文章信息

- 何石宝, 李冠楠, 郭东东, 唐文超, 隆耀航, 朱勇

- HE Shi-bao, LI Guan-nan, GUO Dong-dong, TANG Wen-chao, LONG Yao-hang, ZHU Yong

- 果蝇求偶行为分子调控机制的研究进展

- Study of Courtship Behavior Molecular Regulatory Mechanism in Drosophila

- 中国生物工程杂志, 2015, 35(10): 78-85

- China Biotechnology, 2015, 35(10): 78-85

- http://dx.doi.org/10.13523/j.cb.20151012

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2015-06-02

2. 家蚕基因组生物学国家重点实验室 重庆 400715

2. State Key Laboratory of Silkworm Genome Biology, Chongqing 400715, China

自然界中昆虫进行交配过程需要经过一系列交配前两性之间的信息交流,即求偶行为。昆虫的求偶行为是雄性吸引雌性或雌性吸引雄性的一种定向行为。通过这种求偶行为(如动作、声音等)可向异性传递信息,激发异性的性活动,为两性完成交配创造条件[1]。在果蝇中雄性的求偶行为是物种间的一种固有行为。果蝇(Drosophila)的求偶行为具有多种功能,最重要的功能就是吸引配偶、配偶选择并形成一定的配偶关系,如当雄性要向雌性求偶时,雄性就会从事一系列的相关活动,包括朝向、跟随雌性和唱求偶歌曲[2, 3]。近年来的研究表明,果蝇的这些行为活动受到一系列基因的调控,而且果蝇行为表型还受到神经系统的性别分化的影响[4, 5, 6, 7, 8]。雌性面对雄性发出的求偶信号通过接受或拒绝等方式处理接收到的信号,通过一系列的活动使两性之间的性神经兴奋同步而有利于完成求偶过程,为进一步完成交配做准备[9]。

1 果蝇求偶行为相关基因的结构特征 1.1 果蝇fru基因的结构特征1963年,Gill[10]第一次分离出一种基因产物,发现它能够调控果蝇的求偶行为。1978年,Hall[11]试验也发现了这种产物,经过Gill的允许将其命名为fruitless(fru)。1996年Ito等[12]和Ryner等[13]分离出一个新的fruitless突变体基因,发现fru基因是雄性求偶行为的第一个调控基因,对求偶行为起到了至关重要的作用。

