1 Introduction

Scour is the lowering of stream bed elevation which takes place in the vicinity or around a structure constructed in a flowing water (Garde and Kothyari, 1998), which results in the exposure of pier foundation which is one of the major causes of bridge failure (Avent and Alawady, 2005). Damage in crucial hydraulic structures like bridges has deep social and economic implications due to the costs of reconstruction, disruptions of traffic flow circulation and in some cases the costs of human lives. With the prospect of more severe and frequent floods owing to climatic changes, reducing the risk of bridge failure is becoming increasingly important (Lagasse, 2007). Analysing the risk of failure of bridges affected by scour and rigorous study of the economic feasibility of possible countermeasures to prevent bridge collapses are useful tools, which may be used by the engineers and researchers to assess and define new design approaches.

A large number of studies have been conducted to predict the scour depth around piers (Laursen and Toch, 1956; Breusers et al., 1977; Ettema, 1980; Melville and Sutherland, 1988; Kothyari et al., 1992; Melville and Coleman, 2000; Ansari et al., 2002; Chang et al., 2004; Aghaee-Shalmani and Hakimzadeh, 2015) and to find countermeasure techniques to reduce the scouring (Kumar et al., 1999; Lagasse, 2007). Qadar (1981) explored the interaction between horse shoe vortex and temporal increase of scour depth. Baker (1981) investigated the relationship between approach velocity and the development of scour depth. Chiew and Melville (1987) stated that the ratio of mean flow velocity and threshold velocity influences the scour depth. If the ratio is less than 0.5, no scour occurs. If it lies between 0.5 and 1, it is considered as clear water scour and between 1 and 4, it is considered as live bed scour. Kothyari et al. (1992) proposed a set of equations for calculating equilibrium scour depth at clear water and live bed condition considering mean flow velocity, threshold velocity, mean sediment size, average flow depth and pier diameter. Recently researchers (Chiew and Lim, 2000; Chiew, 2004; Zarrati et al., 2004 and 2006; Grimaldi et al., 2009; Masjedi et al., 2010) have attempted to reduce the scour depth by using flow altering devices such as riprap, bed sill and collars. Zhuang and Liu (2007) has investigated the experimental study on the width of turbulent area around the bridge pier and proposed the formula of calculating the turbulent flow width around the bridge pier.

Local scour around the bridge pier results in a complex interaction between turbulent flow and mobile bed sediment particles. Thus, investigating hydrodynamics of the flow structure near the scour and erosion mechanisms can provide a proper insight into the scouring process and aid to predict scour depth precisely (Ahmed and Rajaratnam, 1998). Graf and Istiarto (2002) experimentally investigated the three dimensional flow fields in an equilibrium scour hole. Results of their study showed that a vortex system was established in front of the circular pier and a trailing wake-vortex system of strong turbulence was formed at the rear of the circular pier. Raikar and Dey (2008) presented the results of an experimental study on the turbulent horseshoe vortex flow within the intermediate scour hole. They observed that the flow and turbulence intensities in the horseshoe vortex in a developing scour hole were reasonably similar in all directions. At the upstream side of the pier, strong reversal of flow can be seen which, in turn, retards streamwise velocity component. Izadinia et al. (2012) carried out experimental investigation on the turbulent flow parameters around a pier. They found that at upstream of the pier probability of occurrence of sweep events are dominant; whereas, at the downstream of the pier sweep and ejection both are nearly equal. Zhao et al. (2015) investigated about the turbulence models on the boundary layer flow with adverse pressure gradients and found that results generated by Wilcox (2006) k-w are closest to the experimental data.

Natural streams comprise of porous granular boundaries which play an important role in influencing the flow characteristics. Depending upon the difference in level of water in channel and ground water table, water either seeps into the channel (injection) or comes out of it (suction) through porous channel bed and banks. Seepage flow which occurs at the interface between the sand bed and the flowing water is very complex. The downward seepage (suction) changes hydrodynamic characteristics of the channel. The bed shear stress increases due to increased downward seepage, which results in more sediment transport (Rao and Sitaram, 1999; Chen and Chiew, 2004; Deshpande and Kumar, 2016). Moreover, near bed vertical velocity is increased due to downward seepage in case of porous bed boundary (Corvaro et al., 2014a, 2014b). Apart from changes in flow structures, the loss of water due to seepage in alluvial channel has been also estimated in the order of 45% of total volume of the water supplied to the head of the canal (Shukla and Misra, 1994). In Ganga canal, seepage loss reported per day per unit length is 2.2 m3 (Krishnamurthy and Rao, 1969). Kinzli et al. (2010) measured that around 40% of the total water is lost because of downward seepage. Tanji and Kielen (2002) estimated that in unlined earthen canals, seepage losses can account for 20%-50% of the total flow volume. Martin and Gates (2014) estimated loss of about 15% of the upstream flow rate because of downward seepage. Since seepage can change the flow boundary condition and existing sediment transport rates, scouring of the river bed will also be changed accordingly. Dey and Sarker (2007) carried out experiments to investigate the effect of injection (upward seepage) through the river bed downstream of an apron of a sluice gate. They found that equilibrium scour depth and many other scour geometry parameters increased with increase of injection. Francalanci et al., (2008) showed experimentally that suction caused scour and injection produced deposition. Qi et al., (2012) conducted experiments with 2% suction to investigate effect of seepage around bridge pier and found a reduction in equilibrium scour depth. However, in natural streams neither point suction is attainable nor the suction zone can be restricted as employed by above mentioned researchers. Cao et al. (2013) has also shown that sediment transport rate increases with the increase in length of the suction zone. Thus in the present study, downward seepage was applied throughout the length of the flume with alluvial streambed to imitate the natural pattern of suction up to a certain extent. The main objective of this study is to analyse the effect of downward seepage on turbulent structure of flow which is responsible for the phenomenon of scour process around the bridge piers. Present work also aims to explore the change in bed morphology around the pier with the application of seepage.

2 Experimental setup and methodologyExperiments were conducted in glass walled tilting flume with 17.2 m in length, 1m in width and 0.72 m depth. Fig. 1 shows schematic diagram of experimental setup.

|

| Figure 1 Schematic diagram of experimental setup |

The flume has a seepage chamber of 1 m wide and 0.22 m deep (out of total depth 0.72 m), located at 1.6 m from the upstream end of the flume, which collects water and allows free passage of water through the sand bed. A collection tank having dimensions 2.8 m long, 1.5 m wide, and 1.5 m deep was provided at the upstream end of the flume with a couple of wooden baffles installed in it to prevent highly turbulent flow from entering the channel. The bed slope is fixed at 0.1%. The discharge is measured by the rectangular notch at downstream of the flume. Two electromagnetic flowmeters are installed to apply and regulate the desired seepage discharge. The flow depth in channel is measured by digital point gauge attached to a moving trolley. According to Chiew and Melville (1987) the pier diameter should not be larger than 10% of channel width to avoid side wall effect on scour depth. Thus, Piers of perspex material of diameter 75 mm and 90 mm with height 150 mm were used. Piers are located at the test section of 7.5 m from downstream end of the flume in such a way that approach length ought to fulfil fully developed flow condition. River sand of median size 0.418 mm was used. D/d50 > 50 is maintained to neglect the effect of sediment size on the scouring around bridge piers (Chiew and Melville, 1987). Geometric standard deviation (

| $u = \frac{1}{N}\mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^N {U_i}$ | (1) |

| $w = \frac{1}{N}\mathop \sum \limits_{i = 1}^N {W_i}$ | (2) |

where Ui and Wi are instantaneous velocities in stream wise and vertical directions respectively. N is number of instantaneous velocity samples. Streamwise (u') and vertical fluctuating components (w') are calculated as:

| $u' = {U_i} - u$ | (3) |

| $w' = {W_i} - w$ | (4) |

Reynolds shear stress are calculated as:

| ${\tau _{uw}} = - \rho \overline {u'w'} $ | (5) |

| $\overline {u'w'} = \frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{i = 1}^n {\left({{U_i} - u} \right)} \left({{W_i} - w} \right)$ | (6) |

