2. 江苏省农业科学院 农业部农产品质量安全控制技术与标准重点实验室, 南京 210014

2. Key Laboratory of Control Technology and Standard for Agro-Product Safety and Quality, Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Science, Nanjing 210014, China

为明确农产品中残留农药对人体健康的负面影响,对其进行暴露分析以及潜在慢性风险评估是非常必要的。我国于2009年公布实行的《食品安全法》中,对建立食品安全监测与评估制度提出了明确要求。开发更准确、更详尽的化合物风险评估新方法已成为国际趋势,其中对我国相关领域影响最为显著的是生理毒物代谢动力学(PBTK)模型的引入[1]。PBTK模型可预测多种条件下化合物在人体及其他动物体内的吸收、扩散、代谢和排泄过程,将其应用于风险评估中可以大大降低结果的不确定性[2],同时,该模型与美国国家研究委员会(NRC)所推荐的发展使用体外方法代替活体毒性试验方法的理念相吻合[3],因此具有不可低估的发展潜力[4]。欧洲食品安全局(EFSA)出版的《化学物质联合机制风险评估意见》[5]中认为:PBTK模型适用于化合物的风险评估,并且是目前最精确的模型。有关PBTK模型在医药开发及应用领域的研究报道较多[3],但关于其在农药领域应用的研究较少,目前仅有关于毒死蜱(chlorpyrifos)[6]、三唑酮(triadimefon)[7]、莠去津(atrazine)[8]及二嗪磷(diazinon)[9]的PBTK模型的报道。本研究拟建立大鼠经口摄入敌敌畏后的PBTK模型,并采用欧拉数值计算法进行模拟与验证,以期为评估敌敌畏的饮食暴露风险提供依据。

1 材料和方法 1.1 模型框架

本研究主要关注大鼠经口摄入敌敌畏后药剂在体内分布、吸收和代谢的过程,不考虑呼吸和皮肤接触暴露途径。所建立的PBTK模型将相应的组织器官作为单独房室看待,房室间借助血液循环相连,设定药剂在各房室间的转运和转化遵循质量守恒定律。根据相关毒理学资料[10],经口摄入敌敌畏的PBTK模型可分为4个房室:肝脏、充分灌注室(包括小肠、大肠、脾脏、大脑)、不充分灌注室(包括肌肉、皮肤、脂肪、骨头)和肾脏。血液中乙酰胆碱酯酶动力学机制模型中,自由及被抑制乙酰胆碱酯酶同样遵循质量守恒定律。具体如图 1所示。

| 图 1 敌敌畏经口摄入后在大鼠体内分布代谢的PBTK模型Fig. 1 The PBTK modle of dichlorvos in rattus norregicus following oral ingestion |

假设敌敌畏只在肝脏和肾脏中发生代谢,依据各房室的血流速率、敌敌畏在房室内的组织/血液分配系数和房室所占有的组织体积,可建立每一房室内敌敌畏浓度变化率的微分方程[11]。

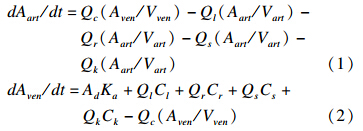

动脉血和静脉血中敌敌畏含量的计算方程为:

其中:Ad—每千克体重经口摄入的敌敌畏的质量(mg);Aart—动脉血中敌敌畏质量(mg);Aven—静脉血中敌敌畏质量(mg);Ka —吸收速率(h-1);Vart —动脉血体积(L);Vven —静脉血体积(L);Qc —心脏输出血流量(L/h);Ql—肝脏血流量(L/h);Qr —充分灌注室血流量(L/h);Qs —不充分灌注室血流量(L/h);Qk —肾脏血流量(L/h);Cl—肝脏中敌敌畏浓度(mg/kg);Cr—充分灌注室中敌敌畏浓度(mg/kg);Cs—不充分灌注室中敌敌畏浓度(mg/kg);Ck—肾脏中敌敌畏浓度(mg/kg)。

充分灌注室以及不充分灌注室中敌敌畏质量的计算方程为:

肝脏和肾脏中敌敌畏质量的计算方程为:

其中 Ai—各房室中敌敌畏质量(mg);Qi—各房室中血流量(L/h);Vi—各房室体积(L);Pi—各房室的组织/血液分配系数;Kmi—房室中敌敌畏代谢速率(h-1)。

自由以及被抑制乙酰胆碱酯酶含量的计算方程为:

