2) University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China;

3) Center for Ocean Mega-Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China;

4) Laboratory for Ocean and Climate Dynamics, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266237, China;

5) Numerical Simulation Division, North China Sea Marine Forecasting Center of State Oceanic Administration, Qingdao 266000, China

Storm surge is typically defined as the abnormal rise of water over and above the predicted astronomical tide after a storm, usually a typhoon (Yang et al., 2002). Coastal inundation occurs when high tide levels formed by spring tides pile up with the peak storm surge higher than the dike elevation, and dike breaking may occur during extreme sea state conditions. These physical processes can cause huge losses of lives and properties, and coastal regions are expected to be increasingly vulnerable to storm surge inundation in the coming decades because of acceleration in sea level rise (Sweet et al., 2017). In addition, typhoon intensities are expected to increase in a warming climate (Chen et al., 2017). Therefore, reliable estimates of storm surge inundation are important for damage assessment (Schubert et al., 2015). Hydrodynamic models are useful in elucidating the inundation process under the combined impacts of storm surge and typhoon waves (Kumar et al., 2008). Extreme sea levels induced by historical storms need to be quantified to enhance the understanding of storm surge and wave hazards and consequently improve the preparation for and response to coastal inundation.

Many studies focused on coastal storm surge inundation (Lin et al., 2010; Niedoroda et al., 2010). Sha et al. (2007) improved the Princeton Ocean Model (POM) with dynamic boundary conditions and applied it to study the inundation area under storm surge in the coastal area of Tianjin. Results show that the original POM can be revised to a numerical model with dynamic boundary conditions for shallow water area research. Wu et al. (2012) studied the influence of the Wenzhou coastal dike in China on storm surge inundation. They used a high-resolution numerical model that is based on an unstructured grid and can calculate the overflow discharge during storm surge inundation. Results show that the coastal dike in Wenzhou enhances the menace of storm surge and inundation in the city. He et al. (2015) assessed the inundation risk of storm surge along the Putuo Coast, eastern China by using a high-resolution ADCIRC model. The results of inundation risk assessment indicate that when the peak storm surge is superimposed on the high astronomical tide, the main urban area of Putuo would be largely flooded because of the low elevation of Putuo Coastal areas. However, these studies did not consider the presence of a dike for the numerical simulation of coastal inundation. In general, waves largely contribute to storm surge and coastal inundation, but their effects differ in various regions (Marsooli and Lin, 2018). Many studies focused on the contribution of wave radiation stress and wave setup to storm surge; however, little is known about the effects of wave-enhanced bottom stress, which may be significant in shallow waters during storm surge inundation (Wu et al., 2018).

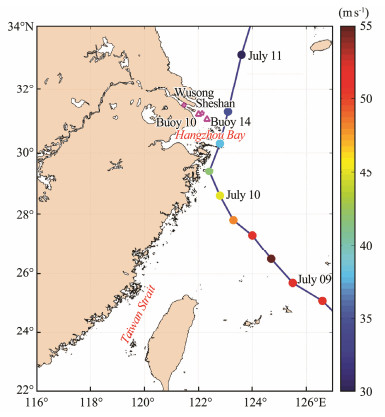

In the present study, we developed a high-resolution coastal inundation model for the southwestern shore of Hangzhou Bay (Fig.1). The model considers the coupling effect of typhoon wind-wave on storm surge inundation in the presence of dike. The study aimed to understand the evolution of storm surge inundation considering dike overflowing and dike breaking. Typhoon waves can affect storm surge and inundation through three mechanisms, namely, wave-enhanced sea surface wind stress, wave-enhanced bottom stress, and wave radiation stress. The coupling effect of wind-wave on inundation risk was illustrated in the model sensitivity analysis. The effects of dike height and breach length on inundation were also quantitatively assessed. The numerical simulation method and validation are presented in Section 2. The results are analyzed and the inundation progression is discussed in Section 3. The conclusions are presented in Section 4.

|

Fig. 1 Track of typhoon Chan-hom (blue line) at 6 h intervals and locations of the observation stations: wave buoys (pink triangles) and tide gauge stations (pink dots). |

