文章信息

- 安龙飞, 金龙, 孙凤亮, 李凯, 闫成智, 秦钧, 张普民, 吴琛, 陈欢.

- AN Long-fei, JIN Long, SUN Feng-liang, LI Kai, YAN Cheng-zhi, QIN Jun, ZHANG Pu-min, WU Chen, CHEN Huan.

- 应用蛋白质组学筛选宫颈癌患者尿液中的肿瘤标志物

- The character of cervical cancer patients and healthy women in experiment group and validation group

- 中国生物工程杂志, 2016, 36(9): 1-10

- China Biotechnology, 2016, 36(9): 1-10

- http://dx.doi.org/DOI:10.13523/j.cb.20160901

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2016-02-15

2. 陕西省人民医院肿瘤放射治疗科 西安 710068;

3. 北京蛋白质组研究中心 北京 102200;

4. 天津医科大学宝坻临床学院泌尿外科 天津 301800

2. Department of Oncology Radiotherapy, Shanxi Province People's Hospital, Xi'an 710068, China;

3. Beijing Proteome Research Center, Beijing 102200, China;

4. Department of Urology Surgery, Baodi Clinical Hospital, Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin 301800, China

宫颈癌的发病率在世界范围内占女性肿瘤第四位,每年有53万左右的女性诊断为宫颈癌,并且在发展中国家的发病率高于发达国家[1],但是宫颈癌患者的年轻化是发展中国家和发达国家共同面对的一个问题。80%~90%的宫颈癌患者是因为感染了高危的人乳头瘤病毒(hr-HPV)[2-3]。在乳头瘤病毒中有35个被认定是高危的,有40个被认定为是低风险的[3-4],其中HPV16和HPV18是高危乳头瘤病毒中最常见的两种[3]。乳头瘤病毒中的癌基因E6和E7,在宫颈癌的发生、发展过程中起着重要作用,可能是因为E6和E7可以抑制p53和pRb从而引发宫颈癌[5]。宫颈癌患者的生存率与肿瘤所处的等级呈负相关,等级越高,患者五年的生存率越低[6]。所以早诊宫颈癌是提高患者生存率关键的因素。在宫颈癌患者的血浆中可以检测到HPV的DNA,并且HPV DVA可以作为宫颈癌的特异标志物,因此检测HPV DNA可以作为对宫颈癌的初筛方法,但是这种方法只适用于感染了hr-HPV的女性,并且这种方法的敏感度低[7],难以做到早诊宫颈癌的要求,因此急需寻找到对宫颈癌特异性强、敏感性高且无创性的肿瘤标志物。蛋白质组学的发展为研究疾病机制和寻找新的肿瘤标志物提供了新的思路。

蛋白质组学一开始只能用来分析生物样本中的蛋白质组成,基于质谱技术的蛋白质组学发展迅速,特别是随着定量蛋白质组学的发展,使得人们可以观察细胞、生物体内蛋白质的动态变化,研究生命科学,拓展了蛋白质组学的应用领域[8-10]。越来越多的研究人员应用蛋白质组研究疾病机制和发现疾病新的生物标志物[11]。尿液,是血液经过肾脏时产生的透析液,血液保留了绝大部分的蛋白质,反映机体变化的一些蛋白质因为血液的稳态环境或高丰度蛋白质的影响检测不到变化,但是可以在尿液中能检测到[12-13],并且尿液与血液直接关联,具有无创性、取样简单等优点,是理想的研究材料和生物标志物的源泉。

在这个研究中我们收集了43例宫颈癌患者和47例健康人的尿液样本,用质谱鉴定尿液中的蛋白质,比较宫颈癌和健康对照的尿蛋白质组,分析差异蛋白,筛选潜在的肿瘤标志物。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材 料患者尿液样本均来自西安交通大学第一附属医院。患者临床病理分型结果见表 1。健康对照纳入标准:无妇科疾病及泌尿系统疾病的健康女性。实验组:宫颈癌患者13名,女性,年龄28~72,平均年龄(52±11)岁;7名健康人,女性,年龄26~80,平均年龄(54±11)岁。验证组:30名宫颈癌患者,女性,年龄26~72,平均年龄(53±10);40名健康人,女性,年龄26~75,平均年龄(51±10)。受试者均被告知收取尿液的用途并签署知情同意书。

| Experiment group | Validation group | ||||

| Patients(n=13) | Healthy women(n=7) | Patients(n=30) | Healthy women(n=40) | ||

| Age(Mean±SD) | 52±11 | 54±11 | 53±10 | 51±10 | |

| FIGO stage(n) | 13 | 0 | 30 | 0 | |

| CIN Ⅱ-Ⅲ | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| CIN Ⅲ | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| IA2-IB1 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 0 | |

| IB2-ⅡB | 6 | 0 | 11 | 0 | |

| ⅡB-ⅢB | 2 | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

1.2 方 法 1.2.1 样本收集

分别收取宫颈癌患者和健康志愿者中段晨尿,存于干净的离心管(50ml)中,-80℃冰箱储存备用。

1.2.2 超速离心沉淀尿蛋白常温融化尿液样本,震荡后静置,取上清液,样本之间不合并,每个样本作为独立的实验对象。200 000g、常温离心70min。弃上清液,沉淀用重悬液重悬,再加入0.5mol/L DTT,56℃水浴30min。之后加入洗液,混匀,186 000g、常温离心45min,沉淀用8mol/L尿素溶解。Bradford法测蛋白质浓度。

1.2.3 SDS-PAGE电泳及胶内酶解每例样本各取20μg蛋白,分别用10% SDS-PAGE电泳分离蛋白质,电泳后考马斯亮蓝染色,脱色。每例样本对应的条带由上往下均匀切成4部分,分别胶内酶解、肽段提取得到可以进行质谱分析的4份肽段样品。每例样品得到的4份肽段样品合并为2个组分进行干燥。

