2. Building, Civil & Environmental Engineering Department, Concordia University, Montreal H3G 1M8, Canada

1 Introduction

Cavitation is mainly known for its violent behavior, which is common in turbo-machinery vehicles. It is a part of the flow around an immersed body, and thus, it can move rapidly from low-pressure to high-pressure regions. As a result, a very rapid collapse occurs, giving rise to a shock wave (Brennen, 1995; Franc and Michel, 2004). The main cavitation's adverse effects are vibrations, erosions, noise, and efficiency reduction over a wide range of frequencies (Kubota et al., 1992; Alajbegovic et al., 1999). An investigation of these problems and attempts to reduce these effects are common study problems among researchers and designers of turbo-machinery.

Cavitation is an unsteady, multiphase turbulent flow phenomenon with two-phase mixtures of vapor and liquid. Numerical simulation is an acceptable method of studying the cavitation flow. As mentioned above, cavitation is a turbulent phenomenon; thus, many researchers have added some turbulence models to improve the accuracy of the numerical results (Wu et al., 2003; Johansen et al., 2004; Coutier-Delgosha et al., 2007; Kim, 2009; Li et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2009; Seo and Lele, 2009; Lu et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2011; Mostafa et al., 2012; Ji et al., 2015). For example, Wu et al. (2003) used k-ε turbulence model and added a filter to the solver to simulate the cavitation around a hydrofoil. They used the filter to avoid excessive dissipation in small-scale motions without any unwanted effect on the main features of the flow.

Recent studies show that for accurate simulation of unsteady cavitating flows, especially in cavitation regions, the turbulent eddy viscosity must be corrected. Zhou and Wang (2008) simulated two-dimensional cavitating flow around a hydrofoil, NACA66, by using k-ε RNG turbulence model considering non-condensable gas mass fraction. They showed that standard k-ε RNG cannot accurately simulate the unstable cavity shedding, especially at lower cavitation numbers. Thus, they used a modified k-ε RNG solver by changing the definition of turbulent viscosity to improve the accuracy. Huang et al. (2013) introduced a filter-based density corrected model to regulate the turbulent eddy viscosity in both cavitation regions on the foil and in the wake. They showed that, for the unsteady sheet/cloud cavitating case, the formation, breakup, shedding, and collapse of the sheet/cloud cavity increase the turbulent velocity fluctuations in the cavitating region around the foil and in the wake.

Coutier-Delgosha et al.(2003, 2007) used an implicit finite volume scheme (based on the SIMPLE algorithm) to solve Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes equations associated with a barotropic vapor/liquid state law. To simulate turbulence effects on cavitating flows, four different models were implemented (standard k-ε RNG; modified k-ε RNG; k-ω with and without compressibility effects). They found that the results of the modified k-ε RNG model by reducing the mixture turbulent viscosity is in good agreement with experimental ones.

Dular et al. (2005) evaluated the capabilities of a commercial CFD code (FLUENT) for the simulation of a developed cavitating flow. They used an implicit finite volume scheme based on the SIMPLE algorithm associated with multiphase and cavitation model. Reboud et al. (1998) proposed a k-ε RNG turbulence model equipped with a modification of the turbulent viscosity. They found that the modified k-ε RNG model can predict essential features, such as the development of re-entrant jets, the shedding of vortex, and cloud cavities. According to previous works, k-ε RNG algorithm is a reliable turbulence model for the cavitation phenomenon.

An in-depth investigation indicates that most previous works focused on resolving cavitation and understanding its physics and behavior. However, very little research has been performed on reducing the effects of cavitation or controlling this phenomenon.

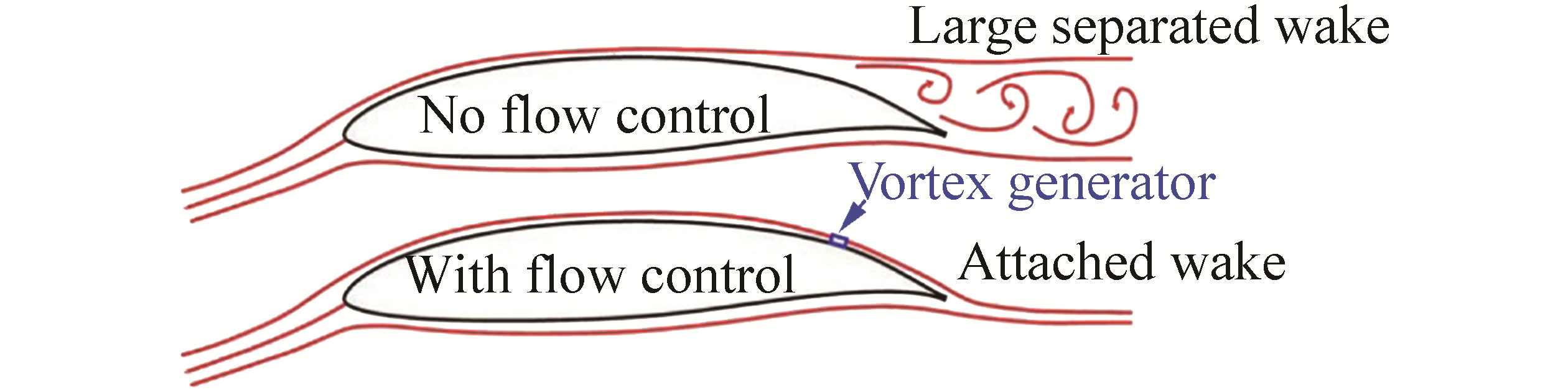

In this paper, we will investigate how the cavitation phenomena around the hydrofoil can be controlled. For this purpose, we introduce a new idea to stabilize the cavitation bubble by aborting the cyclic process of growth and implosion of the cavitation. This goal is achievable through artificial cavitation bubble generators (ACGs), which are introduced in this work. The idea originated from vortex generators, which are commonly used in boundary layer control around airfoils, as demonstrated in Fig. 1 (Kerho and Kramer, 2003). This analogy is used to control boundary layer thickness and therefore control the upper surface pressure distribution and remove cavitation or at least reduce the bubble size and stabilize it.

|

| Figure 1 Schematic showing the effect of vortex generators on the boundary layer around airfoils (Kerho et al., 2003) |

Two-phase cavitating flow models based on the homogeneous mixture approach have been included in expert commercial codes such as FLUENT ( ANSYS Fluent Theory Guide and User's Guide, 2013). Therefore, we used this package in our simulation. We first evaluate this model for the benchmark problem of a 2D hydrofoil and compare the numerical results with experimental and numerical data of Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007). Then, we investigate the effects of ACG on the cavitating flow over the hydrofoil.

2 Numerical simulationThis section describes the governing equation, numerical method, and physical domain used in our simulation.

2.1 Numerical approachTo simulate the cavitating flow, the numerical code FLUENT was used. For the simulation, we considered the SIMPLE scheme for pressure-velocity coupling, second-order upwind discretization for the momentum equations, and first-order upwind discretization for other scalar transport equations. The flow close to the body surface is of particular importance in the current study. The mesh structure in the computational domain addresses this concern by heavily clustering the mesh close to the solid surface of the body.

