2) Institute of Evolution and Marine Biodiversity, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266003, China;

3) Guangdong Neilingding-Futian National Reserve Administration Bureau, Shenzhen 518040, China

Mangroves are trees and shrubs that grow in saline coastal habitats in the tropics and subtropics. Mangrove wetlands are a special type of wetland ecosystem in the transition zone between terrestrial ecosystems and marine ecosystems (Cao et al., 2008). As an important ecological type of coastal ecosystem, mangroves are also one of the most productive natural ecosystems on earth (Daza et al., 2020). Mangroves provide a considerable abundance and diversity of living resources, and they play an important role in preventing and controlling pollution of coastal waters and protecting the biodiversity of coastal areas. Mangrove ecosystems are one of the most versatile habitats for microorganisms with high potentials (Nathan et al., 2020). Mangroves also function as windbreaks and embankments to protect coastal areas from erosion (Field, 1998; Lewis, 2005; Pinto et al., 2013).

Meiofauna are a group of benthic animals that can pass through a 0.5 mm mesh but retained by a 0.042 mm mesh. Several scholars have suggested the use of 0.031 mm mesh screen as the lower limit for meiofauna (Zhang and Zhou, 2004), because there are some mature individuals of meiofauna can be retained between 0.031 mm mesh and 0.042 mm mesh. Therefore, in this study, a 0.031 mm mesh was used as the lower limit. Meiofauna are key components and an intermediate link in marine food chains. As consumers, they play important roles in matter cycling and energy flow in the mangrove ecosystem. Meiofauna have been widely used in marine environmental monitoring and ecosystem health evaluation systems (McIntyre, 1969; Zhang et al., 2017; Majdi et al., 2020; Zhao and Liu, 2021).

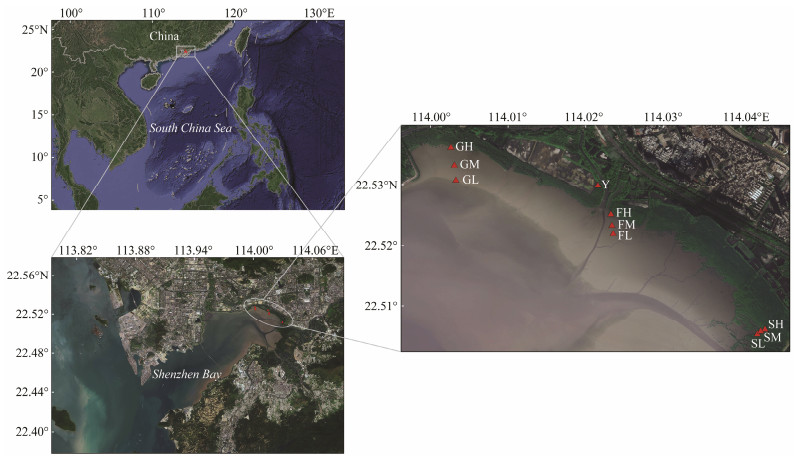

Mangrove habitats possess complex organic detrital food chains, and serve as feeding ground and refuge for surrounding microorganisms (Zhu et al., 2012). In the mangrove ecosystem, several benthic organisms thrive because of the rapid progress of the matter cycle (Ghosh and Mandal, 2019). Among the benthic metazoans, meiofauna is the most dominant in number (Netto and Gallucci, 2003; Zhao et al., 2020). Meiofauna play an ecologically important role as a food source for macrofauna and in organic matter recycling (Murray et al., 2002; Danovaro et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2019). The Futian Mangrove Reserve is located in the northeast of Shenzhen Bay (22°30΄N, 113°56΄E), China. It is distributed in a strip shape with an area of approximately 367.64 hm2, comprising of land area of 139.92 hm2 and tidal area of 227.72 hm2. It is the only national nature reserve in the Chinese hinterland (Lu, 2014). Several researches have been carried out in the Futian Mangrove habitat of Shenzhen Bay, including environmental pollution (Zheng and Lin, 1996) and ecological (Chen et al., 1996) studies. Research on macrofauna in the Futian Mangrove in Shenzhen began with the study of macrofauna communities (Gao et al., 2004), focusing mainly on community structure, population ecology, and pollution ecology (Ma et al., 2003; Cai et al., 2011). The study of meiofauna in the mangrove of the Futian Mangrove area of Shenzhen Bay started in 1997, mainly on the species composition and seasonal variation of marine nematodes in Futian mudflats (Cai et al., 2000). Tan et al. (2017) reported the structure of meiofauna communities in the mangrove area of Futian. The purpose of this study was to investigate the spatio-temporal dynamics of taxa composition, abundance, and biomass of meiofauna in the mangrove tidal flat of Futian, and to examine the influence of environmental factors on meiofauna population and biomass.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Field SamplingSediment samples for meiofauna and environmental factors analysis were collected in July (summer) and October (autumn) of 2013, January (winter) and April (spring) of 2014 at 10 sites in the Guanniao Pavilion (G), Fengtang Estuary (F), Shazui Wharf (S), and a fishpond (Y) in the mangrove habitat of Futian in the northeast of Shenzhen Bay (Fig.1). Each area was sampled at high (H), middle (M), and low (L) points, except Site Y, and each sampling point was taken three times as a parallel sample. In order to determine the seasonal dynamics, the samples were collected in spring (SP), summer (SU), autumn (AU), and winter (WI) at the 10 sites, GH, GM, GL, FH, FM, FL, SH, SM, SL, and Y. Due to restrictions in July 2013, the Fengtang Estuary (F) was not sampled at that time.

