The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- YAO Yeqing, YU Xiaoding, ZHANG Yijun, ZHOU Zijiang, XIE Wusan, LU Yanyu, YU Jinlong, WEI Lingxiang. 2015.

- Climate Analysis of Tornadoes in China

- J. Meteor. Res., 28(3): 359-369

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-015-4983-0

Article History

- Received July 8, 2014;

- in final form January 13, 2015

2 Chinese Academy of Meteorological Sciences, Beijing 100081;

3 Anhui Meteorological Observatory, Hefei 230031;

4 China Meteorological Administration Training Center, Beijing 100081;

5 National Meteorological Information Center, China Meteorological Administration, Beijing 100081;

6 Anhui Province Climate Center, Hefei 230031

The 1960s and 1970s have seen about twice the average number of tornadoes (7.5 times per year) compared to the mean for 1960-2009. The most frequent occurrence of tornado was in the early and mid 1960s; there were large fluctuations in the 1970s; and the number of tornadoes in the 1980s approached the 50-yr average. Tornado occurrences gradually decreased in the late 1980s, and an abrupt change with dramatic decrease occurred in 1994. The decrease in the tornado occurrence frequency is consistent with the simultaneous climatic change in the meteorological elements that are favorable for tornado formation. Tornado formation requires large vertical wind shear and suffcient atmospheric moisture content near the ground. Changes in the vertical wind shear at both 0-1 and 0-6 km appear to be one important factor that results in the decrease in tornado formation. The changing tendency of relative humidity also has contributed to the decrease in tornado formation in China.

Tornadoes are quite common weather phenomena in China. On 26 March 1967,a total of 13 tornadoes consecutively struck Shanghai and northern Zhejiang Province. These tornadoes pulled up 22 electricity pylons that were designed to withst and winds of up to double scale 12, and caused widespread damage in northern Zhejiang Province. Many buildings collapsed and the casualties were significant(Zhu et al., 1985).Because of the small-scale feature of tornadoes,it is hard for an observation network to capture them. As a result,tornado research is much less developed than the research for other mesoscale disastrous weathers like rainstorms.

The first paper on the topic of tornadoes written by Chinese scientists was published in the 1960s(Bao and Zhao, 1964). Since the late 1960s,observations from the meteorological research radar in China,the type 711 radar with a wavelength of 3 cm,have been applied to tornado research(Ge,1979; Zha,1979; Zhen and Liu, 1982). Using observations from the type 711 radar in Guilin,Guangxi Region in 1977,Zha(1979)conducted the pioneering research to detect the tornado columnar echo in anvil clouds. The tornado echo sometimes could find its way to the ground and stay away from the main thunderstorm. From the radar observation in Guilin in 1977,it was found that the observed tornado formed in the middle troposphere, and dissipated after it hit the ground,lasting less than 18 min. The complete life cycle of a tornado with a diameter smaller than 1 km was observed by Zhen and Liu(1982). Since the beginning of the 21st century,the CINRAD-98D network has been operated in China. Tornadoes that have significant impacts have been detected by Doppler weather radar manytimes. Researchers are able to further underst and the tornado by analyzing features of the tornado radar echoes(Yao et al., 2004,2007,2012; Zhen et al., 2004,2009; He et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2006,2008; Zhang et al., 2012; Meng and Yao, 2014; Zhou et al., 2014).

With an appropriate radar location(within 100 km),it is found that the observed tornado is often characterized by a base velocity and a strong cyclone or tornado vortex signature,a lower top and bottom mesocyclone, and a large wind shear compared to other severe convective weathers. Tornadoes tend to form when the height of the bottom of the mesocyclone reaches a minimum value. Based on the analysis of a tornado case in Beijing,Meng and Yao(2014)found that a descending reflectivity core appears before the tornado formation and shrinks after its formation. In the late stage of a tornado life cycle,a tornado debris signature can be detected. Synoptic background situation has been investigated with a focus on the environmental conditions and mesoscale features,which have significant impacts on tornado formation and dissipation(Li and Liu, 1989; Shen,1990; Wang,1996).It is found that tornadoes often form when the atmospheric stratification is unstable, and temperature and humidity both are high at low levels. Significant vertical wind shears have also been observed in tornado events in recent years.

2. DataTornado information is derived from the raw weather records and observational products archived by the National Meteorological Center of China. The data from the primary observation network of weather stations in China cover the period from 1951 to 2010. During this period,the number of weather observation stations has increased from 150 in 1954 to 658 in 1960, and to 684 stations in 2010. To avoid the problem of data inconsistency caused by the changes in the number of weather stations,we only analyze the observations from January 1960 to December 2009. Atornado is identified if the meteorological observation meets the criteria specified by the China Meteorological Administration(2003).

