2. National Engineering Research Center of Shanghai ship Design Technology, Shanghai 200080, China

1 Introduction

With the increasingly strict requirements in shipbuilding to consider energy conservation, researchers and practioners are now focusing on the use of electric propulsion and other energy-efficient propulsion technologies. In this respect, podded propulsors not only deliver an excellent hydrodynamic performance but also have considerable advantages over other technologies with respect to overall propulsion efficiency, fuel consumption, and energy savings.

Early research on podded propulsors mainly involved potential flow theory methods, including the lifting surface method and the panel method. For example, Cheng et al. (1989) employed an actuator disk model in simulating the steady flow of a propeller, and Kawakita et al. (1994) used the low-order panel method to analyze the performance of the propulsor pod and strut. In addition, Han et al. (2000) combined the low-order panel method with a vortex lattice method to simulate the hydrodynamics of the propeller blade, strut, pod, and fin. Furthermore, Szantyr (2001) investigated the hydrodynamic performance of a tandem-type podded propulsor using a numerical model established by the panel method, and the calculated values were found to be consistent with the experimental results.

With the development of computers, researchers paid increasing attention to methods used to solve Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations. For example, Chicherin et al. (2004) conducted a preliminary analysis of scale-affected podded propulsors using RANS equations and investigated the influences of different advance coefficients and Reynolds numbers on pods and struts; results suggested that the scale factor was a more effective predictor of the resistance performance of propulsors than the shape factor. Ohashi and Hino (2004) studied the performance of a contra-rotating podded propulsor with fore and aft propellers using the RANS equations. In this study, they treated a propulsor pod unit with a detached propeller as a stern appendage; a comparison between calculated and test results showed the proposed method improved the accuracy of ship resistance calculations but worsened the prediction accuracy for wake fraction and the calculation accuracy of thrust deduction.

MARIN and HSVA tank tests have been used in previous experimental studies where the hydrodynamic performance of podded propulsors was examined, and preliminary testing procedures for podded propulsors in open-water conditions have been established (ITTC, 2002). Reichel (2007) tested a pusher podded propulsor with a right-handed propeller in a towing tank and analyzed the propulsor thrust and torque at various azimuthing angles; results showed that the fluctuation of the side force on the propulsor during azimuthing conditions at an angle of approximately 15° to the right was greater than that at other yaw angles. The hydrodynamic characteristics of podded propulsors at a specific angle with the inflow at different advance coefficients were compared, and the thrust and side forces in left-handed and right-handed azimuthing conditions were also compared. It was found that at larger yaw angles, interactions between the propeller and pod had more significant effects on the thrust and side forces on the podded propulsor. Islam et al. (2007) conducted experiments with puller and pusher podded propulsors to investigate the following: effects of the hub taper angle on inflow, thrust, and efficiency; the influence of pod and strut configurations; cavitation performance; the effect of the hub gap; and the hydrodynamic performance of the podded propulsor under static azimuthing conditions. In addition, they conducted a preliminary analysis of factors affecting the experimental accuracy and provided some experimental guidance for research on podded propulsors under different azimuthing conditions. Furthermore, Islam et al. (2009) compared the hydrodynamic characteristics of puller podded propulsors in static and dynamic azimuthing conditions and found that results varied primarily with rotations of the propeller and turning of the unit under dynamic azimuthing conditions. They then fitted a tenth-order polynomial model to the experimental results, which was similar to the hydrodynamic curve obtained for static azimuthing conditions. Palm et al. (2011) conducted an experimental test and a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation to investigate variations in the hydrodynamic performance of cycloidal and pusher podded propulsors for straight-ahead motion at various draft depths. They discovered that the pusher podded propulsor was influenced to a greater degree by the draft and that the thrust linearly decreased as the draft decreased, whereas only a portion of the cycloidal propeller blades were significantly affected by draft depth. However, the study by Palm et al. (2011) did not focus much attention on the torque or the flow field, and it did not further investigate the effect of the draft depth on the two types of propulsors under steering conditions.

Sasaki (2008) summarized the reports presented by the Podded Propulsion Committee at the 25thInternational Towing Tank Conference (ITTC). In the conference, partial requirements for the design, testing, and computations of podded propulsors were presented, and the CFD method was described as an important tool for use in propulsor performance prediction and establishment of evaluation criteria. For experimental testing purposes, the conference suggested that the hydrodynamic performance of podded propulsors in off-design conditions should be better-emphasized, particularly with respect to the efficiency loss induced by small azimuthing angles. The conference also noted the current insufficiency of actual ship data for use in related tests and prediction procedures.

Shi et al. (2010) compared and analyzed the rapidity and maneuverability of a single-screw commercial vessel using a traditional propeller-rudder propulsor and podded propulsor. Their study revealed that although a podded propulsor could significantly improve the maneuverability of a single-screw ship at low speeds, the directional stability of the ship would be poor at high speeds; however, this aspect of the ship's performance could be improved by expansion of the lateral projection area of the podded propulsor strut. He et al. (2015) used a modeling method to investigate the performance of tandem-type podded propulsors under straight-ahead and static azimuthing conditions for advance coefficients (J) in the range of 0 to 1.08 and static azimuthing angles in the range of 0° to 90°. In addition, they analyzed the performance of the propeller and the whole pod unit for various static azimuthing angles. Their results showed that the pod unit had a significant influence on the aft propeller but little influence on the fore propeller; in addition, the thrust of the podded propulsor decreased rapidly as the azimuthing angle increased.

2 Description of experiments 2.1 Experimental modelKey dimensions and parameters of the podded propulsor and propeller used in the present experiment are shown in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

| Major axis distance of oblique strut cross section /m | 0.16 |

| Minor axis distance of oblique strut cross section /m | 0.062 |

| Height from oblique strut top surface to axis Y / m | 0.19 |

| Oblique strut angle / (°) | 60 |

| Pod length / m | 0.473 |

| Hub length /m | 0.075 |

| Maximum radius of pod / m | 0.049 |

| Number of blades | 4 |

| Diameter / m | 0.24 |

| Oblique angle / (°) | 35 |

| Pitch ratio (0.7R) | 1.284 |

A towing tank and podded propulsor dynamometer developed by the authors were used for the experiment, which was conducted in two parts: the first part determined the forces and second part evaluated the flow field characteristics. The entire test apparatus was fixed to a trailer, and with the exception of the platform all components could rotate 360° in the horizontal plane to satisfy requirements of different operating conditions. The propeller rotation speed was fixed, and the experiment was conducted by manipulating the forward speed of the trailer.

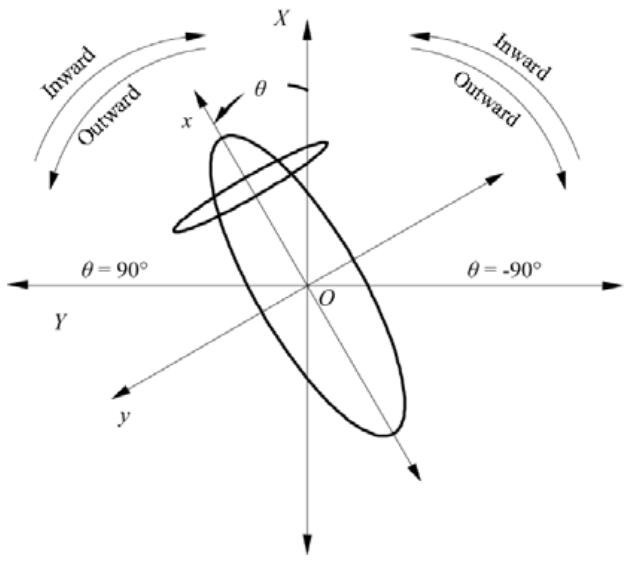

The two coordinate systems used in the tests (a local coordinate system, o-xyz, and a global coordinate system, O-XYZ) are shown in Fig. 1. The local coordinate system was fixed to the podded propulsor unit with the X-axis pointing to the front from the aft pod to the fore pod, and the Y-axis pointing to the left (when observed from the aft pod to the fore pod); the Z-axis was determined based on the right-hand rule. The global coordinate system was fixed to the trailer, which had the same point of origin as the local coordinate system. The X-axis was oriented with the forward direction of the trailer as the positive direction, the Y-axis pointed to the left when looking forward from the trailer tail, and the Z-axis was determined based on the right-hand rule. When the podded propulsor was operated in straight-ahead motion, the two coordinates completely overlapped each other.The intersection angle of the local X-axis and global X-axis under azimuthing conditions was denoted by θ, and the yaw angle of the podded propulsor unit to the right was defined as positive.

