2. 四川农业大学环境学院, 成都 611130

2. School of Environment, Sichuan Agricultural University, Chengdu 611130

施入土壤中的氮、磷等养分通过地表径流和淋溶的方式进入水体,造成了地下水和地表水污染及富营养化,这一方面加速了土壤的板结、酸化并增加了农业投入,另一方面导致水体缺氧及藻毒素含量增加,威胁到水体生物多样性及人类健康(Richardson,1997; Laird et al., 2010).长期以来,人们采用物理、化学和生物方法从控制土壤氮、磷流失和降低水体氮、磷含量两个方面开展了大量的研究(Abelson,1970).近年来,生物炭因其在碳固定和减排方面的功能,使得利用生物炭还田受到广泛关注(Lehmann,2007).同时,生物炭在水体污染处理方面的应用也倍受重视(Yao et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2014).

有研究表明,生物炭还田可减少土壤中NO3--N、NH+4-N和PO3-4-P的淋滤(Yao et al., 2012).适量生物炭的添加能够减少土壤中11%的NO3--N和69%的PO3-4-P的淋失,同时,NH+4-N的淋失率也可降低至15%以下(Ding et al., 2010; Laird et al., 2010).此外,在利用生物炭去除水体氮、磷的研究方面,以竹木生物炭吸附水中NO3--N,最大吸附量为1.25 mg · g-1(Mizuta et al., 2004).以湿地植物为原料制备的生物炭对NH+4-N和PO3-4-P的吸附量分别可达到17.60 mg · g-1和4.96 mg · g-1(Zeng et al., 2013).由此可见,采用生物炭从土壤和水体两个方面控制氮、磷污染具有一定的潜力.

生物炭在结构上包含抗氧化能力较强的芳香结构和容易被降解的碳氧脂肪结构(Schmidt and Noack, 2000).一般具有比表面积大、孔隙度高、容重小、离子交换量大、表面官能团丰富、性质稳定、偏碱等理化特性,且这些与生物炭的应用功能具有密切的关系(Cheng et al., 2008; Cao,2010; Chen et al., 2011; Mukherjee et al., 2011; Kameyama et al., 2012).而生物炭的理化特性受到热解条件的影响和调控(Inyang et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2010).因此,为了开发生物炭在氮、磷的控制方面的功能,需对热解条件进行深入的研究.

为了进一步明确热解条件对生物炭氮、磷吸附性能的影响规律,本研究以橡木木屑为原料,在不同热解终温、升温速率和恒温时间下制备各类生物炭.研究各类生物炭对水溶液体系中氮、磷的去除效率,并结合各类生物炭的理化特性,分析生物炭对氮、磷吸附的机制.以期为生物炭在氮、磷污染控制方面的应用提供必要的理论参考和技术支撑.

2 材料与方法(Materials and methods) 2.1 主要实验材料橡木(主要成分见表 1)收集于四川省都江堰市某加工厂,粉碎过40目筛后,105 ℃烘干备用.NaNO3、NH4Cl、Na3PO4(均为AR级,购于万科化学试剂公司)用于配制NO3--N、NH+4-N和PO3-4-P溶液.

| 表 1 橡木基本物质组成 Table 1 The composition of oak |

将粉碎烘干后的橡木屑粉30 g置于石英舟坩埚中,在管式炉(OTL-1200型,南京南大仪器厂)中,以氮气作为保护气,按照设定的参数进行热解,待装置冷却至室温后,收集生物炭.考察热解终温的影响时,控制恒温时间和升温速率分别为30 min和10 ℃ · min-1,热解终温分别为300、400、500、600 ℃,对应生物炭标识为MT-300、MT-400、MT-500、MT-600.考察升温速率的影响时,控制热解终温和升温速率分别为400 ℃和10 ℃ · min-1,升温速率分别为5、10、15、20 ℃ · min-1,对应生物炭标识为HR-5、HR-10、HR-15、HR-20.考察升温速率的影响时,控制热解终温和升温速率分别为400 ℃和10 ℃ · min-1,恒温时间分别为30、60、90、120 min,对应生物炭标识为HT-30、HT-60、HT-90、HT-120.

