文章信息

- 孙志强, 张星耀, 肖文发, 梁军, 张兆欣

- Sun Zhiqiang, Zhang Xingyao, Xiao Wenfa, Liang Jun, Zhang Zhaoxin

- 景观病理学:森林保护学领域的新视角

- Landscape Pathology:A New Perspective in Forest Protection Field

- 林业科学, 2010, 46(3): 139-145.

- Scientia Silvae Sinicae, 2010, 46(3): 139-145.

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2009-05-05

-

作者相关文章

2. 中国林业科学研究院森林生态环境与保护研究所 国家林业局森林保护重点试验室 北京 100091;

3. 河南省濮阳市林业科学研究所 濮阳 457000

2. Key Laboratory of Forest Protection of State Administration of Forestry Research Institute of Forest Ecology, Environment and Protection, CAF Beijing 100091;

3. Puyang Forestry Research Institute of Henan Province Puyang 457000

从20世纪80年代后期以来,景观生态学在北美蓬勃发展,很大程度上促进了森林保护学科在理论、方法和应用等方面的发展。在生态等级、生物多样性以及森林生物灾害防控问题上,景观作为一个重要的组织层次已受到生态学家以及与之有交叉的森林保护学家的广泛重视(Diamond, 1975; Noss et al., 1986; Holdenrieder et al., 2004)。有学者提出,森林生物多样性和景观尺度的异质性相结合有可能成为未来森林病虫害生态调控的安全策略(梁军等, 2004; Jactel et al., 2002),即在制定森林保护策略时,不但需要考虑寄主的景观格局,同时要考虑景观组成(Cairns et al., 2008)。如何将森林病理学原理与景观异质性对森林病害发生过程的综合影响有机地结合,是未来森林保护学研究领域所面临的挑战,同时,这种群落水平与景观层次的结合也是森林保护学研究的新视角。

景观生态学关注的是空间格局和生态过程的相互影响与相互作用(Wilcove, 1987)。森林景观动态及多样性构成受非生物因素、植食性动物、林木病原物及人为因素的影响(Ledig, 1992)。在森林景观系统中,植被空间格局是景观特征的代表因子之一,而森林中抗病性不同的植物种类组成又是构成植被空间格局的主体,这种植被空间格局直接影响林中病原的扩散及传播, 景观特征与病害互相影响。在过去的几十年中,许多森林病害暴发更具有区域性,而不是仅仅局限在某一很小的地理范围(Castello et al., 1995)。从景观尺度上对森林病害的研究有助于预测病原的扩散速率及其对空间格局的影响、即森林病害流行与暴发的景观过程,有助于规划土地持续利用方式、制定森林病虫害可持续治理的决策。本文首先诠释Holdenrieder等(2004)提出的景观病理学(landscape pathology)概念及其研究方法,对近年来景观病理学的主要研究成果,包括景观破碎化对病原传播的影响、景观地形对病害发生的影响、寄主-病原的景观空间格局、气候变化背景下病害发生趋势和特点等作以评述; 并结合我国森林发展的现状提出景观病理学急需解决的几个问题。

1 景观病理学的概念及其研究方法Fleming(1991)使用“感病景观(diseased landscape)”描述农作物耕作格局对病害传播的影响,但未对“感病景观”作详细的定义。景观层次上,病害随时间扩散和变化(Yamada et al., 2000)、其分布依赖于寄主的生长状况和抗性(Liu et al., 1999); 同时,病原通常靠媒介传播,这些传播媒介有自身的分布和扩散格局。许多研究揭示了森林中病原的空间动态,而且病害的发生也会引起寄主空间分布的变化(Holah et al., 1997; Shearer et al., 1997; Campbell et al., 2000)。当森林病理学采用景观生态学的研究方法开展森林病害研究时,由于研究视角的改变,人们对森林病害发生的时间和空间格局有了更深的认识。

根据Holdenrieder等(2004)的观点,森林病理学(树木种群内病害发生规律研究)内在地包含着景观尺度的特征; 景观病理学是景观生态学与传统森林病理学结合而形成的新的交叉学科。它以植物病理学和森林病理学理论为基础,结合景观生态学的空间和时间分析方法,重点开展空间特征与病害发展过程间关系的研究(Lundquist et al., 2009)。当前的许多流行病学模型利用现代数学工具,参考景观生态学家及复合种群模型制作者的理念和方法对病害流行与暴发作出预测(Jeger, 1989; Kranz, 2003)。空间模型方法和景观分析方法在病原扩散、树木病害严重程度的调查方面已经发挥了重要的作用(Coulston et al., 2003; Staden et al., 2004)。

