文章信息

- 具有休眠特征的播散肿瘤细胞体内外研究模型的建立及应用

- Establishment and Application of in vitro and in vivo Model of Disseminated Tumor Cells with Dormancy

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2023, 50(11): 1127-1132

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2023, 50(11): 1127-1132

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2023.23.0585

- 收稿日期: 2023-06-01

- 修回日期: 2023-09-06

2. 200071 上海,上海中医药大学附属市中医医院肿瘤临床医学中心

2. Clinical Oncology Center, Shanghai Municipal Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai 200071, China

癌症严重危害人类健康,给社会和家庭带来了严重的经济负担,其中肺癌是我国死亡人数最高的恶性肿瘤,每年约有超过70万人死于肺癌,而转移是导致肺癌患者死亡的最主要原因[1]。随着影像学检查技术(CT、PET/CT)的推广,使得临床上确诊为早期肺癌患者的数量逐渐升高。按照临床诊疗指南,这些患者常规进行根治性手术,然后基于原发肿瘤组织基因突变检测的结果,辅以化疗或分子靶向治疗,以防止远处转移的发生[2-3]。然而早期肺癌患者术后治疗期间,通常会发生远处转移,其远处转移发生率高达48%~78%[4]。因此,阐明早期肺癌患者根治术后发生转移的原因,进而针对关键环节进行干预,这可能是预防转移并显著提高肺癌患者总体生存的关键。

播散肿瘤细胞(disseminated tumor cells, DTCs)是指外周血中的循环肿瘤细胞(circulating tumor cells, CTCs)外渗,侵入远处靶器官后定植存活下来的肿瘤细胞[5]。越来越多的研究表明,癌症(如肺癌、乳腺癌、前列腺癌等)患者在临床确诊前肿瘤细胞的播散早已发生,在远处的转移靶器官(如对侧肺、脑、肝等)中已存在处于休眠状态的DTCs,并受限于现有的检测技术而未能检出,但通过穿刺已证实骨髓中存在DTCs[6]。正因如此,目前已开展的DTCs研究主要以基础研究为主,其中尤以乳腺癌DTCs的研究最为广泛[7]。这主要归因于乳腺癌的发病人数多,且部分早期患者在术后长达数十年才会发生复发或转移[8]。Hartkopf等研究发现,在早期乳腺癌患者的骨髓中,DTCs检出与局部无复发生存率之间无相关性,但是与较高的肿瘤分级、较大的肿瘤直径和淋巴结阳性相关,且是总生存率的独立预后标志物[9],而Rehulkova等[10]采用qRT-PCR的方式对早期非小细胞肺癌患者的外周血和骨髓中的CTCs/DTCs进行了检测,发现术后患者CTCs/DTCs的存在与更差的生存率相关。由于休眠的DTCs能够在化疗和分子靶向治疗中存活,其增殖是导致临床转移发生和患者死亡的关键,然而目前临床上仍缺乏特异性针对休眠DTCs的治疗药物[5]。因此,建立符合临床特征的休眠DTCs体内外研究模型,并进行休眠机制和药物开发研究,将有望研制出特异性靶向休眠DTCs的治疗药物,进而突破现有肺癌临床疗效提高的瓶颈。本文就具有休眠特征的DTCs体内外研究模型的建立方法,及其应用的研究进展进行综述。

1 具有休眠特征的播散肿瘤细胞体外研究模型的建立为了建立可反映体内情况的体外研究模型,首先需要制备具有休眠特征的肿瘤细胞。休眠肿瘤细胞的体外制备方法主要包括细胞生长接触抑制、营养剥夺与乏氧、药物诱导、3D培养和肿瘤细胞与免疫细胞共培养等模型[11]。

1.1 休眠肿瘤细胞的体外制备方法 1.1.1 细胞生长接触抑制模型将肿瘤细胞接种到普通2D培养皿内,由于细胞与细胞之间的接触可以抑制增殖,当细胞密度达到足够高时,肿瘤细胞会自动进入休眠状态[12]。然而该模型并非适用于所有的肿瘤细胞,如前列腺癌LNCaP细胞、胰腺癌MIA PaCa-2细胞、宫颈癌HeLa细胞和胶质瘤U251细胞等,其在细胞密度足够高时,仍具有较高的增殖活性[13-14]。

