The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- CHEN Jiong, ZHENG Yongguang, ZHANG Xiaoling, ZHU Peijun. 2013.

- Distribution and Diurnal Variation of Warm-Season Short-Duration Heavy Rainfall in Relation to the MCSs in China

- J. Meteor. Res., 28(6): 868-888

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-013-0605-x

Article History

- Received June 13, 2013;

- in final form November 19, 2013

2 Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310027

Short-duration heavy rainfall(SDHR)is one typeof severe convective weather that occurs in China.SDHR events can lead to urban waterlogging and geological disasters. For example, debris flow resulting from an SDHR event in Zhouqu, Gansu Provinceon 8 August 2010 caused approximately 2000 deaths.SDHR has therefore become an important focus ofweather forecasting in China. The Central Meteorological Office of China defines SDHR as hourly rainfallin excess of 20 mm, while heavy rainfall in China isdefined as daily rainfall in excess of 50 mm. In China, both SDHR and heavy rainfall are mainly producedby mesoscale convective systems(MCSs) and generally accompanied by thunder and lightning. The definition of SDHR emphasizes rain produced by strongconvective systems with a short duration. Heavy rainusually lasts a longer time and includes both convective and stratiform precipitation.

The climatological distribution of SDHR overChina has not yet been studied. Previous studies havefocused mainly on the distributions of heavy rainfall(> 50 mm day−1), extreme precipitation, thunderstorms, and hail over China(Zhang and Lin, 1985;China Meteorological Administration, 2007; Shen et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2011). Zheng et al.(2007, 2008)used geostationary satellite observations of infrared equivalent black body temperature(TBB)tostudy the climatological distribution of deep convection over Beijing and China, respectively. Wang and Cui(2012)studied the organizational structure ofMCSs in the middle and lower reaches of YangtzeRiver during the Meiyu period.

Yu et al.(2007a, b)showed the relationship between the duration and diurnal variations of rainfallover China during summer using hourly rainfall data.Li et al.(2008a)used hourly raingauge data to studydiurnal variations in summer precipitation over Beijing, while Li et al.(2008b)used similar data to derive seasonal variations in the diurnal cycle of rainfall in southern contiguous China. Zhou et al.(2008)studied rainfall during the East Asian summer monsoon period using satellite products and raingaugerecords. They characterized the spatial patterns ofJune–August mean precipitation amount, frequency, and intensity, as well as the diurnal and semidiurnalcycles of rainfall. However, their study neglected thediurnal variations of rainfall in spring and autumn and did not analyze the distribution of SDHR over China.Chen et al.(2010)investigated the influences of largescale forcing on the diurnal variation of summer rainfall along the Yangtze River using hourly observationalrecords and reanalysis data at 6-h intervals. Yao etal.(2009)analyzed the spatial and temporal distributions of hourly rainfall greater than 8 mm and lessthan 8 mm based on hourly records from 485 stationsin China between 1991 and 2005. These studies havemade important contributions to current underst and ing of diurnal variation, persistence, and propagationof precipitation, and causes of precipitation climatechange. However, they have not properly characterized the distribution of SDHR, due in part to the relatively low occurrence frequency of SDHR caused bysevere convection. Recently, Zhang and Zhai(2011)analyzed temporal and spatial distributions of the frequency of precipitation events with rain rates exceeding 20 and 50 mm h−1 using hourly precipitation datafrom 1961 to 2000. They also studied diurnal variations and trends in extreme precipitation during thewarm season(May–September).

Although summer is the main season for heavyrain in China, convective weather also occurs frequently during spring and autumn in southern China(Huang et al., 1986). This paper uses hourly precipitation data taken over the period 1991–2009 to analyzethe climatological characteristics of SDHR during thewarm season(April–September).These characteristicsare then compared with the climatological characteristics of MCSs as indicated by geostationary satelliteobservations of low TBBs(6 –52℃). The purpose ofthis study is to improve underst and ing of the climatology of severe convective weather and to provide aclimatological foundation for forecasting these types ofweather events.2. Data and methods

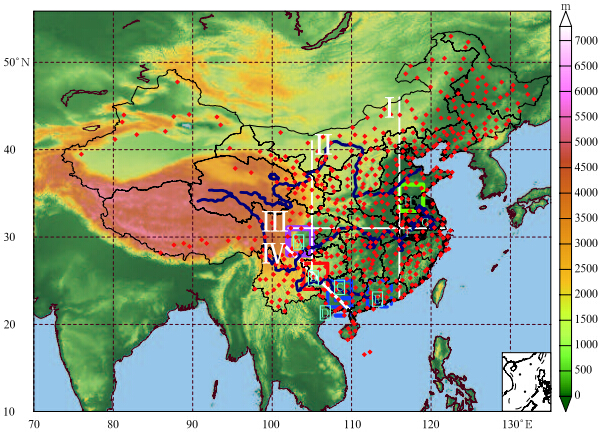

The hourly rainfall data are provided by the National Meteorological Information Center of China.This dataset is basically the same as that used by Yu et al.(2007a) and Yao et al.(2009). The dataused in this paper cover the period April–Septemberof 1991–2009, and were collected at 876 observationstations over mainl and China, including almost all ofthe first- and second-class national stations in Chinaexcept those in Taiwan. Hourly rainfall refers to 1-hcumulative rainfall during the previous hour. From these observations, we selected 15 yr of observationstaken at 549 stations(Fig. 1). The average distancebetween two neighboring stations is approximately 100km. In general, the densest observations occur in eastern China.

|

| Fig. 1. Orography and geography of China(shading), with selected meteorological observation stations(red dots) and analysis regions(white solid lines labeled I, Ⅱ, Ⅲ, and Ⅳ denote the positions of different cross-sections; rectangles labeled A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H indicate regions used to calculate diurnal cycles of SDHR and MCSs(TBB ≤ –52℃); see text for details). |

Although the Central Meteorological Office ofChina has defined SDHR as hourly rainfall≥ 20 mm, there is currently no strictly uniform definition ofSDHR in China. Flash floods in the United Statesare generally associated with hourly rainfall≥ 20 mm(Davis, 2001). Zhang and Zhai(2011)found thatthe annual occurrence frequency of days with rainfallintensity≥ 50 mm day−1 is approximately equal tothe annual occurrence frequency of hourly rain ratesin excess of 20 mm h−1. This result suggests that20 mm h−1 is a suitable threshold for short-duration“rainstorms” in eastern China. Scale analysis and the relationship between precipitation and vertical velocity suggest that precipitation rates≥ 10 mm h−1are generally associated with meso- and micro-scaleweather systems, while precipitation rates≥ 50 mmh−1 are mainly produced by microscale weather systems.

The sensitivity of the climatology of SDHR to thethreshold intensity is explored by calculating climatological distributions of hourly rainfall≥ 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mm over China. The hourly rainfall ratesused in this paper are derived on an hourly basis. Asa result, an hour of heavy rainfall that occurs acrosstwo 1-h intervals may be classified into two hourly datapoints with rain rates less than the intensity during theheavy rainfall period. Accordingly, the frequencies ofSDHR reported in this paper are likely underestimatesof the actual frequencies.

The following methodology is adopted in thisstudy. Given a specified analysis period and threshold rainfall intensity(for example, 20 mm), the SDHRfrequency at any station in China is calculated by dividing the number of hourly data points exceeding thespecified threshold intensity by the total number ofhourly data points. This frequency is referred to asthe frequency of SDHR occurrence. The spatial distribution and average diurnal variations of maximumhourly rainfall are also presented.

