2) North China Sea Marine Forecasting Center of SOA, Qingdao 266102, China

Phytoplankton is the chief primary producer in the ocean, and its productivity accounts for half of the global primary productivity (Diaz et al., 2021). It is vital for ecosystem functions and biogeochemical cycle (Anderson et al., 2021). During their growth and reproduction, phytoplankton enables the migration of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur between seawater and particulate matter and changes the elements between different forms, thereby substantially contributing to the marine carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycles.

Phytoplankton play an important role in the nitrogen cycle (Arandia-gorostidi et al., 2017; Buchanan et al., 2021), and ammonium assimilation by phytoplankton is an important transformation pathway in the marine nitrogen cycle (Wan et al., 2018). It can also absorb some element forms with a low use rate, such as DON, to maintain their own life activities (Berman and Bronk, 2003; Bronk et al., 2007). Studying the bioavailability of phytoplankton for offshore DON is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the formation mechanism and ecological effects of offshore eutrophication (Yang, 2021), as the bioavailability of phytoplankton can provide a basis for the marine nitrogen cycle.

With increasingly prominent global environmental problems, climate change has become a research hotspot. The size and structure of phytoplankton communities affect the global capacity for carbon sequestration (Henson et al., 2021; Zaiss et al., 2021). As an important indicator for quantifying the primary productivity of ecosystems, carbon storage plays a role in the measurement of the regulatory ability of ecosystems and global warming. The response of marine carbon sinks to climate change is an indispensable part of this research. The carbon content of phytoplankton is an important indicator when estimating the carbon storage (Fletcher et al., 2006; Quere et al., 2008; Gruber et al., 2019). In addition, phytoplankton are closely related to the formation of dimethyl sulfur (DMS), and methyl sulfonic acid (MSA) released by marine phytoplankton can form sulfur-containing aerosols and cool the global climate (Sunda et al., 2002). Therefore, the calculation of the carbon and sulfur contents of phytoplankton is important for the study and regulation of global climate change.

As such, in this study, we measured the cell carbon content of a single species of phytoplankton using an elemental analyzer. By counting, we determined the amount of carbon contained in a single phytoplankton cell, fully considering the specificity between species. Compared to the cell volume conversion method (Harrison et al., 2015), this method can avoid large errors in the obtained converted cell carbon content because a reasonable cell volume model has not yet been constructed. We measured the contents of nitrogen and sulfur in phytoplankton, and the findings enriched the research on marine phytoplankton.

In our investigation of phytoplankton in a sea area, we used the measured element values combined with cell abundance to draw a distribution map of phytoplankton element content in the sea. We then used the element content in the sea to represent biomass and define dominant species, which reflects the contribution of each population to material circulation and energy flow, and more intuitively reflects community changes from the perspective of the population. The method can also be used to investigate the effects of changes to the phytoplankton culture conditions to obtain the values of the cell element contents under different environmental variables to improve the accuracy of the estimation of phytoplankton biomass in the sea.

2 Material and Methods 2.1 MaterialsIn this experiment, we selected twenty species of phytoplankton to study the changes in carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents at different temperatures. Among them, the six species of dinoflagellate were Karlodinium veneficum, Amphidinium carterae, Gymnodinium spp., Akashiwo sanguinea, Alexandrium tamarense, and Prorocentrum dentatum; the fourteen considered species of diatoms were Chaetoceros pseudocurvisetus, Chaetoceros castracanei, Chaetoceros affinis, Chaetoceros constrictus, Chaetoceros lorenzianus, Chaetoceros teres, Chaetoceros debili, Bacteriastrum hyalinum, Coscinodiscus granii, Coscinodiscus wailesii, Stephanopyxis turris, Stephanopyxis palmeriana, Helicotheca tamesis, and Guinardia flaccida.

2.2 Experimental Methods 2.2.1 Isolation and purification of phytoplanktonWe used a plankton net with an aperture of 20 μm for the biological trawl. A single alga was sucked out by the micropipette method and cultured in a 96-well plate equipped with F/2 medium. After the density was increased, we gradually transferred the algae to a 24-well plate and a conical flask for amplification and culture.

2.2.2 Culture methodWe collected the seawater used for the phytoplankton culture from the Qingdao coast. We filtered the seawater using cellulose acetate filter membrane(MCE, Tianjin jinteng Experimental Equipment Co., Ltd., China) with a pore aperture of 0.45 μm and diameter of 47 mm. We poured filtered seawater into a clean triangular flask, and fastened the bottle mouth with a bottle sealing membrane; the bottle was cooled after pasteurization.

The F/2 culture medium contained sodium nitrate mother liquor, disodium hydrogen phosphate mother liquor, sodium silicate mother liquor, trace element mother liquor, and vitamin mother liquor (Shanghai Guangyu Biological Technology Co., Ltd., China). We added the F/2 culture medium to the sterilized filtered seawater in a ratio of 1 L seawater to 1 mL of mother liquor.

We inoculated the algae species in the exponential growth stage into 100 mL F/2 culture medium on a clean workbench. Each species of algae was separately set at four culture temperatures, 15, 20, 25, and 30℃. The selected temperatures reflect the temperature range during summer and autumn in China's sea. We placed the cells in a light incubator (GXZ-280B, Ningbo Jiangnan Instrument Factory, China) with a light intensity of 4500 lux and a light: dark ratio of 12:12 h for one-time culture.

2.2.3 Growth curve measurementThe algae used in this experiment were in the middle and late stages of exponential growth. Therefore, we measured and drew the growth curves of different algae at different temperatures. We took a high-concentration algal solution, diluted it to different concentrations, and then performed the counting. We determined the absorbance value using a microplate reader (Synergy LX, BioTek Co., USA), and established the regression equation between cell concentration and absorbance. After, we only measured the absorbance to obtain the algal solution concentration and draw the growth curve.

Owing to the differences in algae volume and properties, the densities of algae in the middle and late stages of exponential growth differ. Among the diatoms, Chaetoceros spp. has the highest algal density (approximately 104–105 cells mL−1), followed by Bacteriastrum hyalinum (approximately 104 cells mL−1). Stephanopyxis spp. and Guinardia flaccida have large volume and relatively low density (approximately 103 cells mL−1), and Coscinodiscus spp. has the largest volume and lowest algal density, approximately 102 cells mL−1. Among the dinoflagellates, Karlodinium veneficum, Amphidinium carterae, and Prorocentrum dentatum have a small volume and the highest density, approximately 105 cells mL−1; the densities of Gymnodinium spp., Alexandrium tamarense, and Akashiwo sanguinea are approximately 104–105, 103–104, and 103 cells mL−1, respectively.