2.2 Turbulence modelFor turbulence modeling, we applied the k-ε RNG model. The standard k-ε RNG model is unable to correctly simulate the cyclic behavior of the cloud cavitation, the cavity length, and the re-entrant jet because of over prediction of the turbulent viscosity in the rear part of cavity. Therefore, we used the modified k-ε RNG model, which was successfully applied by Reboud et al. (1998) and Dular et al. (2005). In this model, the mixture turbulent viscosity is artificially reduced in the low void ratio areas

| $ {{\mu }_{t}}=f\left(\rho \right){{C}_{\mu }}\frac{{{k}^{2}}}{\varepsilon } $ | (1) |

where

| $ f\left(\rho \right)={{\rho }_{\nu }}+\frac{{{\left({{\rho }_{m}}-{{\rho }_{\nu }} \right)}^{n}}}{{{\left({{\rho }_{l}}-{{\rho }_{\nu }} \right)}^{n-1}}}\, \, \, \, \, \, \, \, \, \, n\gg 1 $ | (2) |

where

The mixture model is used in this work for the numerical simulation of cavitating flows (ANSYS Fluent Theory Guide and User's Guide, 2013). In this model, the flow is assumed to be in thermal equilibrium at the interface where the flow velocity is assumed to be continuous. The following conservation laws of continuity and momentum along with volume fraction equation have been solved simultaneously to simulate the problem.

| $ \frac{\partial }{\partial t}\left({{\rho }_{m}} \right)+\nabla \cdot \left({{\rho }_{m}}{{\boldsymbol{v}}_{m}} \right)=0 $ | (3) |

where vm is the mass-averaged velocity

| $ {{\boldsymbol{v}}_{m}}=\frac{\sum\limits_{k=1}^{n}{{{\alpha }_{k}}{{\rho }_{k}}{{\boldsymbol{v}}_{k}}}}{{{\rho }_{m}}} $ | (4) |

where

| $ {{\rho }_{m}}=\sum\limits_{k=1}^{n}{{{\alpha }_{k}}{{\rho }_{k}}} $ | (5) |

where

| $ \begin{align} &\frac{\partial }{\partial t}\left({{\rho }_{m}}{{\boldsymbol{v}}_{m}} \right)+\nabla \cdot \left({{\rho }_{m}}{{\boldsymbol{v}}_{m}}{{\boldsymbol{v}}_{m}} \right)= \\ &-\nabla p+\nabla \cdot \left[ {{\mu }_{m}}\left(\nabla {{\boldsymbol{v}}_{m}}+\nabla \boldsymbol{v}_{m}^{\text{T}} \right) \right]\, +{{\rho }_{m}}\boldsymbol{g}+\boldsymbol{F}+\nabla \cdot \left(\sum\limits_{k=1}^{n}{{{\alpha }_{k}}{{\rho }_{k}}{{\boldsymbol{v}}_{dr, k}}{{\boldsymbol{v}}_{dr, k}}} \right) \\ \end{align} $ | (6) |

where n is the number of phases and also p, μm, g, and F are pressure, mixture viscosity, gravity, and body forces, respectively. Note that μm is

| $ {{\mu }_{m}}=\sum\limits_{k=1}^{n}{{{\alpha }_{k}}\mu } $ | (7) |

vdr, k is the drift velocity for secondary phase k

| $ {{\boldsymbol{v}}_{dr, k}}={{\boldsymbol{v}}_{k}}-{{\boldsymbol{v}}_{m}} $ | (8) |

From the continuity equation for secondary phase k, the volume fraction equation can be obtained

| $ \frac{\partial }{\partial t}\left({{\alpha }_{k}}{{\rho }_{k}} \right)+\nabla \cdot \left({{\alpha }_{k}}{{\rho }_{k}}{{\boldsymbol{v}}_{m}} \right)=-\nabla \cdot \left[ {{\alpha }_{k}}{{\rho }_{k}}{{\boldsymbol{v}}_{dr, k}} \right]+\sum\limits_{q=1}^{n}{\left({{{\dot{m}}}_{qk}}-{{{\dot{m}}}_{kq}} \right)} $ | (9) |

where

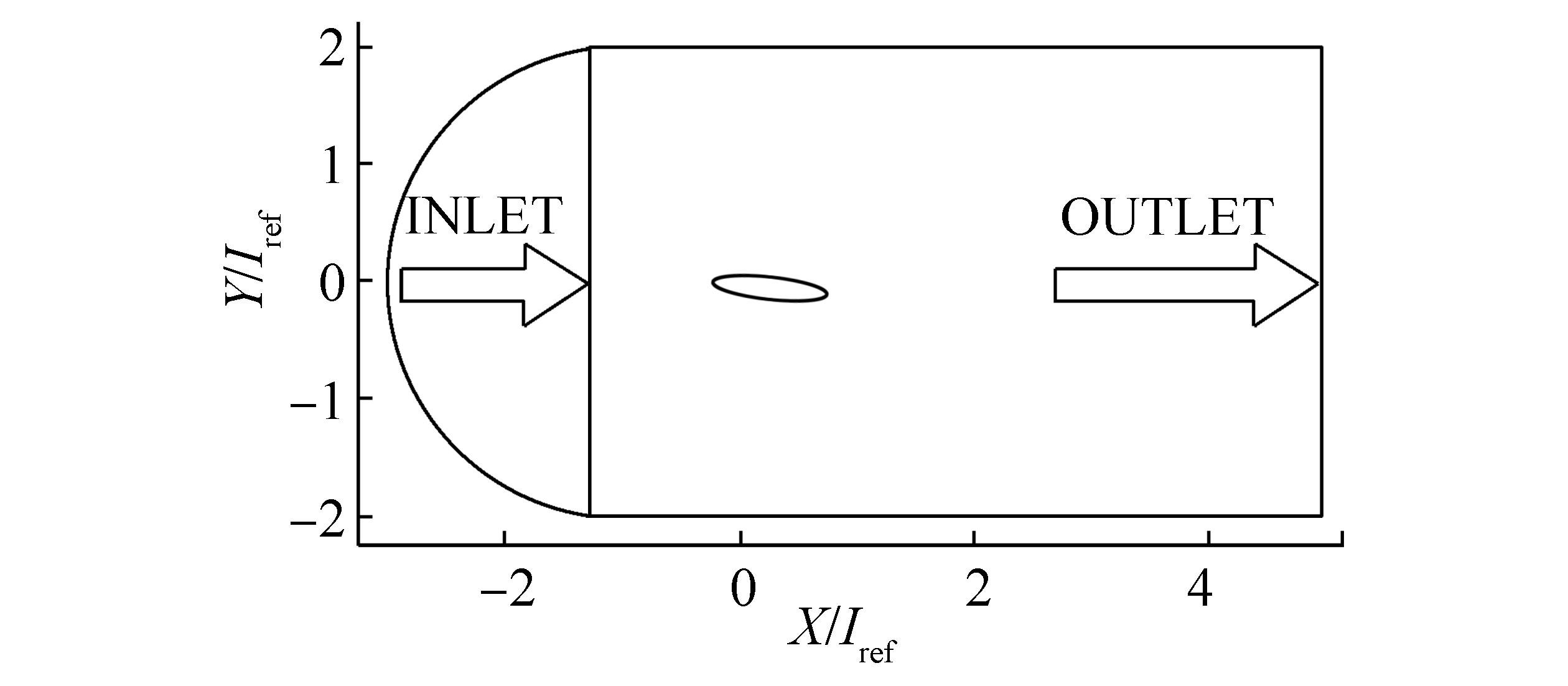

The flow field around the hydrofoil, CAV2003, is modeled in two dimensions. The schematic view of the hydrofoil geometry and the computational domain is presented in Fig. 2. The hydrofoil's chord is

