文章信息

- 靶向uPA-uPAR系统在肿瘤治疗中的研究进展

- Research Progress of Targeting uPA-uPAR System in Tumor Therapy

- 肿瘤防治研究, 2023, 50(2): 202-208

- Cancer Research on Prevention and Treatment, 2023, 50(2): 202-208

- http://www.zlfzyj.com/CN/10.3971/j.issn.1000-8578.2023.22.0737

- 收稿日期: 2022-07-04

- 修回日期: 2022-09-19

2. 730000 兰州,兰州大学第二医院萃英生物医学研究中心

2. Cuiying Biomedical Research Center, Lanzhou University Second Hospital, Lanzhou 730000, China

早在1878年Billroth在纤维蛋白性血栓中发现了肿瘤细胞,推测纤维蛋白可促进肿瘤的侵袭和转移,并且同一时期的许多研究结果也支持这一观点,证明纤维蛋白原、纤维蛋白和纤维蛋白溶解系统可能与肿瘤的生长及转移存在关联[1]。目前研究表明,由尿激酶型纤溶酶原激活物(urokinase-type plasminogen activator, uPA)、尿激酶型纤溶酶原激活剂物体(urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor, uPAR)和尿激酶型纤溶酶原激活抑制物(plasminogen activator inhibitor, PAI)组成的uPA-uPAR系统在肿瘤的发生发展中起着重要的作用[2]。uPAR是一种糖基磷脂酰肌醇(glycosylphosphatidylinositol, GPI)锚定的膜蛋白,其既可以通过与uPA结合促进细胞外基质蛋白降解,还可以与整合素及玻连蛋白(Vitronection)结合介导RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK、PI3K/AKT等细胞信号通路激活,上述作用不仅可以增强肿瘤细胞的增殖、迁移和侵袭能力,还能抑制肿瘤细胞凋亡,并促进肿瘤组织血管生成[3]。尽管PAI(PAI-1、PAI-2)对uPA-uPAR系统有抑制作用[4],但在肿瘤中却不尽相同。

大量的研究发现uPA-uPAR系统在人类的前列腺癌、乳腺癌、结直肠癌等多种肿瘤组织中表达增高,是肿瘤诊断和治疗的潜在靶点[5]。据此研发了一批靶向uPA-uPAR系统的检测方案:主要有测定血液和组织中uPA、PAI和可溶性尿激酶型纤溶酶原激活剂受体(soluble urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor, suPAR)的酶联免疫吸附测定和实时荧光聚合酶链反应实验的试剂盒,以及靶向uPA的抗体(如ATN-291)和靶向uPAR的多肽(如AE105)、抗体(如ATN-658, 2G10)等肿瘤成像剂,进而对肿瘤进行早期诊断和预后评估,并且这些方案已经呈现出较理想的效果[3, 6]。同样地,靶向uPA-uPAR系统在肿瘤的治疗中也具有不容忽视的价值。

过去的三十多年里大量学者对靶向uPA-uPAR系统在肿瘤治疗领域作出了巨大贡献,这些成就主要包括开发了靶向uPA-uPAR系统的基因治疗、药物治疗和免疫治疗等方案,同时对其中一些方案进行了临床试验并取得了较为理想的治疗效果。

1 靶向uPA-uPAR系统在肿瘤基因治疗中的应用基因治疗是一种将外源性遗传物质转移到患者体内的治疗方式,最早被用于治疗遗传性疾病。近年来随着研究的深入,基因治疗已从治疗单基因病种向传染病、神经退行性疾病和肿瘤等疾病发展[7-8]。在靶向uPA-uPAR系统的基因治疗中,反义寡核酸(antisense oligonucleotide, aODN)技术、RNA干扰(RNA interference, RNAi)技术和核酸适配体技术是较为成熟的方案。由于uPA-uPAR系统具有促进肿瘤侵袭和转移的作用,Anna等构建的uPAR-aODN通过抑制TGF-β而遏制黑色素瘤的上皮-间充质转化过程,从而减缓肿瘤进展;同时Wu等构建的靶向环氧化酶-2的aODN通过间接抑制uPA和uPAR的转录而抑制人骨肉瘤细胞的侵袭[9-10]。以上靶向uPA-uPAR系统的实验均证实利用反义寡核酸技术的靶向治疗在肿瘤的基因治疗中具有可行性。在RNAi技术领域,GONDI等通过RNAi技术对人脑胶质瘤细胞的uPA和uPAR基因进行靶向抑制后发现RNAi通过下调PI3K/AKT/mTOR通路而促进半胱氨酸天冬氨酸蛋白酶-9表达,最终共同促进脑胶质瘤细胞的凋亡,Anna等还利用RNAi技术靶向抑制uPAR在黑色素瘤中表达,进而增强维莫非尼治疗黑色素瘤的敏感度[11-12]。最后,由于核酸适配体为单链核酸,并且具有稳定的三维结构,同时对靶点有较高特异性和亲和力、以及相对较小的分子结构和可控的化学合成方法,因此在肿瘤的诊断和治疗中具有显著的优势[13]; 尽管PAI对uPA-uPAR具有抑制作用,但在肿瘤中PAI-1还可以通过与Vitronection结合促进肿瘤进展,故其在肿瘤的基因治疗中也是一个较为理想的靶点,Fortenberry等根据这一特性开发的靶向PAI-1的RNA适配体WT-15和SM-20在乳腺癌中能够与PAI-1特异结合而竞争性抑制其与Vitronection结合,进而抑制肿瘤的侵袭与转移[14-15]。尽管靶向uPA-uPAR系统的基因治疗在肿瘤防治中已有较多的研究,但由于长时间以来人们对“核酸类”基因治疗认识的不足,使得到目前为止没有一个此类研究进入临床试验阶段。然而,随着最近基于CRISPR-Cas9技术的uPAR基因敲除在黑色素瘤治疗中潜在价值的发现以及针对SARS-CoV-2的mRNA疫苗在全球的使用[16],此类治疗方案在未来可能会获得较好的认可和发展。