Tornado is a small-scale violently rotating column of air that extends from the base of a thunderstorm to the ground. From the outside,a funnel-shaped cloud extending from the cumulonimbus cloud base can be observed. The funnel-shaped cloud sometimes looks like it is "stretching" or "hanging" in the air, and the cloud base can reach the ground or water surface. A tornado can cause serious damage to almost everything along its path. Based on these specific features,tornadoes can be identified and recorded by professional weather observers. Reports by amateur observers are not included in this analysis,since these reports are often incomplete or inaccurate. Tornado events have a small spatial scale and a short span of life time. Many tornadoes occur far from observation stations, and thus are not recorded. As a result,the real number of tornadoes could be much larger than that of recorded and analyzed tornadoes in this paper. For instance,Bao and Zhao(1964)stated that seven tornadoes occurred in Shanghai from 1962 to 1963,but none of these tornadoes has been recorded by the primary network of national weather stations. Even so,the tornado records from national observation stations are still the most representative and most objective records available for the present study. We used these records to analyze the spatial distribution and interannual and interdecadal changes in tornado events across China. Note that in the past 50 years,the number of the national observation stations has increased a little,which may have some impacts on this analysis.

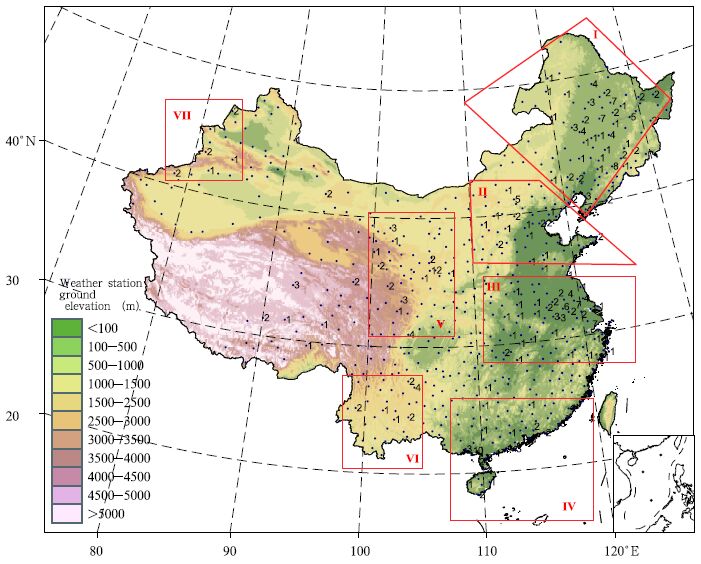

3. Geographical distribution of tornadoesThe number of tornadoes observed by the primary network of national weather stations across China in the past 50 years(1960-2009)is shown in Fig. 1.Tornado distribution in China shows an obvious geographical characteristics: they mainly occur in eastern China(about 81%),especially in the eastern plain of China. The elevation is higher in western China than in eastern China, and demonstrates a step-like staircase decrease from the Tibetan Plateau towards the sea. The Tibetan Plateau with average elevation above 4000 m occupies the first upper step of the topographic staircase, and elevations in the region corresponding to the second upper step is about 1000-2000 m in average, and mainly consists of plateaus and basins. Plains and low hills in eastern China occupy the lowest step of the topographic staircase with average elevation of less than 500 m. Most tornadoes occur in the eastern plain, and some occur over the areas between 100° and 115°E. Occasionally tornadoes can also be observed at both sides of the western Tianshan Mountain and in areas near the Ili River valley in western Xinjiang. In general,the number of tornadoes in the eastern plain of China is much larger than that in the west. No significant differences in tornado numbers are found between South and North China.The Northeast Plain,North China Plain,middle-lower Yangtze Plain, and Pearl River Delta Plain are the areas with high frequency of tornadoes.

Figure 1 illustrates the terrain height in China. From the geographical distribution of tornado occurrence,it is clear that tornado occurrence is highly related to terrain height. More than 80% of the tornadoes occur over eastern China,corresponding to the region that occupies the third(lowest)step of the topographic staircase,where the terrain is largely comprised of plains and hills. Note that more tornadoes occur in plains than over the hilly regions. Although the distance from the Northeast Plain to the Pearl River Delta Plain is quite long and the climate regime changes from temperate to tropical,the frequency of tornado occurrence varies little over this vast region. In the southeastern hilly regions(Fujian,Jiangxi, and southern Anhui provinces)that are within the region of third step of the topographic staircase,the synoptic weather systems affecting the northern part of the region are similar to those affecting the middle-lower reaches of Yangtze River. In the southern part of this region,the synoptic weather systems are quite similar to that in the Pearl River Delta Plain,which is under strong influences of ocean and typhoons. Tornadoes are rarely observed in the southeastern hills of this region,but occur frequently in the middle-lower Yangtze Plain and nearby the Pearl River Delta Plain. This result indicates that the reason why fewer tornadoes occur in the southeastern hills is not because of the weather conditions,but rather due to the effects of terrain forcing. A similar number of tornado events is found over plain areas where the climate regimes are different but the terrain features are similar. The border areas between the hills and flat plains share a similar climate regime but the number of tornado events varies largely,following the variation of the terrain features.

