有机碳源是微藻和细菌等自养微生物生长发育所需的重要营养物质[1-2]。有机碳源既可以作为自养微生物构建细胞的组分和能源物质[3-4],又能通过乙醛酸循环、三羧酸循环、糖酵解和磷酸戊糖途径等调控其新陈代谢[5]。在自养微生物培养过程中,外加碳源是增加生物量和高价值代谢产物的有效手段[4, 6]。目前,已有许多研究证明了外加碳源对经济型蓝藻培养的正面影响,Yu[7]的研究发现了3.6 g·L-1葡萄糖和4.92 g·L-1乙酸钠是发状念珠藻(Nostoc flagelliforme)生物量和外聚糖积累的最佳浓度。Sharma和Mallick[8]则发现在培养液中含0.4%醋酸和0.4%葡萄糖的条件下,灰色念珠藻(Nostoc muscorum)的聚羟基丁酸达到了最高浓度,占细胞干质量的35%。Kovac等[9]探究了不同有机碳源对螺旋藻藻蓝蛋白含量的影响,结果表明在1.5 g·L-1葡萄糖和3.0 g·L-1甘油的条件下,螺旋藻的藻蓝蛋白含量比没有碳源添加的处理组分别高23和4倍。可见对于经济蓝藻的培养,如何选择最佳的碳源条件是提高生产效率的关键。

葛仙米是一种球状的可食用经济型蓝藻,学名为拟球状念珠藻(Nostoc sphaeroides),主要分布在中国中南部的山地稻田[10]。葛仙米可以通过固定大气中的氮气并释放出有机氮来增加土壤肥力[11-12],同时其本身含有丰富的营养和生物活性物质,如蛋白质、糖类、叶绿素等,因此在食品、药品和化工原料等领域都有重要的应用价值[10, 13]。然而,在过去的三十年中,过度使用氮肥和除草剂导致了葛仙米的天然资源严重减少[14-16]。鉴于葛仙米重要的经济和生态价值,许多学者开始探索其人工培养和恢复的有效措施。例如:汪峰海[17]的研究表明磷元素对葛仙米光合磷酸化具有重要影响,缺磷情况下葛仙米的卡尔文循环效率下降,而一定范围内的高浓度磷有利于葛仙米的生长和光合作用。邱昌恩等[18]发现外加氮源会显著影响葛仙米的光和电子传递速率和生长状况。刘树文等[19]研究了无机碳源对葛仙米的影响,结果表明同时提供CO2和Na2CO3为碳源时会显著增加葛仙米的生物量、生长速率、光合色素含量等生理指标。然而,针对有机碳源对葛仙米的生长和生化组成的影响却鲜有研究。

因此,本研究进行了一项短期的生理生化实验,旨在探究不同种类和浓度的有机碳源对葛仙米生长和生化组成的影响。本文的研究结果将有助于为葛仙米的人工培养和恢复提供高效的碳源供应方案。

1 材料与方法葛仙米来自中国湖北省鹤峰县(29°46′N,110°04′E),取直径约为1 mm的葛仙米细胞接种到含有300 mL无菌BG11培养基的锥形瓶中[20],在温度(23±1) ℃、光照强度50 μmol·m-2·s-1和光∶暗周期10∶14的条件下暂养。培养基每3天更换一次,葛仙米直径达到约2 mm后进行后续实验。

1.1 培养实验使用4种碳源(葡萄糖、蔗糖、丙酮酸钠和乙酸钠)和4个碳源浓度水平(0.01、0.1、0.2和0.4 mol·L-1)进行培养,共16个处理组,同时设置无碳源添加的对照组,每组3个重复。在锥形瓶中加入400 mL含有不同种类和浓度有机碳源的BG11培养基,pH调为7.1后115 ℃高温高压灭菌20 min,冷却后接种3.0 g葛仙米细胞,在与暂养期相同的条件下(温度(23±1)℃、光照强度50 μmol·m-2·s-1、光∶暗周期10∶14)进行培养。培养基每3天更换一次,9 d后收取样品并检测指标。

1.2 相对生长率的测量在实验前后,将所有葛仙米细胞吸干表面水分后进行称重。使用以下公式计算相对生长率:

| $ R G R=100 \times\left(\ln W_t-\ln W_0\right) / t \text { 。} $ |

式中:RGR为相对生长率,单位为%·d-1;W0为初始鲜质量,单位为g;Wt为最终鲜质量,单位为g;t为培养时间,单位为d。

1.3 叶绿素a含量的测量从每个重复中取0.2 g葛仙米进行叶绿素a(Chlorophyll a, Chl a)含量的测定。将葛仙米样品在黑暗中研磨,然后与8 mL 95%乙醇混合。在4 ℃存储24 h后,在4 024g、4 ℃下离心30 min。用分光光度计于665和649 nm处测量上清液吸光度。叶绿素a含量根据以下公式计算[21]:

| $ C_{\mathrm{Chl}\; a}=\left(k_1 \times D_{665}-k_2 \times D_{649}\right) \times V /(1000 \times M) \text { 。} $ |

