2. 东北大学秦皇岛分校, 河北 秦皇岛 066004

2. The School of Resource and Material, Northeastern University at Qinhuangdao, Qinhuangdao 066004, China

生命起源/演化是重大而又最具争议的科学问题。超基性岩蛇纹石化为化能自养微生物群落提供了所需要的能量和初始物质,是生命起源最重要的变质水化反应(Proskurowski et al.,2008; Russell et al.,2010; Schrenk et al.,2013)。微生物活动则产生高浓度的有机物质,包括:脂肪族、芳香族化合物和官能团如酰胺的复杂的混合物,并常伴生物高分子聚合物。如,蛋白质、脂类和核酸(Ménez et al.,2012)。对蛇纹石化超基岩寄主生物圈的研究,有望获得地球古老而独特的前生命/生命有机质成因和演化的重要信息。不同构造环境的微生物类型和活动程度大相径庭,所赋存的有机质类型亦各有所异(Edwards et al.,2012)。面临的核心挑战是鉴别生命残存有机质的生物成因性和同生性(Oehler et al.,2009; Edwards et al.,2012; Oehler and Cady,2014; Summons and Hallmann,2014)。关于生命物质的生物成因性研究,通常需要综合探寻生命信息的化学、同位素、分子信号和矿物的生物学特征,或有机残渣的结构特征。氨基酸、基因序列和蛋白质折叠等的物理性质之间的密切联系,是构件地球最早生命至生物进化的关键因素(Carter Jr and Wolfenden,2015; Wolfenden et al.,2015)。蛇纹石化超基性岩体系中,有机化合物可能有多种来源:①蛇纹石化相关过程产生的非生物成因短链烷烃(Proskurowski et al.,2008); ②自养微生物贡献的生物质和代谢产物中的有机碳(Proskurowski et al.,2008; Ménez et al.,2012); ③超基性岩流体包裹体和晶格边界的幔源碳(Kelley and Früh-Green,1999); ④同蛇纹石化流体混合的下降流体贡献的光合作用衍生有机碳(Abrajano et al.,1990)。

研究这些系统中有机质的同位素特征和微生物的分子生物学特征,或许可提供相关线索。分子生物学研究发现,许多环境中存在产CH4微生物群落,包括Del Puerto蛇绿岩和Lost City热液活动区。进一步研究生物催化过程和它们的生理机能,可以确证该过程存在的事实(Kelley et al.,2005; Blank et al.,2009)。许多化合物可能同时具有生物成因和非生物成因特征,再加上沉积有机质热变质组分的贡献,将使得这种解释更为复杂和困难(Hosgormez et al.,2008; Bradley et al.,2009; Szponar et al.,2013)。多数情况下,鉴别地幔、非生物成因、热成因和生物过程的有机质产物是模棱两可的。Morrill等(2013)研究了现代蛇纹石化作用的地球化学和微生物地质学特征。最新研究表明,地球上的生命至少起源于41亿年前,较早期的研究提前了300万年(Bell et al.,2015)。本文拟通过对内蒙古温都尔庙蛇绿岩中,蛇纹石化橄榄岩气体组成,CO2和烷烃碳同位素组成,以及有机化合物组成探讨其生物成因特征。

1 蛇纹石化橄榄岩气体化学组成 1.1 蛇纹石化橄榄岩总碳和有机碳浓度蛇纹石化橄榄岩碳含量甚低。总碳浓度范围为0.18%~1.02%。其中,总有机碳浓度仅为0.01%~0.04%,总矿物碳为0.14%~0.98%(表 1)。

| 表 1 蛇纹石化橄榄岩碳含量 Table 1 TOC in serpentinized peridotite in the Wenduermiao ophiolite |

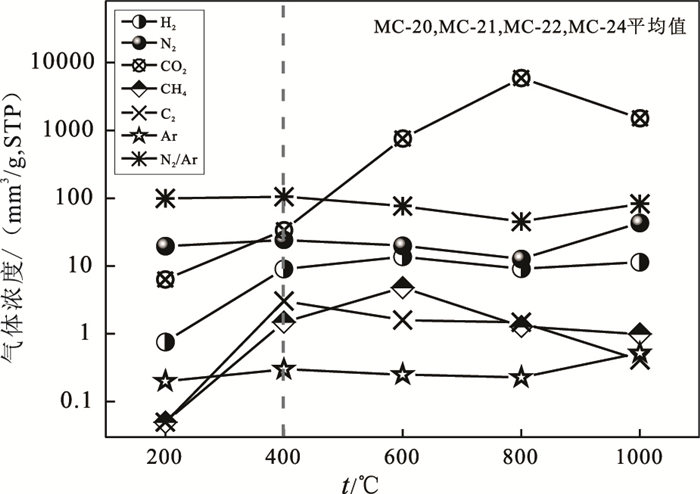

采用分段加热微量气体质谱计(MAT-271)分析技术,按200℃-400℃-600℃-800℃-1000℃加热脱气获得样品气体化学组成(张明峰等,2016)。表 2给出了不同加热温度段,样品MC-20、MC-21、MC-22和MC-24的气体浓度平值。

| 表 2 蛇纹石化橄榄岩气体组成随温度变化 Table 2 Varied gas concentrations at different temperatures in serpentinized peridotite in the Wenduermiao ophiolite |