Geostationary satellite observations of infraredTBB are used to analyze the diurnal variations ofMCSs. These diurnal variations are then comparedwith the diurnal variations of SDHR. The TBB datasetis effectively the same as that used by Zheng et al.(2008), but with temporal coverage from June to August 1996–2007(excluding 2004). The spatial resolution of the data is 0.1°×0.1°(latitude by longitude).The methodology mirrors that applied by Zheng et al.(2008), in which the frequency of MCSs is calculatedfor each grid cell as the frequency of TBB ≤ –52℃.The spatial resolution of the TBB data is significantlyfiner than the spatial resolution of the hourly rainfalldata(approximately 100 km).3. Spatial distribution

Figure 2 shows the spatial distributions of SDHR events exceeding 20 and 50 mm h−1 and the spatial distribution of maximum hourly rainfall over China. The spatial distributions of SDHR events exceeding 10, 30, and 40 mm h−1(figure omitted)are similar to that of SDHR events exceeding 20 mm h−1(Fig. 2a). These distributions are also consistent with that reported by Zhang and Zhai(2011), who based their analysis on hourly rainfall observations over eastern China during the warm seasons of 1961–2000. The spatial distribution of SDHR events exceeding 50 mm h−1(Fig. 2b)is substantially different from the distributions of SDHR events exceeding the lower intensity thresholds. This difference may be because extreme rainfall events with intensity exceeding 50 mm h−1 are mainly associated with rare microscale weather systems that have a very low occurrence frequency. This paper focuses on the spatial and temporal distributions of SDHR events exceeding 20 mm h−1 for consistency with the definition of SDHR given by the Central Meteorological Observatory of China, the threshold for extreme hourly rainfall over eastern China identified by Zhang and Zhai(2011), and the threshold of hourly rainfall intensity typically associated with flash floods in the U.S.(Davis, 2001). This simplification is also supported by the consistency among the spatial distributions of SDHR event frequencies in China when SDHR is defined using intensity thresholds between 10 and 40 mm h−1.

|

| Fig. 2.Frequencies(%)of SDHR events exceeding(a)20 and (b)50 mm h−1 during the warm season(April–September), and (c)maximum hourly rainfall(mm)observed during the warm season. |

The spatial distribution of SDHR events exceeding 20 mm h−1 is very similar to the distribution ofthe annual mean number of heavy-rain days in China(Zhang and Lin, 1985; China Meteorological Administration, 2007). SDHR events generally occur morefrequently in southern China than in northern China.They also occur more frequently in eastern China thanin western China, and are more common over plains and valleys than over the adjacent plateaus and mountains. Seasonal rainfall over most of China is closelyassociated with the movement of the East Asian summer monsoon(Tao, 1980). SDHR events therefore occur more frequently in regions strongly affected by thesummer monsoon than in regions where the influenceof the summer monsoon is small.The distribution of SDHR frequency over Chinais also quite similar to the distribution of lightningdensity according to satellite observations(Ma et al., 2005; China Meteorological Administration, 2007).This result indicates that the climatologies of heavyprecipitation and lightning activity are closely related.The distributions of SDHR frequency, thunderstormactivity(China Meteorological Administration, 2007), and MCS occurrence(Zheng et al., 2008)are generallyconsistent, although there are some important differences. Thunderstorms and MCSs generally occur morefrequently over mountain and plateau regions, whileSDHR events occur more frequently over plains and valleys. SDHR activity is largest in South China, witha maximum frequency of 0.62%(Fig. 2a). Other regions with high SDHR activity include the southwestern Sichuan basin, the southeastern part of SouthwestChina, the eastern Huang-Huai River basin, the JiangHuai River basin, Jiangxi Province, the coastal areasof Zhejiang Province, and most of Fujian Province.The spatial distribution of the average annual number of days with SDHR(days on which the rain rateexceeds 20 mm h−1 at least once; figure omitted)isconsistent with the spatial distribution of SDHR frequency. The maximum annual mean number of SDHRdays in South China is 30 days. The spatial distribution of SDHR and the locations of centers of high SDHR activity are closely related to the characteristics of the terrain. This result is consistent with theconclusions of several previous studies that the distribution of heavy rainfall in China is strongly affectedby the topography(Tao, 1980; Huang et al., 1986).

The frequency of extreme SDHR(hourly rainfall≥ 50 mm)is very low throughout China(Fig. 2b).The maximum frequency is only 0.08%, which corresponds to only 8 h of extreme SDHR in every 10000 h(approximately 417 days). The maximum number ofhours in April–September with extreme SDHR ≥ 50mm h−1 during 1991–2009 is 64 h at Yangjiang station.Extreme SDHR events occur most frequently over thecoastal areas of Fujian and Zhejiang, central Henan, southern Hebei, and southwestern Liaoning provinces.The spatial distribution of extreme SDHR ≥ 50 mmh−1 is very similar to the spatial distribution of heavyrain ≥ 100 mm day−1 reported by Zhang and Lin(1985). Extreme SDHR activity(rain rates ≥ 50 mmh−1)is much more scattered and heterogeneous thanSDHR activity(rain rates ≥ 20 mm h−1). This may bebecause extreme SDHR is mainly produced by extrememicroscale weather systems, or it may be attributableto special terrain characteristics. Extreme SDHR ismore common along the coastal areas of southeastern China than in inl and areas because the coastal areas are more commonly affected by extreme weathersystems associated with typhoons or tropical easterlywaves.

The spatial distribution of maximum hourly rainfall(Fig. 2c)reveals another aspect of severe convective weather systems. The distribution of maximum hourly rainfall is different from the distributionof SDHR frequency over China. The maximum hourlyrainfall observed at most stations outside the typicaldomain of the summer monsoon was less than 50 mm, ikely due to lower concentrations of water vapor inthe atmosphere. In eastern China(where the annualcycle of rainfall is strongly affected by the summermonsoon), most of the stations that observe a maximum hourly rainfall larger than 120 mm are located insouthern China; however, the maximum hourly rainfall exceeds 80 mm at several stations in northernChina, and even exceeds 120 mm at a few stations.This result suggests that the intensities of the mostsevere convective rainfall events are similar throughout eastern China.

The hourly rainfall data used for this analysisonly include observations from most of the first- and second-class national meteorological stations in China.The data at each station only represent the averagehourly rainfall in a very specific area. Furthermore, the data record only spans 19 yr. The maximumhourly rainfall observed at each station during thistime period may not be truly representative of extreme precipitation. For example, there are reportsof hourly rainfall of 185.6 mm at Gangyaoling, Liaoning Province on 11 July 1978(Hydrological Bureau of the Yangtze River Water Resources Commission of MWR of China, 1995; Hydrology Bureau of MWR of China, 2006), 198.3 mm at Linzhuang, Henan Provinceon 5 August 1975(Ding and Zhang, 2009), 220.2 mmat Maodong(Yangjiang), Guangdong Province on 12May 1979, and 245.1 mm at Dongxikou(Chenghai), Guangdong Province on 11 June 1979(Huang et al., 1986).4. Seasonal and pentad variations4.1 Seasonal variations

Heavy rain and convective weather in China occur most frequently during summer. Summer(June–August)is also the most active season for SDHR(Fig. 3), which is consistent with common knowledge ofprecipitation patterns in China. The second highest SDHR frequency during the warm season is inlate spring(April–May), while the frequency of SDHRdrops substantially in early autumn(September). Thespatial distribution of SDHR events during summer(Fig. 3b)is very similar to the distribution during theentire warm season(Fig. 2a). This similarity suggeststhat the distribution of SDHR during the warm season is primarily determined by the distribution duringsummer, and the summer monsoon plays a key role indetermining the distribution of SDHR.

|

| Fig. 3. Frequencies(%)of SDHR events with rain rates greater than 20 mm h−1 during(a)late spring(April–May), (b)summer(June–August), and (c)early autumn(September). |

Springtime SDHR events occur mainly in SouthChina, particularly in the regions south of the YangtzeRiver and southern Yunnan(Fig. 3a). The largest frequencies are located in the eastern part of the GuangxiRegion and western Guangdong Province. These highfrequencies are closely associated with precipitationduring the first rainy season in South China. Althoughthe warmest air masses during spring are located oversouthern China, SDHR events occasionally occur inthe southern part of North China and western Sh and ong Province. For example, an SDHR event with arain rate greater than 20 mm h−1 occurred at Jiyang, Sh and ong Province on 17 April 2003. Another SDHRevent with a rain rate greater than 20 mm h−1 occurred over a wide area comprising southern Hebei, Sh and ong, and northern and western Henan provincesduring 9–10 May 2009. An event of similar magnitudeoccurred over a broad area comprising central and southern Hebei, northwestern Sh and ong, and central and southern Liaoning provinces during 24–25 April2012.

