2. 中国地震局地壳应力研究所, 北京 100081

2. Institute of Crustal Dynamics, China Earthquake Administration, Beijing 100081, China

地震从孕育到成核直至断层破裂以及震后调整的整个动力学过程,摩擦本构关系始终起着决定性的作用(Dieterich, 1994; Olsen et al., 1997; Scholz, 2002; Parsons, 2005; Lapusta, 2009; Sone and Shimamoto, 2009; Bizzarri, 2011; Zhu, 2018).摩擦关系不仅控制着地震的成核位置、发生时间及震级大小,还控制着破裂的方式、破裂的传播速度及方向以及余震发生的数目及其衰减规律(Dieterich, 1994; Gomberg et al., 2005; Helmstetter and Shaw, 2009; Kame et al., 2013)等.从力学上来看,摩擦力是阻止断层两盘滑移的力.摩擦系数越大,阻力就越大,断层就越不容易发生滑动.只有当剪应力克服了断层面上的摩擦力时,断层才能发生错动,产生地震.

关于摩擦的系统研究可以追溯到15世纪意大利的艺术家达芬奇,他发现了两个主要的摩擦定律,并进一步观察到较光滑的表面摩擦较小.之后,阿蒙顿以及库仑等人对摩擦关系进行了定量研究, 特别是库仑摩擦定律的提出(Scholz, 2002).Byerlee (1978)通过实验给出了不同深度岩石发生破裂的摩擦系数(Byerlee定律).但这些定律中的摩擦系数是常数,它不随滑移速度或滑移量的变化而变化,因此无法解释地震时断层出现的不稳定摩擦的黏滑现象.为此,人们开展了许多岩石力学实验来探索摩擦定律.Scholz等(1972)以及Dieterich(1978)通过实验揭示出,速度相关的摩擦关系中,摩擦系数随速度增大而减小,即所谓的速度弱化,能够导致不稳定滑动.Ida(1972)及Palmer和Rice(1973)发现了另外一种摩擦关系——滑移弱化的摩擦定律,即摩擦系数随滑移量增大而减小,其通常被用来研究不稳定滑动.最简单的情况就是摩擦系数随滑移线性衰减直至达到特征滑动距离,在此后的滑动过程中,摩擦系数保持不变.

实际上,摩擦过程非常复杂, 不是单纯的速度或滑移相依的关系.为此,Madariaga和Cochard(1996)、Madariaga等(1998)、Aagaard等(2001)给出了滑移弱化与速率弱化相结合的综合模型,来模拟实际的地震破裂行为.在这种情况下,摩擦关系不能用一个简单的数学公式来表达,实际计算中摩擦系数取速度弱化和滑移弱化摩擦关系中的最大者(Aagaard et al., 2001).此外在摩擦实验中,还发现摩擦系数随滑动速度发生“跳跃”的现象(Dieterich, 1979, 1981; Ruina, 1983),即当滑移速度不变时,摩擦系数也不变;可是,一旦滑移速度突然增大,摩擦系数也同时突然增大.为量化这一特征,引入了“状态”变量的概念,将摩擦关系用更为普通的数学公式来表达,即人们熟知的速率-状态相依的Dieterich-Ruita摩擦定律(Dieterich, 1978, 1979; Johnson, 1981; Ruina, 1983; Scholz, 1998; Marone, 1998).该定律中,摩擦不仅与当前的滑动速率及状态变量有关,还与接触面的演化历史有关.不仅如此,实际地震时,摩擦关系还与位置相关,在地震断面上显示出强烈的空间不均匀性(Kaneko et al., 2010;Barbot et al., 2012),在断层的有些区域显示出速度弱化,而在另一些断层面上表现为速度强化.理论上来说,只要摩擦关系在形式上是不稳定的(如:滑移弱化或速率弱化),都可以用来模拟地震的成核及断层的破裂过程,但是实验室里总结出来的摩擦关系(如:Dieterich-Ruita关系)是在低滑移速率(10-7~1 mm·s-1)的实验环境里总结的结果,而实际大地震的滑移速率一般在~1 m·s-1的量级(Heaton, 1990; Somerville et al., 1999; Aagaard et al., 2001).那么实验室里的摩擦结果能否外推应用到天然地震的模拟中?日本Toshihiko Shimamoto一直从事断层力学及摩擦的实验研究,制作了高速摩擦的实验装置(可达2.1 m·s-1).近年来多个摩擦实验结果发现:在低速情况下实验室里得出的摩擦定律在高速摩擦时基本可用(Mizoguchi et al., 2007; Sone and Shimamoto, 2009; Yao et al., 2013),同时还发现了一些新的现象,如:从加速到减速的滑移过程中,断层要经历强化、弱化及愈合三个阶段.这个过程可以用低速滑移时的速率-状态相关的摩擦关系外推得到,但物理机制不同(Sone and Shimamoto, 2009).

计算技术及计算设备的迅速发展,使得我们有可能利用科学计算方法模拟大地震的破裂过程(Oglesby et al., 2008; Bizzarri et al., 2010; Ando and Kaneko, 2018; 袁杰和朱守彪, 2017; 朱守彪和袁杰, 2016; 朱守彪等, 2017; Zhu, 2018;Ulrich et al., 2019),从而加深我们对地震震源过程的认识.但目前对地震破裂的模拟中,不同的作者往往运用不同的摩擦本构关系(Ohnaka and Yamashita, 1989; Fukuyama and Madariaga, 1998; Douilly et al., 2015; Dunham et al., 2011; Gabriel et al., 2012; Zhu, 2018).尽管都能在一定的程度上模拟断层破裂的力学行为,但利用不同的摩擦关系模拟结果显然是不同的.可是,不同的摩擦本构关系究竟对断层破裂过程的模拟结果有什么样的影响?哪种类型的摩擦关系最能够代表实际天然地震破裂时的摩擦属性?这个问题至今未见相关文献进行系统地、定量地介绍.为此,本文拟对目前数值模拟中,应用最为广泛的4种典型摩擦本构关系,分别运用有限单元方法模拟断层发生自发破裂的动力学行为特征,以此来研究不同的摩擦关系对地震破裂动力学过程的影响.

1 四种典型摩擦本构关系的数学表达式如上所述,摩擦本构关系有多种形式,其中使用最为广泛的有4种,分别是:(1)滑移弱化摩擦关系, (2)速率弱化摩擦关系, (3)速率-状态相关的摩擦关系中的老化定律, (4)速率-状态相关的摩擦关系中的滑动定律.下面对这4种典型的摩擦关系的数学表示形式及其物理意义作简单的介绍.

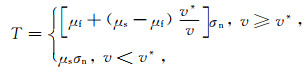

1.1 滑移弱化摩擦关系滑移弱化的摩擦关系是一种极为广泛使用的摩擦关系(Slip Weakening law, 下文简称为SW摩擦定律),摩擦系数随着滑移的变化有线性与非线性之分(Bizzarri, 2011).其中,线性滑移弱化摩擦关系的数学表达式如下(Ida, 1972; Andrews, 1976a, 1976b; Ohnaka and Yamashita, 1989):

|

(1) |

式中μs,μf分别为最大静摩擦系数和滑动摩擦系数,u为接触断层两盘之间的相对滑动量(即断层面上的位错量),σn为断层面上的有效正应力,d0为特征滑动量,表示从静摩擦系数下降到动摩擦系数所需要的滑动距离.公式(1)表明,处于闭锁状态的断层,当断层面上的剪切应力低于最大静摩擦力时,断层仍保持闭锁状态;但若断层两侧之间出现滑动,摩擦力就随着位错的增大而线性减小;一旦位错大小达到特征滑动量时,摩擦系数就减小为滑动摩擦系数,此时摩擦力最小,断层出现持续的滑动.

