The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- TAO Zuyu, XIONG Qiufen, ZHENG Yongguang. 2014.

- Overview of Advances in Synoptic Meteorology: Four Stages of Development in Conceptual Models of Frontal Cyclones

- J. Meteor. Res., 28(5): 849-858

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-014-3297-y

Article History

- Received March 3, 2014;

- in final form June 9, 2014

2 China Meteorological Administration Training Center, Beijing 100081;

3 National Meteorological Center, China Meteorological Administration, Beijing 100081

Synoptic meteorology is a scientifc discipline centered on weather forecasting. The word "synoptic"may be defned as "affording a general view of awhole." In this context, "affording a general view ofa whole" consists of synthesizing a variety of meteorological observ ations with the aim of predicting theweather. Synoptic meteorology has characteristics ofthe earth sciences, and its adv ance has been closelylinked with adv ances in observ ational capabilities. Thepractice of synoptic meteorology was initially characterized by scattered observ ations, which were oftenmade singleh and edly. The development of systematicobservation networks and the subsequent adv ances inremote sensing technology(including radar and satellite instrumentation)have facilitated the rapid development of synoptic meteorology. This co-evolutionillustrates the tight relationship between the adv anceof synoptic meteorology and the expansion of observ ational capabilities.

Synoptic meteorology is an extension of hydromechanics that involves applying hydromechanical principles to a specifc fuid(namely, the atmosphere). Theatmosphere is a slow-moving fuid with viscosity, compressibility, and phase transitions. These characteristics mean that the atmosphere has a high degree ofcomplexity. Li(2011)divided the history of hydromechanics into four stages:(1)ancient hydromechanicsbased on practical experience;(2)classical hydromechanics based on Newtonian mechanics(including extensions to continuous media);(3)neoteric hydromechanics based on physical insight; and (4)contemporary hydromechanics based on modern technology.The history of synoptic meteorology can also be divided into four analogous stages: "ancient" synopticmeteorology, classical synoptic meteorology, neotericsynoptic meteorology, and contemporary synoptic meteorology.

Objects studied in synoptic meteorology includeboth mid- and low-latitude weather, including largescale baroclinic weather systems and mesoscale convective systems. Synoptic meteorology uses diagnostic and analytic methods, as well as numerical simulations. The purview of synoptic meteorology is broad, so it is practically impossible for an article to discussthese topics comprehensively. However, a review of thehistory of synoptic meteorology reveals that frontal cyclones in mid and high latitudes have been a consistenttopic of research from the early days of synoptic meteorology to the present.

We use the evolution of frontal cyclone conceptualmodels to summarize the historical adv ance of synoptic meteorology, with reference to the four stages ofadv ance in hydromechanics and the historical development of meteorological observ ational techniques. 2. "Ancient" synoptic meteorology: The FitzRoy modelThe Frst conceptual model of extratropical frontal

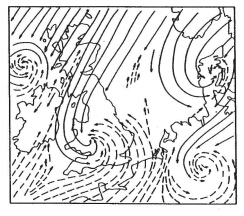

cyclones was developed by Robert FitzRoy in 1863.This model(shown in Fig. 1)represents the embryonicstage of synoptic meteorology, and is one of the mostimportant achievements of "ancient" synoptic meteorology. FitzRoy sailed around the world with CharlesDarwin as a captain in the British Royal Navy, and later achieved the rank of Vice-Admiral. Based onrecords of winds and temperatures that he recorded inhis logbook over many years, FitzRoy concluded thata storm is an anti-clockwise vortex composed of cold and warm air masses. Figure 1 refects his underst and ing that the occurrence of a cyclone is closely relatedto the temperature difference between these warm and cold air masses, and highlights the confrontation between strong fows of warm and cold air within thestorm. This model also shows penetration of the warm and cold air masses by cold and warm airfows, as wellas wide regions of calm winds between the cold and warm airfows. Many of the phenomena described inFig. 1 can be clearly seen in modern satellite watervapor images. Figure 1, which is based entirely on observ ations made without the assistance of radio communications or real-time weather maps, refects the remarkable depth of FitzRoy's underst and ing of changesin winds and temperatures.

|

| Fig. 1. Conceptual model of extratropical cyclones developed by Admiral FitzRoy in 1863. The fgure shows ananti-clockwise vortex with both cold(solid lines) and warm(dashed lines)air masses. [Adapted from Petterssen, 1958(Chinese version)] |