As mentioned above, the spatial distribution ofSDHR during summer largely determines the me and istribution for the entire warm season; however, thecenters of high SDHR frequency are more prominentduring summer than when the warm season is considered as a whole(Fig. 3b). SDHR events also occur relatively frequently in the boundary regions ofthe summer monsoon(e.g., southern Gansu, Shaanxi, Shanxi provinces, and central and eastern Inner Mongolia)during this season. An SDHR event with a peakhourly rainfall of 77.3 mm resulted in a large and damaging flow of debris at Zhouqu, Gansu Province on 8August 2010.

The frequency of SDHR events weakens considerably in early autumn(September), toward the end ofthe warm season(Fig. 3c). The frequency of earlyautumn SDHR events is highest in the coastal areas ofsoutheastern China such as Fujian, Zhejiang, Hainan, and so on. SDHR events also occur relatively frequently in southern Yunnan Province and in theSichuan basin. SDHR events are not limited to theseregions, however; for example, an SDHR event witha peak hourly rainfall of more than 60 mm occurredover a broad area south of the Yangtze River on 9–10November 2009.

The distribution of rainfall in China during summer is determined primarily by the advance and retreat of the summer monsoon(Tao, 1980). SDHRevents in spring are often associated with the summer monsoon or cold air incursions. Most precipitation in South China during April is related to frontalactivity. After the summer monsoon becomes established in mid-May, convective activity and the occurrence frequency of heavy precipitation increase significantly in South China(Huang et al., 1986; Zhou et al., 2003). In summer(especially in July and August), there may be two or three active b and s of SDHR overChina on one day. One of these b and s may be relatedto cold air incursions at middle and high latitudes, while the other(s)may be related to the activity ofthe subtropical high and summer monsoon. SDHRevents are much more common under the latter situation than under the former. The western Pacificsubtropical high at 850 hPa weakens considerably inSeptember, so weather conditions in eastern China aredominated by the deformation of the anticyclonic circulation in the Arctic high pressure zone south of 40°N(Central Meteorological Bureau, 1975). The frequencyof SDHR events therefore drops rapidly at this timeof year over most of China; however, the ITCZ(Intertropical Convergence Zone)also reaches its northernmost location during September. This seasonal shift of the ITCZ increases the influence of tropicalweather systems(such as typhoons and tropical easterly waves) and related SDHR events along the coastline of southern and southeastern China.4.2 Monthly and pentad variations

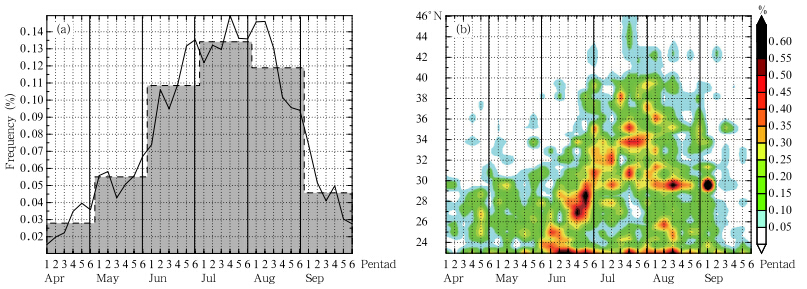

Figure 4a shows the mean variations of SDHRfrequency during the warm season at monthly and pentad time resolutions averaged over all of China.The monthly variation of SDHR frequency during thewarm season has a single peak. The frequency increases gradually from April to July, peaks in July, and then begins to decrease in August. This decreasebecomes even more pronounced in September, so theoverall evolution is characterized by a low increase followed by a rapid decrease. This evolution is reminiscent of the seasonal evolution of the East Asian summer monsoon, which becomes established around midMay, peaks near the end of July, and rapidly retreatssouthward in September(Chen et al., 1991). SDHRevents during the warm season in China are most common in July and least common in April.

|

| Fig. 4.(a)Monthly(dashed line) and pentad(solid line)variations in the frequency(%)of SDHR events with rain rates greater than 20 mm h−1.(b)Pentad-latitude cross-section of variations in SDHR frequency(%)along 116°E. |

SDHR events occur most frequently on the fourthpentad of July, followed by the first and second pentads of August. Among warm season pentads, SDHRevents occur least frequently on the first pentad ofApril. The evolution of the SDHR frequency appearsto develop in intermittent phases, with multiple maxima(active phases). This evolution is closely related tothe seasonal development of precipitation associatedwith the East Asian summer monsoon, which tendsto advance and withdraw in stages(Ding and Zhang, 2009). The initial increase of SDHR activity that occurs in April and May corresponds to the beginningof the heavy-rain season in South China. A secondincrease in the SDHR frequency follows in mid-May, with a peak in early June. This change is associatedwith the onset of the South China Sea Summer Monsoon(SCSSM) and the heaviest rainfall of the firstrainy season in South China(Huang et al., 1986). Thepeak of SDHR activity in the sixth pentad of June isassociated with the late June–early July Meiyu periodover the Yangtze-Huai River basin. The rainy season in North China stretches from late July to earlyAugust. The peaks in SDHR frequency in the fourthpentad of July and the first and second pentads ofAugust are associated with the second Meiyu precipitation and strong convective activity along the rimof the subtropical high over the Yangtze-Huai Riverbasin. The last two pentads in August correspondto the second rainy season in South China, which isstrongly influenced by tropical weather systems suchas typhoons and tropical easterly waves. The minorpeak in SDHR activity in the fourth pentad of September is associated with the northward displacement ofthe ITCZ and associated rainfall in the coastal areasof southern and southeastern China.

Figure 4b shows the pentad-latitude cross-sectionof SDHR frequency along 116°E. A similar analysishas been done to examine variations in SDHR activityalong 105°E(figure omitted). The locations of thesetwo meridians are shown in Fig. 1. The frequenciesof SDHR events along both meridians show similarevidence of intermittent development. The number ofpeaks in SDHR activity during the warm season varieswith latitude. More SDHR events occur at lower latitudes than at higher latitudes. The evolution of SDHRactivity during the warm season is characterized bya longer active period containing multiple peaks atlow latitudes but a shorter active period with a singlepeak at high latitudes. The SDHR frequency alongmeridian 116°E(Fig. 4b)increases slowly and thendecreases rapidly as the warm season progresses. Thisslow northward advance and rapid southward retreatof SDHR activity are closely associated with the evolution of the East Asian summer monsoon(Chen et al., 1991).

SDHR events along 116°E are mainly restricted toSouth China and the area south of the Yangtze Riverduring late spring(April–May), but SDHR events alsooccur infrequently in the Yangtze-Huai River basin and the southern part of North China. SDHR activity is still mainly located in South China and thearea south of the Yangtze River through mid June, although it gradually advances northward. In late June, SDHR activity rapidly advances northward into thecentral part of North China(near 40°N). The northernmost SDHR events typically occur in mid July, followed by the southward retreat of SDHR activity intothe southern part of North China by late August. Thisactivity then quickly retreats further southward intoSouth China by late September. This evolution ofSDHR activity in China is entirely consistent with thenorthward advance and southward retreat of the EastAsian summer monsoon, which is related to northward and southward displacements of the western North Pacific subtropical high(Ding and Zhang, 2009).

Pentad variations in SDHR activity over the coastal area of South China(near 23°N)are small, especially during summer(June–August)(Fig. 4b). This result is consistent with pentad variations in convective activity implied by geostationary satellite observations of infrared TBB in summer(Zheng and Chen, 2011), but differs from pentad variations in total rainfall averaged over all of South China(Ding and Zhang, 2009). The frequencies of SDHR events over 24°–25°N of South China, the area south of the Yangtze River, the Yangtze-Huai River basin, and southern North China along meridian 116°E peak at different times during the warm season. SDHR activity in these areas is influenced by different types of weather systems at different stages of the summer monsoon. The frequency of SDHR events in northern North China(north of 40°N)generally peaks only once during the warm season. This single peak is related to the maximum northward advance of the East Asian summer monsoon, which occurs in July. The main periods of SDHR activity differ substantially over different regions, but the common feature is that these active periods are associated with the northward advance or peak activity of the East Asian summer monsoon. The secondary peaks typically occur after the summer monsoon has advanced further northward or when the summer monsoon retreats back toward the south.5. Diurnal variations

Diurnal variations in precipitation and convective activity(such as thunderstorms, hail, and MCSs)are evident. A number of previous studies have analyzed these diurnal variations(Zhang and Lin, 1985;Yu et al., 2007a; China Meteorological Administration, 2007; Zheng et al., 2007, 2008; Li et al., 2008a).Zhou et al.(2008)analyzed the characteristics of precipitation as observed by both raingauge and satellite. Zhang and Zhai(2011)reported diurnal variations of more than 20 mm h−1 in hourly precipitationover eastern China during the warm season(May–September). No previous studies have characterizedthe relationships between diurnal variations in SDHR and convection. This section presents the characteristics and propagation patterns of diurnal variations inSDHR over different parts of China, and explores theirrelationships with diurnal variations in MCSs.

