The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- WU Tongwen, SONG Lianchun, LI Weiping, WANG Zaizhi, ZHANG Hua, XIN Xiaoge, ZHANG Yanwu, ZHANG Li, LI Jianglong, WU Fanghua, LIU Yiming, ZHANG Fang, SHI Xueli, CHU Min, ZHANG Jie, FANG Yongjie, WANG Fang, LU Yixiong, LIU Xiangwen, WEI Min, LIU Qianxia, ZHOU Wenyan, DONG Min, ZHAO Qigeng, JI Jinjun, Laurent LI, ZHOU Mingyu. 2014.

- An Overview of BCC Climate System Model Development and Application for Climate Change Studies

- J. Meteor. Res., 28(1): 34-56

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-014-3041-7

Article History

- Received March 19, 2013

- in final form November 15, 2013

2 National Meteorological Information Center, CMA, Beijing 100081, China;

3 Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China;

4 Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique, Paris 75005, France5 National Marine Environmental Forecasting Center, Beijing 100081, China

Simulations using these two versions of the BCC_CSM model have been contributed to the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase five (CMIP5) in support of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report (AR5). These simulations are available for use by both national and international communities for investigating global climate change and for future climate projections. Simulations of the 20th century climate using BCC_CSM1.1 and BCC_CSM1.1(m) are presented and validated, with particular focus on the spatial pattern and seasonal evolution of precipitation and surface air temperature on global and continental scales. Simulations of climate during the last millennium and projections of climate change during the next century are also presented and discussed. Both BCC_CSM1.1 and BCC_CSM1.1(m) perform well when compared with other CMIP5 models. Preliminary analyses in-dicate that the higher resolution in BCC_CSM1.1(m) improves the simulation of mean climate relative to BCC_CSM1.1, particularly on regional scales.

1. Introduction

Global climate and environmental changes underglobal warming are one of the great challenges facinghuman societies. These changes reflect the complexinteractions among atmosphere, hydrosphere, lithosphere, cryosphere, and biosphere within the climatesystem. The development of theories and methodologies for investigating interactions and feedback mechanisms among the individual components of the climatesystem is a prerequisite to advanced underst and ing ofthe behavior of the climate system and to improvedprediction of its future evolution.Climate system models are effective tools for objectively describing interactions in the climate system and exploring howthese interactions impact climate change.

The National Climate Center(NCC)was established in 1995 under a national priority researchproject entitled “Research on Short-term Climate Prediction System in China”.Under the auspices ofthe NCC, scientists from the China MeteorologicalAdministration, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Agriculture, and Ministry of Water Resources have together undertakenthe research and development of a short-term climate prediction system.This collaborative workquickly yielded a first-generation atmospheric generalcirculation model(AGCM)(BCC−AGCM1.0; Dong, 2001 ), which was later followed by a coupled oceanatmosphere model(BCC−CM1.0). This model system has played an important role in operational shortterm climate prediction and studies of climate changein China( Ding et al., 2002, 2004, 2006; Zhang et al., 2004; Li et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2005 ).

NCC initiated the research and developmentofanew-generationclimatemodelsystemin2005.This initiative has produced three secondgeneration versions of the AGCM(BCC−AGCM2.0, BCC−AGCM2.1, and BCC−AGCM2.2).NCC hasalso developed a first-generation l and surface processmodel(BCC−AVIM1.0)that combines the vegetationdynamics and soil carbon cycle model AVIM developed by Ji(1995)with the Community L and Modelversion 3(CLM3)developed at the National Center for Atmospheric Research(NCAR). The ocean model(MOM4−L40)has been modified from the ModularOcean Model(MOM4)developed at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory(GFDL)to includethe ocean carbon cycle.These component modelsserve as the basis for NCC’s climate system modelat coarse resolution(T42, or approximately 280 km; BCC−CSM1.1) and moderate resolution(T106, or approximately 110 km; BCC−CSM1.1(m)), in which theocean, l and surface, atmosphere, and sea ice components are fully coupled. This paper briefly reviews thedevelopment of these models and recent progress intheir application to climate change studies.

2. Development of the BCC Climate SystemModel2.1 Atmospheric General Circulation Model(AGCM)2.1.1BCC−AGCM2.0BCC−AGCM2.0 is a spectral AGCM( Wu et al., 2008, 2010 )with an adjustable horizontal resolution and 26 vertical layers. The default horizontal resolution is T42, which corresponds to approximately2.8125°×2.8125°. This model is largely based on theNCAR CAM3( Collins et al., 2004 ), but the reference atmosphere and surface pressure have been modified. The reference atmosphere represents the thermalstructure of the mid/upper troposphere and stratosphere better than the default reference atmosphereused in CAM3 does. This modification reduces theeffects of inhomogeneous vertical stratification and biases in topographic truncations, among other factors.Deviations in temperature and surface pressure fromthe reference atmosphere are treated as prognosticvariables. Prognostic equations for water vapor, cloudwater, cloud ice, and other hydrometeors are solvedusing a semi-Lagrangian approach. By contrast, theequations for vorticity, divergence, and deviations intemperature and surface pressure are solved using explicit or semi-implicit Eulerian methods. A detaileddescription of the dynamical framework has been provided by Wu et al.(2008).The model physics ismostly based on CAM3, with the following improvements. First, the parameterization scheme for mass-flux type cumulus convection developed by Zhang and McFarlane(1995)has been adapted as proposed by Wu et al.(2010). Second, a dry adiabatic adjustment scheme has been introduced to conserve potential temperature throughout the whole layer. Third, the parameterization of snow cover proposed by Wu and Wu(2004)has been adopted. Improved parameterizations of sensible and latent heat fluxes from theocean surface that consider the effects of surface waveshave been proposed( Wu et al., 2010 ). L and surfaceprocesses are simulated using the CLM3( Oleson et al., 2004 ). The BCC−AGCM2.0 model has been shown toaccurately simulate the current climate and annual cycle( Wu et al., 2010 ), decadal changes in precipitationin the East Asian and Asian/Australian monsoon regions( Wang et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2012 ), changesin the occurrence of extreme temperature and precipitation events( Chen et al., 2011; Dong et al., 2012 ), cloud radiative forcing( Guo et al., 2011 ), the MaddenJulian oscillation( Dong et al., 2009 ), the Meiyu seasonin the Yangtze-Huai River basin( Shen et al., 2011 ), and heavy precipitation processes in China( Jie et al., 2010 ).

Recently, Zhang Hua et al.(2012)coupled theBCC−AGCM2.0 with the CUACE Aerosol Model(BCC−AGCM2.0.1−CAM). CUACE is based on theCanadian Aerosol Module(CAM)( Gong et al., 2002, 2003 )developed in collaboration with the ChineseAcademy of Meteorological Sciences.CUACE is aparticle size distribution model.It includes multicycle physical and chemical processes, such as theemission, transport, transformation, cloud interactions, and deposition of five common aerosol types(sulfate, black carbon, organic carbon, dust, and sea salt). Aerosol emission data were taken from amodel intercomparison with aerosol observations(AeroCom; http://aerocom.met.no/aerocomhome.html), which includes gas-phase chemistry and provides anexploratory tool for simulating changes in aerosol distributions and assessing their implications for climate.Zhao et al.(2013)provided a preliminary evaluation of BCC−AGCM2.0.1−CAM simulations of thedistributions and climatic impacts of these commonaerosols. The model simulations of these aerosols generally agree well with observations. Zhang Hua et al.(2012)used BCC−AGCM2.0.1−CAM to simulate theglobal radiative forcing of three anthropogenic aerosols(black carbon, organic carbon, and sulfate) and twonatural aerosols(dust and sea salt).Output fromthese simulations was included in the AeroCOM PhaseII model intercomparison of aerosol radiative forcings( Myhre et al., 2012 ).

Several studies have used BCC−AGCM2.0 toexamine parameterizations of cloud and radiationphysics.Jing and Zhang(2012)applied a newMonte Carlo Independent Column Approximationbased(McICA)cloud-radiation framework withinBCC−AGCM2.0.This framework provides a moreflexible description of the sub-grid cloud structure.Their results show that perturbations to the modelvariables caused by McICA stochastic errors are small, with little impact on the model climate.Differences between global mean values and reference values calculated with the Independent Column Approximation(ICA)approach are within ±0.01%, sothe climate characteristics(including zonal, vertical, and sub-regional distributions)are largely consistent with ICA. The McICA cloud-radiation schemeused in BCC−AGCM2.0 has a higher confidence thanthe original scheme.Under McICA, radiation processes in the model have been updated to include theindependently-developed BCC-RAD parameterizationscheme. Greenhouse gas(GHG)concentrations are derived by using a K-distribution module( Zhang Hua et al., 2003, 2006a, 2006b; Shi and Zhang, 2007 ), while aerosol optical properties are calculated basedon results reported by Wei and Zhang(2011) and Zhang Hua et al.(2012).BCC-RAD has participated in the AeroCom radiation model intercomparison. Cloud and radiation processes are independentunder McICA. It is therefore relatively easy to adjust cloud structure and further improve the radiationmodel, with good prospects for the future development and application of BCC−AGCM.

2.1.2 BCC−AGCM2.1 and BCC−AGCM2.2The most recent versions of BCC−AGCM2 areBCC−AGCM2.1(with a T42 global resolution) and BCC−AGCM−2.2(with a T106 global resolution, roughly corresponding to 110 km). These new versionsinclude the following improvements. First, a new parameterization scheme for deep cumulus convectionsdeveloped by Wu(2012)has been introduced. Thisscheme has been tested in a single column modelconfiguration using data from Atmospheric Radiation Measurement(ARM)stations during the summers of 1995 and 1997.When used in combination with the Hack shallow convection scheme( Hack, 1994 ) and parameterizations of stratiform precipitation( Rasch and Kristjansson, 1998; Zhang Minghua et al., 2003 ), the Wu(2012)convection scheme successfully reproduces the intensity and evolution ofmajor precipitation events. Second, parameters derived from cloud amount have been further optimized and improved. Third, an option for predicting globalmean CO2 concentrations has been added. Finally, the BCC−AVIM1.0 l and surface model is now usedto simulate l and -atmosphere fluxes. BCC−AGCM2.1 and BCC−AGCM2.2 are the atmospheric components of the climate system models BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m), respectively.

