2. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049

2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

甲烷(CH4)是大气中重要的温室气体,在百年尺度上单分子CH4的全球增温潜势是CO2的28~34倍,CH4对全球温室效应的贡献达到了30%,全球气温对大气CH4浓度的变化非常敏感。目前大气中CH4浓度与工业革命前相比增长了150%,且年增长率也达到了近2000年来的最高值(IPCC,2013)。

全球CH4释放总量为500~600 Tg/yr,自然源CH4释放为总释放量的40%(Karakurt et al.,2012)。湖泊是大气CH4的重要释放源,据估计全球湖泊CH4释放量为8~48 Tg/yr,为自然源CH4释放总量的6%~16%(Bastviken et al.,2004)。而湖泊中的CH4主要来源于沉积物,是有机物厌氧分解的终端产物。水生和陆地生态系统产生的有机碳通过径流、沉降等作用最终到达湖底形成沉积物,在厌氧条件下,有机碳分解产生CH4。产生的CH4首先向沉积物-水界面传输,在这个界面附近CH4和氧气共存,CH4可被氧化成CO2或被微生物同化为细胞物质,这些又进一步成为湖泊初级和次级生产的潜在碳源。剩余的CH4气体成功到达湖水中,并最终部分释放到大气中。如加拿大Lake 227一年中总输入的碳有55%转化为CH4,又有36%的碳因CH4氧化而被再次利用(Rudd and Hamilton, 1978); 印度尼西亚的马塔纳湖有50%~100%的自生有机物被CH4产生菌分解,产生的CH4有一半以上被氧化(Crowe et al.,2011); Bretz和Whalen(2014)对6个阿拉斯加湖泊的研究发现,CH4氧化产生的碳是湖泊初级生产力的23%。可见,沉积物中CH4的产生和氧化影响到湖泊CH4的释放,是湖泊碳循环的重要组成部分。

笔者对国内外相关研究进行梳理,综述了湖泊沉积物CH4产生、氧化过程以及影响因素研究的主要成果,总结了湖泊富营养化和全球变暖对湖泊沉积物CH4产生和氧化的影响,归纳和总结了当前研究所面临的主要问题,展望未来研究方向。

1 CH4的产生及影响因素 1.1 CH4的产生大气CH4的70%~80%由生物产生(Le Mer and Roger, 2001)。生物来源的75%~80%的CH4由厌氧CH4产生菌产生(IPCC,2013)。在有机物厌氧分解过程的末端,CH4产生菌主要经过3个路径产生CH4(Zinder,1993): ①氢营养型产CH4,是H2还原CO2产生CH4; ②乙酸发酵产CH4,过程是乙酸中的羧基氧化成CO2,甲基还原成CH4; ③甲基营养型产CH4,是甲基首先被还原为甲基辅酶M,然后被还原为CH4,相应的另一个甲基被氧化成CO2(Borrel et al.,2011)。因产生甲基化合物的先驱物质在淡水中含量很少,甲基营养型产CH4过程主要发生在海水中,所以淡水中的CH4主要由氢营养型和乙酸营养型产生。

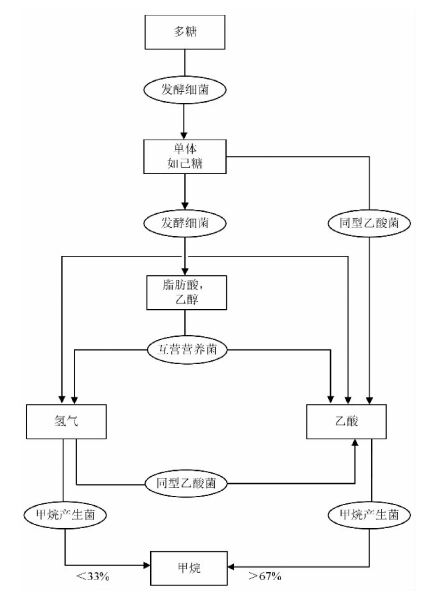

湖泊中的有机质主要来源于植物残体中的木质素和多糖,还有一些甲壳类动物的壳质,木质素在厌氧状态下不易分解。一般来讲,厌氧分解的主要物质为碳水化合物(Conrad,1999)。从动植物残体到CH4的形成中间要经过以下过程,这其中需要不同类型细菌(图 1)的参与: ①发酵细菌将多糖水解成单体(如己糖),随后单体发酵形成脂肪酸,乙醇,H2和CO2; ②同型乙酸菌直接将单体分解成乙酸; ③互养菌将醇类和脂肪酸分解成乙酸、H2和CO2; ④同型乙酸菌将H2/CO2转化成乙酸; ⑤CH4产生菌通过乙酸或H2/CO2途径产生CH4(Conrad,2002)。根据热力学原理计算的2种产CH4过程,乙酸产CH4过程的比例大于67%,H2/CO2产CH4的比例小于33%。

|

图 1 有机物厌氧分解产CH4的过程(据Conrad,1999) Figure 1 Pathway of anaerobic degradation of organic matter to methane(after Conrad,1999) |

一般而言,影响沉积物CH4产生的关键因素主要有2个: 一是有机碳的含量和矿化率; 二是CH4产生菌的生物量和活性。各种影响CH4产生的因素,如电子受体和温度等,都是直接或间接的影响了这2个方面。

1.2.1 有机物沉积物中CH4产生所需的底物—乙酸及H2/CO2,主要来自有机碳厌氧分解,有机碳含量对CH4产生有重要影响,一般认为沉积物中有机碳量与CH4产量正相关。Whiting和Chanton(1993)研究发现,CH4释放与净生态系统产量正相关,3%的日生态系统产量以CH4的形式释放到大气中。台湾湖泊、河流、水库等多种水域沉积物CH4产生与有机碳量显著相关(Yang,1998)。

除有机碳总量外,有机碳的矿化率也是影响沉积物CH4产生的重要因素。在沉积物有机碳组分中,易被分解的部分被认为是微生物的有效碳,这是CH4产生基质的主要来源。湖泊中的有机碳既包括陆生和挺水植物等高等植物所产生的,又有来自藻类等低等植物的部分,其中陆生和挺水植物大多含丰富的维管束和纤维素,为顽固性碳,而藻类等低等水生植物通常无维管束且含有较丰富的蛋白质,产生的有机碳更容易被CH4产生菌利用。Duc等(2010)通过对瑞典多个湖泊的研究,发现沉积物CH4产生率与C/N值显著负相关,CH4高产生率发生在C/N<10的沉积物中。West等(2012)比较了藻类和陆生植物对CH4产生的影响,发现添加藻类后CH4产生率增加较快,而添加陆生植物后CH4产生率增加缓慢,但持续时间长。

CH4产生率还会随着有机碳埋藏深度的增加而下降,且沉积物释放的CH4主要由表层几厘米范围内的新鲜有机碳产生(Kelly and Chynoweth, 1980; van den Pol-van Dasselaar and Oenema, 1999; Huttunen et al.,2002),这是因为底层沉积物有机碳含量低且经过长时间的分解有效碳大量减少,而剩余的碳为顽固性碳,不易被微生物所利用(Borrel et al.,2011)。底部沉积物的含水量也是影响其有机碳矿化的重要因素。研究发现,土壤含水量增加引起的溶解性有机碳的显著提高是导致其有机碳矿化率升高的主要原因(李忠佩等,2004); 有机碳矿化的适宜含水量为最大持水量的60%~70%(张文菊等,2005; 杨继松等,2008)。另外,CH4的产生还受到沉积物孔隙率的影响,湖泊底层沉积物因缺乏空间来存储产生的CH4,其实际CH4产生率远小于实验室测量值(Kelly and Chynoweth, 1980)。van den Pol-van Dasselaar和Oenema(1999)研究发现,随着深度增加,CH4产生率下降的速度比碳矿化率下降速度快,并认为其原因是产CH4菌比碳矿化细菌对有机碳质量的要求高。对不同深度沉积物中微生物的研究发现,CH4产生菌在地表 10 cm内的微生物中处于优势,而10 cm以下主要为混合菌种(Fan and Xing, 2016)。