|

Fig. 1 Sampling sites in the Futian Mangrove tidal flat, Shenzhen, China. |

At each sampling site, three undisturbed sediments were randomly collected as replicate samples using sampling tubes (reformed by plastic syringes) with an inner diameter of 2.9 cm. The core sample was 11 cm in length. To examine the vertical distribution of meiofauna, cores were sectioned into 4 layers (0 – 2, 2–5, 5 – 8 and 8 – 11 cm) into a 250 mL plastic bottle. All core samples were fixed with 5% buffered formaldehyde. In addition, surface sediment samples were also collected and frozen to −20℃ at each site to determine the grain size, organic matter content, water content, chlorophyll a (Chl-a), and phaeophorbide (Pha).

A YSI 600XLMMulti-Parameter Water Quality Sonde (YSI Inc., USA) was used to measure the dissolved oxygen, temperature, and salinity of interstitial water at each sampling site in situ.

2.2 Laboratory AnalysisSediment samples for meiofauna were stained with 1‰ Rose Bengal for over 24 h, followed by wet sieving with tap water, using 0.5 mm and 0.031 mm meshes to remove clay and silt. Meiofauna samples were extracted by flotation and centrifugation (1800 r min−1, 10 min) using a colloidal silica solution (Ludox™, Aldrich Chemical Company) with a specific gravity of 1.15 g cm−3 (Liu et al., 2015), and the process was repeated thrice. Different samples were washed into different petri dishes and meiofauna were counted under a stereomicroscope.

Environmental characteristics of sediments were determined by oceanographic survey (State Quality and Technical Supervision Administration of China, 2007). Briefly, Chl-a and Pha were measured using a fluorophotometer. The sediment median grain size was measured using a Malvern Mastersizer 3000 particle size analyzer. The sediment organic matter content was measured using the potassium

dichromate-sulfuric acid (K2Cr2O7-H2SO4) oxidization method.

2.3 Statistical AnalysisThe biomass of meiofauna was determined using transformation coefficients. Table 1 lists the coefficients from abundance to biomass of meiofauna taxa. The average dry weight of individuals in different groups of meiofauna was based on Widbom (1984), Zhang et al. (2001) and Liu et al.(2005, 2018).

|

|

Table 1 Individual dry weight of different meiofauna taxa |

Multivariate analyses were carried out using PRIMER 6 (Clarke and Gorley, 2006) statistical software package, including hierarchical clustering (CLUSTER), principal component analysis (PCA), and BIOENV. SPSS 22 software was used to analyze the variance and correlation of biological data and environmental factors. If the variances were not uniform, the Games-Howell test was carried out.

3 Results 3.1 Environmental FactorsThe characteristics of sediments from the 10 sampling sites in the four seasons are shown in Table 2. The highest temperature was 35℃ at the SU-Y sampling site, and the lowest temperature was 13℃ at the WI-Y sampling site. The average salinity was 12.39, which was far below the normal value of 35 in oceanic seawater. Results of oneway ANOVA showed that there were highly significant seasonal differences in temperature (F = 43.322, P < 0.001) and salinity (F = 220.133, P < 0.001). SPSS bivariate analysis showed a significant negative correlation between temperature and salinity.

|

|

Table 2 Environmental factors at the sampling sites in the Futian Mangrove area of the Shenzhen Bay tidal flat, China |

There were two types, including clay-silt and sand-siltclay, of sediment in the sampling area. From analysis, the AU-FL station was sand-silt-clay, but the other stations were clay-silt. The clay content ranged from 28.01% to 41.96%, and the silt content ranged from 49.00% to 68.74%. The median grain size range was 0.00497 – 0.00862 mm. There were no significant differences in sediment types at each station.