2.3 氮、磷吸附配制25.80 mg · L-1 NH+4-N、20.00 mg · L-1 NO3--N、61.30 mg · L-1 PO3-4-P溶液.称取生物炭0.10 g于150 mL三角瓶中,对应加入50 mL溶液后密封.在25 ℃空气浴恒温摇床(HZQ-QX型,东联电子)内,以120 r · min-1的转速振荡24 h.此后,取5 mL样品,过0.45 μm滤膜后,采用离子色谱(ICS-90型,戴安)测定滤液中NH+4、 NO3-和PO3-4浓度.每个处理3个重复,并做空白参照,结果为3次重复的平均值.

2.4 理化性质测定与表征pH测定时以生物炭按1 ∶ 20(m/V,g/mL)与高纯水混合后,采用pH计(PHS-3C型,上海雷磁)测定;采用元素分析仪(Vario MICRO,Elementar)分析C、H、O含量;比表面积采用BET-N2法,通过比表面积测定仪(NOVA 2200E,Quantachrome)测定;利用傅立叶变换红外光谱仪(6700型II,赛默飞)测定生物炭在400~4000 cm-1的红外光谱;生物炭表面电负性利用Zeta电位分析仪(Nano S90,马尔文)检测;生物炭表面元素利用能谱分析仪(SU1510,日立)测定.

3 结果与讨论(Results and discussion) 3.1 热解条件对生物炭产率的影响如表 2所示,当热解终温度由300 ℃增加至600 ℃,生物炭的产率由76.17%降低至21.60%,极差为54.57%.其中,当温度由300 ℃提高至400 ℃时,产率降低明显,此后,生物炭的产率变化较小.这主要是由于构成生物质的三大组分(半纤维素、纤维素和木质素)的热稳定性能差异造成(Chen et al., 2013),且本研究结果与文献报道结果一致(Angιn,2013; Recari et al., 2014).

| 表 2 热解条件对生物炭产率的影响 Table 2 The influence of pyrolysis conditions on biochar yield |

当升温速率由5 ℃ · min-1 增加至20 ℃ · min-1时,产率由30.85%降低至30.43%,极差为0.42%.升温速率影响颗粒内部热量和物质传递,在低升温速率下传热和传质较慢,而在较高升温速率时,一定程度上加速了传热和传质,因此,低升温速率时产率较高而高升温速率下的产率较低(Haykiri-Acma et al., 2006).另外,低的升温速率导致热解体系较长的停留时间,有利于焦油的二次反应,形成更多的炭产物(Angιn,2013; Chen et al., 2014).

当恒温时间由30 min延长至120 min时,产率由30.43%降低至28.27%,极差为1.16%.一般而言,增加恒温时间有利于炭的二次反应及炭结构的发育,从而减少炭的产率(Kuzyakov et al., 2009; Cimò et al., 2014).此外,有研究表明低热解终温下,不同恒温时间所制备生物炭的产率之间差别较大,而随着热解终温的增加,不同恒温时间所制备生物炭的产率差别较小(Kumar et al., 2013).

由上可见,生物炭的产率都随热解终温、升温速率和恒温时间的增加而逐渐降低.通过比较生物炭产率的极差可得,热解终温对生物炭产率影响最大,恒温时间次之,升温速率最小.

