The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- CAI Ninghao, XU Xin, SONG Lili, BAI Lina, MING Jie, WANG Yuan. 2014.

- Dynamic Impact of the Vertical Shear of Gradient Wind on the Tropical Cyclone Boundary Layer Wind Field

- J. Meteor. Res., 28(1): 127-138

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-014-3058-y

Article History

- Received August 8, 2013;

- in final form November 20, 2013

2 Key Laboratory of Meteorological Disaster of Ministry of Education, Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, Nanjing 210044;

3 Public Meteorological Service Center, China Meteorological Administration, Beijing 100081;

4 Shanghai Typhoon Institute of China Meteorological Administration, Shanghai 200030

Over the past few decades, the prediction of tropical cyclone(TC)track has been significantly improved, yet there is still little progress in TC intensity forecasting. The intensity of TC is affected by manyfactors, such as TC internal dynamics, environmental flow, TC boundary layer(TCBL), and so on. Inrecent years, there is a growing concern in the vertical wind shear(VWS)of horizontal wind in the freeatmosphere, which may be associated with the TC intensity change.

VWS describes vertical shear of mean large-scalehorizontal wind, commonly measured as the differencebetween 200 and 850 hPa. It is usually considereddetrimental to the development of TC, as revealed bymany numerical and observational studies(McBride and Zehr, 1981; Frank and Richie, 1999). It used to beexplained by the ventilation effect(Riehl and Shafer, 1944; Gray, 1968; Merrill, 1988). However, based onthe theoretical analysis of a simple two-layer model, DeMaria(1996)argued that it was the VWS-inducedbaroclinic effect, rather than "ventilation" in the TCcore areas, that caused the negative correlation between VWS and TC intensity. Moreover, Bender(1997)suggested that the development of the asymmetric inflow and outflow would also affect the vertical distribution of convective heating and thus the TC intensity. Meanwhile, there are numerous studiesinvestigating the dependency of TC development onthe threshold value of VWS(e. g. , Gallina and Velden, 2002; Zehr, 2003; Chu and Wu, 2013; Shu et al. , 2013). These studies revealed that TCs develop accordinglywhen the VWSs drop below certain threshold value, and vice versa.

However, under certain conditions, it is foundthat VWS is conductive to the formation and development of TC in the low layer as well(Corbosiero and Molinari, 2002). For instance, Tuleya and Kurihara(1981)stated that cyclonic shear at low levels and anticyclonic shear at upper levels favored the emergence and development of TC, in accordance with their simulation results. The numerical study of Holl and Wang(1999)showed that VWS could slow down theintensification of TC, but it had no influence on themaximum potential intensity of TC. Indeed, Black etal. (2002)studied the relationship between the TCintensity and the local vertical shear in the TC innercore region, and found that TC could still intensify ormaintain its original intensity in an easterly shear of13{20 m s-1. The statistical analysis of Zeng et al. (2010)showed a similar result. The composite analysis of Yu et al. (2007)indicated that westerly(easterly)shear in the north(south)of TC was conduciveto TC intensification. Additionally, there are a number of studies indicating that the thermal structureof TC above the boundary layer(BL)was an important factor for TC intensity(e. g. , Velden and Smith, 1983; Wu and Liu, 1998; Wang et al. , 2013). Moreover, the thermal structure above TCBL is related tothe gradient wind distribution through thermal windbalance, and most of the TC wind field is nearly balanced(Willoughby, 1990). In these situations, the vertical shear of gradient wind(VSGW)can describe theVWS better. Therefore, differences in VSGW couldhave different effects on the TC intensity change.

In a word, agreement on the relationship betweenVWS and TC intensity has not yet been establishedin previous studies, and most of them concerned onlythe free atmosphere conditions. For the two famousclassical theories, namely, conditional instability ofthe second kind theory(CISK; Charney and Eliassen, 1964) and wind induced surface heat exchange theory(WISHE; Emanuel, 1986, 2003), both emphasized thetransport of energy and moisture through BL to thefree atmosphere. This indicated the important roleplayed by BL in the formation and development ofTC. It is therefore worth examining the structure ofTCBL wind fields, especially Ekman pumping at theBL top. Then, what is the impact of the VSGW onTCBL?

There have been prominent advances in the dynamics of the atmospheric boundary layer(ABL)sincethe 1900s. Ekman(1905)established a BL model featured by three-force balance, including the pressuregradient force, Coriolis force, and turbulent frictionforce in a local Cartesian coordinate system. Thismodel was widely used in the BL study for both atmosphere and ocean(e. g. , Brown, 1974). Panchev and Spassova(1987)noted that the inertial force, whichwas ignored in the classic Ekman theory, could not beomitted in two cases: 1)the BL is significantly nonuniform; 2)the system is of relatively strong vorticity. Hence, it is necessary to develop a moderately complicated BL model(Tan et al. , 2005).

In the 1980s, Wu and Blumen(1982) and Blumen and Wu(1983)introduced the geostrophic momentumapproximation theory(Hoskins and Breterton, 1972;Hoskins, 1975)into the BL model, and a four-forcebalance model was then established by incorporatingthe ageostrophic inertial force, which significantly advanced the classic Ekman theory. Nevertheless, theEkman theory is not applicable to TCBL, since its basic assumption(Rossby number is no more than 0. 4)is not satisfied in TCBL(Anthes, 1971). To this end, Zhao et al. (2010)set up a new BL model by usingthe gradient wind momentum approximation, basedon five-force balance, including the pressure gradientforce, Coriolis force, centrifugal force, turbulent friction force, and the inertial deviation force.

