Nonparametric Identification of Nonlinear Added Mass Moment of Inertia and Damping Moment Characteristics of Large-Amplitude Ship Roll Motion

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11804-020-00129-3

-

Abstract

This study aims to investigate the nonlinear added mass moment of inertia and damping moment characteristics of large-amplitude ship roll motion based on transient motion data through the nonparametric system identification method. An inverse problem was formulated to solve the first-kind Volterra-type integral equation using sets of motion signal data. However, this numerical approach leads to solution instability due to noisy data. Regularization is a technique that can overcome the lack of stability; hence, Landweber's regularization method was employed in this study. The L-curve criterion was used to select regularization parameters (number of iterations) that correspond to the accuracy of the inverse solution. The solution of this method is a discrete moment, which is the summation of nonlinear restoring, nonlinear damping, and nonlinear mass moment of inertia. A zero-crossing detection technique is used in the nonparametric system identification method on a pair of measured data of the angular velocity and angular acceleration of a ship, and the detections are matched with the inverse solution at the same discrete times. The procedure was demonstrated through a numerical model of a full nonlinear free-roll motion system in still water to examine and prove its accuracy. Results show that the method effectively and efficiently identified the functional form of the nonlinear added moment of inertia and damping moment.-

Keywords:

- Nonparametric identification ·

- Ship roll motion ·

- Nonlinear damping ·

- Added mass ·

- Inverse problem

Article Highlights• Results show that the proposed method effectively and efficiently identified the functional form of the nonlinear added mass moment of inertia and damping.• For the identification example, the proposed procedure was applied to the nonlinear differential equation of ship roll motion.• Most accidents and casualty losses occur due to the lack of understanding on the nonlinearity problem of the roll motion system that causes loss of stability. -

1 Introduction

In the shipbuilding and design industry, the ship dynamics and stability are important design principles that consider the pose and motion characteristics, including capsizing, of ships. Ship motions have six modes or degrees of freedom (i.e., surge, sway, heave, pitch, roll, and yaw). The roll mode has the greatest impact to the capsizing of ships. Most accidents and casualty losses occur due to the lack of understanding the nonlinearity problem of the roll motion system that causes loss of stability. Generally, the prediction methods of roll motion are used as the bases of the equation of motion (EOM) that is employed for determining the response of the roll mode. The EOM consists of the inertia, damping, restoring, and external load F (force or moment) terms, each term performing linear or nonlinear functions. The nonlinear system has more accuracy than the linear system. Hence, the prediction of the nonlinear roll motion system has received attention nowadays. The correction and accuracy of roll prediction depend on the coefficient values or functions of the EOM.

In recent years, many researchers have examined nonlinear characteristics of ship roll motion through experiments and mathematical modeling. For example, Cotton and Spyrou (2001) studied the nonlinear behavior of roll mode and capsizing via experiments. Wassermann et al. (2016) proposed an estimation method of ship roll damping of the decay and harmonic excited roll motion technique for a panamax container ship. Oliva-Remola et al. (2018) proposed an estimation method of damping through internally excited roll motion tests. Haddara and Wu (1993) proposed a parameter identification method of nonlinear roll motion in random seas. Taylan (1999) found the solution of the nonlinear roll model by a generalized asymptotic analysis. Jang et al. (2011b), Kianejad et al. (2019), and Irkal et al. (2019) published articles about the prediction of ship roll damping motion via computational fluid dynamics method. Mancini et al. (2018) published Verification and validation of numerical modeling of DTMB 5415 roll decay. Sathyaseelan et al. (2017) introduced an efficient Legendre wavelet spectral method to the ship roll motion model to investigate nonlinear damping coefficients. Lastly, Jang et al. (2009b) established a novel procedure to identify the functional form of nonlinear restoring forces in a nonlinear oscillatory motion of a conservative system.

Nowadays, the identification of nonlinear system methods has received great attention from many researchers. It has been applied to various branches of science and engineering, particularly in vibration and motion analysis field. The main objective of this method is to obtain a mathematical model based on the requirement of measured data. However, the related studies only considered the nonlinear restoring force or damping force or the simultaneous identification of both, whereas some studies proposed a simultaneous identification method of nonlinear damping and excitation force characteristics (Jang et al., 2011a; Jang, 2013).

Some identification methods for nonlinear restoring force were presented by Masri et al. (1993), Chassiakos and Marsi (1996), and Liang et al. (1997, 2001), who preferred identification based on neural networks. Spina et al. (1996) preferred the nonlinear system identification method from transient data using the Gabor transform based on the application of the Hilbert transform. Moreover, Jang et al. (2009b) proposed a novel method for the nonparametric identification of nonlinear restoring forces in nonlinear vibrations from noisy response data based on the inverse problem. For damping identification only, Iourtchenko and Dimentberg (2002) proposed a procedure for the identification of the damping characteristic from measured stationary responses based on the stochastic averaging method, and Jang et al. (2010a) presented a recovering method for the functional form of nonlinear roll damping with a system identification method using measured response data from a real free-roll decay experiment. Other proponents of the damping identification method are Mohammad et al. (1992), Lazan (1968), Naprstek (1999), and Jang et al. (2010b). The nonlinear identification method can simultaneously identify two force terms of EOM. For instance, Jang (2011) proposed a nonparametric simultaneous identification of the nonlinear damping and restoring characteristics. Jang et al. (2011a) formulated a simultaneous identification method of the nonlinear damping and external harmonic excitation characteristics. Other authors who mentioned the system identification method are Jang et al. (2011b) and Park et al. (2014).

Despite these studies, nobody has examined the simultaneous identification of nonlinear inertia and damping terms based on inverse formalism with measured free decay response data. In fact, the roll motion of the floating body of a single degree of freedom (SDF) in free induction decay consists of acceleration, damping, and restoring moment terms. The nonlinear restoring and damping moments are upon a hull form that functions with the heel angle and angular velocity, respectively. However, the moment due to mass moment of inertia that functions with angular acceleration includes the mass moment of inertia of a floating body and added mass moment of inertia. The added mass moment of inertia is a constant value that is determined by logarithmic decrement (conventional method). Kianejad et al. (2019a, b) discovered the nonlinear behavior of added mass moment of inertia. These discoveries motivated the objective of this study.

The restoring moment can be identified through inclining tests or calculations. The two unknown load functions are added inertia and damping coefficients, and they are presented in this paper based on an inverse problem (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2002). The inverse problem seeks to solve an integral equation, which is transformed from nonlinear second-order differential equation and is equivalent to the Volterra-type integral equation of the first kind (Abdul-Majid, 2011). Generally, integral operators are stable, whereas differential operators are unstable. Hence, regularization has a crucial role to solve ill-posed problems, such as numerical instability. In this study, Landweber's regularization method was used to suppress the instability (Qinian, 2011) and the L-curve criteria to determine the optimal solution of the iteration number for the identification.

For the identification example, the proposed procedure was applied to a nonlinear differential equation of the ship roll motion. The numerical experiment reveals the workability of the proposed method for identifying a functional form of both the nonlinear damping and added mass force in a free-roll decay motion.

2 Principles and Theory

To determine a ship roll motion characteristic through the nonparametric identification method, we have to first understand the basics of ship motions and their governing equation (EOM). In reality, a ship simultaneously moves in six directions in a seaway (Volker, 2000), as shown in Figure 1. However, finding all motion characteristics is difficult. Therefore, determining only one direction, namely, SDF, helps reduce the complexity and difficulty. Second, the EOM of SDF is transformed as an integral equation, which has an unknown variable within an integral. Third, the unknown variable is solved via inverse problem formalism and stabilized by Landweber's regularization method. The optimal solution is chosen through the L-curve criterion. Finally, the results of the zero-crossing detection technique of measured data are compared with other solutions to identify the added mass moment of inertia and damping moment and then their nonlinear function formulated.

2.1 Ship Rolling and Its Governing Equation

Figure 2 shows an illustration of ship roll motion. It involves restoring moment, damping moment, and moment due to mass moment of inertia that functions with roll angle θ, angular velocity $ \dot{\theta} $, and acceleration $ \ddot{\theta} $, respectively. Normally, a small roll angle of less than 7°–8° (Anthony, 2008) is a linear system. However, in a real seaway, the roll angle should be higher and should have a nonlinear roll motion behavior.

The nonlinear rolling system is governed by a nonlinear EOM that is applied from ordinary differential equation (ODE), which is widely used in the ship motion field.

$$ I\ddot{\theta}+D\left(\dot{\theta}\right)+R\left(\theta \right)={M}_{\mathrm{ext}} $$ (1) where $ I\ddot{\theta} $ is the nonlinear moment due to mass moment of inertia function, $ D\left(\dot{\theta}\right) $ is the nonlinear damping moment function, R(θ) is the nonlinear restoring moment function, and Mext is the external moment function. I is composed of the mass moment of inertia of Ixx and added mass moment of inertia of the ship $ {I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}\right) $. The added mass moment of inertia is functioned with $ \ddot{\theta} $ because it easily identifies and formulates a recovery function.