|

| Figure 1 Coordinate systems |

The relation between the o-xyz and O-XYZ coordinate systems can be expressed as follows,

| $\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} X\\ Y\\ Z \end{array}} \right] = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\rm{cos}}\theta }&{ - {\rm{sin}}\theta }&0\\ {{\rm{sin}}\theta }&{{\rm{cos}}\theta }&0\\ 0&0&1 \end{array}} \right]\left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} x\\ y\\ z \end{array}} \right]$ | (1) |

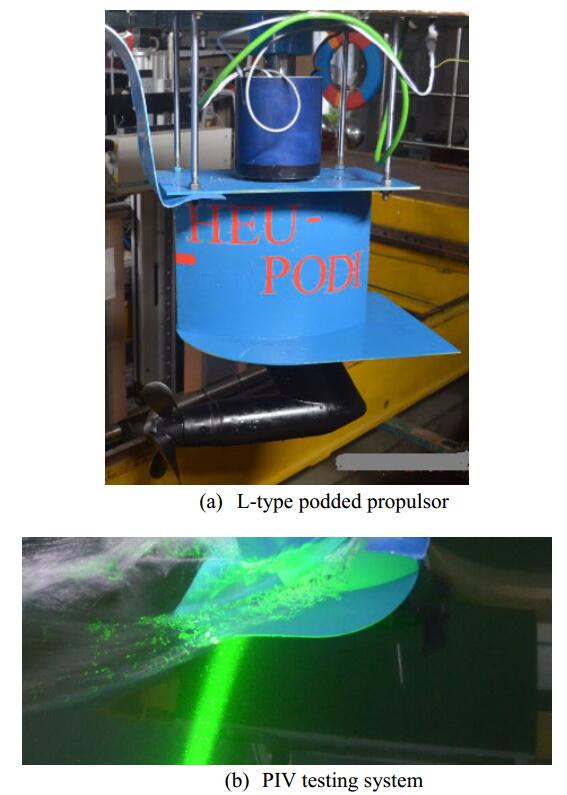

The performance of an L-type podded propulsor in straight-ahead motion, oblique motion, and dynamic azimuthing conditions was analyzed, and the experimental conditions and testing systems are shown in Fig. 2. The trailer advance speed (

|

| Figure 2 L-type podded propulsor testing system |

| $ Re = \frac{{{b_{0.75R}}\sqrt {V_A^2 + {{(0.75{\rm{\pi }}nD)}^2}} }}{\nu } $ | (2) |

where is the section chord length of the propeller blade at 0.75R, VA is the trailer velocity (i.e., the propeller advance speed in straight-ahead motion conditions), n is the propeller rotational speed (D) is the propeller diameter, and v is the kinematic viscosity coefficient of water.

When VA=0, Re≈5.06×105 satisfies the recommendation of the ITTC (that the critical Reynolds number should be greater than 5×105), thereby ensuring that the entire podded propulsor unit is in a turbulent flow field state.

During the experiment, the propeller thrust (T), the propeller torque (Q), the total thrust (Tx), the side force (Ty), and the moment (Mz), on the unit were measured using two dynamometers. Because both dynamometers were rotating with respect to the local coordinate system o-xyz, the corresponding pod unit total thrust (Tx), side force (Ty), and moment (Mz), in the global coordinate system could be calculated according to Eq. (1). To facilitate subsequent analysis and comparisons, the following dimensionless coefficients were defined,

| $ J = \frac{V}{{nD}} $ | (3) |

| $ {K_T} = \frac{T}{{\rho {n^2}{D^4}}} $ | (4) |

| $ {K_Q} = \frac{Q}{{\rho {n^2}{D^5}}} $ | (5) |

| $ \eta = \frac{{{K_T}}}{{{K_Q}}} \cdot \frac{J}{{2\pi }} $ | (6) |

where ρ is the density of water and the other parameters are as previously defined.

The draft depth of the propeller shaft was maintained at 0.4 m > 1.5D, as suggested by the ITTC. The gap between the upper strut and the pressurized water board was set to 2 mm, and the gap between the propeller hub and the pod was set to 1.5 mm. The advance coefficient J, which represents the ratio of the propeller's axial speed to its circumferential speed, is consistent with the conventional definition only under straight-ahead motion conditions. Under static and dynamic azimuthing conditions, this coefficient only indicates that the trailer advance velocity is consistent for each motion condition; the corresponding efficiency is different from that given by the conventional definition.

3 Analysis of experimental results in straight-ahead and static azimuthing conditionsUnder straight-ahead and static azimuthing conditions, the propeller thrust and torque, and the total pod unit thrust, side force, and moment were obtained and non-dimensionalized for use in drawing the propeller's open-water performance curves and unit's performance curves.

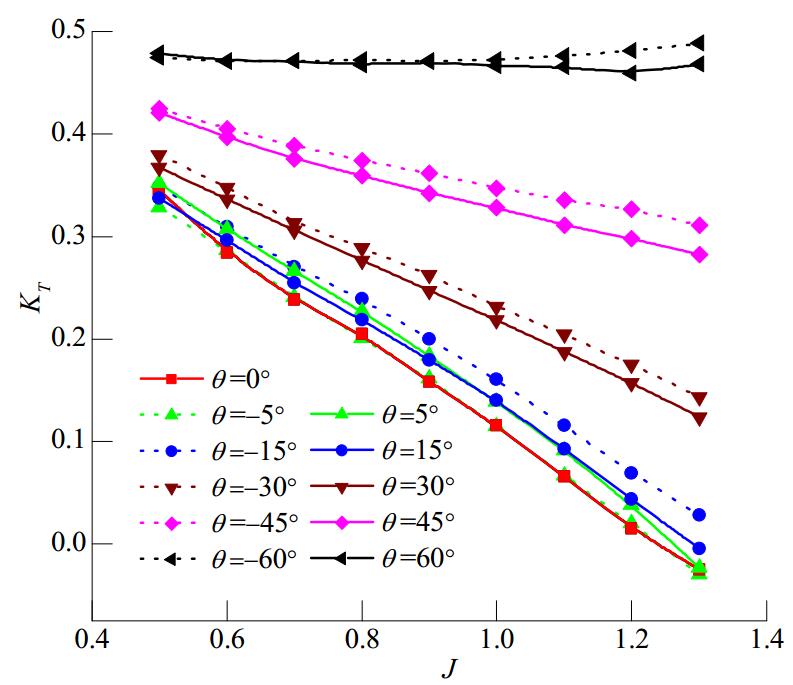

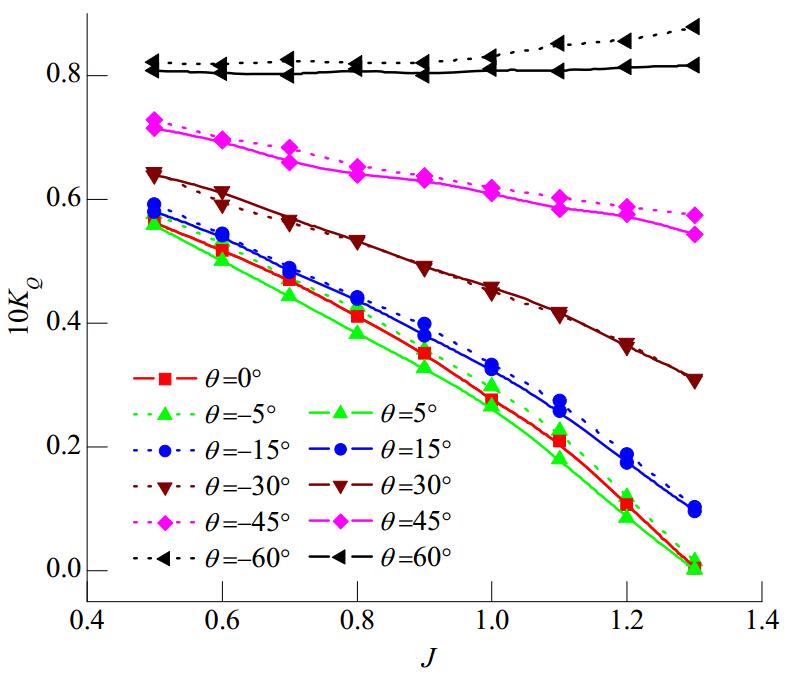

3.1 Propeller force analysisAs shown in Figs. 3 and 4, the advance coefficient varied within a range of 0.5 to 1.3. A negative θ indicates a left-handed azimuth of the podded propulsor, and a positive θ indicates a right-handed azimuth. It can be seen that both the thrust and torque of the podded propulsor, which are affected by the propeller rotation, varied during azimuthing toward the left and right. In addition, except at a yaw angle of 5°, the right-handed propeller generated greater thrust and bore greater loading in left-azimuthing conditions than in right-azimuthing conditions; this phenomenon became more pronounced as the yaw angle increased. However, under static azimuthing conditions there were only relatively slight differences in the propeller thrust and loading at small yaw angles (0°, 5°, and 15°), and both the propeller thrust and loading decreased steadily with an increase in the advance coefficient.

|

| Figure 3 Propeller thrust coefficient versus advance coefficient for various yaw angles |

|

| Figure 4 Propeller torque coefficient versus advance coefficient for various yaw angles |

As the yaw angle increased, the reduction in the propeller axial thrust tended to slow down, and when the angle reached 60° or more, the curve of the propeller axial thrust exhibited a slight upward trend with an increase in the advance coefficient. The torque curve exhibited a similar trend. When the yaw angle of the podded propulsor reached 60°, the propeller thrust generated was approximately five times greater than that generated during straight-ahead sailing, and the torque was approximately three times greater. This is because for the same trailer advance velocity, the inflow component along the propeller axis decreases as the yaw angle increases, which thus increases the difference in the flow velocity between the front and rear propeller disks, thereby increasing the blade thrust and load. Therefore, a ship with a podded propulsor needs to slow down while steering under sail to avoid damage to the transmission system, control system, and main engine, which could easily occur if the propeller torque exceeds the rated value.

