The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- WU Hui, ZHAI Panmao, CHEN Yang . 2016.

- A Comprehensive Classification of Anomalous Circulation Patterns Responsible for Persistent Precipitation Extremes in South China. 2016.

- J. Meteor. Res., 30(4): 483-495

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-016-6008-z

Article History

- Received January 19, 2016

- in final form May 13, 2016

2. College of Atmospheric Sciences, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou 730000;

3. State Key Laboratory of Severe Weather, Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, Beijing 100081

Among the regions of China, South China experiences the greatest annual amounts of precipitation. Rainstorms are frequently recorded in this region during its long rainy season. During the flooding season in South China, persistent precipitation extremes (PPEs) are characterized by long duration, broad spatial coverage, and excessive accumulated precipitation amounts. As such, these highimpact events are capable of triggering severe floods, and further result in considerable losses to human life and property. For instance, during JuneJuly 1994, a severe flood caused by two largescale PPEs led to a direct economic loss of 54 billion RMB in Guangdong Province and Guangxi Region. Previous studies on the mechanisms involved in PPEs in South China have mainly focused on specific cases, with the preflood season being the primary concern. Pertinent results indicate that PPEs in South China during the preflood season are closely associated with multiple factors, including midhigh latitude circulation systems over the Eurasian continent (Wang et al., 2011) , the western Pacific subtropical high (WPSH) (Xu et al., 2007; Bao, 2008; Wang et al., 2009) , the South Asian high (Wang et al., 2007; Zhao and Wang, 2009) , upper-and lower-level jets (Sun et al., 2002; Ding et al., 2011; He et al., 2012) , and cold air from the Southern Hemisphere (Zhao et al., 2007) . PPEs in South China also show a link with the northward propagation of intraseasonal oscillations from tropical areas (Shi and Ding, 2000; Chen and Zhao, 2004; Lin et al., 2007) . Local topography is also believed to exert an influence on PPEs in South China (Sun et al., 2002; He and Li, 2013) . Lastly, studies revealed that PPEs in South China are affected by interactions among circulation systems of multiple scales; specifically, in the context of favorable largescale circulation systems, frequent mesoscale systems form, grow, and propagate toward key regions, enhancing local precipitation (Liu et al., 2005; Ni et al., 2006; Xia et al., 2006; Mu et al., 2008) .

Persistent highimpact weather events cannot be identified in model output, even by highly experienced forecasters (Root et al., 2007) . The identification and classification of the typical circulation patterns respon-sible for these high-impact weathers could make up for some of the deficiencies of model forecasts, and further provide some useful clues for forecasters (Grumm and Hart, 2001) . Accordingly, some recent studies have focused on the circulation patterns related to PPEs in South China. Xie et al. (2006) extracted two major patterns, characterized by a western blocking and an eastern blocking at 500 hPa at the midhigh latitudes, respectively. The concurrence between these longlived blockings and a “high in the east and low in the west” pattern at lower latitudes favors the formation of PPEs in South China. Lin et al. (2013) further reported that, apart from the traditionally recognized patterns of “three troughs sandwiched by two ridges” and “two ridges sandwiched by one trough”, another favorable pattern is characteristic of blocking patterns at higher latitudes and zonal circulation systems at midlatitudes. Based on investigation of moisture transport instability, ascent mechanism, and occurrence timing, Hu et al. (2007) categorized PPEs in South China into three types. In the two types during mid March to early May and mid May to mid July, ascent is triggered by lowlevel southwesterly jets; while the third type, during late July to early October, is associated with tropical cyclones (TCs) . Bao (2007) identified four major types of PPEs in China, including the BohaiLiaoxi type, meridional rainbelt type in northern China, frontal rainbelt type in southern China, and lowpressure type in South China. Among cases of the frontal rainbelt type in southern China, the front in South China mainly appears during the preflood season (MayJune) ; whereas, the lowpressure type in South China mostly occurs during the postflood season (JulySeptember) , and this type largely results from the landfalling of TCs in South China. Liu et al. (2014) argued that distinctive largescale circulation patterns prevail during PPEs in different decadal regimes.

The abovementioned studies have provided meaningful progress in deepening our understanding of the mechanisms involved in PPEs in South China. Nevertheless, a number of issues are worthy of further investigation. For instance, derived classifications of PPEs are casual and subjective to some extent, because of objective classification methods rarely being adopted. In addition, more attention has been paid to PPEs during the preflood season, and a simple TC type is insufficiently accurate to cover the diversity of mechanisms involved in PPEs during the postflood season. A considerable number of studies have emphasized largescale circulation patterns at a certain level, with less attention to the configurations among these systems at multiple vertical levels. However, there are concurrent anomalies of diverse systems at different levels that make the occurrence of PPEs, albeit with low probability, an extremely dangerous phenomenon (Müller et al., 2009) . It is therefore imperative to further investigate PPEs of different types and during different phases. Largescale circulation systems contribute most to PPEs by modulating synopticscale systems, advecting moisture from different sources and ultimately determining the occurrence region of extreme precipitation (Tao, 1980; Ding, 1994) . In this regard, by using observed daily precipitation in South China (Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, and Fujian) , this study firstly identifies PPEs during the whole flood season (AprilOctober) , via rigorous and objective criteria; then, an objective classification scheme is employed to classify the largescale circulation patterns responsible for PPEs; and finally, the configurations of planetaryscale systems among different levels and routes of moisture transport are elaborated. The results contribute to our understanding of different PPE types in South China. Moreover, the typical patterns and configurations identified in this work may provide a scientific grounding to extendedrange forecasts of PPEs in South China.