In this paper, we set up a TCBL model similarto that of Zhao et al. (2010)to obtain the analyticsolutions of the horizontal and vertical velocity in theTCBL. The purpose of this paper is to study the impact of the VSGW in the free atmosphere on the structure of the TCBL and the Ekman pumping at theTCBL top. In the next section, we give the theoretical framework of TCBL and the derivation process ofthe TCBL model. The impact of the VSGW on thestructure of TCBL and the Ekman pumping are presented in Section 3, followed by conclusions in Section 4.

2. Theoretical framework of TCBL2. 1 Governing equations of TCBL dynamics

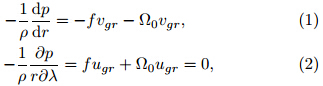

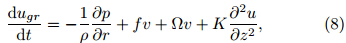

In order to facilitate the calculation, the cylindrical coordinate system(r; λ; z)is used in this study, where r; λ, and z are the radial, tangential, and vertical coordinates, respectively. On the hypothesis thatthe pressure field of TC free atmosphere is axisymmetrically circular, the tangential and radial gradientwind equations are,

where vgr and ugr are the tangential and radial gradient winds in the free atmosphere, f is the Coriolisparameter, and Ω0 = vgr/r is the angular velocity ofTC. Equations(1) and (2)express the relationship ofgradient wind balance. In other words, the pressuregradient force is balanced by the gradient wind force, i. e. , the sum of the Coriolis force and generalized cen-trifugal force on the right side of Eqs. (1) and (2).

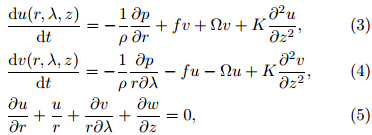

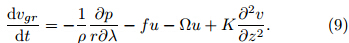

For the atmospheric motion in the TCBL, the turbulent friction of underlying surface should be takeninto consideration. In addition, due to the Coriolis effect, the air parcel deflects toward the depression and crosses the isobar instead of moving along it. Equilibrium in TCBL becomes the balance of four forces{thepressure gradient force, Coriolis force, generalized centrifugal force, and turbulent friction force. On the basis of this four-force balance, Zhao et al. (2010)furthertook into account the deviation effects caused by thenon-gradient wind inertial force, establishing a TCBLmodel in five-force balance. The governing equationsin the cylindrical coordinate are,

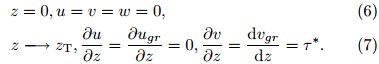

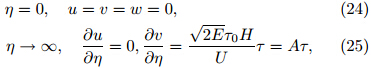

where f is assumed to be constant. For convenience, the turbulent exchange coe±cient K is also assumedconstant by neglecting the heterogeneities of turbulence in the radial, tangential, and vertical directions. When calculating the centrifugal force, the angular velocity of TC, Ω = v/r, is assumed unchanged withheight, i. e. , Ω = Ω0 = vgr=r. In the TCBL, forv > vgr, the centrifugal force is underestimated, whilev is overestimated, and vice versa. Therefore, this assumption has little impact on the distribution of thewind field. Governing Eqs. (3) and (4)are basicallyconsistent with the equations given by Wong and Chan(2007).VSGW is assumed continuous across the interface between the BL and the free atmosphere, whichmeans that the VSGW at the BL top is equal to thatin the adjacent free atmosphere. Moreover, no penetration or slippage is allowed at the bottom surface ofBL owing to its rigidity and friction. Disregarding theunderlying topography, the lower and upper boundaryconditions of the governing equations are given by

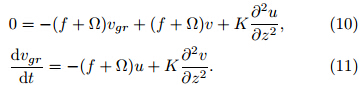

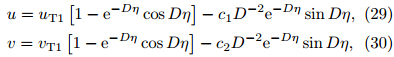

where zT is the BL height and τ* is the VSGW. By applying the gradient wind momentum approximation, that is, the wind being advected in the nonlinear termis replaced by the gradient wind(e. g. , ugr and vgr)while the actual wind(e. g. , u and v)is retained inother terms, Eqs. (3) and (4)can be rewritten asSince the effect of vertical advection is relatively smallin TCBL, it is not considered herein. On substitutingthe gradient wind balance Eqs. (1) and (2)into Eqs. (8) and (9), one can obtainPerforming dimensional analysis on Eqs. (10), (11), and (5)yieldswhere the characteristic scale is denoted by capitalletters, and the dimensionless quantity is by lowercaseletters.While the tangential wind v is in general one order larger than the radial wind u in TC, they are of thesame order in the BL(Wong and Chan, 2007). Scaledby(f +)U, characteristic equations in the horizontaldirection, i. e. , Eqs. (12) and (13), can be written as

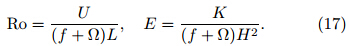

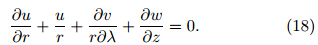

where Ro is the Rossby-like number, and E is theEkman-like number, The Rossby-like number indicates the relative importance between the inertial force and the gradient windforce in TC. For Ro ≤ 1, the gradient wind force cannot be ignored; otherwise, the gradient wind force isweak. Similarly, the Ekman-like number denotes therelative importance between the turbulent friction and the gradient wind force. For EFor the continuity Eq. (5)that satisfies the incompressible assumption, it is easy to obtain that[U=L] ≈ [W=H]. Thus, the dimensionless equationof Eq. (14)can be expressed as

