Development of a Reduced Chemical Reaction Kinetic Mechanism with Cross-Reactions of Diesel/Biodiesel Fuels

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11804-025-00634-3

-

Abstract

Biodiesel is a clean and renewable energy, and it is an effective measure to optimize engine combustion fueled with biodiesel to meet the increasingly strict toxic and CO2 emission regulations of internal combustion engines. A suitable-scale chemical kinetic mechanism is very crucial for the accurate and rapid prediction of engine combustion and emissions. However, most previous researchers developed the mechanism of blend fuels through the separate simplification and merging of the reduced mechanisms of diesel and biodiesel rather than considering their cross-reaction. In this study, a new reduced chemical reaction kinetics mechanism of diesel and biodiesel was constructed through the adoption of directed relationship graph (DRG), directed relationship graph with error propagation, and full-species sensitivity analysis (FSSA). N-heptane and methyl decanoate (MD) were selected as surrogates of traditional diesel and biodiesel, respectively. In this mechanism, the interactions between the intermediate products of both fuels were considered based on the cross-reaction theory. Reaction pathways were revealed, and the key species involved in the oxidation of n-heptane and MD were identified through sensitivity analyses. The reduced mechanism of n-heptane/MD consisting of 288 species and 800 reactions was developed and sufficiently verified by published experimental data. Prediction maps of ignition delay time were established at a wide range of parameter matrices (temperature from 600 to 1 700 K, pressure from 10 bar to 80 bar, equivalence ratio from 0.5 to 1.5) and different substitution ratios to identify the occurrence regions of the cross-reaction. Concentration and sensitivity analyses were then conducted to further investigate the effects of cross-reactions. The results indicate temperature as the primary factor causing cross-reactivity. In addition, the reduced mechanism with cross-reactions was more accurate than that without cross-reactions. At 700–1 000 K, the cross-reactions inhibited the consumption of n-heptane/MD, which resulted in a prolonged ignition delay time. At this point, the elementary reaction, NC7H16+OH < = > C7H15-2+H2O, played a dominant role in fuel consumption. Specifically, the contribution of the MD consumption reaction to ignition decreased, and the increased generation time of OH, HO2, and H2O2 was directly responsible for the increased ignition delay.-

Keywords:

- Marine engines and fuels ·

- Renewable energy ·

- Biodiesel ·

- Diesel ·

- Reduced mechanism ·

- Cross-reactions

Article Highlights● A new reduced chemical kinetics mechanism model of diesel and biodiesel was proposed.● The cross-reaction between n-heptane and methyl decanoate was considered to improve model accuracy.● Prediction maps of ignition delay time at a wide-range parameter matrix were established.● The effect significance of temperature on the cross-reaction of blended fuels was identified. -

1 Introduction

Approximately 30% of greenhouse gas emissions originate from the transportation sector (Sherbaz and Duan, 2012; Yang et al., 2021) due to the widespread use of fossil fuels. For light-duty transport, less emission-intensive propulsion can be potentially used, whereas long-haul heavyduty transport, especially sea transport, relies on diesel engines. The use of diesel engines inevitably results in the considerable consumption of fossil fuels and serious environmental pollution. To reduce sea transport emissions, the International Maritime Organization has established stringent emission regulations to limit the sulfur content of diesel and nitrogen oxide (NOx) and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from marine engines (Noor et al., 2018; Van et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2019). Therefore, the development of diesel engines will face energy and environmental challenges in the future (Liu et al., 2014a). Low-carbon, zerocarbon, and carbon-neutral alternative fuels must be investigated to address issues such as energy shortage, rising oil prices, and environmental pollution. Biodiesel is a potential surrogate for diesel, and it can effectively contribute to the transformation of energy structures and the achievement of carbon neutrality targets (Chisti, 2007; Wu et al., 2009; McCarthy et al., 2011; Mishra and Goswami, 2018).

Oxygenated biofuels have become a focus of research on engines due to their renewability and contribution to combustion improvement (Zheng et al., 2018). Biodiesels are produced from a wide range of sources (Ambat et al., 2018; Ramos et al., 2019; Zulqarnain et al., 2021), including vegetable oils (Banković-Ilić et al., 2012; Santori et al., 2012; Patel and Sankhavara, 2017; Veljković et al., 2018), animal fats (de Araújo et al., 2013; Adewale et al., 2015), microalgal oils (Meng et al., 2009; Gong and Jiang, 2011; Mubarak et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2018), and waste cooking oils (Zhang et al., 2003; Math et al., 2010). Biodiesel is the primary alternative fuel for diesel engines because of its similar properties to diesel fuel (Liu et al., 2014b); moreover, it can be blended in any proportion to create stable biodiesel blends (Abbaszaadeh et al., 2012). Therefore, structural modifications of the engine are not required when using biodiesel in diesel engine experiments to investigate combustion and emission characteristics (Basha et al., 2009; Qi et al., 2009; Narendranathan and Sudhagar, 2014; Yang et al., 2016). Research results show that the reported 10%– 11% oxygen content in biodiesel effectively improves the engine combustion performance, heat release rate, and reduces emissions such as CO, HC, soot, and particulate matter (PM), with the exception of NOx (Lahane and Subramanian, 2015; Wu et al., 2019). For the prediction of the combustion characteristics of diesel/biodiesel blends, a reduced mechanism of diesel/biodiesel blends must be developed.

Diesel is a mixture of components, such as alkanes, cycloalkanes, and aromatic hydrocarbons (Pitz and Mueller, 2011). Over the past decade researchers have made significant progress in the development of chemical kinetic mechanisms of diesel-related components, including n-heptane, n-decane, n-dodecane, and n-hexadecane (Pitz and Mueller, 2011; Vasudev et al., 2022). As a primary reference fuel of diesel fuel, the mechanisms of n-heptane oxidation have been studied well under various conditions, and the oxidation database and kinetic model have been well developed (Wang et al., 2023). n-Heptane has a cetane number of 56 (Han and Yao, 2015), similar to diesel. Curran et al. (1998) developed a detailed mechanism of n-heptane to predict its ignition delay time and species concentration variation. The mechanism includes 25 reaction types for n-alkanes and clarifies the importance of the low-temperature chemistry for the stable olefin species formed from hydroperoxide-alkyl radicals and chain-branching steps involving keto-hydroperoxide molecules. Su and Huang (2005) used the genetic algorithm to optimize a reduced model of n-heptane; with 40 species and 62 reactions, the reduced model effectively shortened the threedimensional computational fluid dynamics (3D-CFD) computation time, which illustrates the superiority of the reduced mechanism in engine combustion simulation. To achieve control of the homogeneous charge compression ignition (HCCI) mode in diesel engines, Zheng and Yao (2006) used an n-heptane mechanism to investigate diesel autoignition and combustion. Analysis of the dominant reaction of the oxidation process of n-heptane under HCCI conditions extended the application of the detailed n-heptane mechanism. Wang et al. (2023) investigated the effect of oxygen concentration on n-heptane oxidation, improved the comprehension of the combustion and pollutant emission characteristics of n-heptane oxygen-enriched combustion, and conducted experimental studies on n-heptane oxidation under low-equivalent-ratio conditions, which enriched the database on n-heptane oxidation.

The chemical makeup and specific properties of biodiesel make it an adequate consideration in the modeling of surrogate fuels. Gaïl et al. (2007) constructed a mechanism model of methyl butanoate (MB) to simulate the effect of oxygen content on biodiesel. The model was used to predict the high-temperature oxidation process of MB and describe the corresponding formation of intermediate species. According to Kumar and Sung (2016), the study of MB kinetics is necessary for the use of MB as an alternative fuel for biodiesel. However, the small molecular weight of MB fails to provide good results during the negative-temperature-coefficient (NTC) period of biodiesel combustion. Therefore, recent research has been devoted to the development of larger methyl esters to predict the NTC behavior of biodiesel (Diévart et al., 2012). Methyl decanoate (MD) has received attention as a biodiesel surrogate because of its properties, such as carbon chain length and methyl ester groups (Herbinet et al., 2008). Wang et al. (2013) indicated that MD can be a biodiesel representative in terms of ignition delay and smoke-emission characteristics. Herbinet et al. (2008) developed a detailed mechanism to investigate the oxidation process of MD, which was used as an alternative for biodiesel. The model can predict the NTC region, intermediate species generation, and early CO2 production of biodiesel. Sarathy et al. (2011) developed a mechanism for MD to gain insights into the basic combustion properties and pathways of biodiesel. Predictions and experimental results were observed due to the influence of methyl ester; low-molecular-weight oxygenated compounds of MD formed during oxidation. Diévart et al. (2012) developed a detailed mechanism for MD and used a wide range of experimental data to validate this model. The predictions were in good agreement with the experimental results, and the model can reflect the combustion characteristics of methyl esters. MD is a representative of biodiesel oxidation properties with respect to molecular weight, and methyl esters, serve as biodiesel surrogates.