2.2.4 Determination and calculation of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur content in cellsWhen algae entered the middle and late stages of exponential growth, we took three parallel samples for each alga at each temperature. The specific steps were as follows:

We placed a certain amount of algae liquid into the plankton counting frame (Hydro-Bios, Kiel, Germany), which we fixed with Lugol's iodine solution at a concentration of 2%, then performed the counting under an inversed fluorescent DIC microscope (Ti2-U, Nikon Co., Japan). We repeated the counting at least three times, and the counting error was no more than 15%. We report the average value of these three measurements.

We filtered a certain amount of algal liquid through a filter membrane (Ms380 25 mm high-purity quartz fiber) that was pre-burned in a muffle furnace (550℃, 4–5 h). We then dried the liquid in an oven at 55℃ for 24 h to a constant weight. We wrapped the filter membrane in a tin boat, pressed it into a drug sheet with a 6 mm sampler to form the samples, and measured the contents of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur in cells using an elemental analyzer (unicube, Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany), According to the counting results, we calculated the cell carbon, nitrogen and sulfur contents of a single cell.

2.3 Data AnalysisThe coefficient of variation (CV) was used according to the classical statistical method to measure the degree of variation in each observation value in the data.

CV = (Standard deviation/Mean) × 100% (George et al., 2003).

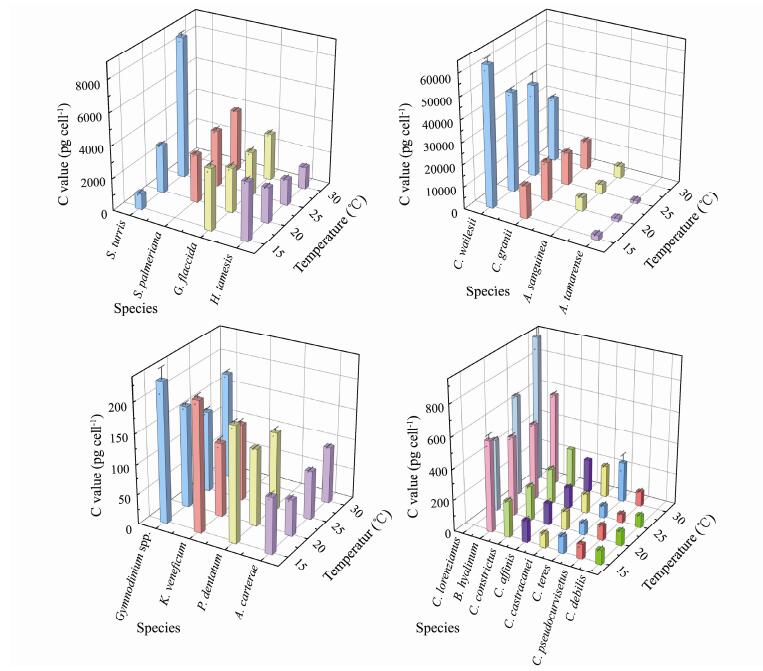

3 Results 3.1 Carbon Content of Phytoplankton CellsAmong the 20 species of phytoplankton studied, 17 grew and reproduced at 15℃. At 20 and 25℃, all 20 types of phytoplankton grew normally. At 30℃, 16 types of phytoplankton maintained their growth. As shown in (Fig.1), we observed species specificity in the carbon content of phytoplankton cells. The lowest carbon content in a single cell was 57.55 pg cell−1 (Chaetoceros pseudocurvisetus at 25℃), which ranged up to 63023.6 pg cell−1 (Coscinodiscus wailesii at 15℃). The minimum CV was 0.12% (Chaetoceros debilis at 25℃), and the maximum was 19.43% (Stephanopyxis turris at 25℃). Although temperature affected the carbon content of phytoplankton cells, its degree of influence caused different effects, as presented in Table 1, under the four temperatures. We observed maximum variations for Stephanopyxis turris, with a CV of 72.79%, and the CV for Chaetoceros affinis was the smallest, at 6.14%.

|

Fig. 1 Cell carbon content of different phytoplankton under four temperatures. |

|

|

Table 1 Coefficient of variation of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents in the same phytoplankton cells under different temperatures |

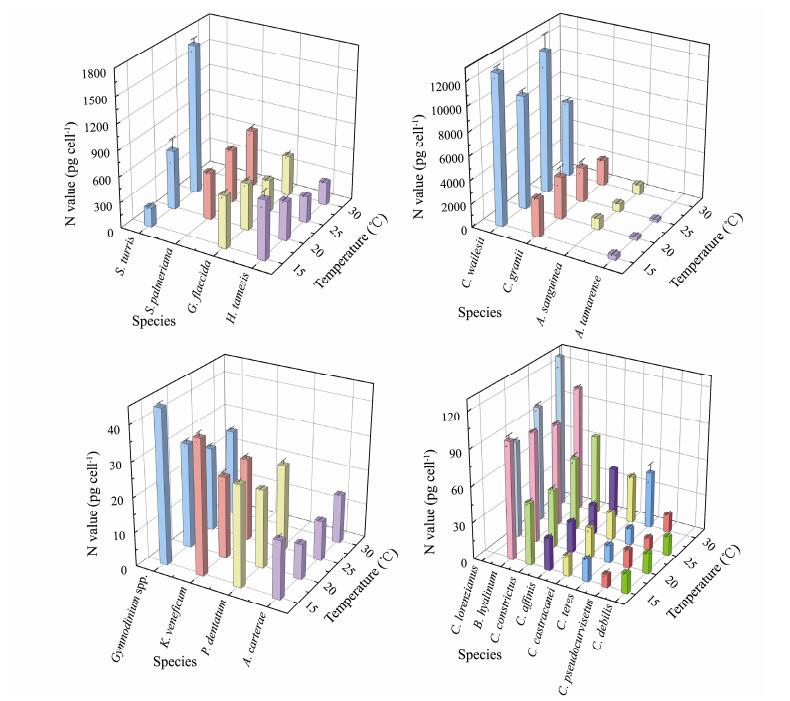

Similar to carbon content, the nitrogen content in different types of phytoplankton cells also differed (Fig.2). The lowest nitrogen content in a single cell was 10.42 pg cell−1 (Amphidinium carterae at 20℃) and the highest was 12559.11 pg cell−1 (Coscinodiscus wailesii at 15℃). The CV ranged between 0.17% (Chaetoceros debilis at 25 ℃) and 19.75% (Alexandrium tamarense at 20℃). Temperature changes affected the nitrogen content. The content was most variable in Chaetoceros teres, with a CV as high as 66.41%. The degree of variation for the content in Chaetoceros debilis was the lowest, with a CV of only 5.00%.