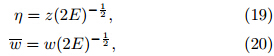

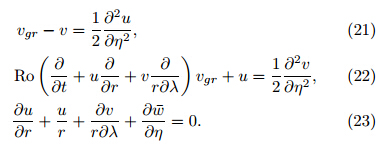

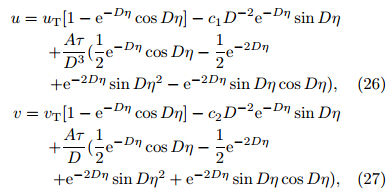

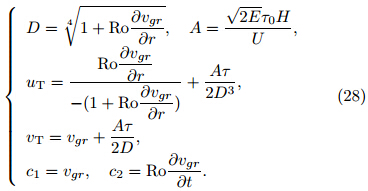

By introducing the tensile coordinate system transformation, i. e. , the characteristic Eqs. (15), (16), and (18)can berewritten asAccordingly, the boundary conditions(Eqs. (6) and (7))becomewhere A =2. 2 Horizontal wind fields of TCBL

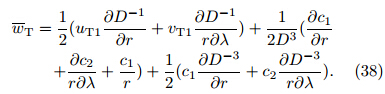

By solving Eqs. (21) and (22), the solutions of u and v can be expressed as

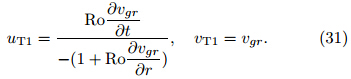

whereEquations(26) and (27)indicate the horizontal windfield of the TCBL under the Neumann boundary condition.In the absence of VSGW(τ = 0), the horizontalwind fields of the TCBL(i. e. , Eqs. (26) and (27))arereduced to the horizontal wind fields(uT1; vT1)underthe Dirichlet boundary condition(Zhao et al. , 2010), i. e. ,

whereAccording to Eq. (28), the VSGW in the free atmo-sphere has a remarkable influence on the horizontalwind(uT; vT)field at the BL top. In the case of τ > 0, the tangential wind in the free atmosphere increaseswith height, and the cyclonic circulation is strongerin the upper layer than in the lower layer. In comparison with τ = 0, the radial convergence decreases(uT > uT1), and the tangential wind becomes larger(vT > vT1)at the TCBL top. On the contrary, forτ < 0, the tangential wind in the free atmospheredecreases with height and the cyclonic circulation isweaker in the upper layer than in the lower layer. Ascompared to τ = 0, the radial convergence increases(uT < uT1) and the tangential wind becomes smaller(vT < vT1)at the TCBL top. However, for realisticTC systems in the free atmosphere, there is usually acyclonic circulation in the lower layer and an anticyclonic circulation in the upper layer, that is, τ < 0. Therefore, when the cyclonic circulation in the lowerlayer or the anticyclonic circulation in the upper layeris enhanced, the radial convergence at the TCBL topwill be enhanced as well, thus favoring the intensification of TC.The impact of free-atmosphere VSGW on the horizontal winds at other BL heights is more complicated, which is probably related to the value of η.

2. 3 Vertical pumping fields at TCBL top

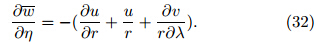

The continuity Eq. (23)shows that

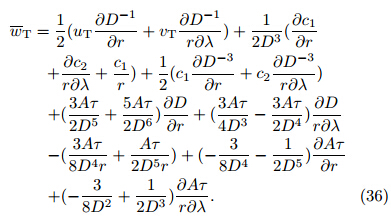

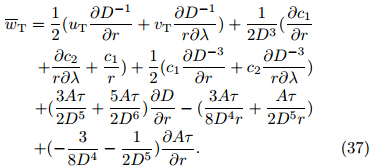

Integrating the above equation over the entire BL, with the following lower and upper conditions, where wT is the vertical pumping speed at the TCBLtop, one can obtainSubstituting the radial and tangential velocities(Eqs. (26) and (27))into Eq. (35)finally yields, Remember the assumption that the wind field atthe TCBL top is axisymmetric and in gradient windbalance. In this situation,

The fourth and fifth terms on the right sideof Eq. (37)show the combined effects of the freeatmosphere VSGW and BL turbulent friction on thevertical pumping rate at the BL top. Since D is definitely positive, for ![]() D=

D=![]() r < 0, Ekman pumping at theBL top increases(declines)if τ < 0(τ > 0), and viceversa for

r < 0, Ekman pumping at theBL top increases(declines)if τ < 0(τ > 0), and viceversa for ![]() D=

D=![]() r > 0. In reality, the vertical vorticity is usually stronger in the eyewall area and weakensoutward, that is,

r > 0. In reality, the vertical vorticity is usually stronger in the eyewall area and weakensoutward, that is, ![]() D=

D=![]() r < 0. Therefore, for τ < 0 inthe free atmosphere, it will help enhance the Ekmanpumping at the BL top.

r < 0. Therefore, for τ < 0 inthe free atmosphere, it will help enhance the Ekmanpumping at the BL top.

