文章信息

- 李生.

- LI Sheng.

- 金属离子对细胞自噬的诱导作用

- The Induction Effect of Metal Ions for Cell Autophagy

- 中国生物工程杂志, 2017, 37(7): 124-132

- China Biotechnology, 2017, 37(7): 124-132

- http://dx.doi.org/DOI:10.13523/j.cb.20170719

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2017-03-24

- 修回日期: 2017-05-02

1962年,Ashford和Porten通过电子显微镜在人的干细胞观察到细胞存在“自己吃自己”现象,但限于当时科学技术条件,人们对这种现象知之甚少[1],直到1993年大隅良典(Yoshinori Ohsumi)从面包酵母中鉴别出了自噬相关基因(atg)[2],有关自噬的研究才得以迅速发展。随着研究的深入,自噬在生理学和医学上的重要性日益凸显,大隅良典也因在自噬溶酶体方面的卓越贡献获得了2016年的诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。自噬可分为三种不同种类:巨自噬、微自噬及分子伴侣介导的自噬。巨自噬是一种高度保守的生物过程,是清除异常蛋白质及细胞器的主要途径,通常所说的自噬就是巨自噬[3-4]。微自噬是溶酶体膜随机内陷包裹周围细胞质的一种非选择性溶酶体降解途径[5-7]。分子伴侣介导的自噬(CMA)是可溶性蛋白质在分子伴侣介导下进入溶酶体降解,故CMA具有选择性,能够直接、定向地降解细胞组份[8-9]。自噬在维持细胞稳态、质量控制、防止细胞内外损伤及维持能量平衡中发挥着重要作用[10-12]。

当细胞面临饥饿、生长因子缺乏、缺氧等代谢压力、遭到电离辐射或化学毒物损伤时,细胞质中形成双层膜新月形的自噬前体,自噬前体逐渐形成囊腔并包裹目标蛋白质及细胞器,形成自噬小体。自噬小体与溶酶体融合成自噬溶酶体,其内含物被溶酶体内的酸性水解酶降解,降解产生的氨基酸等产物既可以用于蛋白质等大分子的生物合成,也可以进入线粒体彻底氧化分解,从而为细胞的的生命活动提供原料和能量,促进细胞的存活[10-12],但过度的自噬会导致细胞凋亡[13]。自噬相关基因(atg)在自噬过程中起关键作用,基因家族首先在酵母中被发现,到目前为止已被发现30多个成员,其中大部分基因在线虫、果蝇和哺乳动物细胞内有同源物。atg家族蛋白能够彼此结合形成复合物,在自噬的起始阶段、自噬体的形成和自噬体的成熟降解三个阶段发挥重要作用[14]。自噬过程的异常可导致肿瘤、糖尿病、神经退行性疾病等多种疾病的发生[15]。

金属离子广泛参与光合作用、呼吸作用、核酸代谢、酶的催化、维持渗透压等各种生理过程,它是细胞维持正常生命活动所必需的[16]。金属离子还与细胞自噬密切相关,可以通过浓度变化诱导自噬,自噬也会影响细胞内金属离子的浓度[17]。研究细胞自噬的分子机制及金属离子的诱导作用不仅有利于了解自噬的本质及其生理意义,更有利于揭示多种疾病发生、发展过程,从而为治疗多种疾病寻求潜在治疗方法。

1 细胞自噬的分子机制 1.1 mTOR信号通路mTOR是一种丝氨酸/苏氨酸蛋白激酶,它是氨基酸、生长因子、胰岛素等的感受器,参与调节细胞生长、发育、增殖、自噬、凋亡过程[18-19]。哺乳动物细胞内mTOR主要以雷帕霉素敏感型的mTOR复合体1(mTORC1) 和雷帕霉素非敏感型的mTOR复合体2(mTORC2) 两种形式存在,mTORC1与细胞自噬有关,在本文中的mTOR即为mTORC1。

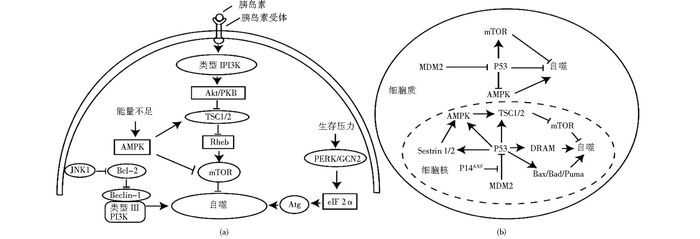

细胞处于正常状态时,胰岛素等生长因子浓度适中,其与细胞表面受体结合后,激活磷脂酰肌醇激酶PI3K,进而活化Akt激酶,通过结节性硬化症相关蛋白TSC1/2及G蛋白Rheb激活蛋白激酶mTOR(图 1a)[20]。mTOR可以作为自噬的抑制物,不仅阻止Atg1-Atg13-Atg17复合物和mVps34-Beclin-1复合物形成,还干扰自噬形成过程中两类泛素化系统,从而抑制自噬的发生[21]。机体面临代谢压力时,胰岛素等生长因子浓度降低,PI3K不能被激活,最终mTOR失活,Atg相关蛋白活化,促进细胞自噬[20]。细胞能量状态同样能通过mTOR调控细胞自噬,当细胞处于能量缺乏时,AMP/ATP升高,激活AMPK,活化的AMPK既可以通过磷酸化激活TSC1/2复合物,从而抑制mTOR,也可以直接磷酸化抑制mTOR活性,促进细胞自噬[22]。

Beclin-1是酵母atg6的同源基因,是细胞自噬过程中重要的正调节因子。Beclin-1含BH3结构域、螺旋-螺旋结构域(CCD)、进化保守结构域(ECD)、核输出结构域,并通过这些结构域与Bcl-2、Ⅲ型磷脂酰肌醇-3-磷酸激酶(mVps34)、Bif -1、UVRAG、Barkor等相互作用调控自噬[23-26]。Bcl-2是一种抗凋亡蛋白,能与Beclin-1的BH3结构域结合成Bcl-2-Beclin-1复合物,抑制Beclin-1的活性,从而抑制细胞自噬。在饥饿状态下,应激活化蛋白激酶JNK1磷酸化Bcl-2,导致Bcl-2-Beclin-1复合物解离,从而促进细胞自噬(图 1a)[27]。