3.2 热解条件对生物炭理化性质的影响如表 3所示,随热解终温、升温速率和恒温时间的增加,所得生物炭的pH增加.各热解条件下获得的生物炭pH为6.83~8.47,与其他木质纤维素类原料生物炭接近(Lehmann,2009; Yao et al., 2012).增加热解终温导致pH的增加,是由于碱盐逐渐地从生物质结构中分离出来及生物炭表面碱性官能团逐渐增加导致(Ahmad et al., 2012; Kameyama et al., 2012).升温速率越高所带走的挥发分越多,其中,挥发分中多含有致酸性物质,导致生物炭的pH随升温速率的增加而增加.延长恒温时间有利于炭的进一步发育,生物炭结构中的酸性物质逐渐分解,导致pH增加(Shaaban et al., 2014).

| 表 3 不同热解条件对生物炭基本理化性质的影响 Table 3 Physical-chemical characteristics of biochar produced at different pyrolysis conditions |

由工业分析结果可见,当热解终温由300 ℃增加到600 ℃时,灰分、固定碳和挥发分的变化范围分别为0.85%~3.58%、24.71%~78.75%和71.02%~2.36%.随着热解终温、升温速率和恒温时间的增加,生物质的木质纤维素结构逐渐分解,大量挥发分析出,热稳定性能较高的固定碳积累增多,同时灰分相对增加(Yaman,2004; Cao et al., 2010).

由元素分析可知,随热解终温、升温速率和恒温时间的增加,C含量不断增加,而H和O含量逐渐降低.C含量增加表明炭化程度增强,而H和O含量降低是因为热解过程它们以小分子有机物和水的形式析出(Antal et al., 2003; Peng et al., 2011; Ahmad et al., 2014).

随热解终温的增加生物炭H/C和O/C在降低,尤其是当热解终温由300 ℃上升至400 ℃时,H/C和O/C显著降低,说明300 ℃的生物炭具有较强的亲水性和脂肪性.而400 ℃时,由于生物质的进一步热解,H和O进一步析出,生物炭表现出较强的疏水性和芳香性.超过500 ℃后,H/C基本保持0.04,表明此温度下的生物炭芳香性较高,稳定性较强.随升温速率的增加,O/C由0.35降低至0.30,而H/C基本稳定在0.06,说明升温速率对生物炭芳香性无影响,而亲水性降低,不同恒温时间下H/C和O/C基本恒定,说明恒温时间对生物炭芳香性和亲水性无影响.此外,O/C还可以表征生物炭的阳离子交换量(CEC),O/C越大则CEC越大(Shaaban et al., 2014).从表 3可见,随着热解终温和升温速率的增加,生物炭的CEC降低,而恒温时间对CEC没有影响.

当热解终温为300 ℃时,生物炭的比表面积仅为0.05 m2 · g-1,这可能是由于生物质炭化不完全,孔结构基本未发育造成.而随热解终温的提高,挥发分大量逸出,生物炭的孔隙结构逐渐发育,使生物炭的比表面积也逐渐增加(Ding et al., 2014; Shaaban et al., 2014).当升温速率由5 ℃ · min-1上升至20 ℃ · min-1时,生物炭的比表面积由4.28 m2 · g-1降至1.48 m2 · g-1.随升温速率增高,挥发分逸出剧烈,残留的孔道越大或有部分产物堵塞住孔道,导致比表面积在逐渐降低(Ahmad et al., 2014).当恒温时间延长,生物质及热解的二次产物热解更为完全,使得孔结构充分发育,从而增加生物炭比表面积(Shaaban et al., 2014).

