2. Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Malek Ashtar University of Technology, Esfahan 83145-115, Iran

1 Introduction

Axisymmetric bodies, such as a submersible vehicle, experience complex three-dimensional flows during depth maneuvers. Ericsson and Reding (1986) characterized four distinct regions of a flow around a slender body subjected to a flow with an angle of attack of 0°-90°. At small angles of incidence, the flow is attached to the body, and the axial flow field is dominant. However, there are linear variations in the lift force and pitching moment with the incidence of the angle. At intermediate angles, the formation of the cross-flow creates an adverse circumferential pressure gradient, the boundary layer is separated, and a symmetric vortex pair forms on the leeside of the object, but there is no out-of-plane force or moment, and there is a nonlinear relation between the lift force and angle of attack. In contrast, at relatively higher angles of attack, secondary vortices may form in the middle of the main body, and when the incidence angle is further increased, the cross-flow vortices become asymmetric and induce a side force and yawing moment. Finally, at very high angles, the flow pattern becomes similar to the flow pattern across a cylinder.

For a submarine with an axisymmetric hull, the hull experiences intermediate angles of attack. Thus, it is essential to gain an understanding of the nature of vortical flow structures and cross-flow separation. Therefore, this study investigates the vortical flow around a submarine utilizing Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and experimental methods. However, to accurately capture the vorticity field in the CFD simulation based on the Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) two factors need to be satisfied: the creation of a fine mesh and the choice of an appropriate turbulence model.

To improve the hydrodynamic performance of a submersible object, it is important to understand the detailed flow structure around a body. Constantinescu et al. (2002) simulated the flow around a prolate spheroid and compared the Detached Eddy Simulation (DES) results with those of experimental data and RANS simulations using the Spalart-Allmaras turbulence model. In general, the predictions of mean properties of the flow field were found to be similar for both RANS and DES models. In addition, Sreenivas et al. (2003) simulated a flow around the SUBOFF model with sail at various angles of drift using the finite volume method; results revealed that appendages induced complex vortical structures in the submarine flow field. Furthermore, Wu et al. (2005) simulated the wake flow behind an appended submarine using RANS equations and the SST turbulence model.

Clarke et al. (2008) simulated a flow around a prolate spheroid at an incidence angle of 10° using commercial Fluent software and realizable k-ε and shear stress transport turbulence models. The RANS simulations were then compared with experimental data for surface pressures and streamlines, and a good agreement was found. De Barros et al. (2008) presented a comparative study of computational, analytical, and semi-empirical (ASE) methods to predict the normal force and moment coefficients of an autonomous underwater vehicle. The solver adopted in CFD simulations was that of Fluent commercial software, and the shear stress transport turbulence model was employed. Results were validated with experiments conducted in a towing tank. The CFD calculations provided very good predictions for the bare-hull normal force and moment coefficients. The information provided by flow visualization and pressure distribution experiments were very useful for selecting and adjusting ASE formulas to predict parameters based on vehicle geometry.

Vaz et al. (2010) then used the finite element and finite volume schemes to investigate the flow around a bare and appended SUBOFF hull, with the aim of verifying the accuracy of maneuvering force predictions. Results showed that both solvers are capable of predicting the flow around a submarine hull. Furthermore, Saeidinezhad et al. (2015) experimentally studied the separation and formation of a cross-flow vortex over two axisymmetric bodies of revolution with different nose shapes at various angles of incidence. Visualization results showed the effects of nose shape on the vortical flow structure and separation and reattachment locations. Furthermore, longitudinal and circumferential surface pressure measurements were conducted over the model’s surface. It was found that the cross-flow pressure gradient caused the separated sheet to roll up and extend to the flow at the leeward side of the body and that primary and secondary cross-flow vortices were formed around the model’s surface.

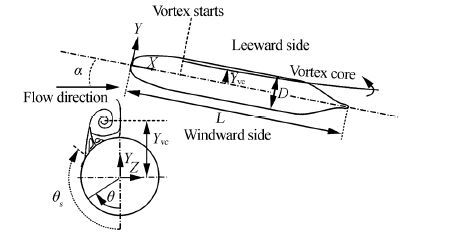

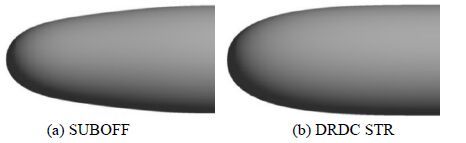

However, it is evident from available literature that a detailed structure of the cross-flow pair vortices, including clarification of the separation and reattachment points, core vortex locations along the body, and the separated vortex strength have not been fully reported. Moreover, the influence that two common standard bows have on detailed flow information has not been previously addressed. Therefore, the present study is devoted to exploring the effect of submarine bow shapes on detailed features of the cross-flow vortices generated around a SUBOFF submarine model subjected to a flow with an incidence angle of 20°. This angle was selected because it is considered to be an intermediate angle for a submarine body when a steady symmetric body vortex pair is created on the leeside of the hull. The SUBOFF bow (Groves et al., 1989) and the DRDC STR bow (Mackay, 2003) are selected for both the numerical simulation and the experimental study to explore the influence of the nose shape on the vortical flow field around the considered models. Fig. 1 shows a schematic of the SUBOFF submarine model, the Cartesian coordinate system, and the body vortex notations, where L is the length and D the diameter of the submarine model, α is the angle of incidence, θs is the flow separation angle, and YVC is the height of the vortex measured from the centerline. Fig. 2 then shows the two bow shapes selected for the current investigation. The numerical simulation adopted is based on a RANS approach with an SST turbulence model.

