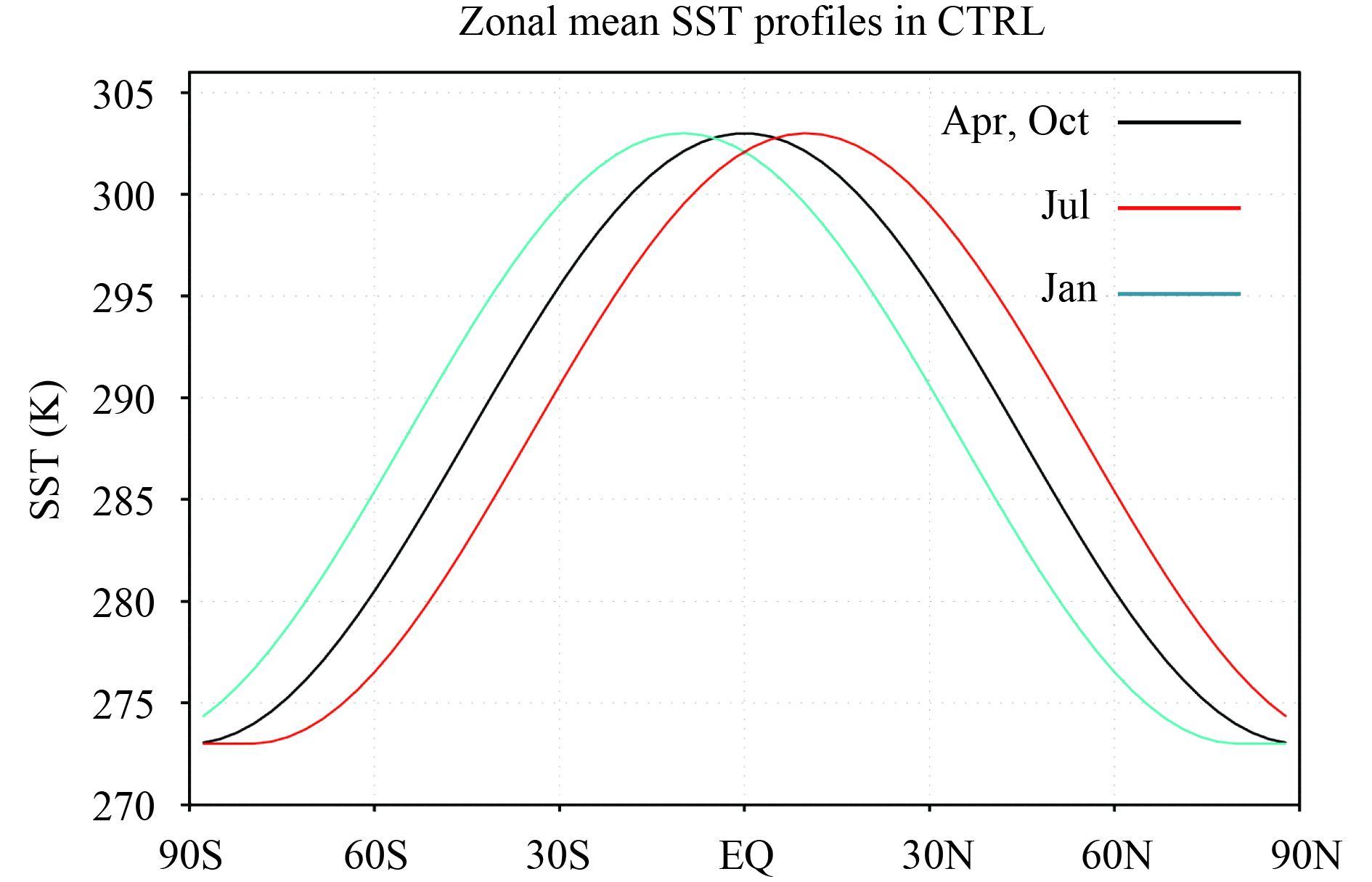

The mechanism through which the tropical SST anomaly drives the anomalous meridional overturning circulations is examined by using the AGCM experiments. Given that the aforementioned mechanism does not depend on the land–sea distribution, to simplify the problem, idealized aqua planet experiments were conducted. The SST profile was specified as a function of the latitude only, which peaks in the tropical region and decreases gradually toward the polar region (Fig. 7). The north–south seasonal march of the SST pattern was also included, with a peak located to the north (south) of the equator in July (January) (Fig. 7). In addition to the CTRL, a sensitivity experiment was conducted by adding 1-K uniform surface cooling in the tropical region within 15°N and 15°S during May–August, which is expected to simulate the atmospheric state during the lower-than-normal ASIC years. This experiment is named as TPC.

|

| Figure 7 Specified zonal mean SST (K) profiles in CTRL in different months. Black denotes the zonal mean SST distribution in April and October, red for July, and green for January. |

