The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- YU Haipeng, HUANG Jianping, LI Weijing, FENG Guolin. 2014.

- Development of the Analogue-Dynamical Method for Error Correction of Numerical Forecasts

- J. Meteor. Res., 28(5): 934-947

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-014-4077-4

Article History

- Received March 31, 2014;

- in final form July 22, 2014

2. Laboratory for Climate Studies, National Climate Center, China Meteorological Administration, Beijing 100081

Since numerical forecasts were successfully realized by Charney et al. (1950), their capability hasbeen much developed(Chen and Xue, 2004). Whileforecast errors are still significant, the forecast accuracy for high-impact weather events remains very low(Wu et al., 2007). The two factors restricting theaccuracy of numerical forecasts are initial error and model error(Zhong et al., 2011), so improving thequality of the initial field and reducing model errorsare two ways to improve forecast capability. In recent years, numerical forecasts have been developed inthe direction of elaborate models and accurate initialfields. This trend has resulted in more intensive observ ational data, more sophisticated assimilation technology, more elaborate numerical models, and morereasonable parameterization. These efforts have muchimproved forecasting accuracy, but with the increasingeconomic and social development, current forecastingcapabilities still cannot satisfy the growing dem and (Wu et al., 2007).

No matter how elaborate the model, forecast errors are inevitable, and the efforts required to makefurther improvements are considerably greater. Alongwith the development of assimilation technology, another effective way to improve forecast accuracy is toconduct error correction. Much work has been done indeveloping error correction technology, and it is worthmentioning that Chinese scientists combined statistical and dynamical methods(Chou, 1986) and obtained a series of innovative theories and methods(Gu, 1958a, b; Zheng and Du, 1973; Chou, 1974;Qiu and Chou, 1990; Huang and Yi, 1991; Zhang and Chou, 1991; Cao, 1993; Zhang and Chou, 1997; Gu, 1998). Particularly, by combining the analogue evolution law of the atmosphere and the dynamic model, the analogue-dynamical method(ADM)was developed(Chou, 1979). This has played an importantrole in improving the prediction theory and raising thelevel of operational forecast capability. Error correction technology using the ADM has been widely usedin medium-range, extended-range, and short-term climate predictions.

This paper first reviews the progress in researchon error correction strategies in Section 2. The principle and evolution of the implementation scheme of theADM, and its development on different-scale weather and climate forecasts are systematically introduced inSection 3. Finally, a summary is provided in Section 4. 2. Progress in research of the error correctiontechnology

Generally, forecast errors can be divided into systematic and non-systematic errors(Shao et al., 2009). The former is independent of time variation, can usually be calculated by the time average of some forecasterrors, and represents the bias between the equilibrium of the numerical model and the actual climatestate. The latter is flow-dependent(dependent onatmospheric state) and includes r and om errors. Focusing on both types of errors, correction techniquescan also be divided into systematic and flow-dependentcorrection(Dalcher and Kalnay, 1987). 2. 1 Systematic correction

The size of systematic correction is independentof model variable, and the common method is to calculate the mean of a large amount of hindcast errors(considering seasonal and diurnal variations) and toadd them to the corresponding forecast results. Zenget al. (1990)adopted a convenient method to remove climate drift by replacing the forecast climatemean with the actual climate mean, then adding theanomaly of the forecast field to the actual climatemean to give the corrected forecast field. Afterwards, they proposed a series of error correction schemes(Zeng et al., 1994), such as the maximum-likelihoodcorrection, minimum bias correction, empirical orthogonal function(EOF)correction, and so on, appliedthem in the Institute of Atmospheric Physics(IAP)two-level atmospheric circulation model, and obtainedsome reasonable results(Lin et al., 1998; Zhao et al., 1999; Zhou et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2000; Li et al., 2005). Moreover, establishing statistical relations onthe basis of hindcast data and historical actual datais also common, such as the approach using PerfectPrediction(PP) and Model Output Statistics(MOS)(Klein et al., 1959; Klein, 1971; Glahn, 1972), whichare forecasted by establishing the relationship betweenthe circulation pattern and the weather phenomena. These methods are all postprocessings after numericalintegration, and are usually called after-the-fact correction(Danforth et al., 2007). This is widely used forits convenient operation, while its shortcoming is notconsidering the nonlinear interaction between external and internal errors in model integration(Danforth et al., 2007).

The online correction differs by adding a forcingterm in the numerical integration to offset the modeltendency error and to restrain the nonlinear growthof the forecast error(Danforth et al., 2008a). As itcorrects the variation tendency of the model variablein the integration, it is also called the tendency errorcorrection. The most common technique for tendencyerror correction is nudging, which originates in dataassimilation by adding a nudging term to bring theforecast close to the observ ational data(Hoke and Anthes, 1976; Jeuken et al., 1996). Some scholars havecompared the nudging with the after-the-fact corrections, and the result indicates that these two typesof correction can both improve forecast abilities, butuncertainty exists in the correction performance. Danforth et al. (2008a)indicated that nudging was betterbeyond one day; Saha(1992)indicated that nudginghad no superiority for forecast skills; Johansson and Saha(1989)indicated that nudging had better effectson small scales, but may destroy the conserv ativeness of transient energy. These differences illustrate thatthe performances of these two correction methods arelargely dependent on the model used, and when themagnitude of the forcing term in the online correctionis too large, coordination among model variables maybe destroyed(Danforth et al., 2008a).

To reasonably estimate the magnitude of the forcing term, Klinker and Sardeshmukh(1992)used themean result of one-step integration to estimate the tendency error, by closing each parameterization in turnto obtain the contribution of each term, and foundthat the gravity wave parameterization played an important role. Kaas et al. (1999)nudged some lowresolution global circulation models(GCMs)toward ahigh-resolution GCM to obtain the empirical interaction function of the horizontal diffusion, and reducedthe large-scale systematic errors. The above two methods are complex in operation, and empirical estimationis usually adopted in practical numerical models, i. e., the ensemble mean of the ratios of some forecast errors and forecast time is set as the forcing term. Thismethod assumes that the forecast error grows linearly(Yang et al., 2008), and it dem and s that the forecasttime be not too long. As for the selection of forecasttime, different investigations have shown different results. Danforth et al. (2007)set it to 6 h, same as theinterv al of the reanalysis dataset, and averaged all ofthe 6-h forecast errors from the same month from theprevious 5 years as the estimation. T o avoid the influence of diurnal variation, Saha(1992)averaged all the24-h forecast errors from the month before the initialtime. Yang et al. (2008)averaged a large amount of 6-, 12-, 18-, and 24-h forecast errors from different years, to estimate the current forecast error, which avoids thevariation in the tendency error from different forecasttimes.

