2. 青岛海洋科技中心海洋药物与生物制品功能实验室,山东 青岛 266237;

3. 中国海洋大学医药学院,山东 青岛 266003;

4. 坪山生物医药研发转化中心深圳湾实验室,广东 深圳 518118

虽然Z型核酸(ZNA)研究的历史较长,但直到最近其功能和机制才开始进行深入研究。早在1972年Pohl等[1]指出Poly(dGdC)n在高盐条件下可能呈左螺旋结构,依据是其圆二色性色谱与低盐浓度下的几乎相反。1979年Wang等[2]解析短回文序列5′-CGCGCG-3′的晶体结构时,意外发现是左旋双螺旋;并因其磷酸骨架呈Z字型(zig-zag)走向而将其命名为Z-DNA[2-3]。1981年Lafer等[4]用可在生理条件下稳定存在的Z-DNA(溴化45%的鸟嘌呤和20%的胞嘧啶)免疫小鼠和兔子获得了特异性结合Z-DNA的抗体,并且发现系统性红斑狼疮患者的血清中含有Z-DNA结合抗体(Anti-Z-DNA antibody)。这些研究成果表明Z-DNA至少在动物体内是可以存在的。1984年Hall等[5]在研究高盐条件下Poly(rGrC)n的光学特性时观察到A-RNA向Z-RNA的结构转变,发现向Z-RNA转变比向Z-DNA转变需要更高的盐离子浓度。同年,Uesugi等[6]指出甲基化或溴代修饰的r(CGCG)可形成Z-RNA结构(类似于Z-DNA)。1990年Zarling等[7]利用Z-RNA抗体染色发现Z-RNA广泛存在于细胞质和核仁中。可见核酸可形成左旋双螺旋结构可能是核酸的本质特性之一。近几年,带有Zα结构域(结合Z-DNA或Z-RNA)的ADAR1蛋白和ZBP1蛋白的功能受到越来越多的关注,有关Z-RNA的研究引起了广泛兴趣。因此,包含Z-DNA和Z-RNA的Z型核酸的概念逐渐被大家普遍使用,而且科学家们开始深入探索两种Z型核酸的特性、功能及相互关系。

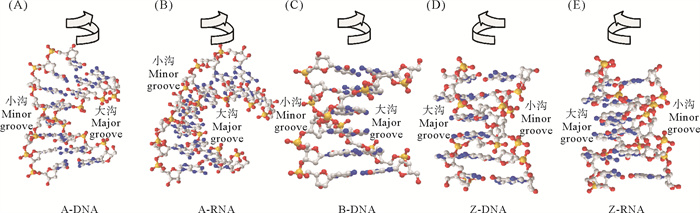

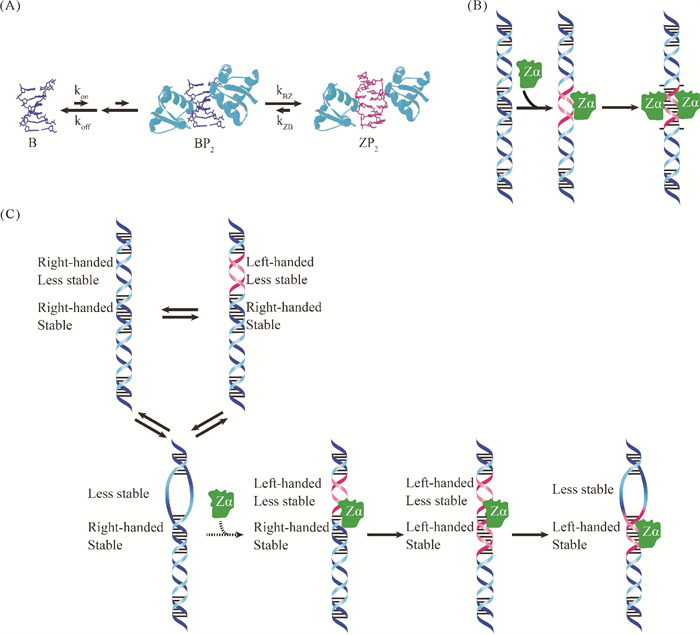

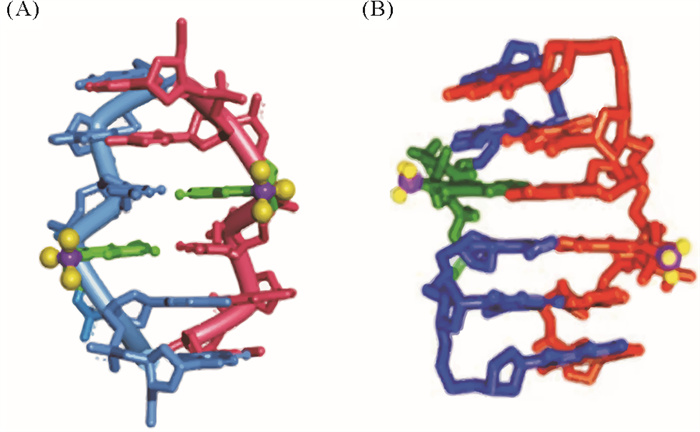

各种构型的双螺旋结构参数和特征如图 1和表 1所示[3, 8-10]。Z型核酸更加细长(螺旋直径1.8 nm,螺距约4.5 nm);磷酸骨架并非平滑延伸,而是呈锯齿状的Z字型;小沟窄而深,大沟很平坦;在大沟处碱基有很大一部分暴露在外(即堆积部分较小),被认为易于进行多种碱基修饰(如甲基化、氧化等)[11-12];糖苷键的构象为顺式(syn)和反式(anti)交替排列。相较于嘧啶糖苷键,嘌呤糖苷键更容易形成顺式构象,所以嘧啶-嘌呤交替排列的APP序列(Alternately arranged Pyrimidine-Purine sequence)更容易形成顺反交替结构,也就容易形成Z型[8]。Z-RNA和Z-DNA的结构很相似。2004年Popenda等[9]解析6 mol/L NaClO4条件下的Z-RNA(r(CGCGCG)2)结构,详细比较了这两种结构。Z-DNA每12 bp为一个螺旋单位,而Z-RNA是12.4 bp(见表 1)。Z-RNA的胞苷残基中的2′-OH深埋在小沟中,在Z-RNA的结构稳定中起着关键作用;鸟苷中的2′-OH则指向螺旋的外侧。在Z-RNA螺旋中,两个沟槽的差异变小,都能很清楚地观察到沟槽的轮廓(见图 1)。值得注意的是,DNA可呈现A、B和Z三种构型,而RNA却很难形成B-构型。这些结构差异如何让Z型核酸发挥独特功能呢?

|

( 其中A-DNA(A)、A-RNA(B)和B-DNA(C)都为右螺旋结构[8],Z-DNA(D)和Z-RNA(E)都为左螺旋结构[9],灰、蓝、黄和红色分别为C、N、P和O原子。A-DNA (A), A-RNA (B) and B-DNA (C) are right-helical structures[8], and Z-DNA (D) and Z-RNA (E) are left-helical structures[9], with gray, blue, yellow and red balls show C, N, P and O atoms. ) 图 1 核酸二级结构图 Fig. 1 Diagrams of several nucleic acid secondary structures |

近年来,研究者开始深入研究Z型核酸的一些生物学功能,如参与基因调控、诱发遗传不稳定性、稳定微生物的生物膜结构、诱发机体自身免疫疾病和癌症等[13-20]。与Z型核酸密切相关的特异性结合蛋白被发现参与机体的免疫应激、抗病毒等过程。这些生物学功能使人们相信Z型核酸在生物体内必然具有重要的生物学意义并能用于开发相应的药物[21-22]。本文主要总结2017年至今Z型核酸功能、形成条件、人工制备及检测方法等相关研究的最新进展并展望其发展趋势。

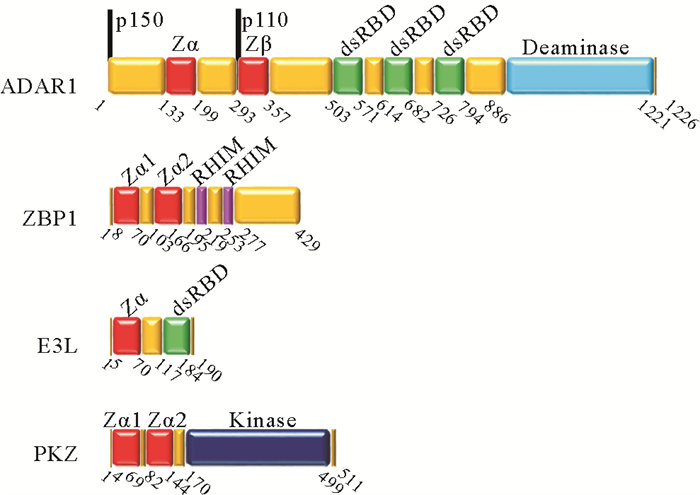

1 Z型核酸功能研究进展由于Z型核酸只有在拓扑限制、修饰及其他分子作用下才能稳定存在,一般只能通过研究相应的特异性结合蛋白的功能来推测其生物学功能。一般此类蛋白既结合Z-DNA又结合Z-RNA,并且这种相互作用只具有结构特异性而无序列特异性,因此本文统一称其为Z型核酸结合蛋白。它们都含有能特异性结合Z型核酸的、氨基酸序列高度保守的Zα结构域。目前发现的Z型核酸结合蛋白有脊椎动物双链RNA的腺苷脱氨酶(Adenosine deaminase acting on RNA 1,ADAR1)[23-25]、哺乳动物Z型核酸结合蛋白1(Z-DNA binding protein 1,ZBP1/DLM-1)[26-27]、鱼类Z型核酸结合蛋白激酶(Protein kinase containing Z-DNA binding domain,PKZ)[28]、痘病毒E3L蛋白(Vaccinia virus E3L protein)[29]以及鲤科疱疹病毒ORF112蛋白(Cyprinid herpesvirus ORF112 protein)[30]等(见图 2)。

|

( ADAR1和ZBP1来源于人类,E3L来源于痘病毒,PKZ来源于鱼类。ADAR1 and ZBP1 are derived from human, E3L from vaccinia virus, and PKZ from fish. ) 图 2 Z型核酸结合蛋白的结构示意图[66-70] Fig. 2 Schematic illustration of the structures of ZNA binding proteins[66-70] |

Z型核酸结合蛋白功能的共同特征是参与免疫反应通路(ADAR1,ZBP1,PKZ)[31-37]或帮助病毒抑制该途径(E3L,ORF112)[30, 38-39]。ADAR1能编辑体内RNA双链(dsRNA)中的碱基,超过50%的腺嘌呤能被ADAR1编辑为次黄嘌呤[24]。ADAR1 p150亚基中的Zα结构域在机体免疫应答中发挥重要作用[40]。Zα结构域缺失或突变通常导致罕见的孟德尔遗传疾病,如Aicardi-Goutières综合征(AGS)[41]、对称性遗传性色素沉着症[42]。此外,在癌细胞中,Zα结构域功能缺失的ADAR1使干扰素反应失调,从而增强了癌细胞的免疫逃逸[43]。ADAR1和ZBP1靶向细胞质应激颗粒(SG)的过程是通过Zα结构域完成[25]。ADAR1作为一种重要的核酸传感器已成为癌症及免疫治疗的重要靶点。

ZBP1已被证实在炎症细胞死亡(如皮肤炎症[44]、炎症性肠病[44-46]、牙周炎[47]、围产期致死[48]、急性肺损伤[27]、系统性红斑狼疮[49]、胆道闭锁肝纤维化[50])和抗病毒感染(如甲型流感病毒[51]、痘病毒[39]、乙型肝炎病毒[52])中起到关键作用。Banoth等[53]发现ZBP1可作为真菌感染的重要传感器抵抗白色念珠菌和烟曲霉菌诱导的PAN凋亡(PANoptosis)。PAN凋亡是一种促炎性程序性细胞死亡途径,同时具有细胞焦亡(Pyroptosis)、凋亡(Apoptosis)和坏死性凋亡(Necroptosis)的关键特征。当宿主被甲型流感病毒(IAV)感染时,ZBP1-RIPK3-MLKL通路(MLKL为程序性细胞坏死的最终效应器)被激活,导致程序性细胞坏死和炎症。相关证据如下:如Zα缺失则无法激活该通路[34, 54];Caspase-6(CASP6)与受体相互作用蛋白激酶3(RIPK3)结合能增强RIPK3和ZBP1之间的相互作用[55-56];ZBP1介导产生IL-1α使中性粒细胞胞外网络(NET)抵御IAV病毒[57];ZBP1被流感病毒激活后,还能诱导干扰素(IFN)和促炎细胞因子的产生,导致干扰素刺激基因(ISG)的表达、先天免疫细胞的募集或程序性细胞死亡的激活[58]。Mutoh等认为中风患者的脑梗塞部位周围的巨噬细胞能诱导ZBP1的增加,并且可能参与梗塞后大脑中mtDNA相关的神经炎症的发生[59]。因为引发炎症和组织损伤的MLKL和ZBP1主要在M1巨噬细胞中表达,所以M1巨噬细胞比M0和M2亚型的巨噬细胞更容易发生坏死性凋亡[60-61]。Nassour等[62]证明功能失调的端粒通过线粒体TERRA-ZBP1复合物激活先天免疫反应,以消除肿瘤转化的细胞。Guo等[63]发现沉默ZBP1可抑制阿尔茨海默病(AD)神经元的细胞损伤和焦亡,并通过抑制干扰素调节因子3(IRF3)改善AD大鼠的认知功能。

ZBP1在诱导细胞坏死中起着关键作用,有趣的是同样有Zα结构域的牛痘E3L蛋白能抑制ZBP1的这一作用。E3L蛋白赋予了痘病毒的干扰素抗性,在病毒感染过程中辅助其避开宿主的干扰素系统,从而感染宿主细胞。因此,以突变或缺失E3L的痘病毒作为疫苗或有效阻断E3L功能的化合物都是广谱的防治痘病毒感染的有效方法[29]。鱼类PKZ蛋白通过磷酸化elF2α保护鱼细胞免受病毒感染,并作为细胞质DNA传感器,其Zα结构域与Z-DNA结合激活鱼类先天免疫反应[22, 64]。RNA结合蛋白RBP7910也含Z型核酸结合域,优先与富含Poly U和AU重复序列的RNA分子相互作用,并参与调控线粒体的RNA编辑[65]。