模型模拟所用的大鼠生理参数见表 1。其中,体重及各组织血流量数据来自文献[12];各组织体积数据来自文献[13];敌敌畏在大鼠体内的组织/血液分配系数根据文献[14]中的方法计算得到。

|

|

表 1 大鼠生理参数以及敌敌畏在其体内的组织/血液分配系数 Table 1 Physiological parameter and partition coefficients of tissues/blood for dichlorvos in R.norregicus |

模型模拟所需敌敌畏在大鼠体内代谢及生化反应常数见表 2。其中,酶合成速率和降解速率参照文献[15]中数值计算得到;酶抑制速率常数来自文献[16];酶再生速率常数来自文献[17];肝、肾代谢速率以及吸收速率由文献[18]中数值计算得到。 1.4 模型模拟与验证

采用欧拉数值法,借助Excel电子表格对模型求解[19],并将其与相关的实验测量值进行比较,验证方法的可靠性。欧拉数值法是一阶数值方法,对于一阶微分方程,认为时间t时方程的解近似等于t-Δt时方程的解加上微分方程的斜率与步长(Δt)的 乘积,是解决数值常微分方程的一类显形方法。根据该方法,可以计算出不用时间下各房室中敌敌畏的浓度以及血液中乙酰胆碱酯酶活性的变化。

|

|

表 2 敌敌畏在大鼠体内代谢及生化反应常数(n=3) Table 2 Metabolic and biochemical reaction constants for dichlorvos in R.norregicus |

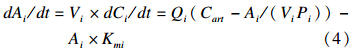

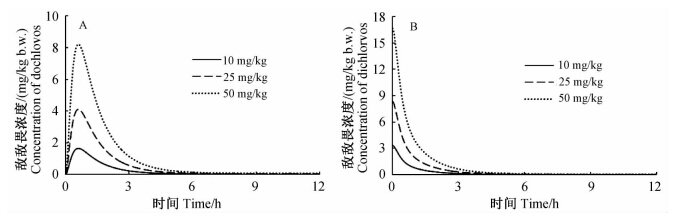

分别对大鼠经口摄入10、25 和50 mg/kg b.w.敌敌畏后在肝脏、血液中的毒物代谢动力学进行了模拟,步长为0.004 h。图 2(A)为肝脏中敌敌畏浓度变化模拟曲线,当经口摄入不同剂量敌敌畏0.6 h后,其在肝脏中的浓度均达到最高,随后下降;图 2(B)为血液中敌敌畏浓度变化的模拟曲线,由于该模拟曲线是以大鼠经口摄入敌敌畏后瞬间在血液中分布达到平衡这一假设为前提的,因此该曲线与实际相比具有一定的前延性,即经口摄入敌敌畏后初期血液中敌敌畏浓度有一个增加的过程,继而达到最高,随后下降;图 3为大鼠经口摄入5、10 和25 mg/kg b.w.敌敌畏后血液中乙酰胆碱酯酶活性变化模拟曲线,不同摄入量情况下,乙酰胆碱酯酶活性下降到最低所需的时间不同,分别为0.06、0.116和0.164 h,随后活性开始回升。大鼠经口摄入25 mg/kg b.w.敌敌畏后血液中乙酰胆碱酯酶活性抑制率最高(94%),抑制作用显著。

| 图 2 大鼠经口摄入不同剂量敌敌畏后其在肝脏(A)及血液(B)中浓度变化模拟曲线Fig. 2 Simulation of dichlorvos changing curve in R.norregicus liver(A) and blood(B) following different concentration of oral ingestion |

| 图 3 大鼠经口摄入不同剂量敌敌畏后血液中乙酰胆碱酯酶活性变化模拟曲线Fig. 3 Simulation of blood AChE activity changing curve in R.norregicus following oral ingestion of different concentration of dichlorvos |

