文章信息

- CAR-T细胞免疫在胸部恶性肿瘤中的研究进展

- Progress of Chimeric Antigen Receptor Gene Modified-T Cell Immunotherapy for Thoracic Malignancies

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2023, 50(10): 1010-1014

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2023, 50(10): 1010-1014

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2023.23.0144

- 收稿日期: 2023-02-20

- 修回日期: 2023-06-21

2. 650101 昆明,昆明医科大学第二附属医院重症监护病房

2. Department of SICU, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Kunming Medical University, Kunming 650101, China

胸部恶性肿瘤主要包括肺癌、乳腺癌、食管癌、胸膜间皮瘤和胸腺瘤等,是导致肿瘤死亡和阻碍全球平均寿命提升的主要原因之一[1]。根据2020年全球肿瘤数据统计,胸部恶性肿瘤新发病例5 103 160例,死亡3 052 494例[2],分别占全球肿瘤新发病例和死亡病例的26.45%和30.63%。当前,临床上胸部恶性肿瘤的治疗方法主要有外科减瘤术、化疗、分子靶向治疗等,但这些治疗策略都具有一定的局限性。因此,寻求新的安全有效治疗方法以缓解胸部恶性肿瘤进展和有效延长患者生存期是临床亟待解决的问题。嵌合抗原受体基因修饰T(CAR-T)细胞疗法被认为是治疗恶性肿瘤的一种安全、有效的免疫疗法[3]。目前,CAR-T细胞靶向CD19对药物耐受B淋巴细胞恶性肿瘤具有长效缓解作用,在复发和难治性急性B淋巴细胞白血病和非霍奇金淋巴瘤的患者中,治愈率约为85%[4]。重要的是,有研究正在验证CAR-T细胞免疫疗法在胸部恶性肿瘤中的可行性和安全性[5]。为此,本文综述了CAR-T细胞用于胸部恶性肿瘤治疗的研究进展,包括CAR-T细胞结构、分类以及靶抗原选择,同时也分析了CAR-T细胞免疫治疗在胸部恶性肿瘤中面临的挑战和未来前景,旨在为胸部恶性肿瘤免疫治疗的临床试验设计和治疗提供新的思路。

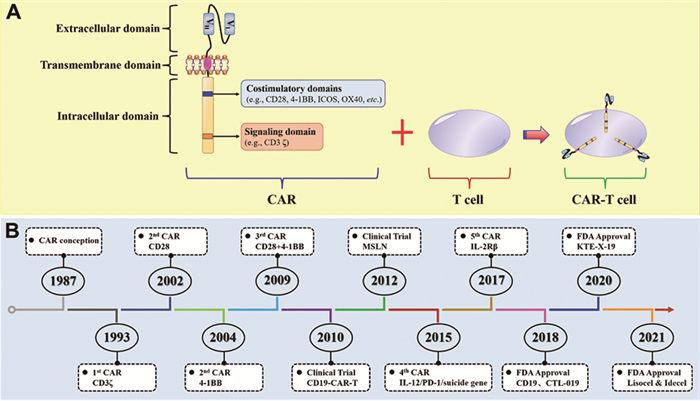

1 CAR-T细胞生物学特征 1.1 CAR-T细胞的结构CAR是一种工程化的合成受体,包含细胞外抗原结合域、细胞外间隔/铰链序列、跨膜结构域和细胞内信号转导结构,见图 1A。细胞外抗原结合域通常是单链可变片段(scFv),包含重链可变区域(VH)和轻链可变区域(VL);其功能主要是识别肿瘤相关抗原,正由于scFv的存在,所以CAR才能特异性地与靶细胞结合,确保了T细胞杀伤作用的特异性。细胞外间隔/铰链序列通常是CD3、CD8或CD28的跨膜区,其主要功能是连接细胞外区域与细胞内区域,通过调节细胞外间隔/铰链序列的长度来优化CAR-T细胞与靶向肿瘤之间的距离,以进行CAR信号转导。细胞内信号转导结构主要包括刺激因子CD3ζ和其他共刺激因子,主要功能是激活T细胞、促进T细胞增殖和延长T细胞周期。

|

| 图 1 CAR-T细胞结构(A)及发展历程(B) Figure 1 Structure (A) and development (B) of CAR-T cells |