1.2 速率弱化摩擦关系在岩石物理实验中,前人发现岩石在高速(>1 m·s-1)滑移摩擦时出现了明显的速率弱化行为(Tsutsumi and Shimamoto, 1997; Prakash, 1998; Goldsby and Tullis, 2002; Hirose and Shimamoto, 2005; Tullis and Goldsby, 2003),即摩擦系数随着断层位错滑动的速率(下文简称滑动速率)的增大而减小,因此提出了多种不同形式的速率弱化的摩擦关系(Rate Weakening law, 下文简称为RW摩擦定律),这些形式也被成功地应用于地震破裂过程的数值模拟中(Cochard and Madariaga, 1994, 1996; Fukuyama and Madariaga, 1998; Beeler et al., 1996; Rojas et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2013).本文引入的速率弱化摩擦关系类似于SW摩擦关系的形式,具体数学表达式如下(Beeler et al., 2008):

|

(2) |

其中v*为参考滑动速率,Beeler通过实验确定了该值的范围为0.1~0.2 m·s-1, 当滑动速率v逐渐增大超过v*,摩擦系数迅速下降到μf;当v减小时,摩擦系数重新增大,摩擦系数增大可能迫使地震破裂自动停止,因此RW摩擦关系可以实现断层的自我愈合(Cochard and Madariaga, 1994, 1996; 袁杰和朱守彪, 2014).

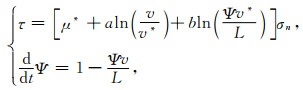

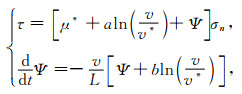

1.3 基于速率状态的摩擦关系-老化定律基于速率状态的摩擦关系中的老化定律(Rate- and State- dependent model: Aging law, 下文简称为RS-al摩擦定律)最早由Dieterich(1978)提出,并在岩石物理实验中得到验证(Mair and Marone, 1999),摩擦系数由滑动速率v和状态量Ψ共同控制,它的基本形式为

|

(3) |

其中L称为特征滑动量,但与SW摩擦关系中d0的物理意义不同,d0表示摩擦系数从μs下降到μf需要的滑动量,而L表示控制状态量演化速率的特征长度.v为滑动速率,v*和μ*分别为参考滑动速率和参考摩擦系数,τ为断层面上的剪应力.当v较小且为定值时,状态量Ψ也会自行演化,并随时间增长,因此该定律被称作老化定律或慢度定律.假设初始状态量为Ψ0,初始时间为0,(3)式中的常微分方程的解析解(Kanamori and Brodsky, 2001)为

|

(4) |

从(4)式可以看出,当滑动速率较小,出现Ψ0<L/v时,Ψ与时间正相关,(3)式中的bln(Ψv*/L)项亦随时间的增长而增大,这样摩擦阻力也随着增大,这时需要更大的剪切应力才能使得断层滑动,所以该过程为速率强化过程;反之,随着滑动速率v的逐渐变大,当Ψ0>L/v时,Ψ将随时间而减小,导致bln(Ψv*/L)越来越小,摩擦系数也随着时间而减小,所以这一过程为速率弱化.本研究中,为将问题简化,断层破裂过程的模拟只考虑v≥v*的情况,初始状态量Ψ0=L/vinit,并令初始滑动速率vinit=v*.

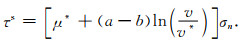

特别是当

|

(5) |

再将(5)式代入公式(3)中,可以得到稳态情况下的摩擦力为

|

(6) |

由(6)式可知,若(a-b) < 0,摩擦系数随着速率的增大而减小,为速率弱化状态;反之若(a-b)>0,摩擦系数随着速率的增大而增大,为速率强化过程.断层上的速度强化区域通常会阻止断层进一步破裂(Scholz,1998).通常情况下,a和b的大小由断层面上的岩石物理属性决定,速度强化区通常存在于蠕滑运动状态的断层,或者是在较厚的松散沉积层中(Marone et al., 1991).

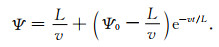

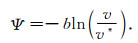

1.4 基于速率状态的摩擦关系-滑动定律速率-状态的摩擦关系中的滑动定律(Rate- and State- dependent model: Slip law, 下文简称为RS-sl摩擦定律)是由Ruina(1983)对Dieterich(1978)摩擦关系的进一步修改,因此又被称作Ruina-Dieterich定律.它的基本形式为

|

(7) |

式中各参数的物理意义与老化定律中的一致,但是此时的状态量Ψ不再具有物理量纲,没有具体的物理意义(Bizzarri, 2011).这里假设初始状态变量和初始时间均为0,其解为(何昌荣,1999):

|

(8) |

(7) 和(8)式中的参数a,b以及L对于摩擦系数的影响与RS-al摩擦关系基本一致,有多位作者对此进行了定量分析(Bizzarri and Cocco, 2003; Bizzarri et al., 2010a; 张慧茜等, 2014),这里不再累述.

当

|

(9) |

将(9)式代入(7)式,可以得到稳态情况下的摩擦力与(6)式的完全相同,(a-b)的物理意义也与RS-al摩擦关系中的相同.

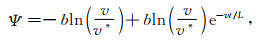

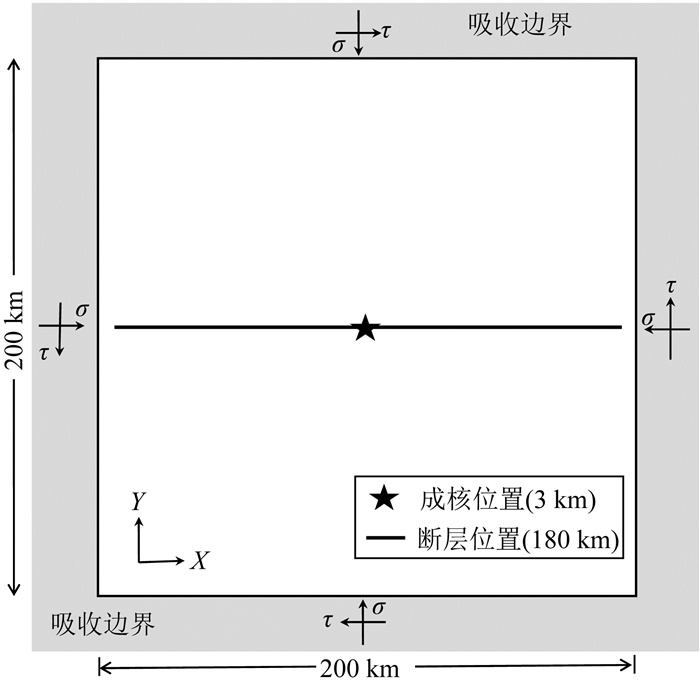

2 不同摩擦关系控制下的断层自发破裂过程的有限元法模拟 2.1 有限元方法及其模型参数设置为研究摩擦本构关系对断层自发破裂动力学过程的影响,建立如图 1所示的二维有限元模型.模型几何为200 km×200 km;模型中央的黑色直线代表断层,长度为180 km;五角星表示成核中心,长度为3 km.为提高计算效率和计算精度,断层附近的网格密度很高,单元长度为200 m;随着离断层距离越远,网格密度逐渐下降,在模型边界上单元长度为800 m.对模型进行三角形网格剖分,整个模型的有限元网格节点数为80473,单元数为158830.模型中介质简化为各向同性均匀的线弹性材料,初始应力场视为均匀(见图 1).在模型周边设置吸收边界(具体计算时是用无限单元来实施),以消除地震波在边界上的反射所造成的数据污染.本文的模拟计算是利用商业有限元软件ABAQUS进行的.其中,摩擦本构关系是通过ABAQUS软件中自带的Fortran-Vfric子程序来实现(袁杰和朱守彪,2014;朱守彪等,2017),计算时间步长为0.0001 s,同时使用数值方法(龙格-库塔5阶求解公式)(Stoer and Bulirsch, 2013)求解方程(3)和(7)中的微分方程(通过修改Vfric子程序代码来实现).