2 靶向uPA-uPAR系统在肿瘤药物治疗中的应用在靶向uPA-uPAR系统的抗肿瘤药物中,靶向uPA的药物最早被研发。随着研究的深入,研究者不仅丰富了靶向uPA药物的种类,还制备了大量靶向uPAR和PAI-1的抗肿瘤药物,这些药物主要包括抑制剂、天然产物和表观遗传药物。

2.1 抑制剂Upamostat是一种靶向uPA的丝氨酸蛋白酶抑制剂,其包括静脉注射药物WX-UK1和口服药物WX-671。其中最早研发的WX-UK1可以显著抑制小鼠乳腺癌的生长和淋巴结转移,而基于WX-UK1开发的口服前体药物WX-671不仅在体外可将人乳腺癌细胞抑制在细胞周期的G1/S期,从而抑制其增殖能力;而且在体内实验研究中,WX-671联合吉西他滨可提高乳腺癌患者中位生存率,并具有较小的不良反应。同时已完成的药代动力学研究和Ⅱ期临床试验证实其具有良好的安全性和耐受性[17-20]。如前所述uPA同uPAR结合可促进肿瘤的发生与发展,因此基于目前较完善的小分子化合物(抑制剂)筛选和改造技术,近期研究者研发了一批靶向抑制uPA与uPAR结合的药物,其中有明显潜在价值的抗肿瘤药物有IPR-3011和IPR-3242等[21-22]。尽管已经开发的靶向PAI-1的药物已超过50种[23],但明确具有抗肿瘤效果的只有IMD-4482、TM5275和TM5441,分别具有抑制人卵巢癌和纤维肉瘤在体内的生长作用[24-26]。

与传统的化疗药物相比,肽类药物在肿瘤的治疗中具有高靶向性、低毒性、低免疫原性及低制备成本等显著优点,因此肽类药物在肿瘤的靶向治疗中具有独特的优势[27]。由于uPAR缺乏跨膜区和细胞内结构域,其介导的细胞信号转导依靠整合素与Vitronection完成[2],而这一过程需要进行蛋白质间相互作用(protein-protein interaction, PPI),同时uPA与uPAR的结合也要进行PPI,这为肽类药物通过靶向uPA-uPAR系统治疗肿瘤奠定了基础。A6肽(乙酰基-KPSSPPEE-氨基)是一个由8个氨基酸构成的可靶向抑制uPA与uPAR及SuPAR结合的多肽;单独使用时即可明显抑制鼠乳腺癌的转移,对于雌激素受体阳性的乳腺癌,其联用他莫昔芬后表现出更显著的抗肿瘤转移作用。此外有临床Ⅱ期试验证实其在卵巢癌治疗中具有良好的安全性和疗效[28]。最近研发的靶向uPA的多肽Pep1和Pep2通过阻碍uPA与整合素αV结合而终止uPAR与整合素间的联系达到抗肿瘤的作用[29]。此外,由于uPAR可以通过结合G蛋白偶联的甲酰化肽受体(formylpeptide receptors, FPRs)促进肿瘤细胞迁移[30],Minopoli和Carriero等依据这一特点开发了一系列靶向uPAR与FPR1结合的多肽抑制剂(如SRSRY、UPARANT等),其中多肽RI-3是此类药物经多次优化后的代表药物,具有令人鼓舞的抗肿瘤作用及安全性。最新研究提示RI-3可以显著抑制黑色素瘤和转移性肉瘤的迁移和侵袭能力,并且在骨肉瘤中还可以通过减少单核细胞招募达到遏制肿瘤转移的作用[31-34],因此多肽RI-3为抗肿瘤药物的研发提供了一个新思路。