In July and October of 2013, January and April of 2014, the highest values of sediment Chl-a concentration was observed in spring (1.88 μg g−1), followed by winter (1.76 μg g−1), autumn (1.38 μg g−1), and summer (0.53 μg g−1). There were significant seasonal differences in Chl-a concentration between spring and summer as well as summer and winter (F = 5.456, P = 0.004). The highest values of sediment Pha concentration was observed in autumn (7.73 μg g−1), followed by spring (7.00 μg g−1), summer (6.98 μg g−1), and winter (6.62 μg g−1). However, there were no significant seasonal differences in Pha concentration (F = 1.154, P = 0.342).

The average organic matter content of the sediments at the 10 sites in the four seasons of Futian Mangrove was 9.2%. The highest value was recorded at the WI-Y site (16.27%), and the lowest value was recorded at the AUFM site (4.51%). SPSS one-way ANOVA analysis showed that there were no significant seasonal differences in organic matter content (F = 1.062, P = 0.378).

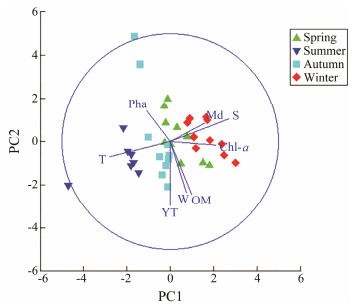

Principal component analysis was performed using standardized data of environmental factors. The result showed that the PC1 and PC2 axis accounted for 55.9% of environmental variability. On the PC1 axis, there was an increasing trend for median grain size, salinity, and Chl-a from left to right. On the PC2 axis, Pha increased gradually, while the silt-clay content, water content, and organic matter content gradually decreased from top to bottom (Fig.2).

|

Fig. 2 PCA of environmental factors for the sampling stations in the Futian Mangrove tidal flat, Shenzhen, China. |

A total of 14 meiofaunal taxa were identified in the four sampling seasons, including Nematoda, Copepoda, Polychaeta, Oligochaeta, Isopoda, Gammarid, Halacaroidea, Nauplia, Ostracoda, Insecta, Bivalvia, Thermosbaenacea, Turbellaria, Tanaidacea. There were also undetermined taxa that fell into others (Table 3). Table 4 shows the average abundance and biomass of main meiofaunal taxa in the Futian Mangrove tidal flat, Shenzhen, China. The results showed that the largest number of taxa 12 was recorded in spring; followed by 8 taxa recorded in summer and autumn; and 6 taxa recorded in winter. Nematodes were the most dominant group, accounting for 97.54%, 99.29%, 96.14%, and 97.26% of the total abundance of meiofauna in the four seasons, respectively.

|

|

Table 3a Abundance of each meiofaunal taxon in spring and summer in the Futian Mangrove area of the Shenzhen Bay tidal flat |

|

|

Table 3b Abundance of each meiofaunal taxon in autumn and winter in the Futian Mangrove area of the Shenzhen Bay tidal flat |

|

|

Table 4 Average abundance and biomass of main meiofaunal taxa in the Futian Mangrove tidal flat, Shenzhen, China |

In terms of seasonal variation, the average abundance of meiofauna was the highest in summer ((5136.35 ± 623.38) ind (10 cm)−2), followed by those in spring ((2714.04 ± 869.21) ind (10 cm)−2), winter ((581.55 ± 185.48) ind (10 cm)−2), and autumn ((488.35 ± 71.29) ind (10 cm)−2). In terms of spatial distribution, the highest meiofaunal abundance was recorded at site GH in summer (10828.03 ind (10 cm)−2), and the lowest was recorded at site FM in winter (30.80 ind (10 cm)−2).

In terms of seasonal variation, the average biomass of meiofauna was the highest in summer ((2423.10 ± 419.94) μg dwt (10 cm)−2), followed by those in spring ((1835.87 ± 312.10) μg dwt (10 cm)−2), winter (433.09 ± 93.76 μg dwt (10 cm)−2), and autumn ((421.56 ± 156.70) μg dwt (10 cm)−2). In terms of spatial distribution, the highest value of meiofaunal biomass was recorded at site SH in spring (5591.16 μg dwt (10 cm)−2) and the lowest value was recorded at site FL in winter (15.55 μg dwt (10 cm)−2). In terms of biomass, nematodes were the most dominant group, followed by polychaetes.