|

图 1 有限元模型的几何以及初始、边界条件示意图.其中σ为初始正应力,τ为初始剪应力 中间黑色直线为断层,五角星为成核位置,模型四周为吸收边界. Fig. 1 Sketch map of model geometry, the initial and boundary conditions. σ for the initial normal stress and τ for initial shear stress The black straight line in the middle represents the fault, the star stands for nucleation site, and the model is surrounded by absorbing boundary. |

初始应力状态对断层的自发破裂过程起着重要作用(Fukuyama and Olsen, 2002; Duan, 2010; Kammer, et al., 2018),通常利用地震强度参数S值来判断所施加的应力是否能够满足产生超剪切破裂的条件(Andrews, 1985;Dunham, 2007).S值最先由Hamano (1974)定义(Das and Aki, 1977; Andrews, 1985;Dunham, 2007;Liu et al., 2014),具体数学表达式如下:

|

(10) |

式中τu, τf, τ0分别代表上屈服应力(upper yield stress,τu=μsσn)、剩余剪应力(residual shear stress,τf=μfσn)以及初始剪应力.理论上,初始应力越大(越接近于峰值剪应力),S值就越小,断层越容易产生不稳定滑动,相应地断层强度就越低(weak fault),否则断层强度就越高(strong fault),就不容易产生破裂(Liu et al., 2014).对于二维模型,S等于1.77为临界值(Scrit=1.77),低于此值,断层就有可能产生超剪切破裂(Andrews, 1985;Dunham, 2007).由于本文为二维模型,所以下面选择两种S值(即S=1.79>Scrit, 以及S=0.9 < Scrit)的情况, 来分别考察不同的摩擦本构关系对断层自发破裂动力学过程的影响.

另外,地震成核过程对断层自发破裂行为有一定的影响(Bizzarri, 2010c; 朱守彪等, 2017;Zhu, 2018).本文破裂成核使用线性-时间弱化关系(Bizzarri, 2010c),具体形式为

|

(11) |

式中tforce=D/vforce,D为成核区的半径(1.5 km),vforce为成核区破裂速度, 设定为2.4 km·s-1,tforce表示破裂以vforce速度传播距离D所需要的时间,t0=0.1 s, 为特征时间,表征破裂传播到该位置时,摩擦系数将在t0时间内从最大静摩擦系数下降到滑动摩擦系数.考虑到不同成核方法对破裂行为可能会造成影响,因此本文的所有模型中所使用的成核方式均相同.

此外,为了定量考察不同的摩擦关系下断层自发破裂过程的差异,通常需要保持断层破裂过程中破裂能(fracture energy)相同.破裂能是破裂过程中破裂前峰由于产生了新的破裂所需要消耗的能量,单位面积上的破裂能称为破裂能密度(单位J·m-2), 具体数学形式可以表示为(Palmer and Rice, 1973):

|

(12) |

式中d为特征滑移量,τ为剪应力,τres为剩余剪应力(其值为滑动摩擦力).对于滑移弱化的摩擦关系,根据最大剪应力和滑动摩擦力以及特征滑移量,就可以直接求得破裂能;而速率-状态相依的摩擦关系中的最大剪应力和滑动摩擦力是对破裂过程的求解结果,为此Cocco和Bazzari(2002)、Bizzarri和Cocco(2003)、Tinti等(2005)等将求解得到的最大剪应力定义为等效最大剪应力τueq, 将最小剪应力定义为等效滑动摩擦力τfeq,将τfeq对应的滑动量定义为等效特征滑动量d0eq,然后根据公式(12)来计算破裂能.为了使得不同的摩擦关系具有相同的破裂能,我们首先利用速率-状态相依的摩擦关系进行破裂过程的模拟,然后将模拟得到的τueq和τfeq作为滑移弱化的摩擦关系的输入,并调整合适的d0eq (具体大小请见表 1和表 2),从而可以使得在利用不同的摩擦关系模拟断层破裂过程中都具有相同的破裂能.

|

|

表 1 S=1.79时的模型参数 Table 1 Model parameters used in simulation when S=1.79 |

|

|

表 2 S=0.9时的模型参数 Table 2 Model parameters used in simulation when S=0.9 |

图 2显示了不同摩擦关系对应不同S值时的滑移弱化曲线,其中横坐标为断层位错滑动量,纵坐标表示断层面上的剪应力.破裂能密度可以由不同的滑移弱化曲线数值积分得到.由图可见,在两种不同S值的情况下,SW, RS-al, RS-sl摩擦关系的破裂能密度基本相同,而RW摩擦关系滑移弱化曲线衰减迅速,只能保持较小的破裂能密度.RS-sl摩擦关系的滑移弱化曲线呈现先陡后缓的非线性衰减,而其余摩擦关系基本都呈线性衰减.由于SW, RS-al, RS-sl摩擦关系的破裂能密度和S值都相等,因此破裂行为的差异完全来源于摩擦关系本身;而RW摩擦关系的破裂能密度不一致,它的破裂行为可能会受到破裂能密度的影响.

|

图 2 不同S值时,不同摩擦关系的滑移弱化曲线, 其中横坐标表示滑动距离,纵坐标为剪切应力 (a)当S=1.79时; (b)当S=0.9时. Fig. 2 Slip-weakening curve with different friction laws in different S values, and the abscissa denotes slip and the ordinate shear stress (a) When S=1.79; (b) When S=0.9. |

需要指出的是,图 2a中RW曲线在3.3 s处突然下降后又上升,该现象是由于在利用RW摩擦关系的破裂过程模拟中,计算质点从运动到静止的过程中稳定性较差所引起的数值震荡.Cochard和Madariaga (1994)曾对这种不稳定性做了具体的解释.图 2b中RS-al摩擦关系的滑移弱化曲线(红色表示)在滑动初期出现了一个明显的圆弧,在较小滑动量范围内,剪应力随着滑移量的增大而增大,随后剪应力随着滑移量的增大而减小,这说明了RS-al摩擦关系存在滑移弱化和滑移强化两个阶段(RS-sl摩擦关系也存在这种现象,但是由于弧度较小不明显);而SW摩擦关系自开始滑动后剪应力一直下降(绿色曲线表示),说明它只存在滑移弱化特征.

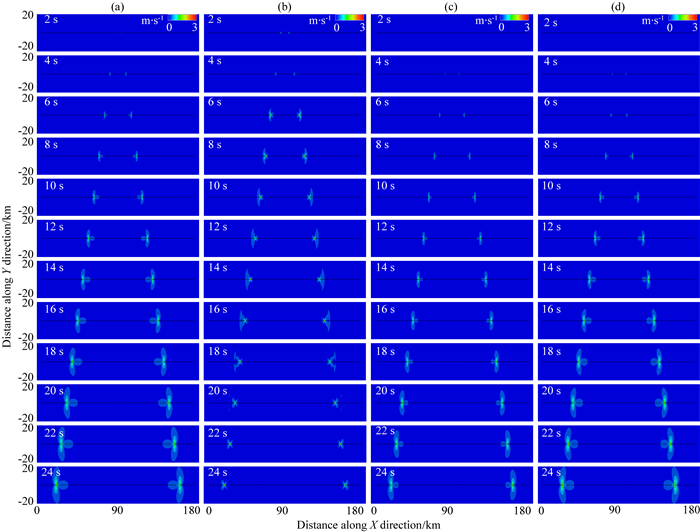

2.2 不同摩擦关系控制下的断层自发破裂过程的动力学特征 2.2.1 不同摩擦关系模拟结果的共同特征基于当S=1.79时的模型参数(见表 1),运用有限单元方法分别计算了4种不同类型的摩擦本构关系下,断层产生自发破裂随时间的演化过程.图 3给出了时间从0到24 s不同时刻断层破裂过程演化的快照(质点振动速度等值线云图).图中第一列到第四列分别表示滑移弱化摩擦关系、速率弱化摩擦关系、以及速率-状态相关的摩擦关系中的老化定律和滑动定律所对应的破裂过程的模拟结果.由图可见,尽管摩擦本构关系不同,但每一种模拟给出的断层自发破裂过程的形态几乎是一样的:破裂从断层中心成核后,自发地向断层两侧对称传播,并且质点振动的速度都是越来越大,但破裂传播速度几乎都相同,大约为3.12 km·s-1,实际上都为亚剪切波速度(表 1中剪切波速度为3464 m·s-1).