4. Seasonal variation of tornado occurrenceThe season can be quite different in different regions of China. In this study,seven regions were defined according to the geographic distribution and frequency of tornado occurrence(Fig. 1). The seven regions are: Ⅰ: Northeast China; Ⅱ: North China; Ⅲ: middle-lower Yangtze Plain; Ⅳ: South China; Ⅴ: East Tibetan Plateau; Ⅵ: Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau; and Ⅶ: West Xinjiang.

|

| Fig. 1. Tornado occurrences (black numbers) observed by the national principal observation stations (dark blue dots) from 1960 to 2009. The seven highest frequency tornado occurrence regions in China are labeled from I to Ⅶ . |

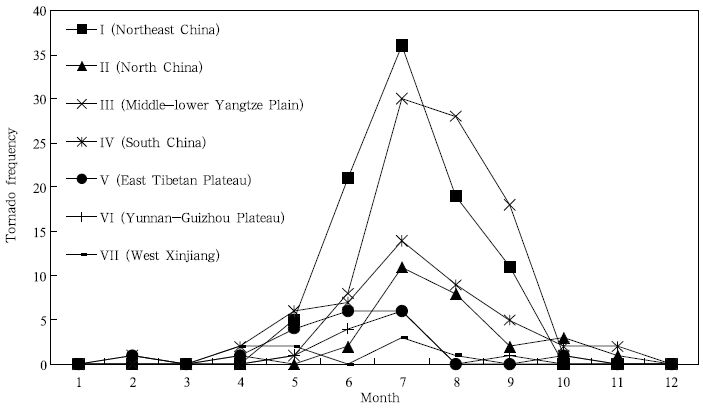

Figure 2 shows the monthly accumulated tornado occurrence for the period 1960-2009 in the seven defined regions. It illustrates two distinct phenomena. First,it shows that areas with large frequency of tornado occurrence are located in Northeast China,the middle-lower reaches of the Yangtze River,South and North China. Apparently,more tornadoes occur over East China than over West China. Second,the highest frequency of tornadoes is in July for all the seven regions.

|

| Fig. 2. Monthly accumulated tornado occurrences in seven regions of China from 1960 to 2009. |

