文章信息

- 张俊杰, 柴胜丰, 韦霄, 吕仕洪, 吴少华

- Zhang Junjie, Chai Shengfeng, Wei Xiao, Lv Shihong, Wu Shaohua

- 珍稀濒危植物金丝李种子的萌发特性

- Germination Characteristics of the Seed of a Rare and Endangered Plant, Garcinia paucinervis

- 林业科学, 2018, 54(4): 174-185.

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2018, 54(4): 174-185.

- DOI: 10.11707/j.1001-7488.20180420

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2017-11-10

- 修回日期:2018-01-12

-

作者相关文章

2. 广西壮族自治区中国科学院广西植物研究所 桂林 541006

2. Guangxi Institute of Botany, Guangxi Zhuangzu Autonomous Region and Chinese Academy of Sciences Guilin 541006

金丝李(Garcinia paucinervis)为藤黄科(Guttiferae)藤黄属(Garcinia)乔木,其木质坚硬、耐腐且抗虫蛀(Toure et al., 2010),主要分布于广西西部、南部和云南东南部海拔194~830 m、坡度较陡的石灰岩岩溶地貌山地上,为石山特有树种,其树形挺拔优美,枝叶光泽常绿、嫩叶鲜红,亦为优良的色叶观赏树种,是“广西五大硬木之一”。此外,金丝李作为传统壮药,其枝叶、树皮可入药,也可治疗烧伤、烫伤等(Liu et al., 2016)。由于金丝李生境脆弱,分布点有限且分散,天然更新困难(陈家庸等,1988),乱砍滥伐现象严重等,IUCN将其列为Endangered B1+2e级物种(Farm et al., 2003),是《中国珍稀濒危保护植物名录》(国家环境保护局等, 1987)中的二级重点保护植物和《中国植物红皮书》中的易危种(傅立国等, 1991),也被录入《广西壮族自治重点保护野生植物名录》。

目前,关于藤黄属植物种质收集和保存的研究较匮乏,对金丝李的繁殖研究更是鲜见报道。笔者课题组前期研究发现,金丝李无萌蘖现象且枝条扦插繁殖极其困难,推测有性生殖是其野外繁殖的主要途径。而在原生境中,金丝李大树和有结实的植株极少(张俊杰等, 2017),果实易被猴子采食且种子寿命短(傅立国, 1991),说明其种子资源非常有限。金丝李是北热带和南亚热带喀斯特地区的乡土树种,是石山地区植被恢复和城镇绿化的良好材料,但其基本属于野生状态,缺乏足够的苗木资源。种子萌发是植物种群天然更新的基础(李文良等, 2008)和多种内、外因素共同作用的结果(Wei et al., 2016),萌发情况潜在影响着植物种群的发展和群落的动态演替,萌发策略的成功与否决定着植物的生存和繁衍(Wei et al., 2008)。萌发阶段是植物生活史中对各种环境条件反应最为敏感的时期(Quero et al., 2008)和植物更新过程中的薄弱环节,是种群生活史中亏损最严重的时期之一(Burt-Smith et al., 2003),幼苗的自然更新速率不足以补充衰老的个体时,种群便会逐步走向灭亡。因此,了解濒危植物种子萌发特性可为研究其生态适应性、生活史对策和濒危机制奠定科学基础,为保护策略的制定提供科学依据。

金丝李种子用常规方法播种萌发十分缓慢,限制了其在生态恢复和园林绿化方面的应用(张俊杰等,2017)。本研究从可能影响金丝李种子萌发的生物学特性和生态因子出发,研究其萌发规律,旨在探讨珍稀濒危植物金丝李种子萌发的条件,分析其萌发过程中对石灰岩岩溶山地环境的适应性,推测其濒危机制和自然更新能力弱的原因,为金丝李的保护、引种驯化和高效种苗繁育及石山地区的森林重建、生态恢复提供理论支撑。

1 材料与方法 1.1 试验材料于2016年6月采集广西靖西市胡润镇(HR)(23°3′26″N,106°47′39″E)、安宁乡(AN)(22°54′13″N,106°16′11″E)和弄岗国家级自然保护区(NG)(22°27′58″N,106°57′18″E)3个天然种群成熟的金丝李果实,将其带回实验室先堆沤数天,搓洗掉果皮果肉,清水冲漂洗净种子备用。

1.2 种子形态特性观测及生活力测定采用烘干法测定NG种群的种子含水量(ISTA, 1996)。随机抽取50粒健康种子,用游标卡尺测定种子的大小,电子天平测量其质量。采用TTC法测定种子生活力(李合生等, 2000),每处理30粒种子,3个重复。

1.3 种子萌发特性测定选取无病虫害的种子,于2016年7月初播种。试验在LRH-250-G光照培养箱中进行,播种前种子经0.1%的K2MnO4溶液消毒30 min,清水洗净。播种容器为17.2 cm×11.7 cm×7 cm,容量1 000 mL的塑料盒,铺以4 cm厚经消毒的基质,播种深度为1 cm,每盒播10粒,每处理2盒,3个重复。以芽顶出沙层为种子萌发标准,观察到第1粒种子萌发后,每7天统计1次萌发数,试验时长为350天。除不同种群种子萌发试验采用3个种群的种子外,其余试验均采用NG种群的种子。除另有补充说明,以下处理均设定为25 ℃、周期性光照(3 000 lx,12 h ·d-1)、河沙为萌发基质的条件下进行,保持基质湿润。

1) 内果皮或种皮对种子萌发的影响以带内果皮种子、去种皮种子(用刀片划开剥除种皮)为试验材料,以去内果皮且带种皮的种子为对照进行试验。

2) 温度对种子萌发的影响分别设置培养箱温度为18、25、32和37 ℃,以及放置在室温环境(RT,夏季26~32 ℃,冬季8~15 ℃)5个温度处理做萌发试验。

3) 光照对种子萌发的影响设置持续光照(3 000 lx,24 h ·d-1)、持续黑暗(24 h ·d-1)和周期性光照(3 000 lx,12 h ·d-1)3种光照模式进行萌发试验。

4) 基质对种子萌发的影响分别以河沙、粘质壤土、泥炭土、石山土、珍珠岩和蛭石6种材料作为基质进行萌发试验。

5) 土壤含水量对种子萌发的影响以烘干至恒质量的300 g石山土为基质,加入蒸馏水,使其土壤含水量分别为20%、40%、60%和80%做萌发试验,每4天称量1次,补充蒸发的水分。

6) 不同播种深度种子萌发试验分别以石山土和河沙为基质,设置播种深度分别为0.5、3和5 cm(铺以6 cm厚的基质)进行试验。

7) 不同重量种子萌发试验将种子重量划分为<4 g、4~5 g和>5 g 3个质量等级作为萌发试验材料。

8) 不同种群对种子萌发的影响分别取NG、AN和HR3个不同种群种子作为萌发试验材料。

1.4 萌发指标的计算选用萌发时滞(germination time lag,GTL)、发芽势(germination energy,GE)、萌发率(germination percentage,GP)和平均萌发时间(mean germination time,MGT)4个参数评价种子活力。GTL (d),即萌发启动时间,指从萌发试验开始到第1粒种子开始萌发所用时间。GE (%) =规定时间种子发芽数/播种种子数×100%,试验限定为90天。GP (%) =萌发种子数/播种种子数×100%;MGT = ∑(ti×ni)/∑ni,式中ti为播种之日开始的第i天,ni为播种后第i天萌发的种子数。

