The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- SoNG Jinjie, WU Rongsheng, QUAN Wanqing and YANG Cheng. 2013.

- Impact of the Subtropical High on the Extratropical Transition of Tropical Cyclones over the Western North Pacific

- J. Meteor. Res., 27(4): 476-485

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-013-0410-6

-

Article History

- Received January 7, 2013

- in final form 2 March, 2013

During the boreal summer and autumn, recurvingtropical cyclones(TCs)often experience extratropicaltransitions(ETs) and become fast-moving and explosive midlatitude cyclones bringing about intenserainfall, very large waves(over 20 feet or 6 m), and hurricane-force winds(Jones et al., 2003). Most previousstudies of ETs have focused on interactions betweendecaying TCs and the midlatitude circulation, particularly the upper-level trough, as ETs can onlyoccur when TCs move to higher latitudes(Jones et al., 2003). This interaction is very sensitive to the developmentalphase of both the cyclone and the midlatitudecirculation that the storm approaches(Harr and Elsberry, 2000; Harr et al., 2000; Klein et al., 2000, 2002;Ritchie and Elsberry, 2007). Meanwhile, the evolutionof midlatitude systems downstream of the transitioningTC is often influenced by the ET process(Harr et al., 2008; Anwender et al., 2008; Harr and Dea, 2009).

The midlatitude circulation to the polar side ofthe cyclone is only one of the two large-scale weathersystems that influence ET processes over the westernNorth Pacific(WNP), the other being the western Pacificsubtropical high(WPSH)to the equatorward sideof the storm. The relationship between the transitioningstorm and the WPSH has received much lessattention than the relationship between the cyclone and the midlatitude circulation. The WPSH plays animportant role in the global circulations of the atmosphere and ocean. Meanwhile, the activity of WNPTCs can be influenced by the WPSH. For instance, downdrafts in the WPSH suppress tropical cyclogenesis(Gray, 1968) and the paths of individual cyclonesare greatly affected by steering flows related to the position and intensity of the WPSH(George and Gray, 1976). Some long-term trends in TC activity are alsosignificantly correlated with long-term changes in theWPSH. For example, an increase in the number ofTCs making l and fall over East Asia in recent decadeshas been related to the intensification and westwardexpansion of the WPSH(Ho et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2005; Liu and Chan, 2008; Chen et al., 2009).

Despite the relative inattention to the potentialrole of the WPSH in regulating ETs, this topic hasbeen partially addressed by a few previous studies. Jiet al.(2010)analyzed the role of the WPSH in thetransition of Typhoon Winnie using a mesoscale numericalmodel. They found that a stronger WPSH acceleratedthe northward movement of Typhoon Winnie.Furthermore, cold air from the middle and uppertroposphere intruded into the storm earlier than wouldhave happened under a weaker WPSH, quickening thetransition of the cyclone. By contrast, the intensification and westward extension of the WPSH caused thecyclone to move in a straight path rather than recurvinginto midlatitude westerlies, inhibiting the transitionof the storm into an extratropical cyclone. Althoughinstructive, this study derived from only oneET case. It is still unknown whether these conclusionsapply to other ET cases or on longer timescales.

This study focuses on interannual co-variability inthe WPSH and ET activities. Potential relationshipsbetween the probability of ET and the characteristicsof the WPSH are explored with two main objectives:to consider how the ET process may be affected bythe WPSH, and to establish some criteria for estimatingthe occurrence of ET. The data and methodologyare described in Section 2, the results are presentedin Section 3, and the conclusions are summarized inSection 4.2. Data and methodology

Tropical cyclone tracks are taken from the besttrack data provided by the Regional Specialized MeteorologicalCenter(RSMC)–Tokyo Typhoon Center ofthe Japan Meteorology Agency(JMA). The RSMC–Tokyo best track algorithm classifies a storm as extratropicalwhen it has lost all its tropical features. Atransitioning TC is therefore defined as a storm thathas completed ET to become an extratropical cyclone.The RSMC–Tokyo defines ET events primarily basedon aircraft surveillance and satellite imagery. Whenthe annular deep convection around the center of thestorm is shown to have shifted northeastward, cold and dry air is assumed to have intruded into the surface circulationcenter(JMA, 1990; Kitabatake, 2008).