It is worth pointing out that the cores of some ofthe cyclones shown in Fig. 1 contain both warm and cold air masses, while others contain only warm airmass. These sketches appear to contradict the conceptual cyclone model developed during the classicalstage of synoptic meteorology, which held that the coreof a cyclone in the occlusion stage is composed entirelyof cold air; however, they are consistent with the modern conceptual model of explosive cyclones. This pointis discussed below. The warm-core cyclone structurein the cyclone model drawn by FitzRoy is by no meansfortuitous; on the contrary, it is drawn meticulously and intentionally from the basis of his personal observations. This model is therefore an outst and ing example of the "ancient" stage of synoptic meteorology, which was largely based on practical experience. 3. Classical synoptic meteorology: The Norwegian model

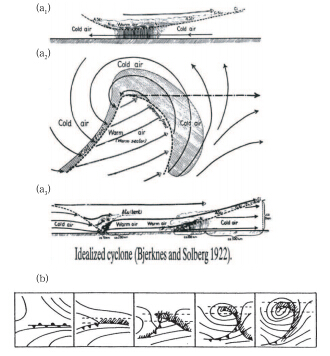

The Norwegian conceptual model of extratropicalcyclones is summarized in Fig. 2. Developed approximately 100 yr ago by Bjerknes and Solberg(1922), this model represents the achievements of the classical stage of synoptic meteorology. This model differsfrom the "ancient" cyclone model in that it treats thefront as a three-dimensional core and highlights theinseparability of the front and the cyclone. The frontdetermines the three-dimensional structure of the cyclone, the distribution of rain and clouds within thestorm, and even the entire life cycle of the cyclone.Fig. 2.(a1-a3)F rontal structure and (b)life cycle of theNorwegian cyclone model. [Adapted from Bjerknes and Solberg, 1922]This classical cyclone model, which is often calledthe frontal cyclone model, established the core ideathat baroclinicity is the mechanism by which weatherchanges in mid and high latitudes.

Despite the lack of upper-air observ ations(radiosoundings)at the time of its development, the classical cyclone model is a three-dimensional model. It includes the horizontal(Fig. 2a2) and vertical(Figs. 2a1 and 2a3)motions of air at upper levels, as well as thedistributions of rain and clouds. Figure 2a3shows avertical section across the warm and cold fronts, whileFig. 2a1shows a cross-section of the northern part ofthe cyclone that does not intersect the surface front.There is also an upper-level front with a warm air massabove and a cold air mass below, but this front doesnot touch the ground. This model regards the front asa substantial surface that determines the direction ofvertical motion and the distribution of rain and clouds.The blocking effect of the cold front causes sinking ofcold air to the rear of the front, while the impact effect of the cold front causes warm air to rise alongthe leading edge. The warm front causes warm air toclimb up the underlying surface. The practice of inferring the upper-level structure of a cyclone from surfaceobserv ations is called indirect upper-level meteorology(aerology).

|

| Fig. 2.(a1-a3)F rontal structure and (b)life cycle of theNorwegian cyclone model. [Adapted from Bjerknes and Solberg, 1922] |

Figure 2b shows the life cycle of the frontal cyclone. The cyclone occurs along a static front in theeast-west trough, with the center of the cyclone located at the turning point of this disturbance. Thecold front moves eastward and southward as the cyclone deepens, while the warm sector of the cyclonegradually contracts until it disappears. The warm airascends to upper levels, where it eventually forms anoccluded cyclone.

Nearly all textbooks on synoptic meteorology introduce this conceptual model, but it contains a serious faw. F rom the hydromechanical point of view, continuity is a basic characteristic of a fuid. The assumption that the front acts as a substantial surfacetherefore cannot be established in hydromechanics, because treating the front as a substantial surface createsa zeroth-order discontinuity in temperature that violates the continuity of the fuid. In reality, the frontis a transitional region between the cold and warmair masses with a strong temperature gradient. Thefront is therefore a discontinuity in the temperaturegradient(i.e., a frst-order discontinuity in temperature). Schultz and Vaughan(2011)have questionedthe very existence of the occlusion process in realitybased on the continuity principle. Although the treatment of the front as a substantial surface is not tenable, the distributions of rain and clouds predicted bythe Norwegian model still accord with observ ations.This model therefore still exerts profound infuenceson meteorologists today.4. Neoteric synoptic meteorology: The Chicago model