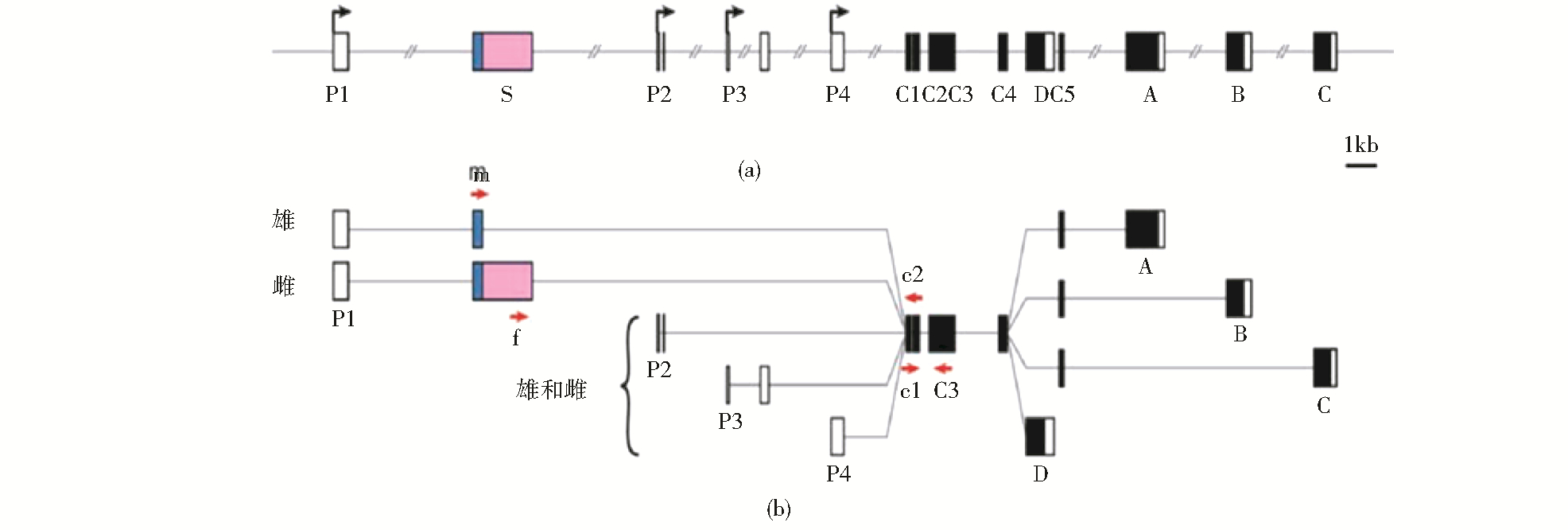

果蝇fru基因位于第3号常染色体上,fru基因全长大约为130 kb,cDNA全长2 876 bp,主要在神经元和腹部肌肉(MOL)中表达[14, 15, 16]。fru基因在雄性中编码一条含776个氨基酸的多肽,而在雌性中编码一条含675个氨基酸的多肽。Fru蛋白还包含一个BTB-锌指蛋白结构域[15, 17, 18, 19, 20]。利用PCR扩增和生物信息学对全部目标区域的序列进行分析[16],结果确定了fru基因至少有4个启动子[19, 21, 22, 23, 24],发现只有从P1开始转录的转录物才包含S外显子,编码的雄性特异性蛋白FruM是雄性性行为和定向行为所必需的[22, 25, 26](图 1)。并用荧光定量PCR试验验证了预测转录产物确实能在相关部位产生[27]。

|

| 图 1 果蝇fru基因的结构和特异性剪接方式[22] Fig. 1 Structure and specifically splicing pattem of fru in Drosophila[22] (a) Structure of the fru gene (b) Transcripts of the fru gene P1~P4: Alternative promoters;S: Sex-specifically spliced exon found only in P1 transcripts; C1~C5:Common exons; A~D: Alternative 3′exons |

Finley等[28]认为dsf基因对雌雄果蝇的求偶行为也是必需的,并且对雌雄果蝇性别特异神经的发育和功能都十分重要。Finley等[29]还发现Dsf蛋白在雌雄果蝇中的表达模式和时间是相似的。dsf雄性是中间性,能与雌性和其它雄性发出求偶行为,但和交配有关的腹部弯曲存在着缺陷。

果蝇dsf基因位于第2号常染色体上,dsf基因全长13 kb左右,cDNA全长3 049 bp,5个外显子,包含2个启动子,有两种转录产物,编码DsfA和DsfB两种蛋白质,蛋白质含有序列为691个氨基酸,dsf基因主要在神经元中表达。Dsf蛋白包含一个DBD和LBD结构域[30]。dsf基因的一个内含子包含一个Tra结合位点相似的序列,并作用于性别特异的剪接因子Tra的下游,意味着dsf基因是Tra蛋白所调控的第三个目标基因[31]。

1.3 果蝇retn基因的结构特征果蝇的retn基因位于第2号常染色体上,retn基因的全长超过23 kb,产生3.7 kb cDNA,编码一条含911个氨基酸的多肽。retn基因有12个外显子,大部分被小于100 bp的内含子隔开,外显子1与2、4和6及6和7被几kb的内含子隔开。通过分析选择性剪切过程发现外显子1和4、1和8、4和8、4和11只在蛹期出现,其他的剪接在不同时期均有出现。且retn编码一个ARID-box核受体,包含保守的DNA结合域[32, 33]。

2 果蝇求偶行为的分子调控机制 2.1 fru对果蝇求偶行为的分子调控机制果蝇的求偶行为是受多基因调控的一种复杂行为,交配前的求偶行为具有复杂的性别二态性[4, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38]。随后,Baker等[39]发现,在雌果蝇中表达雄特异的FruM蛋白,也会发生同性之间的求偶现象,即雌蝇向雌蝇求偶。fru基因在雄果蝇求偶行为和神经元性别分化中发挥十分重要的作用,是一个主要的开关基因[19, 35, 37, 38, 40]。fru基因作为果蝇求偶行为的一个“开关”基因[41, 42],这个开关基因对果蝇的求偶行为的调控是“必须且充分的”,在雄性求偶过程中起到十分重要的作用[43];当“开关”打开,求偶行为正常进行,当“开关”关闭,雄性整个求偶行为过程将被中断,表现出雌性行为[22, 39]。fru基因通过转录产物的选择性剪接来完成果蝇求偶行为的调控[15, 18]。雄性特异的剪接方式,是雄性果蝇求偶行为和神经分化所必需的[15, 22, 43]。雄性特异的FruM在行为“开关”系统中作用更偏向于雄性方向和求偶活动[44, 45, 46]。最近Baker等[39]的研究发现,雄性果蝇中的fru基因事实上在雌性果蝇中也存在,他们通过遗传技术将雌性中fru基因打开,结果发现fru基因打开的雌性果蝇表现出与雄性一样的求偶行为,例如:追逐其它的雌性、轻拍它们的腹部及震动翅膀唱“情歌”。而关闭正常的雄性fru基因的果蝇就会失去雄性的求偶行为,在求偶过程中表现出雌性行为[22, 39]。fru在整个级联网络的位置是从tra基因处开始分支的,与dsx基因一样,也是在tra基因的调控下发生不同的剪接方式[47],FruM蛋白作为一个转录调节因子参与调节一个或多个目标基因的表达,通过这种转录物调控果蝇的性行为和腹部结构的分化,从而调控求偶行为[16, 46]。