根据细胞内信号转导结构的不同,CAR-T细胞已经发展到了第五代和5款FDA批注的CAR-T产品,见图 1B,第五代CARs正处于测试阶段。第一代CAR-T细胞的细胞内信号转导结构域仅包含CD3ζ结构与细胞外的scFv结合修饰后激活T细胞,所以第一代CAR-T细胞的存活时间较短,激活T细胞的能力较弱。为了弥补第一代CARs细胞的不足,第二代CARs增加了共刺激因子以增强T细胞的增殖能力。第三代CARs包含CD3ζ和两个共刺激因子,能有效提升其对肿瘤细胞的杀伤能力。第四代CAR-T细胞又称为TRUCK T细胞,含有一个活化T细胞核因子(NFAT)转录相应元件,可以使CAR-T细胞在肿瘤区域分泌特定的细胞因子,从而修饰肿瘤微环境,有助于实体瘤的免疫治疗。第五代CARs包含一个IL-2受体β片段(IL-2Rβ)。IL-2Rβ替代了OX-40/CD27,且能够介导酪氨酸激酶的产生、信号转导因子和转录激活因子-3/5的活化,但第五代CARs的有效性和安全性正处于验证阶段。

2 CAR-T细胞治疗胸部恶性肿瘤中的靶抗原以往研究表明,CAR-T细胞免疫疗法在胸部恶性肿瘤中的核心问题是选择理想的肿瘤相关抗原(TAA)。理想的TAA是指其在肿瘤细胞中特异性高表达,但在正常组织中不表达或低表达,主要是TAA能使CAR-T细胞触发肿瘤特异性免疫反应,且避免正常组织反应。然而,CAR-T细胞免疫治疗在包括胸部恶性肿瘤在内的实体瘤中,很难获得在血液恶性肿瘤中疗效较为显著的TAA。根据以往研究和早期临床试验,本文总结了胸部恶性肿瘤潜在的TAA,并对其中9种CAR-T细胞的潜在靶抗原进行了描述。

2.1 B7-H3B7-H3作为肿瘤免疫治疗的一个分子靶点,在多种实体瘤中高表达[6]。以往研究表明,超表达B7-H3能够抑制T细胞活性、增殖和细胞因子分泌[7]。临床研究表明,靶向B7-H3的CAR-T细胞实体瘤[8]中表现出较好的抗肿瘤活性。此外,3项临床试验也正在验证靶向B7-H3的CAR-T细胞治疗胸部恶性肿瘤的安全性、耐受性和可行性(NCT05341492、NCT04864821和NCT03198052)。

2.2 CEACEA是一种糖蛋白,其表达量与肿瘤发生呈正相关[9]。TCGA数据库分析显示,在胸部恶性肿瘤中CEA高表达,且高表达CEA的患者总生存期更短。以往研究证实,CEA可作为肺癌治疗预后的有效肿瘤标志物[10]。最新研究也证实,抗CEA-CAR-T细胞在CEA阳性实体瘤患者中显示出较好的抗肿瘤作用,且未出现细胞因子释放综合征[11]。此外,有2项临床试验正在对靶向CEA的CAR-T细胞治疗胸部恶性肿瘤的安全性和有效性进行验证(NCT02349724和NCT04348643)。

2.3 EGFR多项研究证实,EGFR在胸部恶性肿瘤中高表达,并与肿瘤血管生成、转移和复发相关[12]。Xia等[13]研究证实,靶向EGFR的CAR-T细胞对三阴性乳腺癌细胞增殖活力具有特异性抑制作用。临床试验(NCT01869166)表明,抗EGFR-CAR-T细胞治疗EGFR阳性复发或耐药的非小细胞肺癌患者后,没有患者出现严重的不良反应,且2例患者部分缓解,5例患者病情稳定2~8个月。

2.4 成纤维活化蛋白已有文献证实,超表达成纤维活化蛋白(FAP)有助于肿瘤细胞增殖、侵袭和血管生成,且可作为多种肿瘤早期诊断的新靶点[14]。一项Ⅰ期临床试验证实,靶向FAP的CD8+T细胞能抑制FAP阳性胸膜间皮瘤移植瘤体生长,并延长移植小鼠的生存期[15]。