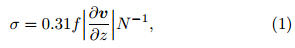

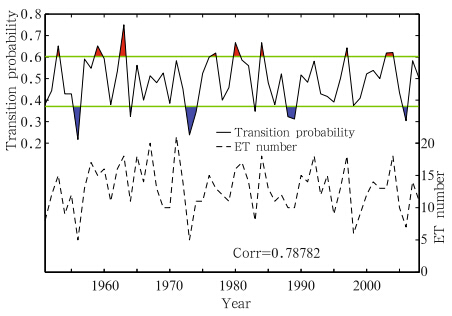

The annual number of ET events and the transitionprobability of all TCs(including both conventionalTCs and TCs that have completed ET)over theWNP from 1951 to 2008 are shown in Fig. 1. Thesetwo quantities are highly correlated. These 58 annualsamples are categorized into three groups using ±1st and ard deviation in the transition probability: positiveanomaly(9 yr), negative anomaly(8 yr), and neutral(41 yr). The sample is classified into the positiveanomaly group when the transition probabilityis larger than 0.61, and the negative anomaly groupwhen the transition probability is smaller than 0.38.Only ET events that occur between May and Octoberare considered. This restriction accounts for the factthat the transition probabilities of different groups canbe clearly distinguished between May and October, aswell as the fact that the number of ETs is much higherin these than in other months(Fig. 2).

|

| Fig. 1. Annual variations in the number of ET events(dashed line) and the transition probability of TCs over theWNP basin(solid line)from 1951 to 2008. The 58-yr correlation coefficient between these two quantities is 0.78(statistically significant at the 0.01 level based on t-test).Red color indicates a positive anomaly in the transitionprobability while blue indicates a negative anomaly. Theanomalies have exceeded ±1 st and ard deviation around the58-yr mean. |

|

| Fig. 2. Monthly variations in the number of ETs and thetransition probability of TCs over the WNP basin from1951 to 2008. Red, blue, and black lines indicate the transition probabilities classified as positive anomaly, negativeanomaly, and neutral, respectively. Yellow bars indicatethe cumulative number of ET events that occurred in eachmonth between 1951 and 2008. |

The impact of the WPSH on ET is consideredby analyzing the following two datasets for the period1951–2008, i.e., monthly mean NCEP/NCAR reanalysisdata(Kalnay et al., 1996) and monthly meansea surface temperature(SST)data from the NationalOceanic and Atmospheric Administration(NOAA)Extended Reconstructed SST−V3(Smith et al., 2008).The reanalysis data are provided at a 2.5°×2.5° horizontalresolution, while the NOAA SST data are providedat a 2°×2° horizontal resolution. The spatialextent of the WPSH is often defined according to the5880-gpm isolines in the 500-hPa geopotential heightfield. Here, the 5870-gpm isoline is used to account forsystematic low biases in 500-hPa geopotential heightin reanalysis data relative to upper-air soundings(He and Gong, 2002). The strength of the WPSH is definedas the area enclosed by this contour(Zhou et al., 2009). This definition of the WPSH is consistent withthe definitions used by Xu and Yang(1993), He and Gong(2002), and Zhou et al.(2009).3. Results3.1 Characteristics of the western Pacific subtropical high