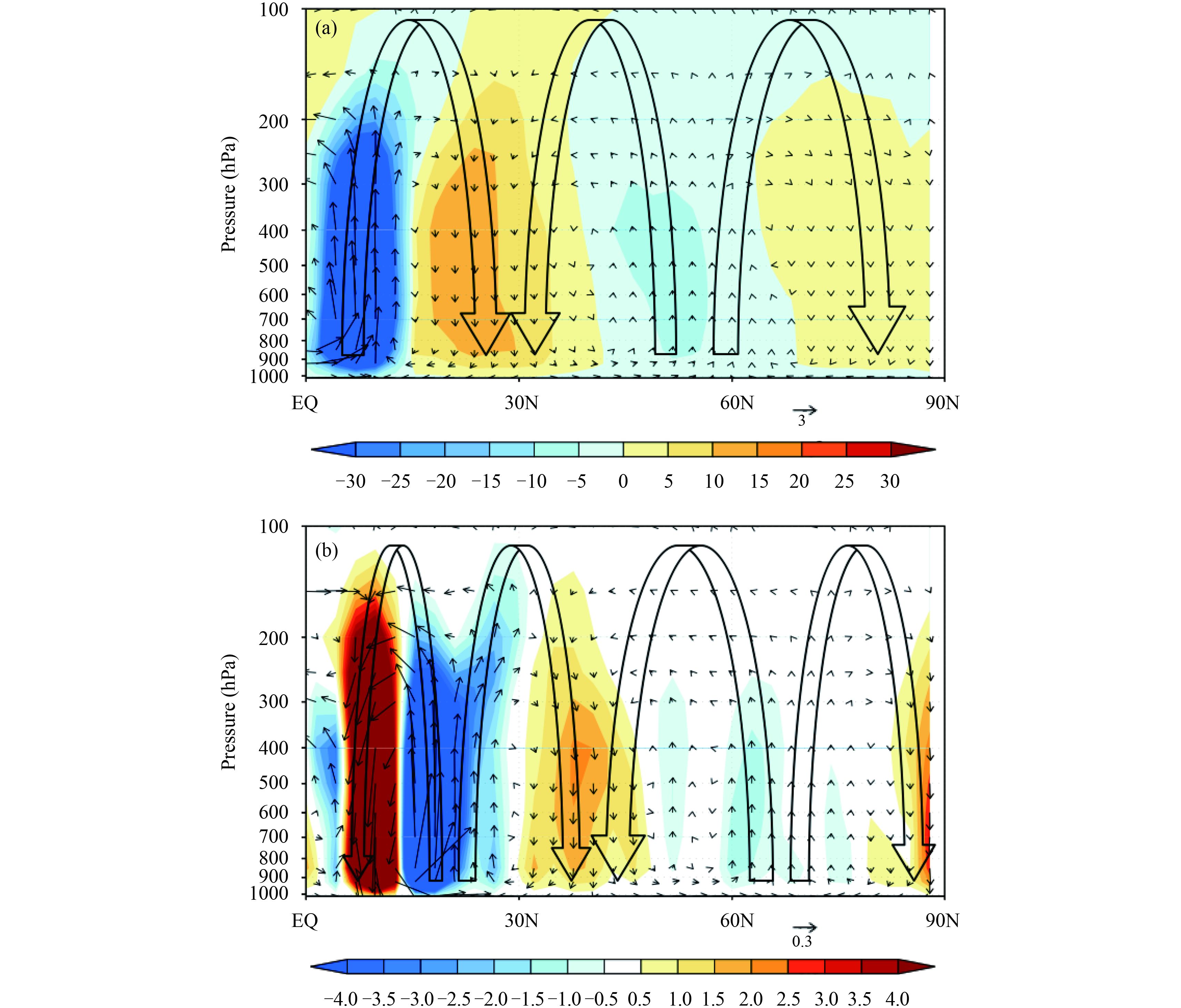

The results from the numerical simulations are shown in Fig. 8. Strong ascending motion to the north of the equator and the meridional overturning circulations are simulated in CTRL reasonably well compared to the observations (Figs. 3a, 8a). In the tropical cooling experiment (TPC), the strongest upward motion in the tropics shifts poleward in response to the equatorial SST cooling (Fig. 8b), accompanied by the northward displacement of the three meridional cells in the Northern Hemisphere. The anomalous downward motion and the surface outflow indeed show up over the Northern Polar region (Fig. 8b), which are the two important features for the ASIC reduction during the lower ASIC years in observation. Note that there is no sea ice effect in the aqua-planet experiment, but this should not affect the reliability of the tropical SST forcing-induced atmospheric circulation anomaly over Arctic in the model because the intent of the AGCM experiments is to analyze the impact of the tropical forcing on the large-scale meridional circulations. The subsequent impact on the ASIC through modulating the surface heat fluxes is relatively more straightforward.

|

| Figure 8 (a) Zonal mean vertical p-velocity (shading; 10–3 Pa s–1) and meridional overturning circulation (vector; m s–1 for meridional wind and –10–2 Pa s–1 for the vertical p-velocity) in CTRL averaged during May–August. (b) Differences between TPC and CTRL (TPC–CTRL). |

ASIC in SO exhibits a pronounced decreasing trend with noticeable year-to-year variation since 1979. The cause of the prominent ASIC interannual variability is investigated through diagnoses of reanalysis data and idealized numerical experiments. We found that the ASIC reduction on the interannual timescale is related to the large-scale tropospheric circulation anomalies over the Northern Hemisphere. During