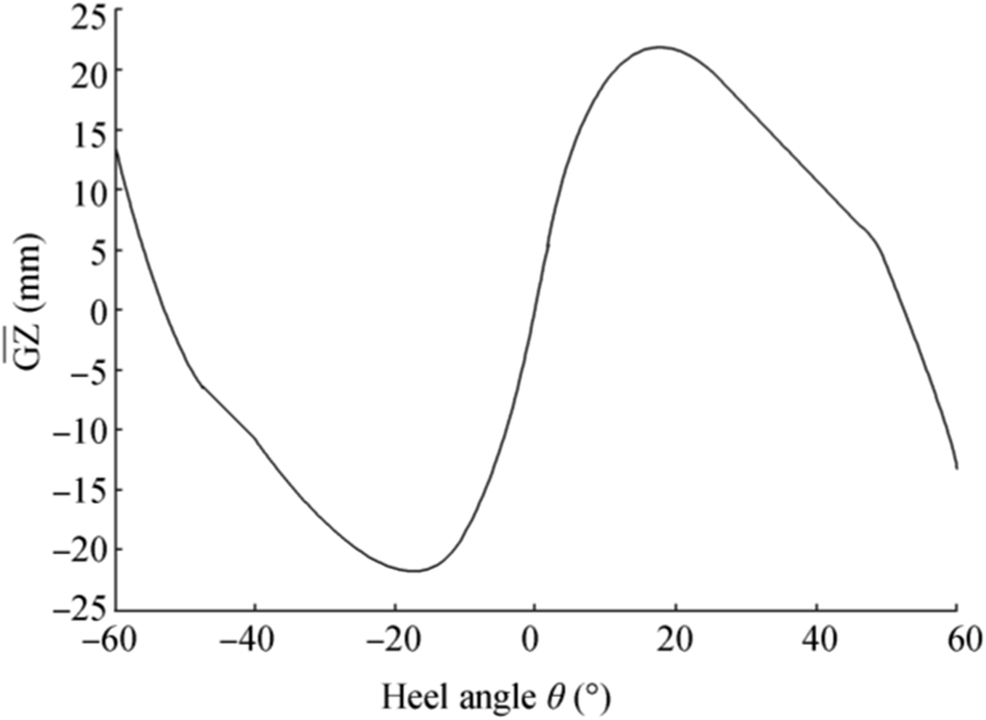

$$ I=\left({I}_{xx}+{I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}\right)\right) $$ (2) The function of the restoring moment of a ship can be rewritten in the form $ \overline{\mathrm{GZ}}\left(\theta \right) $ or, as shown in Eq. (3). Accordingly, $ \overline{\mathrm{GZ}}\left(\theta \right) $ is formulated from the $ \overline{\mathrm{GZ}} $ curve in Figure 3 by the curve fitting method with a polynomial function. Moreover, Δ is a ship displacement.

$$ R\left(\theta \right)=\overline{\mathrm{GZ}}\left(\theta \right)=\varDelta \overline{\mathrm{GM}}\left(\theta \right)\sin \theta $$ (3) By substituting Eqs. (2) and (3) into Eq. (1), the governing equation becomes

$$ \left({I}_{xx}+{I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}\right)\right)\ddot{\theta}+D\left(\dot{\theta}\right)+\varDelta \overline{\mathrm{GZ}}\left(\theta \right)={M}_{\mathrm{ext}} $$ (4) This study considers the free-roll decay motion method; thus, Mext = 0. By rearranging Eq. (4), the governing equation becomes

$$ {I}_{xx}\ddot{\theta}+ k\theta =-\left[{I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}\right)\ddot{\theta}+D\left(\dot{\theta}\right)+\varDelta \overline{\mathrm{GZ}}\left(\theta \right)\right]+ k\theta $$ (5) where kθ is the dummy restoring force, which is added to both sides of Eq. (5), and k is the dummy restoring coefficient value, which is an arbitrary constant value. Let us define

$$ F(t)=-\left[{I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}\right)\ddot{\theta}+D\left(\dot{\theta}\right)+\varDelta \overline{\mathrm{GZ}}\left(\theta \right)- k\theta \right] $$ (6) and substitute Eq. (6) into Eq. (5); hence, the governing equation becomes Eq. (7), with the initial values in Eq. (8).

$$ {I}_{xx}\ddot{\theta}+ k\theta =F(t) $$ (7) $$ \theta (0)=\alpha, \dot{\theta}(0)=\beta $$ (8) Base on the constant of variation concept, the solutions of Eq. (7) can be written as

$$ \theta ={v}_1{\theta}_1+{v}_2{\theta}_2 $$ (9) and

$$ \dot{\theta}={v}_1{\dot{\theta}}_1+{v}_2{\dot{\theta}}_2 $$ (10) θ1 and θ2 in Eq. (9) are the homogenous solution of Eq. (7), and v1 and v2 are the unknown variables. By differentiating Eq. (9), we can obtain

$$ \dot{\theta}=\left({\dot{v}}_1{\theta}_1+{v}_1{\dot{\theta}}_1\right)+\left({\dot{v}}_2{\theta}_2+{v}_2{\dot{\theta}}_2\right) $$ (11) Comparing Eqs. (10) and (11) yields the first condition on v1 and v2:

$$ {\dot{v}}_1{\theta}_1+{\dot{v}}_2{\theta}_2=0 $$ (12) Substituting Eqs. (9) and (10) into Eq. (7) yields the second condition on v1 and v2:

$$ {\dot{v}}_1{\dot{\theta}}_1+{\dot{v}}_2{\dot{\theta}}_2=\frac{F}{I_{xx}} $$ (13) Equations (12) and (13) are linear equations for $ {\dot{v}}_1 $ and $ {\dot{v}}_2 $, whose solutions are as follows:

$$ \left\{\begin{array}{c}{\dot{v}}_1\\ {}{\dot{v}}_2\end{array}\right\}={\left[\begin{array}{cc}{\theta}_1& {\theta}_2\\ {}{\dot{\theta}}_1& {\dot{\theta}}_2\end{array}\right]}^{-1}\left\{\begin{array}{c}0\\ {}\frac{F(t)}{I_{xx}W}\end{array}\right\}=\frac{F(t)}{I_{xx}W}\left\{\begin{array}{c}-{\theta}_2\\ {}{\theta}_1\end{array}\right\} $$ (14) where $ W={\theta}_1{\dot{\theta}}_2-{\dot{\theta}}_1{\theta}_2 $ is called the "Wronskian." The integration and substitution of Eq. (14) into Eq. (7) yield the integral equation form called "the Volterra-type integral equation of the first kind."

$$ \theta (t)=\frac{\alpha }{\mu }{\theta}_1(t)+\frac{\beta }{\nu }{\theta}_2(t)+\underset{0}{\overset{t}{\int }}\frac{\theta_1\left(\tau \right){\theta}_2(t)-{\theta}_1(t){\theta}_2\left(\tau \right)}{mW}F\left(\tau \right)\mathrm{d}\tau $$ (15) where θ1 and θ2 are chosen to ensure that they satisfy

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{I}_{xx}{\ddot{\theta}}_1+k{\theta}_1=0,{\theta}_1(0)=\mu, {\dot{\theta}}_1(0)=0,{}{I}_{xx}{\ddot{\theta}}_2+k{\theta}_2\\ \;\;=0,{\theta}_2(0)=0,{\dot{\theta}}_2(0)=\nu \end{array}} $$ (16) where the values of μ and ν are set to be a unit that make the coefficients of first and second terms in the right-hand side of Eq. (15) still equal to initial values as follows: μ = ν = 1 Eq. (8). Thus, the harmonic solutions of Eq. (16) are

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{\theta}_1=\cos \left(\omega t\right)\\ {}{\theta}_2=\frac{1}{\omega}\sin \left(\omega t\right)\end{array}} $$ (17) where $ \omega =\sqrt{\frac{k}{I_{xx}}} $ is the natural frequency that is a known value.