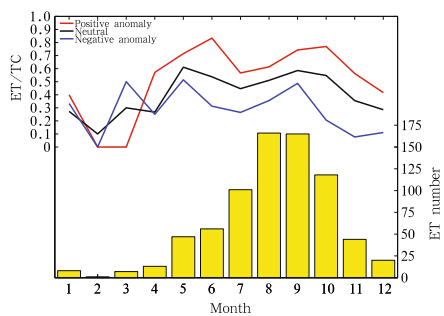

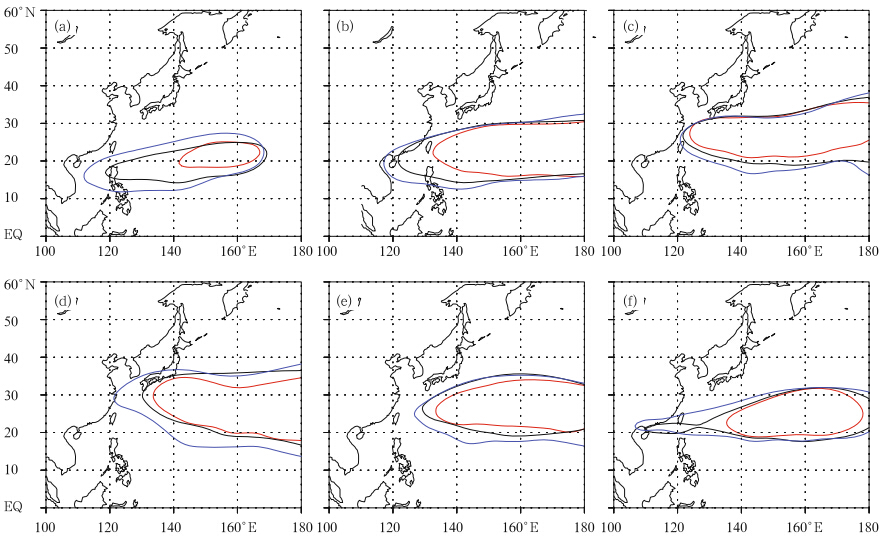

Figure 3 shows spatial distributions of the correlationcoefficients between 500-hPa geopotential height and the transition probability of TCs for 6 differentmonths during the period 1951–2008. The most significantcorrelations between June and October(Figs.3b–f)are located in the subtropical northwestern Pacific(15°–30°N), where the dominant circulation featureis theWPSH. This result suggests that the WPSHplays an important role in determining the transitionprobability of TCs. The transition probabilityis negatively correlated with geopotential height westof 140°E between May and October. Together with anearby area of positive correlation, this region of negativecorrelation forms a southwest-northeast-orienteddipole during July, August, and September, when thetransition probability is relatively low(Fig. 2). Bycontrast, the dipole is oriented west-east in May, June, and October, when the transition probability is relativelyhigh. Significant negative correlations are alsofound near Taiwan starting in June. The area of thisnegative correlation center is the largest in July, butthe lowest correlation(< –0.5)occurs in September(Fig. 3). This area is greatly influenced by theWPSH.These results imply that the transition probability ishighly correlated with weather systems in the subtropicalmiddle troposphere, particularly the WPSH.

|

| Fig. 3. Correlation coefficients between TC transition probability and monthly mean 500-hPa geopotential heightduring 1951–2008 in(a)May, (b)June, (c)July, (d)August, (e)September, and (f)October. Shading indicatesstatistical significance at the 0.05 level based on thet-test. Red, blue, and black lines indicate positive, negative, and zero correlation coefficients, respectively. |

Figure 3 also indicates that no areas in the extratropicsare significantly correlated with TC transitionprobability. Although the midlatitude circulationstrongly affects the transition process in many cases(Harr and Elsberry, 2000; Harr et al., 2000; Klein et al., 2000, 2002), interannual variations in the likelihoodof transition are not determined by systematicchanges in extratropical systems.

The spatial patterns of the WPSH associated withpositive, negative, and neutral anomalies in transitionprobability are shown in Fig. 4. The most significantdifferences among these spatial patterns are in thezonal position of the WPSH. Shifts in the north-southdirection are not significant. The western margin ofthe WPSH is consistently located farther toward theeast in the positive anomaly group than in negativeanomaly group for all six months. The most notabledifference occurred in May, when the western edge ofthe WPSH for the positive anomaly group was locatedaround 140°E but the western edges of the WPSH forthe neutral and negative anomaly groups were locatednear 120° and 110°E, respectively. The TC transitionprobability is generally higher when the western marginof the WPSH is located further east.

|

| Fig. 4. Composite 5870-gpm contour of 500-hPa geopotential height for years with positive(red lines), negative(bluelines), and neutral(black lines)TC transition probability anomalies in(a)May, (b)June, (c)July, (d)August, (e)September, and (f)October. |

The second significant difference in Fig. 4 is in thestrength of the WPSH, defined as the area enclosed bythe 5870-gpm isoline of 500-hPa geopotential height(Xu and Yang, 1993). The WPSH was consistentlyweaker in all months during positive anomaly yearsthan during negative anomaly years. Furthermore, theWPSH was much weaker in May and October(whenthe TC transition probabilities were relatively high;see Fig. 2)than in other months. On both interannual and seasonal scales, TCs are more likely to undergoET when the WPSH is weaker and less likelywhen the WPSH is stronger.