The last term on the right side of Eq. (37)showsthat the vertical pumping at the BL top is relatednot only to the direction and magnitude of the freeatmosphere VSGW, but also to its radial distribution. Since D is always positive, the vertical pumping rateat the BL top is enhanced with ![]() Aτ=

Aτ=![]() r < 0, and weakens when

r < 0, and weakens when ![]() Aτ=

Aτ=![]() r > 0. As mentioned in Section2. 2, the VSGW in the free atmosphere is usually negative for realistic TC systems, i. e. , τ < 0. Therefore, ifthe VSGW in the TC outer b and is greater than thatin the inner region, the Ekman pumping effect will beenhanced at the BL top, which is favorable for the intensification of TC.

r > 0. As mentioned in Section2. 2, the VSGW in the free atmosphere is usually negative for realistic TC systems, i. e. , τ < 0. Therefore, ifthe VSGW in the TC outer b and is greater than thatin the inner region, the Ekman pumping effect will beenhanced at the BL top, which is favorable for the intensification of TC.

Given the di±culties in obtaining the analytic solution of the TCBL vertical velocity, numerical integrations will be used in the next section to reproduce the TCBL wind fields.

3. Reproduction of TCBL wind fields3. 1 Setup of the TC model

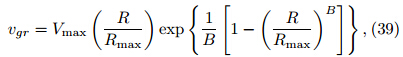

Once the TCBL-top wind, free-atmosphereVSGW, and surface turbulent friction are specified, the wind fields within the TCBL can be reproduced accordingly. To make the TC more realistic, the TCBL-top wind defined in DeMaria et al. (1992)is adopted,

where vgr is the gradient wind speed, Vmax=50 m s-1is the maximum wind speed, R = 300 km is the radiusof the TC, Rmax = 50 km is the radius of the eyewall(maximum wind speed area), and B = 0. 490 is aparameter of the TC size. Readers are referred to DeMaria et al. (1992) and MacAfee and Pearson(2006)for the detailed description of these parameters.For the sake of simplicity, the following assumptions are adopted.

(1)TC is steady, ![]() =

=![]() t = 0;

t = 0;

(2)The TC system is axisymmetrically circular, ![]() =

=![]() λ = 0;

λ = 0;

(3)Characteristic scales are U ~10 m s-1, f ~5 × 105 s-1, L ~ 3 × 105 m, H ~1000 m, K = 40.

With these assumptions, it is easy to obtain aftersimple calculations,

Furthermore, the horizontal wind field within the BL(Eqs. (26) and (27)) and the vertical velocity at theBL top(Eq. (37))can be simplified to be3. 2 Vertical distributions of horizontal windfieldsIn order to study the effects of VSGW on the horizontal wind field within the TCBL, three situationsare discussed herein:

(1)τ = 0, wind direction and wind speed in theupper free atmosphere are the same as that at thelower level;

(2)τ = 1, VSGW is positive and the cyclonic circulation is stronger in the upper free atmosphere thanat the lower level;

(3)τ = {1, VSGW is negative and there is a weaker cyclonic circulation(or anticyclone circulation)in the upper free atmosphere than at the lower level.

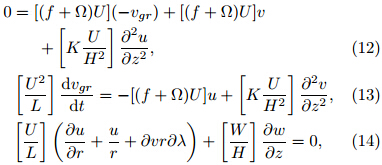

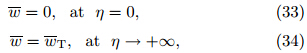

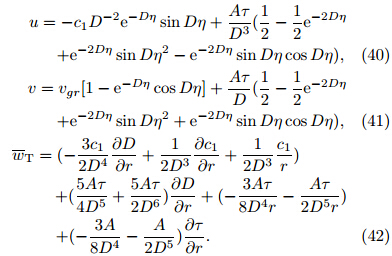

In order to represent the radial wind velocity moreclearly, the inflow is defined positive herein. Figures1a, 1d, and 1g depict the vertical distributions of thetotal, tangential, and radial wind speed in the BL withVSGW = 0. The total wind shows a very similar structure to its tangential component, as the tangentialwinds are about twice the speed of radial winds. Generally, the TCBL winds peak near the eyewall, whichis consistent with the structure of the wind imposedat the TCBL top(Eq. (39)). Weaker TCBL winds arefound near the surface because of the stronger friction there. The strong surface friction promotes greaterconvergence at the bottom BL, thus giving rise tolarger radial winds in the lower layer than in the middle and upper layers(Fig. 1g). By contrast, the tangential winds are mainly located at the middle-upperTCBL, and more close to the TC-vortex center(Fig. 1d).

|

| Fig. 1. Vertical distributions of the total(a, b, c), tangential(d, e, f), and radial(g, h, i)wind speed(m s-1)within the BL in the vertical plane through the TC center. (a, d, g)τ = 0;(b, e, h)τ = 1;(c, f, i)τ = -1. |

Compared with τ = 0, the total wind speed becomes larger at τ = 1(Fig. 1b), but weakens at τ= {1, with the maximum wind located inside the eyewall(Fig. 1c). Similar variations with τ are found forthe tangential wind(Figs. 1e and 1f). However, thefree-atmosphere VSGW exerts a more notable influence on the radial wind than on its tangential counterpart(Figs. 1h and 1i). For negative VSGW withτ = {1(Fig. 1i), the region of positive radial windexp and s outward and extends upward to the TCBLtop, as compared to τ = 0. Moreover, the radial velocity center is enhanced and displaced to a higherlevel but more outward. On the contrary, for positiveVSGW with τ = 1(Fig. 1h), the radial velocity issuppressed, with its center lowered and displaced inward toward the TC-vortex center. In summary, thenegative VSGW causes stronger inflow in the TCBL, and vice versa for the positive VSGW.