|

Fig. 2 Cell nitrogen contents of different phytoplankton under four temperatures. |

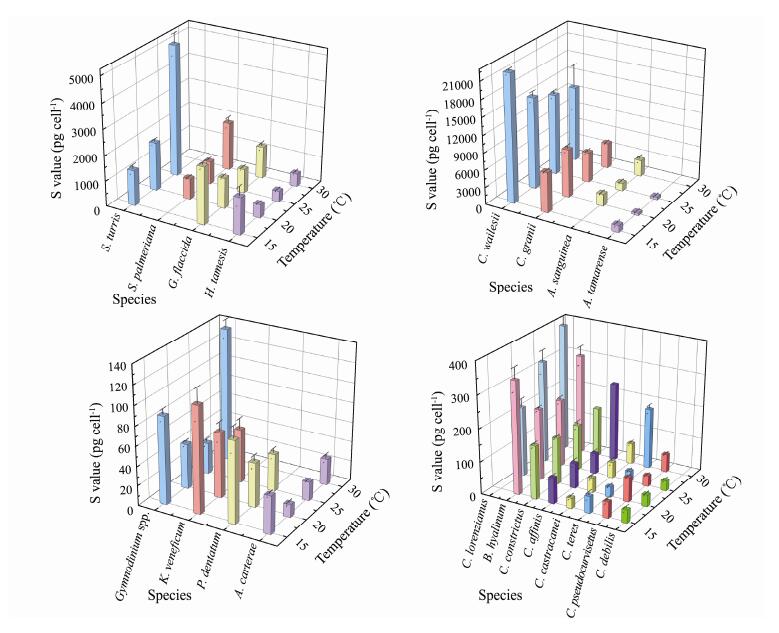

The sulfur content was also affected by species and temperature changes (Fig.3). The lowest sulfur content in a single cell was 12.75 pg cell−1 (Amphidinium carterae at 20℃), and the highest was 22205.22 pg cell−1 (Coscinodiscus wailesii at 15℃). The CV fluctuated between 0.87% (Coscinodiscus granii at 15℃) and 29.16% (Coscinodiscus wailesii at 30℃). Under the influence of temperature change, the largest CV for sulfur content was recorded for Chaetoceros teres, at 83.95%, and the smallest was recorded for Chaetoceros constrictus, at only 6.14%.

|

Fig. 3 Cell sulfur content of different phytoplankton under four temperatures. |

Table 1 shows the CVs of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur contents in the same phytoplankton cells under different temperatures. Some phytoplankton, such as Chaetoceros constrictus and Chaetoceros debilis, under four temperatures had CVs of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents that were all < 15%, indicating weak variation. Conversely, the CVs of the carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents of Stephanopyxis turris was maximum, indicating strong variation. One of the possible reasons for this finding is that temperature has different effects on the metabolism of different algae, resulting in differences in the CV of the elemental contents. For example, the optimum growth temperature of Prorocentrum dentatum is 22℃; when the temperature is < 22℃, the growth rate increases with an increase in temperature (Chen et al., 2005), and enzyme activity increases, which reduces the phytoplankton's demand for the macromolecules required to achieve a certain growth rate (Armin and Inomura, 2021). When the temperature exceeds 25℃, the growth rate, enzyme activity, and metabolic level decrease, and the weight of macromolecules required to reach a certain growth rate increases. The experimental results showed that the carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents in Prorocentrum dentatum cells were the highest at 15℃, the lowest at 20℃, and increased at 25℃, exhibiting a high- low-high trend with increasing temperature. This result is consistent with the increase and decrease in the demand for macromolecules caused by the increase and decrease in growth rate reported by Chen et al. (2005) and Armin and Inomura (2021), which revealed that metabolism can change the cell content of elements. Another possible reason for this finding is that temperature has different effects on phytoplankton cell volume (Stramski et al., 2002; Lassen et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2018). Cell volume change significantly affected the carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents in phytoplankton. For some algae, such as Akashiwo sanguinea and Stephanopyxis palmeriana, the effect of temperature on sulfur was stronger than that on carbon and nitrogen. In the cells of these phytoplankton species, the sulfur content may be more easily affected by temperature changes.

Some studies reported that the cellular carbon and nitrogen contents of phytoplankton exhibit a U-shaped trend with increasing temperature (Goldman and Joel, 1977; Harris et al., 1986; Thompson et al., 1992). That is, at lower and higher temperatures, the carbon and nitrogen contents of phytoplankton cells are higher than those of phytoplankton cells at intermediate temperatures. According to our experimental results, the changes in carbon and nitrogen exhibited high similarity. Among the 20 considered species of phytoplankton, the cellular carbon and nitrogen contents of nine species of phytoplankton exhibited a U-shaped pattern. The U-shaped trend accounted for 40% of the sulfur content. Karlodinium veneficum and Prorocentrum dentatum exhibited a U-shaped trend in carbon and nitrogen contents; however, no such trend was observed in the change of sulfur; Helicotheca tamesis exhibited the opposite trend. The carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents in some phytoplankton, such as Chaetoceros pseudocurvisetus, exhibited a wavy trend with increasing temperature; therefore, the response of phytoplankton contents to temperature change exhibited a polymorphic trend, which is similar to the research results reported by Thompson et al. (1992).

