| 针刺治疗单侧基底节缺血性卒中后抑郁相关脑区效应连接变化:基于fMRI的格兰杰因果分析 |

2. 首都医科大学附属北京朝阳医院中医科, 北京 100020;

3. 北京中医药大学东直门医院脑病科, 北京 100700

2. TCM Department, Beijing Chaoyang Hospital of Capital Medical University, Beijing 100020, China;

3. Department of Encephalopathy, Dongzhimen Hospital of Beijing University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Beijing 100700, China

缺血性卒中是世界范围内成人致残、致死的主要原因[1],很多患者急性期后仍存在运动功能障碍[2-3]。卒中后抑郁在卒中发生后各时期普遍存在[4],但易被忽略,造成患者生活质量降低[5-6]。近年来,对卒中康复关注点由结构恢复逐步转向功能重塑[7-9],探讨卒中后抑郁的影像学特征和脑效应机制具有医学、心理、社会多重意义。梭状回-基底节-丘脑-小脑环路卒中后的表现与卒中后抑郁发生发展情况密切相关[10-12],其神经影像标志物演变过程尚待探索。

格兰杰因果分析(Granger causality analysis,GCA)可有效揭示脑区间信息传递方向性[13],近年来在抑郁症、癫痫等疾病中广泛应用,但在卒中后抑郁中应用较少。有关针刺在卒中后运动功能恢复过程中,如何影响抑郁相关脑区间格兰杰因果关系(Granger causality,GC)变化的机制尚未明确。本研究从双侧抑郁相关脑区功能正、负激活角度出发,围绕双侧梭状回、丘脑、小脑前下、基底神经节、小脑后下的静息态fMRI特征,并行GCA对比,以探讨脑功能恢复过程中针刺干预的大脑双侧性连接位点方向性特征与变化水平,为针灸在卒中治疗的应用提供依据。

1 资料与方法 1.1 一般资料纳入2018年12月至2023年9月北京中医药大学东直门医院收治的缺血性卒中后抑郁患者42例,发病时间 < 1.5个月,梗死病灶位于基底节和/或放射冠区域单侧运动通路,汉密尔顿抑郁量表评分8~23分。另招募28例与患者匹配的健康人作为对照组。本研究经医院伦理委员会批准(2022DZMEC-111-04),在中国临床试验注册中心注册(ChICTR1800016263),受试者或家属均签署知情同意书。

1.2 纳入及排除标准 1.2.1 纳入标准① 符合《中国脑血管病防治指南》[14]中脑梗死的诊断标准;②发病时间 < 1.5个月;③左侧或右侧偏瘫患者,病灶位于放射冠或基底节;④右利手;⑤年龄40~75岁,男女均可;⑥无意识障碍,病情相对平稳;⑦近1个月内未服用精神类药物。

1.2.2 排除标准① 合并心、肝、肾、血液、消化系统及高血压等严重原发性疾病者;②精神病、过敏体质、易合并感染及出血者;③孕妇、哺乳期及经期妇女;④无法配合检查或有MRI检查禁忌证;⑤MRI扫描发现严重的头颅解剖结构不对称或其他明确病变;⑥1个月内参加过类似神经影像学试验者。

1.3 剔除、脱落和中止标准① 剔除、脱落标准:受试者依从性差,MRI扫描中头动过大,无法配合试验。②中止标准:发生严重不良事件或并发症。

1.4 分组与针刺干预42例根据随机数字表法分为真穴组23例和假穴组19例。真穴组行手足十二针组穴针刺,即双侧合谷、内关、曲池、足三里、阳陵泉、三阴交;假穴组取上述穴位旁开1寸针刺;对照组未行针刺干预。

针刺选穴定位参照《腧穴名称与定位:GB/T 12346-2006》[15],采用毫针留针治疗,直刺进针,深度约1寸,以针下感觉明显阻滞感为宜,后采用平补平泻捻转手法,待患者得气后留针30 min。每日1次,治疗10次。针刺操作由同一位医师完成。

1.5 静息态fMRI数据采集3组均行静息态fMRI扫描,其中真穴组和假穴组于针刺前后分别扫描。使用Siemens Novus 3.0 T超导MRI扫描仪。受试者取仰卧位,头套固定以保持头位不动,维持视听封闭状态。①结构成像参数:采用T1WI序列,TR 1 900 ms,TE 2.52 ms,矩阵256×256,层厚1.0 mm,视野256 mm×256 mm,翻转角9°,扫描时间4 min 10 s。②BOLD成像参数:采用T2WI序列,TR 2 000 ms,TE 30 ms,矩阵256×256,层厚5.0 mm,视野225 mm×225 mm,翻转角90°,扫描时间8 min 10 s。