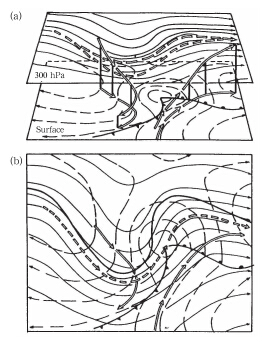

Similar to the neoteric stage of hydromechanics, the neoteric model of extratropical cyclones is basedon deep physical insight. This model, which we callthe Chicago model, is the three-dimensional baroclinicdisturbance model proposed by Palmen and Newton(1969). The establishment of an upper-air observ ation network led to the discovery of disturbances inthe westerly wind belt above surface cyclones(Fig. 3). The neoteric cyclone model is a three-dimensionalmodel that includes not only the surface cyclone butalso the anticyclone behind the cyclone. This modelcan therefore be called a baroclinic disturbance model.The upper-level trough is located behind the surfacecold front and tilts westward(backward)in the vertical direction. This vertical structure accords withboth hydrostatic balance and the thermal wind relationship. According to quasi-geostrophic theory, thethermal asymmetry of the backward-tilting baroclinicdisturbance indicates a developing disturbance. Thecold and warm advection corresponding to the cold and warm fronts act to enhance the amplitude ofthe upper-level disturbance(Holton, 1972; Tao et al., 2012).

|

| Fig. 3.(a)Three-dimensional stereograph and (b)twodimensional vertical cross-section from the model of frontalcyclones proposed by Palmen and Newton(1969). Solidlines show height contours at 300 hPa, while dashed linesshow isobars at the surface. Double-shafted arrows showtra jectories of cold and warm air near the cold front and their projections at surface. Double-dashed arrows showair parcel tra jectories at upper levels from the rear of thetrough to the front and their projections at 300 hPa. |

The most important aspect of this model is thatit gives three tra jectories of representative air parcel paths in a cyclone. Specifcally, this model speci-fes the tra jectories of warm air parcels ahead of thecold front, the tra jectories of cold air parcels behindthe cold front, and the tra jectories of upper-level airparcels from locations behind the trough to locationsahead of the ridge. The speed of vertical air motionin a large-scale weather system is very small, approximately 0.1% of the speed of horizontal wind. V ertical velocities are therefore very di±cult to observe directly. In the classical cyclone model, vertical motionis estimated by considering the front as a substantialsurface, which violates hydromechanical theory. F urthermore, the anafront and katafront systems foundin weather analyses cannot be reasonably explainedunder the assumption that fronts are substantial surfaces. Erik Palmen en and contemporaries of the Massachusetts Institute of T echnology advocated analysisof cyclones on isentropic surfaces. This type of analysis is based on the assumption that potential temperature is conserved over short periods. V ertical motion within the storm is then inferred by analyzingthe slopes of isentropic surfaces and the directions ofisentropic winds.

The representative tra jectories derived from theneoteric cyclone model refect a profound underst and ing of quasi-geostrophic dynamics in the large-scalecirculation. The tra jectories of sinking cold air and rising warm air shown in Fig. 3 refect the occurrenceof sinking motion with cold temperature advection and rising motion with warm temperature advection underquasi-geostrophic balance. Cold advection is related tocold fronts, while warm advection is related to warmfronts. Both of these tra jectories have distinct clockwise curv atures, and highlight that sinking motion isrelated to low-level divergence, while rising motion isrelated to upper-level divergence. The absolute magnitude of negative vorticity in diverging air parcels increases, so the curv ature of the tra jectories is anticyclonic. The tra jectories therefore refect both vertical motion under Dyne's mass-conservation principle and the relationship between divergence and relativevorticity articulated by the vorticity equation(i.e., divergence increases the absolute magnitude of negativevorticity).