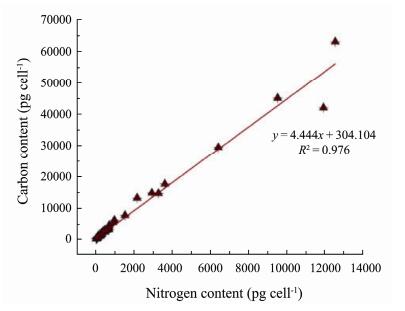

4.2 C: N Ratio of PhytoplanktonIn the samples of 20 species of phytoplankton under the four temperatures, we found that the C: N ratio ranged from 3.50 (Coscinodiscus wailesii at 25℃) to 8.97 (Chaetoceros pseudocurvisetus at 15℃). The CV ranged from 0.04% (Stephanopyxis turris at 15℃ and Chaetoceros castracanei at 25℃) to 20.20% (Coscinodiscus granii at 25℃). We observed a significant linear relationship between single-cell carbon content and cell nitrogen content (Prism9 P < 0.0001): C = 4.444 × N + 307.104, with a correlation coefficient R2 of 0.976 (Fig.4).

|

Fig. 4 Relationship between the carbon and nitrogen contents of phytoplankton cells. |

In ecological stoichiometry, organisms are distinguished by their elemental composition, because the composition of different elements is adapted to its ecological functions (Klausmeier et al., 2004; Chen, 2021). At present, global environmental change is becoming increasingly intense, and environmental factors are changing the structure and function of the ecosystem by affecting stoichiometry (Marcos et al., 2021). Therefore, changes in the C: N ratio of phytoplankton are important in studies of the marine food web and the response of the ocean to these global changes.

Table 2 lists the plankton carbon nitrogen ratios of historical data. Our experiments showed that the C: N ratio fluctuated in the range of 3.50 – 8.97, and the average C: N ratio was 5.52, which is close to the C: N ratio in the stoichiometric formula of marine phytoplankton described by Dyrssen (1977). The variability in phytoplankton cell C: N ratio is the result of biochemical resource allocation of different growth strategies (Martiny et al., 2013), which is indicated by the differences in the contents of nitrogen-containing organic macromolecules, inorganic nitrogen salts (nitrates), and energy storage substances (starch or triglyceride) (Geider and LaRoche, 2002). Redfield reported a C: N ratio of 6.6 that typically occurs when phospholipids, proteins, and nucleic acids account for 5% – 15%, 45%, and 10% of the cell mass, respectively. C: N > 12 is an extreme value, which only occurs when the protein content drops below 25% of the cell mass (Geider and LaRoche, 2002). A low protein content affects the growth and reproduction of phytoplankton, resulting in its inability to survive for a long time. Therefore, the carbon-to-nitrogen ratio of phytoplankton fluctuates within a certain range but with minimal disparity.

|

|

Table 2 Stoichiometry formulas of marine plankton and the C: N: S ratio in historical data |

The taxonomic status of phytoplankton and its cytochemical ratio can affect the properties of phytoplankton, such as edible and nutritional quality. When the C: N ratio of phytoplankton increases, the herbivorous efficiency of zooplankton and the efficiency of energy transfer to a higher trophic level are reduced (Kwiatkowski et al., 2018), which increase the possibility of organic carbon entering the deep sea for storage (Armin and Inomura, 2021). In recent years, global warming has become increasingly severe. By the end of the 21st century, the global temperature is expected to rise by 2–6℃ (Trisos et al., 2020). This increase in temperature will affect the stoichiometry ratio of phytoplankton. The results of this study showed that the cell C: N ratio of some phytoplankton, such as Stephanopyxis turris, Stephanopyxis palmeriana and Coscinodiscus granii, increases with the increase in temperature, which is conducive to carbon deposition. At the same time, temperature change will significantly affect the phytoplankton community structure. Given these effects on the phytoplankton community structure and C: N ratio, it is important to estimate the global marine carbon budget (Lomas et al., 2021).

4.3 Nitrogen Content of PhytoplanktonWe selected fourteen kinds of phytoplankton to measure their nitrogen content per unit cytoplasmic volume at the temperature at which they grow vigorously to obtain the nitrogen content. The cytoplasmic volume of a single cell refers to Sun Jun's research (Sun, 1999). The nitrogen content per unit cytoplasmic volume is the content of nitrogen in a single cell divided by the cytoplasmic volume of a single cell (Table 3).

|

|

Table 3 Nitrogen content per unit cytoplasmic volume of different phytoplankton |

For nitrophilic species, we proposed a possible discrimination basis, that is, we believe that phytoplankton with high content of nitrogen in unit cytoplasm have higher demand for nitrogen, which can be considered as nitrophilic species.

The results showed that the nitrogen content per unit cytoplasmic volume of Helicotheca tamesis, Rhizosolenia setigera, Pseudo-nitzschia pungens, and Skeletonema costatum was high. A previous study reported that Skeletonema costatum and Pseudo-nitzschia pungens are chain nitrophilic diatoms (Chen et al., 2017), which is consistent with our result that the nitrogen content per unit cytoplasmic volume of Skeletonema costatum and Pseudo- nitzschia pungens in this study was high. We speculate that Helicotheca tamesis and Rhizosolenia setigera are nitrophilic species. Nitrophilic species have a high demand for nitrogen, whereas non-nitrophilic species have a relatively low demand for nitrogen. An obvious positive correlation exists between Bacillaria paxillifera and the concentration of nitrogen nutrients, and the nitrogen content per unit cytoplasmic volume is close to that of Skeletonema costatum. Therefore, we speculate that Bacillaria paxillifera is also a nitrophilic species. A high nitrogen content in the environment can lead to eutrophication. Inferring nitrophilic species based on the nitrogen content per unit cytoplasmic volume of phytoplankton has considerable practical value.

With the increase of temperature, marine phytoplankton tend to have a high nitrogen phosphorus ratio, so the demand for nitrogen increases (Toseland et al., 2013). Because nitrogen is the limiting factor in seawater, with global warming, it will limit the growth and reproduction of phytoplankton with high cell nitrogen content. The results of this experiment show that phytoplankton with large cell volume has high content of cell nitrogen. When the temperature rises, it is not conducive to the survival of phytoplankton with large cell volume. This is consistent with the conclusion that future climate warming will be more conducive to the survival of small phytoplankton communities (Marinov et al., 2010; Morán et al., 2010; Dutkiewicz et al., 2013; Marinov et al., 2013).

4.4 Sulfur Content in Phytoplankton CellsThe marine sulfur cycle plays an important role in the global sulfur budget. The transformation of inorganic sulfur into organic sulfur in water is performed by marine plants. Sulfur has an important impact on the structure and function of phytoplankton and marine ecosystems (Jordi et al., 2012).