式中:CChl a为叶绿素a含量,单位为mg·g-1;k1和k2分别为叶绿素a在665和649 nm处的比吸光系数,数值分别为13.95和6.88,单位为mg·L-1;D665和D649分别为上清液在665和649 nm处的吸光度;V为提取液的体积,单位为mL;M为样品的鲜质量,单位为g。

1.4 可溶性糖含量的测定从每个重复中取0.1 g葛仙米进行可溶性糖的测定。将葛仙米样品充分研磨并与4 mL 80%乙醇混合后转移至5 mL离心管中,然后在80 ℃水浴中振荡30 min。在6 000g的条件下离心10 min后收集上清液。再用2 mL 80%乙醇重复提取两次。混合所有上清液,用80%乙醇定容至10 mL。混匀后取1 mL溶液,加入4 mL邻苯酚,在100 ℃水浴中加热10 min。使用分光光度计在620 nm处测量上清液的吸光度。可溶性糖含量根据Morse等[22]的方法进行计算。

1.5 可溶性蛋白含量的测定从每个重复中取0.5 g葛仙米样品,并与4.5 mL磷酸盐缓冲液(0.1 mol/L,pH=7.4)一起研磨。以13 000g离心15 min。取上清液,根据Bradford[23]的方法,使用考马斯亮蓝G-250染料(南京建成生物工程研究所,中国南京)测定可溶性蛋白含量。

1.6 藻蓝蛋白含量的测定每个重复中取0.5 g样品,去除表面水分后,使用4.5 mL磷酸盐缓冲液(0.1 mol/L,pH=7.2)在0 ℃下研磨。然后以13 000g离心15 min,取上清液。使用紫外分光光度计分别在615和652 nm处记录上清液的吸光度。藻蓝蛋白含量由以下公式计算[24]:

| $ C_{\mathrm{PC}}=\left(D_{615}-0.474 \times D_{652}\right) \times V /\left(k_3 \times M\right) \text { 。} $ |

式中:CPC为藻蓝蛋白含量,单位为mg·g-1;D615和D652分别为上清液在615和652 nm处的吸光度;V为提取液的体积,单位为mL;k3为将吸光度转化为藻蓝蛋白浓度的特异吸收系数,数值为5.34,单位为mL·mg-1;M为样品的鲜质量,单位为g。

1.7 数据分析使用SPSS 25.0进行数据分析。采用双因素方差分析(Two-way ANOVA)检验有机碳源类型和浓度对葛仙米相对生长率和生化成分的影响。当实验处理之间检测到显著差异时,使用Duncan多重比较检验(P<0.05)进一步分析。

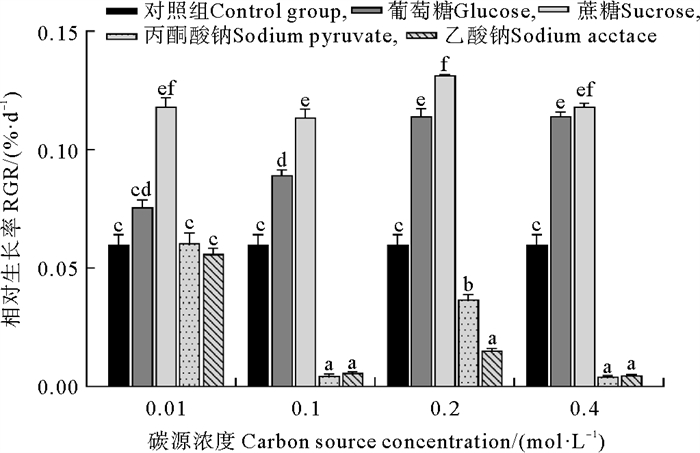

2 结果 2.1 相对生长速率数据分析结果显示,葛仙米的相对生长率(Relative growth rate, RGR)显著受到有机碳源种类和浓度的影响,且碳源种类和浓度之间存在显著的交互作用(见表 1),具体结果如图 1所示。在蔗糖浓度为0.01和0.1 mol·L-1的培养条件下,葛仙米的RGR显著高于其他处理组(P<0.000 1)。在碳源浓度为0.2和0.4 mol·L-1时,虽然葡萄糖和蔗糖处理之间的RGR差异不显著(P>0.05),但均显著高于其他处理组。4个不同浓度的蔗糖处理组间的RGR没有显著差异(P>0.05)。在葡萄糖处理组中,0.01和0.1 mol·L-1浓度下培养的葛仙米的RGR显著低于0.2和0.4 mol·L-1浓度下的葛仙米的RGR(P<0.000 1)。在用丙酮酸钠和乙酸钠培养时,0.01 mol·L-1浓度组的葛仙米的RGR显著高于其他浓度组(P<0.000 1)。当蔗糖浓度为0.2 mol·L-1时葛仙米的RGR最大,为0.114%·d-1。

