The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- LI Jun, WANG Pei, HAN Hyojin, LI Jinlong, ZHENG Jing. 2016.

- On the Assimilation of Satellite Sounder Data in Cloudy Skies in Numerical Weather Prediction Models

- J. Meteor. Res., 30(2): 169-182

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-016-5114-2

Article History

- Received December 15, 2015

- in final form February 16, 2016

2 Department of Atmospheric & Oceanic Sciences, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1225 West Dayton Street, Madison, WI 53706, USA;

3 National Satellite Meteorological Center, China Meteorological Administration, Beijing 100081, China

Society has long desired to accurately forecast the weather. For a successful accurate weather forecast,Bjerknes(1911)outlined two conditions:(1)the present state of the atmosphere(or the analysis fields)must be characterized as accurately as possible; and (2)the intrinsic laws,according to which the subsequent states develop out of the preceding ones,must be known. The basic atmospheric motion equations and basic conservation laws are the components of the theoretical support for the atmospheric intrinsic laws. Based on these equations and laws,the current global and regional numerical weather prediction models have successfully produced weather forecasts. However,improving the accuracy of the present state of the atmosphere is still a challenge for the research community and the operational centers.

Data assimilation uses both observations and short-term forecasts to estimate the initial conditions(Kalnay,2003). In the modern numerical weather prediction(NWP),both traditional observations and satellite observations can be assimilated in the system, and provide useful atmospheric initial condition information for improving the weather forecasts. Traditional measurements from the surface and radiosonde used in forecasting include the SYNOP(for l and surface observations),SHIP(for sea surface observations), and TEMP(for upper air observations)(Daley,1991). The satellite measurement is an impor-tant type of global observation in support of NWP. Because most traditional observations are over populated l and regions,satellite observations compensate for those areas where traditional observations are limited or rare,such as over oceans and the Southern Hemisphere. High-temporal resolution is another advantage of satellite observations. Even over l and ,satellite observations are able to fill the gaps between the radiosonde locations and their launch times. Based on recent studies,contributions from satellite data,especially data from infrared(IR) and microwave(MW)sounders such as Atmospheric Infrared Sounder(AIRS),Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer(IASI),Crosstrack Infrared Sounder(CrIS),Advanced Microwave Sounding Unit-A(AMSU-A),AMSU-B,Microwave Humidity Sounder(MHS),etc.,are becoming the most important observations in operational centers(Le Marshall et al., 2005,2006; Kelly and Thepaut, 2007; Cardinali,2009). MW and IR sounders have the most impact on forecast skills in all satellite observations(Garand et al., 2013; Joo et al., 2013; Cucurull et al., 2014). McNally et al.(2014)found that the polar-orbiting satellite data play an important role in decreasing the time and location errors of Hurricane Sandy’s track forecasts.

To date,the assimilation of satellite data is mostly under clear skies only,especially for IR sounder data. Since many satellite IR sounders measure both atmospheric profiles and clouds,the data impact of the IR observations mainly comes from the clear observations(not affected by clouds)at most operational centers. However,the clear IR observations constitute only a small portion of the total IR observations. The percentage of completely clear-sky observations from the High-Resolution Infrared Radiation Sounder(HIRS)is around 25%(Wylie et al., 1994), and the percentage of AIRS is less than 10%(Huang and Smith, 2004). Therefore,the percentage of IR observations that can be assimilated in the operational system is as few as 5% of the total observations(McNally and Watts, 2003). Some operational centers,such as the ECMWF and Met Office,begin to assimilate the cloud-affected radiance(Pavelin et al., 2008; McNally,2009),which is a big improvement in satellite data assimilation and will be discussed in details in the following sections. Because MW observations can penetrate non-precipitating clouds,MW sounder data are less affected by clouds. However,MW is sensitive to the surface emissivity and similar optical properties of cloud water and precipitation. As a result,the MW sounders with high cloud optical depth and the surface sensitive channels over l and are removed from the NWP systems in many operational centers.

According to McNally(2002),the cloudy regions are the forecast sensitive areas,such that,how to use the information from the cloudy regions is a challenging but important task for data assimilation. To assimilate the cloud-affected satellite observations directly,the important components of the NWP and radiative transfer model(RTM)need to adjust accordingly under cloudy regions,i.e.,the physical parameterization,the RTM, and the observation errors(Geer et al., 2011). The lack of underst and ing about the vertical structure of cloud parameters from the observations, and the uncertainties of the nonlinearity of the moist physics process,make direct assimilation of cloud-affected radiances very difficult(Errico et al., 2007).

In this paper,methods to assimilate the cloudaffected satellite observations and their impacts are reviewed,while the potential problems of each method are further discussed. The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the challenges to assimilating IR sounder radiances in cloudy skies; Section 3 introduces the methodologies for assimilating IR radiances in cloudy skies,including clear channel detection,clear location detection, and cloud-clearing methods; Section 4 describes the cloud-screening for MW sounder radiances for assimilation; Section 5 discusses the retrieved products assimilated in the system; methods for assimilating cloud-affected radiances are in Section 6; and the summary and discussion are given in Section 7.

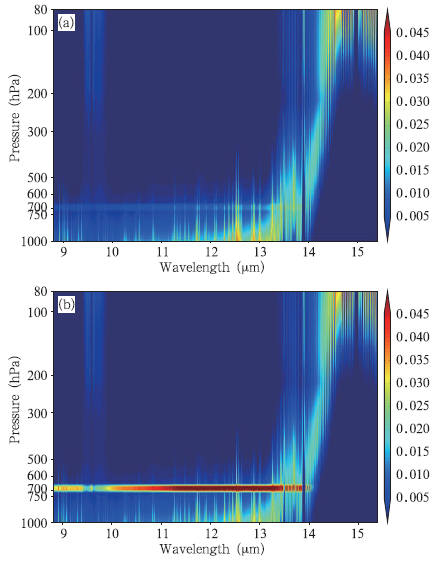

2. Challenges to assimilating IR sounder radiances in cloudy skiesFor IR sounders,direct assimilation of radiances is particular challenging because(1)both NWP and RTM have larger uncertainties in cloudy regions,(2)there is a significant change in the temperature Jacobians at cloud level, and (3)satellite observations and NWP may be inconsistent on clouds(e.g.,satellite sees clouds but NWP does not,vice versa). Figure 1 shows the AIRS temperature Jacobian(dBT/dT; K K−1)using the Community Radiative Transfer Model(CRTM)with a cloud-top pressure(CTP)of 700 hPa, and cloud optical thickness(COT)at 0.55 μm in Figs. 1a and 1b,respectively. It can be seen that when the cloud is thin,the temperature Jacobians are quite smooth vertically while when the cloud is thicker,there is a large temperature Jacobian change at cloud level,making the assimilation of temperature information from radiances very difficult in cloudy skies. Another challenge is the higher nonlinearity in assimilation when clouds present(Bauer et al., 2011a).