Third, the seasonal cycle of the WPSH differs fordifferent anomaly groups. During positive anomalyyears, the western margin of the WPSH extendedwestward from May(140°E)to July(125°E), and thenwithdrew eastward from July to October(137.5°E).During negative anomaly years, the western margin ofthe WPSH shifted farthest to the west(around 110°E)in May and October, with a slight withdrawal towardthe east in September(127.5°E).3.2 Shifts in the prevailing storm tracks

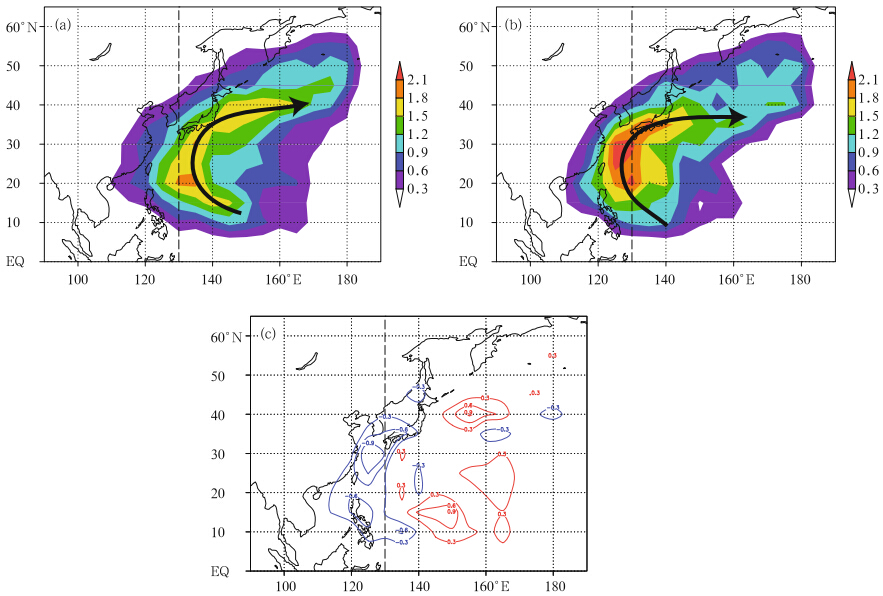

The tracks of TCs depend primarily on large-scalesteering flows such as the predominant easterly and westerly winds along the southern and northern edgesof the WPSH, respectively(George and Gray, 1976).The position of the western margin of the WPSHtherefore has a significant impact on the typical tracksof nearby TCs. Figure 5 shows the prevailing tracks ofTCs that underwent ET from years with positive and negative anomalies in transition probability. Regardlessof the sign of the anomaly, the majority of transitioningTCs followed recurving-north or recurvingnortheastpaths. No transitioning TCs followed a directwestward path, because westward-moving TCs hitthe mainl and of East Asia and dissipated prior to transition.This result implies that a transitioning TCmoves along the edge of the WPSH during its lifetime, since the storm moves westward to the south ofthe WPSH and eastward to the north.

Large numbers of transitioning TCs recurved eastof 130°E in the positive anomaly group(Fig. 5a), whereas TC tracks from the negative anomaly grouprecurved mainly to the west of 130°E(Fig. 5b).Furthermore, the relative frequency of cyclones observedto the east of 130°E was higher in the positiveanomaly group than in the negative anomaly group, while the relative frequency of cyclones observed tothe west of 130°E was lower in the positive anomalygroup than in the negative anomaly group(Fig. 5c).These differences are related to the meridional locationof the western margin of the WPSH. TCs generatedat lower latitudes cannot recurve to the north and east until they have approached the western margin ofthe WPSH. The recurving locations of TC tracks aretherefore farther west than normal when the WPSH isstrengthened and extended westward.

|

| Fig. 5. May–October relative occurrence frequency(%)for transitioning TCs in the WNP from(a)positive anomalyyears, (b)negative anomaly years, and (c)positive anomaly years minus negative anomaly years. Black dashed linesindicate the location of 130°E. Red and blue lines in(c)indicate positive and negative values, respectively. Black solidlines with arrows represent the prevailing storm tracks. |