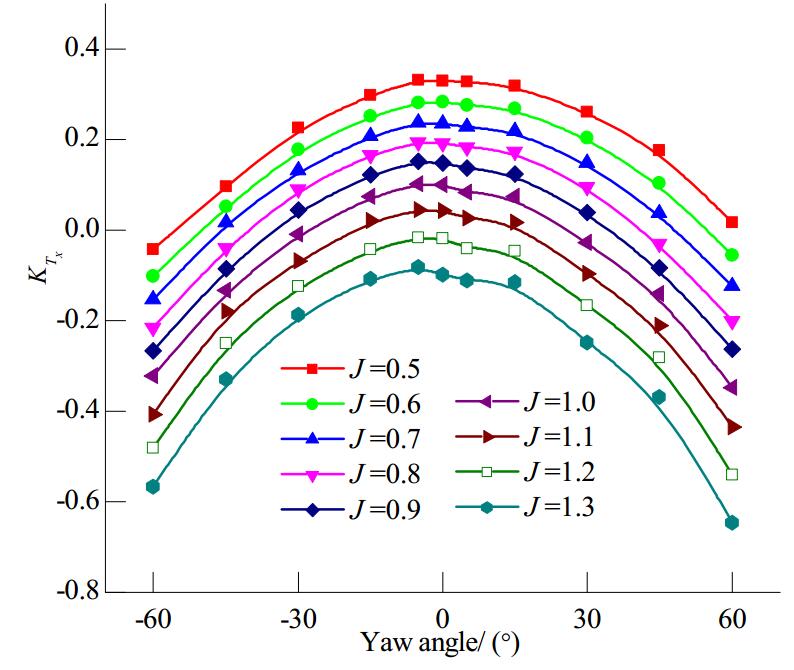

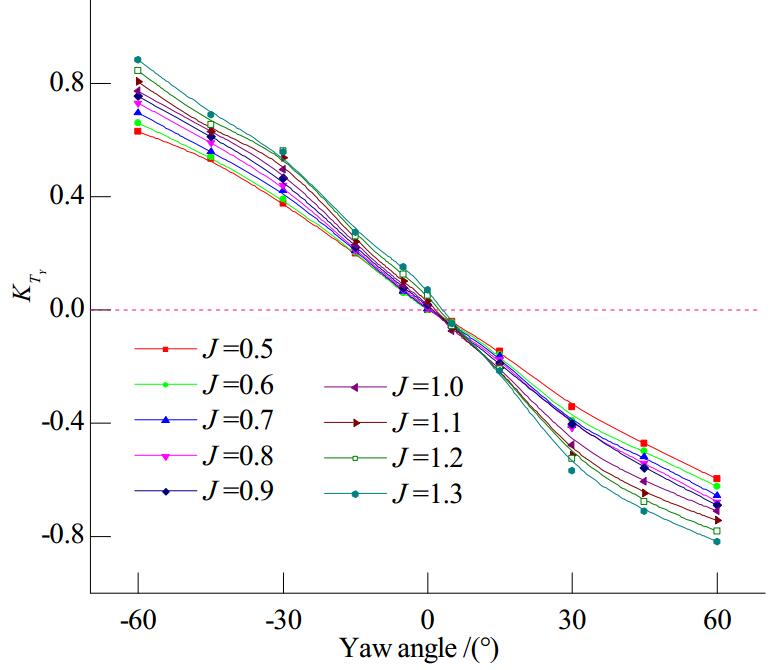

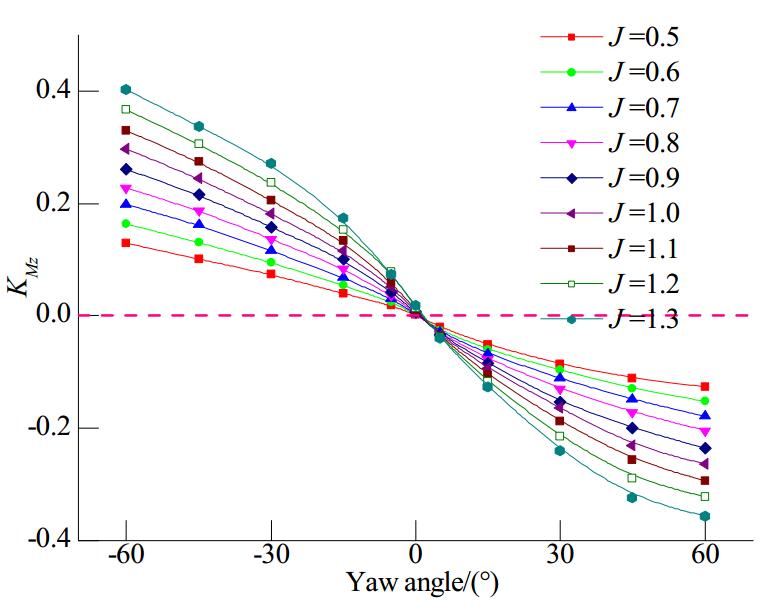

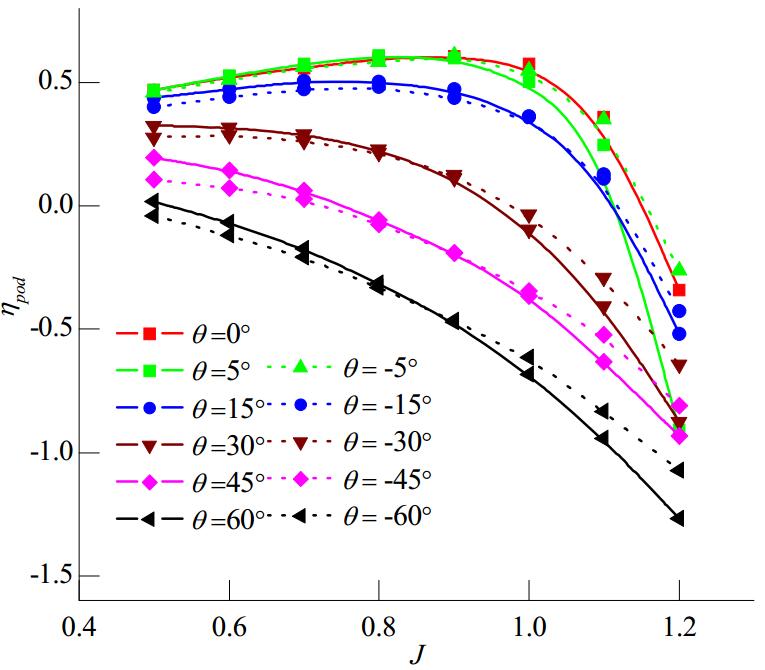

3.2 Force analysis of total pod unitFigures 5 to 8 show the total thrust curves and side force coefficient curves for the pod unit, the moment coefficient curves, and the overall propulsion efficiency curves under static azimuthing conditions, respectively.

|

| Figure 5 Total pod unit thrust coefficient versus yaw angle for various advance coefficients |

|

| Figure 6 Total pod unit side force coefficient versus yaw angle for various advance coefficients |

|

| Figure 7 Total pod unit moment coefficient versus yaw angle for various advance coefficients |

|

| Figure 8 Overall pod unit propulsion efficiency versus yaw angle for various advance coefficients |

As shown in Figure 5, the total pod unit thrust coefficient decreases with an increasing yaw angle for the same trailer advance velocity, and at the same yaw angle the total thrust decreases with an increasing advance coefficient (i.e., trailer advance velocity). When the yaw angle (θ), is smaller than 15°, the total unit thrust changes slightly with an increasing yaw angle and remains positive at low inflow velocities. As the yaw angle increases further, the projection of the strut in the forward direction increases. Current lashing on the strut side leads to an increase in the resistance force, which causes a rapid increase in the entire unit resistance force and a rapid decrease of thrust. When the trailer advance coefficient (J), reaches 1.2, the whole curve becomes negative. The induced wake field, which is influenced by the propeller rotation, varies between porting and starboarding in its interactions with the strut and pod, and thus the total thrust curve is not centrally symmetric but rather slanted to the left, and its maximum value occurs when the yaw angle is approximately −5°.