2 质谱鉴定、搜库每例样本的2个组分,分别溶于30μl溶液A(水∶甲酸=99.8∶0.2)中,12 000r/min、离心10min,取上清液进行质谱鉴定(每例样本之间不合并),每组分上样量为500ng。用B液(乙腈∶甲酸=99.8∶0.2)的流动相以350nl/min流速开始洗脱,并且5min内B液梯度线性升至5%,50min时升至10%,55min时升至15%,65min升至35%,66min升至95%并持续到75min。质谱条件纳升级电喷雾电离方式,正离子模式扫描,离子源电压2kV,离子入口毛细血管温度250℃,扫描范围 m/z300~1400,动态排除时间为75s。

搜索引擎:MASCOT;搜索软件:Proteome Discover (1.4版本,Thermo Scientific);数据库:NCBI_human Ref-sequence protein database。一级离子的偏差设为20ppm、二级离子偏差为50mmu。PSM(peptide-spectrum match)的假阳性率(FDR)小于1%的严格卡值。

3 生物信息学分析和数据分析应用IBAQ(intensity based absolute quantification)对鉴定到的蛋白质做无标定量。蛋白质相对丰度值用FOT(fraction of total)的方法做归一化处理。

|

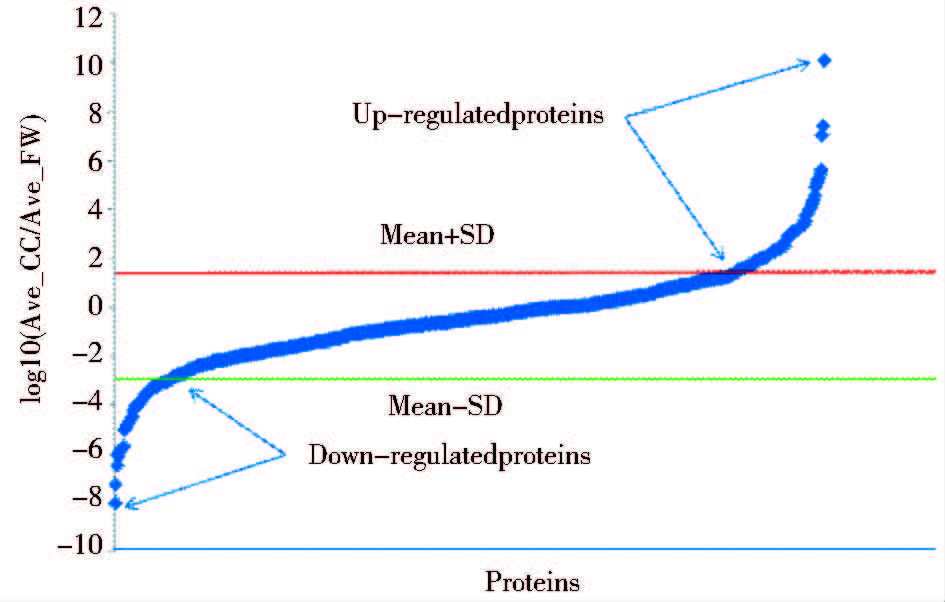

差异蛋白分析是对蛋白质在肿瘤组和健康组的平均值的比值(Ave_CC/Ave_HW)取对数,以此建模,计算平均值±标准差(mean±SD),上调蛋白定义为其log10(Ave_CC/Ave_CC)大于Mean+SD,下调蛋白定义为小于Mean-SD。对差异蛋白的GO分析是在DAVID Bioinformatics Resources(网址:http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov)上完成的[14]。当student t-检验P<0.05时,认为差异有统计学意义。数据分析、作图和聚类分析使用SPSS软件和Cluster3.0软件。