|

|

表 1 双因素ANOVA检验下有机碳源种类与浓度对葛仙米生长和生化成分的影响 Table 1 Effects of organic carbon source type and concentration on the relative growth rate and biochemical parameters of Nostoc sphaeroides using two-way ANOVA test |

|

( 误差线处字母相同表示组间差异不显著,字母不同表示组间差异显著,α=0.05。The same letter at the error bar indicates that the difference between the groups is not significant, while different letters indicate significant differences, α=0.05. ) 图 1 不同培养条件下葛仙米的RGR Fig. 1 RGR of N. sphaeroides under different culture conditions |

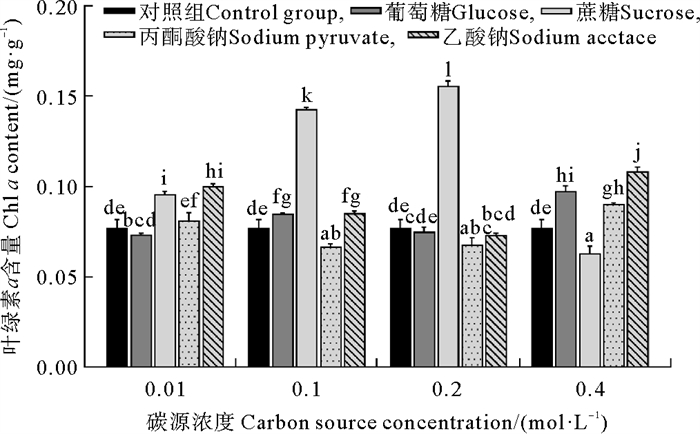

叶绿素a含量受有机碳源种类和浓度显著影响,且它们之间存在显著的交互作用(见表 1),具体结果如图 2所示。在碳源浓度为0.1和0.2 mol·L-1时,蔗糖处理组的叶绿素a含量显著高于其他碳源处理组(P<0.000 1)。在蔗糖浓度从0.01 mol·L-1升高至0.2 mol·L-1时叶绿素a含量显著增加(P<0.000 1),但在蔗糖浓度到0.4 mol·L-1时又显著下降(P<0.000 1)。当蔗糖浓度为0.2 mol·L-1时,葛仙米的叶绿素a含量达到最大值,为0.156 mg·g-1。

|

( 误差线处字母相同表示组间差异不显著,字母不同表示组间差异显著,α=0.05。The same letter at the error bar indicates that the difference between the groups is not significant, while different letters indicate significant differences, α=0.05. ) 图 2 不同培养条件下葛仙米的叶绿素a含量 Fig. 2 Chl a content of N. sphaeroides under different culture conditions |

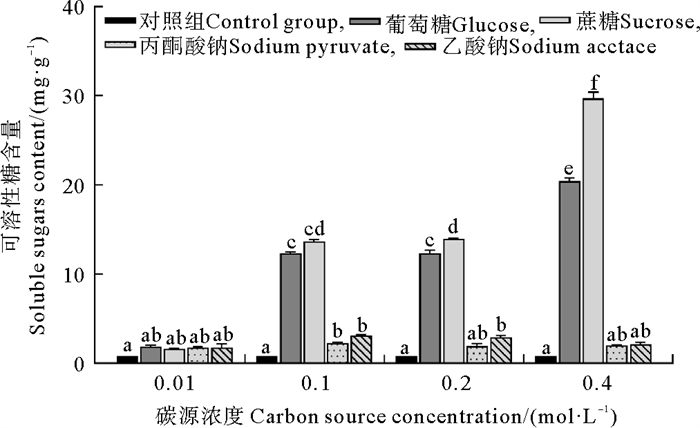

方差分析显示,有机碳源种类和浓度对葛仙米可溶性糖含量产生了显著影响,它们之间存在显著的交互作用(见表 1),具体结果如图 3所示。在碳源浓度为0.01 mol·L-1时,碳源种类没有造成可溶性糖含量的显著差异(P>0.05),而在较高浓度下,葡萄糖和蔗糖处理的可溶性糖含量显著增加。在碳源浓度为0.2和0.4 mol·L-1时,蔗糖处理组的可溶性糖含量显著高于葡萄糖处理组。其中,碳源浓度为0.2 mol·L-1时,蔗糖与葡萄糖处理组的差异显著(P=0.009 4),而在0.4 mol·L-1时,这一差异达到极显著水平(P<0.000 1)。在葡萄糖和蔗糖处理时,随着碳源浓度从0.01 mol·L-1增加到0.4 mol·L-1,葛仙米的可溶性糖含量显著增加(P<0.000 1)。当蔗糖浓度为0.4 mol·L-1时,葛仙米的可溶性糖含量达到最大值,为29.690 mg·g-1。