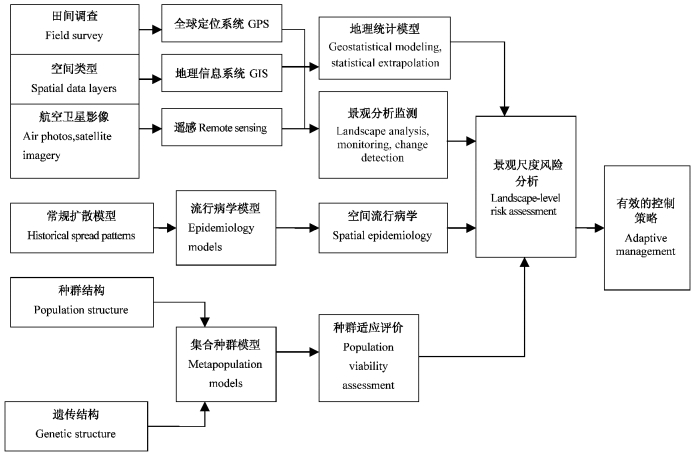

景观病理学的研究方法是首先通过空间数据获取、如空间结构数据收集、航空及卫星影像处理,田间调查数据获取,然后结合常规病原扩散模型分析、种群结构及遗传结构分析等技术对森林病害的流行暴发进行分析和预测,进而为制定病害治理措施提供依据(图 1)(Holdenrieder et al., 2004)。景观病理学切中了景观健康和景观恢复背景下的森林可持续治理和利用的需求,同时为开展景观空间格局下人为干扰对病害发生影响的定量调查与分析提供了新的途径。景观生态学与森林病理学的结合无疑将改进并增进人们对树木病害发生的时空过程的新理解和认识。

|

图 1 景观病理学数据收集、数量化工具及分析途径 Figure 1 Data sources, quantitative tools and analytical approaches central to landscape pathology evelution models |

生物保护学家早已注意到景观破碎化(例如相对隔离的栖息地)对生物多样性保护有一定的负面效应。在破碎化的栖息地中物种基因流的分散有所减少。而边界效应的增大使剩余栖息地中的生物多样性不断降低,进而增加了孤立斑块中物种灭绝的可能性(Wilcove, 1987)。景观破碎化通常使寄主及其病原物处在不同的栖息地,而这些栖息地的结构和组成也在不停的变化中,因而难以预测破碎化对病原物种群变化及扩散率的影响。主要原因在于破碎化会限制树木的自然扩散,同时也降低寄主树木对气候变化的适应能力。环境条件的变化会增加树木的感病性,尤其是在那些存在基因流失的孤立种群中,这种效应会增强(Ledig, 1992)。进一步讲,病原通过人为携带方式的传播对生态系统会产生严重的影响,特别是对不同地区各自独立的生态系统的影响尤为显著(Orwig, 2002)。最近的一些模型模拟结果显示,在一个寄主与病原协同进化的系统中,通过动物为媒介携带并经由廊道传播的病原所带来的风险是巨大的(McCallum et al., , 2002)。

在不同空间规模上,近来的研究结果强调了景观连接度对树木病原扩散速率影响的重要性。Perkins等(2002)研究了美国东南海岸平原各自独立的火炬松(Pinus taeda)、湿地松(P. elliottii)(易感染锈病)、长叶松(P. palustris)(中度抗锈病)和在废弃农地上的天然次生栎树林(Quercus spp.)样地。对3个10 km×10 km样地,在每1 km2土地上设定100个点(小样地),通过对这些点的数据对土地利用和森林分布进行比较; 以感病性不同的林分之间的距离表示破碎化的程度。结果显示当地景观破碎化程度对病原扩散有着举足轻重的影响。在本例中,目前的森林分布格局缩短了林分间的平均距离因而增加了景观连接度,从而导致病原更易于在不同斑块间的扩散,特别是由风力传播的真菌分生孢子在不同斑块间的扩散。

另一个为期23年的研究结果同样支持了景观连接度促进病原传播和扩散的假说(Hamelin et al., 2000)。该研究在美国西海岸一个面积为37 km2的样地内展开,调查了景观格局和人为因素对为害罗氏红桧(Chamaecyparis lawsoniana)的疫霉根腐病菌(Phytophthora lateralis)传播和扩散的影响。结果表明,病原的扩散首先通过森林中木材的运输机械随着泥土中的繁殖体以及原木沿林内公路网扩散、随后沿着河流扩散。该作者评价了运输机械在大区域尺度下对病原扩散的作用,同时比较了在小区域尺度下由野生动物、牲畜、徒步旅行者及工人对病原扩散的影响。对过去未感染疫霉根腐病菌的林区,运输机械对病原扩散起的作用最为强烈。

