† Corresponding author. E-mail:

The nonlinear features of two-dimensional ion acoustic (IA) solitary and shock structures in a dissipative electron-positron-ion (EPI) quantum plasma are investigated. The dissipation in the system is taken into account by incorporating the kinematic viscosity of ions in plasmas. A quantum hydrodynamic (QHD) model is used to describe the quantum plasma system. The propagation of small but finite amplitude solitons and shocks is governed by the Kadomtsev-Petviashvili-Burger (KPB) equation. It is observed that depending on the values of plasma parameters (viz. quantum diffraction, positron concentration, viscosity), both compressive and rarefactive solitons and shocks are found to exist. Furthermore, the energy of the soliton is computed and possible solutions of the KPB equation are presented numerically in terms of the monotonic and oscillatory shock profiles

Nowadays, studies in quantum plasmas have become important due to their potential applications to quantum wells,[1] to spintronics,[2] plasmonics,[3–4] to microelectronics,[5] to nonlinear optics,[6] to astro-physics,[7] and to solid density target experiments.[8–9] The quantum plasmas were first studied by Pines[10] in regimes where we have a high density and a low temperature as compared to classical plasmas. At such high densities, the plasma behaves like a degenerate fluid and quantum mechanical effects play a pivot role in the dynamics. Generally, the quantum effects associated with the strong density correlation play a significant role in the plasma system when the de Broglie wavelength of the charged particles is larger than the Debye wavelength and is near to the Fermi wavelength. Under these conditions, the quantum hydrodynamic (QHD) model is a suitable method to describe the charged particle systems.[11–12] The QHD model consists of a set of equations that describe the transport of momentum and energy of the charged particles and includes quantum statistical pressure via the Fermi pressure and the quantum tunneling effect via the Bohm potential.[13] Numerous collective effects have been studied by a number of authors in the field of quantum plasmas.[14–19] Misra et al.[20] have studied the nonlinear propagation of two-dimensional quantum ion acoustic waves (QIAWs) in an electron-ion (EI) quantum plasma.

Most of the aforementioned works focus on the electron-ion plasma instead of the electron-positron-ion (EPI) plasma. Recently, there has been much attention in EPI plasmas for its potential application point of view to investigate new collective modes and instabilities. The EP plasma exists in active galactic nuclei,[21] in Van Allen radiation belts and near the polar cap of fast rotating neutron stars,[22–23] in semiconductor plasmas,[24] intense laser fields.[25] The EP plasmas that include an additional ion species, exhibiting a collective behavior and holding quasi-neutrality condition, will constitute an EPI plasma. In contrast to usual EI plasmas, it has been well established fact that the nonlinear propagation of acoustic modes behaves quite differently in EPI plasmas.[26–27] Nejoh[28] investigated the effect of ion temperature on the large amplitude IA waves in EPI plasma. Mushtaq and Shah[29] studied the effect of positron concentration on the nonlinear propagation of magnetosonic waves and found that the solitary waves in EPI plasma behaved quite differently than that of ordinary EI plasma. Out of several mechanisms, such as the effects of turbulence, collisions between charged and neutrals particles, Landau damping, wave particle interaction, etc., one possible dissipative mechanism, which is peculiar to plasmas, may be due to the kinematic viscosity, the effects of which were previously examined by many authors.[30–33] Rouhani et al.[34] studied the characteristic of IA shock waves in a dissipative quantum pair plasma with dust particulates. Hanif et al.[35] investigated the propagation characteristics of IA shock waves in an unmagnetized dense quantum plasma. Hossen and Mamun[36] investigated theoretically the basic features of the quantum IA solitary and shock structures in a strongly coupled cryogenic quantum plasma.

However, most of the above metioned investigations are limited to one-dimensional (1D) planar geometry, which may not be a realistic situation in laboratory devices, since the waves observed in laboratory devices are certainly not bounded in one dimension. The objective of the present investigation is to study the nonlinear propagation of solitary and shock waves in dissipative EPI quantum plasma in a two-dimensional planar geometry. The kinematic viscosities amongst the constituent plasma particles give rise to the dissipative term in the nonlinear evolution equation. The paper is organized in the following way. In Sec.