200℃时,H2浓度极低,仅MC-21含有0.71 mm3/g(STP,下同)。该温度段缺失CH4和C2H6,N2、CO2和Ar浓度均较低,分别为19.63 mm3/g、6.31 mm3/g和0.20 mm3/g。N2/Ar值(99.27)较高。

400~1000℃,H2浓度显著增加(9.04~13.67 mm3/g)。N2浓度变化范围为19.92~43.33 mm3/g;CO2浓度剧烈变化(33.56~5883.2 mm3/g);Ar浓度和N2/Ar值变化范围分别为0.23~0.52 mm3/g和45.0~105.2(表 2,图 1)。

|

图 1 样品MC-20,MC-21,MC-22和MC-24的气体浓度平均值分布 Fig. 1 The average contents of gases(mm3/g)released at different temperatures from serpentinized peridotite in the Wenduermiao ophiolite |

200℃时,样品极低的气体浓度和缺失CH4、C2H6,可用以排除现代组分的污染。其N2/Ar值达99.27显示了非大气成因N2和Ar的贡献。400~1000℃,较高浓度的H2可能与岩石蛇纹石化有关。样品中CH4和C2H6的可能与样品中有机质热分解,或费-托合成作用有关。大气在水溶液中的N2/Ar值为~38,样品中的N2/Ar值为45.0~105.2,显然含有非大气成因N2和Ar的贡献,与岩石的变质作用有关。400~1000℃,CO2浓度的急剧增加,显然与碳酸盐矿物热分解相关。

由图 1可见,不同加热温CO2浓度变化约为3个量级,特别是600℃以上,反映了碳酸盐矿物热分解的贡献。其他组分变化均较为平缓,以Ar为最低,C2H6次之。H2浓度较大,400~1000℃,H2/CH4平均为6.87,与样品蛇纹石化H2的贡献有关。CH4/C2H6平均比值为0.49~3.00,显示了热成因烷烃的比值特征。

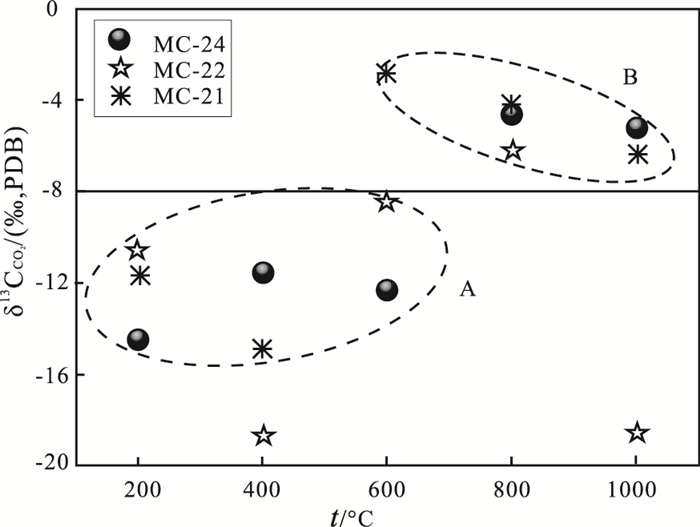

1.3 蛇纹石化橄榄岩CO2的碳同位素组成特征蛇纹石化橄榄岩中,可能含有大气、幔源、碳酸盐分解和有机质被氧化等多种来源的CO2,其δ13 C值各异。大气CO2的δ13 C值为-7‰,通常以此值为界,用以鉴别幔源CO2和有机成因CO2。图 2中δ13 C值可明确区别为A和B两组。A组数据,加热释放温度为200~600℃,δ13 C值远小于大气值(-7‰),显示了有机成因CO2特征。B组数据,加热释放温度为600~1000℃,δ13 C值大于-8‰,显示了幔源成因CO2特征。也就是说,这些样品的CO2有2种来源,一是有机成因CO2,二是幔源CO2。

|

图 2 样品MC-21,MC-22和MC-24的δ13 CCO2值分布 Fig. 2 The δ13 CCO2(PDB‰) values of CO2 released at different temperatures from serpentinized peridotite in the Wenduermiao ophiolite |