For the storm surge simulation, the ADCIRC numerical model was used with the highest resolution, approximately 50 m, along the coast of Hangzhou Bay. According to Yin et al. (2016), the resolution has a major effect on the calculated inundation time series. The ADCIRC model was developed by Luettich and Westerink (2007). Primitive equations were formulated using traditional hydrostatic pressure and Boussinesq approximations (Yang et al., 2019). Its 2D version solves the nonlinear momentum and continuity equations in the time domain. ADCIRC uses the finite element method that provides flexibility to resolve the complex geometry and bathymetry of the coastal area. Furthermore, the model avoids the spurious oscillations associated with the primitive Galerkin finite element formulation of the continuity equation by solving the generalized wave continuity equation. These governing equations are presented in Eqs. (1)–(3) (Ebersole et al., 2010):

| $\frac{{\partial \eta }}{{\partial t}} + \frac{{\partial Hu}}{{\partial x}} + \frac{{\partial Hv}}{{\partial y}} = 0, $ | (1) |

| $\frac{{{\rm{d}}u}}{{{\rm{d}}t}} = fv - g\frac{{\partial \left[ {\eta + \frac{{{p_A}}}{{g{\rho _0}}}} \right]}}{{\partial x}} + \frac{{{\tau _{sx}} - {\tau _{bx}}}}{{{\rho _0}H}} + \frac{{{M_x}}}{H}, $ | (2) |

| $\frac{{{\rm{d}}v}}{{{\rm{d}}t}} = - fu - g\frac{{\partial \left[ {\eta + \frac{{{p_A}}}{{g{\rho _0}}}} \right]}}{{\partial y}} + \frac{{{\tau _{sy}} - {\tau _{by}}}}{{{\rho _0}H}} + \frac{{{M_y}}}{H}, $ | (3) |

where t represents time; (u, v) are the current velocity components in the x and y directions, respectively; η is the free surface elevation; f is the Coriolis parameter; g is the acceleration of gravity; PA is the atmospheric pressure at the sea surface; ρ0 is the water reference density; H = h + η is the total water depth; h is the unperturbed water depth; (Mx, My) are the horizontal momentum diffusion terms; (τsx, τsy) are the surface stresses; and (τbx, τby) are the bottom stresses.

When the water level is higher than the land elevation, overflow and inundation occur. The ADCIRC model uses Henderson's classical hydraulic formula to calculate spill-way discharge.

| $Q = {C_m}\frac{2}{3}\sqrt {2g} {h_1}^{\frac{2}{3}}, $ | (4) |

where Q represents spillway discharge, h1 represents the height above seawall, and g represents the acceleration of gravity. Cm represents discharge coefficient.

| ${C_m} = 0.611\left[ {{{(1 + \frac{{v_1^2}}{{2g{h_1}}})}^{3/2}} - {{(\frac{{v_1^2}}{{2g{h_1}}})}^{3/2}}}, \right]$ | (5) |

where v1 represents the current velocity.

The time step of the model was 2 s, and the initial condition was η = u = v = 0. The input to ADCIRC included the topography and bathymetry on an unstructured grid (finite element grid) and the spatial distributions of the wind velocity vector and pressure gradient, as well as the wind stress and the boundary conditions. The boundary normal velocity was 0, and the model was driven by the harmonic constant of the eight major astronomical tides (M2, S2, N2, K2, K1, O1, P1, and Q1) from the Oregon State University Tidal Prediction Software at the open boundary (Martin et al., 2009). A detailed description of the ADCIRC model can be found in its user manual (http://adcirc.org/home/documentation/users-manual-v52/).

2.1.2 Wave modelWe selected the third-generation wave model Simulating WAves Nearshore (SWAN). SWAN was developed by researchers at the Technical University of Delft in The Netherlands. It has been widely used in the coastal engineering and science community. The SWAN model is formulated in terms of wave action density for convenient modeling of the wave-current interaction. The numerical model outputs the spatial evolution of the wave energy spectra in the frequency and direction domains. The physical processes modeled by the SWAN model include wave refraction and shoaling, wave–current interaction, and energy dissipation owing to wave breaking and bottom shear stress (Booij et al., 1999). In Cartesian coordinates, the governing equation is expressed as

| $\frac{{\partial N}}{{\partial t}} + \frac{\partial }{{\partial x}}{C_x}N + \frac{\partial }{{\partial y}}{C_y}N + \frac{\partial }{{\partial \sigma }}{C_\sigma }N + \frac{\partial }{{\partial \theta }}{C_\theta }N = \frac{{{S_{tot}}}}{\sigma }, $ | (6) |

where (x, y) represent the horizontal Cartesian coordinates; σ is the intrinsic angular frequency; θ is the propagation direction of each wave component; Cx, Cy, Cσ and Cθ are the energy propagation speeds in the x-, y-, σ-, and θ-spaces, respectively; and N denotes the wave action density defined as

| $N\left({\sigma, \theta } \right) = E\left({\sigma, \theta } \right)/\theta, $ | (7) |

where E represents the wave energy density. On the right-hand side of Eq. (6), Stot represents the sources and sinks, including the energy input from wind and energy dissipation caused by wave breaking and bottom friction, and the cross-spectral energy transfer.

The time step was 30 min for the SWAN model, and the initial water level was 0 m. The wave spectrum was resolved between 0.03 and 1.42 Hz in frequency and from 0° to 360° in angle at angular increments of 10°. The model considers the physical processes of wind input, white-cap dissipation, three wave interactions, four wave interactions, diffraction, bottom friction, and shallow water breaking dissipation.