2.2 天然产物和表观遗传药物β-榄香烯是一种从姜科植物温郁金(莪术)中提取的倍半萜类化合物,也是最早被我国中医用来治疗肿瘤的药物之一,现代医学研究证实其主要通过抑制细胞增殖、阻滞细胞周期和诱导凋亡等途径发挥抗癌作用[35]。在uPA-uPAR系统中其通过抑制uPA、uPAR、MMP-2和MMP-9等的表达减缓小鼠黑色素瘤的生长[36]。氧化苦参碱(Oxymatrine, OMT)是另一种从豆科槐属植物中提取的生物碱,具有调节免疫、抗炎和抗病毒的作用,因此最早被用于治疗慢性病毒性肝炎,但随后大量研究发现其还可以通过PI3K/AKT、EGFR/AKT和NF-κB等通路参与调节肿瘤细胞的增殖和凋亡等[37],而Wang等研究发现OMT可通过抑制TGF-β1/Smad通路减少结直肠癌中PAI-1的表达,进而抑制结肠癌的侵袭[38]。槲皮素(Quercetin, Qu)是一种广泛存在于植物中的黄酮醇类化合物,过去许多研究证明其可通过调节PI3K/AKT/mTOR、Wnt/β-Catenin和MAPK/ERK1/2等通路,促进肿瘤细胞凋亡和自噬[39],同样地在胃癌的治疗中,Qu通过抑制NF-κB等通路和降低uPA及uPAR的表达抑制胃癌细胞的转移能力[40]。来源于中草药的天然产物在过去的几十年里不仅得到了世界的认可,也丰富了新药开发的来源,随着天然产物安全性和有效性研究的不断发展,这类药物会在不久的将来为肿瘤临床治疗提供更多的选择。由于在肿瘤的进展及转移过程中往往伴随着DNA甲基化、组蛋白修饰和染色质结构异常等表观遗传失调活动,因此研发表观遗传药物是肿瘤治疗的潜在疗法[41]。在乳腺癌中uPA基因启动子的低甲基化可促进uPA表达,基于此开发的表观遗传药物S-腺苷蛋氨酸(S-adenosylmethionine, SAM)通过阻止uPA基因启动子去甲基化而抑制乳腺癌细胞的侵袭,并呈剂量依赖性抑制人骨肉瘤细胞的增殖和侵袭[42-43],由于稳定的SAM制剂多可口服,为肿瘤预防和治疗提供了方便,同时将表观遗传疗法与目前正在开发的各种治疗策略相结合可发挥强大的协同效应。

3 靶向uPA-uPAR系统在肿瘤免疫治疗中的应用通过增强体内免疫反应来消除肿瘤的免疫疗法为肿瘤治疗提供了新策略,并随着杂交瘤技术的发展,许多团队开发了靶向肿瘤抗原的单克隆抗体并在肿瘤免疫治疗中取得了显著的疗效,近年来Carl H.June等构建的嵌合抗原受体T细胞(chimeric antigen receptor T-cell, CAR-T)免疫疗法在肿瘤免疫治疗中也取得了不菲的成就[44]。

由于uPAR既是膜蛋白又在多种肿瘤组织中显著高表达,这使其成为肿瘤免疫治疗的新靶点。在过去十几年的研究中大量靶向uPAR的单克隆抗体被研制,其中ATN-658和2G10是目前研究较深入的单克隆抗体。首先,ATN-658在体内外对人前列腺癌细胞的生长、侵袭及转移均有抑制作用,而这种作用可能通过抑制uPAR与整合素CD11b结合来实现[45-46]。随后经人源化改造后的huATN-658无论是单用还是联合使用唑来膦酸在人乳腺癌及乳腺癌相关骨病模型中均表现出可观的抗肿瘤作用[47]。2G10是另一种靶向uPAR的单克隆抗体,虽然目前主要被应用在肿瘤成像剂领域,但其在体内外实验中均表现出具有抑制人乳腺癌细胞增殖和迁移的能力,并且基于2G10开发的抗体药物偶联物(antibody-drug conjugates, ADCs)在高侵袭性三阴性乳腺癌的小鼠异种种植模型的治疗中取得了较好的疗效[48-49]。近年来随着抗体制备技术的完善和发展,特别是PD-1及其配体PD-L1单克隆抗体的研发与应用,将为肿瘤的免疫治疗带来更大的空间。最近Qin等针对uPAR在弥漫型胃癌(diffuse-type gastric cancer, DGC)中高表达的现象,制备了靶向uPAR的单克隆抗体Anti-uPAR,其在联用PD-1抗体后可明显促进免疫细胞在人DGC组织(人源肿瘤细胞系异种移植鼠模型和人源肿瘤组织来源移植瘤鼠模型)中的浸润,同时该抗体还通过结合uPAR的DⅡ-DⅢ结构域而抑制下游激酶ERK的磷酸化,最终促进了DGC的免疫治疗[50]。