虽然高有机物含量有利于CH4的产生,但是二者关系并非一成不变。室内控制实验表明,当乙酸浓度介于2.7~4.5 μmol/L时,增加乙酸浓度将不再增强CH4产生(Bretz and Whalen, 2014)。与乙酸产CH4不同的是,氢营养型产CH4中H2的最低浓度门槛值约为10 nmol/L(Borrel et al.,2011),即H2浓度超过这一值才能被产CH4菌利用,所以在某些情况下H2会成为CH4产生的限制因素(Conrad,1999; Bretz and Whalen, 2014)。

1.2.2 电子受体CH4主要在厌氧(还原)环境下产生,一般认为湖泊沉积物中的电子受体,如氧气,硝酸盐、硫酸盐、Fe3+,Mn4+等氧化剂的存在对CH4产生有抑制作用。Siegert等(2011)研究了不同电子受体的添加对碳氢化合物的分解和CH4产生的影响,发现当硫酸盐和硝酸盐浓度分别超过5 mmol/L和1 mmol/L时,CH4的产生明显受到抑制。电子受体的浓度因微生物的利用而逐渐下降,微生物对电子受体的利用顺序为: O2>NO3->Mn4+>Fe3+>SO42-(Capone and Kiene, 1988; Peters and Conrad, 1996; Karvinen et al.,2015b)。湖泊沉积物中CH4的产生发生在这些电子受体含量减少之后,如CH4浓度在氧气耗尽的深度以下出现显著上升(West et al.,2012); 当硫酸盐浓度小于30 μmol/L时,硫酸盐还原过程向CH4产生过程转变(Lovley and Klug, 1986); 硝酸盐含量降低后,意大利奥尔塔湖沉积物CH4含量明显升高(Adams and Baudo, 2001); 当沉积物中Fe3+浓度较低时其对CH4产生没有明显的抑制作用(Karvinen et al.,2015a)。

电子受体对CH4产生的影响主要有以下几个方面:①与CH4产生菌竞争底物。在硫酸盐还原过程中,乙酸中的甲基更多的被氧化成CO2而非还原成CH4,另外硫酸盐还原过程还会消耗H2,硫酸盐还原菌比CH4产生菌对H2的竞争能力更强(Nüsslein et al.,2001); 三价铁的存在导致CO2中的电子更多的用来还原三价铁而不能用于产生CH4(Liu et al.,2011); ②提高氧化还原电位。CH4产生主要发生在氧化还原电位小于-200 mV的还原环境中,这些电子受体的存在导致环境中氧化还原电位升高,使得CH4产生菌活性降低; ③某些电子受体或其产物对CH4产生菌有毒害作用(王维奇等,2009; Borrel et al.,2011)。

除氧气外,其他电子受体对CH4产生的影响一直备受争议,虽然这些电子受体抑制CH4产生的现象较为普遍,仍有研究得出了与之不相一致的结论: ①沉积物CH4产生未受到电子受体的显著影响。Bretz和Whalen(2014)对阿拉斯加6个湖泊的沉积物进行了添加电子受体(SO42-,Fe3+,NO3-,Mn4+)的室内培养实验,结果发现CH4产生速率并没有发生显著改变,他们认为这些湖泊沉积物中不存在与CH4产生菌竞争底物的细菌; Karvinen等(2015b)认为生长有莎草科植被的湖泊沉积物中铁含量对CH4释放的影响不显著; ②在一定条件下,某些电子受体对CH4产生过程有促进作用。如低含量的NaNO3会促进CH4的排放(胡敏杰等,2015); Fe3+的添加对十六烷分解产CH4过程起到了促进作用(Siegert et al.,2011); 在铁含量较低的沉积物中加入少量Fe3+将刺激CH4的产生(Karvinen et al.,2015a)。

1.2.3 温度温度对CH4产生的影响主要有2个方面: ①影响CH4产生途径; ②影响有机物分解和CH4产生菌活性。

湖泊沉积物CH4的产生主要有乙酸发酵型产CH4和H2/CO2产CH42种途径,其中温度被认为是一个重要的影响因素。在湖泊沉积物中,乙酸发酵型产CH4主要发生在温度较低的情形下,随着温度升高逐渐向氢营养型产CH4转变。Schulz和Conrad(1996)研究发现,4℃时主要为乙酸发酵型产CH4,到了20℃就有22%~33%的CH4来源于氢营养型产CH4过程。后续的研究得出了类似的结果,如Conrad(1999)观察到当温度从30℃降到15℃时,H2对CH4产生的贡献逐渐减少,乙酸成为CH4产生的主要底物; Nüsslein和Conrad(2000)观察到在原位的4℃温度下,主要为乙酸发酵型产CH4过程; 在人工培育的25℃温度下,CH4的产生来源于乙酸发酵和H2/CO2还原。Conrad(2002)试图从原理上对温度影响CH4产生途径的现象进行解释,他认为氢营养型产CH4的H2主要来自于丙酸盐的分解,而低温环境不利于丙酸盐形成,所以低温导致H2缺乏而使得乙酸发酵产CH4占主导。

一般认为,温度升高对CH4产生有促进作用。高温增强了微生物活性,促进了有机物的分解,增加了CH4产生菌底物的供应,而且高温使得电子受体的消耗速率加快(Liikanen et al.,2002a; Duc et al.,2010)。温度对CH4产生的影响可用Q10值(温度上升10℃时反应速率的变化)来描述,范围通常在1.3~28。低温时Q10较小,高温时Q10较大,如温度为4~10℃时,Q10<4.5; 温度为20~30℃时Q10高达24.5(Duc et al.,2010)。

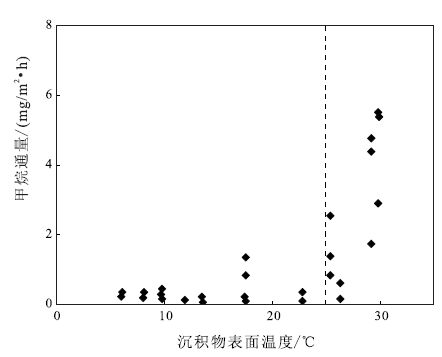

CH4产生率的增加与温度的升高并不呈线性关系。Yang(1998)在研究台湾多种水体的沉积物CH4产生率时,发现当培养温度低于12℃时,CH4产生受到明显的抑制,当温度由12℃升高到40℃时,CH4产生率随温度的升高而增大。CH4产生与温度的关系可能具有一个门槛值,当温度超过门槛值,CH4产生率显著增加。对武汉东湖沉积物表面CH4通量的研究揭示,其温度门槛值约为25℃(图 2)(Xing et al.,2005)。相对而言,高纬地区的温度门槛值低,低纬地区高(Pulliam,1993; Miller et al.,1999; Verma et al.,2002)。

|

图 2 沉积物表面温度与CH4通量关系(修改自Xing et al.,2005) Figure 2 Plot of CH4 flux versus sediment surface temperature (after Xing et al.,2005) |

空气中的CH4氧化包括光化学氧化和微生物氧化两部分,前者占总CH4汇的80%以上(Conrad,2009; Chowdhury and Dick, 2013),而沉积物中CH4的氧化主要由CH4氧化菌来完成,这其中又分为需氧氧化和厌氧氧化。

CH4的需氧氧化有2种形式,一种称为“高亲和力氧化”,即CH4浓度较低时(<12μL/L)发生的氧化,主要由高亲和力CH4氧化菌完成。该种CH4氧化方式仅占总CH4氧化量的10%(Topp and Pattey, 1997)。另一种方式称为“低亲和力氧化”,在CH4浓度超过40×10-6时进行,主要由CH4氧化菌完成。湖泊中的CH4氧化主要为“低亲和力氧化”,能够被氧化的CH4的浓度下限为2~3μL/L(Born et al.,1990)。CH4需氧氧化的过程为: CH4→CH3OH→HCHO→HCOOH→CO2,被氧化的CH4有50%~60%转化为CO2,剩余的30%~40%被CH4氧化菌同化吸收(Le Mer and Roger, 2001; Bretz and Whalen, 2014)。