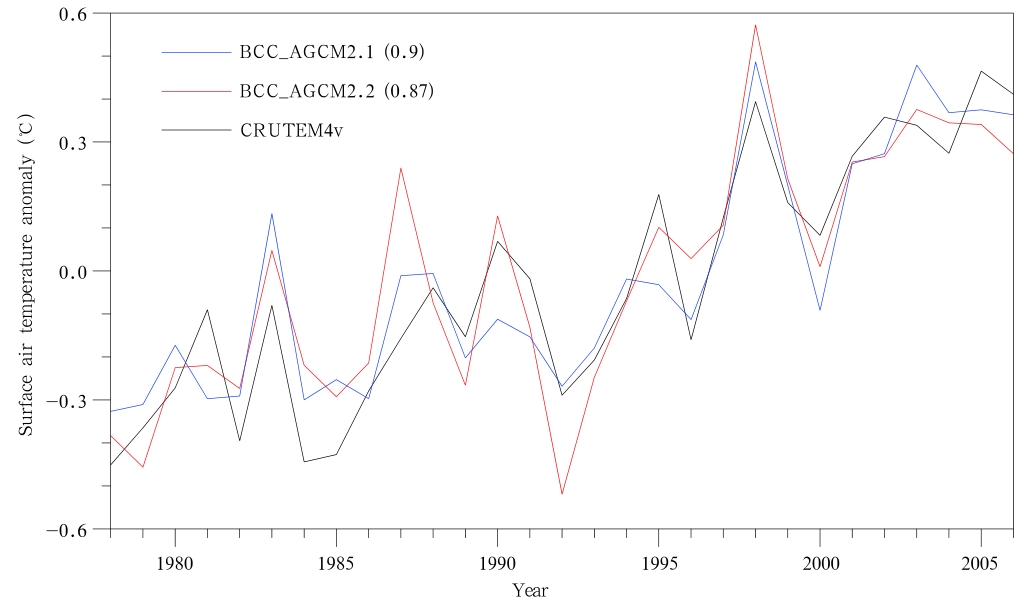

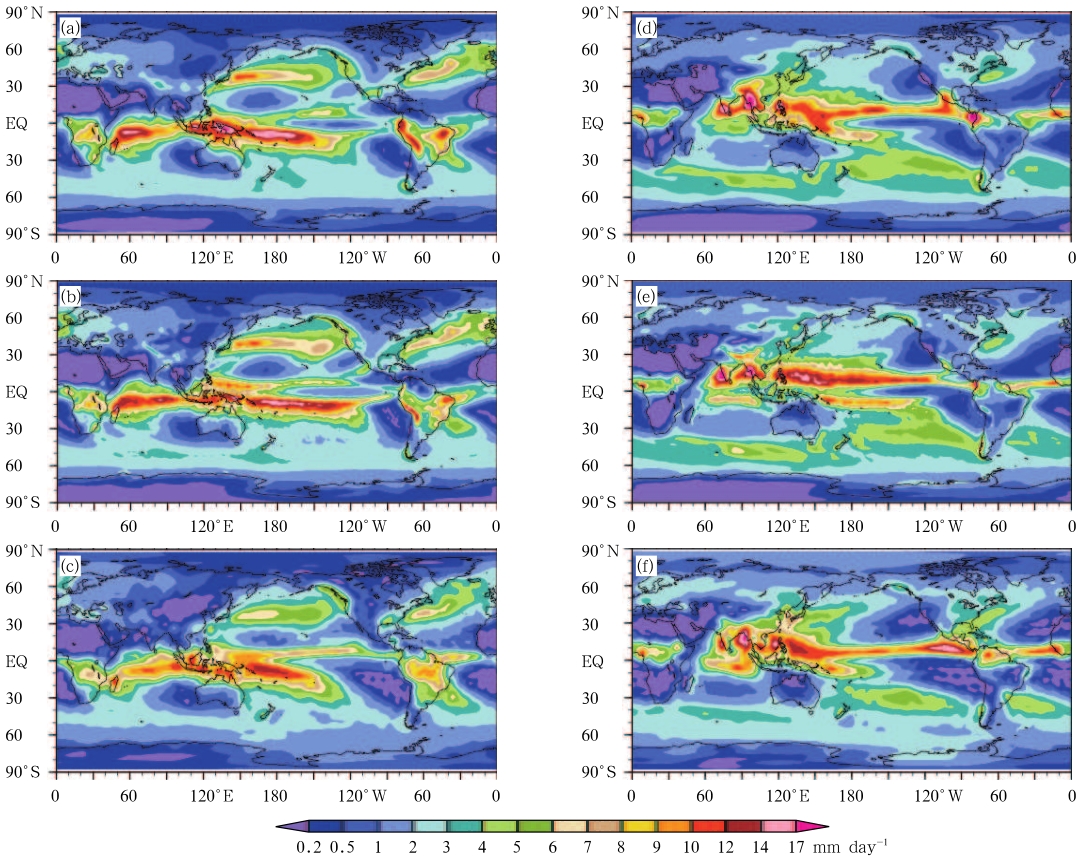

A set of st and ard atmospheric model intercomparison(AMIP)tests driven by observed forcing data(including sea surface temperature and the distribution of sea ice, solar activity, aerosols, and GHGs)have demonstrated the capabilities of BCC−AGCM2.1 and BCC−AGCM2.2 for simulating climate. Figure 1 shows interannual and decadal changes in globalmean temperature anomalies over l and during theperiod 1978–2006. Both models largely capture observed variations in temperature. Correlations withversion 4 of the Climatic Research Unit(CRU)reconstructed temperature( Brohan et al., 2006 )are 0.90 forBCC−AGCM2.1 and 0.87 for BCC−AGCM2.2. Bothmodels also capture the observed spatial distributionsof winter and summer precipitation during 1979–2008(Fig. 2 ), although biases in summer precipitation aresubstantial in both models.These biases are particularly pronounced over eastern China, where thebelt of strong precipitation is located further westthan observed.Underestimates of summer precipitation are common to many internationally availableclimate models, and arise from multiple factors. Although these factors require more in-depth investigations, they may include errors in simulating l and surface processes over the Tibetan Plateau or the locationof the western Pacific subtropical high. The higherresolution BCC−AGCM2.2 provides a better simulation of regional precipitation than BCC−AGCM2.1, along with better simulations of the centers of heavyprecipitation over Southwest China, South China, South Asia, and the Southeast Asian monsoon region.

|

| Fig. 1. Surface air temperature anomaly(℃)over global l and areas from BCC−AGCM2.1, BCC−AGCM2.2, and CRUTEM version 4. Anomalies are calculated relative to the 1978–2006 mean. The correlations of the model time seriesrelative to the observations are shown in brackets. |

|

| Fig. 2. Climatological mean precipitation(mm day−1)for(a, c, e)DJF and (b, d, f)JJA from(a, b)BCC−AGCM2.1, (c, d)BCC−AGCM2.2, and (e, f)the reconstructed observation by Xie and Arkin(1997). |

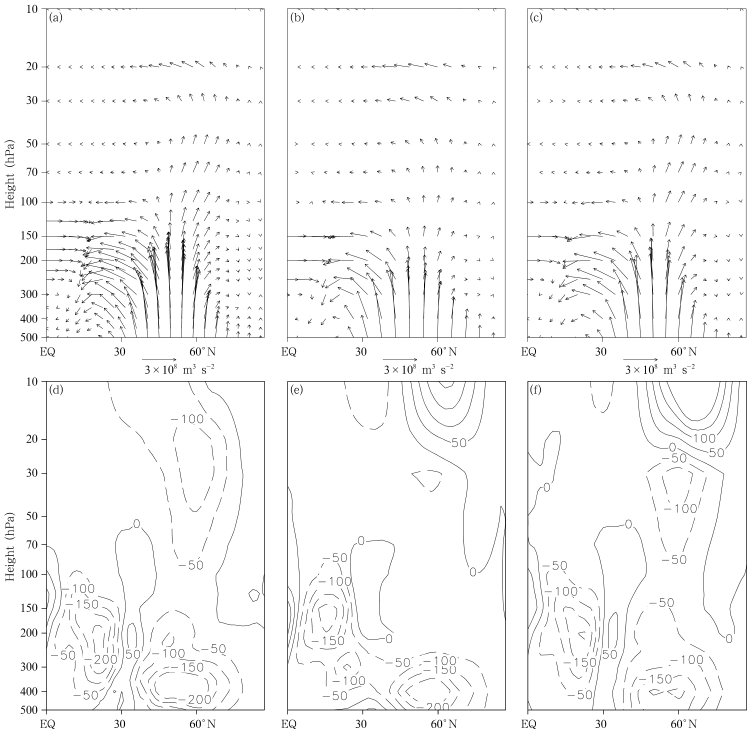

Lu et al.(2014)analyzed an AMIP run of BCC−AGCM2.1 that covers the period 1979–2008. They reported that the model simulations of the zonal meanwind fields, temperature distributions, and seasonalvariations in the stratosphere were consistent withthose in the NCEP/NCAR reanalysis. The model wasalso able to simulate seasonal changes in the stratospheric polar vortex, although it generally underestimated temperatures both near the tropopause and inthe upper stratosphere. Major biases in the simulatedtemperature profiles and upper-air jet streams relativeto the reanalysis were mainly confined to wintertimemid and high latitudes. Lu et al.(2014)pointed outthat these biases might be linked to perturbation processes in the model. Analysis of the Eliassen-Palm(EP)flux(Figs. 3a–c)indicates that both equatorward and poleward propagations of planetary waves tend tobe weaker when the model is weakly perturbed. Whenthe equatorward propagation of planetary waves in themodel is strong, most of the energy generated by theperturbation will be transported to lower latitudes. Bycontrast, the poleward propagation of planetary wavesis relatively weak(short arrows in Figs. 3a–c). Perturbations reaching the middle and upper stratosphereare dominated by upward motion, which may lead toweaker poleward propagation in the vortex. These issues likely play a major role in the model overestimating of the strength of the polar vortex and underestimating of wintertime temperature in the NorthernHemisphere stratosphere. Analysis of the E-P flux divergence(Figs. 3d–f)shows a zone of strong E-P flux divergence in the planetary wave source region in themidlatitude troposphere(30°–60°N). The energy fromperturbations largely resides in this region, propagating upward after convergence. Another area of strongE-P flux divergence is apparent over the subtropical region from the upper troposphere into the lower stratosphere. This region may be related to adjustments inthe subtropical jet stream. The jet stream is locatedslightly higher in the model results than in the reanalysis, but its intensity and range are similar. Overall, BCC−AGCM2.1 simulates a dominant equatorwardpropagation of planetary waves, which is consistentwith the reanalysis. Nevertheless, large errors remainbetween 100 and 20 hPa in the stratosphere over mid and high latitudes(particularly near 60°N). The ERAInterim reanalysis indicates strong E-P flux divergencein this region. The E-P flux divergence simulated inthis region by BCC−AGCM2.1 is relatively weak, leading to stronger circumpolar westerlies that preventperturbations from entering the polar region and interacting with the stratospheric polar vortex.

|

| Fig. 3. Climatological mean(a, b, c)Eliassen-Palm(E-P)flux(m3s−2) and (d, e, f)E-P flux divergence(m2s−2)during January from the(a, d)ERA-Interim reanalysis, (b, e)NCEP/NCAR reanalysis, and (c, f)BCC−AGCM2.1.( Lu et al., 2014 ). |

Both BCC−AGCM2.1 and BCC−AGCM2.2 havebeen used to calculate 6–15-day extended forecasts ofprecipitation and other weather processes. Jie et al.(2013)reported improvements in 6–15-day forecastsof summer precipitation using a time-lagged ensemble approach with daily rainfall thresholds set to 1 and 5 mm day−1, respectively. These improvementswere particularly pronounced over the relatively wetareas in central and southern China, northeasternChina, and the southeastern boundary of the TibetanPlateau.

