The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- MA Zhanhong, FEI Jianfang, HUANG Xiaogang, CHENG Xiaoping, LIU Lei . 2013.

- Evaluation of the Ocean Feedback on Height Characteristics of the Tropical Cyclone Boundary Layer

- J. Meteor. Res., 28(6): 910-922

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-013-0611-z.

Article History

- Received May 21, 2013;

- in final form September 8, 2013

The boundary layer is referred to as the lowestportion of the atmosphere, which is directly influenced by the presence of the earth's surface(Stull, 1988; Holton, 2004). The boundary layer of a tropical cyclone(TC)is recognized as a crucial part thatconstrains the energy transport processes between theTC and the underlying surface(Smith et al., 2009).A TC viewed as a heat engine extracts energy fromthe underlying ocean via a form of heat fluxes and loses energy by the surface friction, so the balancerelationship between the entropy production and thesurface dissipation in the boundary layer determinesthe maximum potential intensity that a TC could attain(Emanuel, 1986, 1988, 1995). Numerical simulation studies have shown that the application of unrealistic boundary layer structures, such as the depthaveraged or balanced boundary layer, will hinder substantially the accuracy of TC simulations(Smith and Montgomery, 2008; Kepert, 2010a, b). Therefore, underst and ing the boundary layer characteristics of theTC is essential for improving the TC intensity forecast, which has been an ongoing effort in the past decades(e.g., Kepert, 2006a, b; Nolan, 2009a, b; Zhang et al., 2009).

As one crucial element of the boundary layer characteristics, the definition of the boundary layer depthis nonetheless controversial. One of the commonlyused definitions is referred to as the thermodynamic boundary layer adopted by Anthes and Chang(1978), who took the boundary layer top at a level where thevirtual potential temperature θv is 0.5 K larger thanthe surface value(θv at the lowest model level). Inessence, this definition considers the boundary layer tobe a thermodynamically well-mixed layer. The othercommon definitions can be classified as the dynamical boundary layer(e.g., Bryan and Rotunno, 2009;Smith et al., 2009). Bryan and Rotunno(2009)tookthe boundary layer top to be the height of the maximum tangential wind, assuming that in the boundary layer, the turbulent force is important and manipulated by surface interaction. Smith et al.(2009)adopted another dynamical boundary layer definitionbased on the inflow layer in the TC, which is considered to be aroused by the breakdown of gradientwind balance due to surface friction. Nonetheless, thefriction-induced inflow is generally difficult to be separated from the convection-induced inflow. These definitions of the boundary layer depth based on valuablessuch as θv, maximum tangential wind, and radial inflow are denoted as HVTH, HTAN, and HRAD, respectively. Zhang et al.(2011)examined 794 GPSdropsondes in 13 hurricanes to study the characteristic height scales of the TC boundary layer in termsof HVTH, HTAN, and HRAD. The thermodynamicboundary layer height is found to be much shallowerthan the dynamical boundary layer height, and theboundary layer height decreases with decreasing radiusto the TC center for all boundary layer definitions.The different height scales by different boundary layerdefinitions reveal that further study is required towarda thorough underst and ing of the boundary layer structure. Their study was centralized in the symmetriccharacteristics of the TC boundary layer, while theasymmetric characteristics of the TC boundary layerwere not examined, presumably due to the limitationof available observation data.

Recent studies on air-sea interaction have shownthat moving TCs cause an asymmetric decrease of thesea surface temperature(SST), which conversely imposes significant influences on the TC intensity and internal structures(e.g., Schade and Emanuel, 1999;Bender and Ginis, 2000; Zhu et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2010; Duan et al., 2013). However, investigations into the impacts of ocean feedback onTC boundary layer structures are quite limited, especially on the TC boundary layer height. As a follow-upstudy of our idealized modeling work on the TC-oceaninteraction, this study aims to evaluate the effects ofSST cooling induced by a moving TC on the characteristic height of the TC boundary layer using themodel output in Ma et al.(2013a, b). The remainder context is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the model configuration. Section 3 analyzes themodel results in detail, followed by the conclusion inSection 4.2. Model configuration

This study utilizes the similar model configuration in Ma et al.(2013a). The coupled atmosphereocean model used in this study is developed by Liuet al.(2011b), which is composed of the Weather Research and Forecasting(WRF)model version 3.1(Skamarock et al., 2008)as the atmospheric component and the Princeton Ocean Model(POM; Mellor, 2004)as the oceanic component. The WRF model providesthe surface wind stress, surface heat fluxes(includinglatent heat flux and sensible heat flux), and radiationfluxes to the POM model, while the POM model transfers back the SST to the WRF model. The variablesare exchanged between the two models every 900 s.

The WRF model contains three domains withhorizontal resolutions of 15, 5, and 1.67 km, and dimensions of 220 × 220, 202 × 202, and 202 × 202, respectively, with the inner two meshes moving withthe storm translation. The Betts-Miller-Janjic scheme(Betts and Miller, 1986)is used on the outmost mesh.The YSU scheme(Hong et al., 2006)is employed to parameterize the boundary layer processes. There are 36levels placed as default in the vertical direction and theinitial SST is set uniformly to be 29℃ following someother idealized TC-ocean coupling studies(e.g., Liu et al., 2011a). The environmental temperature and humidity are given using the mean tropical sounding of Jordan(1958). Uniform easterly winds are specifiedat all levels, within which a bogus vortex possessing a maximum wind speed of 24 m s-1 is then implanted.The WRF model is initially integrated individually for24 h as the model spin-up period.