1.5 幼苗生长参数测定萌发试验结束后,在不同温度、基质、质量和种群4个萌发试验处理中,分别随机抽取早期萌发的5株幼苗,剪掉留存的种子,洗净擦干,用电子天平、直尺、游标卡尺测量并记录地上和地下部分生物量、主根长和地径4个参数,其中生物量为在105 ℃烘箱中烘0.5 h后,65 ℃烘至恒质量。不同温度和种群处理测量幼苗株高。

1.6 种子再生能力测定2017年1月,取已萌发的金丝李种子,用已消毒的剪刀剪除留存在幼苗上的种子,在种子的伤口处涂抹新鲜草木灰,按照1.3方法进行种子再生萌发试验,252天后统计其萌发率。

1.7 数据统计分析采用Microsoft Excel 2010软件进行数据统计,采用SPSS19.0统计软件(One-Way ANOVA,Duncan post hoc test, P<0.05)进行不同处理间的多重比较分析。统计值以平均值±标准误(Mean±SE)表示。采用SigmaPlot 11.0软件绘图。

2 结果与分析 2.1 种子形态特征金丝李种子卵形至宽卵形,纵轴长(3.08±0.21) cm、直径(1.54±0.10) cm,种皮紧贴胚乳,胚包裹于较厚的胚乳层中,窄椭圆形,不易区分胚芽、胚轴和胚根。初始含水量为45.29%±0.72%,种子质量(4.57±0.69) g,生活力为95.56%±1.92%。种子萌发后留存在幼苗上。

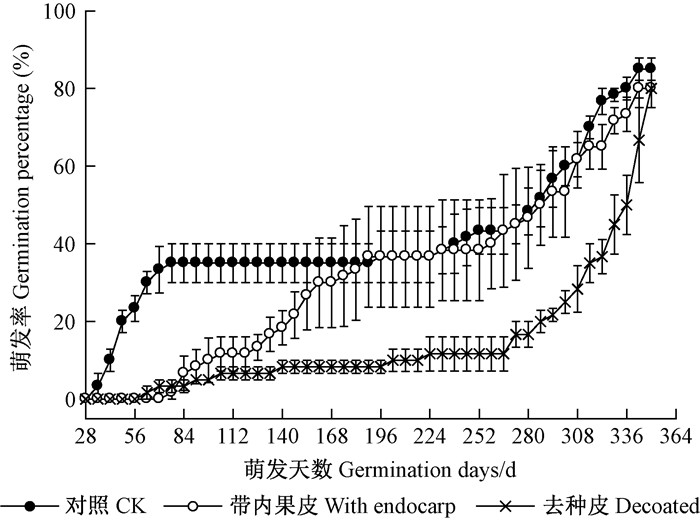

2.2 内果皮和种皮对种子萌发的影响图 1A显示,带内果皮种子与去种皮种子虽然在前期萌发率低于对照,但后期均萌发加快,最终3处理萌发率均大于80%,无显著性差异(表 1)。带内果皮与去种皮处理的萌发时滞显著长于对照(P < 0.05),而对照的发芽势达35.00%,显著高于带内果皮与去种皮处理。去种皮处理的平均萌发时间长达293.55天,显著长于对照和带内果皮处理,其萌发过程最缓慢。

|

图 1 带内果皮和去种皮金丝李种子的萌发动态 Figure 1 Germination processes of G. paucinervis seeds with endocarp and removed seed coats |

|

|

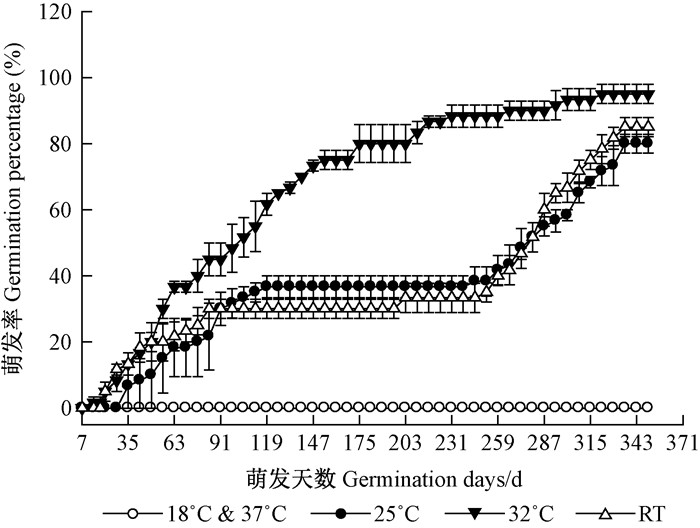

18 ℃条件下,金丝李种子至试验结束无萌发迹象,且有11.67%±2.89%的种子霉烂,37 ℃下也无种子萌发且完全腐烂。其他温度处理种子萌发情况如图 2A所示,32 ℃条件下播种63天萌发率便高于其他2个温度处理,25 ℃和室温下,119~238天时种子几乎停止萌发,而32 ℃下播种175天起萌发减缓,但无明显停滞阶段。25 ℃时种子的GTL分别比32 ℃和室温下显著滞后了21和18天。32 ℃条件下,种子的GE高达45.00%,其MGT(109.50天)比25 ℃和室温条件下显著缩短了43.46%和45.06%。而GP在3个温度间无显著性差异(表 1)。

|

图 2 不同温度情况金丝李种子的萌发动态 Figure 2 Germination process of G. paucinervis seeds in different temperatures |

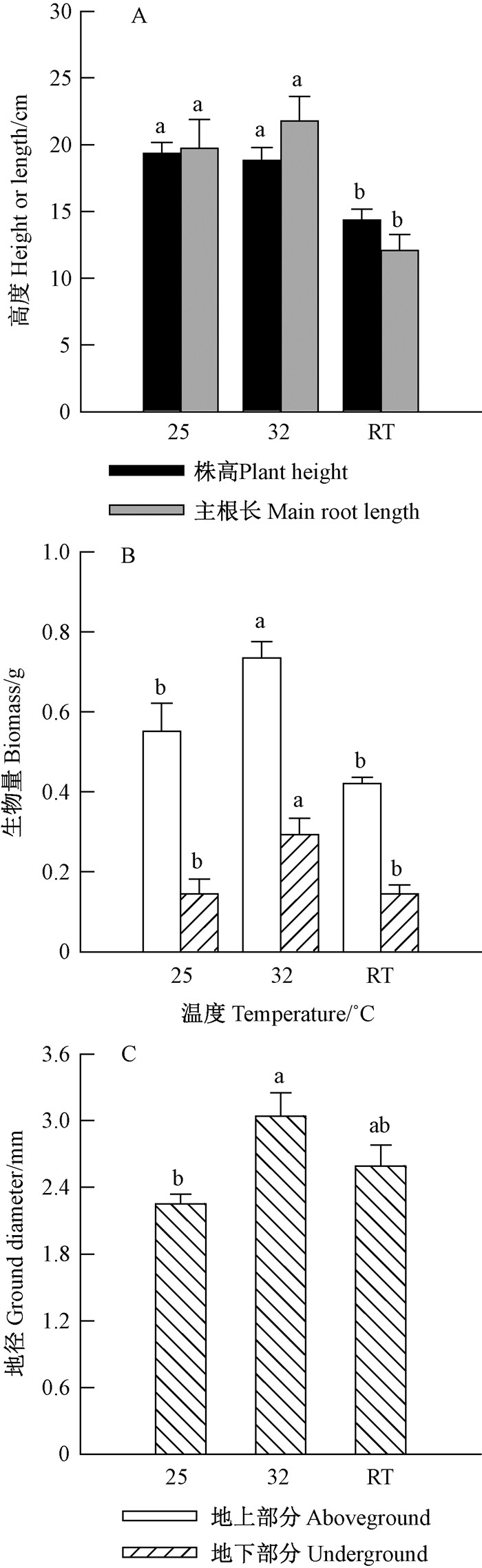

如图 3所示,金丝李幼苗在25 ℃和32 ℃下的株高和主根长显著大于室温条件处理。32 ℃时,金丝李地上和地下部分生物量显著大于其他2个温度处理,幼苗地径显著大于25 ℃处理,与室温处理差异不显著。因此,32 ℃下能显著加快其萌发进程和生长速度。

|

图 3 温度对金丝李幼苗生长的影响 Figure 3 Effects of temperatures on growth of G. paucinervis seedlings |