2.5 HER2HER2是一种能够促进癌细胞增殖、侵袭和血管生成的促癌基因[16]。重要的是,靶向HER2的CAR-T细胞能够显著抑制HER2阳性乳腺癌细胞和曲妥珠单抗耐药乳腺癌细胞的增殖活力[17]。同时,抗HER2-CAR-T细胞对异种移植瘤小鼠食管癌细胞增殖活力具有抑制作用,并减少促炎因子的释放[18]。

2.6 间皮素在胸部恶性肿瘤中,高表达间皮素(MSLN)与患者高侵袭性和不良预后相关[19],且其可作为胸膜间皮瘤和肺癌的诊断和治疗靶点[20]。体外实验表明,抗MSLN-CAR-T细胞能够特异性杀死多种肿瘤细胞[21]。一项Ⅰ期临床试验(NCT01583686)表明,抗MSLN-CAR-T细胞治疗转移性肿瘤后,40%(6/15)的患者出现严重不良反应(包括贫血、血小板减少、低氧血症和淋巴细胞减少),只有1例患者在3.5个月的观察期内获得病情稳定。

2.7 MUC1MUC1是一种促进肿瘤细胞黏附和转移的跨膜蛋白,并在包括胸部肿瘤在内的多种实体瘤中高表达[22-23]。也有研究证实,MUC1是实体瘤免疫治疗的潜在靶点[24]。重要的是,已有6项临床试验正在验证抗MUC1-CAR-T细胞治疗胸部恶性肿瘤的安全性和有效性(NCT03179007、NCT02587689、NCT03198052、NCT03706326、NCT03525782和NCT05239143)。

2.8 PD-L1PD-L1作为一种重要的免疫检查点,在胸部恶性肿瘤中高表达[25]。体内试验证实,靶向PD-L1的CAR-T细胞对多种实体瘤具有显著抑制作用[26]。同时,已有3项临床试验正在对靶向PD-L1的CAR-T细胞治疗胸部恶性肿瘤的安全性和有效性进行评估(NCT03060343、NCT04556669和NCT04684459)。

2.9 ROR1以往研究表明,ROR1在三阴性乳腺癌、肺癌、卵巢癌等肿瘤中高表达,但在正常组织中低表达[27]。同时,抗ROR1-CAR-T细胞表现出的抗肿瘤活性同抗CD19-CAR-T细胞治疗淋巴细胞瘤的疗效相当[28]。此外,一项临床试验(NCT02706392)显示,抗ROR1-CAR-T细胞治疗30例晚期胸部恶性肿瘤患者中至少有6例患者没有出现剂量限制性毒性。

3 胸部恶性肿瘤CAR-T细胞免疫疗法面临的挑战与策略目前,CAR-T细胞免疫疗法应用于胸部恶性肿瘤治疗仍处于早期探索阶段,大部分的临床试验进展相对缓慢,还未取得令人满意的效果。同时,CAR-T细胞治疗胸部恶性肿瘤存在以下几种主要挑战,包括靶抗原异质性与脱靶毒性、肿瘤免疫微环境抑制、细胞因子释放综合征、神经毒性。

3.1 靶抗原异质性与脱靶毒性实体瘤CAR-T细胞治疗最主要的问题是缺乏理想的TAA,这严重限制了CAR-T细胞在实体瘤中的治疗效果。同时,挑选的TAA在正常组织/细胞中低表达,这容易导致CAR-T细胞攻击表达靶抗原肿瘤细胞的同时会针对其他正常细胞,即产生脱靶毒性,进而可能导致肺纤维化、肝损伤和胃肠道功能紊乱等器官功能损伤[29]。为避免这些风险的发生,研究者正积极开发可用于应对靶抗原异质性和脱靶毒性的相关策略,包括筛选特异性肿瘤靶抗原和设计多靶点CAR-T细胞等。也有研究证实,单细胞RNA测序技术可能为TAA选择提供更多精确的靶抗原表达谱,且能更好预测肿瘤治疗中CAR-T细胞的效能和毒性[30]。此外,CAR-T细胞联合嵌合受体疫苗[31]、血管破坏剂[32]、PD1阻断剂[33]等也能下调脱靶毒性。