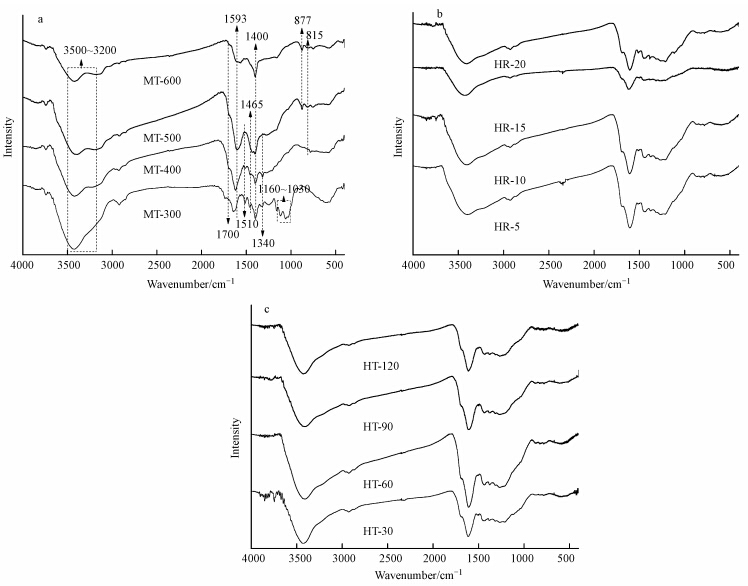

3.3 热解条件对生物炭表面官能团的影响由图 1a可知,热解终温由300 ℃增加至600 ℃,生物炭表面官能团数量在不断减少,且官能团的种类在发生变化,主要集中在1700~1000 cm-1处.MT-300在1700、1593、1510、1465、1400、1340和1160~1030 cm-1处的吸收峰分别指代碳酸性的C O、芳香性的C O、C C、C—H、—CH2、C C、C—O—C和—OCH3等官能团,随着热解终温的增加,1510、1465、1340和1160~1030 cm-1处的官能团在MT-500上急剧减弱甚至消失,同时,MT-500和MT-600在877和815 cm-1处出现了新的官能团(呋喃γ—CH2和芳香性的CH)(Zeng et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2013; Ding et al., 2014).此外,3500~3200 cm-1处的—OH官能团也随着热解终温的增加振幅在减弱(Wang et al., 2015).由图 1b和图 1c可见,升温速率和恒温时间对生物炭表面官能团基本无影响,这与许多研究结果基本一致(Angιn,2013; Cimò et al., 2014).

|

| 图 1 不同热解条件下制备生物炭的红外光谱(a.热解终温;b.升温速率;c.恒温时间) Fig. 1 Infrared spectra of biochar derived from different pyrolysis conditions(a.pyrolysis temperature; b.heating rate; c.holding time) |

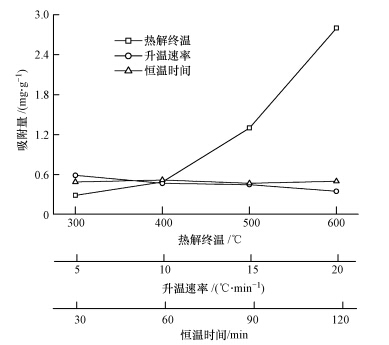

如图 2所示,当热解终温较低时,生物炭对NO3--N的吸附能力较低,如MT-300和MT-400对NO3--N的吸附量分别为0.29 mg · g-1和0.49 mg · g-1.而热解终温较高时,生物炭对NO3--N的吸附能力显著增加,MT-500和MT-600的吸附量分别增至1.3 mg · g-1和2.8 mg · g-1.且温度与NO3--N的吸附量呈指数递增关系(R2=0.99).有报道显示,在不同热解终温下制备的生物炭,随热解终温增加,NO3--N的吸附量增加(Kameyama et al., 2012; Yao et al., 2012).升温速率由5 ℃ · min-1增加至20 ℃ · min-1时,生物炭对NO3--N的吸附量由0.59 mg · g-1减少至0.35 mg · g-1,但变化不显著.随恒温时间的增加,生物炭对NO3--N的吸附先增大后减小再增大,且变化不明显(极差仅为0.05 mg · g-1).整体上,热解终温对生物炭NO3--N吸附影响最大,升温速率次之,恒温时间最小.

|

| 图 2 不同热解条件下制备生物炭对NO3--N吸附的影响 Fig. 2 Adsorption of NO3-N by biochar derived from different pyrolysis conditions |