|

| Fig. 1 Schematic of the SUBOFF submarine model, the Cartesian coordinate system, and body vortex notations |

|

| Fig. 2 Two bow shapes |

To consider the limitations of the experimental conditions, the specifications of the model were selected as follows. The main body is an axis-symmetric revolution body with a total length of 229 mm; the length of the bow, parallel middle body, and stern are 53.4, 117.1, and 58.5 mm, respectively; and the maximum diameter of the body is 26.7 mm. A schematic view of the SUBOFF model, with a central plane cross section and the Cartesian coordinate system used for measuring the cross-flow vortex locations, is shown in Fig. 1.

2 Experimental setupA smoke flow visualization was conducted in a smoke wind tunnel to determine the cross-flow vortex structures formed around the model. The test section of this vertical tunnel has a rectangular cross-section with dimensions of 100×180 mm2. Gasoil was heated to produce smoke, and this was injected into the smoke tunnel by an airfoil shaped probe. The smoke tunnel was powered by a variable speed electric fan mounted at the top of the test section, and the turbulence intensity of the smoke tunnel was lower than 0.5% in the range of the free stream velocity considered. The laser illumination technique was used to capture the cross-flow characteristics, and the movement of the smoke-lines was captured by a Canon camera with a shutter speed of 1/13s. Details of the experimental flow visualization can be found in Saeidinezhad et al. (2015) . The transverse height of the vortex core was calculated from the laser illumination images at various streamwise locations. An image of the vortex was then imported into an Aut℃AD program and the vertical distance between the vortex core and the model centerline (YVC) was deduced. The results are presented as a dimensionless form of YVC /D.

3 Computational model3.1 Governing equationsThe motion of fluid past the three-dimensional body under consideration was modeled using the incompressible and isothermal Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) equations. The most common turbulence modeling approach currently used is RANS, which is based on statistical treatment of the fluctuations about the mean flow (Pope, 2000; Wilcox, 1998). The continuity and momentum equations for the flow past an axisymmetric underwater vehicle in the Cartesian coordinate are given by

$\nabla \cdot \bar V = 0$

(1)

$\rho \frac{{D\bar V}}{{Dt}} = - \nabla P + \nabla \cdot {\tau _{ij}} + {f_i}$

(2)

where the stress tensor, τij, is total stress and consists of two parts: viscous stress and turbulent stress (or Reynolds stress):

${\tau _{ij}} = \mu {\rm{}}\left ( {{{\partial {{\bar u}_i}} \over {\partial {x_j}}} + {{\partial {{\bar u}_j}} \over {\partial {x_i}}}} \right) - \rho \overline {u{'_i}u{'_j}} $

(3)

The influence of turbulence on the mean flow is represented in Eq. (3) by the Reynolds stress tensor $\rho \overline {u{'_i}u{'_j}} $. In these equations, ρ is the density, μ is the laminar viscosity, $\bar V$ is the mean Cartesian flow velocities, ${u{'_i}}$ is the fluctuating components of the instantaneous flow velocities, P is the mean pressure of the fluid flow around the hull, and fi represents the external body forces that are considered to be zero.

To close the fluid flow equations and model the Reynolds stress terms, a robust turbulence model is needed. Shear Stress Transport (SST) turbulence modeling was thus selected for the present work, as it has been shown capable of accurately predicting the onset of flow separation under adverse pressure gradients (ANSYS, 2011; Menter, 1994). The SST is a two equation eddy viscosity model developed by Menter (1994) to effectively blend the robust and accurate formulation of the k-ω model in the near-wall region (in the inner boundary layer) with the free-stream independence of the k-ε model in the outer boundary layer.