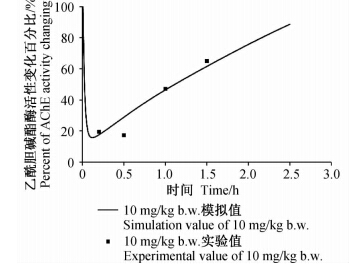

将模型模拟所得敌敌畏在大鼠体内的毒物代谢动力学数据与前人的实测数据进行比较,以验证模型和求解方法的准确性。袁丽等[20]实际测量了大鼠经35 mg/kg b.w.敌敌畏灌胃后不同时间其在血液中的浓度,Hinz等[21]研究了大鼠经口摄入10 mg/kg b.w.敌敌畏后血液中乙酰胆碱酯酶活性变化情况。本研究模型模拟结果与上述实验数据的比较见图 4和图 5,其中,血液中敌敌畏浓度和乙酰胆碱酯酶活性的实验测量值与模拟值经方差分析,P>0.05,差异均不显著,由此可以认为,本研究采用模型模拟方法得到的结果与实验测量结果相符。

| 图 4 大鼠经口摄入敌敌畏后其在血液中浓度 变化的实验值与模拟值对比Fig. 4 Experimental data and simulation value of dichlorvos concentration in R.norregicus blood following oral ingest ingest |

| 图 5 大鼠经口摄入敌敌畏后血液中乙酰胆碱酯 酶活性变化的实验值与模拟值对比Fig. 5 Experimental data and simulation value of blood AChE activity in R.norregicus following dichlorvos oral ingest |

敌敌畏属有机磷类杀虫剂,其作用靶标为昆虫乙酰胆碱酯酶,对实验动物具有迟发性神经毒性、生殖毒性及致畸、致癌等多种作用[10]。人群对敌敌畏的非职业暴露途径主要为饮食暴露。由于毒理学实验条件要求严格、实验动物使用有限,虽然已有一系列关于敌敌畏对大鼠的毒理学研究资料[22,23,24,25],但大部分以高剂量暴露为主,在用于评估实际暴露风险时具有很大的局限性。PBTK模型基于毒物代谢动力学机制开展毒理学研究,具有明显的优势,在低剂量暴露情形下优势尤为突出[26]。尽管该模型需要一定的实验数据来建立、优化和验证,但一旦建成,低剂量-反应曲线即可由模型模拟得到。

目前一般通过相关软件编程来求解PBTK模型中的质量守恒微分方程,例如ACSL、Berkeley Madonna和Matlab[27]等。本研究未使用相关软件,而是利用欧拉数值法求解PBTK方程组,不需昂贵模拟软件,且不需编程,是一种简便、易学且经济的方法。但需注意到,当欧拉数值法的步数增多时,其误差会因积累而增大,因此不适用于代谢缓慢的化合物的PBTK模型模拟。

利用PBTK模型可以较好地模拟大鼠经口摄入敌敌畏后的体内代谢动力学过程,获得组织、血液中敌敌畏浓度变化以及血液中乙酰胆碱酯酶活性变化等内剂量(deliverated dose)数据,为进一步评估人群的敌敌畏暴露风险提供了有效途径。

| [1] | Teuschler L K. Deciding which chemical mixtures risk assessment methods work best for what mixtures [J]. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2007, 223(2): 139-147. |

| [2] | Reffstrup T K, Larsen J C, Meyer O. Risk assessment of mixtures of pesticides: current approaches and future strategies [J]. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol, 2010, 56(2): 174-192. |

| [3] | Andersen M E, Krewski D. Toxicity testing in the 21st century: bringing the vision to life [J]. Toxicol Sci, 2009, 107(2): 324-330. |

| [4] | Punt A, Schiffelers M W A, Jean Horbach G, et al. Evaluation of research activities and research needs to increase the impact and applicability of alternative testing strategies in risk assessment practice [J]. Regul Toxicol Pharm, 2011, 61(1): 105-114. |

| [5] | EFSA. Scientific opinion of the PPR panel on a request from the EFSA evaluate the suitability of existing methodologies and, if appropriate, the identification of new approaches to assess cumulative and synergistic risks from pesticides to human health with a view to set MRLs for those pesticides in the frame of regulation, EC 396/2005 [R]. 2005-03-10. |

| [6] | Smith J N, Hinderliter P M, Timchalk C, et al. A human life-stage physiologically based pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic model for chlorpyrifos: development and validation [J/OL]. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol, 2014, 69(3): 580-597. [2014-07-08]. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.yrtph.2013.10.005 |

| [7] | Crowell S R, HendersonW M, KennekeJ F, et al. Development and application of a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for triadimefon and its metabolite triadimenol in rats and humans [J]. Toxicol Lett, 2011, 205(2): 154-162. |

| [8] | Lin Zhoumeng, Fisher J W, Ross M K, et al. A physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for atrazine and its main metabolites in the adult male C57BL/6 mouse [J]. Toxicol Appl Pharm, 2011, 251(1): 16-31. |