We consider a three component unmagnetized quantum plasma which is an admixture of degenerate electrons, degenerate positrons and singly charged non degenerate ions. The phase velocity of the wave is assumed to be vFi ≪ ω/k ≪ vFe, vFp (vFi, vFe, and vFp are the ion, electron, and positron Fermi velocities, respectively). We, therefore, ignore the quantum pressure and Bohm potential contributions of ions. Also, we have assumed that the positron annihilation time is larger than the inverse of the characteristic frequency of the IAWs. The basic equations governing the nonlinear dynamics of the IAWs in quantum plasma are given in dimensionless variables as follows[33,37]

In Eqs. (

To investigate the nonlinear propagation of the IAWs in quantum plasma, we shall employ the reductive perturbation method.[37,39] According to this method, we choose the stretching space time coordinates as

From the next order of ϵ, we obtain the following equations

Finally, eliminating the second order quantities from Eqs. (

Equation (

In the absence of weak transverse perturbation, the KPB equation (

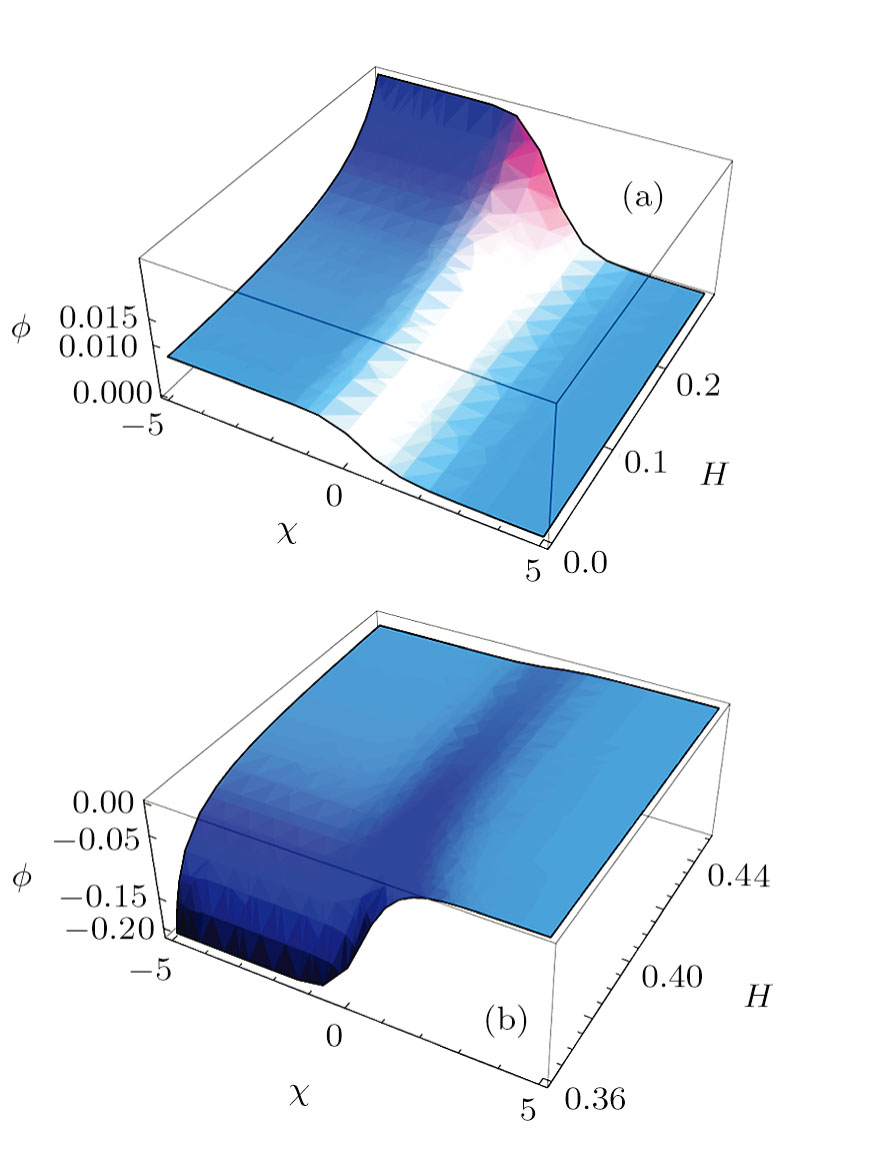

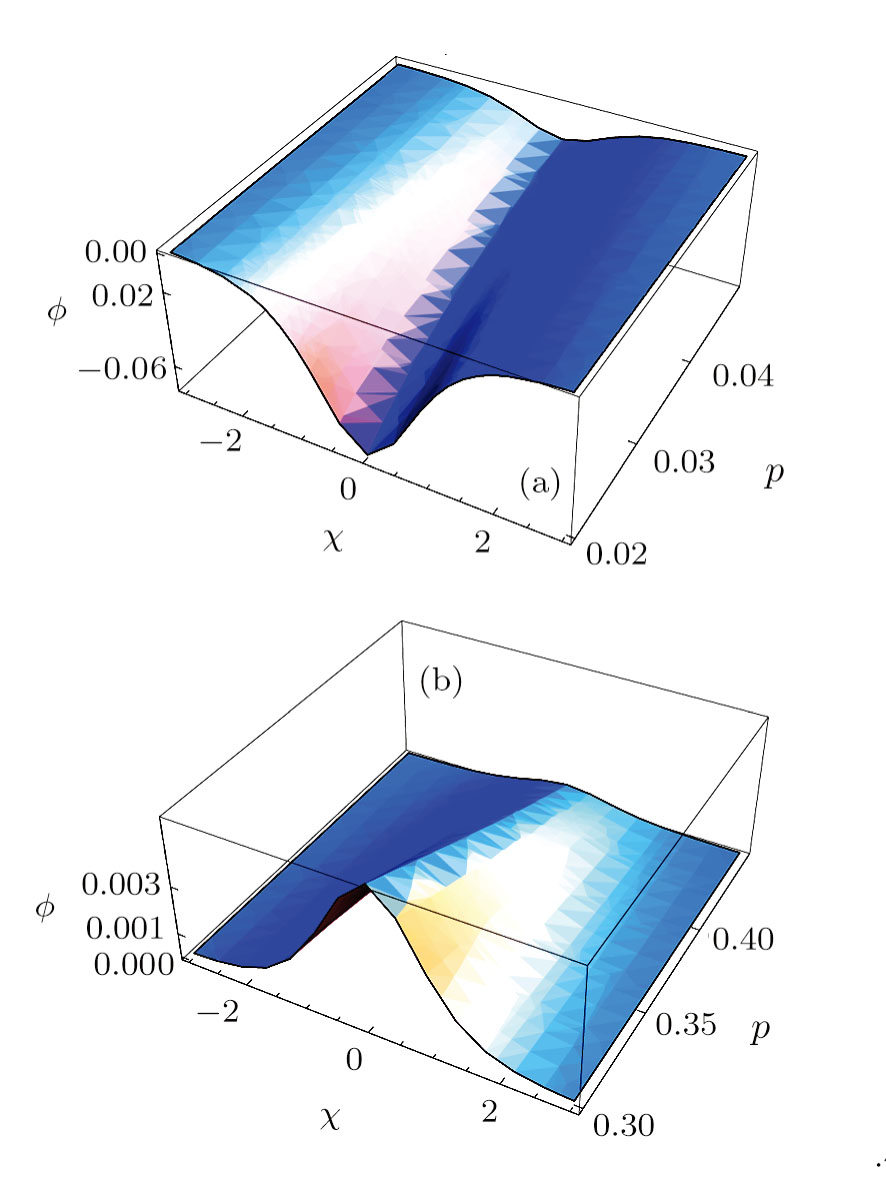

We now discuss the effects of the parametric dependence of the electrostatic shocks and solitons. The shock solution appears because of the dissipative term, which is proportional to the viscosity coefficient. In the above shock solution 21), mainly the factor (k = C/10B) determines the steepness of the shock. It is clear that the nonlinear coefficient A does not affect the shock steepness, whereas the weak transverse dispersion coefficient D affects neither the shock height nor its steepness. It only plays a role in shifting the shock from its initial position with the passage of time. Figures