In the POM model, the horizontally uniform temperature and salinity profiles are given by the monthly(August)averaged Simple Ocean Data Assimilation(SODA)profiles at 20.25°N, 176.25°E as the initial and boundary conditions, except that the temperaturein the ocean mixed layer and at the sea surface is mod-ified slightly to be 29℃ The domain has grid pointsof 185×165 and a horizontal resolution of 0.2°×0.2°covering a region slightly larger than that of the WRFmodel. Two experiments with and without couplingof the ocean model are conducted, denoted as CTRL and UNCP, respectively. The model is integrated fora total of 96 h.3. Results3.1 Storm intensity evolution

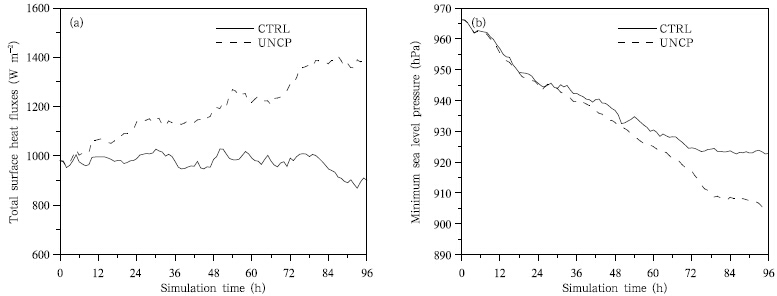

Because Ma et al.(2013a)have shown detailedocean responses that agree well with previous observations and modeling results, i.e., the right bias of thecold wake, this study will focus on the atmosphere responses caused by the SST cooling. Model results indicate that the cold wake is continually strengthenedwith the storm intensifying(figure omitted), which inturn cuts down the upward surface heat fluxes considerably(Fig. 1a). The difference of surface heat fluxesbetween CTRL and UNCP enlarges so drastically withtime that at the end of the simulation the surface heatfluxes in CTRL are diminished by as large as 50% relative to UNCP. Figure 1b exhibits the time evolutionof the TC intensity in terms of the minimum sea levelpressure. The storm in CTRL intensifies much moreslowly than that in UNCP and reaches its steady stateat about 72 h, while the storm in UNCP still intensifiessteadily. As a result, the intensity difference betweenCTRL and UNCP enlarges gradually. At the end ofthe simulation, CTRL produces a storm that is about20 hPa weaker than that in UNCP, suggesting thatthe TC intensification is significantly hindered by thecold wake through reducing the surface heat fluxes.

|

| Fig. 1.(a)The azimuthally averaged total heat fluxes(W m-2). The averaging is done within a 150-km radius of the storm center.(b)Time series of the minimum sea level pressure(hPa). |

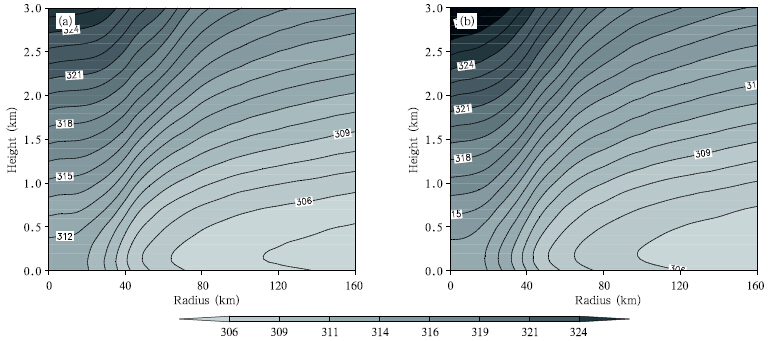

Figure 2 shows the low-level azimuthally averagedθv for CTRL and UNCP. It indicates that there exists a well-mixed layer just above the surface, which isdeepest in the outer-core region. The depth of thewell-mixed layer decreases with the radius decreasing. The virtual potential temperature is much largeraround the storm center, an indication of the existence of the warm-core structure. Compared withUNCP, CTRL produces smaller θv over the wholeregion, which evidences the cooling effects of the cold wake on the low-level atmosphere.

|

| Fig. 2.Height-radius cross-sections of the azimuthally and temporally averaged virtual potential temperature(K)from 72 to 84 h for(a)CTRL and (b)UNCP. |