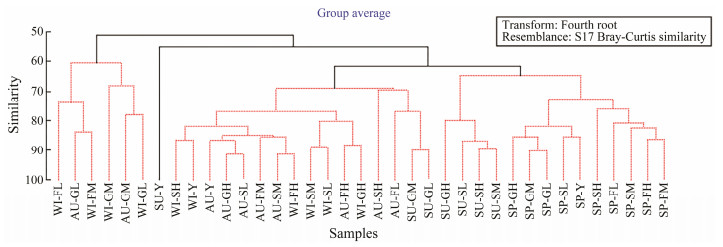

3.2.2 CLUSTER analysisResults of the CLUSTER analysis (Fig.3) based on the abundance of meiofauna at all the sampling sites in the four seasons showed that the meiofaunal assemblages could be divided into four groups. Group 1 included the sites in autumn (GM, GL) and winter (GM, GL, FM, FL). Group 2 included only a site in summer (Y). Group 3 included the sites in summer (GM, GL), autumn (GH, FH, FM, FL, SH, SM, SL, Y), and winter (SH, SM, SL, FH, GH, Y). Group 4 included the sites in spring (GH, GM, GL, FH, FM, FL, SH, SM, SL, Y) and summer (GH, SH, SM, SL). The results showed that the community structure in spring was similar to that in summer, and the community structure in autumn was similar to that in winter. The community structures of the mid-tidal and the low-tidal areas are similar.

|

Fig. 3 CLUSTER analysis based on meiofaunal abundances in the Futian Mangrove tidal flat, Shenzhen, China. |

The vertical distribution of meiofauna (Fig.4) showed that the proportions of meiofauna distributed at 0 – 2, 2 – 5, 5 – 8, and 8 – 11 cm were 61.36%, 28.20%, 7.22%, and 3.67%, respectively. Meiofauna were mainly distributed in the upper and middle sediment layers (0 – 5 cm), accounting for 89.56% of the total meiofauna, while the remaining 10.44% of meiofauna were distributed in 5 – 11 cm. The proportion of nematodes distributed in 0 – 2, 2 – 5, 5 – 8, and 8 – 11 cm was 61.36%, 28.24%, 7.18%, and 3.67%, respectively. It showed a similar trend to the distribution of meiofauna.

|

Fig. 4 Vertical distribution of the abundance of total meiofauna and nematodes. |

The results of the correlation analysis showed that meiofaunal and nematode abundance, and meiofaunal biomass were significantly negatively correlated to salinity. This indicated that salinity was the most important environmental factor determining meiofaunal distribution.

BIOENV analysis showed that meiofauna community was affected by a variety of environmental factors (Table 5). This explains why the best combination of environmental factors was temperature and salinity, and the correlation coefficient was 0.221. Temperature showed the highest influence among the environmental factors considered, with a correlation coefficient of 0.187.

|

|

Table 5 Results of BIOENV analysis between meiofaunal assemblage and environmental variables |

Mangroves are rich in tannic acid and organic matter, hence, there are significant differences between meiofauna in mangrove and non-mangrove habitats (Gee and Somerfield, 1997; Sahoo et al., 2013). Benthic biologists worldwide have carried out several studies on meiofauna in different mangrove areas. In the present study, there were differences in the assemblages and abundance of meiofauna in different mangrove sites examined (Table 6).

|

|

Table 6 Comparison of meiofauna studies in different mangrove areas |

In the present study, a total of 14 meiofaunal taxa were identified during the four sampling seasons. A total of 7 meiofaunal taxa were found and the abundance of meiofauna was (1572 ± 389) ind (10 cm)−2 in the mangrove area in Futian, Shenzhen Bay by Tan et al. (2017). In this study, the sampling sediment depth was 9 cm, and the upper and lower limits of mesh sizes were 0.5 mm and 0.042 mm, respectively. Zhu et al. (2020) studied the meiofauna in the mangrove area of Futian, Shenzhen Bay in winter with 5 cm sampling sediment depth. Only 5 meiofaunal taxa, including nematodes, copepods, polychaetes, oligochaetes and unidentified groups, were found and the meiofaunal abundance was (490.73 ± 465.09) ind (10 cm)−2. Therefore, differences in sampling seasons, sediment depth (11 cm in the present study) and the upper and lower limits of mesh sizes (0.5 mm/0.031 mm in the present study) may be responsible for the higher taxa number recorded in the present study compared with the abovementioned studies.

Although the numbers of taxa reported in different studies vary largely between mangrove habitats, nematodes constitute a large percentage of taxa in most reports. Consistent with most studies on mangrove habitats, nematodes accounted for 98.35% in the present study. On the contrary, nematode population was relatively low in the mangrove habitat on the west coast of Zanzibar (Olafsson et al., 2000), which was because foraminifera constituted the dominant group in that habitat.

Alongi (1987) reported that meiofauna abundance on sandy beaches can reach 1000 – 8000 ind (10 cm)−2, and can be lower than 500 ind (10 cm)−2 in mangrove areas. However, most studies have shown that meiofauna abundance in mangrove areas is higher than 500 ind (10 cm)−2. The meiofauna abundance in the present study was much higher than 500 ind (10 cm)−2, indicating that the Futian mangrove habitat had high productivity. The higher meiofauna abundance in the present study may also be as a result of the differences in sampling depth and mesh size used in this study compared to previous studies.