1.6 图像数据处理在Matlab 2023b平台应用工具包SPM12(https://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/)和DPABI V8.1(http://rfmri.org/dpabi)对fMRI数据行预处理,具体步骤:①将原始数据转换为NIFTI格式;②去除数据前10个时相图像;③以3 mm及3°作为头动阈值,行头动校正;④将图像与蒙特利尔神经病学研究所空间配准;⑤行空间平滑;⑥对线性信号回归;⑦行低通滤波。

从AAL_90脑区模板选取直径6 mm的球形区域作为VOI,包括大脑双侧梭状回、丘脑、小脑前下、基底神经节、小脑后下,配对成为VOI组,生成上述脑区掩膜,覆盖VOI,制作泛化模板。运用SPM 12工具rsHRF插件,读入原始图像,后设定重复时间、扫描层数、参考层、GCA类型、输出路径步骤,制作单样本模块。复制模块,读入单组样本数据行GCA。后提取经Fisher r-z变换的数据行统计分析。

1.7 统计学方法使用SPSS 23.0软件分析数据。连续变量组间比较行独立样本t检验,分类变量组间比较行χ2检验。以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

脑区间效应连接差异分析使用DPABI工具包(http://rfmri.org/dpabi),真穴组针刺后、假穴组针刺后、试验组针刺前分别与对照组的GC值比较行双样本t检验;结果行FDR校正、FEW校正,以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义,获取组间差异有统计学意义的种子点对。

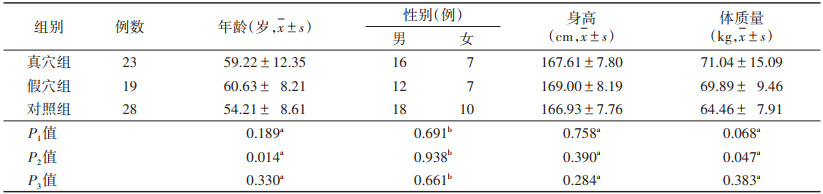

2 结果 2.1 3组人口学资料比较(表 1)| 表 1 3组人口学资料比较 |

|

真穴组与对照组年龄、身高、体质量、性别比较,差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05),具有可比性。假穴组与对照组年龄、体质量差异均有统计学意义(均P < 0.05),身高、性别差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05)。真穴组与假穴组年龄、身高、体质量、性别比较,差异均无统计学意义(均P>0.05),具有可比性。

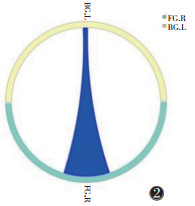

2.2 脑效应连接改变 2.2.1 假穴组针刺前后将假穴组针刺前后fMRI图像转化为数据集,预处理后行GCA,结果提示:假穴组针刺后右侧梭状回→左侧基底节的GC弱于针刺前,差异有统计学意义(P=0.008 1,t=-2.798 7);未见ROI间强化GC(图 1,2)。

|

| 注:箭头指向代表信号传递方向,粗细代表信息流强度,色带颜色代表信息流t值,FG为梭状回,Th为丘脑,AICb为小脑前下,BG为基底神经节,PICb为小脑后下,L为左侧,R为右侧 图 1 假穴组针刺前后格兰杰因果关系(GC)示意图 |

|

| 注:粗端→细端代表信号传递方向,红色代表正向信息传递,蓝色代表负向信息传递 图 2 假穴组针刺前后GC圈图 |

2.2.2 真穴组针刺前后

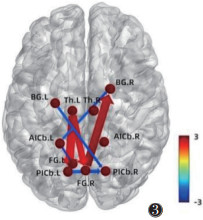

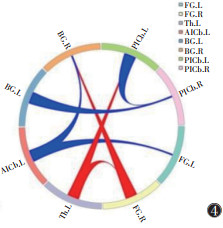

将真穴组针刺前后fMRI图像转化为数据集,预处理后行GCA,结果提示:真穴组针刺后左侧丘脑→右侧梭状回(P=0.030 0,t=2.242 1)、右侧梭状回→右侧基底节(P=0.010 6,t=2.668 7)、左侧丘脑→左侧小脑后下(P=0.038 8,t=2.129 5)的GC均强于针刺前,差异均有统计学意义。真穴组针刺后左侧小脑前下→左侧梭状回(P=0.018 7,t=-2.441 5)、左侧小脑前下→右侧基底节(P=0.048 4,t=-2.030 3)、左侧基底节→右侧小脑后下(P=0.033 8,t=-2.190 7)、左侧小脑后下→右侧小脑后下(P=0.048 1,t=-2.033 5)的GC均弱于针刺前,差异均有统计学意义(图 3,4)。