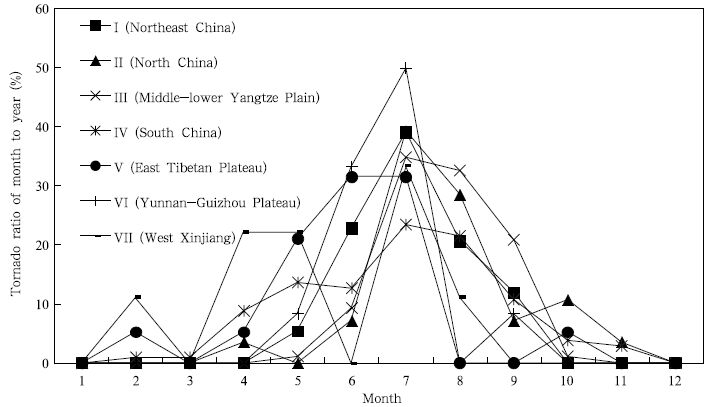

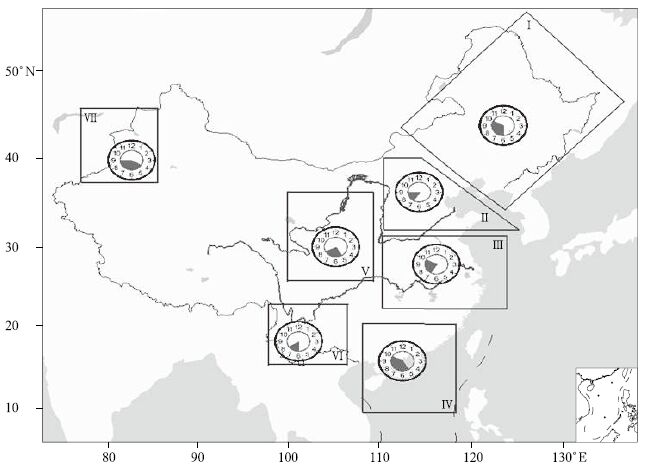

Figure 3 is the percentage of monthly tornado occurrence out of the annual total number of tornadoes. It shows that most tornado events occur in the warm months,with more than 80% of tornadoes observed during June-September in all the regions except South China. A specific month is defined as the tornado outbreak month if the total number of tornadoes in that month is equal to or larger than 10% of its annual amount. Due to the large north-south extension in China,the peak time of tornado occurrence is quite different between North and South China. Figures 3 and 4 show that tornado outbreak time is June-September in Northeast China,July-August in North China,July-September in the Yangtze River region, and May-September in South China,where the longest time span of tornado occurrence is found.

|

| Fig. 3. Monthly percentage of the number of tornadoes to annual total in seven regions of China from 1960 to 2009. |

|

| Fig. 4. Typical tornado outbreak months in regions Ⅰ-Ⅶ, as represented by the shading in each circle. |

In the eastern region of China,the earliest tornado outbreak appears in South China in May,followed by that in Northeast China in June. However,in the Yangtze River region and North China,the tornado outbreak occurs in July. It is clear that the beginning of the tornado outbreak does not postpone following the increased latitude. This is attributed to the influence of typhoons in the Yangtze River region. Typhoons rarely reach North and Northeast China. Severe convective weathers in the Yangtze River region mainly occur from May to August, and decrease sharply in September. There are,however,more tornadoes in September than in June in the Yangtze River region,accounting for up to 20% of the annual total number of tornadoes. This result can at least be partly explained by the fact that the typhoon season is May-August in the Yangtze River region. Many studies have shown that tornadoes are often activated within 2000 km of a typhoon. This type of tornado mainly occurs during July-September,with a peak occurrence in August(Shen,1990; Xue and Yang, 2003). A similar type of tornado is also frequently observed in the U.S. Schultz and Cecil(2009)showed that tornadoes within 750 km of a typhoon accounted for 3.4% of the total tornadoes in the U.S. from 1950 to 2007, and that many of them occurred to the northeast of typhoons. Compared to the situation in East China,tornado occurrence time in West China does not demonstrate any specific patterns. Seasonal distribution of tornado occurrence inWest Xinjiang seems quite r and om,although more tornados occur during April-Augustthan in other months. Tornadoes mainly occur in central regions during May-July.

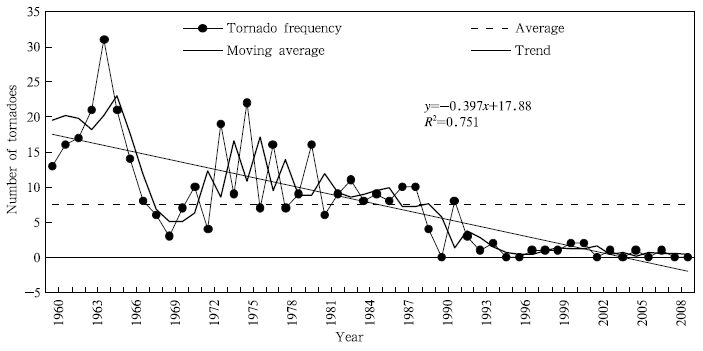

5. Interannual and interdecadal variations of tornado occurrence in ChinaFigure 5 shows that in the 1960s and 1970s the number of tornadoes was about twice the 50-yr average(7.5 times a year; this 50-yr average is likely to be underestimated because some tornadoes occur in undetectable regions). In the 1980s,the number was close to the average, and after the 1990s,the number reduced significantly. Except in 1991,when the number of tornadoes was close to the annual average,the number of tornadoes in the most recent 20 years was much less than the average.

|

| Fig. 5. Annual variation of the number of tornadoes from 1960 to 2009. |

A secondary sliding mean value of nine points,calculated following the method by Wei(2007),shows that the annual variation of tornado occurrence in the early and mid 1960s, and in the mid 1970s and early 1980s,were all above average. In the mid 1960s,tornado occurrences reached the maximum. The interannual variability of tornado occurrence in the 1970s was the largest in the 50-yr period. In the 1980s,tornado occurrences decreased,but had a less interannual variability than in the 1970s. Since the 1990s,all sliding mean values were below the average,with no obvious interannual variability.