Stockinger等[40]利用fruM基因编码序列构建了fruGAL4转基因果蝇,用于寻找直接表达fru基因的目标细胞;发现它在多数外周感觉系统相关神经元(如味觉、嗅觉等)处均有表达。Billeter等[48]通过在fru上插入Gal4基因发现,雄果蝇中枢神经系统中的fru基因具有确立雄性求偶行为的作用。此外,研究人员们通过RNAi干扰技术对fru基因进行沉默干扰发现,干扰fru的表达会影响雄果蝇的求偶行为和中枢神经系统的性别分化[15, 22, 27, 49]。fru基因除了在果蝇求偶过程中扮演了关键角色外,还在果蝇争斗过程中起到了十分重要的作用[50, 51]。研究人员们发现,果蝇发生争斗时,雌性大多数情况会推或撞击对手的身体,而雄性多数情况是刺向或击打对手的后肢甚至会折断其前肢。反过来,如果将果蝇雌雄性体内不同的fru基因互换,果蝇这种争斗方式也正好相反,雌性争斗的方式就会像雄性一样,而雄性的争斗方式如同雌性。

1996年,Ito等[12]、Ryner等[13]通过原位杂交实验发现在雌雄果蝇的中枢神经系统中都能检测到fru mRNA。利用免疫组织化学方法检测发现FruM蛋白只在雄性的中枢神经系统中表达,而不在雌性的中枢神经系统中表达[25, 26, 44, 52]。这些结果表明FruM蛋白存在与否决定神经元的性别,当有一个细胞中有FruM蛋白就发育成雄性细胞,没有FruM蛋白就发育成雌性细胞[45]。随后Yamamoto等[53]通过抑制Tra的翻译发现,fru在雌雄果蝇的中枢神经系统中都有转录,但是只在雄性中枢神经系统中表达出FruM蛋白。因此,FruM蛋白如果只在雌果蝇的神经系统中表达,突变的这些雌性果蝇表现出向其它雌果蝇求偶现象,但因其是雌性所以无法完成交配行为的全过程。相反,雄果蝇如果只表达雌性特异的FruF蛋白,这些雄果蝇就会发育成不育的雄性,并失去雄性的固有的特性,而表现出雌性的特性[22, 49]。

2.2 dsf对果蝇求偶行为的分子调控机制dsf是依赖于tra而独立于dsx基因的另一个求偶行为调控基因,该基因是一个雌果蝇性行为相关基因,在雌雄果蝇中,dsf基因的缺失会引起性别特异的神经和行为表型出现,dsf突变的雌性不会接受雄性的交配,并产下不正常的卵[48]。dsf基因对于雌雄果蝇的求偶行为和性别特异的神经发育是必需的,并发现dsf编码一种核受体,在雌雄果蝇的神经系统都有表达[29],此后Pitman等[30]的试验也发现dsf编码的核受体是一种转录阻遏物。

Finley等[28, 29]发现,dsf在性别决定级联中的功能可能发生在翻译后,例如,Dsf蛋白通过发生性别特异性修饰,由修饰后的Dsf蛋白来控制Tra的目标或者协同调控Tra目标的下游基因。Shirangi等[54]发现dsf基因可能是受到fru基因或者是一个未被鉴定的基因y调控的。在果蝇中,需要从多层次来了解dsf是怎样调控性别行为和神经系统的功能。Pitman等[30]的实验检测到了dsf的转录调控性能,结果发现dsf的缺失会影响雌雄果蝇的性行为和性别特异的神经系统的发育。

Finley等[28]试验证明,dsf基因的突变会导致果蝇异常的交配行为。dsf突变的雄性除了对雌性拥有旺盛的交配能力外,对其它的雄性一样也能形成暂时性的求偶短链,甚至表现出高涨的行为,试图与其它的雄性发生交配;此外,dsf突变的雄果蝇交配时间被极大地延长,这种表型可能是由于突变的雄性腹部弯曲缺陷和雄性的生殖器官与雌性接触能力减弱所导致的[55]。而雌性dsf突变体则表现出接受能力减弱的现象,当dsf雌性与野生型雄性放在一起时,雌性表现出逃走、扇动翅膀和踢腿等行为来主动抵抗雄性的求偶[28]。在dsf雌性中,子宫周围的肌肉缺乏运动神经的支配,相比之下,野生型雌性的子宫周围有大量的运动神经支配。dsf雌性的其它生殖器官包括受精囊、输卵管等的肌肉都有正常的运动神经分布。dsf突变雌性保留成熟的卵在子宫中既没有产下也没有因为储存的精子而受精。显然这种结果是由于子宫肌肉的运动神经分布的减少所致[56]。