Sensitivity analysis of ADV data has been carried out and given in the Table 1. In Table 1, u, v and w are the time-averaged velocities in the streamwise, spanwise and vertical directions, respectively. u', v' and w' are the fluctuating components of the streamwise, spanwise and vertical instantaneous velocities, respectively.

| Item | Standard deviation | Uncertainty % |

| u (m/s) | 2.15×10-3 | 0.14 |

| v (m/s) | 9.94×10-4 | 0.08 |

| w (m/s) | 4.44×10-4 | 0.03 |

| 1.09×10-3 | 0.09 | |

| 9.06×10-4 | 0.08 | |

| 3.24×10-4 | 0.03 |

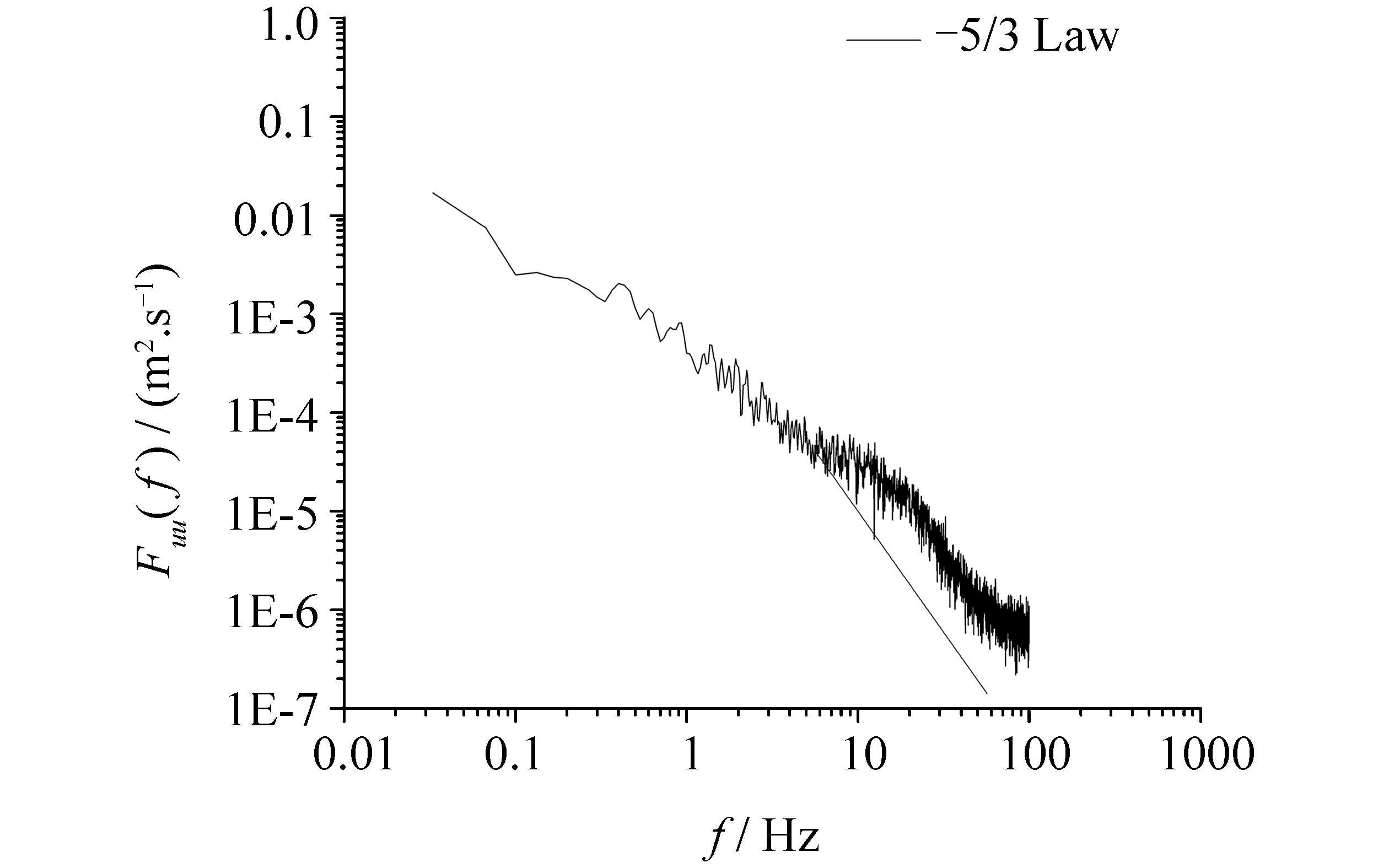

The velocity and turbulence data is filtered out by acceleration threshold method (Goring and Nikora, 2002) to remove the spikes. The threshold values have been chosen between 1 to 1.5 based on trial and error method in such a way that velocity power spectra fit with Kolmogorov's −5/3 law in the inertial subrange (Devi and Kumar, 2015). In all experiments an average correlation coefficient between transmitted and received signal is less than 70% and signal to noise ratio kept (SNR) between 10 and 15.

|

| Figure 2 Velocity power spectra with Kolmogorov's −5/3 scaling law |

The velocity profiles with non-dimensional flow depth (z/h) around the piers of 75 mm and 90 mm diameter for no seepage and seepage runs are shown in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 respectively where z is flow depth from bed surface. As indicated in the Fig. 1, measurements have been taken at upstream (A) and downstream (C) along with both sides (B and D) of the pier. The trend of velocity profile (sections A and C) shown in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 As shown in the Fig. 3 and Fig. 4, reversed velocity occurs inside the scour hole confirming the presence of horseshoe vortex at upstream of the pier. The stream wise velocity component becomes positive as the distance from the bed increases (z/h > 0.1). The maximum velocity occurred roughly on the edge of the scour hole (z/h≈0.4). The stream flow is obstructed by the pier and it comes to rest at face of the pier which causes adverse pressure gradient. Owing to it, a strong downward flow is being observed at regions close to the bed. The downward flow impinges on the bed, erodes the bed material around the pier and the circulating flow along the sides of the pier carries the eroded bed material further hence develops the scour hole. Once the scour is initiated, the downflow close to the pier moves in reverse direction to that of stream flow, near the bed with in the developing scoured hole and dislodges the material from the slanting slope of the scour hole. Reversal flow can be seen near the bed with in the scour hole hence the negative streamwise velocity component at upstream of the pier. The decreasing pressure gradient at the upstream face of the pier accelerates the stream flow along the sides of the pier leads to generate wake vortices at the downstream of the pier which initiates scouring of the bed material at the downstream of the pier. At the downstream of the pier, the streamwise velocity component increases and attains its maximum value near the edge of scour hole (z/h≈ 0.35). At free surface, reversal flow can be seen. At the sections B and D, the velocity profile follows the universal logarithmic profile as shown in Fig. 3(e). The non-dimensional expression of the log law is given as (Deshpande and Kumar, 2016)

| $\frac{u}{{{u_*}}} = \frac{1}{k}\ln \left({\frac{{{z^ + } + \Delta {z^ + }}}{{{x^ + }}}} \right)$ | (7) |

where, u* is shear velocity

|

| (a) Upstream A, (b) Downstream C, (c) Section B, (d) Section D, (e) Logarithmic Figure 3 Velocity profiles around pier with 75mm dia. |

|

| (a) Upstream A, (b) Downstream C, (c) Section B, (d) Section D Figure 4 Law for velocity distributions 90mm dia. |