MCSs are defined as regions with TBB ≤ –52℃at a horizontal resolution of 0.1°×0.1°. This definitioncan identify both meso-α-scale convective systems(MαCS) and meso-β-scale convective systems(MβCS)with horizontal scales exceeding 20 km(Zheng et al., 2007, 2008). These systems comprise a variety of atmospheric convective systems, including weak convective systems(such as isolated thunderstorms and lightning storms) and severe convective systems(such ashailstorms and SDHR with damaging winds). Thespatial resolution of the hourly rainfall data is muchcoarser than the spatial resolution of the geostationarysatellite TBB data.5.1 Mean diurnal variations over China

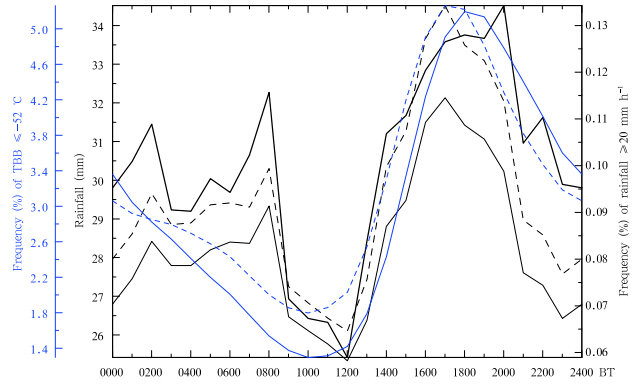

Figure 5 shows the mean diurnal variations ofSDHR frequency and maximum hourly rainfall averaged over all stations in China(excluding Taiwan)during the warm season(April–September). Mean diurnal variations over the active precipitation region(Anhui, Fujian, Jiangsu, Sh and ong, Shanghai, Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Heilongjiang, Jilin, Liaoning, Beijing, Hebei, Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Tianjin, Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan, and Chongqing)are also shown, asare the mean diurnal variations of MCSs during summer(June–August).

|

| Fig. 5.Diurnal variations in mean frequency and maximum hourly rainfall for SDHR events with rainfall ≥ 20 mm h−1 and brightness temperature(TBB)less than –52℃. Diurnal variations in the mean frequencies are shown for SDHR averaged over all of China(thin black solid line), SDHR averaged over the active precipitation region(thick black dashed line), TBB ≤ –52℃ averaged over all of China(blue solid line), and TBB ≤ –52℃ averaged over the active precipitation region(blue dashed line). The thick black solid line shows the maximum hourly rainfall averaged over all of China. The blue y-axis indicates the frequency(%)of TBB ≤ –52℃, the black y-axis on the left indicates hourly rainfall(mm), and the black y-axis on the right indicates SDHR frequency(%). |

The mean SDHR frequency and maximum hourlyrainfall are calculated based on data at stations with atleast 15 years of observations. SDHR frequencies and maximum hourly rainfall are identified for every hourof the day at each station. The results are then averaged across stations to illustrate mean diurnal variations of SDHR frequencies and maximum hourly rainfall in China.

The most prominent feature of the diurnal variations in SDHR is the presence of three peaks. The main peak occurs in the afternoon(between 1600 and 1700 BT), with secondary peaks just after midnight(0100–0200 BT) and in the early morning(0700–0800 BT). SDHR is least common during the morning. The mean diurnal variations in maximum hourly rainfall are largely consistent with those in mean SDHR frequency. The diurnal variations of both variables are fully consistent from midnight to early morning; however, variations in mean maximum hourly rainfall are slightly behind those in mean SDHR frequency from afternoon to midnight. The temporal rates of change in the two diurnal cycles indicate that SDHR frequency and maximum hourly rainfall change rapidly from afternoon to midnight. Both variables change less rapidly after midnight. Mean diurnal variations in SDHR frequency and maximum hourly rainfall over the active precipitation region are consistent with those over China as a whole; however, mean SDHR frequency over the active precipitation region is higher than mean SDHR frequency over China as a whole. The lower frequency of SDHR over the inactive precipitation region depresses mean SDHR frequencies averaged over all of China.

Mean diurnal variations in MCSs have only a single peak, regardless of whether the average is calculated over China as a whole or over the active precipitation region. There are some differences between variations over China as a whole and variations over theactive precipitation region. First, diurnal variations inMCSs over China as a whole lag about 1 h behind diurnal variations in MCSs over the active precipitationregion. This difference is caused by diurnal variationsin MCSs over the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, which isamong the most active regions for MCSs in China.MCS activity over the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau lagsthat over the active precipitation region due to differences in longitude. Second, mean MCS frequenciesbetween midnight and early morning are significantlyhigher over the active precipitation region than overChina as a whole. Several areas within the activeprecipitation region(e.g., Guangdong and Guangxi, the Sichuan basin, the northeastern Yunnan-GuizhouPlateau, and the Yangtze-Huai River basin)have significant nocturnal MCS activity(Zheng et al., 2008, 2010; Zheng and Chen, 2011).

Mean diurnal variations in MCSs and SDHR overChina as a whole and over the active precipitation region have several common features, as well as significant differences. Common features include: 1)themost active period occurs in the afternoon(becauseconvection is most active in the afternoon); and 2)allfour diurnal variations change rapidly from afternoonto midnight, and then change less rapidly( and relatively smoothly)after midnight. Differences include: 1)the frequencies of SDHR and MCSs are significantlydifferent(i.e., MCSs occur much more frequently thanSDHR events, with the peak frequency of MCSs approximately 40 times that of SDHR); 2)the patternof diurnal variations in MCSs is relatively continuous and smooth when compared with that of variations inSDHR; and 3)SDHR frequency has three peaks(twoof which occur at night), while the frequency of MCSshas a single peak and no nocturnal maximum.

Although convective activity peaks in the afternoon in China during the warm season, only a verysmall fraction of this activity reaches SDHR intensity.Moreover, the ratio of convective events that reachSDHR intensity is substantially higher after midnightthan in the afternoon, even though overall convectiveactivity is weaker. This result indicates that nocturnalconvective activity in China during the warm seasonoften produces relatively large amounts of precipitation. The occurrence frequency of other types of severe convective activity is substantially reduced during nighttime, although previous work has shown thathailstorms may occur at night in some parts of China(Zhang et al., 2008).

Both the SDHR frequency and the maximumhourly rainfall associated with thermal convection inthe afternoon are higher than those associated withconvection that occurs after midnight. The main reason for the increase in relative SDHR activity aftermidnight is the close relationship between SDHR and MαCSs, which can last for more than 12 h. This resultis consistent with the conclusions of Yu et al.(2007b), who showed that precipitation often peaks after midnight during long-duration rainfall events. NocturnalSDHR events are associated with different periods ofactive convection over different regions(Zheng et al., 2008, 2010; Zheng and Chen, 2011). The following section provides further analysis of regional differences inthe diurnal variations of SDHR.