2.2 Land surface modelL and surface models describe exchanges of mass and energy in soils and at the l and -atmosphere interface. These models are important components ofclimate system models. Chinese scientists have madesubstantial contributions to the development of l and surface models. Ji(1995)developed the AtmosphereVegetation Interaction Model(AVIM), which accountsfor biochemical processes like photosynthesis and vegetation respiration while also considering biophysicalprocesses such as the exchange of heat and moistureamong vegetation, soil, and atmosphere. The updatedversion AVIM2( Ji et al., 2008 )includes three modules.A l and -surface physical process module describes radiation transfer through the vegetation canopy to thesoil surface, as well as the exchange of moisture and heat among vegetation, air, and soil. The second module simulates eco-physiological processes during vegetation growth( e.g., photosynthesis, respiration, allocation of photosynthetic assimilated carbon, phenology, etc.). The third module provides a treatment ofsoil carbon decomposition.

The l and surface model BCC−AVIM1.0 was developed as a component of BCC−CSM1.1 using theNCAR CLM3 and AVIM2 as a basis. BCC−AVIM1.0includes a soil moisture and heat transfer modulesimilar to that in CLM3, with underlying surfacesseparated into four categories:soil, wetl and , lake, and glacier.Soil is vertically discretized into 10 layers.Vegetation consists of one layer, with snowcover partitioned into as many as five layers depending on snow depth. L and vegetation is divided into15 plant functional types(PFTs), with each modelgrid box containing up to 4 PFTs( Oleson et al., 2004 ). BCC−AVIM1.0 also includes a module thatincorporates the parameterizations of vegetation dynamics and soil carbon decomposition from AVIM2( Ji, 1995; Ji et al., 2008 ).This module describesthe terrestrial carbon cycle, including CO2sequestration through photosynthesis, vegetation growth, and withering, and CO2release back into the atmospherethrough soil respiration. The snow cover scheme takesinto account multiple factors( e.g., snow depth, surfaceroughness, and sub-grid topography)for snow coverfraction(SCF). SCF is generally underestimated inCLM3( Li et al., 2009 ), so this scheme has been modified to improve the simulation of SCF in regions withcomplex topography(such as the Tibetan Plateau and the Mongolian Plateau).BCC−AVIM1.0 serves asthe l and surface component in both BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m), and is used for CMIP5 experiments. Wu et al.(2013)demonstrated the capacity ofBCC−AVIM1.0 for simulating the l and carbon cycle and terrestrial eco-systems during the 20th century.

The second generation of this model(BCC−AVIM2.0)is currently under development. Revisionswill include changing the empirical plantleaf unfolding and withering dates prescribed in BCC−AVIM1.0 to adynamic determination of leaf unfolding, growth, and withering dates according to the budget of photosynthetic assimilated carbon. This change will be similarto the phenology scheme used in CTEM( Arora, 2005 ).The method for identifying the threshold soil temperatures for freezing and thawing will also be modified( Xia et al., 2011 ), and a four-stream radiative transfer parameterization for the vegetation canopy will beincorporated( Zhou et al., 2010 ). These changes areexpected to improve several aspects of the simulation, most notably the surface energy balance.

2.3 Global ocean general circulation modelThe MOM4−L40 is a global Ocean General Circulation Model(OGCM) and a very important component of the climate system model BCC−CSM. Thismodel has been developed by modifying the MOM4model developed by the Geophysical Fluid DynamicsLaboratory(GFDL). The model is run on a globalthree-pole grid, in which the North Pole is imposed onboth North America and the Eurasian continent. Itshorizontal resolution is 1°×1°poleward of 30°N and 30°S, incrementally descending to 1/3° latitude within30°N and 30°S. The model has 40 vertical layers. Thetop 200 meters are divided into 20 layers of equal thickness(10 m). The physical process parameterizationschemes( Griffies et al., 2005 )include Swedy’s tracerbased third order advection, isopycnic surface mixedtracer diffusion, Laplace horizontal friction, KPP vertical mixing, complete convective adjustment, and seafloor boundary/steep topography overflow processingthat allows unstable gravity-driven fluid elements toflow down slope in the upstream advection scheme.The effects of spatial heterogeneities in chlorophyllare taken into account when calculating the penetration of short-wave solar irradiance. The ocean carboncycle module from MOM4 FMS has been incorporatedinto MOM4−L40 to simulate the ocean carbon cycle.This module is based on the Ocean Carbon ModelIntercomparison Project phase 2(OCMIP2), and hasa relatively well-integrated ocean carbon cycle.

MOM4−L40 is currently available in two versions(MOM4−L40v1 and MOM4−L40v2), whichhavedifferentl and and submarinetopographies.MOM4−L40v1 is the ocean component ofBCC−CSM1.1, while MOM4−L40v2 is the ocean component of BCC−CSM1.1(m). The treatment of inl and seas in MOM4−L40v1 may cause unreasonable massaccumulation in those regions of the ocean. The l and sea masks in MOM−L40v2 have been adjusted toisolate inl and seas. The results of the IPCC AR5 historical experiment indicate that both MOM4−L40v1 and MOM4−L40v2 can simulate the basic characteristics of the global oceans and ocean carbon budgetreasonably well. Both models are also capable of reproducing major large-scale variability in the oceans.The next version(under development)will incorporate the wave-induced mixing scheme developed bythe Institute of Oceanography, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Qingdao to better account for the roles ofocean waves( Qiao et al., 2004; Song et al., 2007 ).

2.4 Dynamic and thermodynamic sea icemodelThe sea ice model is an important component ofthe climate system model. This model component hasa major impact on global climate change through nonlinear interactions with the atmosphere and ocean.The sea ice model used in both BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m)is the Sea Ice Simulator(SIS), adynamic/thermodynamic sea ice model developed at GFDL( Winton, 2000 ).The horizontal resolution and sea-l and distribution of the model are identicalto those used in the ocean model(MOM−L40v1 orMOM4−L40v2, respectively).This model describessea ice thermodynamic processes according to themodel developed by Semtner(1976). The model hasthree layers in the vertical direction(i.e., a snow coverlayer and two sea ice layers of equal thickness), and divides sea ice into five categories based on thickness.It is assumed that snow cover has no heat capacity, but all sea ice layers have sensible heat capacity. Theeffects of high-salinity bubbles on heat capacity areconsidered in the upper layer. The model uses viscoelastic plasticity to calculate the internal stress ofthe sea ice, and adopts an upwind scheme for calculations of conserved quantities( e.g., sea ice density, totalice, and the heat capacity of sea ice) and other advective processes. The results of the CMIP5 multi-modelintercomparison indicate that BCC−CSM1.1 gives arelatively good simulation of sea ice in the SouthernHemisphere, but slightly overestimates sea ice duringthe winter half year in the Northern Hemisphere and underestimates sea ice during the summer half year.Overall, the model is capable of simulating decadalchanges in sea ice over the 20th century.

2.5 Climate system models2.5.1 BCC−CSM1.0BCC−CSM1.0 was developed using the NCARCommunityClimateSystemModelversion3(CCSM3)as a basis.This model has coupledBCC−AGCM2.0 with the l and surface process model CLM3, the global ocean circulation model POP, and the global dynamic/thermodynamic sea ice modelCISM. This model version was fully developed by theend of 2008. BCC−CSM1.0 has been shown to have astable performance in a number of experiments similar to the multi-model intercomparions performed during the 20th century(such as CMIP3 for IPCC AR4).The simulated increase of global surface air temperature from the late 19th century to the late 20th century is consistent with HadCRUT3 observations( Brohan et al., 2006 )when the model is forced by observed changes in GHGs, solar activity, and aerosols.This consistency indicates that BCC−CSM1.0 is inthe same class as the coupled models that participated in the intercomparisons for IPCC AR4( Editorial Committee of National Assessment Report ofClimate Change, 2011 ).