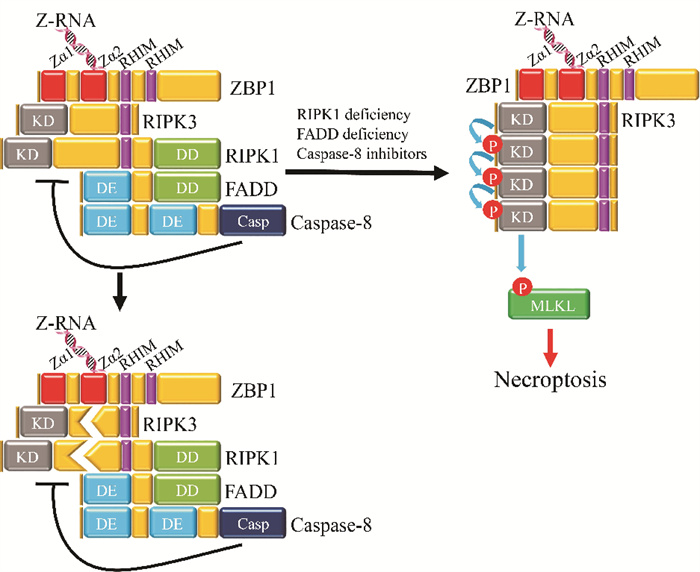

虽然Zα结构域发挥生物学功能得到了广泛确认,但Z型核酸如何进行免疫调控直到近几年才被初步证明,即Z型核酸激活ZBP1-RIPK3-MLKL通路的发现。ZBP1的N端含有2个结合Z型核酸的结构域(Zαl和Zα2),2个RHIM结构域(RHIM-A和RHIM-B)以及一个特征不明显的C端区域[71]。2016年Thapa等[51]首次发现甲流病毒(IAV)之所以引起RIPK3介导的坏死性凋亡,是因为ZBP1的Zα2结构域感应到病毒产生的双链RNA从而激活RIPK3。我们推测,与Zα2结构域结合的dsRNA应为Z型。2020年Zhang等[34]用特异性识别Z-RNA的抗体证实了Z-RNA激活ZBP1-RIPK3-MLKL通路导致程序性细胞坏死和炎症,并揭示了流感病毒是怎样一步一步诱导宿主细胞的程序性坏死的(见图 3)。ZBP1蛋白主要分布于细胞质中,但当细胞被感染后,ZBP1蛋白会迅速转移至细胞核与Z-RNA结合,并激活RIPK3蛋白;活化的RIPK3蛋白激活MLKL,导致核膜破裂、DNA泄漏到细胞液中,最终导致坏死[34]。除IAV病毒外,SARS家族冠状病毒的结构蛋白13(Nsp13)也可能调控Z-RNA介导ZBP1-RIPK3-MLKL坏死性凋亡途径,其中Z-RNA来源于冠状病毒中的Z倾向序列(Z-prone sequence)[72]。研究者提出Nsp13可能通过两种不同的机制下调Z-RNA介导的先天免疫反应:一是因Nsp13有不依赖ATP的Z型翻转酶(Z-flipon helicase)活性,它能阻止Z-RNA的形成;另一种可能是通过靶向ZBP1、RIPK1和RIPK3的RHIM结构域来抑制它们之间的相互作用[72]。Li等[73]发现SARS-CoV-2感染导致受感染细胞中形成病毒的Z-RNA,从而激活ZBP1-RIPK3通路,即在SARS-CoV-2引起的炎症反应和肺损伤中发挥着关键作用。目前产生Z-RNA的病毒都是在宿主细胞的细胞核中进行复制,而在细胞质中复制的病毒感染时则没有检测到Z-RNA或激活的ZBP1[34-36]。

|

图 3 流感病毒的Z-RNA激活ZBP1介导的RIPK3-MLKL依赖性坏死性凋亡示意图[34] Fig. 3 Schematic depiction for the ZBP1-mediated RIPK3-MLKL-dependent necroptosis activated by influenza virus Z-RNA[34] |

从上面的介绍可以看出,感染的病毒基因可产生Z型核酸,如遗传物质为负链RNA的流感病毒IAV[34, 51]、遗传物质为DNA的小鼠巨细胞病毒MCMV[71, 74-75]。但无病毒感染的情况下Z型核酸的形成是否可介导坏死性凋亡呢?2017年,Maelfait等[74]发现ZBP1能通过结合MCMV病毒产生的Z-RNA诱发免疫反应;他们还发现在无病毒感染时,ZBP1能与内源性RNA相互作用,并在Caspase-8(CASP8)活性受损时引发坏死性凋亡。2020年,发表于《Nature》期刊的两篇论文进一步报道了内源性Z-RNA在ZBP1免疫通路中的重要作用。Jiao等[44]和Wang等[45]发现一些自身免疫疾病(如慢性肠道炎症)与ZBP1密切相关,并证实ZBP1感应内源性Z-RNA(来源于内源性逆转录病毒元件ERV),触发ZBP1-RIPK3-MLKL通路导致坏死和炎症(见图 4)。Jiao等[44]还发现RIPK1和Caspase-8的负调控作用会抑制坏死性凋亡,当RIPK1或Caspase-8表达受抑制时(如RIPK1缺陷、或FADD缺陷、或用Caspase抑制剂处理),Zα依赖的内源性Z-RNA感知能激活ZBP1,从而触发MLKL依赖的坏死性凋亡。

|

( 内源性细胞Z-RNA结合Zα并激活ZBP1,ZBP1则与RIPK3结合进一步触发MLKL依赖的坏死性凋亡;但RIPK1和Caspase-8的负调控抑制了这一过程。The sensing of endogenous cellular Z-RNA by Zα domains activates ZBP1, inducing its interaction with RIPK3, and triggering MLKL-dependent necroptosis; however, cell death is inhibited owing to negative regulation by RIPK1 and caspase-8. ) 图 4 内源性Z-RNA激活ZBP1介导的RIPK3-MLKL依赖性坏死性凋亡示意图[44] Fig. 4 Schematic depiction for the regulation of ZBP1-mediated activation of RIPK3-MLKL-dependent necroptosis by endogenous Z-RNA[44] |

不只是Z-RNA,生物体内的Z-DNA也能激活ZBP1。有多项研究指出部分线粒体DNA(mtDNA)形成的Z-DNA能激活ZBP1的表达(存在于细胞质中),继而诱导坏死性凋亡[59, 76-78]。Baik等[76]发现,肿瘤细胞中葡萄糖缺乏能导致mtDNA释放到细胞质,mtDNA与ZBP1结合从而激活MLKL,引起肿瘤细胞坏死。这说明ZBP1是肿瘤坏死性凋亡的关键调节因子,并为控制肿瘤转移提供了一个潜在的药物靶点。Saada等[77]发现,视网膜色素上皮细胞(RPE)的mtDNA特异性氧化损伤后,受损的mtDNA转位到细胞质中通过激活ZBP1触发促炎因子的表达,从而引起青光眼和老年性黄斑病变等眼部疾病。Chen等[79]指出,5-氟尿嘧啶(5-FU)能促进mtDNA的胞质释放并通过ZBP1传感激活RIPK3,诱导坏死性凋亡。有趣的是,mtDNA激活的ZBP1不一定通过ZBP1-RIPK3-MLKL通路诱导坏死性凋亡。例如Lei等[78]发现,ZBP1和环状GMP-AMP合酶(cGAS)的相互作用表明mtDNA应激过程产生的Z-DNA与I型干扰素(IFN-I)信号传导及心脏损伤密切相关。ZBP1在稳定Z-DNA中起到关键作用,并且ZBP1-cGAS复合物与RIPK1和RIPK3一起参与维持IFN-I信号传导;同时,ZBP1还能抑制mtDNA与Toll样受体9(TLR9)之间的相互作用,并减轻mtDNA通过RIPK3-NF-κB-NLRP3途径诱导的炎症症状(见图 5)[78, 80]。ZBP1是mtDNA应激诱导IFN-I所必需的物质(在信号级联反应中充当关键介质),导致免疫反应的关键参与者IFN-I的产生[80]。种种迹象表明,ZBP1起到了捕捉和传递信号的警戒作用,无论是外来的和内在的,DNA的还是RNA的。

|

( 线粒体应激使其中的DNA(mtDNA)被释放到细胞质中,cGAS感应mtDNA并触发STING-NF-κB/IRF3激活干扰素信号。结合了mt-Z-DNA的ZBP1与cGAS、RIPK1和RIPK3形成复合物,参与I型干扰素信号传导,促进心脏疾病的发生。另一方面,ZBP1能抑制mtDNA与Toll样受体9(TLR9)之间的相互作用,并减轻mtDNA通过RIPK3-NF-κB-NLRP3途径诱导的炎症症状。Mitochondrial stress causes mtDNA to be released into the cytoplasm, then cGAS senses the mtDNA and triggers a STING-NF-κB/IRF3 to activate interferon signaling. After binding to mt-Z-DNA, ZBP1 forms complex with cGAS, RIPK1, and RIPK3 to engage in type I IFN signaling, contributing heart disease. In contrast, ZBP1 restrains the interaction between mtDNA and toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9), and attenuates mtDNA induced inflammation via the RIPK3-NF-κB-NLRP3 pathway. ) 图 5 mt-Z-DNA激活ZBP1介导的免疫反应示意图[78, 80] Fig. 5 Schematic diagramfor ZBP1-mediated immunoreaction activated by mt-Z-DNA[78, 80] |

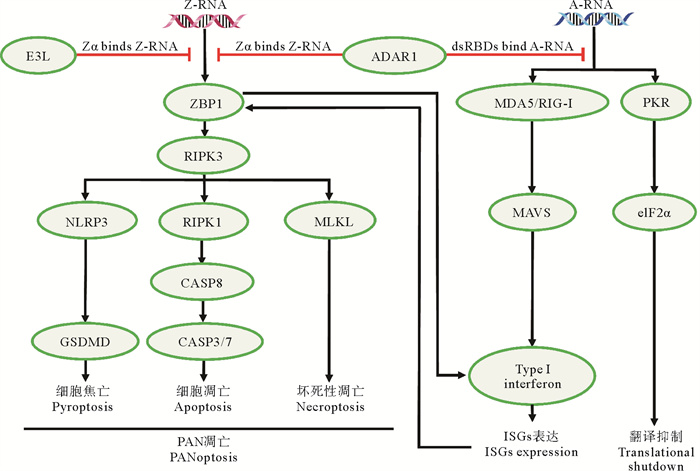

随着研究的不断深入,研究者发现Z型核酸参与免疫反应的其他途径[37, 81-97]。例如,ADAR1结合Z-RNA后通过RNA的特异性编辑,抑制黑色素瘤分化相关蛋白5(MDA5)介导的I型干扰素反应;ADAR1或E3L通过结合Z-RNA抑制ZBP1通路的激活(见图 6)。ADAR1催化RNA中腺嘌呤脱氨变为次黄嘌呤(A-to-I)后会降低dsRNA区域的稳定性;或使mRNA重新编码(因次黄嘌呤在翻译中会被识别为鸟嘌呤)[91-92]。在哺乳动物中,ADAR1由细胞核内的p110和细胞质中的p150两种亚型组成。其中p150有三个重要的结构域,即Zα(结合Z型核酸)、dsRBD(结合右手螺旋的A-RNA)和Deaminase(脱氨酶)[81]。一般认为,ADAR1的Zα和dsRBD结构域一起将酶定位到编辑底物上。Tang等[83]发现ADAR1对dsRNA进行编辑可阻止自发的线粒体抗病毒信号蛋白(MAVS)依赖性I型干扰素反应,表明Z-RNA在抑制MDA5激活中可能发挥重要作用。带有Zα结构域的p150(p110不带Zα结构域)介导的RNA编辑阻止MDA5的激活,从而抑制MDA5介导的炎症反应。如果ADAR1不与Z-RNA结合会导致dsRNA结构的A-to-I编辑减少[82]。Kim等[90]发现,小鼠大脑中微量的p150产生的少量RNA编辑(一条RNA链上只有几个位点)足以抑制MDA5的激活。Z-RNA的识别不当是Aicardi-Goutières综合征(AGS,一种I型干扰素病)发病的主要促成因素之一[41, 81, 84-89]。

|

( Z-RNA结合ZBP1并激活PAN凋亡,然而ADAR1和E3L能通过与ZBP1竞争Z-RNA来抑制Zα依赖的PAN凋亡;A-to-I编辑(dsRNA稳定性的降低)使MDA5等dsRNA传感器难以被激活,从而抑制此类蛋白引起的免疫反应,如I型干扰素的合成、干扰素刺激基因ISG的表达、翻译抑制;Z-RNA激活的ZBP1能调控I型干扰素的合成,而ADAR1能通过竞争Z-RNA抑制这一过程,当ADAR1对Z-RNA识别不当时,体内I型干扰素会过度激活表达造成炎症损伤,从而引起I型干扰素病。Z-RNA binds to ZBP1 and activates PANoptosis, while ADAR1 and E3L can inhibit Zα-dependent PANoptosis by competing with ZBP1 for Z-RNA. A-to-I editing (reduction of dsRNA stability) makes it difficult for dsRNA sensors (such as MDA5) to be activated, thereby inhibiting the immune response caused by such proteins, such as type I interferon synthesis, ISGs expression and translational shutdown; ZBP1 activated by Z-RNA can regulate the synthesis of type I interferon, while ADAR1 can inhibit this process by competing with Z-RNA. When ADAR1 does not recognize Z-RNA, the expression of type I interferon will be overexpression in vivo, and cause inflammatory injury, resulting in type I interferon disease. ) 图 6 ADAR1和E3L通过结合dsRNA抑制核酸受体的激活[70, 98-106] Fig. 6 Schematic diagramfor inhibiting activation of nucleic acid receptors of ADAR1 and E3L by binding to dsRNAs[70, 98-106] |

由于ADAR1结合Z-RNA后会抑制ZBP1通路的激活[91],ADAR1的缺失会让内源性Z-RNA活化ZBP1,并诱导ZBP1依赖的细胞程序性坏死[37, 82, 93-95]。ADAR1可以防止ZBP1引起的内源性Z-RNA依赖性激活I型IFN反应,反之ZBP1可能导致ADAR1突变引起的I型干扰素病[37]。ADAR1的Zα结构域也是防止ZBP1介导的肠道细胞死亡和皮肤炎症所必需的[94]。

ADAR1结合Z型核酸还能发挥其他功能,如Marshall等[96]发现DNA在左右螺旋结构之间切换越容易,大脑记忆就越具有可塑性,也就更有可能消除恐惧感。在前额叶皮层中,基因组采用Z型结构来响应恐惧;在消除恐惧时,ADAR1会与Z-DNA相结合并完成以下两个重要活动,即迅速增加RNA编辑并使Z-DNA翻转回B-DNA。Vögeli等[92]验证在IAV感染期间,ADAR1的p150亚型能阻止视黄酸诱导基因蛋白I(RIG-I)介导的IFN-β表达和凋亡。

与ADAR1类似,E3L结合Z-RNA也被发现能抑制ZBP1通路的激活。痘苗病毒(VACV)感染过程中产生的Z-RNA能触发ZBP1-RIPK3-MLKL依赖的坏死性凋亡,但病毒的E3L通过N端的Zα结构域竞争Z-RNA,从而阻止上述过程[39, 97]。

综上所述,由于多方证据表明Z型核酸结合蛋白同人体免疫和细胞死亡(包括凋亡、焦亡和坏死)等有关,其功能的重要性不言而喻。但因难以研究细胞内Z型核酸的形成过程以及这些蛋白对其形成的影响,Z型核酸发挥作用的本质和详细机制还远未搞清楚。可以预见,随着人工制备稳定Z型核酸技术的成熟以及相关检测分析技术的发展,Z型核酸研究必将成为新的热门领域。