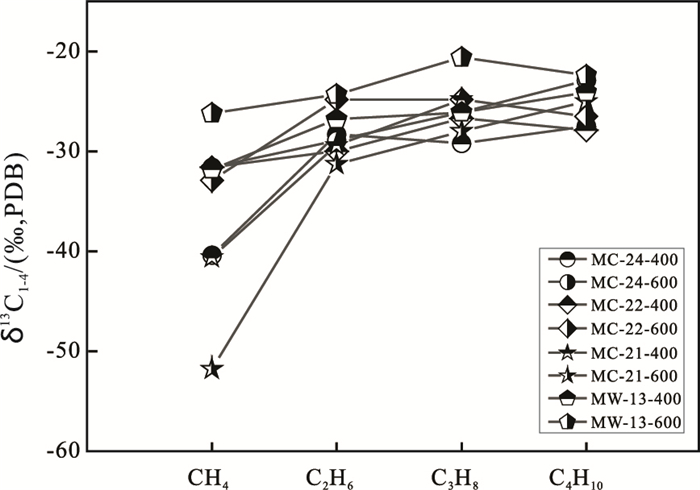

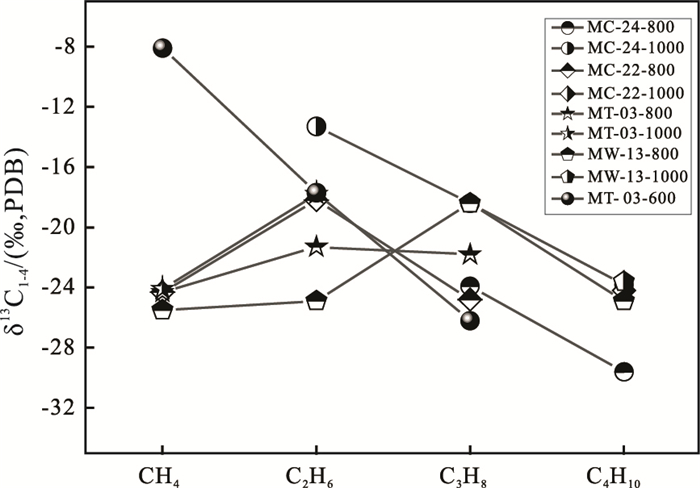

一般而言,复杂高分子沉积有机质经生物降解和热降解作用,生成简单的烷烃气体,其δ13 C值呈现“正序分布”特征,即δ13 C1<δ 13 C2<δ 13 C3<δ 13 C4。这种分布模式是鉴别典型生物成因气(热成因气和细菌成因气)的标志。非生物过程,由简单含碳分子(CO、CO2、CH4)聚合生成烷烃气体,其δ13 C值呈现“反序分布”特征,即δ13 C1>δ13 C2>δ13 C3>δ13 C4(Hu et al.,1998;Sherwood Lollar et al.,2002;Wang et al.,2009)。

图 3给出了400~600℃加热温度,正构烷烃碳同位素δ13 C值分布。样品MC-24、MC-22、MC-21和MW-13的烷烃碳同位素δ13 C值呈正序分布特征,即δ13 C1<δ 13 C2<δ 13 C3<δ 13 C4。结合CH4碳同位素δ13 C1值,-26.2‰~-51.8‰,可以认为这些烷烃是有机质热降解的产物。这些样品400~600℃加热温度,释放烷烃气体的生物成因特征,揭示了生物源有机质的贡献。

|

图 3 400~600℃正构烷烃碳同位素δ13 C值分布 Fig. 3 Plot of δ13 C values of C1-C4 alkanes released at 400~600℃ from serpentinized peridotite in the Wenduermiao ophiolite |

图 4给出了800~1000℃加热温度的碳同位素数据。正构烷烃碳同位素δ13 C值显示了反序和部分反序分布特征,显然不同于400~600℃热成因烷烃的同位素分布特征。它们或许是费-托聚合反应的产物。橄榄岩发生蛇纹石化期间,产生的大量H2与CO/CO2发生聚合反应而生成这部分烷烃,并原位赋存在相对稳定的矿物内部(分段加热技术有助于揭示气体的赋存特征)。

|

图 4 800~1000℃正构烷烃碳同位素δ13 C值分布 Fig. 4 Plot of δ13 C values of C1-C4 alkanes released at 800~1000℃ from serpentinized peridotite in the Wenduermiao ophiolite |

蛇纹石化橄榄岩的CO2和烷烃同位素组成,揭示了两种成因类型的CO2和烷烃。即生物成因的CO2、烷烃和非生物成因的CO2、烷烃。这些结果为研究超基性岩蛇纹石化作用提供了有益的实际资料,也为探索生命起源和演化提供了最基础的科学信息。

2 蛇纹石化橄榄岩的有机化合物蛇纹石化期间产生的分子氢和CH4可以被多种类型微生物群落用作代谢能量。这些生物通过化学能而不是太阳能来维持整个生物群落的发展(Russell et al.,2010; McCollom,2013)。丰富的化学能源和有利的有机化合物合成条件,使得蛇纹岩成为研究地球上生命起源的理想场所。这意味着蛇纹石化超基性岩生态环境体系,既含有非生物过程产生的前生命有机质,又可能含有化能生物群落残留的生命有机质,或两种类型有机质兼而有之。从非生物过程描述生物过程的物质和能量条件,是具有挑战性的地球生物学前沿研究领域。它将有助于探索和了解蛇纹岩微生物种群特征和其地球化学生存环境、前地球生命起源的边界条件(Wang et al.,2014)。