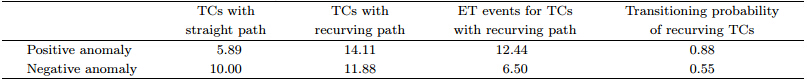

The tracks for all TCs also differ significantly betweenthe positive and negative anomaly groups(Fig. 6). Both anomaly groups include both straight and recurving TC tracks, but the percentages of TCs thatcluster along these tracks are distinct. Recurving TCsare defined here as TCs that move into the area northof 20°N and east of 120°E before dissipating(Kitabatake, 2011). TCs that do not meet these criteriaare considered to have followed straight paths. Table 1 lists the average numbers of TCs with straight and recurving paths for the positive and negative anomalygroups. The average number of TCs with recurvingpaths is larger in the positive anomaly group than inthe negative anomaly group, while the average numberof TCs with straight paths is larger in the negativeanomaly group than in the positive anomalygroup. More TCs moved straight to the west ratherthan recurving northward in the negative anomalygroup(Fig. 6b). This difference is also related to differencesin the strength and position of the WPSH.Harr and Elsberry(1991) and Chen et al.(2009)pointed out that an intensification of the WPSH associatedwith a weak monsoon trough leads to morestraight-moving TCs, while recurving TCs are linkedto a weak WPSH and a deepened monsoon trough.When the WPSH weakens and withdraws eastward, TCs are more likely to recurve to higher latitudes, witha greater chance of entering the midlatitude circulation.The transition probabilities for recurving stormsare also different for different anomaly groups(Table 1). The transition probability of recurving stormsin positive anomaly group(0.88)is much larger thanthat in negative anomaly group(0.55). This differencearises because a weaker WPSH with a more eastwardlocatedwestern boundary is always associated with adeepened upper-level trough in East Asia. This deepenedupper-level trough promotes ET.

|

|

| Fig. 6. May–October storm occurrence relative frequency(%)of TCs in the WNP for(a)positive and (b)negativeanomaly years. Black dashed lines indicate the location of 25°N. Black solid lines with arrows represent the prevailingstorm tracks. |

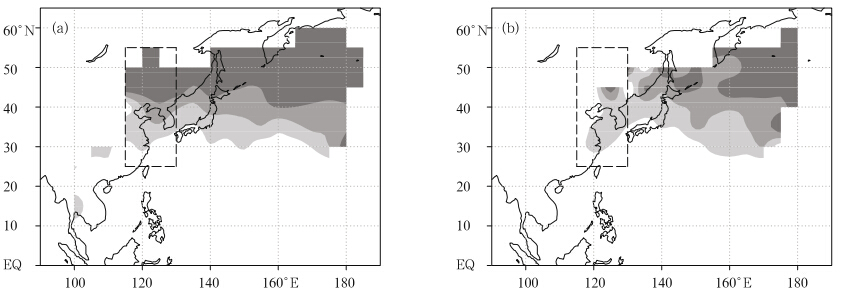

Although TCs recurving to higher latitudes havethe potential to undergo ET, the spatial distributionsof transition probability are different between the positive and negative anomaly groups(Fig. 7). If TCcases from May to October are considered as a whole, the transition probability for cyclones moving into theregion east of 130°E is similar for both groups, withincreases in the transition probability at higher latitudes.When storm centers are located north of 20°N and west of 130°E(dashed box in Fig. 7), the transitionprobability is larger during positive anomalyyears.

|

| Fig. 7. Spatial distributions of TC transition probability averaged over May–October in the WNP basin for(a)positive and (b)negative anomaly years. Light, medium, and dark shadings represent probabilities of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8, respectively. |