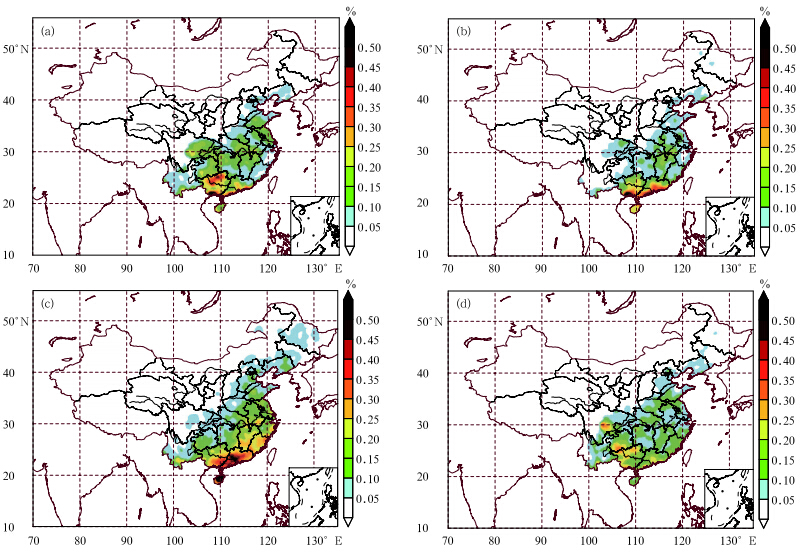

Figure 6 shows distributions of SDHR frequencyat different times of a day. As in Fig. 5, SDHR eventsoccur most often in the afternoon(1400–2000 BT) and least often in the morning(0800–1400 BT), but periods of high SDHR activity in China differ by region.Moreover, diurnal variations in SDHR activity appearto propagate in characteristic ways.

|

| Fig. 6.Diurnal variations of the frequency(%)of SDHR with hourly rainfall ≥ 20 mm h−1 for(a)0200–0800 BT, (b)0800–1400 BT, (c)1400–2000 BT, and (d)2000–0200 BT. |

SDHR frequencies are high from afternoon toevening(1400–2000 BT; Fig. 6c)over wide spreadareas. These high frequencies are associated not onlywith large-scale weather systems that provide favorable environments for SDHR(such as low pressuretroughs and the Meiyu front), but also with topography and the distribution of thermal convection inthe afternoon(Zheng et al., 2007, 2008). SDHR frequencies are substantially weaker between the evening and early morning(2000–0200 BT; Fig. 6d)over mostof China, but nocturnal SDHR events are relativelycommon over the southwestern Sichuan basin, southern Guizhou, northwestern Guangxi, and the coastalareas of Guangdong and Guangxi. Areas of highSDHR frequency continue to shrink from midnightto early morning(0200–0800 BT; Fig. 6a). SDHRactivity weakens substantially over the southwesternSichuan basin and southern Guizhou, but SDHR activity over Guangxi and the coastal areas of Guangdong strengthens. SDHR events are less common overall of China during the morning hours(0800–1400 BT;Fig. 6b), but SDHR events are still relatively frequentover the coastal areas of southeastern China, the eastern Sichuan basin, and the lower and middle reachesof Yangtze River. This relatively high SDHR activity may indicate that these areas are strongly influenced by local atmospheric circulations caused by thel and -sea transition(for coastal areas), topography, orlarge-scale weather systems(such as the Meiyu frontor easterly waves). SDHR frequencies over the coastalareas of South China are higher during the 0800–1400BT period than between midnight and early morning.This diurnal cycle in SDHR activity may be associatedwith the strengthening of the l and -sea breeze duringthe morning hours(Huang et al., 1986).

Zhang and Zhai(2011)pointed out that, over theSichuan basin and Guizhou, many of the events withhourly precipitation exceeding 20 mm h−1 happen atnight. Nighttime SDHR activity is centered primarilyin three regions of China.

The first region includes Guizhou, Guangxi, and Guangdong. It is interesting to note the propagation of SDHR across this region. SDHR activity overGuangxi and Guangdong develops and strengthens between 1400 and 2000 BT. A sharp weakening followsafter 2000 BT, although SDHR activity near the coastremains strong. This coastal center of SDHR activity then begins to strengthen and propagate inl and after 0200 BT, followed by continued strengthening and propagation into mountainous areas during 0800–1400 BT. By contrast, SDHR activity over southernGuizhou and northern Guangxi develops and strengthens during 2000–0200 BT. This active property thenpropagates southeastward after 0200 BT, as SDHR activity over northwestern Guangxi increases. SDHRactivity then propagates into the central region ofGuangxi( and even to Guangdong)during 0800–1400BT. These characteristic propagation patterns are consistent with the movement of MCSs as revealed bygeostationary satellite TBB data(Zheng et al., 2008, 2010; Zheng and Chen, 2011). The patterns are closelyrelated to topography, which may cause local valleywind or l and -sea breeze circulations. The mechanismby which local circulations and the associated synopticsystems lead to these characteristic propagation patterns requires further study.

The second region is the Sichuan basin. SDHRevents in the southwestern Sichuan basin are most frequent during 2000–0200 BT.This center of SDHR activity then weakens and propagates toward the northeast during 0200–0800 BT, before largely disappearingaround 1400–2000 BT. SDHR activity in this region isweakest in the afternoon and strongest from eveningto midnight. Nocturnal rain events are accordinglyrelatively common. These features are consistent withthe diurnal variation and propagation of MCSs in thisregion(Zheng et al., 2008, 2010), which may also haveclose relationships with local valley circulations causedby topography.

The third region covers the middle and lowerreaches of the Yangtze River and the Yangtze-HuaiRiver basins. This is the main Meiyu precipitationregion(Tao, 1980), and a region of frequent MCSactivity(Zheng et al., 2008). SDHR in this regionis remarkably strong during the afternoon(1400–2000 BT). This center of SDHR activity is weak during the evening and late night(2000–0200 BT), butstrengthens again by the early morning(0200–0800BT).5.2 Diurnal variations over different regions

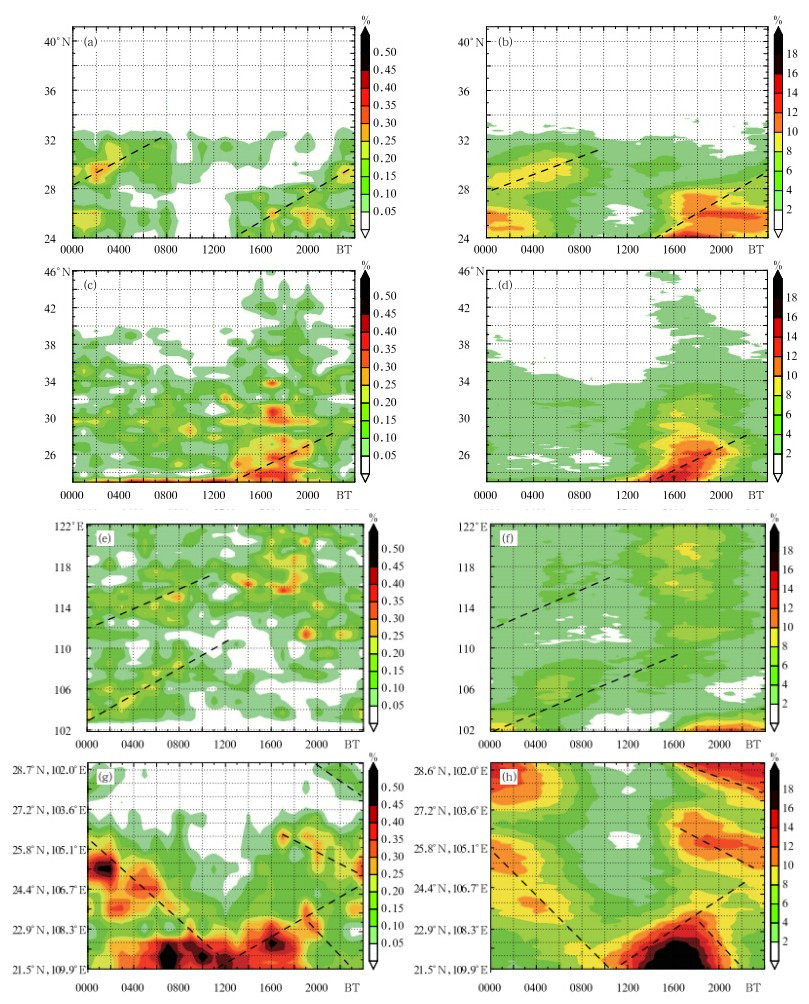

Differences in diurnal variations of SDHR and MCSs over different regions are examined using timelatitude cross-sections along the 105° and 116°Emeridians, a time-longitude cross-section along the31°N parallel, and a cross-section along a straight linefrom southwestern Sichuan to southeastern Guangxi(Fig. 7). The positions of all cross-sections are indicated by white lines in Fig. 1. Diurnal variations inSDHR and MCSs are very similar, but diurnal variations in MCSs are smoother and more continuous, and the MCSs propagate more clearly. These differences result from differences in the observations. Observations of TBB(which are used to identify MCS anvil clouds)are instantaneous rather than hourly, and TBB is a more continuous quantity than precipitation.

