The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- ZHENG Fei, LI Jianping, LIU Ting. 2014.

- Some Advances in Studies of the Climatic Impacts of the Southern Hemisphere Annular Mode

- J. Meteor. Res., 28(5): 820-835

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-014-4079-2

Article History

- Received April 2, 2014;

- in final form July 15, 2014

2 College of Global Change and Earth System Science, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875;

3 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049

About 70% of the total l and surface on the earthis in the Northern Hemisphere(NH), while the oceansoccupy more than 60% of the Southern Hemisphere(SH). This l and -sea distribution determines the distribution of population, with more than 90% living in theNH. Therefore, observations of and research on NH climate systems started earlier than for the SH and havemade more progress. However, the global climate system is an entity and the climate state in the SH canregulate the NH climate via its influence on the exchange of energy, momentum, mass, and water vaporbetween the two hemispheres. In recent decades, thedepletion of Antarctic ozone and the sensitivity of polar climate to global climate change have promptedthe investigation of SH climate systems. For example, one key project of the World Climate ResearchProgramme(WCRP), the Climate and Cryosphere(CliC), has encouraged the development of the Southern Ocean Observing System(SOOS), while another, the Stratospheric Processes and their Role in Climate(SPARC)project, emphasizes the developmentof chemistry-climate models related to polar ozone. In China, scientific expeditions to the Southern Ocean and the Antarctic have taken place for many years. Observational data for SH climate systems have gradually accumulated alongside the rapid development ofsatellite observation, the establishment of ground observation stations in the Antarctic, and the deployment of Argo buoys in the Southern Ocean. Thisincrease in observational data provides a foundation for exploring the variability of SH climate systems.

Atmospheric teleconnections are important phenomena. Earlier studies on atmospheric teleconnection include researches about the Southern Oscillation. The primary teleconnection patterns in the NHinclude the North Atlantic Oscillation(NAO; Walker and Bliss, 1932), the North Pacific Oscillation(NPO; Rogers, 1981), the Eurasian teleconnection(EU; Wallace and Gutzler, 1981), the Pacific-North American teleconnection(PNA; Wallace and Gutzler, 1981), the Arctic Oscillation(AO; Thompson and Wallace, 1998), and the NH annular mode(NAM; Thompson and Wallace, 2000). These low-frequency teleconnection patterns make a large contribution to circulationvariability and play an important role in regulatingregional and hemispheric climate, and thus occupy animportant position in climate research. As more NHteleconnection patterns have been revealed, researchinto the SH annular mode(SAM)has rapidly developed.

The SAM, also known as the Antarctic Oscillation(AAO), is the dominant mode of atmosphericcirculation in the SH extratropics(Gong and Wang, 1998, 1999; Thompson et al., 2000). The generation and persistence of the SAM are associated with waveflow interaction, which is an important internal process in the atmosphere(Limpasuvan and Hartmann, 1999; Lorenz and Hartmann, 2001; Zhang et al., 2012). Temporal variability of the SAM is clearly evident onmany scales: decadal, interannual, seasonal, monthly, sub-monthly, and daily(Fan et al., 2003; Wang and Fan, 2005; Li and Li, 2010, 2012; Zhang et al., 2010; Yuan and Yonekura, 2011). Spatially, the SAM isquasi-barotropic, and its signal is evident in both thetroposphere and the stratosphere. The variability ofthe SAM reflects the out-of-phase relationship betweenatmospheric masses in the SH middle and high latitudes, and is accompanied by a meridional shift ofthe SH jet system. When the SAM is in a positivephase, geopotential height in the SH high and middle latitudes is lower and higher, respectively, and thejet shifts towards the Antarctic. When the SAM is ina negative phase, the situation reverses, and the jetshifts towards the equator. Li and Wang(2003)proposed the concept of an atmospheric annular belt ofactivity, provided a clear explanation of the structureof the SAM, and defined an SAM index that is widelyused in climate research(Ding et al., 2005; Feng et al., 2010; Li and Li, 2012; Sun and Li, 2012).

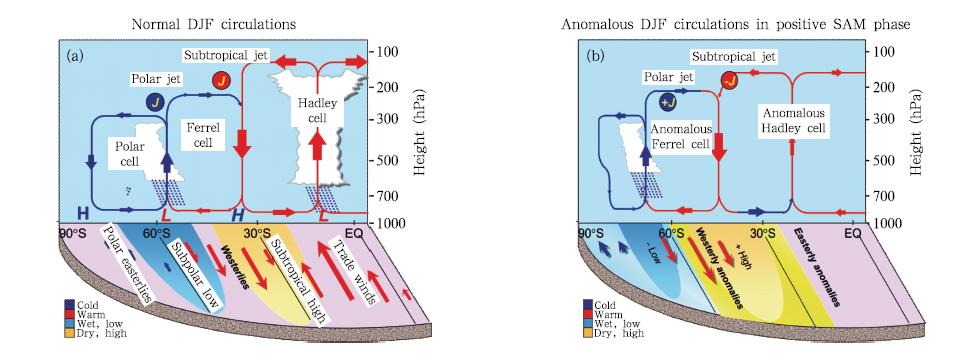

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of the climatological atmospheric circulation in the SH in australsummer(December-February) and the correspondingcirculation anomalies during a positive SAM phase. The positive phase of the SAM corresponds to a poleward shift of the SH jets, and a strengthened polar jetbut a weakened subtropical jet(Fig. 1b). In addition, the Ferrel cell during the positive phase of the SAM isstronger than in the climatology, indicating the importance of the Ferrel cell(Li and Wang, 2003; Li, 2005a, b)to the SAM behavior. As shown in Fig. 1, the SAMcovers a wide latitudinal b and around the earth. Thislarge-scale spatial structure means that the SAM hasa broad climatic impact. There is abundant evidencein the literature showing that the signals of the SAMare not confined to the Antarctic, the SH middle latitudes and the subtropics, but extend to many regionsin the NH. Since the end of the 20th century, therehas been a significant positive trend in the SAM activity in step with global warming(Thompson et al., 2000; Marshall, 2003). This trend has induced climateresponses in many regions, further highlighting the urgency of investigating the influence of the SAM.

|

| Fig. 1. Schematic diagram of(a)the climatology of atmospheric circulation in the Southern Hemisphere in australsummer(December-February) and (b)the corresponding circulation anomalies during a positive SAM phase. |

Variability of the SAM and its climatic influencesare new research directions that have rapidly developed both in China and overseas in recent years. Exploring the climatic influences of the SAM is useful inunderst and ing the interactions between the NH and the SH, and between different latitudes. On the interannual timescale, investigation of the influence of theSAM may provide new predictors and ideas for seasonal prediction. On the climate-change timescale, itcan provide new clues for the attribution of climatechange and new information on downscaling projections of long-term changes in climate variables. Therefore, exploring the climatic influence of the SAM isnot only of scientific significance, but also of practicalvalue. In recent years, Chinese and foreign researchershave made significant progress in underst and ing theclimatic influence of the SAM. This paper lists themain achievements and provides a concise review ofthe new knowledge obtained in recent decades. In thispaper, the AAO is referred to as the SAM and the seasons are defined for the NH unless otherwise specified. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. We briefly review the impact of the SAM on the SHclimate systems in Section 2, and its influence on theNH is introduced in Section 3. The modulating effectof the SAM on climate over China is reviewed in detail in Section 4. In Section 5, we document recentprogress on the topic of climate change related to theSAM. Finally, conclusions are given in Section 6. 2. Influence of the SAM on SH climate

The SAM is the dominant mode of SH extratropical circulation, and its influence on SH climate systems has been investigated in many studies. We reviewthese studies from three aspects: the atmosphere, theocean, and the sea ice. 2. 1 Atmosphere