在相对较大的景观尺度下,景观破碎化有效阻止了白松疱锈病菌(Cronartium ribicola)的扩散(Hamelin et al., 2000)。美国东西部松疱锈病病原种群之间存在高度遗传差异,造成这种差异的原因被认为是疱锈病病原的基因流被横贯东西之间数百英里宽的大平原阻断。在这个平原上,疱锈病菌的5种针叶树寄主及转主寄主茶藨子属(Ribes spp.)没有分布。如果这条巨大的天然屏障被人为打破, 如病原通过机械运输从某一地理区域传入另一个区域,不但会导致传入区域遗传多样性的增加,而且在这2个区域中有可能出现高致病性病原以及病害的暴发(Hamelin et al., 2000)。

特别值得关注的是景观内斑块面积与病害发生之间的关系,研究证实景观内的斑块面积对病害及虫害暴发有潜在而重要的影响; 如斑块内大面积的成熟花旗松(Pseudotsuga menziesii)更易遭受病虫害为害且受害严重(Powers et al., 1999)、而小的松林斑块受害轻(Ylioja et al., 2005)。除斑块面积外,斑块在景观内的孤立程度也是抑制病害暴发的一个因素,如森林景观镶嵌体中越是孤立的斑块中的寄主树木,遭受病虫害为害的程度越低(Cappuccino et al., 1998; Floater et al., , 2000; Jactel et al., 2002)。对引入式斑块(Forman et al., 1981)的调查表明,单一品种的孤立的人工林面积为10~20 hm2时能最大限度降低病原的扩散和病虫害暴发(Mattson et al., 2001)。

综上所述,景观破碎化对病原传播的影响在不同地理尺度上的表现是有差异的。在微型或中型景观尺度(如数十至数百km2),景观连接度能够促进病原传播和扩散,但病害的暴发又受到景观内斑块面积和斑块孤立程度的制约; 而在大型景观尺度下,景观破碎化阻碍了病原的传播,但人为传播有可能打破这种天然阻隔,使病原传入新的地区并可能造成严重后果。其中最典型的例证是生物入侵问题,生物入侵已成为当前全球生态系统正经历的严峻的问题。板栗疫病(Endothia parasitics)、榆树荷兰病(Ophiostoma ulmi和Ophiostoma novo-ulmi)以及传入我国的松材线虫病(Bursaphelenchus xylophilus)就是很典型的例证。

2.2 景观地形对病害发生的影响病害发生动态不仅受制于病原的扩散,而且受到地形因素直接影响; 而病原的扩散又受到景观系统内斑块面积及地理地形结构的影响。Manter等(2003)调查了坡度坡向对美国西部花旗松人工林松针落叶病(Phaeocryptopus gäumannii)的影响。在病原水平相同的情况下,南坡较之北坡病害发生更为严重。Wilson等(2003)调查并预测了澳大利亚东南部17个不同立地条件下的硬叶植被的枯梢病病原疫霉菌(Phytophthora cinnamomi)的分布,该病原同时引起澳大利亚多种乡土树种的枯梢病。参与调查的指标包括坡度、坡向、海拔、样地与公路间的距离、平均树高、冠幅、树种、气候变量、土壤厚度和排水状况等,只有海拔和光辐射指标极显著影响病害发生率。其他的研究结果显示只有土壤湿度成为病原的限制因子(McDougall et al., 2002)。

在病原与病害发生的空间风险评估模型中,如何整合立地特征的倾向性及其作用是一项极具挑战性的研究内容(Venier et al., 1998)。Nevalainen(2002)在芬兰南部开展的有关地形特征对欧洲赤松(Pinus sylvestris)枯梢病(Gremmeniella abietina)发生影响的研究证明:海拔对病害的发生受相关尺度的影响; 在大尺度上树木死亡率与海拔呈正相关,但在某些具体小样地上两者却呈负相关。造成这种结果的原因可能是由于景观尺度的分析不适于解释小尺度范围病害的发生,因而小样地得出的结果与景观尺度的结论是不同的。同时,微型环境的结果可能会高估病情,原因在于微型环境调查往往集中在那些病害发生最重的林分样地中(Nevalainen, 2002)。