2.1 超基性岩天然体系的费-托聚合反应FTT 聚合反应常用来解释地球某些天然体系中CH4和其他烷烃的形成机制(Holm and Andersson,1998)。在超基性岩天然体系中,通过橄榄石水解产生H2的反应与FTT反应结合而形成CH4和其他复杂有机化合物(Charlou et al.,2002; McCollom et al.,2010)。FTT 反应被认为是地热系统和超基性岩中常见的反应,是生物学临界分子前躯物的非生物形成作用研究的焦点,比如形成氨基酸和脂肪等(Holm and Andersson,1998;Charlou et al.,1998,2002)。费托合成反应是地质环境中烃类和其他有机化合物最为广泛的生成途径。众多实验,研究了CH4和较高碳数烷烃的FTT非生物生成作用(Berndt et al.,1996; Horita and Berndt,1999; McCollom and Seewald,2001,2006,2007; McCollom,2013)。典型反应的初始产物,CH4和正烷烃同系物的丰度有规律地随碳数增加而减小。该过程亦可产生少量的其他化合物。包括,烯烃、支链烷烃和含氧化合物(Anderson and White,1994; McCollom et al.,1999)。如果存在氮源也能生成氨基酸、胺和其他含氮化合物(Hayatsu et al.,1968; Yoshino et al.,1971)。类异戊二烯或其他支链烃在FTT实验中仍然可以被合成,但这些化合物没有任何已知的非生物源。因此,蛇纹岩和富橄榄石样品中存在的类异戊二烯,目前只能归因于生物成因的(McCollom,2013)。

2.2 蛇纹石化橄榄岩热解-气相色谱-质谱分析实验条件对内蒙古温都尔庙蛇纹石化橄榄岩采用热解-气相色谱-质谱(Py-GC-MS-MS)技术,分段加热(200-400-600-800-1000℃)测定了全岩样品的有机化合物组分。分析仪器为日本Frontier Lab产Py-3030D热解仪,安捷伦GCQQQ(GC-MS-MS)气相色谱-三重四极杆质谱联用仪。实验条件:MS︰7000B,离子源电离能量:70eV;GC∶7890B,色谱柱:Ultra Alloy Capillary Column,30 m×0.25 mm×0.25 μm;程序升温:起始温度80℃,升温速率为10℃/min,至290℃,恒温30 min;进样口:S/SL进样口(分流/不分流进样口),分流进样,分流比30︰1;谱库:NIST11.L.。

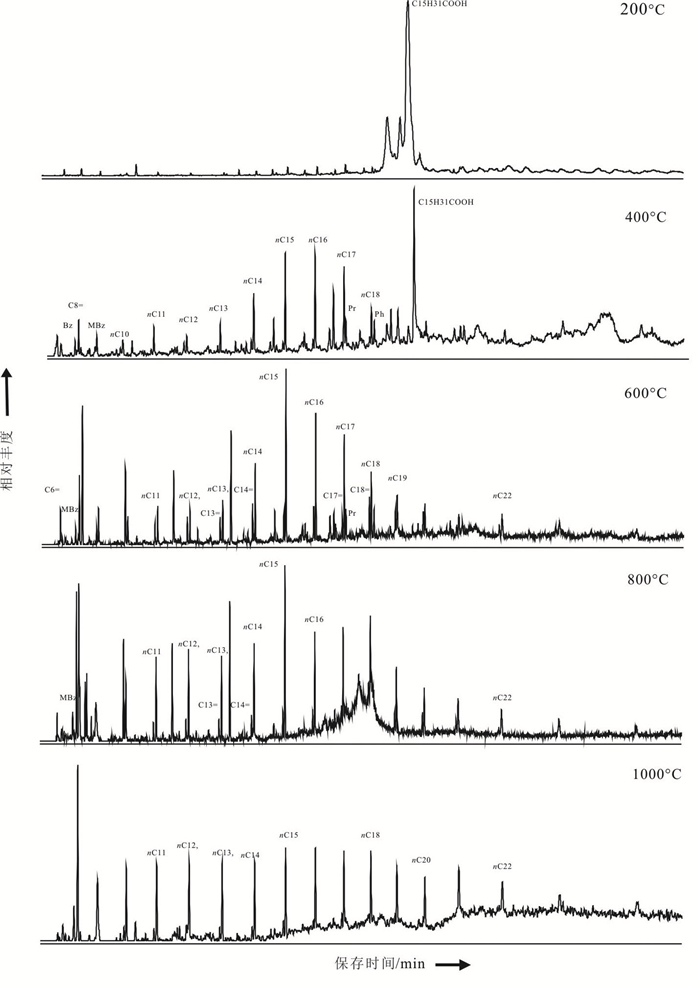

2.3 蛇纹石化橄榄岩有机化合物分析结果不同温度段的热解分析,提供了有机质赋存状态及其在高温加热阶段热解产物的基础资料,将有助于进一步探讨各类有机化合物的特征和来源。蛇纹石化橄榄岩全岩样品MC-20、MC-21、MC-22和MC-24的Py-GC-MS-MS 分析结果列于表 3和图 5中。加热温度和实测结果分述如下:

| 表 3 蛇纹石化橄榄岩有机化合物的热解-气相色谱-质谱分析结果 Table 3 The Py-GC-MS-MS analytical results of organic compounds in serpentinized peridotite |

|

图 5 蛇纹石化橄榄岩不同温度m/z85的色谱图 Fig. 5 Mass chromatograms(m/z85) of alkanes released at different temperatures from serpentinized peridotite |