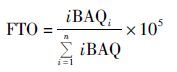

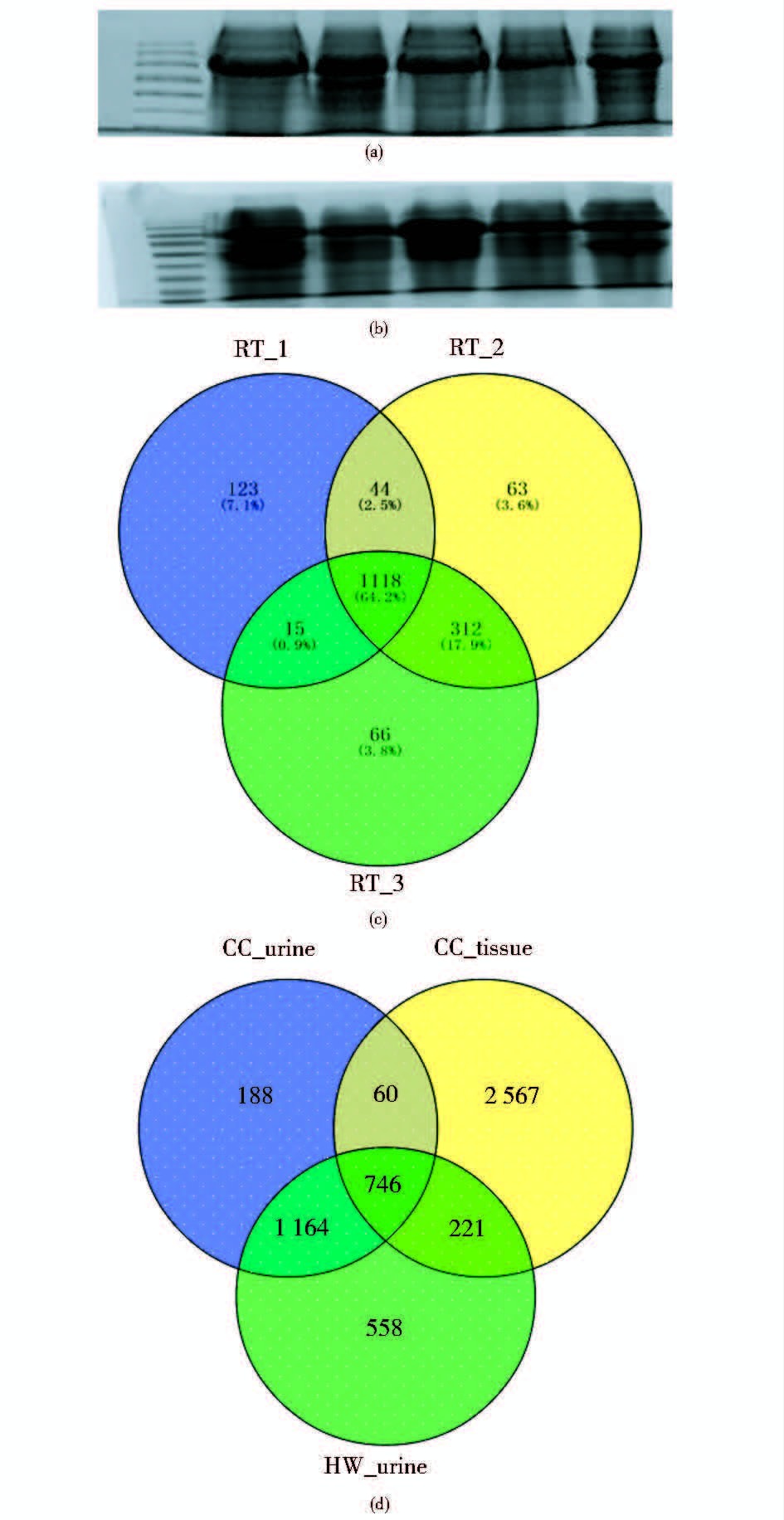

4 结 果 4.1 实验重复性及尿蛋白质组20μg蛋白质用10%SDS-PAGE电泳分离后,考马斯亮兰染色,脱色后,拍照,见图 1(a)、(b)。我们对一个健康女性连续取三次晨尿,鉴定尿蛋白,在这三次重复试验(repeated test,RT)中,有64.2%的蛋白质能在这三次重复试验中被鉴定到[图 1(c)]。根据Papachristou等[15]的研究,在宫颈癌患者组织(CC_tissue)中共鉴定到3 594个蛋白质。在本研究中,在实验组的宫颈癌患者尿液(CC_urine)中鉴定到4 135个蛋白质(FDRR<0.01),其中unique peptides>1的蛋白质有2 158个。在健康女性的尿液(HW_urine)中鉴定到4 347个蛋白质(FDR<0.01),其中unique peptides>1的蛋白质有2 689个[图 1(d)]。宫颈癌患者的尿蛋白和组织蛋白有806个重合蛋白,可能是组织的分泌蛋白在尿液中得到富集;健康女性的尿蛋白和宫颈癌组织蛋白也有967个重合蛋白;宫颈癌和健康女性尿蛋白有1 910个重合蛋白,其中746个蛋白质共同属于宫颈癌尿液、健康女性尿液和宫颈癌组织。

|

| 图 1 尿蛋白SDS-PAGE电泳胶图、实验重复性及尿蛋白质文氏图 Figure 1 The result of urine proteins separated by SDS-PAGE,repeated tests (RT) and venn diagram of three groups of urine proteins (a) Healthy women (b) Cervical cancer patients (c) Three repeated tests (d) Venn diagram shows the overlap between identified proteins in CC_urine(cervical cancer patients' urine),CC_tissue(cervical cancer tissue) and HW_urine(healthy women' urine) |