2 生物体(细胞)内Z型核酸的形成机制如果没有外力的辅助,细胞内的核酸双螺旋结构都倾向于形成更为稳定的右螺旋(B-DNA或A-RNA)。因此,只有在让右螺旋难以形成而有利于左螺旋形成的条件下才能促进Z型核酸的形成。这些条件包括负超螺旋产生的拓扑应力、特异性结合蛋白(如ZBP1和ADAR1)的结合以及甲基化修饰等。在细胞中往往是上述两种或三种方式协同作用以诱导产生稳定的Z-DNA;而Z-RNA的形成一般只靠特异性结合蛋白的结合或某些修饰。另外,APP序列的存在使Z型核酸更易形成。我们认为细胞内的DNA含有APP序列的部分一直处于形成Z-DNA和超螺旋结构的平衡中,Z-DNA可理解为利用拓扑张力的转换器。一般Z-DNA存在时间相对很短,除非有其他因素的参与才能得以稳定。Z-RNA的形成机制还是未解之谜。

2.1 拓扑应力诱导Z-DNA的形成众所周知,负超螺旋(Negative supercoil)使dsDNA产生拓扑应力并倾向于部分解链,其中一种释放负超螺旋所产生应力的形式就是形成左旋的Z-DNA(见图 7)。质粒或细菌的环状基因组dsDNA是一个含有负超螺旋的连环,B-DNA的结构要求两条环状DNA链相互向右缠绕数百甚至数百万圈(平均10.4 bp/圈),形成类似环形双股绳的互锁结构。另一方面,含有数百万至上亿碱基对的任一条真核细胞染色体上的大部分线性基因组缠绕在核小体上。核小体脱落的部分(一般数百至数千碱基对)会形成两端固定的、与带有负超螺旋的环状dsDNA类似的拓扑结构(见图 7(A)和(B))。可见,无论是真核生物的线性dsDNA,还是环状dsDNA,负超螺旋都倾向于短暂形成一小段Z-DNA而不发生解链(见图 7(C))[107-110]。有证据表明,一段解链部分的存在确实有助于形成Z型核酸。Zheng等[107]在序列d(CG)6上引入1~6 nt未配对的单链区域,使hZαADAR1诱导的B-Z(或A-Z)转换率大大提高,且单链区域适当加长可进一步促进Z型的形成。其机制可能是降低了B-Z(或A-Z)跃迁的活化能。每形成一圈左螺旋能消耗约2个负超螺旋应力[111],这与dsDNA的结构特征一致(见表 1)。Kolimi等[112]发现A-A错配能诱导负超螺旋,并促进局部B-DNA到Z-DNA转换。

|

( 原核细胞(A)和真核细胞(B)的DNA解旋。Z-DNA的形成(C)。Unwinding of DNA in prokaryotic cells (A) and eukaryotic cells (B). Formation of Z-DNA(C). ) 图 7 染色体结构和DNA解旋状态之间的转化 Fig. 7 Transformation between chromosome structures and state of DNA unwinding |

有研究认为RNA在复制、转录等涉及核酸解旋的过程中,可能会像Z-DNA的形成一样,在拓扑应力的作用下,通过扭转和机械应力诱导Z-RNA形成[34, 72, 113-114]。Balachandran等[113]发现RNA病毒IAV能在宿主细胞核内产生Z-RNA,并认为是在病毒复制过程中由负超螺旋的扭转应力诱导产生。Herbert等[72]认为RNA病毒基因组中Z-prone序列除了作为密码子外,还可能充当容易改变结构的翻转子(Flipon)。例如,当基因组的正链和负链都被病毒聚合酶转录时,Z-RNA的形成可以减轻拓扑应力。但由于RNA一般都带有易于扭住的末端,很容易通过其他方式缓解拓扑应力,一般更需要特异性结合蛋白的参与。

2.2 Zα结构域诱导下Z型核酸的形成和稳定Z型核酸结合蛋白能与Z型结构特异性结合,一般受序列及溶液条件的影响较小[115-116]。这些结合蛋白一般含有Zα和Zβ两种结合Z型核酸的结构域,Zα能与Z型核酸形成稳定的复合物,而Zβ与Z型核酸相互作用较弱[111]。ZBP1中有Zα1和Zα2这2个Zα结构域,有研究指出体内Z-RNA能够结合Zα2[34]。ADAR1则有1个Zα和1个Zβ,Zβ结构域在结构上与Zα同源,通过1个连接子(95个残基)与Zα连接[68]。Zβ不单独与RNA结合,但包含Zα、Zβ和连接子(Zα-Zβ)的复合物与RNA的亲和力强于单独的Zα[117],但其详细功能目前尚不清楚[68]。Zα结构域高度保守,其结合区域内的氨基酸残基主要与Z型核酸的锯齿形糖-磷酸骨架相互作用,这有助于提高结合Z型核酸的结构特异性[118]。

越来越多的数据表明,细胞内Z-DNA和Z-RNA调控功能的发挥通常依赖于Z型核酸结合蛋白的辅助,即Z型核酸结合蛋白参与向Z型核酸的转变。Lee等[119]认为ZBP1蛋白通过多个序列识别步骤,选择性地识别CpG重复序列。首先第一个ZBP1分子与B-DNA结合,使得B-DNA的平衡向Z-DNA移动,随后第二个ZBP1分子进一步稳定Z型结构,结合后的复合物中最终将基因组长序列中的CpG重复序列转变为Z型(见图 8(A))[119]。通过提高B-DNA结合能力,能成功地将B-Z转换缺陷的Zα结构域vvZα(E3L)变为B-Z转换器,这表明B-DNA结合参与了B-Z转变。引入与Z-DNA相互作用氨基酸残基,能将一些B-DNA结合蛋白GH5设计成具有Z-DNA结合和B-Z转换活性的Zα样蛋白[120]。类似地,ADAR1的Zα结构域先识别d(GAC)7的B-Z Junction部分,随后通过所谓的被动机制将其转化为Z-DNA[112]。Lee等[121]认为ADAR1优先与DNA中的CG重复片段区域结合,然后在邻近的富含AT区域中使至少6个碱基对结构变化,以实现有效的B-Z转换。

|

( (A)由ZBP1诱导的Z-DNA,其中P代表结合蛋白,B表示B-DNA,Z表示Z-DNA;(B)由ADAR1诱导的Z-RNA;(C)Zα结构域诱导Z型核酸模型。(A) Z-DNA induced by ZBP1. P shows the binding protein, B shows B-DNA, and Z shows Z-DNA; (B) Z-RNA induced by ADAR1; (C) Z-form nucleic acid model induced by Zα domain. ) 图 8 由Zα结构域结合诱导的Z型核酸[119, 127] Fig. 8 The Z-form nucleic acid induced by binding of Zα domain[119, 127] |

多项研究表明Z-DNA和Z-RNA都可结合ADAR1的Zα结构域[122],形成热力学稳定的复合物。但ADAR1的Zα与Z-RNA的结合和解离速度比与Z-DNA结合慢(相差约30倍)[123-124],这可能与ADAR1本身的结合前后的结构变化有关[86]。ADAR1的Zα结构域所含三个α螺旋(α1、α2和α3)中的α3位于功能核心附近,被认为在转化为Z型螺旋的过程中起着重要作用[124-126]。在dsRNA转化为Z型的过程中,ADAR1上的Thr191的酰胺基团表现出明显的结构变化;而在DNA向Z型转变过程中变化不明显[124]。结合Zα的RNA序列特异性较低,结合后的复合物中RNA为Z-构型[30, 127]。影响Z型核酸形成的最大因素是Z型核酸翻转糖折叠的容易程度[128]。两侧存在不太稳定的RNA区域或受到扭转/机械应力,dsRNA都易于变为Z型[128]。Zα结构域与CpG重复序列的结合具有特异性、协同性和高亲和力[127]。Nichols等[127]提出了一个Zα结合dsRNA的机制模型:在dsRNA的Z-prone区域两侧是不太稳定的A-RNA区域(通常包括YpR序列和非Watson-Crick碱基对),首先Zα与之发生动态相互作用,先将该区域转换为Z型,同时破坏相邻区域的稳定性;这促进了另一个Zα的结合,使Z型结构稳定下来,并形成A-Z Junction(含外翻的碱基对)(见图 8(B))。

由于Z型核酸与右螺旋核酸的结构差异巨大,科学家们一直对上述蛋白能促进向Z型核酸的转化感到费解。表面上看好像是这些蛋白“主动”扭转右螺旋为左螺旋,但可能实际并非完全如此。另外一种观点认为,可能这些蛋白只是捕捉到了瞬间形成的Z型结构,稳定结合后防止其转变回右螺旋。即使很难产生拓扑应力的Z-RNA的形成可能也是先有左螺旋构型作为“抓手”,然后才能发生“扭转”。本文作者推测,在细胞内,含有错配的Loop(包括发卡结构的Loop和Internal Loop)可能易于形成Z型核酸,从而在Zα结构域作用下让旁边的富含Poly(rCrG)n的完全互补序列转变为左螺旋结构(见图 8(C))。具体机制如下:(1)错配处更易处于左螺旋和右螺旋构型的动态平衡中。可能有些错配序列更易形成Z型结构,且多价阳离子(如精胺等多胺化合物)可让其比右螺旋结构更稳定(或相差无几)。当有4个碱基对或6个碱基对(含错配)形成Z型结构时,Zα能够相对稳定地结合。如果有两个Zα结构域,它们可像双手那样握紧左螺旋。(2)形成的左螺旋-右螺旋结合区域让核酸结构处于较高的自由能状态,因此让邻近的互补区域更易转变为Z型结构,并被动态移动的Zα结构域“抓住”而得以稳定。(3)经过几次这样的动态结构变化后,富含Poly(rCrG)n的完全互补序列部分(6~8 bp)转化为Z型结构,且Zα结构域能稳定结合在该处。同时,邻近的错配部分恢复到原来的动态平衡中。(4)ADAR1的其他结构域(如Zβ结构域)同附近的dsRNA部分结合,进一步提高结合能力以防止Zα的解离(降低解离速度)。

Li等[129]构建了一种测定蛋白结合非修饰Z-DNA的亲和力的方法。结果发现,Z22除了与左螺旋DNA结合外还与B-Z Junction处稳定结合,且与后者有更强的亲和能力。ZBP1与Z22不同,它仅与左螺旋DNA部分结合。此外,Li等[129]还发现随着阳离子浓度的增加,Z22与B-Z Junction处的亲和力几乎不变,但与左螺旋DNA部分亲和力增强。这种方法可以很容易测定多种离子条件下Z22和ZBP1与左螺旋DNA的结合的动力学参数,排除了其他因素对于测定的干扰。

2.3 其他诱导Z型核酸形成的方式除上述方法外,生物体内还有其他改变核酸结构的方法。(1)ATP依赖性染色质重塑能调控向Z-DNA的转化。SWI/SNF复合物(一种高度保守的染色质重塑复合物),可通过其催化BRG1或BRM水解ATP重建染色质。Li等[130]证实了BRG1/BRM的表达量与Z-DNA的含量呈正相关,说明Z-DNA的形成可能参与SWI/SNF调控。(2)氧化应激。鸟嘌呤C8位置氧化后的8-oxo-7, 8-二氢鸟嘌呤(OG)可能使核酸形成Z-DNA,从而参与基因调控[131]。Yang等[132]发现氧化应激强烈诱导宿主细胞内源性Z-RNA,并被ZBP1识别而触发坏死性凋亡。但活性氧(ROS)促进Z-RNA形成的机制还不清楚,可能极具氧化活性的羟基自由基会氧化核酸产生自由基加合物,从而导致特定dsRNA处的结构改变[132]。(3)体内精胺诱导。Zhao等[133]发现内源性精胺和亚精胺减弱了cGAS活性和先天免疫反应。这可能是由于精胺和亚精胺诱导B-DNA向Z-DNA进行转变,从而降低其与cGAS的结合亲和力。但这些大多停留在讨论的层次,还缺乏明确的证据。(4)解旋酶诱导。Herbert[134]认为MDA5解旋酶能诱导Alu序列的RNA形成Z-构象。在ATP作用下,结合dsRNA的2个MDA5发生扭转且距离缩短。为抵抗这一应力,dsRNA的构象由A型变为Z型,同时ADAR1识别Z-RNA,通过编辑降低dsRNA稳定性,使MDA5脱离RNA。其他解旋酶也有可能调节Z-RNA、Z-DNA等结构的形成。

2.4 Z型核酸序列特异性最早发现的Z-DNA和Z-RNA是Poly(CG) 序列,特别是6 bp的回文序列CGCGCG研究得最多。根据解析的晶体结构,一般认为要形成Z型核酸必须是APP序列,且CG重复序列最易形成[1, 135-140]。有研究认为TG/CA重复序列(一种APP序列)转变为Z型相比CG重复序列自由能高很多,更容易产生解链(形成Bubble),较难形成Z-DNA。因此TG/CA重复序列可作为扭转缓冲器或Bubble选择器,所形成的Z-DNA更容易解链起始或调控基因的表达[135]。ZBP1结合CG重复序列可直接形成ZBP-Z-DNA复合物,而结合TG/CA重复序列在形成Z-DNA之前需有ZBP1先结合在B-DNA上[122]。由于在B-Z连接部(B-Z Junction)会发生一对碱基对外翻,造成自由能增加,一般A-T比G-C碱基对更容易外翻,且只产生连续的Z型核酸部分(减少B-Z连接部的个数)[141-142]。另外,B-Z连接部形成的能垒可能会随Z-DNA诱导条件的不同而变化[143]。近期发现A-A错配也可能会短暂生成局部B-Z连接部,ADAR1的Zα结构域先识别B-Z结合处,然后逐渐结合更稳定的Z-DNA序列[112, 144]。耐人寻味的是,G-G错配处会形成2种B-Z结合,即G交替外翻(对称的两个G只有一个外翻)和对称外翻(对称的两个G都外翻)[145]。

Z-RNA的A-Z结合部(A型右双螺旋和左螺旋的连接处)研究较少。由于一般是在RNA二级结构处形成Z-RNA,可以推断,错配处更易作为A-Z结合部。D′Ascenzo等[146]和Nichols等[127]指出Z-RNA在转录组中广泛分布,并认为Z-RNA形成的方式与Z-DNA不同。特别是RNA双链部分的泡(Bubble)和凸起(Bulge)降低了形成A-Z连接部的能量成本,因此G-T碱基对处也易实现翻转[23]。对于相同的序列,RNA的A-Z转变比DNA的B-Z转变需要更多的能量,表现在需要更高的盐浓度和更高的温度才能实现A-Z转变[5]。Z-RNA与Z-DNA中都有核糖-碱基相互作用。O4′与嘌呤碱基最远距离为3.5 Å,其中O4′与dG平均距离为2.9 Å,O4′与rG(或rA)平均距离为3.0 Å,两者相差不多。但在RNA中上述距离更分散,说明Z-RNA比Z-DNA更具有结构多样性[12]。

研究发现哺乳动物体内转座元件(TE)容易形成Z型核酸。转座元件(即转座子,Transposon)占哺乳动物基因组序列的50%左右,分为反转录转座子(Retrotransposon)和普通的DNA转座子(DNA transposon)两类。其中属于反转录转座子中SINE的Alu序列和ERV序列易形成内源性Z型核酸。Alu转录的RNA形成的dsRNA部分易被ADAR1的Zα结构域识别并编辑,从而阻止dsRNA的过度形成[83, 94, 127]。Alu序列作为一种Z型翻转子,能形成Z-DNA并影响其转录[147]。ZBP1也能识别Alu产生的Z-RNA触发ZBP1-RIPK3-MLKL通路引起坏死性凋亡[72, 94]。同样,ERV转录产生的dsRNA也能被Zα结构域识别[37, 44-45]。Zhang等[82]指出ADAR1的Zα结构域能识别干扰素刺激基因(ISG)的mRNA形成的Z-RNA;这些Z-RNA主要由3′端非编码区的SINE和富含GpA的重复序列产生。Nichols等[127]证明核糖体RNA的茎环结构和Alu序列中富含GpU和ApU处容易形成Z-RNA。