The side force coefficient curve for the whole unit is shown in Fig. 6, where it can be seen that the overall side force gradually increases with the trailer advance coefficient and pod unit yaw angle (a negative or positive sign merely indicates a different azimuthing direction). For smaller yaw angles (θ≤15°), there is an insignificant change in the side force with a change in the advance coefficient. However, when the yaw angle is greater than 15°, the overall side force varies more significantly with the advance coefficient, although its rate of variation decreases as the yaw angle increases. As with the total thrust curve, the side force is not zero at the middle of the entire curve; it is affected by the propeller rotation and is subjected to small side forces in straight-ahead motion conditions. When the propulsor azimuth is to the right, the side force decreases to zero when the yaw angle is 2°, and the side force then increases with the yaw angle. The podded propulsion moment and side force correspond to each other and exhibit similar trends, as shown in Fig. 7. The effect on the wake field is caused by the propeller rotation in straight-ahead motion, and therefore the pod unit is subjected to a non-zero moment. When the yaw angle is between 0° and 5° to the right, the entire moment is zero, which is approximately consistent with the point at which the side force is zero. As the yaw angle and trailer advance velocity increase, the moment increases, but it does so at a gradually decreasing rate.

The curve for the pod unit propulsive efficiency is similar to that for the conventional open-water propeller propulsive efficiency. In straight-ahead motion, and at small azimuthing angles (θ≤15°), the propulsive efficiency initially increases to an optimal value and then decreases rapidly, even becoming negative, as the advance coefficient increases. When the azimuthing angle exceeds 15°, the increase in the propulsive efficiency is reduced, and beyond a certain yaw angle the propulsive efficiency decreases as the advance coefficient increases. Figure 8 shows that when the advance coefficient J reaches 1.2, the propulsive efficiencies are all negative for straight-ahead motion and for static azimuthing conditions with 5° and 15° yaw angles. This phenomenon becomes more obvious as the yaw angle increases. When the unit is navigated with a 30°, 45°, or 60° yaw angle, and the trailer advance coefficient J is between 0.5 and 1.2, the efficiency rapidly decreases to a negative value. This can be attributed to the fact that the present propulsive efficiency reflects the relation between the total thrust of the pod unit and the propeller torque; for the same propeller rotation speed the propeller thrust component in the trailer advance direction decreases and the resistance increases with increasing yaw angle so that the effective propeller thrust gradually transfers to a side force direction. In addition, the propeller rotation affects the overall propulsive efficiency for different azimuthing directions. In the present experiment, the right-handed propeller had a more effective right-azimuthing propulsion than the left-handed propellerat low speeds. As the trailer advance speed increased, the propulsive efficiencies in both directions were basically consistent when J is approximately 0.9. In addition, as the trailer advance velocity increased, the overall propulsive efficiency for left-azimuthing conditions became greater than those for right-azimuthing conditions. However, as the propulsive efficiency and total thrust became negative and the torque became much smaller when the advance coefficient J exceeded 1.2, the trends for J=1.3 are not discussed here.

3.3 Analysis of pod unit flow fieldIn the study of podded propulsor hydrodynamics, the interaction between pod propeller and strut is a difficult and important topic because of the complicated flow field between them. This issue is difficult to resolve directly using theoretical approaches, numerical simulations, or traditional experiments.

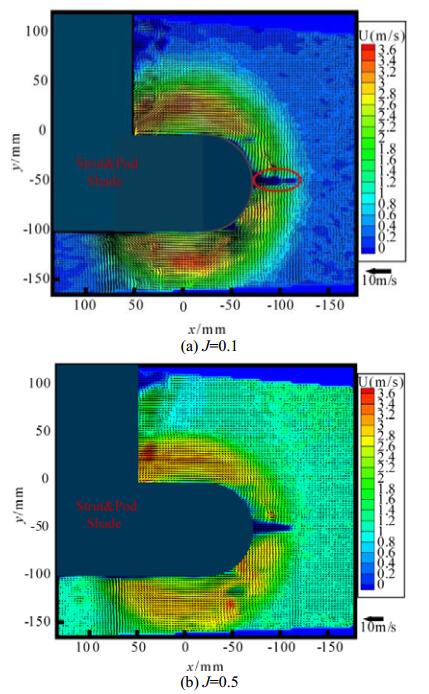

In this study, we use a PIV measurement system to calibrate and analyze the L-type podded propulsor section flow field; the system is positioned between the propeller disk and the oblique strut, 164mm away from the propeller disk, and is operated in straight-ahead motion conditions using three different advance coefficients (J=0.1, 0.5, and 0.9). Figure 9 shows the flow field distribution measured by the PIV system for these three advance coefficient values. Two charge-coupled device (CCD) cameras in the fore and rear were required to use a vehicle-type PIV stereoscopic imaging system. However, some blind areas existed because the camera in the rear was partially blocked by the pod and strut; these blind areas cannot be identified in post processing and the resulting shade is shown in Fig. 9. The blue spot in the red circle in Fig. 9 (a) and subsequent figures is an experimental mark indicating that this area was not subject to flow field measurement. A comparison of the flow field distribution behind the propeller for the three advance coefficients reveals that the flow field velocity in the trailer advance direction first increases and then gradually decreases from inside to outside, because it is affected by the propeller. The maximum velocity occurs at a position approaching the central section, and high-velocity flow fields above and below the pod can be clearly observed. The flow is clearly delaminated at sites with different propeller disk radii and is basically at a consistent level with respect to the trailer advance speed in the area far away from the propeller disk. With increasing trailer advance speed, the external flow field velocity increases, indicating satisfactory accuracy of the flow field measurement. The plane flow velocity shows a similar distribution pattern, and the two-dimensional cross-sectional flow map shows that the water, driven by the propeller rotation, also flows rightward around the pod. The length of the vector represents the velocity magnitude, which is lower away from the pod and higher near the pod.

|

| Figure 9 Flow field behind propeller cross section for various advance coefficients |

In actual ship sailing, orientation control, including turning and azimuthing, is a dynamic operating process, and the hydrodynamic properties of a podded propulsor change continuously during the entire dynamic azimuthing process to achieve a specific yaw angle. The turning direction, and the water disturbance induced by turning, influence the overall force; hence, it is necessary to investigate the unsteady hydrodynamics of a podded propulsor under dynamic azimuthing conditions.

Dynamic force and angle data were collected using a DHDAS_5920 dynamic signal collection and analysis system installed in the towing tank used in this study. The data gathered were non-dimensionalized, filtered, and fitted to obtain curves of the parameters with respect to the angles.