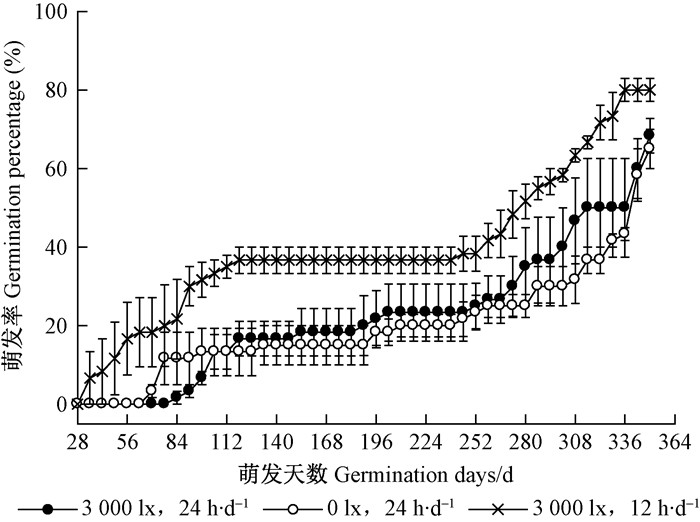

如图 4所示,周期性光照处理种子的萌发率始终高于持续光照和持续黑暗处理,试验结束后萌发率三者差异不显著(表 1)。周期性光照的GTL相比持续光照和持续黑暗处理显著提早了46和38天,其GE和MGT相比持续光照和持续黑暗处理显著提升或缩短。幼苗在周期性光照条件下长势良好,上胚轴由紫红转为绿色,成熟叶片深绿有光泽,但在持续光照条件下叶片发黄,持续黑暗条件下上胚轴伸长但不长叶,呈黄白色。因此,金丝李种子最适宜在周期性光照条件下萌发与生长。

|

图 4 不同光照条件下金丝李种子的萌发动态 Figure 4 Germination process of G.paucinervis seeds in different lights |

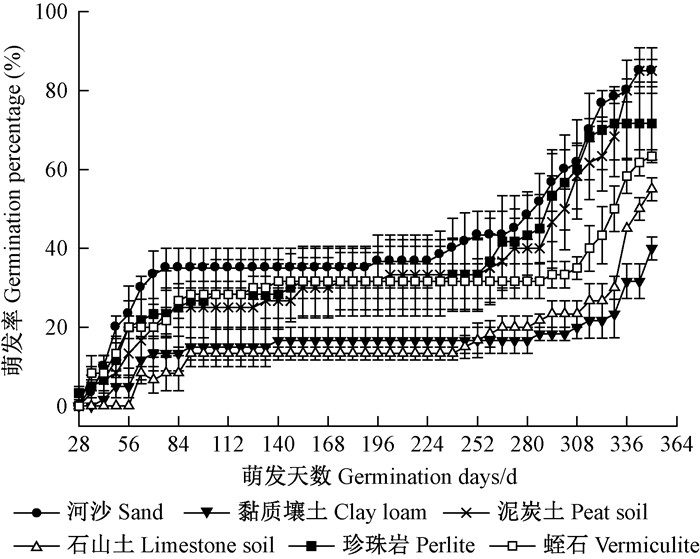

如图 5所示,6种不同基质下,金丝李种子在105~224天内萌发缓慢,后期萌发率增长较快。由表 1可知,GTL顺序为:石山土>黏质壤土>泥炭土>河沙>蛭石>珍珠岩,石山土的GTL显著长于除了黏质壤土之外的其他4种基质。以河沙为基质种子的GE与黏质壤土、石山土为基质相比差异显著。萌发率在不同的基质条件下为:河沙=泥炭土>珍珠岩>蛭石>石山土>黏质壤土。石山土的MGT最长,达254.93天,与河沙、珍珠岩和蛭石差异显著。试验结束后,黏质壤土的种子腐烂数占供试种子数的40.00%±5.00%。因此,以黏质壤土或石山土为基质金丝李种子的萌发会受到抑制。

|

图 5 不同基质中金丝李种子的萌发动态 Figure 5 Germination process of G.paucinervis seeds in different substrates |

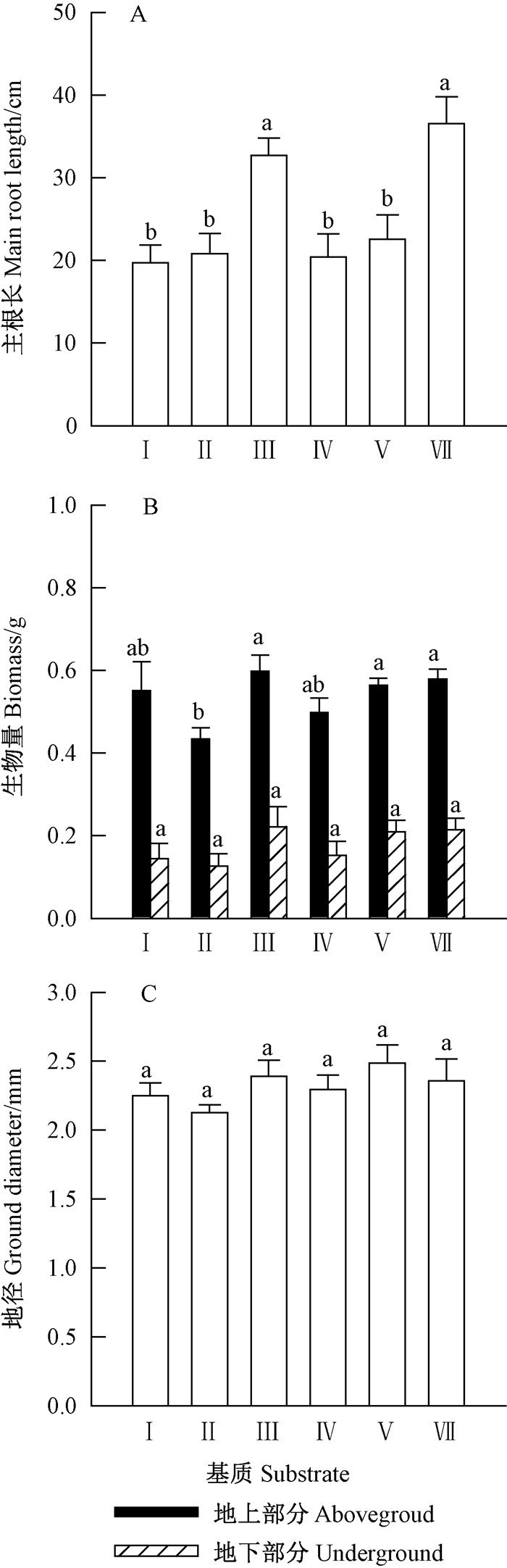

如图 6所示,在泥炭土和蛭石中,金丝李幼苗主根显著长于其他基质栽培的主根。对于金丝李幼苗地上部分生物量,除了黏质壤土较差外,在其余各基质中无显著性差异,地下部分生物量和地径在各基质间无显著差异。

|

图 6 栽培基质对金丝李幼苗生长的影响 Figure 6 Effects of different substrats on growth of G. paucinervis seedlings Ⅰ.河沙Sand;Ⅱ.粘质壤土Clay loam;Ⅲ.泥炭土Peat soil;Ⅳ.石山土Limestone soil;Ⅴ.珍珠岩Perlite;Ⅵ.蛭石Vermiculite. |