1.3 真核翻译起始因子2α当细胞面临紫外照射、饥饿、低氧、营养因子缺乏等生存压力时,蛋白激酶R样内质网激酶(PERK)或一般性调控阻遏蛋白激酶2(GCN2)磷酸化真核翻译起始因子2α(eIF2α),抑制绝大多数基因的转录,同时活化激活转录因子4(ATF4),优先翻译一系列Atg相关蛋白,如Atg1、Atg3、Atg5、Atg7、Atg10、Atg12等,从而促进细胞自噬(图 1a)[28-32]。

1.4 P53基因的双重调节作用P53基因对细胞自噬具有双重调节作用,细胞质中抑制细胞凋亡,细胞核中促进细胞凋亡。细胞核中P53既可以反式激活AMPK的β1和β2两个亚基、TSC1/2、AMPK的激活因子Sestrin 1和2,通过抑制mTOR的活性来促进细胞自噬[33-35],也可通过反式激活损伤调节自噬调制物DRAM, 促进细胞自噬。泛素化水解酶MDM2能水解P53,但细胞核内也存在P14ARF能与MDM2结合阻止其对P53的降解,使细胞核内的P53浓度不至于太低[36]。P53还可以反式激活促凋亡蛋白Bcl-2家族Bax、Bad、Puma等,通过使Bcl-2-Beclin-1复合物解离,促进细胞自噬[37]。在细胞质中,P53通过自身直接发挥作用、通过激活mTOR以及抑制AMPK的活性来抑制细胞自噬[38]。细胞质中的MDM2水解P53,减少P53对细胞自噬的抑制作用(图 1b)[38]。

2 金属离子对自噬的诱导作用细胞正常生理功能依赖于多种金属离子,宏量金属离子包括钙离子、钾离子以及钠离子;微量金属离子包括铁离子、铜离子、锌离子、锰离子及钼离子等。近年来发现金属离子能够诱导细胞自噬,有毒重金属离子对细胞具有毒害作用,故我们将其单列出来进行综述。

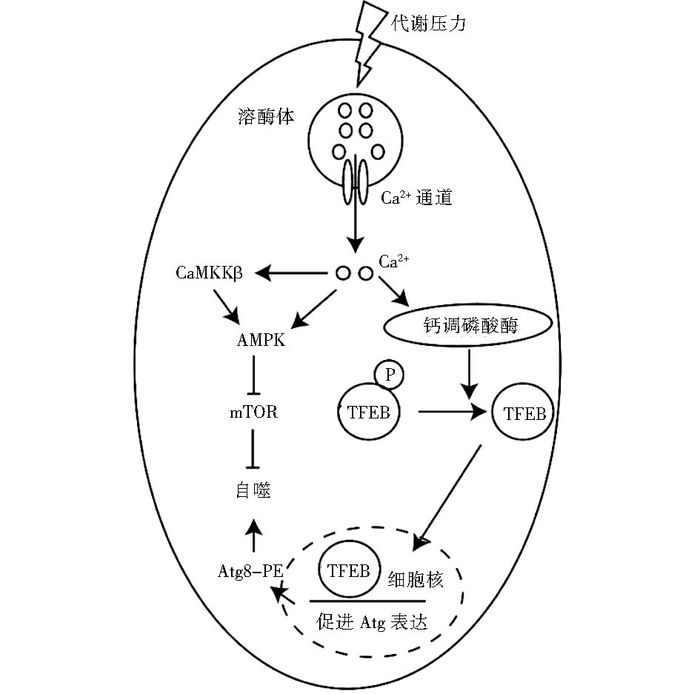

2.1 宏量金属离子对自噬的诱导作用正常细胞细胞质Ca2+浓度低,而在肌质网(内质网)等细胞器Ca2+浓度很高,细胞器Ca2+通道通过开启和闭合调节Ca2+浓度变化,进而调控细胞分泌活动、神经冲动传导、肌肉收缩等多种生理过程[40]。近年发现,Ca2+浓度变化对自噬也有着重要作用。Sukumaran等[41]发现当细胞面临缺氧、营养剥夺等代谢压力时,瞬时受体电位通道1(MCOLIN1)开放导致的Ca2+外流,细胞质内Ca2+浓度提高,既可以直接活化AMPK酶[42-43],也可以通过先活化Ca2+依赖的激酶CaMKKβ继而激活AMPK,活化的AMPK通过抑制mTOR介导自噬的发生发展[44-45]。溶酶体Ca2+在营养剥夺介导的自噬中发挥重要作用,营养缺乏导致溶酶体中Ca2+的释放,释放的Ca2+激活钙调磷酸酶,钙调磷酸酶去磷酸化激活转录因子EB(TFEB),进而促进核定位并最终激活自噬相关基因,Atg8-PE(LC3Ⅱ)上调促进自噬(图 2)[46-47]。

|

| 图 2 Ca2+对细胞自噬的诱导作用 Figure 2 The induction effect of calcium ions |

钾离子在维持细胞渗透平衡等正常生理功能上发挥重要作用[48],近来越来越多的研究发现其在自噬中同样发挥重要作用。Perez-Neut等[49]使用小分子激活剂NS1643激活黑色素瘤细胞质膜钾离子通道hERG3,钾离子外流不仅促使自噬诱导因子Atg8-PE(LC3-Ⅱ)的积累,而且激活AMPK,AMPK磷酸化激活ULK1,促进细胞自噬。钾离子剥夺也能诱导小脑颗粒细胞自噬的发生[50-51]。