2.1.3 ADCIRC–SWAN coupled modelWe used the coupled model developed by Dietrich et al. (2012); ADCIRC obtained the wave parameters and radiation stress gradients from SWAN. The radiation stress gradients are expressed mathematically as

| ${\tau _{sx, {\rm{waves}}}} = - \frac{{\partial {S_{xx}}}}{{\partial x}} - \frac{{\partial {S_{xy}}}}{{\partial y}}, $ | (8) |

| ${\tau _{sy, {\rm{waves}}}} = - \frac{{\partial {S_{xy}}}}{{\partial x}} - \frac{{\partial {S_{yy}}}}{{\partial y}}, $ | (9) |

where Sxx, Sxy, and Syy are the wave radiation stresses (Longuet-Higgins and Stewart, 1962).

In this study, the calculation method below was adopted to consider the effect of wave–current interaction on bottom stress τb:

| ${\tau _{bx}} = {f_c}\rho \left| {{U_c}} \right|{u_c} + \frac{\rho }{2}{f_w}\left| {{U_w}} \right|{u_w} + \frac{{4\rho }}{{\rm{ \mathsf{ π} }}}\sqrt {{f_c}{f_w}} \left| {{U_c}} \right|{u_w}, $ | (10) |

| ${\tau _{by}} = {f_c}\rho \left| {{U_c}} \right|{v_c} + \frac{\rho }{2}{f_w}\left| {{U_w}} \right|{v_w} + \frac{{4\rho }}{{\rm{ \mathsf{ π} }}}\sqrt {{f_c}{f_w}} \left| {{U_c}} \right|{u_w}, $ | (11) |

| ${U_c} = \sqrt {u_c^2 + v_c^2}, $ | (12) |

| ${U_w} = \sqrt {u_w^2 + v_w^2}, $ | (13) |

where ρ is the water density, fc is the bottom drag coefficient relating to current, Uc is the average current speed, and fw is the bottom drag coefficient relating to wave. Uw is the near-bottom wave orbital speed; (uc, vc) are the current velocity components in the x and y directions, respectively; and (uw, vw) are the near-bottom wave orbital velocity components in the x and y directions, respectively. A detailed description of the formula can be found in the study by Wang et al. (2007).

The formula of sea surface wind stress τ is as follows:

| $\tau = {\rho _a}{C_D}\left| {{U_{10}}} \right|{U_{10}}, $ | (14) |

where CD is the wind drag coefficient, ρa is the air density, and U10 is the wind speed at 10 m elevation.

The drag coefficient is related to the sea surface roughness. Thus, the sea state-dependent formula proposed by Donelan et al. (1993) was used to investigate the effect of wind–wave on surface roughness.

| ${C_D} = {\left({\frac{\kappa }{{\ln 10 - \ln {Z_0}}}} \right)^2}, $ | (15) |

where к is the Kalman constant with a value of 0.4, and Z0 is the sea surface roughness. The value of CD is limited to 0.0025 when the wind speed exceeds 33 m s−1 (Donelan et al., 2004).

| ${Z_0} = 3.7 \times {10^{ - 5}}\frac{{u_{10}^2}}{g}{\left({\frac{{{u_{10}}}}{{{C_p}}}} \right)^{0.9}}, $ | (16) |

where g is the acceleration of gravity, and Cp is the wave velocity corresponding to the spectral peak frequency. SWAN provides spectral peak frequency ωp at data exchange moment. In the iterative computation using dispersion relation

| ${\omega ^2} = \left({gk} \right)\tanh \left({kh} \right), $ | (17) |

Cp can be calculated as

| ${C_p} = \frac{{{\omega _p}}}{{{k_p}}}, $ | (18) |

where kp is the wave number.

SWAN was used to obtain the water level and current field data from ADCIRC and incorporate them into the wave-action-density-spectrum balance equation to calculate the wave parameters at each data exchange. The time interval of the data exchange between the two models was 30 min, the same as that used in SWAN, and the output was calculated hourly. SWAN and ADCIRC were driven by the same wind field data. The wind and pressure fields of typhoons in this work were reconstructed on the basis of the Jelesnianski model (Jelesnianski, 1965). The central pressure and position data were retrieved from the China Meteorological Administration tropical cyclone database (Ying et al., 2014) (http://tcdata.typhoon.org.cn). The simulation period was set to 5 d, from July 7, 2015 12:00 UTC to July 12, 2015 12:00 UTC. The numerical model may behave stochastically; thus, the found differences between the different simulations may be by chance (Büchmann and Söderkvist, 2016; Tang et al., 2019). We repeated all simulations with 2 days earlier and compared the results between the two identical simulations. The results were slightly different, but the variability was negligible. Due to space constraints, the simulation results of another group of control experiments are not shown in the paper.