与需氧氧化相比,CH4厌氧氧化(Anaerobic methane oxidation,AMO)的发现较晚,且对这个过程的关注是从海洋沉积物开始的。Reeburgh(1976)发现在海洋沉积物的缺氧层中CH4的含量急剧下降,而在含氧层中却没有CH4消耗,CH4的减少只可能是厌氧消耗造成的,首次证实了AMO的存在。之后的很多研究揭示AMO在湖泊CH4氧化中也起着重要作用(Eller et al.,2005; Deutzmann and Schink, 2011; Schubert et al.,2011; Nordi et al.,2013)。

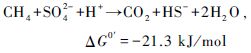

CH4厌氧氧化通常伴随着一些电子受体的还原,如硫酸盐、硝酸盐或亚硝酸盐、铁离子和锰离子等。硫酸盐还原型CH4厌氧氧化(Sulphate-dependent anaerobic methane oxidation,SAMO),主要是由CH4厌氧氧化古菌和硫酸盐还原菌共同作用完成(式1和2)。Eller等(2005)对德国Plusee湖的研究证明了湖泊中SAMO的存在。Schubert等(2011)认为当沉积物表面硫酸盐浓度大于2 mmol/L时,SAOM过程才较为明显,但最新研究发现SAMO在硫酸盐浓度小于3 μmol/L时仍有可能发生(Nordi et al.,2013)。

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

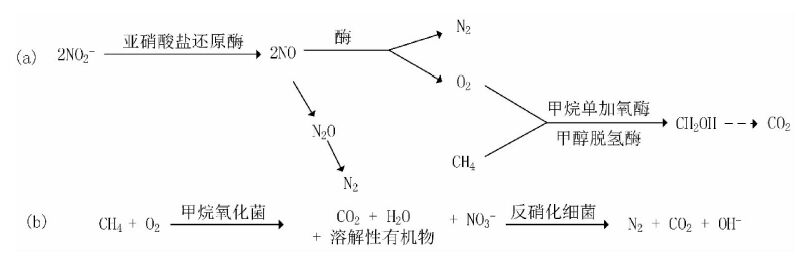

以硝酸盐为电子受体的CH4氧化可分为CH4厌氧氧化协同反硝化途径(Ettwig et al.,2010)(图 3a)和CH4好氧氧化协同反硝化途径(图 3b)。前一种途径称为反硝化型AMO(Denitrification-dependent anaerobic methane oxidation,DAMO)。DAMO途径的早期认识只存在于原理上,缺乏实验方面的证据,直到Raghoebarsing等(2006)从荷兰一个沟渠的沉积物中富集培养了该反应的菌群,证明淡水沉积物中DAMO作用模式(式3和4)的存在。之后Ettwig等(2010)对该过程中氧化CH4的O2的来源和N2的产生进行了解释,即通过2个NO的裂解,产生O2和N2,O2被用来氧化CH4(图 3a)。该过程在湖泊、湿地、水稻田等CH4排放的主要区域都有可能存在,因此可能为碳和氮的生物地球化学循环做出重要贡献,同时在减少CH4和氧化亚氮等温室气体排放方面也有很大的潜力(Shen et al.,2012)。

|

图 3 CH4厌氧氧化协同反硝化途径(a); CH4好氧氧化协同反硝化途径(b) Figure 3 Anaerobic methane oxidation coupled to denitrification(a); Aerobic methane oxidation coupled to denitrification(b) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

因Fe3+和Mn4+在河流和边缘海等水域中含量丰富,这2种AMO类型(式5和6)在海水(Beal et al.,2009)和淡水(Nordi et al.,2013)中都发现了存在的证据,但这个过程的研究还只停留在理论上,实验中关于这些电子受体和AMO耦合的直接证据很少,参与这些反应的生物也知之甚少。

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

目前关于CH4厌氧氧化的研究大多集中于机理的探讨,影响因素方面的研究较少,因此下文仅讨论CH4需氧氧化的主要影响因素: CH4、氧气浓度、温度、铵和重金属等。

2.2.1 CH4CH4是CH4氧化菌的唯一碳和能量来源(Le Mer and Roger, 2001),因此CH4浓度的增加促进CH4氧化菌种群的增长。Buchholz等(1995)比较了2个淡水湖泊沉积物,发现CH4浓度高的沉积物CH4氧化潜力也高。由此可做出假设,即高CH4产生率带来高CH4浓度,进一步引起高CH4氧化率。这一假设最终得到了实验结果的证实(Moore et al.,1994; Duc et al.,2010)。当CH4浓度高到一定程度时,CH4浓度或产生率将不再是CH4氧化的限制因素,这时其他因素对CH4氧化的影响作用增强。

2.2.2 氧气CH4氧化在有氧条件下才能发生,氧气浓度的升高有利于CH4的需氧氧化(Liikanen et al.,2002b)。但在一些相对缺氧的淹水环境下,某些界面上会存在薄的氧化层,这时CH4氧化就可能发生,如在沉积物-水界面、沉水植物叶鞘、水生植物的根际等。在湖泊沉积物中,因CH4和氧气在沉积物-水界面同时存在且浓度较高,所以该处成为CH4需氧氧化的主要场所,CH4氧化的比例为50%~95%(Kuivila et al.,1988; Frenzel et al.,1990; Liikanen et al.,2002b)。

2.2.3 温度温度升高可促进CH4的需氧氧化,主要表现在: ①促进CH4氧化菌的群落结构改变和活性增强; ②提高CH4氧化过程中酶的活性(He et al.,2012)。CH4氧化的Q10值为1.4~2.1,通常小于CH4产生的Q10值(1.3~28),所以一般认为CH4氧化对温度的响应没有CH4产生敏感(Duc et al.,2010)。但另一方面,CH4氧化对温度的耐受性更强,在-4~30℃范围内,均有CH4氧化的发生(Crill,1991; King and Adamsen, 1992)。需要指出的是,温度升高促进CH4氧化的结论大都建立在CH4充足的前提下。Lofton等(2014)研究认为,当CH4不足时,CH4氧化主要受控于CH4的供应,而与温度无关。

2.2.4 铵从原理上来说,铵对CH4氧化有抑制作用。铵与CH4的化学结构相似,它可以通过与CH4竞争CH4单加氧酶而抑制CH4氧化,这种单加氧酶对CH4的氧化非常关键。铵氧化菌还可与CH4氧化菌竞争氧气,从而抑制CH4氧化。铵氧化产生的亚硝酸盐可直接对CH4氧化菌造成毒害(Castro et al.,1994)。但在实际研究中,铵与CH4氧化的关系颇为复杂。如Conrad和Rothfuss(1991)研究发现,在上覆水中添加铵会增加CH4通量。Liikanen和Martikainen(2003)发现,铵的增加不影响沉积物CH4的释放。van der Nat等(1997)认为当铵浓度超过CH4浓度的30倍时,铵才是CH4氧化的一个有效抑制剂。Cai和Mosier(2000)研究认为只有当CH4起始浓度不是很高时(<500 μL/L),铵对CH4氧化的抑制作用才明显,当CH4浓度较高(>1000 μL/L)时,抑制作用减弱或消失,甚至随着铵的添加,铵对CH4氧化转变为促进作用。当CH4浓度较高时,某些CH4氧化菌对铵的添加具有一定的容忍度,使得铵对CH4氧化的抑制作用消失(Crossman et al.,2006)。综合以上观点,可知铵对CH4氧化的抑制作用决定于铵和CH4的配置关系,铵对CH4氧化的影响仍需要更多的研究来补充和验证。

2.2.5 重金属CH4氧化所需的CH4单加氧酶的活性与铜的可利用性有关(Stanley et al.,1983)。Buchholz等(1995)首次对湖泊沉积物CH4氧化率和孔隙水中铜浓度的关系进行分析,发现游离铜离子是CH4氧化的限制因子之一。后来的研究对铜在CH4氧化菌细胞的基因表达和蛋白质组中所扮演的角色、铜对酶活性的影响以及CH4氧化菌的铜吸收系统等机理性问题进行了探讨(Semrau et al., 2010,2013),进一步明确了铜和CH4氧化的关系。