4.2 Relationships Between Meiofauna and Environmental FactorsLi et al. (2012) studied the distribution and seasonal variation of meiofauna in the intertidal zone of Qingdao sandy beach. Studies have shown that there are significant seasonal changes in the vertical distribution of meiofauna. In winter, due to the low temperature, meiofauna migrates from the surface sediment layer to deeper sediment layer. In summer, due to the increased temperature and increased availability of food in the surface sediment layer, they migrate back to the surface. The Futian mangrove habitat is located at lower latitudes and has higher temperatures throughout the year. Unlike the vertical distribution of meiofauna observed in the intertidal zone of Qingdao sandy beach (Li et al., 2012), there were no significant seasonal variations in the vertical distribution of meiofauna in mangroves. Several factors, including biotic and abiotic factors, affect the vertical distribution of meiofauna. Biotic factors, such as food (Rysgaard et al., 1994) and human activities, and abiotic factors, such as organic matter, water content, temperature, and salinity, affect the vertical distribution of meiofauna (Warwick and Buchanan, 1970; Heip et al., 1985). Additionally, fauna distribution differs with intertidal zones, and is also affected by seasonal changes. However, most research results indicate that meiofauna are mainly distributed in surface sediments (Alongi, 1986).

The reason for the significant seasonal changes in the taxa composition and abundance of meiofauna in the Futian mangroves may be due to the effects of seasonal changes of environmental variables, such as interstitial water temperature and salinity. In the present study, the major influencing factors are temperature and salinity based on BIOENV analysis. Moreover, salinity and abundance are significantly negatively correlated based on Correlation analysis. According to the Shenzhen Meteorological Bureau data, rainfall in Shenzhen is mainly in spring (March to May), summer (June to August), and early autumn (September). SPSS bivariate analyses show that temperature and precipitation are significantly positively correlated; salinity and precipitation are significantly negatively correlated; and precipitation is positively correlated with meiofaunal abundance and biomass. However, few studies have shown that in the northern intertidal zone or shallow sea habitats, meiofaunal abundance and salinity are significantly related (Zhang et al., 2001; Li et al., 2012). This can be attributed to the lesser rainfall and larger temperature difference in the north, which results in more obvious temperature effects. However, in the south, during the rainy season, large amount of fresh water flushes the intertidal zone, resulting in decreased salinity. Therefore, salinity is an important seasonal environmental variable in the present study.

Results of one-way ANOVA showed no significant differences in meiofaunal abundance between autumn and winter; however, there were significant differences between other seasons. This study is consistent with the conclusions of Palmer and Coull (1980). Cai (2000) reported that nematode density was highest in spring, followed by those in winter, summer, and lowest in autumn. This shows that temperature is an important seasonal environmental variable; however, the changes in meiofaunal abundance cannot be attributed solely to its effect. Zou et al. (2020) reported that sediment type was the most important factor for the differences of meiofaunal abundance in Dongwan mangrove wetland of Fangchenggang, Guangxi, China. Hua et al. (2020) also found that the differences in nematode abundance were mainly due to the seasonal dynamic changes of sedimentary environmental factors and the seasonal dynamic changes of sediment type.

Seawater has a strong transportation capacity; hence, periodic scouring will change the clay content, silt content, and sand content of sediments. Meiofauna living in the intertidal sediments of mangroves are affected not only by changes in environmental factors, but also by the activities of other animals and humans (Ingole and Parulekar, 1998). Therefore, the reasons for the differences in the structure and abundance of meiofauna communities in different mangrove areas are complex and diverse. The effect of seasonal variables, such as temperature and salinity, on the distribution of meiofauna needs further study.

The present study provides basic information for seasonal distribution of meiofauna in the Futian Mangrove Reserve. However, in order to reflect the annual fluctuation of meiofauna, continuous studies of meiofauna should be carried out. Additionally, meiofaunal distribution in various mangrove habitats should also be studied to reveal the general patterns. Moreover, species composition of marine nematodes, which are the most dominant group generally in meiofauna, should also be studied to understand the more precise species diversity in mangrove ecosystem.

AcknowledgementsThis study was jointly supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Nos. 201964 024 and 201362018) and the Biodiversity Investigation, Observation and Assessment Program (2019 – 2023) of Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China. We appreciate Dr. Qinghe Liu and Mr. Deming Huang for their help in the field sampling. We are also very grateful to Dr. Zihao Yuan, Mr. Shan Cai and Ms. Xiaomeng Liu for their help in the laboratory analysis.