本研究中,在不同热解终温和升温速率下获得的生物炭对NO3--N的吸附显示,比表面积和吸附量均表现较好的线性关系(R2=0.99和0.86),说明生物炭的比表面积对NO3--N吸附有一定贡献(Ohe et al., 2003).另外,热解终温越高,碱性官能团数量越多,表现出较高的NO3--N吸附量.同时,较低升温速率了有利于碱性官能团生成,在较低升温速率获得的生物炭也表现出较高的NO3--N吸附能力.由此表明,NO3--N的吸附与生物炭表面的官能团的数量和种类有一定关系,这与文献报道的一致(Kameyama et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2015). 此外,MT-400表面的能谱分析显示(表 4),生物炭的表面存在许多金属氧化物(如MgO、Al2O3和CaO等),NO3--N可以通过与金属氧化物配位的形式被吸附(Zhang et al., 2012).综上,生物炭对NO3-N的吸附性能与生物炭比表面积、表面碱性官能团和表面金属氧化物等多种特性有关.

| 表 4 能谱分析MT-400表面的物质 Table 4 Surface composition of MT-400 analyzed by energy disperse spectroscopy |

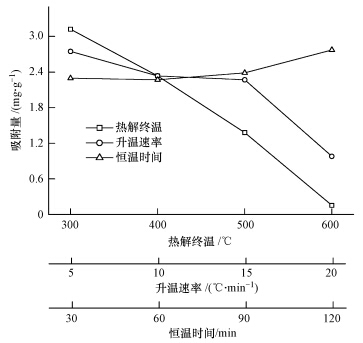

由图 3可见,NH+4-N吸附量随热解终温的增加呈下降趋势,MT-300、MT-400、MT-500和MT-600对NH+4-N的吸附量分别为3.12、2.33、1.38和0.15 mg · g-1.MT-300和MT-600对NH+4-N吸附量之间相差20倍以上,说明热解终温对生物炭的NH+4-N吸附性能影响显著(Hale et al., 2013; Hollister et al., 2013).随升温速率的增加,吸附量由2.75 mg · g-1降低至0.98 mg · g-1.而随恒温时间的增加,生物炭对NH+4-N的吸附表现一定的正向关系(NH+4-N吸附量为2.29~2.77 mg · g-1),但影响较小.综上,热解终温对NH+4-N吸附影响最大,升温速率次之,恒温时间最小.

|

| 图 3 不同热解条件制备生物炭对NH+4-N吸附的影响 Fig. 3 Adsorption of NH+4-N by biochar derived from different pyrolysis conditions |

NH+4-N为碱性阳离子,生物炭表面多为负电性.由此,有研究认为,生物炭可能通过静电吸附的方式对NH+4-N进行吸附(Yao et al., 2012).本研究中,MT-300、MT-400、MT-500和MT-600的表面Zeta电位随热解终温增加呈增加趋势(表 5),而对NH+4-N的吸附量却逐渐降低,说明静电吸附对NH+4-N的去除作用较小.另外,如表 3所示,随着热解终温和升温速率的增加,CEC降低(O/C降低),NH+4-N的吸附量也降低.同时,恒温时间对O/C明显无影响,对应的生物炭的NH+4-N吸附量也仅呈较小波动.因此,可以推断CEC是决定NH+4-N吸附性能的主要因素,这与文献报道的研究结果一致(Asada et al., 2002; Shaaban et al., 2014).

| 表 5 不同热解终温下制备生物炭的Zeta 电位 Table 5 The Zeta potential of biochar obtained at different pyrolysis temperature |

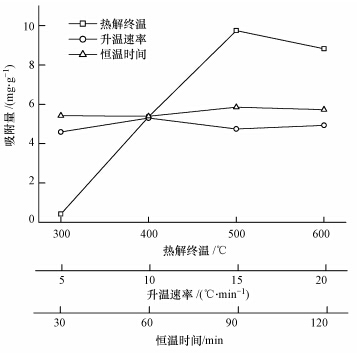

如图 4所示,当温度低于500 ℃时,生物炭对PO3-4-P的吸附量随热解终温的增加而增加,在500 ℃时达到最大(9.75 mg · g-1).此后温度增至600 ℃,PO3-4-P的吸附量有一定降低(8.83 mg · g-1).Zeng等(2013)在研究500、600和700 ℃下制备生物炭对PO3-4-P吸附性能时同样发现,生物炭对PO3-4-P吸附呈先增后降的结果.同时,Hollister等(2013)研究350 ℃和550 ℃下所制备的橡木生物炭时,随热解终温增加,PO3-4-P吸附量增大.不同升温速率和不同恒温时间下获得的生物炭对PO3-4-P吸附量分别为4.59~5.30 mg · g-1和5.39~5.73 mg · g-1,均呈一定的先增后降趋势,但变化幅度都较小.整体上,热解终温对生物炭PO3-4-P吸附影响较大,升温速率和恒温时间影响较小.