To investigate the diesel/biodiesel combustion process, researchers have developed models based on the mechanisms of n-heptane and MD. Xiao et al. (2017) proposed a reduced mechanism for n-heptane and MD containing 113 substances and 306 reactions. Their study involved the construction of the consumption path of C7H15-1 and MD2J through the analysis of the reaction path of n-heptane and MD and clarification of the importance of intermediate products in the oxidation process. Oo et al. (2014) created a skeletal mechanism with 45 species and 74 reactions. The mechanism was confirmed by other specific mechanisms, and it was used to predict the ignition delay for MD and n-heptane. However, without considering the cross-reactions between fuels, explaining the important deviations in the validation process of the experimental data on waste cooking oil and diesel presents a challenge.

Researchers achieved progress in the development of the n-heptane/MD mechanism. Except for the methyl ester functional group, MD shows structural similarities to large n-alkanes. The n-heptane/MD modeling studies performed to date were based on distinct mechanisms but did not consider the cross-reactions between fuels. In blends, except for the chemical coupling of radical pools (O, OH, and H) during combustion, the interactions between various fuels and their radicals from low-temperature compression to the auto-ignition phase cannot be neglected (Andrae et al., 2005). Considering the properties of n-heptane and MD, the mechanisms of the two components must be combined for cross-reaction development.

Previous studies showed that N-heptane and MD can be regarded as appropriate surrogates for developing the detailed or reduced mechanisms of diesel/biodiesel fuels and achieving combustion prediction. However, most researchers obtained the reduced chemical reaction kinetic mechanism by separately simplifying and merging the reduced mechanism of each fuel. However, the interactions between n-heptane and MD blends were disregarded, which caused an increase in errors during combustion prediction. This study aimed to propose a new reduced mechanism of n-heptane and MD with cross-reactions. In addition, the prediction maps of ignition delay time for n-heptane/MD under a wide range parameter matrix of temperatures, pressures, equivalence ratios, and equivalence ratios were constructed. The effect significance of cross-reactions during the oxidation process of diesel and biodiesel was revealed within specific parameter intervals, and the dominant reaction and species were identified via sensitivity and concentration analyses. Our results can be used to develop an optimized mechanism model of diesel/biodiesel and are beneficial to the further improvement of the simulation precision and calculation speed of 3D-CFD simulation of internal combustion engines fueled with diesel and biodiesel.

2 Development of a reduced mechanism

2.1 Mechanism selection

Detailed mechanisms include a number of redundant reactions, and the development of reduced mechanism can effectively reduce the complexity of the detailed mechanism. In this study, n-heptane and MD were selected as surrogates for diesel and biodiesel, respectively, with the n-heptane mechanism (Zhang et al., 2016) containing 1 269 species and 5 336 reactions and the MD mechanism (Sarathy et al., 2011) including 621 species and 2 998 reactions. The mechanisms of both fuels were validated using experimental data.

2.2 Reduction method

Numerical simulations of engine combustion require highly accurate and appropriately sized mechanisms, whereas complex and detailed mechanisms necessitate reduction (Li et al., 2019). Through the use of reasonable mathematical methods, the species and primitive reactions of the detailed mechanism that exert an insignificant influence on the combustion process are removed, and the important species and corresponding primitive reactions are screened out to reduce the mechanism scale. In this work, directed relation graph (DRG) (Lu and Law, 2006), directed relationship graphs with error propagation (DRGEP) (Pepiot-Desjardins and Pitsch, 2008), and full species sensitivity analysis (FSSA) (Liang et al., 2009) were adopted to reduce the chemical kinetic mechanisms of n-heptane/MD.

2.3 Cross-reaction theory

Ester and alkane fuels vary in terms of composition, and when mixed, the interactions between them need to be considered. The cross-reaction theory has been proposed to describe this process. In typical cross-reactions, a free radical generated by one of the fuels abstracts hydrogen from the other fuel (Andrae et al., 2007). An alternative crossreaction can occur among the macromolecular dehydrogenation products of the multicomponent during free-radical exchange reaction (Liu et al., 2021). Inherent in the definition of the second kind of cross-reaction, the following types of reactions are considered:

$$ \mathrm{R} 1+\mathrm{R} 2 \mathrm{H} \leftrightarrow \mathrm{R} 1 \mathrm{H}+\mathrm{R} 2 $$ (1) $$ \mathrm{R} 1 \mathrm{OO}+\mathrm{R} 2 \mathrm{H} \rightarrow \mathrm{R} 1 \mathrm{OOH}+\mathrm{R} 2 $$ (2) $$ \mathrm{R} 2 \mathrm{OO}+\mathrm{R} 1 \mathrm{H} \rightarrow \mathrm{R} 2 \mathrm{OOH}+\mathrm{R} 1 $$ (3) Cross-reaction studies reveal the interactions that exist among fuels. In this study, a reduced mechanism of n-heptane/MD blends was developed based on the cross-reaction theory to investigate the effect of cross-reactions on diesel/biodiesel combustion predictions.

2.4 Mechanism reduction strategy

2.4.1 Reactor model

In this study, the effectiveness of the reduced mechanism was assessed using laminar flame speed, ignition delay time, and CO and OH concentration as indicators. The premixed flame model and closed homogeneous reactor from Chemkin-Pro were used for model calculations. The premixed flame model was used to calculate the laminar flame speed and the closed homogeneous reactor to compute the ignition delay time.

2.4.2 Reduction strategy

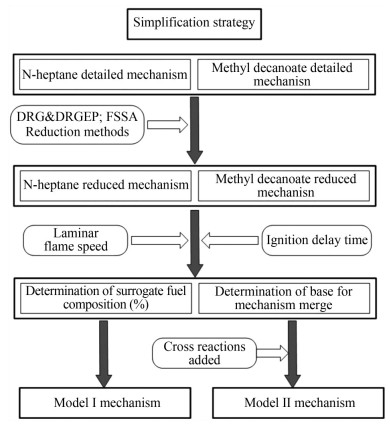

To maintain the high accuracy of the reduced mechanism, we used DRG, DRGEP, and FSSA in this study. The DRGEP and DRG methods were used to identify strongly coupled species in the detailed mechanism, along with the reduction targets of CO, CO2, and ignition delay time. Both methods were used alternately to remove redundant single-component species and obtain the reduced-scale response mechanism. Then, FSSA was performed to delete the remaining primitive reactions that showed no evident effect on the target products. After reduction, the reduced mechanism was verified via experimental results and detailed mechanisms. Finally, the reduced mechanisms of n-heptane and MD were merged. The detailed and reduced mechanism scales of n-heptane and MD are shown in Table 1, and the reduction strategy is displayed in Figure 1.