3.2 Numerical implementationIt is necessary to adopt a numerical approach to obtain solutions for real flows, and therefore, in the present work, RANS equations were implemented in the commercial CFD code ANSYS CFX 14 (ANSYS, 2011). ANSYS CFX uses an element-based finite volume method for discretization of the governing equations. This method employs finite element shape functions to describe the flow variables between nodes. A control volume is constructed around each mesh node using lines that join the element centers surrounding the node. As with the finite volume method, conservation equations are applied to the control volume in the integral form. The fluxes passing the boundaries of the control volume and the source terms are calculated based on the element shape functions. A high-resolution advection scheme was employed for a scalar quantity φ, and the advection scheme is written as follows

${\varphi _{ip}} = {\varphi _{up}} + \beta \nabla \varphi \cdot \Delta {\bf{r}}$

(4)

where φip is the value of the scalar field at the integration point, φip is the value at the upwind node, $\Delta {\bf{r}}$ is the vector connecting the upwind node to the integration point, and β is the blend factor. The model is a first order when β = 0, and is a second order upwind biased scheme for β = 1. The quantity $\beta \nabla \varphi \cdot \Delta {\bf{r}}$, known as the Numerical Advection Correction, may be viewed as an anti-diffusive correction tat is applied to the upwind scheme. The high-resolution scheme adapted calculates β using a similar approach to that given by Timothy and Dennis (1989) . In general, in flow regions with low variable gradients the blend factor will be close to 1.0, while in regions where there are sharp gradients the blend factor will be close to 0.0 to prevent overshoots and undershoots and to maintain robustness of the numerical scheme.

Collocated grids are used for all transport equations, and pressure velocity coupling is achieved using the interpolation scheme proposed in Rhie and Chow (1983) . Gradients are computed at integration points using the trilinear shape functions defined in ANSYS (2011) . The linear set of equations that arise by applying the finite volume method to all elements in the domain are discrete conservation equations, and the system of equations is solved using a fully coupled solver and a multi-grid approach.

For the present study, simulations were continued until the normalized RMSs of all residuals (pressure, velocity, and turbulence components) satisfied the convergence criteria of 1×10-6. The CFD modeling was initially validated with the experimental data, and was then extended to investigate the flow detail and vortical flow structure around the model. A strong emphasis was placed on constructing a high quality grid, and then employing an appropriate turbulence modeling to capture the best physical features of the fluid flow.

3.3 Domain and gridThe CFD approach requires considerable experience in grid generation as it needs to validate the adopted numerical models. For the present work, a structured mesh was built using a commercial mesh generating package, ANSYS ICEM CFD V14. ANSYS ICEM CFD provides advanced geometry acquisition, mesh generation, and mesh optimization tools to meet the requirement of integrated mesh generation for today’s sophisticated geometries. An O-grid topology was applied around the hull, and special care was taken to obtain a smooth transition between mesh sizes from one block to the next.

The first layer of cells around the main body represents the basic computational mesh used for numerical computations, and this has key effects on the accuracy of the numerical results. Hence, the values of y+<2 were used for the nodes nearest the surface. Initially, the first cell thickness, Δy, was estimated using the following relation (ANSYS, 2011).

$\Delta y = L\Delta {y^ + }\sqrt {74} R{e_L}^{ - 13/14}$

(5)

$R{e_L} = \frac{{\rho UL}}{\mu }$

(6)

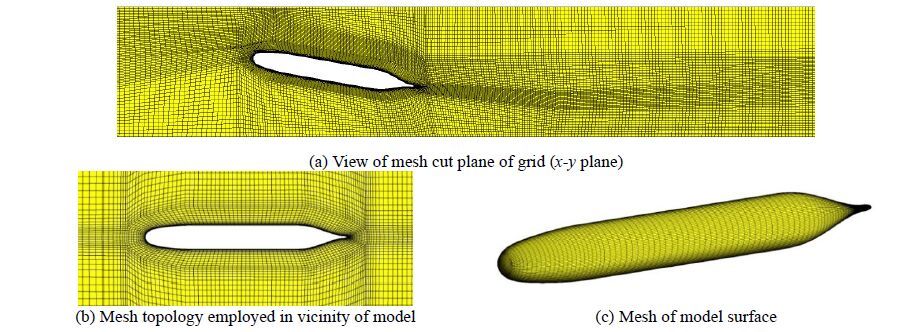

After initial simulations, the first layer thickness was tuned to ensure that it matched the desired value of y+ < 2. In Fig. 3a, a view of the mesh in the x-y plane of the grid is presented. This mesh is coarsened for presentation purposes in Fig. 3b, which emphasizes the mesh topology employed in the vicinity of the submarine model. The mesh on the model surface is also shown in Fig. 3 (c) . The grids were appropriately resolved in the area of wake formation to capture details of the vortex structures. To study the grid independency of numerical results, the mesh was refined until the vortex shapes were rounded and coincided. The fine mesh ultimately contained 1 333 865 elements.

|

| Fig. 3 The mesh topology around the submarine model |

To compare and validate numerical results with experimental observations, boundary conditions for the CFD simulation were selected according to the real experimental conditions conducted in the wind tunnel. A normal flow with a constant velocity (2 m/s) and a 0.5% turbulence intensity was imposed at the inlet of the computational domain. Opening conditions of constant static pressure on the outlet of the computational wind tunnel and a no-slip wall condition on the SUBOFF body and tunnel surfaces were also selected.