| [9] | Poet T S, Kousba A A, Dennison S L, et al. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic model for the organophosphorus pesticide diazinon [J]. Neuro Toxicol, 2004, 25(6): 1013-1030. |

| [10] | Research T I. Toxicological Profile for Dichlorvos [M]. US: Department of Health and Human Sevices, 1997: 66-80. |

| [11] | Office of Prevention, Pesticides and Toxic Substances(OPPTS). Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling: Preliminary Evaluation and Case Study for the N-Methyl Carbamate Pesticides [M]. Washington D.C: US Environmental Protection Agency, 2003: 11-16. |

| [12] | Brown R P, Delp M D, Lindstedt S L, et al. Physiological parameter values for physiologically based pharmacokinetic models [J]. Toxicol Ind Health, 1997, 13(4): 407-484. |

| [13] | Davies B, Morris T. Physiological parameters in laboratory animals and humans [J]. Pharmaceut Res, 1993, 10(7): 1093-1096. |

| [14] | Poulin P, Krishnan K. Molecular structure-based prediction of the partition coefficients of organic chemicals for physiological pharmacokinetic models [J]. Toxicol Methods, 1996, 6(3): 117-137. |

| [15] | Traina M E, Serpietri L A. Changes in the levels and forms of rat Plasma cholinesterases during chronic diisopropyl-phosphorofluoridate intoxication [J]. Biochem Pharmacol, 1984, 33(4): 645-649. |

| [16] | Maxwell D M. The specificity of carboxylesterase protection against the toxicity of organophosphorus compounds [J]. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 1992, 114(2): 306-312. |

| [17] | Reiner E, Pletina R. Regeneration of cholinesterase activities in humans and rats after inhibition by O,O-dimethyl-2,2-dichlorovinyl phosphate [J]. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 1979, 49(3): 451-454. |

| [18] | Casida J E, Mcbride L, Niedermeier R P. Metabolism of 2,2-dichlorovinyl dimethyl phosphate in relation to residues in milk and mammalian tissues [J]. J Agric Food Chem, 1962, 10(5): 370-377. |

| [19] | Meineke I, Brockmöller J. Simulation of complex pharmacokinetic models in Microsoft Excel [J]. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 2007, 88(3): 239-245. |

| [20] | 袁丽, 王娜娜, 代恒, 等. 多次活性炭灌胃对大鼠血浆敌敌畏浓度的影响 [J]. 中华急诊医学杂志, 2010, 19(6): 606-670. Yuan Li, Wang Nana, Dai Heng, et al. Therapeutic effects of multi-dose activated charcoal on the acute dichlorvos poisoning in rats [J]. Chin J Emerg Med, 2010, 19(6): 606-670.(in Chinese) |

| [21] | Hinz V, Grewig S, Schmidt B H. Metrifonate and dichlorvos: effects of a single oral administration on cholinesterase activity in rat brain and blood [J]. Neurochem Res, 1996, 21(3): 339-345. |

| [22] | Po C C. NTP technical report on the toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of dichlorvos [R]. CAS no. 62-73-7. US: Department of Health and Human Services, 1989. |

| [23] | Duarte T, Martin C, Baud F J, et al. Follow up studies on the respiratory pattern and total cholinesterase activities in dichlorvos-poisoned rats [J]. Toxicoly Lett, 2012, 213(2): 142-150. |

| [24] | Wani W Y, Gudup S, Sunkaria A, et al. Protective efficacy of mitochondrial targeted antioxidant MitoQ against dichlorvos induced oxidative stress and cell death in rat brain [J]. Neuropharmacology, 2011, 61(8): 1193-1201. |

| [25] | Mircioiu C, Victor A V, Ionescu M, et al. Evaluation of in vitro absorption, decontamination and desorption of organophosphorous compounds from skin and synthetic membranes [J]. Toxicol Lett, 2013, 219(2): 99-106. |

| [26] | Bessems J G, Loizou G, Krishnan K, et al. PBTK modelling platforms and parameter estimation tools to enable animal-free risk assessment: ecommendations from a joint EPAA-EURL ECVAM ADME workshop [J]. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol, 2014, 68(1): 119-139. |

| [27] | Mumtaz M, Fisher J, Blount B, et al. Application of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models in chemical risk assessment [J]. J Toxicol, 2012, 2012(9): 1155-2012. |

2015, Vol.

2015, Vol.