|

| Fig. 1. AIRS temperature Jacobian (dBT/dT; K K−1) with a cloud-top pressure (CTP) of 700 hPa, and cloud optical thickness (COT) at 0.55 μm of (a) 0.05 and (b) 0.5, respectively. |

Currently there are four methodologies for IR sounder radiance assimilation in cloudy regions:(1)the first method is hole hunting,which is to find clear fields-of-view(FOV)so that radiances in clear FOVs can be assimilated. The advantage of this method is that radiance assimilation in clear skies is quite mature and the RTM in clear skies is also reliable; the disadvantage is that only a small percentage of the data is used.(2)The second method is clear channel detection. This method is used to find radiances of those channels not affected by clouds,for example,choosing radiances in those channels with weighting function,or Jacobian(dBT/dT)peaks above the clouds. The advantage of this method is that more data are used in radiance assimilation,especially some data are used in cloudy skies(e.g.,in low cloud situations); the disadvantage is that the channels with weighting peaks above the cloud top can still be partially contaminated by clouds.(3)The third methodology is direct assimilation of radiances in cloudy skies,which is quite challenging as discussed above.(4)The fourth methodology is to use cloud-cleared radiances instead; this method removes the cloud effect in IR FOV(s)by using additional information in cloudy skies and obtaining the clear equivalent radiances or so-called cloudcleared radiances(CCRs),so that the CCRs can be treated as clear radiances in assimilation. The advantage of this method is that the CCRs can be assimilated as clear radiances in cloudy skies; the disadvantage is that additional information is needed and the CCR observation errors are amplified compared to the clear sky radiances.

3.1 Clear channel radiance detectionTo date,in many operational centers,the cloud contribution from the satellite sounders is neglected. Consequently,the core parts of the assimilation algorithm,or more broadly the data assimilation system(DAS)(i.e.,the control vectors,the RTM,the background error covariance,the observation error covariance, and the linearized physical parameters)are designed for clear radiance assimilation. If the cloudy radiances are assimilated as clear radiances,the quality of NWP analysis will be negatively impacted(Pangaud et al., 2009; Eresmaa,2014). Therefore,reliable clear radiance detection(channels not affected by clouds)is important before the satellite data assimilation.

The major method for clear radiance detection in most systems is to calculate the first guess departures(i.e.,by comparing the observed and the simulated brightness temperature calculated through the forward model from the background). If the firstguess departures are larger than the threshold,then the observations are rejected as cloudy. Therefore,this approach requires very accurate atmospheric temperature analysis,as well as accurate simulated clouds from the first-guess departure. The NWP model can capture the large-scale clouds well. The deep convective clouds are detected and removed due to the large first-guess departure. However,for thin clouds or under partially cloudy regions,the difference in radiances between the clouds and the clear skies is small. For the low clouds where the temperature contrast from the surface is small,the first-guess departures are potential within the threshold value. In these regions,if the first-guess departure is smaller than the threshold,the observed cloudy radiances are assimilated as clear sky in the NWP model,which introduces cloud contamination and degrades the analysis fields. In addition,in the case of clear observations from satellite while NWP has clouds,the clear observations will be discarded in the assimilation based on the first-guess departure.

3.2 Clear location detection for IR soundersIn order to better assimilate radiances in cloudy skies,another important step could be clear location detection. The radiance assimilation in cloudy regions can be built on clear location detection,for example,using radiances from all available channels in clear FOVs while finding clear channel radiances or obtaining CCRs in cloudy skies based on the clear location detection. A new cloud detection method uses collocated high spatial resolution imager data(i.e.,Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer(MODIS))onboard the same platform as the satellite sounders to help IR sounders(i.e.,AIRS)sub-pixel cloud detection(Li et al., 2004). The MODIS cloud mask provides a level of confidence for the observed skies as confident clear,probably clear,probably cloudy, and confident cloudy(Ackerman et al., 1998). The AIRS sub-pixels with confident clear from the MODIS cloud mask are kept as clear observations; otherwise,the AIRS subpixels are rejected as cloudy. AIRS cloud detection using the collocated MODIS cloud mask removes the cloud FOVs,which reduces cloud contamination and improves the assimilation. By reducing the cloud contamination,a cold bias in the temperature field and a wet bias in the moisture field are corrected for the atmospheric analysis fields. These less cloud affected analysis fields further improve hurricane track and intensity forecasts(Wang et al., 2014).