In the present numerical study, the near-wall treatment available in ANSYS CFX was selected, which automatically switches from wall-functions to a low-Re near wall formulation depending on the local y+. This near wall boundary condition, known as the automatic near wall treatment in CFX, was used as the default in all turbulence models based on the ω-equation, including the SST model (ANSYS, 2011).

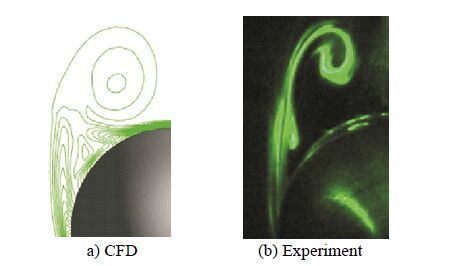

4 Results and discussion4.1 Comparison of numerical and experimental resultsA comparison of the vortical flow fields derived from CFD modeling and the flow visualization experiment is shown in Fig. 4. The flow field around the model is dominated by a pair of vortex sheets on the leeside of the submarine hull. In order to validate the numerical scheme employed, the computed location of vortex cores from the axis of the submarine hull at a 20° incidence angle were compared with the experimental test results for an upstream velocity of 2 m/s. The results are presented in Table 1 for a submarine with a SUBOFF bow and in Table 2 for a submarine with a DRDC STR bow. The results indicate that there is good agreement between the experimental and numerical data, and it is therefore concluded that the selected CFD model is able to reproduce the essential physics responsible for the cross-flow separation and vortical flow structure on the separated region. In the next section, the computed results (including the pressure and wall shear stress distribution, flow separation angle, strengths, and locations of the vortex structures) are presented at an intermediate incidence angle of 20°.

|

| Fig. 4 Comparison between numerical predictions of vortical flow on the leeside and flow visualization observations for the SUBOFF hull at β = 20° and X/L = 0.6 |

| X/L | Exp. | CFD | Absolute error / % |

| 0.4 | 0.593 6 | 0.599 2 | 0.948 |

| 0.5 | 0.669 0 | 0.666 7 | 0.349 |

| 0.6 | 0.697 9 | 0.719 1 | 3.027 |

| 0.7 | 0.742 1 | 0.764 0 | 2.955 |

| 0.8 | 0.743 8 | 0.783 5 | 2.715 |

| 0.9 | 0.830 8 | 0.775 3 | 6.691 |

| X/L | Exp. | CFD | Absolute error / % |

| 0.4 | 0.599 2 | 0.638 9 | 6.634 |

| 0.5 | 0.682 5 | 0.685 4 | 0.420 |

| 0.6 | 0.720 1 | 0.731 8 | 1.625 |

| 0.7 | 0.715 2 | 0.771 5 | 7.872 |

| 0.8 | 0.837 0 | 0.791 4 | 5.452 |

| 0.9 | 0.815 0 | 0.776 4 | 4.736 |

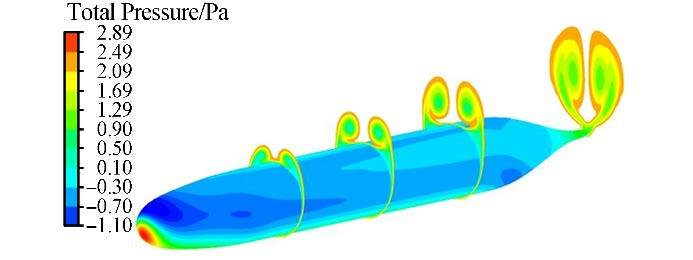

The numerical prediction of the pressure coefficient over the SUBOFF hull surface, and the pressure coefficient field at various longitudinal cross sections are illustrated in Fig. 5. It can be seen that the flow separates and rolls up into a vortex pair. This separation region produces significant pressure differences across the hull, which is responsible for the imposed forces.

|

| Fig. 5 Total pressure coefficient contours on the hull surface and cross-sectional planes (X/L = 0.3, 0.5, 0.7, and 1.0) along the SUBOFF hull at 20 ̊ incidence |