The results showed that the cell sulfur content in marine phytoplankton was higher than that of cell nitrogen and less than that of cell carbon. These results differ from the historical data (Table 2) because phytoplankton and zooplankton were not distinguished in the ecological stoichiometric formula proposed by Lerman (1979). In Ho et al. (1993), different experimental instruments and different experimental principles led to large differences in experimental results.

In seawater, sulfur exists in large quantities as a major element; thus, phytoplankton absorbs and uses a large amount of sulfur in the environment. Because of the high concentrations of inorganic sulfur in seawater, inorganic sulfur ions in phytoplankton highly contribute to total sulfur. Research showed that when the nitrogen in the environment is limited, the absorption of sulfur by phytoplankton accelerates (Stefels, 2000). In seawater, nitrogen typically becomes the limiting factor for phytoplankton growth, which may lead to a high sulfur content in phytoplankton cells. To adapt to the lower nitrogen and higher sulfur levels in seawater, phytoplankton may have formed a unique nitrogen and sulfur absorption and use system in the long-term evolution process to meet their needs for growth and reproduction. Therefore, the sulfur content in marine phytoplankton cells is higher than nitrogen.

Our findings showed a positive correlation between carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents and the cell volume of phytoplankton, particularly when the volume difference was relatively large. However, we found no strict positive correlation between cell element contents and cell volume. For example, the volume of Stephanopyxis turris is larger than that of Akashiwo sanguinea, but the carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents in its cells were lower than those of Akashiwo sanguinea, which may be related to the cellular structure and ecological characteristics of the species.

Environmental factors are have important impacts on the contents of elements in phytoplankton cells, and temperature affects the energy storage of phytoplankton by changing the metabolism of phytoplankton, which in turn affects a series of biochemical compositions of phytoplankton, and the contents of cellular elements change accordingly (Martiny et al., 2013). In addition to temperature, light, and nutrients, other environmental factors also significantly affect the carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents in cells. For example, in a certain range of light intensity, the carbon and nitrogen contents of phytoplankton cells increases with increasing light intensity, and when nutrients are limited in the environment, the metabolism and the contents of carbon and nitrogen in cells decrease.

The contents of cellular elements in phytoplankton also differ in different growth cycles. Moal et al. (1987) found that the contents of carbon and nitrogen in cells decreased gradually with the slowing of growth, and can even be reduced by half from the exponential growth phase to the stationary phase.

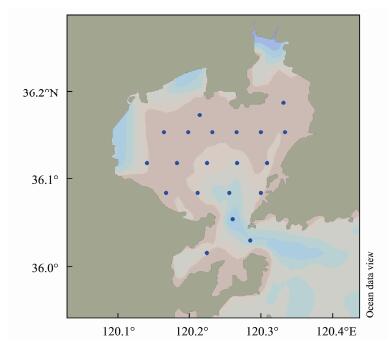

4.6 Phytoplankton Biomass in Jiaozhou BayA total of 20 large surface stations are set up in the sea area of Jiaozhou Bay for phytoplankton sampling, and the station map is shown in Fig.5. The survey time in summer is from September 20 to 21, 2018, and the survey time in autumn is from November 9 to 10, 2018. The sampling tools are shallow water type III plankton net with net mouth area of 0.1 m2 and net mesh of 76 μm and hand- held phytoplankton net with net mouth area of 0.07 m2 and net mesh of 76 μm. The sampling method is one vertical trawl from bottom to surface at each station. The samples were fixed and stored with 5% neutral formalin. The data of the sample comes from our laboratory (Yang et al., 2018). According to the cell concentration of each species, the average water temperature at the sampling time in summer is close to 25℃, and the average water temperature at the sampling time in autumn is close to 15℃. Select the content of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur in a single cell of the detected species at the corresponding culture temperature, and the product of the cell concentration is the content of carbon, nitrogen and sulfur in total phytoplankton.

|

Fig. 5 Location map of phytoplankton sampling station in Jiaozhou Bay in summer and autumn of 2018. |

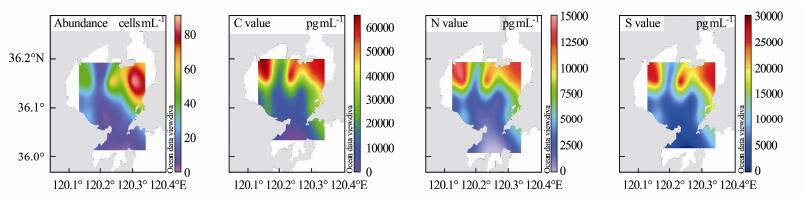

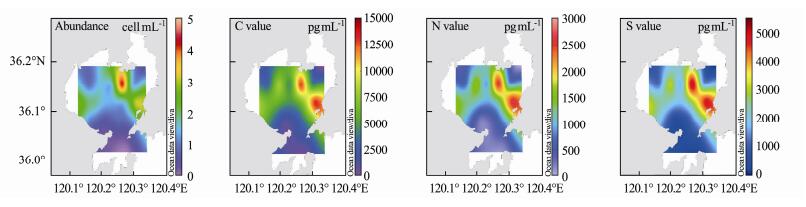

According to the conversion results, the maximum carbon content of phytoplankton in summer is close to 60000 pg mL−1, the maximum nitrogen content is approach to 150000 pg mL−1, and the maximum sulfur content is approximated to 30000 pg mL−1. In the autumn voyage, the maximum carbon content is close to 15000 pg mL−1, the maximum nitrogen content is approach to 3000 pg mL−1, and the maximum sulfur content is approximated to 5000 pg mL−1. Therefore, the phytoplankton biomass in summer is much higher than that in autumn.