Table 1 Scales of detailed and reduced mechanismsFuel Mechanism Species Reactions N-heptane Detailed mechanism (Zhang et al., 2016) 1 269 5 336 Reduced mechanism 128 593 Methyl decanoate Detailed mechanism (Sarathy et al., 2011) 621 2 998 Reduced mechanism 271 990 2.5 Development of reduced mechanism with cross-reaction

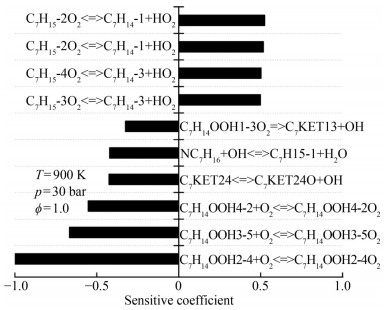

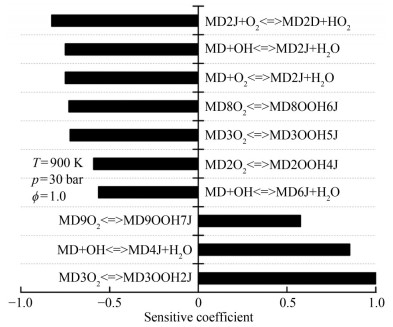

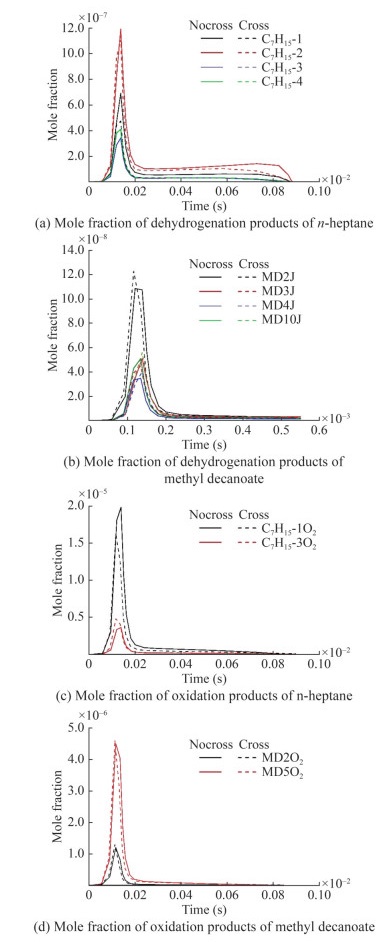

Cross-reactions were developed based on the reduced n-heptane/MD dual-fuel mechanisms. In accordance with the cross-reaction theory, macromolecular intermediates were extracted to develop a reduced mechanism with cross-reactions. Modeling studies of n-heptane/MD oxidation processes were carried out under various simulation conditions. The results were used to analyze the macromolecular intermediates, with the simulation conditions set out in Table 2. Previous research revealed that cross-reactions mainly occur in the low- and medium-temperature ranges and are insensitive to changes in pressure and equivalence ratio (Liu et al., 2021). This finding is explained as follows. H abstraction is the predominant part of the reaction at the medium-temperature range, and the reaction energy is insufficient to support the cleavage reaction of n-heptane. In this work, sensitivity analysis was performed using intermediate temperatures, and the results were used to construct the cross-reaction. The important intermediate products were obtained from the oxidation process of n-heptane/MD in the following conditions: ϕ=1.0, p=30 bar, and T =1 000 K (Figures 2‒5).

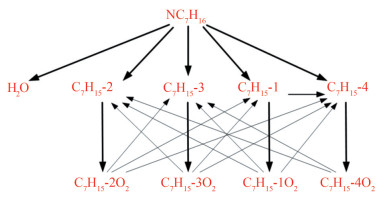

Table 2 Analysis conditionsSubstitution condition T (K) p (bar) ϕ N-heptane and MD 600–1 500 10–30 0.5–1.5 The extraction reaction of H-atoms from fuel (Eq. (4)) and the addition reaction of alkyl radicals to O2 (Eq. (5)) dominate the low-temperature phase of fuel oxidation (Curran et al., 1998). N-heptane undergoes the reaction in Eq. (4) to produce four structurally different alkyl radicals, which then participate in addition reactions (Eq. (5)) to produce peroxyalkyl. Thus, from the results in Figure 2, the dehydrogenation (C7H15-1, C7H15-2, C7H15-3, and C7H15-4) and oxidation products (C7H15-1O2, C7H15-2O2, C7H15-3O2, and C7H15-4O2) serve as the predominant consumption pathways of n-heptane. The results of normalized sensitivity analysis demonstrate the decisive role of intermediate components in the consumption of n-heptane.

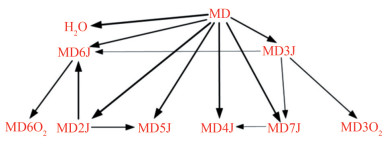

$$ \mathrm{RH}+\mathrm{OH}=\mathrm{R}+\mathrm{H}_2 \mathrm{O} $$ (4) $$ \mathrm{R}+\mathrm{O}_2=\mathrm{RO}_2 $$ (5) Reaction path and sensitivity analyses were used to analyze the dominant reaction of MD, and the results are shown in Figures 4 and 5. Yang et al. (2021) pointed out that the key consumption path of MD involves the attachment of hydrogen to carbon at varying positions adjacent to the carbonyl group within the ester functional group. Radicals, such as OH, H, O, and HO2, consume the most H from MD. The dominant reactions were the hydrogen abstraction reaction of the unimolecular fuel and the subsequent isomerization reaction (Eq. (6)) of RO2 resulting from the additional reaction with oxygens. MD2J and its isomers were identified as important products for the construction of cross-reactions. In consideration of the type of cross-reaction and sensitivity analysis results, MD2O2 and its isomers should be added to the reduced mechanism.

$$ \mathrm{RO}_2=\mathrm{QOOH} $$ (6) Therefore, cross-reaction development was performed based on the results of intermediate product analysis, and the combustion rate parameters were improved, referring to the work of Curran et al. (1998) and Herbinet et al. (2008). A total of 108 cross-reactions of n-heptane with MD were added to Model Ⅰ, which was consequently denoted as Model Ⅱ, which now consisted of 800 reactions of 288 species. All these added cross-reactions are shown in the Appendix.

3 Verification and analysis of the reduced mechanism

The reduced mechanism was widely verified against fundamental combustion experiments on each pure component and its blends. To ensure the accuracy of the reduced mechanism, we used ignition delay time and laminar flame speed.

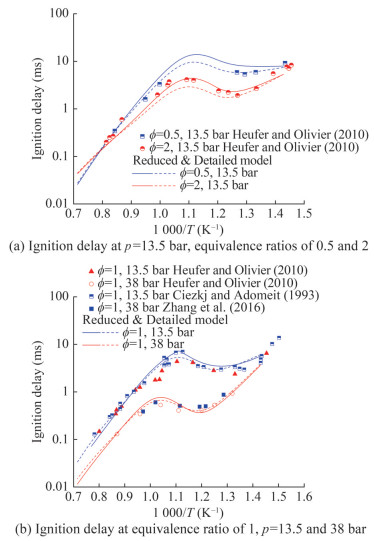

3.1 Verification of the n-heptane reduced mechanism

To validate the n-heptane reduced mechanism, we selected several shock tube studies (Ciezki and Adomeit, 1993; Heufer and Olivier, 2010; Zhang et al., 2016) for comparison with the model predictions. Figure 6 displays the predictions and experimental results for n-heptane. Figure 6(a) shows the consistency of detailed and reduced mechanisms in terms of the ignition delay time. In addition, the reduced mechanism is situated higher than the detailed mechanism in the NTC region. As exhibited in Figure 6(b), the reduced mechanism corresponded well to the trend of experimental results provided by Heufer and Olivier (2010) and Zhang et al. (2016). Overall, the NTC region of the ignition process for n-heptane was evident in predictions and the experimental results. The good overlap between predictions and experimental results demonstrates this reduced mechanism's reliability for the prediction of ignition delay.