Abdullah, M. M., and Lee, S. Y., 2016. Structure of mangrove meiofaunal assemblages associated with local sediment conditions in subtropical eastern Australia. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 198: 438-449. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2016.10.039 (  0) 0) |

Alongi, D. M., 1986. Quantitative estimates of benthic protozoa in tropical marine systems using silica gel: A comparison of methods. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 23(4): 443-450. DOI:10.1016/0272-7714(86)90002-8 (  0) 0) |

Alongi, D. M., 1987. Inter estuary variation and intertidal zonation of free-living nematode communities in tropical mangrove systems. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 40: 103-104. DOI:10.3354/meps040103 (  0) 0) |

Cai, L. Z., Chen, X. W., Wu, C., Peng, X., Cao, J., and Fu, S. J., 2011. Temporal and spatial variation of macrofaunal communities in Shenzhen Bay intertidal zone between 1995 and 2010. Biodiversity Science, 19(6): 702-709 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1003.2011.08124 (  0) 0) |

Cai, L. Z., Li, H. M., and Zou, C. Z., 2000. Species composition and seasonal variation of marine nematodes on Futian mudflat in Shenzhen Estuary. Chinese Biodiversity, 8(4): 385-390 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1005-0094.2000.04.005 (  0) 0) |

Cao, Q. M., Zheng, K. Z., Chen, G., and Chen, G. Z., 2008. A review of studies on microbiology of mangrove ecosystems. Ecology and Environment, 17(2): 839-845 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.16258/j.cnki.1674-5906.2008.02.054 (  0) 0) |

Chang, Y., and Guo, Y. Q., 2014. Study on meiofauna abundance and nematode diversity in mangrove of Luoyang River, Fujian Province. Journal of Jimei University (Natural Science), 19(1): 7-12 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-7405.2014.01.002 (  0) 0) |

Chen, G. Z., Miao, S. Y., and Zhang, J. H., 1996. Ecologic study on the mangrove forest in Futian Nature Reserve, Shenzhen, China. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Sunyatseni, 35: 298-304 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Chen, X. W., Li, X., Zeng, J. L., Tan, W. J., Zhou, X. P., Hong, W. S., et al., 2017. Meiofauna communities in artificial mangrove wetland in Xiatanwei of Tong'an Bay, Xiamen. Journal of Xiamen University (Natural Science), 56(3): 351-358 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.6043/j.issn.0438-0479.201604002 (  0) 0) |

Clarke, K. R., and Gorley, R. N., 2006. PRIMER v6: User Manual/Tutorial. PRIMER-E, Plymouth, 190pp.

(  0) 0) |

Danovaro, R., Scopa, M., Gambi, C., and Fraschetti, S., 2007. Trophic importance of subtidal metazoan meiofauna: Evidence from in situ exclusion experiments on soft and rocky substrates. Marine Biology, 152(2): 339-350. DOI:10.1007/s00227-007-0696-y (  0) 0) |

Daza, D. A. V., Moreno, H. S., Portz, L., Manzolli, R. P., Bolívar-Anillo, H. J., and Anfuso, G., 2020. Mangrove forests evolution and threats in the Caribbean Sea of Colombia. Water, 12(4): 1113. DOI:10.3390/w12041113 (  0) 0) |

Dye, A. H., 1983. Composition and seasonal fluctuations of meiofauna in a southern African mangrove estuary. Marine Biology, 73(2): 165-170. DOI:10.1007/BF00406884 (  0) 0) |

Field, C. D., 1998. Rehabilitation of mangrove ecosystems: An overview. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 37(8-12): 383-392. DOI:10.1016/S0025-326X(99)00106-X (  0) 0) |

Gao, Y., Cai, L. Z., Ma, L., Xu, H. L., Wang, Y. J., and Zan, Q. J., 2004. Vertical distribution of macrobenthos of Futian mangrove mudflat in Shenzhen Bay. Journal of Oceanography in Taiwan Strait, 23(1): 76-81 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-8160.2004.01.013 (  0) 0) |

Gee, J. M., and Somerfield, P. J., 1997. Do mangrove diversity and leaf litter decay promote meiofaunal diversity. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 218(1): 13-33. DOI:10.1016/S0022-0981(97)00065-8 (  0) 0) |

Ghosh, M., and Mandal, S., 2019. Does vertical distribution of meiobenthic community structure differ among various mangrove habitats of Sundarban Estuarine System?. Regional Studies in Marine Science, 31: 1-11. DOI:10.1016/j.rsma.2019.100778 (  0) 0) |

Guo, Y. Q., 2008. The study on the community of free-living marine nematodes in Fenglin mangrove wetlands, Xiamen, China. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 30(4): 147-153 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0253-4193.2008.04.018 (  0) 0) |