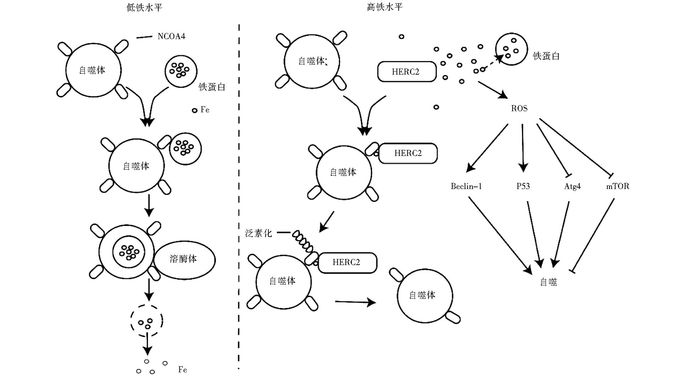

2.2 微量金属离子对自噬的诱导作用铁离子是微量金属元素中最常见的一种元素,在几乎所有生物系统中均发挥重要作用[52],细胞中铁离子过量将导致氧化应激的发生,产生活性氧自由基(ROS),导致自噬的发生[53]。铁离子浓度过高或过低都影响正常的生理活动,细胞通过控制铁离子储存蛋白(铁蛋白)的降解来维持正常的铁离子浓度。当铁离子水平低时,自噬体表面的核受体辅助活化因子4(NCOA4) 数量增加,NCOA4与铁蛋白结合,铁蛋白和自噬体被溶酶体酸性水解酶降解,释放铁离子至细胞质以提高铁离子浓度,此过程即为铁蛋白自噬。当铁离子水平高时,泛素蛋白连接酶HERC2通过泛素化降解NCOA4,导致自噬体表面NCOA4数量降低,从而抑制铁蛋白降解和铁离子释放[52]。同时细胞溶质中存在多种铁离子结合蛋白,如铁蛋白等,能结合额外铁离子,从而降低细胞对氧化应激的敏感性[54]。铁离子价态不稳定可以通过Fenton和Haber-Weiss反应产生ROS, ROS通过与Beclin-1、P53、Atg4、mTOR等相互作用导致细胞自噬(图 3)[55]。溶酶体富含低分子质量铁离子,使得溶酶体易受ROS攻击,从而导致溶酶体膜通透性增加[56]。早期实验发现自噬有利于促进细胞存活,然而近期多项研究发现自噬同样能促进细胞死亡。铁死亡即为自噬介导细胞死亡的一种通路[57],是程序性细胞坏死的一种类型,该过程依赖于铁离子介导的ROS的产生。

|

| 图 3 铁离子对自噬的诱导作用 Figure 3 The induction effect of iron ions |

铜离子在多种细胞生理功能中起着重要作用[58],其在两种不同的氧化态间的循环导致ROS的产生[59],从而诱导自噬的发生[60]。Gutierrez等[61]发现抗肿瘤药物缩氨基硫脲铜配合物Cu-Dp44mT通过两种方式影响自噬,它既可诱导自噬体的形成,进而增加Atg8-PE(LC3-Ⅱ)的表达,也可通过自噬底物和受体p62的积累以减少自噬体的降解。Dp44mT对自噬体降解的抑制作用会干扰促进细胞存活的自噬过程,诱导肿瘤细胞死亡。Zhong等[62]发现一种新的抗肿瘤复合物HYF127c/Cu也可促进肿瘤细胞自噬,它通过激活MAPK11/12/13/14信号路径发挥作用。类似的复合物NSC689534[63]、BNMPH[64]、Casiopeina Ⅲ-ia[65]等也能诱导肿瘤细胞的自噬,对这些复合物的研究将有利于开发基于自噬的新的抗肿瘤药物。

研究发现高浓度的锌离子会促进细胞自噬,低浓度的锌离子会抑制自噬, 锌离子通过自噬对细胞起保护作用。高浓度的锌离子促进酒精诱导的肝癌细胞中自噬泡的形成,它还与多巴胺诱导PC12细胞自噬的发生[66],促进三苯氧胺诱导的乳腺癌细胞中自噬体的形成。锌离子螯合剂TPEN的使用导致其浓度降低,能抑制自噬体的成熟降解进程。在哺乳动物细胞中,高浓度的锌离子会减轻由脂多糖引发的炎症反应,而低浓度的锌离子会加重炎症反应[67]。同样,在小鼠的巨噬细胞中,锌离子的缺乏会激活caspase-1促使细胞凋亡[68]。锌离子可通过细胞外调节蛋白激酶(ERK1/2) 对自噬进行调控,ERK1/2既可磷酸化激活Beclin-1,也可以促进mTOR的降解来诱导自噬。此外,锌离子还可能通过金属反应转录因子(MTF-1) 促进自噬相关基因的表达间接调控自噬进程,如Atg7基因的启动子上有4个MTF-1结合位点,该基因的表达会受到锌和MTF-1的诱导[69]。锌指蛋白是一类能结合锌离子的转录因子,因其可结合某些DNA或RNA, 故可调控基因表达。Li等[70]发现上调人乳腺癌细胞中锌指蛋白ZNF32的表达,导致锌离子浓度降低,可能促进PI3K的表达及激活AKT/mTOR从而抑制自噬促进细胞存活,但其具体作用机制还需要进一步研究确认。相反地,通过转染小干扰RNA降低ZNF32的表达,导致锌离子浓度升高,会促进细胞自噬。

锰离子、钼离子、钴离子等同样影响自噬过程。锰离子介入增加细胞自噬过程,自噬的发生可能与细胞避免锰离子引起的氧化应激损伤的保护性策略有关[71]。然而Zhang等[72]发现,锰离子对细胞自噬过程起双向调节作用:小鼠锰离子介导的神经退行性疾病中,TH免疫反应神经元经短期(4~12h)锰离子处理,促进自噬发生;长期(1~28d)处理后,抑制自噬过程发生。自噬在锰离子诱导的支气管上皮细胞凋亡过程中起保护作用[73]。新型抗肿瘤锰离子化合物Adpa-Mn,主要通过诱导细胞自噬导致细胞凋亡,其选择性优于传统的化疗药物顺氯氨铂(CDDP)。体外实验表明,它不仅可以激活DNA修复蛋白聚腺苷酸二磷酸核糖转移酶PARP,也可以增强自噬相关蛋白LC3表达。此外,它可以诱导ROS产生,当用抗氧化剂N-乙酰半胱氨酸处理后其抗肿瘤效果显著降低,表明其主要通过ROS发挥抗肿瘤作用。体内实验表明,当Adpa-Mn给药量为10mg/kg时,可诱导肿瘤组织中细胞自噬和凋亡,从而发挥显著的抗肿瘤活性[74]。Ogata等[75]发现聚氧钼酸盐PM-17可诱导人胰腺癌细胞AsPC-1自噬,然而自噬的抑制剂3-甲基腺嘌呤对PM-17引起自噬无明显影响,提示PM-17可能通过一种未知机制促进细胞自噬。