1.1.2 营养剥夺模型通过剥夺培养基中的血清,也可诱导肿瘤细胞进入休眠状态。Feng等研究发现,通过连续7天剥夺血清(无血清或0.05%~0.2%的低血清培养)培养肿瘤细胞,可诱导前列腺癌细胞进入静止期[15]。此外,Malladi等采用低有丝分裂原的培养基培养HCC1954-LCC1细胞,也可诱导细胞进入休眠状态,休眠相关基因的表达显著上调,并且P-ERK/P-p38的比率显著降低[16]。

1.1.3 乏氧培养模型通过将肿瘤细胞置于乏氧培养箱内培养或采用浓度为100~500 μmol/L的CoCl2连续处理细胞,使肿瘤细胞在0.1%或1%氧气浓度下培养5~14天,可诱导肿瘤细胞进入休眠状态[17]。

1.1.4 药物诱导的肿瘤休眠模型主要利用化疗药物以活跃增殖的癌细胞作为靶点,当用化疗药物(顺铂、紫杉醇、吉西他滨和阿霉素等)长时间连续处理肿瘤细胞后,剩余存活的癌细胞几乎都处于休眠状态[18]。此外,Najmi等研究发现,将肿瘤细胞接种到涂有纤维链接蛋白的细胞培养板上培养,并向培养基中添加FGF2时,肿瘤细胞会自动进入休眠状态[11]。而Di Martino等研究发现,Ⅲ型胶原蛋白具有诱导并维持播散性肝癌细胞处于休眠状态的作用[19]。

1.1.5 3D培养模型采用天然(Ⅰ型胶原和透明质酸)或生物合成(硅聚乙烯和聚己内酯水凝胶)的材料,通过制备水凝胶,置于这些结构内生长的肿瘤细胞会表现出不同程度的休眠[20-21]。Keeratichamroen等研究发现,将肺癌A549细胞置于半固态的Matrigel中培养时,细胞会进入休眠状态[22]。此外,将肿瘤细胞置于超低吸附的细胞培养板内,漂浮在培养基中的3D球状体细胞簇也具有肿瘤休眠的特征[23]。

1.1.6 肿瘤细胞和免疫细胞共培养模型Li等研究发现,当用成骨细胞和前列腺癌细胞进行共培养时,成骨细胞中的蛋白激酶D1(PKD1)可通过激活CREB1诱导前列腺癌PC-3和DU145细胞进入休眠状态[24]。Pradhan等通过共培养实验研究发现,人间充质干细胞(hMSCs)可促进ER+乳腺癌细胞的生长,而新生儿成骨细胞(hFOB)却可诱导ER+乳腺癌细胞发生休眠[25]。

总之,通过以上方法,都可制备并获得具有休眠特性的肿瘤细胞,基于这些细胞可用于构建具有休眠特征的播散性肿瘤细胞体外研究模型。

1.2 休眠播散肿瘤细胞的体外造模为模拟肿瘤转移级联过程,在体外可通过悬浮培养的方式获得具有休眠特性的肿瘤细胞簇,然后将细胞簇消化成单细胞,并将少量的肿瘤细胞接种到提前用Matrigel胶包被的细胞培养板中,即可建立具有休眠特征的DTCs体外研究模型。此外,为进一步模拟体内不同转移靶器官的肿瘤免疫微环境状态,还可向培养板中添加不同类型的细胞与休眠的DTCs进行共培养,如成骨细胞(骨)、肝星状细胞(肝)和肺泡细胞(肺)等[24, 26],以及添加细胞外基质(ECM),如胶原蛋白(Ⅲ型胶原蛋白)、纤维链接蛋白和层粘连蛋白等[19, 27-28]。通过以上方法,即可在体外建立具有休眠特征的DTCs研究模型。

2 具有休眠特征的播散肿瘤细胞体内研究模型的建立播散到转移靶器官的肿瘤细胞,由于受到免疫监视、细胞外基质和血管生成等因素的影响,存活下来的DTCs通常以休眠的形式潜伏在患者体内,以待免疫抑制微环境的形成,进而从休眠激活为增殖状态,最终造成临床转移的发生[5]。目前,体内的转移性休眠研究模型的造模方法主要包括以下几种。