Thompson et al. (2000)explored the signal of theSAM in the SH extratropical circulation on monthlyscales. Using surface air temperature data from theClimate Research Unit(CRU), they pointed out thatwhen the SAM is in positive phase, mainl and Antarctica is cooler due to adiabatic cooling caused byanomalous upward motion in the near-surface layer, whereas the Antarctic Peninsula is warmer because ofstrengthening warm advection from the ocean, whichis related to the intensification of circumpolar westerlies. Kwok and Comiso(2002) and Schneider etal. (2004)reached similar conclusions using satelliteinfrared surface temperature and passive microwavebrightness temperature, and noted that the SAMmakes the largest contribution to surface air temperature variations over the Antarctic. Based on the observations from Antarctic ground stations, Marshall(2007)explored the seasonal differences in the relationship between the SAM and Antarctic surface airtemperature, by examining the different responsesof air temperature over the Antarctic mainl and and peninsula to the SAM. The author proposed a newmechanism for explaining this response pattern: whenthe SAM is in positive phase, the cooling of mainl and Antarctica is related to a decrease in oceanic meridional heat transport, and the warming of the Antarctic Peninsula is associated with a decrease in cold airoutbreaks from the pole. In addition, Lu et al. (2007)verified the negative correlation between the SAM and surface air temperature in mainl and Antarctica usingmodel(HadAM3)simulations.

The influence of the SAM can extend northwardto the SH subtropics. Bals-Elsholz et al. (2001)showed that when the SAM is in its positive phase, the austral winter(July-September)jet system in theSH tends to split into a subtropical jet and a polarfront jet. The positive phase of the SAM also corresponds to more precipitation over 50°-70°S, but lessover 40°-50°S according to Lu et al. (2007), basedon model(HadAM3)simulations, leading to a dipolelike precipitation anomaly pattern in the SH extratropics. This model simulation verified the conclusions of Gillett et al. (2006), which were derived from station observations, and agreed with other simulationsusing different general circulation models(Watterson, 2000; Cai and Watterson, 2002; Karoly, 2003; Gupta and England, 2006; Lu et al., 2007). The dipole-likeinfluence of the SAM on the SH extratropical precipitation is linked to responses of storm tracks, verticalmotion, and cloudiness to the SAM.

Many researchers have investigated the influenceof the SAM on SH precipitation on regional scale. Their results have shown that precipitation in thesouthern Andes(Gonzáalez and Vera, 2010), SouthAfrica(Fauchereau et al., 2003; Reason and Rouault, 2005), New Zeal and (Renwick, 2002), and NorthwestAustralia(Feng et al., 2013)responds strongly to variations of the SAM. In addition, the SAM is positivelycorrelated with typhoon frequency over the southernIndian Ocean during the typhoon season(December-March), according to Mao et al. (2013). These authorssuggested that when the SAM is in its positive phase, the number of tropical cyclones passing over the north-western coast of Australia(10°-30°S, 100°-120°E)increases by 50%-100% compared with the climatology, primarily due to more frequent generation of tropicalcyclones. The increased frequency of tropical cyclonesis associated with strengthened water vapor convergence and anomalous ascending motion, caused by acyclonic anomaly over the western coast of Australiaduring the positive SAM phase.

Moreover, the precipitation over southwesternWest Australia(SWWA)has shown a significant decreasing trend(Hennessy et al., 1999), and many researchers have investigated the linkage between thisdrying trend and the SAM. For example, some studiesproposed that the SAM can regulate the interannualvariability and long-term trend of SWWA precipitation by modulating the frequency of heavy precipitation(Ansell et al., 2000; Cai and Watterson, 2002; Cai et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005; Cai and Cowan, 2006)orthe position of the SH midlatitude westerlies(Gupta and Engl and, 2006; Meneghini et al., 2007). Hendonet al. (2007)further noted that this influence of theSAM on precipitation over SWWA is most markedin austral summer(December-February). Is australwinter(June-August)precipitation over SWWA alsosignificantly linked to the SAM? Feng et al. (2010)found that the negative correlation between the SAM and austral winter(June-August)precipitation overSWWA is caused mainly by one extreme year(1964). After removing the data of 1964, the correlation between the SAM and austral winter precipitation overSWWA is quite weak. This analysis by Feng et al. (2010)illustrates the importance of objective statistical analysis for obtaining reliable conclusions wheninvestigating possible connections between variables. 2. 2 Ocean

The earth's surface in the SH extratropics hasunique characteristics. This region includes the Southern Ocean, which is a critical channel for transmitting climate signals to the Pacific, the Atlantic, and the Indian Ocean, and plays a key role in modulatingvariability and changes in climate. Therefore, it is important to explore air-sea coupling processes relatedto the SAM in the SH extratropics.

The primary surface circulation system in theSouthern Ocean is the Antarctic Circumpolar Current(ACC), which is characterized by sloping isopycnals and a deep wind-driven current. Lefebvre et al. (2004)used a coupled climate model(ORCA2-LIM)drivenby the NCEP/NCAR reanalysis data to show that anenhanced SAM corresponds to an increased surface velocity in the ACC. Gnanadesikan and Hallberg(2000)analyzed the response of the ACC to wind stress usinga coarse-resolution ocean model from the perspectiveof heat and dynamic balance. Their results showedthat the strengthening of wind stress over the Southern Ocean can enhance the transport of the ACC, and therefore the SAM can modulate ocean transport inthe Drake Passage on the interannual scale(Meredith and Hughes, 2004; Meredith et al., 2004). Zhang and Meng(2011)found that changes in local windstress caused by the SAM result in modulation ofthe ACC transport and tilt of the isopycnal surfaces, which leads to changes in the baroclinic energy conversion rate from the background ocean to mesoscaleeddies, and thus contributes to the interannual variability of mesoscale eddies. The maximum(minimum)zonal wind stress leads the eddy kinetic energy maximum(minimum)by approximately 3 yr.

The influence of the SAM on the SH oceans is notonly manifested in its modulation of oceanic circulation, but also in its regulation of sea surface temperature(SST). When the SAM is in positive phase, theSH circumpolar westerlies shift towards the Antarctic, which forces the changes in ocean dynamics throughchanges in sea surface wind. The northward Ekmantransport is enhanced, leading to a stronger upwellingaround the Antarctic and an anomalous downwellingaround 45°S. Meanwhile, the changes in sea surfacewind associated with the positive phase of the SAMcan also thermally force the ocean, with changes in airsea heat flux(Mo, 2000; Watterson, 2000, 2001; Cai and Watterson, 2002; Hall and Visbeck, 2002; Nan and Li, 2003; Lefebvre et al., 2004; Gupta and England, 2006; Nan et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2009; Zheng and Li, 2012). Therefore, the positive phase of theSAM results in warmer SST in the SH midlatitudes, but cooler SST at high latitudes, leading to a dipolelike SST anomaly pattern. In view of the large heatcapacity of the ocean, this SST anomaly pattern usually persists for about one season(Wu et al., 2009; Zheng and Li, 2012). The influence of the SAM onthe SH extratropical SST and the persistence of thisSST anomaly pattern is an important "bridge" in themodulation of the NH climate by the SAM, as described below.