Yang等[76]发现视网膜神经节细胞经低氧模拟剂氯化钴孵育后,细胞中自噬体的数量增加,而经氧化剂N-乙酰半胱氨酸(NAC)预孵育后该现象明显降低。氯化钴诱导的自噬在绒毛外滋养细胞植入子宫中起重要作用。然而,钴离子氯化物诱导的自噬与胆管癌及腺样囊性癌细胞转移有关,可见自噬对癌症转移的治疗可能存在不利影响[77-78]。Naves等[79]研究表明,氯化钴诱导神经母细胞瘤细胞自噬的发生,保护细胞免受活性氧的影响。综上所述,自噬作用在金属离子对细胞毒性作用及氧化应激中起保护作用。

2.3 有毒重金属对自噬的诱导作用铅、砷、镉等有毒重金属同样能诱导自噬的发生,自噬过程有利于保护细胞免受重金属诱导的应激损伤[80-82]。Sui等[83]发现,铅离子对心成纤维细胞产生细胞毒性,通过抑制mTOR信号通路增加自噬现象,应用3-MA抑制自噬过程可增加铅离子产生的细胞毒性。成骨细胞及巨噬细胞经铅离子处理后,自噬现象增加[84-85],上述实验均表明自噬现象对细胞具有保护作用。

砷化合物诱导细胞自噬和凋亡,这取决于砷化合物的暴露剂量及细胞系。Bolt等[86]研究发现,在淋巴母细胞系中,砷暴露导致含p62和LC3的蛋白质聚集体积累,内质网应激(ER)激活未折叠蛋白响应(UPR),PERK磷酸化eIF2α,磷酸化的eIF2α激活ATF4,表达一系列自噬相关基因,促进细胞自噬。Cheng等[87]证实,三氧化二砷能上调人白血病细胞K562中LC3和Beclin-1的表达促进自噬,同时还能下调抗凋亡蛋白Bcl-2的表达,从而表现抗肿瘤的效果。Kanzawa等[88]将三氧化二砷和自噬抑制剂巴佛洛霉素A处理人胶质瘤细胞,发现抑制促进细胞存活的自噬作用会显著增强前者的抗肿瘤活性。最新的研究表明,低浓度亚砷酸钠通过诱导神经细胞自噬来增强空间学习[89]。

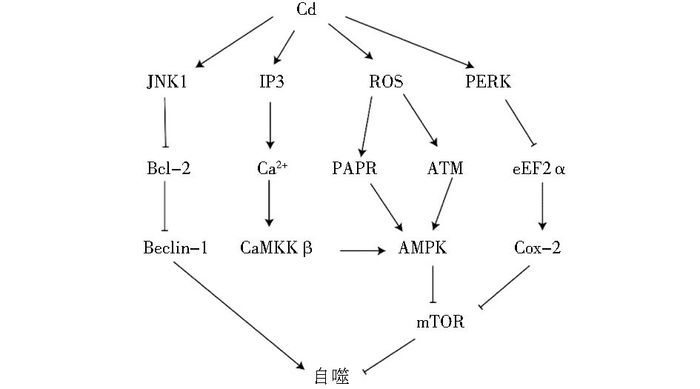

镉是有毒重金属,接触会诱导细胞凋亡或者癌症的发生,且呈剂量和时间依赖性[90]。近年来有研究表明镉还能诱导细胞自噬。线粒体是ROS产生的主要场所,呼吸链泄露的少量电子会与氧结合生成ROS。Son等[91]发现镉能通过线粒体上调ROS,ROS会对核酸等大分子造成损伤,DNA损伤激活DNA修复蛋白聚腺苷酸二磷酸核糖转移酶PAPR,下调NAD+,抑制糖酵解导致ATP降低,激活肝激酶B1(LKB1),活化的LKB1磷酸化激活AMPK,进而抑制mTOR,促进细胞自噬。Wei等[92]证实镉通过活化JNK1磷酸化失活Bcl-2,继而活化Beclin-1促进细胞自噬。Alexander等[93]发现ROS会活化共济失调突变蛋白ATM,激活LKB1-AMPK信号通路促进细胞凋亡。镉还可以通过调节其他金属离子的浓度变化间接促进细胞自噬。Misra等发现镉离子会上调肌醇三磷酸(IP3),进而打开内质网IP3门控的Ca2+通道,上调细胞质内的Ca2+,激活CaMKKβ,活化AMPK,促进细胞自噬[94-96]。镉诱导内网应激反应激活eIF2α-ATF4信号通路,促进环氧酶2(COX-2) 过表达,抑制mTOR, 促进细胞自噬(图 5)[97]。

|

| 图 4 镉离子对自噬的诱导作用 Figure 4 The induction effect of cadmium ions |

细胞通过自噬清除变性或错误折叠的蛋白质、衰老或损伤的细胞器等以维持细胞内稳态。自噬还是一种生理性保护机制,当细胞面临生存压力时,通过自噬降解自身蛋白质等大分子或细胞器为细胞的生命活动提供原料和能量,促进细胞存活。研究发现自噬过程异常会引起器官损伤及疾病。异常的细胞内自噬使得错误折叠的异常蛋白质堆积于细胞质、细胞核或细胞外基质中,导致细胞损伤,与帕金森病、阿尔兹海默病、亨廷顿病、肌肉萎缩性侧索硬化症等疾病的发生发展有关[13, 15]。