但是,在景观水平上掌握病害发生规律、开展病害控制仍然需要大量微观尺度(如标准地)的信息。如果小样地调查不能确切反映景观范围内病害发生的实际情况,那么,这样的小样地的调查结果会产生偏差而不利于最终的管理决策。实际上,目前的许多研究都是将调查地区的总面积和样地的空间特点割裂开,因而不能准确评价景观地形特征对病害发生的综合效应。因此,要避免调查区域的数据可能与实际病害发生状况不符(Pryce et al., 2002),必须综合考虑调查样地的规模,以及寄主、病原和环境相互作用构成的病害系统(phytosystem)的特点。

2.3 寄主的景观空间格局与病害发生的关系除不同地理尺度下的景观地形特征、土壤特征及气候特征外,植被空间格局对病害发生起着关键作用(Hessburg et al., 1999)。例如,通过对由金钱菌(Collybia fusipes)引起的根腐病发生的立地特征以及寄主分布的综合分析,比仅仅对环境或对寄主单独的调查结果更加翔实(Piou et al., 2002)。一项对位于不列颠哥伦比亚省的亚高山上分布的54个美国白皮松(Pinus albicaulis)林的研究表明,小气候和立地变量与松疱锈病的发生相关性不显著,决定性因子是林分结构及转主寄主的数量和分布状况(Campbell et al., , 2000)。对美国大湖地区的北美乔松(Pinus strobus)来说,气候因素和地形特征是影响锈病发生的最主要因子(White et al., 2002)。但美国白松疱锈病的发生与寄主空间分布格局有关,而这种相关性需要进一步的数据支持。

从群落水平开展的生物多样性与病虫害发生关系的研究中,人们已经认识到树种组成,特别是寄主树种在林间的比例,比树种多样性对潜在病虫害暴发的影响更加持久和深远(Vehviläinen et al., 2007; Koricheva, et al., 2006)。

历史因素(如过去寄主与病原的分布)同样是影响病害发生发展的重要因素,同时历史因素也是建立当前生态系统管理策略的基准。例如,瑞典北部的小干松(Pinus contorta)和欧洲赤松感染枯梢病菌和松星裂盘菌(Phacidium infestans)的比率明显偏高,原因在于这些树木被种植在云杉(Picea asperata)皆伐迹地上,而这种迹地上存在更多的病原(Witzell et al., 2000); 这个结果表明在大空间尺度上,植被空间格局的变化可能会长期地影响和改变植被感病性及病害流行方式(Guerrier et al., 2003)。

寄主的时空格局与真菌病原的致病性和分布有着紧密的联系,例如蜜环菌(Armillaria spp.)(Guillaumin et al., 1993)、疫霉(Phytophthora spp.)(Ristaino et al., 2000)及各种真菌-昆虫相互作用体系(Brandt et al., 2003)。在一个区域内,不同基因型病原的空间分布能够解释树木死亡率的差异。对来自俄勒冈州大尺度下蜜环菌种群结构、寄主分布、立地关系以及病害发生及严重程度的综合调查分析发现,2个兼容的雌雄同合体菌丝构成的遗传单体分布范围竟然达950 hm2,且该菌体已至少存在约1 900年(Ferguson et al., 2003); 在安大略省111个样地中,发现有100个样地中的树木受同一种蜜环菌菌索的侵染(McLaughlin, 2001)。这些例证强调了树木病原真菌在时间及空间的渗透性。这种对于大尺度下植物病原真菌的遗传结构空间格局的深入了解(Hubbes, 1993; Lundquist et al., , 2001),极大地丰富了有关生态及病原进化过程的知识(Jackson et al., 2002; Manel et al., 2003)。景观管理方法、树木基因流重新构建以及对其病原进化趋势的综合研究(Malanson et al., 1997; Sork et al., 1999),将为土地利用及气候变化背景下生态系统的可持续性利用提供理论基础。