研究发现,Pb、Ca和Hg等重金属对CH4氧化菌活性有显著的抑制作用,并且随着重金属离子浓度的升高,抑制作用增强(李昀地等,2011; 郑勇等,2012)。

3 实验方法和意义非原位的对土壤或沉积物的室内培养实验可测量CH4产生和氧化潜力。实验中也可加入CH4产生或氧化抑制剂进行对比(Le Mer and Roger, 2001)。

传统的判定CH4产生途径的方法是加入特异性的抑制剂,如CH3F或NH4Cl抑制利用醋酸产生CH4的反应,此时产生的CH4则认为是来自于H2/CO2。 近些年来碳同位素技术的运用为CH4产生路径的定量化分析创造了条件: ①放射性同位素示踪,例如用14 C标记区分碳酸氢根和醋酸中的碳,测定产生的CH4中14 C丰度计算碳酸氢根和醋酸各自的转化速率(Conrad,2005); ②CH4产生过程的同位素分馏效应明显,乙酸发酵产CH4的δ13 C为-65‰~-50‰,CO2还原产CH4的δ13 C为-110‰~-60‰。利用稳定同位素的分馏效应,通过测定产物和底物的同位素比值来计算不同产CH4途径对于总CH4的贡献率(Hershey et al.,2014; Gruca-Rokosz and Tomaszek, 2015)。随着CH4的氧化,剩余CH4的δ13 C逐渐增加,而产生的CO2的13 C丰度逐渐减少,所以碳同位素技术还可用来测定CH4氧化率,尤其在CH4厌氧氧化方面的应用逐渐增多(Krüger et al.,2002; Deutzmann and Schink, 2011; Hu et al.,2014; Ricão Canelhas et al.,2016)。

影响因素的实验分析主要是室内控制实验,如调节培养的温度,人工添加有机物和电子受体等(Xing et al.,2005; Duc et al.,2010; West et al.,2012; Bretz and Whalen, 2014)。近年来,随着定量化聚合酶链反应(PCR)分析,16S rRNA和基因克隆实验室分析等分子生物学技术的发展,CH4相关微生物的种群多样性和群落结构对影响因子变化的响应研究得到了开展(Semrau et al.,2013; Hu et al.,2014; Fan and Xing, 2016)。这些分子生物学手段与碳同位素技术的结合,为建立微生物的群落结构与对应的代谢功能之间的关系提供了新的研究思路(李清和林光辉,2013)。总的来看,室内模拟实验只关注单个因素的影响而忽略了各因素之间的相互作用,对单个因素的调控也有很大的人为不确定性,所以其研究结果可能与实际情况并不完全一致。因此,室内模拟与实际观测相结合才能有助于得出更可靠的结论。

4 相关研究热点湖泊不仅受自然环境的影响,而且还受人类活动的扰动,呈现出不同的生态环境问题。目前富营养化和全球变暖导致的湖泊生态环境变化引起广泛关注,由此带来的沉积物CH4循环的变化成为当前研究的热点。

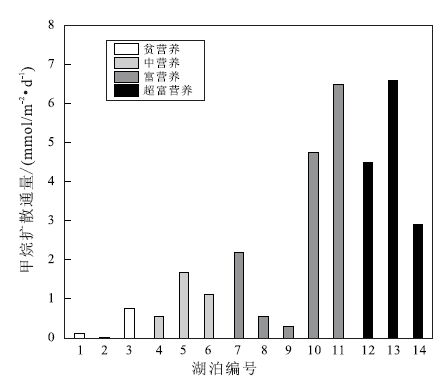

4.1 湖泊富营养化与CH4湖泊沉积物CH4的释放是CH4的产生、氧化及界面传输等过程综合作用的结果,各个过程都会受到相关因素的影响,因此不同湖泊的沉积物-水界面CH4释放通量差异较大。但总体来看,富营养湖泊的沉积物-水界面CH4释放量高于贫营养湖泊(图 4)。对全球19个湖泊进行的对比分析发现,富营养湖泊表面沉积物CH4浓度是贫营养湖泊的20倍,而高CH4浓度导致较高的沉积物-水界面CH4扩散通量(Tremblay et al.,2005)。富营养化导致湖泊的营养物质和有机碳输入增加,同时藻类爆发使得自生有机碳增加,沉积物CH4产生量增多。同时大量藻类的分解导致湖水和沉积物中溶解氧减少,CH4氧化率下降,产生率增加。这种状况在热带湖泊更为严重,因为这些湖泊分层稳定,极易产生永久性的厌氧层(Tremblay et al.,2005)。Casper(1992)研究了4个不同营养水平的湖泊,发现富营养湖泊夏季沉积物表层CH4产生率最高,分析认为在富营养湖泊中,因氧化作用消耗大量氧气,沉积物上层和上覆水中氧气减少,沉积物-水界面氧化还原电位降低到-200 mV以下,这种还原环境和大量溶解性有机物的存在使得表层沉积物形成高CH4产生。Furlanetto等(2012)比较了不同深度沉积物间隙水CH4浓度,发现富营养湖泊各深度沉积物间隙水CH4浓度均显著高于贫营养湖泊,并且作者认为外源有机物的输入是引起湖泊富营养化和高CH4产生的主因。富营养化还会导致CH4产生的场所增多,当浅水湖泊发生蓝藻水华时,蓝藻因风浪扰动或被大型植物捕获而在湖滨带聚集,死亡的蓝藻富集在脱离沉积物的湖水中,当氧气耗尽时CH4产生也可在湖水中发生(Xing et al.,2012)。

|

不同编号所代表的湖泊及参考文献: 1. Lake Stechlin,Germany(Casper et al.,2003); 2. Lake Batata,Brazil(Leal et al.,2007); 3. Lake Taupo,New Zealand(Adams,1992); 4. Lake Washington,USA(Kuivila et al.,1988); 5. Lake Luiminkajrvi,Finland(Huttunen et al.,2006); 6. Lake Porttipahta,Finland(Huttunen et al.,2006); 7. Lake Bled,Slovenia(Ogrinc et al.,2002); 8. Lake Soiviojrvi,Finland; 9. Lake Takajrvi,Finland; 10. Lake Ranuanjrvi,Finland(Huttunen et al.,2006); 11. Lake Izunuma,Japan(Lay et al.,1996); 12. Lake Tuusulanjrvi,Finland; 13. Lake Postilampi,Finland(Huttunen et al.,2006); 14. Lake Kevaton,Finland(Liikanen et al.,2002a) 图 4 不同营养水平湖泊沉积物-水界面CH4通量 Figure 4 Fluxes of CH4 from sediment to water in lakes of different nutrient levels |

CH4也会影响湖泊的富营养化。CH4氧化是加速湖泊氧气消耗的重要原因(Rudd and Hamilton, 1978),厌氧环境导致N、P等营养物质的释放增加,进一步加速湖泊的富营养化进程(Liikanen,2002)。

4.2 全球变暖与CH4最近对全球200多个湖泊进行的一项调查显示,世界各地的湖泊正在以比海洋和周围空气都要快的速度变暖(O'Reilly et al.,2015; Sharma et al.,2015),快速变暖将对湖泊生态系统造成普遍的影响,由此引发的湖泊CH4动态的变化值得关注。全球变暖直接或间接地从不同方面影响到湖泊沉积物CH4的产生和氧化。全球变暖造成的湖泊温度升高,直接影响到湖泊沉积物CH4的产生和氧化。湖泊升温能提高有机物的矿化率,使得CH4产生率增加。但同时CH4氧化率也会随着CH4浓度和温度的升高而增加,在一定情况下CH4产生的增加量可能与氧化量相互抵消(Lofton et al.,2014)。富营养湖泊中温度升高加速氧气的消耗,CH4的氧化可能会受到限制(White et al.,2008)。全球变暖还会引起湖泊及其流域植被和水文的变化,影响湖泊的自生和外来有机碳的输入,间接影响CH4的产生。在北方某些地区全球变暖还会造成冻土解冻,热融湖的数量增加,湖面扩张(Walter et al.,2006)。冻土表层为有机物丰富的苔原富冰黄土,解冻后可溶性有机物进入厌氧的湖泊底部,促进CH4的产生和释放(Zimov et al.,1997)。全球变暖还可通过改变湖泊物理状况影响沉积物CH4的产生和氧化。如变暖使得湖泊夏季分层稳定期延长,导致温带湖泊深水区缺氧,同时引起厌氧带的扩展,沉积物CH4产生增加,氧化减少,秋季湖水混合时CH4释放通量增大(Fernández et al.,2014)。热稳定期延长还会提高湖泊蓝藻爆发的风险(Rigosi et al.,2015),死亡的蓝藻富集在沉积物和湖水中,使得CH4产生增加,氧化下降。在北方地区变暖会造成湖泊冰期缩短,冰期缩短和气温升高使得湖泊夏季分层期提前(O'Reilly et al., 2015),沉积物CH4产生增加,氧化减少; 另一方面,冬季结冰期湖水稳定,下层湖水容易形成厌氧环境,是湖泊CH4的累积期,冰期缩短减少冰覆盖时的CH4累积时间,导致春季融冰后CH4释放减少(Fernández et al.,2014)。如上节所述,富营养湖泊沉积物-水界面CH4释放量更大。全球变暖造成的湖泊温度升高会提高沉积物N、P释放增加的风险,从而加剧湖泊的富营养化,增强CH4产生(Liikanen et al.,2002b)。