2 DataObserved daily precipitation data from 756 stations across China, obtained from the National Meteorological Information Center (NMIC) , are used. Before releasing these data, the NMIC performed rigorous quality control procedures. We select a total of 63 stations located to the south of 26°N— covering Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, and Fujian— to represent South China. The information on TCs is from the Shanghai Typhoon Institute, available online at http://tcdata.typhoon.gov.cn/. In addition, daily NCEPNCAR reanalysis data are used. These data have a horizontal resolution of 2.5°×2.5° and a vertical resolution of 17 levels (Kalnay et al., 1996) . The variables used in this study include geopotential height, horizontal wind, vertical velocity, specific humidity, and surface pressure. All the data span from 1951 to 2010.

3 Method 3.1 Definition of PPEsThere is no universal definition for PPEs currently. The one designed by Chen and Zhai (2013) is adopted in this study, because it can guarantee a high disastercausing capability of PPEs. Specifically, extreme precipitation (daily amount ≥ 50 mm) is required to persist for at least three days at each station (city) concerned; at least three stations are included for an event to ensure an appropriate influence in terms of spatial scale; and the durations for neighboring stations overlap by at least one day. Thus, the identified rainbelt remains quasistationary, rather than transient and sweeping across a large area (Tang et al., 2006; Ren et al., 2012) .

TCs can trigger PPEs in South China, and a substantial amount of studies have already focused on this topic. In contrast, the current study aims to investigate PPEs that are free from TC influence. To this end, those events influenced by TCs first need to be eliminated. Based on the TC information provided by the Shanghai Typhoon Institute, if a TC lingers around South China during a PPE, this PPE is considered as a TCinfluenced case. In addition, if a remote TC clearly advects moisture toward South China during a PPE, this PPE is also treated as a TCinfluenced event. Actually, the latter type is found to be quite rare; nevertheless, their exclusion, along with the former type of TCinfluenced events, leaves us a set of cases deemed to be nonTCinfluenced PPEs. In particular, double rainbelts are detected in South China and in the area immediately south of the Yangtze River during June in three years. Judged by the regions affected, the case during June 1994 is grouped into South China PPEs. In the following sections, classifications are performed with respect to these nonTCinfluenced PPEs during different seasons.

3.2 Analysis methodFirstly, a hierarchical cluster analysis is conducted to categorize the daily 700hPa zonal wind during PPEs. According to the experience of local fore-casters, key systems including midlatitude troughs, the WPSH, southwesterly monsoon, and the ITCZ, concentrate within the domain 10°-50°N, 70°-130°E. Therefore, when performing the cluster analysis, the similarity of circulation patterns within this domain should be a primary concern. The 700hPa zonal wind is selected as a key indicator because (1) at lower latitudes, precipitation is more sensitive to wind anomalies than to geopotential height anomalies, (2) the Tibetan Plateau impairs the reliability of 850hPa wind in the reanalysis data, and (3) zonal winds prevail at lower latitudes.

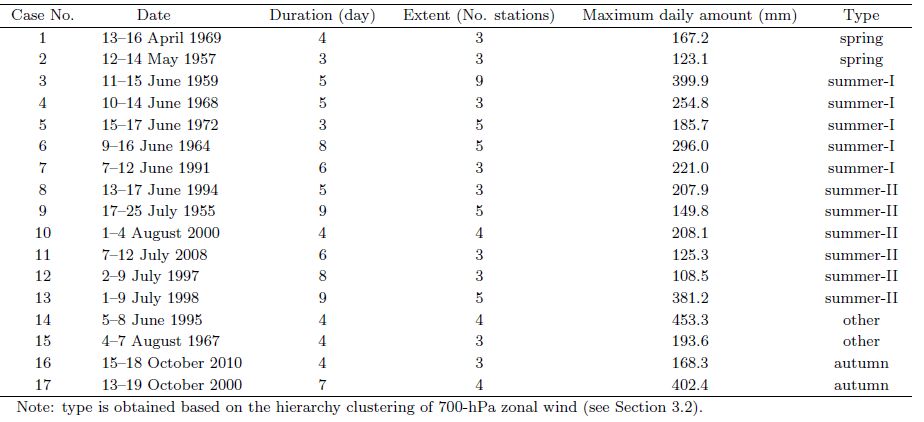

The hierarchical cluster analysis is performed as follows (Huang, 2000) . Each 700hPa zonal wind is taken as a sample and daily 700hPa zonal winds corresponding to all nonTCinfluenced PPE cases are collected. The Euclidean distance is then calculated and the distance metric is obtained. Each sample starts in its own cluster, and pairs of clusters with shortest distances are merged as one moves up the hierarchy. Based on the dendrogram for the summer PPE cases, when the distance between clusters is smaller than 18, the firstly combined 6 cases are classified as summerII type (see the last column in Table 1) , and the remaining 5 cases are classified as summerI type; for other nonsummer PPE cases, the firstly combined 2 cases with cluster distance smaller than 20 are grouped into autumn type, and the other 2 cases with cluster distance smaller than 22 are grouped into spring type (Table 1) .