|

| Fig. 7. Temporal cross-sections of diurnal variations in the frequencies(%)of SDHR(hourly rainfall ≥ 20 mm; left column) and MCSs(TBB ≤ –52℃; right column)along(a, b)the 105°E meridian, (c, d)the 116°E meridian, (e, f)the 31°N parallel, and (g, h)the straight line connecting points(28.9°N, 101.7°E) and (21.5°N, 109.9°E). |

Diurnal variations in SDHR and MCSs along the105°E meridian(Figs. 7a and 7b)indicate two different regimes of nocturnal convection. SDHR and MCSactivities over the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau(24°–28°N)are strong from afternoon until midnight. Thiscenter of convective activity remains strong but propagates from south to north after midnight. Convectionin this region is active in the afternoon and at night, with minimum activity in the morning. This patternof diurnal variations is consistent with diurnal variations in lightning activity(Wang et al., 2009). SDHR and MCS activities over the Sichuan basin(28°–32°N)strengthen after 2200 BT, and then weaken substantially after sunrise. This center of convective activityalso propagates from south to north, but it is weakest in the afternoon. Convection in the region is activefrom midnight to morning, with a minimum in the afternoon.

Diurnal variations in SDHR and MCSs along the116°E meridian(Figs. 7c and 7d)show evidenceof diurnal cycles with a single peak, multiple peaks, and longer duration. Convection along this transectis most active in the afternoon. North-south propagation of SDHR and MCSs is largely absent, particularly when compared with their movement along105°E(Figs. 7a and 7b). SDHR and MCSs in thecoastal area near 23°N, 116°E have longer durations(particularly SDHR). The area from 23.5° to 28°N covers Guangdong and southern Jiangxi, where diurnalvariations of MCSs typically have a single peak. Diurnal variations of SDHR show two types: single-peak and multiple-peak. The differences between them maybe related to the distribution of rainfall forced bymesoscale topographic variations. SDHR and MCSswithin 23°–26°N along this meridian appear to propagate from south to north. This result is consistent withthat obtained by Zheng and Chen(2011). The diurnal variations of SDHR over the area from 28° to 32°N(Jiangxi and southern Anhui)typically have multiplepeaks, with substantial nocturnal activity. Diurnalvariations in MCS activity in general do not have multiple peaks. Diurnal variations in both SDHR and MCSs over the area from 34° to 46°N(Henan, Sh and ong, and North China)commonly have double peaks, with a primary peak in the afternoon and a secondarypeak near midnight.

Figures 7e and 7f show diurnal variations inSDHR and MCSs along the 31°N parallel. Diurnal variations along this transect indicate multiplepeaks in convective activity. SDHR and MCSs over102°–110°E(Sichuan) and 111°–118°E(Hubei and Anhui)propagate towards the east, and are more active during nighttime and morning. SDHR and MCSsalong 31°N in the Sichuan basin are largely nocturnal, particularly over 103°–108°E. These events typically propagate eastward after midnight. By contrast, MCSs over the plateau(to the west of the Sichuanbasin near 102°E)are more active in the afternoon.SDHR rarely occurs over this plateau at this time ofthe day. Diurnal variations in SDHR and MCSs over112°–118°E indicate multiple peaks in convective activity, with a primary maximum from afternoon tomidnight and a secondary maximum after midnight.SDHR and MCSs in this region propagate eastwardafter midnight. This eastward propagation is morepronounced for SDHR.

Previous research on the climatological distribution of deep convection in subtropical China has shownthat MCSs over the plateau west of Sichuan propagatesoutheastward toward the northern Yunnan-GuizhouPlateau after sunset(1900 BT), while MCSs overthe northeastern Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau propagatesoutheastward toward northern Guangxi after sunset(1900 BT)(Zheng et al., 2010). We therefore alsoanalyze diurnal variability and propagation of SDHR and MCSs along the straight line [(28.9°N, 101.7°E)–(21.5°N, 109.9°E)], which extends from the southeastern part of the plateau west of Sichuan to Guangxithrough the northeastern part of the Yunnan-GuizhouPlateau(southwestern Guizhou). The diurnal variations along this line(Figs. 7g and 7h)show differencesin the characteristics of SDHR and MCSs over different underlying surfaces.

Several characteristic types of diurnal variations in SDHR and MCSs are identified along the aforementioned line(Figs. 7g and 7h).(1)The first characteristic type is the single-peak diurnal variation in both SDHR and MCSs located over the southeastern part of the western Sichuan plateau [(28.6°N, 102°E)–(27.2°N, 103.6°E)]. MCS activity over this region is strongest from the afternoon until after midnight and has a relatively long duration. SDHR events occur mainly at night, and with lower frequencies.(2)The second characteristic type is the thermal convection over western Guizhou [(27.2°N, 103.6°E)–(26.3°N, 104.6°E)]. MCS activity over this region occurs mainly in the afternoon, with a relatively short duration. Nighttime MCS activity is lower over this region than over the western Sichuan plateau. SDHR events are very infrequent over this region.(3)The third characteristic type is the single-peak diurnal variation in both SDHR and MCSs over southwestern Guizhou [(26.3°N, 104.6°E)–(24.8°N, 106.2°E)]. Both SDHR and MCSs are active over this region, with longer durations and strong activity from afternoon until just before sunrise. This pattern of diurnal variations is consistent with the pattern of diurnal variations in SDHR and MCSs over 24°–28°N along the 105°E meridian. It also corresponds to the diurnal variation of lightning in this region(Wang et al., 2009).(4)The fourth characteristic type is observed over the western Guangxi basin [(24.8°N, 106.2°E)–(23.9°N, 107.3°E)]. SDHR and MCSs in this region occur mainly at night(2000–0800 BT). This diurnal pattern is very similar to that of SDHR and MCSs over the Sichuan basin(28°–32°N)along the 105°E meridian.(5)The fifth characteristic type is observed over the coastal area of southern Guangxi, where SDHR events occur more often and have longer durations, mainly between midnight and sunset(0200–1800 BT). The occurrence frequency of both SDHR and MCSs decreases significantly between sunset and midnight.

The typical propagation of SDHR and MCSsalong this transect is as follows. First, SDHR and MCSs over the southeastern part of western Sichuanplateau [(28.6°N, 102.0°E)–(27.2°N, 103.6°E)] propagate toward the southeast. Second, SDHR and MCSsover western Guizhou(27.2°N, 103.6°E), which aremost active in the afternoon, propagate southeastward. These systems arrive in the border region between Guizhou and Guangxi(24.8°N, 106.2°E)around0000 BT. They then continue to propagate southeastward after midnight, reaching the northern part ofsouthern Guangxi(22.9°N, 108.3°E)at about 0400BT and the coastal area of Guangdong at about 0600BT. Third, although SDHR activity over the coastalarea of Guangxi(21.5°N, 109.9°E)is relatively strongfrom 0200 to 1800 BT, MCS activity strengthens considerably after 0400 BT. This center of strong MCSactivity propagates northwestward after 1200 BT, butsplits and propagates in two separate directions after1800–2000 BT. Some of the MCSs continue to propagate northwestward into the boundary region betweenGuizhou and Guangxi(arriving around 0000 BT). Theremainder retreat southeastward and return to thecoastal area of Guangxi.

Zheng et al.(2008, 2010) and Zheng and Chen(2011)showed that diurnal variations in convectionover different regions of China are closely related tolocal circulations caused by thermal differences amongwater, l and , and rough terrain(such as valley windsor l and -sea breezes). The results in this paper alsoshow close relationships between local thermodynamiccirculations and SDHR. Huang et al.(1986)studiedthe relationship between the diurnal variations in precipitation and thermodynamic circulations over SouthChina. They found that circulations coupled to valleywinds and l and -sea breezes amplify the diurnal variations and propagation tendencies of precipitation inthis region. Zheng and Chen(2011)showed that thisrelationship extends to convection as well. However, the diurnal variations and propagation of SDHR and MCSs are affected not only by local thermodynamiccirculations but also by large-scale circulation patterns, the movement of large-scale weather systems, and variations in the steering flow. The influence ofmulti-scale interactions between the local circulation and large-scale or mesoscale weather systems on diurnal variations and propagations of SDHR and MCSsshould therefore be addressed in future work.