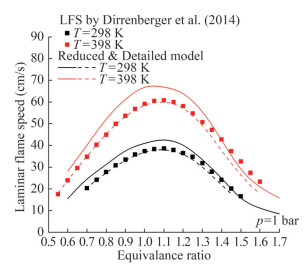

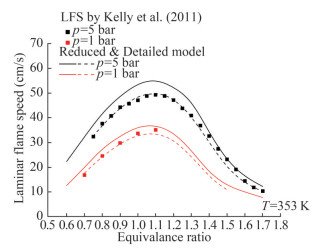

The current mechanism was validated using the n-heptane laminar flame speed data from previous works (Dirrenberger et al., 2014; Kelly et al., 2011). Figure 7 illustrates the laminar flame speed of n-heptane at a pressure of 1 bar and temperatures of 298 and 398 K. The detailed mechanism showed a good agreement with the verified experimental findings. The predictions of the detailed mechanism were almost identical to the experimental results. Figure 8 shows the n-heptane laminar flame speed at 353 K at pressures of 1 and 5 bar. The reduced and detailed mechanisms were in good agreement with the experimental finding. The overall trend did not change after reduction, but the reduced mechanism provided higher predictions than the detailed mechanism. The higher predictions are the outcome of the deletion of some intermediates and related reactions during the mechanism reduction, reaction rate errors, and lack of agreement on the reaction conditions. The reduced mechanism sacrifices a part of the prediction accuracy but gains a fast computational speed and a small mechanism scale.

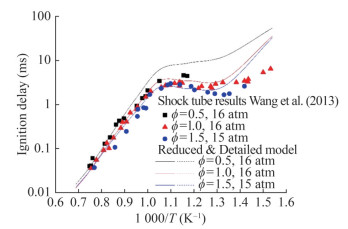

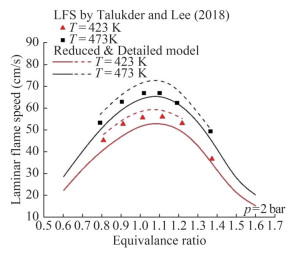

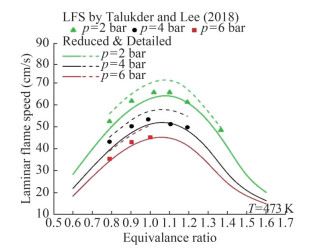

3.2 Verification of the MD reduced mechanism

We selected the results of the shock tube test to validate the reduced mechanism of MD (Wang et al., 2013). MD/air mixtures were investigated at equivalence ratios of 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5, temperatures from 653 to 1 336 K, and pressures of approximately 15–16 atm (Figure 9). The mechanism reproduces the behavior of the fully detailed mechanism in plug flow and stirred reactors at temperatures of 900–1 800 K, equivalence ratios of 0.25–2.0, pressures of 101 and 1 013 kPa (Figures 10 and 11). Figure 9 shows that the detailed and reduced mechanisms were in good agreement with the predicted results. The experimental results were close to the predictions in the intermediate- and high-temperature ranges. However, in the lowtemperature ranges, the predictions do not reflect the characteristics of the experimental findings (Talukder and Lee, 2018). Figure 10 illustrates the laminar flame speed for MD at two temperatures (423 and 473 K) and a pressure of 2 bar. Figure 11 reveals the laminar flame speed at a temperature of 473 K and pressures of 2, 4, and 6 bar. Some differences were observed between the reduced and detailed mechanisms in terms of the laminar flame speed results for MD, with the latter predicting greater results than the former. The results of model predictions show a good agreement with the experimental results, with a difference of less than 10%. Thus, the predictions of the reduced mechanism can be used in the calculation of the MD oxidation process.

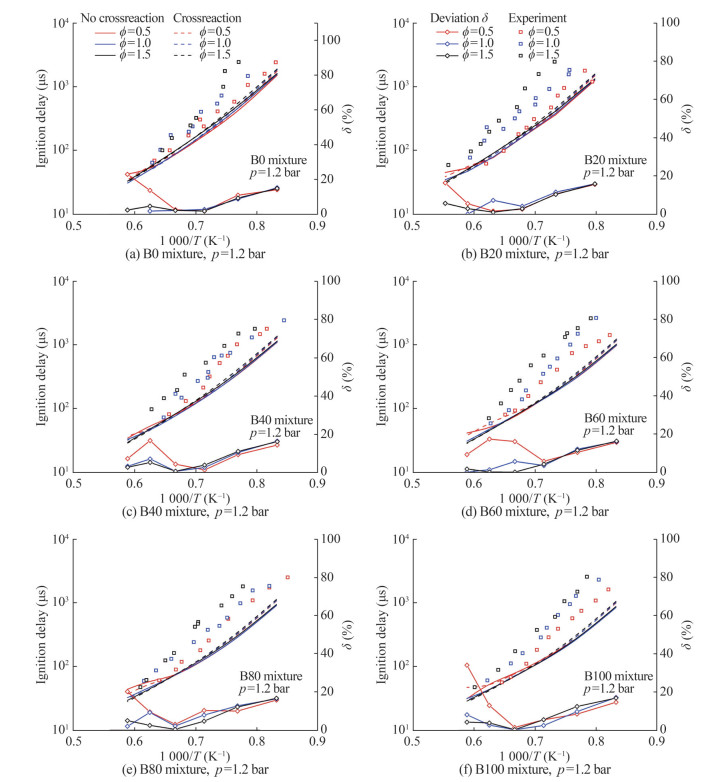

3.3 Verification of n-heptane/MD mechanism

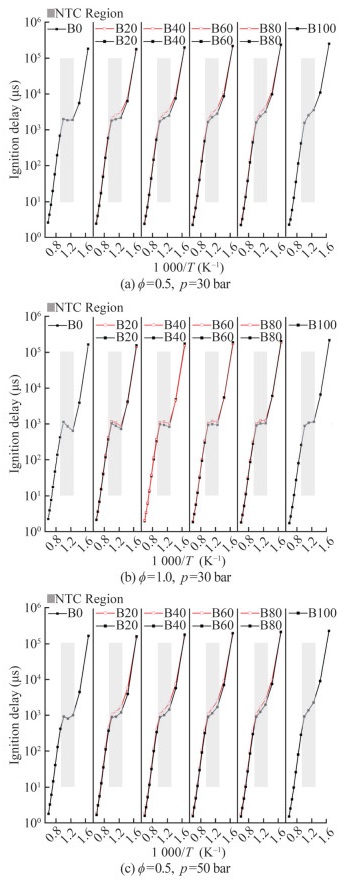

Biodiesel research has been focused on engine performance at different biodiesel replacement rates. In this study, the predictions of ignition delay time at various MD substitution rates (B0, B20, B40, B60, B80, and B100) during the oxidation process of n-heptane/MD blends were calculated. Figure 12 presents the reduced-mechanism predictions with and without cross-reactions against experimental values and the relative error between predictions. The symbols represent the experimental results from another work (Hoang and Thi, 2015), the lines correspond to model predictions, the solid lines indicate the results of the without cross-reactions model (Model Ⅰ), and the dashed lines are those obtained with cross-reaction model (Model Ⅱ) findings. Experimental and prediction results were obtained at equivalence ratios of 0.5–1.5 and a pressure of 1.2 bar. The findings follow the same trend at different substitution ratios, with the ignition delay time decreasing with temperature and the equivalence ratios increasing. Comparison of the simulation results of Models Ⅰ and Ⅱ at ϕ=1.5 and T= 1 600 K revealed the inconsistency in the different substitution ratios of biodiesel. The experimental findings are consistent with the prediction trends, and the results of Model Ⅱ are more accurate than those of Model Ⅰ.

In this study, relative deviations (δ) were calculated based on the ignition delay time of Models Ⅰ and Ⅱ. The δ were used to evaluate the effect of cross-reactions on ignition delay time (Eq. (7)). τcross and τnocross denote the ignition delay times of the reduced mechanism with and without cross-reactions, respectively. The point lines in Figure 12 show the variation pattern of δ at different temperatures and equivalent ratios. Figure 12 shows that δ was mostly influenced by the initial temperature, and the temperature determines the trend of δ. At the equivalence ratio of 1.5, Model Ⅰ had an inaccurate result in the prediction of the high-temperature combustion characteristics of the blends. The overall trend of δ decreased with the increase in the temperature, which is consistent with the cross-reactions that mainly occurred at intermediate-temperature ranges.

$$ \delta=\left|\left(\tau_{\text {cross }}-\tau_{\text {nocross }}\right) / \tau_{\text {nocross }}\right| \times 100 \% $$ (7) 4 Influence of cross-reaction on the oxidation process

4.1 Prediction of n-heptane/MD oxidation

Additional ignition delay time predictions using Models Ⅰ and Ⅱ were required to investigate the influence of cross-reaction in the n-heptane/MD oxidation process. Figure 12 shows the crucial effect of the addition of cross-reactions on the oxidation process of blends at various substitution ratios. This study was carried out using Models Ⅰ and Ⅱ to predict the ignition delay time under different substitution ratio, temperature, pressure, and equivalence ratio conditions. Table 3 shows the conditions for prediction, which cover a wide range of temperature and pressure conditions. The results under different temperatures, pressures, equivalence ratios, and substitution ratios were obtained and used to form the prediction map.