In our study of phytoplankton in Jiaozhou Bay in the summer and autumn of 2018, we found that water temperature was one of the most important variables. We selected a culture temperature close to the average water temperature in summer and autumn, and drew the cell carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur content plane distribution map according to the element contents of phytoplankton (Figs.6 and 7). Comparing the cell abundance and cell carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur content plane distribution maps of phytoplankton in summer and autumn, we found the cell abundance and element contents in summer were higher than in autumn. The maximum cell abundance of phytoplankton in summer was approximately sixteen times higher than that in autumn, whereas the maximum element content was only four times higher than that in autumn. One of the reasons for the difference in biomass expressed by cell abundance and biomass expressed by element content is that compared to autumn, the water temperature in summer is significantly higher. Some phytoplankton in the sea, such as Rhizosolenia setigera and Helicotheca tamesis, have higher cell element contents at low than at high water temperatures. Another reason is that some species with high cell element contents, such as Coscinodiscus spp., appear more frequently in autumn than in summer; however, the number of phytoplankton with high element contents is far less than that of the dominant species. Therefore, their contribution to cell abundance is minimal, but their contribution to marine carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents cannot be ignored.

|

Fig. 6 Horizontal distribution of phytoplankton cell abundance and phytoplankton cell carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents in Jiaozhou Bay in summer 2018. |

|

Fig. 7 Horizontal distribution of phytoplankton cell abundance and phytoplankton cell carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents in Jiaozhou Bay in autumn 2018. |

From the plane distribution of element contents and the corresponding cell abundance, we found differences between the high-value area of cell abundance and the high-value area of cell elements. In the investigation of phytoplankton in summer, the northwest of Jiaozhou Bay did not have abundant phytoplankton cells, but its element contents were high. This is because there are Coscinodiscus wailesii and Odontella regia in this area. Although their cell abundance accounted for only 1.68% of the total at this site, the relative element content was as high as 58.43%. In the northeast of Jiaozhou Bay, although the cell abundance was high, the content of phytoplankton elements in the northeast was lower than in the northwest because the region was dominated by Skeletonema costatum and Chaetoceros curvisetus, which have a low cell element content.

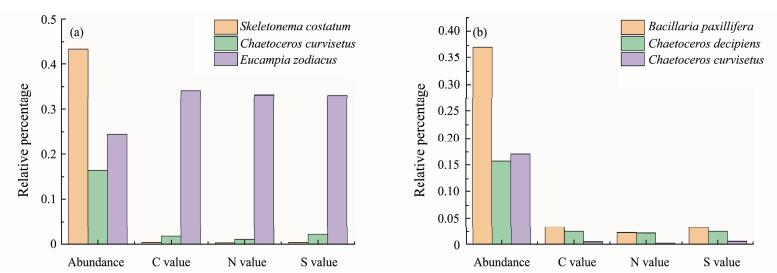

According to Fig.8, which depicts the relative percentage diagram of cell abundance and element contents of the dominant phytoplankton species in Jiaozhou Bay in summer and autumn of 2018, among the dominant species in summer (Fig.8a), the relative percentage of cell abundance of Skeletonema costatum was much higher than that of Eucampia zodiacus and Chaetoceros curvisetus, while the relative element content was much lower than that of Eucampia zodiacus and slightly less than that of Chaetoceros spinosus. This is because the elemental content of a single cell of Skeletonema costatum is approximately two orders of magnitude lower than that of Chaetoceros curvisetus and three orders of magnitude lower than that of Eucampia zodiacus. Among the dominant species in autumn (Fig.8b), the relative percentage of cell abundance of Bacillaria paxillifera was higher than that of Chaetoceros curvisetus and Chaetoceros decipiens. In terms of the element content of a single cell, that of Bacillaria paxillifera is higher than that of Chaetoceros curvisetus and lower than that of Chaetoceros decipiens. Combined with the cell abundance and element content of single cells, we found that the relative percentage of element content of the Bacillaria paxillifera population in the survey area was higher than that of the other two dominant species.

|

Fig. 8 Cell abundance and relative percentage of carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents of the dominant phytoplankton dominant species in Jiaozhou Bay in summer (a) and autumn (b) of 2018. |

In investigations of phytoplankton community structure, it is reasonable to express phytoplankton biomass and select dominant species in combination with cell abundance and element content. The combination of the two can more accurately describe the contribution of phytoplankton communities to marine biomass, energy flow, and material cycles from the perspective of population, and considers the large volume of some cells and the role of populations with high or low element contents in marine ecosystems. The expression of biomass by element content can further describe the basis of the internal energy change in the transformation of phytoplankton community structures between the seasons.

5 ConclusionsIn this study, we measured the cell carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur contents of 20 phytoplankton species at four temperatures. The results showed that temperature affected the cell element contents of phytoplankton, with different degrees of influence. Although the C: N ratio of phytoplankton varied, it did not change drastically with species differences or temperature changes. The nitrogen content per unit cytoplasmic volume of phytoplankton during vigorous growth can provide a basis for inferring nitrophilic species. The cell sulfur content of these phytoplankton species is higher than the cell nitrogen content but less than the cell carbon content, which may be an evolutionary characteristic of phytoplankton that helped them to adapt to the marine environment, which has less nitrogen and more sulfur. This is important to the regulation of the marine sulfur cycle. Large differences exist in the phytoplankton biomass expressed by phytoplankton cell abundance and the element content. The combination of the two can accurately reflect the contribution of various groups to biomass and energy distribution and can be used to comprehensively define the dominant species.

AcknowledgementsThis study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China – Shandong Joint Foundation (No. U1806211).

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China – Shandong Joint Foundation (No. U1806211).

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China – Shandong Joint Foundation (No. U1806211).

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China – Shandong Joint Foundation (No. U1806211).

Anderson, S. I., Barton, A. D., Clayton, S., Dutkiewicz, S., and Rynearson, T. A., 2021. Marine phytoplankton functional types exhibit diverse responses to thermal change. Nature Communications, 12(1): 1-9. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-26651-8 (  0) 0) |

Arandia-Gorostidi, N., Weber, P. K., Alonso-Sáez, L., Morán, X., and Mayali, X., 2016. Elevated temperature increases carbon and nitrogen fluxes between phytoplankton and heterotrophic bacteria through physical attachment. The ISME Journal, 11(3): 641-650. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2016.156 (  0) 0) |

Armin, G., and Inomura, K., 2021. Modeled temperature dependencies of macromolecular allocation and elemental stoichiometry in phytoplankton. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 19: 5421-5427. DOI:10.1016/j.csbj.2021.09.028 (  0) 0) |

Berman, T., and Bronk, D., 2003. Dissolved organic nitrogen: A dynamic participant in aquatic ecosystems. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 31(3): 279-305. DOI:10.3354/ame031279 (  0) 0) |

Bronk, D. A., See, J. H., Bradley, P., and Killberg, L., 2007. DON as a source of bioavailable nitrogen for phytoplankton. Biogeosciences, 4(3): 283-296. DOI:10.5194/bg-4-283-2007 (  0) 0) |

Buchanan, P. J., Aumont, O., Bopp, L., Mahaffey, C., and Tagliabue, A., 2021. Impact of intensifying nitrogen limitation on ocean net primary production is fingerprinted by nitrogen isotopes. Nature Communications, 12(1): 1-9. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-26552-w (  0) 0) |