Finley等[28]和O’Kane等[55]的研究表明,在神经系统中dsf主要参与性别分化的特定方面。根据多种突变表型的结果表明dsf与fru、dsx具有类似的功能,其编码的蛋白主要作用就是调控特定细胞的性别取向,同时它们的存在和激活也受到Tra的调控[28, 54, 55]。

2.3 retn对果蝇求偶行为的分子调控机制Ditch等[57]发现retn的表达主要是抑制通过fruM激活的雄性行为途径。在果蝇中retn基因突变会导致雌性行为缺陷,并改变中枢神经系统中特定的神经元。retn会影响性别特定神经元的发育,同时还可能抑制雌性中枢神经系统中的雄性行为模式。在缺乏雄性特异FruM蛋白的情况下,retn是一个主要的雄性求偶行为阻遏物[42, 54]。在retn雌性表现出不同于fru而类似雄性的求偶行为,并对雄性的求偶行为有强烈的抵抗性。胚胎后期,retn的RNAs只在中枢神经系统和眼睛的特定细胞中表达[57]。retn基因编码一个ARID-box转录因子,ARID-box的突变会影响果蝇的生存能力[58, 59]。Retn具有多种功能,如胚胎的分化、前后轴和背腹轴基因的表达调控及雌性行为的改变(如对雄性求偶行为强烈的抵抗性及产生雄性样的求偶行为)等[59, 60]。Ditch等[57]通过检测retn改变雄性行为和功能的试验发现,retn突变的雄性与雌性在求偶方面与其它雄性没有显著差异且都有正常的MOL,在交配上也没有延迟现象。此外,retn突变的雄性也能产生运动型精子和正常的交配活动,但是在精子移动方面有缺陷及部分不育[57]。

retn基因通过与fru和dsx在细胞内相互作用来控制求偶活动,通过改变fru和dsx基因的表达来改变retn细胞性别的表型[42, 43]。研究者[46]发现,retn的过表达会抑制雄性与野生型雌性交配,retn基因在雌雄果蝇中的作用就是抑制雄性固有的行为,并提高雌性接受能力。雄性向雌性改变是抑制雄性求偶活动,而雌性向雄性的改变是促进求偶活动。在雄性中,雌性化的retn细胞通过表达Tra并不减弱求偶活动。在雌性中,雄性化的retn神经元通过RNAi特异性干扰Tra产生雌性并不表现的求偶行为,在控制求偶生殖活动中,retn和fru或retn和dsx之间的作用是直接或间接的[42, 57]。

2.4 其他分子调控机制在果蝇中基因突变会影响体细胞性别决定也会影响求偶行为,表明这种行为是由确定性别分化的其他方面的相同机制来控制的[61, 62]。XX雌性表达Sex lethal(Sxl)蛋白质,而Sxl蛋白调节tra基因转录的mRNA发生选择性剪接,以致于Tra蛋白质在雌性中而不是在雄性中表达。Tra蛋白是体细胞分化的一个总的调节器[62]。XY tra突变体是表型上的正常雄性;XX tra突变体是核型雌性,但在体细胞组织上是表型雄性。相反,在XY核型雄性中tra的异常表达就会导致体细胞向雌性方向分化[63, 64]。