|

图 3 高S值条件下(S=1.79)不同摩擦关系模拟的断层自发破裂过程快照(质点振动速度) (a) SW摩擦关系;(b) RW摩擦关系;(c) RS-al摩擦关系;(d) RS-sl摩擦关系. Fig. 3 Snapshots of dynamic rupture propagation at different times under high seismic S ratio of 1.79 (particle vibration velocity) (a) Slip weakening law; (b) Rate weakening law; (c) Rate- and State- dependent model: Aging law; (d) Rate- and State- dependent model: Slip law. |

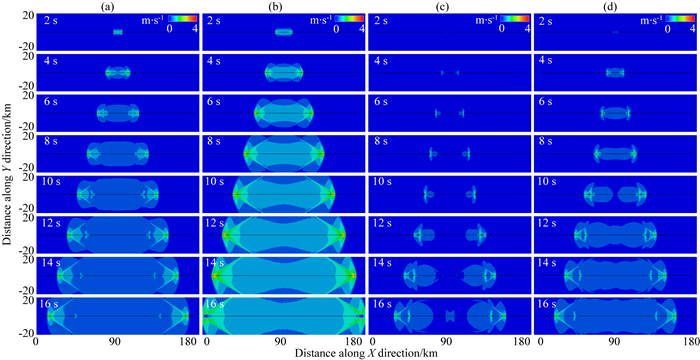

同样,利用有限元方法计算了当S=0.9时(模型参数见表 2),4种不同的摩擦本构关系对应的断层自发破裂传播过程.图 4显示了0~16 s不同时刻破裂的快照.与S=1.79时的情况相比(可与图 3比较),显著不同的是:这4种不同摩擦关系模拟给出的结果都是,当破裂传播了一定距离后都产生了马赫波(图中可见到马赫锥).说明此时不同的摩擦关系所模拟的破裂过程都产生了超剪切破裂(破裂传播速度超过了剪切波的速度).经计算可知,此时的破裂传播速度为5.95 km·s-1,该速度值确实大于介质的剪切波速度(其值为3464 m·s-1).

|

图 4 低S值条件下(S=0.9)不同摩擦关系模拟的断层自发破裂过程快照(质点振动速度) (a) SW摩擦关系;(b) RW摩擦关系;(c) RS-al摩擦关系;(d) RS-sl摩擦关系. Fig. 4 Snapshots of dynamic rupture propagation at different times under low seismic S ratio of 0.9 (particle vibration velocity) (a) Slip weakening law; (b) Rate weakening law; (c) Rate- and State- dependent model: Aging law; (d) Rate- and State- dependent model: Slip law. |

图 5进一步展示了在以上两种S值情况下,利用不同摩擦关系模拟给出的断层位错滑动速率的时空演化图(其中横坐标表示断层到成核中心的距离,纵坐标表示破裂发生的时刻).图 5a, e中的白色斜线分别对应瑞雷波(vr)、S波(vs)、P波(vp)的速度.由图可见,模拟得到的滑动速率云图都呈斜线分布,斜率的大小则代表了破裂速度的倒数.由图不难看出,在S=1.79时的所有情况下(见图 5a—d),破裂速度都低于剪切波速度,因此都为亚剪切破裂.但当S=0.9时,图 5e—h中的破裂首先产生亚剪切破裂,传播一段距离后出现了超剪切破裂.经计算可知, 不同摩擦关系在不同的情况下,亚剪切破裂速度都接近瑞雷波速度(约3.12 km·s-1),而超剪切破裂速度都接近P波速度(约5.95 km·s-1).由此可见,模拟给出的不同类型摩擦关系所获得的断层破裂无论是亚剪切破裂还是超剪切破裂,其速度大小基本上为常数,与摩擦本构关系的类型无关.

|

图 5 不同摩擦关系下,断层面上质点位错滑动速率的时空演化图,其中横坐标为断层面的点到成核中心的距离,纵坐标为时间 (a)—(d) (第一排图)为S=1.79;(e)—(f) (第二排图)为S=0.9的情况. (a, e) SW摩擦关系; (b, f) RW摩擦关系; (c, g) RS-al摩擦关系; (d, h) RS-al摩擦关系. Fig. 5 Spatio-temporal evolution of the slip rate with four different friction laws for a particle in fault plane. The abscissa denotes the distance from the point on the fault plane to the nucleation center, and the ordinate denotes the time (a)—(d) (the first row) when S=1.79; (e)—(f) (the second row) when S=0.9.(a, e) Slip weakening law; (b, f) Rate weakening law; (c, g) Rate- and State- dependent model: Aging law; (d, h) Rate- and State- dependent model: slip law. |

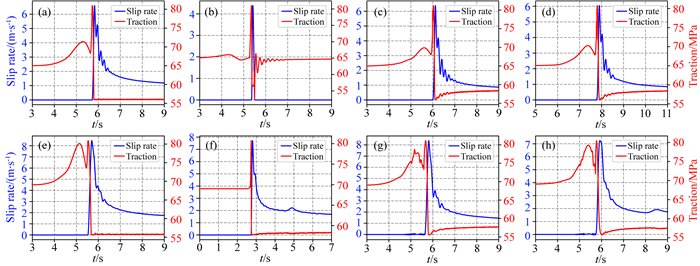

图 6给出了两种S值情况下,通过不同摩擦关系模拟得到的断层面上距离成核中心15 km处质点的滑动速率和剪应力随时间的变化曲线.由图可见,不同摩擦关系的滑动速率和剪应力变化趋势总体上是一致的,都是首先增大,到达峰值后迅速下降,且不同的摩擦关系模拟给出的在S=0.9情况下的滑动速率峰值(图 6e—f)总体上都分别大于S=1.79时(图 6a—d)所对应的滑动速率峰值.值得注意的是,在所有的亚剪切破裂的剪应力变化曲线(图 6a—d, e, g, h)中,在最大剪应力峰值来临之前都出现了一个相对小的峰值, 该峰值的传播速度与S波速度相同, 因此称之为S波应力峰值(Andrews, 1976b),这是亚剪切破裂普遍存在的现象.此外,图 6还显示,S=0.9时所对应的S波应力峰值幅度明显大于S=1.79时的情况.

|

图 6 不同摩擦关系下,距离成核中心15 km处质点的滑动速率和剪应力随时间变化图 其中蓝色曲线代表滑动速率,红色曲线代表剪应力. (a)—(d) (第一排图)为S=1.79时的变化曲线;(e)—(f) (第二排图)为S=0.9时的情况. (a, e) SW摩擦关系; (b, f) RW摩擦关系; (c, g) RS-al摩擦关系; (d, h) RS-al摩擦关系. Fig. 6 Time history of the slip velocity and shear stress with four different friction laws on the particle with 15 km away from the nucleation zone The blue curve denotes the slip rate and the red curve the shear stress, respectively. (a)—(d) (the first row) when S=1.79; (e)—(f) (the second row) when S=0.9.(a, e) Slip weakening law; (b, f) Rate weakening law; (c, g) Rate- and State- dependent model: Aging law; (d, h) Rate- and State- dependent model: slip law. |

根据2.2.1节的讨论可知,在相同的S值条件下,不同摩擦关系的破裂行为总体上具有一致性,即高S值产生亚剪切破裂,而低S值可以产生超剪切破裂,且破裂速度基本相同;断层面上剪应力和位错滑动速率随时间的变化趋势也基本一致.但是,模拟结果还显示,不同的摩擦关系模拟给出的破裂行为也存在明显的差异.