Furthermore, the association between the SAM and the mixed layer depth is receiving increased attention. The mixed layer depth is regulated by seasurface wind stress, and in turn influences heat exchange between the atmosphere and the ocean, thusdetermining the ocean's capacity to store heat. Unlikethe zonally symmetric response of the SH extratropical SST to the SAM, the mixed layer depth shows azonally asymmetric response to the SAM according to Sallee et al. (2010). The anomalies in meridional wind and ocean heat transport caused by the SAM are theprimary drivers of the zonally asymmetric response ofthe mixed layer depth. 2. 3 Sea ice

The influence of the SAM on SH sea ice is relatively complex, showing some zonal asymmetry(Kwok and Comiso, 2002; Lefebvre et al., 2004). When theSAM is in positive phase, sea ice in theWeddell Sea decreases while that in the Ross Sea increases. This non-zonal response of sea ice to the SAM arises because thewesterlies around the Antarctic Peninsula blow towardthe southeast, while those around the Ross Sea blowtoward the northeast, so that more warmer(colder)air is transported to the Weddell(Ross)Sea(Lefebvre et al., 2004). Lefebvre and Goosse(2005)used model(ORCA2-LIM)simulations to show that this dynamicprocess is the main reason for the thinning of sea iceover the Weddell Sea, whereas the reduction in thearea of sea ice over the Weddell Sea is more closelyrelated to anomalies in thermal processes caused bythe SAM.

In general, the non-zonal response of the SH seaice to the SAM is associated with both dynamic and thermodynamic processes. Gupta and Engl and (2006)investigated the response of the air-sea ice coupled system to the SAM using the NCAR climate model, and showed that the atmospheric and oceanic dynamic and thermodynamic forcings caused by the SAM can explain the variability of the Antarctic sea ice quite well, and that the anomalies in sea ice could persist for several months because of the positive feedback of sea icealbedo.

It is worth noting that the atmosphere and oceanform a coupled system. The SAM can influence SST and sea ice, and these climate sub-systems also feedback to the SAM(Watterson, 2000, 2001; Marshall and Connolley, 2006; Raphael et al., 2011). As thesefeedbacks are not the key points in this paper, theyare not considered in further detail. 3. Influence of the SAM on NH climate

The global atmospheric circulation is a single entity; changes in meridional overturning circulation and other circulation variables in the SH may also influencethe NH circulation. In this section, we review the influence of the SAM on climate in the NH except forChina, which will be covered in the next section.

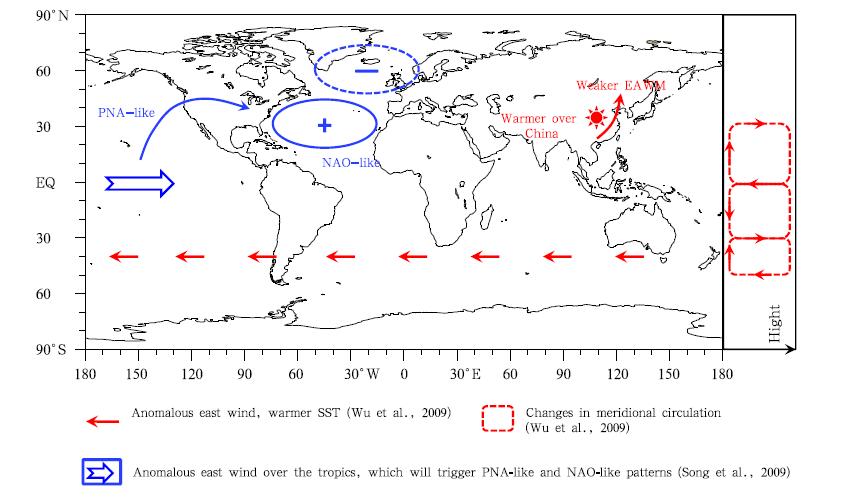

The influence of the SAM on the NH atmospheric circulation is evident on both sub-seasonal and interannual scales. On interseasonal scales, Songet al. (2009)pointed out that in boreal winter(December-February), the positive(negative)phaseof the SAM corresponds to lower(higher)geopotential height and anomalous westerlies(easterlies)overthe mid to high latitudes(45°-65°N)in the Atlantic, but higher(lower)geopotential height and anomalous easterlies(westerlies)over the midlatitudes(25°-40°N), leading to a dipole pattern similar to the NAO(Song and Li, 2009). They suggested the followingmechanism to explain this process: the boreal winterSAM can lead to zonal wind anomalies in the easterntropical Pacific via wave-flow interactions(Thompson and Lorenz, 2004; Song et al., 2009), and these zonalwind anomalies can trigger a PNA-like Rossby wavepropagating toward the North Atlantic, which leadsto eddy momentum anomalies that further evolve intoan NAO-like pattern(Song et al., 2009).

On interannual scales, the SAM is closely linkedto climate in East and South Asia. For example, Ho etal. (2005)found that the positive SAM phase in summer(July-September)corresponds to an anomalousanticyclonic circulation over the western North Pacific, which influences the tracks of tropical cyclones, leading to more tropical cyclones over the East ChinaSea but fewer over the South China Sea. Wang and Fan(2006)reported a significant negative correlationbetween the summer(June-September)SAM and typhoon frequency in the western North Pacific. Thisnegative correlation arises because the positive phaseof the boreal summer SAM usually results in enhancedvertical shear of zonal wind and cooler SST througha meridional teleconnection pattern, and these conditions do not favor the genesis and development oftyphoons.

In Africa, the SAM can modulate the behavior ofthe West African monsoon and precipitation over theSahel. Sun et al. (2010)found that when the borealspring(March-April)SAM is in positive phase, thetropical SST in the South Atlantic is warmer, thuschanging the gradient of wet static energy betweenGuinea and the tropical Atlantic. This changed gradient of wet static energy is important to the northward onset of the West African monsoon, and leadsto heavier precipitation over the Sahel in the earlysummer. The positive feedback between the precipitation and soil humidity favors the maintenance ofthese precipitation anomalies throughout the borealsummer(June-September).

In North America, the positive phase of borealspring(April-May)SAM usually corresponds to aweaker North American summer monsoon and decreased precipitation. Sun(2010)proposed a mechanism for the above linkage: the positive phase of borealspring SAM generally corresponds to warmer SST overthe tropical Atlantic in spring and the following summer(July-September), which influences the Bermudahigh and the North American monsoon and precipitation.

In addition to its effect on the atmosphere, theSAM could also regulate ocean circulation and corresponding oceanic variables in the NH. For example, Gong et al. (2009)found that the austral winter(August)SAM is positively related to the content of strontium(Sr)in coral reefs in the South China Sea, whichcan be considered as an indicator for SST. Marini et al. (2011)conducted a 500-yr numerical simulation and explored the driving effect of the SAM on the Atlanticmeridional overturning circulation(AMOC). Their results showed that the AMOC is related to the SAMon several timescales. On the decadal scale, an enhanced AMOC lags the positive phase of the SAM by8 yr. The mechanism for this linkage involves the positive phase of the SAM leading easterly anomalies overNorth Atlantic(50°-70°N)by 1 yr through the persistence of SST. The easterly anomalies increase salinity in the upper 500 m of the ocean near Greenl and and Icel and, which leads to deepening of the oceanmixed layer in this region 4 yr later, causing the enhancement of ocean deep convection in North Atlantic, and thus strengthening the AMOC. On longer multidecadal scales, the SAM also modulates the strength ofthe AMOC through the northward propagation fromthe SH extratropics of the salinity anomalies causedby the SAM(Marini et al., 2011). 4. Influence of the SAM on climate in China4. 1 Impact of the SAM on the East Asiansummer monsoon(EASM) and precipitation in China

