Analytical and Experimental Research on Wave Scattering by an Open-Type Rectangular Breakwater with Horizontal Perforated Plates

1 Introduction

The open-type breakwater supported by piles belongs to an environmentally friendly coastal structure, and it is characterized by good seawater exchange capacity, low requirements for seabed conditions, and low engineering cost. It also has good application prospects and important research significance. A common approach to improving the shielding effect of the open-type breakwater is increasing the width and draft of the structure. However, this method substantially increases the wave force of the breakwater and the cost of engineering (Dai et al., 2018). Developing an open-type breakwater with a simple shape but a good wave defense effect for longer waves remains challenging and interesting.

Partially immersed rectangular boxes can serve as a simple and efficient open-type breakwater and have been applied in practical engineering projects (Katoh, 1992; Nguyen et al., 2020). Mei and Black (1969) examined water wave scattering through the box-type breakwater fixed near the free surface on the basis of the matched eigenfunction expansion method, and they verified their solutions with the experimental results of Kincaid (1960). Hwang and Tang (1986) conducted theoretical and experimental studies on water wave transmission and wave spectrum variation by a rectangular breakwater fixed on the surface. According to their research, breakwaters may effectively shield against short waves if their width-to-wavelength ratio and submergence depth-to-water depth ratio are at least 0.4 and 0.3, respectively. Soylemez and Goren (2003) established an analytical solution of oblique wave diffraction by the fixed rectangular box on water free surface. They then compared their solution with the numerical results of Bai (1975) and the experiment data of Lebreton and Margnac (1966). Manuel (1997) and Williams (1998) measured the reflection and transmission coefficients for a pile-supported rectangular breakwater through tests.

In addition to rectangular boxes, horizontal perforated plates have been proposed as a simple breakwater with good wave-sheltering effect and seawater exchange capacity (Okubo et al., 1994; Kweon et al., 2012). Compared with horizontal solid plate breakwaters, horizontal perforated plates not only increase wave energy dissipation on the plate because of their porosity but also considerably decrease the vertical wave force, so they may have a superior engineering application promise. Kakuno and Zhong (1993) studied the wave prevention capability of a submerged horizontal perforated plate using the matched asymptotic expansion method and experimental tests. Yu and Chwang (1994) proposed a linear pressure drop condition for submerged horizontal perforated plates based on potential theory and examined the motion of waves on the plate through the boundary element method (BEM). Chwang and Wu (1994) considered the scattering of waves by the submerged perforated disk as well as used the matching eigenfunction expansion method to address a 3D water wave problem. Yu (1995) introduced a perforated wall effect parameter to the pressure loss condition on a perforated plate and validated this boundary condition using experimental data. This parameter takes into account the inertial and resistance effects of the perforated wall. Liu and Li (2011) proposed a new analytical solution for normally incident waves over an underwater horizontal perforated plate using the velocity potential decomposition method. This approach avoids the need to solve the complex wave dispersion equation in the fluid domain occupied by the plate. Using a similar method, Cho and Kim (2013) researched the diffraction of oblique waves through the horizontal perforated plate and conducted corresponding physical model tests. He et al. (2021) formulated the analytical solution for oblique waves interacting with an underwater horizontal perforated plate breakwater, which used the quadratic pressure drop boundary condition instead of the plate. Their findings indicate that the transmission coefficient is reduced as the plate submerge depth decreases and that the majority of wave energy is effectively dissipated when the porosity is around 0.1. He et al. (2022) introduced the quadratic pressure drop condition for a horizontal perforated plate fixed on the water surface. They also investigated the wave protection behavior of the plate through an analytical solution and experimental tests. Other studies related to the horizontal plate include the underwater horizontal perforated thick plate (Neves et al., 2000; Liu et al., 2012a), multi-layer horizontal perforated plates (e.g., Liu et al., 2008, 2012b; Kee, 2009; Cho et al., 2013; Liu and Li, 2014; Fang et al., 2017, 2018; Hu et al., 2019), and a perforated plate joined to the vertical wall (e.g., Wu et al., 1998; Molin, 2001; Park et al., 2005; Cho and Kim, 2008; Yueh and Chuang, 2009; He et al., 2020; Poguluri and Cho, 2021).