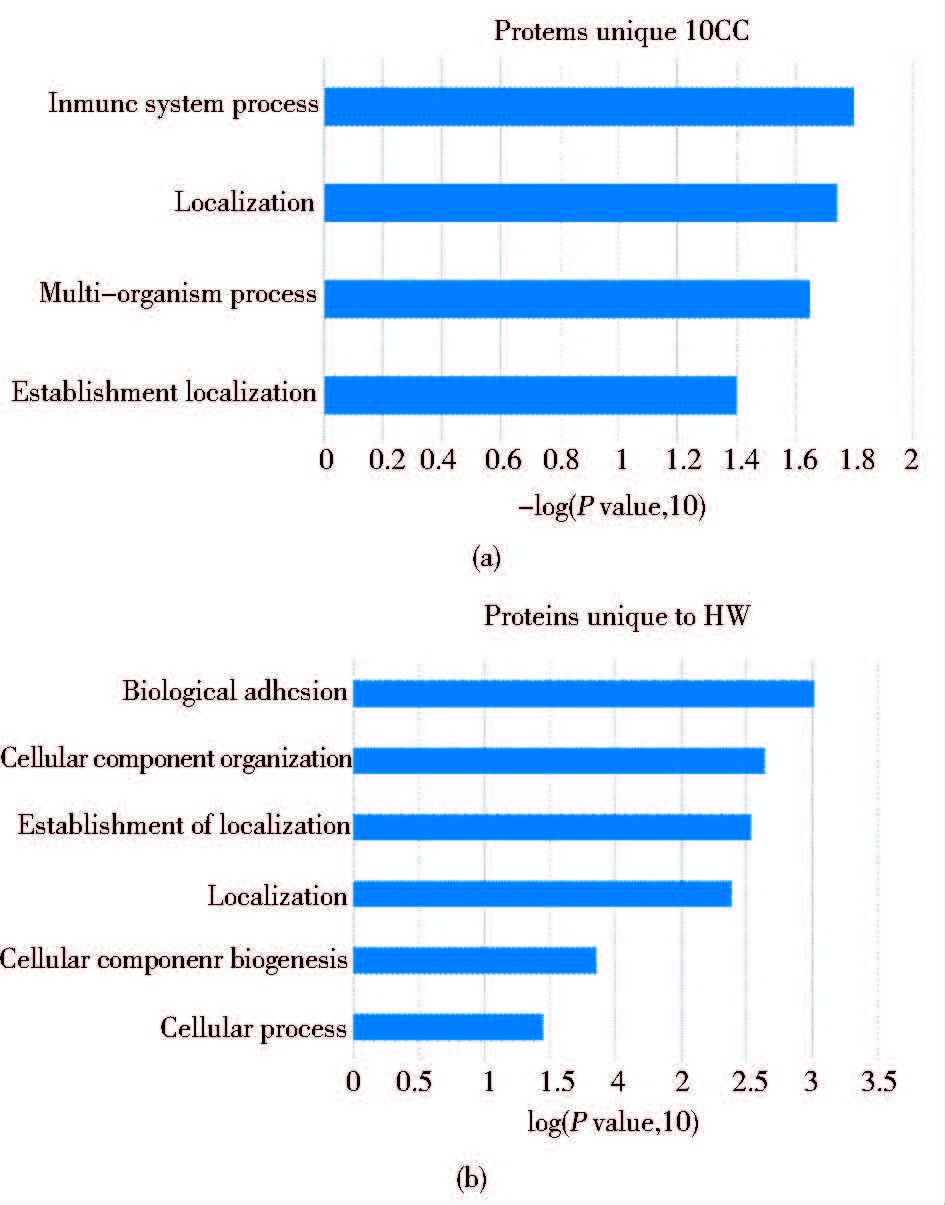

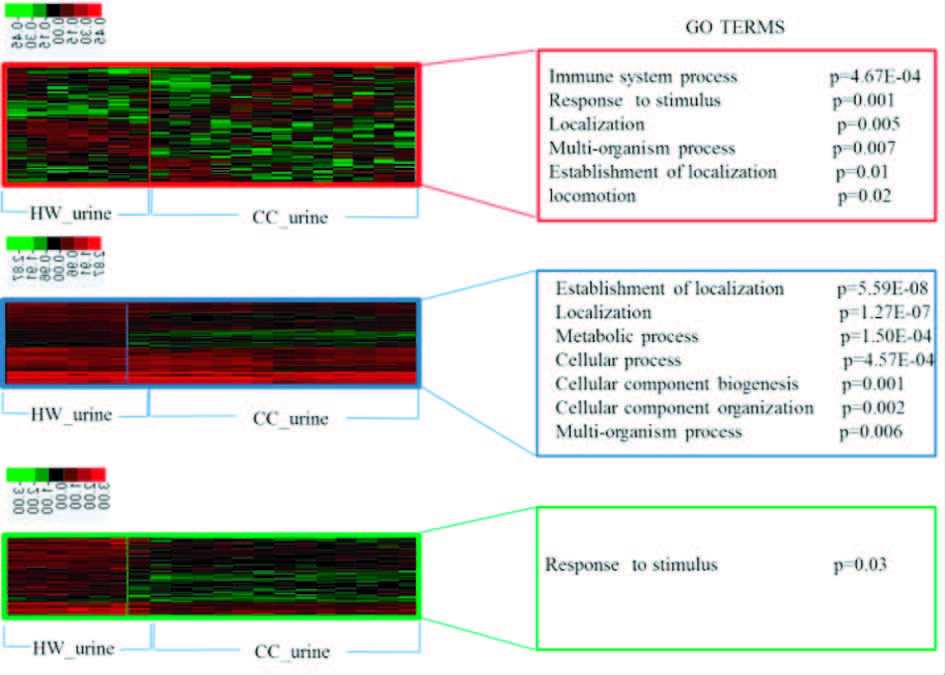

与健康女性相比,有248个蛋白质只存在于宫颈癌患者尿液中[图 1(d)],对这部分蛋白质做GO分析,生物过程富集程度最高的是免疫系统过程[图 2(a)]。只在健康女性的尿液中存在的蛋白质有558个,同样对这部分蛋白质做GO分析,富集程度最高的是生物粘连[图 2(b)]。只在宫颈癌患者尿液中出现的248个蛋白质中,S100A7和CEACAM8在13例样本中出现的频率分别为11/13和6/13,敏感性分别为84%和46%。如果将这两个蛋白质作为一个整体联合诊断宫颈癌,敏感性可提高到92%。

|

| 图 2 宫颈癌患者尿液特异表达蛋白(a)和健康女性(b)GO_BP分析条形图(P<0.05) Figure 2 GO_BP analysis of proteins unique to CC (a)and HW (b) in urine(P<0.05) |

在宫颈癌患者尿蛋白、宫颈癌组织蛋白和健康人尿蛋白中共有746个重合蛋白[图 1(d)],在这部分蛋白质中,宫颈癌患者尿蛋白与健康女性尿蛋白相比,我们鉴定到84个上调的蛋白质、82个下调的蛋白质及580个变化不明显的蛋白质(图 3)。分别对这三部分蛋白质做聚类分析和GO生物功能富集分析,聚类结果显示,只有上调蛋白能将宫颈癌和健康女性完全分开。因此,在746个重合蛋白中我们只对上调蛋白做进一步的筛选,挑选出候选标志物。GO分析结果发现,上调蛋白的生物过程富集程度最高的是免疫功能(immune system process),下调蛋白只有在应激反应过程(response to stimulus)有明显的富集现象(图 4)。上调蛋白中,DPP4在宫颈癌患者尿液中出现的频率为100%(13/13),并且相对丰度上调了3倍。

|

| 图 3 宫颈癌和健康女性共有尿蛋白相对丰度比值的散点图 Figure 3 Scatter diagram shows that relative abundance ratios of proteins found in CC and HW urine samples Mean+SD: Mean+Standard deviation;Mean-SD:Mean-Standard deviation |

|

| 图 4 上调蛋白、下调蛋白和变化不明显的蛋白质聚类分析结果及GO_BP富集分析结果 Figure 4 The cluster analysis and GO_BP enrichment analysis of up-regulated proteins,down-regulated proteins and non-significantly regulated proteins |