The above empirical correction method is easy torealize, but cannot ensure that the introduced forcing term is optimal. The optimal is usually relatedto variation assimilation. In the traditional fourdimensional variational data assimilation(4DV ar)system, the model is assumed to be perfect, and the effectof model errors is not considered. The weak-constraint4DV ar developed by Bennett et al. (1996, 1997)hasconsidered the existence of model errors. By introducing a term of tendency model error, both the initialerror and model error are reduced. This kind of technique has achieved remark able effects in both simple and complex numerical models(Derber, 1989; Zupanski, 1993; Trémolet, 2007; Akella and Navon, 2009), but the format of the tendency error needs to be assumed as a priori and tested by experiments. Additionally, the solution of 4DV ar is usually restricted bythe necessity to establish an adjoint model, and the appended term of the model error undoubtedly increasesthe calculation load. 2. 2 Flow-dependent correction

Some studies(Saha, 1992; DelSole and Hou, 1999;DelSole et al., 2008)have indicated that systematiccorrection can reduce systematic errors, but has littleeffect on non-systematic errors, which makes it necessary to develop flow-dependent correction.

Leith(1978)established the relationship betweentendency errors and state variables using a statisticalapproach, which expressed the forcing term as the linear function of the state variables, and provided a statistical model with a large number of samples. Thoughthe derivation was under a linear assumption, the results showed that it also had effects on nonlinear models. Delsole and Hou(1999)applied this method in aquasi-geostrophic model and effectively improved theforecast results, but the error covariance matrix required a large amount of calculation. Danforth et al. (2007) and Danforth and Kalnay(2008a, b)reducedthe dimension of this method by using singular valuedecomposition(SVD). The 6-h forecast results froma quasi-geostrophic model indicated that this methodcould reduce errors in some areas with high values, but the global improvement is little. A common stepin the above studies is to establish an error covariancematrix by using a large number of training samples, meaning that the established statistical relationshipdepends highly on the selected samples, and the stability is diffcult to ensure. Once the forecast modelis changed or corrected, the rebuilding of the error covariance matrix needs large amounts of computation and is diffcult to transplant(Zheng, 2013).

With a linear system, establishing the statisticalrelationship is an effective approach, and the more thesamples, the more stable the relationship. With a nonlinear system, the relationship between the correctioneffect and the samples is not stable, and a larger number of samples may not be better. Therefore, the selection of samples is important(Chou and Ren, 2006).

The analogue phenomenon exists widely in theevolution of atmosphere and ocean(Zhao et al., 1982;Wang et al., 1983). For two similar atmospheric states, their evolutions are usually similar. This phenomenonprovides a reference for selecting samples. For example, Chen and Ji(2003) and Chen et al. (2006a, b)utilized phase space reconstruction theory and a prediction method based on nonlinear time series, searchedfor the analogue history information to forecast thecurrent state. They thus constructed a regional nonlinear dynamic forecast model on zonal average onthe monthly scale, and conducted the correction inthe process of model integration. The results indicated that it not only reduced the zonal averaged error, but also had effects on some wave components. They showed that the analogue phenomenon has reference values for improving model forecasting ability.

Based on the above ideas, some investigators combined the analogue phenomenon with the dynamicalmodels, and developed an analogue-dynamical method(ADM)to correct forecast errors. In the following section, the principle and evolution of this method will besystematically introduced, with a focus on its development in different forecast ranges. 3. Development of the ADM 3. 1 Analogue phenomenon and forecast

The analogue phenomenon exists in the atmosphere and ocean, and the analogue forecast basedon this phenomenon has long been used widely. Thebasis of this method is, for two similar initial fields, when the atmosphere is in a stable flow pattern, theanalogue will be maintained on synoptic timescales. On monthly and seasonal scales, the analogue rhythmphenomenon also exists; i. e., the atmosphere circulation experiences an alternate process of analoguedisanalogue-analogue in the long-term evolution, whilethe formation of this phenomenon is different from thelaw of analogue on synoptic scales. As for the dynamical form, Huang and Chou(1990), Huang(1991), and Huang et al. (1990a)studied this form with a coupledocean-atmosphere model. Their results showed thatthe analogous rhythm is a non-uniform oscillation ofanalogous deviation disturbance, caused by the nonlinear coupled interaction of the ocean-atmosphere system and the seasonal variation of monthly mean circulation. They found that the analogue phenomenon isnot formed by the evolution of atmosphere or ocean, but that the ocean-atmosphere interaction plays animportant role and the seasonal variation of monthlymean circulation increases the amplitude of the disturbance markedly. They also indicated that the ocean and the seasonal variations are important factors whenchoosing analogues.

Analogue forecasting is widely used in weather and climate forecasting. Lorenz(1969)used naturalanalogue samples to study the predictability of forecast error growth, and showed that finding strict analogue samples is diffcult. This conclusion was con-firmed by Van den Dool(1994). While this does notmean that analogue forecasting lacks scope, Van denDool sequentially proposed regional analogue( VandenDool, 1989, 1991), construction analogue( VandenDool et al., 2003), and other methods. Barnett and Preisendorfer(1978)reduced the dimensions of thestate space by EOF, and extracted the "analogue climate state vectors, " which are used to describe theclimate system evolution to select analogues. The analogue forecast was put into operation at NCEP as reported by Livezey and Barnston(1988).

It may be too simple to regard the future state asa repetition of past states(Ren and Chou, 2007a). Bycombining the analogue forecast and dynamical models, the ADM became an effective means for improvingthe accuracy of numerical forecasts. 3. 2 Principle of the ADM

The ADM was proposed in 1979, and the basicthought was "regarding the forecast field as a smalldisturbance superimposed on historical analogue fields, so historical analogue errors can be used to estimate and correct forecast errors"(Chou, 1979). Thismethod acknowledged the existence of tendency error, and estimated it by historical analogues. Its principleis as follows.