Downward seepage in channel shifts the velocity profile towards downward which leads to increase in velocity near the bed and boundary shear stress which results in more sediment movement near the bed. With application of seepage, at upstream of the pier velocity profiles shifts downwards which limits the flow reversal zone when compared to the no seepage condition. It should be noted here that seepage is applied all along the flume contrary to point suction available in the literature. Thus there is movement of bed particles from the upstream zone, which reduces the upstream scour hole depth and increases the dune deposition on the downstream side (Sarkar et al., 2015). Application of downward seepage reduces flow reversal near free surface and increases the near bed velocity. At sections B and D, it can be seen clearly that near the bed, velocity is increasing on application of downward seepage. On application of 10% seepage and 20% seepage, velocity is increased on an average value of 15% and 25% respectively.

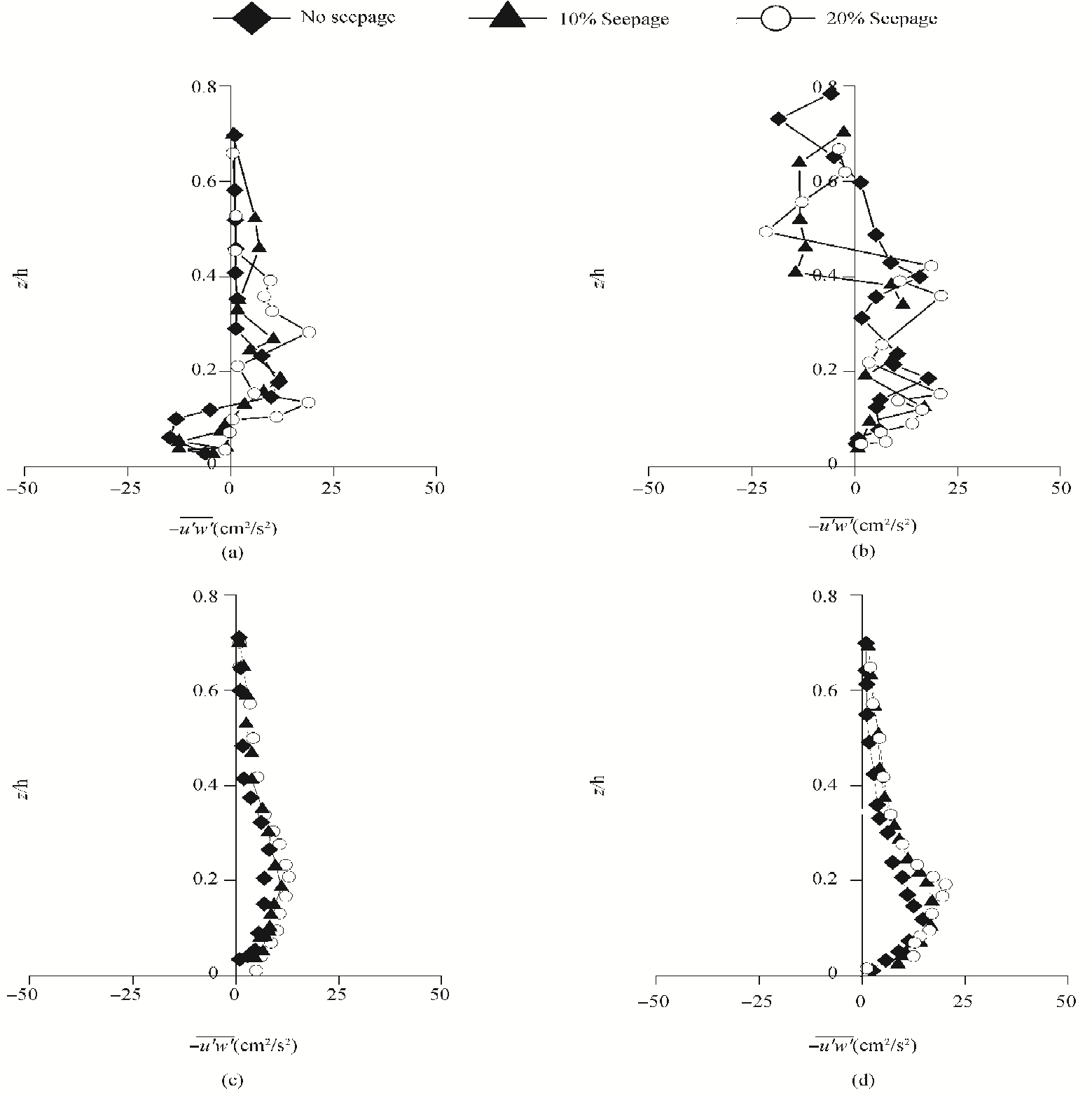

3.2 Reynolds Shear StressReynolds shear stress (RSS) profiles around the piers are shown in Figs. 5 and 6.

|

| (a) Upstream A, (b) Downstream C, (c) Section B, (d) Section D Figure 5 RSS profiles around pier with 75mm dia. |

|

| (a) Upstream A, (b) Downstream C, (c) Section B, (d) Section D (e) Distribution Figure 6 RSS at zero pressure gradient profiles around pier with 90mm dia. |

At the side sections of the piers (Section B and D), maximum Reynolds shear stress occurs near bed. Fig 6(e), shows that distribution of RSS for both no seepage and seepage runs at side sections B and D is accordant with the linear law of RSS for free surface flow with zero pressure gradient. RSS increase with increase in distance from the free surface, attains maximum value somewhere between 0.15 < z/h < 0.25 and then again decreases towards the bed because of the presence of roughness sub layer.