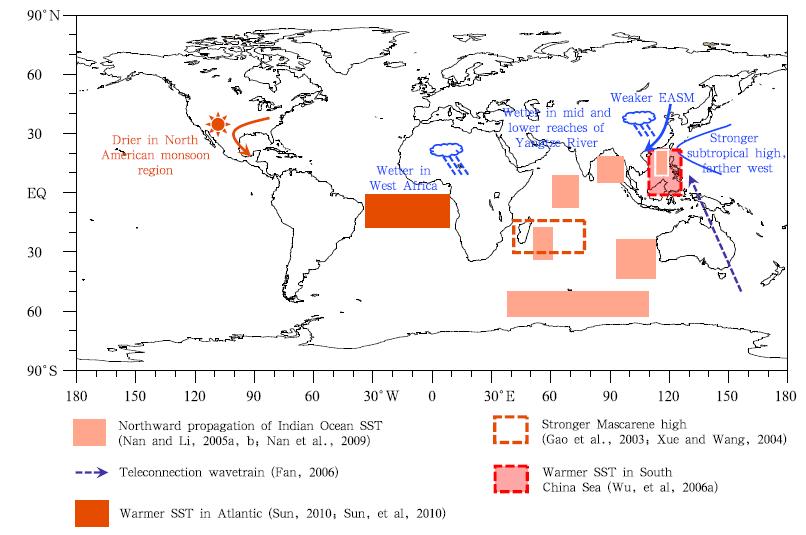

The SAM has significant impacts on the EASMsystem and related climatic features. Firstly, we consider the influence of the boreal spring SAM onboreal summer circulation in China. The positiveboreal spring(April-May)SAM is generally associated with a weakened EASM and increased summer(June-August)rainfall in the mid-lower reaches of theYangtze River valley(MLYRV)(Gao et al., 2003; Nan and Li, 2003, 2005a, b; Bao et al., 2006; Fan, 2006; Fan and Wang, 2006; Wu et al., 2006a; Nan et al., 2009; Li et al., 2011a, b). The studies cited above werein general agreement in identifying circulation anomalies over East Asia as the reason for this association. When the spring SAM is in positive phase, the EASMweakens, the western North Pacific subtropical highstrengthens and shifts westward, and ascending motion strengthens in the MLYRV, which leads to moreprecipitation.

However, there are still two key questions to beresolved about this linkage between the boreal springSAM and East Asian summer circulation. One is howthe boreal spring SAM signals persist in summer, and the other is how the anomalous signals propagate fromthe SH to the NH. The studies cited above provideddifferent explanations from various perspectives. Inresponse to the first question, Wu et al. (2006a)reported that when the spring(April-May)SAM is inpositive phase, SST is warmer offshore of China, witha decrease in the l and -sea thermal contrast, thus leading to a weaker EASM. As for the second question, the mechanism by which the anomalous signal propagates from the SH to the NH, Gao et al. (2003)pointed out that the SAM in May is positively correlated with a strong Mascarene high in the lower troposphere in July, which corresponds to an anomalouswestern North Pacific subtropical high.

Nan and Li(2005a, b)gave a comprehensive answer to the above two questions. They suggested thatthe spring SAM can regulate the EASM and rainfall in the MLYRV by the "ocean-atmosphere coupledbridge" process in the Indian Ocean. In detail, whenthe spring(April-May)SAM is in positive phase, SSTis warmer in the mid and high latitudes of the southernIndian Ocean, and this SST anomaly moves northwarduntil it reaches the northern Indian Ocean. In summer(June-August), the SST anomalies over the northernIndian Ocean modulate the atmospheric circulationthrough air-sea interactions, resulting in a weakenedEASM and a strengthened western North Pacific subtropical high.

Wu et al. (2006b, c)also explored the relationship between the SAM and the "drought-flood coexistence, " or the "drought-flood abrupt alternation" inthe MLYRV. Gao et al. (2012)pointed out that theprecursory signal for the Asian summer monsoon onset could be traced back to the SAM in the precedingboreal winter(December-February). Sun et al. (2013)indicated that the influence of the boreal spring SAMon summer rainfall in China shows decadal variations.

With regard to the influence of the boreal summerSAM on contemporary summer monsoon circulation and rainfall over China, Xue and Wang(2004)showedthat a positive summer(June-August)SAM is commonly associated with a strengthened Mascarene highin the lower troposphere, which leads to the Pacific-Japan(PJ)wave train from East Asia to the west coastof North America along the North Pacific Ocean, resulting in a stronger Meiyu(Baiu)from the YangtzeRiver valley in China to Japan(Xue, 2005). Wang and Fan(2005), using historical rainfall data, founda significant negative correlation between the borealsummer SAM and summer(June-August)rainfall inthe central region of North China, associated withthe anomalous convection in the equatorial westernPacific and the zonal wave train from western Europe to North China. Figure 2 summarizes the conclusions of research on the effect of the SAM onthe summer monsoon system and climate in all NHregions.

|

| Fig. 2. Influences of the boreal spring and summer SAM on boreal summer Northern Hemisphere climate, togetherwith the corresponding mechanisms(anomalies are shown for the positive SAM phase). |

Wu et al. (2009)reported that the positive borealautumn(September-November)SAM is commonlyfollowed by a weaker winter monsoon in China. Whenthe boreal autumn SAM is in positive phase, SST iswarmer over 30°-45°S. Such SST anomalies persistinto the boreal winter and weaken the Hadley cell, which gives a weaker winter(December-February)monsoon and warmer air temperatures in China. Theboreal autumn SAM leads the variability of air temperature over China by one season, indicating that theSAM provides a meaningful predictor signal for winter climate in China. The effect of the SAM on winterclimate is shown in Fig. 3. Qian(2014)analyzed therelationship between the boreal autumn SAM and winter(December-February)rainfall over South China, and reported a significant negative correlation betweenthese two variables on interannual scales. The positive(negative)autumn SAM is usually associated with asignificantly stronger(weaker)NH subtropical westerly jet, and abnormal northerly(southerly)wind overmost of China, leading to decreased(increased)rain-fall over South China.

|

| Fig. 3. Influences of the boreal autumn and winter SAM on boreal winter Northern Hemisphere climate, together withthe corresponding mechanisms(anomalies are shown for the positive SAM phase). |

Fan and Wang(2004)found that the preceding boreal winter(December-February) and spring(March-May)SAM had a significant negative correlation with the frequency of dust weather over NorthChina. Two possible mechanisms account for theabove correlation: a meridional teleconnection fromthe SH high latitudes to the NH high latitudes, and aregional teleconnection over the Pacific Ocean. Fan and Wang(2007)verified these teleconnection patterns using an atmospheric general circulation model(IAP9L-AGCM). Yue and Wang(2008)investigatedthe relationship between spring North Asian cycloneactivity and the SAM, revealing a significant positive correlation between the preceding boreal winter(December-February)SAM and spring(March-May)North Asian cyclones. When the preceding borealwinter SAM was in positive phase, springtime atmospheric convection in the tropical western Pacific intensified and the local Hadley circulation strengthened. As a result, the jet strengthened at high levels, favoring North Asian cyclone activity.

However, what is the mechanism for SAM persistence? Does the preceding boreal winter SAM havean effect on spring precipitation? Recent studies haveshown that the preceding boreal winter(December-February)SAM can regulate spring(March-May)precipitation over South China, and there is a significantnegative correlation between them(e. g., Zheng and Li, 2012). The "ocean-atmosphere coupled bridge"plays an important role in this cross-seasonal process. When the preceding boreal winter SAM is in positivephase, westerlies strengthen in the SH high latitudes and weaken in the SH midlatitudes. Sea surface evaporation and latent heat release respond to this changein surface wind speed, producing warm and cool SSTanomalies in the SH mid and high latitudes, respectively. The large heat capacity of the ocean allowsthe SST anomaly pattern to persist into the followingspring, leading to a series of atmospheric responses. For example, there is abnormal sinking and reducedhumidity over South China, and both of these conditions lead to less rainfall there. The preceding borealwinter SAM leads rainfall over South China by oneseason, indicating that the SAM can be used as a predictor for South China spring precipitation. Quantitative comparison of the rainfall derived from the prediction model based on the SAM with the observedrainfall shows that the model has predictive skills and has some ability to predict continuous drought overSouth China(Li et al., 2013). 5. The SAM and global climate change

Toward the end of the 20th century, the SAMintensity showed a significant linear positive trendin step with the background global warming. Thispositive trend is mainly attributed to the depletionof Antarctic ozone(Thompson and Solomon, 2002; Gillett and Thompson, 2003; Gillett et al., 2003, 2005; Karoly, 2003; Marshall et al., 2004; Shindell and Schmidt, 2004; Thompson et al., 2011; Zheng et al., 2013). Greenhouse gases are also external forcings forthe linear trend in the SAM(Shindell and Schmidt, 2004). A recent study showed similar strengtheningtrends in the SAM over the past 500 years, and theincreasing trend occurring toward the end of the 20thcentury is enhanced when superimposed over the natural variability(Zhang et al., 2013). Tropical SSTwarming also contributes to the positive trend of theSAM toward the end of the 20th century(Grassi et al., 2005).