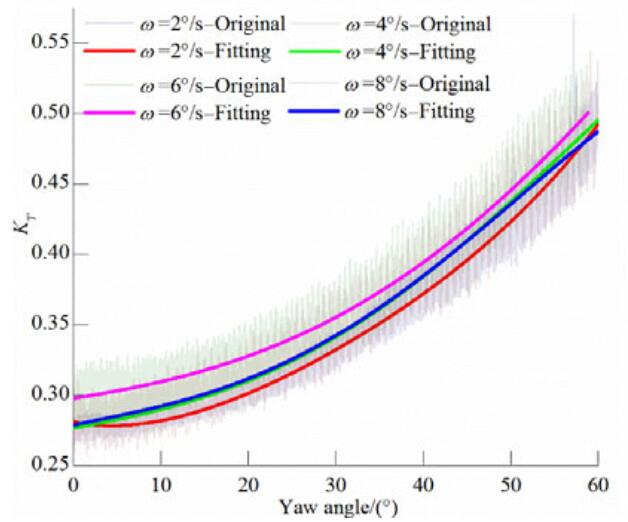

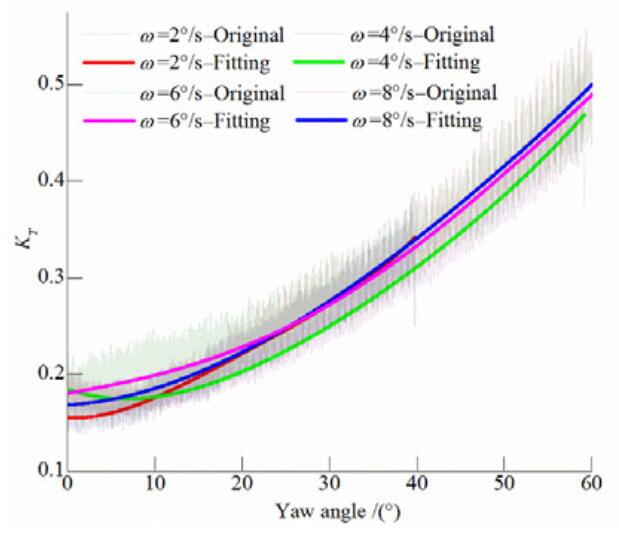

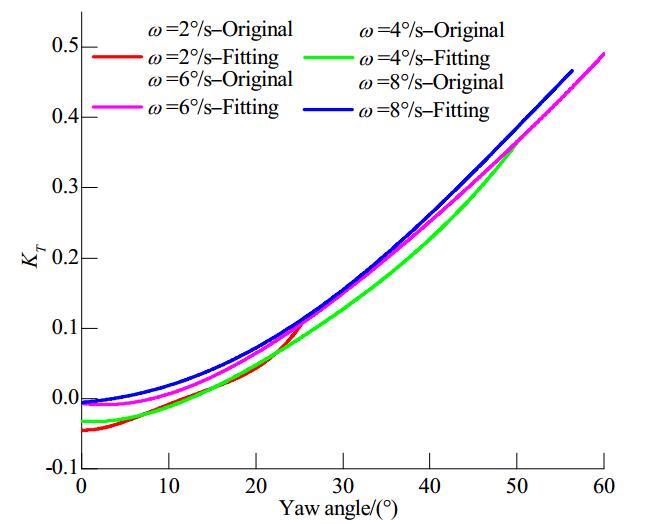

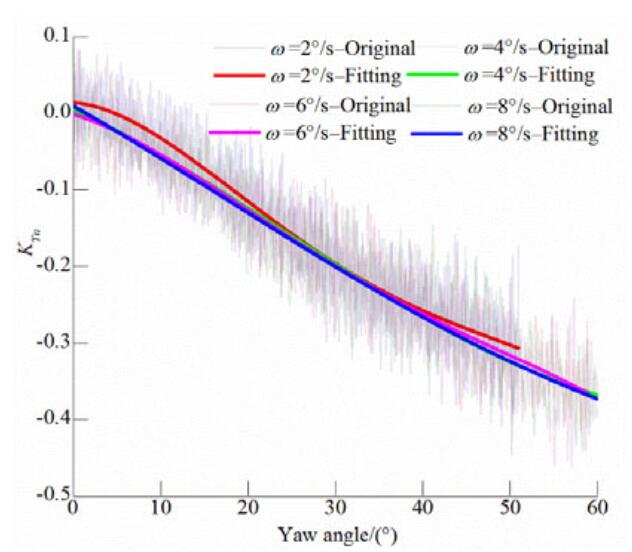

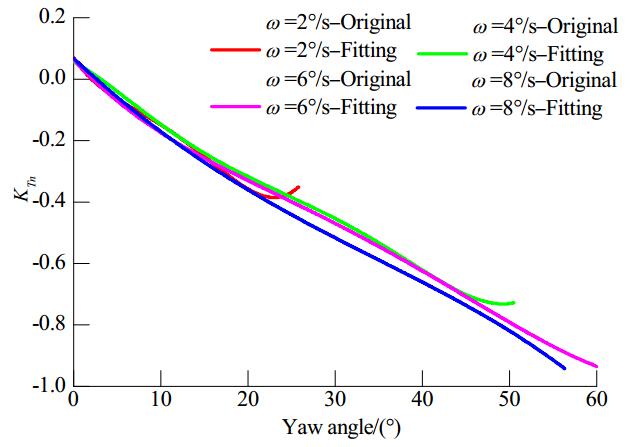

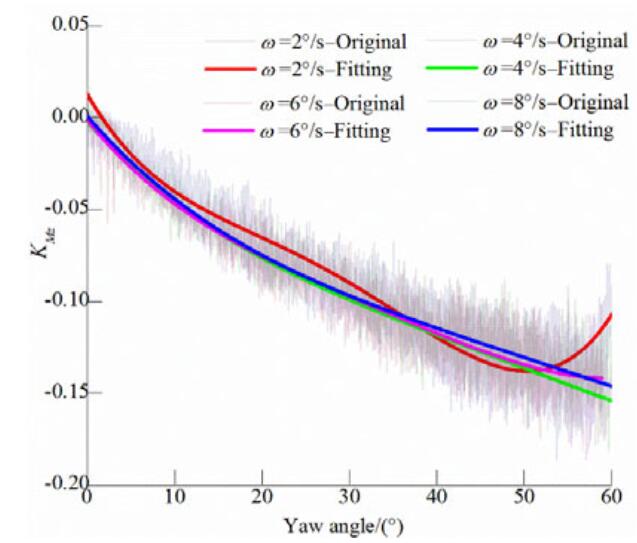

4.1 Hydrodynamic performance of podded propulsor for different azimuthing rates in dynamic azimuthing conditions 4.1.1 Hydrodynamic performance of propellerTo facilitate analysis and comparisons, only data for advance coefficients J=0.6, 0.9, and 1.3 are discussed. Figures 10, 11, and 12 show curves for the propeller thrust coefficient KT versus the yaw angle for various azimuthing rates and advance coefficients. The "Original" curves shown in the figures were generated by filtering the raw data collected using the signal collection and analysis system. To reduce the impact of trailer noise and other signals, a low-pass 50 Hz filter was applied, and a sixth-order nonlinear model was fitted to the data obtained to generate the "Fitting" curves. The data for the overall podded propulsor axial force, tangential force, and steering moment were processed using the same procedures.

|

| Figure 10 ropeller thrust coefficient KT versus yaw angle for various azimuthing rates at J=0.6 |

|

| Figure 11 Propeller thrust coefficient KTversus yaw angle for various azimuthing rates at J=0.9 |

|

| Figure 12 Propeller thrust coefficient KT versus yaw angles for various azimuthing rates at J=1.3 |

As shown in Figures 10-12, the propeller thrust coefficient gradually increases as the dynamic azimuthing angle increases. When J=0.6, as the propeller azimuthing rate increases, the propeller thrust coefficient first increases and then decreases, and the curves coincide at ω=4°/s and ω=8°/s. The thrust coefficient differences between the different dynamic azimuthing rates remain essentially constant as the yaw angle increases, with the exception of when θ=60˚. As the advance coefficient increases to 0.9, the curves for the three different azimuthing rates show smaller discrepancies, except for at ω=4°/s, as shown in Fig. 11. The four curves exhibit greater differences at small yaw angles and gradually approach each other as the yaw angle increases. However, at J=1.3, the thrust at ω=4°/s is still smaller than at other rates. It should be clarified that because of the limitation imposed by the towing tank length, the yaw angles were smaller and the amount of data obtained during the azimuthing process was limited at high trailer advance velocities and low azimuthing rates (ω=2°/s and ω=4°/s). Comparisons of Figs. 10-12 show that for small yaw angles the advance coefficient has a significant effect on the propeller thrust coefficient and that a higher advance coefficient results in a lower thrust. However, the effect of the advance coefficient is weakened and the maximum thrust values have a greater similarity when the yaw angle is greater.

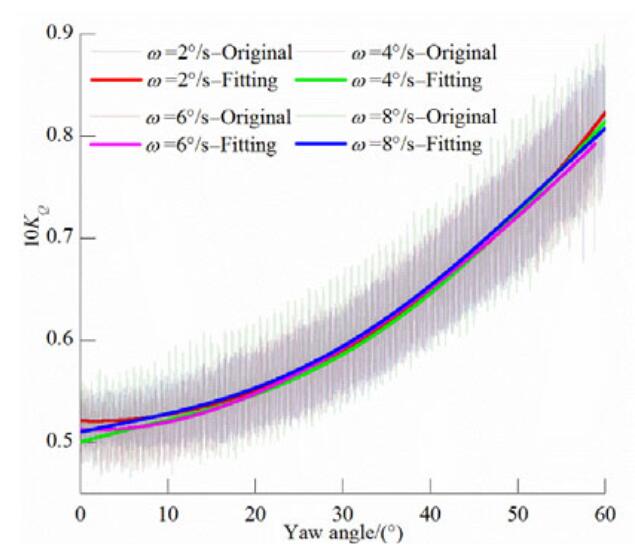

Figures 13-15 show how the propeller torque coefficient changes with respect to the yaw angle at different azimuthing rates for the three advance coefficients considered. The torque coefficient curves resemble the thrust curves, and they coincide for four different azimuthing rates at J=0.6, which indicates that the azimuthing rate has only a small influence on torque variation at this advance coefficient. Similar results are observed at J=0.9. An increase in the advance speed still has a significant effect on the torque at small yaw angles, and the curve shows an increasingly upward trend in torque with increasing yaw angle. However, at low azimuthing rates, the propeller is subjected to large loads. The results are similar for J=1.3 and J=0.9. It is of note here that the torque is higher for ω=2°/s, but because of the limited tank length data could not be arranged for yaw angles greater than 25°; therefore, this needs further investigation in future studies.