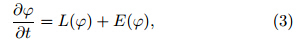

The numerical forecast is proposed as the initialproblem of a partial differential equation, expressedas:

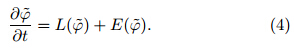

where ψ is the model state variable, L is the numerical model operator, t0 is the initial time, and ψ0 isthe initial value. Because of the existence of modelerrors, the evolution of model atmosphere is differentfrom that of the actual atmosphere. By expressing thetendency of the model error as E, the evolution of theactual state variable ψ can be described as:where E is the functional of the state variable, whichis consistent with the view of Leith(1978). Comparing Eqs. (1)with(3), it can be seen that, if E(ψ)is known, adding it to the model can force the modeltendency in each step toward the actual state. An analogue state can be found in the historical dataset, and the current state variable is regarded as a disturbanceof the historical analogue, i. e., ψ = +

+  , where

, where  isthe analogue state variable, and

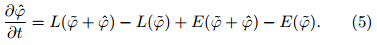

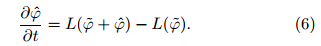

isthe analogue state variable, and  is the analogue deviation. With consideration of the historical evolutionof the actual atmosphere, the analogue reference statesatisfies:Subtracting Eq. (4)from Eq. (3), the deviationequation becomes:Calculating the tendency error is diffcult; toavoid calculating it, the ADM replaces the currenttendency error with the tendency error of historicalanalogues, resulting inThe control variable of Eq. (6)has changed fromψ to

is the analogue deviation. With consideration of the historical evolutionof the actual atmosphere, the analogue reference statesatisfies:Subtracting Eq. (4)from Eq. (3), the deviationequation becomes:Calculating the tendency error is diffcult; toavoid calculating it, the ADM replaces the currenttendency error with the tendency error of historicalanalogues, resulting inThe control variable of Eq. (6)has changed fromψ to  . After obtaining

. After obtaining  by solving Eq. (6), addingit to the

by solving Eq. (6), addingit to the  produces the current forecast field. Comparing Eqs. (1), (4), and (6)reveals a clear difference:the original forecast Eq. (1)has omitted the wholetendency error, while Eq. (6)has omitted the difference between the current tendency error and thetendency error of the analogue reference state. Equation(6)considers the effect of the analogue evolutionof the circulation anomaly, and thus theoretically hashigher accuracy. Meanwhile, it identifies certain analogue selections, i. e., analogous initial value, analogousclimate state, and analogous boundary(Qiu and Chou, 1989). 3. 3 Early development of the ADM

produces the current forecast field. Comparing Eqs. (1), (4), and (6)reveals a clear difference:the original forecast Eq. (1)has omitted the wholetendency error, while Eq. (6)has omitted the difference between the current tendency error and thetendency error of the analogue reference state. Equation(6)considers the effect of the analogue evolutionof the circulation anomaly, and thus theoretically hashigher accuracy. Meanwhile, it identifies certain analogue selections, i. e., analogous initial value, analogousclimate state, and analogous boundary(Qiu and Chou, 1989). 3. 3 Early development of the ADM

Qiu and Chou(1989)introduced forcing errors, topography height errors, and subgrid errors into aquasi-geostrophic barotropic vorticity equation model, and showed that the ADM could reduce the meansquare errors. By defining an analogue index, thismethod need not be hugely analogous, though the improvement is increased by an increase in both the forecast time and the degree to which it is analogous.

Being a stationary wave(Yi et al., 1990), the atmospheric circulation anomaly has the characteristicof barotropy(Huang and Chou, 1988; Zhou et al., 1989; Huang et al., 1990b; Yang et al., 1990), and isanalogue in the long-term evolution. Huang(1990)introduced these features into the long-term rangenumerical forecasts, developed a quasi-geostrophicbaroclinic ocean-atmosphere coupled model(Huang, 1992), and established the corresponding analoguedeviation equation. They first used the ADM toperform experimental seasonal forecasts(Huang et al., 1993a), monthly forecasts(Huang and Wang, 1991a), and flood season forecasts. Their results indicated that the anomaly centers at 500 hPa wereprecisely produced. The 8-yr mean results(Huang and Wang, 1991b)in summer(August), forecastedfrom winter(January), indicated that the accuracyrate(represented by the consistency of anomaly symbols)was 56. 8% for the 500-hPa height field, and 55. 4% for surface temperature. The 8-yr mean results(Huang et al., 1993b)in winter(February), forecasted from summer(July), indicated that the accuracy ratewas 57% for the 500-hPa height field, and 55. 7% forsurface temperature. The forecast effect was obviouslybetter than the traditional analogue forecast. Theadvantage was more evident with increasing forecasttime. This study provided a new method for seasonalforecasting.

The above work was based on a simple model. Toinvestigate the effectiveness in complex models and improve the accuracy of monthly operational forecasts, Bao et al. (2004)applied this method to the T63L16monthly extended-range operational model(Li et al., 2005)of the National Climate Center(NCC)of China, and established an analogue-dynamical monthly forecast model. They selected multiple analogue referencestates in the historical dataset to create the analoguedynamical forecast. The results indicated that the ensemble mean had a better effect than a single analogue member. The global averaged anomaly correlation coeffcient(ACC)was improved by 0. 2, and theroot mean square error(RMSE)was reduced by 12gpm. From the results of different regions and scales, the tropics and subtropics had the most obvious correction effect; the correction effect on the planetaryscale was improved beyond the 15-day forecast, whilethe accuracy was not improved on the synoptic scale. 3. 4 The simplifie d analogue correction

Besides the development of ADM, D'Andrea and Vautard(2000)(abbreviated as DV2000)independently proposed a tendency error estimating methodby historical analogues. They adopted the 4DV ar technique to obtain the optimal estimation of tendencymodel errors of analogue samples, and added them tothe equation as the approximation of the current forcing term. The basic idea was equiv alent to the ADM;i. e., they approximately replaced the current tendencyerror with that of analogue reference states. The difference is, this method adopted the variational technique to solve Eq. (4)to obtain E( ) and then usedit in Eq. (3), while the ADM subtracted Eq. (4)fromEq. (3), and established a new equation. This meansthat the ADM is a reasonable and effective method and some related early leading work has been completed(Ren, 2006).

) and then usedit in Eq. (3), while the ADM subtracted Eq. (4)fromEq. (3), and established a new equation. This meansthat the ADM is a reasonable and effective method and some related early leading work has been completed(Ren, 2006).

The heavy computation load of the 4DV ar restricted application of the DV2000 method in thequasi-geostrophic baroclinic model. The DV2000method was also diffcult to be applied in sophisticated operational models. Though the early-developedADM has avoided compiling an adjoint model, an analogue deviation equation still needs to be established, which is also too complex to facilitate its applicationin operational models.