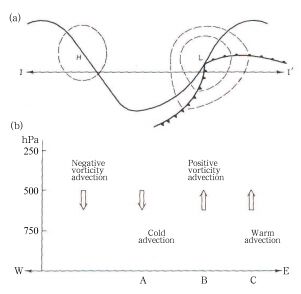

The baroclinic atmosphere includes an upperlevel westerly jet above the surface front. The windspeeds in this jet are much larger than the propagation speed of the disturbance. We can therefore inferthat upper-level air parcels must move from locationsbehind the trough to locations ahead of the trough. Asair parcels move from the trailing ridge to the trough, their vorticity changes from negative to positive. Thisincrease in air parcel vorticity must be related to convergence. This means that tra jectories behind thetrough must sink toward the surface(as shown in Fig. 3). By contrast, the vorticity of air parcels movingfrom the trough to the leading ridge must change frompositive to negative. This decrease of air parcel vorticity must be related to divergence, so tra jectories aheadof the trough must rise. This overall picture of air parcel motion is consistent with the relationship betweenvertical motion and the vertical derivative of vorticityadvection expressed in the quasi-geostrophic diagnostic equations. This three-dimensional baroclinic disturbance model based on observ ations and analyses(presented by Palmen en and Newton in the book Atmospheric Circulation Systems; Palmen and Newton, 1969)is consistent with the diagram(shown in Fig. 4)of the secondary circulation in a back-tilting baroclinic disturbance presented by Holton in his widelyused textbook An Intr oduction to Dynamic Meteorology(Holton, 1972). This consistency highlights theprofound underst and ing of dynamical theory that underpins the neoteric cyclone model.

|

| Fig. 4. Schematic diagram of the secondary circulationassociated with a developing baroclinic disturbance.(a)500-hPa(solid line) and 1000-hPa(dashed lines)geopotential height contours, and surface fronts.(b)Verticalprofle through line II'in(a), indicating the direction ofvertical motion. [Adapted from Holton, 1972] |

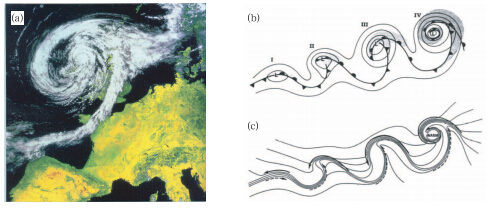

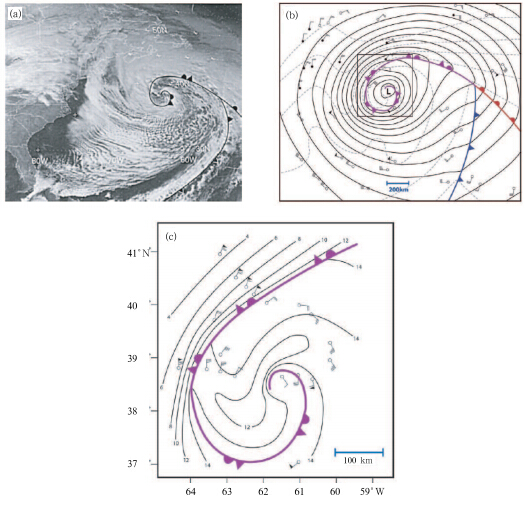

The popular application of satellite imagery in the1980s led to the discovery of spiral occluded frontalcloud belts in intensifying cyclones over the North Atlantic Ocean(Fig. 5a). Conceptual analysis(Figs. 5b and 5c) and scientifc observ ations(including dropsondes released from airplanes and buoy stations on theocean surface)as well as synoptic analysis(Figs. 6a-c)showed very strong temperature gradients on bothsides of the occluded front. These observ ations wereinconsistent with the thermal structure of the occludedfront predicted by the classical cyclone model, whichconsidered the front to be a substantial surface. Thecold front catches up to the warm front at the laststage of the cyclone life cycle, forming a so-called occluded front. The air masses on both sides of theoccluded front are cold, so the temperature contrastshould be small. The results of idealized numerical simulations of developing baroclinic disturbancesunder the primitive equations led to the development of a new cyclone conceptual model(Newton and Holopainen, 1990; Snyder et al., 1991). This modelfeatures a T-shaped frontal structure and a back-bentwarm front. Back-bent warm fronts are frequently observed during the last stage of the cyclone life cycle, particularly in explosive marine and continental cyclones. F or example, Xiong et al.(2013)showed theexistence of a back-bent warm front in a cyclone overMongolia.

|

| Fig. 5.(a)Spiral occluded frontal cloud belts in an intensifying cyclone over the North Atlantic Ocean.(b, c)Conceptualmodels of the life cycle of a marine extratropical cyclone. Step(I)shows the initial development, step(II)the frontalfracture, step(III)the back-bent warm front and frontal T-shape, and step(IV)the warm-core frontal occlusion.(b)Shows sea-level pressure(solid lines), fronts(bold lines), and the cloud distribution(shaded).(c)Shows temperature(solid lines) and cold and warm air currents(solid and dashed arrows, respectively). [F rom Newton and Holopainen, 1990; their Fig. 10.27] |