|

( 误差线处字母相同表示组间差异不显著,字母不同表示组间差异显著,α=0.05。The same letter at the error bar indicates that the difference between the groups is not significant, while different letters indicate significant differences, α=0.05. ) 图 3 不同培养条件下葛仙米的可溶性糖含量 Fig. 3 Soluble sugar content of N. sphaeroides under different culture conditions |

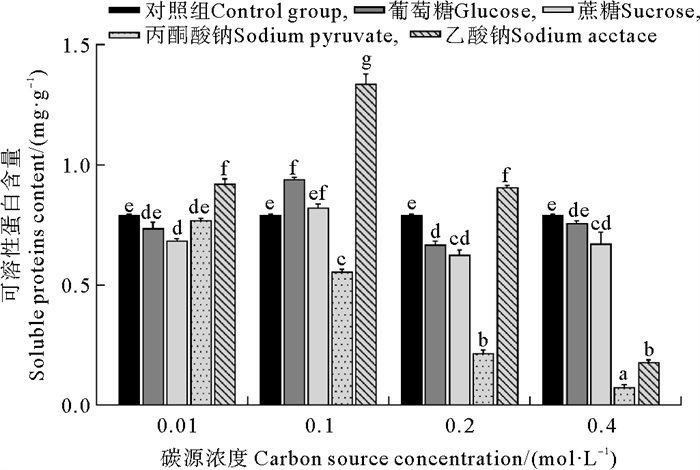

可溶性蛋白含量受有机碳源种类和浓度显著影响。碳源种类和浓度之间也存在显著的交互作用(见表 1),具体结果如图 4所示。在碳源浓度为0.01~0.2 mol·L-1时,乙酸钠处理组的可溶性蛋白含量显著高于其他处理组。在0.01 mol·L-1碳源浓度下,乙酸钠处理组的可溶性蛋白含量显著高于对照组(P=0.001 4),且相比其他处理组差异更为显著(P<0.000 1)。在碳源浓度为0.1 mol·L-1时,乙酸钠处理组可溶性蛋白含量与其他组的差异均非常显著(P<0.000 1)。当碳源浓度提升至0.2 mol·L-1时,乙酸钠处理组可溶性蛋白含量与对照组存在显著差异(P=0.010 6),与其余组的差异则更为显著(P<0.000 1)。乙酸钠处理组的可溶性蛋白含量在乙酸钠浓度从0.01 mol·L-1提升至0.1 mol·L-1时显著增加(P<0.001),但之后又显著下降(P<0.000 1)。当乙酸钠浓度为0.1 mol·L-1时葛仙米的可溶性蛋白含量达到最大值,为1.338 mg·g-1。使用丙酮酸钠作为碳源培养葛仙米时,随着丙酮酸钠浓度的增加,可溶性蛋白含量显著减少(P<0.000 1)。

|

( 误差线处字母相同表示组间差异不显著,字母不同表示组间差异显著,α=0.05。The same letter at the error bar indicates that the difference between the groups is not significant, while different letters indicate significant differences, α=0.05. ) 图 4 不同培养条件下葛仙米的可溶性蛋白含量 Fig. 4 Soluble protein content of N. sphaeroides under different culture conditions |

