The Chinese Meteorological Society

Article Information

- WANG Runyuan, ZHANG Qiang, ZHAO Hong, WANG Heling and WANG Chunling. 2012.

- Analysis of the Surface Energy Closure for a Site in the Gobi Desert in Northwest China

- J. Meteor. Res., 26(2): 250-259

- http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13351-012-0210-4

-

Article History

- Received May 24, 2011

- in final form February 20, 2012

2 Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology, Nanjing 210044

Over an ideal(non-vegetated)horizontal surface, the energy flux leaving the surface should be equivalent to that received at the surface. Hence, the closureof the surface energy balance has been historically accepted as a fundamental validation of data quality, particularly for the accuracy of eddy-covariance data, with important implications for the estimates of carbon dioxide(CO2)flux(Twine et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 2002; Cava et al., 2008). Moreover, a good underst and ing of the mass and energy exchange betweenthe earth's surface and the atmosphere is fundamental for improving regional weather and global climatemodels(Yamanaka et al., 2007; Cava et al., 2008; Sturman and McGowan, 2009). During recent decades, theproblem of energy balance closure at the earth surfacehas been widely investigated.

Many experimental studies have indicated thatthe available energy(net radiation minus soil heatflux)is generally larger than the sum of the verticalturbulent heat fluxes(sensible heat plus latent heat).The ratio of heat fluxes to available energy, often calledthe recovery ratio, ranges within 70%-90% for various ecosystems(Tsvang et al., 1991; Kanemasu et al., 1992; Aubinet et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 2002; Kanda et al., 2004; Ma et al., 2005; Foken et al., 2006; Gao et al., 2007; Cava et al., 2008; Jacobs et al., 2008; Wang and Zhang, 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). Various hypotheses have been proposed to explain the observedsystematic imbalance of surface energy. They mainlyinclude 1)instrumental errors, especially those relatedto the eddy covariance techniques, 2)the data processing procedures(Foken and Wichura, 1996; Mauder et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2009), 3)the "inabilities"to make point observations using the eddy covariancesystem in the observation of larger eddy contributions(Steinfield et al., 2007; Mauder et al., 2008), 4)theenergy storage in the soil-vegetation-atmosphere system(Braud et al., 1993; Oncley et al., 2007; Yue etal 2011), 5)errors from measurements of net radiation especially in complex terrain(Kohsiek et al., 2007;Hiller et al., 2008), 6)errors produced by the loss oflow and /or high frequency contributions to the energytransport(Sakai et al., 2001; Finnigan et al., 2003;Foken et al., 2006), 7)the footprint effect(Schmid, 1997), and 8)the attack angle calibration(Cava et al., 2008).

Cava et al.(2008)showed that in an ecosystem in southern Italy consisting of short vegetation, the global energy closure rates improved from 0.82 to0.88 in summer and from 0.76 to 0.86 in autumn after correcting the errors dependent on the ultrasonicanemometer angle of attack, and after considering theheat storage into the soil, the global closure rate significantly improved to 1.02 in summer and 0.96 in autumn. Michiles and Gielow(2008)found that in a central Amazonian rainforest ecosystem in Brazil, the average residual increased approximately 25% and 20%for the dry and wet groups of days, respectively, whenthe aboveground thermal energy storage rates were nottaken into consideration in the calculation of the surface energy balance, and the trunks, air, and otherbiomass components contributed 40%, 35%, and 25%to the total daily energy storage rates of the forest, respectively. Meyers and Hollinger(2004)reportedthat in an agricultural ecosystem in central Illinois, when taken into separate consideration, the storageterms were generally a small fraction(< 5%)of thenet radiation, but the combination of canopy and soilheat storage and the stored energy in the carbohydratebonds from photosynthesis accounted for roughly 7%of the total net radiation for soybean and 15% formaize during the morning hours of 0600-1200 LT(local time)when the crop canopy had fully developed.Heusinkveld et al.(2004)considered a location in thes and y desert belt in Nizzana, Israel ideal for energybalance estimations since only the soil heat flux and sensible heat flux were balanced by the net radiation, and they found that a nearly perfect closed energybudget was achieved by using the harmonic analysistechnique in estimating the surface soil heat flux.