(1)100~200℃:在TIC图谱中,样品MC-20和MC-22检测到正烷烃、姥鲛烷、植烷和芳香化合物。MC-21m/z85质量色谱图中检测到C10-C18正烷烃、姥鲛烷和植烷。MC-23的TIC图谱中检测到芳香化合物。这些样品有机化合物组成的差异,反映了样品有机质来源和演化特征的差异。同时也可能揭示了样品未受后期污染的可能性。

(2)200~400℃:4个样品的TIC图谱中,均含有烯烃和芳香烃。4个样品的m/z85质量色谱图中,含有不尽相同的正烷烃、姥鲛烷、植烷、正十六酸和4-辛烯烃。

(3)400~800℃:4个样品中含有不尽相同的,正烷烃和和相同碳数的单烯烃,1,3-丁二烯、4-辛烯烃、己烯-2,以及姥鲛烷、植烷、苯、甲苯、萘和菲等芳烃化合物。

(4)800~1000℃:含C9-C23正烷烃(有低碳数偏移趋势),以及甲苯、二甲苯、联苯,奈、甲基萘和菲等芳烃化合物。CO2和烯烃消失。

2.4 讨论100~400℃:蛇纹石化橄榄岩样品中饱和烃类由C10-C21正烷烃组成。显示了海洋有机质输入的贡献,同时也排除了陆源高等植物有机质的污染。存在类异戊二烯(姥鲛烷和植烷)生物标志化合物,表明海洋有机质输入以海藻成因有机质占优势(Brassell et al.,1981; Ten Haven et al.,1988; Grice et al.,1998; Kannenberg and Poralla,1999)。姥鲛烷和植烷源于光养生物体叶绿素-a的植醇侧链(Brassell et al.,1981),在所有蛇纹石化橄榄岩样品中均有发现。植烷也可能来源于某些古菌的脂类,特别是那些与CH4代谢有关的脂类(Goossens et al.,1984; Volkman and Maxwell,1986)。

400~800℃:该加热温度段,样品中有机质可能发生强烈的热裂解,各类化合物丰度显著增加。饱和烃类由C10-C23正烷烃组成,并伴随和相同碳数的单烯烃,烯烃出现在同碳数正烷烃之前。400~600℃,样品MC-20尚含有姥鲛烷、植烷。4个样品中还含有苯、甲苯,萘和菲等芳烃化合物。随温度升高,600~800℃烯烃和芳烃化合物相对丰度降低。

大多数蛇纹岩中存在类异戊二烯(姥鲛烷、植烷和角鲨烷),多环化合物(藿烷和甾烷类化合物),以及相对高的n-C16 至 n-C20正烷烃(Tornabene et al.,1979; Brassell et al.,1981; Ten Haven et al.,1988; Grice et al.,1998; Brocks and Summons,2003; Delacour et al.,2008b)。蛇纹岩中角鲨烷可能与CH4循环古菌有关(Brazelton et al.,2006; Delacour et al.,2008a)。角鲨烯(或在成岩作用转化为角鲨烷)是普遍的生物合成产物,它可能是常见的海洋微生物(例如藻类)指示剂(Peters and Moldowan,1992)。角鲨烷与其他类异戊二烯共存,可能反映了海洋超基性岩蚀变期间,输入的溶解有机碳。

800~1000℃:该加热温度段含C9-C23正烷烃,以及甲苯、二甲苯、联苯,奈、甲基萘和菲等芳烃化合物。在如此高温条件下有机质的裂解早已接近尾声。在如此高温条件下,碳酸盐矿物热分解作用的结束而致使CO2消失。烯烃化合物的热不稳定性也使之不复存在。该加热温度尚残存的正烷烃和芳烃化合物,难以从有机质热分解作用得到合理的解释。实验过程中分段加热技术,不仅仅揭示了有机质的热分解作用,而且可以反映物种在岩石中的赋存状态特征。即,加热温度在此种意义上,仅反映了物种赋存环境的能量位置和稳定性,从低温至高温赋存稳定性增大(王先彬,1989)。该加热温度段发现的正烷烃和芳烃化合物,应解释为蛇纹石化阶段的产物而赋存于高能量位置,而不是后期加入的有机质裂解所致。也就是说这些化合物不是生物成因的,而是非生物成因的。

如前所述,蛇纹石化橄榄岩中,低碳数烷烃碳同位素分布特征显示,低温加热阶段(<800℃)烷烃碳同位δ13 C值具正序分布特征(δ13 C1<δ13 C2<δ13 C3),系生物成因烷烃的贡献。而800~1000℃,烷烃碳同位δ13 C值具反序分布特征(δ13 C1>δ13 C2>δ13 C3),系非生物成因烷烃的贡献。