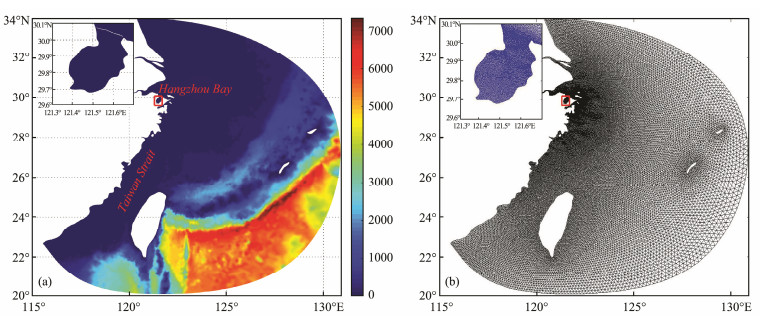

2.2 Simulations of Typhoon Chan-Hom 2.2.1 Domain and meshThe mesh was created by the Surface Water Modeling System software containing 73674 nodes and 143224 elements. The element size varied from 30 km in the deep areas to 200 m near the shore and 30 m inside Hangzhou Bay (Fig.2). The model domain was 20°–34°N, 115°–131°E. The quality of simulation results depends largely on the accuracy of the input data (Schubert and Sanders, 2012). The bathymetry data were obtained from two sources: from the coast down to 100 m depth, charted depths were digitalized at 1:150000 and 1:1000000 scales. The remaining data were obtained from the Global Seafloor Database from ETOPO1 (U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration; https://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/global/global.html). Fine shoreline details and elevation data were obtained from high-resolution satellite sensing data provided by the Chinese Academy of Sciences Computer Network Information Center (http://www.gscloud.cn/).

|

Fig. 2 (a) Bathymetric contours and (b) grid domain and unstructured triangular grid used in the ADCIRC/SWAN modeling. |

The inputs for both models must be the same to compare the effects of waves on inundation. Hence, the coupled and uncoupled models used the same non-structured meshes with triangular elements and the same astronomical and meteorological forcing in parallel computing, which reduced time cost interpolating and avoided cumulative errors between different grids.

2.2.2 Design of numerical experimentsThe coupling effects of wind-wave and the influence of dike height and dike breach length on coastal inundation were studied by performing several control numerical experiments using the parameters shown in Table 1. In EXP3, the individual and combined effects of wave-enhanced bottom stress, wave-enhanced wind stress, and wave radiation stress were investigated.

|

|

Table 1 Design parameters of numerical experiments |

The accuracy of the hydrodynamic simulation results was validated by comparing with the observed significant wave height and water level. The measurement points in the model were set at the locations of the wave buoys and tide gauge stations from which the observations were obtained (Fig.1 and Table 2).

|

|

Table 2 Information on the wave buoy and tide gauge stations |

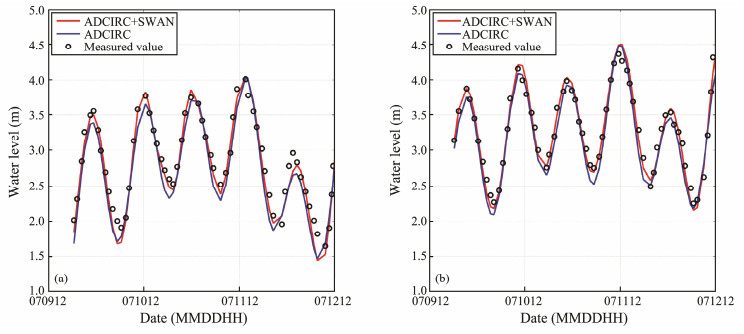

The simulation results (Fig.3) agree well with the observation values. The simulated water level of both models corresponds well with the observation value of the tide gauges, indicating that the model can objectively reflect the progress of the storm surge during typhoon Chan-hom. The fully coupled model presents better results, indicating that the simulation results clearly improved when the wind-wave effect was considered.

|

Fig. 3 Simulated and measured water level at (a) Wusong and (b) Sheshan. |

The root mean square errors (RMSE in Eq. (19)) of the data are summarized in Table 3.

|

|

Table 3 Comparison of root mean square error (RMSE) for the simulated and measured water levels between coupled and uncoupled models |

| $RMSE = \sqrt {\frac{1}{n}{{\sum\limits_{i = 1}^n {\left({{y_i} - {x_i}} \right)} }^2}}.$ | (19) |