ADAR1除了通过编辑RNA,还可通过结合在Z-RNA上将其掩盖而不被其他Z-RNA受体(或者抗体)识别。对于病毒,潜在的Z-prone序列可以出现在病毒基因组的许多位置[72],如IAV病毒激活ZBP1的Z-RNA可能主要来源于DVG基因。在病毒复制过程中大量产生DVG的RNA有时会不恰当地组装导致最终无法形成正常的衣壳。这导致DVG RNA更易被宿主的先天防御机制感知[34]。Z-prone序列也可能出现在病毒基因组中更可变的区域,使病毒能够进化以适应宿主;或通过氨基酸改变改善蛋白质功能,或影响宿主翻译,如Alu重复元件的Z-Box(含有APP的序列)通过调节核糖体组装调控翻译[148]。

虽然目前研究的Z型核酸多为APP序列,Li等[149]用两个不含APP序列的互补的环状单链DNA杂交后同样得到了可结合Z22抗体或ZBP1的Z-DNA,而且可在接近生理离子条件下形成稳定的Z-DNA。与非APP序列相比,APP序列更容易形成Z-DNA是因为APP序列形成的Z-DNA的热稳定性更接近其B-DNA异构体。我们认为左螺旋DNA易在两种结构(左和右)自由能差更小的序列上形成,这样形成Z型结构时自由能损失最小。如果超螺旋的局部密度足够高,并且某种蛋白质通过与Z型结构的结合产生约束,就可形成相对稳定的左螺旋DNA。非APP序列通过形成左螺旋DNA可以暂时缓解转录引起的负超螺旋压力。这说明在一些特殊条件下,Z-DNA的形成不再受序列限制。如果没有相应的蛋白质结合,互补DNA的解链几乎不发生,因为解链状态比左螺旋DNA的自由能高很多。总之,在长的双链上,拓扑应力易于传递,一般是在APP序列处形成Z-DNA,只有在特殊情况下,非APP序列处短暂形成Z-DNA并发挥一定的功能。

3 人工制备稳定Z型核酸的方法 3.1 诱导剂结合稳定Z型核酸与B-DNA相比,Z-DNA结构中磷酸骨架上的氧负离子之间的距离更近,静电斥力更强。因此,可通过加入浓度足够高的阳离子(特别是多价阳离子)以使Z-DNA比B-DNA更稳定[150-152]。1972年,Pohl等[1]发现2.5 mol/L NaCl、1.8 mol/L NaClO4或0.7 mol/L MgCl2能诱导Poly(dCdG)n形成Z-DNA。Kominami等[153]对比不同结构DNA表面电子密度的差异,发现相对于B-DNA,Z-DNA双螺旋表面确实负电荷更少,表明阳离子结合得更牢固。二价或高价阳离子(如Mg2+[152]、La3+[151]、Ni2+等)的效果更显著。La3+离子嵌入DNA的大沟和小沟中,并与氧负离子在小沟表面形成配位键[151],5 mmol/L LaCl3能诱导d(CG)6向Z型转变[151]。另一镧系元素Pr3+也有相似功能,10 mmol/L PrCl3即可诱导这一转变[154]。Bhanjadeo等[155]证明了7.5 mmol/L CeCl3在生理浓度下可诱导B-Z转变。除了与磷酸基团发生静电相互作用,NMR结果显示,Ca2+、Cu2+等阳离子的水合离子还可与相邻G的O6、N7原子形成氢键,共同维持Z型结构的稳定性[156-157]。

显然,上述高盐条件与细胞内的环境相差甚远,虽然细胞内本来含有的精胺、腐胺和亚精胺等多胺也能起到类似作用[158],但除精子等少数细胞外,一般多胺的浓度较低。化学修饰能提高这些分子结合Z型核酸的能力,无需高盐浓度。Kawara等[158]制备了具有轴向手性的2, 13-二甲氧基[5]螺旋烯精胺配体(外消旋体),与B-DNA结合后,其P手性转变为M手性。另一方面,Cucurbit[7]uril(CB7)能竞争性结合精胺从而使Z-DNA转变为B-DNA[159]。为了获得尽可能接近生理状态的Z-DNA,研究者们还尝试借助一类具有刚性平面结构(如卟啉)的复合物来诱导Z-DNA形成[9]。Qin等分析了ZnTMPyP4(一种卟啉)与Z-DNA的结合模式,发现吡啶基与磷酸基骨架之间可形成静电相互作用,且锌(II)与主沟上的鸟嘌呤N7结合,两种相互作用共同维持了Z-DNA的稳定[160]。还有研究者利用卟啉与多胺正离子的协同作用,开发出了产生多种光谱响应的卟啉分子探针,可实时监测B-Z转变[161]。在用单精胺卟啉衍生物诱导小牛胸腺DNA(ct-DNA)的B-Z转变时,发现卟啉结合在双螺旋外部,且碱基间有卟啉的轻微嵌入[162]。Nayoung等指出,仅当卟啉嵌入碱基之间后沿着DNA骨架形成有效堆积作用时,才能诱发B-Z转变[163]。

一些溶剂或药物分子也能将B-DNA诱导为Z-DNA。研究表明Z-DNA在二甲基亚砜(DMSO)存在下结构趋于稳定[164]。因此,Tunçer等[164]怀疑DMSO对基因表达、分化和表观遗传改变的特定作用可能与其稳定Z-DNA结构有关。在细胞中,高生物分子浓度也可能诱导B-DNA向Z-DNA转变,如分子拥挤剂PEG200能影响Z-DNA的形成[165-166]。新型抗肿瘤药物Pd2Spm连接2个Pd,能使B-DNA向Z-DNA或A-DNA转变[167]。小分子抗癌候选药物Curaxin与细胞DNA结合还可导致核小体的破坏,导致基因组DNA的多个区域转化为Z-DNA[168]。Li等[169]发现Curaxin家族的CBL0137可以显著诱导HepG2细胞中Z-DNA的形成,推测CBL0137引起的肝细胞坏死性凋亡是由于Z-DNA和ZBP1的诱导,从而激活了RIPK1-RIPK3-MLKL通路。Zhang等[82]则利用这一点诱导细胞内形成Z-DNA,证明了ADAR1结合Z型核酸能阻止下游信号通路的激活。但CBL0137难以定点(在确定序列处)诱导Z-DNA的形成,对于Z型核酸发挥作用的细节难以判断。

3.2 碱基修饰形成稳定的Z型核酸顺反交替的碱基糖苷键构象使Z型核酸中具有一定疏水性的碱基的一部分(如胞嘧啶的C5和鸟嘌呤G的N7、C8)暴露在周围的水溶液中,也是其不稳定的因素之一。正如前文所述,如果修饰让B-DNA更难形成(如发生立体障碍)或提高暴露碱基的亲水性,就可能使Z型核酸在生理离子条件下稳定(见图 9)[170-173]。

|

( (A)8-三氟甲基-2′-脱氧鸟苷(FG)诱导Z-DNA;(B)2′-O-甲基-8-甲基鸟苷(m8Gm)诱导Z-RNA。(A) Induction of Z-DNA by FG; (B) Induction of Z-RNA by m8Gm. ) 图 9 修饰碱基诱导Z型核酸的形成[171, 173] Fig. 9 Formation of Z-form nucleic acid induced by introducing modified bases[171, 173] |

Balasubramaniyam等[172]制备了含有一个或多个2′-O-甲基-8-甲基鸟苷(m8Gm)的DNA寡核苷酸,表明d(CGCm8GmCG)2序列中只引入两个修饰碱基就可在20 mmol/L NaCl的条件下形成稳定的Z-DNA(Tm=39.4 ℃)。他们又在RNA中引入该修饰碱基,使r(CGCm8GmCG)2在880 mmol/L NaClO4的条件下形成稳定的Z-RNA[171]。如前所述,5-甲基胞嘧啶也能诱导Z-DNA形成。在200 μmol/L [Co(NH3)6]3+的条件下,d(m5CG)4呈Z型结构(未甲基化的d(CG)4为B型)[174],这些修饰DNA可用于Z型核酸结合蛋白的筛选[175]。相反,5-甲基胞嘧啶的氧化产物(5-羟甲基胞嘧啶,5-甲酰基胞嘧啶和5-羧基胞嘧啶)都阻碍B-Z转变[176]。含有8-三氟甲基-2′-脱氧鸟苷(FG)的DNA也能在生理盐浓度下稳定Z-DNA结构,并可通过测定19F NMR直接观察Z-DNA结构及其与蛋白质的相互作用,甚至可在人体细胞中直接观测[173, 177]。虽然体内的天然碱基修饰(如OG:8-oxo-7, 8-二氢鸟嘌呤)能诱导Z型核酸的形成,但很难在细胞内在特定序列处进行人工修饰[131]。

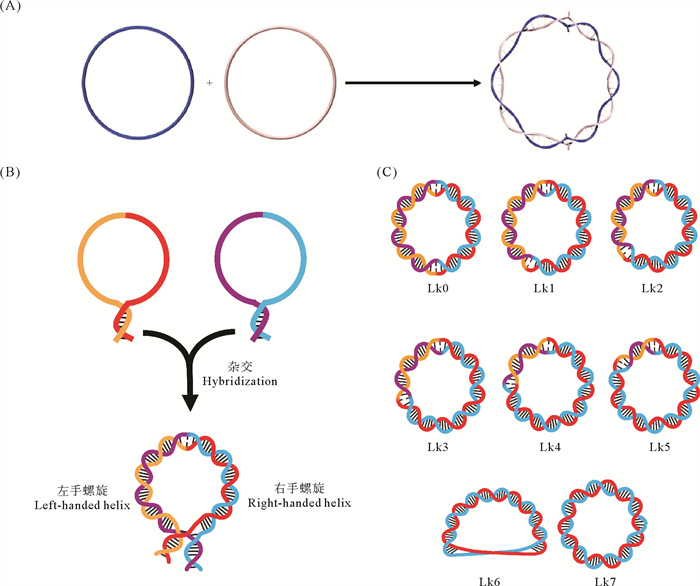

3.3 拓扑限制法生成稳定Z型核酸上述形成的Z型核酸或远离细胞内的环境条件、或进行了非天然的修饰、或结合上了非天然的人工分子,难以反映生物体内非修饰Z型核酸的真实状态。通过在含数千碱基对的质粒中引入高密度的负超螺旋和Poly(dCdG)n序列,可在该序列处形成稳定的Z-DNA[112, 131]。但过高的负超螺旋密度(如>8%)与实际条件不符,特别是导入细胞后拓扑异构酶会调节负超螺旋到一定的密度。20世纪80年代初,Sterttler等[178]通过严格控制DNase I的切割程度,让每个质粒上只随机产生一个切口(Nick),用外切酶去除这条含Nick的DNA链以后得到单链环状DNA(正义链和反义链的数量基本相同)。这两条混在一起的单链环状DNA会通过杂交形成Lk值(Linking number)为0的双链环状DNA(被定义为Form V DNA),即向右缠绕的圈数和向左缠绕的圈数相同。CD和抗体结合实验表明Form V DNA中含有Z-DNA[179-180]。显然,这样得到的Z-DNA都由天然非修饰DNA构成,而且能在生理条件下稳定存在。但Form V DNA制备过程难以控制,而且长度一般在2 kb以上,会形成密度很高的负超螺旋,Z-DNA的位置和长度也难以确定。因此,Form V DNA的应用受到了极大限制。

2019年,Zhang等[181]开发了一种使用短的(60~120 nt)互补的两条单链DNA环杂交制备稳定Z-DNA(LR嵌合体)的方法。具体过程如下:分别制备两条单链环状DNA,然后在所需缓冲溶液条件下进行杂交,即可得到能在生理条件(甚至更低的盐浓度)下稳定存在的Z-DNA(见图 10(A))[181]。这种制备方法操作简单,无需外加物的诱导和碱基修饰,可方便设计各种序列,且Z-DNA位置更明确,这有望为Z-DNA相关研究提供丰富可靠的原料及标准样品。该方法已被成功用于研究Z-DNA稳定性[149, 182]、Z-DNA与蛋白的亲和力测定[129]、生物体内锌指蛋白重塑Z-DNA[183]和mt-Z-DNA激活ZBP1并参与IFN-I信号传导的过程[78]。显然,这一重大突破有望广泛用于Z型核酸相关的基础研究和药物开发等。利用该方法,Li等[149]还发现非APP序列可以在接近生理条件的离子强度下形成Z-DNA的结构,并成功构建了一种评价体内蛋白(ZBP1和Z22抗体)与非修饰Z型核酸结合的方法,还评价了多种离子条件下它们的亲和能力[129]。利用同样的原理,刘梦琴[184]成功制备了生理条件下稳定存在的Z-RNA,这可为研究其特性及生物功能提供重要原料。在此基础上,刘梦琴[184]还将完全互补的单链环状核酸改为更容易制备的茎环结构(见图 10(B)),实现Z型核酸的快速大量制备,甚至有望通过转录直接在体内生成Z型核酸,用于细胞内的功能研究。刘梦琴[184]又在原本Lk0拓扑异构体的基础上,通过添加辅助链进一步构建了双链环状DNA的全部拓扑异构体(见图 10(C)),这可进一步接近细胞内的实际情况。Z型核酸的家族成员可能还包括左旋DNA/RNA杂合体。值得注意的是,互补的环状单链DNA和单链RNA杂交必然形成左螺旋和右螺旋共存的DNA/RNA杂合体,体内circRNA同DNA杂交时可能形成类似的结构。

|

图 10 拓扑限制法制备稳定Z型核酸 Fig. 10 Formation of stable Z-form nucleic acids by topological constraints |