Aiming at this problem, Ren et al. (2009)simplified the early ADM by replacing the analogue ofthe tendency error with the analogue of the forecasterror. That is, assuming analogue samples have analogous forecast errors, the current forecast error canbe estimated by that of analogues, thus avoiding thecalculation of tendency error. In practice, the forecasttime is divided into interv als. At each interv al, theensemble mean of the forecast errors of some analoguesamples is superposed on the current forecast results, i. e., the forcing is not by step and the after-the-factcorrection is done at interv als of some steps. As theduration of the analogue is limited, the analogues arereselected after some time. These simplifications haveavoided the rebuilding of a new model, have enhancedthe operability, and are easier to transport to other sophisticated models. A total of 24 cases were selectedto perform the monthly forecast experiment with theT63L16 model(Ren et al., 2006). The results indicated that the global mean ACC was improved by 0. 1, and the RMSE was reduced by 7. 49 gpm; the improvement was more evident in the tropics. The improvement of daily forecasting was concentrated beyond 7days and on the scale of planetary wave; there wasno improvement on synoptic scales. Additionally, theprecipitation forecast for summer has been examinedby using the NCC/IAP T63 ocean-atmosphere coupled model(Ren and Chou, 2007b); the mean resultof 23 cases revealed that the global pattern correlation coeffcient was improved by 0. 092, and by 0. 124for eastern Asia.

The above sections systematically introduced thefundamentals of the ADM and the evolution of practical schemes. When the ADM is applied to different forecast fields, it needs to be further adjusted basedon the characteristics of the particular field. The following section describes application of the ADM todifferent range forecasts. 3. 5 Application of the ADM in extende d-range forecasts

For the ADM and traditional analogue forecasts, the selection of analogue fields is always the core problem. On the one h and , the numerical model is sensitiveto the initial field, and it is diffcult to ensure the consistency of the forecast error evolution between thecurrent state and the analogue state. On the otherh and , the numerical model has a large degree of freedom, and it is diffcult to choose ideal initial analoguevalues(Zheng et al., 2013).

Based on the chaotic characteristic of the atmosphere, Chou et al. (2010)proposed a theory to separate the predictable components that are not sensitiveto initial error from the random components that cannot be predicted. Based on this theory, Zheng et al. (2009, 2010)extracted the basis of the climate attractor(Huang et al., 1989; Wang et al., 1989)by decomposing the historical data with EOF. The model variable was exp and ed, the predictable components wereretained, and the r and om components were filtered. The ADM was developed, based on the predictablecomponents, to avoid the impact of rapid growth ofsmall-scale component errors. As the predictable components are not sensitive to the initial errors and havea small degree of freedom, using them to select analogues can avoid the two diffculties mentioned in thepreceding paragraph. A 6-15-day forecast experimentwas carried out with the T63L16 model(Zheng et al., 2013). Comparison results showed that the ADM, based on predictable components, improved the forecast accuracy beyond 10 days, and offerred a slightimprovement on synoptic scales. This contrasts withthe result described in the preceding section. The reason for this may be that this method can to someextent restrain the growth of small-scale componentserrors. It may also be that the improvement on planetary scales can partly restrain the error growth onsynoptic scales by the interaction between high and low frequencies. As for the r and om components, theprobability distribution can be calculated by using alarge amount of historical data. Compared with theoperational extended-range ensemble forecast systemof the NCC(Zheng et al., 2012), the mean ACC of6-15 days was improved by 0. 12, and the RMSE wasreduced by 12. 36 gpm.

The above study used the climate attractor fromthe historical data as the basis, which is easy to operate. There is a climate drift between the model atmosphere and the actual atmosphere, and their climate attractors are naturally different. No time evolution of the atmospheric pattern can be consideredwhen fixing the climate attractor(Wang et al., 2014). As a result, the large-scale components determined bythe historical data do not correspond to the modelcomponents, whose errors grow slowly. To solve thisproblem, Wang et al. (2012a)calculated the levelsof the predictable components under given initial values using conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation(CNOP)(Mu et al., 2003; Wang and Tan, 2009). Theanalogue-dynamical correction was conducted for thepredictable components, and the r and om componentscorresponding to the historical analogues were averaged. The combination of these two parts formed thecorrected forecast results. The 10-30-day forecast experiments were also conducted with the T63L16 model(Wang et al., 2014), and the global mean ACC of the500-hPa field was improved from 0. 06 to 0. 32. As fordifferent scales, the effect on the planetary scale wasthe most marked. 3. 6 Application of the ADM in short-r angeclimate forecasts

The summer precipitation forecast is an important aspect of short-range climate forecasting, as itrelates to the prevention and reduction of flood disasters. So far, this practice has been diffcult. TheADM plays an important role in improving the forecast accuracy for the flood season. Unlike the abovemonthly and extended-range forecasts, the flood season forecast is a boundary problem affected most byexternal forcing, and presents as low frequency. Therefore, selecting the initial field as the analogue factor isnot suitable, and the external forcing and low-frequency variation should be considered. Feng et al. (2013)used the forecast errors of analogue years to estimate and correct the forecast errors of the currentyear, based on the Beijing Climate Center's coupledgeneral circulation model(BCC-CGCM), and developed a dynamical-statistical quantitative precipitationforecast method for the flood season. The core ofthis method is the filter and combinatorial arrangements of analogue forecast factors. In normal years, the corrections are conducted by optimal multi-factorcombination; when these factors are unusual, the abnormal factors correction scheme is adopted. Working in different regions, Wang et al. (2011, 2012b)established the dynamical-statistical ensemble forecast schemes for the middle and lower reaches of theYangtze River, Xiong et al. (2011, 2012)establishedthe optimal multi-factor forecast scheme in Northeast China, and Yang et al. (2011, 2012)establishedthe multi-factor combination forecast scheme in NorthChina. This forecast system has provided good predictions of the location of the main summer rain b and inChina, as confirmed by the verification following theannual national conference on the flood season in 2009. The mean of the predictive scores(PS)from 2009 to2012 was 73, and the corresponding ACC was 0. 16, both higher than the systematic corrected forecast results of the BCC-CGCM(the mean PS score was 63 and the mean ACC was 0. 01)(Feng et al., 2013). The dynamical-statistical integrated forecasting system for seasonal precipitation(FODAS1. 0), based onthis method was also put into operational forecasting(Feng et al., 2013). In the flood season forecastof 2013, the forecast result had a PS of 74 and anACC of 0. 20; it generally captured the location of thesummer drought and flood of China in 2013. After theflood season of each year, the forecast results from thismethod were checked and summarized, and the reasonfor any climatic anomaly was diagnosed(Zhao et al., 2011, 2013a, 2014). In addition to the above flood season forecast, this method has also been applied to theseasonal forecast of geopotential height field for somecritical regions of China, and it reduced the forecasterrors to some extent(Zhao et al., 2013b).