At the upstream (A) and downstream (C) of the pier RSS fluctuates heavily owing to continuous development of vortex region (Figs. 5 and 6). Presence of downward seepage increases the Reynolds shear stress and thereby increases in sediment transport. It is found that on application of downward seepage, Reynolds shear stress

The characteristic of bursting events are studied with conditional statistic of u' and w' by plotting them in plane (Lu and Willmarth, 1973) to evaluate the total Reynolds stress at a single point as the sum of contribution from different types of events. The bursting events are defined by four quadrants (Maity and Muzumder, 2012) (q=1, 2, 3 and 4) as, (1) outward interaction

The bursting phenomenon is described by two significant features ejection and sweep. Ejection is upward entrainment of low speed fluid particles into the main turbulent flow, as instantaneous velocity is lower than time averaged local velocity. During sweep event these ejected low speed fluid particles are brushed away by high speed fluid particles. Sweep is the downward movement of high speed fluid particles towards the bed. A parameter H called hole size that represent the threshold level (Nezu and Nakagawa 1993) and is given by Eq. (5):

| $\left| {u'w'} \right| = H\sqrt {\overline {u{'^2}} } \sqrt {\overline {w{'^2}} } $ | (8) |

The Hole region H=0 means all data

| $u'w{'_{q, H}} = \mathop {\lim }\limits_{T \to \infty } \frac{1}{T}\mathop \smallint \limits_0^T u'\left(t \right)w'\left(t \right){I_{q, H}}\left({z, t} \right){\rm{d}}t$ | (9) |

where t is time, T is sampling duration, Iq, His the indicator function define as:

| $\begin{array}{l} {I_{q, H}}\left[ {u'(t)w'(t)} \right] = \\ \left\{ \begin{array}{l} 1, \, \, {\rm{if}}(u', w')\, {\rm{is}}\, {\rm{in}}\, {\rm{quadrant}}\, {\rm{q}}\, {\rm{and}}\, \left| {u'w'} \right| \ge H{\left({\overline {u{'^2}} } \right)^{0.5}}{\left({\overline {w{'^2}} } \right)^{0.5}}\\ 0, \, {\rm{otherwise}} \end{array} \right. \end{array}$ | (10) |

Reynolds shear stress fractional contribution to each event is given by:

| ${S_{q, H}} = \frac{{u'w{'_{q, H}}}}{{\overline {u'w'} }}$ | (11) |

Sq, H is positive in case of sweeps and ejection while it is negative in case of outward and inward interactions. Sweeps and ejection occurs when q is even and outward and inward interactions occur when q is odd. For H=0:

| ${S_{10}} + {S_{20}} + {S_{30}} + {S_{40}} = 1$ | (12) |

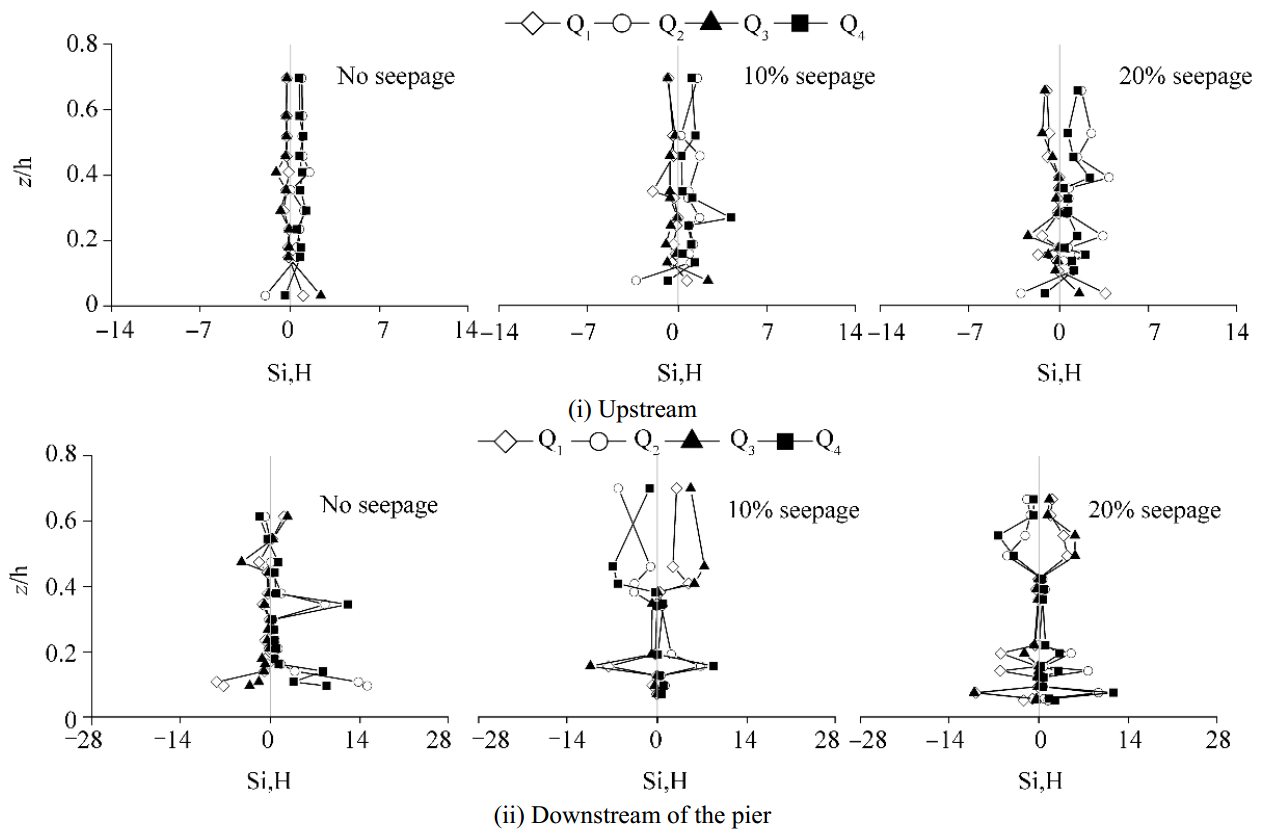

Systematic variation of the hole size H allows the investigation of the contributions of events to the total Reynolds shear stress, whether they are large, small or frequent. Fig. 7 shows variation of stress fraction against z/h at upstream and downstream of the pier with 75 mm diameter for no seepage, 10% seepage, 20% seepage at H=0.

|

| Figure 7 Stress fraction Si, H against z/h for H=0 at (ⅰ) Upstream (ⅱ) Downstream of the pier |

From Fig. 7, the contribution of events Q1 and Q3 is more than Q2 and Q4 within the scour hole region (z/h < 0.1) at upstream of the pier. As the flow in the scour hole does not have sufficient capability to move the particles further, the particles near the bed are lifted up by the flow instead of transporting along with flow and returned back to the bed. Sweep and ejection events are more dominant around edge of scour hole and above. The dominance of sweep results in arrival of high speed fluid particles contributing greater in stream wise direction and greater in vertical direction, which causes the progressively deepening the scour hole at upstream of the pier. Ejection events are pronounced at downstream side of the pier. It is observed that the fluctuations of stress fraction are increased near bed in the scour region due to complexity of flow and decreased towards the surface. The magnitude of events is stronger at downstream of the pier than upstream because of the higher turbulence production at the downstream of the pier. Similar results are obtained for pier with 90 mm diameter.

Analysis of bursting events shows that contribution of events inward interaction, outward interaction, ejection and sweep to the Reynolds shear stress are increased in case of seepage as compared to no seepage runs as shown in Fig. 7. On application of downward seepage, it can be seen that contribution of ejection event is more resulting in arrival of low speed fluid particles due to retardation of flow in stream wise direction. The magnitude of stress fraction is increased with the increased of seepage as compared to that with no seepage run. While moving away from the bed, it is observed that contribution of ejection and sweep to the Reynolds shear stress are greater than inward and outward interaction. On application of seepage contribution of ejection events increased and accompanied by decrease in sweep events.