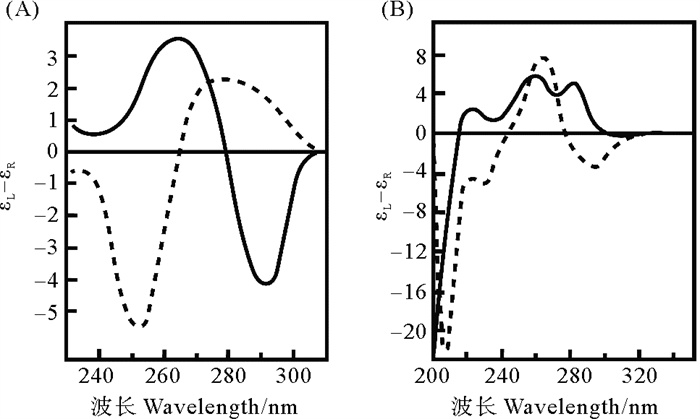

除前面提到的Z22抗体、ZBP1和ADAR1等蛋白可以特异性地识别并分析Z型核酸外,圆二色性色谱(Circular dichroism, CD)[149, 151, 176, 185]、核磁共振(NMR)[28]、X-射线晶体衍射(Diffraction of X-rays)[139]、原子力显微镜(AFM)、傅里叶红外光谱(FTIR)、荧光分析、序列分析等可用于分析鉴定Z形核酸。早在1964年,CD就被用于分析核酸结构[186],最早的Z-DNA和Z-RNA都是通过测定CD发现的[1, 5]。B-DNA的圆二色光谱在250 nm附近有负效应值峰,正效应值峰在280 nm附近;而Z-DNA在265 nm处有正效应值峰,290 nm处有负效应值峰,这一特点被广泛用于判断Z-DNA的存在(见图 11(A))。CD还被用来研究蛋白诱导的B-Z转变过程[119]、B-Z Junction[143]、一些卟啉衍生物诱导的B-Z转变[163]等。Z-RNA与Z-DNA的CD特征差异较大(见图 11(B)),Z-RNA在215 nm以上的区域都为正效应值,峰值为285 nm[5, 127]。Nichols等[127]通过CD光谱研究了A-Z Junction的CD图谱特点,发现许多RNA序列都能结合到Zα结构域并形成Z-RNA。需要指出的是,序列对核酸的CD图谱影响很大,特别是一些简单重复序列的CD同随机序列的CD差异很大。Z型核酸的CD大多源于Poly(CG)n序列,因此可能对Z型核酸的CD特征造成误解。Li等[149]发现非APP序列形成Z-DNA的CD可能与Poly(dCdG)n序列形成的Z-DNA差异巨大。

|

( (A)Poly(dGdC)n在NaCl的诱导下形成Z-DNA的圆二色光谱[1]; (B)Poly(rGrC)n在45 ℃ 6 mol/L NaCl的条件下形成Z-RNA的圆二色光谱[5]。实线为左螺旋,虚线为右螺旋。(A) Circular dichroism spectra of Z-DNA formed by Poly(dGdC)n inducted by NaCl; (B) Circular dichroism spectra of Z-RNA formed by Poly(rGrC)n at 45 ℃ 6 mol/L NaCl. The solid line is the left-handed nucleic acid, and the dotted line is the right-handed one. ) 图 11 Z型核酸的圆二色光谱 Fig. 11 Circular dichroism of Z-form nucleic acids |

其他技术分析Z型核酸举例如下:Luo等[156]用X射线衍射技术分析了Z-DNA与Ca2+的相互作用;Lee等[124]利用核磁共振研究了hZαADAR1与6 bp Z-DNA或Z-RNA结合的复合物结构和动力学。Kominami等[153]用原子力显微镜(FM-AFM)给出了Z-DNA在水溶液中的高分辨率空间成像,并能测定其表面电荷密度。Duan等[140]用傅里叶红外光谱(FTIR)监测不同的诱导条件下的B-Z转变。目前Z型核酸检测已经逐渐从体外检测过渡到体内检测中。Zhang等[170]利用FTIR光谱成功检测到了TSA(Trichostatin A)在HeLa细胞中诱导的Z-DNA。这是第一个为细胞表观遗传状态下DNA的B-Z转化提供明确实验证据的研究。Li等[130]通过FTIR光谱无标记直接检测到了胞内Z-DNA,用于探究ATP依赖性染色质重塑对Z型结构的影响。另外,Bao等[177]首次用19F NMR光谱分析了活细胞内8-三氟甲基-2′-脱氧鸟苷(FG)诱导Z-DNA的转变。

除大型仪器以外,研究人员陆续发现了一些在Z型核酸形成时荧光增强的修饰碱基,可用于研究DNA局部结构的构型变化,或用于诱导Z-DNA的形成。1969年Ward等[187]制备了2-Aminopurine(2-AP)修饰DNA,具有荧光强度随周围环境改变而变化的特性。但2-AP虽可用于B-Z Junction研究,却难以研究Z-DNA的结构变化[188]。Park等[189]开发的thdG(鸟嘌呤核苷的代替物)能根据B-DNA和Z-DNA之间的碱基堆积的不同可视化检测Z-DNA。在2015年,Yamamoto等[190]还对其加以改进,制备的2′-OMe-thG能随B-Z转变而荧光增强,可用于定点检测Z-DNA的形成。Liu等[182]引入2′-OMe-thG的修饰碱基,用于确认拓扑限制法是否形成了Z-DNA,并可进行定量研究。结果表明,在低盐浓度下,构建的LR嵌合体确实含有Z型核酸,即左手缠绕区域形成了Z-DNA。此LR嵌合体响应MgCl2、NaCl、KCl和精胺形成Z-DNA的C1/2(形成50%的Z-DNA的浓度)也被确定,分别为0.389 mmol/L、43.0 mmol/L、62.6 mmol/L和12.5 μmol/L。当离子强度大于1.0 mmol/L MgCl2、75 mmol/L NaCl或140 mmol/L KCl时,Z-DNA可完全形成。Z-DNA即使在pH=5.0时也能形成,并在更高pH值(<8.0)时表现出更强的稳定性。LR嵌合体中的Z-DNA部分在生理离子条件下(如75 mmol/L NaCl,1.0 mmol/L MgCl2或140 mmol/L KCl)非常稳定。该结果有助于研究Z-DNA的结构和生物学功能。

Wilhelmsson等[191]在2016年使用三环胞嘧啶(tCO和tCnitro)FRET(Förster共振能量转移)检测了B-DNA向Z-DNA转变时的速率常数。由于荧光染料的π堆积,这种三环胞嘧啶FRET效率在很大程度上依赖于供体和受体之间的距离和相对取向[191-192]。2019年,他们将这一技术用于监测从A型到Z型RNA的结构转变[193]。2017年,Park等[194]用thdG作为能量供体,用脱氧胞苷类似物(1, 3-diaza-2-oxophenothiazine,tC)作为能量受体,设计了第一个可进行高效FRET的沃森-克里克人工碱基对,通过荧光对取向和距离的依赖性监测DNA结构变化,实现了B-Z转变的高灵敏度检测。Kim等[122, 195]利用单分子FRET分析Z-DNA形成序列,测量了Poly(dGdC)n和Poly(dTdG)n重复序列中与ADAR1结合的DNA结构的热力学;定量确定了ADAR1对这些序列的Z型和B型的亲和力;还表征了DNA甲基转移酶(DMT)的活性和抑制剂对B-Z转换的影响。另外,结合单分子FRET和磁镊子技术,可研究控制张力和超螺旋度对B-Z转变的影响[196]。

有研究者开发了在基因组中寻找易于形成Z-DNA序列的计算方法,如Z-Hunt算法[83, 197-198]。Z-Hunt算法根据B-DNA和Z-DNA之间的自由能差预测Z-DNA的稳定性,可对负超螺旋诱导的B-DNA到Z-DNA的转变进行序列分析[197]。通过计算发现,1 Mb的人类DNA片段(包含137个基因)中有329个潜在的Z-DNA形成位点,其中许多序列位于转录起始位点附近[197]。Beknazarov等[197]提出了深度学习模型DeepZ,首次集合表观遗传标记、转录因子和RNA聚合酶结合位点等信息来预测Z-DNA区域。Lee等[198]利用Z-Hunt和DeepZ预测了含有Z-DNA的LTR元件。除此之外,Herbert等[72]还利用ZHUNT3程序(ZH3)来鉴定人类Alu重复序列中的Z-RNA形成序列。无疑,大数据及人工智能的发展以及Z型核酸相关实验数据的积累,必将大大促进Z型核酸的深入研究。

5 总结与展望随着Z型核酸介导Z型核酸结合蛋白调控免疫系统的作用机制被揭示,关于Z型核酸生物学功能的研究逐渐增多。相关研究主要集中在Z型核酸与Z型核酸结合蛋白相互作用及对下游信号通路的影响。以Z型核酸激活ZBP1相关通路为核心,将Z型核酸功能拓展至与细胞死亡的关系、ADAR1基因编辑、痘病毒免疫逃逸等方面。Z型核酸在体内的形成过程也逐渐被揭示,如Z型核酸主要由拓扑应力诱导产生,被蛋白结合后构象趋于稳定,且APP序列处更易形成。我们推测,细胞内的dsRNA部分两侧的错配部分可能处于Z-RNA构型(左螺旋)、单链状态及A-RNA构型(右螺旋)的动态平衡中,相应蛋白的结合能使Z-RNA稳定下来,并促进dsRNA部分转变为Z型。Z型核酸的人工合成和检测技术也逐渐应用到细胞内。随着人们对Z型核酸形成机制的深入研究,人工合成技术已不局限于诱导剂添加和碱基修饰,而是向模拟生物体内非修饰Z型核酸真实状态这一方向发展,以生理条件下的拓扑应力诱导为主。有越来越多的研究者利用拓扑应力诱导的Z型核酸进行生物学功能研究,这也许是未来Z型核酸研究的发展方向。Z型核酸的检测技术则着眼于细胞内检测及提高速度和灵敏度,更加简便、快速、低成本的检测方法必将快速发展。可以预见,用于相关疾病的预防及治疗的Z型核酸药物的开发将成为研究热点。同时,由于Z型核酸往往通过相应结合蛋白发挥作用,其深入研究仍然存在很大难度,需尽量谨慎以防得出错误结论。

| [1] |

Pohl F M, Jovin T M. Salt-induced co-operative conformational change of a synthetic DNA: Equilibrium and kinetic studies with poly (dG-dC)[J]. Journal of Molecular Biology, 1972, 67(3): 375-396. DOI:10.1016/0022-2836(72)90457-3 (  0) 0) |

| [2] |

Wang A H, Quigley G J, Kolpak F J, et al. Molecular structure of a left-handed double helical DNA fragment at atomic resolution[J]. Nature, 1979, 282(5740): 680-686. DOI:10.1038/282680a0 (  0) 0) |

| [3] |

Morange M. What history tells us IX. Z-DNA: When nature is not opportunistic[J]. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 2007, 32(4): 657-661. (  0) 0) |

| [4] |

Lafer E M, Möllert A, Nordheim A, et al. Antibodies specific for left-handed Z-DNA[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1981, 78(6): 3546-3550. (  0) 0) |

| [5] |

Hall K, Cruz P, Tinoco I, et al. 'Z-RNA'—a left-handed RNA double helix[J]. Nature, 1984, 311(5986): 584-586. DOI:10.1038/311584a0 (  0) 0) |

| [6] |

Uesugi S, Ohkubo M, Urata H, et al. Ribooligonucleotides, r(CGCG) analogs containing 8-substituted guanosine residues, form left-handed duplexes with Z-form-like structure[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1984, 106(12): 3675-3676. DOI:10.1021/ja00324a047 (  0) 0) |

| [7] |

Zarling D A, Calhoun C J, Feuerstein B G, et al. Cytoplasmic microinjection of immunoglobulin Gs recognizing RNA helices inhibits human cell growth[J]. Journal of Molecular Biology, 1990, 211(1): 147-160. DOI:10.1016/0022-2836(90)90017-G (  0) 0) |

| [8] |

Neidle S. Principles of Nucleic Acid Structure[M]. Oxford: Elsevier Inc, 2008: 51-77.

(  0) 0) |

| [9] |

Popenda M, Milecki J, Adamiak R W. High salt solution structure of a left-handed RNA double helix[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2004, 32(13): 4044-4054. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkh736 (  0) 0) |

| [10] |

D'Ascenzo L, Leonarski F, Vicens Q, et al. 'Z-DNA like' fragments in RNA: A recurring structural motif with implications for folding, RNA/protein recognition and immune response[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2016, 44(12): 5944-5956. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkw388 (  0) 0) |

| [11] |

D'Urso A, Holmes A E, Berova N, et al. Z-DNA recognition in B-Z-B sequences by a cationic zinc porphyrin[J]. Chemistry-An Asian Journal, 2011, 6(11): 3104-3109. DOI:10.1002/asia.201100161 (  0) 0) |

| [12] |

Wang J Q, Wang S R, Zhong C, et al. Novel insights into a major DNA oxidative lesion: Its effects on Z-DNA stabilization[J]. Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 2015, 13(34): 8996-8999. (  0) 0) |

| [13] |

Buzzo J R, Devaraj A, Gloag E S, et al. Z-form extracellular DNA is a structural component of the bacterial biofilm matrix[J]. Cell, 2021, 184(23): 5740-5758. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2021.10.010 (  0) 0) |

| [14] |

Maranhao A Q, Brigido M M. Expression of anti-Z-DNA single chain antibody variable fragment on the filamentous phage surface[J]. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 2000, 33(5): 569-579. DOI:10.1590/S0100-879X2000000500012 (  0) 0) |

| [15] |

Cerná A, Cuadrado A, Jouve N, et al. Z-DNA, a new in situ marker for transcription[J]. European Journal of Histochemistry, 2004, 48(1): 49-55. (  0) 0) |

| [16] |

Gulis G, Silva I C R, Sousa H R, et al. Characterization of an in vivo Z-DNA detection probe based on a cell nucleus accumulating intrabody[J]. Molecular Biotechnology, 2016, 58(8-9): 585-594. DOI:10.1007/s12033-016-9958-6 (  0) 0) |

| [17] |

Mulholland N, Xu Y, Sugiyama H, et al. SWI/SNF-mediated chromatin remodeling induces Z-DNA formation on a nucleosome[J]. Cell and Bioscience, 2012, 2: 3. DOI:10.1186/2045-3701-2-3 (  0) 0) |

| [18] |

Lin J, Kumari S, Kim C, et al. RIPK1 counteracts ZBP1-mediated necroptosis to inhibit inflammation[J]. Nature, 2016, 540(7631): 124-128. DOI:10.1038/nature20558 (  0) 0) |

| [19] |

Ray B K, Dhar S, Shakya A, et al. Z-DNA-forming silencer in the first exon regulates human ADAM-12 gene expression[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108(1): 103-108. (  0) 0) |

| [20] |

Renciuk D, Kypr J, Vorlickova M. CGG repeats associated with fragile X chromosome form left-handed Z-DNA structure[J]. Biopolymers, 2011, 95(3): 174-181. DOI:10.1002/bip.21555 (  0) 0) |

| [21] |

Pearson J S, Giogha C, Mühlen S, et al. EspL is a bacterial cysteine protease effector that cleaves RHIM proteins to block necroptosis and inflammation[J]. Nature Microbiology, 2017, 2: 16258. DOI:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.258 (  0) 0) |

| [22] |

Wu C X, Hu Y S, Fan L H, et al. Ctenopharyngodon idella PKZ facilitates cell apoptosis through phosphorylating eIF2 alpha[J]. Molecular Immunology, 2016, 69: 13-23. DOI:10.1016/j.molimm.2015.11.006 (  0) 0) |

| [23] |

Herbert A, Karapetyan S, Poptsova M, et al. Special Issue: A, B and Z: The structure, function and genetics of Z-DNA and Z-RNA[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 22(14): 7686. DOI:10.3390/ijms22147686 (  0) 0) |

| [24] |

Ng S K, Weissbach R, Ronson G E, et al. Proteins that contain a functional Z-DNA-binding domain localize to cytoplasmic stress granules[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2013, 41(21): 9786-9799. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkt750 (  0) 0) |

| [25] |

Gabriel L, Srinivasan B, Kus K, et al. Enrichment of Zα domains at cytoplasmic stress granules is due to their innate ability to bind to nucleic acids[J]. Journal of Cell Science, 2021, 134(10): jcs258446. DOI:10.1242/jcs.258446 (  0) 0) |