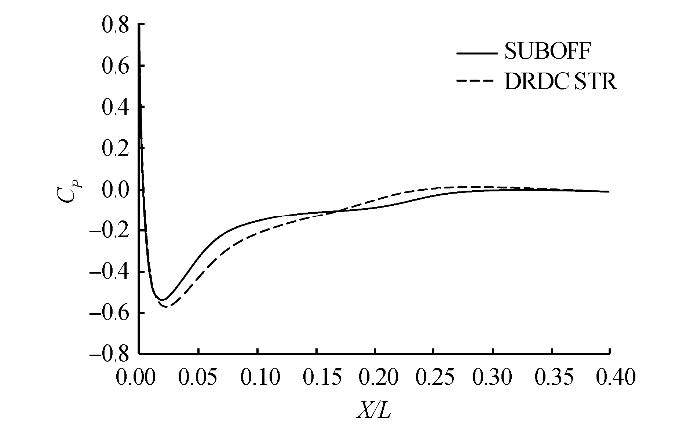

Fig. 5 clearly shows the complexity of the flow, particularly on the leeward side of the hull. Flow stagnates on the windward side of the bow and accelerates over the curvature of the hull. An attached 3D boundary layer is formed on the windward side, while on the leeward side the flow separates from the body due to the adverse pressure gradient. The separated flow leads to the formation of two free vortex sheets that roll up to form the pair of body vortices on the back of the body. In the middle of the hull, secondary vortices begin to form leeward of the primary vortices. The primary vortex location is close to the hull in the first longitudinal cross-section, X/L = 0.3, but is detached from the body surface at the second cross-section, X/L = 0.5, where it becomes more circular and increases in size. Fig. 6 compares the pressure distribution coefficient along the leeward side of the hull (at θ=180°) for the two types of bows (SUBOFF and DRDC STR) at a 20° flow incidence. The figure indicates that the adverse pressure gradient for the DRDC STR bow is greater than that of the SUBOFF in regions close to the nose. The pressure coefficient in the flow is expressed in the following non-dimensional form.

|

| Fig. 6 Longitudinal pressure distribution at the leeward side of the hull at θ = 180° |

${C_P} = \frac{{P - {P_0}}}{{1/2\rho {U^2}}}$

(7)

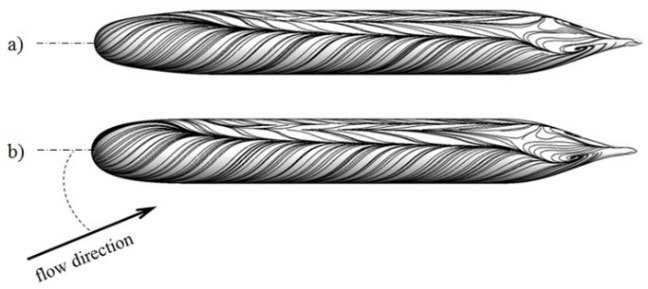

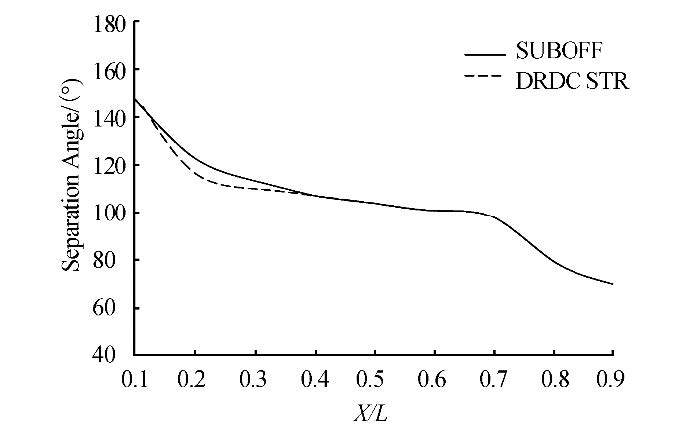

Fig. 7 compares the wall shear stress lines for the submarine hull model using SUBOFF and DRDC STR bows subject to a flow with a 20° angle of incidence. Separation is indicated by the convergence of skin friction lines, while the divergence of skin friction lines indicates reattachment of flow on the body. Fig. 8 compares the flow separation angles, θs, along the submarine hull for the two types of bows. It can be seen that the influence of the nose shape on the separation angle is limited to 0.4 L of the body length, while both curves collapse in to each other along the rest of the body. The flow separation angle for the submarine with the DRDC STR bow is less than that with the SUBOFF bow for X/L < 0.4. For the DRDC STR bow, the separation line moves to the windward side, thereby increasing the size of the separated zone, which consequently leads to a stronger vortex formation and higher imposed lift and drag forces.

|

| Fig. 7 Wall shear stress lines at 20° incidence for submarine model with: a) SUBOFF bow, b) DRDC STR bow |

|

| Fig. 8 Flow separation angle along the submarine hull for both bows |

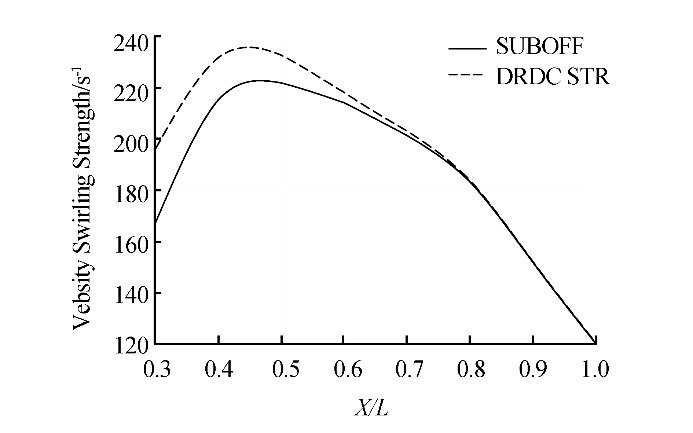

The swirling strength is an imaginary part of the complex eigenvalues belonging to the velocity gradient tensor (which is presented in (8) (ANSYS, 2011), and its value represents the strength of the swirling motion around local centers.