|

| 注:箭头指向代表信号传递方向,粗细代表信息流强度,色带颜色代表信息流t值 图 3 真穴组针刺前后GC示意图 |

|

| 注:粗端→细端代表信号传递方向,红色代表正向信息传递,蓝色代表负向信息传递 图 4 真穴组针刺前后GC圈图 |

2.2.3 假穴组针刺后与对照组

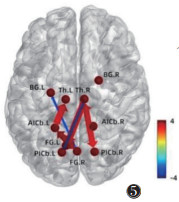

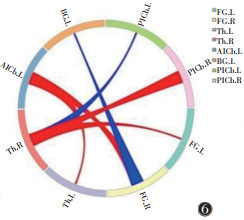

将假穴组、对照组针刺前fMRI图像转化为数据集,预处理后行GCA。结果提示,假穴组针刺前右侧丘脑→左侧梭状回(P=0.023 7,t=2.339 3)、左侧小脑前下→右侧梭状回(P=0.005 9,t=2.889 8)、左侧小脑前下→左侧丘脑(P=0.041 4,t=2.098 0)、右侧小脑后下→右侧丘脑(P=0.044 9,t=2.062 9)、右侧梭状回→左侧小脑前下(P=0.004 2,t=3.012 5)、右侧丘脑→右侧小脑后下(P=0.019 0,t=2.432 6)的GC均强于对照组,右侧梭状回→左侧基底节(P=0.016 9,t=-2.480 2)、右侧丘脑→左侧小脑后下(P=0.002 3,t=-3.220 6)的GC均弱于对照组,差异均有统计学意义(图 5,6)。

|

| 注:箭头指向代表信号传递方向,粗细代表信息流强度,色带颜色代表信息流t值,FG为梭状回,Th为丘脑,AICb为小脑前下,BG为基底神经节,PICb为小脑后下,L为左侧,R为右侧 图 5 假穴组针刺后与对照组格兰杰因果关系(GC)示意图 |

|

| 注:粗端→细端代表信号传递方向,红色代表正向信息传递,蓝色代表负向信息传递 图 6 假穴组针刺后与对照组GC圈图 |

2.2.4 真穴组针刺后与对照组

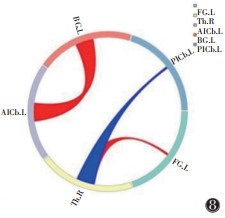

将真穴组、对照组针刺前fMRI图像转化为数据集,预处理后行GCA。结果提示,真穴组针刺前右侧丘脑→左侧梭状回(t=2.279 6,P=0.026 9)、左侧基底节→左侧小脑前下(t=2.611 5,P=0.011 7)、左侧小脑前下→左侧基底节(t=2.104 1,P=0.040 4)的GC值均强于对照组,右侧丘脑→左侧小脑后下(t=-2.314 9,P=0.024 8)的GC弱于对照组,差异均有统计学意义(均P < 0.05)(图 7,8)。

|

| 注:箭头指向代表信号传递方向,粗细代表信息流强度,色带颜色代表信息流t值 图 7 真穴组针刺后与对照组GC示意图 |

|

| 注:粗端→细端代表信号传递方向,红色代表正向信息传递,蓝色代表负向信息传递 图 8 真穴组针刺后与对照组GC圈图 |

3 讨论

本研究基于双侧梭状回、丘脑、小脑前下、基底神经节、小脑后下脑区探讨手足十二针治疗单侧基底节、放射冠卒中后的抑郁相关脑区间效应连接变化。GCA描述ROI间信息流方向和强度大小,可解释、预测脑区间信号传递模式。Cîrstian等[16]引入小波相干性特征建立静息态脑网络间GC,分析脑网络间异常功能动力学特征,并将其作为抑郁症分类诊断的影像学生物标志物。Mai等[17]基于GCA构建功能网络,利用模块化组织揭示早发型抑郁症和晚发型抑郁症大脑活动模式差异,从机制角度支持早发型和晚发型抑郁症治疗策略及预后的不同。因此,本研究基于双侧梭状回、丘脑、小脑前下、基底神经节、小脑后下,运用GCA观察单侧基底节、放射冠卒中后的抑郁相关脑区间GC关系变化,探讨单侧运动环路损伤后抑郁相关脑区间定向连接模式,从病理动力层面解释脑区间异常激活现象。