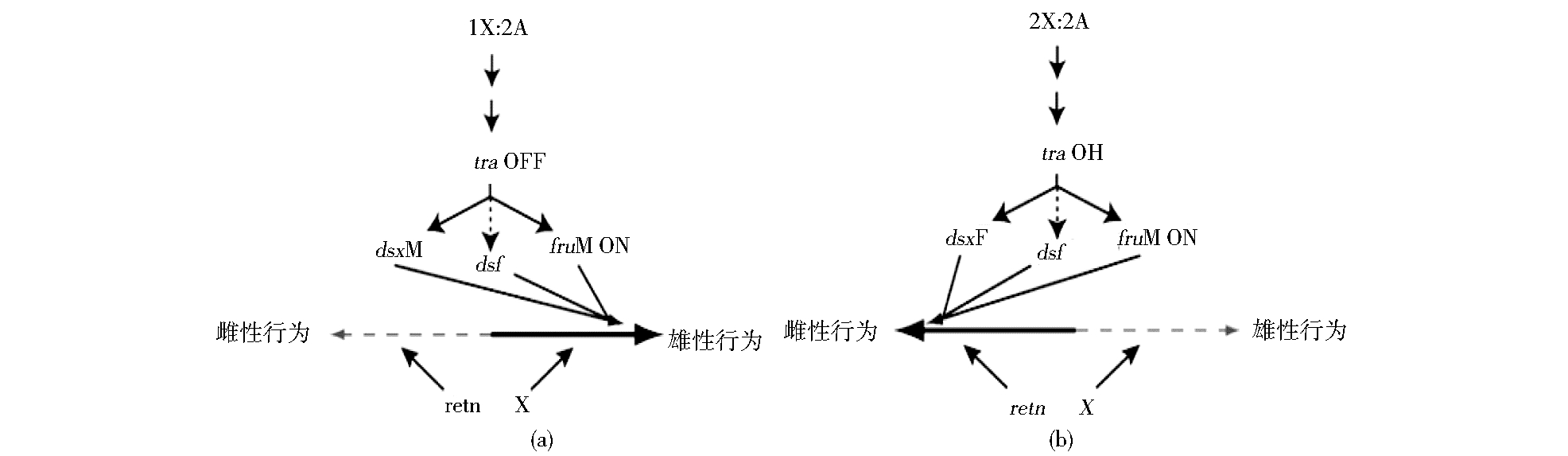

果蝇性别专一性行为受到性别二态型的神经系统的调控[38, 39, 65, 66, 67]。果蝇的性别决定受到一系列相关基因的级联调控,如X/A→sxl→tra,tra-2→dsx、fru和dsf这样的调控网络。果蝇常染色体上的连锁基因tra、tra-2和dsx都受到X连锁基因sxl的调控。当X/A的比值大于或等于1时(即XX型胚胎)激活sxl基因,这个基因的产物调控tra基因发生选择性剪接,产生雌性特异性转录产物,而Tra蛋白又调控dsx、fru和dsf基因发生雌性特异性剪接,从而控制着雌性个体的发育和行为[47]。而X/A的比值小于1时(XY型胚胎)中sxl不被激活,即没有tra基因的表达,所以没有Tra蛋白,故发生雄性特异性剪接[68, 69]。因此,由dsx和fru产生雄性特异性剪接产物DsxM和FruM控制雄性的形态结构和行为[68, 70]。在这个调控网络中,任何一个环节的改变都有可能使性别特征发生改变,如雄果蝇缺乏dsx基因就发育为中间型,表现出较低的雄性求偶行为[43]。

3 果蝇求偶基因间的关系Fru、dsf和dsx基因都在tra基因下游[71],fru和dsf基因主要决定雄性的求偶行为,retn基因参与雌性行为的决定,而体细胞的性别则受dsx基因的决定[39, 54, 69, 72, 73, 74]。Shirangi等[42, 54]认为性别决定基因dsx、fru以及非性别决定基因retn对果蝇的性行为都有影响。如在fruM存在或缺失的条件下,由retn和fruF共同作用来抑制雌性出现雄性求偶行为。仅仅靠fruM基因来调控雄性求偶行为是不充分的,还有另外一条不依赖于fruM的途径调控着果蝇的雄性求偶行为,这条途径被fruM基因所激活,而受retn基因所抑制。retn基因突变的雌果蝇,即使不表达雄性化的DsxM蛋白,这种雌蝇也会拒绝其它雄蝇的求偶[57]。因此,果蝇所表现的雄性求偶行为是受双开关基因调控的,这些基因一起共同影响着神经系统的形成和功能,并在调控其它发育相关基因的基础上调控着果蝇的求偶交配行为[42, 54, 61](图 2)。

随着果蝇全基因组测序的完成,果蝇求偶行为的分子调控机制已成为近十年来的研究焦点。果蝇是双翅目昆虫的模式生物,利用其遗传背景十分清楚的优势,对果蝇求偶行为的研究,可以为其他昆虫的研究和应用提供参考。果蝇求偶行为的研究表明,单个基因的突变也会对其求偶行为有一定的影响。目前,这方面的研究基本是围绕中枢神经系统的性别分化展开的,但是其求偶行为的机理并未研究清楚,调控求偶行为相关基因之间的关系也不清楚。因此,对果蝇求偶行为方面的研究为掌握果蝇性别分化开辟了一条新的路径。形成从生殖细胞、体细胞和神经细胞性别分化三条途径来调控性别分化,为其他物种(如家蚕)性别分化的研究提供了新的思路。

| [1] | 刘若楠, 颜忠诚. 昆虫求偶行为方式及生物学意义. 生物学通报, 2009, 43(9): 6-8. Liu R N, Yan Z C. Courtship behavior style and biological significance in insects. Bulletin of Biology, 2009, 43(9): 6-8. |

| [2] | Yamamoto D, Jallon J M, Komatsu A. Genetic dissection of sexual behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Annual Review of Entomology, 1997, 42(1): 551-585. |

| [3] | Spieth H T. Courtship behavior in Drosophila. Annual Review of Entomology, 1974, 19(1): 385-405. |