(1) RW摩擦关系可以模拟脉冲型破裂,而其余摩擦关系只能模拟裂纹型破裂

根据破裂面上质点振动时间与整个破裂过程持续时间之间的关系,可将破裂划分为裂纹型破裂(crack-like)和脉冲型破裂(pulse-like).裂纹型破裂其破裂面上各点位错滑移的持续时间与整个破裂过程的持续时间相当,即破裂不会愈合;而脉冲型破裂中各点位错滑移的持续时间比整个破裂持续时间短得多,所以该类型的破裂认为是可以自行愈合的.图 5中,在S=1.79的情况下,只有图 5b显示的RW摩擦关系给出破裂面上任意点的滑动速率仅在破裂前锋到来时滑移速率不为0,破裂前锋过后,其他所有时刻滑移速率皆为0,说明破裂后断层很快就愈合,因此属于脉冲型破裂.但当S=0.9时,无论什么摩擦本构关系模拟给出的破裂中,破裂前峰后的滑移速度都不降低为0,即破裂不能愈合,属于裂纹型破裂.图 5清晰地显示,除了图 5b外,所有情况下,一旦破裂开始,就不会停下来,图中斜线上方为蓝色(质点滑移速度幅值约为2 m·s-1).图 6中显示的距离成核中心15 km处质点的滑动速率随着时间的变化图像,进一步说明了只有速率弱化的摩擦本构关系可以模拟脉冲型破裂(图 6b清晰地展示,蓝色线条代表的位错速度在破裂过后降为0,说明断层已经愈合).而图 6中其他所有情况的断层滑移速率在达到峰值后皆不随着时间的流逝而降为0.该计算结果与前人的结果(Cochard and Madariaga, 1994, 1996; 袁杰和朱守彪, 2014)有一致性.

(2) 不同摩擦关系模拟给出的由亚剪切破裂转换为超剪切破裂的转换长度不同

图 5e—h中清晰地显示,破裂速度出现了分叉点,即出现了超剪切破裂的现象.同时,由图可见不同的摩擦关系其分叉点到成核中心(坐标原点)的距离是不同的,即不同的摩擦关系模拟给出的由亚剪切破裂转换为超剪切破裂需要的转换长度是不同的.根据图 5e—h,可以看出SW,RW,RS-al,RS-sl摩擦关系模拟给出的超剪切破裂转换长度分别约为:24 km, 1.5 km, 30 km, 20 km.可见,不同的摩擦关系给出的超剪切破裂转换长度相差较大.特别是,速率弱化的摩擦关系在高应力水平时(S=0.9)几乎可以直接产生超剪切破裂(Liu et al., 2014),而不需要转换距离(考虑到文中模型的成核区半径为1.5 km).

(3) 不同摩擦关系给出的断层初始破裂传播速度不同

由图 5可以看出,黄色亮线的轨迹在破裂开始阶段是向上弯曲的,说明由黄色亮线给出的破裂传播速度在破裂起始阶段比较低.不同的摩擦关系在破裂早期的破裂传播速度都明显低于或等于亚剪切破裂速度,但是经过一段时间以后,破裂速度趋于稳定,其大小低于介质的剪切波速度.特别地,由图 6可知,对于断层面上的同一个质点(距离成核中心15 km),不同摩擦关系模拟给出的破裂到时明显不同.图中显示,当S=1.79时,自左向右(图 6a—d), 在距离成核区15 km处破裂前峰的到时分别约为:5.7 s, 5.4 s, 6.0 s, 7.9 s.因此,可以计算出在不同摩擦关系情况下的破裂传播平均速度,其大小分别为:2.6 km·s-1, 2.8 km·s-1, 2, 4 km·s-1, 1.9 km·s-1.这充分证明在破裂起始阶段不同的摩擦本构关系模拟给出的破裂传播速度差异较大.同样,在S=0.9时也有类似的结果.值得特别强调的是,即使是同一类型的摩擦本构关系,当初始应力不同时(即不同的S值情况下),模拟给出的起始阶段速度也不一样(见图 6中上、下图所对应的到时基本上都有所不同).但是,图 5b、5f结果显示RW摩擦关系模拟给出的破裂速度从成核后到自发破裂过程中,破裂速度变化不大.该认识与Fukuyama和Madariaga(1998)和Bizzarri等(2001)的模拟结果具有一致性.

(4) 不同摩擦关系模拟给出的滑移速度峰值不同

由图 6可以看出,不同摩擦关系控制下,断层面上相同质点的滑动速率峰值不同.在高S值条件下(S=1.79), RW摩擦关系(图 6b)给出的滑动速率峰值要低于其他摩擦关系的结果;低S值条件下(S=0.9),破裂传播到该质点(距离成核中心15 km处)时,通过RW摩擦关系模拟所对应的破裂前峰传播速度高于剪切波速度(处于超剪切状态)(见图 5f),RW摩擦关系模拟给出的滑动速率峰值与其他摩擦关系的比较接近(断层破裂都为超剪切破裂),这时RS-al摩擦关系给出的滑移速率峰值最低.图 6还清晰地显示,无论哪种摩擦关系的模拟结果,都是超剪切破裂时的滑移速率高于亚剪切破裂的结果.此外,所有摩擦关系模拟给出的滑动速率峰值对应的时刻明显滞后于剪应力峰值对应的时刻,即是说剪切应力峰值过后才会出现滑动速率的峰值(Bizzarri and Cocco, 2003).

3 问题讨论文中利用4种目前最常用的摩擦本构关系分别对断层自发破裂过程进行了有限单元法模拟,模拟结果显示,根据不同的摩擦关系断层都可以产生自发破裂过程,并且在较高应力水平下(低S值时)可以产生超剪切破裂现象.由此可见,文中的模拟结果与前人使用不同的方法给出的结果有一致性.但是,通过进一步考察不难发现,不同的摩擦关系模拟给出的断层破裂过程的特征还存在着较大的差异,那么究竟哪种摩擦关系更适合模拟实际天然地震的破裂过程?下面结合本文的模拟结果,就这一问题进行一些讨论.

首先,从图 3—4中模拟给出的不同时刻质点振动速度云图快照可知,无论是哪种类型的摩擦关系,其模拟结果都是质点振动速度随着传播距离越来越大;而且只要断层足够长,破裂就不会停止.显然,该结果与实际的天然地震破裂过程不完全符合,因为实际地震的断层破裂最终都会停止.当然,破裂终止的原因是多方面的,有可能是断层几何的变化、介质性质差异或应力状态发生改变等.

其次,由图 5可知,所有模拟给出的断层破裂方式,除了图 5b中由速率弱化的摩擦关系模拟展示的破裂为脉冲型破裂外,文中利用其他不同的摩擦关系模拟给出的破裂方式基本上都是裂纹型破裂.这与实际的天然地震大都是脉冲型破裂、并且断层破裂后能够自行愈合的观测结果也是不一致的(Heaton, 1990; Beroza and Mikumo, 1996).Heaton(1990)通过对1985年墨西哥Michoacan地震(M=8.1)、1983年美国Borah Peak地震(M=7.3)等7个地震的位错空间分布特征的分析,认为位错的上升时间(rise time)(破裂点的滑移持续时间)远远小于整个断层破裂的持续时间,因此这7个地震的断层破裂属于脉冲型破裂.事实上,断层破裂后,要实现自行愈合,成为脉冲型破裂,除了上文指出的速度弱化的摩擦关系外(见图 5b), 若是在弱化的摩擦关系中,后面必须要有强化过程(Perrin et al., 1995).可见,实际地震中断层面上的摩擦关系可能是空间分布不均匀的,在有些区段摩擦是速率弱化(或滑移弱化),而在另一些断层段上摩擦应该是速率强化(或滑移强化)的.另外,脉冲型破裂还可以用障碍体模型机制(barrier model)(Lykotrafitis et al., 2006)来进行解释.障碍体模型中,断裂被多个不可破裂的障碍体(摩擦强度非常大,不会发生破裂)所分割,若障碍体之间的断层破裂为裂纹型破裂,当这种破裂到达障碍体端部时会被终止,此时产生的反射波可以反过来将裂纹型破裂愈合,由此形成脉冲型破裂.此外,岩石破裂实验结果显示,速率弱化的摩擦关系通常与断层破裂中的瞬态加热(flash heating)过程相联系(Beeler et al., 2008), 并且这时可以产生脉冲型破裂(Goldsby and Tullis, 2011).