2.1 采用具有转移性休眠特征的肿瘤细胞系通过在小鼠体内连续筛选构建具有转移性休眠的肿瘤细胞系。Aslakson等采用小鼠乳腺癌4T1细胞,通过连续静脉注射转移细胞,并从小鼠肺脏中分离得到Thioguanine和Ouabain耐药的4T07细胞系[29],经研究发现4T1细胞转移到小鼠的肺脏和肝脏后,可形成大转移灶;而4T07细胞却以转移性休眠的形式长期潜伏在小鼠体内。当耗竭小鼠体内的NK细胞或CD8+ T细胞时,处于休眠状态下的4T07细胞会进入增殖期,最终形成大转移灶[26, 30]。此外,Morris等也在体外建立了小鼠乳腺癌D2.0R和D2A1细胞系[31]。D2.0R和D2A1细胞在体外的2D培养条件下时,其增殖活性并无明显差异,然而在3D培养、共培养模型和小鼠体内转移模型中,D2.0R和D2A1细胞却存在着明显的差异,D2A1细胞可在小鼠的肺脏和肝脏中形成大转移灶,而D2.0R细胞在相同的转移靶器官中,却以休眠的形式持续性存在[32]。以上研究结果表明,4T07细胞和D2.0R细胞可用于构建具有休眠特征的DTCs体内研究模型。

2.2 条件性诱导DTCs进入休眠状态通过操控肿瘤细胞的休眠与增殖开关,即可条件性诱导靶器官中的DTCs进入休眠状态。Knopeke等研究发现,在前列腺癌和卵巢癌细胞中,通过激活MKK4,可诱导播散到靶器官中的肿瘤细胞进入休眠状态,而一旦MKK4发生失活时,休眠的肿瘤细胞会进入增殖期,进而形成大转移灶[33]。因此,通过构建一种可诱导的四环素操纵子调控系统Tet-On,特异性激活前列腺癌或卵巢癌细胞中的MKK4基因,即可在小鼠体内建立具有休眠特征的DTCs体内研究模型。

2.3 接种休眠肿瘤细胞通过体外诱导肿瘤细胞进入休眠状态后,将具有休眠特征的肿瘤细胞接种到小鼠体内。进入靶器官后的休眠DTCs,一旦适应了靶器官的微环境,并建立了肿瘤免疫抑制微环境之后,会自动地从休眠激活为增殖状态,进而形成大转移灶。该模型的缺点是DTCs的休眠时长不可控,转移性休眠的时长偏短,然而这也更符合一些癌种的临床实际转移特征,如肺癌。

总之,通过上述方法,可在小鼠体内构建长期稳定的转移性休眠DTCs研究模型。基于上述模型,可研究免疫细胞与DTCs休眠重激活之间的关系以及筛选可靶向杀伤休眠DTCs的化合物。

3 具有休眠特征的播散肿瘤细胞体内外研究模型的应用构建具有休眠特征的DTCs体内外研究模型,可用于研究DTCs休眠重激活的调控“开关”机制、休眠DTCs的存活机制、休眠DTCs的代谢特征、休眠DTCs与微环境之间的互作关系、休眠DTCs逃避免疫监视的机制等[34-35]。通过寻找到调控DTCs休眠与存活的关键作用靶点,并以此进行抗肿瘤转移药物的筛选,将可能寻找到维持DTCs休眠或完全根除休眠DTCs的治疗药物[36]。

DTCs的增殖状态与转移靶器官的微环境密切相关。已有研究表明,肝脏中的NK细胞可通过分泌INF-γ来诱导乳腺癌DTCs进入休眠状态[26];转移至大脑中的乳腺癌DTCs同样受到NK细胞以及星形胶质细胞的调控而处于休眠状态[27];在肺脏中,表型为CD39+PD-1+CD8+ T细胞是诱导乳腺癌DTCs休眠的主要效应细胞[30];转移到肌肉中的乳腺癌细胞则由于高氧化应激而处于休眠状态[37];在骨骼中,NG2+/Nestin+的间充质干细胞可维持乳腺癌细胞处于休眠状态[38]。此外,骨髓中的成骨细胞也是诱导DTCs休眠的主要效应细胞,通过释放BMP7、Wnt5a和OPN等诱导肿瘤细胞休眠;而破骨细胞却可通过分泌MMP-9和TGF-β1等[39]重新激活休眠的DTCs。上述研究结果提示,免疫微环境是决定DTCs增殖状态和最终转移是否发生的重要因素。