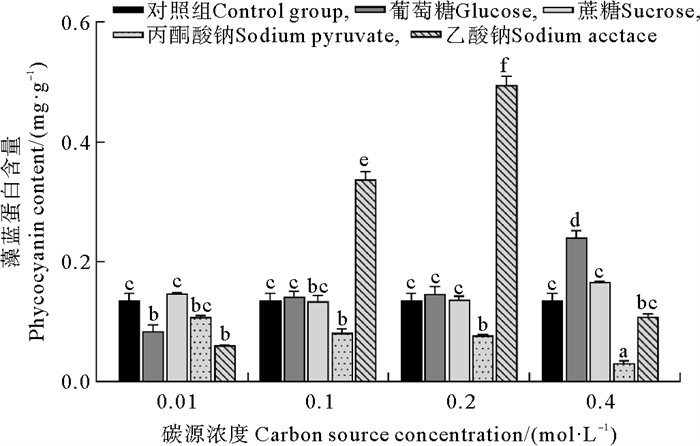

藻蓝蛋白含量受有机碳源种类和浓度的影响显著,它们之间存在显著的交互作用(见表 1),具体结果如图 5所示。碳源浓度为0.1和0.2 mol·L-1时,乙酸钠处理组的藻蓝蛋白含量显著高于其他处理组(P<0.000 1)。碳源浓度为0.4 mol·L-1时,葡萄糖处理组的藻蓝蛋白含量显著高于其他处理组(P<0.000 1)。在葡萄糖处理组中,随着葡萄糖浓度的增加,藻蓝蛋白含量也显著增加。而在丙酮酸钠处理组中,当丙酮酸钠浓度增加至0.4 mol·L-1时,藻蓝蛋白含量显著下降(P<0.000 1)。相比之下,乙酸钠处理组的藻蓝蛋白含量在乙酸钠的浓度从0.01 mol·L-1提升至0.2 mol·L-1的过程中显著增加(P<0.000 1),但在乙酸钠浓度为0.4 mol·L-1时显著下降(P<0.000 1)。当乙酸钠浓度为0.2 mol·L-1时葛仙米的藻蓝蛋白含量达到最大值,为0.495 mg·g-1。

|

( 误差线处字母相同表示组间差异不显著,字母不同表示组间差异显著,α=0.05。The same letter at the error bar indicates that the difference between the groups is not significant, while different letters indicate significant differences, α=0.05. ) 图 5 不同培养条件下葛仙米的藻蓝蛋白含量 Fig. 5 Phycocyanin content of N. sphaeroides under different culture conditions |

如表 1所示,有机碳源种类对所有测量指标的影响均极显著(P<0.001),表明碳源种类的变化会显著影响葛仙米的生长和代谢。同样的,有机碳源浓度对除叶绿素a以外的测量指标影响也极显著(P<0.001),对叶绿素a的影响显著但相对较小(P<0.05),这表明不同浓度的碳源能调节葛仙米的生长和生理生化指标,但叶绿素a对碳源浓度的敏感性相对较低。碳源种类和浓度之间的交互作用对所有测量的生理指标均有显著影响(P<0.001),这意味着碳源种类和浓度的组合对这些生理指标的影响不仅是单独作用的简单相加,而是具有复杂的相互作用。

3 讨论有机碳源对微藻生长的积极影响已得到广泛证实[1-2]。Li等[25]的研究表明,一定浓度的葡萄糖和蔗糖能促进葛仙米细胞的生长和分化。同样,Yu等[26]发现葡萄糖可以促进发状念珠藻的生长。葡萄糖对微藻生长的促进作用可能是因为其能更多地参与到微藻细胞的TCA和EMP循环中,从而为生长和发育提供更多能量[27]。理论上以1 mol葡萄糖为能源较乙酸会产生额外的26 mol ATP[5]。不同种类的有机碳源对微藻生长的影响可能会有显著差异。Endo等[28]发现了小球藻(Chlorella regularis)在40 mmol/L丙酮酸钠下生长停滞,并认为原因是丙酮酸钠导致的过高pH值。随着蓝藻对碳源的吸收,质子转移将引起培养基的碱化,而pH值的增加幅度则取决于所使用的碳源种类[29]。

本实验所设置的环境条件能够维持葛仙米正常的生长和代谢[19],且不会影响添加碳源的化学性质,因此不同处理组之间的差异主要由碳源的种类和浓度不同引起。本实验的数据显示,在添加葡萄糖和蔗糖的条件下,葛仙米表现出显著更高的RGR。这说明葡萄糖和蔗糖能提供更高的能量用于生长繁殖。此外,葡萄糖和蔗糖培养条件下葛仙米的可溶性糖含量也更高。我们推测葡萄糖和蔗糖作为构筑葛仙米胞外多糖的重要成分,能够支持葛仙米群落基质的形成[30-32],从而同时促进了葛仙米生长和可溶性糖的积累。相反,在丙酮酸钠和乙酸钠培养条件下葛仙米的RGR显著下降,这或许是葛仙米对这两种碳源的吸收导致培养液酸碱环境的失衡所致。

与其他碳源相比,0.01~0.2 mol·L-1丙酮酸钠使可溶性蛋白含量显著增加,这表明丙酮酸钠的添加对葛仙米的蛋白质合成具有促进作用。对另一种念珠藻属物种的研究也发现,丙酮酸钠能提高其可溶性蛋白含量,在12.2 mmol·L-1时达到最大值[33]。我们推测丙酮酸钠被葛仙米吸收后被同化为乙酰辅酶A,然后参与TCA循环,通过提供能量和前体物质的方式促进蛋白质生成的新陈代谢活动,其他有机碳源则难以参与该过程[34-35]。