Chen, X., and Chen, H. Y. H., 2021. Plant mixture balances terrestrial ecosystem C: N: P stoichiometry. Nature Communications, 12(1): 1-9. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-24889-w (  0) 0) |

Chen, Y., Liu, J. J., Gao, Y. X., Shou, L., and Jiang, Z. B., 2017. Seasonal variation and the factors on net-phytoplankton in Sanmen Bay. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 48(1): 101-112. DOI:10.11693/hyhz20160700153 (  0) 0) |

Diaz, B. P., Knowles, B., Johns, C. T., Laber, C. P., Bondoc, K. G. V., Haramaty, L., et al., 2021. Seasonal mixed layer depth shapes phytoplankton physiology, viral production, and accumulation in the North Atlantic. Nature Communications, 12(1): 1-16. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-26836-1 (  0) 0) |

Dutkiewicz, S., Scott, J. R., and Follows, M. J., 2013. Winners and losers: Ecological and biogeochemical changes in a warming ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 27: 463-477. DOI:10.1002/gbc.20042 (  0) 0) |

Dyrssen, D., 1977. The chemistry of plankton production and decomposition in seawater. Oceanic Sound Scattering Prediction, 5: 65-84. (  0) 0) |

Fernández-Martínez, M., Preece, C., Corbera, J., Cano, O., Garcia-Porta, J., Sardans, J., et al., 2021. Bryophyte C: N: P stoichiometry, biogeochemical niches and elementome plasticity driven by environment and coexistence. Ecology Letters, 24(7): 1375-1386. DOI:10.1111/ele.13752 (  0) 0) |

Fletcher, S. E. M., Gruber, N., Jacobson, A. R., Doney, S. C., Dutkiewicz, S., Gerber, M., et al., 2006. Inverse estimates of anthropogenic CO2 uptake, transport, and storage by the ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 20(2): GB2002. DOI:10.1029/2005GB002530 (  0) 0) |

Geider, R. J., and LaRoche, J., 2002. Redfield revisited: Variability of C: N: P in marine microalgae and its biochemical basis. European Journal of Phycology, 37: 1-17. DOI:10.1017/S0967026201003456 (  0) 0) |

Goldman, J. C., 1977. Temperature effects on phytoplankton growth in continuous culture. Limnology and Oceanography, 22(5): 932-936. DOI:10.4319/lo.1977.22.5.0932 (  0) 0) |

Gruber, N., Clement, D., Carter, B. R., Feely, R. A., van Heuven, S., Hoppema, M., et al., 2019. The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 from 1994 to 2007. Science, 363(6432): 1193-1199. DOI:10.1126/science.aau5153 (  0) 0) |

Harrison, P. J., Zingone, A., Mickelson, M. J., Lehtinen, S., Ramaiah, N., Kraberg, A. C., et al., 2015. Cell volumes of marine phytoplankton from globally distributed coastal data sets. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 162: 130-142, DOI: 10.1016/j.ecss.2015.05.026.

(  0) 0) |

Harrs, R. P., Samain, J. F., Moal, J., Martin-Jézéquel, V., and Poulet, S. A., 1986. Effects of algal diet on digestive enzyme activity in calanus helgolandicus. Marine Biology, 90(3): 353-361. DOI:10.1007/BF00428559 (  0) 0) |

Henson, S. A., Cael, B. B., Allen, S. R., and Dutkiewicz, S., 2021. Future phytoplankton diversity in a changing climate. Nature Communications, 12(1): 1-8. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-25699-w (  0) 0) |

Ho, T. Y., Quigg, A., Finkel, Z. V., Milligan, A. J., Wyman, K., Falkowski, P. G., et al., 2003. The elemental composition of some marine phytoplankton. Journal of Phycology, 39: 1145-1159. DOI:10.1111/j.0022-3646.2003.03-090.x (  0) 0) |

Huang, Y., Liu, X., Laws, E. A., Chen, B., Li, Y., Xie, Y., et al., 2018. Effects of increasing atmospheric CO2 on the marine phytoplankton and bacterial metabolism during a bloom: A coastal mesocosm study. The Science of the Total Environment, 633: 618-629. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.03.222 (  0) 0) |

Klausmeier, C., Litchman, E., Daufresne, T., and Levin, S. A., 2004. Optimal nitrogen-to-phosphorus stoichiometry of phytoplankton. Nature, 429: 171-174. DOI:10.1038/nature02454 (  0) 0) |

Kwiatkowski, L., Aumont, O., Bopp, L., and Ciais, P., 2018. The impact of variable phytoplankton stoichiometry on projections of primary production, food quality, and carbon uptake in the global ocean. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 32(4): 516-528. DOI:10.1002/2017GB005799 (  0) 0) |

Lassen, M. K., Nielsen, K. D., Richardson, K., Garde, K., and Schlüter, L., 2010. The effects of temperature increases on a temperate phytoplankton community – A mesocosm climate change scenario. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 383(1): 79-88. DOI:10.1016/j.jembe.2009.10.014 (  0) 0) |

Laufkötter, C., Vogt, M., Gruber, N., Aita-Noguchi, M., Aumont, O., Bopp, L., et al., 2015. Drivers and uncertainties of future global marine primary production in marine ecosystem models. Biogeosciences, 12(23): 6955-6984. DOI:10.5194/bg-12-6955-2015 (  0) 0) |

Lerman, A., 1979. Geochemical Processes: Water and Sediment Environments. Wiley-Interscience, New York, 1-481.