课题组前期提出了癌症(肺癌)转移亚临床阶段的核心病机“正虚伏毒”理论[40],主要指早期癌症患者术后的外周血和转移靶器官中,已经存在处于静止期的CTCs和DTCs,即中医所认为的“伏毒”,一旦患者的免疫功能发生紊乱,导致靶器官中处于静止期的DTCs增殖激活,最终造成临床转移事件的发生。据此提出清除靶器官中的“伏毒”—DTCs,以防止肺癌转移进而提高患者生存的治疗策略。为验证该理论,课题组前期在体外建立了人源肺癌循环肿瘤细胞系(CTC-TJH-01)[41]。研究发现悬浮状态下的CTC-TJH-01细胞具有成簇、肿瘤休眠和干细胞表型增强等特性,且接种到小鼠体内后,皮下成瘤时间显著延长,并在小鼠的肺脏中发现了一部分长期处于休眠状态的DTCs。因此,开发靶向清除靶器官中休眠DTCs的药物,并将其与现有的分子靶向药物和免疫靶向药物相联合,将有效防止肺癌转移的发生,进而改善患者的生存[5, 42]。

4 展望早期癌症患者在出现临床可检出的转移之前,可能有数年(甚至几十年)的时间处于无临床症状的疾病状态,这种现象的根源是由于早期术后患者体内仍残留有DTCs,它们以休眠的状态潜伏在遥远的靶器官中,只待数年甚至几十年后被唤醒并引发转移[43]。尽管休眠的DTCs增殖激活是造成肿瘤转移发生的关键环节,然而我们对患者体内休眠DTCs的认识仍有限,这主要是由于目前缺乏追踪单个或一小群休眠DTCs的技术,以及收集和分析处于转移阶段的患者靶器官的伦理和技术问题。然而骨髓却是一个例外,这是一些癌症常见的转移部位,从骨髓组织中分离出单个的休眠DTCs,通过对其进行分析,临床证实了无疾病证据的患者体内仍存在休眠的DTCs[25]。针对这一部分患者,急需建立转移风险评估和疗效预测模型,用于对患者进行分层管理,并指导临床医生的用药。为此,我们课题组基于外周免疫评分等,建立了多个肺癌患者的转移风险和疗效预测模型,并提出了通过靶向可检测的CTCs,以此来治疗不可检出的DTCs和转移[44-46]。

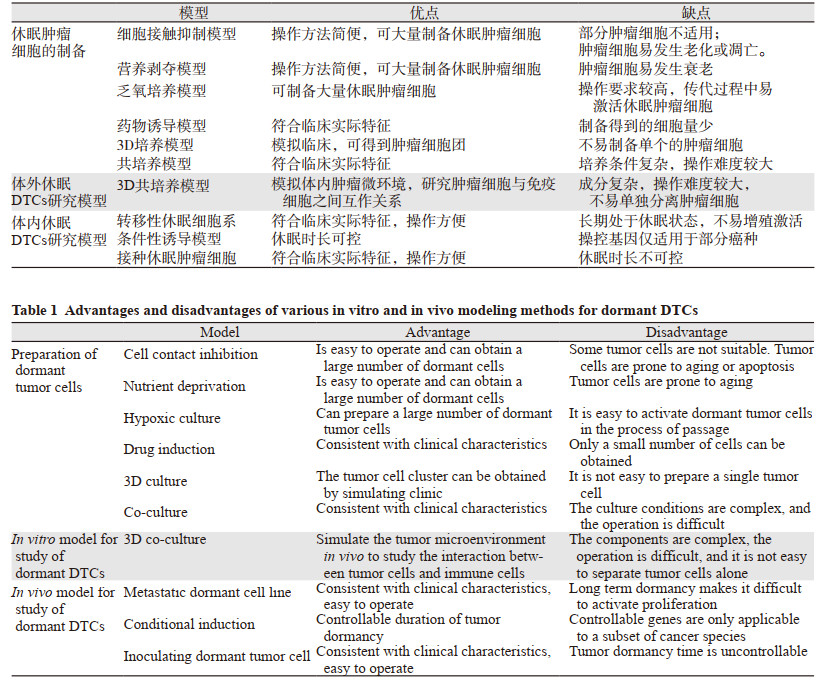

针对靶器官中的DTCs,我们需要知道DTCs是如何进入休眠状态的,是什么因素导致休眠DTCs的增殖激活,以及如何锁定休眠状态的DTCs,只有如此,才能够寻找到维持DTCs处于休眠状态,或完全根除休眠DTCs的治疗药物和干预策略[36]。为此,需在体内外建立可模拟临床实际特征的DTCs研究模型,我们对这些模型进行了总结(如表 1),其中3D共培养模型,由于其更能模拟临床肿瘤细胞所处的微环境,越来越受到研究者的重视并使用。体内的转移性休眠细胞系,也仅有部分的癌种(如乳腺癌)被建立成功,这限制了其他癌种的研究。