有关细胞自噬的分子机制的研究能从分子水平阐明自噬的本质,有利于寻找新的药物作用靶点为治疗疾病提供理论依据。金属离子可以通过各种信号通路诱导自噬,自噬也会影响金属离子的浓度,研究金属离子对细胞自噬的诱导作用不仅有利于进一步阐明自噬的分子机制,也为开发新药和治疗疾病提供契机。自噬的研究还处于初级阶段,随着研究的深入,我们期待能通过控制自噬过程对神经系统疾病、肿瘤等多种疾病起到有效的治疗作用。

| [1] |

Klionsky D J. Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2007, 8(11): 931-937. DOI:10.1038/nrm2245 |

| [2] |

Nakatogawa H, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, et al. Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: lessons from yeast. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2009, 10(7): 458-467. DOI:10.1038/nrm2708 |

| [3] |

Feng Y, He D, Yao Z, et al. The machinery of macroautophagy. Cell Research, 2014, 24(1): 24-41. DOI:10.1038/cr.2013.168 |

| [4] |

Ravikumar B, Futter M, Jahreiss L, et al. Mammalian macroautophagy at a glance. Journal of Cell Science, 2009, 122(11): 1707-1711. DOI:10.1242/jcs.031773 |

| [5] |

Shpilka T, Elazar Z. Shedding light on mammalian microautophagy. Developmental Cell, 2011, 20(1): 1-2. DOI:10.1016/j.devcel.2010.12.010 |

| [6] |

Li W W, Li J, Bao J K. Microautophagy: lesser-known self-eating. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2012, 69(7): 1125-1136. DOI:10.1007/s00018-011-0865-5 |

| [7] |

Mijaljica D, Prescott M, Devenish R J. Microautophagy in mammalian cells: revisiting a 40-year-old conundrum. Autophagy, 2011, 7(7): 673-682. DOI:10.4161/auto.7.7.14733 |

| [8] |

Xie W, Zhang L, Jiao H, et al. Chaperone-mediated autophagy prevents apoptosis by degrading BBC3/PUMA. Autophagy, 2015, 11(9): 1623-1635. DOI:10.1080/15548627.2015.1075688 |

| [9] |

Scarlatti F, Granata R, Meijer A, et al. Does autophagy have a license to kill mammalian cells. Cell Death & Differentiation, 2009, 16(1): 12-20. |

| [10] |

Zhang S J, Yang W, Wang C, et al. Autophagy: A double-edged sword in intervertebral disk degeneration. Clinica Chimica Acta, 2016, 457: 27-35. DOI:10.1016/j.cca.2016.03.016 |

| [11] |

Hamacher-Brady A. Autophagy regulation and integration with cell signaling. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 2012, 17(5): 756-765. |

| [12] |

Klionsky D J, Abdelmohsen K, Abe A, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy, 2016, 12(1): 1-222. DOI:10.1080/15548627.2015.1100356 |

| [13] |

Maiuri M C, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, et al. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2007, 8(9): 741-752. DOI:10.1038/nrm2239 |

| [14] |

钱帅伟, 罗艳蕊, 漆正堂, 等. 细胞自噬的分子学机制及运动训练的调控作用. 体育科学, 2012, 32(1): 64-70. Qian S W, Luo Y R, Qi Z T, et al. The molecular mechanism of autophagy and exercise-related molecular regulatory role. China Sport Science, 2012, 32(1): 64-70. |

| [15] |

Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell, 2008, 132(1): 27-42. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.018 |

| [16] |

Maret W. The metals in the biological periodic system of the elements: Concepts and conjectures. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2016, 17(1): 66. DOI:10.3390/ijms17010066 |

| [17] |

Sahni S, Bae D H, Jansson P, et al. The Mechanistic Role of Chemically Diverse Metal Ions in the Induction of Autophagy. Pharmacological Research, 2017, 119: 118-127. DOI:10.1016/j.phrs.2017.01.009 |

| [18] |

Rosner M, Hanneder M, Siegel N, et al. The mTOR pathway and its role in human genetic diseases. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research, 2008, 659(3): 284-292. DOI:10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.06.001 |

| [19] |

Sarbassov D D, Ali S M, Sabatini D M. Growing roles for the mTOR pathway. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 2005, 17(6): 596-603. DOI:10.1016/j.ceb.2005.09.009 |

| [20] |

Nakao R, Hirasaka K, Goto J, et al. Ubiquitin ligase Cbl-b is a negative regulator for insulin-like growth factor 1 signaling during muscle atrophy caused by unloading. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 2009, 29(17): 4798-4811. DOI:10.1128/MCB.01347-08 |

| [21] |

Jung C H, Ro S H, Cao J, et al. mTOR regulation of autophagy. FEBS Letters, 2010, 584(7): 1287-1295. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2010.01.017 |

| [22] |

Gwinn D M, Shackelford D B, Egan D F, et al. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Molecular Cell, 2008, 30(2): 214-226. DOI:10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003 |

| [23] |

Kang R, Zeh H, Lotze M, et al. The Beclin 1 network regulates autophagy and apoptosis. Cell Death & Differentiation, 2011, 18(4): 571-580. |

| [24] |

Thoresen S B, Pedersen N M, Liestøl K, et al. A phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase class Ⅲ sub-complex containing VPS15, VPS34, Beclin 1, UVRAG and BIF-1 regulates cytokinesis and degradative endocytic traffic. Experimental Cell Research, 2010, 316(20): 3368-3378. DOI:10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.07.008 |

| [25] |

Takahashi Y, Coppola D, Matsushita N, et al. Bif-1 interacts with Beclin 1 through UVRAG and regulates autophagy and tumorigenesis. Nature Cell Biology, 2007, 9(10): 1142-1151. DOI:10.1038/ncb1634 |

| [26] |

Sun Q, Fan W, Chen K, et al. Identification of Barkor as a mammalian autophagy-specific factor for Beclin 1 and class Ⅲ phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2008, 105(49): 19211-19216. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0810452105 |