Because of no consensus on a proper definitionof the TC boundary layer, three commonly used definitions, i.e., HVTH, HRAD, and HTAN, are summa-rized and compared in Fig. 3. Considering that theinflow layer comprises of both the inflow arising fromthe surface friction and the inflow arising from thebalance response to convective heating, here HRAD istaken as the height where the radial velocity is 10%of the peak inflow following Zhang et al.(2011). Inthe eye region, the winds are rather weak, so calculations in this region will inevitably introduce somebias. Thus, the calculation of dynamical boundarylayer height is not conducted within a radius of 15km from the TC center, similar to the work of Zhanget al.(2011). For both experiments, the boundarylayer height in terms of all three definitions is shownto decrease with radius decreasing in the inner-coreregion, consistent with previous theoretical and observational studies(Kepert and Wang, 2001; Schneider and Barnes, 2005; Zhang et al., 2011). The radial gradients of HRAD and HTAN are much more significantin the eyewall region than that of HVTH, since the dynamical characteristics in the inner core change dras-tically outward, while the radial changes of thermodynamic characteristics are relatively smoother. HVTHis much shallower than HRAD and HTAN, especiallyin the outer region, where a difference exceeding 300 mis found. The difference between HRAD and HTANis comparatively small and HTAN is approximately50{200 m shallower than HRAD, suggesting that theheight of maximum tangential winds is within the inflow layer(Zhang et al., 2011). Nonetheless, their difference is expected to be enlarged if the height of zeroradial velocity is used as the top of the boundary inflow layer. Evidently, the SST cooling induced by theTC has reduced the boundary layer depth in terms ofall three definitions. The decrease of HVTH is quitesmall, only less than 100 m, and varies little with the radius changing. HRAD and HTAN are reduced byabout 100{300 m, together with the weakened tangential and radial winds in CTRL(see Ma et al., 2013a).

|

| Fig. 3.Radial distributions of the azimuthally and temporally averaged depth of the TC boundary layer(m)from 72 to 84 h. |