|

| Figure 2 Schematic diagram of the hydrofoil, computational domain, and boundary conditions |

| $ \begin{align} &\frac{y}{c}=0.11858{{\left(\frac{x}{c} \right)}^{0.5}}-0.02972\left(\frac{x}{c} \right)+ \\ &0.00593{{\left(\frac{x}{c} \right)}^{2.0}}-0.07272{{\left(\frac{x}{c} \right)}^{3.0}}-0.02207{{\left(\frac{x}{c} \right)}^{4.0}} \\ \end{align} $ | (10) |

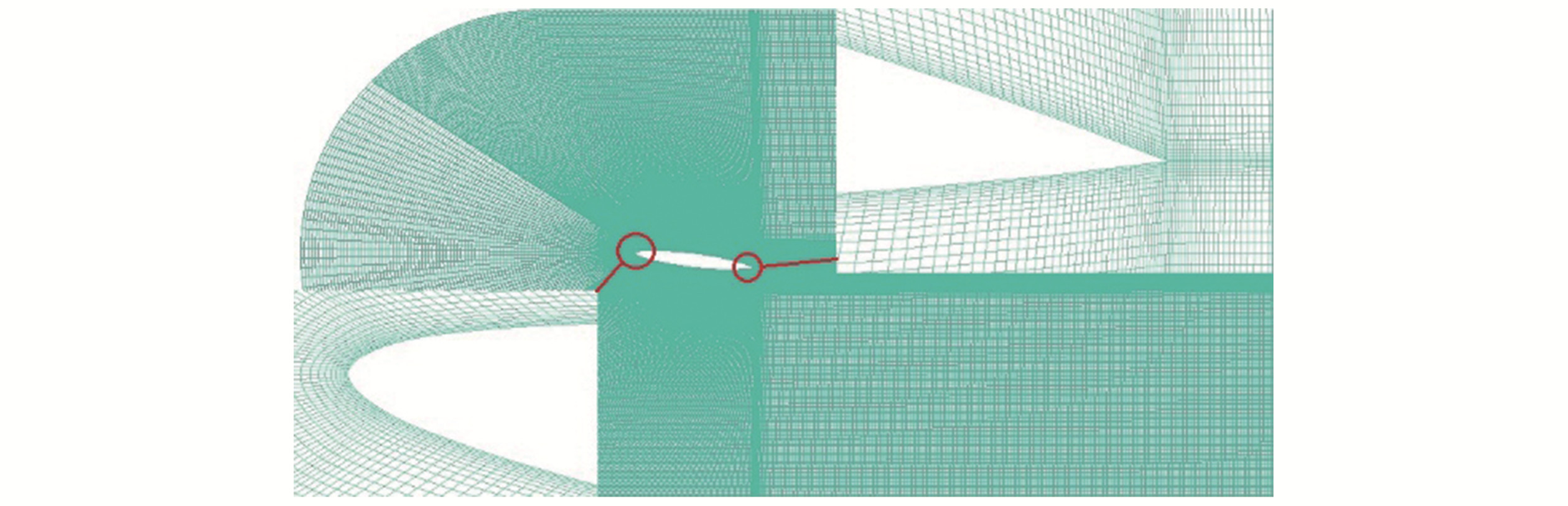

A C-type orthogonal mesh was generated around the hydrofoil as shown in Fig. 3. The near-wall mesh was carefully selected to resolve the viscous sublayer

|

| Figure 3 Computational mesh around the foil |

The boundary conditions of the simulation are shown in Fig. 2. The velocity is imposed at the inlet, and the pressure is fixed at the domain's outlet. The initial values and reference parameters through this work are set as shown in Table 1.

| Angleof attack 7° | lref=0.1m | |

| Vref=6.0 m/s | Pvapor=2000Pa | |

| ρref=998.0 kg/m3 | Treflref/ref=0.0167s |

The results of the proposed idea are presented in this section. The numerical simulation is validated and verified based on available experimental and numerical data. To avoid stability and accuracy issues, the time step value is 0.001 for all cases.

3.1 ValidationAccording to the analysis conducted by Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007), four main structures related to different cavitation parameter can be seen for the 7° angle of attack. No cavitation exists around the hydrofoil for

| $ \sigma =\frac{{{P}_{r}}-{{P}_{v}}}{0.5\rho {{V}^{2}}} $ | (11) |

where Pr and Pv are reference pressure and vapor pressure of the fluid (Pascal), respectively.

As mentioned above, we expect to observe a steady-state flow with no cavitation around the hydrofoil in this test case. Fig. 4 shows the pressure domain around the hydrofoil simulated by the current work and compares it with that by Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007). We can observe a local low-pressure area around the suction side of the hydrofoil.

|

| Figure 4 Pressure contours around the hydrofoil calculated by current work (top picture) and Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007) (bottom picture), α=7°, σ=4 |

Fig. 5 shows a comparison between the velocity of the flow around the hydrofoil calculated by our algorithm and Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007). The lift coefficient values are illustrated in Table 2. The results demonstrate the current algorithm has good agreement with that proposed by Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007).

|

| Figure 5 Velocity contours around the hydrofoil for the current work (top), numerical simulation of Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007) (middle), experimental simulation of Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007) (bottom), α=7°, σ=4 |

| Present simulation | 0.66 |

| Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007)-numerical | 0.66 |

| Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007)-experimental | 0.65 |

The next section for the validation is cloud cavitation simulation. As mentioned before, when the cavitation number is

|

| Figure 6 Complete cycle for the growth and collapse of the cavitation for the present work (top) and Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007) (bottom), α=7°, vref=6 m/s, and σ=0.9, time step between pictures is 14 ms |

Fig. 7 shows the lift, drag, and pressure coefficients on the suction surface of the hydrofoil at x/lref=0.5 calculated by the present work and compares it with those obtained by Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007). Clearly, the present work achieves good accuracy for the cyclic behavior of the cavitation.

|

| Figure 7 Comparison between lift, drag, and pressure coefficients for the present work and Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007) |