2.2 Integral Equation

To identify the two unknown quantities $ {I}_{xx}\left(\ddot{\theta}\right) $ and $ D\left(\dot{\theta}\right) $ that are embedded in F(t), Eq. (15) requires the measured system response data, where θ(t) and $ \dot{\theta}(t) $ and its initial conditions follow Eq. (8). For a systematic identification, the method requires a mathematical model that relates the response data to the known variables. Thus, rearranging Eq. (15) to Eq. (18) (Jang et al., 2010a; Jang, 2011) is the formulation for solving F

$$ \theta (t)-{\alpha \theta}_1(t)-{\beta \theta}_2(t)={\int}_0^tK\left(t,\tau \right)F\left(\tau \right)\mathrm{d}\tau $$ (18) where

$$ F\left(\tau \right)=-\left[{I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}\right)\ddot{\theta}+D\left(\dot{\theta}\right)+\varDelta \overline{\mathrm{GZ}}\left(\theta \right)- k\theta \right] $$ (19) and kernel K is defined as

$$ K\left(t,\tau \right)=\frac{\theta_1\left(\tau \right){\theta}_2(t)-{\theta}_1(t){\theta}_2\left(\tau \right)}{mW} $$ (20) The left-hand side of Eq. (18) is defined with a new variable, which is a known value from measured data and was called pseudo-displacement by Jang et al. (2011a):

$$ \eta (t)\equiv \theta (t)-{\alpha \theta}_1(t)-{\beta \theta}_2(t) $$ (21) Equation (18) is rewritten as

$$ \eta (t)={\int}_0^tK\left(t,\tau \right)F\left(\tau \right)\mathrm{d}\tau $$ (22) or can be rewritten in a symbolic form as

$$ \eta =L(F) $$ (23) where L is the linear integral operator (Jang et al., 2010b):

$$ L(F)={\int}_0^tK\left(t,\tau \right)F\left(\tau \right)\mathrm{d}\tau $$ (24) Equation (18) defines an inverse problem for the simultaneous identification of $ {I}_{xx}\left(\ddot{\theta}\right) $ and $ D\left(\dot{\theta}\right) $. It suffices to prove that its null space is trivial: If θ − αθ1 − βθ2 = 0, then F = 0. The proof is the same as that in Jang et al. (2009a) and shows that the equation has a unique solution.

2.3 Solving F by Landweber's Regularization Method

According to the integral equation mentioned above, the unknown F can be calculated under the assumption that η is a continuous function on the time domain, but in fact, the measured data are discrete data: The data are sampled in each time level and have noise. Thus, the noisy data cause the ill-posed problems, the integral equation that makes their solutions lack stability: a small amount of noisy data may amplify a large noisy solution error.

To fix the ill-posed problems, regularization (a stabilization) is used to inhibit the instability. At present, many regularization methods have been used to fix ill-posed problems; the present study has chosen Landweber's regularization method, which is the simplest iterative method. The Moore-Penrose generalized solution (Jang, 2011; Ross, 2014) has to satisfy

$$ {L}^{\ast}\left\{L(F)\right\}={L}^{\ast}\left(\eta \right) $$ (25) where L is an integral operator and L∗ denotes the adjoint operator of L. When a positive constant λ is multiplied to both sides of Eq. (25), it becomes

$$ F=F-\lambda {L}^{\ast}\left\{L(F)\right\}+\lambda {L}^{\ast}\left(\eta \right) $$ (26) and formulated to the iterative method of Landweber's regularization as

$$ {F}_j={F}_{j-1}-\lambda {L}^{\ast}\left\{L\left({F}_{j-1}\right)\right\}+\lambda {L}^{\ast}\left(\eta \right),j=1,2,\dots $$ (27) The number of iterations and value of λ affect the solution accuracy. The consideration about an optimal number of iterations is decided through the L-curve criterion (Hansen, 2014), which is a stopping rule and is discussed in more detail in "Numerical model example."

2.4 Identifying $ {I}_{xx}\left(\ddot{\theta}\right) $ and $ D\left(\dot{\theta}\right) $ through the Integral Equation

The two unknowns, i.e., a nonlinear added mass moment of inertia $ {I}_{xx}\left(\ddot{\theta}(t)\right) $ and nonlinear damping moment $ D\left(\dot{\theta}(t)\right) $, can be determined through the inverse problems which is determined through Landweber's regularization method. Again, the inverse solution F(t)inv is equivalent to the right-hand side of Eq. (5):

$$ F{(t)}_{\mathrm{inv}}=-\left[{I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}(t)\right)\ddot{\theta}(t)+D\left(\dot{\theta}(t)\right)+\varDelta \overline{\mathrm{GZ}}\left(\theta (t)\right)- k\theta (t)\right] $$ (28) The pseudo-restoring moment is defined as

$$ {F}_r(t)=\varDelta \overline{\mathrm{GZ}}\left(\theta (t)\right)- k\theta (t) $$ (29) The pseudo-restoring moment is the known function that is comprised of the nonlinear restoring and dummy moments. The restoring moment can be identified through a heeling test or calculation, whose function is upon hull geometry. In this paper, the dummy moment is defined with the k value as a unit.

By substituting Eq. (29) into Eq. (28) and rearranging, Eq. (28) becomes

$$ {\displaystyle \begin{array}{l}{F}_{\mathrm{re}}(t)={F}_{\mathrm{inv}}(t)+{F}_r(t)\\ {}=-\left[{I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}(t)\right)\ddot{\theta}(t)+D\left(\dot{\theta}(t)\right)\right]\end{array}} $$ (30) where Fre(t) denotes the remaining moment that is the final moment function; a required function is used for identifying $ {I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}(t)\right)\ddot{\theta}(t) $ and $ D\left(\dot{\theta}(t)\right) $.