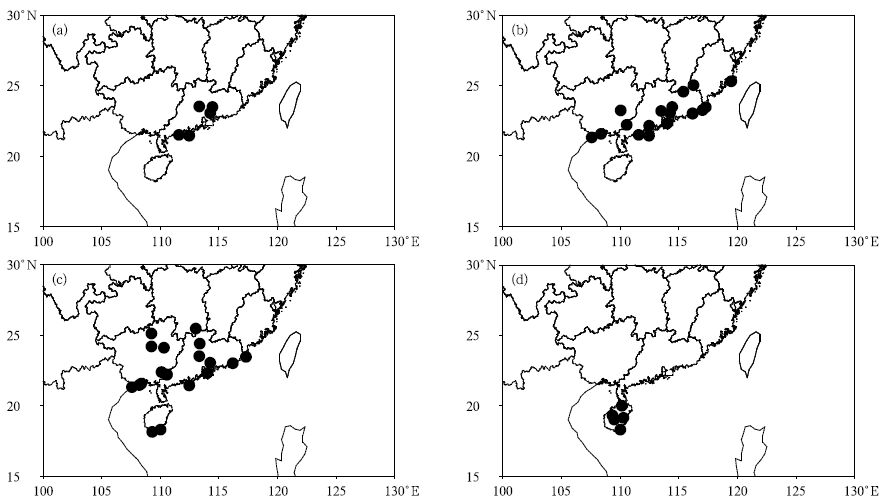

Anomalies of planetary systems at different levels are composited with respect to each type. Then, comparisons are made between the circulation patterns on PPE and nonPPE days. Key systems are confirmed through comprehensive consideration of the composited results, their comparisons, and in particular, the moisture transport anomalies. Finally, a conceptual model for each type is constructed. A nonPPE day refers to a day in a particular month upon which no PPE is recorded. The integrated moisture flux is calculated as follows:

|

(1) |

in which ps denotes the surface pressure and pt represents the top pressure of the atmosphere. In this study, pt is confined to 300 hPa because the reanalysis data only provide specific humidity below this level, and we believe that neglecting moisture fluxes above 300 hPa has little impact on the results (see Zhou, 2003) .

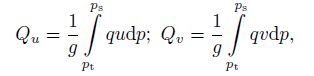

4 Seasonal distribution of PPEs in South ChinaA total of 44 PPEs are found to have occurred in South China during AprilOctober from 1951 to 2010, among which 17 are nonTCinfluenced PPEs, accounting for 38.6% of the overall number. These events cover AprilAugust and October. Occurrence peaks during June, at seven occurrences, while the number for July is four, and for both August and October is two. The number of TCinfluenced PPEs reaches 27, accounting for 61.4% of all cases. These TCinfluenced cases only appear after July, with their occurrence peaking in August (11 cases) ; September registers 8 TCinfluenced PPEs, and both July and October feature 4 (Fig. 1) . Obviously, during July in the postflood season, nonTCinfluenced PPEs account for a reasonably large percentage. August and October also register some nonTCinfluenced cases.

|

| Figure 1 Monthly frequency of PPEs across South China (1951-2010) . |

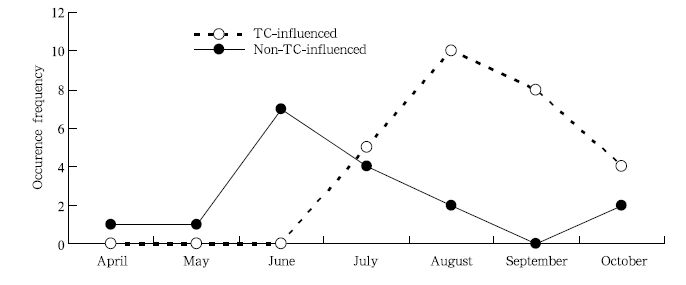

The initial cluster result indicates that each nonTCinfluenced case can be categorized into an individual cluster. Moreover, PPE types also show great dependence on the seasonal cycle. Cases occurring during different periods, i.e. AprilMay (spring) , JuneAugust (summer) , and October (autumn) , can be grouped into distinct types. In particular, two cases during AprilMay can be aggregated into one cluster; among 13 cases during JuneAugust, 11 cases can be classified into two types, with one containing five cases in June and the other including six cases during JuneAugust; the other two cases during October can be clustered into another independent type, as listed in Table 1. Meanwhile, the derived clusters generally reflect the seasonal march and spatial coverage of major rainbands. Specifically, cases during spring and autumn are characteristic of a narrower spatial scale and shorter duration. In contrast, PPEs during summer cover broader areas and last longer. From spring to summer, the major rainband extends from Guangzhou city to southeastern parts of Guangxi, and expands northward toward coastal areas of Fujian; during peak summer, the rainband advances northward toward northern Guangxi; and thereafter, it retreats southward to Hainan from late summer to autumn (Table 1 and Fig. 2) .

|

| Figure 2 Affected areas of different PPE types: (a) spring type, (b) summerI type, (c) summerII type, and (d) autumn type. |

Fewer PPEs occur during spring and autumn, so this study mainly investigates PPEs in summer.