蓝藻在藻蓝蛋白的商业生产中发挥着重要作用[36]。已有研究证明适当添加外源有机碳源可以显著提高蓝藻中藻蓝蛋白的积累[9]。例如,在钝顶螺旋藻(Spirulina platensis)的培养过程中,添加4.0 g·L-1的醋酸能够将藻蓝蛋白的含量从110 mg·g-1提升至137 mg·g-1[37]。类似的结果也在鱼腥藻(Pseudanabaena mucicola)中观察到,添加乙酸钠使其藻蓝蛋白含量增加了20 mg·L-1以上[38]。在本研究中,0.2 mol·L-1的乙酸钠是葛仙米藻蓝蛋白积累的最佳碳源条件。作为蓝藻中的关键色素蛋白,藻蓝蛋白的含量影响着光合系统的光捕获能力,并参与电子的迁移过程[39-40]。我们推测藻蓝蛋白含量升高与低浓度乙酸钠促进光系统反应中心能量捕获和传递有关,其具体机理仍待进一步研究[41]。然而添加0.4 mol·L-1的乙酸钠反而会显著降低葛仙米的藻蓝蛋白含量。高浓度的乙酸钠会导致藻细胞内环境的酸化,影响细胞的正常代谢功能和光合作用过程。这种环境抑制藻蓝蛋白的合成,并加速其降解,从而导致藻蓝蛋白含量的显著下降。以前的研究结果也有类似情况,Chen等[37]发现添加过量乙酸钠会损害光合系统,从而降低钝顶螺旋藻的藻蓝蛋白含量。

碳源种类和浓度之间存在显著的交互作用,意味着它们的影响并非简单的线性相加。这可能反映了不同碳源在不同浓度下通过调控代谢途径或信号转导机制产生了协同或拮抗作用[18]。例如,在本实验中,添加0.4 mol·L-1乙酸钠的葛仙米,其可溶性蛋白含量反而低于添加0.2 mol·L-1乙酸钠的组,这说明高浓度的某些碳源可能会对细胞代谢产生抑制效应,而在低浓度时表现出促进作用。综上所述,本研究揭示了有机碳源种类和浓度对葛仙米的生长和生化组成有显著影响。葡萄糖和蔗糖明显促进了生长,尤其是在0.2 mol·L-1的蔗糖浓度下。同时,添加葡萄糖和蔗糖刺激了可溶性糖的积累,其含量随着碳源浓度的增加而增加。此外,可溶性蛋白含量和藻蓝蛋白含量的最大值分别在0.1和0.2 mol·L-1的乙酸钠浓度下获得。中国科学院水生生物研究所已经成功地实现了葛仙米室内培养,规模可达5 000 L,月均产量为180.9 kg(鲜质量)[42]。根据本研究的结果,添加0.2 mol·L-1的蔗糖可使葛仙米生长率提升96%。考虑到成本因素,也可添加较低浓度的蔗糖或葡萄糖,同样能显著促进葛仙米生长。目前葛仙米的鲜质量价格已达到192元·kg-1,而有机碳源价格相对较低(如食品级葡萄糖价格为2.4元·kg-1),故进行有机碳源的添加从而增加葛仙米的人工培育量具有较大的经济价值。综上所述,本研究在碳源添加方面为葛仙米的人工培养提供了重要的数据支持,进而为其自然资源的恢复提供可行方法。

| [1] |

Barbosa M J, Rocha J M S, Tramper J, et al. Acetate as a carbon source for hydrogen production by photosynthetic bacteria[J]. Journal of Biotechnology, 2001, 85(1): 25-33. DOI:10.1016/S0168-1656(00)00368-0 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Cottas A G, Teixeira T A, Cunha W R, et al. Effect of glucose and sodium nitrate on the cultivation of Nostoc sp. PCC 7423 and production of phycobiliproteins[J]. Brazilian Journal of Chemical Engineering, 2022, 39(1): 1-9. DOI:10.1007/s43153-021-00186-3 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Jones S E, Newton R J, McMahon K D. Evidence for structuring of bacterial community composition by organic carbon source in temperate lakes[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2009, 11(9): 2463-2472. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01977.x (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Fu X, Hou R, Yang P, et al. Application of external carbon source in heterotrophic denitrification of domestic sewage: A review[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2022, 817: 153061. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153061 (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Bouarab L, Dauta A, Loudiki M. Heterotrophic and mixotrophic growth of Micractinium pusillum Fresenius in the presence of acetate and glucose: Effect of light and acetate gradient concentration[J]. Water Research, 2004, 38(11): 2706-2712. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2004.03.021 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Lin T S, Wu J Y. Effect of carbon sources on growth and lipid accumulation of newly isolated microalgae cultured under mixotrophic condition[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2015, 184: 100-107. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2014.11.005 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Yu H. Effect of mixed carbon substrate on exopolysaccharide production of cyanobacterium Nostoc flagelliforme in mixotrophic cultures[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2012, 24: 669-673. (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Sharma L, Mallick N. Accumulation of poly-β-hydroxybutyrate in Nostoc muscorum: Regulation by pH, light-dark cycles, N and P status and carbon sources[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2005, 96(11): 1304-1310. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2004.10.009 (  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Kovac D, Babic O, Milovanovic I, et al. The production of biomass and phycobiliprotein pigments in filamentous cyanobacteria: The impact of light and carbon sources[J]. Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology, 2017, 53: 539-545. DOI:10.1134/S000368381705009X (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