全球变暖引起的湖泊升温的速率还受到湖泊本身特征的影响,有着很大的空间异质性(O'Reilly et al.,2015),由此引起的湖泊CH4动态的变化也有较大差异。明确湖泊沉积物CH4的产生和氧化对湖泊升温的响应情况,是预测未来全球变暖情况下湖泊CH4释放的基础。但因为全球变暖带来的影响广泛,因子众多且相互影响,目前研究主要是采用室内控制实验或通过数学模型进行评估,缺乏野外的实地观测,所以很难得出比较全面且符合实际的结果。未来对该问题的研究如能将这几种方法有机结合,可能会得出更可靠的结论。

5 总结和展望CH4是大气中仅次于CO2的重要温室气体,而湖泊是大气CH4的重要释放源。沉积物中CH4的产生和氧化影响湖泊CH4的循环和释放,是湖泊碳循环的重要组成部分。本文阐述了湖泊沉积物CH4的产生和氧化过程及主要影响因素。湖泊CH4主要由沉积物厌氧分解产生,产生路径主要有氢营养型和乙酸发酵型2种。CH4的产生受到有机物、电子受体和温度的影响。CH4氧化有需氧氧化和厌氧氧化2种方式,前者发生在沉积物-水界面和湖水中,后者发生在CH4和电子受体含量较高的厌氧沉积物中。CH4氧化率与CH4和氧气浓度有关,并同时受到温度和铵的影响。总体来看,上述影响因素与CH4产生和氧化的关系仍需要更多的研究来定量分析,而且目前的研究主要集中于单个因素与CH4产生和氧化关系的研究,缺乏对各因素之间相互作用的分析。未来应在对不同环境和类型湖泊沉积物CH4产生和氧化及影响因素进行调查的基础上,找出各因素的关键阈值,并分析它们之间的相互作用。本文还介绍了CH4产生和氧化的实验方法及进展,并指出室内模拟和野外观测相结合是得出可靠结论的必由之路。

近年来,富营养化和全球变暖对湖泊沉积物CH4循环的影响逐渐成为研究热点。富营养化导致湖泊有机物和氧气消耗增多,促使CH4产生率增加,氧化率降低,沉积物CH4释放通量增加。目前富营养化与CH4产生和释放的关系已取得较多的成果,但其内部机理仍需进一步探讨,且湖泊的富营养化程度和CH4释放的关系缺少区域尺度上的定量化,而这对评估湖泊对CH4释放的贡献至关重要; 全球变暖对湖泊生态系统产生深远影响,除了引起湖水快速升温之外,全球变暖还会导致湖泊内部及其流域的植被、水文等的变化,气温的升高引起湖泊夏季分层期延长,并且在北方地区引起湖泊冰期缩短和冻土解冻,而后者将导致热融湖的数量增加和湖面扩张。这些全球变暖效应都会影响湖泊沉积物CH4的产生和氧化。未来对这2个问题的研究需要在提高室内模拟能力的同时更加注重野外的实地观测。

致谢: 写作过程中得到了许多老师和同学的指导和帮助,在此表示衷心的感谢!

| [1] | Adams D D. 1992. Sediment pore water geochemistry of Taupo Volcanic Zone lakes with special reference to carbon and nitrogen gases. Taupo:Taupo Research Laboratory File Report , 135 : 24. |

| [2] | Adams D D, Baudo R. 2001. Gases(CH4, CO2 and N2)and pore water chemistry in the surface sediments of Lake Orta, Italy:Acidification effects on C and N gas cycling. Journal of Limnology , 60 (1) : 79–90. |

| [3] | Bastviken D, Cole J, Pace M, Tranvik L. 2004. Methane emissions from lakes:Dependence of lake characteristics, two regional assessments, and a global estimate. Global Biogeochemical Cycles , 18 (4) : GB4009. |

| [4] | Beal E J, House C H, Orphan V J. 2009. Manganese-and iron-dependent marine methane oxidation. Science , 325 (5937) : 184–187. DOI:10.1126/science.1169984 |

| [5] | Born M, Dörr H, Levin I. 1990. Methane consumption in aerated soils of the temperate zone. Tellus B , 42 (1) : 2–8. DOI:10.1034/j.1600-0889.1990.00002.x |

| [6] | Borrel G, Jézéquel D, Biderre-Petit C, Morel-Desrosiers N, Morel J-P, Peyret P, Fonty G, Lehours A C. 2011. Production and consumption of methane in freshwater lake ecosystems. Research in Microbiology , 162 (9) : 832–847. DOI:10.1016/j.resmic.2011.06.004 |

| [7] | Bretz K A, Whalen S C. 2014. Methane cycling dynamics in sediments of Alaskan Arctic Foothill lakes. Inland Waters , 4 (1) : 65–78. DOI:10.5268/IW |

| [8] | Buchholz L A, Klump J V, Collins M L P, Brantner C A, Remsen C C. 1995. Activity of methanotrophic bacteria in Green Bay sediments. FEMS Microbiology Ecology , 16 (1) : 1–8. DOI:10.1111/fem.1995.16.issue-1 |

| [9] | Cai Z C, Mosier A R. 2000. Effect of NH4Cl addition on methane oxidation by paddy soils. Soil Biology and Biochemistry , 32 (11-12) : 1537–1545. DOI:10.1016/S0038-0717(00)00065-1 |

| [10] | Capone D G, Kiene R P. 1988. Comparison of microbial dynamics in marine and freshwater sediments:Contrasts in anaerobic carbon catabolism. Limnology and Oceanography , 33 (4, part 2) : 725–749. |

| [11] | Casper P. 1992. Methane production in lakes of different trophic state. Archiv für Hydrobiologie Beiheft Ergebnisse der Limnologie , 37 : 149–154. |

| [12] | Casper P, Furtado A L S, Adams D D. 2003. Biochemistry and diffuse fluxes of greenhouse gases and dinitrogen from the sediments of oligotrophic Lake Stechlin, northern Germany. Archiv für Hydrobiologie Beiheft Ergebnisse der Limnologie , 58 : 53–71. |

| [13] | Castro M S, Peterjohn W T, Melillo J M, Steudler P A, Gholz H L, Lewis D. 1994. Effects of nitrogen-fertilization on the fluxes of N2O, CH4, and CO2 from soils in a Florida slash pine plantation. Canadian Journal of Forest Research-Revue Canadienne de Recherche Forestiere , 24 (1) : 9–13. DOI:10.1139/x94-002 |

| [14] | Chowdhury T R, Dick R P. 2013. Ecology of aerobic methanotrophs in controlling methane fluxes from wetlands. Applied Soil Ecology , 65 : 8–22. DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2012.12.014 |

| [15] | Conrad R. 1999. Contribution of hydrogen to methane production and control of hydrogen concentrations in methanogenic soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiology Ecology , 28 (3) : 193–202. DOI:10.1111/fem.1999.28.issue-3 |