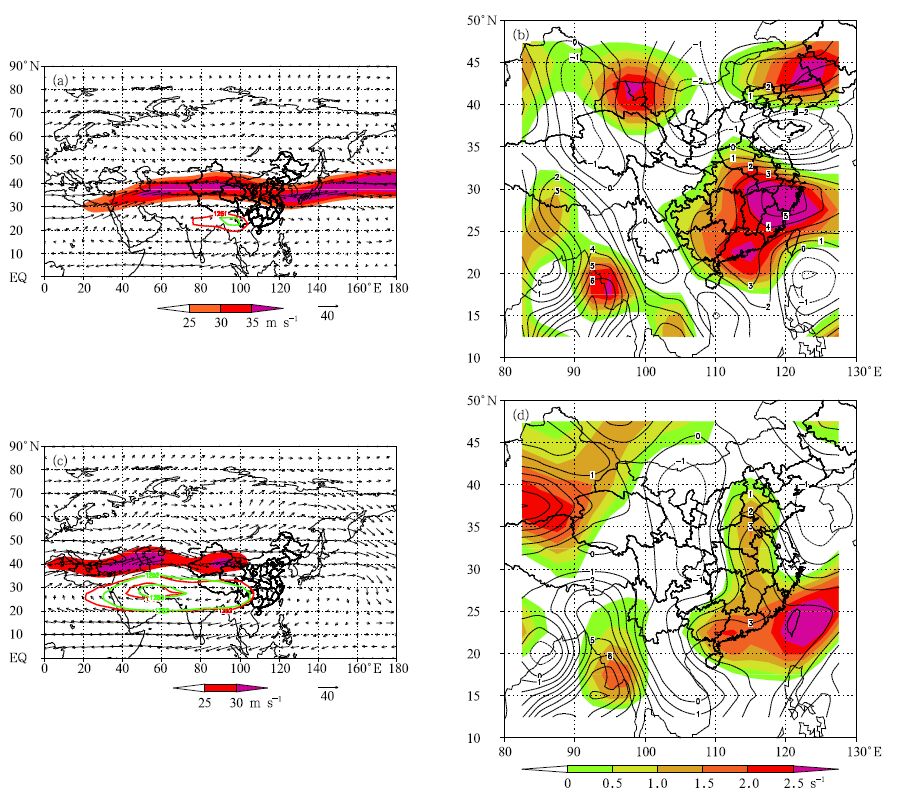

6.1 Upperlevel systemsThe South Asian high (SAH) and westerly jet are dominant planetaryscale systems at the upper levels. Activities of the SAH are delineated by its characteristic contour of 1252 dagpm (Zhang et al., 2010) , and the westerly jet is portrayed by zonal winds above 25 m s−1. As suggested by Zhang et al. (2015) , the SAH is termed the “westerncenter type” when the anticyclone center is located to the west of 90°E, and “easterncenter type” when located to the east; when the center is located around 90°E or multiple centers coexist, the SAH is referred to as a “belt type”.

For summerI type PPEs, the SAH behaves as the belt type. The westerly jet is quite strong, with its core speed above 35 m s−1 and its mean position near 35°N. The axis of the westerly jet orients northwestward in the upstream of South China, imposing a divergence area above southeastern China (Fig. 3a) . Compared with nonPPE circulation systems, the zonal extent covered by the 1251-dagpm contour during PPEs expands by 17° of longitude, and its easternmost point shifts eastward by 3° of longitude. The intensity of the SAH is slightly stronger during PPEs. In regions east of 120°E, the westerly jet is obviously stronger during PPEs, and the axis is northeasttilted. Thus, upperlevel divergent winds over eastern parts of South China are stronger (figure omitted) . Judged from the divergence field at 200 hPa, during PPEs of this type, positive divergence appears in eastern China, with maxima of 5.0 × 10−6 s−1 over South China (Fig. 3b) . In contrast, on nonPPE days, divergence above South China is very weak. Figure 3b presents the divergence difference between PPE and nonPPE days. Positive values are apparent over the whole of South China, with centers (> 2.5 × 10−6 s−1) located in coastal regions.

|

| Figure 3 Upperlevel (200 hPa) circulation patterns associated with different categories of PPEs: (a) summerI type; (c) summerII type (red and green solid contours denote geopotential height (dagpm) during PPE and nonPPE days, respectively; colorshading indicates the westerly jet (m s−1) ) . The divergence fields are presented in (b) summerI type and (d) summerII type, with contours representing divergence and colorshading the differences between the periods of PPE and nonPPE days. All values labeled on the divergence contours have been multiplied by 106 s−1. |

During summerII type PPEs, the SAH takes the form of the westerncenter type. The westerly jet is weaker than that during summerI type PPEs, with its core speed being about 32 m s−1 and its mean position located near 40°N. The jet axis is meandering, and the divergence zone is also located over South China (Fig. 3c) . Compared with nonPPE circulation systems, the zonal extent covered by the 1252dagpm contour during PPEs broadens by 12° of longitude, and its easternmost point shifts eastward by 2° of longitude. The intensity of the SAH is slightly stronger during PPEs. At 200 hPa, during PPEs, divergence over South China is greater than 2.0 × 10−6 s−1, and the maximum value reaches 4.0 × 10−6 s−1 (Fig. 3d) . In contrast, on nonPPE days, divergence over South China is less than 2.0 × 10−6 s−1 (figure omitted) . Larger difference values of divergence between PPE and nonPPE days are mainly concentrated in Guangdong and Guangxi, with the maximum value being above 2.0 × 10−6 s−1 (Fig. 3d) .

6.2 Midlevel systemsFor summerI type PPEs, two troughs dominate at 500 hPa at the midhigh latitudes, sandwiched by a weak ridge between them. The WPSH zonally elongates, with the westernmost point of the 586dagpm contour extending to the Indochina Peninsula. A deep trough is located near the Arabian Sea, and two shallow troughs reside over the Bay of Bengal (BOB) and coastal areas of western South China, respectively (Fig. 4a) . In contrast to the situation on nonPPE days, the trough near the Arabian Sea is deeper and the trough near the BOB shifts much farther north. The WPSH is stronger and extends farther west dur ing PPEs. The difference fields of geopotential height clearly reveal that lowpressure systems appear around northern South China, and highpressure systems are prevalent in southern South China. Correspondingly, smallscale disturbances migrate southward along the southern flange of the flat westerlies. Cold air steered by these disturbances facilitates the enhancement and persistence of extreme precipitation in South China. The northwarddisplaced trough around the BOB favors moisture transport toward eastern parts of South China. The shallow trough around western South China is conducive to the development of ascending motion.