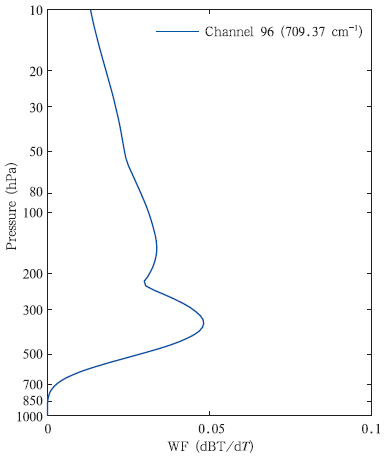

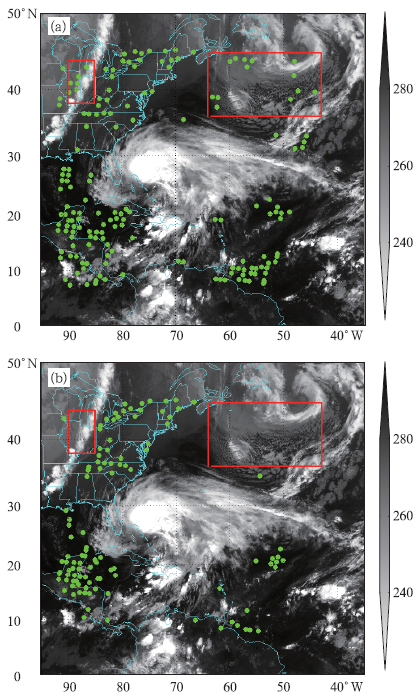

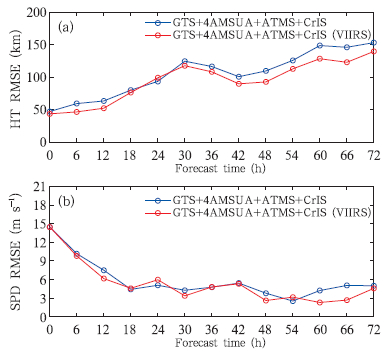

This method can be employed to process observations from the CrIS/Visble Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite(VIIRS)onboard the Suomi-National Polar orbiting satellite Partnership(SNPP)/Joint Polar Satellite System(JPSS). Figure 2 gives the weighting function(or Jacobian)for CrIS channel 96(709.37 cm−1). The weighting function peak for this channel is around 350–400 hPa. Figure 3 shows the CrIS radiance assimilation in Gridpoint Statistical Interpolation(GSI)with st and -alone cloud detection(Fig. 3a,green dots) and with VIIRS cloud detection(Fig. 3b,green dots),respectively,for CrIS channel 96. The GSI st and -alone cloud detection is based on the comparison of the weighting functions to a cloud height retrieved via a minimum residual method(Eyre and Menzel, 1989). To identify the cloud contamination,the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites(GOES-13)Imager brightness temperature(BT)at 10.7 is collocated in this region. It can be seen that the st and -alone cloud detection method assimilated some CrIS data affected by clouds as clear radiances(the boxes in Fig. 3). With the collocated VIIRS high spatial resolution cloud mask for CrIS clear detection,the cloud affected radiances are removed before radiance assimilation,which avoids degrading the analysis fields. Since CrIS and VIIRS are onboard the operational satellite,this method could be used in operations. The forecast results with VIIRS for CrIS clear location detection are shown in Fig. 4; the details of the experiments can be found in Wang et al.(2014). The clear radiances are in the region surrounding the hurricanes,which have more impacts for the surrounding thermodynamic fields. Compared with GSI st and -alone cloud detection,the hurricane track root mean square error(RMSE)is reduced in the 72-h forecasts. The RMSE of maximum wind speed(SPD)is comparable in this study case.

|

| Fig. 2. The weighting function (WF) of CrIS channel 96 (709.37 cm−1). |

|

| Fig. 3. The locations at 0600 UTC 26 October 2012 where CrIS channel 96 (709.37 cm−1) is flagged clear with (a) stand-alone cloud detection and (b) VIIRS cloud detection on visible imagery (10.7 μm) from GOES-13 for Hurricane Sandy (2012). |

|

| Fig. 4. (a) The track (HT) and (b) the maximum wind speed (SPD) forecast RMSE with CrIS stand-alone cloud detection (blue) and CrIS/VIIRS cloud detection (red). Data are assimilated every 6 hours from 0600 UTC 25 to 0000 UTC 27 October 2012, followed by a 72-h forecast for Hurricane Sandy (2012). |

Using collocated high spatial resolution imager data to help the satellite sounder cloud detection is already implemented in the operational system at ECMWF,for example,using the Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer(AVHRR)for IASI sub-pixel cloud characterization. Both instruments are onboard Europe’s operational Metop satellite series. Applying the imager cloud flag in data assimilation makes the lower troposphere warmer and drier, and reduces the amount of ozone in the stratosphere. The global forecasts also show improvement when applying the new cloud detection method(Eresmaa,2014).

3.3 Cloud-cleared radiances(CCRs)for assimilationGood cloud detection could effectively remove the cloud contamination and keep the clear observations for assimilation. However,the availability of satellite observations that can be assimilated in the model is limited if only the clear radiances are assimilated. An effective way to use the thermodynamic information under partially cloudy regions is to assimilate the CCRs or cloud-removed radiances(Smith,1968; Smith et al., 2004); CCRs are also called clear equivalent radiances. Obtaining CCRs requires additional information beyond IR cloudy radiances.

Based on difference sources of additional information,three cloud-clearing methods have been developed. The first method,called the background based cloud-clearing method,is based on the background or first-guess fields. The cloud-cleared CrIS radiances based on the background cloud-clearing method are assimilated at the NCEP for research(Liu et al., 2015). The advantage of this method is that it is easy to implement into the operational systems. But the cloudcleared information is only based on the background or the first-guess fields,which generate considerable risk if the forecasts used as the background in cloudy regions have large uncertainties. The second method is using theMW(i.e.,AMSU-A)data to help the IR(i.e.,AIRS)obtain cloud-cleared IR radiances(Susskind et al., 2003). Usually MW sounders have relatively coarse spatial resolution(i.e.,45 km for AMSU-A at nadir)compared to IR sounders(i.e.,13.5 km for AIRS at nadir); as a result,the cloud-cleared IR sounders are degraded from the higher spatial resolution to the coarse spatial resolution of the MW sounders. The third cloud-clearing method uses high spatial resolution imager data(i.e.,MODIS)to help the IR(i.e.,AIRS)obtain cloud-cleared IR radiances under partially cloudy regions(Li et al., 2005). It removes the cloud effect from an IR sounder FOV with partial cloud cover by using collocated clear sky imager IR radiances. For example,by spatially averaging MODIS IR radiances into an AIRS FOV, and spectrally averaging AIRS into MODIS spectral b and s,an important cloud-clearing parameter called N* can be calculated,by applying N* to the whole AIRS radiance spectrum,AIRS cloud-cleared radiances on a single FOV basis can be obtained for radiance assimilation in NWP. The advantage of this method is that it keeps the original high spatial resolution of the IR data(i.e.,13.5 km at nadir for AIRS cloud-cleared radiances).

Because the cloud-clearing method obtains the equivalent clear radiances from the partially cloudy FOVs,the CCRs can be directly assimilated as clear observations in the current NWP models without modifications. Thus,the assimilation of CCRs is an alternative way to assimilate the thermodynamic and hydrometric information under partially cloudy regions. Rienecker et al.(2008)showed that an additional 21% of the AIRS FOVs can be successfully cloud cleared,which provides much more data than with the clear FOVs only. In the global model,assimilating cloudcleared AIRS data provides information in the troposphere and positive impacts for both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. In the regional model,the cloud-cleared AIRS radiances are assimilated for hurricane forecasts(Wang et al., 2015). The impacts of the cloud-cleared radiance assimilation are becoming more obvious with extended forecasts. The forecast error of the temperature fields and the RMSE of the hurricane track are smaller with assimilating cloud-cleared radiances than with assimilating clear radiances only. However,the impact on hurricane intensity forecast is neutral.