The remarkable changes in the SAM associatedwith Antarctic ozone depletion have led to changes inmany climate variables in the SH polar region, including surface air temperature, precipitation, and sea ice. Both data diagnosis and numerical simulation haveshown that the SAM is the main driver of the SH climate change during the past half century. The changesin the SH climate variables in response to the SAM onlong-term scales are similar to those on interannualtimescales. The significant warming over the Antarctic Peninsula(Turner et al., 2005), the enhancement ofACC transport(Gupta and Engl and, 2006), and thechanges in the mixed layer depth(Sallee et al., 2010)are associated with the changes in the SAM. In fact, climate change caused by Antarctic ozone through itsmodulation of the SAM can extend northward even tothe SH subtropics and the tropics. For example, inconcert with the strengthening of the SAM, the SHstorm track shifts toward the Antarctic, and precipitation shifts from the midlatitudes toward high latitudes(more precipitation around 60° and 20°S, butless around 45°S)(Son et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2011; Polvani et al., 2011).

However, less attention has been paid to the possible influences of Antarctic ozone depletion on NH long-term climate change via its modulation of the SAM. Using a numerical simulation, Chen et al. (1998)verified that the NH climate responds to Antarctic ozone, but they did not provide a detailed mechanism for thisresponse. Investigation of how the long-term changesin the SAM caused by Antarctic ozone can regulateclimate in the NH will provide new clues for climatechange attribution analysis.

The possible recovery of Antarctic ozone in thefuture(Hu and Tung, 2003; Hu et al., 2009, 2011)will favor a decreasing trend in the SAM, opposite tothe predicted positive trend related to the increase ingreenhouse gases. Therefore, the evolution of the SAMin the future under various scenarios is a focus of climate change research. Projecting the future trend inthe SAM is helpful not only for underst and ing possible changes in atmospheric circulation over the SHmid to high latitudes, but also for climate downscaling projections for regions that are influenced by theSAM. The Coupled Model Intercomparison Project(CMIP)provides a possible way to evaluate changesin the SAM. Most CMIP3 models captured the observed rising trend in the SAM in austral summer(December-February)toward the end of the 20th century(Cai and Cowan, 2007; Fogt et al., 2009; Zhu and Wang, 2010), but the models containing time-varying ozone produced more significant trends. Simpkins and Karpechko(2012) and Zheng et al. (2013)estimated future SAM trends under different scenariosusing CMIP3 and CMIP5 models, respectively. Theirresults showed that, even allowing for the recovery ofAntarctic ozone, the SAM will maintain a rising trendin the future due to increased greenhouse gases.

The effect of a different background climate on theinfluence of the SAM on the SH and the NH climate isan important question worth thorough investigation. 6. ConclusionsIn recent years, the variability of the SAM and itsinfluence on climate have become new areas of climateresearch, and meaningful progress has been made bothin China and overseas. This paper has reviewed therelevant achievements reported in the recent literature and gives a concise description of the influence of theSAM on climate over the SH, China, and other NHregions. The main conclusions are as follows.

A systematic underst and ing of the influence ofthe SAM on the SH climate has been established. The SAM has a significant influence on the air-seaice coupled system in the SH. In general, the positivephase of the SAM corresponds to changes in the SHvertical circulation: anomalous ascent at high latitudes leads to anomalous adiabatic cooling and moreprecipitation; anomalous descent in the midlatitudesleads to less cloudiness and less precipitation. Because of the quasi-barotropic structure of the SAM, the dynamic and thermodynamic forcing caused bySAM-related sea surface wind results in responses ofthe SH extratropical SST and sea ice to the SAM. Inview of the zonally symmetric structure of the SAM, its influence on the SH extratropical precipitation and SST exhibits a large-scale zonal symmetry. However, the responses of the SH circulation and other climatevariables to the SAM also have regional features thatare zonally asymmetric, especially for sea ice and mixed layer depth. This zonal asymmetry is mainlyassociated with the meridional wind anomalies causedby the SAM.

Research on the influence of the SAM on theNH climate, especially the climate in China, has alsoachieved meaningful results. The boreal spring SAMinfluences the summer monsoon system in East Asia, West Africa, and North America, and modulates tropical cyclone activity over the western North Pacific. The boreal autumn SAM can influence the wintermonsoon and winter air temperature in China, whilethe preceding boreal winter SAM can influence springprecipitation in South China and dust frequency overNorth China. Air-sea coupled processes play an important role in the influence of the SAM on the NHclimate. Air-sea interaction is important to the storage of the SAM signal from one season to the next, inthe propagation of the signal from the SH to the NH, and in the release of the signal and its influence onatmospheric circulation. Given that the SAM signalleads climate anomalies by one season, it can be usedin seasonal prediction.

Although some progress has been made in underst and ing the influence of the SAM on the NH climate, there are many scientific questions deserving thoroughinvestigation. For example, much of the present literature focuses on the influence of the SAM on summermonsoon and summer climate, but less attention hasbeen paid to the SAM's influence on climate in otherseasons. Spring and autumn are transitional periodsbetween winter and summer. Warm and cold air flowsare frequently closely linked in spring and autumn, and climate in these two seasons is critical for agriculture. The literature concerning the influence of theSAM on the NH climate mainly explores the influence of the SAM on regional-scale climate. In view ofthe zonally symmetric structure of the SAM and itsregulation of the meridional overturning circulation, it is likely to play a role in modulating large-scaleclimate in the NH, a topic that remains poorly explored. In addition, research focusing on the influenceof the SAM on regional climate has mainly targetedon climate in the monsoon region and the SAM, whilepossible linkages between the SAM and climate inother regions are unclear. Aside from the SAM, theEl Ni~no-Southern Oscillation(ENSO), the NAO, and the NAM are also important modes that can regulatethe NH climate. Some studies have found a negativecorrelation between the SAM and the ENSO(Zhou and Yu, 2004; Gong et al., 2010, 2013; Ding et al., 2011, 2012), and the positive phase of the SAM com-monly corresponds to a La Ni~na event. The questionof how to distinguish both the influence of the SAM and its synergistic effects from other modes is worthfurther research.