|

| Figure 4 Differences in geopotential height at 500 hPa between PPE and nonPPE days for (a) summerI type and (b) summerII type events. Solid contours denote geopotential height during PPEs; colorshading indicates the difference in geopotential height (dagpm) . |

For summerII type PPEs, two ridges prevail at 500 hPa in the midhigh latitudes, sandwiched by a trough between them. The WPSH also takes the form of a zonally elongated belt, with its position displaced more southward and eastward relative to that during summerI type PPEs. The deep trough near the Arabian Sea expands to regions near the BOB, and a shallow trough establishes in northwestern parts of South China. Compared with the situation on nonPPE days, the trough from the Arabian Sea to the BOB is deeper during PPEs. Such a deepened trough is also evidenced by the cyclonic circulation around northern parts of the BOB (figure omitted) . The WPSH extends farther westward, and its ridge line is located southward. The intensity of the WPSH shows a contrasting pattern, with stronger parts in the north and weaker parts in the south (Fig. 4b) . The difference fields of geopotential height show that lowpressure systems are particularly conspicuous in South China and eastern China. In contrast, a highpressure system controls most regions south of Hainan Island (Fig. 4b) . Under such circumstances, southwesterlies tend to intensify near the Arabian Sea, the BOB, and northern parts of Indochina Peninsula, and then convey moisture toward Guangxi and Guangzhou city. The shallow trough near northwestern parts of South China is conducive to the triggering of strong ascending motion for PPEs.

The above comparison of the circulation systems prevalent on PPE and nonPPE days attaches great importance to specific combinations of largescale systems in triggering PPEs. Specifically, during summerI type PPEs, a much intensified trough near the BOB would inhibit the accumulation of moisture advected by southwesterlies; without the shallow trough near the western parts of South China, the ascending motion would become weaker; and given an eastwardretreated WPSH or further westward progressive WPSH, the moisture transport by southeasterlies would fail to reach South China. All of these unfavorable conditions would terminate PPEs in South China. During summerII type PPEs, a weakening or absence of the lowpressure system near the northern BOB could reduce moisture transport by southwesterlies; and without a trough (or lowpressure system) near northwestern parts of South China, the ascending motion would not be strong enough to support the persistence of PPEs.

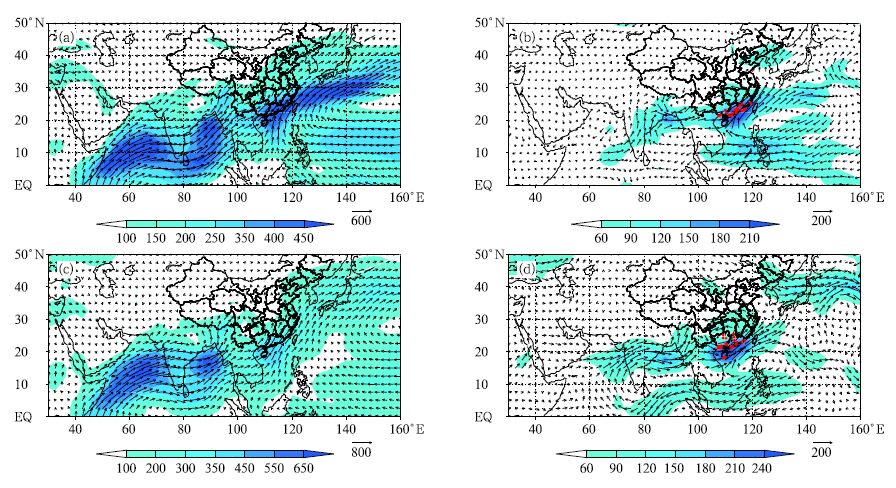

6.3 Moisture transportThe distinct features of moisture transport can be recognized through the integrated moisture fluxes during each PPE type. For summerI type PPEs, the moisture source, transport routes, and flux intensity differ significantly between PPE and nonPPE days. During PPEs, one branch is associated with the southwesterly monsoon, via the Arabian Sea and the BOB; the other branch originates from southeasterlies in the southern flange of the WPSH. These two branches converge in the south and then march toward coastal areas of eastern South China with abundant moisture (Fig. 5a) . On nonPPE days, southwesterlies play a dominant role in moisture transport, and moisture fluxes are evenly distributed across the whole South China. From the difference fields, the crossequatorial flows via the Somali jet intensify around southern parts of the Arabian Sea (10°N) and northern parts of the BOB (20°N) , contributing to enhanced moisture fluxes toward South China. Also enhanced is the moisture transport by southeasterlies in the southern flange of the WPSH. In contrast, the moisture transport conveyed by southwesterlies weakens in the region south of 10°N (Fig. 5b) . In summary, the enhanced south-westerlies to the north of 10°N and southeasterlies associated with the anomalous WPSH jointly determine the anomalous moisture transport during PPEs.

|

| Figure 5 Moisture transport on PPE days during (a) summerI and (c) summerII type PPEs and differences between PPE and nonPPE days during (b) summerI and (d) summerII type PPEs. Vectors represent integrated moisture fluxes (kg m−1s−1) ; colorshading in (a, c) highlights the fluxes above 100 kg m−1s−1 and in (b, d) highlights the fluxes above 60 kg m−1s−1 . Red dots in (b, d) denote the affected stations in every case. |