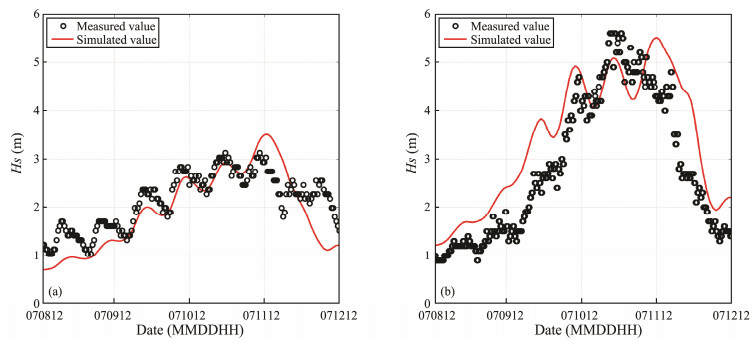

The measured significant wave height and simulated significant wave height are shown in Fig.4. The simulated significant wave height agree well with the observed values both at Buoy 10 and Buoy 14. Effect of water level on wave height in shallow water region was captured well by the coupled model, thus the coupled model accurately reflected the development and evolution process of the typhoon waves during typhoon Chan-hom along the coast of Zhejiang Province.

|

Fig. 4 Simulated and measured (a) significant wave heights at Buoy 10, (b) significant wave heights at Buoy 14. |

The southeast coastal region of China is frequently impacted by typhoon storm surge on average six times a year. Typhoon Chan-hom was one of the most powerful typhoons ever recorded in the East China Sea. As generated in the northwestern Pacific Ocean on June 30, 2015, it entered the East China Sea on July 10. Typhoon Chanhom caused severe damage in Zhejiang Province on 11 July, and the highest instantaneous wind speed recorded reached 58 m·s−1. The typhoon destroyed 111 sections of dike over a distance of 29.57 km, which caused significant storm surge inundation. The following is the analysis of simulation results of coastal inundation during typhoon Chan-hom.

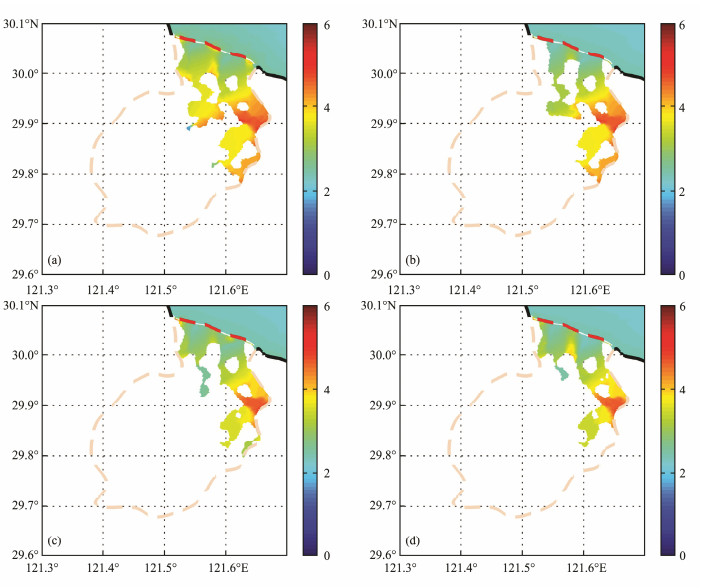

The maximum inundation area for different dike heights is presented in Fig.5. As expected, the inundation area clearly decreases with increasing dike height. The model shows that the inundation area reaches 49 km2 at a dike height of 1 m, and it quickly decreases to 35 and 26 km2 at dike heights of 2 and 3 m, respectively. No inundation occurs at a dike height of 4 m.

|

Fig. 5 Maximum inundation extent and water level simulated for different dike heights (a) 1 m (b) 2 m (c) 3 m (d) 3 m without coupling the waves. The red dotted line represents the dike, the dike length is 14 km. |

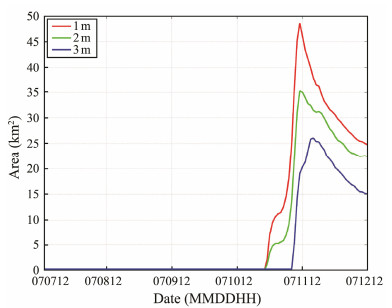

The variations of inundation area for the different dike heights are given in Fig.6. The overflow occurs earlier for a lower dike height. The maximum inundation area generally occurs simultaneously with the maximum sea level at dike heights of 1 and 2 m. However, an interesting feature occurs at a dike height of 3 m, which is the maximum inundation area lag of the maximum sea level. This result may be explained by the fact that the water flow over land would not stop immediately when the overflow disappears. As a result, a lag of maximum inundation area with respect to the maximum sea level occurs toward higher dike height.

|

Fig. 6 Time series of maximum inundation area obtained from simulations for different dike heights. |