Although cloud-cleared radiances can improve the yield of radiance assimilation,for example,exp and ing the radiance assimilation to partly cloud cover,there are still some limitations that need to be considered. First,the cloud-cleared radiances have amplified instrument noise depending on the cloudiness of the FOV to be cloud-cleared, and usually this can be taken into account by increasing the observation error in radiance assimilation; Second,atmospheric temperature and moisture might have inhomogeneity in the partly FOV,especially for moisture since the moisture in clear portion and cloudy portion within one subpixel might be different; Third,the correlated errors both spectrally and spatially should be represented in assimilation but are difficult to quantify.

4. Cloud-screening for MW soundersHigh spatial resolution imager data(i.e.,MODIS)could also help MW satellite sounders(i.e.,AMSU-A)obtain reliable cloud detection. For MW sounders,the sub-pixel cloud detection method is different from the IR. The cloud characteristics seen by the IR sounder are usually the same seen by the imager,especially IR b and s of an imager. Thus,it is much more straightforward to collocate the imager data for IR sounder sub-pixel cloud characterization. MW sounders can penetrate the non-precipitating clouds; as a result,this process makes the cloud information received by MW sounders different from the imager data. In addition,the coarse resolution of MW sounders makes it unrealistic to remove all cloud affected FOVs. Therefore,the cloud fraction of an MW FOV can be calculated and then applied as the cloud detection.

The current cloud-screening methods in microwave radiance assimilation are mainly based on a deviation between the observed and the simulated BTs from the background status(Bormann et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2014). In the NCEP data assimilation system,the quality control(QC)function defines a microwave observation as a cloud affected radiance if the corresponding scattering index(SI) and cloud liquid water path(LWP)are greater than the thresholds. The SI and liquid water path are estimated with BTs from the observation and model background status(Hu et al., 2014). The ECMWF QC system uses a first-guess departure in the window channel and an observationbased estimate of an LWP(Bormann et al., 2013). However,the current QC algorithms are not sufficiently accurate for some clouds, and the misclassification of cloud-contaminated FOV results in a degraded performance of the data assimilation(Hu and Xue, 2006; Zou et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014,2015).

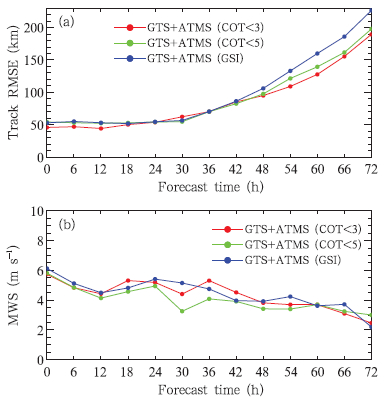

Han et al.(2015)compared the coarse resolution AMSU-A FOV(45 km)with the high resolution MODIS cloud mask(1 km) and found that a large portion of the coarse clear FOV is contaminated with small but relatively thick clouds detected by MODIS. Therefore,the coarse AMSU-A is not good enough to determine whether an FOV is clear or cloudy. From assimilating AMSU-A radiances with different cloud fractions,it is shown that a cloud fraction between 20% and 30% improves the analysis fields and further decreases the forecast errors for hurricane track and intensity. This method is also applied on the Advanced Technology Microwave Sounder(ATMS)/VIIRS onboard Suomi-NPP/JPSS. The optical cloud fraction threshold for ATMS is between 60% and 90%. The different cloud fraction thresholds between AMSU-A and ATMS are possibly due to the different spatial resolutions of the two microwave and the two imager sensors used for microwave sounder sub-pixel cloud detection. Besides the cloud fraction,the COT is another key point to identify the clouds from clear for MW assimilation. Figure 5 provides the track RMSE for Typhoon Neoguri(2003). It is shown that compared to GSI st and -alone cloud detection,the collocated VIIRS cloud fraction with COT less than 3 and COT less than 5 for ATMS assimilation can reduce the track RMSE. Considering the COT less than 3,the track RMSE is approximate 50 km smaller than the track RMSE from the GSI st and -alone cloud detection method. The limitation of this method is that the uncertainty of high spatial imager data,such as MODIS VIIRS COT, and CTH products,would affect the cloud-screening results since those collocated imager products are used to screen the MW radiances for assimilation.

|

| Fig. 5. (a) The track and (b) the maximum wind speed forecast RMSE with ATMS stand-alone cloud detection (blue), ATMS/VIIRS with COT less than 3 (red) and ATMS/VIIRS cloud fraction and COT less than 5 (green). Data are assimilated every 6 hours from 0600 UTC 4 to 0000 UTC 7 July 2014, followed by a 72-h forecast for Typhoon Neoguri (2014). |

From assimilating the MHS radiances,it is found that GSI QC fails to remove some cloudy pixels and therefore degrades the forecast skills. The residual cloudy pixels are usually found at the cloud edges. GOES channel 4(at 10.7 μm)is chosen for MHS cloud detection. Qin et al.(2013)calculated the statistical relationship between GOES channel 4 and the MHS channels 1,2, and 5, and then applied the new cloud detection method for MHS radiance assimilation. The new cloud detection method for MHS effectively removes the cloudy pixels and improved the 24-h quantitative precipitation forecast and precipitation threat scores.

For the cloudy sky,uncertainties in both NWP and RTMs are larger than for the clear sky, and also cloudy regions have higher nonlinearity. For these reasons,the use of all sky radiances in the assimilation system is still challenging. In major operational centers such as ECMWF and NCEP,some progress has been made in assimilating microwave sounder radiances in cloudy skies mainly using MHS and Special Sensor Microwave Imager/Sounder(SSMI/S)observations(Bauer et al., 2010; Geer et al., 2010; English,2014). Nevertheless,accurate cloud detection is still very important and needed in order to improve the microwave sounder radiance assimilation in both clear and cloudy skies.

5. Assimilation of retrieved productsSevere weather systems are usually accompanied with heavy clouds and precipitation. The regions with clouds and precipitation are expected to have large impacts on forecast accuracy,because they are meteorologically sensitive areas(McNally,2002). To avoid the limitations and uncertainties associated with direct assimilation of the cloud-affected radiances(Errico et al., 2007; Geer and Bauer, 2011),in recent studies,the cloud properties and the related moisture information are retrieved from the cloudy regions and then further assimilated into the models. The advantages of assimilating the retrieval products are that(ⅰ)it is easier to h and le the non-linearity of the moist physical process(Moreau et al., 2004);(ⅱ)it is straightforward to apply the quality controls before the retrievals are passed on to the assimilation models(Bauer et al., 2006a,b; Geer et al., 2008); and (ⅲ)it avoids using the forward RTM to calculate the brightness temperature from the model background in the cloudy regions. Therefore,assimilating the clouds and rainfall products retrieved from satellite data is an alternative way to use the information from cloudy regions.