3.2 神经毒性神经系统不良反应是CAR-T细胞治疗后以多种神经症状为特征的严重不良反应,常见症状包括头痛、癫痫、失语、谵妄、脑出血,甚至死亡[34]。以往临床研究证实,全身性炎性反应或严重细胞因子释放综合征会增加神经系统不良反应的风险[35]。此外,内皮细胞的活化有助于免疫效应细胞和炎性反应介质突破血脑屏障进入中枢神经系统,从而发生神经中毒[36]。

3.3 细胞因子释放综合征细胞因子释放综合征(CRS)是CAR-T细胞治疗后产生的主要不良反应,是由活化的CAR-T细胞触发的全身性炎性反应。同时,伴随着以下常见症状:发热、寒颤、肌肉酸痛、厌食、乏力、多器官功能障碍等,严重时可危及生命[37]。因此,深入了解CRS的生物学特性、降低细胞因子释放、减少炎性反应的发生对于预防和治疗CRS至关重要。此外,识别CRS生物学标志物(IFN-γ、可溶性IL-1受体激动剂、糖蛋白亚基130)可在早期预判CRS的发生[38]。

3.4 肿瘤微环境免疫抑制肿瘤微环境(TME)是影响CAR-T细胞治疗实体瘤疗效的重要因素之一,主要为缺氧、氧化应激反应、细胞免疫检查点受体的免疫信号抑制和肿瘤来源的细胞因子抑制等[39]。研究证实,肿瘤细胞释放多种免疫抑制因子导致抑制性免疫细胞激活[40],从而限制了CAR-T细胞抗肿瘤效果。目前,有研究者通过基因编辑设计T细胞共表达免疫抑制性受体,进而增强CAR-T细胞治疗疗效。

4 结语和展望CAR-T细胞在血液恶性肿瘤中取得的成功,为胸部恶性肿瘤的免疫治疗带来了希望。随着对肿瘤发生机制不断了解,培养和利用患者自身资源治疗疾病比药物治疗更为重要。然而,由于胸部恶性肿瘤的异质性和前临床实验的局限性,CAR-T细胞在包括胸部恶性肿瘤在内的实体瘤的临床运用中存在一定的不良反应和潜在风险。为了克服这些风险和减少不良反应的发生,后续研究需要解决以下4个关键问题:(1)寻找更加稳定和特异性靶抗原和设计多靶点CAR-T细胞,减少脱靶毒性和免疫逃逸;(2)优化CAR-T细胞结构,靶向胸部恶性肿瘤微环境,增强疗效;(3)挖掘CAR-T细胞归巢调控因子和监控机制,保障CAR-T细胞治疗安全性;(4)探索联合治疗,如CAR-T细胞联合放疗、免疫检查点抑制剂等。重要的是,未来提高CAR-T细胞对肿瘤细胞的杀伤作用、延长患者生存时间是迫切需要解决的问题。综上所述,继续优化CAR-T细胞,设计理想的治疗方案,CAR-T细胞免疫疗法有望成为胸部恶性肿瘤治疗的有效策略。

利益冲突声明:

所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

作者贡献:

陈富坤:文献查阅、数据整理、文章撰写

陈娜娜:文献检索、图片绘制

邓智勇、吕娟:文献筛选

覃雯静:资料总结

朱家伦:立题构思及审核

| [1] |

Li Y, Sui Y, Chi M, et al. Study on the effect of MRI in the diagnosis of benign and malignant thoracic tumors[J]. Dis Markers, 2021, 2021: 3265561. |

| [2] |

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3): 209-249. DOI:10.3322/caac.21660 |

| [3] |

Hong M, Clubb JD, Chen YY. Engineering CAR-T cells for next-generation cancer therapy[J]. Cancer Cell, 2020, 38(4): 473-488. DOI:10.1016/j.ccell.2020.07.005 |

| [4] |

Anagnostou T, Riaz IB, Hashmi SK, et al. Anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in acute lymphocytic leukaemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Haematol, 2020, 7(11): e816-e826. DOI:10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30277-5 |

| [5] |

Ghosn M, Cheema W, Zhu A, et al. Image-guided interventional radiological delivery of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cells for pleural malignancies in a phaseⅠ/Ⅱ clinical trial[J]. Lung Cancer, 2022, 165: 1-9. DOI:10.1016/j.lungcan.2022.01.003 |

| [6] |

Yang S, Wei W, Zhao Q. B7-H3, a checkpoint molecule, as a target for cancer immunotherapy[J]. Int J Biol Sci, 2020, 16(11): 1767-1773. DOI:10.7150/ijbs.41105 |