S100A7、CEACAM8和DPP4能否作为诊断宫颈癌的标志物,我们又作了进一步的验证。

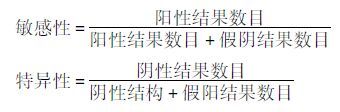

4.3 质谱法验证标志物在验证组中,我们又征集了30例宫颈癌患者和40例健康女性尿液样本。采用与实验组相同的方法处理尿液样本,用得到的质谱数据验证标志物。对S100A7和CEACAM8的验证,我们采取了双盲法。敏感性和特异性按照下述的公式计算。

|

在总共70个测试样本中(total test),在25例样本中检测到S100A7,其中有3例来自健康女性(false positive),22例来自宫颈癌患者(true positive);在31例样本中检测到CEACAM8,其中有5例来自健康女性(false positive),26例来自宫颈癌患者(true positive) [图 5(a)]。通过这种方法我们得到了S100A7、CEACAM8及两者联合诊断宫颈癌的敏感性为73%、87%和93%,并且特异性为93%、88%、85% (表 2)。这两个蛋白质在健康女性中被检测到的次数明显小于在宫颈癌患者中被检测到的次数[图 5(b)],并且这两个蛋白在宫颈癌患者尿液样本中的相对丰度明显高于健康女性[图 5(c)、(d)]。在30例宫颈癌患者尿液中都能检测到DPP4,与健康对照相比上调了3倍。对DPP4在宫颈癌和健康女性尿液中相对丰度做t检验,箱式图显示上调明显[图 5(e)]。随后我们对DPP4做ROC分析,评价其诊断价值。DPP4的线下面积(area under the curve,AUC)为0.725(95%CI:0.593~0.875),敏感性67%,特异性76%[图 5(f)]。

|

| 图 5 S100A7、CEACAM8和DPP4作为候选肿瘤标志物的验证结果 Figure 5 The validation results of three candidate markers S100A7,CEACAM8 and DPP4 (a)The stacked bar chart shows the frequency of S100A7,CEACAM8,combined S100A7 and CEACAM8 (S100A7+CEACAM8) to detect CC in validation group by double-blind test (b)The Bar chart shows the frequency of S100A7,CEACAM8 and S100A7+CEACAM8 in HW and CC urine samples. The Box plot shows that the relative abundance of S100A7(c),CEACAM8(d) and DPP4 (e) in CC_urine and in HW_urine (f)Receiver operating characteristic curve(ROC) analysis of DPP4 in diagnosis of cervical cancer *:P<0.05,***: P<0.001;HW_urine: Healthy women' urine;CC_urine: Cervical cancer patients’ urine |

| Validation group | |||

| S100A7 | CEACAM8 | S100A7+CEACAM8 | |

| Total tests(n) | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| False positives(n) | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| True positives(n) | 22 | 26 | 28 |

| False negatives(n) | 8 | 4 | 2 |

| True negatives(n) | 37 | 35 | 34 |

| Sensitivity | 73 | 87 | 93 |

| Specificity | 93 | 88 | 85 |

5 讨 论

宫颈癌是女性中第三个最常见的恶性肿瘤,并且在引起女性死亡的原因中排名第四[16]。多数宫颈癌患者是因为感染了hr-HPV人们不仅能在宫颈癌患者血液中检测到HPV DNA。而且还可以用蛋白质组学的方法研究感染HPV病毒后引起的蛋白质组的变化[15, 17-18]。不仅如此,蛋白质组还可以用来寻找用于诊断宫颈癌的肿瘤标志物[16-21]。我们的研究就是用蛋白质组的方法研究宫颈癌患者尿液中的差异蛋白,并筛选潜在的肿瘤标志物。除此之外我们还借助于已有研究中的宫颈癌组织蛋白质组数据,与尿蛋白质组数据作比较后发现对三者共有的746个蛋白质[图 1(d)]做聚类分析后能将宫颈癌患者和健康人完全分开(图 4),但是在去除宫颈癌组织蛋白质组数据后,宫颈癌患者和健康女性共有的尿蛋白不能完全分开。

GO分析结果显示,在宫颈癌患者尿液中独有的蛋白质多参与免疫系统。在其他的研究中,女性在感染HPV后,会激活免疫系统[22];而在健康女性尿液中独有的蛋白质多参与生物粘连,而生物粘连是细胞之间重要的“沟通”方式,也是介导细胞免疫的重要机制[23],并且细胞间的接触也可以抑制细胞的过度增殖[24],防止肿瘤发生。

在实验组中我们筛选到三个候选的肿瘤标志物——DPP4、S100A7、CEACAM8。在验证组中,S100A7和CEACAM8及两者联合诊断宫颈癌均得到了较好的结果,具有潜在的诊断价值。

DPP4,也称为CD26,是一个多功能的分子,在多种类型细胞的表面均有表达,可能作为一些癌细胞或恶性间皮瘤和直肠癌干细胞的细胞表面标志物[25-28]。在最近的研究中发现,DPP4还与肿瘤的生长、侵袭和转移有关[29],可能是因为DPP4能与细胞外基质的主要成分纤连蛋白和胶原蛋白相互作用[30-32]。Kacar等[33]发现,在皮肤鳞状上皮癌的癌与癌旁相比,DPP4的表达量明显下调。而在我们的结果中,DPP4在宫颈癌患者的尿液中明显上调。这也是第一次发现DPP4在宫颈癌尿液中上调。