The focus of the present study was to evaluatethe energy budget closure for a Gobi Desert region inNorthwest China, and to evaluate the contribution ofthe heat storage terms to the energy closure in summer and winter, respectively.2. The field experiment2.1 Site and climate description

The field experiment was carried out at ZhangyeArid Meteorology and Ecological Environment Experimental Base of the Institute of Arid Meteorology ofthe China Meteorological Administration, which is located in the Zhangye Oasis in the middle part of theHexi Corridor in Northwest China(39°05′N, 100°16′E;1457-m elevation). The observation site has a flat underlying surface, covered by Gobi s and -gravel whichextends northward, and surrounded by cropl and and orchard on all the other sides, at distances of 2-3 km.The Gobi Desert has a typical arid geomorphology and is widely distributed in Northwest China. Its surfaceis usually flat, non-vegetated, covered with gravel, and has active wind erosion(Xue et al., 2002; Zhang and Huang, 2004). The surface represents an ideal(non-vegetated)horizontal surface for investigation of thesurface energy balance of the earth(Heusinkveld et al., 2004; Cava et al., 2008).

The average annual rainfall of the oasis region isabout 140 mm with a mean annual temperature of 7.6℃. The growing season is during April and October(Wang et al., 2004, 2008).2.2 Instrumentation

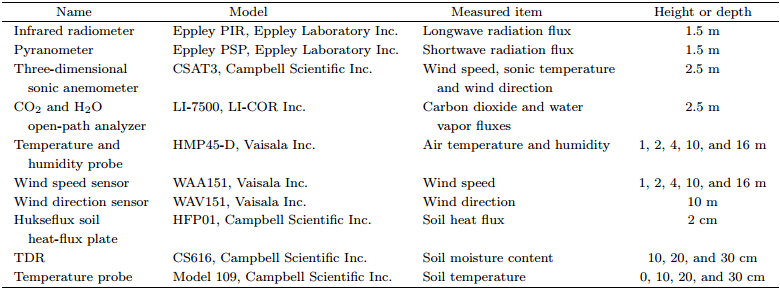

The incoming(RLi) and outgoing(RLo)longwaveradiation fluxes were measured with two precision infrared radiometers(Eppley PIR; Eppley LaboratoryInc.)at a height of 1.5 m. The incoming(Rgi) and outgoing(Rgo)shortwave radiation fluxes weremeasured with two precision pyranometers(EppleyPSP; Eppley Laboratory Inc.)at the same height.Isolation of long-wave radiation from solar short-waveradiation in daytime was accomplished during measurements using the Eppley PIR by using a siliconedome according to the manufacturer's specifications.The net radiation at 1.5-m height, Rnz, was determined by summing up the total radiation budget:

A tower was equipped with a three-dimensionalsonic anemometer for measuring wind speed, sonictemperature, and wind direction(CSAT3; Campbell Scientific Inc.), and a CO2 and H2O openpath analyzer(LI-7500 Infrared Gas Analyzer; LICOR Inc.)for measuring CO2 and H2O vaporflux. The instruments were mounted 2.5 m above theground.

In addition, a 16-m tower was set up on apedestal for obtaining wind speed, air temperature(Ta), and relative humidity(RH)profiles. The towerwas equipped with Ta and RH probes(HMP45-D;Vaisala Inc.)enwrapped by a radiation shield, windspeed sensors(WAA151; Vaisala Inc.)at heights of1, 2, 4, 10, and 16 m, and a wind direction sensor(WAV151; Vaisala Inc.)at a height of 10 m above theground for measuring Ta and RH, wind speed and direction, respectively.

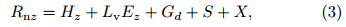

The soil heat flux was measured with three Hukseflux soil heat-flux plates(HFP01; Campbell Scientific Inc.)buried at a depth of 2 cm at three siteson a 1.5-m-radius circumference at an angle of 120°, with the result being the spatial averaging of the threesensors. During the measurement, aspects of differentthermal properties between the sensor and the environment could be dealt with more accurately usinga "self-calibrating" heat flux sensor according to themanufacturer's specifications. Soil moisture contentswere measured with a water content reflectometer-Time Domain Reflectometry(TDR)system(probetype CS616; Campbell Scientific Inc.)at depths of10, 20, and 30 cm. Soil temperatures were measuredby temperature probes(Model 109; Campbell Scientific Inc.)at depths of 0, 10, 20, and 30 cm. Details ofthe instruments used in the field experiment are givenin Table 1.