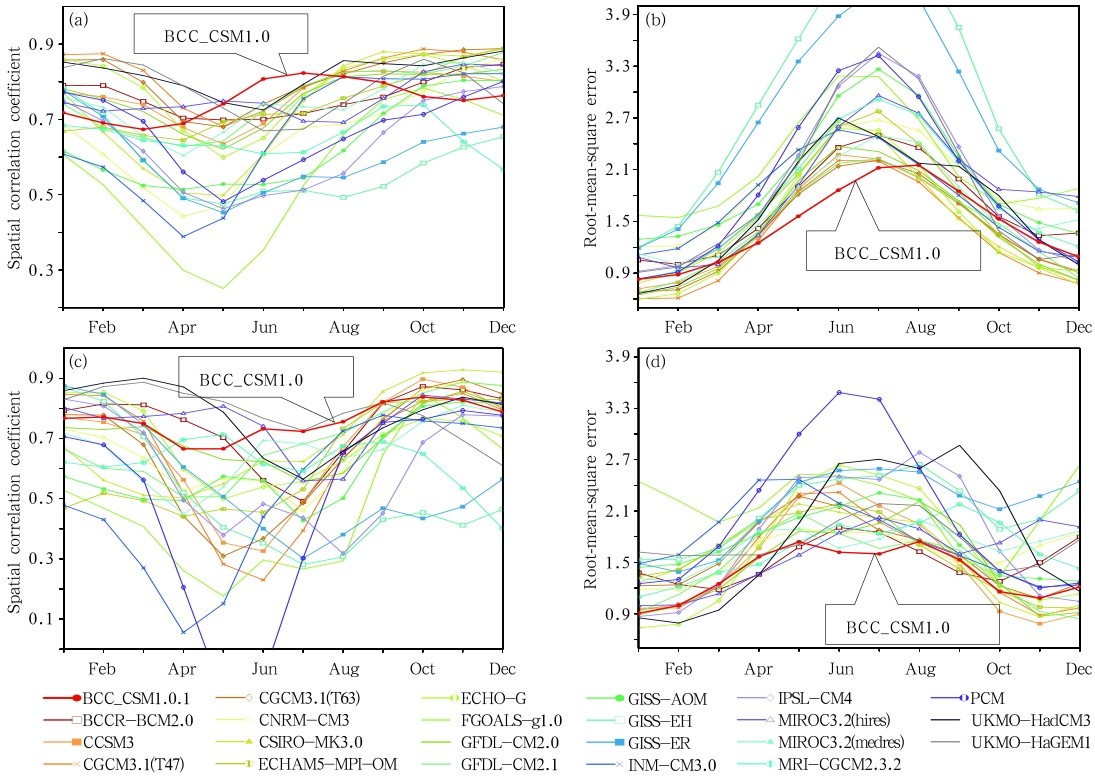

BCC−CSM1.0 can simulate the basic climatestate, seasonal changes, interseasonal oscillations, and interannual variations of global precipitation reasonably well( Zhang Li et al., 2012; Dong et al., 2013 ).It can also reproduce the climatology of summer precipitation over East Asia(Fig. 4 ).Simulationsof interannual changes in mean summer precipitation over East Asia or China during 1979–2000 byBCC−CSM1.0 have relatively high correlations withthe Xie-Arkin precipitation dataset. The root-meansquare errors are also relatively small. Zhang et al.(2011)demonstrated that the model is able to captureprecipitation and temperature extremes in East Asia.

|

| Fig. 4.(a, c)Spatial correlation coefficients and (b, d)root-mean-square errors for mean monthly precipitation over1979–1999 from models participating in the IPCC AR4 intercomparison, relative to the Xie-Arkin precipitation data forthe same period.(a, b)China and (c, d)all of East Asia. |

BCC−CSM1.1 is also based on the CCSM3 developed at NCAR. This model fully couples theatmospheric-model BCC−AGCM2.1, the l and surface model BCC−AVIM1.0, the global ocean circulation model MOM4−L40v1, and the global dynamic/thermodynamic sea ice model SIS using a fluxcoupler. Detailed descriptions of these models are provided by Wu et al.(2013). This model can simulatechanges in atmospheric CO2 concentration from anthropogenic emissions as well as the impacts of thesechanges on global climate. BCC−CSM1.1 is one of theseveral earth system models participating in the multimodel intercomparisons for IPCC AR5, and performswell in simulating the global carbon cycle( Wu et al., 2013 ) and its feedback to climate( Arora et al., 2013 ).

BCC−CSM1.1(m)is an upgraded version ofBCC−CSM1.1. BCC−CSM1.1(m)uses a horizontalresolution of T106 in the atmosphere and l and component models and the same ocean-sea ice resolutionsas BCC−CSM1.1. The atmospheric component modelis BCC−AGCM2.2, and the ocean component modelis MOM4−L40v2.

Both BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m)haveparticipated in most of the CMIP5 experiments( Xin et al., 2012 ) and have provided a large amount of simulation output for use in climate studies. More than140 peer reviewed journal papers(as of Nov. 8, 2013)have analyzed output from the BCC−CSM1.1 model(http://cmip.llnl.gov/cmip5/publications/model).The performance of both models is comparable to thatof other CMIP5 models with similar resolutions withrespect to cloud microphysics and carbon-climate feedbacks( Jiang et al., 2012; Arora et al., 2013; Su et al., 2013 ). BCC−CSM1.1 provides a reasonable simulation of the upper tropospheric jet streams and relatedtransient vortex activity over East Asia( Xiao and Zhang, 2012 ).The decadal prediction experimentsperformed under CMIP5 show that the model is capable of accurately predicting global mean surface airtemperatures on decadal scales. Decadal climate predictions using BCC−CSM1.1 have the highest skill inmid and higher latitudes over the Indian Ocean in theSouthern Hemisphere, the tropical West Pacific, and the tropical Atlantic( Gao et al., 2012 ). The followingsection evaluates simulations of the 20th century climate, the climate of the last millennium, and climatechange over the next century using BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m).

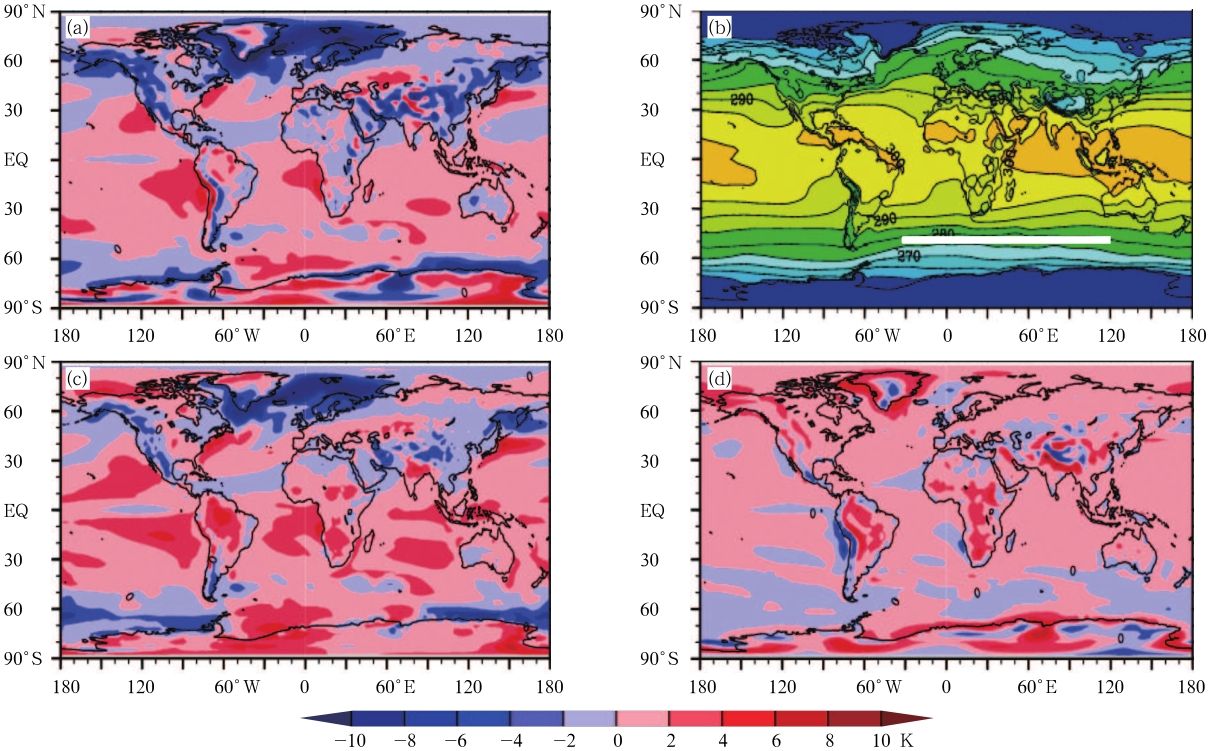

3. Climate simulations and projections usingthe BCC−CSM3.1 Simulations of the 20th century climate3.1.1Surface air temperatureEvaluation of the mean state of present-day climate in coupled models is important evidence of theirsimulation capabilities. Given external forcing by observed GHGs, natural and anthropogenic aerosols, volcanic eruptions, total column ozone, and solar activity, both BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m)effectivelycapture the global distribution of annual mean surface air temperature averaged over 1971–2000(Fig. 5 ). Significant biases relative to the ERA40 reanalysis( Uppala et al., 2005 )are concentrated in the polar areas and regions of complex topography(such asAntarctica, Greenl and , the Tibetan Plateau, the eastern coast of Africa, and the Andes along the west coastof South America).The temperature simulated bythe model near Greenl and is over 10℃ colder than thereanalysis estimate, while temperatures over parts ofAntarctica and the Tibetan Plateau are more than 6℃warmer than the corresponding reanalysis estimates.Model biases over Greenl and and in the Antarctic region may be associated with problems in the simulation of sea ice, while the large temperature bias overthe Tibetan Plateau may be due to differences betweenthe topography in the model and that of the actual terrain. Outside of these regions, absolute temperaturebiases are within ±2℃ over most other regions. Thesebiases are similar to those of models participating inthe CMIP3 multi-model intercomparison summarizedin AR4( Trenberth et al., 2007 ). The simulation of surface air temperature by BCC−CSM1.1(m)representsa slight improvement over that by BCC−CSM1.1. TheRMSE has reduced from 2.37 K in BCC−CSM1.1 to2.07 K in BCC−CSM1.1(m). Biases in surface air temperature also decrease over some regions, most notablyGreenl and and East Asia.

|

| Fig. 5. Annual-mean surface air temperature(K)averaged over 1971–2000 from(b)ERA40 reanalysis, biases relativeto ERA40 for(a)BCC−CSM1.1 and (c)BCC−CSM1.1(m), and (d)difference(℃)between the two versions of theBCC−CSM |

Precipitation is also a very important variable forevaluating model performance. Most of the 20 climate system models evaluated and analyzed for the IPCCAR4 are able to capture the large-scale zonal me and istribution of precipitation. Both BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m)can simulate the basic geographicdistribution of precipitation during the solstice seasons(Fig. 6 ). The correlation coefficient between simulations and observations is greater than 0.8( Zhang et al., 2013 ), suggesting that these two models capturethe basic characteristics of the atmospheric circulation reasonably well. Both BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m)reproduce rainy zones in the ITCZ regionover the equatorial Pacific, the South Pacific Convergence Zone(SPCZ), the Northwest Pacific region, theequatorial South Indian Ocean, and tropical Africa.

|

| Fig. 6. Mean precipitation for(a, b, c)DJF and (d, e, f)JJA from(a, d)BCC−CSM1.1, (b, e)BCC−CSM1.1(m), and (c, f)the Xie-Arkin observational data. |

Some significant asymmetries and biases still exist in these simulations of precipitation. For example, a double ITCZ appears in the tropical Pacificregion during boreal winter(DJF; see Fig. 6 ) and spring(MAM; figure omitted). This feature is particularly pronounced in BCC−CSM1.1(m). Biases in annual mean precipitation(figure omitted)manifestmainly in the high precipitation area of the equatorial Pacific ITCZ, which is slightly weak and shiftednorthward relative to observations. Rainfall over thecentral-eastern South Pacific is overestimated(leading to a positive-negative-positive chain of biases fromnorth to south over this region), while precipitationover the Indian Ocean is underestimated. The highprecipitation area over North Pacific is located toofar to the north, and the intensity of precipitation inthis region is slightly exaggerated. Precipitation overthe equatorial region in northwestern South America isoverestimated, while rainfall over the equatorial areaalong the northeastern Atlantic Ocean is underestimated. Rainfall amounts over equatorial Africa and the Eurasian continent are slightly too high, especiallyon and around the Tibetan Plateau.