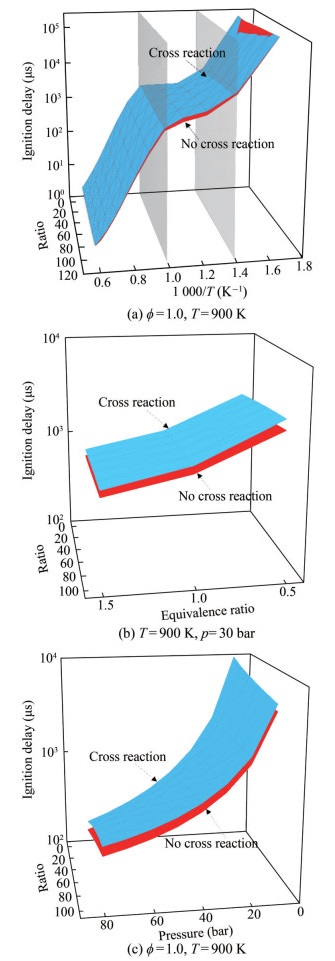

Table 3 Prediction conditionsSubstitution ratio of biodiesel T (K) p (bar) ϕ B0-B100 600–1 700 10–80 0.5–1.5 Figure 13 illustrates the ignition delay time with and without cross-reactions for B0-B100 at different temperatures, pressures, and equivalence ratios: (a) X: substitution ratio, Y: temperature; (b) X: substitution ratio, Y: equivalence ratio; (c) X: substitution ratio, Y: pressure. Figure 13(a) shows that the ignition delay time decreased with the increase in the temperature. Moreover, the trend was mainly influenced by temperature variation and with a minimal relation to the biodiesel substitution ratio. The prediction is generally longer when considering the cross-reaction of n-heptane/MD. The relative deviations in the predictions of Models Ⅰ and Ⅱ increased and then decreased with the increase in the temperature and were mainly concentrated in the intermediate-temperature range (700 ‒ 1 000 K), especially at 900 K. Figures 13(b) and 13(c) show the predictions for n-heptane/MD at various equivalence ratio and pressure conditions. The predictions of Models Ⅰ and Ⅱ reveal that the ignition delay time decreased as the pressure and equivalence ratio increased. The predictions of different MD substitution ratios followed the same trend. Combining Figures 13(a), 13(b), and 13(c), the cross-reaction for the n-heptane/MD oxidation process mainly affected the NTC region, which led to an increase in the ignition delay time.

Different substitution ratios of MD had different effects on the combustion characteristics. The NTC of cross-reactions at different temperatures, pressures, and equivalence ratios was investigated to optimize the oxidation process of diesel/biodiesel (Figure 14). Figure 14 shows that the ignition delay time first increased with the increase in the MD substitution rate at 600–1 000 K and then decreased with the increase in the MD substitution rate at temperatures above 1 000 K. In addition, the cross-reactions increased the ignition delay time in the NTC region. As illustrated in Figures 14(a) and 14(c), the increase in ignition delay time after the addition of the cross-reaction occurred in the region of 700–1 000 K, and the increase in pressure did not change the temperature region. Figure 14(b) shows that the NTC region affected by cross-reactions occurred mainly in the range of 800–1 000 K, which increased the equivalence ratio and reduced the cross-reaction region. Thus, the crossreactions were mainly controlled by the temperature, and the increased equivalence ratio decreased the cross-reaction effect.

According to the experiments, the B20 concentration blend exhibited a better performance in reducing emissions and lowering brake-specific fuel consumption (Şener, 2021). This concentration is the most commonly used substitution ratio of biodiesel and shows considerable potential (Lu and Chai, 2011). Therefore, subsequent studies were conducted to analyze the fuel oxidation process for the blend. Especially, the NTC region was most affected by the cross-reactions.

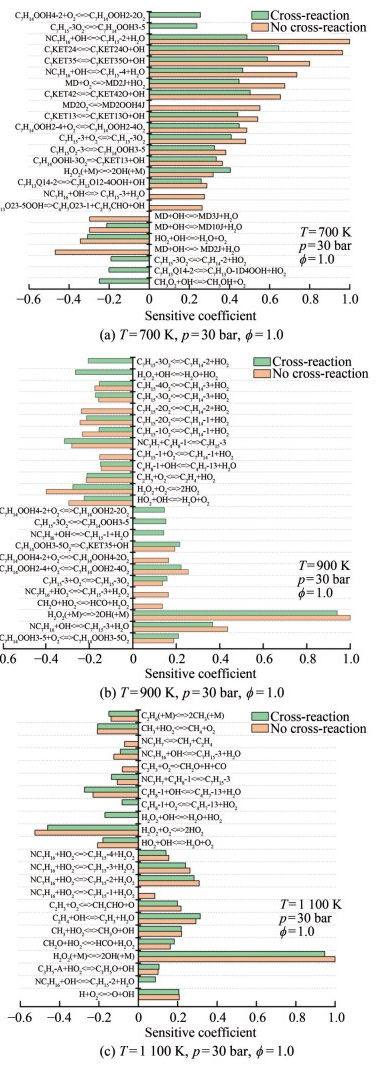

4.2 Sensitivity analysis with and without cross-reaction

Figure 15 shows the results of the sensitivity analysis of ignition delay time under different reaction initial conditions. Figure 15(a) indicates that the cross-reactions decreased the reactivity of n-heptane/MD. The addition of cross-reactions affected the dominant reaction, which in turn showed a greater effect on the ignition delay time. The reactivity of n-heptane/MD was affected by cross-reactions. NC7H16+OH < =>C7H16-2+H2O was the most important reaction, with a sensitivity coefficient of less than 50% of that without cross-reactions. The contribution of MD consumption reaction to ignition decreased at 700 K when cross-reactions were added. The cross-reaction increased the OH consumption pathway, especially for the n-heptane intermediate oxidation product C7H15-3O2. The reaction C7H15-3O2 < =>C7H14-2+HO2 caused an increase in HO2 production, which in turn increased the OH consumption through the reaction HO2+OH < =>H2O+O2. As a result, the H extraction reaction of n-heptane by OH was inhibited. The depletion reaction of CH3O2 on OH and the decomposition of C7H13Q14-2 to form HO2 reactions also increased the OH depletion pathway to some extent, which increased the ignition delay time.

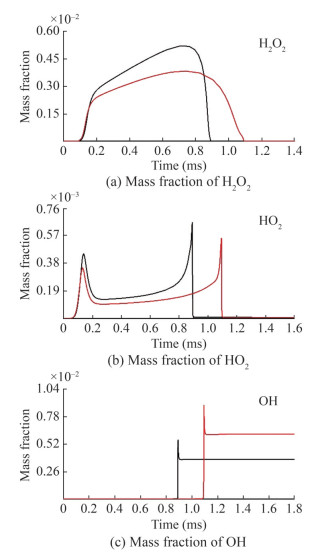

Figure 15(b) shows that the dominant reaction of ignition delay time was H2O2(+M) < =>2OH(+M), which was not considerably affected by the addition of cross-reactions. The increase in ignition delay time (Figure 14) in the presence of added cross-reactions at 900 K was mainly influenced by the following reactions: C7H15-3O2 < => C7H14-2+HO2 and HO2+OH < =>H2O+O2. The above reactions increased the pathway to produce HO2, which resulted in OH consumption. The addition of cross-reactions also reduced the importance of the H2O2 generation reaction in the ignition process. In addition to the above reactions, the depletion reaction of n-heptane, NC7H16+OH < =>C7H15-1+ H2O, and the isomerization of the intermediate oxidation production C7H15-3O2 < =>C7H14OOH3-5 influenced the increase in the ignition delay time.