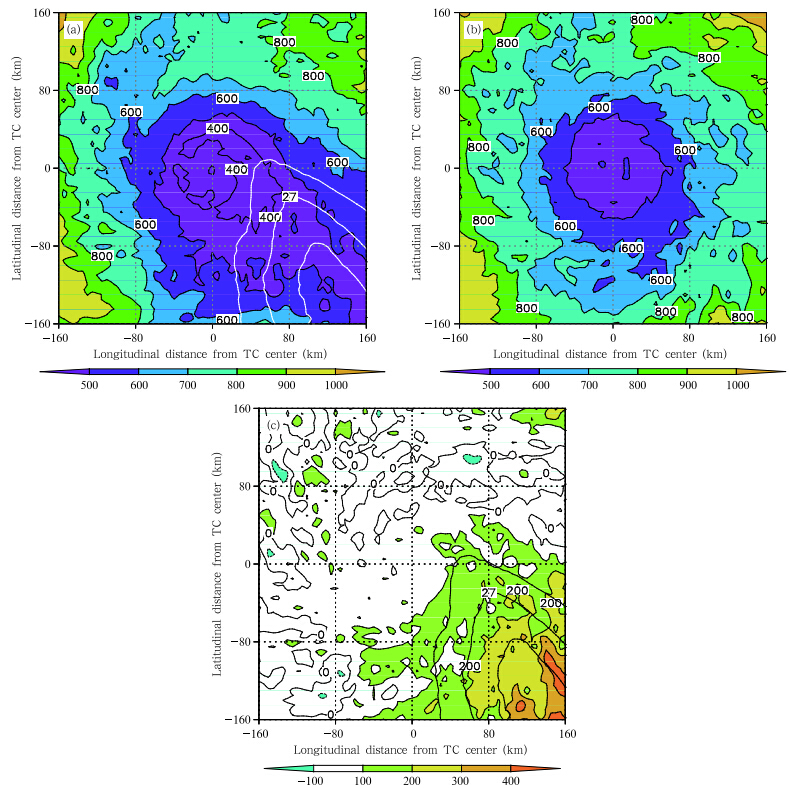

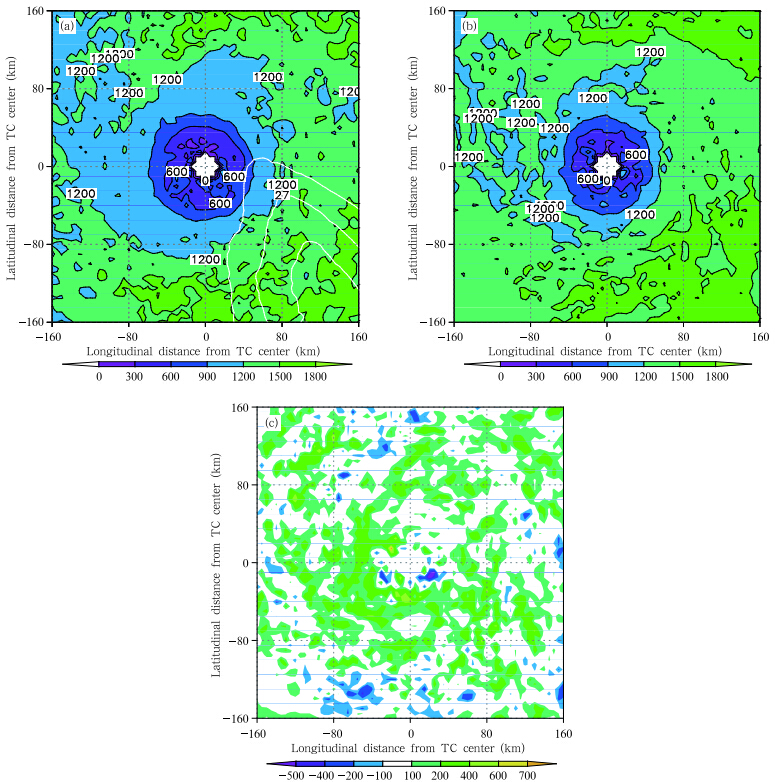

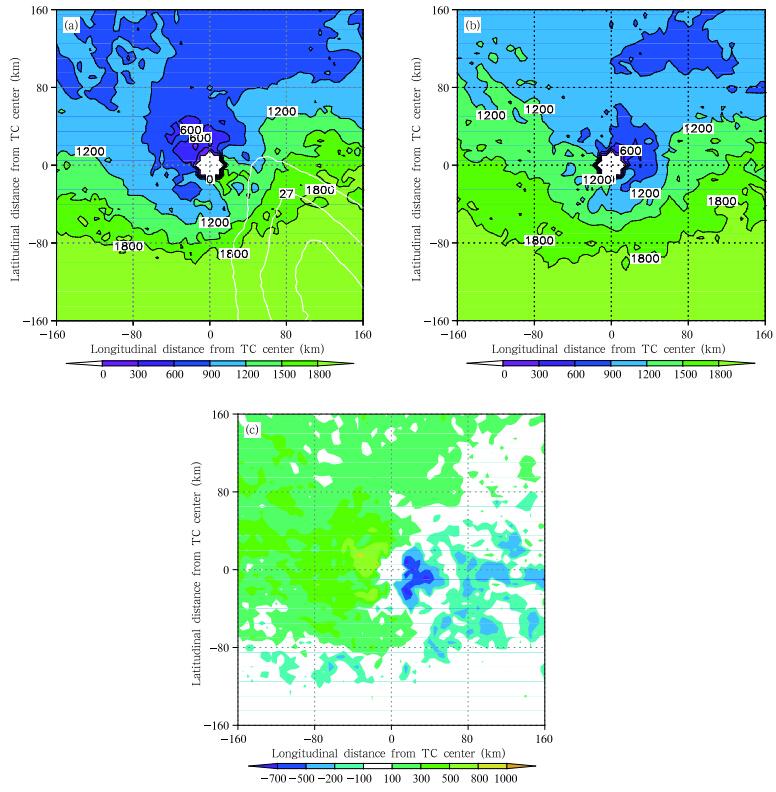

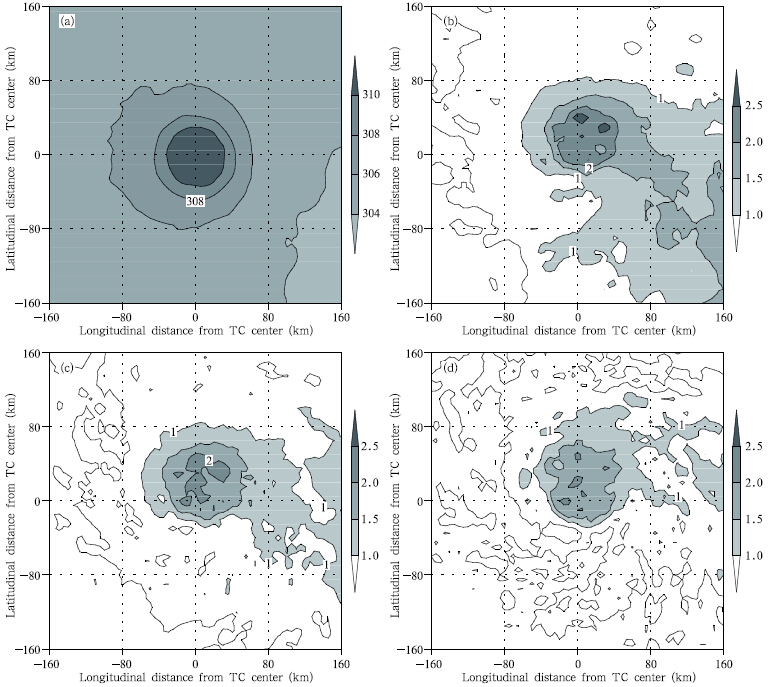

To evaluate the changes in horizontal distributions of thermal boundary layer height caused by theocean coupling, the plan views of HVTH are exhibitedin Fig. 4 for CTRL, UNCP, and their difference. Asexpected, the lowest boundary layer height appears inthe storm center, while the boundary layer is muchdeeper in the outer periphery for both runs. TheHVTH in UNCP exhibits a quite symmetric featuresince the SST is uniformly 29℃ Relatively symmetricboundary layer depth also occurs in CTRL except in the right-rear quadrant, where the boundary layer isdistinctly shallower arising from the cooling effects ofthe cold wake. The horizontal difference of HVTH between CTRL and UNCP suggests that the influencesof the ocean feedback on thermodynamic boundarylayer depth mainly exist just in the region above thecold wake, where the decrease of HVTH could attainas significant as 400 m. In other quadrants, however, the ocean feedback has little impact since the difference of HVTH between CTRL and UNCP is generallyless than 100 m. Figure 5 compares the plan viewsof HTAN for CTRL and UNCP. Considering that thetangential winds could possess a local maximum in themid troposphere, especially in the regions where thevortex hot towers are active, a peak value of 2 km isconfined for the HTAN. Both runs are shown to possess relatively symmetric HTAN, indicating that theimpacts of the cold wake on the asymmetric featuresof HTAN are unobvious, which is in contrast with theresponse of HVTH. The decrease of HTAN in CTRLrelative to that in UNCP appears not only in the rightrear quadrant but also in other regions(Fig. 5c), wherein the difference of HTAN between the two experiments mostly ranges from 100 to 400 m aroundthe eyewall region.