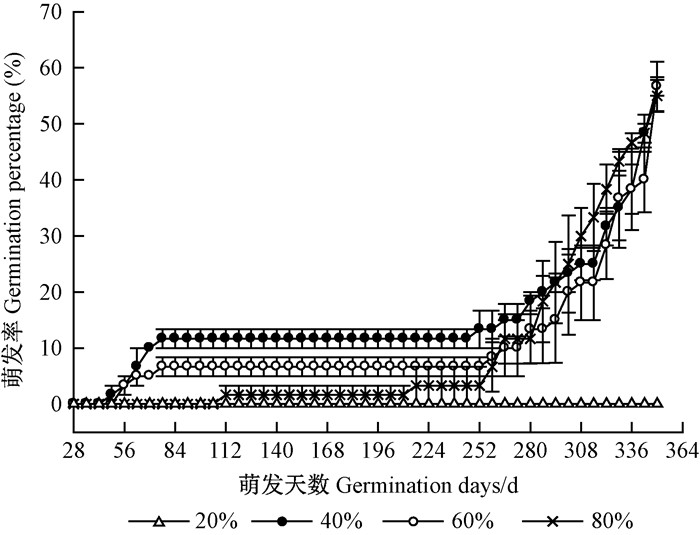

金丝李种子在土壤含水量为20%时,无萌发迹象,350天后该处理的种子经TTC法测定96.67%±2.87%均有活力。在其余含水量石山土的处理中,前259天萌发率均未超过15%,之后萌发速度加快,于350天达到55.00% ~56.67%(表 1)。当土壤含水量为80%时,GTL长达209天,相比40%和60%含水量下显著延长,且试验结束时该处理已有11.67%±2.89%的种子霉烂。3种含水量条件下GE差异显著且均低于12%,而GP与MGT 3处理间均无显著差异(图 7)。可见在石山土中,40% ~60%的含水量较适宜金丝李种子萌发。

|

图 7 不同土壤含水量下金丝李种子的萌发动态 Figure 7 Germination process of G. paucinervis seeds in different soil moistures |

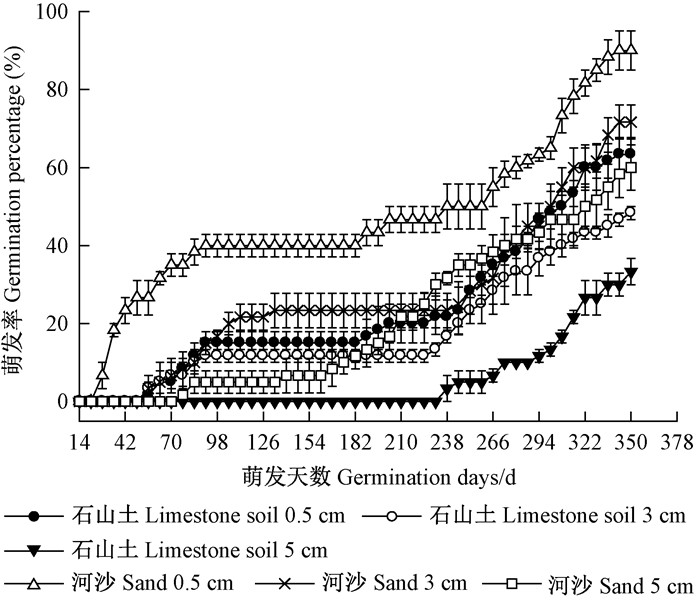

由图 8可知,在石山土和河沙基质中,随着埋深的增加GTL均延长,GE和GP均降低。在同等埋深情况下,以河沙为基质相比以石山土为基质,GTL缩短,GE和GP均较高,2种基质下同等埋深的GP差异显著。石山土为基质埋深5 cm的MGT显著长于其他各埋深处理,河沙埋深0.5 cm的MGT则显著低于其他各处理,表明河沙埋深0.5 cm的种子萌发速度最快、最整齐,而石山土埋深5 cm的萌发过程最缓慢。

|

图 8 不同播种深度下金丝李种子的萌发动态 Figure 8 Germination process of G. paucinervis seeds in different burial depths |

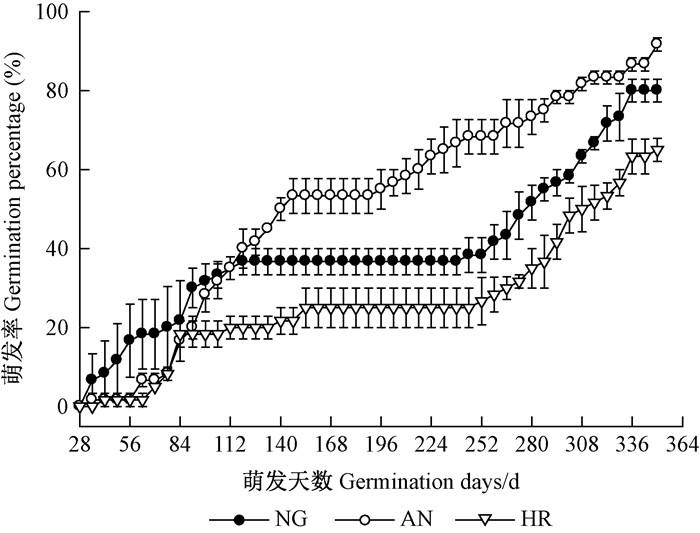

如图 9所示,在萌发过程中,AN种群种子的萌发停滞时间在3种群中较短,且最终萌发率AN>NG>HR,且差异显著(表 1)。GTL和GE在3种群间无显著差异,HR种群的MGT显著长于AN种群。总体来说,HR种群萌发率最低,萌发速度最慢。

|

图 9 不同种群金丝李种子的萌发动态 Figure 9 Germination process of G. paucinervis seeds in different polulations |