| [27] |

Ciechomska I, Goemans G, Skepper J, et al. Bcl-2 complexed with Beclin-1 maintains full anti-apoptotic function. Oncogene, 2009, 28(21): 2128-2141. DOI:10.1038/onc.2009.60 |

| [28] |

Boyce M, Bryant K F, Jousse C, et al. A selective inhibitor of eIF2α dephosphorylation protects cells from ER stress. Science, 2005, 307(5711): 935-939. DOI:10.1126/science.1101902 |

| [29] |

Novoa I, Zeng H, Harding H P, et al. Feedback inhibition of the unfolded protein response by GADD34-mediated dephosphorylation of eIF2α. The Journal of Cell Biology, 2001, 153(5): 1011-1022. DOI:10.1083/jcb.153.5.1011 |

| [30] |

Tallóczy Z, Jiang W, Virgin H W, et al. Regulation of starvation-and virus-induced autophagy by the eIF2α kinase signaling pathway. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2002, 99(1): 190-195. DOI:10.1073/pnas.012485299 |

| [31] |

Koumenis C, Naczki C, Koritzinsky M, et al. Regulation of protein synthesis by hypoxia via activation of the endoplasmic reticulum kinase PERK and phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 2002, 22(21): 7405-7416. DOI:10.1128/MCB.22.21.7405-7416.2002 |

| [32] |

B'chir W, Maurin A C, Carraro V, et al. The eIF2α/ATF4 pathway is essential for stress-induced autophagy gene expression. Nucleic Acids Research, 2013, 41(16): 7683-7699. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkt563 |

| [33] |

D'Amelio M, Cecconi F. A novel player in the p53-mediated autophagy: Sestrin2. Cell Cycle, 2009, 8(10): 1466-1470. |

| [34] |

Maiuri M C, Malik S A, Morselli E, et al. Stimulation of autophagy by the p53 target gene Sestrin2. Cell Cycle, 2009, 8(10): 1571-1576. DOI:10.4161/cc.8.10.8498 |

| [35] |

Budanov A V. Stress-responsive sestrins link p53 with redox regulation and mammalian target of rapamycin signaling. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 2011, 15(6): 1679-1690. |

| [36] |

Weber J D, Taylor L J, Roussel M F, et al. Nucleolar Arf sequesters Mdm2 and activates p53. Nature Cell Biology, 1999, 1(1): 20-26. DOI:10.1038/8991 |

| [37] |

Ryan K M. p53 and autophagy in cancer: guardian of the genome meets guardian of the proteome. European Journal of Cancer, 2011, 47(1): 44-50. DOI:10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.020 |

| [38] |

Tasdemir E, Maiuri M C, Galluzzi L, et al. Regulation of autophagy by cytoplasmic p53. Nature Cell Biology, 2008, 10(6): 676-687. DOI:10.1038/ncb1730 |

| [39] |

王宠, 张萍, 朱卫国. 细胞自噬与肿瘤发生的关系. 中国生物化学与分子生物学报, 2010, 11: 988-997. Wang C, Zhang P, Zhu W G. Relationship between autophagy and tumorigenesis. Chinese Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 2010, 11: 988-997. |

| [40] |

Carafoli E. Intracellular calcium homeostasis. Annual Review of Biochemistry, 1987, 56(1): 395-433. DOI:10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.002143 |

| [41] |

Sukumaran P, Sun Y, Vyas M, et al. TRPC1-mediated Ca2+ entry is essential for the regulation of hypoxia and nutrient depletion-dependent autophagy. Cell Death & Disease, 2015, 6(3): e1674. |

| [42] |

Jiang L B, Cao L, Yin X F, et al. Activation of autophagy via Ca2+-dependent AMPK/mTOR pathway in rat notochordal cells is a cellular adaptation under hyperosmotic stress. Cell Cycle, 2015, 14(6): 867-879. DOI:10.1080/15384101.2015.1004946 |

| [43] |

Jin Y, Bai Y, Ni H, et al. Activation of autophagy through calcium‐dependent AMPK/mTOR and PKCθ pathway causes activation of rat hepatic stellate cells under hypoxic stress. FEBS Letters, 2016, 590(5): 672-682. DOI:10.1002/1873-3468.12090 |

| [44] |

Krishan S, Richardson D R, Sahni S. Amp kinase (prkaa1). Journal of Clinical Pathology, 2014, 67(9): 758-763. DOI:10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202422 |

| [45] |

Krishan S, Richardson D R, Sahni S. Adenosine monophosphate-activated kinase and Its key role in catabolism: structure, regulation, biological activity, and pharmacological activation. Molecular Pharmacology, 2015, 87(3): 363-377. DOI:10.1124/mol.114.095810 |

| [46] |

Medina D L, Ballabio A. Lysosomal calcium regulates autophagy. Autophagy, 2015, 11(6): 970-971. DOI:10.1080/15548627.2015.1047130 |

| [47] |

Medina D L, Di Paola S, Peluso I, et al. Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB. Nature Cell Biology, 2015, 17(3): 288-299. DOI:10.1038/ncb3114 |

| [48] |

Schreiber R, Landau D. Potassium in Health and Disease. Springer: Encyclopedia of Metalloproteins, 2013, 1804-1807.