Derenne等(2008)应用固态13 C核磁共振和热解技术测定燧石干酪根的化学结构,获得了占优势的芳烃组分和长链脂肪族烷烃组分(具奇-偶碳数优势),显示了生物成因特征。但要作为生命起源的证据,必须确定干酪根与燧石的同生性。基于Py-GC-MS技术的局限性,亦需要寻找确定其生物成因性的新生物标志物(Bourbin et al.,2012)。

该项研究获得了蛇纹石化橄榄岩中两种来源的有机化合物,一是蛇纹石化期间,在还原和高浓度H2条件下,通过费-托合成反应产生的非生物成因有机化合物。另一是海洋有机质热降解和/或微生物活动残留的有机化合物。但要确定后者与生命演化的相关性和同生性,尚缺乏必要和充分的证据。鉴于蛇纹石化全岩样品的局限性和复杂性,进一步采用GC-MS和HPLC-MS技术,以及Py-GC-MS技术研究蛇纹石化橄榄岩中,可溶有机质和不可溶有机质的分子生物学特征,或许会获得有重要意义的新信息。

3 结论(1)蛇纹石化超基性岩生态环境体系,既含有非生物过程产生的前生命有机质,又可能含有化能生物群落残留的生命有机质,或二种类型有机质兼而有之。

(2)蛇纹石化橄榄岩碳含量甚低(0.18%~1.02%),总有机碳浓度仅有0.01%~0.04%,揭示了橄榄岩蛇纹石化对H2和CH4的贡献。

(3)蛇纹石化橄榄岩的CO2和烷烃同位素组成,揭示了两种成因类型的CO2和烷烃:生物成因的CO2、烷烃和非生物成因的CO2、烷烃。

(4)蛇纹石化橄榄岩中两种来源的有机化合物,一是蛇纹石化期间,在还原和高浓度H2条件下,通过费-托合成反应产生的非生物成因有机化合物。另一是海洋有机质热降解和/或包含微生物活动残留的有机化合物。但要确定后者与生命演化的相关性和同生性,尚缺乏必要和充分的证据。进一步采用GC-MS和HPLC-MS技术,以及Py-GC-MS技术研究蛇纹石化橄榄岩中,可溶有机质和不可溶有机质的分子生物学特征,或许会获得有重要意义的新信息。

致谢:欧阳自远先生对该项研究工作给予了大力支持,谨致深切的谢忱。

| [1] | Abrajano T A, Sturchio N C, Kennedy B M, Lyon G L, Muehlenbachs K, Bohlke J K. 1990. Geochemistry of reduced gas related to serpentinization of the Zambales Ophiolite, Philippines. Applied Geochemistry, 5(5-6):625-630 |

| [2] | Anderson R R, White C M. 1994. Analysis of Fischer-Tropsch by-product waters by gas chromatography. Journal of High Resolution Chromatography, 17(4):245-250 |

| [3] | Bell E A, Boehnke P, Harrison T M, Mao W L. 2015. Potentially biogenic carbon preserved in a 4.1 billion-year-old zircon. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(47):14518-14521 |

| [4] | Berndt M E, Allen D E, Seyfried Jr W E. 1996. Reduction of CO2 during serpentinization of olivine at 300℃ and 500 bar. Geology, 24(4):351-354 |

| [5] | Blank J G, Green S J, Blake D, Valley J W, Kita N T, Treiman A, Dobson P F. 2009. An alkaline spring system within the Del Puerto Ophiolite(California, USA):A Mars analog site. Planetary and Space Science, 57(5-6):533-540 |

| [6] | Bourbin M, Derenne S, Robert F. 2012. Limits in pyrolysis-GC-MS analysis of kerogen isolated from Archean cherts. Organic Geochemistry, 52:32-34 |

| [7] | Bradley A S, Hayes J M, Summons R E. 2009. Extraordinary 13C enrichment of diether lipids at the Lost City Hydrothermal Field indicates a carbon-limited ecosystem. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 73(1):102-118 |

| [8] | Brassell S C, Wardroper A M K, Thomson I D, Maxwell J R, Eglinton G. 1981. Specific acyclic isoprenoids as biological markers of methanogenic bacteria in marine sediments. Nature, 290(5808):693-696 |

| [9] | Brazelton W J, Schrenk M O, Kelley D S, Baross J A. 2006. Methane-and sulfur-metabolizing microbial communities dominate the Lost City Hydrothermal Field ecosystem. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 72(9):6257-6270 |

| [10] | Brocks J J, Summons R E. 2003. Sedimentary hydrocarbons, biomarkers for Early life. In:Elderfield H, Holland H D, Turekian K K, eds. Treatise on geochemistry. Amsterdam, The Netherlands:Elsevier, 8:63-115 |

| [11] | Carter Jr C W, Wolfenden R. 2015. tRNA acceptor stem and anticodon bases form independent codes related to protein folding. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(24):7489-7494 |

| [12] | Charlou J L, Fouquet Y, Bougault H, Donval J P, Etoubleau J, Jean-Baptiste P, Dapoigny A, Appriou P, Rona P A. 1998. Intense CH4 plumes generated by serpentinization of ultramafic rocks at the intersection of the 15°20'N fracture zone and the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 62(13):2323-2333 |