2.4 景观尺度下病害发生对气候变化的响应气候变化背景下病害的发生趋势和特点只能在景观尺度上才能充分反映出病害流行的主导因子。如调查美国科罗拉多东南部白杨(Populus tremuloides)的逐年死亡率的结果显示,2006年死亡面积达56 091 hm2,占白杨总面积的的10%。死亡率在2002—2003年每年增加7%~9%,2006增加31%~60%。这主要是由于近十年持续高温和干旱,其次是由于干旱导致树木生长势衰弱,诱发一些次期性病虫害的暴发,从而进一步加重、加快了树木大面积死亡,如树木溃疡和烂皮病(Valsa sordida)及杨长角小蠹虫(Trypophloeus populi)、杨前隐小蠹(Procryphalus mucronatus),杨黄斑楔天牛(Saperda calcarata)和杨铜窄吉丁(Agrilus liragus)的大暴发; 其他因素如林分过熟、低密度和立地因素也是造成树木大量死亡的原因(Worrall et al., 2008)。对美国科罗拉多优胜美地国家公园针叶林大面积猝死的调查证实,干旱与死亡率之间相关性显著; 不同坡向的树木,其死亡在时间格局上无明显差异,但北坡的死亡密度比南坡高; 同期干旱诱发小蠹虫暴发也成为树木死亡一个重要原因(Guarŕn et al., 2005)。特别值得关注的是美国西部沿经度纵向的天然林自然死亡率最近数十年急速增长,该增长不分海拔、树木大小、优势属或是否有林火史。区域高温和随之发生的干旱可能是主要原因(Mantgem et al., 2009)。吕全等(2005)以松材线虫生长发育相关的气象因子为数据对松材线虫在我国的不同气候区潜在适生性进行评价,得到松材线虫的生态地理分布与实际发生地相符合; 同时研究显示,新疆的部分地区也适合松材线虫的生长发育。因此,研究结果对于重点预防区的侵入起着预警和应急的作用。

景观病理学研究有助于明确滞后效应、即病原在当前景观结构和寄主分布层面上的异相性。快速的气候变化可能导致病原的快速进化和变异、而由于树木对这种变化的适应有着明显的滞后效应,因此大范围和大规模的森林病害暴发将呈上升趋势。

3 景观病理学需要解决的问题目前,大多数景观病理学调查重点放在1种(或少数情况下2种)病害的病原-寄主-环境三角关系评价上(Francl, 2001)。在较大尺度下树木感病性,由此引起的物理结构倾向性变化,寄主遗传特性的空间数量化分析的研究还很缺乏。目前景观病理学急待解决的关键问题有如下几种:

1) 景观破碎化程度对病原扩散的综合影响有那些(Bennett, 1999)?由于景观破碎化对病原传播和扩散的影响在不同地理尺度上的表现是有差异的,而人为传播有可能打破天然屏障; 更有甚者,人为因素有可能比自然因素作用更大。因此,要深入了解景观破碎化对病原传播扩散的影响,必须确立开展研究的景观尺度,通过建立与相关生态特征相联系的分类指标,重点开展斑块的边缘效应对阻碍病原扩散的影响、传播媒介沿廊道扩散的规律等。在病原的景观空间异质性方面,需要回答的问题诸如:寄主或转主寄主的种群数量、密度及感病性的时空变化规律; 特定景观格局中潜在的能够减缓寄主-病原相互作用的抗病物种的数量及其丰度; 病原的致病性以及抗药性(Sherratt et al., 2003),等。

2) 具有抗病性的树种在哪种空间范围内能对病原传播起到显著的缓冲作用?在特定区域,环境、地形、气候与景观植被结构在决定病原扩散和病害发生上的相互作用是哪些?如建立人工林斑块混交模式,首先要选择对病害有显著抗性差异的树种或品种进行搭配,同时要判别树种对环境、地形、气候等的适应性,做到适地适树; 通过设立非寄主植被隔离带来达到阻碍病原传播的目的。这里需要重点开展的研究是资源条件(如寄主树木种植面积)对病原生长与繁殖的影响。病害暴发可以用临界阈值现象(critical threshold characteristic)来描述(邬建国, 2000),如病原种群增长与资源总量的关系,病原传播与感染率及与传播媒介的关系等(Murray, 1989)。

3) 如何设计适合于病害可持续生态控制的景观空间格局的土地利用体系?重点需要开展不同生物和非生物因素在引起复杂病害过程中的作用的研究(Thomas et al., 2002); 昆虫作为病原传播媒介的作用(Lewis et al., 2000); 根据不同景观特征下的病原扩散模式,最终界定树木病害的地理尺度的管理措施,如疫霉菌(Phytophthora spp.)沿河流的扩散模式(Gibbs et al., 1999; Jung et al., 2004)。

梁军, 张星耀. 2004. 森林有害生物的生态控制技术与措施[J]. 中国森林病虫, 23(6): 1-8. |

吕全, 王卫东, 梁军, 等. 2005. 松材线虫在我国的潜在适生性评价[J]. 林业科学研究, 18(4): 460-464. |

邬建国. 2000. 景观生态学—格局、过程、尺度和等级[M]. 北京: 高等教育出版社: 257.

|

Bennett A F. 1999. Linkages in the Landscape. The Role of Corridors and Connectivity in Wildlife Conservation.IUCN, Gland, Switzerland. http://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=1306135

|

Brandt J P, Cerezke H F, Mallett K I, et al. 2003. Factors affecting trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx.) health in the boreal forest of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba, Canada[J]. Forest Ecology and Management, 178: 287-300. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1127(02)00479-6 |