For data acquisition, we used CR5000, CR1000, and CR23X-TD dataloggers(Campbell Scientific Inc.)as storage media. A network of dataloggers was set up and managed by LoggerNet datalogger support software(Campbell Scientific Inc.). LoggerNet 2 supports programming, communications, and data retrieval between the dataloggers and a computer. Theslow response instruments were sampled at 0.2 Hz and the rapid ones were sampled at 10 Hz. Theraw data of the eddy covariance system were collected, stored, and processed at 30-min intervals byLoggerNet 2.

The field experiment consists of both summer and winter experiments. The summer experiment wasfrom 22 June to 20 July 2006, and the winter one wasfrom 26 December 2006 to 26 January 2007.3. Theory and methodology

Over an ideal(non-vegetated)horizontal surface, the surface energy balance is expressed as:

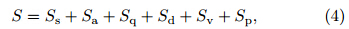

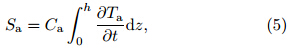

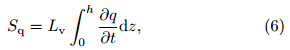

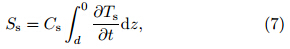

where Rn is net radiation flux, LvE is latent heat fluxat the interface between the earth's surface and atmosphere, G0 is surface soil heat flux, and H is sensible heat flux. The energy balance closure test shouldshow an imbalance in favor of the net radiation because these measurements are usually performed at acertain height or depth away from the surface. To illustrate this, a more complete energy balance equationis presented as:where Rnz is net radiation, LvEz is latent heat flux, Hz is sensible heat flux measured at height z, Gd issoil heat flux measured at depth d, Srepresents theadditional heat storage terms in the soil-vegetation-atmosphere system, and X is the residual error assocated with measurement and data calculation processes. X is often neglected for flat and extensive homogeneous locations. As shown below, S includes:where Ss is the soil heat storage flux between the soilsurface and the heat flux plate, Sa is the air enthalpychange, Sq is the atmospheric moisture change, Sd isthe canopy dew water enthalpy change, Sv is the vegetation enthalpy change, and Sp is the photosynthesis and respiration flux.In this study, Sp, Sv, and Sb could be ignored inthe surface energy balance equation because the surface was covered with s and -gravel and there was hardlyany vegetation on the underlying surface of the observation site during summer. There was no vegetationduring winter either, as Ta < 0 ℃.

Sa is calculated as

where Ta is measured in K, Ca is the volumetric heatcapacity for moist air, and h is the height of the eddycovariance system.Sq is calculated as

where Lv is the latent heat for vaporization and q isthe atmospheric moisture density.Ss is calculated as

where d is the depth of the soil heat flux plate, Cs isthe volumetric heat capacity of the soil, and Ts is thesoil temperature. In the actual calculations, according to the manufacturer's(Campbell Scientific Inc.)specifications, Eq.(7)is reduced to:where Δt is time interval.When the impact of the soil moisture contentchange on Ss is considered, Cs is calculated as,

where ρb is soil density(= 1400 kg m-3; Zhang et al., 2003) and θm is soil water content by weight(Li et al., 2007).When this impact is negligible, Cs is set as aconstant. For example, Cs is taken as 1.17 × 106 Jm-3 K-1(Zhang et al., 2003)in winter, because thesoil is very dry, and the frozen soil moisture contentmeasured by TDR is often overestimated(Du et al., 2004), leading to the impact of the soil moisture content change on Ss being ignored.

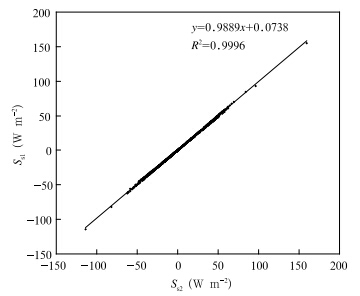

In fact, the impact of the soil moisture contentchange on Ss was also small in the 2006 summer experiment as shown in Fig. 1. In Fig. 1, Ss1 is obtained bysetting Cs=1.23×106 J m-3 K-1(a value for summerseason as in Zhang et al.(2003))without consideringthe soil moisture change, while Ss2 is obtained by using Eq.(9). Figure 1 shows that the linear regressionbetween Ss1 and Ss2 was y = 0.9889x + 0.0738, withR2 = 0.9996(sample number N = 1312; significanceP < 0.0001), implying that Ss1 was nearly equal toSs2. Thus, it is inferred that the impact of the soilmoisture content change on Ss was very small in the2006 summer experiment period, which was perhapsdue to soil drought.