ThedistributionofprecipitationinBCC−CSM1.1(m)is improved relative to that in BCC−CSM1.1 in many regions, but not all. The negative precipitation bias over the South Indian Ocean is reduced, the positive precipitation biases over northwestern South America and the Tibetan Plateau arereduced, and the negative precipitation bias over theequatorial Pacific changes to positive. However, thenegative precipitation bias over East Asia is increased, the double ITCZ is even more prevalent, precipitation in the SPCZ extends too far toward the east and not far enough toward the south, and the positive precipitation bias over the central South Pacificis increased. The overall spatial distribution of climatological mean precipitation is more realistic inBCC−CSM1.1(m)than in BCC−CSM1.1( Su et al., 2013 ).

Both BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m)canreconstruct the basic distributions of the annual tropical precipitation mode, including the equatorial antisymmetric structure of precipitation and the atmospheric circulation in the monsoon mode and thenorth-south anti-phase distribution of the equinoctialasymmetric mode over the tropical Pacific and Atlantic.These aspects of the simulations have beendescribed in detail by Zhang et al.(2013).

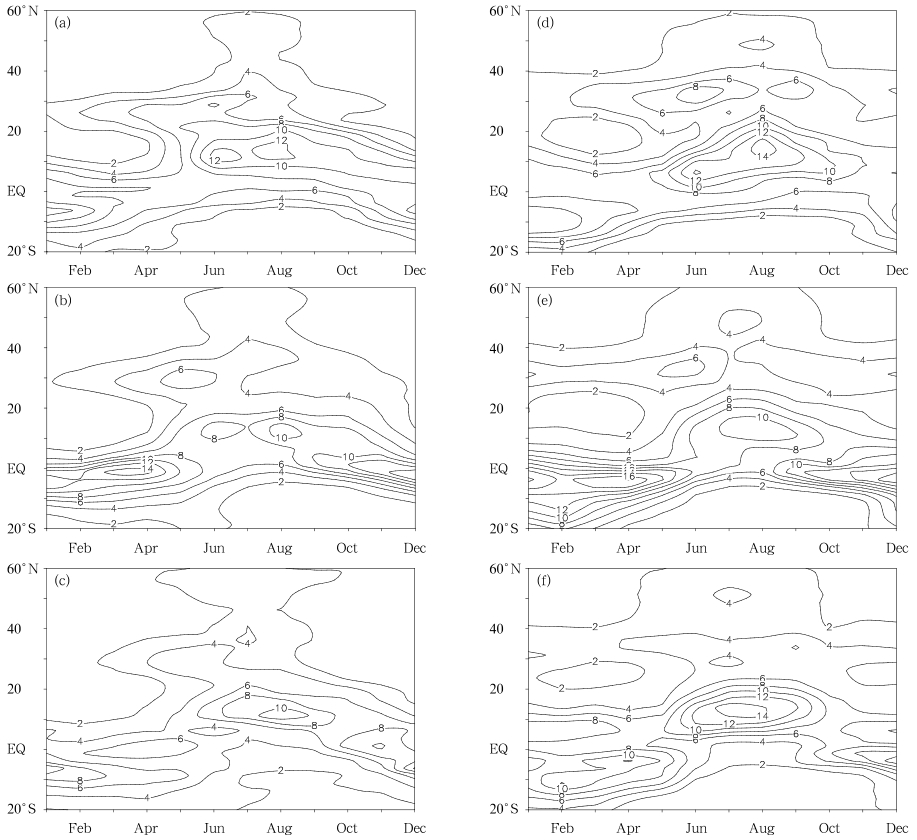

Figure 7 shows the annual cycle of mean precipitation by latitude over East Asia. These annual cycleshave been averaged over the longitudinal belts 110°–120°E and 130°–140°E to represent the seasonal cycles of rainfall over l and and sea, respectively. BothBCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m)capture the seasonal movement of the precipitation b and over EastAsia reasonably well, although they have difficultiesreproducing the exact timing and amount of precipitation. The northward movement and southward retreat of mean precipitation averaged from 110°–120°E(Figs. 7a–c)indicate that the simulated precipitationcenter from 5°to 10°S in winter is located slightlytoo far to the north, and that the intensity and duration of this precipitation center are overestimated.The timing at which the 4 mm day−1contour linefirst enters the area south of the Yangtze River is delayed by 1 month in the simulations(early March)relative to the observations(early February). The position of this contour also seems to be shifted too farto the north. These biases are even more pronouncedin BCC−CSM1.1(m). BCC−CSM1.1 underestimatesprecipitation during the rainy season over the areasouth of 30°N(especially in South China), but it overestimates the precipitation over the region north of30°N. Precipitation in the 30°–40°N latitude b and istoo large by approximately 2 mm day−1relative to theobservations, and the simulated rainb and is shifted toofar to the north. The biases in precipitation intensityin this region are reduced in BCC−CSM1.1(m)relativeto BCC−CSM1.1, although BCC−CSM1.1(m)still underestimates rainfall in the region south of 35°N and slightly overestimates precipitation in the area northof 35°N.

|

| Fig. 7. Seasonal precipitation evolution over East Asia from(a, d)the CMAP observational data, (b, e)BCC−CSM1.1, and (c, f)BCC−CSM1.1(m)averaged over the longitude belts(a, b, c)110°–120°E and (d, e, f)130°–140°E. |

The observed seasonal movement of precipitationaveraged over the 130°–140°E longitudinal b and indicates that the rainb and is quasi-stationary near 10°Sfrom December to February, while precipitation isweak from 30°–40°N(Fig. 7d ). Both models simulatethis basic feature, although the precipitation centerin the Southern Hemisphere is shifted slightly too farnorth in BCC−CSM1.1, with a longer duration and higher intensity(by 4 mm day−1)than observed. Theprecipitation intensity in the area of weak precipitation in the north is also overestimated, and the location of this area is again shifted slightly too far to thenorth. The BCC−CSM1.1(m)simulation of precipitation intensity in the region south of the equator iscloser to the observed precipitation intensity than theBCC−CSM1.1 simulation. The observations indicatethat the center of maximum precipitation reaches 5°Nin early May. This transition is delayed until late Mayor early June in the BCC−CSM1.1 simulation, and both the duration and intensity of this precipitationcenter are underestimated. The simulated transitionin BCC−CSM1.1(m)also lags slightly behind the observations, but the rainb and is pushed slightly too farto the north with an intensity very close to the observed intensity. The BCC−CSM1.1(m)simulation iscloser to the observations with respect to the timing, location, and intensity of the rainb and . Both modelsunderestimate the observed intensity of the precipitation center near 30°N, and the simulated 2 mm day−1rainb and s do not move far enough north.

3.2 Simulations of climate during the last millenniumAlthough human influences on the climate system have increased substantially since the industrialrevolution, it is instructive to view the warming of the20th century(20CW)from the perspective of a longertimescale. In particular, this perspective enhances underst and ing of the mechanisms and evolution of climate change. The Medieval Climate Anomaly(MCA) and the Little Ice Age(LIA)are two typical periods of global-scale warming and cooling, respectively, withinthe last millennium. The warming during the MCAmay have approached or even exceeded the warmingin the 20th century in some areas( Moberg et al., 2005; Guiot et al., 2010 ). Comparisons of climatic characteristics during the MCA, LIA, and 20CW periods canreveal the roles and contributions of natural variability and human activity to climate change. This techniqueis especially useful for exploring the mechanisms behind climate evolution during different periods, suchas the natural medieval warming and the recent centennial warming.

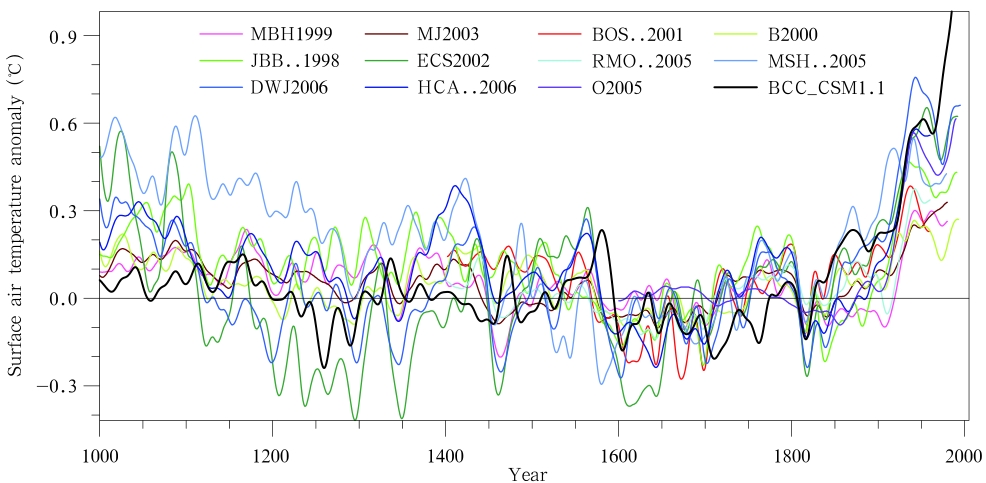

“Climate modeling for the past millennium(past1000)” is one of the core experiments in CMIP5.This experiment is helpful for evaluating model stability and transient response under different externalforcings. These external forcings include annual variations in the solar constant, volcanic activity, and GHGconcentrations from 850 to 2000 AD. Figure 8 showsthe evolution of the Northern Hemisphere mean surface temperature from BCC−CSM1.1 and 11 proxy reconstructions of surface temperature over the same domain. The uncertainties and deviations in the reconstructed time series of surface temperature are largedue to the limited quantity and quality of the underlying proxy data. The model simulations of surface temperature during the MCA are underestimated relativeto the reconstructions. Aside from the uncertainties inthe surface temperature reconstructions, this bias mayreflect uncertainties in the external forcings and themodel initial state. The agreement between the reconstructed data and the simulations is greater during theLIA period. The model reproduces three cold periodsduring the LIA: Spörer(1450–1540), Maunder(1645–1715), and Dalton(1790–1820). The climate evolution and sensitivity simulated by BCC−CSM1.1 are reasonable relative to the simulations submitted from fourother participating models(CCSM−4, CSIRO-Mk3L, GISS-E2-R, and MPI-ESM-P). Simulated surface temperatures are warmer during the MCA period th and uring the LIA period by 0.05–0.21℃. The value simulated by BCC−CSM1.1 is approximately 0.11℃, wellwithin this range. Further analyses of these simulations are under way.