Wang等于2019年首次报道了靶向uPAR的CAR-T细胞疗法,其在体外对卵巢癌细胞具有明显的杀伤作用[51],随后Amor等的研究发现靶向uPAR的CAR-T细胞不仅可以高效地清除体内衰老的细胞和改善肝纤维化,甚至还延长了负荷肺腺癌鼠的生存时间[52]。此外,在DGC的治疗中,Qin等研究发现靶向uPAR的CAR-T细胞疗法在体内和体外对DGC均有较好的杀伤效果[50]。上述研究均为CAR-T细胞疗法在实体瘤中的应用开辟了新思路。CAR-T细胞疗法在血液学相关恶性肿瘤的治疗方面已经显示出巨大的前景,尽管在实体瘤的治疗中仍存在着一定的困难,但随着肿瘤特异性靶标的发现和CAR-T细胞结构的优化,CAR-T细胞疗法在肿瘤的免疫治疗中将会取得较好的发展。

4 其他新型靶向治疗药物在肿瘤治疗中的应用多肽偶联药物(peptide-drug conjugates, PDCs)是一种将细胞毒性药物或放化疗药物通过与靶向多肽共价连接的新型抗肿瘤药物,因其可以靶向传递,所以与普通抗肿瘤药物相比具有更好的靶向性和安全性[53]。AE105是能与uPAR高度亲和的人工合成肽,以往主要作为靶向探针被用在肿瘤的诊断中,但在最近的研究中Persson等人将放射性核素镥(177Lu)与AE105偶联制备的177Lu-DOTA-AE105显著遏制了人前列腺癌在小鼠模型中的转移[54]。在肿瘤光热治疗领域,Yu等将金属铱(Iridium, Ir)与AE105结合形成的新型光热剂GNS@Ir@P-AE105在体内外均可促进肿瘤细胞内产生活性氧而导致其DNA严重损伤,进而促进肿瘤细胞凋亡,最终在三阴性乳腺癌的治疗中取得疗效[55],同时Simón等将荧光探针吲哚菁绿(indocyanine green, ICG)与AE-105结合制备的ICG-Glu-Glu-AE105在人脑胶质瘤小鼠模型中不仅可以通过释放热能杀伤肿瘤,还可以在术中进行肿瘤定位[56]。此外,由A6肽与长春新碱组装的PDCs(A6-cPS-VCR)可显著减少急性髓系白血病(acute myelocytic leukemia, AML)模型鼠体内的肿瘤细胞并延长模型鼠生存时间[57]。在肿瘤的免疫毒素治疗中,Provenzano等利用基因工程技术将uPA的部分氨基末端(amino-terminal fragment, ATF)片段与皂草素(Saporin, SAP)融合后制备了嵌合蛋白ATF-SAP,该蛋白通过靶向结合uPAR后再用毒素SAP对肿瘤进行杀伤,并且已在人血液肿瘤疾病、膀胱癌、乳腺癌细胞中得到初步验证[58-59]。最后,基于同样的原理研发的eBAT通过双特异靶向uPAR和表皮生长因子受体(EGFR)来调节实体瘤中血管生成,最终达到抗肿瘤作用[60]。此外,基于材料学和分子生物学的发展,此类新兴的药物制剂将会使更多的肿瘤患者受益。