5.1 Retrieved products from IR soundersIR observations are very sensitive to clouds,which has two sides for satellite data assimilation. On the one h and ,reliable cloud detection is required for IR sounder assimilation,which helps the cloud contamination or cloud pixels that are removed from the clear sky assimilation; on the other h and ,high spatial resolution IR imager data provide the high quality of observed cloud characteristics,such as the cloud fraction and cloud height,which could be assimilated in the system to improve the atmospheric analysis and forecasts fields.

The cloud fraction and height from satellite imagers are used to help initialize mesoscale systems in the Met Office(Macpherson et al., 1996; Renshaw and Francis, 2011). Information on the cloud fraction and height from the Spinning Enhanced Visible and Infrared Imager(SEVIRI)is converted to humidity pseudo-observations, and then the humidity profiles are assimilated in the system in a similar way as radiosondes. Some modifications for assimilating the humidity are noted by Renshaw and Francis(2011).

The cloud-top pressure and temperature data from the GOES imager have been used operationally in the Rapid Update Cycle(RUC)since April 2002(Kim and Benjamin, 2001; Benjamin et al., 2004a,b). The GOES single FOV cloud-top pressure provides information on the cloud locations,though not the multiple layers or the cloud optical depths(Li et al., 2001). The clouds or hydrometeors are removed in the model where there are no observed clouds, and the cloud water and /or ice are added in the model where there are observed clouds. Assimilating GOES cloud-top improves the 3-h forecast of cloud-top pressure and frontal cloud band . Otkin(2010)used an ensemble Kalman filter method(Evensen,1994)to assimilate the simulated clear and cloudy observations of the Advanced Baseline Imager(ABI),which is to be launched onboard GOES-R. It is shown that the assimilation of the IR brightness temperature both under clear skies and cloudy skies largely provided the cloud fields.

The retrieved temperature and moisture profiles(Li and Huang, 1999; Li et al., 2000)as well as surface emissivity(Li et al., 2007; Li and Li, 2008)from IR sounders provide useful information for improving NWP. The temperature and moisture soundings from the hyperspectral infrared sounders have high vertical resolution and accuracy. Using the high quality temperature and moisture sounding data,the track errors for Hurricane Ike(2008) and Typhoon Sinlaku(2008) are reduced and the hurricane intensity forecasts are improved(Li and Liu, 2009; Liu and Li, 2010). Zheng et al.(2015)assimilated the AIRS clear-sky temperature profiles in the hurricane environment,which improves the hurricane track forecast and the hurricane moisture environment. Assimilating AIRS soundings derived in cloud-contaminated areas significantly increases the weather forecast skill during the midlatitude boreal winter conditions(Reale et al., 2008). Zavodsky et al.(2007)indicated that the AIRS retrievals provided a positive impact on improving the weather forecast skill.

5.2 Issues of assimilating retrieved productsAssimilating retrieved products is an alternative way to extend the assimilation of satellite observations from clear skies to cloudy skies. The retrieved products bring information about the cloud-affected observations in the system to improve the hydrometeor process and cloud properties in the analysis and forecast atmospheric fields. However,several problems of assimilating the retrieved products are addressed:(ⅰ)the retrieved products are highly dependent on the first guess. If the first guess differs significantly from the model background,the analysis fields are degraded by the mismatch of the large departures(Geer et al., 2008);(ⅱ)the variables assimilated in the model usually are cloud-top pressure,TCWV, and rain rate. However,there are more variables that can be retrieved,such as the surface wind,the vertical profiles of temperature,moisture,cloud, and precipitation. The information is missed by only assimilating one or two variables in the system(Okamoto and Derber, 2006); and (ⅲ)the retrieved cloud properties or the precipitation are usually converted to humidity profiles to affect the analysis fields. This process needs to be done carefully as adding or removing the moisture information at the wrong vertical level would degrade the forecast skills(Renshaw and Francis, 2011). Therefore,it is still worth the efforts to study the direct assimilation of satellite observations under cloudy sky.

6. Direct assimilation of radiances in cloudy skiesECMWF is one of the few operational centers to directly assimilate cloud-affected radiances. The Met Office is also operationally assimilating cloudaffected radiances from both MW and IR. The Meteo- France only assimilates the cloud-affected IR radiances. NCEP is working on the MW all-sky assimilation(Zhu et al., 2015). The other operational centers are under development and will be extended to assimilate the cloud-affected radiances data(Bauer et al., 2011a). Research studies of cloudy radiance assimilation are also discussed in the following parts.

The forward RTM calculates the brightness temperature from the background. If assimilating the cloud-affected radiances is attempted,the forward RTM for cloudy simulation is required. A multiplescattering RTM RROV-SCATT(Bauer et al., 2006c)is implemented at ECMWF for MW cloudy radiance assimilation. The all-sky four-dimensional variational assimilation of MW has been applied operationally since March 2009 at ECMWF for the Special Sensor Microwave Imager(SSMI)/Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer-EOS(AMSR-E)/ TRMM Microwave Imager(TMI)radiances(Bauer et al., 2010,2011b; Geer et al., 2010). The cloud-affected IR radiances from HIRS/AIRS/IASI are also directly assimilated at ECMWF(McNally,2009; Bauer et al., 2011a) and the Meteorological Service of Canada(MSC)(Heilliette and Gar and ,2007). Direct assimilation of the cloudy radiances avoids errors from retrieved products. The observation operator can combine more information from the moist physics other than only one moist variable,such as TCWV or rain rate. Zhang et al.(2013)assimilated cloud-affected radiances from AMSU-A in the TC core in a regional hybrid variational-ensemble data assimilation system(HVEDAS) and the Hurricane Weather Research and Forecasting(HWRF)model.

The direct assimilation of cloud-affected radiances is a big improvement in global satellite data assimilation. However,there are still problems with cloudy radiance assimilation. For MW radiances,it is difficult to h and le frozen precipitation at higher frequencies,so only a few channels can be assimilated(Bauer et al., 2006b). The observation and background errors in cloudy and rainy situations are very hard to set. The first-guess departure of cloudy skies is around 10 times larger than the clear skies and they have a non- Gaussian distribution,which makes it very hard to set the observation errors or very large observation errors(Geer and Bauer, 2011). The very large observation errors result in a relatively small impact from the observations,which indicates that the impacts from cloudy or rainy area are very small. The accuracy of the cloud-top pressure retrieval products affects the cloud-affected IR radiance assimilation(Pavelin et al., 2008). The assimilated cloud-affected radiances can improve the TCWV and LWP at analysis fields,but the improvement of LWP is not obvious for the forecast fields.