|

| Fig. 4.Plan views of the azimuthally and temporally averaged HVTH(m)for(a)CTRL, (b)UNCP, and (c)UNCPCTRL from 72 to 84 h. The averaged SST(K)is also shown in(a)with white contours and (c)with black contours. |

|

| Fig. 5.Plan views of the azimuthally and temporally averaged HTAN(m)for(a)CTRL, (b)UNCP, and (c)UNCPCTRL from 72 to 84 h. The averaged SST(K)is also shown in(a)with white contours. |

Figure 6 exhibits the horizontal distributions of HRAD for CTRL and UNCP as well as their difference. The value of HRAD is taken as zero in the region where the inflow layer does not exist. Similar as HTAN, a peak value of 2 km is confined for HRAD. The horizontal distributions of HRAD are shown to be highly asymmetric, in contrast with the feature of HTAN. The HRAD reaches nearly 2000 m in the south while is merely less than 600 m in the north of the storm for both experiments. The typical feature of the TC boundary layer, i.e., boundary layer depth increases with radius, is distinct in the south of the TC but not evident in the north. Large discrepancy of HRAD exists between CTRL and UNCP(Fig. 6c), though the horizontal changes of HRAD are not coincident with location of the cold wake. Compared with UNCP, CTRL produces clearly shallower HRAD in the north and northwest of the TC but deeper HRAD in the east of the TC, which is presumably associated with their different distributions of the inflow velocity. Although the dynamical definition of surface frictioninduced inflow layer is advocated by recent studies to represent the TC boundary layer(e.g., Smith and Montgomery, 2010; Zhang et al., 2011)based on the fact that turbulent momentum fluxes are near zero at the top of the inflow layer(Zhang et al., 2009), the inflow layer does not always exist in all regions at some simulation times(figure omitted). It evidences the inadequacy of HRAD in fully representing the characteristics of the boundary layer depth.

|

| Fig. 6.As in Fig. 5, but for HRAD. |

In order to explore the mechanisms leading to the differences of boundary layer depth between CTRL and UNCP in terms of HVTH, HTAN, and HRAD, the changes in the thermodynamic and dynamical features of the simulated TC boundary layer caused by the cold wake are analyzed in this section. Although the horizontal distributions of θv for CTRL at the lowest model level(approximately 30 m)are relatively symmetric(Fig. 7a), there exists much lower θv in the right-rear quadrant of the storm. A maximum value exists in the TC center, which is primarily due to the high relative humidity and large potential temperature in the eye region. Comparison of the difference of θv between CTRL and UNCP finds that θv is evidently reduced just in the right-rear quadrant and in the inner-core region(Fig. 7b). The parameter θv above the cold wake is approximately 1{1.5 K diminished, indicating that the surface air parcels are directly cooled by the SST decrease. The decrease of θv in the storm eye is more significant, exceeding 2 K, which is probably related to the intensity difference between CTRL and UNCP since the SST changes little in the eye region(Ma et al., 2013a). From Figs. 7c and 7d, θv in the storm eye still shows smaller values at upper levels, while the decrease of θv caused directly by the SST cooling rotates cyclonically and vanishes gradually with height. At the height of 1 km, the decrease of θv outside the eye region is quite weak and rotates to the northeast of the TC(Fig. 7d). Based on the definitions of HVTH, the horizontal differences of θv between CTRL and UNCP at different heights suggest that the cold wake-induced changes in the horizontal features of the HVTH are largely attributed to the decrease of θv at the lowest model level caused by the SST decrease. The decreased θv rotates and ascends with the rapid tangential winds and vertical motions and vanishes gradually with height, and thus at higher levels, the decreased θv in the right-rear quadrant is nearly absent, which eventually results in a distinct decrease of HVTH above the cold wake region(Fig. 4c).

|

| Fig. 7. Plan views of the averaged virtual potential temperature(K)from 72 to 84 h for(a)CTRL at the lowest model level(approximately 30 m), (b)UNCP-CTRL at the lowest model level, (c)UNCP-CTRL at 500 m, and (d)UNCP-CTRL at 1 km. |