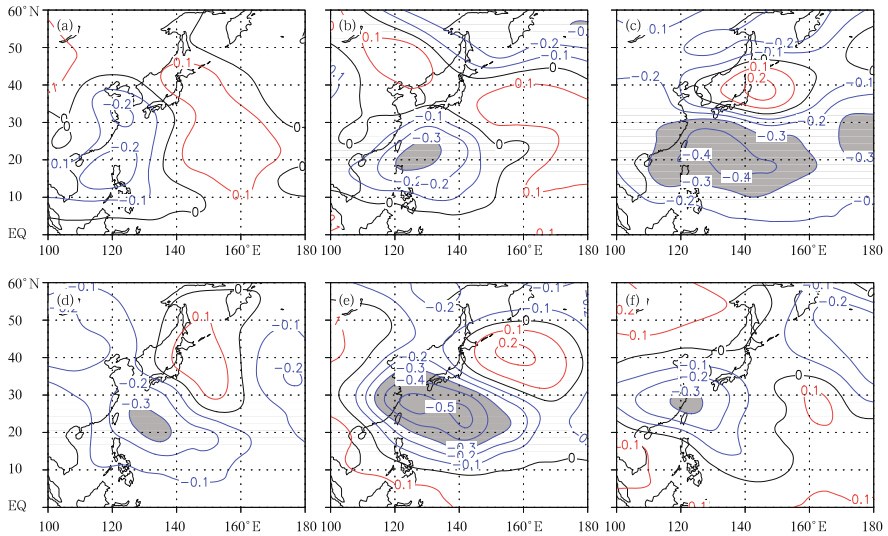

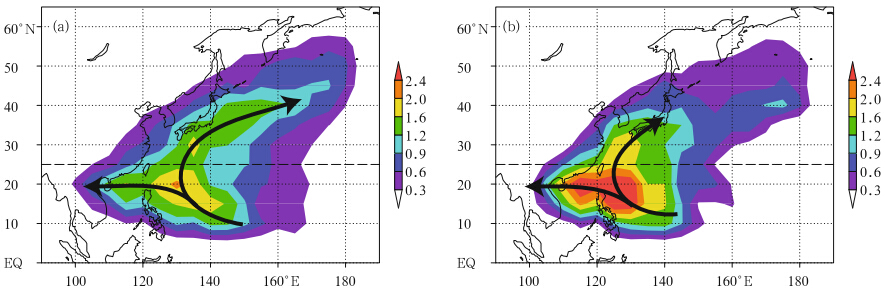

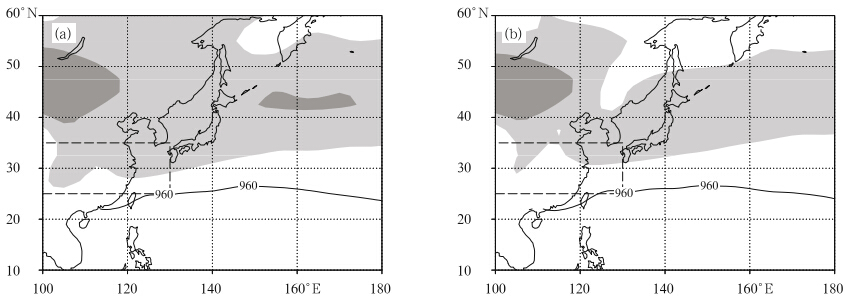

Figure 8 shows the May–October average spatialdistributions of cyclone maximum potential intensity(MPI) and the 700-hPa Eady baroclinic growth rateparameter(σ). The former is calculated under theassumption that TC thermodynamics approximate aCarnot engine(Emanuel, 1988; Bister and Emanuel, 1998). The latter has been defined by Hoskins and Valdes(1990)as

|

| Fig. 8. Composite May–October distribution of 700-hPa Eady baroclinic growth rate(light and dark shadings at 0.25 and 0.5 day−1, respectively) and 960-hPa tropical cyclone MPI(solid lines)from(a)positive and (b)negative anomalygroups. |

When a TC moves across the 960-hPa MPI contour, the storm starts to weaken and ET is initiated.If the storm moves into an area with a greater Eadybaroclinic growth rate(≥ 0.25 day−1)before dissipation, it is likely to complete the ET process and developas an extratropical cyclone. If the storm movesinto an area with a small Eady baroclinic growth rate(< 0.25 day−1), it is likely that the ET process willnot be completed and the storm will not be recordedas a transitioning TC.4. Conclusions and discussion

TCs moving into higher latitudes are likely toundergo extratropical transition(ET), during whichstorms lose their tropical characteristics. TCs thatundergo ET can cause great losses of life and property.Many recent studies of ET have focused on theinteractions between TCs and the midlatitude circulation.By contrast, this study has focused on therelationship between transitioning TCs in the WNP and the WPSH. The observations from 1951 to 2008have been divided into three groups according to TCtransition probability: positive anomaly, neutral, and negative anomaly. The six months from May to Octoberhave been chosen to illustrate the influence of theWNP on ET.

The atmospheric circulation over theWNP differssignificantly between the two anomaly groups. Duringpositive anomaly years, the WPSH often withdrawseastward and relatively weak. These conditions leadto a more frequent occurrence of recurving TC tracks.Cyclones during these years also tend to recurve tonorth or northeast at longitudes farther east. Duringnegative anomaly years, the WPSH strengthens and extends westward. Most TCs during these yearsfollow a straight westward path and make l and fall atrelatively low latitudes. The likelihood of ET is lowfor these storms. TCs that transition during negativeanomaly years tend to enter the extratropics fartherwestward.

These results reflect the fact that the movementof TCs is primarily determined by large-scale steeringflows associated with the WPSH(George and Gray, 1976). When the WPSH strengthens and extendswestward, more low-latitude TCs move directly towardthe west, with little opportunity to enter themidlatitude circulation(Fig. 6).