lower-than-normal ASIC years, the meridional circulations are enhanced and pushed poleward over the Northern Hemisphere. Consequently, a substantial downward motion anomaly shows up at the North Pole, surrounded by ascending motion anomaly and anomalous low-level convergence. Such circulation anomaly induces a ring-like positive cloudiness change that reduces the ASIC through change in

The anomalous tropospheric circulations that play an important role in the ASIC change on the interannual timescale is further linked to the tropics-wide SST forcing. During the years when there is anomalous surface cooling (warming) in the tropical oceans, the mean meridional overturning circulations in the Northern Hemisphere are pushed poleward (retreat southward) and strengthened (weakened) in boreal summer because of the anomalous meridional SST gradient in the tropics, which may subsequently affect the ASIC anomaly through changes in

One weakness of this study, however, is the use of the NCEP reanalysis, given that it has been suggested that the characteristics of the surface heat fluxes and cloudiness might be model dependent (Lindsay et al., 2014), and hence, the results need to be treated with caution. We also analyzed the ERA-Interim reanalysis data for comparison, which exhibits a similar anomalous meridional circulation pattern that is associated with the ASIC anomalies, but the cloud response over the Arctic differs substantially from that in the NCEP2 reanalysis. In this study, we mainly focus on analysis of the sea ice concentration, but one needs to bear in mind that SIC could not entirely reflect change in the sea ice thickness. Lastly, we mainly focus on the thermodynamic processes associated with the anomalous atmospheric state in this study, whereas it is possible that the oceanic processes and the sea ice advection may also contribute to the interannual variability of the ASIC.