${\bf{}} = \left[ {{d_{ij}}} \right] = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

{{d_{11}}}&{{d_{12}}}&{{d_{13}}}\\

{{d_{21}}}&{{d_{22}}}&{{d_{23}}}\\

{{d_{31}}}&{{d_{32}}}&{{d_{33}}}

\end{array}} \right] = \left[ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

{\frac{{\partial u}}{{\partial x}}}&{\frac{{\partial u}}{{\partial y}}}&{\frac{{\partial u}}{{\partial z}}}\\

{\frac{{\partial v}}{{\partial x}}}&{\frac{{\partial v}}{{\partial y}}}&{\frac{{\partial v}}{{\partial z}}}\\

{\frac{{\partial w}}{{\partial x}}}&{\frac{{\partial w}}{{\partial y}}}&{\frac{{\partial w}}{{\partial z}}}

\end{array}} \right]$

(8)

The velocity gradient tensor has one real eigenvalue, λr, and a pair of conjugated complex eigenvalues, λcr ± λci, in which λci is the swirling strength, which represents the strength of the local swirling motion (ANSYS, 2011).

Maximum swirling strength occurs in the vortex core locations, but the strength reduces as it moves away from the vortex core, where it finally approaches to value of zero. Fig. 9 compares variations in the vortex core strength (1/s) and versus axial location (m) for a submarine with both a SUBOFF and a DRDC STR bow. There is an initial increase in the velocity swirling strength at the beginning of the vortex formation, but this then decreases as the longitudinal distance increases beyond X/L=0.5. Such a reduction in strength can be due to the increasing distance of the pair vortex from the submarine hull and formation of secondary vortices. At around X/L=0.5, secondary vortices start to form underneath the primary vortices. It can be seen that the vortex strength values for a submarine with the DRDC STR bow are greater than those with the SUBOFF bow, particularly for X/L<0.5. This is because a greater separation zone is formed with the DRDC STR bow. The vortex strength for the two bows is approximately the same after X/L=0.7, due to alleviation of the nose shape effect beyond X/L=0.7.