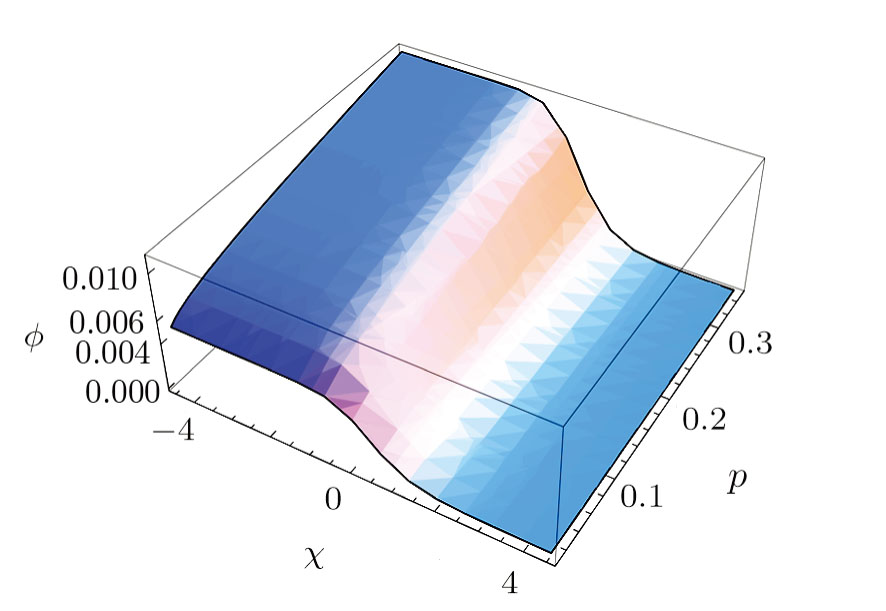

| Fig. 1 Plot of profiles ϕ for both the compressive and rarefactive ion-acoustic shocks given by Eq. ( |

| Fig. 2 Plot of profiles ϕ for ion-acoustic shocks given by Eq. ( |

If we ignore the dissipative coefficient (viscosity effect) in Eq. (

Figure

| Fig. 4 Plot of profiles ϕ for both the compressive and rarefactive ion-acoustic solitons given by Eq. ( |

The energy of soliton can be obtained as[43]

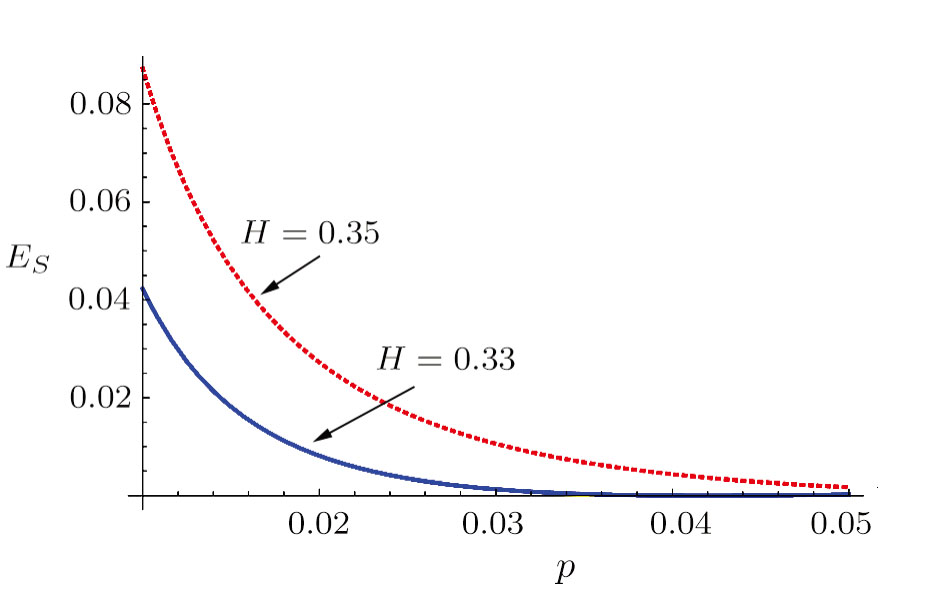

Based on the obtained results, we shall investigate the effects of the of the relevant physical quantities H and p on energy of soliton. Figure