TCs that move into the midlatitudes are morelikely to transition into extratropical cyclones duringpositive anomaly years than during negative anomalyyears(Fig. 7). This difference is caused by an enhancementof the westerly trough during positiveanomaly years, rather than by the steering flow. Aneastward retreat of the WPSH is often correlated witha strengthened trough. When an eastward shift in thewestern boundary of the WPSH is accompanied by adeepened trough, the region that favors baroclinic developmentextends further south(to about 25°N; seeFig. 8). This increases the transition probability forstorms that recurve to the west of 130°E. By contrast, the large separation between the baroclinically activeregion(shaded area in Fig. 8b) and the boundary ofthe TC intensification region(960-hPa MPI contour)reduces the transition probability of cyclones duringnegative anomaly years.

Month-to-month variations in the TC transitionprobability are also linked to the strength and positionof the WPSH. The transition probability is thehighest in May, June, and October, when the WPSHis the weakest. By contrast, the transition probabilityis relatively low in July, August, and September, when the WPSH is stronger and its western boundaryis shifted further westward.

In summary, both annual and monthly variationsin the TC transition probability are greatly influencedby changes in the position and strength of the WPSH.This suggests that accurate predictions of the characteristicsof the WPSH could improve forecasts of ETevents. Changes in the WPSH are coupled with otherlarge-scale circulations, such as the East and SoutheastAsian summer monsoons(Tao and Chen, 1987;Wu and Wang, 2000; Chen et al., 2004, 2009) and ElNiño-Southern Oscillation(ENSO)events(Wang and Chan, 2002; Yun et al., 2010). Further relationshipsbetween the large-scale circulation and the likelihoodof ET should be explored in future work.

Acknowledgments. We wish to express oursincere thanks to the anonymous reviewers for theirhelpful comments on an earlier version of thismanuscript. The language editor for this manuscriptis Dr. Jonathon S. Wright.

| [1] | Anwender, D., P. A. Harr, and S. C. Jones, 2008: Predictability associated with the downstream impacts of the extratropical transition of tropical cyclones: Case studies. Mon. Wea. Rev., 136 (9), 3226-3247. |

| [2] | Bister, M., and K. A. Emanuel, 1998: Dissipative heating and hurricane intensity. Meteor. Atmos. Phys., 65 (3-4), 233-240. |

| [3] | Chen, T. -C., S. -Y. Wang, W. -R. Huang, and M. -C. Yen, 2004: Variation of the East Asian summer monsoon rainfall. J. Climate, 17 (4), 744-762. |

| [4] | ——, ——, M. -C. Yen, et al., 2009: Impact of the intraseasonal variability of the western North Pacific large-scale circulation on tropical cyclone tracks. Wea. Forecasting, 24(3), 646-666. |

| [5] | Emanuel, K. A., 1988: The maximum intensity of hurricanes. J. Atmos. Sci., 45 (7), 1143-1155. |

| [6] | George, J. E., and W. M. Gray, 1976: Tropical cyclone motion and surrounding parameter relationships. J. Appl. Meteor., 15 (12), 1252-1264. |

| [7] | Gray, W. M., 1968: Global view of the origin tropical disturbances and storms. Mon. Wea. Rev., 96 (10), 669-700. |

| [8] | Harr, P. A., and R. L. Elsberry, 1991: Tropical cyclone track characteristics as a function of large-scale circulation anomalies. Mon. Wea. Rev., 119 (6), 1448-1468. |

| [9] | ——, and ——, 2000: Extratropical transition of tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific. Part I: Evolution of structural characteristics during the transition process. Mon. Wea. Rev., 128(8), 2613-2633. |

| [10] | ——, ——, and T. F. Hogan, 2000: Extratropical transition of tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific. Part II: The impact of midlatitude circulation characteristics. Mon. Wea. Rev., 128(8), 2634-2653. |

| [11] | ——, D. Anwender, and S. C. Jones, 2008: Predictability associated with the downstream impacts of the extratropical transition of tropical cyclones: Methodology and a case study of Typhoon Nabi (2005). Mon. Wea. Rev., 136(9), 3205-3225. |

| [12] | ——, and J. M. Dea, 2009: Downstream development associated with the extratropical transition of tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific. Mon. Wea. Rev., 137(4), 1295-1319. |

| [13] | Hart, R. E., and J. L. Evans, 2001: A climatology of the extratropical transition of Atlantic tropical cyclones. J. Climate, 14 (4), 546-564. |