再者,在断层自发破裂过程的数值模拟中,滑移弱化的摩擦关系是使用的最为广泛的(Ida, 1972; Andrews, 1976a, 1976b; Ohnaka and Yamashita, 1989;Bizzarri, 2011; Ohnaka, 2013;Zhu, 2018).自从Ida(1972)提出以来,该摩擦关系被大量的数值模拟使用,取得了十分丰富的成果.但是,滑移弱化的摩擦关系,如图 5a以及图 6a所示的破裂结果,模拟给出的破裂过程是不会终止的,显然这与实际天然地震的破裂过程有较大差距.实际上,Rubino等(2017)通过对岩石破裂演化过程的实验研究了破裂过程中的摩擦关系,研究结果不支持滑移弱化的摩擦关系.

近年来,速率状态相依的摩擦关系(公式(3)和(7))在研究断层破裂过程方面也得到十分广泛的应用(Bizzarri, 2011;Barbot et al., 2012).该模型中,摩擦不仅与滑动速率相关,还与滑动面的“状态”相依.在老化定律中,状态量是指滑动接触面的平均接触时间.状态量与摩擦系数是耦合起来的,要通过求解微分方程组才能得到数值解.速率-状态相依的摩擦关系可以用来模拟震间过程中断层之间的重新强化过程(Bizzarri, 2011).本文研究中,尽管利用速率状态相依摩擦关系的两种形式的模拟结果有很多相似性,但都不能模拟脉冲型破裂,破裂一旦成核后都无法终止,说明速率相依的摩擦关系也不能很好的模拟真实的地震破裂过程.为此,Barbot等(2012)在速率状态相依的摩擦关系中的速度弱化断层段的周围镶嵌着速度强化的摩擦本构关系,成功地模拟了美国San Andreas断层的Parkfield段、1966—2004年间发生的MW6.0地震的全部物理过程;模拟结果不仅准确地重现了不规则的地震复发周期及震级大小,还对每个地震破裂之前的成核过程、震间变形、同震破裂特征、震后滑移以及不同地震成核区的时、空转移等都进行了非常细致的模拟,并且与观测结果十分吻合,具有很高的预测预报地震前景.需要指出的是,若在数学形式上对速率-状态相依的摩擦定率进行修正,添加由于摩擦生热产生的温度变化项,成为速率-状态-温度相依的摩擦关系,可以模拟断层破裂的愈合行为(Bizzarri, 2010).但该摩擦关系还缺乏实验支持和坚实的物理基础,还有待深入研究.

因此,通过本文的模拟结果看,目前最常用的4种摩擦本构关系都不能完全地反映实际天然大地震破裂过程中的摩擦属性.可以想象,实际地震的破裂过程其摩擦关系应该非常复杂.但不管怎样,在破裂的起始阶段,应该是速度弱化或滑移弱化的(否则产生不了地震);地震过程中随着破裂的进行,不同断层段、不同应力状态下、不同温度、不同介质属性,在不同时刻的摩擦关系或许都是变化的;摩擦关系在断层面上的时、空分布也许都是不均匀的.此外,不同类型的地震、不同大小的地震,破裂过程中摩擦关系的时、空演变特征等可能都是不同的.所以,加强在物理实验室里开展岩石破裂演化过程实验从而获取破裂不同阶段的摩擦本构关系;数值模拟在不同状态下、不同时空分布的不同形式的摩擦关系对断层破裂过程的影响具有重要意义.

4 结论研究中利用有限元方法,给出了4种典型摩擦关系对模拟地震破裂过程的影响.通过计算、比较和分析,得出以下初步结论.

(1) 当模型参数相同时,不同摩擦关系模拟的破裂行为总体上具有一致性,都可以产生亚剪切破裂或超剪切破裂,并且破裂传播速度的大小与摩擦关系的类型无关.

(2) 当模型参数相同时,不同摩擦关系模拟的破裂结果还存在着较大的差异: 1)速率弱化摩擦关系可以模拟脉冲型破裂;而其他类型的摩擦关系只能模拟裂纹型破裂;2)不同摩擦关系模拟给出的超剪切破裂转换长度不同,特别是速率弱化的摩擦关系其转换长度几乎为0;3)从破裂成核发展到稳定的破裂所经历的过程不同,速率弱化摩擦关系很快就达到破裂的稳定状态;而其他类型摩擦关系模拟的破裂传播速度则是先缓慢而后加速,直至达到最后的稳定破裂速度.

(3) 本文所使用的4种经典的摩擦关系都不能完整地反映实际天然大地震破裂过程的摩擦属性,需要深入研究.所以,加强在物理实验室里开展岩石破裂演化过程实验从而获取摩擦本构关系;根据实际地震破裂过程中的仪器记录(如测震仪、强震仪、大地测量、钻孔测量等),反演地震破裂过程中摩擦关系的时空分布;模拟不同状态下、不同时空分布的不同形式的摩擦关系对断层破裂过程的影响,是我们深入认识天然大地震中破裂过程摩擦关系的有效手段.

致谢 非常感谢审稿专家的建设性意见.

Aagaard B T, Heaton T H, Hall J F. 2001. Dynamic earthquake ruptures in the presence of lithostatic normal stresses:Implications for friction models and heat production. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 91(6): 1765-1796. DOI:10.1785/0120000257 |

Ando R, Kaneko Y. 2018. Dynamic rupture simulation reproduces spontaneous multifault rupture and arrest during the 2016 MW7.9 Kaikoura earthquake. Geophysical Research Letters, 45(23): 12875-12883. |

Andrews D J. 1976a. Rupture propagation with finite stress in antiplane strain. Journal of Geophysical Research, 81(20): 3575-3582. DOI:10.1029/JB081i020p03575 |

Andrews D J. 1976b. Rupture velocity of plane strain shear cracks. Journal of Geophysical Research, 81(32): 5679-5687. DOI:10.1029/JB081i032p05679 |

Andrews D J. 1985. Dynamic plane-strain shear rupture with a slip-weakening friction law calculated by a boundary integral method. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 75(1): 1-21. |

Barbot S, Lapusta N, Avouac J P. 2012. Under the hood of the earthquake machine:Toward predictive modeling of the seismic cycle. Science, 336(6082): 707-710. DOI:10.1126/science.1218796 |

Beeler N M, Tullis T E. 1996. Self-healing slip pulses in dynamic rupture models due to velocity-dependent strength. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 86(4): 1130-1148. |

Beeler N M, Tullis T E, Goldsby D L. 2008. Constitutive relationships and physical basis of fault strength due to flash heating. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 113(B1): B01401. DOI:10.1029/2007JB004988 |

Beroza G C, Mikumo T. 1996. Short slip duration in dynamic rupture in the presence of heterogeneous fault properties. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 101(B10): 22449-22460. DOI:10.1029/96JB02291 |

Bizzarri A, Cocco M, Andrews D J, et al. 2001. Solving the dynamic rupture problem with different numerical approaches and constitutive laws. Geophysical Journal International, 144(3): 656-678. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-246x.2001.01363.x |