| [7] |

Kontos F, Michelakos T, Kurokawa T, et al. B7-H3: An attractive target for antibody-based immunotherapy[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2021, 27(5): 1227-1235. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2584 |

| [8] |

Zhang Z, Jiang C, Liu Z, et al. B7-H3-targeted CAR-T cells exhibit potent antitumor effects on hematologic and solid tumors[J]. Mol Ther Oncolytics, 2020, 17: 180-189. DOI:10.1016/j.omto.2020.03.019 |

| [9] |

Xiang W, Lv Q, Shi H, et al. Aptamer-based biosensor for detecting carcinoembryonic antigen[J]. Talanta, 2020, 214: 120716. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2020.120716 |

| [10] |

Holdenrieder S, Wehnl B, Hettwer K, et al. Carcinoembryonic antigen and cytokeratin-19 fragments for assessment of therapy response in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Br J Cancer, 2017, 116(8): 1037-1045. DOI:10.1038/bjc.2017.45 |

| [11] |

Wang L, Ma N, Okamoto S, et al. Efficient tumor regression by adoptively transferred CEA-specific CAR-T cells associated with symptoms of mild cytokine release syndrome[J]. Oncoimmunology, 2016, 5(9): e1211218. DOI:10.1080/2162402X.2016.1211218 |

| [12] |

Santos EDS, Nogueira KAB, Fernandes LCC, et al. EGFR targeting for cancer therapy: Pharmacology and immunoconjugates with drugs and nanoparticles[J]. Int J Pharm, 2021, 592: 120082. DOI:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.120082 |

| [13] |

Xia L, Zheng ZZ, Liu JY, et al. EGFR-targeted CAR-T cells are potent and specific in suppressing triple-negative breast cancer both in vitro and in vivo[J]. Clin Transl Immunology, 2020, 9(5): e01135. |

| [14] |

Busek P, Mateu R, Zubal M, et al. Targeting fibroblast activation protein in cancer-Prospects and caveats[J]. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed), 2018, 23(10): 1933-1968. DOI:10.2741/4682 |

| [15] |

Schuberth PC, Hagedorn C, Jensen SM, et al. Treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma by fibroblast activation protein-specific re-directed T cells[J]. J Transl Med, 2013, 11: 187. DOI:10.1186/1479-5876-11-187 |

| [16] |

Salcedo EC, Winter MB, Khuri N, et al. Global protease activity profiling identifies HER2-driven proteolysis in breast cancer[J]. ACS Chem Biol, 2021, 16(4): 712-723. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.0c01000 |

| [17] |

Li H, Yuan W, Bin S, et al. Overcome trastuzumab resistance of breast cancer using anti-HER2 chimeric antigen receptor T cells and PD1 blockade[J]. Am J Cancer Res, 2020, 10(2): 688-703. |

| [18] |

Yu F, Wang X, Shi H, et al. Development of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for the treatment of esophageal cancer[J]. Tumori, 2021, 107(4): 341-352. DOI:10.1177/0300891620960223 |

| [19] |

Levý M, Boublíková L, Büchler T, et al. Treatment of malignant peritoneal mesothelioma[J]. Klin Onkol, 2019, 32(5): 333-337. |

| [20] |

Lv J, Li P. Mesothelin as a biomarker for targeted therapy[J]. Biomark Res, 2019, 7: 18. DOI:10.1186/s40364-019-0169-8 |

| [21] |

Zhang Q, Liu G, Liu J, et al. The antitumor capacity of mesothelin-CAR-T cells in targeting solid tumors in mice[J]. Mol Ther Oncolytics, 2021, 20: 556-568. DOI:10.1016/j.omto.2021.02.013 |

| [22] |

Jing X, Liang H, Hao C, et al. Overexpression of MUC1 predicts poor prognosis in patients with breast cancer[J]. Oncol Rep, 2019, 41(2): 801-810. |

| [23] |

Sun ZG, Yu L, Gao W, et al. Clinical and prognostic significance of MUC1 expression in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma after radical resection[J]. Saudi J Gastroenterol, 2018, 24(3): 165-170. DOI:10.4103/sjg.SJG_420_17 |