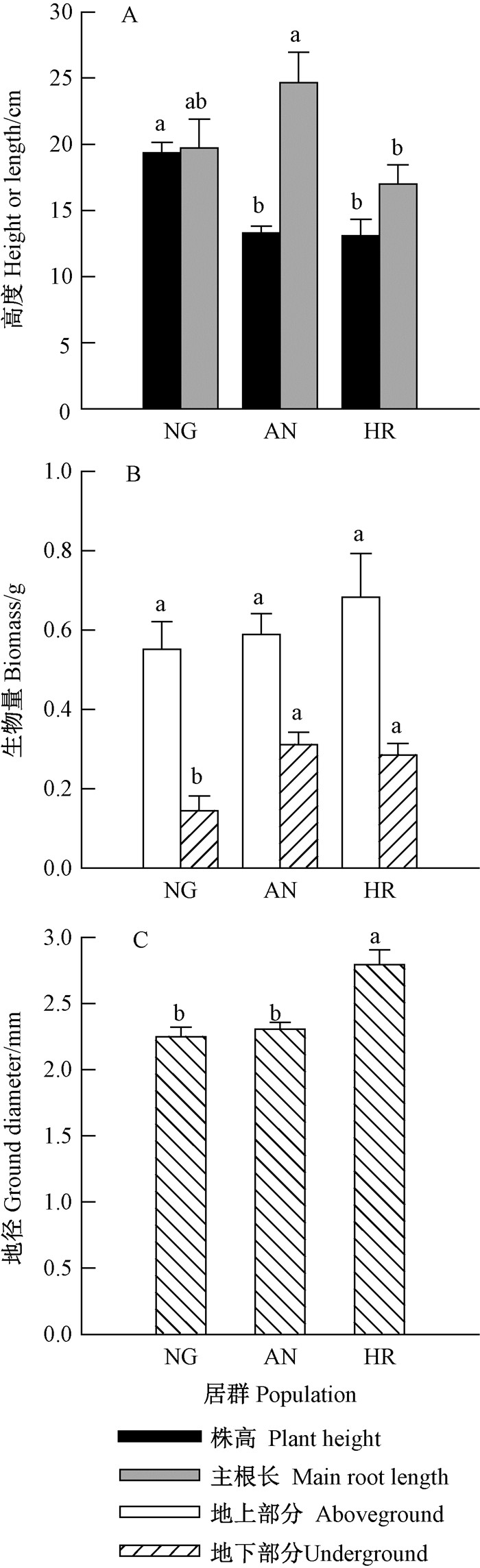

如图 10所示,NG种群幼苗的株高为19.34 cm,显著高于AN和HR种群,AN种群的主根长达24.66 cm,显著长于HR种群(图 10A)。对于地上部分生物量,3个种群间差异不显著;而地下部分生物量则NG种群显著小于其他2个种群(图 10B)。HR种群苗的地径显著大于其他2个种群(图 10C)。总体而言,NG种群的幼苗较细长,HR种群幼苗较粗矮且根系较发达。

|

图 10 不同种群种子对金丝李幼苗生长的影响 Figure 10 Effects of seeds of different populations on growth of G. paucinervis seedlings |

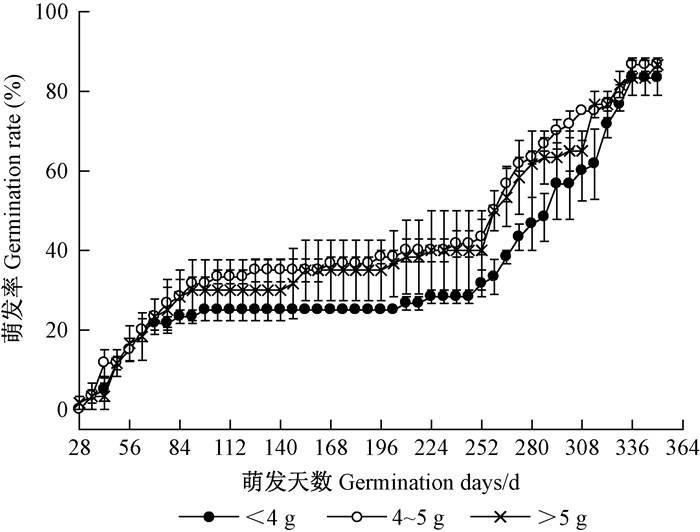

如图 11所示,3个质量级的种子萌发趋势相似,245天后种子萌发率增加较快,最终三者的GP均约为85%,对于GTL和MGT,三者差异也不显著(表 1)。而从GE来说,4~5 g的种子要显著高于<4 g的种子,但总体而言,3个质量级种子的萌发过程和萌发参数相近。

|

图 11 不同质量的金丝李种子的萌发动态 Figure 11 Germination process of G. paucinervis seeds in different seed weights |

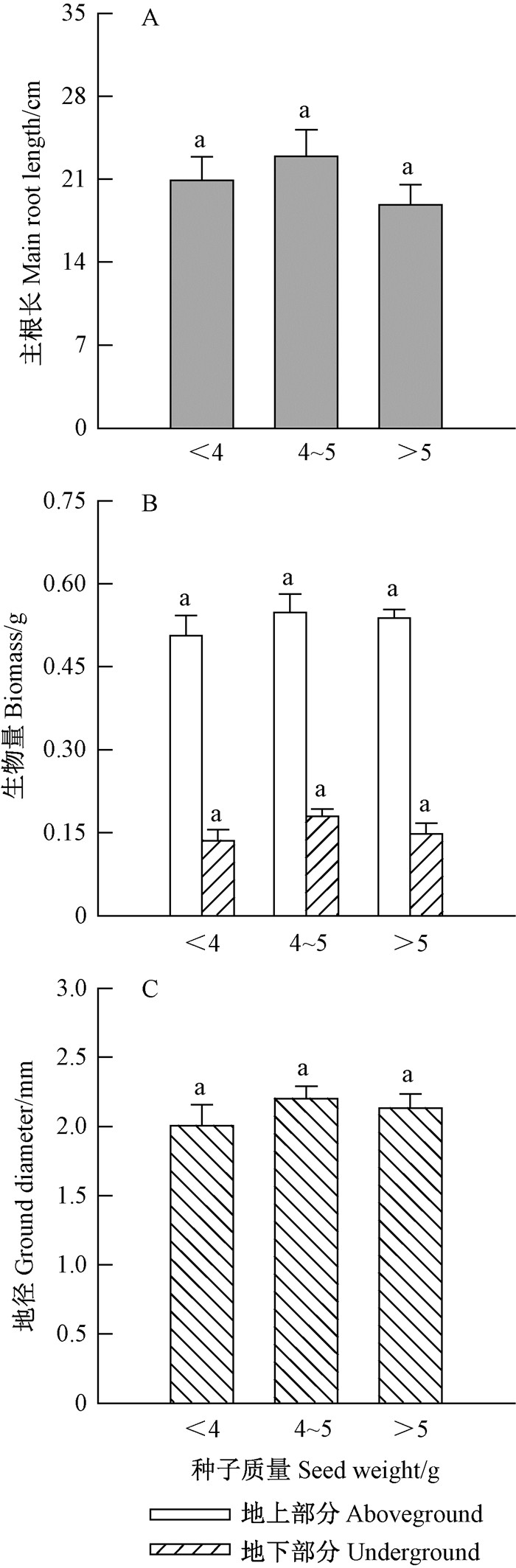

如图 12所示,而对于幼苗生长,无论是地上部分或者地下部分参数,不同重量级的种子形成的幼苗生长量差异均不显著。

|

图 12 种子质量对金丝李幼苗生长的影响 Figure 12 Effects of seed weights on growth of G. paucinervis seedlings |

已萌发的金丝李种子被摘除芽和根后再次播种,仍能萌发,252天时其萌发率达40.00%±7.64%,而新鲜种子在252天的萌发率为43.33%±6.01%,两者无显著性差异。在试验过程中,不慎碰断芽或短期干旱造成芽顶端枯萎,正常管理后可观察到新芽再次萌发,也证明了金丝李种子具有再生能力。

3 讨论 3.1 金丝李种子的萌发与幼苗生长种子休眠指具有生活力的种子在适宜的条件下不能正常萌发的现象(Bewley, 1997)。金丝李种子生活力高达95.56%,但平均萌发时间均大于100天,部分种子300天之后才能萌发,萌发十分缓慢且时间非常分散,中间大多有一段时间的停滞,且350天后经TTC法检测仍存在有活力种子,所以推测金丝李种子存在休眠,休眠可调节种子萌发的最佳时间及植株空间分布,使之不断发展进化(Vleeshouwers et al., 2001)。