S100A7通常也称为牛皮癣素,是S100基因家族的一员,而S100的基因产物是一系列带有EF-hand结构域的钙粘连蛋白[34-37]。首次发现S100A7是从一个牛皮癣患者的皮肤中分离得到[34],还有研究发现其在皮肤疾病中也高表达[38]。除此之外,S100A7不仅能在细胞核和细胞质中检测到并且还能作为分泌蛋白[39-40]。S100A7的表达在正常人乳腺细胞MCF10A中丰度非常低[40],但是在皮肤癌、膀胱癌和乳腺癌中表达升高[41-44]。Dey等[45]发现,过表达S100A7可以增加口腔鳞状细胞癌癌细胞的致瘤性,抑制癌细胞凋亡。Krop等[46]在乳腺癌细胞MDA-MB-468中敲低S100A7后发现,在体外实验中没有影响癌细胞的增殖但是增加了癌细胞的侵袭转移,在体内试验中抑制了肿瘤的增长。S100A7可以影响癌细胞的增殖、转移及侵袭,提示其有可能作为诊断肿瘤的标志物或药物靶标。用RNA-sequence技术分析宫颈上皮内瘤样病变I~Ⅲ患者组织样本中的RNA,S100A7在这些样本中高表达,提示其可以作为肿瘤标志物用来早诊宫颈癌[47]。实验组中,S100A7只存在于宫颈癌患者的尿液样本中,特异性为100%,敏感性为84%(11/13),在验证组中双盲法测试其敏感性为73%,特异性能达到93%(表 2)。

CEACAM8也被称为CD66b,位于细胞表面,是一种磷酸肌醇化糖蛋白,同样也是人胚胎抗原(human carcinoembryonic Ag,CEA)家族的一员[48-49]。CEA家族的成员在上皮细胞、内皮细胞和造血细胞中有表达,如中性粒细胞、T细胞和NK细胞。同时,这些蛋白质位于细胞表面可以传递信号引起多种生物效应,如抑制或促进肿瘤的发生、血管形成、激活粒细胞和淋巴细胞、调控细胞周期等[50]。CD66b就是能激活粒细胞的一种激活因子[51-52],但是其中的机制还不清楚。有研究证实,在受曼氏血吸虫感染后,酸性粒细胞中CD66b的表达增加[53],CD66b可能与细胞表面其他分子联合激活酸性粒细胞[49]。在细菌刺激下,中性粒细胞中(tumor-associated neutrophil,TAN)CD66b表达升高,TAN的活性被激活[54]。不仅如此,CEACAMs还能作为标志物用于诊断癌症,应用最广泛的则是诊断结直肠癌[55]。有的研究发现其还可能作为非小细胞肺癌、乳腺癌和胃癌的标志物[56-58]。Carus等的研究发现与肿瘤有联系的TAN中呈CD66b阳性(CD66b+)的细胞数可以作为早诊宫颈癌的一个新的指标。而在我们的研究中,CD66b存在于宫颈癌患者的尿液中,可能是因为宫颈癌患者中TANs上可溶的CD66b释放到血液,最后在尿液中得到富集。在验证组中CEACAM8的敏感性和特异性能达到87%和88%(表 2)。实验组中,在健康女性尿液中未检测到S100A7和CEACAM8,是宫颈癌患者独有的尿蛋白,所以我们采用双盲法来验证这两个蛋白质是否能作为标志物。结果证实这两个蛋白质均有较高的敏感性和特异性。两者联合诊断可以明显提高敏感性(93%),但是相应的特异性降低。验证组中扩大健康女性样本后,发现40例健康女性尿样中有3例可以检测到S100A7、5例可以检测到CEACAM8[图 5(b)],特异性不再是实验组中的100%,说明任何一个蛋白质在扩大样本量后可能会出现在健康组和疾病组。虽然这两个蛋白质出现在健康女性尿样中,但是频数不高,并且对比两者在健康对照和宫颈癌样本中的相对丰度发现,后者明显高于前者[图 5(c)、(d)]。总而言之,尿液作为血液经肾过滤后的透析液,具有无创、取样简便等优点,人体体内发生任何变化都有可能引起尿液蛋白质组的变化。比较健康女性和宫颈癌患者的尿蛋白质组学,可以很好反映宫颈癌患者体内发生的改变,并且从差异蛋白中能筛选出宫颈癌的潜在肿瘤标志物。S100A7、CEACAM8、S100A7+CEACAM8具有潜在的诊断宫颈癌的价值。但是DPP4是否可以作为诊断宫颈癌的标志物还需要进一步验证。

| [1] | Manzo-Merino J, Contreras-Paredes A, Vázquez-Ulloa E, et al. The role of signaling pathways in cervical cancer and molecular therapeutic targets. Arch Med Res , 2014, 45 (7) : 525–539. DOI:10.1016/j.arcmed.2014.10.008 |

| [2] | Dasari S, Wudayagiri R, Valluru L. Cervical cancer:Biomarkers for diagnosis and treatment. Clin Chim Acta , 2015, 445 : 7–4411. DOI:10.1016/j.cca.2015.03.005 |

| [3] | Crosbie E J, Einstein M H, Franceschi S, et al. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet , 2013, 382 (9895) : 889–899. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60022-7 |

| [4] | Muñoz N, Bosch F X, de Sanjosé S, et al. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med , 2003, 348 (6) : 518–527. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa021641 |

| [5] | Narisawa-Saito M, Kiyono T. Basic mechanisms of high-risk human papillomavirus-induced carcinogenesis:roles of E6 and E7 proteins. Cancer Sci , 2007, 98 (10) : 1505–1511. DOI:10.1111/cas.2007.98.issue-10 |

| [6] | Miglierini P, Malhaire J P, Goasduff G, et al. Cervix cancer brachytherapy:High dose rate. Cancer Radiother , 2014, 18 (5-6) : 452–457. DOI:10.1016/j.canrad.2014.06.008 |

| [7] | Pornthanakasem W, Shotelersuk K, Termrungruanglert W, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA in plasma of patients with cervical cancer. BMC Cancer , 2001, 1 : 2. DOI:10.1186/1471-2407-1-2 |

| [8] | Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature , 2003, 422 (6928) : 198–207. DOI:10.1038/nature01511 |

| [9] | Bantscheff M, Kuster B. Quantitative mass spectrometry in proteomics. Anal Bioanal Chem , 2012, 404 (4) : 937–938. DOI:10.1007/s00216-012-6261-7 |