For summerII type PPEs, as displayed in Fig. 5c, identical moisture sources can be traced during PPE and nonPPE days, but the transport routes differ apparently. The major moisture transport route is associated with the southwesterly monsoon, via the Arabian Sea and the BOB; related moisture fluxes strengthen near the BOB, and then advance toward Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan. The other is the southerly transport route, which originates from the crossequatorial flows near 110°E. This branch is characterized by weaker moisture fluxes, and the moisture is largely advected toward coastal areas of Fujian and Taiwan. Enhanced transport is mainly detected in northern parts of the BOB, and this intensified southwesterly conveys abundant moisture toward South China. On nonPPE days, moisture fluxes are distributed evenly in the BOB, and the moisture is advected toward regions south of 10°N. The moisture transported by southeasterlies in the southern flange of the WPSH is mainly steered toward Japan. From the difference fields, it is clear that enhanced moisture fluxes extend from the northern Arabian Sea to southern parts of South China. Weakened fluxes appear in regions south of 10°N. The enhanced southeasterlies advect more moisture toward Taiwan (Fig. 5d) . The enhanced southwesterlies north of 10°N are the determining factor for anomalously abundant moisture during summerII type PPEs.

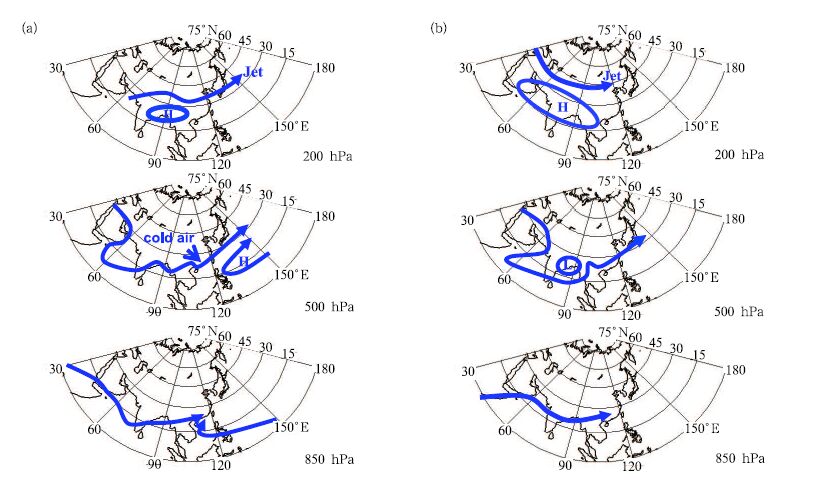

7 Conceptual model for each typeBased on the above analyses, conceptual models for PPEs in South China during JuneAugust are constructed, as presented in Fig. 6. For summerI type PPEs at 200 hPa, the SAH behaves as a belt type, with its ridge line around 35°N and its easternmost point around 103°E. The westerly jet orients northwestward, imposing strong divergence over eastern parts of South China. Zonally elongated westerly flow prevails at 500 hPa. Frequent cold air guided by smallscale disturbances penetrates southward along the southern edge of this westerly jet. The convergence between this cold/dry and warm/moist air from the south ultimately contributes to the occurrence of PPEs in South China. At the lower levels, a deep trough establishes around the Arabian Sea, and two shallow troughs appear in northern parts of the BOB and western parts of South China. These anomalous circulations at lower latitudes facilitate the accumulation of warm/moist air advected by southwesterlies in regions north of 10°N. Such warm/moist air is then conveyed toward coastal areas of South China. The strengthened WPSH extends westward significantly, resulting in more moisture being advected toward South China by southeasterlies from the southern flange (Fig. 6a) . For summerII type PPEs at 200 hPa, the SAH takes the form of the westerncenter type, with its ridge line around 40°N and its easternmost point around 106°E. At 500 hPa, a deep trough resides over the regions from the Arabian Sea to the BOB, and a shallow trough prevails over southwestern parts of South China. These anomalous circulation systems favor the intensification of southwesterlies in the northern flank. Enhanced southwesterlies advect abundant moisture toward Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan (Fig. 6b) .

|

| Figure 6 Schematic representation of PPEs in South China: (a) summerI type and (b) summerII type. “H” and “L” indicate the locations of high (ridge) and low (trough) systems, respectively. At 200 hPa, solid lines represent geopotential height contours and arrows represent locations of the jet axis. At 500 hPa, solid lines with arrowheads stand for streamlines. At 850 hPa, solid lines with arrowheads represent anomalous moisture transport paths. |

Obviously, the configurations of circulation systems for PPEs in South China differ significantly from those for PPEs in the YangtzeHuai River valley (Chen and Zhai, 2014) . Two typical patterns are deemed responsible for PPEs in the YangtzeHuai River valley. One is composed of Ural blockings, Okhotsk blockings, and the WPSH, and its influence areas are confined to northern parts of the YangtzeHuai River valley. The other consists of Baikal blocking and the WPSH, and extreme precipitation in this type largely falls in southeastern parts of the Yangtze River region. For both types in the YangtzeHuai River valley, the anomalously abundant moisture is advected by southeasterlies from the southern flange of the westwardextended WPSH (Chen and Zhai, 2014) .

8 Conclusions and discussionBased on an objective classification method, this paper categorizes the typical circulation patterns responsible for nonTCinfluenced PPEs in South China during AprilOctober. Configurations among planetaryscale systems at different levels for each type are confirmed, and sources of anomalously abundant moisture for each type are diagnosed. The main conclusions can be summarized as follows.

(1) NonTCinfluenced PPEs account for about 38.6% of total events in South China. These events appear during AprilAugust and October, with occurrence peaking in June. TCinfluenced PPEs account for about 61.4%, and their occurrence timing spans from July to October, peaking in August.