| [14] | He, X., and D. Gong, 2002: Interdecadal change in the western Pacific subtropical high and climatic effects. J. Geogr. Sci., 12 (2), 202-209. |

| [15] | Ho, C. H., J. J. Baik, J. H. Kim, D. Y. Gong, and C. H. Sui, 2004: Interdecadal changes in summertime typhoon tracks. J. Climate, 17 (9), 1767-1776. |

| [16] | Hoskins, B. J., and P. J. Valdes, 1990: On the existence of storm-tracks. J. Atmos. Sci., 47 (15), 1854-1864. |

| [17] | Ji Liang, Fei Jianfang, and Huang Xiaogang, 2010: Numerical simulations of the effect of the subtropical high on landfalling tropical cyclones. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 68(1), 39-47. (in Chinese) (季亮, 费建芳, 黄小刚, 2010: 副热带高压对登陆台风影响的数值模拟研究. 气象学报, 68(1), 39-47.) |

| [18] | JMA, 1990: Manual of the Operational Forecasting of Tropical Cyclones (in Japanese). Japan Meteorological Agency, 150 pp. |

| [19] | Jones, S. C., and Coauthors, 2003: The extratropical transition of tropical cyclones: Forecast challenges, current understanding, and future directions. Wea. Forecasing, 18 (6), 1052-1092. |

| [20] | Kitabatake, N., 2008: Extratropical transition of tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific: Their frontal evolution. Mon. Wea. Rev., 136 (6), 2066-2090. |

| [21] | ——, 2011: Climatology of extratropical transition of tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific defined by using cyclone phase space. J. Meteor. Soc. Japan, 89(4), 309-325. |

| [22] | Klein, P. M., P. A. Harr, and R. L. Elsberry, 2000: Extratropical transition of western North Pacific tropical cyclones: An overview and conceptual model of the transformation stage. Wea. Forecasing, 15 (4), 373-396. |

| [23] | —-, —-, and —-, 2002: Extratropical transition of western North Pacific tropical cyclones: Midlatitude and tropical cyclone contributions to reintensification. Mon. Wea. Rev., 130(9), 2240-2259. |

| [24] | Liu, K. S., and J. C. L. Chan, 2008: Interdecadal variability of western North Pacific tropical cyclone tracks. J. Climate, 21 (17), 4464-4476. |

| [25] | Ritchie, E. A., and R. L. Elsberry, 2007: Simulations of the extratropical transition of tropical cyclones: Phasing between the upper-level trough and tropical cyclones. Mon. Wea. Rev., 135 (3), 862-876. |

| [26] | Smith, T. M., R. W. Reynolds, T. C. Peterson, and J. Lawrimore, 2008: Improvements to NOAA’s historical merged land-ocean surface temperature analysis (1880-2006). J. Climate, 21 (10), 2283-2296. |

| [27] | Tao, S. Y., and L. X. Chen, 1987: A review of recent research on the east Asian summer monsoon in China. In: Monsoon Meteorology, Oxford Press, 60-92. |

| [28] | Wang, B., and J. C. L. Chan, 2002: How strong ENSO events affect tropical storm activity over the western North Pacific. J. Climate, 15 (13), 1643-1658. |

| [29] | Wu, L., B. Wang, and S. Geng, 2005: Growing typhoon influence on East Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, L18703, doi:10.1029/2005GL022937. |

| [30] | Wu, R. G., and B. Wang, 2000: Interannual variability of summer monsoon onset over the western North Pacific and the underlying processes. J. Climate, 13 (14), 2483-2501. |

| [31] | ——, ——, and S. Q. Geng, 2005: Growing typhoon influence on East Asia. Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, L18703, doi: 10.1029/2005GL022937. |

| [32] | Xu, Q., and Q. M. Yang, 1993: Response of the intensity of subtropical high in the northern hemisphere to solar activity. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 10 (3), 325-334. |

| [33] | Yun, K. -S., K. -H. Seo, and K. -J. Ha, 2010: Interdecadal change in the relationship between ENSO and the intraseasonal oscillation in East Asia. J. Climate, 23 (13), 3599-3612. |

| [34] | Zhou, T. J., R. C. Yu, J. Zhang, et al., 2009: Why the western Pacific subtropical high has extended westward since the late 1970s. J. Climate, 22(8), 2199-2215. |

2013, Vol. 27

2013, Vol. 27