7. Summary and discussionSatellite measurements are an important source of global observations in support of NWP. Assimilating satellite radiances under clear skies has greatly improved NWP forecast scores. However,using cloudy radiances in data assimilation remains a challenge. This paper reviewed some major methods for h and ling clouds in research studies and the operational centers.

In many operational centers and the community studies,the data assimilation and RTMs models are designed for clear radiance assimilation. Thus cloud detection is an important step before data assimilation. The current cloud detection scheme for satellite radiances is based on the first-guess departures,which potentially generates considerable risk for confusing the cloud detection by falsely assimilating observed cloudy radiances as clear radiances. High spatial resolution imager data can be collocated with the IR or MW onboard the same platform. The imager data provide useful cloudy information,such as the cloud mask and the cloud optical depth. The cloudy information can help IR or MW remove the cloudy pixels before data assimilation and then further improve the forecast results. This method has already been implemented at ECMWF for IASI radiances assimilation.

To increase the number of radiance observations assimilated in the models,the cloud-cleared radiances are used as an alternative way to assimilate the thermodynamic and hydrometric information under partially cloudy regions. There are three ways to get the cloud-cleared IR radiances,using the background fields,the MW information,or the high spatial imager data information. The advantages and the disadvantages of these three methods are discussed in this paper. The forecast errors in hurricane tracks are reduced with the assimilation of cloud-cleared AIRS radiances.

In recent studies,the cloud properties and the related moisture information retrieved from the cloudy regions are assimilated in the models. The retrieval products,such as cloud-top pressure,rain rates,total column water vapor,cloud-top pressure,etc.,are used in the systems. Assimilating the retrieved products shows improvement for the forecast skill,but the limitations of the retrieved products are discussed in the paper.

The ultimate goal for some operational centers is to directly assimilate the cloud-affected or all-sky radiances. The direct assimilation of cloud-affected radiances is a big improvement for global satellite data assimilation. But due to the less understood observation and background errors in cloudy and rainy situations,the uncertainties of the nonlinearity of the moisture physics process and the some other issues,the direct assimilation of cloud-affected radiances is still hard to carry out. The direct assimilation of cloudy radiances relies on the improvement of RTM in cloudy skies. RTM used in the current operational assimilation is mainly a geometric model that assumes an effective cloud emissivity and an effective cloud-top(Vidot,2015),which can be still useful with improvement on the predetermination of cloud-top pressure,for example,with help of collocated high resolution imager cloud-top pressure(Eresmaa,2014). Ideally,cloud particle absorption and scattering model(Wei et al., 2004)should be considered,but this model needs to be accurate on both radiance and Jacobian calculations for direct radiance assimilation in cloudy skies. Considering the current advancement on RTM with cloudy particle absorption and scattering in cloudy skies,the focus should be on radiance assimilation in single layer cloud situation(e.g.,satellite sees single layer clouds),priority should be given to water cloud situations followed by ice cloud situations. Therefore,IR sub-pixel cloud characterization from high resolution collocated imager cloud products is very important and has been recommended by the International TOVS Working Group(ITWG)to the NWP community at ITSC20(from 27 October to 3 November 2015 in Lake Geneva,Wisconsin,USA)for radiance assimilation. The IR sounder sub-pixel cloud characterization can contain cloud fraction,cloud phase,cloud-top pressure,cloud type,etc. for improving radiance assimilation in cloudy skies. Other alternative approaches include assimilation of cloud-cleared radiances, and /or assimilation of hydrometers(e.g.,liquid water path and ice water path)(Chen et al., 2015; Jones and Stensrud, 2015)retrieved from satellite cloudy radiances. Research continues on cloudy radiances assimilation to improve the analysis fields and the forecast skills.

Acknowledgments. The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for the valuable suggestions and comments that have improved the quality of this paper. Figure 1 was provided by Dr. Bai Wenguang at China Meteorological Administration.

| Ackerman, S. A., K. I. Strabala, W. P. Menzel, et al., 1998: Discriminating clear-sky from clouds with MODIS. J. Geophys. Res., 103, 32141-32157. Bauer, P., P. Lopez, A. Benedetti, et al., 2006a:Implementation of 1D+4D-Var assimilation of precipitation-affected microwave radiances at ECMWF. I:1D-Var. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 132, 2277-2306. |

| Bauer, P., P. Lopez, D. Salmond, et al., 2006b: Implementation of 1D+4D-Var assimilation of precipitation-affected microwave radiances at ECMWF. II:4D-Var. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 132, 2307-2332. |

| Bauer, P., E. Moreau, F. Chevallier, et al., 2006c: Multiple-scattering microwave radiative transfer for data assimilation applications. Quart. J. Roy. Me-teor. Soc., 132, 1259-1281. |

| Bauer, P., A. J. Geer, P. Lopez, et al., 2010: Direct 4D-Var assimilation of all-sky radiances. Part I:Implementation. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 136, 1868-1885. |

| Bauer, P., T. Auligné, W. Bell, et al., 2011a: Satellite cloud and precipitation assimilation at operational NWP centres. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 137, 1934-1951. |

| Bauer, P., G. Ohring, C. Kummerow, et al., 2011b: As-similating satellite observations of clouds and pre-cipitation into NWP models. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 92, ES25-ES28. |

| Benjamin, S. G., D. Devenyi, S. S. Weygandt, et al., 2004a: An hourly assimilation-forecast cycle:The RUC. Mon. Wea. Rev., 132, 495-518. |

| Benjamin, S. G., J. M. Brown, S. S. Weygandt, et al., 2004b: Assimilation of surface cloud, visibility, and current weather observations in the RUC. Preprints for 16th Conference on Numerical Weather Predic-tion, Seattle, Amer. Meteor. Soc., Boston, MA, p1.47. |

| Bjerknes, V., 1911: Dynamic Meteorology and Hydrogra-phy. Part II:Kinematics Carnegie Institute. Gibson Bros, New York, USA, 4-6. |

| Bormann, N., A. Fouilloux, and W. Bell, 2013: Evalua-tion and assimilation of ATMS data in the ECMWF system. J. Geophys. Res., 118, 12970-12980. Cardinali, C., 2009:Monitoring the observation impact on the short-range forecast. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 135, 239-250. |

| Chen, Y. D., H. L. Wang, J. Z. Min, et al., 2015: Vari-ational assimilation of cloud liquid/ice water path and its impact on NWP. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol., 54, 1809-1825. |