|

| Figure 13 Propeller torque coefficient KQ versus yaw angle for various azimuthing rates at J=0.6 |

|

| Figure 11 Propeller torque coefficient KQ versus yaw angle for various azimuthing rates at J=0.9 |

|

| Figure 15 Propeller torque coefficient KQ versus yaw angle for various azimuthing rates at J=1.3 |

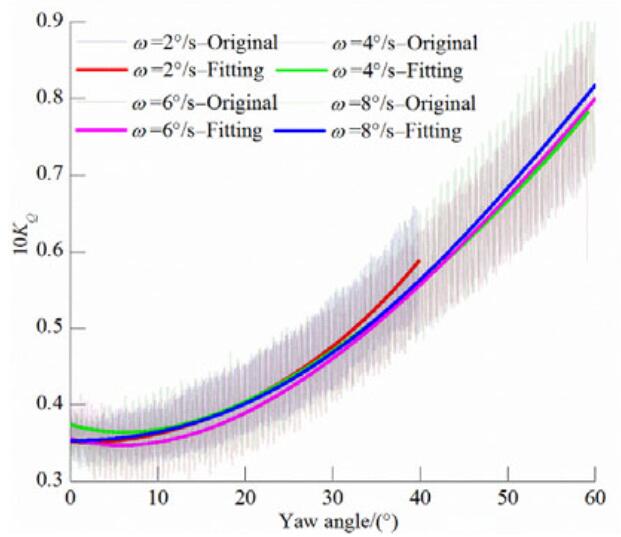

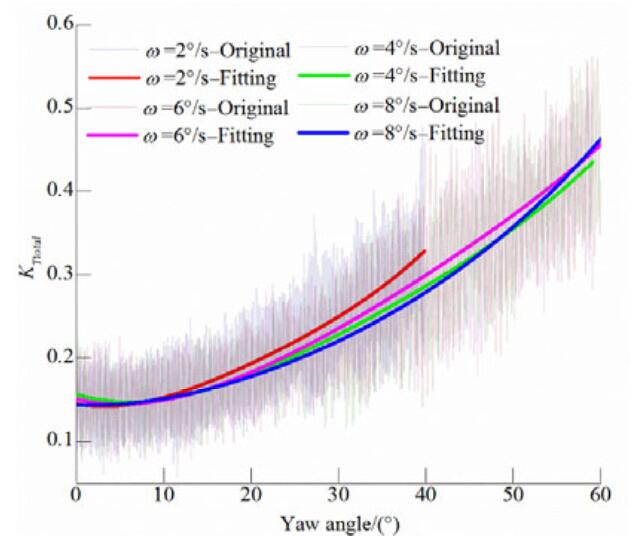

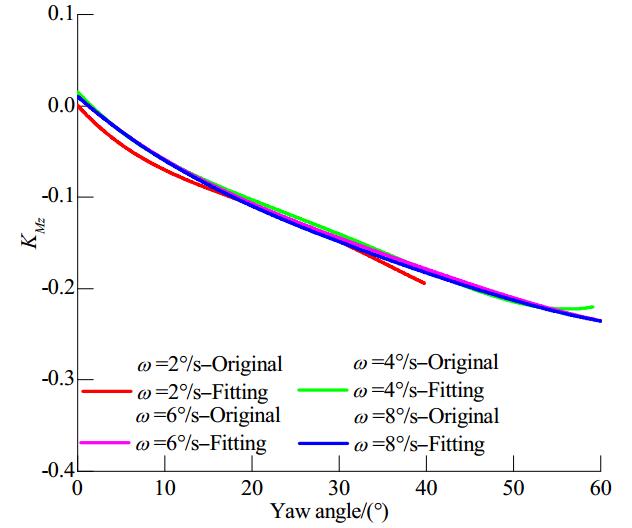

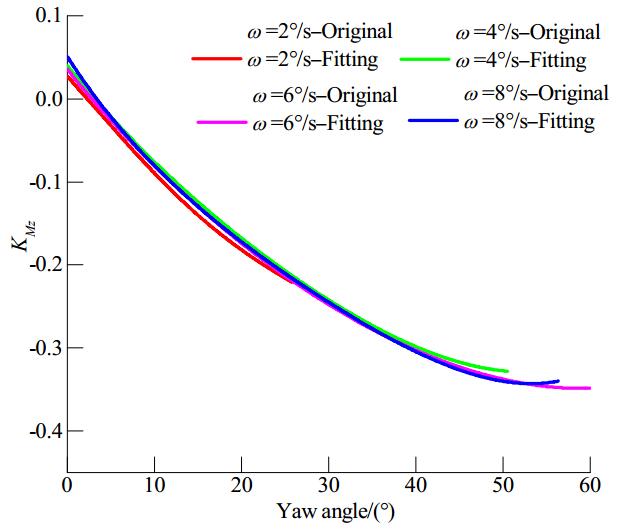

Figures 16-18 show how the L-type pod unit total axial force coefficient varies with the yaw angle for the different J values considered. In contrast to the analysis of the unit thrust coefficient described in Section 3.2, the thrust along the L-type podded propulsor axis was analyzed without converting the coordinate systems. The figures show that at a low advance coefficient the initial value is large, the curves change gradually, and the differences for different azimuthing rates are small, with a relatively similar overall axial thrust. However, as the advance coefficient increases, the differences become more significant. At J=0.9, the axial force coefficient is greater at an azimuthing rate of ω=2°/s and is lower overall at higher azimuthing rates. Therefore, in future research it will be necessary to investigate the performance at low azimuthing rates. At J=1.3, higher azimuthing rates correspond to greater axial forces as the yaw angle increases, which could be attributable to the continuous impact from the prior flow field.

|

| Figure 16 Overall pod unit axial force coefficient versus yaw angle at J=0.6 |

|

| Figure 17 Overall pod unit axial force coefficient versus yaw angle at J=0.9 |

|

| Figure 18 Overall pod unit axial force coefficient versus yaw angle at J=1.3 |

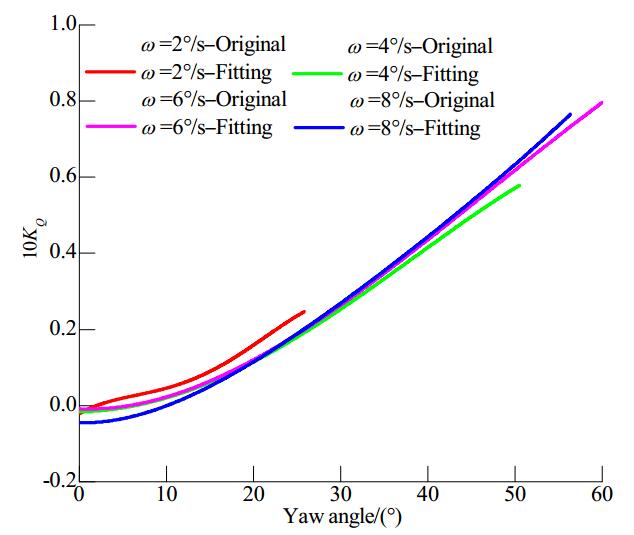

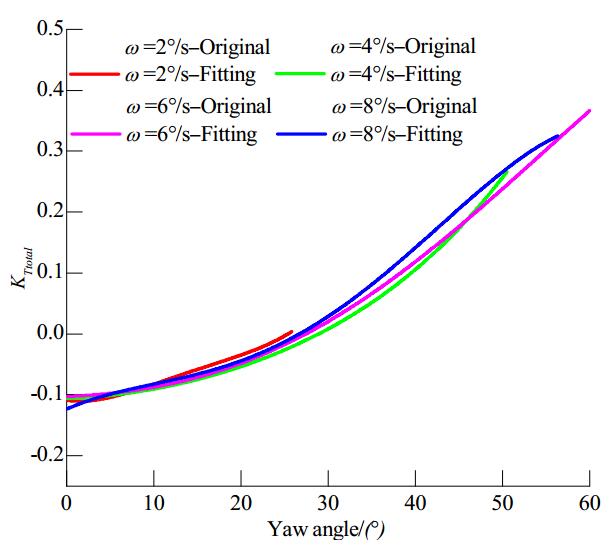

Figures 19-21 show how the overall propulsor normal force coefficient varies with the yaw angle for different J values. In contrast to the overall unit side force analysis described in Section 3.2, for the normal force the original normal thrust along the L-type podded propulsor axis was processed directly, without converting the coordinate systems. The magnitude of the normal force is closely related to the azimuth stability and has a direct effect on the steering moment. The overall normal force exhibits a continuous increasing trend as the advance coefficient increases. As Fig. 19 shows, when J=0.6, the overall unit normal force increases as the dynamic azimuthing rate increases. As the yaw angle increases up to 60°, the normal force at J=1.3 becomes approximately double that at J=0.6.