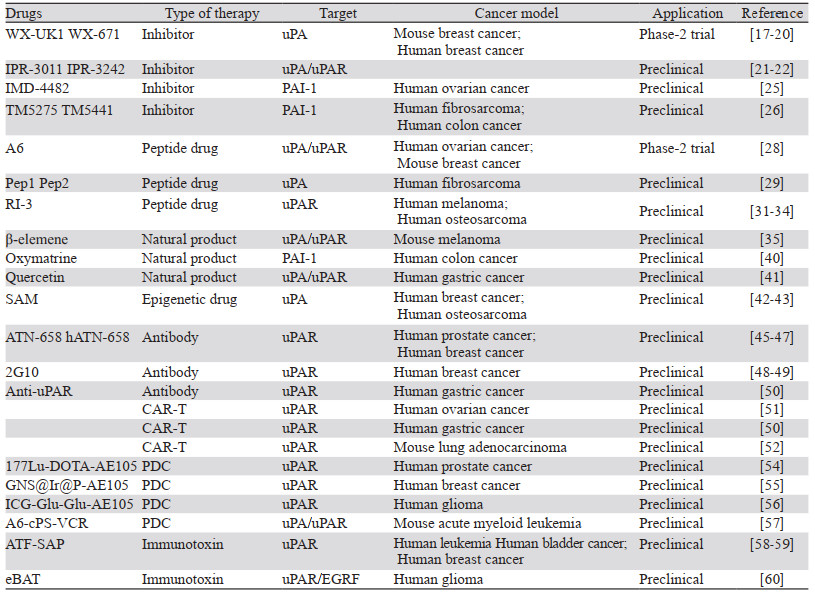

一些重要的靶向uPA药物总结见表 1。

在过去三十多年的研究中,越来越多的研究证实uPA-uPAR系统在肿瘤的发生和发展中发挥着重要作用,主要表现为该系统在多数肿瘤组织中高表达并且激活后可明显促进肿瘤细胞的增殖、侵袭和转移等,就此研究者从基因和蛋白水平入手,对该系统进行了大量的基因、药物和免疫治疗等实验,并提出和验证了一批具有良好效果的治疗方案,尤其在药物治疗领域的抑制剂WX-671及A6肽已经完成相应的Ⅱ期临床研究。此外基于抗体和多肽的ADCs及PDCs在该系统的肿瘤靶向治疗中有较好的前景。最后,尽管目前靶向uPA-uPAR系统在肿瘤的基因治疗和免疫治疗领域有较大的挑战,但CRISPR-Cas9技术和mRNA疫苗技术的成熟可很好地弥补基因治疗的局限,而在免疫治疗方面,成熟的抗体制备技术和迅速发展的CAR-T技术也将克服这一困难,最终共同促进肿瘤的靶向治疗。

作者贡献:

蔡伟文:文献检索、资料整理及论文撰写

秦龙、张俊昶、文飞、张文涛:文献检索、资料整理及论文校对

焦作义:文章指导及论文修改

| [1] |

Kwaan HC, Lindholm PF. Fibrin and Fibrinolysis in Cancer[J]. Semin Thromb Hemost, 2019, 45(4): 413-422. DOI:10.1055/s-0039-1688495 |

| [2] |

Smith HW, Marshall CJ. Regulation of cell signalling by uPAR[J]. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 2010, 11(1): 23-36. DOI:10.1038/nrm2821 |

| [3] |

Mahmood N, Rabbani SA. Fibrinolytic System and Cancer: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Applications[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2021, 22(9): 4358-4374. DOI:10.3390/ijms22094358 |

| [4] |

Lv T, Zhao Y, Jiang X, et al. uPAR: An Essential Factor for Tumor Development[J]. J Cancer, 2021, 12(23): 7026-7040. DOI:10.7150/jca.62281 |

| [5] |

Masucci MT, Minopoli M, Gioconda DC. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Urokinase and Its Receptor in Cancer[J]. Cancers (Basel), 2022, 14(3): 498-521. DOI:10.3390/cancers14030498 |

| [6] |

Su SC, Lin CW, Yang WE, et al. The urokinase-type plasminogen activator (uPA) system as a biomarker and therapeutic target in human malignancies[J]. Expert Opin Ther Targets, 2016, 20(5): 551-566. DOI:10.1517/14728222.2016.1113260 |

| [7] |

Anguela XM, High KA. Entering the Modern Era of Gene Therapy[J]. Annu Rev Med, 2019, 70: 273-288. DOI:10.1146/annurev-med-012017-043332 |

| [8] |

Husain SR, Han J, Au P, et al. Gene therapy for cancer: regulatory considerations for approval[J]. Cancer Gene Ther, 2015, 22(12): 554-563. DOI:10.1038/cgt.2015.58 |

| [9] |

Anna L, Alessio B, Francesca B, et al. Inhibition of uPAR-TGFβ crosstalk blocks MSC-dependent EMT in melanoma cells[J]. J Mol Med (Berl), 2015, 93(7): 783-794. DOI:10.1007/s00109-015-1266-2 |

| [10] |

Margheri F, D'alessio S, Serratí S, et al. Effects of blocking urokinase receptor signaling by antisense oligonucleotides in a mouse model of experimental prostate cancer bone metastases[J]. Gene Ther, 2005, 12(8): 702-714. DOI:10.1038/sj.gt.3302456 |

| [11] |

Wu X, Cai M, Ji F, et al. The impact of COX-2 on invasion of osteosarcoma cell and its mechanism of regulation[J]. Cancer Cell Int, 2014, 14: 27-33. DOI:10.1186/1475-2867-14-27 |