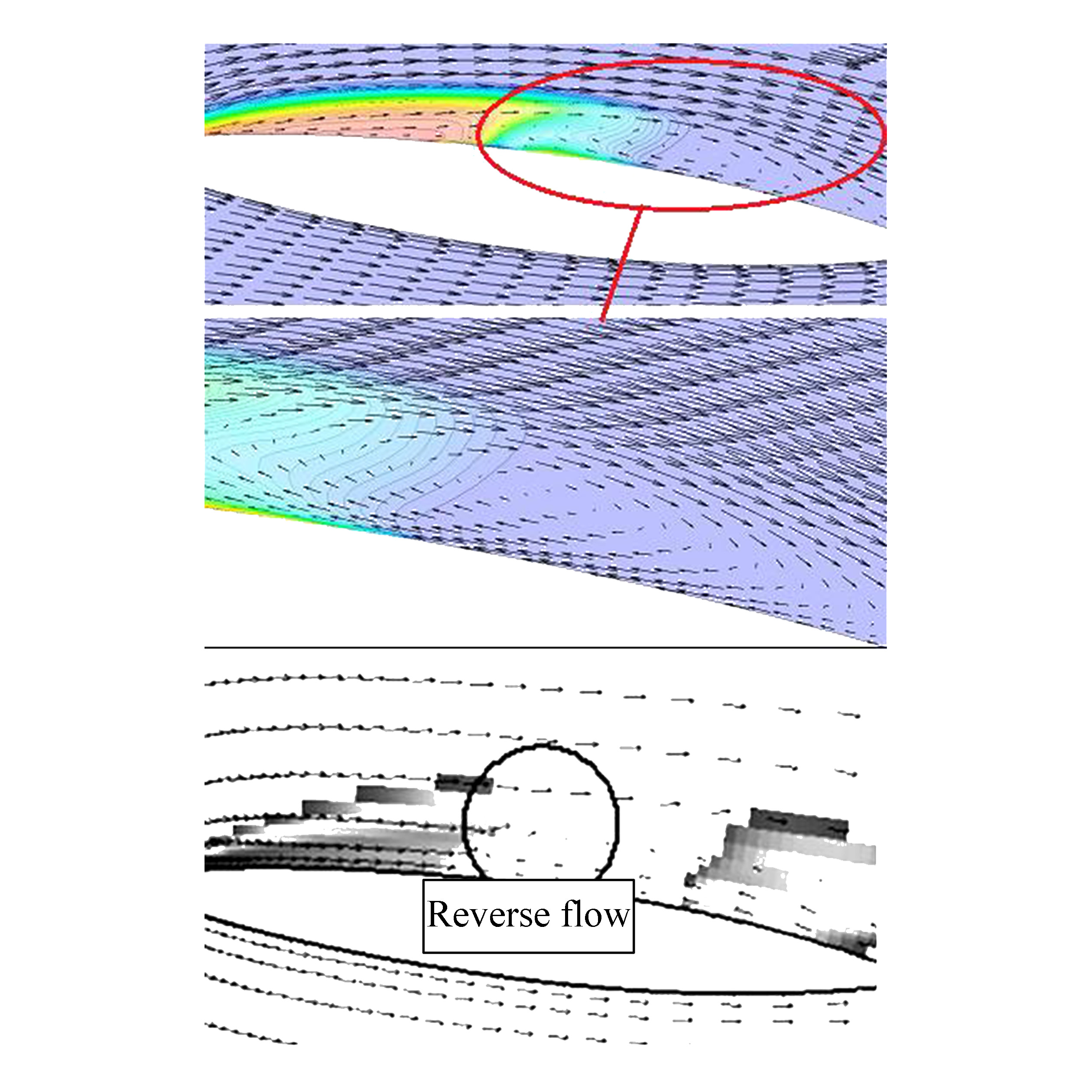

Re-entrant jet is the main cause of the unsteady and cyclic behavior of the cavitation. This phenomenon is a liquid stream that penetrates under the cavitation, like a reverse flow, and detaches it from the surface of the hydrofoil, after which break-off will occur (Delgosha et al., 2007). Fig. 8 shows the re-entrant jet in our simulation that is similar to the corresponding result obtained by Delgosha et al. (2007).

|

| Figure 8 Reverse flow generation due to the re-entrant jet for the present simulation (top) and Coutier-Delgosha et al. (2007) (bottom) |