| [13] | Charlou J L, Donval J P, Fouquet Y, Jean-Baptiste P, Holm N. 2002. Geochemistry of high H2 and CH4 vent fluids issuing from ultramafic rocks at the Rainbow hydrothermal field(36°14'N, MAR). Chemical Geology, 191(4):345-359 |

| [14] | Delacour A, Früh-Green G L, Bernasconi S M, Schaeffer P, Kelley D S. 2008a. Carbon geochemistry of serpentinites in the Lost City Hydrothermal System(30°N, MAR). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 72(15):3681-3702 |

| [15] | Delacour A, Früh-Green G L, Bernasconi S M, Schaeffer P, Frank M, Gutjahr M. 2008b. Isotopic constraints on seawater-rock interaction and redox conditions of the gabbroic-dominated IODP Hole 1309D, Atlantis Massif(30°N, MAR). Geophysical Research Abstracts, 10:EGU2008-A-08649 |

| [16] | Derenne S, Robert F, Skrzypczak-Bonduelle A, Gourier D, Binet L, Rouzaud J N. 2008. Molecular evidence for life in the 3.5 billion year old Warrawoona chert. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 272(1-2):476-480 |

| [17] | Edwards K J, Becker K, Colwell F. 2012. The Deep, Dark energy biosphere:Intraterrestrial life on earth. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 40(1):551-568 |

| [18] | Goossens H, de Leeuw J W, Schenck P A, Brassell S C. 1984. Tocopherols as likely precursors of pristane in ancient sediments and crude oils. Nature, 312(5993):440-442 |

| [19] | Grice K, Schouten S, Nissenbaum A, Charrach J, Sinninghe Damsté J S. 1998. Isotopically heavy carbon in the C21 to C25 regular isoprenoids in halite-rich deposits from the Sdom Formation, Dead Sea Basin, Israel. Organic Geochemistry, 28(6):349-359 |

| [20] | Hayatsu R, Studier M H, Oda A, Fuse K, Andkrs E. 1968. Origin of organic matter in early solar system-Ⅱ. Nitrogen compounds. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 32(2):175-190 |

| [21] | Holm N G, Andersson E M. 1998. Organic molecules on the primitive Earth:Hydrothermal systems. In:Brack A, ed. The molecular origins of life:Assembling pieces of the puzzle. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 86-99 |

| [22] | Horita J, Berndt M E. 1999, Abiogenic methane formation and isotopic fractionation under hydrothermal conditions. Science, 285(5430):1055-1057 |

| [23] | Hosgormez H, Etiope G, Yalçin M N. 2008. New evidence for a mixed inorganic and organic origin of the Olympic Chimaera fire(Turkey):A large onshore seepage of abiogenic gas. Geofluids, 8(4):263-273 |

| [24] | Hu G X, Ouyang Z Y, Wang X B, Wen Q B. 1998. Carbon isotopic fractionation in the process of Fischer-Tropsch reaction in primitive solar nebula. Science in China Series D:Earth Sciences, 41(2):202-207 |

| [25] | Kannenberg E L, Poralla K. 1999. Hopanoid biosynthesis and function in bacteria. Naturwissenschaften, 86(4):168-176 |

| [26] | Kelley D S, Früh-Green G L. 1999. Abiogenic methane in deep-seated mid-ocean ridge environments:Insights from stable isotope analyses. Journal of Geophysical Research, 104(B5):10439-10460 |

| [27] | Kelley D S, Karson J A, Früh-Green G L, Yoerger D R, Shank T M, Butterfield D A, Hayes J M, Schrenk M O, Olson E J, Proskurowski G, Jakuba M, Bradley A, Larson B, Ludwig K, Glickson D, Buckman K, Bradley A S, Brazelton W J, Roe K, Elend M J, Delacour A, Bernasconi S M, Lilley M D, Baross J A, Summons R E, Sylva S P. 2005. A serpentinite-hosted ecosystem:The Lost City hydrothermal field. Science, 307(5714):1428-1434 |

| [28] | Ménez B, Pasini V, Brunelli D. 2012. Life in the hydrated suboceanic mantle. Nature Geoscience, 5(2):133-137 |

| [29] | McCollom T M, Ritter G, Simoneit B R T. 1999. Lipid synthesis under hydrothermal conditions by Fischer-Tropsch-type reactions. Origins of Life and Evolution of Biosphere, 29(2):153-166 |

| [30] | McCollom T M, Seewald J S. 2001. A reassessment of the potential for reduction of dissolved CO2 to hydrocarbons during serpentinization of olivine. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 65(21):3769-3778 |

| [31] | McCollom T M, Seewald J S. 2006. Carbon isotope composition of organic compounds produced by abiotic synthesis under hydrothermal conditions. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 243(1-2):74-84 |

| [32] | McCollom T M, Seewald J S. 2007. Abiotic synthesis of organic compounds in deep-sea hydrothermal environments. Chemical Reviews, 107(2):382-401 |