|

| Fig. 9 Vortex core strength along the model for the two bows |

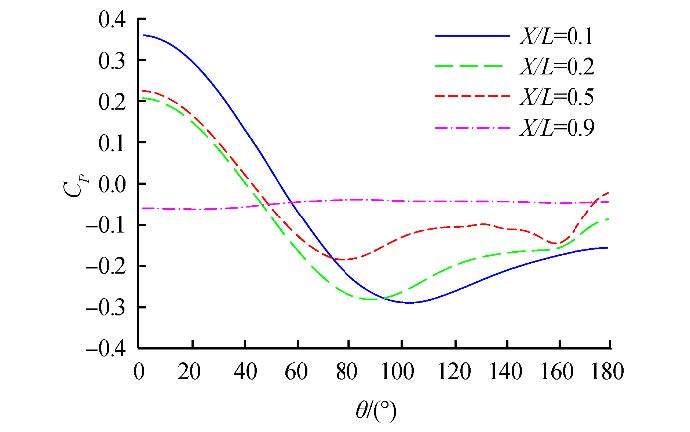

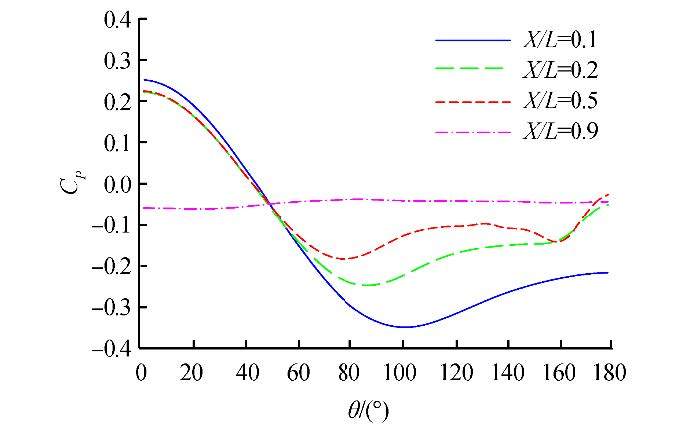

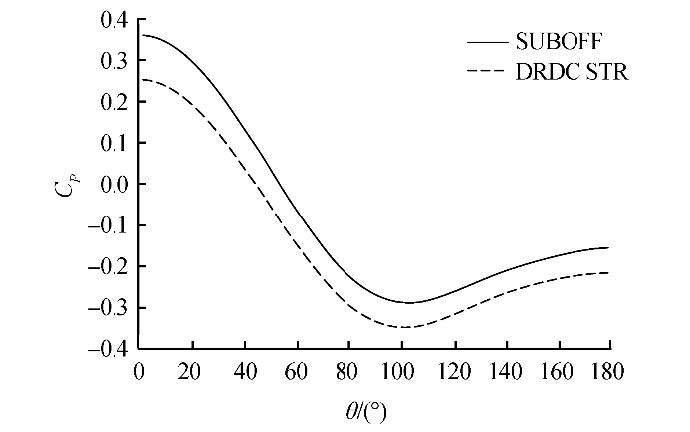

Figs. 10 and 11 show the crosswise pressure distribution over the body at several selected axial locations for a submarine with a SUBOFF bow and a DRDC STR bow. It is possible to see that the pressure distribution is dominated by a favorable pressure gradient on the windward side and an adverse pressure gradient on the leeward side. With increasing axial location, the onset of the adverse pressure gradient occurs earlier, which in turn provides conditions for separation of the boundary layer. Fig. 12 shows the impact of bow type on the crosswise pressure distribution at X/L= 0.1. The lower pressure distribution for the DRDC STR bow leads to a greater pressure difference, and therefore a greater pressure drag. However, the impact of the type of bow on the crosswise pressure distribution is marginal for higher values of X/L.

|

| Fig. 10 Pressure distribution around the hull at several axial locations for submarine with SUBOFF bow |

|

| Fig. 11 Pressure distribution around the hull at several axial locations for submarine with DRDC STR bow |

|

| Fig. 12 Pressure distribution around the hull at X/L = 0.1 for both bows |

To identify the cross-flow separation and reattachment lines, a definition of the skin friction coefficient in the circumferential direction, θ, in the body-fitted coordinates is proposed as:

${C_f}\left ( \theta \right) = \frac{{{\tau _\theta }}}{{\frac{1}{2}\rho {U^2}}} = \frac{{\sqrt {\tau _y^2 + \tau _z^2} }}{{\frac{1}{2}\rho {U^2}}}$

(9)

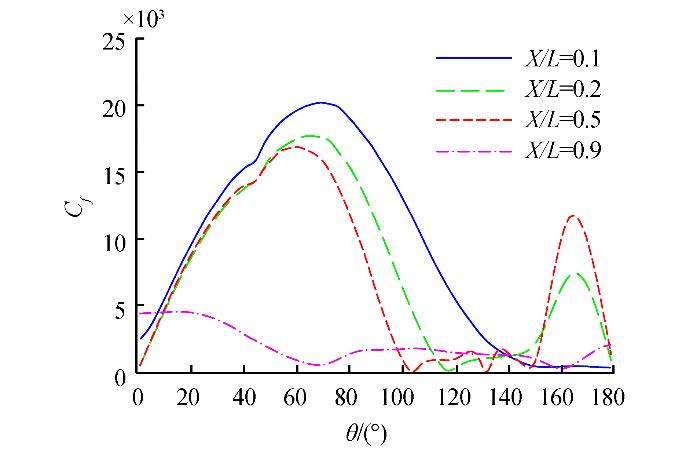

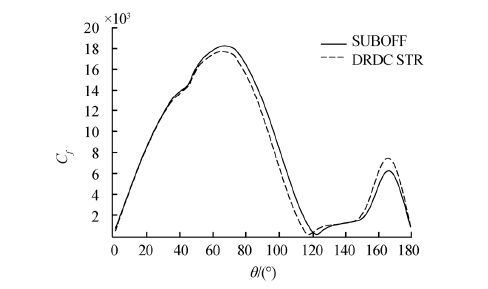

Distributions of the circumpherential skin friction coefficient, Cf (θ), for various longitudinal locations, X/L, are presented in Figs. 13 and 14. The separation point is recognized as the locus of the minimum values of the curves, and local minimums of skin friction clearly reveal the development of both a primary and secondary separation region along the body. As the axial location increases, the minimum occurs at a lower separation angle, which shows a larger separated wake region. It can be seen that there are three local minimums at X/L=0.5; the first minimum is an indication of the first separation point and formation of the primary vortex, the second minimum is related to the reattachment point location on the body, and the third is an indication of the second separation point and hence the onset of the secondary vortex formation. Fig. 15 compares the circumpherential skin frictional coefficient distribution for a submarine with a SUBOFF bow and that with a DRDC STR bow at a longitudinal location of X/L=0.2. As can be seen, the separation point for the DRDC STR bow is located at a lower separation angle than that for the SUBOFF bow, indicating the formation of a larger wake region on the leeward side for the DRDC STR bow .

|

| Fig. 13 Skin friction distribution (Cf) for submarine with SUBOFF bow |

|

| Fig. 14 Skin friction distribution (Cf) for submarine with DRDC STR bow |

|

| Fig. 15 Skin friction distribution (Cf) at X/L = 0.2 for both bows |

Correct resolution of the forces and moments acting on a maneuvering submarine requires an accurate prediction of the flow field structure, a detailed prediction of the cross-flow separation and its location, and the strength of the pertinent body vortices. The flow around a standard SUBOFF bare submarine hull subjected to a flow with a 20° incidence angle equipped with SUBOFF and DRDC STR bows was numerically simulated using RANS simulations with a SST turbulence model, and a comparison between the numerical and experimental results for the shape and location of cross-flow vortices was made. The computed results show good agreement with the experimental measurements.