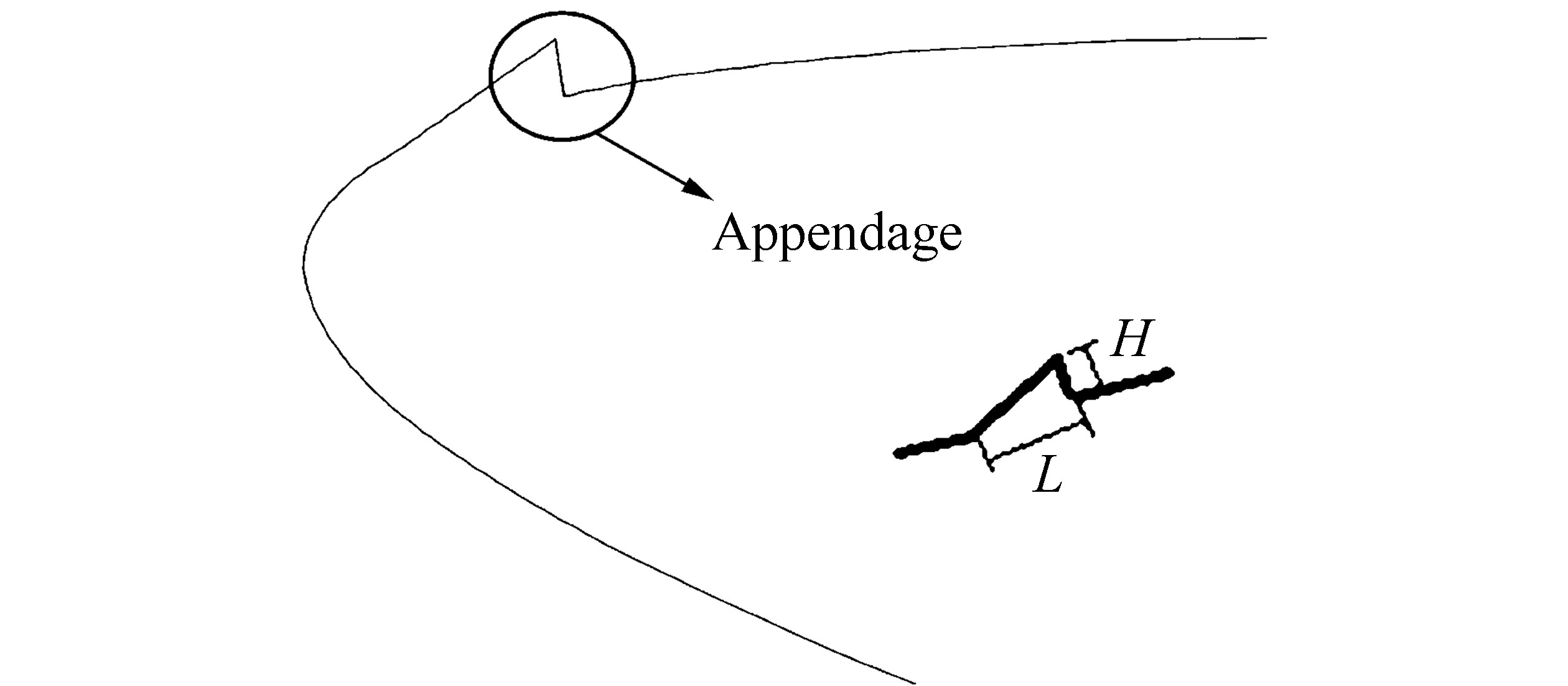

As mentioned before, the main undesirable effect of cavitation phenomenon is its cyclic behavior. For this reason, the main purpose of this paper is to introduce a way to control this cyclic behavior. To this end, the idea is to create a condition in which the local static pressure of a moving liquid is always below the saturated vapor pressure in a place where the possibility of cavitation formation exists. If we control the flow and create this condition, then a bubble of cavitation is created, which, unlike in the normal condition, never disappears. In other words, we produce an artificial cavitating bubble that is stable and does not vanish over time. This artificial cavitating bubble can affect the entire processes of vaporization, bubble generation, and bubble implosion, which occur under a normal condition without any control. To produce the artificial cavitating bubble, a local static pressure needs to be created below the saturated vapor pressure. This goal can be achieved by inserting a small appendage called ACG on the upper surface of the hydrofoil where the cavitating bubble is expected to be produced (see Fig. 9). The schematic of the hydrofoil with the inserted appendage near the leading edge (the place where the cavitation bubble is expected to form) is shown in Fig. 9. L and H are the dimensionless length and height, H/chord and L/Chord, of the appendage, respectively. Our investigations on the size of the appendage show that it should be small enough so that it does not have a significant effect on the hydrodynamics performance of the hydrofoil. As will be shown later, the selection of the shape, size, and location of the appendage is critical to avoid negative side effects. L and H were selected based on numerous test cases. The optimum size of these two variables was determined after numerous simulations.

|

| Figure 9 Schematic diagram of the appendage located on the hydrofoil |

|

| Figure 10 (a) Recirculation velocity vectors behind the ACG (b) pressure coefficient on the foil with ACG |

| $ \begin{align} &L=8.3\times {{10}^{-3}} \\ &H=3.67\times {{10}^{-3}} \\ \end{align} $ |

Results of the flow simulation over the hydrofoil equipped with a proper ACG are presented below. Boundary conditions and flow parameters are the same as in Section 2.3, and the cavitation number is set to 0.8. To reduce the volume of content, we presented only two test cases here. As shown in Fig. 10(a), a recirculating region is present behind this ACG. At the core of this recirculation region, the local static pressure is lower than in the other places [e.g., see Fig. 10(b)]. When the ACG is properly designed and located in an appropriate position, behind the ACG, a situation is created where the local static pressure is subjected below the saturated vapor pressure at all times.

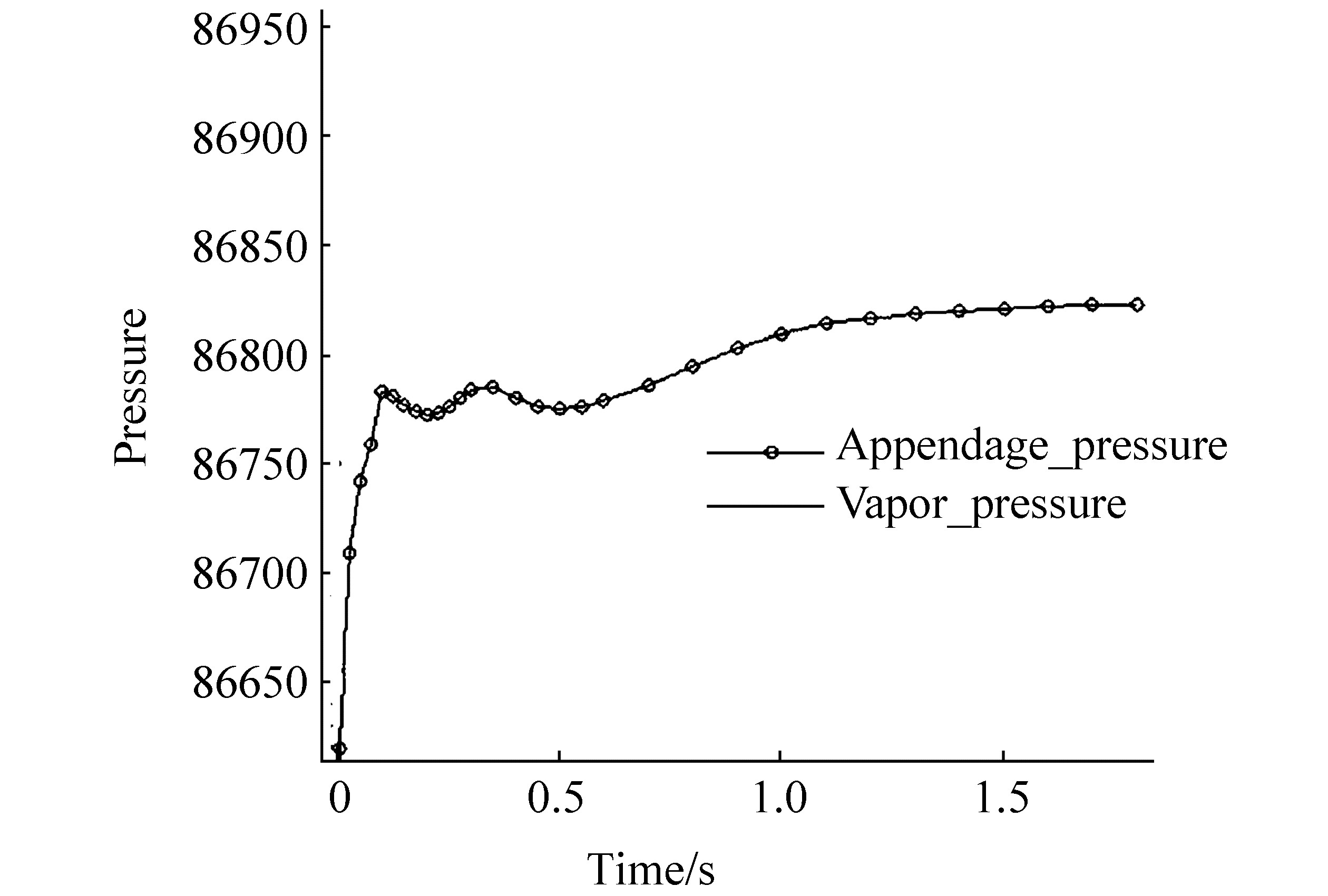

Fig. 11 demonstrates the pressure contours and the respected vapor-liquid volume phases (the cavitating bubble) behind the ACG at different times of t=0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 1.5. From this figure, the pressure behind the ACG is always below the saturated vapor pressure, and the cavitating bubble never disappears. More details of the pressure's change versus time behind the appendage are illustrated in Fig. 12, where the pressure at a fixed point is traced through time for 2 s. Fig. 12 shows that for the entire time, the pressure will never meet the saturated vapor pressure; as a result, the generated artificial cavitating bubble never vanishes. Moreover, from Fig. 12 one can observe that the pressure values remain unchanged for t > 1.5 s. This finding means that for t > 1.5 s, the shape, size, and location of the cavitating bubble are expected to be constant, which will be shown later.