总之,构建具有休眠特征的DTCs体内外研究模型,并以此作为抗肿瘤转移药物的筛选平台,将有可能促进抗肿瘤转移药物的临床转化效率,对肿瘤转移的防治和患者临床疗效的提高具有重大意义。

利益冲突声明:

所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

作者贡献:

阙祖俊:论文撰写

刘佳君:论文修改与投稿

田建辉:指导论文思路与设计

| [1] |

Wang Y, Yan Q, Fan C, et al. Overview and countermeasures of cancer burden in China[J]. Sci China Life Sci, 2023, 1-12. |

| [2] |

郑荣寿, 张思维, 孙可欣, 等. 2016年中国恶性肿瘤流行情况分析[J]. 中华肿瘤杂志, 2023, 45(3): 212-220. [Zheng RS, Zhang SW, Sun KX, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2016[J]. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi, 2023, 45(3): 212-220.] |

| [3] |

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: Globocan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3): 209-249. DOI:10.3322/caac.21660 |

| [4] |

Choi PJ, Jeong SS, Yoon SS. Prediction and prognostic factors of post-recurrence survival in recurred patients with early-stage NSCLC who underwent complete resection[J]. J Thorac Dis, 2016, 8(1): 152-160. |

| [5] |

Crunkhorn S. Eliminating disseminated tumour cells[J]. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2019, 18(3): 174. |

| [6] |

Crist SB, Ghajar CM. When a house is not a home: A survey of antimetastatic niches and potential mechanisms of disseminated tumor cell suppression[J]. Annu Rev Pathol, 2021, 16: 409-432. DOI:10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012419-032647 |

| [7] |

Elkholi IE, Lalonde A, Park M, et al. Breast cancer metastatic dormancy and relapse: An enigma of microenvironment(s)[J]. Cancer Res, 2022, 82(24): 4497-4510. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-22-1902 |

| [8] |

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, et al. Cancer statistics, 2023[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2023, 73(1): 17-48. DOI:10.3322/caac.21763 |

| [9] |

Hartkopf AD, Brucker SY, Taran FA, et al. Disseminated tumour cells from the bone marrow of early breast cancer patients: Results from an international pooled analysis[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2021, 154: 128-137. DOI:10.1016/j.ejca.2021.06.028 |

| [10] |

Rehulkova A, Chudacek J, Prokopova A, et al. Clinical and prognostic significance of detecting CEA, EGFR, LunX, c-met and EpCAM mRNA-positive cells in the peripheral blood, tumor-draining blood and bone marrow of non-small cell lung cancer patients[J]. Transl Lung Cancer Res, 2023, 12(5): 1034-1050. DOI:10.21037/tlcr-22-801 |

| [11] |

Najmi S, Korah R, Chandra R, et al. Flavopiridol blocks integrin-mediated survival in dormant breast cancer cells[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2005, 11(5): 2038-2046. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1083 |

| [12] |

Bi L, Xie C, Yao M, et al. The histone chaperone complex FACT promotes proliferative switch of G(0) cancer cells[J]. Int J Cancer, 2019, 145(1): 164-178. DOI:10.1002/ijc.32065 |

| [13] |

Pause A, Lee S, Lonergan KM, et al. The von hippel-lindau tumor suppressor gene is required for cell cycle exit upon serum withdrawal[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1998, 95(3): 993-998. DOI:10.1073/pnas.95.3.993 |

| [14] |

Fuse T, Tanikawa M, Nakanishi M, et al. P27kip1 expression by contact inhibition as a prognostic index of human glioma[J]. J Neurochem, 2000, 74(4): 1393-1399. DOI:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0741393.x |

| [15] |

Feng J, Xi Z, Jiang X, et al. Saikosaponin a enhances docetaxel efficacy by selectively inducing death of dormant prostate cancer cells through excessive autophagy[J]. Cancer Lett, 2023, 554: 216011. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2022.216011 |