(  0) 0) |

Lomas, M. W., Baer, S. E., Mouginot, C., Terpis, K. X., Lomas, D. A., Altabet, M. A., et al., 2021. Varying influence of phytoplankton biodiversity and stoichiometric plasticity on bulk particulate stoichiometry across ocean basins. Communications Earth and Environment, 2(1): 1-10. DOI:10.1038/s43247-021-00212-9 (  0) 0) |

Marinov, I., Doney, S. C., and Lima, I. D., 2010. Response of ocean phytoplankton community structure to climate change over the 21st century: Partitioning the effects of nutrients, temperature and light. Biogeosciences, 7(12): 3941-3959. DOI:10.5194/bg-7-3941-2010.doi: (  0) 0) |

Marinov, I., Doney, S. C., Lima, I. D., Lindsay, K., Moore, J. K., and Mahowald, N., 2013. North-south asymmetry in the modeled phytoplankton community response to climate change over the 21st century. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 27(4): 1274-1290. DOI:10.1002/2013GB004599 (  0) 0) |

Martiny, A. C., Pham, C., Primeau, F. W., Vrugt, J. A., Moore, J. K., Levin, S. A., 2013. Strong latitudinal patterns in the elemental ratios of marine plankton and organic matter. Nature Geoscience, 6(4): 279-283. DOI:10.1038/NGEO1757 (  0) 0) |

McCain, J. S. P., Tagliabue, A., Susko, E., Achterberg, E. P., Allen, A. E., and Bertrand, E. M., 2021. Cellular costs underpin micronutrient limitation in phytoplankton. Science Advances, 7(32): eabg6501. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.abg6501 (  0) 0) |

Moal, J., Martin-Jézéquel, V., Harris, R. P., Samain, J. F., and Poulet, S. A., 1987. Interspecific and intraspecific variability of the chemical composition of marine phytoplankton. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 10(3): 339-346. DOI:10.1016/0025-3227(87)90091-0 (  0) 0) |

Morán, X. A. G., Lopez-urrutia, A., Calvo-diaz, A., and Li, W. K. W., 2010. Increasing importance of small phytoplankton in a warmer ocean. Global Change Biology, 16(3): 1137-1144. (  0) 0) |

Parsons, T. R., Takahashi, M., and Hargrave, B., 1984. Biological Oceanographic Processes. 3rd edition, Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1-34.

(  0) 0) |

Quere, C. L., Rdenbeck, C., Buitenhuis, E. T., Conway, T. J., and Heimann, M., 2008. Saturation of the southern ocean CO2 sink due to recent climate change. Science, 316(5832): 1735-1738. DOI:10.1126/science.1136188 (  0) 0) |

Reed, G. F., Lynn, F., and Meade, B. D., 2003. Use of coefficient of variation in assessing variability of quantitative assays. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology, 9(6): 1235-1239. DOI:10.1128/CDLI.10.6.1162.2003 (  0) 0) |

Sardans, J., Rivas-Ubach, A., and Peñuelas, J., 2012. The elemental stoichiometry of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems and its relationships with organismic lifestyle and ecosystem structure and function: A review and perspectives. Biogeochemistry, 111(1): 1-39. DOI:10.2307/23359726 (  0) 0) |

Stefels, J., 2000. Physiological aspects of the production and conversion of DMSP in marine algae and higher plants. Journal of Sea Research, 43(3-4): 183-197. DOI:10.1016/S1385-1101(00)00030-7 (  0) 0) |

Stramski, D., Sciandra, A., and Claustre, H., 2002. Effects of temperature, nitrogen, and light limitation on the optical properties of the marine diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana. Limnology and Oceanography, 47(2): 392-403. DOI:10.4319/lo.2002.47.2.0392 (  0) 0) |

Sun, J., and Liu, D. Y., 1999. Study on phytoplankton biomass I.Phytoplankton measurement biomass from cell volume or plasma volume . Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2: 75-85. (  0) 0) |

Sun, J., Liu, D. Y., and Qian, S. B., 2000. Study on phytoplankton biomass II.Net-phytoplankton measurement biomass estimated from the cell volume in the Jiaozhou Bay. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 22(1): 102-109. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0253-4193.2000.01.012 (  0) 0) |

Sunda, W., Kieber, D. J., Kiene, R. P., and Huntsman, S., 2002. An antioxidant function for DMSP and DMS in marine algae. Nature, 418(6895): 317-320. DOI:10.1038/nature00851 (  0) 0) |

Thompson, P. A., Guo, M. X., Harrison, P. J., and Whyte, J. N. C., 1992. Effect of variation of temperature II.On the biochemical composition of species of marine phytoplankton. Journal of Phycology, 28(4): 488-497. DOI:10.1111/j.0022-3646.1992.00488.x (  0) 0) |

Toseland, A., Daines, S. J., Clark, J. R., Kirkham, A., Strauss, J., Uhlig, C., et al., 2013. The impact of temperature on marine phytoplankton resource allocation and metabolism. Nature Climate Change, 3(11): 979-984. DOI:10.1038/nclimate1989 (  0) 0) |

Trisos, C. H., Merow, C., and Pigot, A. L., 2020. The projected timing of abrupt ecological disruption from climate change. Nature, 580: 496-501. DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-2189-9 (  0) 0) |

Verity, P. G., Robertson, C. Y., Tronzo, C. R., Andrews, M. G., Nelson, J. R., and Sieracki, M. E., 1992. Relationships between cell volume and the carbon and nitrogen content of marine photosynthetic nanoplankton. Limnology and Oceanography, 37: 1434-1446. DOI:10.4319/lo.1992.37.7.1434 (  0) 0) |

Wan, X. S., Sheng, H. X., Dai, M., Zhang, Y., Shi, D., Trull, T. W., et al., 2018. Ambient nitrate switches the ammonium consumption pathway in the euphotic ocean. Nature Communications, 9(1): 915. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-03363-0 (  0) 0) |

Yang, R., Chen, S., Zhang, X., Su, R., Zhang, C., Liang, S., et al., 2021. Influences of the hydrophilic components of two anthropogenic dissolved organic nitrogen groups on phytoplankton growth in Jiaozhou Bay, China. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 169 (3): 1-13, DOI: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112551.

(  0) 0) |

Yang, S. M., Liu, R. X., and Chen, W. Q., 2020. The phytoplankton community in Jiaozhou Bay in 2018. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 50(9): 72-80. DOI:10.16441/j.cnki.hdxb.0200112 (  0) 0) |

Zaiss, J., Boyd, P. W., Doney, S. C., Havenhand, J. N., and Levine, N. M., 2021. Impact of Lagrangian sea surface temperature variability on southern ocean phytoplankton community growth rates. Global Biogeochemical Cycles, 35(8): 1-16. DOI:10.1029/2020GB006880 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, C. B., Ling, W. Z., Yuan, Z. M., and Xiang, L. R., 2005. Effects of temperature and salinity on growth of Prorocentrum dentatum and comparisons between growths of Prorocentrum dentatum and Skeletonema costatum. Advances in Marine Science, 23(1): 60-64. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-647.005.01.008 (  0) 0) |

2023, Vol. 22

2023, Vol. 22