|

| Fig. 1. Linear regression between Ss1 and Ss2. Ss1 and Ss2 are the soil heat storage fluxes at a depth of 0-2 cmin summer 2006 calculated by Eq.(8)with different Csvalues. |

Equations(5) and (6)were reduced analogouslyto Michiles and Gielow(2008):

where ρa and Cp are the density and specific heat atconstant pressure of the air, respectively, Ta the average temperature of the air volume from 0- to h-mheight, and q is the average specific humidity of theair volume.Heat storage changes were calculated over themeasurement averaging time interval of 30 min.Soil temperature and soil moisture content ata certain depth were respectively calculated bythe harmonic analysis and the linear interpolation technique-according to Darcy's Law(Philip, 2006). Observation data during rainy periods werediscarded due to malfunction of the instruments, such as the eddy covariance system, during theseevents.4. Results and discussion

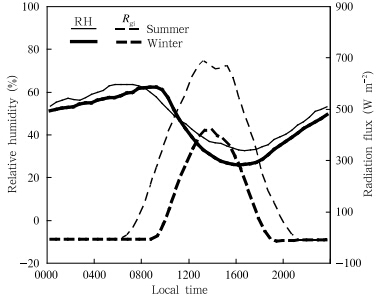

Data of both summer and winter experimentswere calculated and analyzed to determine the characteristics of the energy balance closure over the GobiDesert in Northwest China in these seasons. Thecorrelative meteorological variables during the experiments are plotted in Fig. 2, which indicates that summer was a bit wetter than winter and the incomingshortwave radiation flux in summer was twice of thatin winter.

|

| Fig. 2. Diurnal variation of relative humidity(RH; solidlines)at 0-2.5-m height and incoming shortwave radiation(Rgi; dashed lines)at 1.5-m height during summer(thinlines) and winter(thickened lines)experiments. |

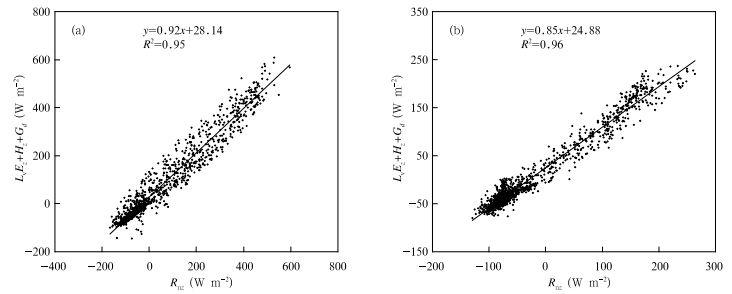

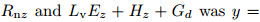

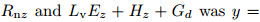

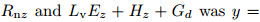

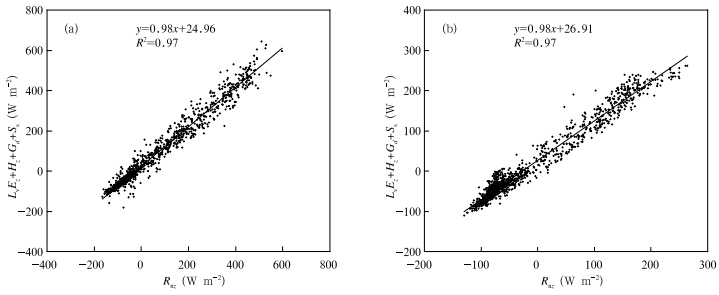

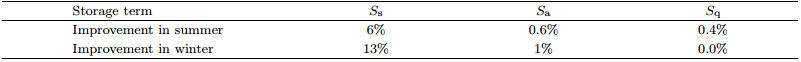

In the summer experiment(Fig. 3a), the linearregression between the 30-min averaged Rnz and LvEz+ Hz + Gd was y = 0.92x + 28.14, with R2 = 0.95(N= 1252, P < 0.0001), implying an imbalance of 8%. Inthe winter experiment(Fig. 3b), the linear regressionbetween Rnz and LvEz + Hz + Gd was y = 0.85x +24.88, with R2 = 0.96(N = 1385, P < 0.0001), implying an imbalance of 15%. This indicates that theenergy budget closure was not ideal in both summer and winter when the heat storage terms were not considered. Comparisons showed that the imbalance ofthe surface energy budget in winter was nearly a double of that in summer.