According to Figure 14(a), the effect of cross-reaction on the ignition delay time was tremendously reduced at 1 000 K. Figure 15(c) reveals that the number of different reactions present in the comparison of the results for conditions with and without cross-reaction decreased. The two reactions with the greatest influence on the ignition delay time are of equal importance: H2O2(+M) < =>2OH(+M), H2O2+O2 < =>2HO2. H2O2+OH < =>H2O+HO2, which consumes OH to produce HO2, is a possible contributing factor to the increase in the ignition delay time.

As displayed in Figure 15, the cross-reaction worked mainly in the intermediate-temperature range and greatly affected the ignition delay time. The cross-reactions mainly contributed to a slow rate of n-heptane/MD consumption and increased the intermediate-product consumption pathway, HO2 production, and OH consumption pathway. The following cross-reaction analysis was performed pm the production and consumption of reactants, intermediates, and small-molecule radicals. All concentration variation data results were obtained at T=900 K, p=30 bar, and ϕ=1.0.

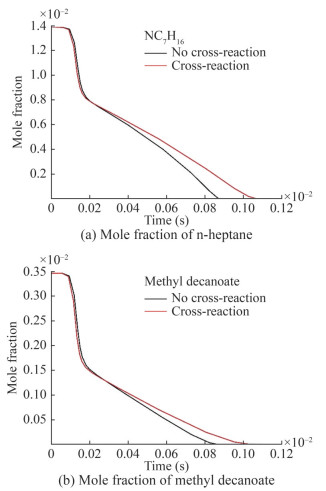

4.3 Mass fraction analysis of key species with and without cross-reaction

Figures 16(a) and 16(b) show the changes in n-heptane and MD concentrations, respectively, after cross-reaction addition and comparison with the mechanism without cross-reaction. The initial consumption rate of n-heptane and MD decreased after the addition of the cross-reaction compared with the case without it. The increase in the time required to complete the oxidation of n-heptane and MD is consistent with the results derived from Figure 15. This finding indicates the inhibitory effect of the crossreaction on reactant consumption.

Figure 17 illustrates the changes in the concentrations of some intermediate products of n-heptane/MD. The main components of the cross-reaction included the dehydrogenation and oxidation products of the reactants. The changes in the concentrations of the intermediate products must be analyzed to gain insights into the cross-reaction. N-heptane dehydrogenation produced produced C7H15-3 and C7H15-4, which were minimally affected by the cross-reaction. The concentrations of C7H15-1 and C7H15-2 decreased, demonstrating the inhibitory effect of the cross-reaction on n-heptane consumption. Analysis of the concentration of n-heptane oxidation products showed an increase in the concentration of C7H15-3O2, which is consistent with the results in Figure 15 and a decrease in the concentration of C7H15-1O2, which is less significant than that observed with the cross-reaction.

Figures 17(b) and 17(d) show the concentration change of the MD dehydrogenation and oxidation products. The results of sensitivity analysis indicate the weak contribution of MD to the ignition. The effect of cross-reaction on MD was mainly manifested as the inhibition of the consumption reaction of MD, which delayed the reaction of MD.

Figure 18 illustrates the changes in the concentrations of the free radicals H 2O2, HO2, and OH. Figure 15 shows that H 2O2(+M) < =>2OH(+M) is the dominant reaction affecting the ignition delay time, and the study of the variation in radical concentration is essential to understanding the crossreaction. The decomposition of H2O2 caused a large production of OH. However, the cross-reaction and the depletion reaction HO2+OH < =>H2O+O2 promoted the HO2 production and OH depletion pathways, respectively. In addition, the cross-reaction showed an inhibitory effect on the production of H2O2, HO2, and OH.

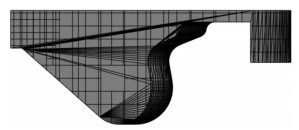

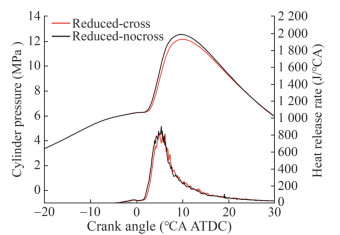

4.4 Comparison of detailed and reduced mechanism with and without cross-reaction

To compare the effects of mechanisms with and without cross-reaction of engine combustion, we embedded both mechanisms into the 3D-CFD simulation software. A combustion chamber model was constructed (Figure 19), and the compression and combustion processes were simulated. Tables 4 and 5 list the initial and temperature boundary conditions, respectively, at 25% engine load. Figure 20 shows the comparison results for the in-cylinder pressures and heat release rates obtained using the reduced mechanisms with and without cross-reaction when the percentages of n-heptane and MD in the blended fuel were 80% and 20%, respectively. Figure 20 reveals the applicability of the developed mechanisms to the simulation of the combustion process of dual-fuel engines fueled with diesel and biodiesel. The peak values of in-cylinder pressure and HRR of the cross-reaction mechanism were slightly lower, and the peak phase was later than that of the mechanism without cross-reactions. Small differences occurred because the cross-reaction reduced the consumption rate of n-heptane and MD, which increased the ignition delay time.

Table 4 Initial condition of the engine at 25% loadParameter Value Speed (r/min) 1 134 Torque (N·m) 439 Inlet flow (kg/h) 94.3 Fuel flow (kg/h) 0.42 Inject timing (℃A BTDC) 10.5 Table 5 Temperature boundary condition of the engine at 25% loadParameter Value (K) Cylinder head 380 Cylinder wall 390 Piston 410 Initial gas 371.82 5 Conclusions

In this study, the detailed mechanisms of n-heptane and MD were reduced via DRG, DRGEP, and FSSA, and the cross-reactions were added to the merged reduced mechanism of n-heptane/MD. The mechanisms were validated based on published experimental results on ignition delay time and laminar flame speed. The ignition delay time properties of the reduced n-heptane/MD mechanism were validated using the experiment results on various concentrations of diesel/biodiesel blends. In addition, multicase ignition delays were predicted under the parameter matrix to establish prediction maps with and without cross-reactions. Finally, sensitivity and concentration analyses were carried out to characterize the role of cross-reactions and identify the dominant reaction and species on the n-heptane/MD oxidation process. The main conclusions can be summarized as follows:

1) The reduced n-heptane/MD mechanism with crossreactions consisting of 800 reactions and 288 species was developed. At the conditions of T=1 200 – 1 700 K, p= 1.2 bar, ϕ=0.5–1.5 and B0-B100, compared with the experimental results on diesel and biodiesel, the reduced mechanism with cross-reactions was more accurate than that without.

2) The prediction maps of ignition delay time with various MD substitution ratios and initial conditions illustrate that the addition of the MD decreased the ignition delay time at low-temperature conditions of 600–1 000 K and increased it at high-temperature conditions (1 000–1 700 K).

3) The cross-reaction was mainly controlled by temperature, and at low-to-medium temperatures, cross-reactions had a noticeable effect on the oxidation reaction of n-heptane/MD at 700–1 000 K. The effect range of cross-reactions slightly widened with the increase in the pressure. Increasing the mixture concentration from ϕ=0.5 to ϕ=1.0 inhibited the cross-reaction. Therefore, the temperature range of the cross-reaction effect was narrowed to 800– 1 000 K.

4) Cross-reactions slowed down the consumption rates of n-heptane and MD and increased the generation times of OH, HO2, and H2O2, which directly account for the increased ignition delay time and reduced reactivities of the blends.

5) The 3D-CFD simulation findings on the dual-fuel engine fueled with diesel and biodiesel using the reduced mechanisms with and without cross-reaction showed that the developed reduced mechanism model can reflect well the effect of cross-reaction on the combustion process in internal combustion engines.