The results from the coupled and uncoupled models were compared to evaluate the effects of wind-wave on inundation. The uncoupled results are given in Fig.5(d). The comparison of maximum inundation area is given in Fig.7. The wind-wave coupling effects were considered in terms of wave-enhanced bottom stress, wave-enhanced wind stress, radiation stress, and combined action of these three stresses. The wave can enhance the bottom stress, which reduces the current speed and surge height. For storms traveling at slow translation speeds or nearly parallel to the coast, wave-enhanced bottom stress combined with longer forcing duration in such storms can cause less inundation (Wu et al., 2018). Bottom stress mainly affects shallow water areas, but wind stress affects the whole computational domain, and it exerts the greatest effect on storm surge inundation. When both are considered simultaneously, the effects of wave-enhanced bottom stress and wave-enhanced wind stress can counteract each other, and the maximum inundation extent does not vary noticeably compared with the case that considers only the effect of radiation stress. The contribution of wave setup to the storm surge has been widely reported. Wave setup is not only related to wave parameters and topography but also varies with the change in amplitude and phase of the tide (Poulose et al., 2018). It is highly significant to storm surge inundation. The full coupling effect is not a linear superposition of each coupling effect alone, and the possible reason could be stochastic variations ('noise'; see Tang et al., 2019).

|

Fig. 7 Time series of maximum inundation area – comparison between coupled and uncoupled models. |

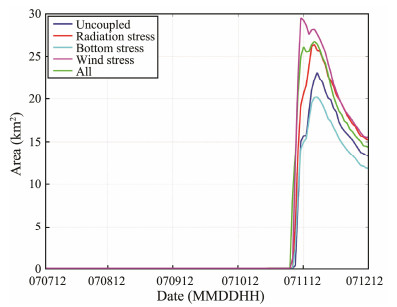

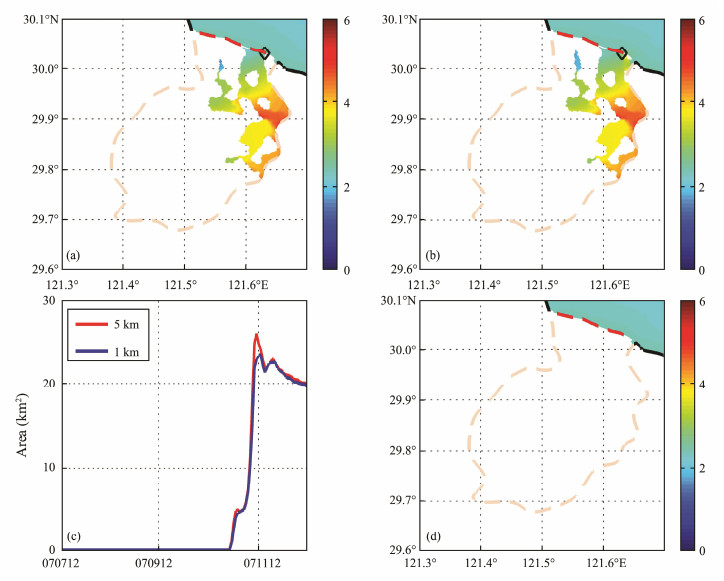

The dike breaking cases were simulated at a dike height of 4 m, excluding the impact of dike overflow. We considered two breach lengths: 1 and 5 km. Considering the topography, we set the breach on the right side of the dike (black diamond in Fig.8) to allow the seawater to overflow the land. The variations in the inundation area are illustrated in Fig.8(c). The maximum inundation area is 23 km2 at a breach length of 1 km and is increased by 13% to 26 km2 at a breach length of 5 km. The variations in inundation area closely follow each other except at the local peak. This result indicates that the inundation is insensitive to the dike breach length when the overflow is small and that the maximum inundation area increases with breach length.

|

Fig. 8 Maximum inundation area induced by storm surge at different breach lengths (a) 1 km; (b) 5 km; (c) time series of inundation area at different breach lengths; (d) maximum inundation extent with no breach when the dike height is 4 m. |

The storm surge inundation during typhoon Chan-hom in the southwestern Hangzhou Bay region was investigated. A tightly coupled model of ADCIRC+SWAN was used to simulate the dike overflowing and dike breaking cases considering different dike heights and breach lengths. The hydrodynamic simulations of the coupled model were validated by comparing with measured data from wave buoys and tide gauges. The coupling of the wind-wave with storm surge can efficiently intensify the inundation, and the wave-enhanced bottom stress can reduce the surge height nearshore. Wind stress exerts a greater effect on storm surge inundation than bottom stress and radiation stress. When both are considered simultaneously, the effects of wave-enhanced bottom stress and wave-enhanced wind stress can counteract each other, and the maximum inundation area does not vary noticeably compared with the case that only considers the effect of radiation stress. The contribution of wave setup to storm surge has been widely reported, and it is highly significant to storm surge inundation. The results highlight the necessity of incorporating wave effects in the accurate simulation of storm surge inundation. For dike overflowing cases, the dike height plays a key role because it not only determines the magnitude of maximum inundation area but also changes the phases of inundation. A higher dike results in a smaller maximum inundation area and introduces a lag of maximum inundation area with respect to the maximum sea level in front of the dike. For dike breaking cases, the maximum inundation area increases with the breach length, implying that the dike breach length should be considered in accurate inundation simulation.