| [10] | 常乘, 朱云平. 基于质谱的定量蛋白质组学策略和方法研究进展. 中国科学:生命科学 , 2015, 45 : 425–438. Chang C, Zhu Y P. Strategies and algorithms for quantitative proteomics based on mass spectrometry. Scientia Sinica Vitae , 2015, 45 : 425–438. |

| [11] | Srivastava S, Srivastava R G. Proteomics in the forefront of cancer biomarker discovery. J Proteome Res , 2005, 4 (4) : 1098–1103. DOI:10.1021/pr050016u |

| [12] | Marimuthu A, O'Meally R N, Chaerkady R, et al. A comprehensive map of the human urinary proteome. J Proteome Res , 2011, 10 (6) : 2734–2743. DOI:10.1021/pr2003038 |

| [13] | Shao C, Wang Y, Gao Y H. Applications of urinary proteomics in biomarker discovery. Sci China Life Sci , 2011, 54 : 409–417. DOI:10.1007/s11427-011-4162-1 |

| [14] | Huangda W, Sherman B T, Lempicki R A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc , 2009, 4 (1) : 44–57. |

| [15] | Papachristou E K, Roumeliotis T I, Chrysagi A, et al. The shotgun proteomic study of the human thin prep cervical smear using iTRAQ mass-tagging and 2D LC-FT-Orbitrap-MS:the detection of the human papillomavirus at the protein level. J Proteome Res , 2013, 12 : 2078–2089. DOI:10.1021/pr301067r |

| [16] | Salomon-Perzyńska M, Perzyński A, Rembielak-Stawecka B, et al. VEGF-targeted therapy for the treatment of cervical cancer-literature review. Ginekol Pol , 2014, 85 (6) : 461–465. |

| [17] | Gu Y, Wu S L, Meyer J L, et al. Proteomic analysis of high-grade dysplastic cervical cells obtained from ThinPrep slides using laser capture microdissection and mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res , 2007, 6 (11) : 4256–4268. DOI:10.1021/pr070319j |

| [18] | Boichenko A P, Govorukhina N, Klip H G, et al. A panel of regulated proteins in serum from patients with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer. J Proteome Res , 2014, 13 (11) : 4995–5007. DOI:10.1021/pr500601w |

| [19] | Guo X, Hao Y, Kamilijiang M, et al. Potential predictive plasma biomarkers for cervical cancer by 2D-DIGE proteomics and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. Tumour Biol , 2015, 36 (3) : 1711–1720. DOI:10.1007/s13277-014-2772-5 |

| [20] | Aobchey P, Niamsup H, Siriaree S, et al. Proteomic analysis of candidate prognostic uinary marker for cervical cancer. J Proteomics , 2013, 6 (11) : 245–251. |

| [21] | Van Raemdonck G A, Tjalma W A, Coen E P, et al. Identification of protein biomarkers for cervical cancer using human cervicovaginal fluid. PLoS One , 2014, 9 (9) : e106488. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0106488 |

| [22] | Tindle R W. Immune evasion in human papillomavirus-associated cervical cancer. Nat Rev Cancer , 2002, 2 (1) : 59–65. DOI:10.1038/nrc700 |

| [23] | Multhaupt H A, Leitinger B, Gullberg D, et al. Extracellular matrix component signaling in cancer. Adv Drug Deliv , 2016, 97 : 28–40. DOI:10.1016/j.addr.2015.10.013 |

| [24] | Hanahan D, Weinberg R A. Hallmarks of cancer:the next generation. Cell , 2011, 144 (5) : 646–674. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 |

| [25] | Lam C S, Cheung A H, Wong S K, et al. Prognostic significance of CD26 in patients with colorectal cancer. PLoS One , 2014, 9 (5) : e98582. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0098582 |

| [26] | Inamoto T, Yamada T, Ohnuma K, et al. Humanized anti-CD26 monoclonal antibody as a treatment for malignant mesothelioma tumors. Clin Cancer Res , 2007, 13 (14) : 4191–4200. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0110 |

| [27] | Pang R, Law W L, Chu A C, et al. A subpopulation of CD26+ cancer stem cells with metastatic capacity in human colorectal cancer. Cell Stem Cell , 2010, 6 (6) : 603–615. DOI:10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.001 |

| [28] | Ghani F I, Yamazaki H, Iwata S, et al. Identification of cancer stem cell markers in human malignant mesothelioma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun , 2011, 404 (2) : 735–742. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.12.054 |

| [29] | Havre P A, Abe M, Urasaki Y, et al. The role of CD26/dipeptidyl peptidase IV in cancer. Front Biosci , 2008, 13 : 1634–1645. DOI:10.2741/2787 |

| [30] | Bauvois B. A collagen-binding glycoprotein on the surface of mouse fibroblasts is identified as dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Biochem J , 1988, 252 (3) : 723–731. DOI:10.1042/bj2520723 |

| [31] | Gonzalez-Gronow M, Kaczowka S, Gawdi G, et al. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV/CD26) is a cell-surface plasminogen receptor. Front Biosci , 2008, 13 : 1610–1618. DOI:10.2741/2785 |

| [32] | Sedo A, Stremenová J, Bušek P, et al. Peptidyl peptidase-IV and related molecules:markers of malignancy. Expert Opin Med Diagn , 2008, 2 (6) : 677–689. DOI:10.1517/17530059.2.6.677 |

| [33] | Kacar A, Arikok A T, Kokenek Unal T D, et al. Stromal expression of CD34, α-smooth muscle actin and CD26/DPPIV in squamous cell carcinoma of the skin:a comparative immunohistochemical study. Pathol Oncol Res , 2012, 18 (1) : 25–31. DOI:10.1007/s12253-011-9412-9 |

| [34] | Watson P H. Psoriasin (S100A7). The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology , 1998, 30 : 567–571. |