|

| Figure 11 Pressure (top) and phase contours (down) at different times |

|

| Figure 12 Pressure values versus time behind the appendages and the comparison with the saturated vapor pressure (solid line without circle) |

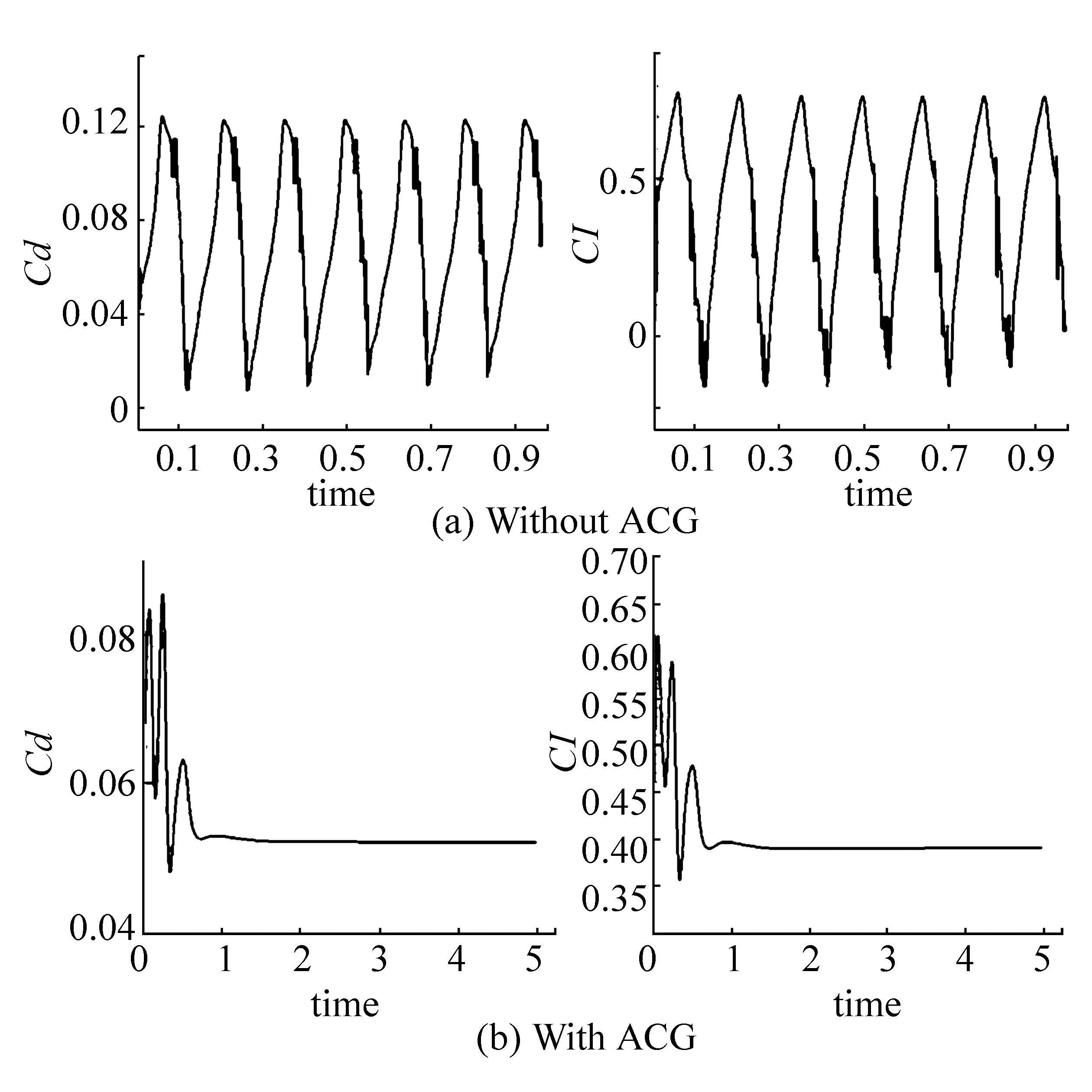

With the use of this new idea, the bubble size and the periodic behavior of the cavitation growth and collapse are expected to be controllable. In Fig. 13, the drag and lift coefficients are shown in time, (a) hydrofoil without ACG and (b) with the presence of ACG. When the ACG is used, the period of growth and collapse of the bubble are completely different from those of the simple hydrofoil. For the simple hydrofoil, a fully periodic behavior for the lift and drag coefficient can be seen, whereas when the ACG is added to the suction surface of the hydrofoil, a decaying oscillatory behavior is observed, which reaches a stationary state after 1.5 s. This result means that the formation, growth, and dissipation of the cavitating bubble after a while reaches a steady state with respect to the bubble shape and size. This finding is clearly shown in Fig. 13, which presents the results obtained after 5 s. After t=1.5 s, the lift and drag coefficients are constants, and the bubble shape and size also remain unchanged.

|

| Figure 13 Drag and lift coefficients on the hydrofoil (a) without ACG, (b) with ACG |

In the simple case, a cyclic behavior is observed. This behavior is due to the formation of a re-entrant jet and subsequent impact of a water jet on the cavity interface. This cyclic behavior is shown in Fig. 13(a). However, when the ACG is used on the hydrofoil surface in a proper manner, the dynamics of the bubble formation and collision are completely changed, thereby creating a thinner cavitation sheet, and a steady behavior is observed as shown in Fig. 13(b). Therefore, after 1.5 s, the shape of the bubble remains unchanged with respect to time. Consequently, a drastic reduction in noise generation, unpleasant and unsteady side force effects, and surface erosion is expected.