|

| 图 4 不同热解条件下制备生物炭对PO3-4-P吸附的影响 Fig. 4 Adsorption of PO3-4-P by biochar derived from different pyrolysis conditions |

有报道显示,PO3-4-P可通过与生物炭表面进行阴离子交换的方式进行吸附,而阴离子交换与碱性官能团密切相关(Hollister et al., 2013).本研究中,较高热解终温、较低升温速率和较长恒温时间均有利于碱性官能团的生成.但如图 4所示,PO3-4-P吸附量与热解条件之间并不存在单调的相关性,说明碱性官能团并非是决定PO3-4-P吸附的主要因素.另外,Yao等(2013)研究表明,生物炭表面等电点较高的氧化物(如MgO等)可通过表面沉积的方式实现对PO3-4-P的吸附.如表 4所示,生物炭表面存在MgO、Al2O3和CaO等金属氧化物.由此说明,金属氧化物与PO3-4-P之间的表面沉积作用也是生物炭吸附PO3-4-P的潜在机制(Wang et al., 2015).

4 结论(Conclusions)1)生物炭的产率均随热解终温、升温速率和恒温时间的增加而降低,其中,热解终温对生物炭产率影响最大,恒温时间次之,升温速率最小.

2)随热解终温、升温速率和恒温时间的增加,生物炭的pH和C含量增加,H和O含量降低.热解终温对生物炭的芳香性和疏水性影响较大,且高温生物炭的芳香性和疏水性较强,而升温速率和恒温时间的影响较小.热解终温、恒温时间的提高可增加生物炭的比表面积,提高升温速率不利于比表面积的增加.热解终温对生物炭表面官能团影响较大,升温速率和恒温时间基本无影响.

3)热解终温影响对生物炭对氮、磷的吸附性能影响较大,升温速率和恒温时间的影响较小.NO3--N的吸附性能与热解终温呈指数递增关系,且吸附性能与生物炭比表面积、碱性官能团和表面金属的氧化物有关.较低的热解终温获得的生物炭有利于NH+4-N的吸附,生物炭的阳离子交换量是控制NH+4-N吸附性能的主要机制.PO3-4-P吸附性能随着热解终温的增加在500 ℃达到最大,过高的热解终温不利吸附性能的改善,PO3-4-P的吸附性能和生物炭表面碱性官能团和表面金属氧化物有关.

| [1] | Abelson P H. 1970. Long-term efforts to clean the environment [J]. Science, 167(3921): 1081 |

| [2] | Ahmad M, Lee S S, Dou X M, et al. 2012. Effects of pyrolysis temperature on soybean stover- and peanut shell-derived biochar properties and TCE adsorption in water [J]. Bioresource Technology, 118: 536-544 |

| [3] | Ahmad M, Moon D H, Vithanage M, et al. 2014. Production and use of biochar from buffalo-weed (Ambrosia trifida L.) for trichloroethylene removal from water [J]. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology, 89(1): 150-157 |

| [4] | Angιn D. 2013. Effect of pyrolysis temperature and heating rate on biochar obtained from pyrolysis of safflower seed press cake [J]. Bioresource Technology, 128: 593-597 |

| [5] | Antal M J, Grønli M. 2003. The art, science, and technology of charcoal production [J]. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 42(8): 1619-1640 |