| [16] | Conrad R. 2002. Control of microbial methane production in wetland rice fields. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems , 64 (1-2) : 59–69. |

| [17] | Conrad R. 2005. Quantification of methanogenic pathways using stable carbon isotopic signatures:A review and a proposal. Organic Geochemistry , 36 : 739–752. DOI:10.1016/j.orggeochem.2004.09.006 |

| [18] | Conrad R. 2009. The global methane cycle:Recent advances in understanding the microbial processes involved. Environmental Microbiology Reports , 1 (5) : 285–292. DOI:10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00038.x |

| [19] | Conrad R, Rothfuss F. 1991. Methane oxidation in the soil surface-layer of a flooded rice field and the effect of ammonium. Biology and Fertility of Soils , 12 (1) : 28–32. DOI:10.1007/BF00369384 |

| [20] | Crill P M. 1991. Seasonal patterns of methane uptake and carbon dioxide release by a temperate woodland soil. Global Biogeochemical Cycles , 5 (4) : 319–334. DOI:10.1029/91GB02466 |

| [21] | Crossman Z M, Wang Z P, Ineson P, Evershed R P. 2006. Investigation of the effect of ammonium sulfate on populations of ambient methane oxidising bacteria by C-13-labelling and GC/C/IRMS analysis of phospholipid fatty acids. Soil Biology & Biochemistry , 38 (5) : 983–990. |

| [22] | Crowe S A, Katsev S, Leslie K, Sturm A, Magen C, Nomosatryo S, Pack M A, Kessler J D, Reeburgh W S, Roberts J A, González L, Haffner G D, Mucci A, Sundby B, Fowle D A. 2011. The methane cycle in ferruginous Lake Matano. Geobiology , 9 (1) : 61–78. DOI:10.1111/gbi.2010.9.issue-1 |

| [23] | Deutzmann J S, Schink B. 2011. Anaerobic oxidation of methane in sediments of lake constance, an oligotrophic freshwater lake. Applied and Environmental Microbiology , 77 (13) : 4429–4436. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00340-11 |

| [24] | Duc N T, Crill P, Bastviken D. 2010. Implications of temperature and sediment characteristics on methane formation and oxidation in lake sediments. Biogeochemistry , 100 (1-3) : 185–196. DOI:10.1007/s10533-010-9415-8 |

| [25] | Eller G, Känel L K, Krüger M. 2005. Cooccurrence of aerobic and anaerobic methane oxidation in the water column of lake plusssee. Applied and Environmental Microbiology , 71 (12) : 8925–8928. DOI:10.1128/AEM.71.12.8925-8928.2005 |

| [26] | Ettwig K F, Butler M K, Le Paslier D, Pelletier E, Mangenot S, Kuypers M M M, Schreiber F, Dutilh B E, Zedelius J, de Beer D, Gloerich J, Wessels H J C T, van Alen T, Luesken F, Wu M L, van de Pas-Schoonen K T, Op den Camp H J M, Janssen-Megens E M, Francoijs K-J, Stunnenberg H, Weissenbach J, Jetten M S M, Strous M. 2010. Nitrite-driven anaerobic methane oxidation by oxygenic bacteria. Nature , 464 (7288) : 543–548. DOI:10.1038/nature08883 |

| [27] | Fan X F, Xing P. 2016. The vertical distribution of sediment archaeal community in the "Black Bloom" disturbing Zhushan Bay of Lake Taihu. Archaea , 2016 : 8232135. |

| [28] | Fernández J E, Peeters F, Hofmann H. 2014. Importance of the autumn overturn and anoxic conditions in the hypolimnion for the annual methane emissions from a temperate lake. Environmental Science & Technology , 48 (13) : 7297–7304. |

| [29] | Frenzel P, Thebrath B, Conrad R. 1990. Oxidation of Methane in the oxic surface-layer of a deep lake sediment(Lake Constance). FEMS Microbiology Ecology , 73 (2) : 149–158. DOI:10.1111/fml.1990.73.issue-2 |

| [30] | Furlanetto L M, Marinho C C, Palma-Silva C, Albertoni E F, Figueiredo-Barros M P, Esteves F A. 2012. Methane levels in shallow subtropical lake sediments:Dependence on the trophic status of the lake and allochthonous input. Limnologica , 42 (2) : 151–155. DOI:10.1016/j.limno.2011.09.009 |

| [31] | Gruca-Rokosz R, Tomaszek J A. 2015. Methane and carbon dioxide in the sediment of a eutrophic reservoir:Production pathways and diffusion fluxes at the sediment-water interface. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution , 226 (2) : 1–16. |

| [32] | He R, Wooller M J, Pohlman J W, Quensen J, Tiedje J M, Leigh M B. 2012. Shifts in identity and activity of methanotrophs in arctic lake sediments in response to temperature changes. Applied & Environmental Microbiology , 78 (13) : 4715–4723. |

| [33] | Hershey A E, Northington R M, Whalen S C. 2014. Substrate limitation of sediment methane flux, methane oxidation and use of stable isotopes for assessing methanogenesis pathways in a small arctic lake. Biogeochemistry , 117 (2-3) : 325–336. DOI:10.1007/s10533-013-9864-y |

| [34] | Hu B L, Shen L D, Lian X, Zhu Q, Liu S, Huang Q, He Z F, Geng S, Cheng D Q, Lou L P. 2014. Evidence for nitrite-dependent anaerobic methane oxidation as a previously overlooked microbial methane sink in wetlands. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , 111 (12) : 4495–4500. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1318393111 |

| [35] | Huttunen J T, Väisänen T S, Hellsten S K, Heikkinen M, Nykänen H, Jungner H, Niskanen A, Virtanen M O, Lindqvist O V, Nenonen O S, Martikainen P J. 2002. Fluxes of CH4, CO2, and N2O in hydroelectric reservoirs Lokka and Porttipahta in the northern boreal zone in Finland. Global Biogeochemical Cycles , 16 (1) : 3–1. |

| [36] | Huttunen J T, Väisänen T S, Hellsten S K, Martikainen P J. 2006. Methane fluxes at the sediment-water interface in some boreal lakes and reservoirs. Boreal Environment Research , 11 (1) : 27–34. |

| [37] | IP CC. 2013. Climate Change 2013:The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Stocker T F, Qin D, Plattner G-K, Tignor M, Allen S K, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley P M eds. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA:Cambridge University Press : 1–1535. |

| [38] | Karakurt I, Aydin G, Aydiner K. 2012. Sources and mitigation of methane emissions by sectors:A critical review. Renewable Energy , 39 (1) : 40–48. DOI:10.1016/j.renene.2011.09.006 |

| [39] | Karvinen A, Lehtinen L, Kankaala P. 2015a. Variable effects of iron(Fe(Ⅲ))additions on potential methane production in boreal lake littoral sediments. Wetlands , 35 (1) : 137–146. DOI:10.1007/s13157-014-0602-6 |

| [40] | Karvinen A, Saarnio S, Kankaala P. 2015b. Sediment iron content does not play a significant suppressive role on methane emissions from boreal littoral sedge(Carex)vegetation. Aquatic Botany , 127 : 70–79. DOI:10.1016/j.aquabot.2015.09.001 |

| [41] | Kelly C A, Chynoweth D P. 1980. Comparison of in situ and in vitro rates of methane release in freshwater sediments. Applied and Environmental Microbiology , 40 (2) : 287–293. |

| [42] | King G M, Adamsen A P. 1992. Effects of temperature on methane consumption in a forest soil and in pure cultures of the methanotroph Methylomonas rubra. Applied & Environmental Microbiology , 58 (9) : 2758–2763. |

| [43] | Krüger M, Eller G, Conrad R, Frenzel P. 2002. Seasonal variation in pathways of CH4 production and in CH4 oxidation in rice fields determined by stable carbon isotopes and specific inhibitors. Global Change Biology , 8 (3) : 265–280. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2002.00476.x |

| [44] | Kuivila K M, Murray J W, Devol A H, Lidstrom M E, Reimers C E. 1988. Methane cycling in the sediments of lake Washington. Limnology and Oceanography , 33 (4) : 571–581. DOI:10.4319/lo.1988.33.4.0571 |