The contemporary and classical cyclone modelsare similar in that both indicate the co-existence ofwarm and cold fronts in the cyclone, and both breakcyclone development into four stages. However, unlike the classical model, the cold and warm fronts inthe center of the cyclone do not connect with eachother in the contemporary model. By contrast, thetwo fronts form a T-shaped front structure. The warmfront stretches westward and southward as the cyclonedevelops, and then twines in a spiral around the centerof the cyclone. A warm front that undergoes this typeof wrap-up process is called a back-bent warm front.Although the shape of this back-bent front is similarto that of the occluded front in the classical model, the back-bent warm front keeps its original temperature gradient. The characteristics of the back-bentfront are therefore entirely different from those of theoccluded front.

The backward bend of the warm front in the contemporary cyclone model means that some warm airis drawn into the center of the cyclone. This processwarms the air in the center of the cyclone relative tothe surrounding air, and thus leads to the formation ofa "warm core". This phenomenon was also describedin the "ancient" model developed by FitzRoy(Fig. 1). This indicates that the FitzRoy's model was bothcareful and (in many ways)comprehensive; however, the classical(Norwegian)model neglected the potential formation of a warm core. The reason for this oversight is related to the assumption that the front canbe treated as a substantial surface. In this case, theocclusion process means that the core area of the cyclone must be occupied entirely by cold air. Cold corecyclones do not exist in nature(Schultz and Vaughan, 2011).

|

| Fig. 6.(a)Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite 7(GOES-7)visible image at 1801 UTC 14 December1988 with frontal positions superimposed.(b)Surface isobars(solid black lines; interv al 4 hPa), isotherms(dashed graylines; interv al 4℃), and horizontal winds(pennant, full barb, and half-barb denote 25, 5, and 2.5 m s−1, respectively)at1800 UTC 14 December 1988. The positions of ships(open circles) and buoys(dots)are also shown.(c)Flight sectionat 300 m above sea level with ship, buoy, and dropsonde data included. Temperature(solid lines; interv al 2℃) and horizontal winds(as in(b))are also shown. The area of this fight section is shown as a solid rectangle in(b). [FromSchultz and Vaughan, 2011] |

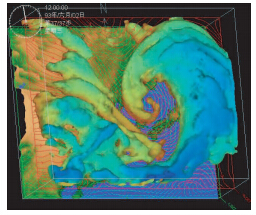

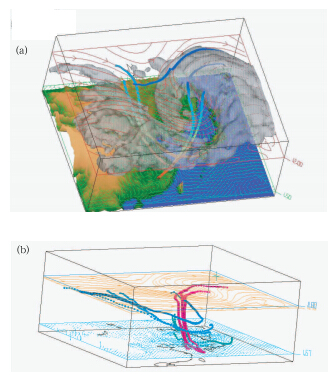

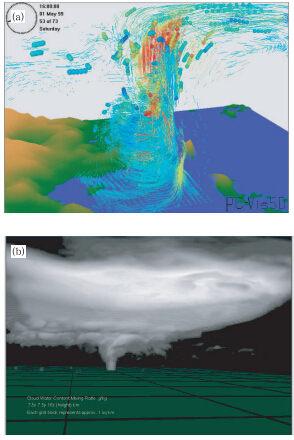

The development of a back-bent warm front and the formation of a warm core can be illustrated by using high-resolution numerical model simulations and modern computer visualization techniques(Fig. 7)( Wang et al., 1998). Three-dimensional air parceltra jectories can be calculated explicitly based on thedistribution of hourly winds(u, v, w), rather thaninferring them from physical insight as was done during construction of the neoteric cyclone model. Figure 8(Zhang et al., 2006)shows two groups of tra jectoriesthat roughly correspond to those shown in Fig. 3. Thefrst group of tra jectories corresponds to warm and wetair parcels that ascend to the upper troposphere fromsurface locations ahead of the cold front. The secondgroup corresponds to air parcels that are initially located behind the upper-level trough, which frst sink and then rise as they travel across the trough towardthe leading edge of the system. These two groups oftra jectories share many features in common with thetheoretical tra jectories shown in Fig. 3. Specifcally, the curv ature of the tra jectories shown in Fig. 3 is anticyclonic in the upper troposphere. The second groupof tra jectories shown in Fig. 8 sinks frst and then risesafter crossing the trough. The convergence and divergence of the simulated tra jectories highlight the strongrelationship between horizontal convergence and thedirection of vertical motion.