Acknowledgement. This work was supported by the International Pacific Research Center that is partially sponsored by the Japan Agency for Marine–Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC). This is SOEST contribution number 9871, IPRC contribution number 1225, and ESMC contribution number 135.

| Blüthgen J., Gerdes R., Werner M., 2012: Atmospheric response to the extreme Arctic sea ice conditions in 2007. Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L02707. DOI:10.1029/2011GL050486 |

| Boé J., Hall A., Qu X., 2009: Current GCMs’ unrealistic negative feedback in the Arctic. J. Climate, 22, 4682–4695. DOI:10.1175/2009JCLI2885.1 |

| Boer G., Yu B., 2003: Climate sensitivity and response. Climate Dyn., 20, 415–429. |

| Comiso J. C., Parkinson C. L., Gersten R., et al.,2008: Accelerated decline in the Arctic sea ice cover. Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, L031972. |

| Deser C., Tomas R., Alexer M., et al.,2010: The seasonal atmospheric response to projected Arctic sea ice loss in the late twenty-first century. J. Climate, 23, 333–351. DOI:10.1175/2009JCLI3053.1 |

| Francis J. A., Vavrus S. J., 2012: Evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather in midlatitudes. Geophys. Res. Lett., 39, L06801. |

| Gorodetskaya I. V., Tremblay L. B., Liepert B., et al.,2008: The influence of cloud and surface properties on the Arctic Ocean shortwave radiation budget in coupled models. J. Climate, 21, 866–882. DOI:10.1175/2007JCLI1614.1 |

| Hall A., 2004: The role of surface albedo feedback in climate. J. Climate, 17, 1550–1568. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(2004)017<1550:TROSAF>2.0.CO;2 |

| Hilmer M., Lemke P., 2000: On the decrease of Arctic sea ice volume. Geophys. Res. Lett., 27, 3751–3754. DOI:10.1029/2000GL011403 |

| Holl M. M., Bitz C. M., 2003: Polar amplification of climate change in coupled models. Climate Dyn., 21, 221–232. DOI:10.1007/s00382-003-0332-6 |

| Honda M., Inoue J., Yamane S., 2009: Influence of low Arctic sea-ice minima on anomalously cold Eurasian winters. Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, L08707. |

| Huffman G. J., Adler R. F., Bolvin D.T., et al.,2009: Improving the global precipitation record: GPCP version 2.1. Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, L17808. DOI:10.1029/2009GL040000 |

| Jaiser R., Dethloff K., Horf D., et al.,2012: Impact of sea ice cover changes on the Northern Hemisphere atmospheric winter circulation. Tellus, 64, 11595. DOI:10.3402/tellusa.v64i0.11595 |

| Johannessen O. M., Miles M., Bjørgo E., 1995: The Arctic’s shrinking sea ice. Nature, 376, 126–127. DOI:10.1038/376126a0 |

| Johannessen O. M., Shalina E. V., Miles M. W., 1999: Satellite evidence for an Arctic sea ice cover in transformation. Science, 286, 1937–1939. DOI:10.1126/science.286.5446.1937 |

| Kanamitsu M., Ebisuzaki W., Woollen J., et al.,2002: NCEP-DOE AMIP-II Reanalysis (R-2). Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 83, 1631–1643. DOI:10.1175/BAMS-83-11-1631 |

| Kay J. E., Gettelman A., 2009: Cloud influence on and response to seasonal Arctic sea ice loss. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 114(D18), D18204. DOI:10.1029/2009JD011773 |

| Kay J. E., Holl M. M., Jahn A., 2011: Interannual to multi-decadal Arctic sea ice extent trends in a warming world. Geophys. Res. Lett., 38, L15708. |