| [12] |

GondI CS, Kandhukuri N, Dinh DH, et al. Down-regulation of uPAR and uPA activates caspase-mediated apoptosis and inhibits the PI3K/AKT pathway[J]. Int J Oncol, 2007, 31(1): 19-27. |

| [13] |

Zhou J, Bobbin ML, Burnett JC, et al. Current progress of RNA aptamer-based therapeutics[J]. Front Genet, 2012, 3: 234-248. |

| [14] |

Blake CM, Sullenger BA, Lawrence DA, et al. Antimetastatic potential of PAI-1-specific RNA aptamers[J]. Oligonucleotides, 2009, 19(2): 117-128. DOI:10.1089/oli.2008.0177 |

| [15] |

Fortenberry YM, Brandal SM, Carpentier G, et al. Intracellular Expression of PAI-1 Specific Aptamers Alters Breast Cancer Cell Migration, Invasion and Angiogenesis[J]. PLoS one, 2016, 11(10): e0164288. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0164288 |

| [16] |

Biagioni A, Laurenzana A, Menicacci B, et al. uPAR-expressing melanoma exosomes promote angiogenesis by VE-Cadherin, EGFR and uPAR overexpression and rise of ERK1, 2 signaling in endothelial cells[J]. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2021, 78(6): 3057-3072. DOI:10.1007/s00018-020-03707-4 |

| [17] |

Lee JE, Kwon YJ, Baek HS, et al. Synergistic induction of apoptosis by combination treatment with mesupron and auranofin in human breast cancer cells[J]. Arch Pharm Res, 2017, 40(6): 746-759. DOI:10.1007/s12272-017-0923-0 |

| [18] |

Faizal ZA, Mohamed AH, Yo HK, et al. Effects of upamostat and opaganib on cholangiocarcinoma patient derived xenografts[J]. Cancer Res, 2020, 80(16): Abstract 3078. |

| [19] |

Park C, Ha JG, Choi S, et al. HPLC-MS/MS analysis of mesupron and its application to a pharmacokinetic study in rats[J]. J Pharm Biomed Anal, 2018, 150: 39-42. DOI:10.1016/j.jpba.2017.12.002 |

| [20] |

Heinemann V, Ebert MP, Laubender RP, et al. Phase Ⅱ randomised proof-of-concept study of the urokinase inhibitor upamostat (WX-671) in combination with gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with non-resectable, locally advanced pancreatic cancer[J]. Br J Cancer, 2013, 108(4): 766-770. DOI:10.1038/bjc.2013.62 |

| [21] |

Xu D, Bum-erdene K, Leth JM, et al. Small-Molecule Inhibition of the uPAR-uPA Interaction by Conformational Selection[J]. Chem Med Chem, 2021, 16(2): 377-387. DOI:10.1002/cmdc.202000558 |

| [22] |

Bum-erdene K, Liu D, Xu D, et al. Design and Synthesis of Fragment Derivatives with a Unique Inhibition Mechanism of the uPAR-uPA Interaction[J]. ACS Med Chem Lett, 2021, 12(1): 60-66. DOI:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00422 |

| [23] |

Rouch A, Vanucci-Bacqué C, Bedos-Belval F, et al. Small molecules inhibitors of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 an overview[J]. Eur J Med Chem, 2015, 92: 619-636. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.01.010 |

| [24] |

Mashiko S, Kitatani k, Toyoshima M, et al. Inhibition of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is a potential therapeutic strategy in ovarian cancer[J]. Cancer Biol Ther, 2015, 16(2): 253-260. DOI:10.1080/15384047.2014.1001271 |

| [25] |

Nakatsuka E, Sawada K, Nakamura K, et al. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 is an independent prognostic factor of ovarian cancer and IMD-4482, a novel plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 inhibitor, inhibits ovarian cancer peritoneal dissemination[J]. Oncotarget, 2017, 8(52): 89887-89902. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.20834 |

| [26] |

Placencio VR, Ichimura A, Miyata T, et al. Small Molecule Inhibitors of Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 Elicit Anti-Tumorigenic and Anti-Angiogenic Activity[J]. PLoS one, 2015, 10(7): e0133786. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0133786 |

| [27] |

Yavari B, Mahjub R, Saidijam M, et al. The Potential Use of Peptides in Cancer Treatment[J]. Curr Protein Pept Sci, 2018, 19(8): 759-770. DOI:10.2174/1389203719666180111150008 |

| [28] |

Gold MA, Brady WE, Lankes HA, et al. A phaseⅡ study of a urokinase-derived peptide (A6) in the treatment of persistent or recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study[J]. Gynecol Oncol, 2012, 125(3): 635-639. DOI:10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.03.023 |