| [26] |

Periyasamy T, Joe J T X, Lu M W. Cloning and expression of Malabar grouper (Epinephelus malabaricus) ADAR1 gene in response to immune stimulants and nervous necrosis virus[J]. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 2017, 71: 116-126. (  0) 0) |

| [27] |

Cui Y H, Wang X Q, Lin F Y, et al. MiR-29a-3p improves acute lung injury by reducing alveolar epithelial cell PANoptosis[J]. Aging and Disease, 2022, 13(3): 899-909. DOI:10.14336/AD.2021.1023 (  0) 0) |

| [28] |

Lee A R, Seo Y J, Choi S R, et al. NMR elucidation of reduced B-Z transition activity of PKZ protein kinase at high NaCl concentration[J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2017, 482(2): 335-340. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.11.064 (  0) 0) |

| [29] |

Pisetsky D S, Lipsky P E. New insights into the role of antinuclear antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. Nature Reviews Rheumatology, 2020, 16(10): 565-579. DOI:10.1038/s41584-020-0480-7 (  0) 0) |

| [30] |

Diallo M A, Pirotte S, Hu Y L, et al. A fish herpesvirus highlights functional diversities among Zα domains related to phase separation induction and A-to-Z conversion[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2023, 51(2): 806-830. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkac761 (  0) 0) |

| [31] |

Rothenburg S, Deigendesch N, Dittmar K, et al. A PKR-like eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinase from zebrafish contains Z-DNA binding domains instead of dsRNA binding domains[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2005, 102(5): 1602-1607. (  0) 0) |

| [32] |

Schwartz T, Behlke J, Lowenhaupt K, et al. Structure of the DLM-1-Z-DNA complex reveals a conserved family of Z-DNA-binding proteins[J]. Nature Structural Biology, 2001, 8(9): 761-765. DOI:10.1038/nsb0901-761 (  0) 0) |

| [33] |

Liang K X, Barnett K C, Hsu M, et al. Initiator cell death event induced by SARS-CoV-2 in the human airway epithelium[J]. Science Immunology, 2024, 9(97): eadn0178. DOI:10.1126/sciimmunol.adn0178 (  0) 0) |

| [34] |

Zhang T, Yin C R, Boyd D F, et al. Influenza virus Z-RNAs induce ZBP1-mediated necroptosis[J]. Cell, 2020, 180(6): 1115-1129. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.050 (  0) 0) |

| [35] |

Wang X Y, Xiong J, Zhou D W, et al. TRIM34 modulates influenza virus-activated programmed cell death by targeting Z-DNA-binding protein 1 for K63-linked polyubiquitination[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2022, 298(3): 101611. DOI:10.1016/j.jbc.2022.101611 (  0) 0) |

| [36] |

Jeffries A M, Suptela A J, Marriott I. Z-DNA binding protein 1 mediates necroptotic and apoptotic cell death pathways in murine astrocytes following herpes simplex virus-1 infection[J]. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 2022, 19(1): 109. DOI:10.1186/s12974-022-02469-z (  0) 0) |

| [37] |

Jiao H P, Wachsmuth L, Wolf S, et al. ADAR1 averts fatal type I interferon induction by ZBP1[J]. Nature, 2022, 607(7920): 776-783. DOI:10.1038/s41586-022-04878-9 (  0) 0) |

| [38] |

Kahmann J D, Wecking D A, Putter V, et al. The solution structure of the N-terminal domain of E3L shows a tyrosine conformation that may explain its reduced affinity to Z-DNA in vitro[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2004, 101(9): 2712-2717. (  0) 0) |

| [39] |

Koehler H, Cotsmire S, Zhang T, et al. Vaccinia virus E3 prevents sensing of Z-RNA to block ZBP1-dependent necroptosis[J]. Cell Host & Microbe, 2021, 29(8): 1266-1276. (  0) 0) |

| [40] |

Licht K, Jantsch M F. The other face of an editor: ADAR1 functions in editing-independent ways[J]. Bioessays, 2017, 39(11): 1700129. DOI:10.1002/bies.201700129 (  0) 0) |

| [41] |

Nakahama T, Kato Y, Shibuya T, et al. Mutations in the adenosine deaminase ADAR1 that prevent endogenous Z-RNA binding induce Aicardi-Goutieres-syndrome-like encephalopathy[J]. Immunity, 2021, 54(9): 1976-1988. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2021.08.022 (  0) 0) |

| [42] |

Herbert A. Mendelian disease caused by variants affecting recognition of Z-DNA and Z-RNA by the Zα domain of the double-stranded RNA editing enzyme ADAR[J]. European Journal of Human Genetics, 2020, 28(1): 114-117. DOI:10.1038/s41431-019-0458-6 (  0) 0) |

| [43] |

Herbert A. ADAR and immune silencing in cancer[J]. Trends in Cancer, 2019, 5(5): 272-282. DOI:10.1016/j.trecan.2019.03.004 (  0) 0) |

| [44] |

Jiao H P, Wachsmuth L, Kumari S, et al. Z-nucleic-acid sensing triggers ZBP1-dependent necroptosis and inflammation[J]. Nature, 2020, 580(7803): 391-395. DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-2129-8 (  0) 0) |

| [45] |

Wang R C, Li H D, Wu J F, et al. Gut stem cell necroptosis by genome instability triggers bowel inflammation[J]. Nature, 2020, 580(7803): 386-390. DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-2127-x (  0) 0) |

| [46] |

Schwarzer R, Jiao H P, Wachsmuth L, et al. FADD and caspase-8 regulate gut homeostasis and inflammation by controlling MLKL- and GSDMD-mediated death of intestinal epithelial cells[J]. Immunity, 2020, 52(6): 978-993. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.002 (  0) 0) |

| [47] |

Ueda T, Iwayama T, Tomita K, et al. Zbp1-positive cells are osteogenic progenitors in periodontal ligament[J]. Scientific Reports, 2021, 11(1): 7514. DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-87016-1 (  0) 0) |

| [48] |

Kesavardhana S, Malireddi R K S, Burton A R, et al. The Zα2 domain of ZBP1 is a molecular switch regulating influenza-induced PANoptosis and perinatal lethality during development[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2020, 295(24): 8325-8330. DOI:10.1074/jbc.RA120.013752 (  0) 0) |

| [49] |

Huang Y, Yang D D, Li X Y, et al. ZBP1 is a significant pyroptosis regulator for systemic lupus erythematosus[J]. Annals of Translational Medicine, 2021, 9(24): 1773. DOI:10.21037/atm-21-6193 (  0) 0) |

| [50] |

Yang S, Chang N, Li W Y, et al. Necroptosis of macrophage is a key pathological feature in biliary atresia via GDCA/S1PR2/ZBP1/p-MLKL axis[J]. Cell Death & Disease, 2023, 14(3): 175. (  0) 0) |

| [51] |

Thapa R J, Ingram J P, Ragan K B, et al. DAI senses influenza a virus genomic RNA and activates RIPK3-dependent cell death[J]. Cell Host & Microbe, 2016, 20(5): 674-681. (  0) 0) |

| [52] |

Suresh M, Li B, Huang X, et al. Agonistic activation of cytosolic DNA sensing receptors in woodchuck hepatocyte cultures and liver for inducing antiviral effects[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2021, 12: 745802. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2021.745802 (  0) 0) |

| [53] |

Banoth B, Tuladhar S, Karki R, et al. ZBP1 promotes fungi-induced inflammasome activation and pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis (PANoptosis)[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2020, 295(52): 18276-18283. DOI:10.1074/jbc.RA120.015924 (  0) 0) |

| [54] |

Cheng R, Liu X L, Wang Z, et al. ABT-737, a Bcl-2 family inhibitor, has a synergistic effect with apoptosis by inducing urothelial carcinoma cell necroptosis[J]. Molecular Medicine Reports, 2021, 23(6): 412. DOI:10.3892/mmr.2021.12051 (  0) 0) |

| [55] |

Zheng M, Kanneganti T D. Newly identified function of caspase-6 in ZBP1-mediated innate immune responses, NLRP3 inflammasome activation, PANoptosis, and host defense[J]. Journal of cellular immunology, 2020, 2(6): 341-347. (  0) 0) |

| [56] |

Zheng M, Karki R, Vogel P, et al. Caspase-6 is a key regulator of innate immunity, inflammasome activation, and host defense[J]. Cell, 2020, 181(3): 674-687. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.040 (  0) 0) |

| [57] |

Momota M, Lelliott P, Kubo A, et al. ZBP1 governs the inflammasome-independent IL-1α and neutrophil inflammation that play a dual role in anti-influenza virus immunity[J]. International Immunology, 2020, 32(3): 203-212. DOI:10.1093/intimm/dxz070 (  0) 0) |

| [58] |

Malik G, Zhou Y. Innate immune sensing of influenza A virus[J]. Viruses-Basel, 2020, 12(3): 203-212. (  0) 0) |

| [59] |

Mutoh T, Kikuchi H, Jitsuishi T, et al. Spatiotemporal expression patterns of ZBP1 in the brain of mouse experimental stroke model[J]. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy, 2023, 134: 102362. DOI:10.1016/j.jchemneu.2023.102362 (  0) 0) |

| [60] |

Hao Q, Idell S, Tang H. M1 macrophages are more susceptible to necroptosis[J]. Journal of Cellular Immunology, 2021, 3(2): 97-102. (  0) 0) |

| [61] |

Hao Q, Kundu S, Kleam J, et al. Enhanced RIPK3 kinase activity-dependent lytic cell death in M1 but not M2 macrophages[J]. Molecular Immunology, 2021, 129: 86-93. DOI:10.1016/j.molimm.2020.11.001 (  0) 0) |

| [62] |

Nassour J, Aguiar L G, Correia A, et al. Telomere-to-mitochondria signalling by ZBP1 mediates replicative crisis[J]. Nature, 2023, 614(7949): 767-773. DOI:10.1038/s41586-023-05710-8 (  0) 0) |

| [63] |

Guo H A, Chen R L, Li P, et al. ZBP1 mediates the progression of Alzheimer's disease via pyroptosis by regulating IRF3[J]. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry, 2023, 478(12): 2849-2860. DOI:10.1007/s11010-023-04702-6 (  0) 0) |

| [64] |

Wu C X, Zhang Y B, Hu C Y. PKZ, a fish-unique eIF2α kinase involved in innate immune response[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2020, 11: 585. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00585 (  0) 0) |

| [65] |

Nikpour N, Salavati R. The RNA binding activity of the first identified trypanosome protein with Z-DNA-binding domains[J]. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9(1): 5904. DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-42409-1 (  0) 0) |

| [66] |

de Reuver R, Maelfait J. Novel insights into double-stranded RNA-mediated immunopathology[J]. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2023, 24(4): 235-249. (  0) 0) |

| [67] |

Rothenburg S, Deigendesch N, Dittmar K, et al. A PKR-like eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha kinase from zebrafish contains Z-DNA binding domains instead of dsRNA binding domains[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2005, 102(5): 1602-1607. (  0) 0) |

| [68] |

Nichols P J, Henen M A, Vicens Q, et al. Solution NMR backbone assignments of the N-terminal Zα-linker-Zβ segment from Homo sapiens ADAR1p150[J]. Biomolecular Nmr Assignments, 2021, 15(2): 273-279. DOI:10.1007/s12104-021-10017-8 (  0) 0) |

| [69] |

Chiang D C, Li Y, Ng S K. The role of the Z-DNA binding domain in innate immunity and stress granules[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2021, 11: 625504. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2020.625504 (  0) 0) |

| [70] |

Szczerba M, Subramanian S, Trainor K, et al. Small hero with great powers: vaccinia virus E3 protein and evasion of the type I IFN response[J]. Biomedicines, 2022, 10(2): 235. DOI:10.3390/biomedicines10020235 (  0) 0) |

| [71] |

Sridharan H, Ragan K B, Guo H Y, et al. Murine cytomegalovirus IE3-dependent transcription is required for DAI/ZBP1-mediated necroptosis[J]. Embo Reports, 2017, 18(8): 1429-1441. DOI:10.15252/embr.201743947 (  0) 0) |

| [72] |

Herbert A, Poptsova M. Z-RNA and the flipside of the SARS Nsp13 helicase: Is there a role for flipons in coronavirus-induced pathology[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2022, 13: 912717. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2022.912717 (  0) 0) |

| [73] |

Li S F, Zhang Y L, Guan Z Q, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Z-RNA activates the ZBP1-RIPK3 pathway to promote virus-induced inflammatory responses[J]. Cell Research, 2023, 33(3): 201-214. DOI:10.1038/s41422-022-00775-y (  0) 0) |

| [74] |

Maelfait J, Liverpool L, Bridgeman A, et al. Sensing of viral and endogenous RNA by ZBP1/DAI induces necroptosis[J]. Embo Journal, 2017, 36(17): 2529-2543. DOI:10.15252/embj.201796476 (  0) 0) |

| [75] |

Assil S, Paludan S R. Live and let die: ZBP1 senses viral and cellular RNAs to trigger necroptosis[J]. Embo Journal, 2017, 36(17): 2470-2472. DOI:10.15252/embj.201797845 (  0) 0) |

| [76] |

Baik J Y, Liu Z S, Jiao D L, et al. ZBP1 not RIPK1 mediates tumor necroptosis in breast cancer[J]. Nature Communications, 2021, 12(1): 2666. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-23004-3 (  0) 0) |

| [77] |

Saada J, McAuley R J, Marcatti M, et al. Oxidative stress induces Z-DNA-binding protein 1-dependent activation of microglia via mtDNA released from retinal pigment epithelial cells[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2022, 298(1): 101523. DOI:10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101523 (  0) 0) |

| [78] |

Lei Y J, VanPortfliet J J, Chen Y F, et al. Cooperative sensing of mitochondrial DNA by ZBP1 and cGAS promotes cardiotoxicity[J]. Cell, 2023, 186(14): 3013-3032. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2023.05.039 (  0) 0) |

| [79] |

Chen D, Ermine K, Wang Y J, et al. PUMA/RIP3 mediates chemotherapy response via necroptosis and local immune activation in colorectal cancer[J]. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, 2023, 23(3): 354-367. (  0) 0) |

| [80] |

Ding Y N, Tang X Q. Sensing mitochondrial DNA stress in cardiotoxicity[J]. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism, 2023, 34(11): 688-690. DOI:10.1016/j.tem.2023.08.012 (  0) 0) |

| [81] |

Nakahama T, Kawahara Y. The RNA-editing enzyme ADAR1: A regulatory hub that tunes multiple dsRNA-sensing pathways[J]. International Immunology, 2023, 35(3): 123-133. DOI:10.1093/intimm/dxac056 (  0) 0) |

| [82] |

Zhang T, Yin C R, Fedorov A, et al. ADAR1 masks the cancer immunotherapeutic promise of ZBP1-driven necroptosis[J]. Nature, 2022, 606(7914): 594-602. DOI:10.1038/s41586-022-04753-7 (  0) 0) |

| [83] |

Tang Q N, Rigby R E, Young G R, et al. Adenosine-to-inosine editing of endogenous Z-form RNA by the deaminase ADAR1 prevents spontaneous MAVS-dependent type Ⅰ interferon responses[J]. Immunity, 2021, 54(9): 1961-1975. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2021.08.011 (  0) 0) |