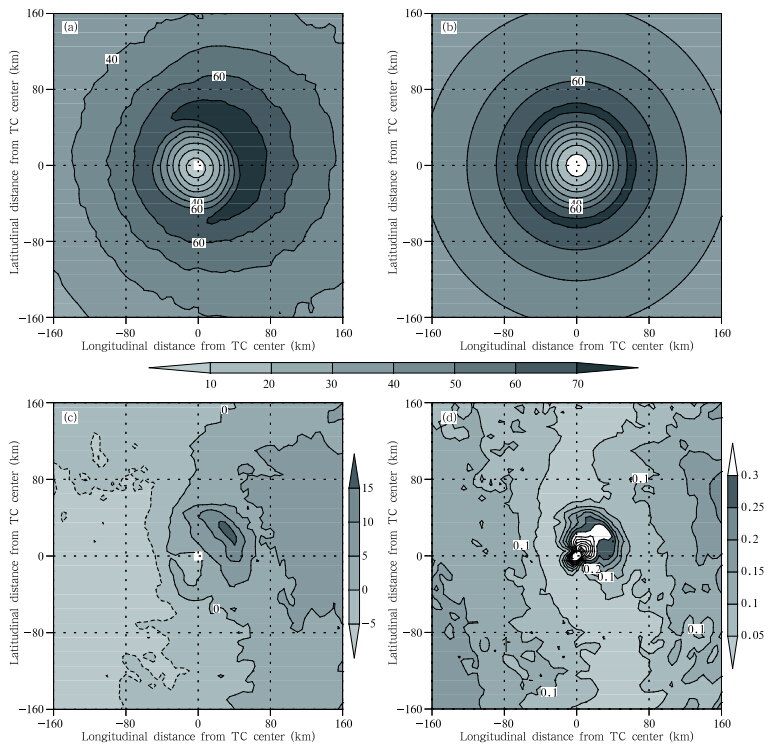

Figure 8 exhibits the azimuthally and temporally averaged low-level tangential winds, the symmetric and asymmetric components of the tangential winds, and the asymmetric ratio(obtained by dividing the absolute value of asymmetric components by symmetric components). In theory, the maximum low-level azimuthal wind should be located in the front-left quadrant of a TC(Shapiro, 1983; Kepert, 2001). However, exceptions to this situation are not uncommon in real cases(e.g., Kepert, 2006a, b). The maximum tangential winds in CTRL appear in the right of the TC(Fig. 8a), which also occurs in simulations of real TCs in Nolan et al.(2009a, b). The symmetric components account for a great majority of the total tangential winds(Fig. 8b), and possess a typical feature of the TC winds: the wind is weak in the storm eye and increases dramatically outward to a maximum at approximately a radius of 60 km, that is, the eyewall region, and then it decreases outward smoothly. As a contrast, the asymmetric components of the tangential winds are much weaker(Fig. 8c). A maximum value of about 15 m s-1 appears only in a tiny area, located at the northeast of the eyewall region. It coincides with the location of the maximum tangential winds, which is probably a sign of the supergradient winds. In most other regions, however, the asymmetric tangential winds are comparatively weak, showing values generally less than 5 m s-1. The horizontal distributions of the asymmetric components of tangential winds are dominated by left-right wavenumber-1 characteristics, which is presumably a response to the vortex translation(Shapiro, 1983; Kepert, 2001). Figure 8d shows the ratios of the asymmetric components to the symmetric components. Since the tangential winds are weak inside the eyewall region, the asymmetric ratios are correspondingly larger, giving values exceeding 0.3. In most other regions, the asymmetric ratios are quite small, ranging from less than 0.05 to 0.15. It suggests that the asymmetric components are relatively negligible in most regions relative to the symmetric components. Therefore, the asymmetric changes in HTAN caused by the cold wake are remarkably smaller than those in HVTH. Additionally, the SST decrease induced by a moving TC only produces effects on the thermodynamic properties of a storm, which changes the dynamical properties through an inefficient conversion(Hogsett and Zhang, 2009). During the conversion period, the asymmetric contributions of the SST decrease may be largely axis-symmetrized by the rapid rotation flow.

|

| Fig. 8. Plan views of the averaged 1-km tangential winds(m s-1)in CTRL from 72 to 84 h for(a)the total tangential winds, (b)the symmetric components of the tangential winds, (c)the asymmetric components of the tangential winds, and (d)the ratios of the absolute values of asymmetric components to the symmetric components. |

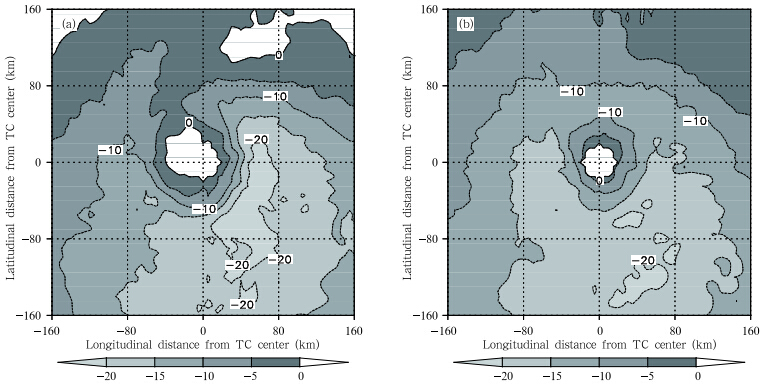

Figure 9 compares the vertically and temporallyaveraged radial inflow for CTRL and UNCP. The symmetric value of HRAD(Fig. 3)is taken as the top ofthe vertical averaging. Both runs exhibit stronger inflow in the south of the TC but weaker inflow in thenorth, corresponding to the deeper HRAD in the southof the TC but shallower HRAD in the north(Fig. 6).Of interest is that although the symmetric inflow inCTRL is evidently weaker than in UNCP(see Ma et al., 2013a), the peak value of the horizontal inflow isslightly larger in CTRL than in UNCP and covers alarger area. Nonetheless, in the north of the TC, theinflow in UNCP is evidently larger, which leads to thestronger symmetric inflow in UNCP. Besides, with the more asymmetric structures, another distinctive feature in CTRL is that the peak inflow rotates counterclockwise due to the ocean feedback, which is consistent with previous studies on TC-ocean interaction(Zhu et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2010). The cyclonical rotation of the radial inflow explains well why theHRAD in CTRL is deeper in the east but shallower inthe west compared with that in UNCP.