3.4 Integral scale of flowGyr and Schmid (1989) detected that origin of bedform is due to the dominance of sweep events in the vicinity of bed which are directly linked with Coherent structures of the turbulent flow. The origin of bed deformation is correlated with integral scale of flow in near bed region (Venditti et al. 2005, Patel et al. 2015). In the present experiments scour depth of pier is observed at the upstream and downstream end of the pier for both no seepage and seepage runs. The time scale and integral length scale were calculated for the near-bed velocity of the no seepage, 10% seepage and 20% seepage runs in order to describe the changes in the scour depth after the application of seepage. Integral time scale and length scale are calculated at ≈ 5mm above the bed using the 300 s time series data collected at the same point. The Eulerian integral time scale is expressed as:

| ${E_T} = \int\limits_0^j {R\left(t \right)} {\rm{d}}t$ | (13) |

where, R(t) is the auto-correlation function, dt is the lag distance, and j is the time at which R(t) started to oscillate about zero (Tennekes and Lumley, 1972). Autocorrelation was calculated using linear interpolation by converting the time series into regularly spaced events. Value of j was calculated based on autocorrelation at which R(t) ≈ 0.01 and lag time is 0.01 s. The Eulerian integral length scale (Taylor 1935) is defined as:

| ${E_L} = {E_T}u$ | (14) |

where, u is time average Velocity.

Value of ET and ELare represented in Table 2 which shows that integral length and time scale in the near bed flow zone increased significantly with downward seepage which further suggest that eddy size is increased in the vicinity of bed surface with the application of seepage. At upstream of the pier, integral length scale is increased by 8.77% with 10% seepage and 26.30% with 20% seepage as compared to that with no seepage flow. Further, at the downstream of pier, integral scale with seepage becomes approximately twice than those with no seepage run. Venditti et al. (2005) observed that larger size of eddies in the vicinity of the bed is responsible for initiation of bed features. Increased eddy size in the near-bed region tends to higher momentum and energy transfer and less destruction of turbulent motions. Thus higher levels of turbulence achieved near the bed with an increased eddy size resulting higher scour depth of pier with downward seepage.

| For U/S of Φ 75mm pier at 5 mm vicinity of the bed surface | |||

| Case | Time-mean velocity (u), / (m∙s−1) | Eulerian time scale (ET) / s | Eulerian length scale (EL) / m |

| No Seepage | −0.0193 | 2.94 | −0.057 |

| 10% Seepage | −0.0164 | 3.20 | −0.052 |

| 20% Seepage | −0.0114 | 3.69 | −0.042 |

| For D/S Φ 75 mm of pier at 5 mm vicinity of the bed surface | |||

| Case | Time-mean velocity (u)/ (m∙s−1) | Eulerian time scale (ET) / s | Eulerian length scale (EL) / m |

| No Seepage | 0.0867 | 1.34 | 0.11 |

| 10% Seepage | 0.075 | 4.44 | 0.33 |

| 20% Seepage | 0.0696 | 5.22 | 0.36 |

Transportation of sediments leads to change the morpho-dynamical conditions of the alluvial channel which can be observed in the form of aggradation and degradation of channel boundaries. Reduction of channel cross-sectional area that arises due to construction of structures such as bridge piers obstruct the stream flow and leads to excavate and remove the sediments around the structures. The flowing water is impeded by the bridge piers due to which the flow separated in three directions, the modifications in flow pattern in such a way as to cause inflation in shear stress which dislodge the stream bed material around piers and resulting in scour. The scouring around bridge piers is time dependent phenomenon. The development of vortex around pier with time is being considered as the primary source for scour depth. With increasing time, scour depth increases up to certain limit, later on erosive capability of flowing stream and resistance to the motion of bed material attains equilibrium. Fig. 8 shows lateral bed profiles at upstream and downstream of the pier which are measured with Ultrasonic ranging system at different time intervals. The measurements are taken for 20cm transverse distance at upstream and downstream of the pier by considering the centre of pier as centre of that transverse distance. The flow obstructed by pier erodes the bed material around the pier in longitudinal and transverse direction for both no seepage and seepage runs. Lateral flow occurs through the boundaries of alluvial channels in the form of seepage which also affect the flow characteristics of the main stream flow and rate of sediment transport. With progressing time, the scour depth enlarged at upstream and downstream of the pier. From Fig. 8, it can be seen that initially the change of scour depth is very large for both no seepage and seepage conditions, and reduces gradually with time. It can be seen from Fig. 8, rate of scour depth formation reduces by 50% in 12 hours. However, rate of scour depth development in no seepage runs is faster when compared to seepage runs, the reason could be the strength reduction of reserve flow in seepage runs as indicated by velocity profile.

|

| Figure 8 Development of scour depth with time at (A) upstream (B) downstream of the pier |