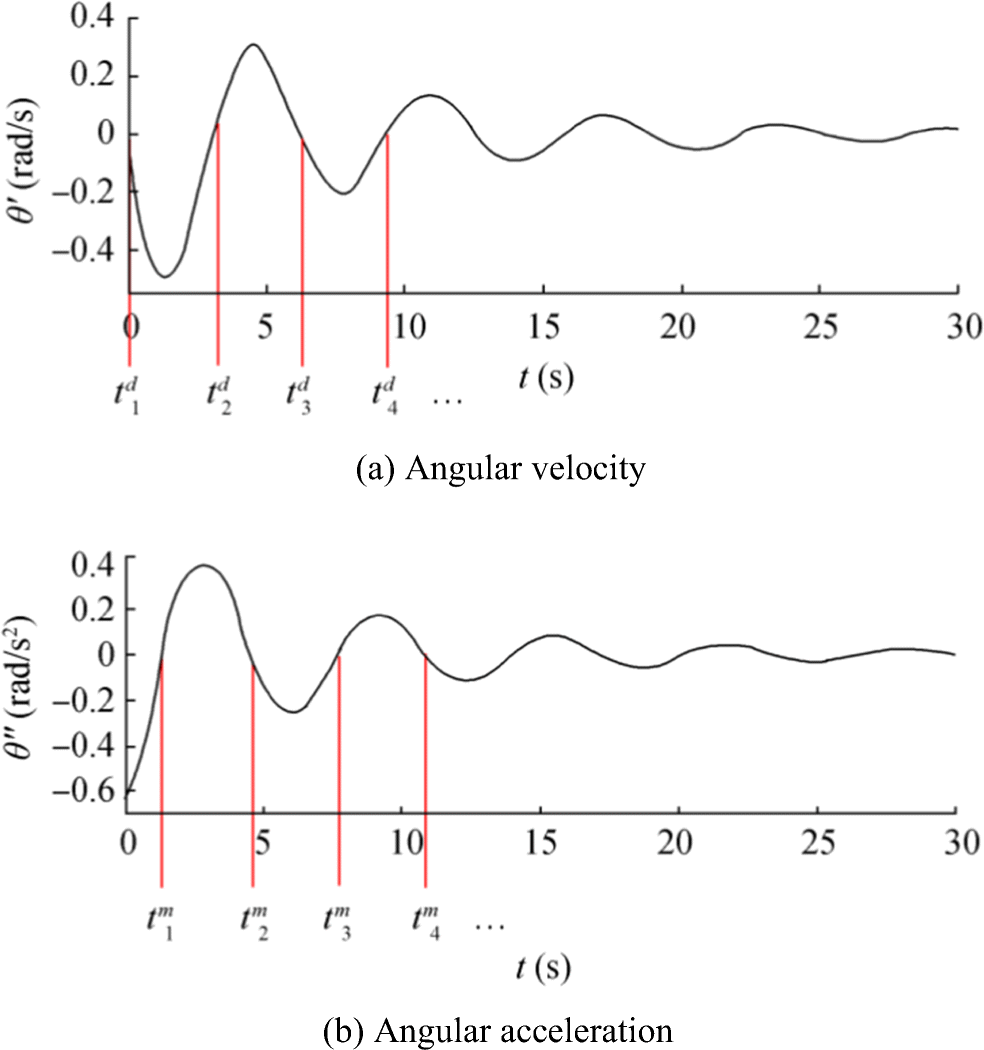

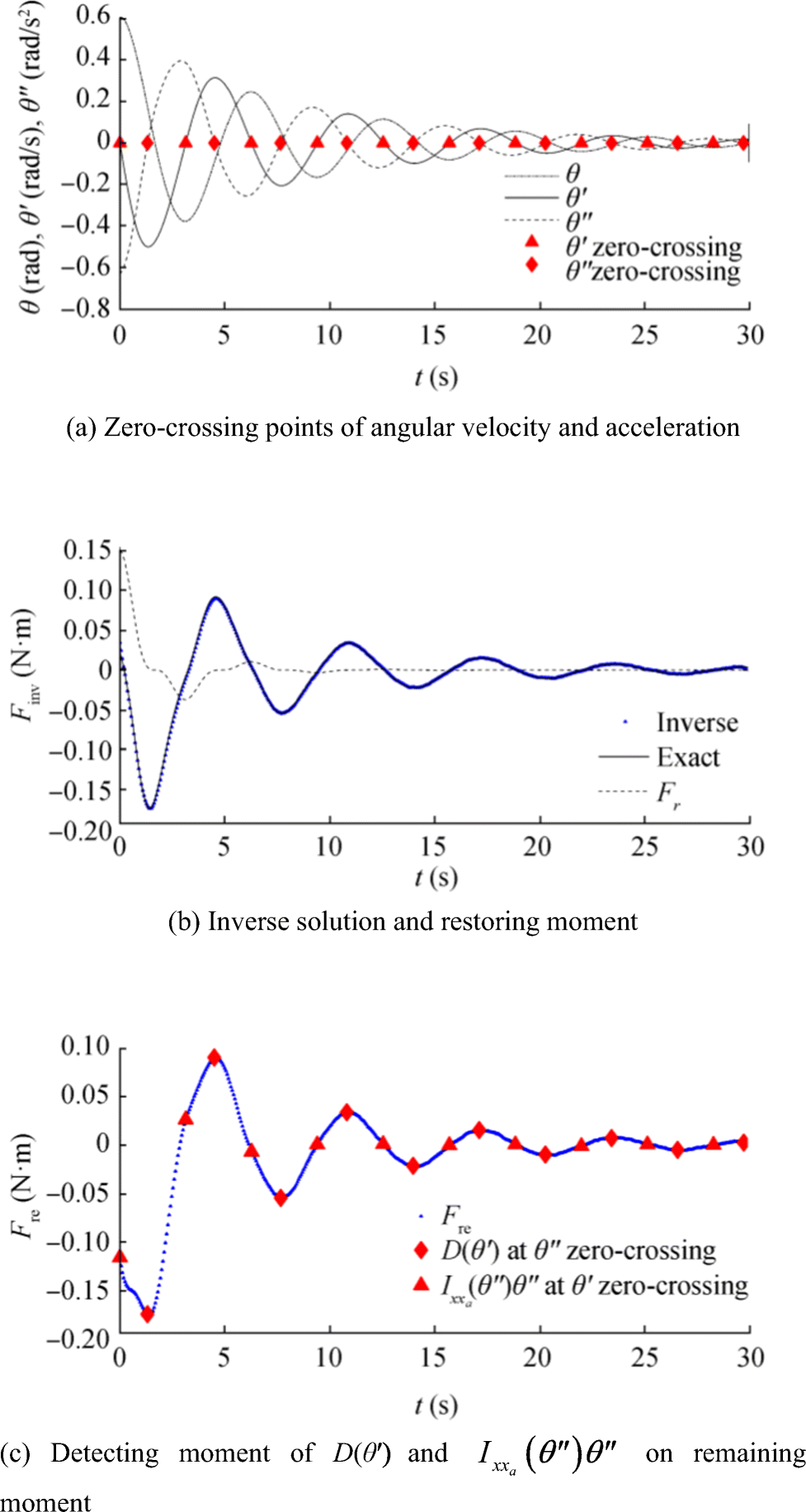

The separation between $ {I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}(t)\right)\ddot{\theta}(t) $ and $ D\left(\dot{\theta}(t)\right) $ from the remaining moment requires a zero-crossing time technique, as in Figure 4, where a number of intersection points of the measured data curve of $ \dot{\theta} $ with the time axis are found when $ {t}^d={t}_1^d,{t}_2^d,\dots $ In the same way, there is an intersection of the curve of $ \ddot{\theta} $ with the time axis when $ {t}^m={t}_1^m,{t}_2^m,\dots $:

$$ \dot{\theta}\left({t}_i^d\right)=0 $$ (31) $$ \ddot{\theta}\left({t}_i^m\right)=0 $$ (32) The intersection point of both curves holds for the marking point on the remaining moment curve shown in Figure 5. Thus,

$$ F{\left({t}_i^d\right)}_{\mathrm{re}}=-\left[{I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}\left({t}_i^d\right)\right)\ddot{\theta}\left({t}_i^d\right)+D\left(\dot{\theta}\left({t}_i^d\right)\right)\right] $$ (33) and

$$ F{\left({t}_i^m\right)}_{\mathrm{re}}=-\left[{I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}\left({t}_i^m\right)\right)\ddot{\theta}\left({t}_i^m\right)+D\left(\dot{\theta}\left({t}_i^m\right)\right)\right] $$ (34) From Eq. (31), in the intersection point of $ \dot{\theta} $, the damping moment is zero. Hence, Eq. (33) becomes

$$ F{\left({t}_i^m\right)}_{\mathrm{re}}=-D\left(\dot{\theta}\left({t}_i^m\right)\right) $$ (35) Similarly, in the intersection point of $ \ddot{\theta} $, the added moment of inertia is zero. Hence, Eq. (34) becomes

$$ F{\left({t}_i^d\right)}_{\mathrm{re}}=-{I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}\left({t}_i^d\right)\right)\ddot{\theta}\left({t}_i^d\right) $$ (36) where superscripts m and d denote the mass moment of inertia and damping measured data, respectively, and i denotes the number of the intersection point.

Finally, when collecting all of the intersection points of $ F{\left({t}_i^m\right)}_{\mathrm{re}} $ and $ F{\left({t}_i^d\right)}_{\mathrm{re}} $, we can formulate the functions for each moment function by the appropriate curve fitting method, such as a polynomial function.

3 Numerical Model Example

The proposed scheme demonstrates its workability in identifying the function form of nonlinear added mass moment of inertia and nonlinear damping moment that were carried out through the numerical example.

3.1 Fully Nonlinear EOM

The EOM considered in this study was proposed by Taylan (2000) and is a typical equation of the nonlinear roll motion, which considers that the ship is under the excitation of regular sinusoidal waves:

$$ \left({I}_{xx}+{I}_{xx_a}\right)\ddot{\theta}+D\left(\dot{\theta}\right)+\varDelta \overline{\mathrm{GZ}}\left(\theta \right)={\omega}_e^2{\alpha}_m{I}_{xx}\cos {\omega}_et $$ (37) where ωe and αm are the encountered angular frequency and wave slope, respectively. In this study, the proposed scheme is used for free decay testing, so the right-hand side of Eq. (37) is excluded. The three types of nonlinear damping moment functions were classified by Taylan (2000). The nonlinear damping moment function type B1 that is the quadratic equation from Taylan's classification (Taylan, 2000) is chosen for this study:

$$ D\left(\dot{\theta}\right)={D}_L\dot{\theta}+{D}_N\dot{\theta}\left|\dot{\theta}\right| $$ (38) where DL and DN are the linear and nonlinear damping coefficients, respectively. The squared angular velocity term is written as $ \dot \theta \left| {\dot \theta } \right|$ because changing the sign of $ \dot{\theta} $ changes the sign of this term and ensures that damping always opposes the motion.

In general, the cubic and quintic forms of restoring the moment functions are most favorable because they are manipulated easier than higher degree polynomials in the solution procedure (Taylan, 2000). Thus, the restoring moment term is considered by solving Eq. (39).

$$ \varDelta \overline{\mathrm{GZ}}\left(\theta \right)=\varDelta \left({C}_1\theta +{C}_3{\theta}^3+{C}_5{\theta}^5\right) $$ (39) where Cn, n = 1, 3, 5 are the restoring coefficients of each order. $ {I}_{xx_a} $ in Eq. (37) is normally a constant value, but this study assumed a nonlinear added moment of inertia and its function, following Kianejad et al. (2019). Hence, its magnitude initially increases by increasing the roll angle but quickly declines once the peak value reaches a large roll angle range. However, in this study, the added mass moment of inertia was functioned with angular acceleration, so it was transformed. For simplicity, it was limited to the range before it reaches the peak. Moreover, as the moment of inertia, its function is impossible to be a negative sign when the sign of angular acceleration changes. The expression of the added moment of inertia is as follows:

$$ {I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}\right)={I}_{xx_a}{\ddot{\theta}}^2 $$ (40) Thus, Eq. (37) can be rewritten as

$$ \left({I}_{xx}+{I}_{xx_a}{\ddot{\theta}}^2\right)\ddot{\theta}+{D}_L\dot{\theta}+{D}_N\dot{\theta}\left|\dot{\theta}\right|+\varDelta \left({C}_1\theta +{C}_3{\theta}^3+{C}_5{\theta}^5\right)=0 $$ (41) with the initial conditions for this experiment given as

$$ \theta (0)=0.61\ \mathrm{rad}\ \mathrm{and}\ \dot{\theta}(0)=0\ \mathrm{rad}/\mathrm{s} $$ (42) For convenience, the values of Ixx and k in Eq. (5) are normalized to units.