| [29] |

Belli S, Franco P, Iommelli F, et al. Breast Tumor Cell Invasion and Pro-Invasive Activity of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts Co-Targeted by Novel Urokinase-Derived Decapeptides[J]. Cancers (Basel), 2020, 12(9): 2404-2429. DOI:10.3390/cancers12092404 |

| [30] |

Tian C, Chen K, Gong W, et al. The G-Protein Coupled Formyl Peptide Receptors and Their Role in the Progression of Digestive Tract Cancer[J]. Technol Cancer Res Treat, 2020, 19: 1-10. |

| [31] |

Minopoli M, Botti G, Gigantino V, et al. Targeting the Formyl Peptide Receptor type 1 to prevent the adhesion of ovarian cancer cells onto mesothelium and subsequent invasion[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2019, 38(1): 459-475. DOI:10.1186/s13046-019-1465-8 |

| [32] |

Ragone C, Minopoli M, Ingangi V, et al. Targeting the cross-talk between Urokinase receptor and Formyl peptide receptor type 1 to prevent invasion and trans-endothelial migration of melanoma cells[J]. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2017, 36(1): 180-196. DOI:10.1186/s13046-017-0650-x |

| [33] |

Carriero MV, Bifulco K, Ingangi V, et al. Retro-inverso Urokinase Receptor Antagonists for the Treatment of Metastatic Sarcomas[J]. Sci Rep, 2017, 7(1): 1312-1329. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-01425-9 |

| [34] |

Minopoli M, Sarno S, Di CG, et al. Inhibiting Monocyte Recruitment to Prevent the Pro-Tumoral Activity of Tumor-Associated Macrophages in Chondrosarcoma[J]. Cells, 2020, 9(4): 1062-1084. DOI:10.3390/cells9041062 |

| [35] |

Zhai B, Zhang N, Han X, et al. Molecular targets of β-elemene, a herbal extract used in traditional Chinese medicine, and its potential role in cancer therapy: A review[J]. Biomed Pharmacother, 2019, 114: 108812-108823. DOI:10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108812 |

| [36] |

Shi H, Liu L, Liu LM, et al. Inhibition of tumor growth by β-elemene through downregulation of the expression of uPA, uPAR, MMP-2, and MMP-9 in a murine intraocular melanoma model[J]. Melanoma Res, 2015, 25(1): 15-21. DOI:10.1097/CMR.0000000000000124 |

| [37] |

Halim CE, Xinjing SL, Fan L, et al. Anti-cancer effects of oxymatrine are mediated through multiple molecular mechanism(s) in tumor models[J]. Pharmacol Res, 2019, 147: 104327-104339. DOI:10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104327 |

| [38] |

Wang X, Liu C, Wang J, et al. Oxymatrine inhibits the migration of human colorectal carcinoma RKO cells via inhibition of PAI-1 and the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway[J]. Oncol Rep, 2017, 37(2): 747-753. DOI:10.3892/or.2016.5292 |

| [39] |

Reyes FM, Carrasco PC. The Anti-Cancer Effect of Quercetin: Molecular Implications in Cancer Metabolism[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2019, 20(13): 3177-3196. DOI:10.3390/ijms20133177 |

| [40] |

Li H, Chen C. Quercetin Has Antimetastatic Effects on Gastric Cancer Cells via the Interruption of uPA/uPAR Function by Modulating NF-κb, PKC-δ, ERK1/2, and AMPKα[J]. Integr Cancer Ther, 2018, 17(2): 511-523. DOI:10.1177/1534735417696702 |

| [41] |

Lin SQ, Li X. Epigenetic Therapies and Potential Drugs for Treating Human Cancer[J]. Curr Drug Targets, 2020, 21(11): 1068-1083. DOI:10.2174/1389450121666200325093104 |

| [42] |

Chik F, Machnes Z, Szyf M. Synergistic anti-breast cancer effect of a combined treatment with the methyl donor S-adenosyl methionine and the DNA methylation inhibitor 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine[J]. Carcinogenesis, 2014, 35(1): 138-144. DOI:10.1093/carcin/bgt284 |

| [43] |

Parashar S, Cheishvili D, Arakelian A, et al. S-adenosylmethionine blocks osteosarcoma cells proliferation and invasion in vitro and tumor metastasis in vivo: therapeutic and diagnostic clinical applications[J]. Cancer Med, 2015, 4(5): 732-744. DOI:10.1002/cam4.386 |

| [44] |

Van DBJ, VerdegaaL EM, De MNF. Cancer immunotherapy: broadening the scope of targetable tumours[J]. Open Biol, 2018, 8(6): 180037-180047. DOI:10.1098/rsob.180037 |