Cairns D M, Lafon C W, Waldron J D, et al. 2008. Simulating the reciprocal interaction of forest landscape structure and southern pine beetle herbivory using LANDIS[J]. Landscape Ecology, 23: 403-415. DOI:10.1007/s10980-008-9198-7 |

Campbell E M, Antos J A. 2000. Distribution and severity of white pine blister rust and mountain pine beetle on white bark pine in British Columbia[J]. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 30: 1051-1059. DOI:10.1139/x00-020 |

Cappuccino N, Lavertu D, Bergeron Y, et al. 1998. Spruce budworm impact, abundance and parasitism rate in a patchy landscape[J]. Oecologia, 114: 236-242. DOI:10.1007/s004420050441 |

Castello J D, Leopold D J, Smallidge P J. 1995. Pathogens, patterns, and processes in forest ecosystems[J]. Bioscience, 45: 16-24. DOI:10.2307/1312531 |

Coulston J W, Riitters K H. 2003. Geographic analysis of forest health indicators using spatial scan statistics[J]. Environmental Management, 31: 764-773. DOI:10.1007/s00267-002-0023-9 |

Diamond J M. 1975. The island dilemma: lessons of modern biogeographic studies for the design of nature reserves[J]. Biological Conservation, 7: 129-146. DOI:10.1016/0006-3207(75)90052-X |

Ferguson B A, Dreisbach T A, Barks C G, et al. 2003. Coarse-scale population structure of pathogenic Armillaria species in a mixed-conifer forest in the Blue Mountains of northeast Oregon[J]. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 33: 612-623. DOI:10.1139/x03-065 |

Fleming R A. 1991. Diseased landscape[J]. Oikos, 62: 3-7. DOI:10.2307/3545438 |

Floater G J, and Zalucki M P. 2000. Habitat structure and egg distributions in the processionary caterpillar Ochrogaster lunifer: lessons for conservation and pest management[J]. Journal of Applied Ecology, 37: 87-99. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2664.2000.00468.x |

Forman R T T, Godron M. 1981. Patches and structural components for landscape ecology[J]. BioScience, 31: 733-740. DOI:10.2307/1308780 |

Francl L J. 2001. The disease triangle: a plant pathological paradigm revisited. The Plant Health Instructor. DOI: 10.1094/PHI-T-2001-0517-01. https://www.apsnet.org/edcenter/instcomm/TeachingArticles/Pages/PlantDiseaseDoughnut.aspx

|

Gibbs J N, Lipscombe M A, Peace A J. 1999. The impact of Phytophthora disease on riparian populations of common alder (Alnusglutinosa) in southern Britain[J]. European Journal of Forest Pathology, 29: 39-50. DOI:10.1046/j.1439-0329.1999.00129.x |

Guarin A, Taylor A H. 2005. Drought triggered tree mortality in mixed conifer forests in Yosemite National Park, California, USA[J]. Forest Ecology and Management, 218: 229-244. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2005.07.014 |

Guerrier C L, Marceau D J, Bouchard A, et al. 2003. A modelling approach to assess the long term impact of beech bark disease in northern hardwood forest[J]. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 33: 2416-2425. DOI:10.1139/x03-170 |

Guillaumin J J, Mohammed C, Anselmi N, et al. 1993. Geographical distribution and ecology of the Armillaria species in western Europe[J]. European Journal of Forest Pathology, 23: 321-341. DOI:10.1111/efp.1993.23.issue-6-7 |

Hamelin R C, Hunt R S, Geils B W, et al. 2000. Barrier to gene flow between eastern and western populations of Cronartium ribicola in North America[J]. Phytopathology, 90: 1073-1078. DOI:10.1094/PHYTO.2000.90.10.1073 |

Hessburg P F, Smith B G, Salter R B, et al. 1999. Modeling change in potential landscape vulnerability to forest insect and pathogen disturbances: Methods for forested subwater sheds sampled in the mid scale interior Columbia River basin assessment. USDA Forest Service, General Technical Report, PNW-GTR-454, 1-56.

|

Holah J C, Wilson M V, Hansen E M. 1997. Impacts of a native root rotting pathogen on successional development of old growth Douglas fir forest[J]. Oecolgia, 111: 429-433. DOI:10.1007/s004420050255 |

Holdenrieder O, Pautasso M, Lonsdale D. 2004. Tree diseases and landscape processes: the challenge of landscape pathology[J]. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 19: 446-452. DOI:10.1016/j.tree.2004.06.003 |