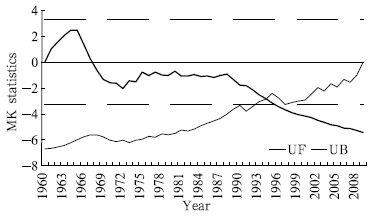

We further adopt the Mann-Kendall method proposed by Wei(2007)to conduct trend analysis for tornado occurrence in China. The results are shown in Fig. 6,in which the labels UF(positive sequence) and UB(reverse sequence)represent sequences of sample statistics,respectively. The UF value is below zero in the late 1960s,indicating a decreasing trend of tornado occurrence. The value exceeds the critical threshold(u0.05 = ±1.96)in the 1980s. It is statistically significant at confidence, and even exceeds the u0.001 = ±3.29 at α = 0.001,indicating that the decreasing trend of tornado occurrence is significant. According to the intersection of UF and UB,the abrupt change in tornado occurred in 1994. In general,the tornado occurrence decreases by about 4 times every 10 years.

|

| Fig. 6. Mann-Kendall curve of tornado occurrences in China from 1960 to 2009. |

Tornado formation requires specific atmospheric conditions. Evans and Doswell(2002) and Craven and Brooks(2004)both suggested that among the many convection parameters,a low lifting condensation level and a large low-level(0-1 km)vertical wind shear both favor strong tornado formation(i.e.,over F2 class). Such environmental conditions are distinctly different to the conditions that favor for the development of other severe convective weather. The lower the lifting condensation level,the greater the likelihood of a tornado formation. Craven and Brooks(2004)showed that more than 75% of tornadoes had a lifting condensation level at 1200 m or less,lower than other types of severe convective weather by 500 m or more. Similarly,the greater the 0-1-km vertical wind shear,the greater the likelihood of tornado formation. The average vertical wind shear is 12 m s-1 for a tornado to form,while the value is only 4-6 m s-1 for the development of hail and other severe convective weather. In addition to the low-level vertical wind shear,the vertical wind shear between the ground and the middle atmosphere is considered an important condition for the development of severe convective weather. Colquhoun and Riley(1996)analyzed correlations between the unstable parameters for over 200 tornado cases. They found that the correlation coefficient between tornado formation and vertical wind shear from the ground to 600 hPa is 0.68. For this reason,the vertical wind shear is considered to be the most relevant diagnostic variable for strong convection development and tornado formation.

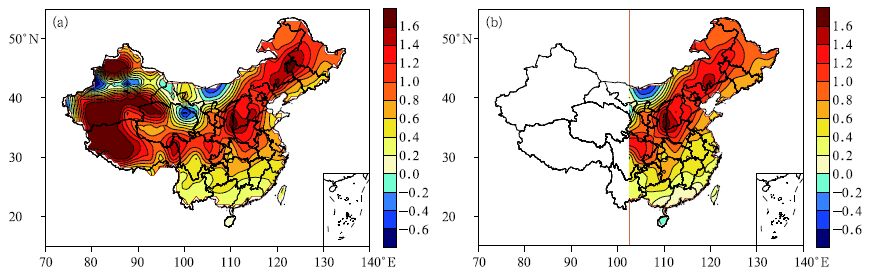

6.1 Climatic changes in low-level relative humidityStudies suggest that a low lifting condensation level is favorable for the tornado generation,while the lifting condensation level depends on the relative humidity at low levels of the atmosphere. More specifically,the larger the relative humidity,the lower the height of the lifting condensation level. The dew point depression(the difference between the temperature and the dew point)is highly related to relative humidity. Using the NCEP reanalysis data with a grid spacing of 2.5° × 2.5° and taking into account that more than 75% of the tornado's lifting condensation level is at 1200 m or below,we further investigate the climatic trends of atmospheric relative humidity below 1200 m. In this study,the ground and 925-hPa dew point depressions are selected. Most of the tornado events occurred during May-September of 1960-2009 and more than 80% of tornadoes did in eastern part of China. In addition,the altitude in western China is mostly above 925 hPa. For these reasons,the analysis of the relative humidity trends in the ground is performed for the entire country,while that at 925 hPa is presented only in eastern China(east of 102.5°E; Fig. 7).

|

| Fig. 7. Variation trends of the average dew point depression (May-September;℃(10 yr)-1) at (a) surface and (b) 925 hPa in eastern China from 1960 to 2009. |

Figure 7 shows the trend of the dew point depression at the surface and at 925 hPa. In eastern China,where tornadoes occur most frequently,the depression shows an increasing trend. This indicates that the relative humidity near the ground and at the surface has been decreasing,leading to the environmental conditions unfavorable for a lower height of lifting condensation level. As a result,the increased lifting condition level makes it hard for tornadoes to form. Such kind of environmental climate change affects tornado formation, and partly explains why the number of tornadoes decreased in recent decades.