|

| Fig. 8. Anomalies in surface temperature(relative to the 1500–1899 mean)over the Northern Hemisphere as simulatedby BCC−CSM1.1(black line). The colored lines represent 11 reconstructions of mean surface temperature(cf. Fig. 6.10b from Jansen et al., 2007 ). All curves are smoothed using a 30-yr low-pass filter. |

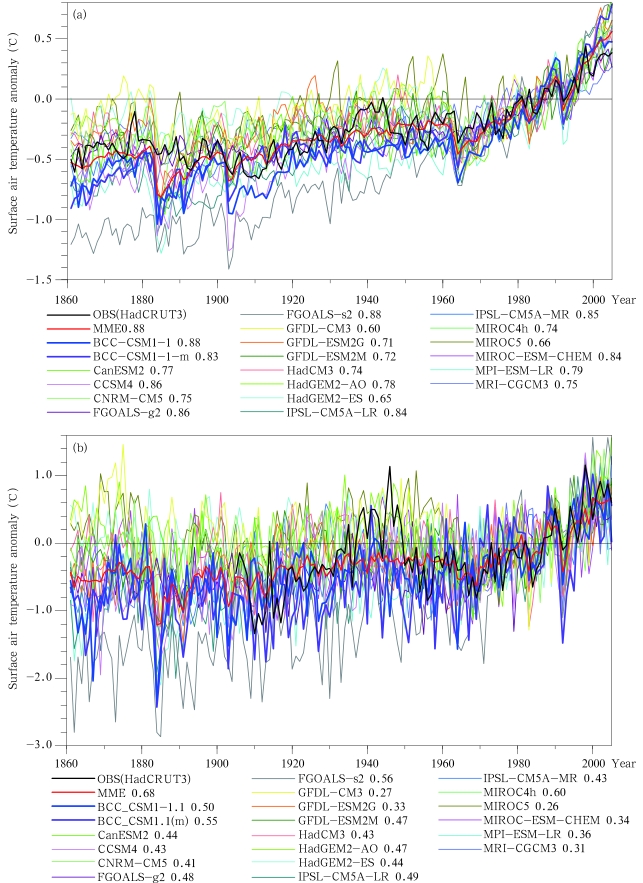

The ability of a climate system model to reproduce the 20th century climate is an important indicator of its performance and a useful criterion for judging the reliability of its future climate change projections. Xin et al.(2013b)have evaluated changes in theglobal mean air temperature from 1861 to 2005 simulated by the two climate system models developed atthe NCC, China and 18 other CMIP5 models. All ofthese models reproduce the global warming trend overthe 20th century, including the especially significantwarming over the last 50 years of the century(Fig. 9a ).The simulations by the two NCC models are largelyconsistent with the multi-model ensemble mean; however, they slightly overestimate the observed warming trend in the 20th century. The mean temperaturesimulated for the early 21st century(2000–2005)hasincreased by 0.45℃ in BCC−CSM1.1 and 0.62℃ inBCC−CSM1.1(m)relative to the mean value for 1971–2000.Both of these simulated increases are largerthan the observed increase(0.33℃). The magnitudeof the warming simulated by BCC−CSM1.1 is closerto the multi-model mean(0.48℃)than the magnitudeof the warming simulated by BCC−CSM1.1(m). Thisresult stems from the relative proximity of the climatesensitivity in BCC−CSM1.1 to the multi-model meanclimate sensitivity. The climate sensitivity is higherin BCC−CSM1.1( Zhang Li et al., 2012 ).Correlations between simulated and observed values can reflect a model’s ability to capture interannual variations in temperature. Over the period 1861–2005, thecorrelation coefficient between the BCC−CSM1.1 simulation and observations is 0.88, while that betweenthe BCC−CSM1.1(m)simulation and observations is0.83. The correlation coefficient between the multimodel ensemble mean and observations is 0.88. Therelatively large value of this correlation coefficient suggests that the multi-model ensemble mean value canbetter represent the level of model simulations thancan a single model( Zhou and Yu, 2006; Sun and Ding, 2008; Annan and Hargreaves, 2011 ). BCC−CSM1.1 istherefore regarded as being able to capture interannual variations in global mean temperature. Almostall of the coupled models have difficulties reproducingthe relative warmth of the early 20th century(approximately 1920–1940). These difficulties may be relatedto errors in assumed solar radiation, volcanic activity or other natural external forcing factors, or in therepresentation of the synergistic internal variability ofthe climate system. The relative coolness of the 1960–1970 period may be linked to the strong eruption ofthe Agung volcano in 1963. There have been several strong volcanic eruptions over the past 150 years, suchas Krakatoa in 1883, Pelee in 1902, and Pinatuboin 1991.The cooling effect of volcanic aerosols injected into the atmosphere by these eruptions mayhave caused brief periods of relatively low temperatures in the time series of global mean temperature.

|

| Fig. 9. Anomalies in annual mean surface air temperature(℃)between 1861 and 2005 relative to the 1971–2000 meanover(a)the whole globe and (b)China. The results are shown for BCC−CSM1.1, BCC−CSM1.1(m), and 18 otherCMIP5 models. The solid black curve indicates the observed time series, the solid red curve indicates the ensembleaverage from 20 members, and the thin curves indicate simulations by individual models. The numbers listed in thelegend indicate correlation coefficients between the listed model simulation and observations(global observations fromHadCRUT3, Brohan et al., 2006; China observations from Tang and Ren, 2005; redrawn by Xin et al., 2013c ). |

Figure 9b shows surface air temperature anomalies averaged over China as simulated by 20 CMIP5models. Each value is the sum of averages in three areas within the China domain(28°–50°N, 80°–97.5°E; 22.5°–43°N, 97.5°–122.5°E; and 43°–54°N, 117.5°–130°E). The range of mean surface air temperatureanomalies over China is even larger than the rangeof global mean temperature anomalies.The simulations by BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m)aresimilar to the multi-model ensemble mean, suggestingthat both models can simulate warming over Chinaduring the 20th century. Both models simulate temperature increases of 0.48℃ in the early 21st century(2000–2005)relative to the 1971–2000 climatologicalmean. These increases are lower than both the multimodel ensemble mean increase(0.63℃) and the observed increase(0.69℃). The correlation coefficient between BCC−CSM1.1 and observations during 1906–2005 is 0.50, while that between BCC−CSM1.1(m) and observations is 0.55. This result indicates thatthese two models are able to simulate interannualchanges in surface air temperature over China during the past century reasonably well.The higherresolution BCC−CSM1.1(m)performs slightly betterthan BCC−CSM1.1. The best simulation of interannual temperature changes over China is by the highresolution Japanese MIROC4h, with a correlation coefficient of 0.6. Many studies have explored the spatialdistribution of recent climate change in China. Forexample, the BCC−CSM1.1 model is able to capturechanges in springtime rainfall over eastern China( Xin et al., 2013a ).

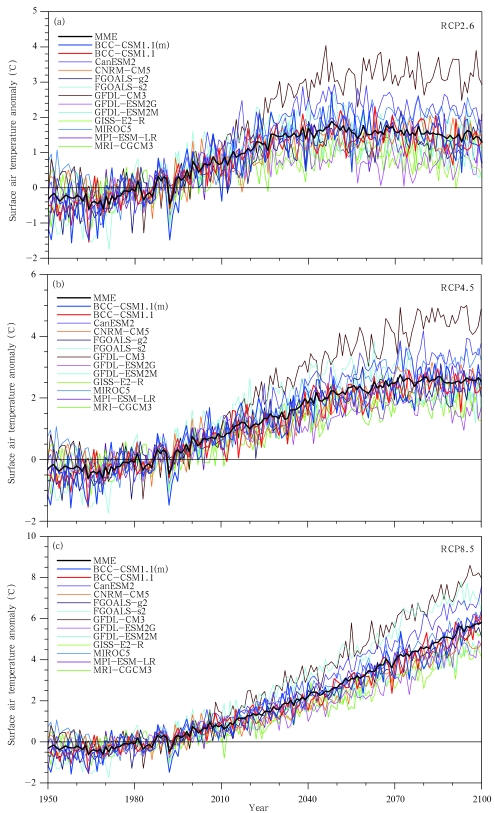

NewRepresentativeConcentrationPathway(RCP)emission scenarios are used in CMIP5 projections of climate change in the 21st century. Thosescenarios are named according to the intensity of theradiative forcing in 2100: RCP8.5, RCP6, RCP4.5, and RCP2.6. Figure 10 shows projections of mean surface air temperature over China from 13 CMIP5 models(including BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m))under the RCP2.6, RCP4.5, and RCP8.5 scenarios.Almost all the models project continued increases intemperature over China under all three scenarios. Under RCP2.6, the models project that mean temperature over China would peak around 2050, remain virtually stable from 2050 to 2070, and then decreasefrom 2070 to the end of the 21st century.Projected changes in global mean temperatures are similar( Xin et al., 2012 ). Under RCP4.5, the temperature over China would increase through 2100, althoughthe rate of this increase would slow toward the end ofthe 21st century. Under RCP8.5, all models projectcontinued increases in mean temperature over Chinathrough the end of the 21st century. BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m)are largely consistent with themulti-model ensemble mean under each of the threescenarios. This multi-model mean projects that meantemperature over China would increase by 1.4℃ under RCP2.6, 2.5℃ under RCP4.5, and 5.7℃ underRCP8.5. Xin et al.(2013c)also analyzed the changesin precipitation over East Asia projected to occur bythe end of the 21st century according to BCC−CSM1.1under all four RCP scenarios. They found that thesimulated East Asian monsoon strengthens under themedium and high emissions scenarios, while the summer mean precipitation over the Yangtze River basindecreases and the precipitation over North China increases(figure omitted).

|

| Fig. 10. Anomalies of annual-mean surface air temperature(℃)relative to the 1971–2000 mean under three RCPemission scenarios for BCC−CSM1.1, BCC−CSM1.1(m), and other CMIP5 models. The solid black line represents themulti-model ensemble mean. The thin curves indicate simulations from individual models. |

This paper provides an overview of progress inthe development of the global atmospheric general circulation, l and surface, ocean general circulation, and sea ice component models of the fully coupled climatesystem models constructed by the National ClimateCenter(NCC). The main features of the two climatesystem models and their component models are described. Their performance is then evaluated by applying several basic metrics to the large amount ofdata generated for CMIP5.Particular attention ispaid to simulations of precipitation and temperature in present-day climate and simulations of temperaturechanges over the past millennium. Differences in simulations of climate change over the past 100 years and projections of climate change over the next 100 yearsbetween BCC−CSM1.1, BCC−CSM1.1(m), and otherCMIP5 models have also been assessed. The majorconclusions can be summarized as follows.