|

| Figure 19 Overall pod unit normal force coefficient versus yaw angle at J=0.6 |

|

| Figure 20 Overall pod unit normal force coefficient versus yaw angle at J=0.9 |

|

| Figure 21 Overall pod unit normal force coefficient versus yaw angle at J=1.3 |

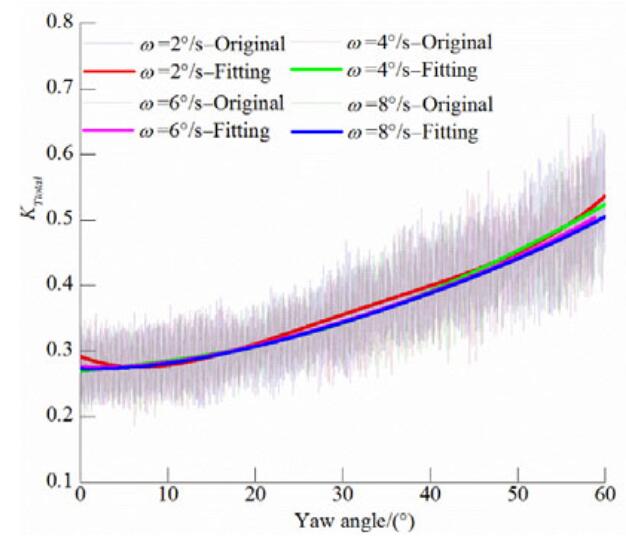

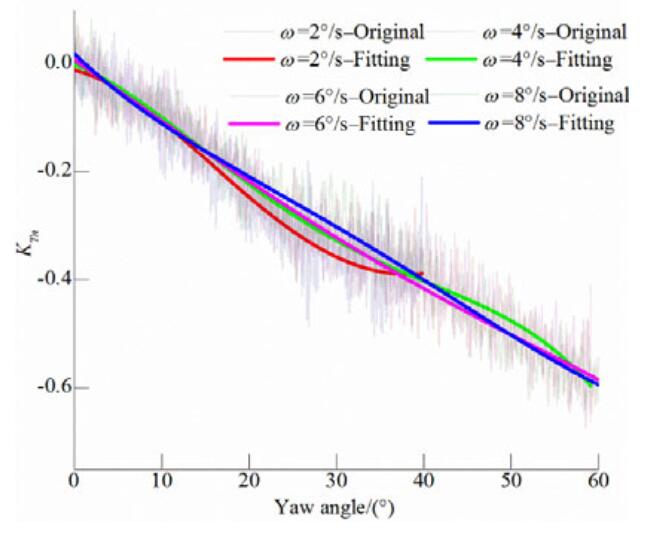

Figures 22-24 illustrate how the overall unit steering moment coefficients varies with the yaw angles in dynamic azimuthing conditions; the overall moment gradually increases as the yaw angle increases, albeit at a decreasing rate. The negative and positive symbols indicate the moment direction. The curves at J=0.6 show violent fluctuations with increasing angle, but the differences in the four curves at J=1.3 are very small and decrease at yaw angles beyond 60°.

|

| Figure 22 Overall pod unit steering moment coefficient versus yaw angle at J=0.6 |

|

| Figure 23 Overall pod unit steering moment coefficient versus yaw angle at J=0.9 |

|

| Figure 24 Overall pod unit steering moment coefficient versus yaw angle at J=1.3 |

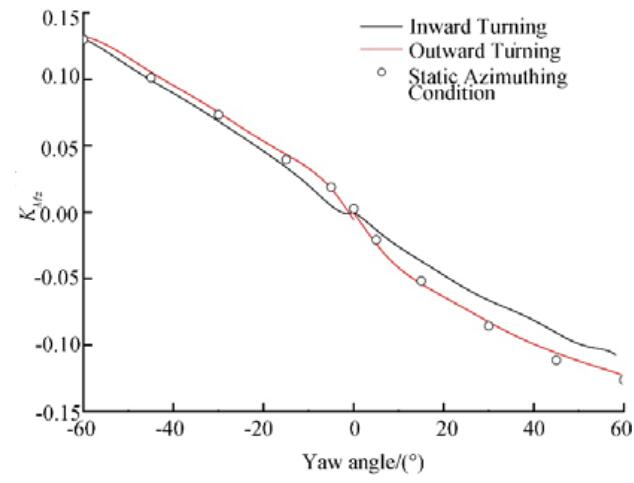

As the interactions between the propeller and water are different for different azimuthing directions, the hydrodynamic performance differs accordingly. For J=0.5 and ω=8°/s, the hydrodynamic performance of the podded propulsor was compared for left-handed versus right-handed azimuths and inward versus outward turnings (definitions of inward and outward are shown in Fig. 1) to evaluate the effect of the azimuthing direction. In the figures below, the curves labeled "Inward Turning" and "Outward Turning" are the fitted curves.

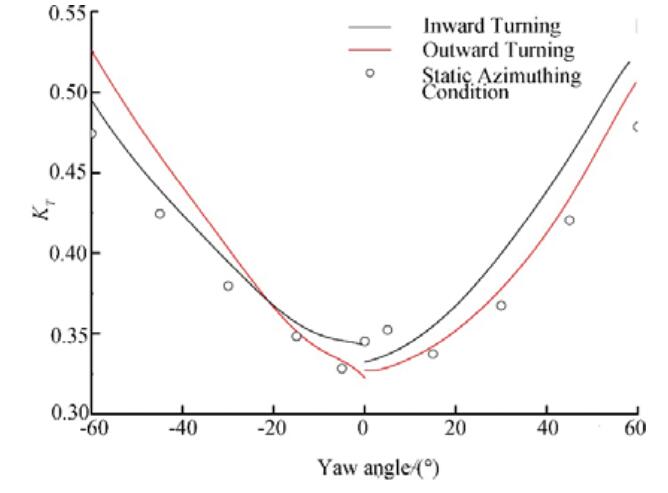

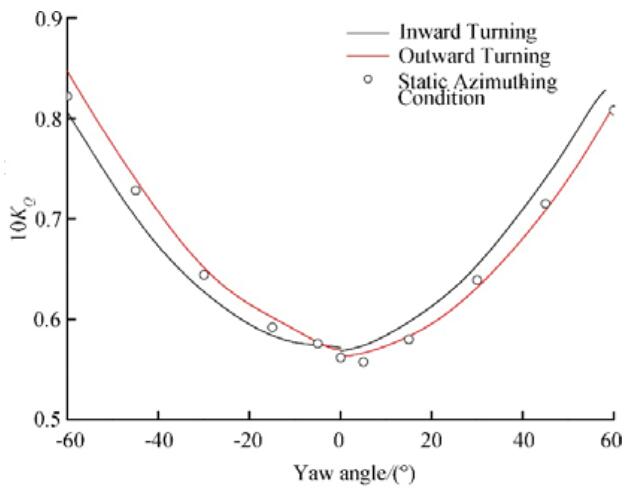

4.2.1 Hydrodynamic performance of propellersFigures 25 and 26 show how the propeller thrust coefficient and torque coefficient vary with the yaw angle for different azimuthing directions. Figure 25 shows that, except for small azimuthing angles, the outward turning thrust is greater than the inward turning thrust during left-handed dynamic azimuthing conditions, in contrast to the situation during right-handed dynamic azimuthing conditions. In static azimuthing conditions, the thrust is smaller than during turning (dynamic azimuthing) when the yaw angle θ > 5°. Figure 26 shows that the error in the propeller torque coefficient for θ=0° for each condition is smaller than that for the thrust coefficient. The torque variation, however, is similar to the thrust variation in dynamic azimuthing conditions. Under left-handed dynamic azimuthing conditions, the outward turning torque is slightly greater than the inward turning torque, while under right-handed dynamic azimuthing conditions the inward turning torque coefficient is larger. Under static azimuthing conditions, the unit torque values for all angles are close to those for outward turning.

|

| Figure 25 Propeller thrust coefficient KT versus yaw angle for various azimuthing angles at J=0.5 |

|

| Figure 26 Propeller torque coefficient KQ versus yaw angle for various azimuthing angles at J=0.5 |