| [6] | Asada T, Ishihara S, Yamane T, et al. 2002. Science of bamboo charcoal: study on carbonizing temperature of bamboo charcoal and removal capability of harmful gases [J]. Journal of Health Science, 48(6): 473-479 |

| [7] | Cao X D, Harris W. 2010. Properties of dairy-manure-derived biochar pertinent to its potential use in remediation [J]. Bioresource Technology, 101(14): 5222-5228 |

| [8] | Chen B L, Chen Z M, Lv S F. 2011. A novel magnetic biochar efficiently sorbs organic pollutants and phosphate [J]. Bioresource Technology, 102(2): 716-723 |

| [9] | Chen D Y, Zheng Y, Zhu X F. 2013. In-depth investigation on the pyrolysis kinetics of raw biomass (Part I: Kinetic analysis for the drying and devolatilization stages) [J]. Bioresource Technology, 131: 40-46 |

| [10] | Chen D Y, Zhou J B, Zhang Q S. 2014. Effects of heating rate on slow pyrolysis behavior, kinetic parameters and products properties of moso bamboo [J]. Bioresource Technology, 169: 313-319 |

| [11] | Cheng C H, Lehmann J, Engelhard M H. 2008. Natural oxidation of black carbon in soils: Changes in molecular form and surface charge along a climosequence [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 72(6): 1598-1610 |

| [12] | Cimò G, Kucerik J, Berns A E, et al. 2014. Effect of heating time and temperature on the chemical characteristics of biochar from poultry manure [J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 62(8): 1912-1918 |

| [13] | Ding W C, Dong X L, Ime I M, et al. 2014. Pyrolytic temperatures impact lead sorption mechanisms by bagasse biochars [J]. Chemosphere, 105: 68-74 |

| [14] | Ding Y, Liu Y X, Wu W X, et al. 2010. Evaluation of biochar effects on nitrogen retention and leaching in multi-layered soil columns [J]. Water, Air, & Soil Pollut, 213(1/4): 47-55 |

| [15] | Hale S E, Alling V, Martinsen V, et al. 2013. The sorption and desorption of phosphate-P, ammonium-N and nitrate-N in cacao shell and corn cob biochars [J]. Chemosphere, 91(11): 1612-1619 |

| [16] | Haykiri-Acma H, Yaman S, Kucukbayrak S. 2006. Effect of heating rate on the pyrolysis yields of rapeseed [J]. Renewable Energy, 31(6): 803-810 |

| [17] | Hollister C C, Bisogni J J, Lehmann J. 2013. Ammonium, nitrate, and phosphate sorption to and solute leaching from biochars prepared from corn stover (Zea mays L.) and oak wood (Quercus spp.) [J]. Journal of Environmental Quality, 42(1): 137-144 |

| [18] | Inyang M, Gao B, Pullammanappallil P, et al. 2010. Biochar from anaerobically digested sugarcane bagasse [J]. Bioresource Technology, 101(22): 8868-8872 |

| [19] | Kameyama K, Miyamoto T, Shiono T, et al. 2012. Influence of sugarcane bagasse-derived biochar application on nitrate leaching in calcaric dark red soil [J]. Journal of Environmental Quality, 41(4): 1131-1137 |

| [20] | Kumar S, Masto R E, Ram L C, et al. 2013. Biochar preparation from Parthenium hysterophorus and its potential use in soil application [J]. Ecological Engineering, 55: 67-72 |

| [21] | Kuzyakov Y, Subbotina I, Chen H Q, et al. 2009. Black carbon decomposition and incorporation into soil microbial biomass estimated by 14C labeling [J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 41(2): 210-219 |

| [22] | Laird D, Fleming P, Wang B Q, et al. 2010. Biochar impact on nutrient leaching from a Midwestern agricultural soil [J]. Geoderma, 158(3/4): 436-442 |

| [23] | Lehmann J. 2007. A handful of carbon [J]. Nature, 447(7141): 143-144 |

| [24] | Lehmann J. 2009. Biological carbon sequestration must and can be a win-win approach [J]. Climatic Change, 97(3/4): 459-463 |