梭状回是社会脑重要组成部分[18],神经功能活动改变与焦虑、抑郁情绪密切相关[19-21],灰质体积缩小、厚度变薄可致快感缺失症状[22]。丘脑是皮质信息传递中转站,抑郁患者丘脑结构、功能及血流灌注情况均发生改变[23],是抑郁症干预的关键靶点[24]。基底节与卒中后抑郁发生发展息息相关,其纤维联络丘脑-大脑皮质[25],基底节损伤可通过中断锥外系统调节复杂行为、情绪的环路结构[26],并影响去甲肾上腺素、5-羟色胺等神经递质合成、转导,增加抑郁发生率[27]。小脑在情绪处理和感觉信息获取、分辨过程中发挥重要作用[28-34]。一般情况下,情绪处理功能发挥以任务需求为依据[35],梭状回、丘脑、小脑前下、基底神经节、小脑后下以不同方式动态相互作用,节点间协同作用能否发挥是卒中后偏瘫患者抑郁与否的关键。本研究提示,手足十二针疗程干预引发的左半球梭状回-丘脑-小脑前下-基底神经节-小脑后下环路节点直接激活和对其他节点的驱动作用,可能为卒中后抑郁情绪调控关键,环路间GC是准确预测卒中后抑郁情况的重要特征。

针刺对相关大脑结构具有区域特异性、可量化影响[36],对脑网络重构具有较强特异性[37]。然而,穴位及穴旁刺激疗效机制目前尚不明确。研究表明,穴位及穴旁刺激均可缓解临床症状,穴位刺激疗效较显著,两者与有显著预测作用的静息态功能连接特征不同[38-40]。本研究表明,穴旁刺激对脑区间效应连接激活效率低于真穴,且存在半球间激活代偿、激活滞后现象,可能与非经非穴处刺激阈值小、神经反射通路形成不完整有关,为穴位特异性提供了影像学证据。

综上所述,针刺后左半球抑郁相关脑区存在激活驱动属性和优先激活倾向;假穴对脑区间效应连接激活效率低于真穴,且存在半球间激活代偿、激活滞后,这为针刺治疗卒中后抑郁脑重塑-代偿机制及穴位特异性研究提供了新依据。

本研究存在以下不足:样本量偏小,结果存在部分偏倚,后续可扩大样本量行偏倚校正[41];针对组穴行fMRI研究,后续可就单穴或对穴行重复性针刺,分析针刺引起脑功能活动区域信号变化的可重复性;可进一步分析功能连接、局部一致性、低频振幅、比率低频振幅等影像学标志物或针刺干预对卒中后偏瘫患者抑郁相关脑区脑电图和MRI脑结构像的影响。

| [1] |

YU K, CHEN X F, GUO J, et al. Assessment of bidirectional relationships between brain imaging-derived phenotypes and stroke: a mendelian randomization study[J]. BMC Med, 2023, 21(1): 271. DOI:10.1186/s12916-023-02982-9 |

| [2] |

GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke and its risk factors, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2021, 20(10): 795-820. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00252-0 |

| [3] |

STINEAR C M, LANG C E, ZEILER S, et al. Advances and challenges in stroke rehabilitation[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2020, 19(4): 348-360. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30415-6 |

| [4] |

HACKETT M L, PICKLES K. Part Ⅰ: frequency of depression after stroke: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies[J]. Int J Stroke, 2014, 9(8): 1017-1025. DOI:10.1111/ijs.12357 |

| [5] |

KIPER P, PRZYSIĘŻNA E, CIEŚLIK B, et al. Effects of immersive virtual therapy as a method supporting recovery of depressive symptoms in post-stroke rehabilitation: randomized controlled trial[J]. Clin Interv Aging, 2022, 17: 1673-1685. DOI:10.2147/CIA.S375754 |