|

| Fig. 7. Cloud top stereograph of a simulated cyclone system at 0100 UTC 2 June 1993. The 0.1 g kg−1ice watercontent iso-surface is shown in color, and the wind feldsat 1.5- and 12-km altitudes are shown as green arrows and red streamlines, respectively. [From Wang et al., 1998 |

|

| Fig. 8.(a)As in Fig. 7, but including air parcel trajectories(shown as shaded strips). The shading indicatestemperatures at different levels, with red colors(at low levels)indicating higher temperatures than blue colors(upper levels).(b)Air parcel tra jectories. [F rom Zhang et al., 2006] |

The tra jectories shown here represent air parcelmovement in a developing cyclone and a strengtheningupper-level trough. The upper-level trough developsinto a cutoff low. The low-level warm front then bendsbackward, isolating the warm core. The complex dynamical processes that occur during this developmentare very di±cult to describe conceptually based solelyon physical underst and ing. Our current conceptualunderst and ing of extratropical cyclones owes much tothe development of computer technology and numerical modeling techniques.6. Discussion and concluding remarks

The rate of adv ance in synoptic meteorologyhighlights the complexity of atmospheric motions.Weather systems develop on multiple scales simultaneously, with interactions among subsystems of manydifferent scales. Although midlatitude cyclones arefundamentally large-scale baroclinic waves, latent heatfeedbacks caused by mesoscale precipitation also affect their development. A convective system over thetropical ocean with an initial scale of dozens of kilometers could develop into a tropical cyclone with a scaleof a thous and kilometers. Severe convective systemsin midlatitudes, which may also have scales of dozensof kilometers, can generate tornadoes with scales ofhundreds of meters. Studies of complicated nonlinearprocesses in the atmosphere are aided substantially bythe use of modern massive numerical simulations. Asexamples, Fig. 9a shows the three-dimensional motion inside a typhoon using a high-resolution numerical model based on the nonhydrostatic primitive equations( Wang et al., 1998), while Fig. 9b shows a simulation of the formation of a tornado below a severeconvective storm.

|

| Fig. 9.(a)Air parcel tra jectories from simulation of atyphoon system over the northern South China Sea on 1May 1999. Dashed lines show 3-h tra jectories, balls indicate the positions of air parcel tra jectories within 72 h, and colors indicate upward(red) and downward(blue)verticalvelocity. [FromWang et al., 1999].(b)Video screenshot ofa simulated tornado system. [Provided by Professor XueMing of University of Oklahoma] |

In a typhoon, warm and moist air containing largeamounts of unstable potential energy converges intothe typhoon at sea level from all directions and thenascends(dashed-line segments in Fig. 9a). This ascent releases large amounts of energy into the atmosphere, so upward motion becomes very strong(redline segments and balls in the core of the typhoon).The air diverges eastward and westward as it nears thetropopause, entering the subtropical upper-level westerly jet and the tropical easterly jet along the southside of the Tibetan high.

Tornadoes form at the base of strong convectivesystems with horizontal scales of dozens of kilometers and slow rotation. A large number of vortices withscales of dozens of meters each exist near the base othe cloud. The air pressure is relatively low withinthese vortices, so that pendent ob jects form in theseregions of low pressure at the base of the cloud. Thesesmall-scale vortices are generally relatively weak, withshort life spans. However, occasionally one of thesevortices will intensify: the central pressure of the vortex drops sharply, and the pear-shaped bulge at thebottom of cloud develops into a tornado that touchesdown on the ground.

These two examples above show that the numerical simulations that underpin the modern practiceof synoptic meteorology can almost "do anything"( Wang et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2007). The core task of contemporary synoptic meteorology is to grasp the physical scientifc underst and ingwithin the large amounts of data produced by numerical models. It is therefore necessary to learn and inherit the profound physical underst and ing gained during the neoteric stage of synoptic meteorology.