The El Ninõ-Southern Oscillation(ENSO)is oneof the strongest indicators of climate change and isassociated with an anomalous change in atmospherecirculation. Sun et al. (2006)applied the ADMto the ENSO forecast, and conducted some experiments using the Ninõ3 index with the simplified oceanatmosphere coupled model of the NCC. With regardto the particularity of the ENSO forecast, the partialanalogue selection, which considered only sea surfacetemperature(SST), and the entire analogue selection, which considered both SST and surface wind field, were compared. The results indicated that the entireanalogue selection more accurately reflected the analogue degree of the ocean-atmosphere coupled systemthan did the partial analogue selection. When selecting five analogue samples, and setting the oceanic analogue update period as 20 days and the atmosphericanalogue update period as 10 days, the best effect wasachieved. The experiment with the Ninõ3 index from1998 to 2003 indicated that the ADM had a greatereffect than the control forecast for the whole forecasttime. It had a mean ACC of 0. 45 and an accumulative absolute error of 10. 69℃, while the correspondingaccuracy of the control forecast was 0. 29 and 13. 78℃. 3. 7 Application of the ADM in medium-rangeforecasts

From the above discussion, it can be seen that theADM has effectively improved the accuracy in shortterm climate, monthly mean, and extended-range forecasts, but its improvement in the medium range is notevident, as indicated by Ren et al. (2006). This canbe attributed to the essence of ADM, which considersthe dynamical process of analogue circulation anomalies. This process has a large timescale, the impact ofthe initial field is small, and the low-frequency variation is evident, the analogue evolution of which is easyto grasp. Regarding medium-range forecasts, these aresensitive to initial values, the internal error grows nonlinearly, and it is much more diffcult to carry the flowdependent correction by analogues. Therefore, developing and realizing the ADM for medium-range forecasting is urgently needed.

Working on this problem, Yu et al. (2014)modi-fied the ADM to correct the medium-range operationalforecast model. The above simplified ADM assumed that analogous samples have analogous forecast errors, which is more of an approximation to that inthe early ADM; the reason of this needs to be veri-fied. By introducing the continuity theorem of forecast errors, it is proved under some assumptions thatforecast errors can constitute a continuous curved surface in hyperspace when the volume of the historicaldata is large enough. It is also shown that the currentforecast error can be interpolated with the corresponding hindcast errors of some selected analogue referencestates, which means that the simplification is reasonable. In extreme conditions, the analogue-dynamicalcorrection can be converted into control forecast and systematic correction. In the operational scheme, considering that the medium-range forecast is sensitiveto the initial field and the global model is dependenton the SST, the seasonal and diurnal variations, atmospheric circulation pattern, and SST pattern areall considered when choosing analogue samples. Toavoid the nonlinear growth of errors that could destroy the analogue, the optimal update period was selected as 5 days in sensitivity experiments. Forty caseswere selected from summer and winter to carry out 10-day forecast experiments with GRAPES(Global and Regional Assimilation and Prediction System; Chen et al., 2009). The results(Yu et al., 2014)demonstrated that this method extended the period of validity of the global 500-hPa height field by 0. 8 day, themost remark able being 1. 25 days in the tropical region. The correction effect became more significant asthe lead time increased. Although the analogues wereselected by using the height field at 500 hPa, the forecast ability at all vertical levels was improved. The average increase in ACC was 0. 07, and RMSE decreasedby 10 gpm, on average, at a lead time of 10 days. The magnitude of errors for most forecast fields suchas height, temperature, and kinetic energy decreasedconsiderably by inverse correction. These all showthe effectiveness of the method for medium-range forecasts. 4. Summary

The development of numerical models does notconflict with the development of error correction technology; on the contrary, they supplement each other. On the one h and , the forecast error is not a simple superposition of internal error(initial error) and externalerror(model error), but the result of their nonlinearinteraction(Chen and Ji, 1990). It is diffcult to locate the error origin from the forecast output and tocorrect it positively, thus it is necessary to change thepoint of view. This needs to acknowledge the existenceof forecast errors, summarize their evolution pattern, and establish the empirical relationship to estimate and correct the errors. On the other h and , the numerical forecast treats the atmosphere as a certain system(Chen, 2007); i. e., the future state is determined bythe current state and certain physical rules. Actually, both the numerical model and the initial field are approximate descriptions of the real atmospheric state and have large uncertainties; thus, the forecasted future state must also have a large uncertainty. In contrast, the statistical forecast admits the future uncertainties, and infers the future state probability fromthe information on current and historical states. Thedisadvantage of this line of thoughts is that the physical rules are not considered. Therefore, the dynamical and statistical methods have respective advantages and disadvantages, and combining them(Chou, 1986)to develop a better error correction technique is naturally advantageous.

To this end, the ADM was developed by combining the statistical method with dynamical models and utilizing the analogue information from historicaldata. This paper reviewed the creation and development of this method, and discussed associated key issues, corresponding solutions, and improvement of thismethod for forecasts on different timescales.

This review and related discussion indicate thatthe ADM has been developed and modified considerably over several decades. It has greatly improvedthe ability of numerical models in medium-range, extended-range, monthly mean circulation, and shortrange climate forecasts, and has shown broad application potentials. This method not only considers systematic errors but also includes the information on theevolution of flow-dependent model errors, avoiding the establishment of the statistical relationship betweenforecast error and model variable, and is easy to operate and translate to other sophisticated models(Li et al., 2013).

By comparing the recent ADM with the earlierone, the recent method has been shown to be simplifiedfor application to sophisticated models through replacing tendency errors with forecast errors and replacingthe online correction with after-the-fact correction. These simplifications also induce a problem; i. e., thereis no consideration of the interaction between external and internal errors(Danforth and Kalnay, 2008a). Therefore, a meaningful direction for future researchis to combine the advantages of both recent and earlier methods, and further improve the ADM to makeit easy to operate while still restraining the nonlineargrowth of forecast errors.