Heip, C. H., Vincx, M., and Vranken, G., 1985. The ecology of marine nematodes. Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review, 23: 399-489. (  0) 0) |

Hua, E., Cui, C. Y., Xu, H. L., and Liu, X. S., 2020. Study on the community characteristics of marine nematodes in Futian Mangrove Reserve, Shenzhen. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 50(9): 46-63 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.16441/j.cnki.hdxb.20200125 (  0) 0) |

Ingole, B. S., and Parulekar, A. H., 1998. Role of salinity in structuring the intertidal meiofauna of a tropical estuarine beach: Field evidence. Indian Journal of Marine Science, 27(3-4): 356-361. (  0) 0) |

Lewis, R. R., 2005. Ecological engineering for successful management and restoration of mangrove forests. Ecological Engineering, 24(4): 403-418. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2004.10.003 (  0) 0) |

Li, J., Hua, E., and Zhang, Z. N., 2012. Distribution and seasonal dynamics of meiofauna in intertidal zone of Qingdao sandy beaches, Shandong Province of East China. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 23(12): 3458-3466. (  0) 0) |

Liu, J. L., Huang, B., and Liang, Z. W., 2013. Study on abundance and biomass of benthic meiofauna in mangrove of Dongzhai Bay. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 35(2): 187-192 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0253-4193.2013.02.020 (  0) 0) |

Liu, M. D., Chen, J. C., Guo, Y. Q., Lu, Z, Q., Li, X. S., and Chang, Y., 2018. Study on the individual dry weight of marine nematodes in mangrove sediments. Haiyang Xuebao, 40(8): 89-96 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0253-4193.2018.08.009 (  0) 0) |

Liu, X. S., Huang, D. M., Zhu, Y. M., Chang, T. Y., Liu, Q. H., Huang, L., et al., 2015. Bioassessment of marine sediment quality using meiofaunal assemblages in a semi-enclosed bay. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 100(1): 92-101. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.09.024 (  0) 0) |

Liu, X. S., Zhang, Z. N., and Huang, Y., 2005. Abundance and biomass of meiobenthos in the spawning ground of anchovy (Engraulis japanicus) in the southern Huanghai Sea. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 24(3): 94-104. (  0) 0) |

Lu, Q., Zeng, X. K., Shi, J. H., Chen, L. E., Zhou, K., Lei, A. P., et al., 2014. Succession of a mangrove forest in Futian, Shenzhen Bay. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 34(16): 4662-4671 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.5846/stxb201212271885 (  0) 0) |

Ma, L., Cai, L. Z., and Yuan, D. X., 2003. Advances of studies on mangrove bent hic fauna pollution ecology. Journal of Oceanography in Taiwan Strait, 22(1): 113-119 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-8160.2003.01.017 (  0) 0) |

Majdi, N., Colls, M., Weiss, L., Acuna, V., Sabater, S., and Traunspurger, W., 2020. Duration and frequency of non-flow periods affect the abundance and diversity of stream meiofauna. Freshwater Biology, 65(11): 1906-1922. DOI:10.1111/fwb.13587 (  0) 0) |

McIntyre, A. D., 1969. Ecology of marine meiobenthos. Biological Reviews, 44: 245-288. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1969.tb00828.x (  0) 0) |

Murray, J. M. H., Meadows, A., and Meadows, P. S., 2002. Biogeomorphological implications of microscale interactions between sediment geotechnics and marine benthos: A review. Geomorphology, 47(1): 15-30. DOI:10.1016/S0169-555X(02)00138-1 (  0) 0) |

Nathan, V. K., Vijayan, J., and Parvathi, A., 2020. Optimization of urease production by Bacillus halodurans PO15: A mangrove bacterium from Poovar mangroves, India. Marine Life Science & Technology, 2(2): 194-202. DOI:10.1007/s42995-020-00031-5 (  0) 0) |

Netto, S. A., and Gallucci, F., 2003. Meiofauna and macrofauna communities in a mangrove from the Island of Santa Catarina, South Brazil. Hydrobiologia, 505(1-3): 159-170. DOI:10.1023/B:HYDR.0000007304.22992.b2 (  0) 0) |

Olafsson, E., Carlstrom, S., and Ndaro, S. G. M., 2000. Meiobenthos of hypersaline tropical mangrove sediment in relation to spring tide inundation. Hydrobiologia, 426(1-3): 57-64. DOI:10.1023/A:1003992211656 (  0) 0) |

Palmer, M. A., and Coull, B. C., 1980. The prediction of development rate and the effect of temperature for the meiobenthic copepod, Microarthridion littorale (Poppe). Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 48(1): 73-83. DOI:10.1016/0022-0981(80)90008-8 (  0) 0) |