| [45] | Lay J J, Miyahara T, Noike T. 1996. Methane release rate and methanogenic bacterial populations in lake sediments. Water Research , 30 (4) : 901–908. DOI:10.1016/0043-1354(95)00254-5 |

| [46] | Le Mer J, Roger P. 2001. Production, oxidation, emission and consumption of methane by soils:A review. European Journal of Soil Biology , 37 (1) : 25–50. DOI:10.1016/S1164-5563(01)01067-6 |

| [47] | Leal J J F, Furtado A L, Esteves F A, Bozelli R L, Figueiredo-Barros M P. 2007. The role of Campsurus notatus(Ephemeroptera:Polymitarcytidae)bioturbation and sediment quality on potential gas fluxes in a tropical lake. Hydrobiologia , 586 (1) : 143–154. DOI:10.1007/s10750-006-0570-9 |

| [48] | Liikanen A. 2002. Greenhouse gas and nutrient dynamics in lake sediment and water column in changing environment. Doctoral Thesis. Kuopio:Kuopion Yliopisto . |

| [49] | Liikanen A, Huttunen J T, Valli K, Martikainen P J. 2002a. Methane cycling in the sediment and water column of mid-boreal hyper-eutrophic Lake Kevaton, Finland. Archiv für Hydrobiologie , 154 (4) : 585–603. DOI:10.1127/archiv-hydrobiol/154/2002/585 |

| [50] | Liikanen A, Murtoniemi T, Tanskanen H, Väisänen T, Martikainen P J. 2002b. Effects of temperature and oxygen availability on greenhouse gas and nutrient dynamics in sediment of a eutrophic mid-boreal lake. Biogeochemistry , 59 (3) : 269–286. DOI:10.1023/A:1016015526712 |

| [51] | Liikanen A, Martikainen P J. 2003. Effect of ammonium and oxygen on methane and nitrous oxide fluxes across sediment-water interface in a eutrophic lake. Chemosphere , 52 (8) : 1287–1293. DOI:10.1016/S0045-6535(03)00224-8 |

| [52] | Liu D, Dong H L, Bishop M E, Wang H M, Agrawal A, Tritschler S, Eberl D D, Xie S C. 2011. Reduction of structural Fe(Ⅲ)in nontronite by methanogen Methanosarcina barkeri. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta , 75 (4) : 1057–1071. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2010.11.009 |

| [53] | Lofton D D, Whalen S C, Hershey A E. 2014. Effect of temperature on methane dynamics and evaluation of methane oxidation kinetics in shallow Arctic Alaskan lakes. Hydrobiologia , 721 (1) : 209–222. DOI:10.1007/s10750-013-1663-x |

| [54] | Lovley D R, Klug M J. 1986. Model for the distribution of sulfate reduction and methanogenesis in fresh-water sediments. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta , 50 (1) : 11–18. DOI:10.1016/0016-7037(86)90043-8 |

| [55] | Miller D N, Ghiorse W C, Yavitt J B. 1999. Seasonal patterns and controls on methane and carbon dioxide fluxes in forested swamp pools. Geomicrobiology Journal , 16 (4) : 325–331. DOI:10.1080/014904599270578 |

| [56] | Moore T R, Heyes A, Roulet N T. 1994. Methane emissions from wetlands, southern Hudson Bay lowland. Journal of Geophysical Research:Atmospheres , 99 (D1) : 1455–1467. DOI:10.1029/93JD02457 |

| [57] | Nordi K A, Thamdrup B, Schubert C J. 2013. Anaerobic oxidation of methane in an iron-rich Danish freshwater lake sediment. Limnology and Oceanography , 58 (2) : 546–554. DOI:10.4319/lo.2013.58.2.0546 |

| [58] | Nüsslein B, Conrad R. 2000. Methane production in eutrophic Lake Plusssee:Seasonal change, temperature effect and metabolic processes in the profundal sediment. Archiv für Hydrobiologie , 149 (4) : 597–623. DOI:10.1127/archiv-hydrobiol/149/2000/597 |

| [59] | Nüsslein B, Chin K J, Eckert W, Conrad R. 2001. Evidence for anaerobic syntrophic acetate oxidation during methane production in the profundal sediment of subtropical Lake Kinneret(Israel). Environmental Microbiology , 3 (7) : 460–470. DOI:10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00215.x |

| [60] | Ogrinc N, Lojen S, Faganeli J. 2002. A mass balance of carbon stable isotopes in an organic-rich methane-producing lacustrine sediment(Lake Bled, Slovenia). Global and Planetary Change , 33 (1-2) : 57–72. DOI:10.1016/S0921-8181(02)00061-9 |

| [61] | O'Reilly C M, Sharma S, Gray D K, Hampton S E, Read J S, Rowley R J, Schneider P, Lenters J D, Mcintyre P B, Kraemer B M, Weyhenmeyer G A, Straile D, Dong B, Adrian R, Allan M G, Anneville O, Arvola L, Austin J, Bailey J L, Baron J S, Brookes J D, de Eyto E, Dokulil M T, Hamilton D P, Havens K, Hetherington A L, Higgins S N, Hook S, Izmest'eva L R, Joehnk K D, Kangur K, Kasprzak P, Kumagai M, Kuusisto E, Leshkevich G, Livingstone D M, MacIntyre S, May L, Melack J M, Mueller-Navarra D C, Naumenko M, Noges P, Noges T, North R P, Plisnier P D, Rigosi A, Rimmer A, Rogora M, Rudstam L G, Rusak J A, Salmaso N, Samal N R, Schindler D E, Schladow S G, Schmid M, Schmidt S R, Silow E, Soylu M E, Teubner K, Verburg P, Voutilainen A, Watkinson A, Williamson C E, Zhang G Q. 2015. Rapid and highly variable warming of lake surface waters around the globe. Geophysical Research Letters , 42 (24) : 10773–10781. DOI:10.1002/2015GL066235 |

| [62] | Peters V, Conrad R. 1996. Sequential reduction processes and initiation of CH4 production upon flooding of oxic upland soils. Soil Biology & Biochemistry , 28 (3) : 371–382. |

| [63] | Pulliam W M. 1993. Carbon dioxide and methane exports from a southeastern floodplain swamp. Ecological Monographs , 63 (1) : 29–53. DOI:10.2307/2937122 |

| [64] | Raghoebarsing A A, Pol A, van de Pas-Schoonen K T, Smolders A J P, Ettwig K F, Rijpstra W I C, Schouten S, Damsté J S S, Op den Camp H J M, Jetten M S M, Strous M. 2006. A microbial consortium couples anaerobic methane oxidation to denitrification. Nature , 440 (7086) : 918–921. DOI:10.1038/nature04617 |

| [65] | Reeburgh W S. 1976. Methane consumption in cariaco trench waters and sediments. Earth and Planetary Science Letters , 28 (3) : 337–344. DOI:10.1016/0012-821X(76)90195-3 |

| [66] | Ricão Canelhas M, Denfeld B A, Weyhenmeyer G A, Bastviken D, Bertilsson S. 2016. Methane oxidation at the water-ice interface of an ice-covered lake. Limnology and Oceanography . DOI:10.1002/lno.10288(inpress) |

| [67] | Rigosi A, Hanson P, Hamilton D P, Hipsey M, Rusak J A, Bois J, Sparber K, Chorus I, Watkinson A J, Qin B Q. 2015. Determining the probability of cyanobacterial blooms:The application of Bayesian networks in multiple lake systems. Ecological Applications , 25 (1) : 186–199. DOI:10.1890/13-1677.1 |

| [68] | Rudd J W M, Hamilton R D. 1978. Methane cycling in a eutrophic shield lake and its effects on whole lake metabolism. Limnology and Oceanography , 23 (2) : 337–348. DOI:10.4319/lo.1978.23.2.0337 |

| [69] | Semrau J D, DiSpirito A A, Yoon S. 2010. Methanotrophs and copper. FEMS Microbiology Reviews , 34 (4) : 496–531. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00212.x |