| [4] | Rideout E J, Dornan A J, Neville M C, et al. Control of sexual differentiation and behavior by the doublesex gene in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature Neuroscience, 2010, 13(4):458-466. |

| [5] | venken K J, Simpson J H, Bellen H J. Genetic manipulation of genes and cells in the nervous system of the fruit fly. Neuron, 2011,72(2):202-230. |

| [6] | Pan Y, Robinett C C, Baker B S. Turning males on: activation of male courtship behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. PLos One, 2011, 6:e21144-e21158. |

| [7] | Pan Y, Messner G W, Baker B S. Joint control of Drosophila male courtship behavior by motion cues and activation of male-specific P1 neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2012, 109(25):10065-10070. |

| [8] | von Philipsborn A C, Liu T, Yu J Y, et al. Neuronal control of Drosophila courtship song. Neuron, 2011, 69(3):509-522. |

| [9] | Rezával C, Pavlou H J, Dornan A J, et al. Neural circuitry underlying Drosophila female postmating behavioral responses. Current Biology, 2012, 22(13): 1155-1165. |

| [10] | Gill K S. A mutation causing abnormal courtship and mating behavior in males of Drosophila melanogaster. American Zoologist, 1963, 3: 507. |

| [11] | Hall J C. Courtship among males due to a male-sterile mutation in Drosophila melanogaster. Behavior Genetics, 1978, 8(2): 125-141. |

| [12] | Ito H, Fujitani K, Usui K, et al. Sexual orientation in Drosophila is altered by the satori mutation in the sex-determination gene fruitless that encodes a zinc finger protein with a BTB domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1996, 93(18): 9687-9692. |

| [13] | Ryner L C, Goodwin S F, Castrillon D H, et al. Control of male sexual behavior and sexual orientation in Drosophila by the fruitless gene. Cell, 1996, 87(6): 1079-1089. |

| [14] | Zollman S, Godt D, Privé G G, et al. The BTB domain, found primarily in zinc finger proteins, defines an evolutionarily conserved family that includes several developmentally regulated genes in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1994, 91(22): 10717-10721. |

| [15] | Clynen E, Bellés X, Piulachs M D. Conservation of fruitless role as master regulator of male courtship behaviour from cockroaches to flies. Development Genes and Evolution, 2011, 221(1): 43-48. |

| [16] | Takayanagi S, Toba G, Lukacsovich T, et al. A fruitless upstream region that defines the species specificity in the male-specific muscle patterning in Drosophila. Journal of Neurogenetics, 2014, 29(1): 23-29. |

| [17] | Bjorum S M, Simonette R A, Alanis R, et al. The Drosophila BTB domain protein Jim Lovell has roles in multiple larval and adult behaviors. Plos One, 2013, 8(4): e61270-e61286. |

| [18] | Dalton J E, Fear J M, Knott S, et al. Male-specific Fruitless isoforms have different regulatory roles conferred by distinct zinc finger DNA binding domains. BMC Genomics, 2013, 14(1): 659-673. |

| [19] | Nojima T, Neville M C, Goodwin S F. Fruitless isoforms and target genes specify the sexually dimorphic nervous system underlying Drosophila reproductive behavior. Fly, 2014, 8(2): 95-100. |

| [20] | Sadler A J, Rossello F J, Yu L, et al. BTB-ZF transcriptional regulator PLZF modifies chromatin to restrain inflammatory signaling programs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2015, 112(5): 1535-1540. |

| [21] | Lee G, Foss M, Goodwin S F, et al. Spatial, temporal, and sexually dimorphic expression patterns of the fruitless gene in the Drosophila central nervous system. Journal of Neurobiology, 2000, 43(4): 404-426. |

| [22] | Demir E, Dickson B J. Fruitless splicing specifies male courtship behavior in Drosophila. Cell, 2005, 121(5): 785-794. |

| [23] | Salvemini M, Polito C, Saccone G.Fruitless alternative splicing and sex behaviour in insects: an ancient and unforgettable love story? Journal of Genetics, 2010, 89(3): 287-299. |

| [24] | Parker D J, Gardiner A, Neville M C, et al. The evolution of novelty in conserved genes; evidence of positive selection in the Drosophila fruitless gene is localised to alternatively spliced exons. Heredity, 2014, 112(3): 300-306. |

| [25] | Vrontou E, Nilsen S P, Demir E, et al. Fruitless regulates aggression and dominance in Drosophila. Nature Neuroscience, 2006, 9(12): 1469-1471. |

| [26] | von Philipsborn A C, Jörchel S, Tirian L, et al. Cellular and behavioral functions of fruitless isoforms in Drosophila courtship. Current Biology, 2014, 24(3): 242-251. |

| [27] | Boerjan B, Tobback J, Loof A, et al. Fruitless RNAi knockdown in males interferes with copulation success in Schistocerca gregaria. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 2011, 41(5): 340-347. |