| [6] |

SADLONOVA M, WASSER K, NAGEL J, et al. Health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression up to 12 months post-stroke: influence of sex, age, stroke severity and atrial fibrillation - a longitudinal subanalysis of the find-afrandomised trial[J]. J Psychosom Res, 2021, 142: 110353. DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110353 |

| [7] |

SZELENBERGER R, KOSTKA J, SALUK-BIJAK J, et al. Pharmacological interventions and rehabilitation approach for enhancing brain self-repair and stroke recovery[J]. Curr Neuropharmacol, 2020, 18(1): 51-64. |

| [8] |

KWAKKEL G, STINEAR C, ESSERS B, et al. Motor rehabilitation after stroke: European Stroke Organisation (ESO) consensus-based definition and guiding framework[J]. Eur Stroke J, 2023, 8(4): 880-894. DOI:10.1177/23969873231191304 |

| [9] |

MOSKOWITZ M A, GROTTA J C, KOROSHETZ W J. Stroke progress review group, national institute of neurological disorders and stroke. the NINDS stroke progress review group final analysis and recommendations[J]. Stroke, 2013, 44(8): 2343-2350. DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001192 |

| [10] |

CHEN Z, ZHAO S, TIAN S, et al. Diurnal mood variation symptoms in major depressive disorder associated with evening chronotype: evidence from a neuroimaging study[J]. J Affect Disord, 2022, 298(Pt A): 151-159. |

| [11] |

CHEN Y, CHEN Y, ZHENG R, et al. Convergent molecular and structural neuroimaging signatures of first-episode depression[J]. J Affect Disord, 2023, 320: 22-28. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2022.09.132 |

| [12] |

VILLA R F, FERRARI F, MORETTI A. Post-stroke depression: Mechanisms and pharmacological treatment[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2018, 184: 131-144. DOI:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.11.005 |

| [13] |

ALLEGRA M, FAVARETTO C, METCALF N, et al. Stroke-related alterations in inter-areal communication[J]. Neuroimage Clin, 2021, 32: 102812. DOI:10.1016/j.nicl.2021.102812 |

| [14] |

饶明俐. 中国脑血管病防治指南[M]. 北京: 人民卫生出版社, 2007: 15-17.

|

| [15] |

中国国家标准化管理委员会. 腧穴名称与定位: GB/T 12346-2006[S]. 北京: 中国标准出版社, 2006.

|

| [16] |

CÎRSTIAN R, PILMEYER J, BERNAS A, et al. Objective biomarkers of depression: a study of granger causality and wavelet coherence in resting-state fMRI[J]. J Neuroimaging, 2023, 33(3): 404-414. DOI:10.1111/jon.13085 |

| [17] |

MAI N, WU Y, ZHONG X, et al. Different modular organization between early onset and late onset depression: a study base on granger causality analysis[J]. Front Aging Neurosci, 2021, 13: 625175. DOI:10.3389/fnagi.2021.625175 |

| [18] |

RIBEIRO-DOS-SANTOS A, DE BRITO L M, DE ARAÚJO G S. The fusiform gyrus exhibits differential gene-gene co-expression in Alzheimer's disease[J]. Front Aging Neurosci, 2023, 15: 1138336. DOI:10.3389/fnagi.2023.1138336 |

| [19] |

GONG L, HE C, YIN Y, et al. Nonlinear modulation of interacting between COMT and depression on brain function[J]. Eur Psychiatry, 2017, 45: 6-13. DOI:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.05.024 |

| [20] |

VAN GEEST Q, BOESCHOTEN R E, KEIJZER M J, et al. Fronto-limbic disconnection in patients with multiple sclerosis and depression[J]. Mult Scler, 2019, 25(5): 715-726. DOI:10.1177/1352458518767051 |

| [21] |

GALOVIC M, BAUDRACCO I, WRIGHT-GOFF E, et al. Association of piriform cortex resection with surgical outcomes in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy[J]. JAMA Neurol, 2019, 76(6): 690-700. DOI:10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0204 |

| [22] |

SCHMAAL L, HIBAR D P, SÄMANN P G, et al. Cortical abnormalities in adults and adolescents with major depression based on brain scans from 20 cohorts worldwide in the ENIGMA major depressive disorder working group[J]. Mol Psychiatry, 2017, 22(6): 900-909. DOI:10.1038/mp.2016.60 |

| [23] |

张蕾, 赵莲萍, 刘斯润, 等. 分析未治疗抑郁症患者丘脑及基底核微观结构和血流灌注[J]. 中国医学影像技术, 2018, 34(2): 176-180. |

| [24] |

YANG C, XIAO K, AO Y, et al. The thalamus is the causal hub of intervention in patients with major depressive disorder: evidence from the granger causality analysis[J]. Neuroimage Clin, 2023, 37: 103295. DOI:10.1016/j.nicl.2022.103295 |

| [25] |

黄小茜. 卒中后抑郁的神经影像学研究[D]. 唐山: 华北理工大学, 2020.