带内果皮和去种皮的种子虽与对照比萌发缓慢,但三者最终萌发率无显著差异。金丝李内果皮蜡制,可能是其在不良环境下防止水分快速丢失和病原菌入侵的保护机制(Hu et al., 2009),但其存在对种子萌发造成机械阻碍或限制水分、氧气的供应,延缓萌发。去种皮后萌发速度比对照慢,说明种皮对种子萌发不存在抑制作用,可能是种子失去了种皮的保护易受感染而影响其萌发。

金丝李种子萌发对温度的适应范围较窄,18 ℃和37 ℃下不能萌发,25、32 ℃和室温下种子能萌发,其中32 ℃下能显著加快其萌发进程,与它所处的北热带和南亚热带的生境相吻合。18 ℃和37 ℃时可能降低了细胞膜的透性、影响酶的活力而抑制了种子萌发(Nyachiro et al., 2002; Gulzar et al., 2001),加上金丝李种子含水量高达45.29%,通常含水量高于25%的种子其抗热性较弱,若温度高于36 ℃,易损伤种胚甚至死亡(杨期和等, 2001)。种子适宜萌发的温度范围窄是一些濒危植物的共同特点,如西双版纳季雨林中的山红树(Pellacalys yunnanensisi)和30 ℃时萌发率能达90%以上,35 ℃时萌发减缓,25 ℃以下种子不能萌发(马信祥等, 1988);绒毛番荔枝(Pometia tomentosa)含水量高达50%,30 ℃时萌发率为85.3%,而25 ℃和10 ℃时仅为38.9%和1.9%(闫兴富, 2006)。根据种子萌发对光照的需求,将种子分为需光种子、忌光种子和光中性种子(Fenner, 1992)。金丝李种子在有无光照条件下均能萌发,虽萌发速度不同,但最终萌发率无显著差异,说明光照不是其萌发的必要条件,为光中性种子。石山上的光强随海拔、坡向、岩石的裸露程度和植被的郁闭度而多变,所以金丝李种子萌发对光照要求不严也是其适应环境的生态对策。

6种基质中,金丝李种子在河沙和泥炭土中的萌发率最高,黏质壤土或石山土不利于种子萌发,且在黏质壤土里腐烂率高。黏质壤土和石山土通气透水性能不佳,种子在缺氧条件下萌发易产生有害中间产物和过多呼吸热,导致种子生活力降低(Northcote, 1979)。河沙和泥炭土疏松、透气性强,氧气供应较充足,种子霉变率较低而萌发率较高。金丝李种子胚乳中贮存的养分较多,萌发后种子留存,幼苗早期可依靠胚乳中养分的供给以维持其正常生长,所以即使在珍珠岩、蛭石等养分缺乏的基质中,幼苗长势均较好。金丝李种子在石山土中萌发以40% ~60%的含水量为宜,而20%含水量的石山土虽不能萌发,但试验结束后种子生活力高,可作为储藏金丝李种子的一种方法。河沙的透气性比石山土强,同等埋深下以河沙为基质的发芽势和萌发率比以石山土为基质高,与不同基质萌发试验结论一致,且随着埋深增加,发芽势和发芽率均降低,河沙埋深0.5 cm的处理萌发速度最快、最整齐。综合金丝李种子在不同水分、基质、埋深下的萌发情况,说明其萌发对基质通气透水性反应敏感,埋土愈深,通气愈不良,O2浓度愈低,萌发愈被抑制。而金丝李种子在野外石山的萌发情况是否与实验室石山土条件下类似,需要进一步研究。

种子起源地的生态地理因素,如经纬度、海拔、水分、营养、植被种类与覆盖程度及其干扰强度(Baskin et al., 1998)等使植物在环境适应过程中其遗传物质发生了变异和分化,造成种群间萌发率和幼苗生长的显著差异。张俊杰等(2017)在调查AN、NG、HR 3个金丝李种群中发现,AN和NG种群均有百余株,而HR种群仅存7株,试验中HR种群萌发率也最低,可能是由于小种群花粉传播受限,易发生遗传漂变和有害突变累积的近交衰退,导致遗传多样性的丧失而造成的(Kery et al., 2000)。关于种子大小对其萌发或成苗质量的影响有人认为种子大小或质量与萌发速度、萌发率、苗大小呈显著正相关(Greipsson et al., 1995;Wu et al., 2006);但另有报道表示它们之间的关系不大(Eriksson, 1999;Huang et al., 2004)。而在金丝李种子研究上表明,支持后者的观点,其萌发和生长在不同质量等级上差异不显著。推测其幼苗早期主要靠吸收胚乳中贮存的养分来维持生长,<4 g的种子储藏的养分已满足了幼苗前期生长的需求。然而,种子萌发所需的温度、光照、水分及氧气等因子是互相联系与制约的,这些因子间的交互作用对种子萌发的影响有待进一步研究。

3.2 金丝李种子的萌发特性与其他藤黄属植物的比较金丝李种子在25 ℃和32 ℃下的MGT分别为194和110天;云树(G. cowa)种子的MGT为252天(Liu et al., 2005);木竹子(G. multiflora)和G. gummi-gutta种子的GTL分别为83天和7个月(王英强等, 1999; Joseph et al., 2011);G. kola种子在原生境有6周至18个月的休眠(Aduse-Poku et al., 2003)。而G. indica,G. cambogia和G. xanthochymus种子的萌发相对较快,GTL为8~20天(Malik et al., 2005),说明藤黄属植物种子大多萌发缓慢。而去掉种皮能显著改善山竹子、木竹子、云树和G. kola种子的透水、透气性,提高发芽率和萌发整齐度(高艳梅等, 2016;Liu et al., 2005;Oboho et al., 2010),但金丝李的种皮被剥离后反而延缓其萌发时间,说明藤黄属植物种皮的结构与致密度有较大区别。

金丝李种子在未萌发时胚芽、胚轴和胚根不易区分,已萌发的种子芽和根被摘除后具有再生能力。前人对其他藤黄属植物的再生能力也有研究:Richards(1990)认为10种藤黄属植物为无融合结实(agamospermy),以致种子可再生;Teo(1990)对山竹子(G. mangostana),Malik等(2005)对3种藤黄属植物以及Juliana等(2007)对G. kola的研究发现,它们的种子都具有再生能力,胚中看不到分化的子叶和胚轴,具有再生能力的胚胎轴是含有一系列胚胎组织的未成熟的胚。而金丝李是否为无融合生殖,需对其生殖生物学和胚胎学进一步确认。

3.3 金丝李种子和幼苗阶段的生态适应性及致濒因素种子的形态和萌发是植物两个关键的繁殖策略,关系到幼苗的存活能力及个体未来的适合度(Donohue et al., 2005; Leishman et al., 2000)。种子萌发阶段中若存在任何不利于种子萌发的因素会对植物繁衍后代的生活史对策、种群的稳定和新个体的产生与补充产生直接影响(Mills et al., 2005),可能导致该物种濒危或分布受限。金丝李种子的平均质量为4.570 g,远高于乔木树种种子的平均质量0.3 279 g(Silvertown, 1984),大粒种子营养贮备较多,有利于萌发的幼苗在山林较厚的凋落物中成功建植(Thompson, 1987)。金丝李采取产生少量的大种子以便取得竞争优势的生殖策略,即K-对策(殷现伟等, 2002),种子产出的周期长、成本高(Willson, 1983),成熟脱落后被动物采食或沿山坡向下小范围的散落,传播的能力和范围有限,种群难以扩张,加上金丝李有结实的植株少,以致于幼苗数量少,若种群受到开垦、砍伐等剧烈干扰,则种群规模难以恢复而易导致濒危。