This study only considers idealized dike conditions. The results may serve as a useful reference in marine disaster prevention and mitigation. In real cases, the simulation of storm surge inundation would be much more complex because real multiple dike breaches and their lengths and land roughness properties should be considered. Moreover, further studies should consider the impact of typhoon wind properties (including various typhoon intensity and tracks) on storm surge inundation.

AcknowledgementsThis work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Nos. 2016YFC140 2000, 2016YFC1401002, and 2018YFC1407003), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Nos. U1706216, 41606024, and 41506023), the CAS (Chinese Academy of Sciences) Strategic Priority Project (No. XDA 19060202), the CAS Innovative Foundation (No. CXJJ-16M111), the NSFC Innovative Group (No. 41421005), and the NSFC-Shandong Joint Fund for Marine Science Research Centers (No. U1406402). The numerical work is supported by High Performance Computing Center, Institution of Oceanology, CAS. The data set is provided by Marine Scientific Data Center, Institute of Oceanology, CAS.

Booij, N., Ris, R. C. and Holthuijsen, L. H., 1999. A third-generation wave model for coastal regions: 1. Model description and validation. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 104(C4): 7649-7666. (  0) 0) |

Büchmann, B. and Söderkvist, J., 2016. Internal variability of a 3-D ocean model. Tellus A: Dynamic Meteorology and Oceanography, 68(1): 30417. DOI:10.3402/tellusa.v68.30417 (  0) 0) |

Chen, X., Zhang, X., Church, J. A., Watson, C. S., King, M. A., Monselesan, D., Legresy, B. and Harig, C., 2017. The increasing rate of global mean sea-level rise during 1993–2014. Nature Climate Change, 7(7): 492-495. DOI:10.1038/nclimate3325 (  0) 0) |

Dietrich, J. C., Tanaka, S., Westerink, J. J., Dawson, C. N., Luettich, R. A., Zijlema, M., Holthuijsen, L. H., Smith, J. M., Westerink, L. G. and Westerink, H. J., 2012. Performance of the Unstructured-Mesh, SWAN+ADCIRC Model in computing hurricane waves and surge. Journal of Scientific Computing, 52(2): 468-497. DOI:10.1007/s10915-011-9555-6 (  0) 0) |

Donelan, M. A., Dobson, F. W., Smith, S. D. and Anderson, R. J., 1993. On the dependence of sea surface roughness on wave development. Journal of Physical Oceanography, 23(9): 2143-2149. DOI:10.1175/1520-0485(1993)023<2143:OTDOSS>2.0.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Donelan, M. A., Haus, B. K., Reul, N., Plant, W. J., Stiassnie, M., Graber, H. C., Brown, O. B. and Saltzman, E. S., 2004. On the limiting aerodynamic roughness of the ocean in very strong winds. Geophysical Research Letters, 31(18): 355-366. (  0) 0) |

Ebersole, B. A., Westerink, J. J., Bunya, S., Dietrich, J. C. and Cialone, M. A., 2010. Development of storm surge which led to flooding in St. Bernard Polder during hurricane Katrina. Ocean Engineering, 37(1): 91-103. (  0) 0) |

He, P., Zuo, J., Gu, Y., Zhang, B., Kang, X. and Zhang, H., 2015. Inundation risk assessment of storm surge along Putuo cosatal areas. Transactions of Oceanology and Limnology, 2015(1): 1-8 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Jelesnianski, C. P., 1965. A numerical calculation of storm tides induced by a tropical storm impinging on a continental self. Monthly Weather Review, 93: 343-358. DOI:10.1175/1520-0493(1993)093<0343:ANCOS>2.3.CO;2 (  0) 0) |

Kumar, V. S., Babu, V. R., Babu, M. T., Dhinakaran, G. and Rajamanickam, G. V., 2008. Assessment of storm surge disaster potential for the Andaman Islands. Journal of Coastal Research, 24(sp2): 171-177. DOI:10.2112/05-0506.1 (  0) 0) |

Lin, N., Emanuel, K. A., Smith, J. A. and Vanmarcke, E., 2010. Risk assessment of hurricane storm surge for New York City. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 115: D18121. DOI:10.1029/2009JD013630 (  0) 0) |

Longuet-Higgins, M. S. and Stewart, R. W., 1962. Radiation stress and mass transport in gravity waves, with application to 'surf-beats'. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 13(4): 481-504. DOI:10.1017/S0022112062000877 (  0) 0) |

Luettich, R., and Westerink, J., 2007. A parallel advanced circulation model for oceanic coastal and estuarine waters. Technical report, available at http://www.adcirc.org.