|

Fig. 3. Scattergram of 30-min averages of the sum of energy flux densities  and the net radiation Rnzin(a)summer and (b)winter. and the net radiation Rnzin(a)summer and (b)winter. |

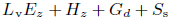

In the summer experiment(Fig. 4a), the linearregression between the 30-min averages of  0.98x + 24.96, with R2= 0.97(N = 1252, P < 0.0001), implying an imbalance of 2%. Thus, we conclude that considering thesoil heat storage flux resulted in an improvement ofthe imbalance by 6%. In the winter experiment(Fig. 4b), the linear regression between

0.98x + 24.96, with R2= 0.97(N = 1252, P < 0.0001), implying an imbalance of 2%. Thus, we conclude that considering thesoil heat storage flux resulted in an improvement ofthe imbalance by 6%. In the winter experiment(Fig. 4b), the linear regression between  0.98x + 26.91, with R2 =0.97(N = 1385, P < 0.0001), implying an imbalanceof 2%. Thus, considering the soil heat storage fluxhas reduced the imbalance by 13%. For both seasons, better results for the surface energy balance were obtained by calculating the soil heat storage term. Thetwofold difference in the surface energy imbalance between the winter and summer experiments was minorin consideration of the soil heat storage term.

0.98x + 26.91, with R2 =0.97(N = 1385, P < 0.0001), implying an imbalanceof 2%. Thus, considering the soil heat storage fluxhas reduced the imbalance by 13%. For both seasons, better results for the surface energy balance were obtained by calculating the soil heat storage term. Thetwofold difference in the surface energy imbalance between the winter and summer experiments was minorin consideration of the soil heat storage term.

|

Fig. 4. Scattergram of 30-min averages of sum of the energy flux densities  and the net radiationRnz in(a)summer and (b)winter. and the net radiationRnz in(a)summer and (b)winter. |

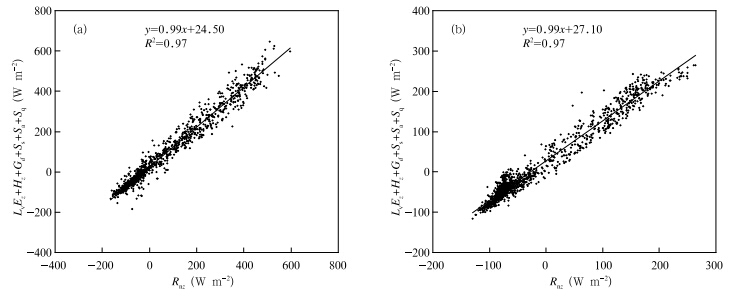

In the summer experiment(Fig. 5a), the linearregression between the 30-min averages of  0.99x + 24.50, with R2 = 0.97(N = 1252, P < 0.0001), implying animbalance of 1%. Thus, we conclude that considering the air enthalpy storage flux and the atmosphericmoisture change decreased the imbalance by 1%. Inthe winter experiment(Fig. 5b), the linear regressionbetween

0.99x + 24.50, with R2 = 0.97(N = 1252, P < 0.0001), implying animbalance of 1%. Thus, we conclude that considering the air enthalpy storage flux and the atmosphericmoisture change decreased the imbalance by 1%. Inthe winter experiment(Fig. 5b), the linear regressionbetween  0.99x + 27.10, with R2 = 0.97(N = 1385, P <0.0001), implying an imbalance of 1%. Thus, considering the air enthalpy storage flux and the atmosphericmoisture change has led to a reduction of the imbalance by 1%. For both seasons, a nearly perfect surfaceenergy balance was obtained by including in thecalculation the heat storage terms.

0.99x + 27.10, with R2 = 0.97(N = 1385, P <0.0001), implying an imbalance of 1%. Thus, considering the air enthalpy storage flux and the atmosphericmoisture change has led to a reduction of the imbalance by 1%. For both seasons, a nearly perfect surfaceenergy balance was obtained by including in thecalculation the heat storage terms.

|

Fig. 5. Scattergram of 30-min averages of the sum of energy °ux densities  and the netradiation Rnz in(a)summer and (b)winter. and the netradiation Rnz in(a)summer and (b)winter. |