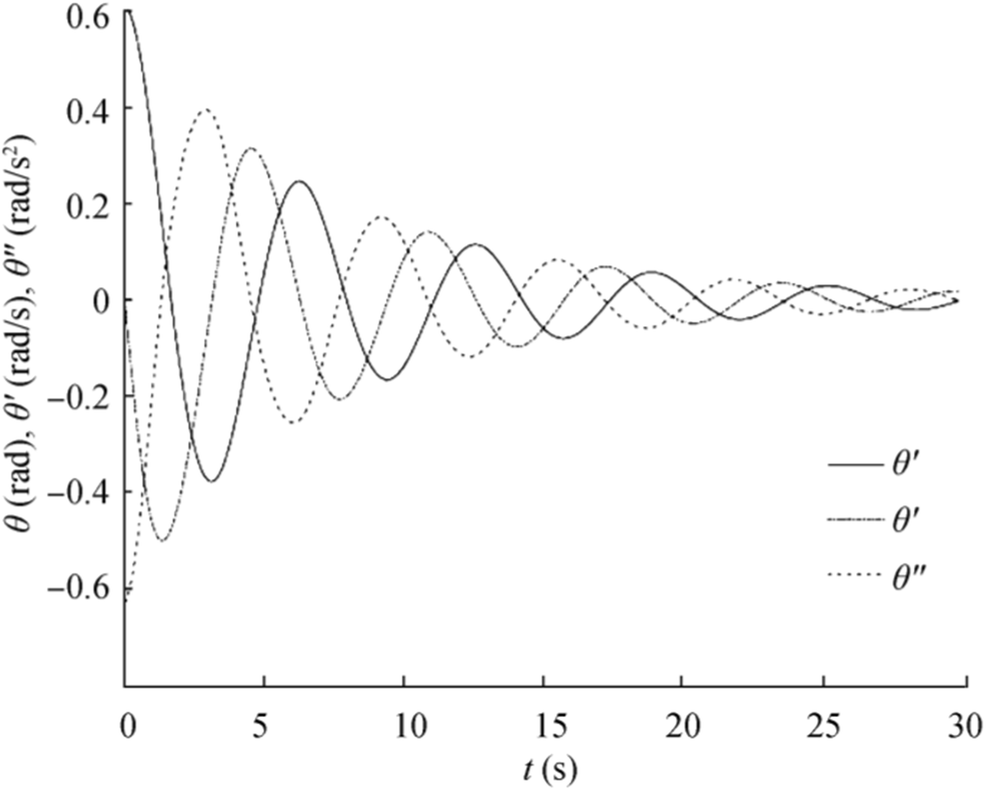

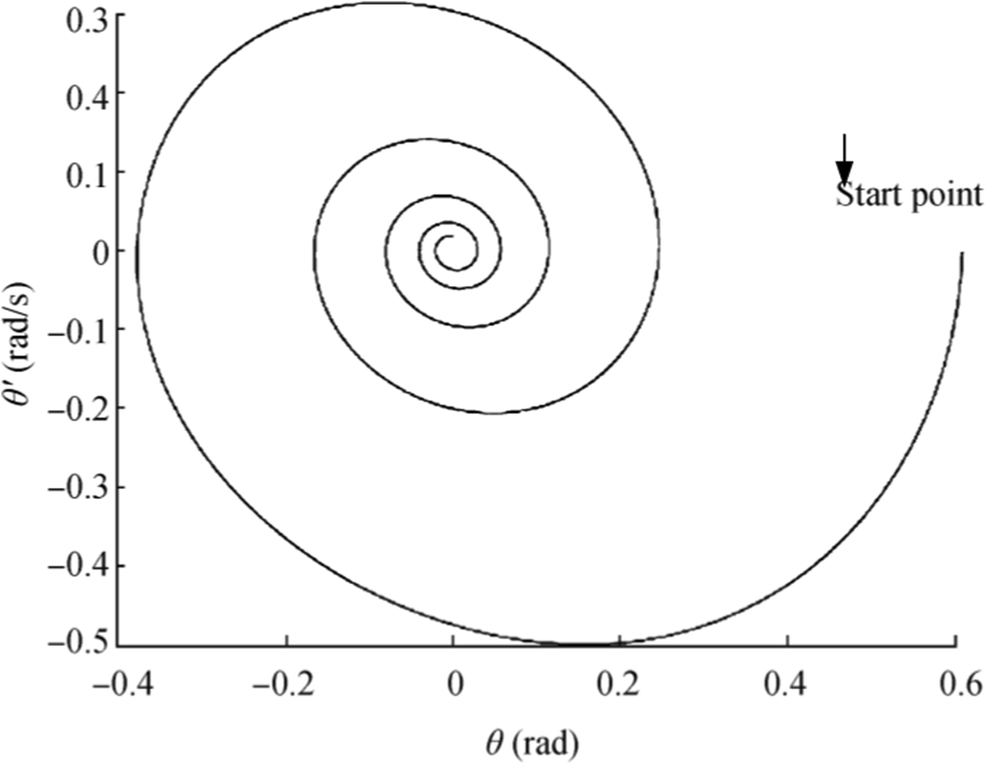

For the numerical solution of Eq. (41), the nonlinear ODE was solved by the Runge-Kutta integration scheme with a time step of 0.06 s. The solution and phase diagrams were expressed for DL = 0.2, DN = 0.3, C1 = 0, C3 = 0.7, C5 = − 0.1, and $ {I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}\right)=0.5{\ddot{\theta}}^2 $, as shown in Figures 5 and 6, respectively. This solution was used for the virtual measured data.

Figure 6 Phase diagram corresponding to Figure 5

Figure 6 Phase diagram corresponding to Figure 53.2 Noisy Data

The measured data of motion responses have noise. To model the measured data, the noise was generated as follows:

$$ {\left\Vert \eta -{\eta}^{\delta}\right\Vert}_2\le \delta $$ (43) where ηδ is the left-hand side of Eq. (22) and δ is the noise level, where δ > 0. In this study, δ = 0.001, where ‖·‖2 denotes the L2 norm (Filaseta et al., 1992). Thus, we aim to solve the perturbed equation:

$$ {\eta}^{\delta }={\int}_0^tK\left(t,\tau \right)F\left(\tau \right)\mathrm{d}\tau $$ (44) 3.3 L-Curve Criterion

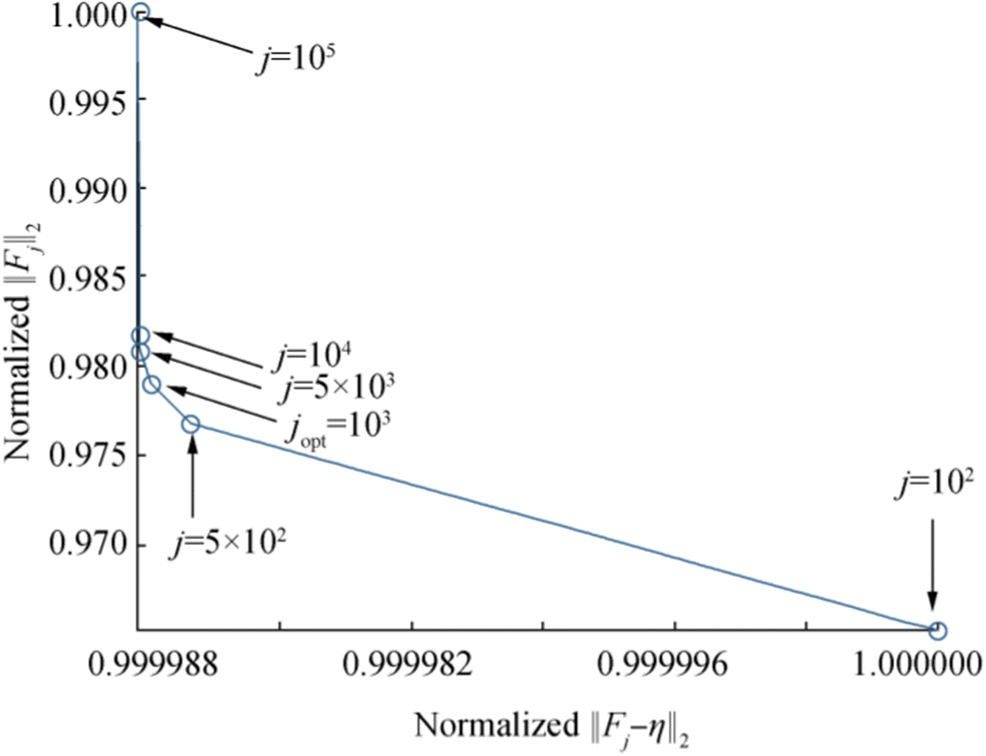

To solve the perturbed equation, the iteration in Landwerber's regularization method was chosen. The number of iterations plays an important role in the convergence of the solution. The L-curve criterion helps decide the optimal iteration number and results in the best solution.