| [35] | Schäfer B W, Heizmann C W. The S100 family of EFhand calcium binding proteins:functions and pathology. Trends Biochem Sci , 1996, 21 (4) : 134–140. DOI:10.1016/S0968-0004(96)80167-8 |

| [36] | Donato R. S100:a multigenic family of calcium-modulated proteins of the EF-hand type with intracellular and extracellular functional roles. Int J Biochem Cell Biol , 2001, 33 (7) : 637–668. DOI:10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00046-2 |

| [37] | Zimmer D B, Cornwall E H, Landar A, et al. The S100 protein family:history, function, and expression. Brain Res Bull , 1995, 37 (4) : 417–429. DOI:10.1016/0361-9230(95)00040-2 |

| [38] | Algermissen B, Sitzmann J, LeMotte P, et al. Differential expression of CRABP Ⅱ, psoriasin and cytokeratin 1 mRNA in human skin diseases. Arch Dermatol Res , 1996, 288 (8) : 426–430. DOI:10.1007/BF02505229 |

| [39] | Al-Haddad S, Zhang Z, Leygue E, et al. Psoriasin (S100A7) expression and invasive breast cancer. Am J Pathol , 1999, 155 (6) : 2057–2066. DOI:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65524-1 |

| [40] | Enerbäck C, Porter D A, Seth P, et al. Psoriasin expression in mammary epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res , 2002, 62 (1) : 43–47. |

| [41] | Moubayed N, Weichenthal M, Harder J, et al. Psoriasin (S100A7) is significantly up-regulated in human epithelial skin tumors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol , 2007, 133 (4) : 253–261. DOI:10.1007/s00432-006-0164-y |

| [42] | Ostergaard M, Rasmussen H H, Nielsen H V, et al. Proteome profiling of bladder squamous cell carcinomas:identification of markers that define their degree of differentiation. Cancer Res , 1997, 57 (18) : 4111–4117. |

| [43] | Moog-Lutz C, Bouillet P, Régnier C H, et al. Comparative expression of the psoriasin (S100A7) and S100C genes in breast carcinoma and co-localization to human chromosome 1q21-q22. Int J Cancer , 1995, 63 (2) : 297–303. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0215 |

| [44] | Leygue E, Snell L, Hiller T, et al. Differential expression of psoriasin messenger RNA between in situ and invasive human breast carcinoma. Cancer Res , 1996, 56 (20) : 4606–4609. |

| [45] | Dey K K, Sarkar S, Pal I, et al. Mechanistic attributes of S100A7(psoriasin) in resistance of anoikis resulting tumor progression in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity. Cancer Cell Int , 2015, 15 : 94. DOI:10.1186/s12935-015-0244-7 |

| [46] | Krop I, März A, Carlsson H A, et al. Putative role for psoriasin in breast tumor progression. Cancer Res , 2005, 65 (24) : 11326–11334. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1523 |

| [47] | Royse K E, Zhi D, Conner M G, et al. Differential gene expression landscape of co-existing cervical pre-cancer lesions using RNA-seq. Front Oncol , 2014, 4 : 339. |

| [48] | Hammarström S. The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) family:structures, suggested functions and expression in normal and malignant tissues. Semin Cancer Biol , 1999, 9 (2) : 67–81. DOI:10.1006/scbi.1998.0119 |

| [49] | Yoon J, Terada A, Kita H. CD66b regulates adhesion and activation of human eosinophils. J Immunol , 2007, 179 (12) : 8454–8462. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.179.12.8454 |

| [50] | Skubitz KM, Skubitz AP. Interdependency of CEACAM-1, -3, -6, and -8 induced human neutrophil adhesion to endothelial cells. J Transl Med , 2008, 6 (1) : 78. DOI:10.1186/1479-5876-6-78 |

| [51] | Torsteinsdóttir I, Arvidson N G, Hällgren R, et al. Enhanced expression of integrins and CD66b on peripheral blood neutrophils and eosinophils in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and the effect of glucocorticoids. Scand J Immunol , 1999, 50 (4) : 433–439. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00602.x |

| [52] | Zhao L, Xu S, Fjaertoft G, et al. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for human carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 8, a biological marker of granulocyte activities in vivo. J Immunol Methods , 2004, 293 (1-2) : 207–214. DOI:10.1016/j.jim.2004.08.009 |

| [53] | Mawhorter S D, Stephany D A, Ottesen E A, et al. Identification of surface molecules associated with physiologic activation of eosinophils:application of whole-blood flow cytometry to eosinophils. J Immunol , 1996, 156 (12) : 4851–4858. |

| [54] | Schmidt T, Zündorf J, Grüger T, et al. CD66b overexpression and homotypic aggregation of human peripheral blood neutrophils after activation by a gram-positive stimulus. J Leukoc Biol , 2012, 91 (5) : 791–802. DOI:10.1189/jlb.0911483 |

| [55] | Graham R A, Wang S, Catalano P J, et al. Postsurgical surveillance of colon cancer:preliminary cost analysis of physician examination, carcinoembryonic antigen testing, chest x-ray, and colonoscopy. Ann Surg , 1998, 228 (1) : 59–63. DOI:10.1097/00000658-199807000-00009 |

| [56] | Grunnet M, Sorensen J B. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) as tumor marker in lung cancer. Lung Cancer , 2012, 76 (2) : 138–143. DOI:10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.11.012 |

| [57] | Esteban J M, Felder B, Ahn C, et al. Prognostic relevance of carcinoembryonic antigen and estrogen receptor status in breast cancer patients. Cancer , 1994, 74 (5) : 1575–1583. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0142 |

| [58] | Kim J, Kaye F J, Henslee J G, et al. Expression of carcinoembryonic antigen and related genes in lung and gastrointestinal cancers. Int J Cancer , 1992, 52 (5) : 718–725. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0215 |

2016, Vol. 36

2016, Vol. 36