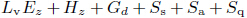

For better insight into the importance of the various heat storage terms, the percentage improvementby the various heat storage terms to the energy budgetclosure is presented in Table 2. The soil heat storageterm Ss made the highest contribution with improvements of about 6% in summer and 13% in winter, the air enthalpy storage term Sa about 0.6% in summer and 1% in winter, and the atmospheric moisturechange Sq 0.4% in summer and 0.0% in winter. Themain heat storage terms(the soil heat storage)playeda more important role in winter than in summer.

|

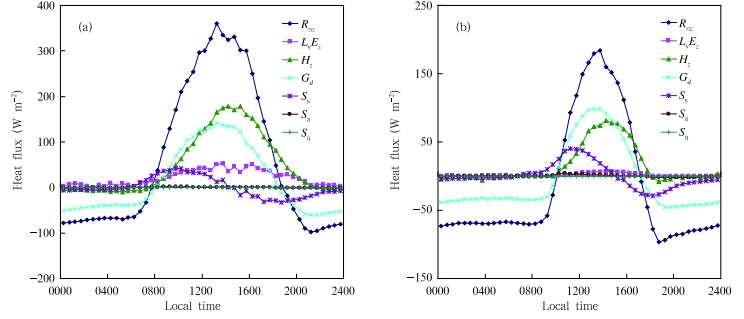

There is thin vegetation cover on the Gobi Desertin Northwest China, and so solar radiation easilyreaches the soil surface and directly heats it. Moreover, atmospheric moisture changes in the arid climateare very small. These physical processes mean that thesoil heat storage term has the highest contribution tothe energy budget closure and the contribution of theheat storage term above ground to the energy balanceshould be very small. This is confirmed in Table 2.The incoming shortwave radiation flux was less in winter than in summer due to the movement of the sun, thus, the vertical turbulence and the net radiation fluxwere also smaller in winter(Figs. 2 and 6). Owing tothe energy supply from deep soil in winter, the soilheat storage fluxes for both seasons were almost thesame(Fig. 6). The results show that the proportion ofthe soil heat storage terms in the total surface energyis larger in winter. Hence, the movement of the sun and the energy supply from the deep soil may lead togreater improvements via the main storage terms inthe energy budget closure for the winter.

|

| Fig. 6. Diurnal variation of net radiation(Rnz), latent heat(LvEz), sensible heat(Hz), soil heat flux(Gd), and theheat storage terms(Ss, Sa, and Sq)during(a)summer and (b)winter experiments. |

Over an ideal horizontal surface, the energy budget should achieve closure in theory, whereas in recentdecades most experiments and CO2 flux networks havefound a global closure of the surface energy balance ofabout 80%(e.g., Tsvang et al., 1991; Kanemasu et al., 1992; Aubinet et al., 2000; Wilson et al., 2002;Kanda et al., 2004; Foken et al., 2006; Cava et al., 2008; Jacobs et al., 2008; Michiles and Gielow, 2008).Heusinkveld et al.(2004)obtained a nearly perfectclosed energy budget by using harmonic analysis technique in estimating surface soil heat flux in the drydesert ecosystem in Nizzana, Israel. In the presentstudy, we also obtained a nearly perfect result of energy closure by directly measuring the soil heat flux ata depth of 2 cm and estimating the storage terms in theGobi Desert in Northwest China. This demonstratesthat the Gobi Desert is an ideal horizontal surface and the energy budget of an ideal horizontal surface canachieve closure. With solar radiation directly heating the soil, soil heat storage as an independent termcontributing to the surface energy closure cannot beneglected for this location.

It is interesting that we achieved similar and perfect closures in winter and summer although the contributions of the storage terms differed in the two seasons. By keeping the same measurement site and instruments, the similar excellent closure rate in the twoseasons may indicate that the energy budget closure ofan ideal horizontal surface does not vary with season, and the errors of energy storages related to vegetation(including the photosynthesis flux, the vegetation, and the canopy dew water enthalpy)can be neglected.5. Conclusions

Based on both summer and winter experiments, we studied the energy budget closure over the GobiDesert in Northwest China and evaluated the contribution of the heat storage terms to the energy balancein summer and winter respectively. The main conclusions are drawn as follows:

(1)There was an imbalance of 8% and 15%, respectively, in summer and winter when the heatstorage terms were not considered. The imbalance ofthe surface energy in winter was nearly twice of thatin summer.

(2)For both seasons, a nearly perfect result ofthe surface energy balance closure(99%)was obtainedby inclusion of the estimates of heat storage terms.