For selecting the appropriate number of iteration to obtain the optimal solution, the L-curve plots a log-log type of iterated solution norms versus the norm of the corresponding residual, which is represented as follows:

$$ \left(\log {\left\Vert {LF}_j-\eta \right\Vert}_2,\log {\left\Vert {F}_j\right\Vert}_2\right) $$ (45) Equation (45) displays the shape of the curve as an "L" shape. The optimum point corresponding to the optimal solution is located at the corner of the curve.

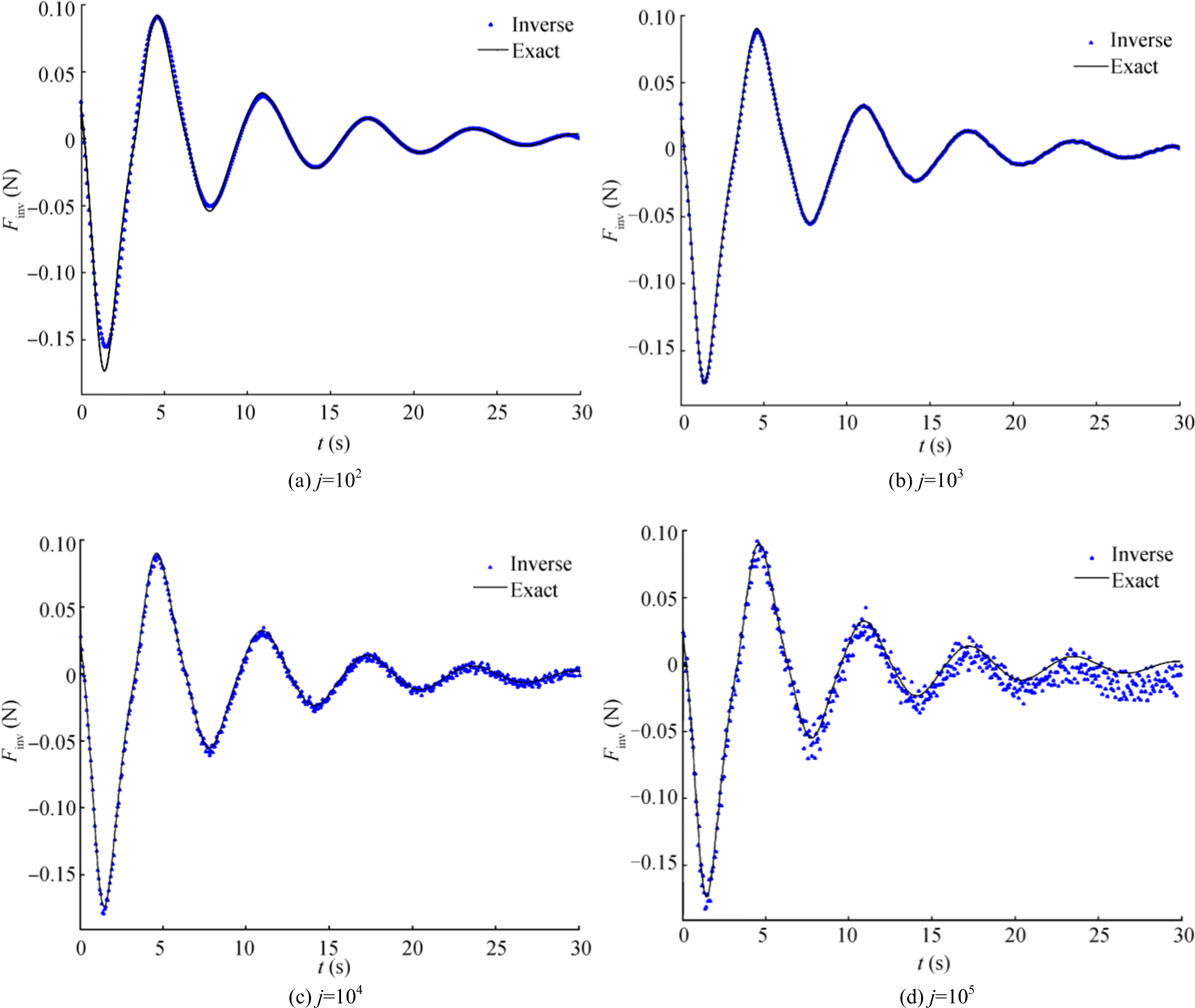

The L-curve is plotted in Figure 7, with δ = 0.001 and λ = 0.001 for Landweber's method in Eq. (27), and obtained the optimal point at jopt = 103. The convergence behaviors of the iterative solutions in Figure 8 were observe to match the optimal point from Figure 7 to examine the correct optimal solution. Figure 8b presents the optimal solution obtained from the inverse solution, which was plotted closest to the exact solution and had acceptable stability.

3.4 Recovering $ {{I}}_{{{xx}}_{{a}}}\left(\ddot{{\theta}}\right) $ and $ {D}\left(\overset{.}{{\theta}}\right) $

Following the procedure described in "Identifying $ {I}_{xx}\left(\ddot{\theta}\right) $ and $ D\left(\dot{\theta}\right) $ through the integral equation, " the zero-crossing points of $ \ddot{\theta} $ and $ \dot{\theta} $ were detected and shown at the top of Figure 9 and were held on for comparison with the final inverse solution. The optimal solution from Landweber's regularization method is shown by a dot in the middle part of Figure 9, which also consists of the moments that were explained in Eq. (28). The pseudo-restoring moment Fr in Eq. (29) (known parameter) is plotted with the optimal inverse solution to describe the superposition method for removing Fr from Eq. (28). Thus, the inverse solution F(t)inv became the final inverse solution Fre that resulted from Eq. (30), which is shown at the bottom of Figure 9. The remaining moments were the final inverse solution that consisted of the moment due to added mass moment of inertia $ {I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}(t)\right)\ddot{\theta}(t) $ and the damping moment $ D\left(\dot{\theta}(t)\right) $. Finally, the separation of these moments was performed through the comparison of detected zero-crossings of $ \ddot{\theta} $ and $ \dot{\theta} $ at the top of Figure 9, which they gave the damping moment and moment due to added mass moment of inertia values at the same time levels, respectively, and were shown at the bottom of Figure 9. The obtained results show that the changing of the positive and negative signs of the moment due to added mass moment of inertia values is similar as that of $ \ddot{\theta} $ at each time level of the $ \dot{\theta} $ zero-crossing. However, the changing of signs of damping moment values is similar as that of $ \dot{\theta} $ at each time level of the $ \ddot{\theta} $ zero-crossing. The signs are written in the anti-symmetric form as follows:

$$ D\left(-\dot{\theta}(t)\right)=-D\left(\dot{\theta}(t)\right) $$ (46) $$ {I}_{xx_a}\left(-\ddot{\theta}(t)\right)\cdot \left(-\ddot{\theta}(t)\right)=-{I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}(t)\right)\ddot{\theta}(t) $$ (47)  Figure 9 Explaining the identifying method of nonlinear moment due to added mass moment of inertia and nonlinear damping moment as follow Eqs. (31)–(36). a Zero-crossing points of angular velocity and acceleration. b Inverse solution and restoring moment. c Detecting moment of D(θ′) and $ {I}_{xx_a}\left(\theta^{{\prime\prime}}\right)\theta^{{\prime\prime} } $ on remaining moment