(  0) 0) |

Marsooli, R. and Lin, N., 2018. Numerical modeling of historical storm tides and waves and their interactions along the U. S. east and gulf coasts. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 123(5): 3844-3874. DOI:10.1029/2017JC013434 (  0) 0) |

Martin, P. J., Smith, S. R., Posey, P. G., Dawson, G. M., and Riedlinger, S. H., 2009. Use of the Oregon State University Tidal Inversion Software (OTIS) to generate improved tidal prediction in the East-Asian seas. Report NRL/MR/7320-09- 9176. Naval Research Laboratory, Stennis Space Center, Bay St. Louis, 29pp.

(  0) 0) |

Niedoroda, A., Resio, D., Toro, G., Divoky, D., Das, H. and Reed, C., 2010. Analysis of the coastal Mississippi storm surge hazard. Ocean Engineering, 37(1): 82-90. DOI:10.1016/j.oceaneng.2009.08.019 (  0) 0) |

Poulose, J., Rao, A. and Bhaskaran, P. K., 2018. Role of continental shelf on non-linear interaction of storm surges, tides and wind waves: An idealized study representing the west coast of India. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 207: 457-470. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2017.06.007 (  0) 0) |

Schubert, C. E., Busciolano, R. J., Hearn Jr., P. P., Rahav, A. N., Behrens, R., Finkelstein, J. S., Monti Jr., J., and Simonson, A. E., 2015. Analysis of storm-tide impacts from hurricane Sandy in New York. US Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report, No. 2015-5036, 75pp.

(  0) 0) |

Schubert, J. E. and Sanders, B. F., 2012. Building treatments for urban flood inundation models and implications for predictive skill and modeling efficiency. Advances in Water Resources, 41: 49-64. DOI:10.1016/j.advwatres.2012.02.012 (  0) 0) |

Sha, R., Yin, B., Yang, D., Xu, Z. and Cheng, M.-H., 2007. A numerical study on storm surge and inundation induced by hurricanes in the nearshore of Tianjin. Marine Sciences, 31(7): 63-67 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Sweet, W., Kopp, R., Weaver, C., Obeysekera, J., Horton, R., Thieler, E., and Zervas, C., 2017. Global and Regional Sea Level Rise Scenarios for the United States. NOAA Technical Report NOS CO-OPS 083. Woods Hole Coastal and Marine Science Center, 55pp.

(  0) 0) |

Tang, S., von Storch, H., Chen, X. and Zhang, M., 2019. 'Noise' in climatologically driven ocean models with different grid resolution. Oceanologia, 61(3): 300-307. DOI:10.1016/j.oceano.2019.01.001 (  0) 0) |

Wang, S., Liang, S. and Sun, Z., 2007. The numerical analysis of wave effects on a tidal current in two dimensions. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 25(3): 371-384 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2009.02.004 (  0) 0) |

Wu, G., Shi, F., Kirby, J. T., Liang, B. and Shi, J., 2018. Modeling wave effects on storm surge and coastal inundation. Coastal Engineering, 140: 371-382. DOI:10.1016/j.coastaleng.2018.08.011 (  0) 0) |

Wu, W., Fu, C., Yu, F. and Liu, Q., 2012. Numerical simulation of the influence of Wenzhou coastal dike on storm surge inundation. Journal of Marine Sciences, 30(2): 36-42 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Yang, S. L., Zhao, Q. Y. and Belkin, I. M., 2002. Temporal variation in the sediment load of the Yangtze River and the influences of human activities. Journal of Hydrology, 263(1-4): 56-71. DOI:10.1016/S0022-1694(02)00028-8 (  0) 0) |

Yang, W., Yin, B., Feng, X., Yang, D., Gao, G. and Chen, H., 2019. The effect of nonlinear factors on tide-surge interaction: A case study of typhoon Rammasun in Tieshan Bay, China. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 219: 420-428. DOI:10.1016/j.ecss.2019.01.024 (  0) 0) |

Yin, J., Lin, N. and Yu, D., 2016. Coupled modeling of storm surge and coastal inundation: A case study in New York City during hurricane Sandy. Water Resources Research, 52(11): 8685-8699. DOI:10.1002/2016WR019102 (  0) 0) |

Ying, M., Zhang, W., Yu, H., Lu, X., Feng, J., Fan, Y., Zhu, Y. and Chen, D., 2014. An overview of the China Meteorological Administration tropical cyclone database. Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology, 31: 287-301. DOI:10.1175/JTECH-D-12-00119.1 (  0) 0) |

2020, Vol. 19

2020, Vol. 19