| [1] | Ansell, T. J., C. J. C. Reason, I. N. Smith, et al., 2000: Evidence for decadal variability in southern Australian rainfall and relationships with regional pressure and sea surface temperature. Int. J. Climatol.,20, 1113-1129. |

| [2] | Bals-Elsholz, T. M., E. H. Atallah, L. F. Bosart, et al., 2001: The wintertime Southern Hemisphere split jet: Structure, variability, and evolution. J. Climate, 14, 4191-4215. |

| [3] | Bao Xuejun, Wang Panxing, and Qin Jun, 2006: Time lag correlation analyses of Antarctic Oscillations and Jianghuai Meiyu anomaly. J. Nanjing Inst. Meteor.,29, 348-352. (in Chinese) |

| [4] | Cai, W. J., and I. G. Watterson, 2002: Modes of interannual variability of the Southern Hemisphere circulation simulated by the CSIRO climate model. J. Climate, 15, 1159-1174. |

| [5] | —-, G. Shi, and Y. Li, 2005: Multidecadal fluctuations of winter rainfall over southwestern West Australia simulated in the CSIRO Mark 3 coupled model. Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, doi:10.1029/2005GL022712. |

| [6] | —-, and T. Cowan, 2006: SAM and regional rainfall in IPCC AR4 models: Can anthropogenic forcing account for southwestern West Australian winter rainfall reduction? Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, doi:10.1029/2006GL028037. |

| [7] | —-, and —-, 2007: Trends in Southern Hemisphere circulation in IPCC AR4 models over 1950-99: Ozone depletion versus greenhouse forcing. J. Climate, 20,681-693. |

| [8] | Chen Yuejuan, Zhang Hong, and Bi Xunqiang, 1998: Numerical experiment for the impact of the ozone hole over Antarctica on the global climate. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 15, 300-311. |

| [9] | Ding, Q. H., B. Wang, J. M. Wallace, et al., 2011: Tropical-extratropical teleconnections in boreal summer: Observed interannual variability. J. Climate, 24, 1878-1896. |

| [10] | —-, E. Steig, D. Battisti, et al., 2012: Influence of the tropics on the southern annular mode. J. Climate,25, 6330-6348. |

| [11] | Ding, R. Q., J. P. Li, S. G. Wang, et al., 2005: Decadal change of the spring dust storm in Northwest China and the associated atmospheric circulation. Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, doi: 10.1029/2004GL021561. |

| [12] | Fan, K., and H. J. Wang, 2004: Antarctic oscillation and the dust weather frequency in North China. Geophys. Res. Lett., 31, doi: 10.1029/2004GL019465. |

| [13] | Fan Ke, 2006: Atmospheric circulation anomalies in the Southern Hemisphere and summer rainfall over se J. Geophys., 49, 672-679. (in Chinese) |

| [14] | —- and Wang Huijun, 2006: Studies of the relationship between Southern Hemispheric atmospheric circulation and climate over East Asia. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 30, 402-412. (in Chinese) |

| [15] | —- and —-, 2007: Simulation of the AAO anomaly and its influence on the Northern Hemisphere circulation in boreal winter and spring. Chinese J. Geophys.,50, 397-403. (in Chinese) |

| [16] | Fan Lijun, Li Jianping, Wei Zhigang, et al., 2003: Annual variations of the Arctic Oscillation and the Antarctic Oscillation. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 27, 352-358. |

| [17] | Fauchereau, N., S. Trzaska, Y. Richard, et al., 2003: Sea-surface temperature co-variability in the southern Atlantic and Indian Oceans and its connections with the atmospheric circulation in the Southern Hemisphere. Int. J. Climatol., 23, 663-677. |

| [18] | Feng, J., J. P. Li, and Y. Li, 2010: Is there a relationship between the SAM and southwestern West Australian winter rainfall? J. Climate, 23, 6082-6089. |

| [19] | —-, —-, and H. L. Xu, 2013: Increased summer rainfall in Northwest Australia linked to southern Indian Ocean climate variability. J. Geophys. Res., 118,467-480. |

| [20] | Fogt, R. L., J. Perlwitz, A. J. Monaghan, et al., 2009: Historical SAM variability. Part II: Twentieth-century variability and trends from reconstructions, observations, and the IPCC AR4 models. J. Climate, 22,5346-5365. |

| [21] | Gao Hui, Xue Feng, and Wang Huijun, 2003: Influence of the interannual variability of the Antarctic Oscillation on Meiyu and its predicting significance. Chin. Sci. Bull., 48(S2), 87-92. (in Chinese) |

| [22] | —-, Liu Yunyun, Wang Yongguang, et al., 2012: A new precursor signal for the onset of Asian summer monsoon: The boreal winter Antarctic Oscillation. Chin. Sci. Bull., 57, 3516-3521. (in Chinese) |

| [23] | Gillett, N. P., and D. W. J. Thompson, 2003: Simulation of recent Southern Hemisphere climate change. Science, 302, 273-275. |

| [24] | —-, M. R. Allen, and K. D. Williams, 2003: Modelling the atmospheric response to doubled CO2 and depleted stratospheric ozone using a stratosphereresolving coupled GCM. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 129, 947-966. |

| [25] | —-, R. J. Allan, and T. J. Ansell, 2005: Detection of external influence on sea level pressure with a multimodel ensemble. Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, doi:10.1029/2005GL023640. |

| [26] | —-, T. D. Kell, and P. D. Jones, 2006: Regional climate impacts of the southern annular mode. Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, doi: 10.1029/2006GL027721. |

| [27] | Gnanadesikan, A., and W. Hallberg, 2000: On the relationship of the circumpolar current to Southern Hemisphere winds in coarse-resolution ocean models. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 30, 2013-2034. |

| [28] | Gong, D. Y., and S. W. Wang, 1999: Definition of Antarctic Oscillation index. Geophys. Res. Lett., 26, 459-462. |

| [29] | —-, S. J. Kim, and C. H. Ho, 2009: Arctic and Antarctic Oscillation signatures in tropical coral proxies over the South China Sea. Ann. Geophys., 27, 1979-1988. |

| [30] | Gong, T. T., S. B. Feldstein, and D. H. Luo, 2010: The impact of ENSO on wave breaking and southern annular mode events. J. Atmos. Sci., 67, 2854-2870. |

| [31] | —-, —-, and —-, 2013: A simple GCM model study on the relationship between ENSO and the southern annular mode. J. Atmos. Sci., 70, 1821-1832. |

| [32] | Gong Daoyi and Wang Shaowu, 1998: Antarctic Oscillation. Chin. Sci. Bull., 43, 296-301. (in Chinese) |

| [33] | Gonzalez, M. H., and C. S. Vera, 2010: On the interannual wintertime rainfall variability in the Southern Andes. Int. J. Climatol., 30, 643-657. |

| [34] | Grassi, B., G. Redaelli, and G. Visconti, 2005: Simulation of polar Antarctic trends: Influence of tropical SST. Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, doi: 10.1029/2005GL023804. |

| [35] | Gupta, A. S., and M. H. England, 2006: Coupled oceanatmosphere-ice response to variations in the southern annular mode. J. Climate, 19, 4457-4486. |

| [36] | Hall, A., and M. Visbeck, 2002: Synchronous variability in the Southern Hemisphere atmosphere, sea ice, and ocean resulting from the annular mode. J. Climate, 15, 3043-3057. |

| [37] | Hendon, H. H., D. W. J. Thompson, and M. C. Wheeler, 2007: Australian rainfall and surface temperature variations associated with the Southern Hemisphere annular mode. J. Climate, 20, 2452-2467. |

| [38] | Hennessy, K. J., R. Suppiah, and C. M. Page, 1999: Australian rainfall changes, 1910-1995. Aust. Meteor. Mag., 48, 1-13. |

| [39] | Ho, C. H., J. H. Kim, H. S. Kim, et al., 2005: Possible influence of the Antarctic Oscillation on tropical cyclone activity in the western North Pacific. J. Geophys. Res., D19104, doi: 10.1029/2005JD005766. |

| [40] | Hu, Y. Y., and K. Tung, 2003: Possible ozone-induced long-term changes in planetary wave activity in late winter. J. Climate, 16, 3027-3038. |

| [41] | —-, Y. Xia, and Q. Fu, 2011: Tropospheric temperature response to stratospheric ozone recovery in the 21st century. Atmos. Chem. Phys., 11, 7687-7699. |

| [42] | Hu Yongyun, Xia Yan, Gao Mei, et al., 2009: Stratospheric temperature changes and ozone recovery in the 21st century. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 23, 263-275. |