| [16] |

Malladi S, Macalinao DG, Jin X, et al. Metastatic latency and immune evasion through autocrine inhibition of Wnt[J]. Cell, 2016, 165(1): 45-60. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.025 |

| [17] |

Lee HR, Leslie F, Azarin SM. A facile in vitro platform to study cancer cell dormancy under hypoxic microenvironments using cocl2[J]. J Biol Eng, 2018, 12: 12. DOI:10.1186/s13036-018-0106-7 |

| [18] |

Li S, Kennedy M, Payne S, et al. Model of tumor dormancy/recurrence after short-term chemotherapy[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(5): e98021. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0098021 |

| [19] |

Di Martino JS, Nobre AR, Mondal C, et al. A tumor-derived type Ⅲ collagen-rich ecm niche regulates tumor cell dormancy[J]. Nat Cancer, 2022, 3(1): 90-107. |

| [20] |

Wang K, Kievit FM, Erickson AE, et al. Culture on 3D chitosan-hyaluronic acid scaffolds enhances stem cell marker expression and drug resistance in human glioblastoma cancer stem cells[J]. Adv Healthc Mater, 2016, 5(24): 3173-3181. DOI:10.1002/adhm.201600684 |

| [21] |

Fang JY, Tan SJ, Wu YC, et al. From competency to dormancy: A 3D model to study cancer cells and drug responsiveness[J]. J Transl Med, 2016, 14: 38. DOI:10.1186/s12967-016-0798-8 |

| [22] |

Keeratichamroen S, Lirdprapamongkol K, Svasti J. Mechanism of ecm-induced dormancy and chemoresistance in A549 human lung carcinoma cells[J]. Oncol Rep, 2018, 39(4): 1765-1774. |

| [23] |

Zhang Z, Xu Y. FZD7 accelerates hepatic metastases in pancreatic cancer by strengthening EMT and stemness associated with TGF-Beta/SMAD3 signaling[J]. Mol Med, 2022, 28(1): 82. DOI:10.1186/s10020-022-00509-1 |

| [24] |

Li G, Fan M, Zheng Z, et al. Osteoblastic protein kinase D1 contributes to the prostate cancer cells dormancy via GAS6-circadian clock signaling[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res, 2022, 1869(9): 119296. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2022.119296 |

| [25] |

Pradhan L, Moore D, Ovadia EM, et al. Dynamic bioinspired coculture model for probing ER(+) breast cancer dormancy in the bone marrow niche[J]. Sci Adv, 2023, 9(10): eade3186. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.ade3186 |

| [26] |

Correia AL, Guimaraes JC, Auf der Maur P, et al. Hepatic stellate cells suppress NK cell-sustained breast cancer dormancy[J]. Nature, 2021, 594(7864): 566-571. DOI:10.1038/s41586-021-03614-z |

| [27] |

Dai J, Cimino PJ, Gouin KH, et al. Astrocytic laminin-211 drives disseminated breast tumor cell dormancy in brain[J]. Nat Cancer, 2022, 3(1): 25-42. |

| [28] |

Mukherjee A, Bravo-Cordero JJ. Regulation of dormancy during tumor dissemination: The role of the ECM[J]. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 2023, 42(1): 99-112. DOI:10.1007/s10555-023-10094-2 |

| [29] |

Aslakson CJ, Miller FR. Selective events in the metastatic process defined by analysis of the sequential dissemination of subpopulations of a mouse mammary tumor[J]. Cancer Res, 1992, 52(6): 1399-1405. |

| [30] |

Tallón de Lara P, Castañón H, Vermeer M, et al. CD39(+)PD-1(+)CD8(+) T cells mediate metastatic dormancy in breast cancer[J]. Nat Commun, 2021, 12(1): 769. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-21045-2 |

| [31] |

Morris VL, Koop S, MacDonald IC, et al. Mammary carcinoma cell lines of high and low metastatic potential differ not in extravasation but in subsequent migration and growth[J]. Clin Exp Metastasis, 1994, 12(6): 357-367. DOI:10.1007/BF01755879 |

| [32] |

Barkan D, Kleinman H, Simmons JL, et al. Inhibition of metastatic outgrowth from single dormant tumor cells by targeting the cytoskeleton[J]. Cancer Res, 2008, 68(15): 6241-6250. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6849 |