Pinto, T. K., Austen, M. C. V., Warwick, R. M., Somerfield, P. J., Esteves, A. M., Castro, F. J. V., et al., 2013. Nematode diversity in different microhabitats in a mangrove region. Marine Ecology, 34(3): 257-268. DOI:10.1111/maec.12011 (  0) 0) |

Rysgaard, S., Risgaard-Petersen, N., Peter, S. N., Kim, J., and Peter, N. L., 1994. Oxygen regulation of nitrification and denitrification in sediments. Limnology and Oceanography, 39(7): 1643-1652. DOI:10.4319/lo.1994.39.7.1643 (  0) 0) |

Sahoo, G., Suchiang, S. R., and Ansari, Z. A., 2013. Meiofaunamangrove interaction: A pilot study from a tropical mangrove habitat. Cahiers de Biologie Marine, 54(3): 349-358. (  0) 0) |

Tan, W. J., Zeng, J. L., Li, C. L., Rao, Y. Y., Chen, X. W., and Cai, L. Z., 2017. Characteristic analysis of benthic meiofauna communities in Futian mangrove area of the Shenzhen Bay. Journal of Xiamen University (Natural Science), 56(6): 859-865 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.60433/j.issn.0438-0479.2016100 (  0) 0) |

Thilagavathi, B., Das, B., Saravanakumar, A., and Raja, K., 2011. Benthic meiofaunal composition and community structure in the Sethukuda mangrove area and adjacent open sea, East coast of India. Ocean Science Journal, 46(2): 63-72. DOI:10.1007/s12601-011-0006-y (  0) 0) |

Wang, X. X., Liu, X. S., and Xu, J. S., 2019. Distribution patterns of meiofauna assemblages and their relationship with environmental factors of deep sea adjacent to the Yap Trench, Western Pacific Ocean. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6: 735. DOI:10.3389/fmars.2019.00735 (  0) 0) |

Warwick, R. M., and Buchanan, J. B., 1970. The meiofauna off the coast of Northumberland I. The structure of the nematode population. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 50(1): 129-146. (  0) 0) |

Widbom, B., 1984. Determination of average individual dry weights and ash-free dry weights in different sieve fractions of marine meiofauna. Marine Biology, 84(1): 101-108. DOI:10.1007/BF00394532 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Z. N., and Zhou, H., 2004. Some progress on the study of meiofauna. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 34(5): 799-806 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.16441/j.cnki.hdxb.2004.05.019 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Z. N., Zhou, H., Hua, E., Mu, F. H., Liu, X. S., and Yu, Z. S., 2017. Meiofauna study for the forty years in China – Progress and prospect. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 48(4): 657-671 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.11693/hyhz20170100022 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Z. N., Zhou, H., Yu, Z. S., and Han, J., 2001. Abundance and biomass of the benthic meiofauna in the northern softbottom of the Jiaozhou bay. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 32(2): 139-147 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0029-814X.2001.02.004 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, M. H., and Liu, X. S., 2021. Taxa composition and distribution patterns of meiofauna in the intertidal zones of Shandong Peninsula. Journal of Liaocheng University (Natural Science Edition), 34(5): 100-110 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.19728/j.issn1672-6634.2021.05.013 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, M. H., Liu, Q. H., Zhang, D. S., Liu, Z. S., Wang, C. S., and Liu, X. S., 2020. Deep-sea meiofauna assemblages with special reference to marine nematodes in the Caiwei Guyot and a Polymetallic Nodule Field in the Pacific Ocean. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 160(12): 111564. DOI:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111564 (  0) 0) |

Zheng, W. J., and Lin, P., 1996. Accumulation and distribution of Cu, Pb, Zn and Cd in Avicennia marina mangrove community of Futian in Shenzhen. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 27(4): 386-393 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Zhu, H. L., Liu, M. D., Zhou, Y. H., and Guo, Y. Q., 2020. Meiofauna community structure and marine nematode (a new record) in Futian mangrove wetland of Shenzhen Bay, Guangdong Province. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 39(6): 1806-1812 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.13292/j.1000-4890.202006.021 (  0) 0) |

Zhu, Y. Z., Guo, J. L., and Wu, G. J., 2012. Organic carbon in mangrove wetlands: A review. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 31(10): 2681-2687 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.13292/j.1000-4890.2012.0380 (  0) 0) |

Zou, M. M., Zhu, H. L., and Guo, Y. Q., 2020. Abundance and biomass of meiofauna in spring in Dongwan mangrove wetland of Fangchenggang, Guangxi. Chinese Journal of Ecology, 39(6): 1823-1829 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.13292/j.1000-4890.202006.038 (  0) 0) |

2022, Vol. 21

2022, Vol. 21