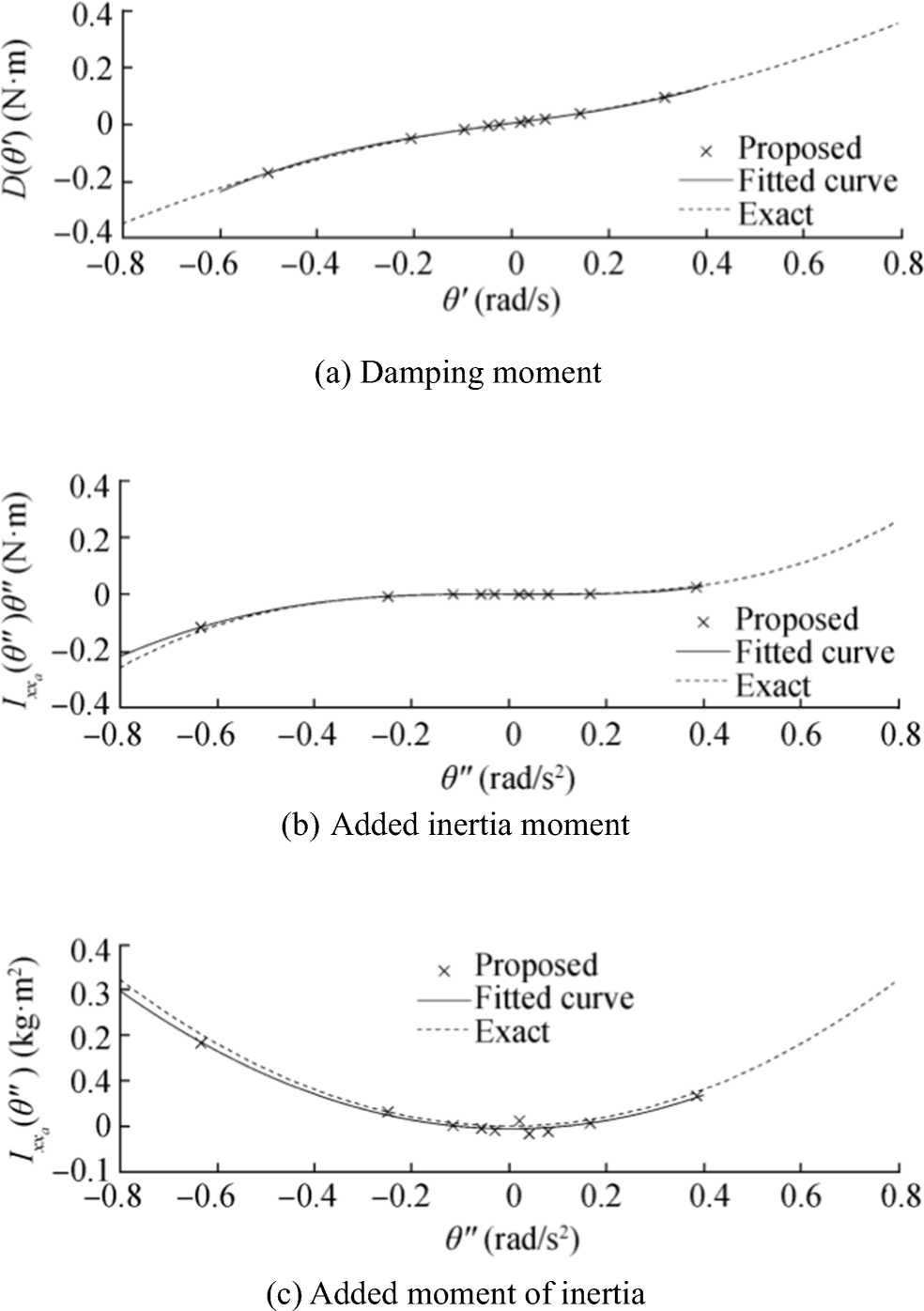

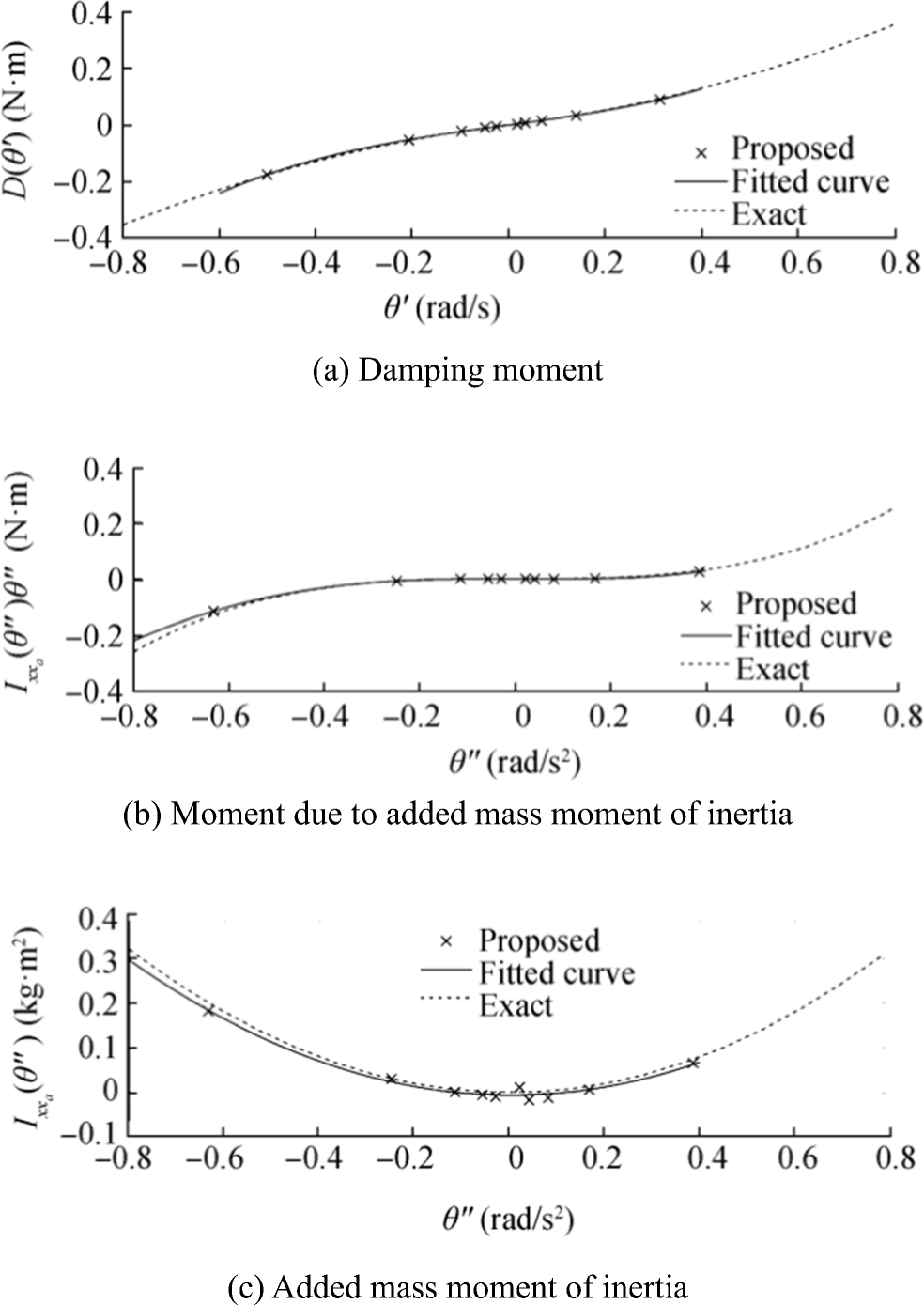

Figure 9 Explaining the identifying method of nonlinear moment due to added mass moment of inertia and nonlinear damping moment as follow Eqs. (31)–(36). a Zero-crossing points of angular velocity and acceleration. b Inverse solution and restoring moment. c Detecting moment of D(θ′) and $ {I}_{xx_a}\left(\theta^{{\prime\prime}}\right)\theta^{{\prime\prime} } $ on remaining momentThe detected points of the damping and moment due to added mass moment of inertia in the bottom of Figure 9 were re-plotted versus the roll angular velocity and acceleration at the middle and top of Figure 10, respectively. The results of dividing the moment due to added moment of inertia values by the angular accelerations at the same time level became the added mass moment of inertia values that are plotted at the bottom of Figure 10.

However, the correct position of a function from data points is still unknown, but hypothetically speaking with experience, a curve from a guessed function must lay on data points as closely as possible. The use of the curve fitting method by a polynomial function is simple and widely used. Thus, in this case, the nonlinear damping moment was fitted by a third-order polynomial function, the nonlinear moment due to added mass moment of inertia was fitted by a fourth-order polynomial function, and the nonlinear added moment of inertia was fitted by a second-order polynomial function. All of the fitted curves were plotted and compared with the exact solution: The top of Figure 10 shows the nonlinear damping moment, the middle of Figure 10 shows the nonlinear moment due to mass moment of inertia, and the bottom of Figure 10 shows the nonlinear added mass moment of inertia. The comparison between the recovered function and exact function gave very good results.