| [33] | McCollom T M, Lollar B S, Lacrampe-Couloume G, Seewald J S. 2010. The influence of carbon source on abiotic organic synthesis and carbon isotope fractionation under hydrothermal conditions. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 74(9):2717-2740 |

| [34] | McCollom T M. 2013. Laboratory simulations of abiotic hydrocarbon formation in Earth's deep subsurface. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 75(1):467-494 |

| [35] | Morrill P L, Kuenen J G, Johnson O J, Suzuki S, Rietze A, Sessions A L, Fogel M L, Nealson K H. 2013. Geochemistry and geobiology of a present-day serpentinization site in California:The Cedars. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 109:222-240 |

| [36] | Oehler D Z, Robert F, Walter M R, Sugitani K, Allwood A, Meibom A, Mostefaoui S, Selo M, Thomen A, Gibson E K. 2009. NanoSIMS:Insights to biogenicity and syngeneity of Archaean carbonaceous structures. Precambrian Research, 173(1-4):70-78 |

| [37] | Oehler D Z, Cady S L. 2014. Biogenicity and syngeneity of organic matter in ancient sedimentary rocks:Recent advances in the search for evidence of past life. Challenges, 5(2):260-283 |

| [38] | Peters K E, Moldowan J M. 1992. The biomarker guide:Interpreting molecular fossils in petroleum and ancient sediments. New Jersey, Englewood Cliffs:Prentice-Hall |

| [39] | Proskurowski G, Lilley M D, Seewald J S, Früh-Green G L, Olson E J, Lupton J E, Sylva S P, Kelley D S. 2008. Abiogenic hydrocarbon production at Lost City hydrothermal field. Science, 319(5863):604-607 |

| [40] | Russell M J, Hall A J, Martin W. 2010. Serpentinization as a source of energy at the origin of life. Geobiology, 8(5):355-371 |

| [41] | Schrenk M O, Brazelton W J, Lang S Q. 2013. Serpentinization, carbon, and deep life. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 75(1):575-606 |

| [42] | Sherwood Lollar B, Westgate T D, Ward J A, Slater G F, Lacrampe-Couloume G. 2002. Abiogenic formation of alkanes in the Earth's crust as a minor source for global hydrocarbon reservoirs. Nature, 16(6880):522-524 |

| [43] | Summons R E, Hallmann C. 2014. Chapter 12.2-Organic geochemical signatures of early life on Earth. In:Turekian K K, Holland H D, eds. Treatise on geochemistry. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands:Elsevier, 12:33-46 |

| [44] | Szponar N, Brazelton W J, Schrenk M O, Bower D M, Steele A, Morrill P L. 2013. Geochemistry of a continental site of serpentinization in the tablelands ophiolite, Gros Morne National Park:A Mars analogue. Icarus, 224(2):286-296 |

| [45] | Ten Haven H L, Deleeuw J W, Sinninghe Damsté J S, Schenk P A, Palmer S E, Zumberge J E. 1988. Application of biological markers in the recognition of paleohypersaline environment. In:Fleet A J, Kelts K, Talbots M R, eds. Lacustrine petroleum source rocks. London:Geological Society Geological Society, 123-130 |

| [46] | Tornabene T G, Langworthy T A, Holzer G, Oró J. 1979. Squalenes, phytanes and other isoprenoids as major neutral lipids of methanogenic and thermoacidophilic "Archaebacteria". Journal of Molecular Evolution, 13(1):73-83 |

| [47] | Volkman J K, Maxwell J R. 1986. Acyclic isoprenoids as biological markers. In:Johns R B, ed. Biological markers in sedimentary record. New York:Elsevier, 1-42 |

| [48] | Wang X B, Guo Z H, Tuo J C, Guo H Y, Li Z X, Zhou S G, Jiang H L, Zeng L W, Zhang M J, Wang L S, Liu C X, Yan H, Li L W, Zhou X F, Wang Y L, Yang H, Wang G. 2009. Abiogenic hydrocarbons in commercial gases from the Songliao Basin, China. Science in China Series D:Earth Sciences, 52(2):213-226 |

| [49] | Wang X B, Ouyang Z Y, Zhuo S G, Zhang M F, Zheng G D, Wang Y L. 2014. Serpentinization, abiogenic organic compounds, and deep life. Science China Earth Sciences, 57(5):878-887 |

| [50] | Wolfenden R, Lewis Jr C A, Yuan Y, Carter Jr C W. 2015. Temperature dependence of amino acid hydrophobicities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(24):7484-7488 |

| [51] | Yoshino D, Hayatsu R, Anders E. 1971. Origin of organic matter in early solar system-Ⅲ. Amino acids:Catalytic synthesis. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 32(9):927-938 |

| [52] | 王先彬. 1989. 稀有气体同位素地球化学和宇宙化学. 北京:科学出版社, 451 |

| [53] | 张明峰,卓胜广,妥进才,吴陈君,孙丽娜,刘艳,李中平,李立武,迟洪兴,王先彬. 2016. 内蒙古温都尔庙蛇纹石化橄榄岩气体组成及成因探讨. 矿物岩石地球化学通报,35(2):255-263 |

2016, Vol. 35

2016, Vol. 35