Figure 8 shows the diurnal variations of the meanfrequencies of SDHR(hourly rainfall≥ 20 mm) and the MCSs(TBB ≤ –52℃)over active precipitationareas. These results highlight the dependence ofthese diurnal variations on the underlying surface.The areas(indicated by rectangles in Fig. 1)includethe southwestern Sichuan basin(rectangle A; 28°–31°N, 102°–105°E), southwestern Guizhou(rectangleB; 24°–27°N, 104°–107°E), central Guangxi(rectangle C; 22°–25°N, 107°–110°E), the coastal area ofGuangxi(rectangle D; 21°–23°N, 108°–110°E), centralGuangdong(rectangle E; 22°–25°N, 112°–115°E, central and southern Anhui(rectangle F; 30°–33°N, 116°–119°E), southwestern Sh and ong, northern Jiangsu and northern Anhui(rectangle H; 33°–36°N, 116°–119°E), and the eastern Yangtze-Huai River basin(rectangleG; 31°–34°N, 117°–120°E). Note that two vertical axesare used in both panels of Fig. 8 to better highlightthe diurnal variations of SDHR and MCSs in regionswith lower frequencies.

|

| Fig. 8. Diurnal variations in frequency(%)of(a)SDHR(hourly rainfall ≥ 20 mm) and (b)MCSs(TBB ≤ –52℃). The blue curves(for central Guangxi, the coastal area of Guangxi, and central Guangdong)use the blue(right)ordinate axes; the curves for other regions use the black(left)ordinate axes. |

Figure 8a shows that SDHR frequencies are high-est in the afternoon(1400–2000 BT)over central Guangdong, central and southern Anhui, southwestern Sh and ong, northern Jiangsu and northern Anhui, and the eastern Yangtze-Huai River basin. This pattern of diurnal variability is reflected in the mean diurnal variability of SDHR frequency over China as a whole, which also indicates peak activity in the afternoon. By contrast, SDHR frequency over the southwestern Sichuan basin is largest at about 0000 BT. Moreover, although SDHR activity is strong in the afternoon over southwestern Guizhou, it is strongest at about 0200 BT. SDHR activity is also strongest from midnight to early morning(0200–0800 BT)over central and coastal areas of Guangxi. The frequencies of SDHR occurrence over central Guangxi, the coastal area of Guangxi, and central Guangdong are significantly higher than those over other regions even during relatively inactive periods; frequencies over these three regions should be analyzed using the right ordinate axis in Fig. 8a.

Different regions have several different patterns of diurnal variations in SDHR(e.g., single-peak, double-peak, and multiple-peak), as well as significantly different active periods and durations. Regions with single peaks in the diurnal cycle of SDHR frequency include central Guangdong and the southwestern Sichuan basin. The single peak over central Guangdong occurs in the afternoon and has a long duration, while that over the southwestern Sichuan basin occurs at night and has a relatively short duration. Regions with double peaks in the diurnal cycle of SDHR frequency include central Guangxi, the coastal area of Guangxi, and southwestern Guizhou. The main peak in SDHR activity over central Guangxi occurs around 0200–1000 BT, and the secondary peak occurs around 1600–2000 BT. The difference in the amplitudes of these two peaks is insignificant. SDHR diurnal variations over the coastal area of Guangxi are similar to those over central Guangxi, but with substantially higher SDHR frequencies and a more pronounced main peak between midnight and morning. The main peak in SDHR frequency over southwestern Guizhou occurs around 0000–0200 BT, and the secondary peak occurs from afternoon to early evening(1600–2000 BT). SDHR diurnal variations over central and southern Anhui, southwestern Sh and ong, northern Jiangsu and northern Anhui, and the eastern Yangtze-Huai River basin have multiple peaks. This may be associated with the Meiyu precipitation in the Yangtze-Huai River basin. However, SDHR frequencies in these regions are significantly smaller than those over the southwestern Sichuan basin and southwestern Guizhou. The amplitudes of SDHR diurnal variations over southwestern Sh and ong, northern Jiangsu, and northern Anhui are significantly larger than those over central and southern Anhui and the eastern YangtzeHuai River basin. The duration of the active SDHR period over the former two regions is also longer than that of the active period over the latter two regions.

Figure 8b shows only two patterns of diurnal variations in MCS activity: single-peak and double-peak. Multiple peaks are not apparent in the diurnal variations of MCSs in any of the analyzed regions. Diurnal variations in MCSs over the southwestern Sichuan basin and southwestern Guizhou have a single peak during the nighttime, but the magnitudes and durations of this peak are substantially different. Diurnal variations in MCSs over all other analyzed regions have a main peak in the afternoon and evening, although MCSs over the coastal area of Guangxi are active around 0400 BT(earlier than over the other regions). Post-midnight secondary peaks in the diurnal variations of MCSs are apparent but small over central Guangxi, central and southern Anhui, and the eastern Yangtze-Huai River basin.

Comparison of Figs. 8a and 8b indicates that diurnal variations in the frequencies of SDHR and MCSs are largely consistent. The main periods of SDHR and MCS activities are coherent with each other over eight of the nine regions(the southwestern Sichuan basin, southwestern Guizhou, central Guangxi, central Guangdong, central and southern Anhui, southwestern Sh and ong, northern Jiangsu and northern Anhui, and the eastern Yangtze-Huai River basin). Although the main period of MCS activity over the coastal area of Guangxi(afternoon to evening)does not correspond to the main period of SDHR activity(after midnight to early morning), the frequency of MCSs is also relatively high during the main period of SDHR activity.

Beyond this qualitative consistency, there are some differences between the diurnal variations in SDHR and MCS frequencies. As mentioned above, SDHR frequencies are significantly lower than those of MCSs, and the diurnal variations in SDHR are much less continuous and smooth than the diurnal variations in MCSs. With the exception of diurnal variations over the coastal area of Guangxi, the differences between diurnal peaks in SDHR frequency are not so large as those between diurnal peaks in MCS frequency. Except for southwestern Sichuan and southwestern Guizhou, peak MCS activity occurs during the afternoon and evening. The secondary peak in MCS frequency after midnight is insignificant relative to the main peak for most of these regions. This indicates that the proportion of nighttime MCSs that produce SDHR is larger than the proportion of afternoon MCSs that produce SDHR. The main reason for these differences between the diurnal cycles of SDHR and MCSs is that the MCSs(as denoted by TBB ≤ –52℃)encompass a variety of atmospheric convective processes. Most MCSs produce precipitation, but some types of MCSs(such as afternoon MCSs related to thermal convective processes)cannot produce precipitation at rates exceeding 20 mm h−1. This limitation implies differences in the diurnal cycles of the frequencies of SDHR and MCSs.6. Conclusions and discussion

This paper summarizes the spatial distribution, seasonal, monthly, pentad and diurnal variations of SDHR and the relationships between diurnal variations in SDHR and in MCSs over China during the warm season. All results are based on hourly precipitation data between April and September during the period 1991–2009. SDHR is a low probability event with small occurrence frequencies. Despite some differences, the spatiotemporal frequency distributions of MCSs and SDHR exhibit substantial coherence. This coherence holds when SDHR is defined as hourly rainfall intensity≥ 10, 20, 30, or 40 mm h−1, and confirms the synoptic and climatological significance of the SDHR distributions analyzed in this paper.

In general, the spatial distributions of SDHR in China defined using thresholds of 10, 20, 30, or 40 mm h−1 are very similar to the distribution of heavy rainfall with intensity≥ 50 mm day−1. By contrast, the spatial distribution of SDHR with intensity≥ 50 mm h−1 is more scattered, with a stronger similarity to the spatial distribution of heavy rainfall with intensity > 100 mm day−1. The heaviest hourly rainfall observed in China during this period was more than 180 mm. Although SDHR with intensity≥ 50 mm h−1 is rare, it has been observed to occur even in regions with very weak SDHR activity.