To check and prove the correction and accuracy of the identified moments, Figure 11 shows the plot of the recovered $ \ddot{\theta} $, $ \dot{\theta} $, and θ, which were compared with the exact solution. However, the detected zero-crossing point with one of the initial conditions may not be sufficient to recognize all of the shapes of $ {I}_{xx_a}\left(\ddot{\theta}\right) $ and $ D\left(\dot{\theta}\right) $. For more accuracy, it may need more measured data with different initial conditions.

4 Conclusions

To determine the nonlinear added mass moment of inertia and damping moment, a nonparametric identification system was used. In this study, the nonparametric identification required an inverse problem that was formulated from the nonlinear EOM. The inverse solution from the numerical method became unstable because of a small amount of noisy data, which can be amplified and lead to unreliable solutions. Accordingly, Landweber's regularization method was used to select the optimal number of iterations through the L-curve criterion. The workability of the proposed procedure is depicted through a numerical example that is fully nonlinear EOM. The results show that the proposed method identified the functional form of the nonlinear added mass moment of inertia and damping moment.

-

Figure 6 Phase diagram corresponding to Figure 5

Figure 9 Explaining the identifying method of nonlinear moment due to added mass moment of inertia and nonlinear damping moment as follow Eqs. (31)–(36). a Zero-crossing points of angular velocity and acceleration. b Inverse solution and restoring moment. c Detecting moment of D(θ′) and $ {I}_{xx_a}\left(\theta^{{\prime\prime}}\right)\theta^{{\prime\prime} } $ on remaining moment

-

Abdul-Majid W (2011) Linear and nonlinear integral equations. Higher Education Press, Beijing, pp 33–63 Anthony FM (2008) The maritime engineering reference book. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, London, pp 79–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-7506-8987-8.X0001-7 Chassiakos AG, Masri SF (1996) Modeling unknown structural systems through the use of neural network. Earthq Eng Struct Dyn 25(2): 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9845(199602)25:23.0.CO;2-A Cotton B, Spyrou KJ (2001) An experimental study of nonlinear behavior in roll and capsize. Int Shipbuild Prog 48(1): 5–18 Filaseta M, Robinson ML, Wheeler FS (1992). The minimal Euclidean norm of an algebraic number is effectively computable. University of South Carolina. Available from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.94.7757&rep=rep1&type=pdf [accessed on June, 6, 2019] Haddara MR, Wu X (1993) Parameter identification of nonlinear rolling motion in random seas. Int Shipbuild Prog 40(423): 247–260 Hansen PC (2014). The L-curve and its use in the numerical treatment of inverse problem. Technical University of Denmark. Available from https://www.sintef.no/globalassets/project/evitameeting/2005/lclcur.pdf [accessed on June, 6, 2019] Irkal MAR, Nallayarasu S, Bhattacharyya S (2019) Numerical prediction of roll damping of ships with and without bilge keel. Ocean Eng 179: 226–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2019.03.027 Iourtchenko DV, Dimentberg MF (2002) In-service identification of non-linear damping from measured random vibration. J Sound Vib 255(3): 549–554. https://doi.org/10.1006/jsvi.2001.4179 Jang TS, Choi Hang S, Han SL (2009a) A new method for detecting nonlinear damping and restoring forces in nonlinear oscillation systems from transient data. Int J Non-Linear Mechan 44(7): 801–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnonlinmec.2009.05.001 Jang TS, Kwon SH, Han SL (2009b) A novel method for non-parametric identification of nonlinear restoring forces in nonlinear vibrations from noisy response data: a conservative system. J Mech Sci Technol 23(11): 2938–2947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12206-009-0822-5 Jang TS, Kwon SH, Lee JH (2010a) Recovering the functional form of the nonlinear roll damping of ships from a free-roll decay experiment: an inverse formulism. Ocean Eng 37: 14–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2010.06.012 Jang TS, Beak H, Han SL, Kinoshita T (2010b) Indirect measurement of the impulsive load to a nonlinear system from dynamic responses: inverse problem formulation. Mech Syst Signal Process 24(6): 1665–1681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2010.01.003 Jang TS, Baek H, Choi SH, Lee S-G (2011a) A new method for measuring nonharmonic periodic excitation forces in nonlinear damped systems. Mech Syst Signal Process 25(6): 2219–2228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2011.01.012 Jang TS, Hyoungsu B, Kim MC, Moon BY (2011b) A new method for detecting the time-varying nonlinear damping in nonlinear oscillation systems: nonparametric identification. Math Probl Eng 2011(3): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/749309 Jang TS (2011) Non-parametric simultaneous identification of both the nonlinear damping and restoring characteristics of nonlinear systems whose dampings depend on velocity alone. Mech Syst Signal Process 25(4): 1159–1173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymssp.2010.11.002 Jang TS (2013) A method for simultaneous identification of the full nonlinear damping and the phase shift and amplitude of the external harmonic excitation in a forced nonlinear oscillator. Comput Struct 120: 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compstruc.2013.02.008 Kianejad SS, Enahaei H, Duffy J, Ansarifard N, Rnmuthugala D (2019) Ship roll damping coefficient prediction using CFD. J Ship Res 63(15): 108–122. https://doi.org/10.5957/JOSR.09180061 Kianejad SS, Enahaei H, Duffy J, Ansarifard N (2019a) Investigation of a ship resonance through numerical simulation. J Hydrodyn: 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42241-019-0037-x Kianejad SS, Enahaei H, Duffy J, Ansarifard N (2019b) Prediction of a ship roll added mass moment of inertia using numerical simulation. Ocean Eng 173: 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2018.12.049 Lazan BJ (1968) Damping of materials and members in structural mechanics, vol 38. Oxford Pergamon Press, Oxford Liang YC, Zhou CG, Wang ZS (1997) Identification of restoring forces in non-linear vibration systems based on neural networks. J Sound Vib 206(1): 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1006/jsvi.1997.1084 Liang YC, Feng DP, Cooper JE (2001) Identification of restoring forces in non-linear vibration systems using fuzzy adaptive neural networks. J Sound Vib 242(1): 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1006/jsvi.2000.3348 Mancini S, Begovic E, Day AH, Incecik A (2018) Verification and validation of numerical modelling of DTMB 5415 roll decay. Ocean Eng 160: 209–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2018.05.031 Masri SF, Chassiakos AG, Cauchey TK (1993) Identification of nonlinear dynamic systems using neural networks. J Appl Mech 60(1): 123–133. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2900734 Massachusetts Institute of Techonlogy (2002). Inverse problems. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Aaliable from http://web.mit.edu/2.717/www/inverse.html [Accessed on June 6, 2019] Mohammad KS, Worden K, Tomlinson GR (1992) Direct parameter estimation of linear and non-linear structures. J Sound Vib 125(3): 471–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-460X(92)90482-D Naprstek J (1999), Identification of linear and non-linear dynamic systems with parametric noise. 1998 The Fourth International Conferenece on Stochatic Strural Dynamic, Notre Dame, IN, 395-402. Oliva-Remola A, Bulian G, Rerez-Rojas L (2018) Estimation of damping through internally excited roll tests. Ocean Eng 160: 490–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2018.04.052 Park J, Jang TS, Syngellakis S, Sung HG (2014) A numerical scheme for recovering the nonlinear characteristics of a single degree of freedom structure: non-parametric system identification. 2014 Structures under Shock and Impact XIII, Liverpool. 141: 335–343. https://doi.org/10.2495/SUSI140291 Qinian J (2011). Newton-type regularization methods for nonlinear inverse problem. 2011 19th International Congress on Modelling and Simulation, Perth, Australia, 385–391 Ross M (2014). The Moore-Penrose inverse and least squares. University of Puget Sound. Available from http://buzzard.ups.edu/courses/2014spring/420projects/math424-UPS-spring-2014-macausland-pseudo-inverse.pdf [ccessed on June, 6, 2019] Sathyaseelan D, Hariharan G, Kannan K (2017) Parameter identification for nonlinear damping coefficient from large-amplitude ship roll motion using wavelets. J Basic Appl Sci 6(2): 138–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjbas.2017.02.003 Spina D, Valente C, Tomlinson GR (1996) A new procedure for detecting nonlinearity from transient data using the Gabor transform. Nonlinear Dynam 11(3): 235–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00120719 Taylan M (1999) Solution of nonlinear roll model by a generalized asymptotic method. Ocean Eng 27(11): 1169–1181. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0029-8018(98)00064-X Taylan M (2000) The effect of nonlinear damping and restoring in ship rolling. Ocean Eng 27(9): 921–932. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0029-8018(99)00026-8 Volker B (2000) Practical ship hydrodynamics. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, pp 98–148 Wassermann S, Feder DF, Abdel-Maksoud M (2016) Estimation of ship roll damping-a comparison of the decay and the harmonic excited roll motion technique for a post panamax container ship. Ocean Eng 120:77–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2016.02.009