Zhu S, Xu J, Adhikari B, et al. Nostoc sphaeroides Cyanobacteria: A review of its nutritional characteristics and processing technologies[J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2022, 63(27): 8975-8991. (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

Qin H, Lu J, Wang Z, et al. The influence of soil and water physicochemical properties on the distribution of Nostoc sphaeroides (Cyanophyceae) in paddy fields and biochemical comparison with indoor cultured biomass[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2013, 25: 1737-1745. (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Chen Z, Li W Z, Chen J Y, et al. Effects of calcium ion on the colony formation, growth, and photosynthesis in the edible cyanobacterium Nostoc sphaeroides[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2021, 33: 1409-1417. (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Guo M, Ding G B, Guo S, et al. Isolation and antitumor efficacy evaluation of a polysaccharide from Nostoc commune Vauch[J]. Food & Function, 2015, 6(9): 3035-3044. (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Dai G, Deblois CP, Liu S, et al. Differential sensitivity of five cyanobacterial strains to ammonium toxicity and its inhibitory mechanism on the photosynthesis of rice-field cyanobacterium Ge-Xian-Mi (Nostoc)[J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2008, 89(2): 113-121. DOI:10.1016/j.aquatox.2008.06.007 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Xia J. Response of growth, photosynthesis and photoinhibition of the edible cyanobacterium Nostoc sphaeroides colonies to thiobencarb herbicide[J]. Chemosphere, 2005, 59(4): 561-566. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.12.014 (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Chen Z, Juneau P, Qiu B, et al. Effects of three pesticides on the growth, photosynthesis and photoinhibition of the edible cyanobacterium Ge-Xian-Mi (Nostoc)[J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2007, 81(3): 256-265. DOI:10.1016/j.aquatox.2006.12.008 (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

汪丰海. 不同磷浓度对葛仙米生长的影响及葛仙米在室外大型生物反应器中的培养研究[D]. 武汉: 湖北工业大学, 2015. Wang F H. Effects of Different Phosphorus Concentrations on the Growth of Nostoc sphaeroides and the Outdoor Cultivation of Nostoc sphaeroides in the Lage Bioreactors[D]. Wuhan: Hubei University of Technology, 2015. (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

邱昌恩, 王卫东. 外加氮源对葛仙米生长及光合生理的影响[J]. 微生物学杂志, 2013, 33(2): 28-32. Qiu C E, Wang W D. Effects of additional nitrogen on Nostoc sphaeroids's growth & photosynthesis physiology[J]. Journal of Microbiology, 2013, 33(2): 28-32. (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

刘树文, 时功平. 不同形式无机碳对葛仙米的生理影响[J]. 江苏农业科学, 2018, 46(3): 166-169. Liu S W, Shi G P. Physiological effects of different forms of inorganic carbon on Nostoc sphaeroides[J]. Jiangsu Agricultural Sciences, 2018, 46(3): 166-169. (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Stanier R Y, Kunisawa R, Mandel M, et al. Purification and properties of unicellular blue-green algae (order Chroococcales)[J]. Biological Reviews, 1971, 35(2): 171-205. (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