|

| Fig. 9. Plan views of the vertically and temporally averaged boundary-layer radial winds(m s−1)from 72 to 84 h for(a)CTRL and (b)UNCP. The symmetric HRAD is set to be the top of the vertical averaging. |

The numerical simulations using an atmosphericmodel WRF with and without coupling the oceanmodel POM are conducted and compared in this studyto investigate impacts of the ocean feedback on theheight characteristics of the TC boundary layer. Thesimulated TC in the atmosphere-ocean coupled modelleaves behind a cold wake that is consistent with theobservations. The decrease of SST caused by the TCreduces the upward heat fluxes dramatically. As a consequence, the storm intensification is greatly hindered.

In light of the controversial definitions of theTC boundary layer, three commonly used definitions, namely, HVTH, HRAD, and HTAN are examined inthis study. Results reveal that the boundary layerdepth increases with increasing radius to the stormcenter in the inner core, and HVTH is much shallower(e.g., 300 m)than HTAN and HRAD. The differencebetween HRAD and HTAN is comparatively smaller, with HTAN being 50-200 m shallower than HRAD.The ocean response reduces the depth of the boundary layer from all three definitions, in which HRAD and HTAN are reduced by about 100{300 m, whilethe decrease of HVTH is smaller, only less than 100 m.An examination of the horizontal distributions of theboundary layer depth indicates that the conventionallysymmetric definitions are insufficient to fully representthe characteristics of the boundary layer height. Thechanges of HVTH caused by the cold wake are significant in the region just above the cold wake, whereHVTH is reduced by as large as 400 m. In otherregions, however, HVTH shows little decrease. Incontrast with HVTH, the impacts of the ocean feedback on the asymmetric features of HTAN are notdistinct. Although advocated by many recent stud-ies, an essential flaw exists in the definition based onthe friction-induced inflow, that is, the absence of theinflow layer in some areas. The horizontal distributions of HRAD show remarkable asymmetric features.Under influences of the cold wake, HRAD becomes deeper in the east quadrant while shallower in thewest of the TC, an indication of the cyclonic rotationof the deepest area of HRAD.

The surface θv is evidently diminished above thecold wake region, which is identified to be dominant inthe decrease of HVTH in that region. The decreasedθv rotates and vanishes so rapidly with height thatat the height of 1 km, it has rotated to the northeast of the TC from initially the southeast quadrant.Arising from the vortex translation, the asymmetriccomponents of tangential winds are found to be dominated by the wavenumber-1 feature. In most regions, the asymmetric components of tangential winds aresubstantially smaller than the symmetric components, and thus contribute little to the whole characteristicsof HTAN. The peak inflow area rotates counterclockwise due to the ocean response, which explains wellwhy the deepest area of HRAD rotates cyclonically.

The results presented in this study have stressedthe notable influences of ocean feedback on the heightcharacteristics of the TC boundary layer. Only theSST response is considered using the atmosphere-ocean coupling model. It is expected that theatmosphere-wave coupling should be equivalently im-portant in influencing the characteristics of the TCboundary layer. This issue will be explored speciallyin a following work.

Acknowledgments: We thank the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments inimproving the manuscript.

| Anthes, R. A., and S. W. Chang, 1978: Response of the hurricane boundary layer to changes of sea surface temperature in a numerical model. J. Atmos. Sci., 35, 1240-1255. |

| Bender, M. A., and I. Ginis, 2000: Real-case simulations of hurricane-ocean interaction using a highresolution coupled model: Effects on hurricane intensity. Mon. Wea. Rev., 128, 917-946. |

| Betts, A. K., and M. J. Miller, 1986: A new convective adjustment scheme. Part Ⅱ: Single column tests using GATE wave, BOMEX, ATEX and arctic airmass data sets. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 112, 693-709.regimes. |

| Duan, Y. H., R. S. Wu, R. L. Yu, et al., 2013: Numerical simulation of tropical cyclone intensity change with a coupled air-sea model. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 27, doi: 10.1007/s13351-013-0503-2. (in press) |

| Emanuel, K. A., 1986: An air-sea interaction theory for tropical cyclones. Part I: Steady-state maintenance. J. Atmos. Sci., 43, 585-605. |

| —-, 1988: The maximum intensity of hurricanes. J. Atmos. Sci., 45, 1143-1155. |

| —-, 1995: Sensitivity of tropical cyclones to surface exchange coefficients and a revised steady-state model incorporating eye dynamics. J. Atmos. Sci., 52, 3969-3976. |

| Hogsett, W., and D.-L. Zhang, 2009: Numerical simulation of Hurricane Bonnie (1998). Part ⅡI: Energetics. J. Atmos. Sci., 66, 2678-2696. |

| Holton, J. R., 2004: An Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology. 4th ed, Elsevier Academic Press, Burlington, 529 pp. |

| Hong, S. Y., Y. Noh, and J. Dudhia, 2006: A new vertical diffusion package with an explicit treatment of entrainment processes. Mon. Wea. Rev., 134, 2318-2341. |