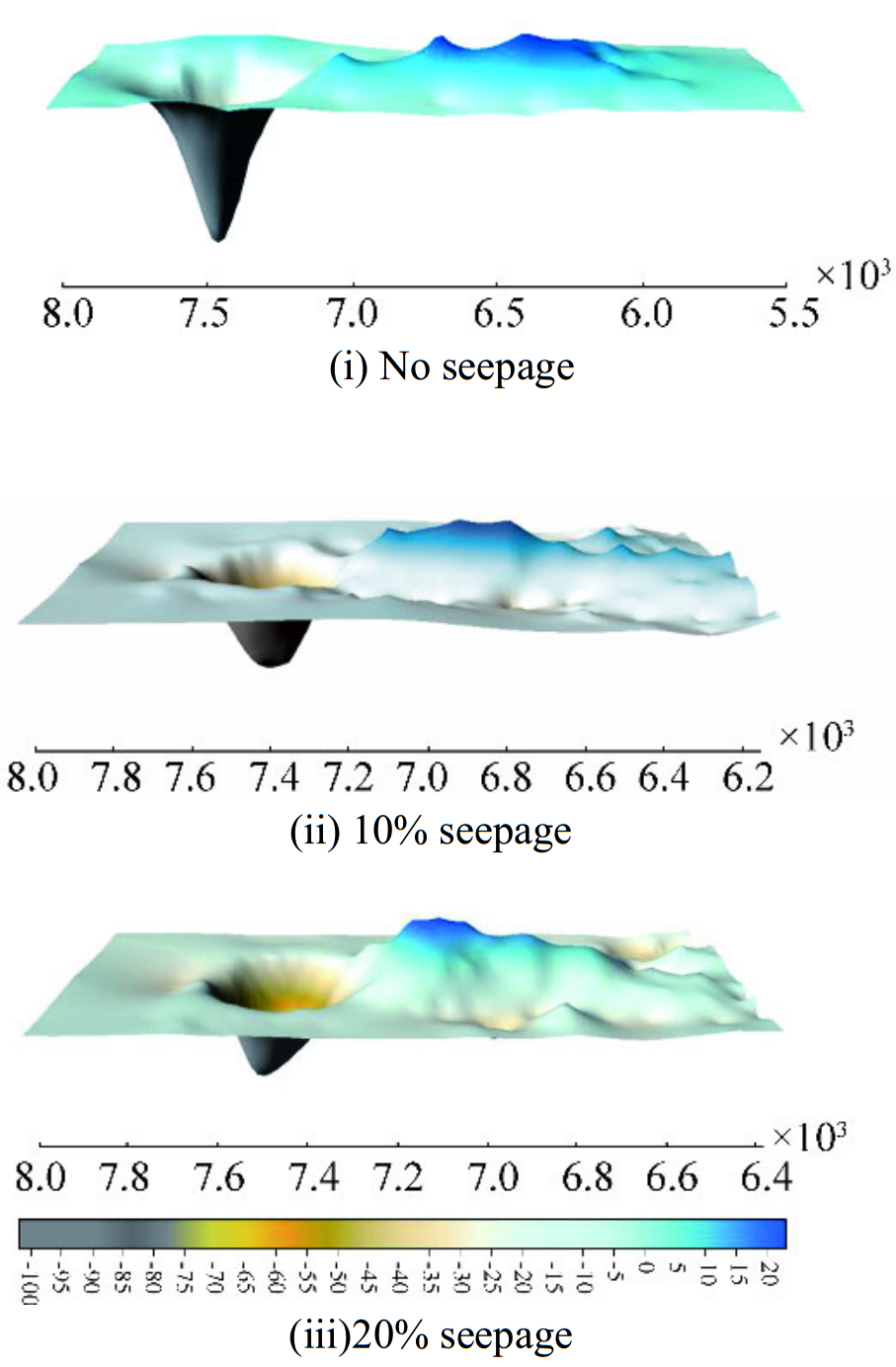

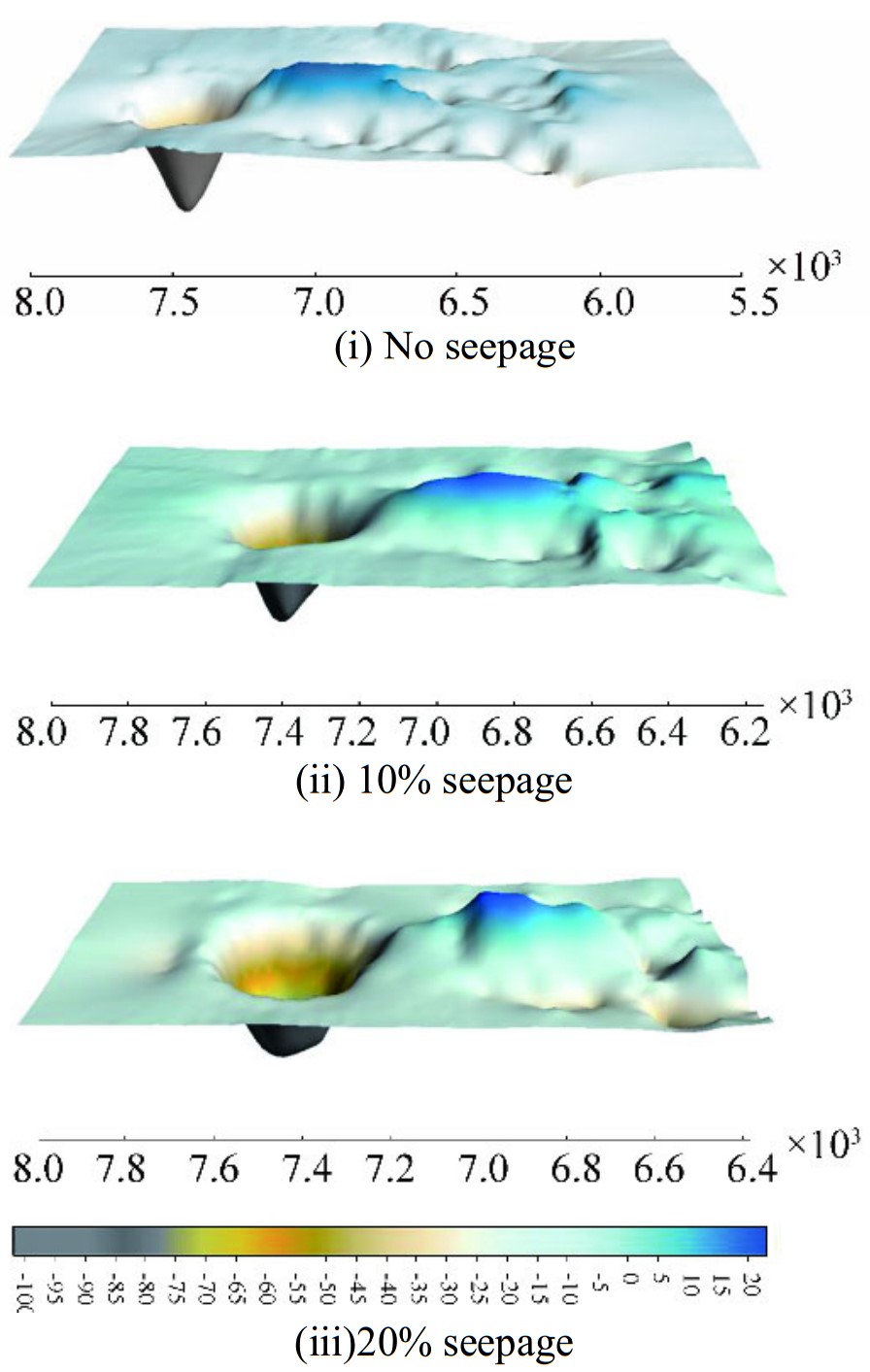

Figs. 9 and 10 show the bed morphology after scouring around pier of diameter 75mm and 90 mm respectively. It can be seen from Figs. 9 and 10, the scour depth at upstream of the pier is greater in case of no seepage condition and it is reduced by 36% and 45% in case of 10% seepage and 20% seepage respectively.

|

| Figure 9 Bed morphology after scouring around pier with 75mm |

|

| Figure 10 Bed morphology after scouring around pier with 75mm and 90 mm |

The observed scour depth as shown in Figs. 9 and 10 for both piers has been compared with Shen et al. (1969) and Jain (1981) formulae, which is given in the Table 3. Calculated and observed scour depth for each run is represented in Table 3 which demonstrates that Jain (1981) can be pertinent for no seepage condition yet not relevant for seepage conditions as it overpredicts the scour depth around 20 to 35%. Whereas Shen et al; (1969) overpredicts the scour depth around 11 to 25% and 39 to 58% in no seepage and seepage runs.

| Case | Scour depth predicted / mm | Scour depth observed / mm | ||||

| Jain (1981) | Shen et al.(1969) | |||||

| Φ75 mm | Φ90 mm | Φ75 mm | Φ90 mm | Φ75 mm | Φ90 mm | |

| No Seepage | 86.16 | 97.87 | 111.8 | 125.17 | 99.85 | 93 |

| 10% Seepage | 85.3 | 96.9 | 110.6 | 123.8 | 68 | 64.2 |

| 20% Seepage | 84.44 | 95.92 | 109.5 | 122.63 | 55.4 | 52.3 |

The bed material scoured around the pier, deposited at the rear side of the pier and extends along the centreline and on both sides of the centreline which produces hump at the downstream region. The eroded bed material around the pier is accumulated behind pier producing dune like bedforms, which significantly modifies the bed morphology. Interpretation of the bedform geometry seems important in waterway designing as they compel the stream resistance and obstructs the flow at rear side of pier. With respect to the sediment erosion at downstream of the pier, deposition height is maximum for 20% seepage, decreased by 24% in case of 10% seepage and for no seepage condition reduced by 50% whereas average length of deposition is maximum for no seepage condition which is reduced by 16% in case of 20% seepage and about 12% on application of 10% seepage. Oliveto and Hanger (2014) have proposed a relationship to predict the height of dune crest developed at downstream of the pier.