| [45] |

Rabbani SA, Ateeq B, Arakelian A, et al. An anti-urokinase plasminogen activator receptor antibody (ATN-658) blocks prostate cancer invasion, migration, growth, and experimental skeletal metastasis in vitro and in vivo[J]. Neoplasia, 2010, 12(10): 778-788. DOI:10.1593/neo.10296 |

| [46] |

Xu X, Cai Y, Wei Y, et al. Identification of a new epitope in uPAR as a target for the cancer therapeutic monoclonal antibody ATN-658, a structural homolog of the uPAR binding integrin CD11b (αM)[J]. PLoS one, 2014, 9(1): e85349. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0085349 |

| [47] |

Mahmood N, Arakelian A, Khan HA, et al. uPAR antibody (huATN-658) and Zometa reduce breast cancer growth and skeletal lesions[J]. Bone Res, 2020, 8: 18-30. DOI:10.1038/s41413-020-0094-3 |

| [48] |

Lebeau AM, DurisetI S, Murphy ST, et al. Targeting uPAR with antagonistic recombinant human antibodies in aggressive breast cancer[J]. Cancer Res, 2013, 73(7): 2070-2081. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3526 |

| [49] |

Harel ET, Drake PM, Barfield RM, et al. Antibody-Drug Conjugates Targeting the Urokinase Receptor (uPAR) as a Possible Treatment of Aggressive Breast Cancer[J]. Antibodies(Basel), 2019, 8(4): 54. |

| [50] |

Qin L, Wang L, Zhang J, et al. Therapeutic strategies targeting uPAR potentiate anti-PD-1 efficacy in diffuse-type gastric cancer[J]. Sci Adv, 2022, 8(21): eabn3774. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.abn3774 |

| [51] |

Wang l, Yang R, Zhao L, et al. Basing on uPAR-binding fragment to design chimeric antigen receptors triggers antitumor efficacy against uPAR expressing ovarian cancer cells[J]. Biomed Pharmacother, 2019, 117: 109173-109181. DOI:10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109173 |

| [52] |

Amor C, Feucht J, Leibold J, et al. Senolytic CAR T cells reverse senescence-associated pathologies[J]. Nature, 2020, 583(7814): 127-132. DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-2403-9 |

| [53] |

Alas M, Saghaeidehkordi A, Kaur K. Peptide-Drug Conjugates with Different Linkers for Cancer Therapy[J]. J Med Chem, 2021, 64(1): 216-232. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01530 |

| [54] |

Persson M, Juhl K, Rasmussen P, et al. uPAR targeted radionuclide therapy with (177)Lu-DOTA-AE105 inhibits dissemination of metastatic prostate cancer[J]. Mol Pharm, 2014, 11(8): 2796-2806. DOI:10.1021/mp500177c |

| [55] |

Yu S, Huang G, Yuan R, et al. A uPAR targeted nanoplatform with an NIR laser-responsive drug release property for tri-modal imaging and synergistic photothermal-chemotherapy of triple-negative breast cancer[J]. Biomater Sci, 2020, 8(2): 720-738. DOI:10.1039/C9BM01495K |

| [56] |

Simón M, Jørgensen JT, Juhl K, et al. The use of a uPAR-targeted probe for photothermal cancer therapy prolongs survival in a xenograft mouse model of glioblastoma[J]. Oncotarget, 2021, 12(14): 1366-1376. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.28013 |

| [57] |

Gu W, Liu T, Fan D, et al. A6 peptide-tagged, ultra-small and reduction-sensitive polymersomal vincristine sulfate as a smart and specific treatment for CD44+ acute myeloid leukemia[J]. J Control Release, 2021, 329: 706-716. DOI:10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.10.005 |

| [58] |

Errico PA, Posteri R, Giansanti F, et al. Optimization of construct design and fermentation strategy for the production of bioactive ATF-SAP, a saporin based anti-tumoral uPAR-targeted chimera[J]. Microb Cell Fact, 2016, 15(1): 194-207. DOI:10.1186/s12934-016-0589-1 |

| [59] |

Zuppone S, Assalini C, Minici C, et al. The anti-tumoral potential of the saporin-based uPAR-targeting chimera ATF-SAP[J]. Sci Rep, 2020, 10(1): 2521-2533. DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-59313-8 |

| [60] |

Oh F, Modiano JF, Bachanova V, et al. Bispecific Targeting of EGFR and Urokinase Receptor (uPAR) Using Ligand-Targeted Toxins in Solid Tumors[J]. Biomolecules, 2020, 10(6): 965-978. DOI:10.3390/biom10060965 |

2023, Vol. 50

2023, Vol. 50