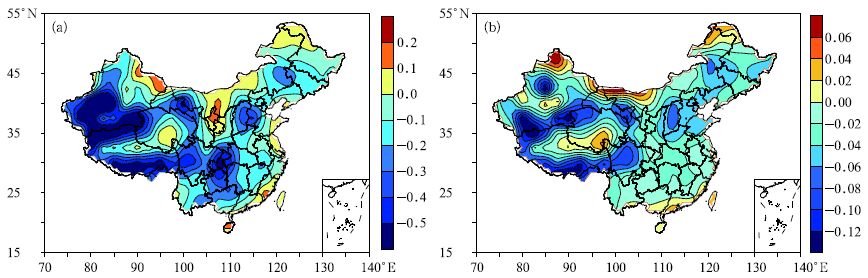

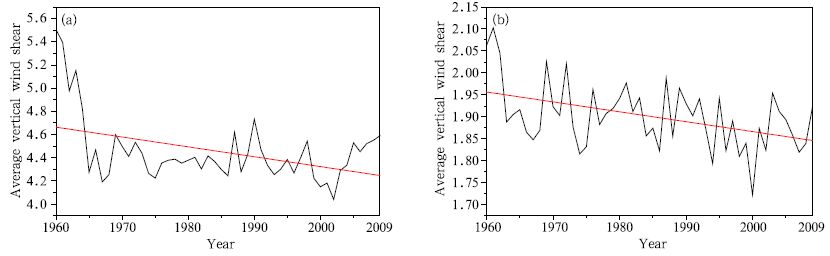

6.2 Climatic changes in vertical wind shearThe NCEP reanalysis gridded data are used to calculate the climatic changing trends of vertical wind shear(Fig. 8)from the ground to 1-km height(0-1 km) and from the ground to 6-km height(0-6 km),respectively. The vertical wind shear is calculated with shr0-1i =(v1i-v0i)/1 and shr0-6i =(v6i-v0i)/6(10-3 s-1). Here shr represents vertical wind shear(with its subdomain),i represents a grid point, and v1 and v6 represent the velocity vector of wind at 1 and 6 km,respectively. v1 and v6 were calculated by using an inverse distance weighting interpolation method.

|

| Fig. 8. Variation trends of the average vertical wind shear (May-September; 10-3 s-1 (10 yr)-1) at (a) 0-1 and (b) 0-6 km from 1960 to 2009. |

Comparing Fig. 1 with Fig. 8 finds that the vertical wind shear within 0-1 km shows a decreasing trend over most of the regions where tornadoes are frequently observed. A slight increasing trend is found over Hainan Isl and ,the Guangdong coast,Jiangsu, and the Sh and ong Peninsula. The 0-6-km vertical wind shear only slightly increased along the coastal region in South China. Several previous studies have revealed that the vertical wind shear is very important for tornado formation, and usually tornadoes are easy to form when there exist large vertical wind shears. The decreasing trend in the vertical wind shear in eastern China represents a change in the large environmental condition that became unfavorable for the generation of tornadoes. This apparently is one of the reasons that explain why tornado occurrences have reduced in recent decades.

In the following we analyze the annual change in vertical wind shear. Tornadoes have occurred at some of the national observation sites. The grid points nearest to those sites were selected for the analysis. Taking the 0-6-km vertical wind shear as an example,calculation of the annual change in vertical wind shear is as follows. First,the daily vertical wind shears at each grid point are given by shri =(v6 - v1)/6,where i represents the grid point, and then the monthly average vertical wind shear at each selected grid point is calculated by:  ,where n represents the number of days in the month,k is the number of grid points, and m is from May to September. Finally,the monthly average vertical wind shear from May to September is used to calculate the annual vertical wind shear for the tornado occurrence season(

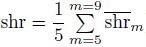

,where n represents the number of days in the month,k is the number of grid points, and m is from May to September. Finally,the monthly average vertical wind shear from May to September is used to calculate the annual vertical wind shear for the tornado occurrence season( ). In Fig. 9,the results show a decreasing trend in both the 0-1- and 0-6-km vertical wind shear during 1960-2009. In the early 1960s,the vertical wind shear is relatively large, and tornado events are the most frequent. From the decreasing trends,it is found that the vertical wind shear reduced more rapidly in the 1960s and 1990s than in other decades,which is consistent with the changing trend of tornadoes. We also compared interannual changes in tornado occurrence and vertical wind shear, and found that they are not entirely consistent with each other,suggesting that the change of vertical wind shear is not the only reason to explain why tornado events were decreasing.