(2) The circulation systems prevalent during nonTCinfluenced PPEs can be classified into three types, i.e., summerI type, summerII type, and autumn type. The summerI and summerII types are most common, and their typical circulation patterns differ from one another. During summerI type PPEs, the SAH behaves as a belt type. The upstream westerly jet tilts northwestward slightly. Zonally elongated westerly flow prevails at the middle levels. Frequent cold air, guided by smallscale disturbances, penetrates southward along the southern edge of this westerly jet. At the lower levels, a deep trough establishes to the north of the Arabian Sea, and a shallow trough appears over western parts of South China. The WPSH extends westward significantly, shifts southward, and strengthens obviously. For summerII type PPEs, the SAH takes the form of a westerncenter type. At the middle levels, the deep trough in the Arabian Sea is accompanied by an anomalous cyclone. A shallow trough occupies southwestern parts of South China. It is the abovedescribed set of combinations of each type that triggers PPEs in South China.

(3) Sources of anomalous moisture vary with PPE type. The moisture for summerI type PPEs is contributed by horizontal advection via southwesterlies near 20°N and southeasterly transport from the southern flange of the WPSH. The anomalous moisture flux maximizes in coastal areas of eastern South China. Whereas, during summerII type PPEs, the southwesterly transport near 20°N is the only responsible branch, and the maximum moisture flux anomalies appear in Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan.

A number of studies on typical cases have revealed obvious lowfrequency oscillations during extreme precipitation in South China (Gu and Zhang, 2012; Jian and Zhang, 2013; Hu et al., 2014) . Therefore, the behavior of lowfrequency agents in each identified PPE type is worth investigating. Whether or not lowfrequency oscillations vary with PPE type remains an open question. Of particular note is that most cases of summerI type PPEs are found to have occurred before the 1990s, whereas summerII type PPEs are more common after the 1990s. Such obvious decadal variations of PPE occurrence may be associated with regime shifts in some key circulation factors. In spite of their different study period and definitions, Lin et al. (2013) also reported similar decadal variations of PPEs during the preflood season, attributing such decadal changes to decadal transitions of circulation systems at lowermid latitudes over East Asia. Similarly, Liu et al. (2014) also found different features of largescale circulation during two individual regimes with frequent PPEs in South China (1964-1972 and 1991-2010) .

| Bao Min. ,2007: Statistical analysis of the persistent heavy rain in the last 50 years over China and their background large-scale circulation. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci. , 31 , 779–792. |

| Bao Min. ,2008: Comparison of the effects of anomalous convective activities in the tropical western Pacific on two persistent heavy rain events in South China. J. Trop. Meteor. , 24 , 27–36. |

| Chen Hong, Zhao Sixiong. ,2004: Heavy rainfalls in South China and related circulation during HUAMEX period. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci. , 28 , 32–47. |

| Chen Y, P. M. Zhai. ,2013: Persistent extreme precipitation events in China during 1951-2010. Climate Res. , 57 , 143–155. DOI:10.3354/cr01171 |

| Chen Y, P. M. Zhai. ,2014: Two types of typical circulation patterns for the persistent extreme precipitation in central-eastern China. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. , 140 , 1467–1478. DOI:10.1002/qj.2231 |

| Ding Yihui. ,1994: Some aspects of rainstorm and mesoscale meteorology. Acta Meteor. Sinica , 52 , 274–284. |

| Ding Zhiying, Liu Caihong, Shen Xinyong. ,2011: Statistical analysis of the relationship among warm sector heavy rainfall, upper and lower tropospheric jet stream and South Asian high in May and June from 2005 to 2008. J. Trop. Meteor. , 27 , 307–316. |

| Grumm, R. H, R. Hart. ,2001: Standardized anomalies applied to significant cold season weather events: Preliminary findings. Wea. Forecasting , 16 , 736–754. DOI:10.1175/1520-0434(2001)016<0736:SAATSC>2.0.CO;2 |

| Gu Dejun, Zhang Wei. ,2012: The strong dragon boat race precipitation of Guangdong in 2008 and quasi-10-day oscillation. J. Trop. Meteor. , 18 , 349–359. |

| He Bian, Sun Zhaobo, Li Zhongxian. ,2012: Dynamic diagnosis and numerical simulation of a persistent torrential rain case in South China. Trans. Atmos. Sci. , 35 , 466–476. |

| He Yu, Li Guoping. ,2013: Numerical experiments on influence of Tibetan Plateau on persistent heavy rain in South China. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci. , 37 , 933–944. |

| Hu Liang, He Jinhai, Gao Shouting. ,2007: An analysis of large-scale condition for persistent heavy rain in South China. J. Nanjing Inst. Meteor. , 30 , 345–351. |

| Hu Yamin, Zhai Panmao, Luo Xiaoling, et al. ,2014: Large-scale circulation and low frequency signal characteristics for the persistent extreme precipitation in the first rainy season over South China in 2013. Acta Meteor. Sinica , 72 , 465–477. DOI:10.11676/qxxb2014.024. |

| Huang Jiayou. ,2000: Meteorological Statistics Analysis and Predictive Method. China Meteorological Press, Beijing , 181 , 181–191. |

| Jian Maoqiu, Zhang Chunhua. ,2013: Impact of quasibiweekly oscillation on a sustained rainstorm in October 2010 in Hainan. J. Trop. Meteor. , 29 , 364–373. |

| Kalnay E, M. Kanamitsu, R. Kistler, et al. ,1996: The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. , 77 , 437–471. DOI:10.1175/1520-0477(1996)077<0437:TNYRP>2.0.CO;2 |