Competing interest The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.Supplementary InformationThe online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s11804-025-00634-3 -

Table 1 Scales of detailed and reduced mechanisms

Fuel Mechanism Species Reactions N-heptane Detailed mechanism (Zhang et al., 2016) 1 269 5 336 Reduced mechanism 128 593 Methyl decanoate Detailed mechanism (Sarathy et al., 2011) 621 2 998 Reduced mechanism 271 990 Table 2 Analysis conditions

Substitution condition T (K) p (bar) ϕ N-heptane and MD 600–1 500 10–30 0.5–1.5 Table 3 Prediction conditions

Substitution ratio of biodiesel T (K) p (bar) ϕ B0-B100 600–1 700 10–80 0.5–1.5 Table 4 Initial condition of the engine at 25% load

Parameter Value Speed (r/min) 1 134 Torque (N·m) 439 Inlet flow (kg/h) 94.3 Fuel flow (kg/h) 0.42 Inject timing (℃A BTDC) 10.5 Table 5 Temperature boundary condition of the engine at 25% load

Parameter Value (K) Cylinder head 380 Cylinder wall 390 Piston 410 Initial gas 371.82 -

Abbaszaadeh A, Ghobadian B, Omidkhah MR, Najafi G (2012) Current biodiesel production technologies: A comparative review. Energy Conversion and Management 63: 138–148. DOI: 10.1016/j.enconman.2012.02.027 Adewale P, Dumont MJ, Ngadi M (2015) Recent trends of biodiesel production from animal fat wastes and associated production techniques. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 45: 574–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2015.02.039 Ambat I, Srivastava V, Sillanpää M (2018) Recent advancement in biodiesel production methodologies using various feedstock: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 90: 356–369. DOI: 10.1016/j.rser.2018.03.069 Andrae J, Johansson D, Björnbom P, Risberg P, Kalghatgi G (2005) Co-oxidation in the auto-ignition of primary reference fuels and n-heptane/toluene blends. Combustion and Flame 140(4): 267–286. DOI: 10.1016/j.combustflame.2004.11.009 Andrae JCG, Björnbom P, Cracknell RF, Kalghatgi GT (2007) Autoignition of toluene reference fuels at high pressures modeled with detailed chemical kinetics. Combustion and Flame 149(1–2): 2–24. DOI: 10.1016/J.COMBUSTFLAME.2006.12.014 Banković-Ilić IB, Stamenković OS, Veljković VB (2012) Biodiesel production from non-edible plant oils. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 16(6): 3621–3647. DOI: 10.1016/j.rser.2012.03.002 Basha SA, Gopal KR, Jebaraj S (2009) A review on biodiesel production, combustion, emissions and performance. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 13(6): 1628–1634. DOI: 10.1016/j.rser.2008.09.031 Chen J, Li J, Dong W, Zhang X, Tyagi RD, Drogui P, Surampalli RY (2018) The potential of microalgae in biodiesel production. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 90: 336–346. DOI: 10.1016/j.rser.2018.03.073 Chisti Y (2007) Biodiesel from microalgae. Biotechnology Advances 25(3): 294–306. DOI: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.02.001 Ciezki HK, Adomeit G (1993) Shock-tube investigation of self-ignition of n-heptane-air mixtures under engine relevant conditions. Combustion and Flam 93(4): 421–433. DOI: 10.1016/0010-2180(93)90142-P Curran HJ, Gaffuri P, Pitz WJ, Westbrook CK (1998) A comprehensive modeling study of n-heptane oxidation. Combustion and Flame 114(1–2): 149–177. DOI: 10.1016/S0010-2180(97)00282-4 de Araújo CDM, de Andrade CC, e Silva ES, Dupas FA (2013) Biodiesel production from used cooking oil: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 27: 445–452. DOI: 10.1016/j.rser.2013.06.014 Diévart P, Won SH, Dooley S, Dryer FL, Ju Y (2012) A kinetic model for methyl decanoate combustion. Combustion and Flame 159(5): 1793–1805. DOI: 10.1016/j.combustflame.2012.01.002 Dirrenberger P, Glaude PA, Bounaceur R, Le Gall H, Da Cruz AP, Konnov AA (2014) Laminar burning velocity of gasolines with addition of ethanol. Fuel 115: 162–169. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2013.07.015 Gaïl S, Thomson MJ, Sarathy SM, Syed SA, Dagaut P, Diévart P, Marchese AJ, Dryer FL (2007) A wide-ranging kinetic modeling study of methyl butanoate combustion. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 31(1): 305–311. DOI: 10.1016/j.proci.2006.08.051 Gong Y, Jiang M (2011) Biodiesel production with microalgae as feedstock: from strains to biodiesel. Biotechnology Letters 33(7): 1269–1284. DOI: 10.1007/s10529-011-0574-z Han WQ, Yao CD (2015) Research on high cetane and high octane number fuels and the mechanism for their common oxidation and auto-ignition. Fuel 150: 29–40. DOI: 1016/j.fuel.2015.01.090 https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.fuel.2015.01.090 Herbinet O, Pitz WJ, Westbrook CK (2008) Detailed chemical kinetic oxidation mechanism for a biodiesel surrogate. Combustion and Flame 154(3): 507–528. DOI: 10.1016/j.combustflame.2008.03.003 Heufer KA, Olivier H (2010) Determination of ignition delay times of different hydrocarbons in a new high pressure shock tube. Shock Wave 20(4): 307–316. DOI: 10.1007/s00193-010-0262-2 Hoang VN, Thi LD (2015) Experimental study of the ignition delay of diesel/biodiesel blends using a shock tube. Biosystems Engineering 134: 1–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2015.03.009 Kelly AP, Smallbone AJ, Zhu DL, Law CK (2011) Laminar flame speeds of C5 to C8 n-alkanes at elevated pressures: Experimental determination, fuel similarity, and stretch sensitivity. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 33(1): 963–970. DOI: 10.1016/j.proci.2010.06.074 Kumar K, Sung CJ (2016) Autoignition of methyl butanoate under engine relevant conditions. Combustion and Flame 171: 1–14. DOI: 10.1016/j.combustflame.2016.04.011 Lahane S, Subramanian KA (2015) Effect of different percentages of biodiesel–diesel blends on injection, spray, combustion, performance, and emission characteristics of a diesel engine. Fuel 139: 537–545. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2014.09.036 Li R, He G, Qin F, Wei X, Zhang D, Wang Y, Liu B (2019) Development of skeletal chemical mechanisms with coupled species sensitivity analysis method. Journal of Zhejiang University-SCIENCE A 20(12): 908–917. DOI: 10.1631/jzus.A1900388 Liang L, Stevens JG, Farrell JT (2009) A dynamic adaptive chemistry scheme for reactive flow computations. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 32(1): 527–534. DOI: 10.1016/j.proci.2008.05.073 Liu H, Huo M, Liu Y, Wang X, Wang H, Yao M, Lee CF (2014a) Time-resolved spray, flame, soot quantitative measurement fueling n-butanol and soybean biodiesel in a constant volume chamber under various ambient temperatures. Fuel 133: 317–325. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2014.05.038 Liu H, Wang X, Zheng Z, Gu J, Wang H, Yao M (2014b) Experimental and simulation investigation of the combustion characteristics and emissions using n-butanol/biodiesel dual-fuel injection on a diesel engine. Energy 74: 741–752. DOI: 10.1016/j.energy.2014.07.041 Liu Z, Yang L, Song E, Wang J, Zare A, Bodisco TA, Brown RJ (2021) Development of a reduced multi-component combustion mechanism for a diesel/natural gas dual fuel engine by cross-reaction analysis. Fuel 293: 120388. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.120388 Lu M, Chai M (2011) Experimental Investigation of the Oxidation of Methyl Oleate: One of the Major Biodiesel Fuel Components. Synthetic Liquids Production and Refining 1084: 289–312. DOI: 10.1021/bk-2011-1084.ch013 Lu T, Law CK (2006) On the applicability of directed relation graphs to the reduction of reaction mechanisms. Combustion and Flame 146(3): 472–483. DOI: 10.1016/j.combustflame.2006.04.017 Math MC, Kumar SP, Chetty S V (2010) Technologies for biodiesel production from used cooking oil—A review. Energy for Sustainable Development 14(4): 339–345. DOI: 10.1016/j.esd.2010.08.001 McCarthy P, Rasul MG, Moazzem S (2011) Analysis and comparison of performance and emissions of an internal combustion engine fuelled with petroleum diesel and different bio-diesels. Fuel 90(6): 2147–2157. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2011.02.010 Meng X, Yang J, Xu X, Zhang L, Nie Q, Xian M (2009) Biodiesel production from oleaginous microorganisms. Renewable Energy 34(1): 1–5. DOI: 10.1016/j.renene.2008.04.014 Mishra VK, Goswami R (2018) A review of production, properties and advantages of biodiesel. Biofuels 9(2): 273–289. DOI: 10.1080/17597269.2017.1336350 Mubarak M, Shaija A, Suchithra T V (2015) A review on the extraction of lipid from microalgae for biodiesel production. Algal Research 7: 117–123. DOI: 10.1016/j.algal.2014.10.008 Narendranathan SK, Sudhagar K (2014) Study on performance & emission characteristic of CI engine using biodiesel. Advanced Materials Research 984: 885–892. DOI: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.984-985.885 Noor CWM, Noor MM, Mamat R (2018) Biodiesel as alternative fuel for marine diesel engine applications: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 94: 127–142. DOI: 10.1016/j.rser.2018.05.031 Oo CW, Shioji M, Kawanabe H, Roces SA, Dugos NP (2014) A skeletal kinetic model for biodiesel fuels surrogate blend under diesel-engine conditions. 2014 International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment and Management (HNICEM), 1–6. DOI: 10.1109/HNICEM.2014.7016258 Patel RL, Sankhavara CD (2017) Biodiesel production from Karanja oil and its use in diesel engine: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 71: 464–474. DOI: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.12.075 Pepiot-Desjardins P, Pitsch H (2008) An efficient error-propagation-based reduction method for large chemical kinetic mechanisms. Combustion and Flame 154(1): 67–81. DOI: 10.1016/j.combustflame.2007.10.020 Pitz WJ, Mueller CJ (2011) Recent progress in the development of diesel surrogate fuels. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 37(3): 330–350. DOI: 10.1016/j.pecs.2010.06.004 Qi DH, Geng LM, Chen H, Bian YZH, Liu J, Ren XCH (2009) Combustion and performance evaluation of a diesel engine fueled with biodiesel produced from soybean crude oil. Renewable Energy 34(12): 2706–2713. DOI: 10.1016/j.renene.2009.05.004 Ramos M, Dias AP, Puna JF, Gomes J, Bordado JC (2019) Biodiesel Production Processes and Sustainable Raw Materials. Energies 12(23): 4408. DOI: 10.3390/en12234408 Santori G, Di Nicola G, Moglie M, Polonara F (2012) A review analyzing the industrial biodiesel production practice starting from vegetable oil refining. Applied Energy 92: 109–132. DOI: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2011.10.031 Sarathy SM, Thomson MJ, Pitz WJ, Lu T (2011) An experimental and kinetic modeling study of methyl decanoate combustion. Proceedings of the Combustion Institute 33(1): 399–405. DOI: 10.1016/j.proci.2010.06.058 Şener R (2021) Experimental and Numerical Analysis of a Waste Cooking Oil Biodiesel Blend used in a CI Engine. International Journal of Advances in Engineering and Pure Sciences 33(2): 299–307. DOI: 10.7240/jeps.829006 Sherbaz S, Duan W (2012) Operational Options for Green Ships. Journal of Marine Science and Application 11(3): 335–340. DOI: CNKI:SUN:HEBD.0.2012-03-013 https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11804-012-1141-2 Su W, Huang H (2005) Development and calibration of a reduced chemical kinetic model of n-heptane for HCCI engine combustion. Fuel 84(9): 1029–1040. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2005.01.015 Talukder N, Lee KY (2018) Laminar flame speeds and Markstein lengths of methyl decanoate-air premixed flames at elevated pressures and temperatures. Fuel 234: 1346–1353 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2018.08.017 Van TC, Ramirez J, Rainey T, Ristovski Z, Brown RJ (2019) Global impacts of recent IMO regulations on marine fuel oil refining processes and ship emissions. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 70: 123–134. DOI: 10.1016/j.trd.2019.04.001 Vasudev A, Mikulski M, Balakrishnan PR, Storm X, Hunicz J (2022) Thermo-kinetic multi-zone modelling of low temperature combustion engines. Progress in Energy and Combustion Science 91: 100998. DOI: 10.1016/j.pecs.2022.100998 Veljković VB, Biberdžić MO, Banković-Ilic IB, Djalović IG, Tasić MB, Nježić ZB, Stamenković OS (2018) Biodiesel production from corn oil: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 91: 531–548. DOI: 10.1016/j.rser.2018.04.024 Wang C, Zhong X, Liu H, Song T, Wang H, Yang B, Yao M (2023) Experimental and kinetic modeling studies on oxidation of n-heptane under oxygen enrichment in a jet-stirred reactor. Fuel 332: 126033. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2022.126033 Wang X, Yao M, Li S, Gu J (2013) Experimental and modeling study of biodiesel surrogates combustion in a CI engine. SAE Technical Papers 2013-01-1130. DOI: 10.4271/2013-01-1130 Wu F, Wang J, Chen W, Shuai S (2009) A study on emission performance of a diesel engine fueled with five typical methyl ester biodiesels. Atmospheric Environment 43(7): 1481–1485. DOI: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2008.12.007 Wu G, Jiang G, Yang Z, Wei H, Huang Z (2019) Experimental study on the emission reduction mechanism of biodiesel used in marine diesel engine. Journal of Marine Science and Application 40(3): 468–476. DOI: 10.11990/jheu.201710061 Xiao J, Zhang B, Zheng ZL (2017) Development and validation of a reduced chemical kinetic mechanism for HCCI engine of biodiesel surrogate. Wuli Huaxue Xuebao/Acta Physico-Chimica Sinica 33(9): 1752–1764. DOI: 10.3866/PKU.WHXB201704273 Yang L, Zare A, Bodisco TA, Nabi N, Liu Z, Brown RJ (2021) Analysis of cycle-to-cycle variations in a common-rail compression ignition engine fuelled with diesel and biodiesel fuels. Fuel 290: 120010. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.120010 Yang Z, Wei H, He X, Li J, Liu H (2016) Application of biodiesel in a marine diesel engine. Journal of Marine Science and Application 37(1): 71–75. DOI: 10.11990/jheu.201411021 Zhang E, Liang X, Zhang F, Yang P, Cao X, Wang X, Yu H (2019) Evaluation of Exhaust Gas Recirculation and Fuel Injection Strategies for Emission Performance in Marine Two-Stroke Engine. Energy Procedia 158: 4523–4528. DOI: 10.1016/j.egypro.2019.01.872 Zhang K, Banyon C, Bugler J, Curran HJ, Rodriguez A, Herbinet O, Battin-Leclerc F, B'Chir C, Heufer KA (2016) An updated experimental and kinetic modeling study of n-heptane oxidation. Combustion and Flame 172: 116–135. DOI: 10.1016/j.combustflame.2016.06.028 Zhang Y, Dubé MA, McLean DD, Kates M (2003) Biodiesel production from waste cooking oil: 1. Process design and technological assessment. Bioresource Technology 89(1): 1–16. DOI: 10.1016/S0960-8524(03)00040-3 Zheng Z, Xia M, Liu H, Shang R, Ma G, Yao M (2018) Experimental study on combustion and emissions of n-butanol/biodiesel under both blended fuel mode and dual fuel RCCI mode. Fuel 226: 240–251. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2018.03.151 Zheng Z, Yao M (2006) Numerical study on the chemical reaction kinetics of n-heptane for HCCI combustion process. Fuel 85(17): 2605–2615. DOI: 10.1016/j.fuel.2006.05.005 Zulqarnain, Ayoub M, Yusoff MH, Nazir MH, Zahid I, Ameen M, Sher F, Floresyona D, Budi Nursanto E (2021) A Comprehensive Review on Oil Extraction and Biodiesel Production Technologies. Sustainability 13(2): 788. DOI: 10.3390/su13020788