(1)The second-generation AGCMs developed atNCC(i.e., BCC−AGCM2.0, BCC−AGCM2.1, and BCC−AGCM2.2)include substantial improvementsto the dynamic framework and physical processes.These models have demonstrated relatively good performance in simulations of current climate, includingsurface air temperature, precipitation, stratospherictemperature, and the atmospheric circulation. Modelrepresentations of seasonal changes, extreme temperatures, heavy precipitation, and tropical intraseasonaloscillations are also relatively realistic. Increasing thehorizontal resolution of BCC−AGCM has improvedsimulations of the regional distribution of precipitation to some extent.

(2)The l and surface model BCC−AVIM is capable of simulating vegetation dynamics and the l and surface carbon cycle. BCC−AVIM is a component ofboth BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m).

(3)BCC−CSM−1.0, BCC−CSM1.1, and BCC−CSM1.1(m)have shown a good ability to simulate themean climate state, long-term trends, and interannual climate changes when forced by observed GHGs, aerosols, volcanic eruptions, total column ozone, and solar variability.Simulated values of global meantemperature changes are close to the ensemble meansof models participating in the CMIP3 and CMIP5intercomparisons.The largest biases are found inpolar areas, the Tibetan Plateau region, and other areas with complex topography. The simulation of thesurface air temperature climatology by the higherresolution BCC−CSM1.1(m)is more realistic thanthat by BCC−CSM1.1.

(4)Both BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m)provide reasonable simulations of the spatial distributions of annual and seasonal mean precipitation.BCC−CSM1.1(m)is better in simulating regional precipitation, but both models still contain obvious deficiencies(such as a double ITCZ in the tropical Pacific, which is especially pronounced in BCC−CSM1.1(m)).Precipitation over East Asia is generally less intensethan observed in both models.

(5)BCC−CSM1.1 can simulate global warming and cooling episodes during the past millennium, including the Medieval Climate Anomaly(MCA) and Little Ice Age(LIA).

(6)BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m)cansimulate global climate change on centennial scales.The overall performance of each model is comparable to that of other CMIP5 models with similarresolutions.Output from the two models is generally consistent with the CMIP5 multi-model ensemblemean, although both models slightly overestimatethe observed warming trend during the 20th century.BCC−CSM1.1 projects that mean temperature overChina would increase by 1.4℃ under RCP2.6, 2.5℃under RCP4.5, and 5.7℃ under RCP8.5 by the endof the 21st century. These projections are consistentwith the CMIP5 multi-model ensemble mean.

(7)BCC−CSM1.1 and BCC−CSM1.1(m)areearth system models that can be used to simulateinterannual changes in the global concentration of atmospheric CO2under anthropogenic carbon emissionscenarios. These models have a preliminary capacityfor simulating the global carbon cycle.

Acknowledgments. The language editor forthis manuscript is Dr. Jonathon S. Wright.

| Annan, J. D., and J. C. Hargreaves, 2011: Understanding the CMIP3 multimodel ensemble. J. Climate, 24,4529-4538. |

| Arora, V. K., and G. J. Boer, 2005: A parameterization of leaf phenology for the terrestrial ecosystem com-ponent of climate models. Global Change Biol., 11,39-59, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2004.00890.x. |

| —-, —-, P. Friedlingstein, et al., 2013: Carbon-concentration and carbon-climate feedbacks in CMIP5 earth system models. J. Climate, 26, 5289-5314, doi: 10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00494.1. |

| Brohan, P., J. J. Kennedy, I. Harris, et al., 2006: Uncertainty estimates in regional and global observed temperature changes: A new data set from 1850. J. Geophys. Res., 111, D12106, doi:10.1029/2005JD006548. |

| Chen Haishan, Shi En, and Zhou Jing, 2011: Evaluation of recent 50 years extreme climate events over China simulated by Beijing Climate Center (BCC) climate model. Trans. Atmos. Sci., 34(5), 513-528. (in Chinese) |

| Chen Haoming, Yu Rucong, Li Jian, et al., 2012: The coherent interdecadal changes of East Asian climate in mid summer simulated by BCC-AGCM 2. 0.1.Climate Dyn., 39, 155-163, doi: 10.1007/s00382-011-1154-6. |

| Collins, W. D., P. J. Rasch, B. A. Boville, et al., 2004: Description of the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model (CAM3. 0). NCAR/TN-464+STR, 214 pp. |

| Ding Yinghui, Liu Yiming, Song Yongjia, et al., 2002: Research and experiments of the dynamical model system for short-term climate prediction. Climatic Environ. Res., 7(2), 236-246. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Li Qingquan, Li Weijing, et al., 2004: Advance in seasonal dynamical prediction operation in China. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 62(5), 598-612. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Ren Guoyu, Shi Guangyu, et al., 2006: National as-sessment report of climate change. Part Ⅰ: Climate change in China and its future trend. Adv. Climate Change Res., 2(1), 3-8. (in Chinese) |

| Dong Min, 2001: Introduction to National Climate Cen-ter Atmospheric General Circulation Model-Basic Principles and Applications. China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 152 pp. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Wu Tongwen, Wang Zaizhi, et al., 2009: Simula-tions of the tropical intraseasonal oscillation by the atmospheric general circulation model of the Beijing Climate Center. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 67(6), 912-922. |

| —-, —-, —-, et al., 2012: A simulation study on the extreme temperature events of the 20th century by using the BCC-AGCM. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 26(4),489-506, doi: 10.1007/s13351-012-0408-5. |

| —-, —-, —-, et al., 2013: Simulation of the precipita-tion and its variation during the 20th century using the BCC climate model (BCC_CSM-1. 0). J. Appl.Meteor. Sci., 24, 1-11. (in Chinese) |

| Editorial Committee of National Assessment Report of Climate Change, 2011: Second National Assessment Report of Climate Change. Science Press, Beijing,710 pp. |

| Gao Feng, Xin Xiaoge, and Wu Tongwen, 2012: A study of the prediction of regional and global temperature on decadal time scale with BCC_CSM1. 1 model.Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 36(6), 1165-1179, doi:10.3878/j.issn.1006-9895.2012.11243. (in Chinese) |

| Gong, S. L., L. A. Barrie, and M. Lazare, 2002: CanadianAerosol Module (CAM): A size-segregated simula-tion of atmospheric aerosol processes for climate and air quality models 2. Global sea-salt aerosol and its budgets. J. Geophys. Res., 107(D24), AAC 13-1-AAC 13-14, doi:10.1029/2001JD002004. |

| —-, —-, J. P. Blanchet, et al., 2003: Canadian aerosolmodule: A size-segregated simulation of atmospheric aerosol processes for climate and air quality models1. Module development. J. Geophys. Res., 108, AAC 3-1-AAC 3-16, doi: 10.1029/2001JD002002. |

| Griffies, S. M., A. Gnanadesikan, K. W. Dixon, et al., 2005: Formulation of an ocean model for global cli-mate simulations. Ocean Sci., 1, 45-79. |

| Guiot, J., C. Corona, ESCARSEL members, 2010: Grow-ing season temperatures in Europe and climate forc-ings over the past 1400 years. PLOS ONE, 5(4), e9972. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009972. |

| Guo Zhun, Wu Chunqiang, Zhou Tianjun, et al., 2011: A comparison of cloud radiative forcings simulated by LASG/IAP and BCC atmospheric general cir-culation models. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 35(4),739-752. (in Chinese) |

| Hack, J. J., 1994: Parameterization of moist convection in the National Center for Atmospheric Research Community Climate Model (CCM2). J. Geophys. Res., 99, 5551-5568. |

| Jansen, E., J. Overpeck, K. R. Briffa, et al., 2007: Palaeo-climate. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Sci-ence Basis. Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, et al., Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. |

| Ji Jinjun, 1995: A climate-vegetation interaction model:simulating physical and biological processes at the surface. J. Biogeography, 22, 445-451. |

| —-, Huang Mei, and Li Kerang, 2008: Prediction of car-bon exchanges between China terrestrial ecosystem and atmosphere in 21st century. Sci. China (Ser. D), 51(6), 885-898. |

| Jiang, J. H., Su Hui, Zhai Chengxing, et al., 2012: Evaluation of cloud and water vapor simulations in CMIP5 climate models using NASA “A-Train” satellite observations. J. Geophys. Res., 117, doi:10.1029/2011JD017237. |

| Jie Weihua and Wu Tongwen, 2010: Hindcast for the1998 summer heavy precipitation in the Yangtze and Huaihe River valley using BCC-AGCM2. 0.1 model. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 34(5), 962-978. (inChinese) |

| —-, —-, Wang Jun, et al., 2013: Improvement of 6-15 day precipitation forecasts using a time-lagged ensemble method. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 30, doi:10.1007/s00376-013-3037-8. |

| Jing Xianwen and Zhang Hua, 2012: Application and evaluation of McICA cloud-radiation framework in the AGCM of the National Climate Center. Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 36(5), 945-958, doi:10.3878/j.jssn.1006-9895. (in Chinese) |