| [28] | Finley K D, Taylor B J, Milstein M, et al. Dissatisfaction, a gene involved in sex-specific behavior and neural development of Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 1997, 94(3): 913-918. |

| [29] | Finley K D, Edeen P T, Foss M, et al. Dissatisfaction encodes a tailless-like nuclear receptor expressed in a subset of CNS neurons controlling Drosophila sexual behavior. Neuron, 1998, 21(6): 1363-1374. |

| [30] | Pitman J L, Tsai C C, Edeen P T, et al. DSF nuclear receptor acts as a repressor in culture and in vivo. Developmental Biology, 2002, 245(2): 315-328. |

| [31] | Yamamoto D, Nakano Y. Sexual behavior mutants revisited: molecular and cellular basis of Drosophila mating. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 1999, 56(7-8): 634-646. |

| [32] | Shandala T, Kortschak R D, Saint R. The Drosophila retained/dead ringer gene and ARID gene family function during development. International Journal of Developmental Biology, 2002, 46(4): 423-430. |

| [33] | Shandala T, Takizawa K, Saint R. The dead ringer/retained transcriptional regulatory gene is required for positioning of the longitudinal glia in the Drosophila embryonic CNS. Development, 2003, 130(8): 1505-1513. |

| [34] | Datta S R, Vasconcelos M L, Ruta V, et al. The Drosophila pheromone cVA activates a sexually dimorphic neural circuit. Nature, 2008, 452(7186):473-477. |

| [35] | Goto J, Mikawa Y, Koganezawa M, et al. Sexually dimorphic shaping of interneuron dendrites involves the hunchback transcription factor. Journal of Neuroscience, 2011, 31(14): 5454-5459. |

| [36] | Kimura K. Role of cell death in the formation of sexual dimorphism in the Drosophila central nervous system. Development Growth & Differentiation, 2011, 53(2), 236-244. |

| [37] | Ito H, Sato K, Koganezawa M, et al. Fruitless recruits two antagonistic chromatin factors to establish single-neuron sexual dimorphism. Cell, 2012, 149(6): 1327-1338. |

| [38] | Vernes S C. Genome wide identification of Fruitless targets suggests a role in upregulating genes important for neural circuit formation. Scientific Reports, 2014, 4:4412-4422. |

| [39] | Baker B S, Taylor B J, Hall J C. Are complex behaviors specified by dedicated regulatory genes? Reasoning from Drosophila. Cell, 2001, 105(1): 13-24. |

| [40] | Stockinger P, Kvitsiani D, Rotkopf S, et al. Neural circuitry that governs Drosophila male courtship behavior. Cell, 2005, 121(5): 795-807. |

| [41] | Garcia-Bellido A. Genetic Control of Wing Disc Development in Drosophila. Amsterdam:Elsevier, 1975, 0(29): 161-182. |

| [42] | Shirangi T R, Taylor B J, McKeown M. A double-switch system regulates male courtship behavior in male and female Drosophila melanogaster. Nature Genetics, 2006, 38(12): 1435-1439. |

| [43] | Sato K, Yamamoto D. An epigenetic switch of the brain sex as a basis of gendered behavior in Drosophila. Advances in Genetics, 2014, 86: 45-63. |

| [44] | Usui-Aoki K, Ito H, Ui-Tei K, et al. Formation of the male-specific muscle in female Drosophila by ectopic fruitless expression. Nature Cell Biology, 2000, 2(8): 500-506. |

| [45] | Pan Y, Baker B S. Genetic identification and separation of innate and experience-dependent courtship behaviors in Drosophila. Cell, 2014, 156(1): 236-248. |

| [46] | Tran D H, Meissner G W, French R L, et al. A small subset of fruitless subesophageal neurons modulate early courtship in Drosophila. Plos One, 2014, 9(4): e95472-e95481. |

| [47] | Devineni A V, Heberlein U. Acute ethanol responses in Drosophila are sexually dimorphic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2012, 109(51): 21087-21092. |

| [48] | Billeter J C, Goodwin S F. Characterization of Drosophila fruitless-gal4 transgenes reveals expression in male-specific fruitless neurons and innervation of male reproductive structures. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 2004, 475(2): 270-287. |

| [49] | Latham K L, Liu Y S, Taylor B J. A small cohort of FRUM and Engrailed-expressing neurons mediate successful copulation in Drosophila melanogaster. BMC Neuroscience, 2013, 14(1): 57-72. |

| [50] | Lim M M, Wang Z, Olazábal D E, et al. Enhanced partner preference in a promiscuous species by manipulating the expression of a single gene. Nature, 2004, 429(6993): 754-757. |

| [51] | Alekseyenko O V, Chan Y B, Fernandez M L, et al. Single serotonergic neurons that modulate aggression in Drosophila. Current Biology, 2014, 24(22): 2700-2707. |