| Cucurull, L., R. A. Anthes, and L.-L. Tsao, 2014: Ra-dio occultation observations as anchor observations in numerical weather prediction models and associ-ated reduction of bias corrections in microwave and infrared satellite observations. J. Atmos. Oceanic Technol., 31, 20-32. |

| Daley, R., 1991: Atmospheric Data Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. |

| English, S., 2014: Satellite data assimilation at NCEP, 2014 JCSDA Seminars, College Park, MD, Amer. JCSDA.[Available online at http://www.jc-sda.noaa.gov/documents/seminardocs/2014/English20141020.pptx]. |

| Eresmaa, R., 2014:Imager-assisted cloud detection for assimilation of Infrared Atmospheric Sounding In-terferometer radiances. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 140, 2342-2352. |

| Errico, R. M., P. Bauer, and J.-F. Mahfouf, 2007: Issues regarding the assimilation of cloud and precipitation data. J. Atmos. Sci., 64, 3785-3798. |

| Evensen, G., 1994: Sequential data assimilation with a nonlinear quasi-geostrophic model using Monte Carlo methods to forecast error statistics. J. Geo-phys. Res., 99, 10143-10162. |

| Eyre, J. R., and W. P. Menzel, 1989: Retrieval of cloud parameters from satellite sounder data:A simula-tion study. J. Appl. Meteor., 28, 267-275. |

| Garand, L., M. Buehner, S. Heilliette, et al., 2013: Satel-lite radiance assimilation impact in new Canadian ensemble-variational syste. Proceedings of the 2013 EUMETSAT Meteorological Satellite Conference, 16-20 September, 2013, Vienna, Austria, 1-7. |

| Geer, A. J., P. Bauer, and P. Lopez, 2008: Lessons learnt from the operational 1D+4D-Var assimila-tion of rain-and cloud-affected SSM/I observations at ECMWF. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 134, 1513-1525. |

| Geer, A. J., P. Bauer, and P. Lopez, 2010: Direct 4D-Var assimilation of all-sky radiances. Part II:Assess-ment. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 136, 1886-1905. |

| Geer, A. J., and P. Bauer, 2011: Observation errors in all-sky data assimilation. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 137, 2024-2037. |

| Han, H., J. Li, M. Goldberg, et al., 2015: Microwave sounder cloud detection using a collocated high res-olution imager and its impact on radiance assimila-tion in tropical cyclone forecasts. Mon. Wea. Rev., in press. |

| Heilliette, S., and L. Garand, 2007: A practical approach for the assimilation of cloudy infrared radiances and its evaluation using airs simulated observations. Atmos.-Ocean, 45, 211-225. |

| Hu, M., H. Shao, D. Stark, et al., 2014: Gridpoint Statistical Interpolation (GSI) community ver-sion 3. 3 user's guide. 108 pp.[Available online at http://www.dtcenter.org/com-GSI/users/docs/users-guide/GSIUserGuide-v3.3.pdf]. |

| Hu, M., and M. Xue, 2006:Implementation and evalu-ation of cloud analysis with WSR-88D reflectivity data for GSI and WRF-ARW. Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, L07808, 1-6. |

| Huang, H.-L., and W. L. Smith, 2004: Apperception of clouds in AIRS data. Proc. ECMWF Workshop on Assimilation of High Spectral Resolution Sounder in NWP, June 28-July 1, 2004, 155-169. |

| Jones, T. A., and D. J. Stensrud, 2015: Assimilating cloud water path as a function of model cloud mi-crophysics in an idealized simulation. Mon. Wea. Rev., 143, 2052-2081. |

| Joo, S., J. Eyre, and R. Marriott, 2013: The impact of MetOp and other satellite data within the Met office global NWP system using an adjoint-based sensitiv-ity method. Mon. Wea. Rev., 141, 3331-3342. |

| Kalnay, E., 2003: Atmospheric Modeling, Data Assimila-tion and Predictability. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 51-72. |

| Kelly, G., and J.-N. Thepaut, 2007: Evaluation of the impact of the space component of the global observa-tion system through observing system experiments. ECMWF Newsletter, No. 113, ECMWF, Read-ing, United Kingdom, 16-28.[Available online at http://www.ecmwf.int/publications/newsletters/pdf/113.pdf]. |

| Kim, D., and S. G. Benjamin, 2001:An initial RUC cloud analysis assimilating GOES cloud-top data. Preprints, 14th Conf. Num. Wea. Pred., Ft. Laud-erdale, FL, Amer. Meteor. Soc., 113-115. |

| Le Marshall, J., J. Jung, J. Derber, et al., 2005: AIRS hyperspectral data improves Southern Hemisphere forecasts. Aust. Meteor. Mag., 54, 57-60. |

| Le Marshall, J., J. Jung, J. Derber, et al., 2006: Improv-ing global analysis and forecasting with AIRS. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 87, 891-894. |

| Li, J., and H.-L. Huang, 1999: Retrieval of atmospheric profiles from satellite sounder measurements by use of the discrepancy principle. Appl. Opt., 38, 916-923. |

| Li, J., W. Wolf, W. P. Menzel, et al., 2000: Global sound-ings of the atmosphere from ATOVS measurements:The algorithm and validation. J. Appl. Meteor., 39, 1248-1268. |

| Li, J., J. L. Li, E. Weize, et al., 2007: Physical retrieval of surface emissivity spectrum from hyperspectral infrared radiances. Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, L16812. |

| Li, J., and J. L. Li, 2008: Derivation of global hyper-spectral resolution surface emissivity spectra from advanced infrared sounder radiance measurements. Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, L15807. |

| Li, J., C. Y. Liu, H.-L. Huang, et al., 2005: Optimal cloud-clearing for AIRS radiances using MODIS. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., 43, 1266-1278. |

| Li, J., and H. Liu, 2009: Improved hurricane track and intensity forecast using single field-of-view advanced IR sounding measurements. Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, L11813. |

| Li, J., W. P. Menzel, and A. J. Schreiner, 2001: Vari-ational retrieval of cloud parameters from GOES sounder longwave cloudy radiance measurements. J. Appl. Meteor., 40, 312-330. |

| Li, J., W. P. Menzel, F. Y. Sun, et al., 2004: AIRS subpixel cloud characterization using MODIS cloud products. J. Appl. Meteor., 43, 1083-1094. |