| [84] |

de Reuver R, Dierick E, Wiernicki B, et al. ADAR1 interaction with Z-RNA promotes editing of endogenous double-stranded RNA and prevents MDA5-dependent immune activation[J]. Cell Reports, 2021, 36(6): 109500. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109500 (  0) 0) |

| [85] |

Guo X F, Liu S, Sheng Y, et al. ADAR1 Zα domain P195A mutation activates the MDA5-dependent RNA-sensing signaling pathway in brain without decreasing overall RNA editing[J]. Cell Reports, 2023, 42(7): 112733. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112733 (  0) 0) |

| [86] |

Langeberg C J, Nichols P J, Henen M A, et al. Differential structural features of two mutant ADAR1p150 Zα domains associated with Aicardi-Goutières syndrome[J]. Journal of Molecular Biology, 2023, 435(8): 160840. (  0) 0) |

| [87] |

Nakahama T, Kawahara Y. Deciphering the biological significance of ADAR1-Z-RNA interactions[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 22(21): 11435. DOI:10.3390/ijms222111435 (  0) 0) |

| [88] |

Keegan L P, Vukic D, O'Connell M A. ADAR1 entraps sinister cellular dsRNAs, thresholding antiviral responses[J]. Trends in Immunology, 2021, 42(11): 953-955. DOI:10.1016/j.it.2021.09.013 (  0) 0) |

| [89] |

Zillinger T, Bartok E. ADAR1 edits the SenZ and SenZ-ability of RNA[J]. Immunity, 2021, 54(9): 1909-1911. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2021.08.021 (  0) 0) |

| [90] |

Kim J I, Nakahama T, Yamasaki R, et al. RNA editing at a limited number of sites is sufficient to prevent MDA5 activation in the mouse brain[J]. PLoS Genetics, 2021, 17(5): e1009516. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1009516 (  0) 0) |

| [91] |

Herbert A, Balachandran S. Z-DNA enhances immunotherapy by triggering death of inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts[J]. Journal for Immunotherapy of Cancer, 2022, 10(11): e005704. DOI:10.1136/jitc-2022-005704 (  0) 0) |

| [92] |

Vögel O A, Han J L N, Liang C Y, et al. The p150 isoform of ADAR1 blocks sustained RLR signaling and apoptosis during influenza virus infection[J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2020, 16(9): e1008842. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1008842 (  0) 0) |

| [93] |

Hubbard N W, Ames J M, Maurano M, et al. ADAR1 mutation causes ZBP1-dependent immunopathology[J]. Nature, 2022, 607(7920): 769-775. DOI:10.1038/s41586-022-04896-7 (  0) 0) |

| [94] |

de Reuver R, Verdonck S, Dierick E, et al. ADAR1 prevents autoinflammation by suppressing spontaneous ZBP1 activation[J]. Nature, 2022, 607(7920): 784-789. DOI:10.1038/s41586-022-04974-w (  0) 0) |

| [95] |

Karki R, Sundaram B, Sharma B R, et al. ADAR1 restricts ZBP1-mediated immune response and PANoptosis to promote tumorigenesis[J]. Cell Reports, 2021, 37(3): 109858. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109858 (  0) 0) |

| [96] |

Marshall P R, Zhao Q Y, Li X, et al. Dynamic regulation of Z-DNA in the mouse prefrontal cortex by the RNA-editing enzyme Adar1 is required for fear extinction[J]. Nature Neuroscience, 2020, 23(6): 718-729. DOI:10.1038/s41593-020-0627-5 (  0) 0) |

| [97] |

Zhang W, Tanneti N S, Fausto A, et al. The vaccinia virus E3L dsRNA binding protein detects distinct production patterns of exogenous and endogenous dsRNA[J]. Biorxiv: the Preprint Server for Biology, 2023. (  0) 0) |

| [98] |

Zheng M, Kanneganti T D. The regulation of the ZBP1-NLRP3 inflammasome and its implications in pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis (PANoptosis)[J]. Immunological Reviews, 2020, 297(1): 26-38. DOI:10.1111/imr.12909 (  0) 0) |

| [99] |

Wu M, Li M, Liu W, et al. Nucleoporin Seh1 maintains Schwann cell homeostasis by regulating genome stability and necroptosis[J]. Cell Reports, 2023, 42(7): 112802. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112802 (  0) 0) |

| [100] |

Hao Y, Yang B, Yang J K, et al. ZBP1: A powerful innate immune sensor and double-edged sword in host immunity[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2022, 23(18): 10224. DOI:10.3390/ijms231810224 (  0) 0) |

| [101] |

Chen X Y, Dai Y H, Wan X X, et al. ZBP1-mediated necroptosis: Mechanisms and therapeutic implications[J]. Molecules, 2023, 28(1): 52. (  0) 0) |

| [102] |

Karki R, Kanneganti T D. ADAR1 and ZBP1 in innate immunity, cell death, and disease[J]. Trends in Immunology, 2023, 44(3): 201-216. DOI:10.1016/j.it.2023.01.001 (  0) 0) |

| [103] |

Oh S, Lee S J. Recent advances in ZBP1-derived PANoptosis against viral infections[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2023, 14: 1148727. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1148727 (  0) 0) |

| [104] |

Straub S, Sampaio N G. Activation of cytosolic RNA sensors by endogenous ligands: Roles in disease pathogenesis[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2023, 14: 1092790. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1092790 (  0) 0) |

| [105] |

Basavaraju S, Mishra S, Jindal R, et al. Emerging role of ZBP1 in Z-RNA sensing, influenza virus-induced cell death, and pulmonary inflammation[J]. mBio, 2022, 13(3): e00401-22. (  0) 0) |

| [106] |

Tang Q N. Z-nucleic acids: Uncovering the functions from past to present[J]. European Journal of Immunology, 2022, 52(11): 1700-1711. DOI:10.1002/eji.202249968 (  0) 0) |

| [107] |

Zheng X, Lee S K, Yun J Y, et al. Protein-induced B-Z transition is kinetically accelerated by introducing single-stranded regions[J]. Bulletin of the Korean Chemical Society, 2020, 41(4): 480-483. DOI:10.1002/bkcs.11983 (  0) 0) |

| [108] |

Satange R, Chuang C Y, Neidle S, et al. Polymorphic G: G mismatches act as hotspots for inducing right-handed Z DNA by DNA intercalation[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2019, 47(16): 8899-8912. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkz653 (  0) 0) |

| [109] |

Kouzine F, Wojtowicz D, Baranello L, et al. Permanganate/S1 nuclease footprinting reveals non-B DNA structures with regulatory potential across a mammalian genome[J]. Cell Systems, 2017, 4(3): 344-356. DOI:10.1016/j.cels.2017.01.013 (  0) 0) |

| [110] |

Scott S, Xu Z M, Kouzine F, et al. Visualizing structure-mediated interactions in supercoiled DNA molecules[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2018, 46(9): 4622-4631. DOI:10.1093/nar/gky266 (  0) 0) |

| [111] |

Rich A, Zhang S G. Z-DNA: The long road to biological function[J]. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2003, 4(7): 566-572. DOI:10.1038/nrg1115 (  0) 0) |

| [112] |

Kolimi N, Ajjugal Y, Rathinavelan T. A B-Z junction induced by an A … A mismatch in GAC repeats in the gene for cartilage oligomeric matrix protein promotes binding with the hZADAR1 protein[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2017, 292(46): 18732-18746. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M117.796235 (  0) 0) |

| [113] |

Balachandran S, Mocarski E S. Viral Z-RNA triggers ZBP1-dependent cell death[J]. Current Opinion in Virology, 2021, 51: 134-140. DOI:10.1016/j.coviro.2021.10.0045331026-X78)90046-XAtmospheric Environment||70||186|2013||| (  0) 0) |

| [114] |

Nichols P J, Krall J B, Henen M A, et al. Z-RNA biology: A central role in the innate immune response[J]. RNA, 2023, 29(3): 273-281. DOI:10.1261/rna.079429.122 (  0) 0) |

| [115] |

Herbert A, Alfken J, Kim Y G, et al. A Z-DNA binding domain present in the human editing enzyme, double-stranded RNA adenosine deaminase[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1997, 94(16): 8421-8426. (  0) 0) |

| [116] |

Kim Y G, Lowenhaupt K, Oh D Y, et al. Evidence that vaccinia virulence factor E3L binds to Z-DNA in vivo: Implications for development of a therapy for poxvirus infection[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2004, 101(6): 1514-1518. (  0) 0) |

| [117] |

Schwartz T, Lowenhaupt K, Kim Y G, et al. Proteolytic dissection of Zab, the Z-DNA-binding domain of human ADAR1[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1999, 274(5): 2899-2906. DOI:10.1074/jbc.274.5.2899 (  0) 0) |

| [118] |

Brown B A, Lowenhaupt K, Wilbert C M, et al. The Z alpha domain of the editing enzyme dsRNA adenosine deaminase binds left-handed Z-RNA as well as Z-DNA[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2000, 97(25): 13532-13536. (  0) 0) |

| [119] |

Lee A R, Kim N H, Seo Y J, et al. Thermodynamic model for B-Z transition of DNA induced by Z-DNA binding proteins[J]. Molecules, 2018, 23(11): 2748. DOI:10.3390/molecules23112748 (  0) 0) |

| [120] |

Park C, Zheng X, Park C Y, et al. Dual conformational recognition by Z-DNA binding protein is important for the B-Z transition process[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2020, 48(22): 12957-12971. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkaa1115 (  0) 0) |

| [121] |

Lee A R, Choi S R, Seo Y J, et al. NMR study on the preferential binding of the Zα domain of human ADAR1 to CG-repeat DNA duplex[J]. Journal of the Korean Magnetic Resonance Society, 2017, 21(3): 90-95. DOI:10.6564/JKMRS.2017.21.3.090 (  0) 0) |

| [122] |

Kim S H, Lim S H, Lee A R, et al. Unveiling the pathway to Z-DNA in the protein-induced B-Z transition[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2018, 46(8): 4129-4137. DOI:10.1093/nar/gky200 (  0) 0) |

| [123] |

Wang Z, Zhang D P, Qiu X, et al. Structurally specific Z-DNA proteolysis targeting chimera enables targeted degradation of adenosine deaminase acting on RNA 1[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2024, 146(11): 7584-7593. DOI:10.1021/jacs.3c13646 (  0) 0) |

| [124] |

Lee A R, Hwang J, Hur J H, et al. NMR dynamics study reveals the Zα Domain of human ADAR1 associates with and dissociates from Z-RNA more slowly than Z-DNA[J]. ACS Chemical Biology, 2019, 14(2): 245-255. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.8b00914 (  0) 0) |

| [125] |

Go Y, Ahn H B, Kim B S, et al. Conformational exchange of the Zα domain of human RNA editing enzyme ADAR1 studied by NMR spectroscopy[J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2021, 580: 63-66. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.09.084 (  0) 0) |

| [126] |

Oh K I, Lee A R, Choi S R, et al. Systematic approach to find the global minimum of relaxation dispersion data for protein-induced B-Z transition of DNA[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 22(7): 3517. DOI:10.3390/ijms22073517 (  0) 0) |

| [127] |

Nichols P J, Bevers S, Henen M, et al. Recognition of non-CpG repeats in Alu and ribosomal RNAs by the Z-RNA binding domain of ADAR1 induces A-Z junctions[J]. Nature Communications, 2021, 12(1): 793. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-21039-0 (  0) 0) |

| [128] |

Nichols P J, Krall J B, Henen M A, et al. Z-form adoption of nucleic acid is a multi-step process which proceeds through a melted intermediate[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2023, 146(1): 677-694. (  0) 0) |

| [129] |

Li L, An R, Liang X G. Construction of ssDNA-attached LR-chimera involving Z-DNA for ZBP1 binding analysis[J]. Molecules, 2022, 27(12): 3706. DOI:10.3390/molecules27123706 (  0) 0) |

| [130] |

Li Y L, Huang Q, Yao G H, et al. Remodeling chromatin induces Z-DNA conformation detected through fourier transform infrared spectroscopy[J]. Analytical Chemistry, 2020, 92(21): 14452-14458. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.0c02432 (  0) 0) |

| [131] |

Fleming A M, Zhu J, Ding Y, et al. Oxidative modification of guanine in a potential Z-DNA-forming sequence of a gene promoter impacts gene expression[J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 2019, 32(5): 899-909. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.9b00041 (  0) 0) |

| [132] |

Yang T, Wang G D, Zhang M X, et al. Triggering endogenous Z-RNA sensing for anti-tumor therapy through ZBP1-dependent necroptosis[J]. Cell Reports, 2023, 42(11): 113377. DOI:10.1016/j.celrep.2023.113377 (  0) 0) |

| [133] |

Zhao C Y, Ma Y J, Zhang M H, et al. Polyamine metabolism controls B-to-Z DNA transition to orchestrate DNA sensor cGAS activity[J]. Immunity, 2023, 56(11): 2508-2522. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2023.09.012 (  0) 0) |

| [134] |

Herbert A. To "Z" or not to "Z": Z-RNA, self-recognition, and the MDA5 helicase[J]. PLoS Genetics, 2021, 17(5): e1009513. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1009513 (  0) 0) |

| [135] |

Kim S H, Jung H J, Lee I B, et al. Sequence-dependent cost for Z-form shapes the torsion-driven B-Z transition via close interplay of Z-DNA and DNA bubble[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2021, 49(7): 3651-3660. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkab153 (  0) 0) |

| [136] |

Drozdzal P, Gilski M, Jaskolski M. Crystal structure of Z-DNA in complex with the polyamine putrescine and potassium cations at ultra-high resolution[J]. Acta Crystallographica Section B-Structural Science Crystal Engineering and Materials, 2021, 77(3): 331-338. DOI:10.1107/S2052520621002663 (  0) 0) |

| [137] |

Harp J M, Coates L, Sullivan B, et al. Water structure around a left-handed Z-DNA fragment analyzed by cryo neutron crystallography[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2021, 49(8): 4782-4792. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkab264 (  0) 0) |

| [138] |

Harp J M, Coates L, Sullivan B, et al. Cryo-neutron crystallographic data collection and preliminary refinement of left-handed Z-DNA d(CGCGCG)[J]. Acta Crystallographica Section F-Structural Biology Communications, 2018, 74(10): 603-609. DOI:10.1107/S2053230X1801066X (  0) 0) |

| [139] |

Luo Z P, Dauter Z, Gilski M. Four highly pseudosymmetric and/or twinned structures of d(CGCGCG)2 extend the repertoire of crystal structures of Z-DNA[J]. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Structural Biology, 2017, 73(11): 940-951. DOI:10.1107/S2059798317014954 (  0) 0) |

| [140] |

Duan M M, Li Y L, Zhang F Q, et al. Assessing B-Z DNA transitions in solutions via infrared spectroscopy[J]. Biomolecules, 2023, 13(6): 964. DOI:10.3390/biom13060964 (  0) 0) |

| [141] |

Kim D, Hur J, Han J H, et al. Sequence preference and structural heterogeneity of BZ junctions[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2018, 46(19): 10504-10513. DOI:10.1093/nar/gky784 (  0) 0) |

| [142] |

Son H, Bae S, Lee S. A thermodynamic understanding of the salt-induced B-to-Z transition of DNA containing BZ junctions[J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2021, 583: 142-145. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.10.065 (  0) 0) |