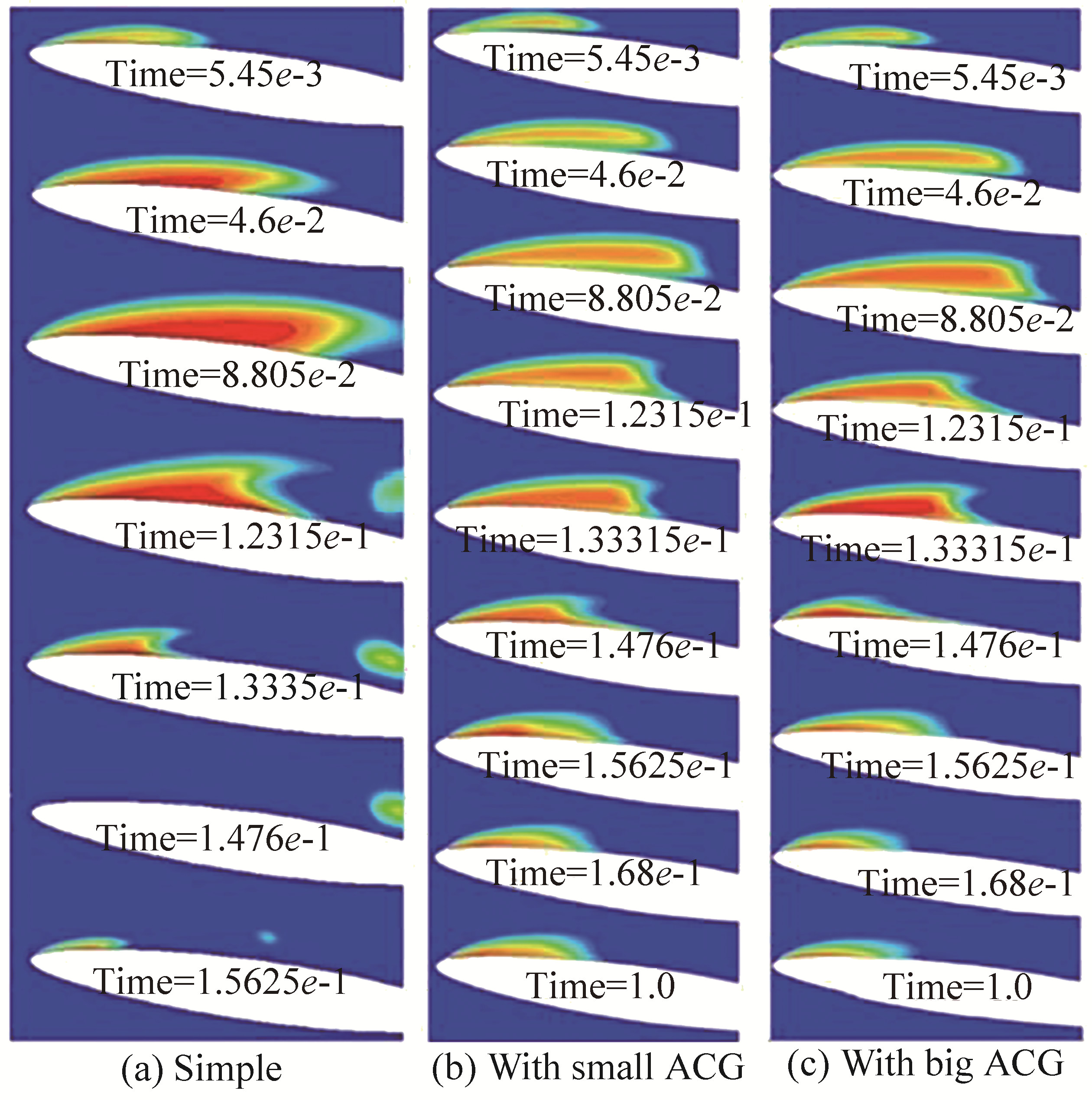

To analyze the effect of the ACG design on its performance, we conducted numerous investigations on the size and location of the ACG. The sensitivity of the results to the size of the ACG is shown in Fig. 14. The figure clearly shows that changing the size of the ACG changes the steady bubble size and shape. Note that we selected the size and location of the ACG by running many different test cases. When the shape or the location of the bubble was wrong, hydrodynamic efficiency severely decreased, and we were unable to prevent the periodic behavior of the cavitation. The use of an ACG can control (improve) the drag coefficient of a hydrofoil. However, our findings are not shown here because they are not the focus of this paper.

|

| Figure 14 Comparison of the growth and collapse of the cavitation (a) simple, (b) with small ACG, and (c) with large ACG |

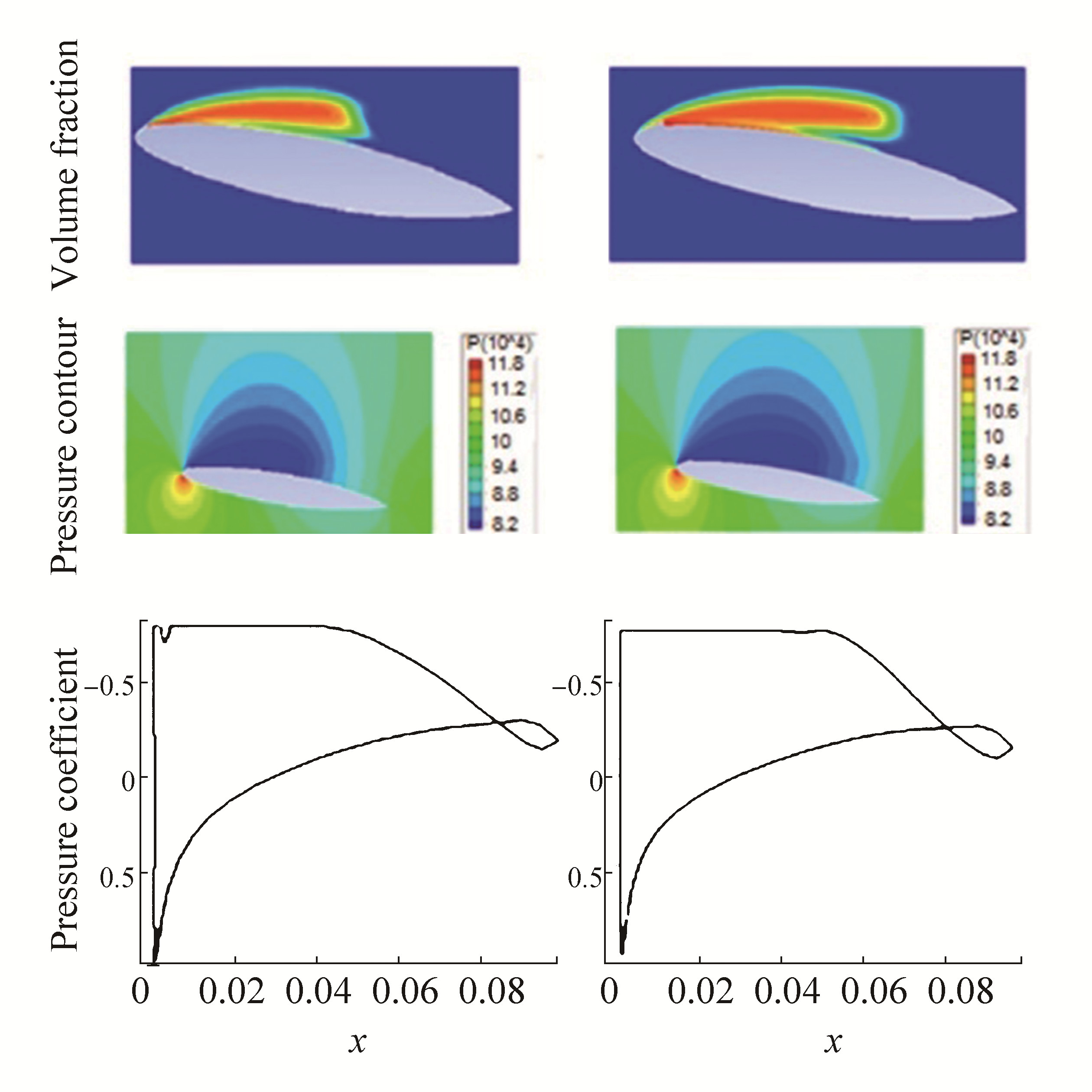

The effects of the appendage location on the results are presented in Fig. 15. Results show that a good location for the ACG is crucial to controlling the cavitation bubble. When the ACG is in an incorrect location, the bubble size can increase and consequently cause damage because of the increased cavitation. Fig. 15 shows two different locations of the ACG. In Fig. 15 (left), the ACG size and location are correct, and thus, the bubble size is small. In Fig. 15 (right), the ACG size and shape are the same as those in the left; however, the location moved downstream. In this case, the cavitation bubble is generated before the ACG, and the positive effects of ACG on cavitation control do not occur. This figure clearly shows that at the proper location of ACG (left), a small jump in pressure distribution on the hydrofoil surface is clearly seen; this jump does not appear in the right side. In conclusion, when the location of the ACG is incorrect, the flow around the hydrofoil cannot be controlled.