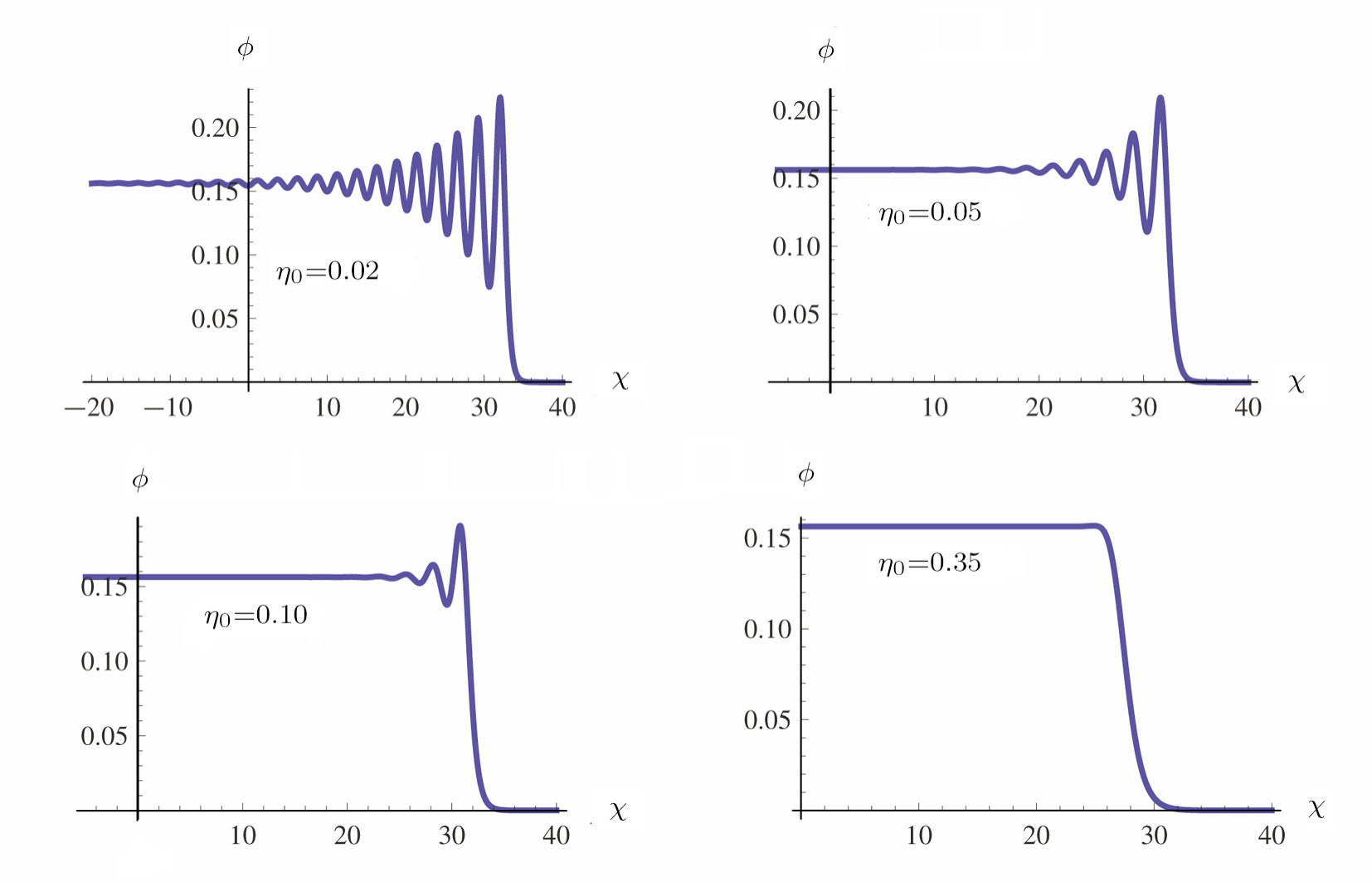

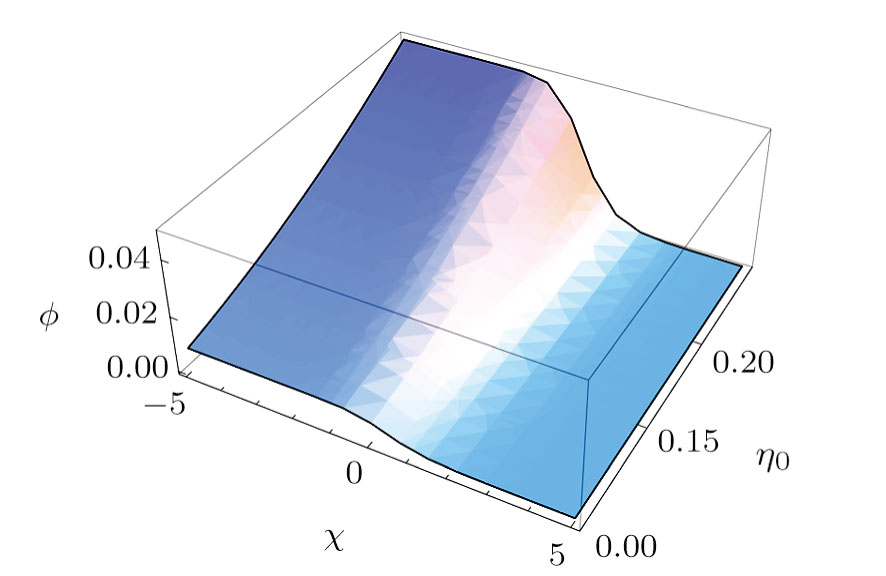

To examine the impact of the kinematic viscosity (η0), we numerically solve the KPB Eq. (

In conclusion, we have investigated the existence of compressive and rarefactive IASWs in a dense quantum plasma consisting of the electrons, positrons, and ions. It is shown that the evolution of two-dimensional nonlinear waves is governed by the KPB equation. Both the dissipative (due to kinematic viscosity) and dispersive (due to Bohm potential) effects are taken into consideration for the formation of QIA shock and soliton structures. The small amplitude compressive and rarefactive QIA shock and solitonic structures are obtained analytically and numerically from the KPB equation. It is observed that the kinematic viscosity, positron concentration, and Bohm potential affect the propagation characteristics of nonlinear QIA waves. Numerical simulation reveals that the transition from oscillatory to monotonic shocks occurs when the value of kinematic viscosity parameter increases. It is found that the energy of solitons is decreased when the positron concentrations are increased. The present investigation may be beneficial to understand the propagation of the nonlinear IA solitary waves and shocks in degenerate plasmas such as those in compact astrophysical objects and in laboratory plasmas.

| [1] | |

| [2] | |

| [3] | |

| [4] | |

| [5] | |

| [6] | |

| [7] | |

| [8] | |

| [9] | |

| [10] | |

| [11] | |

| [12] | |

| [13] | |

| [14] | |

| [15] | |

| [16] | |

| [17] | |

| [18] | |

| [19] | |

| [20] | |

| [21] | |

| [22] | |

| [23] | |

| [24] | |

| [25] | |

| [26] | |

| [27] | |

| [28] | |

| [29] | |

| [30] | |

| [31] | |

| [32] | |

| [33] | |

| [34] | |

| [35] | |

| [36] | |

| [37] | |

| [38] | |

| [39] | |

| [40] | |

| [41] | |

| [42] | |

| [43] | |

| [44] |