| Kay J. E., Holl M. M., Bitz C. M., et al.,2012: The influence of local feedbacks and northward heat transport on the equilibrium Arctic climate response to increased greenhouse gas forcing. J. Climate, 25, 5433–5450. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00622.1 |

| Lindsay R., Wensnahan M., Schweiger A., et al.,2014: Evaluation of seven different atmospheric reanalysis products in the Arctic. J. Climate, 27, 2588–2606. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00014.1 |

| Mahlstein I., Knutti R., 2011: Ocean heat transport as a cause for model uncertainty in projected Arctic warming. J. Climate, 24, 1451–1460. DOI:10.1175/2010JCLI3713.1 |

| Makshtas A. P., Shoutilin S. V., Andreas E. L., 2003: Possible dynamic and thermal causes for the recent decrease in sea ice in the Arctic Basin. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans, 108(C7), 3232. DOI:10.1029/2001JC000878 |

| Meier W., Stroeve J., Fetterer F., et al.,2005: Reductions in Arctic sea ice cover no longer limited to summer. Eos, Trans. Amer. Geophys. Union, 86, 326. |

| Overl J. E., Wang M., 2010: Large-scale atmospheric circulation changes are associated with the recent loss of Arctic sea ice. Tellus A, 62, 1–9. |

| Rayner N. A., Parker D. E., Horton E. B., et al.,2003: Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res., 108(D14), 4407. DOI:10.1029/2002JD002670 |

| Reynolds R. W., Rayner N. A., Smith T. M., et al.,2002: An improved in situ and satellite SST analysis for climate. J. Climate, 15, 1609–1625. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(2002)015<1609:AIISAS>2.0.CO;2 |

| Roeckner, E., K. Arpe, L. Bengtsson, et al., 1996: The Atmospheric General Circulation model ECHAM-4: Model Description and Simulation of Present-Day Climate. Max-Planck-Institut fur Meteorologie Rep. 218, Hamburg, Germany, 90 pp. |

| Serreze M. C., Holl M. M., Stroeve J., 2007: Perspectives on the Arctic’s shrinking sea-ice cover. Science, 315, 1533–1536. DOI:10.1126/science.1139426 |

| Shimada K., Kamoshida T., Itoh M., et al.,2006: Pacific Ocean inflow: Influence on catastrophic reduction of sea ice cover in the Arctic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, L08605. DOI:10.1029/2005GL025624 |

| Stroeve J., Serreze M., Drobot S., et al.,2008: Arctic sea ice extent plummets in 2007. Eos, Trans. Amer. Geophys. Union, 89, 13–14. DOI:10.1029/2008EO020001 |

| Vavrus S., Harrison S. P., 2003: The impact of sea-ice dynamics on the Arctic climate system. Climate Dyn., 20, 741–757. |

| Winton M., 2006: Amplified Arctic climate change: What does surface albedo feedback have to do with it?. Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, L03701. |

| Wu F., He J. H., Qi L., et al.,2014: The seasonal difference of Arctic warming and it’s mechanism under sea ice cover diminishing. Acta Oceanol. Sinica, 36, 39–47. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0253-4193.2014.03.005 |

| Zhang J. L., Rothrock D., Steele M., 2000: Recent changes in Arctic sea ice: The interplay between ice dynamics and thermodynamics. J. Climate, 13, 3099–3114. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(2000)013<3099:RCIASI>2.0.CO;2 |

| Zhang L., Li T., 2016: Relative roles of differential SST warming, uniform SST warming and land surface warming in determining the Walker circulation changes under global warming. Climate Dyn.. DOI:10.1007/s00382-016-3123-6 |

| Zhang X. D., Sorteberg A., Zhang J., et al.,2008: Recent radical shifts of atmospheric circulations and rapid changes in Arctic climate system. Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, L22701. DOI:10.1029/2008GL035607 |

2017, Vol. 31

2017, Vol. 31