| [52] | Lee G, Hall J C. Abnormalities of male-specific FRU protein and serotonin expression in the CNS of fruitless mutants in Drosophila. Journal of Neuroscience, 2001, 21(2): 513-526. |

| [53] | Yamamoto D, Usui-Aoki K, Shima S. Male-specific expression of the Fruitless protein is not common to all Drosophila species. Genetica, 2004, 120(1-3): 267-272. |

| [54] | Shirangi T R, McKeown M. Sex in flies: What ‘body-mind’ dichotomy? Developmental Biology, 2007, 306(1): 10-19. |

| [55] | O'Kane C J, Asztalos Z. Sexual behaviour: courting dissatisfaction. Current Biology, 1999, 9(8):289-292. |

| [56] | Yamamoto D, Fujitani K, Usui K, et al. From behavior to development: genes for sexual behavior define the neuronal sexual switch in Drosophila. Mechanisms of Development, 1998, 73(2): 135-146. |

| [57] | Ditch L M, Shirangi T, Pitman J L, et al. Drosophila retained/dead ringer is necessary for neuronal pathfinding, female receptivity and repression of fruitless independent male courtship behaviors. Development, 2005, 132(1): 155-164. |

| [58] | Gregory S L, Kortschak R D, Kalionis B, et al. Characterization of the dead ringer gene identifies a novel, highly conserved family of sequence-specific DNA-binding proteins. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 1996, 16(3): 792-799. |

| [59] | Valentine S A, Chen G, Shandala T, et al. Dorsal-mediated repression requires the formation of a multiprotein repression complex at the ventral silencer. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 1998, 18(11): 6584-6594. |

| [60] | Shandala T, Kortschak R D, Gregory S, et al. The Drosophila dead ringer gene is required for early embryonic patterning through regulation of argos and buttonhead expression. Development, 1999, 126(19): 4341-4349. |

| [61] | Hall J C. The mating of a fly. Science, 1994, 264(5166): 1702-1714. |

| [62] | Cline T W, Meyer B J. Vive la difference: males vs females in flies vs worms. Annual Review of Genetics, 1996, 30(1): 637-702. |

| [63] | Ferveur J F, Störtkuhl K F, Stocker R F, et al. Genetic feminization of brain structures and changed sexual orientation in male Drosophila. Science, 1995, 267(5199): 902-905. |

| [64] | Arthur B I, Jallon J M, Caflisch B, et al. Sexual behaviour in Drosophila is irreversibly programmed during a critical period. Current Biology, 1998, 8(21): 1187-1190. |

| [65] | Kimura K, Ote M, Tazawa T, et al. Fruitless specifies sexually dimorphic neural circuitry in the Drosophila brain. Nature, 2005, 438(7065):229-233. |

| [66] | Kimura K, Hachiya T, Koganezawa M, et al. Fruitless and doublesex coordinate to generate male-specific neurons that can initiate courtship. Neuron, 2008, 59(5):759-769. |

| [67] | Rezával C, Nojima T, Neville M C, et al. Sexually dimorphic octopaminergic neurons modulate female postmating behaviors in Drosophila. Current Biology, 2014, 24(7): 725-730. |

| [68] | Sosnowski B A, Belote J M, McKeown M. Sex-specific alternative splicing of RNA from the transformer gene results from sequence-dependent splice site blockage. Cell, 1989, 58(3): 449-459. |

| [69] | Fagegaltier D, König A, Gordon A, et al. A genome-wide survey of sexually dimorphic expression of Drosophila miRNAs identifies the steroid hormone-induced miRNA let-7 as a regulator of sexual identity. Genetics, 2014, 198(2): 647-668. |

| [70] | Dauwalder B. The roles of fruitless and doublesex in the control of male courtship. International review of neurobiology, 2011, 99: 87-105. |

| [71] | Salvemini M, D'Amato R, Petrella V, et al. The orthologue of the fruitfly sex behaviour gene fruitless in the mosquito Aedes aegypti: evolution of genomic organisation and alternative splicing. Plos One, 2013, 8(2): e48554-e48570. |

| [72] | Chatterjee S S, Uppendahl L D, Chowdhury M A, et al. The female-specific Doublesex isoform regulates pleiotropic transcription factors to pattern genital development in Drosophila. Development, 2011, 138(6), 1099-1109. |

| [73] | Luo S D, Shi G W, Baker B S. Direct targets of the D. melanogaster DSXF protein and the evolution of sexual development. Development, 2011, 138(13): 2761-2771. |

| [74] | Zhou C, Pan Y, Robinett C C, et al. Central brain neurons expressing doublesex regulate female receptivity in Drosophila. Neuron, 2014, 83(1): 149-163. |

2015, Vol. 35

2015, Vol. 35