| [70] | Semrau J D, Jagadevan S, Dispirito A A, Khalifa A, Scanlan J, Bergman B H, Freemeier B C, Baral B S, Bandow N L, Vorobev A, Haft D H, Vuilleumier S, Murrell J C. 2013. Methanobactin and MmoD work in concert to act as the ‘copper-switch’ in methanotrophs. Environmental Microbiology , 15 (11) : 3077–3086. |

| [71] | Schubert C J, Vazquez F, Loesekann-Behrens T, Knittel K, Tonolla M, Boetius A. 2011. Evidence for anaerobic oxidation of methane in sediments of a freshwater system(Lago di Cadagno). FEMS Microbiology Ecology , 76 (1) : 26–38. DOI:10.1111/fem.2011.76.issue-1 |

| [72] | Schulz S, Conrad R. 1996. Influence of temperature on pathways to methane production in the permanently cold profundal sediment of Lake Constance. FEMS Microbiology Ecology , 20 (1) : 1–14. DOI:10.1111/fem.1996.20.issue-1 |

| [73] | Sharma S, Gray D K, Read J S, O'Reilly C M, Schneider P, Qudrat A, Gries C, Stefanoff S, Hampton S E, Hook S, Lenters J D, Livingstone D M, McIntyre P B, Adrian R, Allan M G, Anneville O, Arvola L, Austin J, Bailey J, Baron J S, Brookes J, Chen Y, Daly R, Dokulil M, Dong B, Ewing K, Eyto E, Hamilton D, Havens K, Haydon S, Hetzenauer H, Heneberry J, Hetherington A L, Higgins S N, Hixson E, Izmest'eva L R, Jones B M, Kangur K, Kasprzak P, Koster O, Kraemer B M, Kumagai M, Kuusisto E, Leshkevich G, May L, MacIntyre S, Muller-Navarra D, Naumenko M, Noges P, Noges T, Niederhauser P, North R P, Paterson A M, Plisnier P D, Rigosi A, Rimmer A, Rogora M, Rudstam L, Rusak J A, Salmaso N, Samal N R, Schindler D E, Schladow G, Schmidt S R, Schultz T, Silow E A, Straile D, Teubner K, Verburg P, Voutilainen A, Watkinson A, Weyhenmeyer G A, Williamson C E, Woo K H. 2015. A global database of lake surface temperatures collected by in situ and satellite methods from 1985-2009. Scientific Data , 2 : 150008. DOI:10.1038/sdata.2015.8 |

| [74] | Shen L D, He Z F, Zhu Q, Chen D Q, Lou L P, Xu X Y, Zheng P, Hu B L. 2012. Microbiology, ecology, and application of the nitrite-dependent anaerobic methane oxidation process. Frontiers in Microbiology , 3 : 269. |

| [75] | Siegert M, Cichocka D, Herrmann S, Grüendger F, Feisthauer S, Richnow H-H, Springael D, Krüger M. 2011. Accelerated methanogenesis from aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons under iron-and sulfate-reducing conditions. FEMS Microbiology Letters , 315 (1) : 6–16. DOI:10.1111/fml.2011.315.issue-1 |

| [76] | Stanley S H, Prior S D, Dalton H. 1983. Copper stress underlies the fundamental change in intracellular location of methane mono-oxygenase in methane-oxidizing organisms:Studies in batch and continuous cultures. Biotechnology Letters , 5 (7) : 487–492. DOI:10.1007/BF00132233 |

| [77] | Topp E, Pattey E. 1997. Soils as sources and sinks for atmospheric methane. Canadian Journal of Soil Science , 77 (2) : 167–177. DOI:10.4141/S96-107 |

| [78] | Tremblay A, Varfalvy L, Roehm C. 2005. Greenhouse gas emissions-Fluxes and processes. New York:Springer , 129 : 129–153. |

| [79] | van der Nat F W A, de Brouwer J F C, Middelburg J J, Laanbroek H J. 1997. Spatial distribution and inhibition by ammonium of methane oxidation in intertidal freshwater marshes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology , 63 (12) : 4734–4740. |

| [80] | van den Pol-van Dasselaar A, Oenema O. 1999. Methane production and carbon mineralisation of size and density fractions of peat soils. Soil Biology & Biochemistry , 31 (6) : 877–886. |

| [81] | Verma A, Subramanian V, Ramesh R. 2002. Methane emissions from a coastal lagoon:Vembanad Lake, West Coast, India. Chemosphere , 47 (8) : 883–889. DOI:10.1016/S0045-6535(01)00288-0 |

| [82] | Walter K M, Zimov S A, Chanton J P, Verbyla D, Chapin F S. 2006. Methane bubbling from Siberian thaw lakes as a positive feedback to climate warming. Nature , 443 (7107) : 71–75. DOI:10.1038/nature05040 |

| [83] | West W E, Coloso J J, Jones S E. 2012. Effects of algal and terrestrial carbon on methane production rates and methanogen community structure in a temperate lake sediment. Freshwater Biology , 57 (5) : 949–955. DOI:10.1111/fwb.2012.57.issue-5 |

| [84] | White J R, Shannon R D, Weltzin J F, Pastor J, Bridgham S D. 2008. Effects of soil warming and drying on methane cycling in a northern peatland mesocosm study. Journal of Geophysical Research:Biogeosciences , 113 (G3) : G00A06. |

| [85] | Whiting G J, Chanton J P. 1993. Primary production control of methane emission from wetlands. Nature , 364 (6440) : 794–795. DOI:10.1038/364794a0 |

| [86] | Xing P, Li H B, Liu Q, Zheng J W. 2012. Composition of the archaeal community involved in methane production during the decomposition of Microcystis blooms in the laboratory. Canadian Journal of Microbiology , 58 (10) : 1153–1158. DOI:10.1139/w2012-097 |

| [87] | Xing Y P, Xie P, Yang H, Ni L Y, Wang Y S, Rong K W. 2005. Methane and carbon dioxide fluxes from a shallow hypereutrophic subtropical Lake in China. Atmospheric Environment , 39 (30) : 5532–5540. DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2005.06.010 |

| [88] | Yang S S. 1998. Methane production in river and lake sediments in Taiwan. Environmental Geochemistry and Health , 20 (4) : 245–249. DOI:10.1023/A:1006536820697 |

| [89] | Zimov S A, Voropaev Y V, Semiletov I P, Davidov S P, Prosiannikov S F, Chapin F S, Chapin M C, Trumbore S, Tyler S. 1997. North Siberian lakes:A methane source fueled by Pleistocene carbon. Science , 277 (5327) : 800–802. DOI:10.1126/science.277.5327.800 |

| [90] | Zinder S H. 1993. Physiological ecology of methanogens. Berlin:Springer : 128–206. |

| [91] | 胡敏杰, 仝川, 邹芳芳. 2015. 氮输入对土壤CH4产生、氧化和传输过程的影响及其机制. 草业学报 , 24 (6) : 204–212. |

| [92] | 李昀地, 陈亮, 赵艮贵. 2011. 3种重金属离子对CH4氧化菌生长的影响. 山西大学学报(自然科学版) , 34 (2) : 315–319. |

| [93] | 李清, 林光辉. 2013. 稳定同位素技术研究湿地CH4产生的微生物过程进展. 同位素 , 26 (1) : 1–7. |

| [94] | 李忠佩, 张桃林, 陈碧. 2004. 可溶性有机碳的含量动态及其与土壤有机碳矿化的关系. 土壤学报 , 41 (4) : 545–552. |

| [95] | 王维奇, 曾从盛, 仝川. 2009. 控制湿地CH4产生的主要电子受体研究进展. 地理科学 , 29 (2) : 300–306. |

| [96] | 杨继松, 刘景双, 孙丽娜. 2008. 温度、水分对湿地土壤有机碳矿化的影响. 生态学杂志 , 27 (1) : 38–42. |

| [97] | 张文菊, 童成立, 杨钙仁, 吴金水. 2005. 水分对湿地沉积物有机碳矿化的影响. 生态学报 , 25 (2) : 250–253. |

| [98] | 郑勇, 郑袁明, 贺纪正. 2012. 水稻土CH4氧化菌对镉胁迫的响应. 生态环境学报 , 21 (4) : 737–743. |

2016, Vol. 35

2016, Vol. 35