). In Fig. 9,the results show a decreasing trend in both the 0-1- and 0-6-km vertical wind shear during 1960-2009. In the early 1960s,the vertical wind shear is relatively large, and tornado events are the most frequent. From the decreasing trends,it is found that the vertical wind shear reduced more rapidly in the 1960s and 1990s than in other decades,which is consistent with the changing trend of tornadoes. We also compared interannual changes in tornado occurrence and vertical wind shear, and found that they are not entirely consistent with each other,suggesting that the change of vertical wind shear is not the only reason to explain why tornado events were decreasing.

|

| Fig. 9. Average vertical wind shear (May-September; 10-3 s-1) at heights of (a) 0-1 and (b) 0-6 km in regions Ⅰ-Ⅳ from 1960 to 2009. |

In this paper,the geographical distribution of tornado,its outbreak time, and the interannual and interdecadal variability of tornado occurrence are demonstrated based on analysis of tornado observations provided by the primary network of national weather stations from January 1960 to December 2009. The major results are as follows.

(1)About 81% of all tornadoes occurred over the plains of eastern China,i.e.,the Northeast Plain,the North China Plain,the middle-lower Yangtze Plain,Fig. 9. and the Pearl River Delta Plain. The second most tornado prone region is located along the border between the regions of first and second steps of the topographic staircase(100°-115°E),including parts of Yunnan-Guizhou and both sides of the western Tianshan Mountain,as well as a small area in the Ili River valley in West Xinjiang. Tornado occurrences demonstrate distinct geographical characteristics,which is highly dependent on the underlying surface characteristics. Plain areas are conducive to tornado occurrence, and no clear variation is found along the latitude direction.

(2)Across China,the highest frequency of tornado occurrence appears in July. However,the beginning time and the time span of tornado outbreaks are different between North and South China. The earliest outbreak of tornado is found in May in South China, and tornado occurrence can last until September. In the Yangtze River region and to its north,tornadoes occur in June and July, and few are found in September. The end time of tornado formation is slightly later in South China than that in North China. South China has the longest annual outbreak period of tornado,which covers 5 months of the year. The tornado outbreak in Northeast and North China, and the middle-lower Yangtze River region covers about 3-4 months of a year. The beginning of the outbreak in the Northeast Plain,which is located north of 40°N,is in June. This is also the month when the number of tornadoes accounts for 22.8% of the annual total. However,in the middle-lower reaches of the Yangtze River,tornadoes in June account for only 9.3% of the annual total, and increase signiffcantly from July to September(34.9% in July,32.6% in August, and 20.9% in September). This may be related to the influence of typhoons,which often reach this region from July to September.

(3)On the interannual and interdecadal scales,the tornado occurrence demonstrates an overall decreasing trend in China. The number of recorded tornadoes was relatively large in the 1960s and 1970s,about twice the 50-yr average. The trend analysis by using the Mann-Kendall method shows that since the late 1980s,tornado occurrence began to signiffcantly decrease and the abrupt change occurred in 1994.

(4)Further analyses have been conducted to explore the reasons why tornado occurrence is decreasing in China. It is found that the decreasing trend may be related to changes in general climate conditions. The changes in the vertical wind shear and the lifting condensation level in the past 50 years are not favorable for the tornado formation. The dew point depression at the surface has increased, and vertical wind shear at 0-1 and 0-6 km has decreased.

The geographical distribution of tornadoes in China shows that tornadoes mainly occur in plain areas,closely related to the underlying terrain. Since the 1980s,urbanization has been advanced rapidly in China. The expansion rate in the 1990s was 1.6 times as much as that of the 1980s. The urban expansion rate is now 2.7 times as much as that of 20 years ago(http://www.chinautc.com/information/). Grassl and s close to observation stations are often replaced with buildings due to the expansion of urbanization. The decrease in flat grassl and s is not favorable for tornado formation. Changes in the underlying surface caused by urbanization and that of atmospheric elements(vertical wind shear and relative humidity in the low troposphere)may have jointly decreased the tornado occurrence in China.

| Bao Chenglan and Zhao Gangran, 1964: A preliminary analysis on the tornadoes occurring at Shanghai District. Journal of Nanjing University (Natural Sciences), 8, 166-182. (in Chinese) |

| China Meteorological Administration, 2003: Surface Meteorological Observation Criteria. China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 24. (in Chinese) |

| Colquhoun, J. R., and P. A. Riley, 1996: Relationships between tornado intensity and various wind and thermodynamic variables. Wea. Forecasting, 11, 360-371. |

| Craven, J. P., and H. E. Brooks, 2004: Baseline climatology of sounding derived parameters associated with deep moist convection. Natl. Wea. Dig., 28, 13-24. |

| Evans, J. S., and C. A. Doswell, 2002: Investigating derecho and supercell proximity soundings. Preprints, 21th Conf. on Severe Local Storms, AMS, 635-638. |