|

| [49] |

Perez-Neut M, Haar L, Rao V, et al. Activation of hERG3 channel stimulates autophagy and promotes cellular senescence in melanoma. Oncotarget, 2016, 7(16): 21991-22004. DOI:10.18632/oncotarget.v7i16 |

| [50] |

Canu N, Tufi R, Serafino A L, et al. Role of the autophagic‐lysosomal system on low potassium‐induced apoptosis in cultured cerebellar granule cells. Journal of Neurochemistry, 2005, 92(5): 1228-1242. DOI:10.1111/jnc.2005.92.issue-5 |

| [51] |

Kaasik A, Rikk T, Piirsoo A, et al. Up‐regulation of lysosomal cathepsin L and autophagy during neuronal death induced by reduced serum and potassium. European Journal of Neuroscience, 2005, 22(5): 1023-1031. DOI:10.1111/ejn.2005.22.issue-5 |

| [52] |

Richardson D R, Ponka P. The molecular mechanisms of the metabolism and transport of iron in normal and neoplastic cells. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Biomembranes, 1997, 1331(1): 1-40. DOI:10.1016/S0304-4157(96)00014-7 |

| [53] |

Stohs S J, Bagchi D. Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 1995, 18(2): 321-336. |

| [54] |

Kurz T, Brunk U T. Autophagy of HSP70 and chelation of lysosomal iron in a non-redox-active form. Autophagy, 2009, 5(1): 93-95. DOI:10.4161/auto.5.1.7248 |

| [55] |

朱京, 谭晓荣. 活性氧与自噬的研究进展. 生命科学, 2011, 23(10): 987-992. Zhu j, Tang X R. Research advances in ROS and autophagy. Chinese Bulletin of Life Sciences, 2011, 23(10): 987-992. |

| [56] |

Kurz T, Eaton J W, Brunk U T. The role of lysosomes in iron metabolism and recycling. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology, 2011, 43(12): 1686-1697. |

| [57] |

Gao M, Monian P, Pan Q, et al. Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell Research, 2016, 26(9): 1021-1032. DOI:10.1038/cr.2016.95 |

| [58] |

Festa R A, Thiele D J. Copper: an essential metal in biology. Current Biology: CB, 2011, 21(21): R877-R883. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2011.09.040 |

| [59] |

Denoyer D, Masaldan S, La Fontaine S, et al. Targeting copper in cancer therapy: 'Copper That Cancer'. Metallomics: Integrated Biometal Science, 2015, 7(11): 1459-1476. DOI:10.1039/C5MT00149H |

| [60] |

Kiffin R, Bandyopadhyay U, Cuervo A M. Oxidative stress and autophagy. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling, 2006, 8(1-2): 152-162. |

| [61] |

Gutierrez E, Richardson D R, Jansson P J. The anticancer agent Di-2-pyridylketone 4, 4-dimethyl-3-thiosemicarbazone (Dp44mT) overcomes prosurvival autophagy by two mechanisms persistent induction of autophagosome synthesis and impairment of lysosomal integrity. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2014, 289(48): 33568-33589. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M114.599480 |

| [62] |

Zhong W, Zhu H, Sheng F, et al. Activation of the MAPK11/12/13/14(p38 MAPK) pathway regulates the transcription of autophagy genes in response to oxidative stress induced by a novel copper complex in HeLa cells. Autophagy, 2014, 10(7): 1285-1300. DOI:10.4161/auto.28789 |

| [63] |

Hancock C N, Stockwin L H, Han B, et al. A copper chelate of thiosemicarbazone NSC 689534 induces oxidative/ER stress and inhibits tumor growth in vitro and in vivo. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2011, 50(1): 110-121. DOI:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.10.696 |

| [64] |

Yang Y, Li C, Fu Y, et al. Redox cycling of a copper complex with benzaldehyde nitrogen mustard-2-pyridine carboxylic acid hydrazone contributes to its enhanced antitumor activity, but no change in the mechanism of action occurs after chelation. Oncology Reports, 2016, 35(3): 1636-1644. |

| [65] |

Trejo-Solís C, Jimenez-Farfan D, Rodriguez-Enriquez S, et al. Copper compound induces autophagy and apoptosis of glioma cells by reactive oxygen species and JNK activation. BMC Cancer, 2012, 12(1): 156. DOI:10.1186/1471-2407-12-156 |

| [66] |

Hung H H, Huang W P, Pan C Y. Dopamine-and zinc-induced autophagosome formation facilitates PC12 cell survival. Cell Biology and Toxicology, 2013, 29(6): 415-429. DOI:10.1007/s10565-013-9261-2 |

| [67] |

Miyazaki T, Takenaka T, Inoue T, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced overproduction of nitric oxide and overexpression of iNOS and interleukin-1β proteins in zinc-deficient rats. Biological Trace Element Research, 2012, 145(3): 375-381. DOI:10.1007/s12011-011-9197-4 |

| [68] |

Summersgill H, England H, Lopez-Castejon G, et al. Zinc depletion regulates the processing and secretion of IL-1β. Cell Death & Disease, 2014, 5(1): e1040. |

| [69] |

Cartharius K, Frech K, Grote K, et al. MatInspector and beyond: promoter analysis based on transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics, 2005, 21(13): 2933-2942. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti473 |

| [70] |

Li Y, Zhang L, Li K, et al. ZNF32 inhibits autophagy through the mTOR pathway and protects MCF-7 cells from stimulus-induced cell death. Scientific Reports, 2015, 5: 9288. DOI:10.1038/srep09288 |

| [71] |

Gorojod R M, Alaimo A, Porte Alcon S, et al. The autophagic-lysosomal pathway determines the fate of glial cells under manganese-induced oxidative stress conditions. Free Radical Biology & Medicine, 2015, 87: 237-251. |

| [72] |

Zhang J, Cao R, Cai T, et al. The role of autophagy dysregulation in manganese-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Neurotoxicity Research, 2013, 24(4): 478-490. DOI:10.1007/s12640-013-9392-5 |

| [73] |

Yuan Z, Ying X P, Zhong W J, et al. Autophagy attenuates MnCl2-induced apoptosis in human bronchial epithelial cells. Biomedical and Environmental Sciences: BES, 2016, 29(7): 494-504. |

| [74] |

Liu J, Guo W, Li J, et al. Tumor-targeting novel manganese complex induces ROS-mediated apoptotic and autophagic cancer cell death. International Journal of Molecular Medicine, 2015, 35(3): 607-616. |

| [75] |

Ogata A, Yanagie H, Ishikawa E, et al. Antitumour effect of polyoxomolybdates: induction of apoptotic cell death and autophagy in in vitro and in vivo models. British Journal of Cancer, 2008, 98(2): 399-409. DOI:10.1038/sj.bjc.6604133 |