(3)The soil heat storage term made the highestcontribution to the energy balance closure with improvements of about 6% in summer and 13% in winter, and the air enthalpy storage term of about 0.6% insummer and 1% in winter. The contribution from theatmospheric moisture change was an improvement ofabout 0.4% in summer and could be ignored in winterin the present study.

(4)The energy budget closure of the ideal horizontal Gobi Desert surface in Northwest China didnot vary with the seasons.

| [1] | Aubinet, M., A. Grelle, A. Ibrom, et al., 2000: Estimates of the annual net carbon and water exchange of forests: The EUROFLUX methodology. Adv. Ecol. Res., 30, 113-175. |

| [2] | Braud, I., J. Noilhan, J. Bessemoulin, et al., 1993: Bareground surface heat and water exchanges under dry conditions. Bound.-Layer Meteor., 66, 173-200. |

| [3] | Cava, D., D. Contini, A. Donateo, et al., 2008: Analysis of short-term closure of the surface energy balance above short vegetation. Agric. For. Meteor., 148, 82-93. |

| [4] | Du Yang, Chen Xiaofei, Zhang Yulong, et al., 2004: Reliability of calibration curves measured by TDR in frozen soils verified by NMR. J. Glaciology and Geocryology, 26(6), 642-655. (in Chinese) |

| [5] | Finnigan, J. J., R. Clement, Y. Malhi, et al., 2003: A re-evaluation of long-term measurement techniques. Part I: Averaging and coordinate rotation. Bound. Layer Meteor., 107, 1-48. |

| [6] | Foken, T., and B. Wichura, 1996: Tools for quality assessment of surface-based flux measurements. Agric. For. Meteor., 78, 83-105. |

| [7] | --, F. Wimmer, M. Mauder, et al., 2006: Some aspects of the energy balance closure problem. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss, 6, 4395-4402. |

| [8] | Gao, Z., G. T. Chen, and Y. Hu, 2007: Impact of soil vertical water movement on the energy balance of different land surfaces. Int. J. Biometeor., 51, 565-573. |

| [9] | Heusinkveld, B. G., A. F. G. Jacobs, A. A. M. Holtslag, et al., 2004: Surface energy balance closure in an arid region: Role of soil and heat flux. Agric. For. Meteor., 122, 21-37. |

| [10] | Hiller, R., M. J. Zeeman, and W. Eugster, 2008: Eddycovariance flux measurements in the complex terrain of an Alpine Valley in Switzerland. Bound.-Layer Meteor., 127, 449-467. |

| [11] | Jacobs, A. F. G., B. G. Heusinkveld, and A. A. M. Holtslag, 2008: Towards closing the surface energy budget of a midlatitude grassland. Bound.-Layer Meteor., 126, 125-136. |

| [12] | Kanda, M., A. Inagaki, M. O. Letzel, et al., 2004: LES study of the energy imbalance problem with eddy covariance fluxes. Bound.-Layer Meteor., 110, 381-404. |

| [13] | Kanemasu, E. T., S. B. Verma, E. A. Smith, et al., 1992: Surface flux measurements in FIFE-An overview. J. Geophys. Res., 97, 18547-18555. |

| [14] | Kohsiek, W., C. Liebethal, T. Foken, et al., 2007: The energy balance experiment EBEX-2000. Part III: Behaviour and quality of the radiation measurements. Bound.-Layer Meteor., 123, 55-75. |

| [15] | Li Huixing, Xia Ziqiang, and Ma Guanghui, 2007: Effects of water content variation on soil temperature process and water exchange. J. Hohai University (Natural Science), 35(2), 172-175. (in Chinese) |

| [16] | Ma, Y., S. Fan, H. Ishikawa, et al., 2005: Diurnal and inter-monthly variation of land surface heat fluxes over the central Tibetan Plateau area. Theor. Appl. Climatol., 80, 259-273. |

| [17] | Mauder, M., S. P. Oncley, R. Vogt, et al., 2007: The energy balance experiment EBEX-2000. Part II: Intercomparison of eddy-covariance sensors and postfield data processing methods. Bound.-Layer Meteor., 123, 29-54. |

| [18] | --, R. L. Desjardins, E. Pattey, et al., 2008: Measurement of the sensible eddy heat flux based on spatial averaging of continuous ground-based observation, Bound. -Layer Meteor., 128, 151-172. |