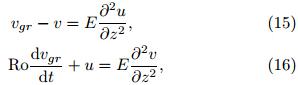

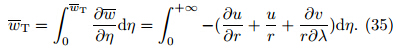

3. 3 Horizontal flow fields

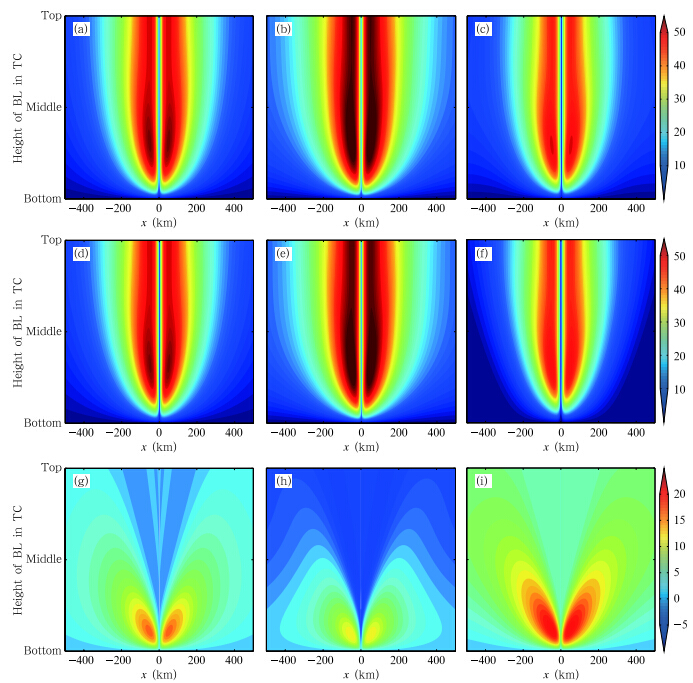

]The horizontal flow fields at the top, middle, and lower layers of the TCBL for τ = 0 are displaced inFigs. 2a, 2d, and 2g, respectively. The TCBL toplayer is mainly influenced by the free atmosphere flowabove. Therefore, the winds basically satisfy the gradient wind balance relationship, with streamlines inparallel with isobaric contours(Fig. 2a). Additionally, in the case of gradient wind balance, for a circularvortex, the isobaric contours are also circular and concentric circles. The total wind is essentially the sameas the wind imposed at the TCBL top given by Eq. (39). However, in the bottom layer where strong fiction is present, the total winds are weaker and moveacross the isobar, toward the depression at the TC-vortex center(Fig. 2g). The middle-TCBL winds liebetween the two situations above.

|

| Fig. 2. Horizontal wind speeds(shading; m s-1) and streamlines at the top(a, b, c), middle(d, e, f), and lower(g, h, i)layers of the TCBL. (a, d, g)τ = 0;(b, e, h)τ = 1;(c, f, i)τ = -1. |

In the presence of free-atmosphere VSGW, nonzero radial velocities are found at the top of the TCBL, with convergent inflow for τ = {1(Fig. 2c) and divergent outflow for τ = 1(Fig. 2b). This differs distinctively from the τ = 0 case. Qualitatively similarresults are found for the winds in the middle TCBL(Figs. 2e and 2f). As in the lower layer of TCBL, thetotal winds intensify at τ = {1, with radical inflowsincreased as well(Fig. 2i). Consequently, the convergence is enhanced, which can be inferred from theincreasing angles between isobars and streamlines. Bycontrast, the total winds decrease and the convergenceis suppressed for τ = 1(Fig. 2h). The streamlines inthe outer region of TC become more and more parallelto the isobaric contours.

In a word, negative free-atmosphere VSGWtends to enhance the radial velocity and convergencethroughout the TCBL, especially in the lower layer, although the intensity of total wind is a little bit decreased. On the contrary, positive free-atmosphereVSGW helps strengthen the TCBL total wind, but itacts to reduce the convergence, even changing it intodivergence, in particular in the middle-upper TCBL.

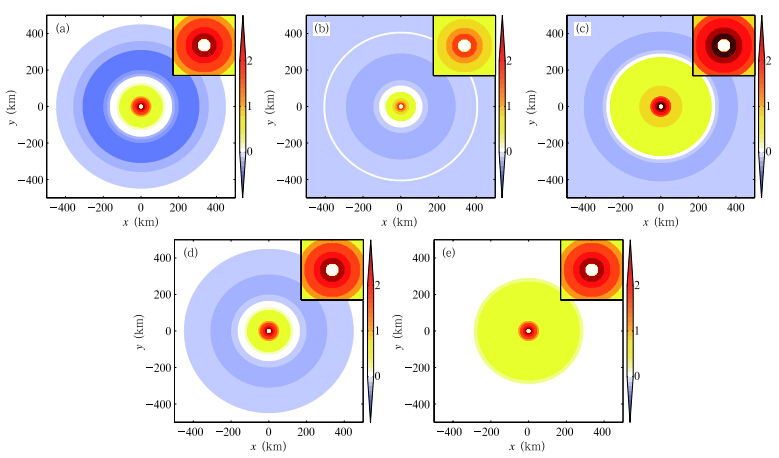

3. 4 Vertical pumping fields

As shown in Eq. (42), not only the sign of freeatmosphere VSGW but also its radial distribution influences the vertical pumping rate at the TCBL top. In order to highlight the different roles played byfree-atmosphere VSGW, five situations are considered. They are

(1)VSGW is uniformly zero, τ = 0; ![]() τ=

τ=![]() r = 0;

r = 0;

(2)VSGW is positive and uniform along the radial direction, τ = 1; ![]() τ/

τ/![]() r = 0;

r = 0;

(3)VSGW is negative and uniform along the radial direction, τ = -1; ![]() τ/

τ/![]() r = 0;

r = 0;

(4)VSGW is 0 at the TC center, and increasesoutward, ![]() τ/

τ/![]() r = 1;

r = 1;

(5)VSGW is 0 at the TC center, but decreasesoutward, ![]() τ/

τ/![]() r = -1.

r = -1.