金丝李果实成熟期恰为石山地区高温多雨的夏季,部分种子借着合适的环境于当年萌发,未萌发种子随动物踩踏、雨水、凋落物分解等因素埋入土壤中作为潜在种群,形成土壤种子库以度过低温干燥的冬季,来年温度升高雨水增多时再萌发为种群补充后代,种子持续的萌发行为是其风险分摊的一种生态对策,可保持一定的种群密度和较高的适合度,也能避免突发性环境变化(如干旱、山体滑坡)引起的大批量死亡,有利于金丝李种群的生存与繁衍。再者,其种子的再生能力可防止幼苗被动物践踏或被坠枝压断造成的建苗失败,使有限的种子得到充分利用。但金丝李种子的萌发特性也是其种群更新的主要障碍所在,其缓慢的萌发过程不利于种群空间资源的迅速占据,在种子未萌发期间要忍耐细菌病虫、动物捡食等各种环境压力。由试验可知,其萌发喜疏松、透气性好的基质,需要一定的水分条件。而近年来金丝李所在的石山植被遭到破坏,凋落物减少,导致通透性好的腐叶土层减少,造成土壤板结不利于种子萌发,种子若落于岩石上,其保水性不佳也难以萌发。此外,石山上水分条件波动大,加之森林被伐造成的年平均相对湿度下降,秋季如遇到晴热天气,易造成土壤干旱而抑制种子萌发;若雨量过多则通气性不佳,温湿度过高则种子易发霉变质均降低种子萌发率,也是导致金丝李幼苗偏少、天然更新困难的重要因素。即种子萌发对土壤严苛的透气和水分要求难以适应多变的环境可能是其稀有的重要原因。因此,需加强金丝李原生境的生态保护,尤以小种群生境为甚。其次,金丝李幼苗生长缓慢,播种350天后早期萌发的幼苗株高仅为13.07~19.34 cm,与竞争能力强的植物相竞争难以取得优势地位,也是其濒危的另一原因。而种子转化成幼苗阶段受阻只是金丝李致濒的一方面原因,通过种群遗传学,对金丝李进行遗传多样性研究,从分子水平上了解其濒危机制是今后研究的重点。

4 结论金丝李种子存在休眠,其萌发对温度的适应范围较窄,对基质的通气透水性反应敏感,其种子的再生能力虽可防止其成苗失败,提高其繁殖效率,但种子的萌发过程长,幼苗生长缓慢,不利于种群空间资源的迅速占据,种子萌发对土壤透气和水分要求较高是导致其种群衰落、沦为濒危的重要原因。人工培育金丝李应于成熟期适时采收果实,去掉果皮保留种子种皮,采用泥炭土或河沙等透气性较好的基质,播于32 ℃的培养箱或于夏季播于苗床,0.5~1 cm浅埋,防止过干或过湿。若在秋季播种,则可用黑色地膜覆盖以提高夜间地表温度。种子萌发后保持32 ℃左右的较高温也有利于金丝李幼苗的生长。

陈家庸, 黄正福. 1988. 珍稀濒危植物引种保存的初步研究[J]. 广西植物, 8(2): 179-189. (Chen J Y, Huang Z F. 1988. A preliminary study on the introduction and preserving of rare and endangered plants[J]. Guihaia, 8(2): 179-189. [in Chinese]) |

傅立国. 1991. 中国植物红皮书[M]. 北京: 科学出版社. (Fu L G. 1991. China plant red data book[M]. Beijing: Science Press. [in Chinese]) |

高艳梅, 陈兵, 范愈新, 等. 2016. 不同饱满度和不同处理对山竹子种子萌发的影响[J]. 中国热带农业, 71(4): 47-49. (Gao X M, Chen B, Fan Y X, et al. 2016. Effect of different plumpness and different treatments on seed germination of Garcinia mangostana[J]. China Tropical Agriculture, 71(4): 47-49. [in Chinese]) |

国家环境保护局, 中国科学院植物研究所. 1987. 中国珍稀濒危保护植物名录(第1册)[M]. 北京: 科学出版社. (State Bureau of Environmental Protection, Institute of Botany, CAS. 1987. Rare and endangered species list in China (Volume 1)[M]. Beijing: Science Press. [in Chinese]) |

李合生, 孙群, 赵世杰, 等. 2000. 植物生理生化试验原理和技术[M]. 北京: 高等教育出版社. (Li H S, Sun Q, Zhao S J, et al. 2000. Principles and techniques of plant physiology and biochemistry experiment[M]. Beijing: Higher Education Press. [in Chinese]) |

李文良, 张小平, 郝朝运, 等. 2008. 珍稀植物连香树(Cercidiphyllum japonicum)的种子萌发特性[J]. 生态学报, 28(11): 5445-5453. (Li W L, Zhang X P, Hao C Y, et al. 2008. Characteristics of seed germination of the rare plant Cercidiphyllum japonicum[J]. Acta Ecologica sinica, 28(11): 5445-5453. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-0933.2008.11.028 [in Chinese]) |

马信祥, 杨祝良, 许再富, 等. 1988. 国家重点保护植物山红树濒危原因的研究[J]. 云南植物研究, 10(3): 311-316. (Ma X X, Yang Z L, Xu Z F, et al. 1988. A study of the causes threatening Pellacalyx Yunnanensis, a species receiving priority protection in China[J]. Acta Botanica Yunnanica, 10(3): 311-316. [in Chinese]) |

王英强, 冯颖竹. 1999. 多花山竹子种子萌发及其幼苗生长分析. 仲恺农业技术学院学报, 12(2): 19-25. (Wang Y Q, Feng Y Z. 1999. A study on seed germination and seedling growth of Garcinia mutiflora. Journal of Zhongkai Agrotechnical College[in Chinese]) |

闫兴富. 2006. 望天树和绒毛番龙眼的种子萌发、幼苗生长及其生境选择特征. 西双版纳: 中国科学院西双版纳热带植物园博士学位论文. (Yan X F. 2006. Seed germination, seedling growth, and habitat preference of Shorea wantianshuea and Pometia tomentosa in tropical seasonal rain forests. Xishuangbanna: PhD thesis of Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy Sciences. [in Chinese]) |

杨期和, 杨威, 李秀荣. 2001. 热带植物种子萌发影响因素初探[J]. 种子, 9(5): 45-49. (Yang Q H, Yang W, Li X Q. 2001. Preliminary study on factors affecting seed germination of tropical plants[J]. Seed, 9(5): 45-49. [in Chinese]) |

殷现伟, 常杰, 葛滢, 等. 2002. 濒危植物明党参与非濒危种峨参种子休眠和萌发比较[J]. 生物多样性, 10(4): 425-430. (Yin X W, Chang J, Ge Y, et al. 2002. A comparison of dormancy and germination of seeds between an endangered species, Changium smyrnioides, and a non-endangered species[J]. Anthriscus sylvestris, 10(4): 425-430. [in Chinese]) |

张俊杰, 柴胜丰, 吕仕洪, 等. 2017. 珍稀濒危植物金丝李的生境特征及致濒原因分析[J]. 生态环境学报, 26(4): 582-589. (Zhang J J, Chai S F, Lü S H, et al. 2017. The habitat characteristics and analysis on endangering factors of rare and endangered plant Garcinia paucinervis[J]. Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 26(4): 582-589. [in Chinese]) |