| Li Weijing, Zhang Peiqun, Li Qingquan, et al., 2005: Research and operational application of dynamical climate model prediction system. J. Appl. Meteor. Sci., 16(Suppl.), 1-11. (in Chinese) |

| Li Weiping, Liu Xin, Nie Suping, et al., 2009: Compara-tive studies of snow cover parameterization schemes used in climate models. Adv. Earth Sci., 24(5),512-522. (in Chinese) |

| Lu Chunhui, Ding Yihui, and Zhang Li, 2014: A study on numerical simulation of characteris-tics of stratospheric circulation changes with BCC-AGCM2. 1 model. Acta Meteor. Sinica, doi:10.11676/qxxb2014.006. |

| Luo Yong, Zhao Zongci, Xu Ying, et al., 2005: Pro-jections of climate chang over China for the 21st century. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 19(4), 400-406. (in Chinese) |

| Moberg, A., D. M. Sonechkin, K. Holmgren, et al., 2005: Highly variable Northern Hemisphere temperatures reconstructed from low-and high-resolution proxy data. Nature, 433(7026), 613-617. |

| Myhre, G., B. H. Samset, M. Schulz, et al., 2012: Ra-diative forcing of the direct aerosol effect from Ae-roCom Phase Ⅱ simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys.,12, 22355-22413. |

| Oleson, K. W., Y. Dai, G. Bonan, et al., 2004: Technical Description of the Community Land Model (CLM), NCAR/TN-461+STR, NCAR, Boulder, Colorado, USA. |

| Qiao Fangli, Yuan Yeli, Yang Yongzeng, et al., 2004: Wave-induced mixing in the upper ocean: Distribu-tion and application to a global ocean circulation model. Geophys. Res. Lett., 31, L11303, doi:10.1029/2004GL019824. |

| Rasch, P. J., and J. E. Kristjansson, 1998: A compari-son of the CCM3 model climate using diagnosed and predicted condensate parameterizations. J. Climate,11, 1587-1614. |

| Semtner, A. J., 1976: A model for the thermodynamic growth of sea ice in numerical investigations of cli-mate. J. Phys. Oceanogr., 6, 27-37. |

| Shen Zhen, Zhang Yaocun, Xiao Hui, et al., 2011: Ability of the model BCC-AGCM2. 0.1 to reproduce Meiyu precipitation. Meteor. Mon., 37(11), 1336-1342.(in Chinese) |

| Shi Guangyu and Zhang Hua, 2007: The relationship between absorption coefficient and temperature and their effect on the atmospheric cooling rate. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Ra., 105, 459-466. |

| Song Zhenya, Qiao Fangli, Lei Xiaoyan, et al., 2007: The establishment of an atmosphere-wave-ocean circula-tion coupled numerical model and its application in the North Pacific SST simulation. J. Hydrodyn., 22,543-548. |

| Su Hui, J. H. Jiang, Zhai Chengxing, et al., 2013: Di-agnosis of regime-dependent cloud simulation errors in CMIP5 models using “A-Train” satellite observa-tions and reanalysis data. J. Geophys. Res., 118,2762-2780, doi: 10.1029/2012JD018575. |

| Sun Ying and Ding Yihui, 2008: An assessment on the performance of IPCC AR4 climate models in sim-ulating interdecadal variations of the East Asian summer monsoon. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 22, 472-488. (in Chinese) |

| Tang Guoli and Ren Guoyu, 2005: Reanalysis of surface air temperature change of the last 100 years over China. Climatic Environ. Res., 10, 791-798. |

| Trenberth, K. E., P. D. Jones, P. Ambenje, et al., 2007: Observations: Surface and atmospheric climate change. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Sci-ence Basis. Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, et al., Eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. |

| Uppala, S. M., et al., 2005: The ERA-40 re-analysis. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 131, 2961-3012, doi:10.1256/qj.04.176. |

| Wang Lu, Zhou Tianjun, Wu Tongwen, et al., 2009: Simulation of the leading mode of Asian Australian monsoon interannual variability with the Beijing Cli-mate Center atmospheric general circulation model. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 67(6), 973-982. (in Chinese) |

| Wei Xiaodong and Zhang Hua, 2011: Analysis of optical properties of nonspherical dust aerosols. Acta Op-tica Sinica, 31(5), 0501002. |

| Winton, M., 2000: A reformulated three-layer sea icemodel. J. Atmos. Ocean Technol., 17, 525-531. |

| Wu Tongwen, 2012: A mass-flux cumulus parameteriza-tion scheme for large-scale models: Description and test with observations. Climate Dyn., 38, 725-744, doi: 10.1007/s00382-011-0995-3. |

| —- and Wu Guoxiong, 2004: An empirical formula tocompute snow cover fraction in GCMs. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 21, 529-535, doi: 10.1007/BF02915720. |

| —-, Yu Rucong, and Zhang Fang, 2008: A modified dy-namic framework for the atmospheric spectral model and its application. J. Atmos. Sci., 65, 2235-2253. |

| —-, —-, —-, et al., 2010: The Beijing Climate Centeratmospheric general circulation model: Description and its performance for the present-day climate. Climate Dyn., 34, 123-147, doi: 10.1007/s00382-008-0487-2. |

| —-, Li Weiping, Ji Jinjun, et al., 2013: Global car-bon budgets simulated by the Beijing Climate Center climate system model for the last century. J. Geophys. Res: Atmos., 118, 4326-4347, doi:10.1002/jgrd.50320. |

| Xia Kun, Luo Yong, and Li Weiping, 2011: Simulation of freezing and melting of soil on the Northeast Tibetan Plateau. Chinese Sci. Bull., 56(20), 2145-2155. |

| Xiao Chuliang and Zhang Yaocun, 2012: The East Asianupper-tropospheric jet streams and associated tran-sient eddy activities simulated by a climate system model BCC_CSM1.1. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 26(6),700-716. |

| Xie, P., and P. A. Arkin, 1997: Global precipitation: A 17-year monthly analysis based on gauge obser-vations, satellite estimates, and numerical model outputs. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 78, 2539-2558. |

| Xin Xiaoge, Wu Tongwen, and Zhang Jie, 2012: Intro-duction of CMIP5 experiments carried out by BCCclimate system model. Adv. Climate Change Res.,8, 378-382. (in Chinese) |

| —-, Cheng Yanjie, Wang Fang, et al., 2013a: Asymmetry of surface climate change under RCP2. 6 projections from the CMIP5 models. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 30,796-805, doi: 10.1007/s00376-012-2151-3. |

| —-, Wu Tongwen, Li Jianglong, et al., 2013b: How well does BCC_CSM1. 1 reproduce the 20th century climate change over China? Atmos. Oceanic Sci.Lett., 6, 21-26. |

| —-, —-, and Zhang Jie, 2013c: Introduction of CMIP5 experiments carried out with the climate system models of Beijing Climate Center. Adv. Climate Change Res., 4(1), 41-49. |

| —-, Zhang Li, Zhang Jie, et al., 2013d: Climate change projections over East Asia with BCC_CSM1. 1 under RCP scenarios. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan, 91, 413-429. |

| Zhang, G. J., and N. A. McFarlane, 1995: Sensitivity of climate simulations to the parameterization of cumulus convection in the Canadian Climate Centre general circulation model. Atmos. Ocean, 33, 407-446. |

| Zhang Hua, T. Nakajima, and Shi Guangyu, et al., 2003: An optimal approach to overlapping bands with correlated k-distribution method and its application to radiative calculations. J. Geophys. Res., 108,4641-4654, doi: 10.1029/2002JD003358. |

| —-, Shi Guangyu, T. Nakajima, et al., 2006a: The effects of the choice of the k-interval number on radiative calculations. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Ra., 98(1), 31-43. |

| —-, T. Suzuki, T. Nakajima, et al., 2006b: Effects of band division on radiative calculations. Opt. Eng.,45(1), 016002, doi: 10.1117/1.2160521. |

| —-, Wang Zhili, Wang Zaizhi, et al., 2012: Simulation of direct radiative forcing of aerosols and their ef-fects on East Asian climate using an interactive AGCM-aerosol coupled system. Climate Dyn., 38,1675-1693, doi: 10.1007/s00382-011-1131-0. |

| Zhang, L., M. Dong, and T. Wu, 2011: Changes in pre-cipitation extremes over eastern China simulated by the Beijing Climate Center Climate System Model (BCC_CSM1. 0). Climate Res., 50, 227-245. |

| —-, Wu Tongwen, Xin Xiaoge, et al., 2012: Projectionsof annual mean air temperature and precipitation over the globe and in China during the 21st century by the BCC Climate System Model BCC_CSM1. 0.Acta Meteor. Sinica, 26(3), 362-375. |

| —-, Wu Tongwen, Xin Xiaoge, et al., 2013: The annual modes of tropical precipitation simulated by Beijing Climate Center climate system model (BCC_CSM). Chinese J. Atmos. Sci., 37(5), 994-1012. (in Chi-nese) |

| Zhang Minhua, Lin Wuyin, C. S. Bretherton, et al., 2003: A modified formulation of fractional stratiform con-densation rate in the NCAR community atmospheric model (CAM2). J. Geophys. Res., 108(D1), ACL10-1-ACL 10-11, doi: 10.1029/2002JD002523. |

| Zhang Peiqun, Li Qingquan, Wang Lanning, et al., 2004: Development and application of dynamic climate model prediction system in China. Sci. Technol. Rev., 7, 17-21. |

| Zhao Shuyun, Zhi Xiefei, Zhang Hua, et al., 2013: A primary assessment of the simulated cli-matic state by a coupled aerosol-climate model BCC-AGCM2. 0.1-CAM. Climatic Environ. Res.,doi: 10.3878/j.issn.1006-9585.2012.12015. |

| Zhao Zongci, Wang Shaowu, Xu Ying, et al., 2005: At-tribution of the 20th century climate warming inChina. Climatic Environ. Res., 10(4), 808-817. (inChinese) |

| Zhou Tianjun and Yu Rucong, 2006: Twentieth-century surface air temperature over China and the globe simulated by coupled climate models. J. Climate,19, 5843-5858. |

| Zhou Wenyan, Luo Yong, and Li Yunmei, 2010: Val-idation of the radiative transfer parameterization scheme in land surface process model. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 68(1), 12-18. (in Chinese) |

2014, Vol. 28

2014, Vol. 28