The monthly mean frequency distribution of SDHR averaged over all of China is unimodal, and is closely related to the variability of the East Asian summer monsoon. The average frequencies of SDHR increase gradually from April to July and then decrease rapidly in September. The pentad mean frequency distribution of SDHR is largest in the fourth pentad of July, followed by the first and second pentads of August. The SDHR frequency develops intermittently and in phases. The pentad-by-pentad development of SDHR activity may be unimodal or multimodal, depending on the region, but generally contains multiple periods of strong SDHR activity. The frequency of SDHR occurrence is lower during spring and fall, but SDHR may still occur within a broad area of northern China during these transitional seasons.

The mean diurnal cycles of SDHR frequency and maximum hourly rainfall averaged over China as a whole are trimodal. The primary maximum in this diurnal cycle occurs during the afternoon(1600–1700 BT); this peak is consistent with the primary maximum in the diurnal cycle of MCS activity. There are also two secondary peaks during the midnight and early morning hours(0100–0200 and 0700–0800 BT, respectively), which do not appear in the diurnal cycle of MCS activity. SDHR frequency averaged over all of China is minimum in the morning. Changes in the mean SDHR frequency are more gradual after midnight.

The mean diurnal cycles of SDHR averaged within different regions of China have several different characteristic types(including single-peak, doublepeak, and multiple-peak). The main periods and relative durations of SDHR differ substantially over different underlying surfaces. Diurnal variations in SDHR and MCSs have many common features over most regions of China, but often differ significantly after midnight.

The diurnal variations of SDHR and MCSs along various transects in southern China show that therelated convective systems often propagate in characteristic patterns. MCSs frequently propagate overthe Sichuan basin, the region of Hubei and Anhuiprovinces near 31°N, and from the southeastern partof the western Sichuan plateau to the coastal area ofGuangxi via the northeast Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau(southwestern Guizhou).

The diurnal variations and propagation patternsof SDHR and MCSs are closely related to topography and the distribution of l and and sea. The localcirculations and convergence caused by differentialheating by solar radiation during the daytime and cooling by outgoing long wave radiation during thenighttime are largely consistent with the diurnal variations and propagation of SDHR and MCS systems(although these local circulation systems are typicallyvery shallow in the vertical direction). The influenceof multi-scale interactions between these local circulations and large-scale circulation systems on diurnalvariations of SDHR and MCS activities will requiredetailed analysis in future studies.

Acknowledgments. The authors would liketo thank Ruan Xin of the National Meteorological Information Center of China for providing thehourly precipitation data. The language editor forthis manuscript is Dr. Jonathon S. Wright.

| Central Meteorological Bureau, 1975: Climatology of Upper Air in China. China Science Press, Beijing, 11-17. (in Chinese) |

| Chen Haoming, Yu Rucong, Li Jian, et al., 2010: Why nocturnal long-duration rainfall presents an eastward-delayed diurnal phase of rainfall down the Yangtze River valley. J. Climate, 23(4), 905-917. |

| Chen Longxun, Zhu Qiangen, Luo Huibang, et al., 1991: East Asian Monsoon. China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 1-93. (in Chinese) |

| China Meteorological Administration, 2007: Climatological Atlas of Disastrous Weather in China. China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 21-31. (in Chinese) |

| Davis, R. S., 2001: Flash flood forecast and detection methods. Meteor. Monog., 28(50), 481-526. |

| Ding Yihui and Zhang Jianyun, 2009: Heavy Rain and Flood. China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 16-23. (in Chinese) |

| Hydrology Bureau of Ministry of Water Resources (MWR) of China, Nanjing Hydraulic Research Institute, 2006: Statistical Parameter Atlas of Heavy Rain in China. China Water Power Press, Beijing, 25-26. (in Chinese) |

| Hydrological Bureau of the Yangtze River Water Resources Commission of Ministry of Water Resources (MWR) of China, Nanjing Institute of Hydrology and Water Resources, 1995: Hydroelectric Engineering Design Flood Calculation Manual. China Water Power Press, Beijing, 197-218. (in Chinese) |

| Huang Shisong, Li Zhenguang, Bao Chenglan, et al., 1986: Heavy Rain in the First Rainy Season over South China. Guangdong Science and Technology Press, Guangdong, 17-19. (in Chinese) |

| Huang Yan, Feng Guolin, and Dong Wenjie, 2011: Temporal changes in the patterns of extreme air temperature and precipitation in the various regions of China in recent 50 years. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 69(1), 125-136. (in Chinese) |

| Li Jian, Yu Rucong, and Wang Jianjie, 2008a: Diurnal variations of summer precipitation in Beijing. Chinese Sci. Bull., 53(12), 1933-1936. |

| —-, —-, and Zhou Tianjun, 2008b: Seasonal variation of the diurnal cycle of rainfall in southern contiguous China. J. Climate, 21(22), 6036-6043. |

| Ma Ming, Tao Shanchang, Zhu Baoyou, et al., 2005: Climatological distribution of lightning density observed by satellites in China and its circumjacent regions. Sci. China (Ser. D), 48(2), 219-229. |

| Shen Lelin, He Jinhai, Zhou Xiuji, et al., 2010: The regional variability of the summer rainfall in China and its relation with anomalous moisture transport during the recent 50 years. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 68(6), 918-931. (in Chinese) |

| Tao Shiyan et al., 1980: Heavy Rains in China. China Science Press, Beijing, 5-7. (in Chinese) |

| Wang Xiaofang and Cui Chunguang, 2012: Analysis of the linear mesoscale convective systems during the Meiyu period in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. Part I: Organization mode features. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 70(5), 909-923. (in Chinese) |

| Wang Ying, Zheng Yongguang, and Shou Shaowen, 2009: Distribution and spatiotemporal variations of cloudto-ground lightning over the Yangtze River basin and adjacent areas during the summer of 2007. Meteor. Mon., 35(10), 58-70. (in Chinese) |

| Yao Li, Li Xiaoquan, and Zhang Limei, 2009: Spatialtemporal distribution characteristics of hourly rain intensity in China. Meteor. Mon., 35(2), 80-87. (in Chinese) |

| Yu Rucong, Zhou Tianjun, Xiong Anyuan, et al., 2007a: Diurnal variations of summer precipitation over contiguous China. Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, L01704, doi: 10.1029/2006GL028129. |

| —-, Xu Youping, Zhou Tianjun, et al., 2007b: Relation between rainfall duration and diurnal variation in the warm season precipitation over central eastern China. Geophys. Res. Lett., 34, L13703, doi:10.1029/2007GL030315. |

| Zhang Chunxi, Zhang Qinghong, and Wang Yuqing, 2008: Climatology of hail in China: 1961-2005. J. Appl. Meteor. Climatol., 47(3), 795-804. |

| Zhang Huan and Zhai Panmao, 2011: Temporal and spatial characteristics of extreme hourly precipitation over eastern China in the warm season. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 28(5), 1177-1183. |

| Zhang Jiacheng and Lin Zhiguang, 1985: Climate of China. Shanghai Science and Technology Press, Shanghai, 411-436. (in Chinese) |

| Zheng Yongguang and Chen Jiong, 2011: A climatology of deep convection over South China and adjacent seas during summer. J. Trop. Meteor., 27(4), 495-508. |

| —-, —-, Chen Mingxuan, et al., 2007: Statistic characteristics and weather significance of infrared TBB during May-August in Beijing and its vicinity. Chinese Sci. Bull., 52(24), 3428-3435. |

| —-, Lin Zhiguang, and Zhu Peijun, 2008: Climatological distribution and diurnal variation of mesoscale convective systems over China and its vicinity during summer. Chinese Sci. Bull., 53(10), 1574-1586. |

| —-, Wang Ying, and Shou Shaowen, 2010: Climatology of deep convection over the subtropics of China during summer. Acta Sci. Nat. Univ. Pekin., 46(5), 793-804. (in Chinese) |

| Zhou Tianjun, Yu Rucong, Chen Haoming, et al., 2008: Summer precipitation frequency, intensity, and diurnal cycle over China: A comparison of satellite data with raingauge observations. J. Climate, 21(16):3997-4010. |

| Zhou Xiuji, Xue Jishan, Tao Zuyu, et al., 2003: The Experiment and Research of Heavy Rain over South China in 1998. China Meteorological Press, Beijing, 4-5. (in Chinese) |

2013, Vol. 28

2013, Vol. 28