| [143] |

Subramani V K, Ravichandran S, Bansal V, et al. Chemical-induced formation of BZ-junction with base extrusion[J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2019, 508(4): 1215-1220. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.12.045 (  0) 0) |

| [144] |

Ajjugal Y, Rathinavelan T. Sequence dependent influence of an A…A mismatch in a DNA duplex: An insight into the recognition by hZαADAR1 protein[J]. Journal of Structural Biology, 2021, 213(1): 107678. DOI:10.1016/j.jsb.2020.107678 (  0) 0) |

| [145] |

Fakharzadeh A, Zhang J H, Roland C, et al. Novel eGZ-motif formed by regularly extruded guanine bases in a left-handed Z-DNA helix as a major motif behind CGG trinucleotide repeats[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2022, 50(9): 4860-4876. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkac339 (  0) 0) |

| [146] |

D'Ascenzo L, Vicens Q, Auffinger P. Identification of receptors for UNCG and GNRA Z-turns and their occurrence in rRNA[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2018, 46(15): 7989-7997. DOI:10.1093/nar/gky578 (  0) 0) |

| [147] |

Herbert A. ALU non-B-DNA conformations, flipons, binary codes and evolution[J]. Royal Society Open Science, 2020, 7(6): 200222. DOI:10.1098/rsos.200222 (  0) 0) |

| [148] |

Herbert A. Z-DNA and Z-RNA in human disease[J]. Communications Biology, 2019, 2: 7. DOI:10.1038/s42003-018-0237-x (  0) 0) |

| [149] |

Li L, Zhang Y P, Ma W Z, et al. Nonalternating purine pyrimidine sequences can form stable left-handed DNA duplex by strong topological constraint[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2022, 50(2): 684-696. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkab1283 (  0) 0) |

| [150] |

Maity A, Singh A, Singh N. Differential stability of DNA based on salt concentration[J]. European Biophysics Journal with Biophysics Letters, 2017, 46(1): 33-40. DOI:10.1007/s00249-016-1132-3 (  0) 0) |

| [151] |

Bhanjadeo M M, Nial P S, Sathyaseelan C, et al. Biophysical interaction between lanthanum chloride and (CG)n or (GC)n repeats: A reversible B-to-Z DNA transition[J]. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 2022, 216: 698-709. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.07.020 (  0) 0) |

| [152] |

Yi J, Yeou S, Lee N K. DNA bending force facilitates Z-DNA formation under physiological salt conditions[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2022, 144(29): 13137-13145. DOI:10.1021/jacs.2c02466 (  0) 0) |

| [153] |

Kominami H, Kobayashi K, Yamada H. Molecular-scale visualization and surface charge density measurement of Z-DNA in aqueous solution[J]. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9(1): 6851. DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-42394-5 (  0) 0) |

| [154] |

Bhanjadeo M M, Subudhi U. Praseodymium promotes B-Z transition in self-assembled DNA nanostructures[J]. RSC Advances, 2019, 9(8): 4616-4620. DOI:10.1039/C8RA10164G (  0) 0) |

| [155] |

Bhanjadeo M M, Nayak A K, Subudhi U. Cerium chloride stimulated controlled conversion of B-to-Z DNA in self-assembled nanostructures[J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2017, 482(4): 916-921. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.11.133 (  0) 0) |

| [156] |

Luo Z P, Dauter Z. The crystal structure of Z-DNA with untypically coordinated Ca2+ ions[J]. Journal of Biological Inorganic Chemistry, 2018, 23(2): 253-259. DOI:10.1007/s00775-017-1526-4 (  0) 0) |

| [157] |

Leonarski F, D'Ascenzo L, Auffinger P. Mg2+ ions: Do they bind to nucleobase nitrogens[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2017, 45(2): 987-1004. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkw1175 (  0) 0) |

| [158] |

Kawara K, Tsuji G, Taniguchi Y, et al. Synchronized chiral induction between[5]helicene-spermine ligand and B-Z DNA transition[J]. Chemistry-a European Journal, 2017, 23(8): 1763-1769. DOI:10.1002/chem.201605276 (  0) 0) |

| [159] |

Wang S R, Wan J Q, Xu G H, et al. The cucurbit[7]uril-based supramolecular chemistry for reversible B/Z-DNA transition[J]. Advanced Science, 2018, 5(7): 1800231. DOI:10.1002/advs.201800231on?journalTitle=实用临床护理学电子杂志&year=2019&firstpage=152&issue=08 (  0) 0) |

| [160] |

Qin T X, Liu K H, Song D, et al. Binding interactions of zinc cationic porphyrin with duplex DNA: From B-DNA to Z-DNA[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2018, 19(4): 1071. DOI:10.3390/ijms19041071 (  0) 0) |

| [161] |

Gangemi C M A, D'Urso A, Tomaselli G A, et al. A novel porphyrin-based molecular probe ZnTCPPSpm4 with catalytic, stabilizing and chiroptical diagnostic power towards DNA B-Z transition[J]. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry, 2017, 173: 141-143. DOI:10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2017.05.008 (  0) 0) |

| [162] |

Gaeta M, Farini S, Gangemi C M A, et al. Interactions of mono spermine porphyrin derivative with DNAs[J]. Chirality, 2020, 32(10): 1243-1249. DOI:10.1002/chir.23272 (  0) 0) |

| [163] |

Kwon N, Han J H, Kim S K, et al. Effect of periphery cationic substituents of porphyrin on the B-Z transition of poly[d(A-T)2], poly[d(G-C)2] and their binding modes[J]. Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics, 2021, 39(2): 518-525. (  0) 0) |

| [164] |

Tunçer S, Gurbanov R, Sheraj I, et al. Low dose dimethyl sulfoxide driven gross molecular changes have the potential to interfere with various cellular processes[J]. Scientific Reports, 2018, 8(1): 14828. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-33234-z (  0) 0) |

| [165] |

Phromsiri P, Gerling R R, Blose J M. The effects of a neutral cosolute on the B to Z transition for DNA duplexes incorporating both CG and CA steps[J]. Nucleosides Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids, 2017, 36(11): 690-703. (  0) 0) |

| [166] |

Andrzejewska W, Wilkowska M, Chrabaszczewska M, et al. The study of complexation between dicationic surfactants and the DNA duplex using structural and spectroscopic methods[J]. RSC Advances, 2017, 7(42): 26006-26018. DOI:10.1039/C6RA24978G (  0) 0) |

| [167] |

Laginha R C, Martins C B, Brandao A L C, et al. Evaluation of the cytotoxic effect of Pd2Spm against prostate cancer through vibrational microspectroscopies[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24(3): 1888. DOI:10.3390/ijms24031888 (  0) 0) |

| [168] |

Safina A, Cheney P, Pal M, et al. FACT is a sensor of DNA torsional stress in eukaryotic cells[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2017, 45(4): 1925-1945. (  0) 0) |

| [169] |

Li J, Tang M, Ke R X, et al. The anti-cancer drug candidate CBL0137 induced necroptosis via forming left-handed Z-DNA and its binding protein ZBP1 in liver cells[J]. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2024, 482: 116765. DOI:10.1016/j.taap.2023.116765 (  0) 0) |

| [170] |

Zhang F Q, Huang Q, Yan J W, et al. Histone acetylation induced transformation of B-DNA to Z-DNA in cells probed through FT-IR spectroscopy[J]. Analytical Chemistry, 2016, 88(8): 4179-4182. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00400 (  0) 0) |

| [171] |

Balasubramaniyam T, Ishizuka T, Xiao C D, et al. 2'-O-methyl-8-methylguanosine as a Z-form RNA stabilizer for structural and functional study of Z-RNA[J]. Molecules, 2018, 23(10): 2572. DOI:10.3390/molecules23102572 (  0) 0) |

| [172] |

Balasubramaniyam T, Ishizuka T, Xu Y. Stability and properties of Z-DNA containing artificial nucleobase 2'-O-methyl-8-methyl guanosine[J]. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, 2019, 27(2): 364-369. (  0) 0) |

| [173] |

Bao H L, Masuzawa T, Oyoshi T, et al. Oligonucleotides DNA containing 8-trifluoromethyl-2'-deoxyguanosine for observing Z-DNA structure[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2020, 48(13): 7041-7051. (  0) 0) |

| [174] |

Ferreira J M, Sheardy R D. Linking temperature, cation concentration and water activity for the B to Z conformational transition in DNA[J]. Molecules, 2018, 23(7): 1806. DOI:10.3390/molecules23071806 (  0) 0) |

| [175] |

Vongsutilers V, Sawaspaiboontawee K, Tuesuwan B, et al. 5-Methylcytosine containing CG decamer as Z-DNA embedded sequence for a potential Z-DNA binding protein probe[J]. Nucleosides Nucleotides & Nucleic Acids, 2018, 37(9): 485-497. (  0) 0) |

| [176] |

Vongsutilers V, Shinohara Y, Kawai G. Epigenetic TET-catalyzed oxidative products of 5-methylcytosine impede Z-DNA formation of CG Decamers[J]. ACS Omega, 2020, 5(14): 8056-8064. DOI:10.1021/acsomega.0c00120 (  0) 0) |

| [177] |

Bao H L, Masuzawa T, Oyoshi T, et al. Oligonucleotides DNA containing 8-trifluoromethyl-2'-deoxyguanosine for observing Z-DNA structure[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2020, 48(13): 7041-7051. (  0) 0) |

| [178] |

Stettler U H, Weber H, Koller T, et al. Preparation and characterization of form V DNA, the duplex DNA resulting from association of complementary, circular single-stranded DNA[J]. Journal of Molecular Biology, 1979, 131(1): 21-40. DOI:10.1016/0022-2836(79)90299-7 (  0) 0) |

| [179] |

Pohl F M, Thomae R, DiCapua E. Antibodies to Z-DNA interact with form V DNA[J]. Nature, 1982, 300(5892): 545-546. DOI:10.1038/300545a0 (  0) 0) |

| [180] |

Shouche Y S, Latha P K, Ramesh N, et al. Left handed DNA in synthetic and topologically constrained form V DNA and its implications in protein recognition[J]. Journal of Biosciences, 1985, 8(3-4): 563-578. DOI:10.1007/BF02702756 (  0) 0) |

| [181] |

Zhang Y P, Cui Y X, An R, et al. Topologically constrained formation of stable Z-DNA from normal sequence under physiological conditions[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2019, 141(19): 7758-7764. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b13855 (  0) 0) |

| [182] |

Liu M Q, Cui Y X, Zhang Y P, et al. Single base-modification reports and locates Z-DNA conformation on a Z-B-chimera formed by topological constraint[J]. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Japan, 2022, 95(3): 433-439. DOI:10.1246/bcsj.20210400 (  0) 0) |

| [183] |

Meng Y Y, Wang G L, He H J, et al. Z-DNA is remodelled by ZBTB43 in prospermatogonia to safeguard the germline genome and epigenome[J]. Nature Cell Biology, 2022, 24(7): 1141-1153. DOI:10.1038/s41556-022-00941-9 (  0) 0) |

| [184] |

刘梦琴. 基于单链环状核酸杂交的Z型核酸制备及性能研究[D]. 青岛: 中国海洋大学, 2023. Liu M Q. Formation and Properties of Z-form Nucleic Acid Based on Circular Single-Strand Nucleic Acids Hybridization[D]. Qingdao: Ocean University of China, 2023. (  0) 0) |

| [185] |

Kypr J, Kejnovská I, Renciuk D, et al. Circular dichroism and conformational polymorphism of DNA[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2009, 37(6): 1713-1725. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkp026 (  0) 0) |

| [186] |

Brahms J, Mommaerts W F H M. A study of conformation of nucleic acids in solution by means of circular dichroism[J]. Journal of Molecular Biology, 1964, 10(1): 73-88. DOI:10.1016/S0022-2836(64)80029-2 (  0) 0) |

| [187] |

Ward D C, Reich E, Stryer L. Fluorescence studies of nucleotides and polynucleotides: Ⅰ. Formycin, 2-aminopurine riboside, 2, 6-diaminopurine riboside, and their derivatives[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1969, 244(5): 1228-1237. DOI:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)91833-8 (  0) 0) |

| [188] |

Börjesson K, Preus S, El-Sagheer A H, et al. Nucleic acid base analog FRET-pair facilitating detailed structural measurements in nucleic acid containing systems[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2009, 131(12): 4288-4293. DOI:10.1021/ja806944w (  0) 0) |

| [189] |

Park S, Otomo H, Zheng L J, et al. Highly emissive deoxyguanosine analogue capable of direct visualization of B-Z transition[J]. Chemical Communications, 2014, 50(13): 1573-1575. DOI:10.1039/c3cc48297a (  0) 0) |

| [190] |

Yamamoto S, Park S, Sugiyama H. Development of a visible nanothermometer with a highly emissive 2'-O-methylated guanosine analogue[J]. RSC Advances, 2015, 5(126): 104601-104605. DOI:10.1039/C5RA24756Je=unixref&xml=|Diabetes Technol Ther||25|5|329|2023||| (  0) 0) |

| [191] |

Dumat B, Larsen A F, Wilhelmsson L M. Studying Z-DNA and B- to Z-DNA transitions using a cytosine analogue FRET-pair[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2016, 44(11): e101. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkw114 (  0) 0) |

| [192] |

Bood M, Sarangamath S, Wranne M S, et al. Fluorescent nucleobase analogues for base-base FRET in nucleic acids: synthesis, photophysics and applications[J]. Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2018, 14: 114-129. DOI:10.3762/bjoc.14.7 (  0) 0) |

| [193] |

Füchtbauer A F, Wranne M S, Bood M, et al. Interbase FRET in RNA: From A to Z[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2019, 47(19): 9990-9997. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkz812 (  0) 0) |

| [194] |

Han J H, Yamamoto S, Park S, et al. Development of a vivid FRET system based on a highly emissive dG-dC analogue pair[J]. Chemistry-a European Journal, 2017, 23(31): 7607-7613. DOI:10.1002/chem.201701118 (  0) 0) |

| [195] |

Kim S H, Jung H J, Hong S C. Z-DNA as a tool for nuclease-free DNA methyltransferase assay[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 22(21): 11990. DOI:10.3390/ijms222111990 (  0) 0) |

| [196] |

Lee M, Kim S H, Hong S C. Minute negative superhelicity is sufficient to induce the B-Z transition in the presence of low tension[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2010, 107(11): 4985-4990. (  0) 0) |

| [197] |

Beknazarov N, Jin S, Poptsova M. Deep learning approach for predicting functional Z-DNA regions using omics data[J]. Scientific Reports, 2020, 10(1): 19134. DOI:10.1038/s41598-020-76203-1 (  0) 0) |

| [198] |

Lee D, Bae W H, Ha H, et al. Z-DNA-containing long terminal repeats of human endogenous retrovirus families provide alternative promoters for human functional genes[J]. Molecules and Cells, 2022, 45(8): 522-530. DOI:10.14348/molcells.2022.0060 (  0) 0) |

2. Laboratory for Marine Drugs and Bioproducts, Qingdao Marine Science and Technology Center, Qingdao 266237, China;

3. School of Medicine and Pharmacy, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266003, China;

4. Shenzhen Bay Laboratory, Pingshan Translational Medicine Center, Shenzhen 518118, China

2024, Vol. 54

2024, Vol. 54