| Jordan, C. L., 1958: Mean soundings for the west indies area. J. Meteor., 15, 91-97. |

| Kepert, J. D., 2001: The dynamics of boundary layer jets within the tropical cyclone core. Part I: Linear theory. J. Atmos. Sci., 58, 2469-2484. |

| —-, 2006a: Observed boundary layer wind structure and balance in the hurricane core. Part I: Hurricane Georges. J. Atmos. Sci., 63, 2169-2193. |

| —-, 2006b: Observed boundary layer wind structure and balance in the hurricane core. Part Ⅱ: Hurricane Mitch. J. Atmos. Sci., 63, 2194-2211. |

| —-, 2010a: Slaband height-resolving models of the tropical cyclone boundary layer. Part I: Comparing the simulations. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 136, 1686-1699, doi: 10.002/qj.667. |

| —-, 2010b: Slaband height-resolving models of the tropical cyclone boundary layer. Part Ⅱ: Why the simulations differ. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 136, 1700-1711, doi: 10.002/qj.685. |

| —-, and Y. Q. Wang, 2001: The dynamics of boundary layer jets within the tropical cyclone core. Part Ⅱ: Nonlinear enhancement. J. Atmos. Sci., 58, 2485-2501. |

| Liu, B., H. Q. Liu, L. Xie, et al., 2011a: A coupled atmosphere-wave-ocean modeling system: Simulation of the intensity of an idealized tropical cyclone. Mon. Wea. Rev., 139, 132-152. |

| Liu Lei, Fei Jianfang, Lin Xiaopei, et al., 2011b: Study of the air-sea interaction during Typhoon Kaemi (2006). Acta Meteor. Sinica, 25, 625-638. |

| Ma, Z. H., J. F. Fei, L. Liu, et al., 2013a: Effects of the cold core eddy on tropical cyclone intensity and structure under idealized air-sea interaction conditions. Mon. Wea. Rev., 141, 1285-1303. |

| —-, —-, X. G. Huang, et al., 2013b: The effects of ocean feedback on tropical cyclone energetics under idealized air-sea interaction conditions. J. Geophys. Res., doi: 10.1002/jgrd.50780. (in press) |

| Mellor, G. L., 2004: Users guide for a three-dimensional, primitive equation, numerical ocean model (June 2004 version). Prog. in Atmos. and Ocean. Sci., Princeton University, 56 pp. |

| Nolan, D. S., J. A. Zhang, and D. P. Stern, 2009a: Evaluation of planetary boundary layer parameterizations in tropical cyclones by comparison of in-situ observations and high-resolution simulations of Hurricane Isabel (2003). Part I: Initialization, maximum winds, and the outer-core boundary layer. Mon. Wea. Rev., 137, 3651-3674. |

| —-, D. P. Stern, and J. A. Zhang, 2009b: Evaluation of planetary boundary layer parameterizations in tropical cyclones by comparison of in situ observations and high-resolution simulations of Hurricane Isabel (2003). Part Ⅱ: Inner-core boundary layer and eyewall structure. Mon. Wea. Rev., 137, 3675-3698. |

| Schade, L. R., and K. A. Emanuel, 1999: The ocean's effect on the intensity of tropical cyclones: Results from a simple coupled atmosphere-ocean model. J. Atmos. Sci., 56, 642-651. |

| Schneider, R., and G. M. Barnes, 2005: Low-level kinematic, thermodynamic, and reflectivity fields associated with Hurricane Bonnie (1998) at landfall. Mon. Wea. Rev., 133, 3243-3259. |

| Shapiro, L. J., 1983: The asymmetric boundary layer flow under a translating hurricane. J. Atmos. Sci., 40, 1984-1998. |

| Skamarock, W. C., J. B. Klemp, J. Dudhia, et al., 2008: A Description of the Advanced Research WRF Version 3. NCAR Tech. Note NCAR/TN-475+STR, 113 pp. |

| Smith, R. K., and M. T. Montgomery, 2008: Balanced boundary layers used in hurricane models. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 134, 1385-1395. |

| —-, and —-, 2010: Hurricane boundary-layer theory. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 136, 1665-1670, doi:10.1002/qj.679. |

| —-, —-, and N. Van Sang, 2009: Tropical cyclone spinup revisited. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc., 135, 1321-1335. |

| Stull, R. B., 1988: An Introduction to Boundary Layer Meteorology. Kluwer Academic Publishers, 666 pp. Wu, L. G., B. Wang, and S. A. Braun, 2005: Impact of air-sea interaction on tropical cyclone track and intensity. Mon. Wea. Rev., 133, 3299-3314. |

| Zhang, J. A., W. M. Drennan, P. G. Black, et al., 2009: Turbulence structure of the hurricane boundary layer between the outer rainbands. J. Atmos. Sci., 66, 2455-2467. |

| —-, R. F. Rogers, D. S. Nolan, et al., 2011: On the characteristic height scales of the hurricane boundary layer. Mon. Wea. Rev., 139, 2523-2535. |

| Zhu, H. Y., W. Ulrich, and R. K. Smith, 2004: Ocean effects on tropical cyclone intensification and innercore asymmetries. J. Atmos. Sci., 61, 1245-1258. |

2013, Vol. 28

2013, Vol. 28