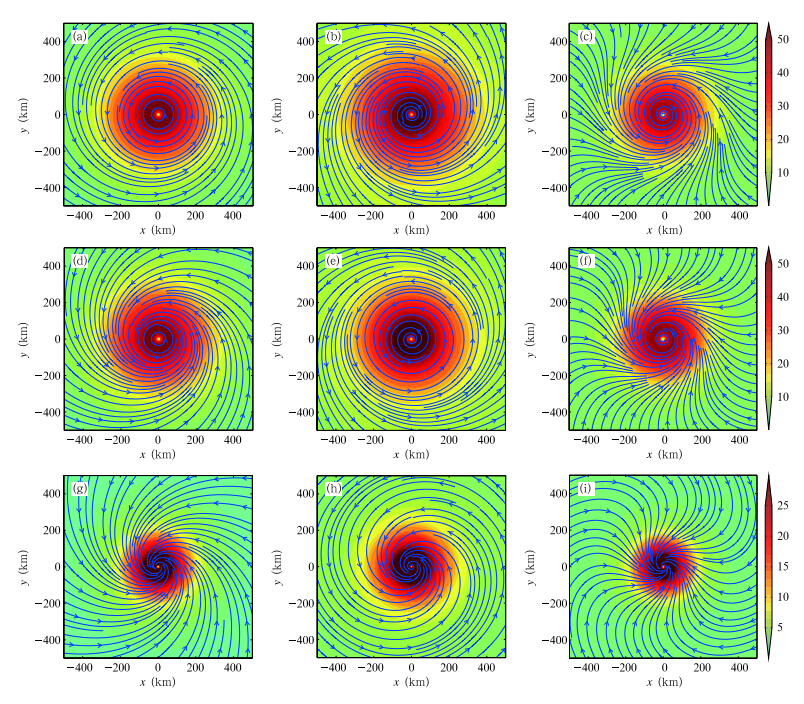

In the absence of free-atmosphere VSGW(Fig. 3a), upward pumping at the TCBL top is found within150 km of the TC center, with downward pumpingoutward. The strongest pumping effects occur in theeyewall area. The vertical pumping velocity decaysoutward, reaching its minimum at about 250 km awayfrom the TC center. Further outward, the downward pumping diminishes gradually.

|

| Fig. 3. Vertical pumping velocity(m s¡1)at the TCBL top for(a)τ = 0, |

With the VSGW present in the free atmosphere, the vertical pumping fields at the TCBL top are affected. For a positive, homogeneous VSGW whereτ = 1 and ![]() τ=

τ=![]() r = 0, both the upward and downward motions are suppressed at the TCBL top(Fig. 3b). Vertical pumping is increased over a greater region surrounding the TC eyewall when τ = -1 and

r = 0, both the upward and downward motions are suppressed at the TCBL top(Fig. 3b). Vertical pumping is increased over a greater region surrounding the TC eyewall when τ = -1 and ![]() τ=

τ=![]() r = 0, although the downward motion in theouter region of TC is still weakened(Fig. 3c). Figures3d and 3e display the vertical pumping fields at theTCBL top for varying VSGWs along the radial direction. The upward pumping in the inner region of bothFigs. 3d and 3e are nearly unchanged in comparison tothe zero-VSGW case. In the case of increasing VSGWwith

r = 0, although the downward motion in theouter region of TC is still weakened(Fig. 3c). Figures3d and 3e display the vertical pumping fields at theTCBL top for varying VSGWs along the radial direction. The upward pumping in the inner region of bothFigs. 3d and 3e are nearly unchanged in comparison tothe zero-VSGW case. In the case of increasing VSGWwith ![]() τ/

τ/![]() r = 1(Fig.3d), the downward pumpingin the outer region is similar to Fig. 3b. For a decreasing VSGW with

r = 1(Fig.3d), the downward pumpingin the outer region is similar to Fig. 3b. For a decreasing VSGW with ![]() τ/

τ/![]() r = -1(Fig. 3e), however, the upward pumping in the outer region is similar tothe homogeneous τ = {1 case(Fig. 3c). This is because τ increases(decreases)with radial distance fromzero, namely, τ is always positive(negative) and is approaching zero at the center part. In other words, thesign and value of VSGW is more important than itsradial distribution.

r = -1(Fig. 3e), however, the upward pumping in the outer region is similar tothe homogeneous τ = {1 case(Fig. 3c). This is because τ increases(decreases)with radial distance fromzero, namely, τ is always positive(negative) and is approaching zero at the center part. In other words, thesign and value of VSGW is more important than itsradial distribution.

In summary, the free-atmosphere VSGW has a significant impact on the vertical pumping at theTCBL top. When the VSGW is negative, it will favorthe intensification of the convergent upward motion atthe TCBL top.