Aduse-Poku K, Nyinaku F, Atiase V Y, et al. 2003. Improving rural livelihoods within the context of sustainable development:case study of Goaso forest district[J]. TBI Student Platform Project: 28-28. |

Baskin C C, Baskin J M. 1998. Seeds:ecology, biogeography, and evolution of dormancy and germination[M]. San Diego: Academic Press.

|

Bewley J D. 1997. Seed germination and dormancy[J]. Plant Cell, 9(7): 1055. DOI:10.1105/tpc.9.7.1055 |

Burt-Smith G S, Grime J P, Tilman D. 2003. Seedling resistance to herbivory as a predictor of relative abundance in a synthesised prairie community[J]. Oikos, 101(2): 345-353. DOI:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.11052.x |

Donohue K, Dorn L, Griffith C, et al. 2005. The evolutionary ecology of seed germination of Arabidopsis thaliana:variable natural selection on germination timing[J]. Evolution, 59(4): 758-770. DOI:10.1111/evo.2005.59.issue-4 |

Eriksson O. 1999. Seed size variation and its effect on germination and seedling performance in the clonal herb Convallaria majalis[J]. Acta Oecologica, 20(1): 61-66. DOI:10.1016/S1146-609X(99)80016-2 |

Farm K, Garden B, Han B C H, et al. 2003. Summary of finding from some rapid biodiversity assessments in West Guangxi, China, July 1999[J]. South China Forest Biodiversity Survey Report Series (Online Simplified Version), (36): 5-6. |

Fenner M. 1992. Seed:the ecology of regeneration in plant communities[J]. Journal of Ecology, 81(2): 1-17. |

Greipsson S, Davy A J. 1995. Seed mass and germination behaviour in populations of the dune-building grass Leymus arenarius[J]. Annals of Botany, 76(5): 493-501. DOI:10.1006/anbo.1995.1125 |

Gulzar S, Khan M A. 2001. Seed Germination of a halophytic grass Aeluropus lagopoides[J]. Annals of Botany, 87(3): 319-324. DOI:10.1006/anbo.2000.1336 |

Hu X W, Wang Y R, Wu Y P. 2009. Effects of the pericarp on imbibition, seed germination, and seedling establishment in seeds of Hedysarum scoparium, Fisch.et Mey[J]. Ecological Research, 24(3): 477-478. DOI:10.1007/s11284-009-0592-7 |

Huang Z Y, Gutterman Y. 2004. Seedling desiccation tolerance of Leymus racemosus (Gramineae)(wild rye), a sand dune grass inhabiting the Junggar Basin of Xinjiang, China[J]. Seed Science Research, 14(2): 233-239. DOI:10.1079/SSR2004172 |

ISTA(International Seed Testing Association). 1996. International rules for seed testing[J]. Seed Science and Technology, 24(Supplement): 151-154, 335. |

Joseph A, Satheeshan K N, Jomy T G. 2011. Seed germination studies in Garcinia spp.[J]. Journal of Spices and Aromatic Crops, 16(2): 118-121. |

Juliana A, Moctar S, Edmond K, et al. 2007. Improving the collection and germination of West African Garcinia kola Heckel seeds[J]. New Forests, 34(3): 269-279. DOI:10.1007/s11056-007-9054-7 |

Kery M, Matthies D, Spillmann H H. 2000. Reduced fecundity and offspring performance in small populations of the declining grassland plants Primula veris and Gentiana lutea[J]. Journal of Ecology, 88(1): 17-30. |

Leishman M R, Wright I J, Moles A T, et al. 2000. The evolutionary ecology of seed size[J]. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 7(11): 368-372. |

Liu B, Zhang X, Bussmann R W, et al. 2016. Garcinia in southern China:ethnobotany, management, and niche modeling[J]. Economic Botany, 70(4): 416-430. DOI:10.1007/s12231-016-9360-0 |

Liu Y, Qiu Y P, Zhang L, et al. 2005. Dormancy breaking and storage behavior of Garcinia cowa Roxb.(Guttiferae) seeds:implications for ecological function and germplasm conservation[J]. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 47(1): 38-49. DOI:10.1111/jipb.2005.47.issue-1 |

Malik S K, Chaudhury R, Abraham Z. 2005. Seed morphology and germination characteristics in three Garcinia species[J]. Seed Science and Technology, 33(3): 595-604. DOI:10.15258/sst |

Mills M H, Schwartz M W. 2005. Rare plants at the extremes of distribution:broadly and narrowly distributed rare species[J]. Biodiversity and Conservation, 14(6): 1401-1420. DOI:10.1007/s10531-004-9666-6 |

Northcote D H. 1979. The physiology and biochemistry of seed dormancy and germination[J]. Febs Letters, 103(2): 381-381. |

Nyachiro J M, Clarke F R, Depauw R M, et al. 2002. Temperature effects on seed germination and expression of seed dormancy in wheat[J]. Euphytica, 126(1): 123-127. DOI:10.1023/A:1019694800066 |

Oboho E G, Urughu J A. 2010. Effects of pre-germination treatments on the germination and early growth of Garcinia kola (Heckel)[J]. African Journal of General Agriculture, 6(4): 211-218. |

Quero J L, Lorena G, Gómez-Aparicio L, et al. 2008. Shifts in the regeneration niche of an endangered tree (Acer opalus ssp.granatense) during ontogeny:using an ecological concept for application[J]. Basic and Applied Ecology, 9(6): 635. DOI:10.1016/j.baae.2007.06.012 |

Richards A J. 1990. Studies in Garcinia, dioecious tropical forest trees:agamospermy[J]. Botanical journal of the Linnean Society, 103(3): 233-250. DOI:10.1111/boj.1990.103.issue-3 |

Silvertown J W. 1984. Introduction to plant population ecology[J]. Vegetatio, 56(2): 86-86. |

Teo C K H. 1990. In vitro culture of the mangosteen seed[J]. Recent Advances in Horticultural Science in the Tropics, 292: 81-86. |

Thompson K. 1987. Seeds and seed banks[J]. New phytologist, 106(supplement): 23-24. |

Toure D, Burnet J E, Jianwei Z. 2010. Rare plants protection importance and implementation of measures to avoid, minimize or mitigate impacts on their survival in Longhushan Nature Reserve, Guangxi Autonomous Region, China[J]. Journal of American Science, 6(7): 221-238. |

Vleeshouwers L M, Kbouwmester H J. 2001. A simulational model for seasonal changes in dormancy and germination of weed seeds[J]. Seed Science Research, 11(1): 77-92. DOI:10.1079/SSR200062 |

Wei T, Xu X, Shen G, et al. 2016. Effect of environmental factors on germination and emergence of aryloxyphenoxy propanoate herbicide-resistant and susceptible Asia Minor bluegrass (Polypogon fugax)[J]. Weed Science, 63(3): 669-675. |

Wei Y, Dong M, Huang Z Y, et al. 2008. Factors influencing seed germination of Salsola affinis (Chenopodiaceae), a dominant annual halophyte inhabiting the deserts of Xinjiang, China[J]. Flora, 203(2): 134-140. DOI:10.1016/j.flora.2007.02.003 |

Willson M F. 1983. Plant reproductive ecology[J]. Systematic Botany, 10(3): 375. |

Wu G, Chen M, Zhou X, et al. 2006. Response of morphological plasticity of three herbaceous seedlings to light and nutrition in the Qing-hai Tibetan Plateau[J]. Asian Journal of Plant Sciences, 5(4): 635-642. DOI:10.3923/ajps.2006.635.642 |

2018, Vol. 54

2018, Vol. 54