| [76] |

Yang L, Tan P, Zhou W, et al. N-acetylcysteine protects against hypoxia mimetic-induced autophagy by targeting the HIF-1α pathway in retinal ganglion cells. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, 2012, 32(8): 1275-1285. DOI:10.1007/s10571-012-9852-0 |

| [77] |

Thonqchot S, Yongvanit P, Loilome W, et al. High expression of HIF-1α, BNIP3 and PI3KC3: hypoxia-induced autophagy predicts cholangiocarcinoma survival and metastasis. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention Apjcp, 2014, 15(15): 5873-5878. |

| [78] |

Hu Y L, DeLay M, Jahangiri A, et al. Hypoxia-induced autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and adaptation to antiangiogenic treatment in glioblastoma. Cancer Research, 2012, 72(7): 1773-1783. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3831 |

| [79] |

Naves T, Jawhari S, Jauberteau M O, et al. Autophagy takes place in mutated p53 neuroblastoma cells in response to hypoxia mimetic CoCl(2). Biochemical Pharmacology, 2013, 85(8): 1153-1161. DOI:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.01.022 |

| [80] |

史美琳, 周阳, 刘海涛, 等. 镉诱导细胞自噬的分子机制研究进展. 生物学杂志, 2016, 33(5): 79-82. Shi M L, Zhou Y, Liu H T, et al. Advance in molecular mechanism of autophagy induced by cadmium. Journal of Biology, 2016, 33(5): 79-82. |

| [81] |

Wang Q W, Wang Y, Wang T, et al. Cadmium induced autophagy promotes survival of rat cerebral cortical neurons by activating class Ⅲ phosphoinositide 3-kinase/beclin-1/B-cell lymphoma 2 signaling pathways. Molecular Medicine Reports, 2015, 12(2): 2912-2918. |

| [82] |

Wang Q W, Wang Y, Wang T, et al. Cadmium-induced autophagy is mediated by oxidative signaling in PC-12 cells and is associated with cytoprotection. Molecular Medicine Reports, 2015, 12(3): 4448-4454. |

| [83] |

Sui L, Zhang R H, Zhang P, et al. Lead toxicity induces autophagy to protect against cell death through mTORC1 pathway in cardiofibroblasts. Bioscience Reports, 2015, 35(2): e00186. |

| [84] |

Kerr R P, Krunkosky T M, Hurley D J, et al. Lead at 2.5 and 5.0μmol/L induced aberrant MH-Ⅱ surface expression through increased MⅡ exocytosis and increased autophagosome formation in Raw 267.4 cells. Toxicology in Vitro, 2013, 27(3): 1018-1024. DOI:10.1016/j.tiv.2013.01.018 |

| [85] |

Lv X H, Zhao D H, Cai S Z, et al. Autophagy plays a protective role in cell death of osteoblasts exposure to lead chloride. Toxicology Letters, 2015, 239(2): 131-140. DOI:10.1016/j.toxlet.2015.09.014 |

| [86] |

Bolt A M, Zhao F, Pacheco S, et al. Arsenite-induced autophagy is associated with proteotoxicity in human lymphoblastoid cells. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2012, 264(2): 255-261. DOI:10.1016/j.taap.2012.08.006 |

| [87] |

Cheng J, Wei H L, Chen J, et al. Antitumor effect of arsenic trioxide in human K562 and K562/ADM cells by autophagy. Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods, 2012, 22(7): 512-519. DOI:10.3109/15376516.2012.686534 |

| [88] |

Kanzawa T, Kondo Y, Ito H, et al. Induction of autophagic cell death in malignant glioma cells by arsenic trioxide. Cancer Research, 2003, 63(9): 2103-2108. |

| [89] |

BonakdarYazdi B, Khodagholi F, Shaerzadeh F, et al. The effect of arsenite on spatial learning: Involvement of autophagy and apoptosis. European Journal of Pharmacology, 2017, 796: 54-61. DOI:10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.12.023 |

| [90] |

Thévenod F, Lee W K. Cadmium and cellular signaling cascades: interactions between cell death and survival pathways. Archives of Toxicology, 2013, 87(10): 1743-1786. DOI:10.1007/s00204-013-1110-9 |

| [91] |

Son Y O, Wang X, Hitron J A, et al. Cadmium induces autophagy through ROS-dependent activation of the LKB1-AMPK signaling in skin epidermal cells. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2011, 255(3): 287-296. DOI:10.1016/j.taap.2011.06.024 |

| [92] |

Wei Y, Pattingre S, Sinha S, et al. JNK1-mediated phosphorylation of Bcl-2 regulates starvation-induced autophagy. Molecular Cell, 2008, 30(6): 678-688. DOI:10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.001 |

| [93] |

Alexander A, Kim J, Walker C L. ATM engages the TSC2/mTORC1 signaling node to regulate autophagy. Autophagy, 2010, 6(5): 672-673. DOI:10.4161/auto.6.5.12509 |

| [94] |

Messner B, Türkcan A, Ploner C, et al. Cadmium overkill: autophagy, apoptosis and necrosis signalling in endothelial cells exposed to cadmium. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 2016, 73(8): 1699-1713. DOI:10.1007/s00018-015-2094-9 |

| [95] |

Misra U K, Gawdi G, Pizzo S V. Induction of mitogenic signalling in the 1LN prostate cell line on exposure to submicromolar concentrations of cadmium+. Cellular Signalling, 2003, 15(11): 1059-1070. DOI:10.1016/S0898-6568(03)00117-7 |

| [96] |

Woods A, Dickerson K, Heath R, et al. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase kinase-β acts upstream of AMP-activated protein kinase in mammalian cells. Cell Metabolism, 2005, 2(1): 21-33. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.005 |

| [97] |

Luo B, Lin Y, Jiang S, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress eIF2α-ATF4 pathway-mediated cyclooxygenase-2 induction regulates cadmium-induced autophagy in kidney. Cell Death & Disease, 2016, 7(6): e2251. |

2017, Vol. 37

2017, Vol. 37