| $\frac{{{h_{D\max }}}}{{{h_0}}} = 0.25{\left({\frac{D}{{{h_0}}}} \right)^{0.5}}{\sigma ^{ - 0.5}}{F_d}^{0.2}$ | (15) |

where, hDmax is maximum dune crest height, h0 is approach flow depth, Fd is densimetric particle Froude number, D is pier diameter, geometric standard deviation. Table 4 shows the observed and predicted values of height of dune crest for all the runs. The relationship proposed by Oliveto and Hanger (2014) overpredicts the deposition height around 15 to 18% in case of no seepage runs but underpredicts the deposition height by very high percentage (38 to 98%) in seepage runs.

| Case | Φ75 mm | Φ90 mm | ||

| hDmax Predicted /mm | hDmax Observed /mm | hDmaxPredicted /mm | hDmaxObserved /mm | |

| No Seepage | 30.68 | 25.21 | 33.5 | 28.4 |

| 10% Seepage | 23.74 | 32.8 | 25.95 | 33.12 |

| 20% Seepage | 23.04 | 45.8 | 25.18 | 48 |

The experimental study has been carried out to explicate the nature of turbulence flow structure around the bridge pier and change in bed morphology due to the application of downward seepage. The flume experiments were conducted for no seepage, 10% seepage and 20% seepage using piers of 75mm and 90mm diameter. Various results showing distribution of velocity profiles, Reynolds shear stress around piers, Stress fraction at upstream and downstream of the pier and change in bed morphology after scouring are presented for no seepage, 10% seepage and 20% seepage. Following conclusions can be drawn by observing the effect of downward seepage on turbulence parameters and local scour geometry around the pier.

a) In this study velocity profiles were measured along the different section of pier for both no seepage and seepage run from where it is observed that upstream and downstream of the piers are most critical sections for each runs. At upstream of the pier, maximum velocity occurs near the edge of the scour hole, whereas, it occurs near the bed at the downstream of the pier. Downward seepage obstructs the reversal of flow at upstream of the pier resulting in less momentum transfer, which minimizes the scouring of the bed material.

b) The presence of downward seepage leads to an increase in Reynolds shear stress which is upgraded by separation of the stream flow that leads to vortex shedding at the downstream of the pier. Reynolds shear stress fluctuates heavily on application of downward seepage. The Reynolds shear stress turns out to be more negative in the vicinity of bed at upstream of the pier while at downstream of the pier, it occurs near the surface.

c) Contribution of sweep events towards Reynolds shear stress increases with downward seepage at the upstream of the pier, whereas, at the downstream of the pier ejection events become more dominant with seepage which induces the sediments in suspension, to get transported further along the flow.

d) Bridge piers are obstacles in fluvial environments which cause flow separation and prompt scour the bed material around piers. Toward the start of scouring, the rate of expansion in scour depth is progressively and gradually diminishes with development in time. In case of no seepage runs the scour depth achieved is higher, which lessens on application of downward seepage. A fairly good compatibility was seen between observed and numerical results of scour depth obtained from equations Shen et al. (1969) and Jain (1981) for no seepage runs.

e) Migrating dunes like bed forms are generated immediately behind the piers due to deposition of bed material. Oliveto and Hanger (2014) equation is utilized to look at experimental findings and predicted values of height of dune crest which shows that the difference between observed and predicted dune crest height is higher in case of seepage runs. The depth and length of the scour hole decreases with seepage whereas its width increases.

Individuals or units other than authors who were of direct help in the work should be acknowledged by a brief statement following the text

| Aghaee-Shalmani Y, Hakimzadeh H, 2015. Experimental investigation of scour around semi-conical piers under steady current action. European Journal of Environmental and Civil Engineering, 19(6), 717–732. DOI:10.1080/19648189.2014.968742 |

| Ahmed F., Rajaratnam N., 1998. Flow around bridge piers. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 124(3), 288–300. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1998)124:3(288) |

| Ansari SA, Kothyari UC, Ranga Raju KG, 2002. Influence of cohesion on scour around bridge piers. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 40(6), 717–729. DOI:10.1080/00221680209499918 |

| Avent RR, Alawady M, 2005. Bridge scour and substructure deterioration:Case study. Journal of Bridge Engineering, 10(3), 247–254. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)1084-0702(2005)10:3(247) |

| Baker CJ, 1981. New design equations for scour around bridge piers. Journal of the Hydraulics Division, 107(4), 507–511. |

| Breusers H, Nicollet G, Shen H, 1977. Local scour around cylindrical piers. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 15(3), 211–252. DOI:10.1080/00221687709499645 |

| Cao D, Chiew YM, 2013. Suction effects on sediment transport in closed-conduit flows. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 140(5), 04014008. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)HY.1943-7900.0000833 |

| Chang WY, Lai JS, Yen CL, 2004. Evolution of scour depth at circular bridge piers. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 130(9), 905–913. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2004)130:9(905) |

| Chen X, Chiew YM, 2004. Velocity distribution of turbulent open-channel flow with bed suction. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 130(2), 140–148. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2004)130:2(140) |

| Chiew YM, Lim FH, 2000. Failure behavior of riprap layer at bridge piers under live-bed conditions. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 126(1), 43–55. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2000)126:1(43) |

| Chiew Y, Melville B, 1987. Local scour around bridge piers. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 25(1), 15–26. DOI:10.1080/00221688709499285 |

| Chiew YM, 2004. Local scour and riprap stability at bridge piers in a degrading channel. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 130(3), 218–226. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2004)130:3(218) |

| Corvaro S, Miozzi M, Postacchini M, Mancinelli A, Brocchini M, 2014a. Fluid-particle interaction and generation of coherent structures over permeable beds:an experimental analysis. Advances in Water Resources, 72, 97–109. DOI:10.1016/j.advwatres.2014.05.015 |

| Corvaro S, Seta E, Mancinelli A, Brocchini M, 2014b. Flow dynamics on a porous medium. Coastal Engineering, 91, 280–298. DOI:10.1016/j.coastaleng.2014.06.001 |

| Deshpande V, Kumar B, 2016. Turbulent flow structures in alluvial channels with curved cross-sections under conditions of downward seepage. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. |

| Devi TB, Kumar B, 2015. Turbulent flow statistics of vegetative channel with seepage. Journal of Applied Geophysics, 123, 267–276. DOI:10.1016/j.jappgeo.2015.11.002 |

| Dey S, Sarkar A, 2007. Effect of upward seepage on scour and flow downstream of an apron due to submerged jets. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 133(1), 59–69. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2007)133:1(59) |

| Dey S, Das R, Gaudio R, Bose SK, 2012. Turbulence in mobile-bed streams. Acta Geophysica, 60(6), 1547–1588. DOI:10.2478/s11600-012-0055-3 |

| Ettema R, 1980. Scour at Bridge Piers. Report No. 216, University of Auckland, School of Engineering, Auckland, New Zealand, 527. |

| Francalanci S, Parker G, Solari L, 2008. Effect of seepage-induced nonhydrostatic pressure distribution on bed-load transport and bed morphodynamics. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 134(4), 378–389. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2008)134:4(378) |

| Garde R, Kothyari U, 1998. Scour around bridge piers. Proceedings-Indian National Science Academy PART A, 64, 569–580. |