| [25] | Mizuta K, Matsumoto T, Hatate Y, et al. 2004. Removal of nitrate-nitrogen from drinking water using bamboo powder charcoal [J]. Bioresource Technology, 95(3): 255-257 |

| [26] | Mukherjee A, Zimmerman A R, Harris W. 2011. Surface chemistry variations among a series of laboratory-produced biochars [J]. Geoderma, 163(3/4): 247-255 |

| [27] | Ohe K, Nagae Y, Nakamura S, et al. 2003. Removal of Nitrate Anion by Carbonaceous Materials Prepared from Bamboo and Coconut Shell [J]. Journal of Chemical Engineering of Japan, 36(4): 511-515. |

| [28] | Peng X, Ye L L, Wang C H, et al. 2011. Temperature- and duration-dependent rice straw-derived biochar: characteristics and its effects on soil properties of an Ultisol in southern China [J]. Soil and Tillage Research, 112(2): 159-166 |

| [29] | Recari J, Berrueco C, Abelló S, et al. 2014. Effect of temperature and pressure on characteristics and reactivity of biomass-derived chars [J]. Bioresource Technology, 170: 204-210 |

| [30] | Richardson K. 1997. Harmful or exceptional phytoplankton blooms in the marine ecosystem [J]. Advances in marine biology, 31: 301-385 |

| [31] | Schmidt M W I, Noack A G. 2000. Black carbon in soils and sediments: Analysis, distribution, implications, and current challenges [J]. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 14(3): 777-793 |

| [32] | Shaaban A, Se S M, Dimin M F, et al. 2014. Influence of heating temperature and holding time on biochars derived from rubber wood sawdust via slow pyrolysis [J]. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis, 107: 31-39 |

| [33] | Singh B, Singh B P, Cowie A L. 2010. Characterisation and evaluation of biochars for their application as a soil amendment [J]. Australian Journal of Soil Research, 48(7): 516-525 |

| [34] | Wang Z H, Guo H Y, Shen F, et al. 2015. Biochar produced from oak sawdust by Lanthanum (La)-involved pyrolysis for adsorption of ammonium (NH4+), nitrate (NO3-), and phosphate (PO43-) [J]. Chemosphere, 119: 646-653 |

| [35] | Yaman S. 2004. Pyrolysis of biomass to produce fuels and chemical feedstocks [J]. Energy Conversion and Management, 45(5): 651-671 |

| [36] | Yao Y, Gao B, Chen J J, et al. 2013. Engineered biochar reclaiming phosphate from aqueous solutions: Mechanisms and potential application as a slow-release fertilizer [J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 47(15): 8700-8708 |

| [37] | Yao Y, Gao B, Fang J E, et al. 2014. Characterization and environmental applications of clay-biochar composites [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 242: 136-143 |

| [38] | Yao Y, Gao B, Zhang M, et al. 2012. Effect of biochar amendment on sorption and leaching of nitrate, ammonium, and phosphate in a sandy soil [J]. Chemosphere, 89(11): 1467-1471 |

| [39] | Zeng Z, Zhang S D, Li T Q, et al. 2013. Sorption of ammonium and phosphate from aqueous solution by biochar derived from phytoremediation plants [J]. Journal of Zhejiang University Science B, 14(12): 1152-1161 |

| [40] | Zhang M, Gao B, Yao Y, et al. 2012. Synthesis of porous MgO-biochar nanocomposites for removal of phosphate and nitrate from aqueous solutions [J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 210: 26-32 |

| [41] | Zhao L, Cao X D, Mašek O, et al. 2013. Heterogeneity of biochar properties as a function of feedstock sources and production temperatures [J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 256-257: 1-9 |

| [42] | Zhou Y M, Gao B, Zimmerman A R, et al. 2014. Biochar-supported zerovalent iron for removal of various contaminants from aqueous solutions [J]. Bioresource Technology, 152: 538-542 |

2015, Vol. 35

2015, Vol. 35