4. Concluding remarks

A TC boundary layer(BL)model is establishedin this paper, based upon five-force balance includingthe pressure gradient force, Coriolis force, centrifugalforce, turbulent friction, and inertial deviation force. Governing equations are formed in cylindrical coordinate system, which are first linearized using gradient wind momentum approximation and then simplified according to scale analysis. Analytic solutionsof horizontal velocity within the BL are derived bysolving the simplified governing equations under givenboundary conditions. Afterward, vertical velocity inthe BL is obtained by vertically integrating the threedimensional incompressible continuity equation. Thederived solutions reveal that the wind fields within theTCBL are notably a®ected by the vertical shear of gradient wind(VSGW)in the free atmosphere.

In order to examine the influence of freeatmosphere VSGW, the BL model established hereinis applied to an idealized TC-vortex defined in DeMaria et al. (1992). The results show that, for negative free-atmosphere VSGW, namely, there is a warmcore above the TCBL, the total horizontal velocity inthe TCBL is somewhat suppressed. However, the radial velocity notably intensifies, with the maximumradial inflow displaced upward and outward. Consequently, the convergence is enhanced throughoutthe TCBL, giving rise to a stronger vertical pumping at the TCBL top. On the contrary, for positivefree-atmosphere VSGW, namely, there is a cold coreabove the TCBL, the radial inflow is significantly suppressed, and even with divergent outflow occurring inthe middle-upper TCBL. For varying VSGWs alongthe radial direction, the upward pumping fields in theinner region of both cases are nearly unchanged incomparison to the zero-VSGW case. In the case of increasing VSGW, the downward pumping in the outerregion is similar to the positive VSGW case. For a decreasing VSGW, however, the upward pumping in theouter region is similar to the homogeneous negative VSGW case. In sum, the sign and value of VSGW aremore important than its radial distribution. It thussuggests that the negative VSGW induces strongerconvergence and Ekman pumping in the TCBL, whichfavors the formation and intensification of TC.

The above results are consistent with the numerical study of Tuleya and Kurihara(1981) and the composite analysis study of Yu et al. (2007). However, inthe present BL model, the analytic solution has beenobtained under some assumptions, hence with its ownlimitations. Di®erent from previous numerical(Wang and Holl and , 1996; Braun and Wu, 2007) and observational studies(Cheng et al. , 2012; Reasor et al. , 2013), the tilting of the tangential wind in the TCBL is hardto see, which may be related to the assumption in thecalculation of centrifugal force. While being neglectedherein, TC asymmetry is an important factor to its intensity(Frank and Ritchie, 2001; Ueno, 2007). Therefore, more investigations are necessary for fully underst and ing of the impact of free-atmosphere VSGW onTCBL structures and physical processes. In the forthcoming articles, we will study the threshold value ofVSGW, perform full-physics model simulations, and focus on the storm intensification and TCBL structures.

Acknowledgments. Thanks to the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that have improved this manuscript.

| Anthes, R. A., 1971: Iterative solutions to the steady-state axisymmetric boundary-layer equations under an intense pressure gradient. Mon. Wea. Rev., 99,261-268. |

| Bender, M. A., 1997: The effect of relative flow on the asymmetric structure in the interior of hurricanes. J. Atmos. Sci., 54, 703-724. |

| Black, M. L., J. F. Gamache, F. D. Marks, et al., 2002: Eastern Pacific hurricanes Jimena of 1991 and Olivia of 1994: The effect of vertical shear on structure and intensity. Mon. Wea. Rev., 130, 2291-2312. |

| Blumen, W., and R. S. Wu, 1983: Baroclinic instabil-ity and frontogenesis with Ekman boundary layer dynamics incorporating the geostrophic momentum approximation. J. Atmos. Sci., 40, 2630-2637. |

| Braun, S. A., and L. G. Wu, 2007: A numerical study of Hurricane Erin (2001). Part Ⅱ: Shear and the organization of eyewall vertical motion. Mon. Wea. Rev., 135, 1179-1194. |

| Brown, R. A., 1974: Analytic Methods in PlanetaryBoundary Layer Modeling. Adam Hilger L TD, London, and Halstead Press, John Wiley and Sons, New York, 150 pp. |

| Charney, J. G., and A. Eliassen, 1964: On the growth ofthe hurricane depression. J. Atmos. Sci., 21, 68-75. |

| Cheng, Yu-Hsin, Shih-Jen Huang, A. K. Liu, et al., 2012: Observation of typhoon eyes on the sea surface usingmulti-sensors. Remote Sens. Environ., 123, 434-442. |

| Chu Huiyun and Wu Rongsheng, 2013: Environmental influences on the intensity change of tropical cy-clones in the western North Pacific. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 27(3), 335-343. |

| Corbosiero, K. L., and J. Molinari, 2002: The effects ofvertical wind shear on the distribution of convection in tropical cyclones. Mon. Wea. Rev., 130, 2100-2123. |

| DeMaria, M., 1996: The effect of vertical shear on trop-ical cyclone intensity change. J. Atmos. Sci., 53,2076-2088. |

| —-, S. D. Aberson, K. V. Ooyama, et al., 1992: A nested spectral model for hurricane track forecasting. Mon. Wea. Rev., 120, 1628-1643. |

| Ekman, V. W., 1905: On the influence of the earth'srotation on ocean currents. Arkiv. Mat. Astron. Fysik., 2(11), 1-53. |

| Emanuel, K. A., 1986: An air-sea interaction theory fortropical cyclone. Part I: Steady-state maintenance.J. Atmos. Sci., 43, 585-605. |

| —-, 2003: A Century of Scientific Progress and Evalua-tion. Hurricane! Coping with Disaster. Washington D. C., Amer. Geophy. Union, 177-204. |