|

| Figure 15 Comparison of proper (left) and improper (right) locations of ACG |

In continuous, the effects of the cavitation parameter are investigated. Thus, the hydrofoil without and with appendage is simulated in cavitation parameters 0.4 and 0.8, respectively. As expected, when the cavitation parameter decreases, the size of the bubble cavitation increases. When the appendage is used under different cavitation parameters, its effect is obvious, and it can control the bubble size; this effect is shown in Fig. 16. The left side of Fig. 16 shows the simple hydrofoil, and the right side shows the hydrofoil equipped with the ACG. A comparison between the left and the right shows that the bubble size decreased; consequently, erosion is expected to be reduced. In conclusion, the use of ACG under different cavitation parameters or working conditions is feasible.

|

| Figure 16 Comparison between two different cavitation parameters for simple hydrofoil and hydrofoil with the appendage |

The new concept of ACG is introduced in this work to control cavitation bubbles on propellers and hydrofoils. ACGs creates an area where the local static pressure of the liquid is always below the saturated vapor pressure. Behind the ACG is a recirculation region; at its core, the local static pressure is lower than in other places. A properly designed ACG located in an appropriate position creates a situation where the local static pressure is subjected below the saturated vapor pressure at all times. Results showed that in this case, the ACG acts as the source of bubble cavitation. Given that the pressure will never meet the saturated vapor pressure behind the ACG, the generated artificial cavitation bubble does not disappear over time. Consequently, the ACG affects the entire processes of vaporization, bubble generation, and cavitation bubble implosion. Furthermore, for t < 1.5s, an oscillatory pressure distribution on the hydrofoil surface decayed with time. However, for t > 1.5s, the changes in pressure values behind the ACG remained unchanged. In other words, after t > 1.5s, the shape, size, and location of the cavitating bubble remained constant. As a result, the oscillatory behavior of lift and drag forces changed to a non-oscillating, steady-state condition.

| Alajbegovic A, Gorger HA, Philip H, 1999. Calculation of transient cavitation in nozzle using the two-fluid model. 12th Annual Conference on Liquid Atomization and Spray Systems, Indianapolis, USA. |

| ANSYS Fluent Theory Guide, Release 15. 0, ANSYS, Inc. November, 2013. |

| ANSYS Fluent User's Guide. Release 15. 0. ANSYS, Inc. November, 2013. |

| Brennen CE, 1995. Cavitation and bubble dynamics. New York: Oxford University Press. |

| Coutier-Delgosha O, Deniset F, Astolfi JA, Leroux JB, 2007. Numerical prediction of cavitating flow on a two-dimensional symmetrical hydrofoil and comparison to experiments. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 129(3), 279–292. DOI:10.1115/1.2427079 |

| Coutier-Delgosha O, Fortes-Patella R, Reboud JL, 2003. Evaluation of turbulence model influence on the numerical simulations on unsteady cavitation. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 125(1), 38–45. DOI:10.1115/1.1524584 |

| Dular M, Bachert R, Stoffel B, Širok B, 2005. Experimental evaluation of numerical simulation of cavitating flow around hydrofoil. European Journal of Mechanics-B/Fluids, 24, 522–538. DOI:10.1016/j.euromechflu.2004.10.004 |

| Franc JP, Michel JM, 2004. Fundamentals of cavitation. New York, Boston, Dordrecht, London, Moscow: Kluwer Academic Publisher. |

| Huang B, Young YL, Wang G, Shyy W, 2013. Combined experimental and computational investigation of unsteady structure of sheet/cloud cavitation. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 135, 071301. DOI:10.1115/1.4023650 |

| Ji B, Luo XW, Arndt RE, Peng X, Wu Y, 2015. Large eddy simulation and theoretical investigations of the transient cavitating vortical flow structure around a NACA66 hydrofoil. International Journal of Multiphase Flow, 68, 121–134. DOI:10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2014.10.008 |

| Johansen S, Wu J, Shyy W, 2004. Filter-based unsteady RANS computations. International Journal of Heat and Fluid Flow, 25(1), 10–21. DOI:10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2003.10.005 |

| Kerho MF, Kramer BR, 2003. Enhanced airfoil design incorporating boundary layer mixing devices. AIAA Paper 2003-0211, USA. DOI: 10.2514/6.2003-211 |

| Kim SE, 2009. A Numerical study of unsteady cavitation on a hydrofoil. Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Cavitation, Michigan, USA, No. 56. |

| Kubota A, Hiroharu A, Yamaguchi H, 1992. A new modeling of cavitating flows-a numerical study of unsteady cavitation on a hydrofoil section. Journal of Fluid Mechanic, 240(1), 59–96. DOI:10.1017/S002211209200003X |

| Li DQ, Grekula M, Lindell P, 2009. A modified SST k-ω turbulence model to predict the steady and unsteady sheet cavitation on 2D and 3D hydrofoils. Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Cavitation, Michigan, USA, No. 107. |

| Liu DM, Liu SH, Wu YL, Xu HY, 2009. LES numerical simulation of cavitation bubble shedding on ALE 25 and ALE 15 Hydrofoils. Journal of Hydrodynamics, 21(6), 807–813. DOI:10.1016/S1001-6058(08)60216-4 |

| Lu NX, Bensow RE, Bark G, 2010. LES of unsteady cavitation on the delft twisted foil. Journal of Hydrodynamics, 22(5), 784–791. DOI:10.1016/S1001-6058(10)60031-5 |

| Mostafa NE, Karim M, Sarker MA, 2012. Numerical study of unsteady behavior of partial cavitation on two dimensional hydrofoils. Journal of Shipping and Ocean Engineering, 2, 10–17. |

| Reboud JL, Stutz B, Coutier O, 1998. Two-phase flow structure of cavitation:experiment and modelling of unsteady effects. Grenoble, France:Third International Symposium on Cavitation. |

| Seo JH, Lele SK, 2009. Numerical investigation of cloud cavitation and cavitation noise on a hydrofoil section. Michigan, US: Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Cavitation. |

| Wu J, Utturkar Y, Shyy W, 2003. Assessment of modeling strategies for cavitating flow around a hydrofoil. Fifth International Symposium on Cavitation (Cav2003), Osaka, No. cav03-OS-1-7, 1-4. |

| Yang J, Zhou LJ, Wang ZW, 2011. Numerical simulation of three-dimensional cavitation around a hydrofoil. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 133(8), 081310. DOI:10.1115/1.4004385 |

| Zhou L, Wang Z, 2008. Numerical simulation of cavitation around a hydrofoil and evaluation of a RNG κ-ε model. ASME Journal of Fluids Engineering, 130(1), 011302. DOI:10.1115/1.2816009 |