| [] | Kang, S. M., L. M. Polvani, J. C. Fyfe, et al., 2011: Impact of polar ozone depletion on subtropical precipitation. Science, 332, 951-954. |

| [43] | Karoly, D. J., 2003: Ozone and climate change. Science,302, 236-237. |

| [44] | Kwok, R., and J. C. Comiso, 2002: Spatial patterns of variability in Antarctic surface temperature: Connections to the Southern Hemisphere annular mode and the Southern Oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett.,29, 50-1-50-4. |

| [45] | Lefebvre, W., H. Goosse, R. Timmermann, et al., 2004: Influence of the Southern Annular Mode on the sea ice-ocean system. J. Geophys. Res., 109, doi:10.1029/2004JC002403. |

| [46] | —-, and —-, 2005: Influence of the southern annular mode on the sea ice-ocean system: The role of the thermal and mechanical forcing. Ocean Sci., 1, 145-157. |

| [47] | Li, J. P., and J. X. L. Wang, 2003: A modified zonal index and its physical sense. Geophys. Res. Lett.,30, doi: 10.1029/2003GL017441. |

| [48] | Li Jianping, 2005a: Coupled air-sea oscillations and climate variations in China. Climate and Environmental Evolution in China (First Volume). Qin, D., Ed., China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 324-333. (in Chinese) |

| [49] | —-, 2005b: Physical nature of the Arctic Oscillation and its relationship with East Asian atmospheric circulation. Air-Sea Interaction and Its Impacts on China Climate. Yu Yongqiang, Chen Wen, et al., Eds., China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 169-176. (in Chinese) |

| [50] | —-, Wu Guoxiong, Hu Dunxin, et al., 2011a: OceanAtmosphere Interaction over the Joining Area of Asia and Indian-Pacific Ocean and Its Impact on the Short-Term Climate Variation in China (Volume I). China Meteorological Press, 1-516. (in Chinese) |

| [51] | —-, —-, —-, et al., 2011b: Ocean-Atmosphere Interaction over the Joining Area of Asia and IndianPacific Ocean and Its Impact on the Short-Term Climate Variation in China (Volume II). China Meteorological Press, 517-1081. (in Chinese) |

| [52] | —-, Ren Rongcai, Qi Yiquan, et al., 2013: Progress in air-land-sea interactions in Asia and their role in global and Asian climate change. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 37, 518-538. (in Chinese) |

| [53] | Li Xiaofeng and Li Jianping, 2010: Propagation characteristics of atmospheric circulation anomalies of sub-monthly Southern Hemisphere annular mode. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 34, 1099-1113. (in Chinese) |

| [54] | —- and —-, 2012: Analysis of the quasi-geostrophic adjustment process of the Southern Hemisphere annular mode. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 36, 755-768. (in Chinese) |

| [55] | Li, Y., W. J. Cai, and E. P. Campbell, 2005: Statistical modeling of extreme rainfall in southwestern West Australia. J. Climate, 18, 852-863. |

| [56] | Limpasuvan, V., and D. L. Hartmann, 1999: Eddies and the annular modes of climate variability. Geophys. Res. Lett., 26, 3133-3136. |

| [57] | Lorenz, D. J., and D. L. Hartmann, 2001: Eddy-zonal flow feedback in the Southern Hemisphere. J. Atmos. Sci., 58, 3312-3327. |

| [58] | Lu Riyu, Li Ying, and Dong Buwen, 2007: Arctic Oscillation and Antarctic Oscillation in internal atmospheric variability with an ensemble AGCM simulation. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 24, 152-162. |

| [59] | Mao, R., D. Y. Gong, J. Yang, et al., 2013: Is there a linkage between the tropical cyclone activity in the southern Indian Ocean and the Antarctic Oscillation? J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos., 118, 8519-8535. |

| [60] | Marini, C., C. Frankignoul, and J. Mignot, 2011: Links between the southern annular mode and the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation in a climate model. J. Climate, 24, 624-640. |

| [61] | Marshall, G. J., 2003: Trends in the southern annular mode from observation and reanalysis. J. Climate,16, 4134-4143. |

| [62] | —-, 2007: Half-century seasonal relationships between the southern annular mode and Antarctic temperatures. Int. J. Climatol., 27, 373-383. |

| [63] | —-, P. A. Stott, J. Turner, et al., 2004: Causes of exceptional atmospheric circulation changes in the Southern Hemisphere. Geophys. Res. Lett., 31, doi:10.1029/2004GL019952. |

| [64] | —-, and W. M. Connolley, 2006: Effect of changing Southern Hemisphere winter sea surface temperatures on southern annular mode strength. Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, doi: 10.1029/2006GL026627. |

| [65] | Meneghini, B., S. Ian, and I. N. Smith, 2007: Association between Australian rainfall and the southern annular mode. Int. J. Climatol., 27, 109-121. |

| [66] | Meredith, M. P., and C. W. Hughes, 2004: On the wind forcing of bottom pressure variability at Amsterdam and Kerguelen Islands, southern Indian Ocean. J. Geophys. Res., 109, doi: 10.1029/2003JC002060. |

| [67] | —-, P. L. Woodworth, C. W. Hughes, et al., 2004: Changes in the ocean transport through Drake Passage during the 1980s and 1990s, forced by changes in the southern annular mode. Geophys. Res. Lett.,31, doi: 10.1029/2004GL021169. |

| [68] | Mo, K. C., 2000: Relationships between low-frequency variability in the Southern Hemisphere and sea surface temperature anomalies. J. Climate, 13, 3599-3610. |

| [69] | Nan, S. L., and J. P. Li, 2003: The relationship between the summer precipitation in the Yangtze River valley and the boreal spring Southern Hemisphere annular mode. Geophys. Res. Lett., 30, doi:10.1029/2003GL018381. |

| [70] | —-, —-, X. J. Yuan, et al., 2009: Boreal spring Southern Hemisphere annular mode, Indian Ocean sea surface temperature, and East Asian summer monsoon. J. Geophys. Res., 114, D02103, doi:10.1029/2008JD010045. |

| [71] | Nan Sulan and Li Jianping, 2005a: The relationship between the summer precipitation in the Yangtze River valley and the boreal spring Southern Hemisphere annular mode I: Basic facts. Acta Meteor. Sinica,63, 837-846. (in Chinese) |

| [72] | —- and —-, 2005b: The relationship between the summer precipitation in the Yangtze River valley and the boreal spring Southern Hemisphere annular mode II. The role of the Indian Ocean and South China Sea as an oceanic bridge. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 63, 847-856. (in Chinese) |

| [73] | Polvani, L. M., D. W. Waugh, G. J. P. Correa, et al., 2011: Stratospheric ozone depletion: The main driver of20th-century atmospheric circulation changes in the Southern Hemisphere. J. Climate, 24, 795-812. |

| [] | Qian Zhuolei, 2014: The impact of autumn Antarctic Oscillation (AAO) on winter precipitation in southern China. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 38, 190-200. (in Chinese) |

| [74] | Raphael, M. N., W. Hobbs, and I. Wainer, 2011: The effect of Antarctic sea ice on the Southern Hemisphere atmosphere during the southern summer. Climate Dyn., 36, 1403-1417. |

| [75] | Reason, C. J. C., and M. Rouault, 2005: Links between the Antarctic Oscillation and winter rainfall over western South Africa. Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, doi:10.1029/2005GL022419. |

| [76] | Renwick, J. A., 2002: Southern Hemisphere circulation and relations with sea ice and sea surface temperature. J. Climate, 15, 3058-3068. |

| [77] | Rogers, G. T., 1981: The North-Pacific oscillation. J. 7. |

| [78] | Sallee, J. B., K. G. Speer, and S. R. Rintoul, 2010: Zonnally asymmetric response of the Southern Ocean mixed-layer depth to the southern annular mode. Nat. Geosci., 3, 273-279. |