| Ge Runsheng, 1979: A similar tornado in Beijing. Meteor. Mon., 11, 33-34. (in Chinese) |

| He Caifen, Yao Xiuping, Hu Chunlei, et al., 2006: Analyses on a tornado event in front of a typhoon. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci., 17, 370-375. (in Chinese) |

| Lei Xiangjie, Li Yali, Du Jiwen, et al., 2005: Analysis on the spatio-temporal distribution and daily change rule of cyclone and dust devil in Shaanxi. Journal of Catastrophology, 20, 99-101. (in Chinese) |

| Li Qingcai and Liu Kexian, 1989: Synoptic condition analysis of a tornado in central Shandong. Meteor. Mon., 15, 29-33. (in Chinese) |

| Lu Shijin, 1996: Characteristics of tornado activity in Fujian. Meteor. Mon., 22, 36-39. (in Chinese) |

| Meng Zhiyong and Yao Dan, 2014: Damage survey, radar, and environment analyses on the first-ever documented tornado in Beijing during the heavy rainfall event of 21 July 2012. Wea. Forecasting, 29, 702-724. |

| Schultz, L. A., and D. J. Cecil, 2009: Tropical cyclone tornadoes, 1950-2007. Mon. Wea. Rev., 137, 34713484. |

| Shen Shuqin, 1990: Analysis of the general characteristics and genesis conditions of tornado in front of typhoon. Meteor. Mon., 16, 11-16. (in Chinese) |

| Wang Peilin, 1996: On the environmental conditions for genesis of tornadoes in Zhujiang River delta in spring. J. Trop. Meteor., 12, 60-64. (in Chinese) |

| Wei Fengying, 2007: Climatological Statistical Diagnosis and Prediction Technology. China Meteorological Press, Beijing. (in Chinese) |

| Wei Wenxiu and Zhao Yamin, 1995: The characteristics of tornadoes in China. Meteor. Mon., 21, 36-40. (in Chinese) |

| Xue Deqiang and Yang Chengfang, 2003: Features of tornadoes distribution in Shandong Province. Journal of Shandong Meteorology, 23, 9-11. (in Chinese) |

| Yao Yeqing, Wei Ming, Wang Chenggang, et al., 2004: Case analysis of tornado based on Doppler radar data and lightning location data. J. Nanjing Inst. Meteor., 27, 587-594. (in Chinese) |

| Yao Yeqing, Yu Xiaoding, Hao Ying, et al., 2007: The contrastive analysis of synoptic situation and Doppler radar data for two intense tornado cases. J. Trop. Meteor., 23, 483-490. (in Chinese) |

| Yao Yeqing, Hao Ying, Zhang Yijun, et al., 2012: Synoptic situation and pre-warning of Anhui tornado. Plateau Meteor., 31, 1721-1730. (in Chinese) |

| Yu Xiaoding, Zheng Yuanyuan, Zhang Aimin, et al., 2006: The detection of a severe tornado event in Anhui with China new generation weather radar. Plateau Meteor., 25, 914-924. (in Chinese) |

| Yu Xiaoding, Zheng Yuanyuan, Liao Yufang, et al., 2008: Observational investigation of a tornadic heavy precipitation supercell storm. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 32, 508-522. (in Chinese) |

| Zha Yuquan, 1979: Discussion on radar echo of a tornado. Meteor. Mon., (4), 30-34. (in Chinese) |

| Zhang Yiping, Yu Xiaoding, Wu Zhen, et al., 2012: Analysis of the two tornado events during a process of regional torrential rain. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 70, 961-973. (in Chinese) |

| Zhen Changzhong and Liu Derong, 1982: Radar echo discuss of a tornado. Plateau Meteor., 1, 95-98. (in Chinese) |

| Zheng Yuanyuan, Yu Xiaoding, Fang Chong, et al., 2004: Analysis of a strong classic supercell storm with doppler weather radar data. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 62, 317-328. (in Chinese) |

| Zheng Yuanyuan, Zhu Hongfang, Fang Xiang, et al., 2009: Characteristic analysis and early-warning of tornado supercell storm. Plateau Meteor., 28, 617625. (in Chinese) |

| Zhou Houfu, Diao Xiuguang, Xia Wenmei, et al., 2014: Analysis of the tornado supercell storm and its environmental parameters in the Yangtze-Huaihe region. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 72, 306-317. (in Chinese) |

| Zhu Binghai, Wang Pengfei, and Shu Jiaxin, 1985: Meteorological Dictionary. Shanghai Dictionary Press, Shanghai, 992-993. (in Chinese) |

2015, Vol. 28

2015, Vol. 28