Results show that flow stagnates on the windward side of the bow, accelerates over the curvature of the hull, and separates on the leeward side due to the existence of an adverse pressure gradient. The separated flow leads to a formation of two free vortex sheets that roll up to form a pair of body vortices on the leeside of the body. In the middle section of the hull, and at around X/L = 0.5, secondary vortices start to form underneath the primary vortices. The circumpherential pressure distribution is characterized by a favorable pressure gradient on the windward side and an adverse pressure gradient on the leeward side, and with an increase in the axial location the adverse pressure gradient occurs earlier and conditions for boundary layer separation are provided. Circumpherential distribution of the skin friction coefficient and a detailed structure of the cross-flow vortices in the vicinity of the hull body clearly reveal the development of both the primary and secondary separation regions along the body, characterized by local minima in Cf (θ). As the axial location increases, the separation points move toward the lower separation angle, which shows a larger separated wake region.

The effects of the nose shape on the flow structure and separation angel were found to be dominant up to the 0.4L of the body length, while the effects were found to be minimal in relation to the rest of the submarine body. It was noted that the flow separation angle for a submarine with the DRDC STR bow is smaller than that for a submarine with the SUBOFF bow, and therefore a submarine equipped with DRDC STR bow experiences a greater separation zone, higher vortex strength, and larger lift and drag forces.

| ANSYS, 2011. ANSYS CFX Release 14.0. |

| Clarke D, Brandner P, Walker G, 2008. Experimental and computational investigation of the flow around a 3-1 prolate spheroid. WSEAS Trans Fluid Mech, 3, 207-217. DOI: 10.1.1.522.1080 |

| Constantinescu GS, Pasinato H, Wang YQ, Forsythe JR, Squires KD, 2002. Numerical investigation of flow past a prolate spheroid. Journal of Fluids Engineering, 124(4), 904-910. DOI: 10.1115/1.1517571 |

| De Barros E, Dantas JL, Pascoal AM, De Sá E, 2008. Investigation of normal force and moment coefficients for an AUV at nonlinear angle of attack and sideslip range. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering, 33(4), 538-549. DOI: 10.1109/JOE.2008.2004761 |

| Ericsson L, Reding J, 1986. Asymmetric vortex shedding from bodies of revolution. Tactical Missile Aerodynamics, 104, 243-296. |

| Groves NC, Huang TT, Chang MS, 1989. Geometric characteristics of DARPA suboff models:(DTRC Model Nos. 5470 and 5471). David Taylor Research Center. |

| Mackay M, 2003. The standard submarine model:a survey of static hydrodynamic experiments and semiempirical predictions.Defence R&D Canada-Atlantic. |

| Menter FR, 1994. Two-equation eddy-viscosity turbulence models for engineering applications. AIAA Journal, 32(8), 1598-1605. DOI: 10.2514/3.12149 |

| Pope SB, 2000. Turbulent flows. Cambridge University Press. |

| Rhie C, Chow W, 1983. Numerical study of the turbulent flow past an airfoil with trailing edge separation. AIAA Journal, 21(11), 1525-1532. DOI: 10.2514/3.8284 |

| Saeidinezhad A, Dehghan AA, Dehghan Manshadi M, 2015. Nose shape effect on the visualized flow field around an axisymmetric body of revolution at incidence. Journal of Visualization, 18(1), 83-93. DOI: 10.1007/s12650-014-0226-1 |

| Sreenivas K, Hyams D, Mitchell B, Taylor L, Briley W, 2003.Physics based simulation of reynolds number effects in vortex intensive incompressible flows. DTIC Document. |

| Timothy B, Dennis J, 1989. The design and application of upwind schemes on unstructured meshes. 27th Aerospace Sciences Meeting, Reno, USA, 89-366. |

| Vaz G, Toxopeus S, Holmes S, 2010. Calculation of manoeuvring forces on submarines using two viscous-flow solvers. ASME 2010 29th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Shanghai, China, 621-633. |

| Wu BS, Xing F, Kuang XF, Miao QM, 2005. Investigation of hydrodynamic characteristics of submarine moving close to the sea bottom with CFD methods. Journal of Ship Mechanics, 9(3), 19-28. |

| Wilcox DC, 1998. Turbulence Modeling for CFD. DCW Industries. |