| Liu, H., A. Collard, and J. Derber, 2015: Varia-tional cloud-clearing with CrIS data at NCEP, American Meteorological Society 2015, Phoenix, Arizona, January 5, 2015. [Available online at http://www.jpss.noaa.gov/AMS-2015/Presentations/1-Variational-Cloudclearing-with-CrIS-data-at-NCEP.pdf]. |

| Liu, H., and J. Li, 2010: An improvement in forecast-ing rapid intensification of Typhoon Sinlaku (2008) using clear-sky full spatial resolution advanced IR soundings. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol., 49, 821-287. |

| Macpherson, B., B. J. Wright, W. H. Hand, et al., 1996: The impact of MOPS moisture data in the UK Me-teorological Office data assimilation scheme. Mon. Wea. Rev., 124, 1746-1766. |

| McNally, A. P., 2002: A note on the occurrence of cloud in meteorologically sensitive areas and the impli-cations for advanced infrared sounders. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 128, 2551-2556. |

| McNally, A. P., 2009: The direct assimilation of cloud-affected satellite infrared radiances in the ECMWF 4D-Var. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 135, 1214-1229. |

| McNally, A. P., and P. D. Watts, 2003: A cloud detec-tion algorithm for high-spectral-resolution infrared sounders. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 129, 3411-3423. |

| McNally, T., M. Bonavita, and J.-N. Thépaut, 2014: The role of satellite data in the forecasting of Hurricane Sandy. Mon. Wea. Rev., 142, 634-646. |

| Moreau, E., P. Lopez, P. Bauer, et al., 2004: Variational retrieval of temperature and humidity profiles using rain rates versus microwave brightness tempera-tures. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 130, 827-852. |

| Okamoto, K., and J. C. Derber, 2006: Assimilation of SSM/I radiances in the NCEP global data assimila-tion system. Mon. Wea. Rev., 134, 2612-2631. |

| Otkin, J. A., 2010: Clear and cloudy sky infrared bright-ness temperature assimilation using an ensemble Kalman filter. J. Geophys. Res., 115, D19207. |

| Pangaud, T., N. Fourrie, V. Guidard, et al., 2009: As-similation of AIRS radiances affected by mid-to low-level clouds. Mon. Wea. Rev., 137, 4276-4292. |

| Pavelin, E. G., S. J. English, and J. R. Eyre, 2008: The assimilation of cloud-affected infrared satellite radi-ances for numerical weather prediction. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 134, 737-749. |

| Qin, Z. K., X. L. Zou, and F. Z. Weng, 2013: Evalu-ating added benefits of assimilating GOES Imager radiance data in GSI for coastal QPFs. Mon. Wea. Rev., 141, 75-92. |

| Reale, O., J. Susskind, R. Rosenberg, et al., 2008: Im-proving forecast skill by assimilation of quality con-trolled AIRS temperature retrievals under partially cloudy conditions. Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, L08809. |

| Renshaw, R., and P. N. Francis, 2011: Variational as-similation of cloud fraction in the operational Met Office Unified Model. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 137, 1963-1974. |

| Rienecker, M., R. Galaro, R. Todling, et al., 2008: GMAO's atmospheric data assimilation contribu-tions to the JCSDA and future plans, JCSDA Seminar, 16 April, 2008. [Available online at http://www.jcsda.noaa.gov/documents/seminardocs/GMAO-JCSDA-20080416.pdf]. |

| Smith, W. L., 1968: An improved method for calculating tropospheric temperature and moisture from satel-lite radiometer measurements. Mon. Wea. Rev., 96, 387-396. |

| Smith, W. L., D. K. Zhou, H.-L. Huang, et al., 2004: Extraction of profile information from cloud con-taminated radiances. Proc. ECMWF Workshop on Assimilation of High Spectral Resolution Sounder in NWP, June 28-July 1, 2004, 145-154. |

| Susskind, J., C. D. Barnet, and J. M. Blaisdell, 2003: Re-trieval of atmospheric and surface parameters from AIRS/AMSU/HSB under cloudy conditions. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., 41, 390-409. |

| Vidot, J., 2015: Overview of the status of radiative trans-fer models for satellite data assimilation. Seminar on Use of Satellite Observations in Numerical Weather Prediction, 8-12 Sept. 2014, Shinfield Park, Read-ing, 1-14. |

| Wang, P., J. Li, J. L. Li, et al., 2014: Advanced infrared sounder subpixel cloud detection with imagers and its impact on radiance assimilation in NWP. Geo-phys. Res. Lett., 41, 1773-1780. |

| Wang, P., J. Li, M. D. Goldberg, et al., 2015: Assimila-tion of thermodynamic information from advanced infrared sounders under partially cloudy skies for regional NWP. J. Geophys. Res., 120, 5469-5484. |

| Wei, H. L., P. Yang, J. Li, et al., 2004: Retrieval of semitransparent ice cloud optical thickness from At-mospheric Infrared Sounder (AIRS) measurements. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing, 42, 2254-2267. |

| Wylie, D. P., W. P. Menzel, H. M. Woolf, et al., 1994: Four years of global cirrus cloud statistics using HIRS. J. Climate, 7, 1972-1986. |

| Zavodsky, B. T., S. H. Chou, G. Jedlovec, et al., 2007: The impact of atmospheric infrared sounder (AIRS) profiles on short-term weather forecasts. Proc. SPIE 6565, Algorithms and Technologies for Multispec-tral, Hyperspectral, and Ultraspectral Imagery XIII, 7 May, 2007, 656561J. |

| Zhang, M., M. Zupanski, M.-J. Kim, et al., 2013: Assim-ilating AMSU-A radiances in the TC core area with NOAA Operational HWRF (2011) and a hybrid data assimilation system:Danielle (2010). Mon. Wea. Rev., 141, 3889-3907. |

| Zheng, J., J. Li, T. J. Schmit, et al., 2015: The impact of AIRS atmospheric temperature and moisture pro-files on hurricane forecasts:Ike (2008) and Irene (2011). Adv. Atmos. Sci., 32, 319-335. |

| Zhu, Y., E. H. Liu, A. Collard, et al., 2015: As-similation of all-sky microwave radiances in the NCEP's global forecast system. American Me-teorological Society 2015, Phoenix, Arizona, 6 January, 2015.[Available online at https://ams.confex.com/ams/95Annual/webprogram/Paper268340.html]. |

| Zou, X. L., Z. K. Qin, and F. Z. Weng, 2013: Improved quantitative precipitation forecasts by MHS radi-ance data assimilation with a newly added cloud detection algorithm. Mon. Wea. Rev., 141, 3203-3221. |

2016, Vol. 30

2016, Vol. 30