Acknowledgments: We thank AcademicianChou Jifan for his efforts in carefully reviewing themanuscript and providing valuable suggestions.

| Akella, S., and I. M. Navon, 2009: Different approaches to model error formulation in 4D-Var: A study with high-resolution advection schemes. Tellus A, 61,112-128. |

| Bao Ming, Ni Yunqi, and Chou Jifan, 2004: The monthly averaged circulation forecast experiments of Analogue-Dynamical Model. Chin. Sci. Bull.,49, 1112-1115. (in Chinese) |

| Barnett, T. P., and R. W. Preisendorfer, 1978: Multifield analog prediction of short-term climate fluctuations using a climate state vector. J. Atmos. Sci., 35,1771-1787. |

| Bennett, A. F., B. S. Chua, and L. M. Leslie, 1996: Generalized inversion of a global numerical weather prediction model. Meteor. Atmos. Phys., 60, 165-178. |

| —-, —-, and —-, 1997: Generalized inversion of a global numerical weather prediction model. II: Analysis and implementation. Meteor. Atmos. Phys., 62,129-140. |

| Cao Hongxing, 1993: Self-memorization equation of atmospheric motion. Sci. China (Ser. B), 23, 104-112. (in Chinese) |

| Charney, J. G., R. Fjortoft, and J. Neumann, 1950: Numerical integration of the barotropic vorticity equation. Tellus, 2, 237-254. |

| Chen Bomin and Ji Liren, 2003: A new approach to improve the monthly dynamical extended forecast. Chin. Sci. Bull., 48, 513-520. (in Chinese) |

| —-, —-, Yang Peicai, et al., 2006a: Monthly extended predicting experiments with nonlinear regional prediction. Part I: Prediction of zonal mean flow. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 20, 283-294. |

| —-, —-, and —-, et al., 2006b: Monthly extended predicting experiments with non-linear regional prediction. Part II: Improvement of wave component prediction. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 20, 295-305. |

| Chen Dehui and Xue Jishan, 2004: An overview on recent progresses of the operational numerical weather prediction models. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 62, 623-633. (in Chinese) |

| —-, —-, Yang Xuesheng, et al., 2009: New generation of multi-scale NWP system (GRAPES): General scientific design. Chin. Sci. Bull., 53, 2396-2407. (in Chinese) |

| Chen Minghang and Ji Liren, 1990: Error growth in numerical prediction and atmospheric predictability. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 4, 147-155. |

| Chou Jifan, 1974: A problem of using past data in numerical weather forecasting. Sci. China, 6, 635-644. (in Chinese) |

| —-, 1979: Some problems in long-term range numerical forecast. Anthology of Medium and Long Term Hydro-Meteorology Forecast. Water Resources and Electric Power Press, Beijing, 216-221. (in Chinese) |

| —-, 1986: Why and how to combine dynamics and statistics. Plateau Meteor., 5, 367-372. (in Chinese) |

| —-, 2007: An innovative road to numerical weather prediction—From initial value problem to inverse problem. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 65, 673-682. (in Chinese) |

| —- and Ren Hongli, 2006: Numerical weather predictionnecessity and feasibility of an alternative methodology. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci., 17, 240-244. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Zheng Zhihai, and Sun Shupeng, 2010: The think about 10-30 days extended-range numerical weather prediction strategy—Facing the atmosphere chaos. Scientia Meteor. Sinica, 30, 569-573. (in Chinese) |

| Dalcher, A., and E. Kalnay, 1987: Error growth and predictability in operational ECMWF forecasts. Tellus A, 39, 474-491. |

| D’andrea, F., and R. Vautard, 2000: Reducing systematic errors by empirically correcting model errors. Tellus A, 52, 21-41. |

| Danforth, C. M., E. Kalnay, and T. Miyoshi, 2007: Estimating and correcting global weather model error. Mon. Wea. Rev., 135, 281-299. |

| —-, and —-, 2008a: Impact of online empirical model correction on nonlinear error growth. Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, L24805. |

| —-, and —-, 2008b: Using singular value decomposition to parameterize state-dependent model errors. J. Atmos. Sci., 65, 1467-1478. |

| DelSole, T., and A. Y. Hou, 1999: Empirical correction of a dynamical model. Part I: Fundamental issues. Mon. Wea. Rev., 127, 2533-2545. |

| —-, M. Zhao, P. A. Dirmeyer, et al., 2008: Empirical correction of a coupled land-atmosphere model. Mon. Wea. Rev., 136, 4063-4076. |

| Derber, J. C., 1989: A variational continuous assimilation technique. Mon. Wea. Rev., 117, 2437-2446. |

| Feng Guolin, Zhao Junhu, Zhi Rong, et al., 2013: Recent progress on the objective and quantifiable forecast of summer precipitation based on dynamical statistical method. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci., 24, 656-665. (in Chinese) |

| Glahn, H. R., and D. A. Lowry, 1972: The use of model output statistics (MOS) in objective weather forecasting. J. Appl. Meteor., 11, 1203-1211. |

| Gu Xiangqian, 1998: A spectrum model based on atmosphere self-memorization theory. Chin. Sci. Bull.,43, 1-9. (in Chinese) |

| Gu Zhenchao, 1958a: On the equivalency of formulations of weather forecasting as an initial value problem and as an “evolution” problem. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 29,93-98. (in Chinese) |

| —-, 1958b: On the utilization of past data in numerical weather forecasting. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 29, 176-184. (in Chinese) |

| Hoke, J. E., and R. A. Anthes, 1976: The initialization of numerical models by a dynamic-initialization technique. Mon. Wea. Rev., 104, 1551-1556. |

| Huang, J. P., Y. H. Yi, S. W. Wang, et al., 1993a: An analogue-dynamical long-range numerical weather prediction system incorporating historical evolution. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 119, 547-565. |

| Huang Jianping, 1990: The spatial and temporal characteristic of circulation anomaly and the design of long-term range numerical model circulation. Meteor. Sci. Technol., (3), 27-32. (in Chinese) |

| —-, 1991: The dynamical mechanism of analogous evolution for circulation anomaly. Acta Sci. Nat. Uni. Pek., 27, 99-108. (in Chinese) |

| —-, 1992: Theoretical Climate Models. China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 152-178. (in Chinese) |

| —- and Chou Jifan, 1988: On the annual variation of the barotropic and baroclinic kinetic energy of monthly mean circulation over the mid-high latitude of the Northern Hemisphere. Plateau Meteor., 7, 260-264. (in Chinese) |

| —-, —-, and Yi Yuhong, 1989: The macro-description of the evolution of 500-hPa monthly anomaly field. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 47, 484-487. (in Chinese) |

| —- and —-, 1990: Studies on the analogous rhythm phenomenon in coupled ocean-atmosphere system. Sci. China (Ser. B), 33, 851-860. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Gao Jidong, and Chou Jifan, 1990a: The analogous rhythms phenomena of monthly mean circulation over the Northern Hemisphere. Plateau Meteor., 9,88-92. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Guo Xueliang, and Chou Jifan, 1990b: The dynamical and statistical analysis of the proportion of the barotropic and baroclinic kinetic energy of monthly mean circulation. Anthology of Long Term Weather Forecast. China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 53-62. (in Chinese) |