| [19] | Meyers, T. P., and S. E. Hollinger, 2004: An assessment of storage terms in the surface energy balance of maize and soybean. Agric. For. Meteor., 125, 105-115. |

| [20] | Michiles, A., and R. Gielow, 2008: Above-ground thermal energy storage rates, trunk heat fluxes and surface energy balance in a central Amazonian rainforest. Agric. For. Meteor., doi: 10.1016/j.agrformet.2008.01.001. |

| [21] | Oncley, S. P., T. Foken, R. Vogt, et al., 2007: The energy balance experiment EBEX-2000. Part I: Overview and energy balance. Bound.-Layer Meteor., 123, 1-28. |

| [22] | Philip, H. S., 2006: Flux flummoxed: A proposal for consistent usage. Ground Water, 44(2), 125-128. |

| [23] | Sakai, R. K., D. Fitzjarrald, and K. E. Moore, 2001: Importance of low-frequency contributions to eddy fluxes observed over rough surfaces. J. Appl. Meteor., 40, 2178-2192. |

| [24] | Schmid, H. P., 1997: Experimental design for flux measurements: Matching scales of observations and fluxes. Agric. For. Meteor., 87, 179-200. |

| [25] | Steinfeild, G., M. O. Letzel, S. Raasch, et al., 2007: Spatial representativeness of single tower measurements and the imbalance problem with eddy-covariance fluxes: Results of a large-eddy simulation study. Bound.-Layer Meteor., 123, 77-98. |

| [26] | Sturman, A. P., and H. A. McGowan, 2009: Observations of dry season surface energy exchanges over a desert clay pan, Queensland, Australia. J. Arid Environ., 73, 74-81. |

| [27] | Tsvang, L. R., M. M. Fedorov, B. A. Kader, et al., 1991: Turbulent exchange over a surface with chessboardtype inhomogeneities. Bound.-Layer Meteor., 55, 141-160. |

| [28] | Twine, T. E., W. P. Kustas, J. M. Norman, et al., 2000: Correcting eddy-covariance flux underestimates over a grassland. Agric. For. Meteor., 103, 279-300. |

| [29] | Wang, H. L., Y. T. Gan, R. Y. Wang, et al., 2008: Phenological trends in winter wheat and spring cotton in response to climate changes in Northwest China. Agric. For. Meteor., 148, 1242-1251. |

| [30] | Wang Jieming, Wang Weizheng, Liu Shaoming, et al., 2009: The problems of surface energy balance closure: An overview and case study. Adv. Earth Sci., 24, 705-713. (in Chinese) |

| [31] | Wang Runyuan and Zhang Qiang, 2011: An assessment of storage terms in the surface energy balance of a subalpine meadow in Northwest China. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 28(3), 691-698. |

| [32] | --, --, Wang Yaolin, et al., 2004: Response of corn to climate warming in arid areas in Northwest China. Acta Bot. Sin., 46, 1387-1392. |

| [33] | Wilson, K. B., A. Goldstein, E. Falge, et al., 2002: Energy balance closure at FLUXNET sites. Agric. For. Meteor., 113, 223-243. |

| [34] | Xue, X., T. Wang, Q. W. Sun, et al., 2002: Field and wind-tunnel studies of aerodynamic roughness length. Bound.-Layer Meteor., 104, 151-163. |

| [35] | Yamanaka, T., I. Kaihotsu, D. Oyunbaatar, et al., 2007: Summertime soil hydrological cycle and surface energy balance on the Mongolian steppe. J. Arid Environ., 69, 65-79. |

| [36] | Yue Ping, Zhang Qiang, Niu Shengjie, et al., 2011: Effects of the soil heat flux estimates on surface energy balance closure over a semi-arid grassland. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 25(6), 774-782. |

| [37] | Zhang Qiang, Wei Guoan, Wang Sheng, et al., 2003: Vertical change of the soil structure parameters and the soil thermodynamic parameters in the Gobi deserts in arid areas. Arid Zone Res., 20, 44-52. (in Chinese) |

| [38] | --, and Huang Ronghui, 2004. Parameters of landsurface processes for Gobi in Northwest China. Bound.-Layer Meteor., 110, 471-478. |

| [39] | --, Wang Sheng, Wen Xiaomei, et al., 2011: Experimental study of the imbalance of water budget over the Loess Plateau of China. Acta Meteor. Sinica, 25(6), 765-773. |

2012, Vol. 26

2012, Vol. 26