| [33] |

Knopeke MT, Ritschdorff ET, Clark R, et al. Building on the foundation of daring hypotheses: Using the mkk4 metastasis suppressor to develop models of dormancy and metastatic colonization[J]. FEBS Lett, 2011, 585(20): 3159-3165. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2011.09.007 |

| [34] |

Borriello L, Coste A, Traub B, et al. Primary tumor associated macrophages activate programs of invasion and dormancy in disseminating tumor cells[J]. Nat Commun, 2022, 13(1): 626. DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-28076-3 |

| [35] |

Mohme M, Riethdorf S, Pantel K. Circulating and disseminated tumour cells - mechanisms of immune surveillance and escape[J]. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2017, 14(3): 155-167. DOI:10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.144 |

| [36] |

Sauer S, Reed DR, Ihnat M, et al. Innovative approaches in the battle against cancer recurrence: Novel strategies to combat dormant disseminated tumor cells[J]. Front Oncol, 2021, 11: 659963. DOI:10.3389/fonc.2021.659963 |

| [37] |

Crist SB, Nemkov T, Dumpit RF, et al. Unchecked oxidative stress in skeletal muscle prevents outgrowth of disseminated tumour cells[J]. Nat Cell Biol, 2022, 24(4): 538-553. DOI:10.1038/s41556-022-00881-4 |

| [38] |

Nobre AR, Risson E, Singh DK, et al. Bone marrow NG2(+)/Nestin(+) mesenchymal stem cells drive DTC dormancy via TGFbeta2[J]. Nat Cancer, 2021, 2(3): 327-339. DOI:10.1038/s43018-021-00179-8 |

| [39] |

Dai R, Liu M, Xiang X, et al. Osteoblasts and osteoclasts: An important switch of tumour cell dormancy during bone metastasis[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2022, 41(1): 316. DOI:10.1186/s13046-022-02520-0 |

| [40] |

田建辉, 罗斌, 阙祖俊, 等. 癌症转移亚临床阶段核心病机"正虚伏毒"学说[J]. 上海中医药杂志, 2021, 55(10): 1-3, 13. [Tian JH, Luo B, Que ZJ, et al. Theory of "hidden toxicity due to vital qi deficiency" as core pathogenesis for subclinical stage of cancer metastasis[J]. Shanghai Zhong Yi Yao Za Zhi, 2021, 55(10): 1-3, 13.] |

| [41] |

Que Z, Luo B, Zhou Z, et al. Establishment and characterization of a patient-derived circulating lung tumor cell line in vitro and in vivo[J]. Cancer Cell Int, 2019, 19: 21. DOI:10.1186/s12935-019-0735-z |

| [42] |

Ring A, Spataro M, Wicki A, et al. Clinical and biological aspects of disseminated tumor cells and dormancy in breast cancer[J]. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2022, 10: 929893. DOI:10.3389/fcell.2022.929893 |

| [43] |

König T, Dogan S, Höhn AK, et al. Multi-parameter analysis of disseminated tumor cells (DTCs) in early breast cancer patients with hormone-receptor-positive tumors[J]. Cancers (Basel), 2023, 15(3): 568. DOI:10.3390/cancers15030568 |

| [44] |

罗添乐, 周奕阳, 杨蕴, 等. 外周免疫评分对经中医药治疗的非小细胞肺癌患者预后的影响及相关预测模型的构建[J]. 中医杂志, 2022, 63(1): 35-42. [Luo TL, Zhou YY, Yang Y, et al. The Influence of the Peripheral Immune Score on the Prognosis of Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Treated by Traditional Chinese Medicine and the Construction of the Related Prediction Model[J]. Zhong Yi Za Zhi, 2022, 63(1): 35-42.] |

| [45] |

Luo B, Yang M, Han Z, et al. Establishment of a nomogram-based prognostic model (lasso-cox regression) for predicting progression-free survival of primary non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with adjuvant chinese herbal medicines therapy: A retrospective study of case series[J]. Front Oncol, 2022, 12: 882278. DOI:10.3389/fonc.2022.882278 |

| [46] |

Que Z, Tian J. New strategy for antimetastatic treatment of lung cancer: A hypothesis based on circulating tumour cells[J]. Cancer Cell Int, 2022, 22(1): 356. DOI:10.1186/s12935-022-02782-w |

2023, Vol. 50

2023, Vol. 50