Bizzarri A, Cocco M. 2003. Slip-weakening behavior during the propagation of dynamic ruptures obeying rate-and state-dependent friction laws. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 108(B8): 2373. DOI:10.1029/2002JB002198 |

Bizzarri A. 2010. Pulse-like dynamic earthquake rupture propagation under rate-, state-and temperature-dependent friction. Geophysical Research Letters, 37(18): L18307. DOI:10.1029/2010GL044541 |

Bizzarri A, Dunham E M, Spudich P. 2010. Coherence of Mach fronts during heterogeneous supershear earthquake rupture propagation:Simulations and comparison with observations. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 115(B8): B08301. DOI:10.1029/2009JB006819 |

Bizzarri A. 2010c. How to promote earthquake ruptures:Different nucleation strategies in a dynamic model with slip-weakening friction. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 100(3): 923-940. DOI:10.1785/0120090179 |

Bizzarri A. 2011. On the deterministic description of earthquakes. Reviews of Geophysics, 49(3): RG3002. DOI:10.1029/2011RG000356 |

Byerlee J. 1978. Friction of rocks.//Rock Friction and Earthquake Prediction. Birkhäuser, Basel: 615-626.

|

Cocco M, Bizzarri A. 2002. On the slip-weakening behavior of rate-and state dependent constitutive laws. Geophysical Research Letters, 29(11): 11-1-11-4. |

Cochard A, Madariaga R. 1994. Dynamic faulting under rate-dependent friction. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 142(3-4): 419-445. DOI:10.1007/BF00876049 |

Cochard A, Madariaga R. 1996. Complexity of seismicity due to highly rate-dependent friction. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 101(B11): 25321-25336. DOI:10.1029/96JB02095 |

Das S, Aki K. 1977. A numerical study of two-dimensional spontaneous rupture propagation. Geophysical Journal International, 50(3): 643-668. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1977.tb01339.x |

Dieterich J H. 1978. Time-dependent friction and the mechanics of stick-slip. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 116(4): 790-806. |

Dieterich J H. 1979. Modeling of rock friction:1. Experimental results and constitutive equations. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 84(B5): 2161-2168. DOI:10.1029/JB084iB05p02161 |

Dieterich J H. 1981. Constitutive properties of faults with simulated gouge.//Carter N L, Friedman M, Logan J M eds. Mechanical Behavior of Crustal Rocks: The Handin Volume. Washington, DC: Geophysical Monograph Series, 24: 103-120.

|

Dieterich J H. 1994. A constitutive law for rate of earthquake production and its application to earthquake clustering. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 99(B2): 2601-2618. DOI:10.1029/93JB02581 |

Douilly R, Aochi H, Calais E, et al. 2015. Three-dimensional dynamic rupture simulations across interacting faults:The MW7.0, 2010, Haiti earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 120(2): 1108-1128. DOI:10.1002/2014JB011595 |

Duan B C. 2010. Role of initial stress rotations in rupture dynamics and ground motion:A case study with implications for the Wenchuan earthquake. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 115(B5): B05301. DOI:10.1029/2009JB006750 |

Dunham E M. 2007. Conditions governing the occurrence of supershear ruptures under slip-weakening friction. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 112(B7): B07302. DOI:10.1029/2006JB004717 |

Dunham E M, Belanger D, Cong L, et al. 2011. Earthquake ruptures with strongly rate-weakening friction and off-fault plasticity, Part 1:Planar faults. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 101(5): 2296-2307. DOI:10.1785/0120100075 |

Fukuyama E, Madariaga R. 1998. Rupture dynamics of a planar fault in a 3D elastic medium:rate-and slip-weakening friction. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 88(1): 1-17. |

Fukuyama E, Olsen K B. 2002. A condition for super-shear rupture propagation in a heterogeneous stress field. Pure and Applied Geophysics, 159(9): 2047-2056. DOI:10.1007/s00024-002-8722-y |

Gabriel A A, Ampuero J P, Dalguer L A, et al. 2012. The transition of dynamic rupture styles in elastic media under velocity-weakening friction. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 117(B9): B09311. DOI:10.1029/2012JB009468 |

Goldsby D L, Tullis T E. 2002. Low frictional strength of quartz rocks at subseismic slip rates. Geophysical Research Letters, 29(17): 25-1. |

Goldsby D L, Tullis T E. 2011. Flash heating leads to low frictional strength of crustal rocks at earthquake slip rates. Science, 334(6053): 216-218. DOI:10.1126/science.1207902 |

Gomberg J, Reasenberg P, Cocco M, et al. 2005. A frictional population model of seismicity rate change. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 110(B5): B05S03. DOI:10.1029/2004JB003404 |

Hamano Y. 1974. Dependence of rupture time history on the heterogeneous distribution of stress and strength on the fault plane. Eos Transactions American Geophysical Union, 55: 352. |

He C R. 1999. Comparing two types of rate and state dependent friction laws. Seismology and Geology (in Chinese), 21(2): 137-146. |

Heaton T H. 1990. Evidence for and implications of self-healing pulses of slip in earthquake rupture. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, 64(1): 1-20. DOI:10.1016/0031-9201(90)90002-F |

Helmstetter A, Shaw B E. 2009. Afterslip and aftershocks in the rate-and-state friction law. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 114(B1): B01308. DOI:10.1029/2007JB005077 |

Hirose T, Shimamoto T. 2005. Growth of molten zone as a mechanism of slip weakening of simulated faults in gabbro during frictional melting. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 110(B5): B05202. DOI:10.1029/2004JB003207 |

Ida Y. 1972. Cohesive force across the tip of a longitudinal-shear crack and Griffith's specific surface energy. Journal of Geophysical Research, 77(20): 3796-3805. DOI:10.1029/JB077i020p03796 |

Johnson T. 1981. Time-dependent friction of granite:implications for precursory slip on faults. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 86(B7): 6017-6028. DOI:10.1029/JB086iB07p06017 |

Kame N, Fujita S, Nakatani M, et al. 2013. Effects of a revised rate-and state-dependent friction law on aftershock triggering model. Tectonophysics, 600: 187-195. DOI:10.1016/j.tecto.2012.11.028 |

Kammer D S, Svetlizky I, Cohen G, et al. 2018. The equation of motion for supershear frictional rupture fronts. Science Advances, 4(7): eaat5622. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.aat5622 |

Kanamori H, Brodsky E E. 2001. The physics of earthquakes. Physics Today, 54(6): 34-40. DOI:10.1063/1.1387590 |

Kaneko Y, Avouac J P, Lapusta N. 2010. Towards inferring earthquake patterns from geodetic observations of interseismic coupling. Nature Geoscience, 3(5): 363-369. DOI:10.1038/ngeo843 |

Lapusta N. 2009. Seismology:The roller coaster of fault friction. Nature Geoscience, 2(10): 676-677. DOI:10.1038/ngeo645 |

Liu C, Bizzarri A, Das S. 2014. Progression of spontaneous in-plane shear faults from sub-Rayleigh to compressional wave rupture speeds. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 119(11): 8331-8345. DOI:10.1002/2014JB011187 |

Lykotrafitis G, Rosakis A J, Ravichandran G. 2006. Self-healing pulse-like shear ruptures in the laboratory. Science, 313(5794): 1765-1768. DOI:10.1126/science.1128359 |

Madariaga R, Cochard A. 1996. Dynamic friction and the origin of the complexity of earthquake sources. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(9): 3819-3824. DOI:10.1073/pnas.93.9.3819 |

Madariaga R, Olsen K B, Archuleta R. 1998. Modeling dynamic rupture in a 3D earthquake fault model. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 88(5): 1182-1197. |

Mair K, Marone C. 1999. Friction of simulated fault gouge for a wide range of velocities and normal stresses. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 104(B12): 28899-28914. DOI:10.1029/1999JB900279 |