| —- and Wang Shaowu, 1991a: The monthly prediction experiments using a coupled analogy-dynamical model. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 5, 8-15. |

| —- and —-, 1991b: The experiment of seasonal prediction using the analogy-dynamical model. Sci. China (Ser. B), 2, 216-224. (in Chinese) |

| —- and Yi Yuhong, 1991: Inversion of a nonlinear dynamical model from the observation. Sci. China (Ser. B), 34, 331-336. (in Chinese) |

| —-, —-, and —-, 1993b: The seasonal prediction experiments using the analogue-dynamical model- Prediction for winter months. Acta Meteor. Sinica,51, 118-121. (in Chinese) |

| Jeuken, A. B. M., P. C. Siegmund, L. C. Heijboer, et al., 1996: On the potential of assimilating meteorological analyses in a global climate model for the purpose of model validation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 101, 16939-16950. |

| Johansson, A., and S. Saha, 1989: Simulation of systematic error effects and their reduction in a simple model of the atmosphere. Mon. Wea. Rev., 117,1658-1675. |

| Kaas, E., A. Guldberg, W. May, et al., 1999: Using tendency errors to tune the parameterization of unresolved dynamical scale interactions in atmospheric general circulation models. Tellus A, 51, 612-629. |

| Klein, W. H., 1971: Computer prediction of precipitation probability in the United States. J. Appl. Meteor.,10, 903-915. |

| —-, B. M. Lewins, and I. Enger, 1959: Objective prediction of five-day mean temperatures during winter. J. Meteor., 16, 672-682. |

| Klinker, E., and P. D. Sardeshmukh, 1992: The diagnosis of mechanical dissipation in the atmosphere from large-scale balance requirements. J. Atmos. Sci.,49, 608-627. |

| Leith, C. E., 1978: Objective methods for weather prediction. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech., 10, 107-128. |

| Li Fang, Lin Zhongda, Zuo Ruiting, et al., 2005: The methods for correcting the summer precipitation anomaly predicted extraseasonally over East Asian monsoon region based on EOF and SVD. Climatic Environ. Res., 10, 658-668. (in Chinese) |

| Li Weijing, Zhang Peiqun, Li Qingquan, et al., 2005: Research and operational application of dynamical climate model prediction system. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci., 16(S1), 1-11. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Zheng Zhihai, and Sun Chenghu, 2013: Improvements to dynamical analogue climate prediction method in China. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 37, 341-350. (in Chinese) |

| Lin Zhaohui, Li Xu, Zhao Yan, et al., 1998: An improved short-term climate prediction system and its application to the extraseasonal prediction of rainfall anomaly in China for 1998. Climatic Environ. Res.,3, 339-348. (in Chinese) |

| Livezey, R. E., and A. G. Barnston, 1988: An operational multifield analog/antianalog prediction system for United States seasonal temperatures. 1: System design and winter experiments. J. Geophys. Res.,93, 10953-10974. |

| Lorenz, E. N., 1969: Atmospheric predictability as revealed by naturally occurring analogues. J. Atmos. Sci., 26, 636-646. |

| Mu, M., W. S. Duan, and B. Wang, 2003: Conditional nonlinear optimal perturbation and its applications. Nonlinear Proc. Geophy., 10, 493-501. |

| Qiu Chongjian and Chou Jifan, 1989: The analoguedynamical method for weather forecasting. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 13, 22-28. (in Chinese) |

| —- and —-, 1990: An optimization method for the parameters of forecast models. Sci. China (Ser. B),2, 218-224. (in Chinese) |

| Ren Hongli, 2006: Strategy and methodology of dynamical analogue prediction. Ph. D. dissertation, Lanzhou University, 52 pp. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Zhang Peiqun, and Li Weijing, et al., 2006: A new method of dynamical analogue prediction based on multi-reference-state updating and its application. Acta Phys. Sinica, 55(8), 4388-4396. (in Chinese) |

| —- and Chou Jifan, 2007a: Study progress in prediction strategy and methodology on numerical model. Adv. Earth Sci., 22, 376-385. (in Chinese) |

| —- and —-, 2007b: Strategy and methodology of dynamical analogue prediction. Sci. China (Ser. D),50, 1589-1599. |

| —-, Chou Jifan, Huang Jianping, et al., 2009: Theoretical basis and application of an analogue-dynamical model in the Lorenz system. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 26,67-77. |

| Saha, S., 1992: Response of the NMC MRF model to systematic-error correction within integration. Mon. Wea. Rev., 120, 345-360. |

| Shao Aimei, Xi Shuang, and Qiu Chongjian, 2009: The variational method to correct nonsystematic errors of numerical foreasting. Sci. China (Ser. D), 2,235-244. (in Chinese) |

| Sun Chenghu, Li Weijing, Ren Hongli, et al., 2006: A dynamic-analogue error correction model for ENSO prediction and its initial hindcast verification. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 30, 965-976. (in Chinese) |

| Trémolet, Y., 2007: Model-error estimation in 4D-Var. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 133, 1267-1280. |

| Van den Dool, H. M., 1989: A new look at weather forecasting through analogues. Mon. Wea. Rev., 117,2230-2247. |

| —-, 1991: Mirror images of atmospheric flow. Mon. Wea. Rev., 119, 2095-2106. |

| —-, 1994: Searching for analogues, how long must we wait? Tellus A, 46, 314-324. |

| —-, J. Huang, and Y. Fan, 2003: Performance and analysis of the constructed analogue method applied to U. S. soil moisture over 1981-2001. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 108, 8617, doi: 10.1029/2002JD003114. |

| Wang Bin and Tan Xiaowei, 2009: A fast algorithm for solving CNOP and associated target observation tests. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 67, 175-188. (in Chinese) |

| Wang Huijun, Zhou Guangqing, and Zhao Yan, 2000: An effective method for correcting the interannual prediction of summer precipitation and atmospheric general circulation. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci., 11(A06),40-50. (in Chinese) |

| Wang Qiguang, Feng Guolin, Zheng Zhihai, et al., 2011: A study of the objective and quantifiable forecasting based on optimal factors combinations in precipitation in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River in summer. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 35, 287-297. (in Chinese) |

| —-, —-, —-, et al., 2012a: The preliminary analysis of the procedures of extracting predicable components in numerical model of lorenz system. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 36, 539-550. (in Chinese) |