| Lin Ailan, Liang Jianyin, Li Chunhui, et al. ,2007: Monsoon circulation background of ‘0506’ continuous rainstorm in South China. Adv. Water Sci. , 18 , 424–432. |

| Lin Ailan, Li Chunhui, Zheng Bin, et al. ,2013: Variation characteristics of sustained torrential rain during the pre-flooding season in Guangdong and associated circulation pattern. Acta Meteor. Sinica , 71 , 628–642. DOI:10.11676/qxxb2013.063. |

| Liu Yanju, Ding Yihui, Zhao Nan. ,2005: A study on the mesoscale convective systems during sum-mer monsoon onset over South China Sea in 1998. I: Analysis of large-scale fields for occurrence and development of mesoscale convective systems. Acta Meteor. Sinica , 63 , 431–442. |

| Liu Lei, Sun Ying, Zhang Pengbo. ,2014: The influence of decadal change of the large-scale circulation on persistent torrential precipitation over South China in early summer. Acta Meteor. Sinica , 72 , 690–702. DOI:10.11676/qxxb2014.031. |

| Mu Jianli, Wang Jianjie, Li Zechun. ,2008: A study of environment and mesoscale convective systems of continuous heavy rainfall in South China in June 2005. Acta Meteor. Sinica , 66 , 437–451. |

| Müller M, M. Kašpar, D. Řezáčová, et al. ,2009: Ex-tremeness of meteorological variables as an indicator of extreme precipitation events. Atmos. Res. , 92 , 308–317. DOI:10.1016/j.atmosres.2009.01.010 |

| Ni Yunqi, Zhou Xiuji, Zhang Renhe, et al. ,2006: Experiments and studies for heavy rainfall in southern China. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci. , 17 , 690–704. |

| Ren F. M, D. L. Cui, Z. Q. Gong, et al. ,2012: An objective identification technique for regional extreme events. J. Climate , 25 , 7015–7027. DOI:10.1175/JCLI-D-11-00489.1 |

| Root B, P. Knight, G. Young, et al. ,2007: A fingerprinting technique for major weather events. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol. , 46 , 1053–1066. DOI:10.1175/JAM2509.1 |

| Shi Xueli, Ding Yihui. ,2000: A study on extensive heavy rain processes in South China and the summer monsoon activity in 1994. Acta Meteor. Sinica , 58 , 666–678. |

| Sun Jian, Zhao Ping, Zhou Xiuji. ,2002: The mesoscale structure of a South China rainstorm and the influence of complex topography. Acta Meteor. Sinica , 60 , 333–342. |

| Tang Yanbing, Gan Jingjing, Zhao Lu, et al. ,2006: On the climatology of persistent heavy rainfall events in China. Adv. Atmos. Sci. , 23 , 678–692. DOI:10.1007/s00376-006-0678-x |

| Tao Shiyan. ,1980: Torrential Rain in China , 35–36. |

| Wang Lijuan, Guan Zhaoyong, He Jinhai. ,2007: Features of the large-scale circulation for flash-floodproducing rainstorm over South China in June 2005 and its possible cause. J. Nanjing Inst. Meteor. , 30 , 145–152. |

| Wang Lijuan, Chen Xuan, Guan Zhaoyong, et al. ,2009: Features of the short-team position variation of the western Pacific subtropical high during the torrential rain causing severe floods in southern China and its possible cause. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci. , 33 , 1047–1057. |

| Wang Donghai, Xia Rudi, Liu Ying. ,2011: A preliminary study of the flood-causing rainstorm during the first rainy season in South China in 2008. Acta Meteor. Sinica , 69 , 137–148. |

| Xia Rudi, Zhao Sixiong, Sun Jianhua. ,2006: A study of circumstances of meso-β-scale systems of strong heavy rainfall in warm sector ahead of fronts in South China. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci. , 30 , 988–1008. |

| Xie Jiongguang, Ji Zhongping, Gu Dejun, et al. ,2006: The climatic background and medium range circulation features of continuous torrential rain from April to June in Guangdong. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci. , 17 , 354–362. |

| Xu Xiaolin, Xu Haiming, Si Dong. ,2007: Relationship between June sustained torrential rain in South China and anomalous convection over the Bay of Bengal. J. Nanjing Inst. Meteor. , 30 , 463–471. |

| Zhang Bo, Zhou Xiuji, Chen Longxun, et al. ,2010: An East Asian land-sea atmospheric heat source difference index and its relation to general circulation and summer rainfall over China. Sci. China (Ser. D) , 53 , 1734–1746. DOI:10.1007/s11430-010-4024-x |

| Zhang Duanyu, Zheng Bin, Wang Xiaokang, et al. ,2015: Preliminary research on circulation patterns in the persistent heavy rain processes during the first rainy season in South China. Trans. Atmos. Sci. , 38 , 310–320. DOI:10.13878/j.cnki.dqkxxb.20130520002. |

| Zhao Yuchun, Li Zechun, Xiao Ziniu. ,2007: A case study on the effects of cold air from the Southern Hemisphere on the continuous heavy rains in South China. Meteor. Mon. , 33 , 40–47. |

| Zhao Yuchun, Wang Yehong. ,2009: A review of studies on torrential rain during pre-summer flood season in South China since the 1980s. Torrential Rain and Disasters , 28 , 193–202. |

| Zhou T. J. ,2003: Comparison of the global air-sea freshwater exchange evaluated from independent datasets. Progress in Natural Science , 13 , 626–631. DOI:10.1080/10020070312331344150 |

2016, Vol. 30

2016, Vol. 30