| [79] | Schneider, D. P., E. J. Steig, and J. C. Comiso, 2004: Recent climate variability in Antarctica from satellitederived temperature data. J. Climate, 17, 1569-1583. |

| [80] | Shindell, D. T., and G. A. Schmidt, 2004: Southern Hemisphere climate response to ozone changes and greenhouse gas increase. Geophys. Res. Lett., 31, doi: 10.1029/2004GL020724. |

| [81] | Simpkins, G. R., and A. Y. Karpechko, 2012: Sensitivity of the southern annular mode to greenhouse gas emission scenarios. Climate Dyn., 38, 563-572. |

| [82] | Son, S. W., N. F. Tandon, L. M. Polvani, et al., 2009: Ozone hole and Southern Hemisphere climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, doi:10.1029/2009GL038671. |

| [83] | Song, J., W. Zhou, C. Y. Li, et al., 2009: Signature of the Antarctic oscillation in the Northern Hemisphere. Meteor. Atmos. Phys., 105, 55-67. |

| [84] | Song Jie and Li Chongyin, 2009: The linkages between the Antarctic Oscillation and the Northern Hemisphere circulation anomalies. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 33, 847-858. (in Chinese) |

| [85] | Sun, C., and J. P. Li, 2012: Space-time spectral analysis of the Southern Hemisphere daily 500-hPa geopotential height. Mon. Wea. Rev., 140, 3844-3856. |

| [86] | Sun, J. Q., H. J. Wang, and W. Yuan, 2010: Linkage of the boreal spring Antarctic Oscillation to the West African summer monsoon. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan,88(1), 15-28. |

| [87] | Sun Dan, Xue Feng, and Zhou Tianjun, 2013: Influence of Southern Hemisphere circulation on summer rainfall in China under various decadal backgrounds. Climatic Environ. Res., 18, 51-62. (in Chinese) |

| [88] | Sun Jianqi, 2010: Possible impact of the boreal spring American summer monsoon. Atmos. Ocean. Sci. Lett., 3, 232-236. |

| [89] | Thompson, D. W. J., and J. M. Wallace, 1998: The Arctic oscillation signature in the wintertime geopotential height and temperature fields. Geophys. Res. Lett., 25, 1297-1300. |

| [90] | —-, and —-, 2000: Annular modes in the extratropical circulation. Part I: Month-to-month variability. J. Climate, 13, 1000-1016. |

| [91] | —-, —-, and G. C. Hegerl, 2000: Annular modes in the extratropical circulation. Part II: Trends. J. Climate, 13, 1018-1036. |

| [92] | —-, and S. Solomon, 2002: Interpretation of recent mate change. Science, 296,895-899. |

| [93] | —-, and D. J. Lorenz, 2004: The signature of the annular modes in the tropical troposphere. J. Climate, 17,4330-4342. |

| [94] | —-, S. Solomon, P. J. Kushner, et al., 2011: Signatures of the Antarctic ozone hole in Southern Hemisphere surface climate change. Nat. Geosci., 4, 741-749. |

| [95] | Turner, J., S. R. Colwell, G. J. Marshall, et al., 2005: Antarctic climate change during the last 50 years. Int. J. Climatol., 25, 279-294. |

| [96] | Walker, G. T., and E. W. Bliss, 1932: World weather. V. c., 4, 53-84. |

| [97] | Wallace, J. M., and D. S. Gutzler, 1981: Teleconnections in the geopotentialheight field during the Northern Hemisphere winter. Mon. Wea. Rev., 109, 784-812. |

| [] | Wang, H. J., and K. Fan, 2005: Central-north China precipitation as reconstructed from the Qing dynasty: Signal of the Antarctic Atmospheric Oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, L24705, doi: 10.1029/2005GL024562. |

| [98] | Wang Huijun and Fan Ke, 2006: The relationship between typhoon frequency over western North Pacific and the Antarctic Oscillation. Chin. Sci. Bull., 51,2910-2914. (in Chinese) |

| [99] | Watterson, I. G., 2000: Southern midlatitude zonal wind vacillation and its interaction with the ocean in GCM simulations. J. Climate, 13, 562-578. |

| [100] | —-, 2001: Zonal wind vacillation and its interaction with the ocean: Implications for interannual variability and predictability. J. Geophys. Res., 106, 23965-23975. |

| [101] | Wu, Z. W., J. P. Li, J. H. He, et al., 2006c: Occurrence of droughts and floods during the normal summer monsoons in the mid and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Geophys. Res. Lett., 33, doi:10.1029/2005GL024487. |

| [102] | —-, —-, B. Wang, et al., 2009: Can the Southern Hemisphere annular mode affect China winter monsoon? J. Geophys. Res., 114, doi: 10.1029/2008JD011501. |

| [103] | Wu Zhiwei, He Jinhai, Han Guirong, et al., 2006a: The relationship between Meiyu in the mid and lower reaches of the Yangtze river valley and the boreal spring Southern Hemisphere annular mode. J. Trop. Meteor., 22, 79-85. (in Chinese) |

| [104] | —-, Li Jianping, He Jinhai, et al., 2006b: The large-scale atmospheric singularities and summer long-cycle droughts-floods abrupt alternation in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Chin. Sci. Bull., 50, 2027-2034. |

| [105] | Xue, F., and H. J. Wang, 2004: Interannual variability of Mascarene high and Australian high and their influences on East Asian summer monsoon. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan, 82, 1173-1186. |

| [106] | Xue Feng, 2005: Influence of the southern circulation on East Asian summer monsoon. Climatic Environ. Res., 10, 401-408. (in Chinese) |

| [107] | Yuan, X. J., and E. Yonekura, 2011: Decadal variability in the Southern Hemisphere. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 116, doi: 10.1029/2011JD015673. |

| [108] | Yue Xu and Wang Huijun, 2008: The springtime North ity index and the southern annular mode. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 25, 673-679. |

| [109] | Zhang, Y., X. Q. Yang, Y. Nie, et al., 2012: Annular mode-like variation in a multilayer quasigeostrophic model. J. Atmos. Sci., 69, 2940-2958. |

| [110] | Zhang, Z. Y., D. Y. Gong, S. J. Kim, et al., 2013: Is the Antarctic oscillation trend during the recent decades unusual? Antarctic Sci. , 26, 445-451. |

| [111] | Zhang Wenxia and Meng Xiangfeng, 2011: Interannual variability of the mesoscale eddy kinetic energy in the Antarctic circumpolar current region and its translation mechanism. Chinese J. Polar Res., 23,42-48. (in Chinese) |

| [112] | Zhang Ziyin, Gong Daoyi, He Xuezhao, et al., 2010: Antarctic Oscillation index reconstruction since 1500 AD and its variability. Acta Geographica Sinica, 65,259-269. (in Chinese) |

| [113] | Zheng, F., J. P. Li, R. Clark, et al., 2013: Simulation and projection of the Southern Hemisphere annular mode in CMIP5 models. J. Climate, 26, 9860-9879. |

| [114] | Zheng Fei and Li Jianping, 2012: Impact of preceding boreal winter Southern Hemisphere annular mode on spring precipitation over South China and related mechanism. Chinese J. Geophys., 55, 3542-3557. (in Chinese) |

| [115] | Zhou, T. J., and R. C. Yu, 2004: Sea-surface temperature induced variability of the southern annular mode in an atmospheric general circulation model. Geophys. Res. Lett., 31, L24206, doi: 10.1029/2004GL021473. |

| [116] | Zhu Yali and Wang Huijun, 2010: The Arctic and Antarctic Oscillations in the IPCC AR4 coupled models. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 24, 176-188. |

2014, Vol. 28

2014, Vol. 28