|

| [26] |

KIM J S, CHOI-KWON S. Poststroke depression and emotional incontinence: correlation with lesion location[J]. Neurology, 2000, 54(9): 1805-1810. DOI:10.1212/WNL.54.9.1805 |

| [27] |

徐丽娟, 李海燕, 田军彪, 等. 益智解郁汤联合草酸艾司西酞普兰对脑卒中后抑郁的疗效观察[J]. 中华中医药杂志, 2021, 36(4): 2419-2422. |

| [28] |

GOLD A K, TOOMEY R. The role of cerebellar impairment in emotion processing: a case study[J]. Cerebellum Ataxias, 2018, 5: 11. DOI:10.1186/s40673-018-0090-1 |

| [29] |

GAO J H, PARSONS L M, BOWER J M, et al. Cerebellum implicated in sensory acquisition and discrimination rather than motor control[J]. Science, 1996, 272(5261): 545-547. DOI:10.1126/science.272.5261.545 |

| [30] |

ZENG M, YU M, QI G, et al. Concurrent alterations of white matter microstructure and functional activities in medication-free major depressive disorder[J]. Brain Imaging Behav, 2021, 15(4): 2159-2167. DOI:10.1007/s11682-020-00411-6 |

| [31] |

ZHENG R, CHEN Y, JIANG Y, et al. Dynamic altered amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations in patients with major depressive disorder[J]. Front Psychiatry, 2021, 12: 683610. DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.683610 |

| [32] |

ALALADE E, DENNY K, POTTER G, et al. Altered cerebellar-cerebral functional connectivity in geriatric depression[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(5): e20035. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0020035 |

| [33] |

MA Q, ZENG L L, SHEN H, et al. Altered cerebellar-cerebral resting-state functional connectivity reliably identifies major depressive disorder[J]. Brain Res, 2013, 1495, 86-94. |

| [34] |

ALALADE E, DENNY K, POTTER G, et al. Altered cerebellar-cerebral functional connectivity in geriatric depression[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(5): e20035. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0020035 |

| [35] |

GOLDIN P R, THURSTON M, ALLENDE S, et al. Evaluation of cognitive behavioral therapy vs mindfulness meditation in brain changes during reappraisal and acceptance among patients with social anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA Psychiatry, 2021, 78(10): 1134-1142. DOI:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1862 |

| [36] |

KAPTCHUK T J. Acupuncture: theory, efficacy, and practice[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2002, 136(5): 374-383. DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00010 |

| [37] |

LI K, WANG J, LI S, et al. Latent characteristics and neural manifold of brain functional network under acupuncture[J]. IEEE Trans Neural Syst Rehabil Eng, 2022, 30: 758-769. DOI:10.1109/TNSRE.2022.3157380 |

| [38] |

WANG X, LI J L, WEI X Y, et al. Psychological and neurological predictors of acupuncture effect in patients with chronic pain: a randomized controlled neuroimaging trial[J]. Pain, 2023, 164(7): 1578-1592. DOI:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002859 |

| [39] |

MAEDA Y, KIM H, KETTNER N, et al. Rewiring the primary somatosensory cortex in carpal tunnel syndrome with acupuncture[J]. Brain, 2017, 140(4): 914-927. DOI:10.1093/brain/awx015 |

| [40] |

TU Y, ORTIZ A, GOLLUB R L, et al. Multivariate resting-state functional connectivity predicts responses to real and sham acupuncture treatment in chronic low back pain[J]. Neuroimage Clin, 2019, 23: 101885. DOI:10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101885 |

| [41] |

LIN H, XIANG X, HUANG J, et al. Abnormal degree centrality values as a potential imaging biomarker for major depressive disorder: a resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging study and support vector machine analysis[J]. Front Psychiatry, 2022, 13: 960294. DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2022.960294 |

2025, Vol. 23

2025, Vol. 23