A conceptual model represents a generalization ofphysical knowledge. Figure 10 shows a schematic diagram published in Proceedings of the "ExtratropicalCyclones" Symposium organized in memory of ErikPalmen en by the American Meteorological Society in1988(Newton and Holopainen, 1990). It shows physical underst and ing originating from observ ations, theory, and diagnosis(Shapiro et al., 1999). The essenceof observ ations should be understood by using theory, while theory must be based on observ ations, and diagnosis links observ ations and theory. Even in moderntimes with the advent of powerful computers and bigdata, the continued adv ance of synoptic meteorologystill requires the careful combination of observ ations, theory, and diagnosis.

|

| Fig. 10.Physical underst and ing and conceptual representation through the union of theory, diagnosis, and observ ation. [F rom Shapiro et al., 1999] |

Acknowledgment: The authors wish to thankone of the reviewers who provided a very importantpaper(Schultz and Vanghan, 2011)published in Bulletin of the American Meteorologic al Society. This paper argues that modern research shows that occludedfronts and the occlusion process presented 90 yr agoin the Norwegian cyclone model do not exist in reality.Therefore, synoptic textbooks about the occlusionprocess need to be rewritten. This is one of the authors' motivations to write this paper.

| Bueh Cholaw, Ji Liren, and Cui Maochang, 2002: Energy balance of land surface process in the arid and semi-arid regions of China and its relation to the regional atmospheric circulation in summer. Climatic Environ. Res., 7, 61-73. (in Chinese) |

| Bjerknes, J., and H. Solberg, 1922: Life cycle of cyclones and the polar front theory of atmospheric circulation. Geophysisks Publikationer, 3, 3-18. |

| Chen Min, Tao Zuyu, Zheng Yongguang, et al., 2007: The front-related vertical circulation occurring in the pre-flooding season in South China and its interaction with MCS. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 65, 785-791. (in Chinese) |

| Holton, J. R., 1972: An Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology. Academic Press Inc., 45-260. |

| Li Jiachun, 2011: Flow everywhere. . Accessed on 1 November 2011. (in Chinese) |

| Newton, E. C., and E. O. Holopainen, 1990: Extratropical CyclonesThe Erik Palmén Memorial Volume. Amer. Meteor. Soc., Boston, USA, 187-188. |

| Palmen, E., and C. W. Newton, 1969: Atmospheric Circulation Systems. Academic Press, 60-210. Petterssen, S., (Translated by Cheng Chunshu), 1958:Weather Analysis and Forecasting. Science Press, Beijing, 138-139. (in Chinese) |

| Schultz, D. M., and G. Vaughan., 2011: Occluded fronts and the occlusion processA fresh look at conventional wisdom. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 92,443-466. |

| Shapiro, M., H. Wernli, J. W. Bao, et al., 1999: A planetary-scale to mesoscale perspective of the life cycles of extratropical cyclones: The bridge between theory and observations. The Life Cycles of Extratropical Cyclones, Shapiro, M. A., and S. Gronas, Eds., Amer. Meteor. Soc., 139-185. |

| Snyder, C., C. S. William, and R. A. Rotunno, 1991: Comparison of primitive-equation and semigeostrophic simulations of baroclinic wave. J. Atmos. Sci., 48, 2179-2194. |

| Tao Zuyu, Zhou Xiaogang, and Zheng Yongguang, 2012: Theoretical basis of weather forecasting: Quasigeostrophic theory summary and operational applications. Adv. Meteor. Sci. Technol., 2, 6-16. (in Chinese) |

| Wang, H. Q., K. H. Lao, and W. M. Chan, 1999: A PC based visualization system for coastal ocean and atmospheric modeling. Proceedings of the Sixth International Estuarine and Coastal Modeling Conference, New Orlean, USA, |

| Wang Hongqing, Zhang Yan, Tao Zuyu, et al., 1998: Visualization of large five-dimensional complex data. Prog. Nat. Sci., 8, 742-747. (in Chinese) |

| -, -, -, et al., 2000: Visualization of the numerical simulation of a Yellow Sea cyclone. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci., 11, 386-387. (in Chinese) |

| -, -, Zheng Yongguang, et al., 2004: Meteorological data visualization system. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 62,708-713. (in Chinese) |

| Xiong Qiufen, Niu Ning, and Zhang Lina, 2013: Analysis of the back-bent warm front structure associated with an explosive extratropical cyclone over land. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 71, 239-249. (in Chinese) |

| Zhang Wei, Tao Zuyu, Hu Yongyun, et al., 2006: A study on the dry intrusion of air flows from the lower stratosphere in a cyclone development. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin., 42, 61-67. (in Chinese) |

2014, Vol. 28

2014, Vol. 28