Hubbes M. 1993. Impact of molecular biology on forest pathology: a literature review[J]. European Journal of Forest Pathology, 23: 201-217. DOI:10.1111/efp.1993.23.issue-4 |

Jackson R B. C R, Linder C R, Lynch M, et al. 2002. Linking molecular insight and ecological research[J]. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 17: 409-414. DOI:10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02571-5 |

Jactel H, Goulard M, Menassieu P, et al. 2002. Habitat diversity in forest plantations reduces infestations of the pine stem borer Dioryctria sylvestrella[J]. Journal of Applied Ecology, 39: 618-628. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2664.2002.00742.x |

Jeger M J. 1989. Spatial Components of Plant Disease Epidemics[M]. New York: Prentice-Hall.

|

Jung T, Blaschke M. 2004. Phytophthora root and collar root of alders in Bavaria: distribution, modes of spread and possible management strategies[J]. Plant Pathology, 53: 197-208. DOI:10.1111/ppa.2004.53.issue-2 |

Koricheva J, Vehviläinen H, Riihimäki J, et al. 2006. Diversification of tree stands as a means to manage pests and diseases in boreal forests: myth or reality[J]. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, (36): 324-336. |

Kranz J. 2003. Comparative Epidemiology of Plant Diseases[M]. Berlin: Springer.

|

Ledig F T. 1992. Human impacts on genetic diversity in forest ecosystems[J]. Oikos, 63: 87-109. DOI:10.2307/3545518 |

Lewis K J, Lindgren B S. 2000. A conceptual model of biotic disturbance ecology in the central interior of BC: how forest management can turn Dr[J]. Jekyll into Mr. Hyde. Forestry Chronicle, 6: 433-443. |

Liu X G, Xiang A R, Dong Z W, et al. 1999. Study on the spatial distribution pattern of ice nucleation bacterial canker of poplar and its application[J]. Journal of Northeast Forestry University, 27: 36-39. |

Lundquist J E, Hamelin R C. 2009. Forest Pathology: From Genes to Landscape. APS Press. The American Phytopathological Society. St. Paul, Minnesota U.S.A. http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=24021972

|

Lundquist J E, Klopfenstein N B. 2001. Integrating concepts of landscape ecology with the molecular biology of forest pathogens[J]. Forest Ecology and Management, 150: 213-222. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00566-1 |

Malanson G P, Cairns D M. 1997. Effects of dispersal, population delays, and forest fragmentation on tree migration rates[J]. Plant Ecology, 131: 67-79. DOI:10.1023/A:1009770924942 |

Manel S, Schwartz M K, Luikart G, et al. 2003. Landscape genetics: combining landscape ecology and population genetics[J]. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 18: 189-197. DOI:10.1016/S0169-5347(03)00008-9 |

Manter D K, Winton L M, Filip G M, et al. 2003. Assessment of Swiss needle cast disease: temporal and spatial investigations of fungal colonization and symptom severity[J]. Journal of Phytopathology, 151: 344-351. DOI:10.1046/j.1439-0434.2003.00730.x |

Mantgem P J, Stephenson N L, Byrne J C, et al. 2009. Widespread increase of tree mortality rates in the western united States[J]. Science, 323: 521-524. DOI:10.1126/science.1165000 |

Mattson W J, Hart E A, Volney W J A. 2001. Insect pests of populus: coping with the inevitable//Dickmann D I, Isebrands J G, Eckenwalder J E, et al. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/ref/10.1080/15226510701709689

|

McCallum H, Dobson A. 2002. Disease, habitat fragmentation and conservation[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Series B, 269: 2041-2049. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2002.2079 |

McDougall K L, Hardy St J G E, Hobbs R J. 2002. Distribution of Phytophthora cinnamomi in the northern jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata) forest of Western Australiain relation to dieback age and topography[J]. Australian Journal of Botany, 50: 107-114. DOI:10.1071/BT01040 |

McLaughlin J A. 2001. Distribution, hosts, and site relationships of Armillaria spp. in central and southern Ontario[J]. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 31: 1481-1493. DOI:10.1139/x01-084 |

Murray J D. 1989. Mathematical Biology[M]. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

|

Nevalainen S. 2002. The incidence of Gremmeniella abietina in relation to topography in southern Finland[J]. Silva Fennica, 36: 459-473. |

Noss R F, Harris L D. 1986. Nodes, networks and MUMs: preserving biodiversity at all scales[J]. Environment Management, 10: 299-309. DOI:10.1007/BF01867252 |