| Goring DG, Nikora VI, 2002. Despiking acoustic Doppler velocimeter data. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 128(1), 117–126. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2002)128:1(117) |

| Graf W, Istiarto I, 2002. Flow pattern in the scour hole around a cylinder. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 40(1), 13–20. DOI:10.1080/00221680209499869 |

| Grimaldi C, Gaudio R, Calomino F, Cardoso AH, 2009. Countermeasures against local scouring at bridge piers:slot and combined system of slot and bed sill. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 135(5), 425–431. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)HY.1943-7900.0000035 |

| Gyr A, Schmid A, 1989. The different ripple formation mechanism. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 27(1), 61–74. DOI:10.1080/00221688909499244 |

| Izadinia E, Heidarpour M, Schleiss AJ, 2013. Investigation of turbulence flow and sediment entrainment around a bridge pier. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment, 27(6), 1303–1314. DOI:10.1007/s00477-012-0666-x |

| Jain SC, 1981. Maximum clear-water scour around circular piers. Journal of the Hydraulics Division, 107(5), 611–626. |

| Kinzli KD, Martinez M, Oad R, Prior A, Gensler D, 2010. Using an ADCP to determine canal seepage loss in an irrigation district. Agric. Water Manag., 97(6), 801–810. DOI:10.1016/j.agwat.2009.12.014 |

| Kothyari U, Ranga Raju K, Garde R, 1992. Live-bed scour around cylindrical bridge piers. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 30(5), 701–715. DOI:10.1080/00221689209498889 |

| Kothyari UC, 2008. Bridge scour:status and research challenges. ISH Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 14(1), 1–27. DOI:10.1080/09715010.2008.10514889 |

| Krishnamurthy K, Rao S, 1969. Theory and experiment in canal seepage estimation using radioisotopes. Journal of Hydrology, 9(3), 277–293. DOI:10.1016/0022-1694(69)90022-5 |

| Kumar V, Raju KGR, Vittal N, 1999. Reduction of local scour around bridge piers using slots and collars. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 125(12), 1302–1305. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1999)125:12(1302) |

| Lagasse PF, 2007. Countermeasures to protect bridge piers from scour (Vol. 593): Transportation Research Board, 1-111. |

| Laursen EM, Toch A. 1956. Scour around bridge piers and abutments (Vol. 4). Iowa Highway Research Board Ames, Iowa. |

| Lu SS, Willmarth WW, 1973. Measurements of the structure of the Reynolds stress in a turbulent boundary layer. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 60(03), 481–511. DOI:10.1017/S0022112073000315 |

| Maity H, Mazumder B, 2012. Contributions of burst-sweep cycles to Reynolds shear stress over fluvial obstacle marks generated in a laboratory flume. International Journal of Sediment Research, 27(3), 378–387. DOI:10.1016/S1001-6279(12)60042-0 |

| Marsh NA, Western AW, Grayson RB, 2004. Comparison of methods for predicting incipient motion for sand beds. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 130(7), 616–621. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2004)130:7(616) |

| Martin CA, Gates TK, 2014. Uncertainty of canal seepage losses estimated using flowing water balance with acoustic Doppler devices. J. Hydrol. 517, 746, 746–761. DOI:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.05.074 |

| Masjedi A, Bejestan MS, Esfandi, A, 2010. Experimental study on local scour around single oblong pier fitted with a collar in a 180 degree flume bend. International Journal of Sediment Research, 25(3), 304–312. DOI:10.1016/S1001-6279(10)60047-9 |

| Melville B, Sutherland A, 1988. Design method for local scour at bridge piers. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 114(10), 1210–1226. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1988)114:10(1210) |

| Melville BW, Coleman SE, 2000. Bridge scour: Water Resources Publication, 550 |

| Oliveto G, Hager WH, 2014. Morphological evolution of dune-like bed forms generated by bridge scour. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 140(5), 06014009. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)HY.1943-7900.0000853 |

| Patel M, Deshpande V, Kumar B, 2015. Turbulent characteristics and evolution of sheet flow in an alluvial channel with downward seepage. Geomorphology, 248, 161–171. DOI:10.1016/j.geomorph.2015.07.042 |

| Qadar A, 1981. The vortex scour mechanism at bridge piers. ICE Proceedings, 739-757. |

| Qi M, Chiew YM, Hong JH, 2012. Suction effects on bridge pier scour under clear-water conditions. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 139(6), 621–629. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)HY.1943-7900.0000711 |

| Raikar RV, Dey S, 2008. Kinematics of horseshoe vortex development in an evolving scour hole at a square cylinder. Journal of hydraulic research, 46(2), 247–264. DOI:10.1080/00221686.2008.9521859 |

| Rao AR, Sitaram N, 1999. Stability and mobility of sand-bed channels affected by seepage. Journal of Irrigation and Drainage Engineering, 125(6), 370–379. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9437(1999)125:6(370) |

| Raudkivi AJ, Ettema R, 1983. Clear-water scour at cylindrical piers. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 109(3), 338–350. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(1983)109:3(338) |

| Sarkar K, Chakraborty C, Mazumder B, 2015. Space-time dynamics of bed forms due to turbulence around submerged bridge piers. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment, 29(3), 995–1017. DOI:10.1007/s00477-014-0961-9 |

| Shen HW, Schneider VR, Karaki S, 1969. Local scour around bridge piers. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 95(6), 1919–1940. |

| Shukla MK, Misra GC, 1994. Canal discharge and seepage relationship. Proc. , 6th Nat Symposium on Hydro. NIH, Shilong, India, 263-274. |

| Tanji KK, Kielen, NC, 2002. Agricultural drainage water management in arid and semiarid areas. Irrig. Drain. Paper 61. FAO, Rome. |

| Taylor GI, 1935. Statistical theory of turbulence. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London A:Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 151(873), 421–444. DOI:10.1098/rspa.1935.0158 |

| Tennekes H, Lumley JL, 1972. A first course in turbulence. MIT press. |

| Venditti JG, Church MA, Bennett SJ, 2005. Bed form initiation from a flat sand bed. Journal of Geophysical Research:Earth Surface, 110(F1), F01009. DOI:10.1029/2004JF000149 |

| Wilcox DC, 2006. Turbulence modeling for CFD. 3rd edition, La Canada, CA, USA: DCW Industries124-126. |

| Yalin MS, 1972. Mechanics of sediment transport. Oxford: Pergamon Press290. |

| Zarrati AR, Gholami H, Mashahir MB, 2004. Application of collar to control scouring around rectangular bridge piers. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 42(1), 97–103. DOI:10.1080/00221686.2004.9641188 |

| Zarrati A.R., Nazariha M., Mashahir M.B., 2006. Reduction of local scour in the vicinity of bridge pier groups using collars and riprap. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 132(2), 154–162. DOI:10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2006)132:2(154) |

| Zhao Y, Zong Z, Zou L, Wang TL, 2015. Turbulence model investigations on the boundary layer flow with adverse pressure gradients. Journal of Marine Science and Application, 14(2), 170–174. DOI:10.1007/s11804-015-1303-0 |

| Zhuang Y, Liu ZY, 2007. Experimental study on the width of the turbulent area around bridge pier. Journal of Marine Science and Application, 6(1), 53–57. DOI:10.1007/s11804-007-6048-y |