李合生. 植物生理生化实验原理和技术[M]. 北京: 高等教育出版社, 2000: 135-137. Li H S. Principles and Techniques of Plant Physiological and Biochemical Experiments[M]. Beijing: Higher Education Press, 2000: 135-137. (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Morse E E. Anthrone in estimating low concentrations of sucrose[J]. Analytical Chemistry, 1947, 19(12): 1012-1013. DOI:10.1021/ac60012a021 (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding[J]. Analytical Biochemistry, 1976, 72(1-2): 248-254. DOI:10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 (  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Whitton B A. Handbook of phycological methods: Physiological and biochemical methods[J]. Phycologia, 1979, 18(4): 439-440. (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Li D H, Chen L Z, Li G B, et al. Photoregulated or energy dependent process of hormogonia differentiation in Nostoc sphaeroides Kützing (Cyanobacterium)[J]. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 2005, 47(6): 709-716. DOI:10.1111/j.1744-7909.2005.00097.x (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Yu H, Jia S, Dai Y. Growth characteristics of the cyanobacterium Nostoc flagelliforme in photoautotrophic, mixotrophic and heterotrophic cultivation[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2009, 21: 127-133. (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Joun J, Sirohi R, Sim S J. The effects of acetate and glucose on carbon fixation and carbon utilization in mixotrophy of Haematococcus pluvialis[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2023, 367: 128218. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2022.128218 (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Endo H, Sansawa H, Nakajima K. Studies on Chlorella regularis, heterotrophic fast-growing strain Ⅱ. Mixotrophic growth in relation to light intensity and acetate concentration[J]. Plant and Cell Physiology, 1997, 18: 199-205. (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Francisco E C, Franco T T, Wagner R, et al. Assessment of different carbohydrates as exogenous carbon source in cultivation of cyanobacteria[J]. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering, 2014, 37: 1497-1505. DOI:10.1007/s00449-013-1121-1 (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Ding Z, Jia S, Han P, et al. Effects of carbon sources on growth and extracellular polysaccharide production of Nostoc flagelliforme under heterotrophic high-cell-density fed-batch cultures[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2013, 25: 1017-1021. (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Zhong G, Pan W, Huang Z, et al. Physicochemical and geroprotective comparison of Nostoc sphaeroides polysaccharides across colony growth stages and with derived oligosaccharides[J]. Journal of Applied Physiology, 2021, 33: 939-952. (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Shi H, Zhang M, Yi S. Effects of ultrasonic impregnation pretreatment on drying characteristics of Nostoc sphaeroides Kützing[J]. Drying Technology, 2020, 38(8): 1051-1061. DOI:10.1080/07373937.2019.1611596 (  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Alvarez X, Alves A, Ribeiro M P, et al. Biochemical characterization of Nostoc sp. exopolysaccharides and evaluation of potential use in wound healing[J]. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2021, 254: 117303. (  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Xiong W, Lee T C, Rommelfanger S, et al. Phosphoketolase pathway contributes to carbon metabolism in cyanobacteria[J]. Nature Plants, 2015, 2(1): 1-8. (  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Zhang C C, Zhou C Z, Burnap R L, et al. Carbon/nitrogen metabolic balance: lessons from cyanobacteria[J]. Trends in Plant Science, 2018, 23(12): 1116-1130. (  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Fernandes R, Campos J, Serra M, et al. Exploring the benefits of phycocyanin: from Spirulina cultivation to its widespread applications[J]. Pharmaceuticals, 2023, 16(4): 592. (  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Chen T, Zheng W, Yang F, et al. Mixotrophic culture of high selenium-enriched Spirulina platensis on acetate and the enhanced production of photosynthetic pigments[J]. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 2006, 39(1): 103-107. (  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Kim S M, Bae E H, Kim J Y, et al. Mixotrophic cultivation of a native cyanobacterium, Pseudanabaena mucicola GO0704, to produce phycobiliprotein and biodiesel[J]. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2022, 32(10): 1325. (  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Vrek R Ö, Tarhan L. The relationship between the antioxidant system and phycocyanin production in Spirulina maxima with respect to nitrate concentration[J]. Turkish Journal of Botany, 2012, 36(4): 369-377. (  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Singh N K, Sonani R R, Rastogi R P, et al. The phycobilisomes: an early requisite for efficient photosynthesis in cyanobacteria[J]. EXCLI Journal, 2015, 14: 268. (  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Cheng J, Fan W X, Zheng L G. Development of a mixotrophic cultivation strategy for simultaneous improvement of biomass and photosynthetic efficiency in freshwater microalga Scenedesmus obliquus by adding appropriate concentration of sodium acetate[J]. Biochemical Engineering Journal, 2021, 176: 108177. (  0) 0) |

| [42] |

邓中洋, 况琪军, 胡征宇. 葛仙米室内规模化培养、群体显微结构及营养成分分析[J]. 武汉植物学研究, 2006(5): 481-484. Deng Z Y, Kuang Q J, Hu Z Y. Indoor large-scale cultivation, population microstructure and nutritional composition analysis of Nostoc sphaeroides[J]. Wuhan Botanical Research, 2006(5): 481-484. (  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 55

2025, Vol. 55