| [24] |

Pourjafar M, Samadi P, Saidijam M. MUC1 antibody-based therapeutics: the promise of cancer immunotherapy[J]. Immunotherapy, 2020, 12(17): 1269-1286. DOI:10.2217/imt-2020-0019 |

| [25] |

Kitagawa S, Hakozaki T, Kitadai R, et al. Switching administration of anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies as immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge in individuals with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: Case series and literature review[J]. Thorac Cancer, 2020, 11(7): 1927-1933. DOI:10.1111/1759-7714.13483 |

| [26] |

Qin L, Zhao R, Chen D, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells targeting PD-L1 suppress tumor growth[J]. Biomark Res, 2020, 8: 19. DOI:10.1186/s40364-020-00198-0 |

| [27] |

Balakrishnan A, Goodpaster T, Randolph-Habecker J, et al. Analysis of ROR1 protein expression in human cancer and normal tissues[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2017, 23(12): 3061-3071. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2083 |

| [28] |

Hudecek M, Lupo-Stanghellini MT, Kosasih PL, et al. Receptor affinity and extracellular domain modifications affect tumor recognition by ROR1-specific chimeric antigen receptor T cells[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2013, 19(12): 3153-3164. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0330 |

| [29] |

Bonifant CL, Jackson HJ, Brentjens RJ, et al. Toxicity and management in CAR T-cell therapy[J]. Mol Ther Oncolytics, 2016, 3: 16011. DOI:10.1038/mto.2016.11 |

| [30] |

Watanabe K, Kuramitsu S, Posey AD Jr, et al. Expanding the therapeutic window for CAR T cell therapy in solid tumors: the knowns and unknowns of CAR T cell biology[J]. Front Immunol, 2018, 9: 2486. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02486 |

| [31] |

Ma L, Dichwalkar T, Chang JYH, et al. Enhanced CAR-T cell activity against solid tumors by vaccine boosting through the chimeric receptor[J]. Science, 2019, 365(6449): 162-168. DOI:10.1126/science.aav8692 |

| [32] |

Deng C, Zhao J, Zhou S, et al. The vascular disrupting agent CA4P improves the antitumor efficacy of CAR-T cells in preclinical models of solid human tumors[J]. Mol Ther, 2020, 28(1): 75-88. DOI:10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.10.010 |

| [33] |

Gargett T, Yu W, Dotti G, et al. GD2-specific CAR T cells undergo potent activation and deletion following antigen encounter but can be protected from activation-induced cell death by PD-1 blockade[J]. Mol Ther, 2016, 24(6): 1135-1149. DOI:10.1038/mt.2016.63 |

| [34] |

Rubin DB, Danish HH, Ali AB, et al. Neurological toxicities associated with chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy[J]. Brain, 2019, 142(5): 1334-1348. DOI:10.1093/brain/awz053 |

| [35] |

Freyer CW, Porter DL. Cytokine release syndrome and neurotoxicity following CAR T-cell therapy for hematologic malignancies[J]. J Allergy Clin Immunol, 2020, 146(5): 940-948. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2020.07.025 |

| [36] |

Gust J, Hay KA, Hanafi LA, et al. Endothelial activation and blood-brain barrier disruption in neurotoxicity after adoptive immunotherapy with CD19 CAR-T cells[J]. Cancer Discov, 2017, 7(12): 1404-1419. DOI:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0698 |

| [37] |

Neelapu SS, Tummala S, Kebriaei P, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy-assessment and management of toxicities[J]. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2018, 15(1): 47-62. DOI:10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.148 |

| [38] |

Teachey DT, Lacey SF, Shaw PA, et al. Identification of predictive biomarkers for cytokine release syndrome after chimeric antigen receptor t-cell therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia[J]. Cancer Discov, 2016, 6(6): 664-679. DOI:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-16-0040 |

| [39] |

Martinez M, Moon EK. CAR T cells for solid tumors: new strategies for finding, infiltrating, and surviving in the tumor microenvironment[J]. Front Immunol, 2019, 10: 128. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00128 |

| [40] |

Qi FL, Wang MF, Li BZ, et al. Reversal of the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment by nanoparticle-based activation of immune-associated cells[J]. Acta Pharmacol Sin, 2020, 41(7): 895-901. DOI:10.1038/s41401-020-0423-5 |

2023, Vol. 50

2023, Vol. 50