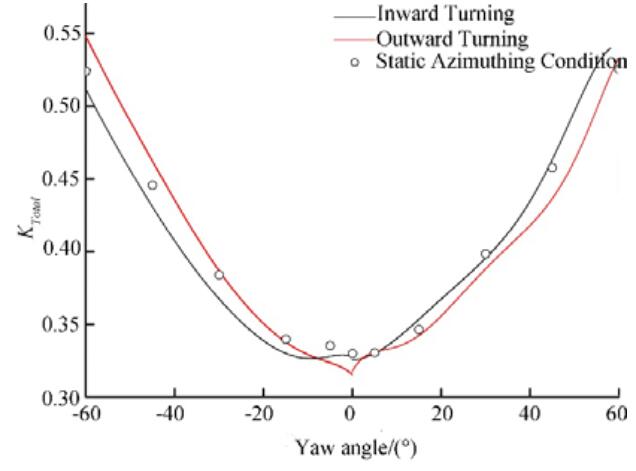

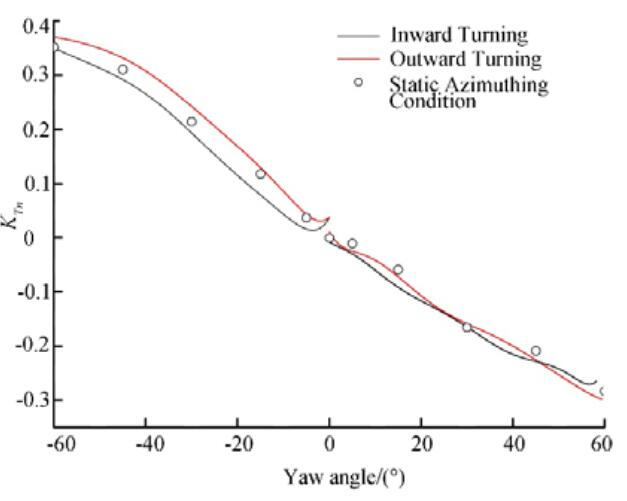

Figures 27-29 illustrate how the total pod unit force varies with the yaw angle for different azimuthing directions. As shown in Fig. 27, the overall podded propulsor axial force is basically consistent with the propeller thrust. Because of the influence of the propeller rotation and pod unit turning, under left-handed dynamic azimuthing conditions the axial force coefficient of the pod unit during outward turning is greater than that during inward turning, whereas, under right-handed dynamic azimuthing conditions the axial force during inward turning is greater. The normal force on the pod unit exhibits a trend similar to that of the steering moment, and it is larger during outward turning under left-handed dynamic azimuthing conditions, whereas it is generally similar during outward and inward turning under right-handed dynamic azimuthing conditions. Regardless of the azimuthing direction, the overall steering moment coefficient is greater during outward turning, and the fitted curve for the outward turnings has a better fit with the data for static azimuthing conditions.

|

| Figure 27 Overall pod unit axial force coefficient versus yaw angle for various azimuthing angles at J=0.5 |

|

| Figure 28 Overall pod unit normal force coefficient versus yaw angle for various azimuthing angles at J=0.5 |

|

| Figure 29 Overall pod unit steering moment coefficient versus yaw angle for various azimuthing angles at J=0.5 |

The hydrodynamic performance of L-type podded propulsors was analyzed using a podded propulsor dynamometer (developed by the authors) and a ship model towing tank; the main conclusions drawn from analysis results are listed below.

Straight-ahead and static azimuthing conditions:

Propeller thrust and torque vary with azimuthing direction. Except at a yaw angle of 5°, both the thrust generated by the propeller and the load on the blades during static azimuthing to the left are generally greater than that during static azimuthing to the right. However, as the yaw angle increases, the thrust of the propeller and load on the blades are reduced in comparison and the situation is even reversed slightly.

At a given advance speed, the overall pod unit thrust decreases as the azimuthing angle increases and even becomes negative. The total thrust of the podded propulsion unit tends to decrease with increasing trailer advance velocity at a given yaw angle. As they are affected by the direction of the propeller rotation, the interactions of the induced wake field with the unit strut and pod differ for leftward versus rightward azimuthing conditions, and as a result the total thrust curve is not centrally symmetric but rather slants to the right and peaks at a yaw angle of approximately −5°.

The overall side force and steering moment on the podded propulsive unit exhibit similar trends. As the trailer advance coefficient and unit yaw angle increase, the overall side force increases, and the influence of the advance coefficient increases when the yaw angle exceeds 15°. As with the overall unit thrust, the side force and steering moment do not reach zero at ω=0° but rather at approximately ω=2°.

Within the yaw angle range of ω≤15°, the propulsive efficiency initially increases and then decreases as the advance coefficient increases. However, as the yaw angle increases the efficiency increases more slowly and eventually decreases. In addition, because of the effect of the propeller rotation direction, the overall propulsive efficiencies at low advance speeds under right-handed azimuthing conditions are more effective than under left-handed azimuthing conditions. As the trailer advance speed increases, the propulsive efficiencies remain basically the same for the two directions when J is approximately 0.9. When the trailer advance velocity reaches a certain level, the overall propulsive efficiency under left-handed azimuthing conditions exceeds that under right-handed azimuthing conditions, and this phenomenon becomes more pronounced as the yaw angle increases.

Dynamic azimuthing conditions:

The performance of podded propulsors were investigated at azimuthing rates of ω=2°/s, 4°/s, 6°/s, and 8°/s for two dynamic azimuthing directions (left-handed and right-handed) and for two turning directions (outward turning and inward turning). At different azimuthing rates, the trends in the performance curves were similar, but values obtained for the performance measures were different. Under dynamic azimuthing conditions, the thrust and load during outward turning were greater than those during inward turning for left-handed azimuthing, and the opposite was true for right-handed azimuthing. In addition, the trends for the pod unit force were similar. The azimuthing rate, yaw angle, and turning direction were all found to affect the L-type propulsor force to a certain degree, but the overall effect was not noticeable.

Acknowledgement:This project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 41176074, 51379043 and 51409063) and was conducted in response to the great support received from a basic research project entitled "Multihull Ship Technology Key Laboratory of Fundamental Science for National Defence", which was conducted at Harbin Engineering University. The authors would like to extend their sincere gratitude to their colleagues in the towing tank laboratory.

| Cheng BH, Dean JS, Miller RW, Cave WL, 1989. Hydrodynamic evaluation of hull forms with pod propulsors. Naval Engineering Journal, 101, 197–206. DOI:10.1111/j.1559-3584.1989.tb02199.x |

| Chicherin IA, Lobatchev MP, Pustoshny AV, Sanchez CA, 2004. On a propulsion prediction procedure for ships with podded propulsors using RANS-code analysis. 1st International Conference on Technological Advances in Podded Propulsion, Newcastle University, UK, 223-236. |

| Han JM, Paik KJ, Choi SH, Song IH, Shin SC, 2000. Prediction of steady performance of podded propellers. Koje, Korea: Proceedings of Annual Spring Meeting of SNAK144-147. |

| He W, Chen KQ, Li ZR, 2015. Experimental research on hydrodynamics of tandem type podded propulsors in azimuthing conditions. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology Sci. Tech. (Nat. Sci. Ed. ), 43, 01, 107-111. DOI: 10.13245/j.hust.150122 |

| Islam MF, Akinturk A, Veitch B, Liu P, 2009. Performance characteristics of static and dynamic azimuthing podded propulsor. 1st International Symposium on Marine Propulsors, 482–492. |

| Islam M.F, Veitch B, Liu PF, 2007. Experimental Research on Marine Podded Propulsors. Journal of Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering, 4(2), 57–71. DOI:10.3329/jname.v4i2.989 |

| ITTC-Recommended Procedures, 2002. Propulsion Performance-Podded Propeller Tests and Extrapolation 7. 5-02-03-01. 3, Revision 00. |

| Kawakita C, Hoshino T, Minamiura J, 1994. Prediction of hydrodynamic performance of hydrofoil, strut and pod configuration by a surface panel method. The Japan Society of Naval Architects and Ocean Engineer, 87, 15–25. |

| Ohashi K, Hino T, 2004. Numerical simulations of flows around a ship with podded propulsor. 1st International Conference on Technological Advances in Podded Propulsion, Newcastle University, UK, 211-221. |

| Palm M, Jurgens D, Bendl D, 2011. Boundary layer control of twin skeg hull form with reaction podded propulsion. 2nd International Symposium on Marine Propulsors, Hamburg, Germany. |

| Reichel M, 2007. Manoeuvring forces on azimuthing podded propulsor model. Polish Maritime Research, 14, 3–8. DOI:10.2478/v10012-007-0006-0 |

| Sasaki N, 2008. The specialist committee on azimuthing podded propulsion-report and recommendations. Presentation at the 25th ITTC, Fukuoka, Japan, Sept. |

| Shi YM, Zhang WB, Chen G, 2010. Hydrodynamic performance study of POD on single screw commercial vessel. Shipbuilding of China, 51, 36–44. |

| Szantyr JA, 2001. A surface panel method for hydrodynamic analysis of pod propulsors. Faculty of Ocean Engineering and Ship Technology, 12, 209–228. |