Orwig D A. 2002. Ecosystem to regional impacts of introduced pests and pathogens: historical context, questions and issues[J]. Journal of Biogeography, 29: 1471-1474. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2002.00787.x |

Perkins T E, Matlack G R. 2002. Human-generated pattern in commercial forests of southern Mississippi and consequences for the spread of pests and pathogens[J]. Forest Ecology and Management, 157: 143-154. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00645-9 |

Piou D, Delatour C. 2002. Hosts and distribution of Collybia fusipes in France and factors related to the disease's severity[J]. Forest Pathology, 32: 29-41. DOI:10.1046/j.1439-0329.2002.00268.x |

Powers J, Sollins P, Harmon M E, et al. 1999. Plant-pest interactions in time and space: a Douglas-fir bark beetle outbreak as a case study[J]. Landscape Ecology, 14: 105-120. DOI:10.1023/A:1008017711917 |

Pryce J, Edwards W, Gadek P A. 2002. Distribution of Phytophthora cinnamomi at different spatial scales: when can a negative result be considered positively[J]. Austral Ecology, 27: 459-464. DOI:10.1046/j.1442-9993.2002.01202.x |

Ristaino J B, Gumpertz M L. 2000. New frontiers in the study of dispersal and spatial analysis of epidemics caused by species in the genus Phytophthora[J]. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 38: 541-576. DOI:10.1146/annurev.phyto.38.1.541 |

Shearer B L, Byrne A, Dillon M, et al. 1997. Distribution of Armillaria luteobubalina and its impact on community diversity and structure in Eucalyptus wandoo woodland of southern Western Australia[J]. Australian Journal of Botany, 45: 151-165. DOI:10.1071/BT95083 |

Sherratt J A, Lambin X, Sherratt T N. 2003. The effects of the size and shape of landscape features on the formation of traveling waves in cyclic populations[J]. American Naturalist, 162: 504-515. |

Sork V L, Nason J, Campbell D R, et al. 1999. Landscape approaches to historical and contemporary gene flow in plants[J]. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 14: 219-224. DOI:10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01585-7 |

Staden V, Erasmus B F N, Roux J, et al. 2004. Modelling the spatial distribution of two important South African plantation forestry pathogens[J]. Forest Ecology Management, 187: 61-73. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1127(03)00311-6 |

Thomas F M, Blank R, Hartmann G. 2002. Abiotic and biotic factors and their interactions as causes of oak decline in Central Europe[J]. Forest Pathology, 32: 277-303. DOI:10.1046/j.1439-0329.2002.00291.x |

Vehvil?inen H, Koricheva J, Ruohomäki K. 2007. Tree species diversity influences herbivore abundance and damage: meta-analysis of long-term forest experiments[J]. Oecologia, 152: 287-298. DOI:10.1007/s00442-007-0673-7 |

Venier L A, Hopkin A A, McKenney D W. 1998. A spatial, climate-determined risk rating for Scleroderris disease of pines in Ontario[J]. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 28: 1398-1404. DOI:10.1139/x98-126 |

White M A. Brown T N, Host G E. 2002. Landscape analysis of risk factors for white pine blister rust in the Mixed Forest Province of Minnesota, USA[J]. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 32: 1639-1650. DOI:10.1139/x02-078 |

Wilcove D S. 1987. From fragmentation to extinction[J]. Natural Areas Journal, 7: 23-26. |

Wilson B A, Levis A, Aberton J. 2003. Spatial model for predicting the presence of cinnamom fungus (Phytophthora cinnamomi) in sclerophyll vegetation communities in south-eastern Australia[J]. Australia Journal of Ecology, 28: 108-115. DOI:10.1046/j.1442-9993.2003.01253.x |

Witzell J, Karlman M. 2000. Importance of site type and tree species on disease incidence of Gremmeniella abietina in areas with a harsh climate in Northern Sweden[J]. Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research, 15: 202-209. DOI:10.1080/028275800750015019 |

Worrall J J, Egeland L, Eager T, et al. 2008. Rapid mortality of Populus tremuloides in southwestern Colorado, USA[J]. Forest Ecology and Management, 255: 686-696. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2007.09.071 |

Yamada T, Ito S, Kokubu Y. 2000. Spatial distribution patterns and incidence-severity relationships of seiridium canker of young hinoki cypress[J]. Journal of the Japanese Forestry Society, 82: 248-251. |

Ylioja T, Slone D H, Ayres M P. 2005. Mismatch between herbivore behavior and demographics contributes to scale-dependence of host susceptibility in two pine species[J]. Forest Science, 51: 522-531. |

2010, Vol. 46

2010, Vol. 46