| —-, —-, Zhi Rong, et al., 2012b: A study of the error field of the flood period precipitation of the midlower reaches of the Yangtze River as predicted by an operational numerical prediction model. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 70, 789-796. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Chou Jifan, and Feng Guolin, 2014: Extracting predictable components and forecasting techniques in extended-range numerical weather prediction. Sci. China (Ser. D), 57, 1525-1537. |

| Wang Shaowu, Zhao Zongci, and Chen Zhenhua, 1983: The persistence and the rhythm of anomalies of monthly mean atmospheric circulation in relation to ocean-atmospheric interactions. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 41, 33-42. (in Chinese) |

| Wang Shouhong, Huang Jianping, and Chou Jifan, 1989: Some properties of the solutions of large-scale atmospheric motion equations. Sci. China (Ser. B), 3,308-336. (in Chinese) |

| Wu Rongsheng, Tan Zhemin, and Wang Yuan, 2007: Discussions on the scientific and technological development of Chinese operation weather forecast. Scientia Meteor. Sinica, 27, 112-118. (in Chinese) |

| Xiong Kaiguo, Feng Guolin, Huang Jianping, et al., 2011: Analogue-dynamical prediction of monsoon precipitation in Northeast China based on dynamic and optimal configuration of multiple predictors. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 25, 316-326. |

| —-, Zhao Junhu, Feng Guolin, et al., 2012: A new method of analogue-dynamical prediction of monsoon precipitation based on analogue prediction principal components of model errors. Acta Phys. Sinica, 61, 149204. (in Chinese) |

| Yang Chengbin, Huang Jianping, and Zhou Qinfang, 1990: The vertical structure of monthly mean atmospheric circulation anomaly. Anthology of Long Term Weather Forecast. China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 99-106. (in Chinese) |

| Yang Jie, Wang Qiguang, Zhi Rong, et al., 2011: Dynamic optimal multi-indexes configuration for estimating the prediction errors of dynamical climate model in North China. Acta Phys. Sinica, 60,029204. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Zhao Junhu, Zheng Zhihai, et al., 2012: Estimating the prediction errors of dynamical climate model on the basis of prophase key factors in North China. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 36, 11-21. (in Chinese) |

| Yang, X. S., T. DelSole, and H. L. Pan, 2008: Empirical correction of the NCEP global forecast system. Mon. Wea. Rev., 136, 5224-5233. |

| Yi Yuhong, Pan Tao, Huang Jianping, et al., 1990: The teleconnection analysis of latitude anomaly field of Northern Hemisphere in January and July. Plateau Meteor., 9, 43-52. (in Chinese) |

| Yu, H. P., J. P. Huang, and J. F. Chou, 2014: Improvement of medium-range forecasts using the analoguedynamical method. Mon. Wea. Rev., 142, 1570-1587. |

| Zhang Banglin and Chou Jifan, 1991: The application of empirical orthogonal function in climate numerical modeling. Sci. China (Ser. B), 4, 442-448. (in Chinese) |

| Zhang Peiqun and Chou Jifan, 1997: A method improving monthly extended range forecasting. Plateau Meteor., 16, 376-388. (in Chinese) |

| Zhao Junhu, Feng Guolin, Wang Qiguang, et al., 2011: Cause and prediction of summer rainfall anomaly distribution in China in 2010. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 35, 1069-1078. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Yang Jie, Feng Guolin, et al., 2013a: Causes and dynamic statistical forecast of the summer rainfall anomaly over China in 2011. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci.,24, 43-54. (in Chinese) |

| —-, —-, Gong Zhiqiang, et al., 2013b: The experiments of transseasonal prediction by combining together the dynamical and statistical methods of the geopotential height fields on the blocking high in the Eurasian mid-high latitudes. Acta Phys. Sinica, 62,099206. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Zhi Rong, Shen Xi, et al., 2014: Prediction and cause analysis of summer rainfall anomaly distribution in China in 2012. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 38,237-250. (in Chinese) |

| Zhao Yan, Li Xu, Yuan Chongguang, et al., 1999: Quantitative assessment and improvement to correction technology on prediction system of short-term climate anomaly. Climatic Environ. Res., 4, 353-364. (in Chinese) |

| Zhao Zongci, Wang Shaowu, and Chen Zhenhua, 1982: The rhythm and long-term range prediction. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 40, 464-474. (in Chinese) |

| Zeng Qingcun, Yuan Chongguang, Wang Wanqiu, et al., 1990: Experiments in numerical extraseasonal prediction of climate anomalies. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 14, 10-25. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Zhang Banglin, Yuan Chongguang, et al., 1994: A note on some methods suitable for verifying and correcting the prediction of climatic anomaly. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 11, 121-127. |

| Zheng Qinglin and Du Xingyuan, 1973: A new numerical weather prediction model utilized multiple observational data. Sci. China, 16, 289-297. (in Chinese) |

| Zheng Zhihai, 2013: Review of the progress of dynamical extended-range forecasting studies. Adv. Meteor. Sci. Technol., 3, 25-30. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Ren Hongli, and Huang Jianping, 2009: Analogue correction of errors based on seasonal climatic predictable components and numerical experiments. Acta Phys. Sinica, 58, 7359-7367. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Feng Guolin, Chou Jifan, et al., 2010: Compression for freedom degree in numerical weather prediction and the error analogy. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci., 21,139-148. (in Chinese) |

| —-, —-, Huang Jianping, et al., 2012: Predictabilitybased extended-range ensemble prediction method and numerical experiments. Acta Phys. Sinica, 61,199203. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Huang Jianping, Feng Guolin, et al., 2013: Forecast scheme and strategy for extended-range predictable components. Sci. China (Ser. D), 56, 878-889. |

| Zhong Jian, Huang Sixun, Fei Jianfang, et al., 2011: Dynamics of model errors: Accounting for parameters error and physical processes lacking error. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 35, 1169-1176. (in Chinese) |

| Zhou Guangqing, Zeng Qingcun, and Zhang Huarong, 1999: An improved ocean-atmosphere coupled model and its numerical modeling. Prog. Nat. Sci.,9, 542-551. (in Chinese) |

| Zhou Qinfang, Huang Jianping, and Yang Chengbin, 1989: The vertical structure feature of the Northern Hemisphere wintertime general circulation anomalies. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 47, 173-179. (in Chinese) |

| Zupanski, M., 1993: Regional four-dimensional variational data assimilation in a quasi-operational forecasting environment. Mon. Wea. Rev., 121, 2396-2408. |

2014, Vol. 28

2014, Vol. 28