Marone C. 1998. Laboratory-derived friction laws and their application to seismic faulting. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 26: 643-696. DOI:10.1146/annurev.earth.26.1.643 |

Marone C J, Scholtz C H, Bilham R. 1991. On the mechanics of earthquake afterslip. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 96(B5): 8441-8452. DOI:10.1029/91JB00275 |

Mizoguchi K, Hirose T, Shimamoto T, et al. 2007. Reconstruction of seismic faulting by high-velocity friction experiments:An example of the 1995 Kobe earthquake. Geophysical Research Letters, 34(1): L01308. DOI:10.1029/2006GL027931 |

Oglesby D D, Mai P M, Atakan K, et al. 2008. Dynamic models of earthquakes on the North Anatolian fault zone under the Sea of Marmara:Effect of hypocenter location. Geophysical Research Letters, 35(18): L18302. DOI:10.1029/2008GL035037 |

Ohnaka M, Yamashita T. 1989. A cohesive zone model for dynamic shear faulting based on experimentally inferred constitutive relation and strong motion source parameters. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 94(B4): 4089-4104. DOI:10.1029/JB094iB04p04089 |

Ohnaka M. 2013. The Physics of Rock Failure and Earthquakes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

|

Olsen K B, Madariaga R, Archuleta R J. 1997. Three-dimensional dynamic simulation of the 1992 Landers earthquake. Science, 278(5339): 834-838. DOI:10.1126/science.278.5339.834 |

Palmer A C, Rice J R. 1973. The growth of slip surfaces in the progressive failure of over-consolidated clay. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences, 332(1591): 527-548. DOI:10.1098/rspa.1973.0040 |

Parsons T. 2005. A hypothesis for delayed dynamic earthquake triggering. Geophysical Research Letters, 32(4): L04302. DOI:10.1029/2004GL021811 |

Perrin G, Rice J R, Zheng G T. 1995. Self-healing slip pulse on a frictional surface. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 43(9): 1461-1495. DOI:10.1016/0022-5096(95)00036-I |

Prakash V. 1998. Frictional response of sliding interfaces subjected to time varying normal pressures. Journal of Tribology, 120(1): 97-102. |

Rojas O, Dunham E M, Day S M, et al. 2009. Finite difference modelling of rupture propagation with strong velocity-weakening friction. Geophysical Journal International, 179(3): 1831-1858. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2009.04387.x |

Rubino V, Rosakis A J, Lapusta N. 2017. Understanding dynamic friction through spontaneously evolving laboratory earthquakes. Nature Communications, 8: 15991. DOI:10.1038/ncomms15991 |

Ruina A. 1983. Slip instability and state variable friction laws. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 88(B12): 10359-10370. DOI:10.1029/JB088iB12p10359 |

Scholz C, Molnar P, Johnson T. 1972. Detailed studies of frictional sliding of granite and implications for the earthquake mechanism. Journal of Geophysical Research, 77(32): 6392-6406. DOI:10.1029/JB077i032p06392 |

Scholz C H. 1998. Earthquakes and friction laws. Nature, 391(6662): 37-42. DOI:10.1038/34097 |

Scholz C H. 2002. The Mechanics of Earthquakes and Faulting. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

|

Somerville P G, Irikura K, Graves R, et al. 1999. Characterizing crustal earthquake slip models for the prediction of strong ground motion. Seismological Research Letters, 70(1): 59-80. DOI:10.1785/gssrl.70.1.59 |

Sone H, Shimamoto T. 2009. Frictional resistance of faults during accelerating and decelerating earthquake slip. Nature Geoscience, 2(10): 705-708. DOI:10.1038/ngeo637 |

Stoer J, Bulirsch R. 2013. Introduction to Numerical Analysis. New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

|

Tinti E, Spudich P, Cocco M. 2005. Earthquake fracture energy inferred from kinematic rupture models on extended faults. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 110(B12): B12303. DOI:10.1029/2005JB003644 |

Tsutsumi A, Shimamoto T. 1997. High-velocity frictional properties of gabbro. Geophysical Research Letters, 24(6): 699-702. DOI:10.1029/97GL00503 |

Tullis T E, Goldsby D L. 2003. Laboratory experiments on fault shear resistance relevant to coseismic earthquake slip. Southern California Earthquake Center Annual Progress Report, Los Angeles, Calif: Southern California Earthquake Center.

|

Ulrich T, Gabriel A A, Ampuero J P, et al. 2019. Dynamic viability of the 2016 MW7.8 Kaikōura earthquake cascade on weak crustal faults. Nature Communications, 10(1): 1213. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-09125-w |

Yao L, Shimamoto T, Ma S L, et al. 2013. Rapid postseismic strength recovery of Pingxi fault gouge from the Longmenshan fault system:Experiments and implications for the mechanisms of high-velocity weakening of faults. Journal of Geophysical Research:Solid Earth, 118(8): 4547-4563. DOI:10.1002/jgrb.50308 |

Yuan J, Zhu S B. 2014. FEM simulation of the dynamic processes of fault spontaneous rupture. Chinese Journal of Geophysics (in Chinese), 57(1): 138-156. |

Yuan J, Zhu S B. 2017. Numerical simulation of seismic supershear rupture process facilitated by a fault stepover. Chinese Journal of Geophysics (in Chinese), 60(1): 212-224. |

Zhang H Q, Zhang H M, Ge Z X, et al. 2014. Numerical simulation of spontaneous rupture propagation:dependence on constitutive parameters in rate-and state-dependent friction laws. Chinese Journal of Geophysics (in Chinese), 57(10): 3285-3295. DOI:10.6038/cjg20141016 |

Zhu S B, Zhang P Z. 2013. FEM simulation of interseismic and coseismic deformation associated with the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake. Tectonophysics, 584: 64-80. DOI:10.1016/j.tecto.2012.06.024 |

Zhu S B, Yuan J. 2016. Mechanisms for the fault rupture of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake (MS=8.0) with predominately unilateral propagation. Chinese Journal of Geophysics (in Chinese), 59(11): 4063-4074. DOI:10.6038/cjg20161111 |

Zhu S B, Yuan J, Miao M. 2017. Dynamic mechanisms for supershear rupture processes of the Yushu earthquake (MS=7.1). Chinese Journal of Geophysics (in Chinese), 60(10): 3832-3843. DOI:10.6038/cjg20171013 |

Zhu S B. 2018. Why did the most severe seismic hazard occur in theBeichuan area in the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake, China? Insight from finite element modelling. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, 281: 79-91. DOI:10.1016/j.pepi.2018.05.005 |

何昌荣. 1999. 两种摩擦本构关系的对比研究. 地震地质, 21(2): 137-146. |

袁杰, 朱守彪. 2014. 断层自发破裂动力过程的有限单元法模拟. 地球物理学报, 57(1): 138-156. DOI:10.6038/cjg20140113 |

袁杰, 朱守彪. 2017. 断层阶区对产生超剪切地震破裂的促进作用. 地球物理学报, 60(1): 212-224. DOI:10.6038/cjg20170118 |

张慧茜, 张海明, 盖增喜, 等. 2014. 断层自发破裂传播的数值模拟:速率状态摩擦定律本构参数的影响. 地球物理学报, 57(10): 3285-3295. DOI:10.6038/cjg20141016 |

朱守彪, 袁杰. 2016. 2008年汶川大地震单侧破裂过程的动力学机制研究. 地球物理学报, 59(11): 4063-4074. DOI:10.6038/cjg20161111 |

朱守彪, 袁杰, 缪淼. 2017. 青海玉树地震(MS=7.1)产生超剪切破裂过程的动力学机制研究. 地球物理学报, 60(10): 3832-3843. DOI:10.6038/cjg20171013 |

2020, Vol. 63

2020, Vol. 63