| Frank, W. M., and E. A. Ritchie, 1999: Effects of environ-mental flow upon tropical cyclone structure. Mon. Wea. Rev., 127, 2044-2061. |

| —-, and —-, 2001: Effects of vertical wind shear on the intensity and structure of numerically simulated hurricanes. Mon. Wea. Rev., 129, 2249-2269. |

| Gallina, G. M., and C. S. Velden, 2002: Environmentalvertical wind shear and tropical cyclone intensity change utilizing enhanced satellite derived wind in-formation. Twenty-fifth Conference on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology, San Diego, CA, 29 April-3 May, Amer. Meteor. Soc., 172-173. |

| Gray, W. M., 1968: Global view of the origin of tropical disturbances and storms. Mon. Wea. Rev., 96,669-700. |

| Holland, G. J., and Y. Q. Wang, 1999: What limits trop-ical cyclone intensity? Preprint, 23rd Conference on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology, 10-15 Jan-uary, Dallas, Texas, 955-958. |

| Hoskins, B. J., 1975: The geostrophic momentum ap-proximation and the semi-geostrophic equations. J. Atmos. Sci., 32, 233-242. |

| —-, and F. P. Bretherton, 1972: Atmospheric frontogen-esis models: Mathematical formulation and solution. J. Atmos. Sci., 29, 11-37. |

| MacAfee, A. W., and G. M. Pearson, 2006: Development and testing of tropical cyclone parametric wind mod-els tailored for midlatitude application-preliminary results. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol., 45, 1244-1260. |

| McBride, J. L., and R. Zehr, 1981: Observational analysis of tropical cyclone formation. Part Ⅱ: Comparison of non-developing versus developing systems. J. At-mos. Sci., 38, 1132-1151. |

| Merrill, R. T., 1988: Environmental influences on hurri-cane intensification. J. Atmos. Sci., 45, 1678-1687. |

| Panchev, S., and T. S. Spassova, 1987: A barotropic model of the Ekman planetary boundary layer based on the geostrophic momentum approxima-tion. Bound-Layer Meteor., 40, 339-347. |

| Reasor, P. D., R. Rogers, and S. Lorsolo, 2013: Environ-mental flow impacts on tropical cyclone structure diagnosed from airborne Doppler radar composites. Mon. Wea. Rev., 141, 2949-2969. |

| Riehl, H., and R. J. Shafer, 1944: The recurvature of tropical storm. J. Atmos. Sci., 1, 42-54. |

| Shu Shoujuan, Wang Yuan, and Bai Lina, 2013: In-sight into the role of lower-layer vertical wind shear in tropical cyclone intensification over the western North Pacific. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 27(3), 356-363. |

| Tan Zhemin, Fang Juan, and Wu Rongsheng, 2005: Ek-man boundary layer dynamic theories. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 63, 543-555. (in Chinese) |

| Tuleya, R. E., and Y. Kurihara, 1981: A numerical study on the effects of environmental flow on tropical storm genesis. Mon. Wea. Rev., 109, 2487-2506. |

| Ueno, M., 2007: Observational analysis and numerical evaluation of the effects of vertical wind shear on the rainfall asymmetry in the typhoon inner-core region. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan, 85, 115-136. |

| Velden, C. S., and W. L. Smith, 1983: Monitoring tropi-cal cyclone evolution with NOAA satellite microwave observations. J. Climate Appl. Meteor., 22(5), 714-724. |

| Wang Yuan, Song Jinjie, and Wu Rongsheng, 2013: A new insight into the contribution of environmental conditions to tropical cyclone activities. Acta Me-teor. Sinica, 27(3), 344-355. |

| Wang, Y. Q., and G. J. Holland, 1996: Tropical cyclone motion and evolution in vertical shear. J. Atmos. Sci., 53, 3313-3332. |

| Willoughby, H. E., 1990: Gradient balance in tropical cyclones. J. Atmos. Sci., 47, 265-274. |

| Wong, M. L. M., and J. C. L. Chan, 2007: Modeling the effects of land-sea roughness contrast on tropical cyclone winds. J. Atmos. Sci., 64, 3249-3264. |

| Wu, G. X., and H. Z. Liu, 1998: Vertical vorticity devel-opment owing to down-sliding at slantwise isentropic surface. Dyn. Atmos. Oceans, 27, 715-743. |

| Wu, R. S., and W. Blumen, 1982: An analysis of Ek-man boundary layer dynamics incorporating the geostrophic momentum approximation. J. Atmos. Sci., 39, 1774-1782. |

| Yu Yubin, Yang Changxian, and Yao Xiuping, 2007: The vertical structure characteristics analysis on abrupt intensity change of tropical cyclone over the offshore of China. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 31(5), 876-886. (in Chinese) |

| Zehr, R. M., 2003: Environmental vertical wind shear with Hurricane Bertha (1996). Wea. Forecasting,18, 345-356. |

| Zeng, Z. H., Y. Q. Wang, and L. S. Chen, 2010: A sta-tistical analysis of vertical shear effect on tropical cyclone intensity change in the North Atlantic. Geo-phys. Res. Lett., 37, L02802. |

| Zhao Yunwu, Song Jinjie, and Wang Yuan, 2010: The ef-fect of mesoscale mountain in the boundary layer of the tropical cyclone. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Sci. Ed.),37(6), 713-721. (in Chinese) |

2014, Vol. 28

2014, Vol. 28