From the above research, rectangular boxes and horizontal perforated plates with simple shapes have been used as efficient open-type breakwaters. However, relevant research on whether combining the two structures to form a new breakwater can have a better wave protective effect seems lacking. At present, some scholars have optimized the structure of rectangular box-type breakwaters based on their wave dissipation mechanism and proposed attaching solid plates to the rectangular boxes to enhance their wave block performance by widening or deepening the breakwater. Ikeno et al. (1988) proposed a new breakwater design featuring twin buoyancy boxes and a pressurized air chamber. They demonstrated that this breakwater design provides superior wave protection compared with the conventional rectangular breakwater. Ikesue et al. (2002) conducted physical model tests and numerical simulations to investigate the novel floating breakwater with two boxes and fins. Wang et al. (2010) carried out model tests to study the wave attenuation performance and heave response of a breakwater by affixing one or two horizontal plates beneath the floating box. Zhang et al. (2018) researched the wave dissipation characteristic of the inverted π-type breakwater through the CFD method and concluded that the viscous effects of horizontal plates substantially affect wave dissipation. Liu et al. (2019) modeled waves interacting with a rectangular-winged floating breakwater by employing the smoothed particle hydrodynamics method.

Based on previous research, this study introduces a novel open-type breakwater design, which incorporates two horizontal perforated plates fixed on the water surface to either side of the box. These plates increase wave dissipation by dissipating and reflecting wave energy, thereby improving the wave resistance behavior of conventional box-type breakwaters. The analytical solution for oblique waves interacting with the breakwater is developed to validate the effectiveness of this new breakwater. The corresponding experimental tests are conducted. The influence of waves and structural parameter changes on hydrodynamic quantities on the breakwater is explored, providing effective guidance for engineering applications.

The next section formulates boundary value problems for oblique waves interacting with open-type rectangular breakwater equipped with horizontal perforated plates, wherein quadratic pressure drop conditions are applied to the perforated plates. Section 3 derives an analytical solution using a combination of the velocity potential decomposition method, an iterative algorithm, and a matching eigenfunction expansion method. Section 4 presents the experimental procedure and outcomes. Convergence examination of the analytical solutions is conducted in Section 5, wherein the experimental data and an iterative BEM solution are compared with the predictions of the analytical solutions. Section 6 uses additional analytical solution cases to discuss the influence of various waves and structure sizes on the hydrodynamic characteristics of novel breakwater. The major results of the research are summarized in the concluding section.

2 Mathematical Formulations

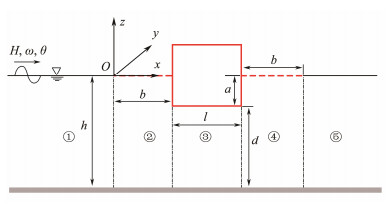

The action of oblique waves on an open-type rectangular breakwater with two horizontal perforated plates is sketched in Fig.1. The red solid line represents a box-type breakwater, whereas the red dotted line represents the horizontal perforated plates. The 3D Cartesian coordinate system is specified for the mathematic description, with the origin fixed at the left end of the left horizontal perforated plate. The x-axis and z-axis extend horizontally to the right and vertically upwards in positive directions, respectively. The angular frequency of the small amplitude incident wave is ω, the height is H, the wavelength is L, and the angle with the positive x-axis is θ. Hence, the component of wavenumber k0 along x- and y-directions are represented by k0x = k0cosθ and k0y = k0sinθ. The width of the horizontal perforated plates is the same and represented by b, whereas the width of the box-type breakwater is represented by l. The breakwater with submerged depth a is situated in an ocean with invariable depth h, resulting in the distance between the seabed and breakwater given by d (d = h − a). The horizontal perforated plate thickness is presumed zero because it is too small to compare with the incident wavelengths and water depths. The length of a breakwater in the y-direction is assumed to be unbounded, as it is quite large relative to the wavelength. The entire fluid field is divided into five sub-domains from left to right, as shown in Fig.1. Sub-domain 1 is the fluid field located on the left side of the whole breakwater, sub-domain 2 is the fluid field beneath the left horizontal perforated plate, sub-domain 3 is the fluid field beneath the box, sub-domain 4 is the fluid field under the right horizontal perforated plate, and sub-domain 5 is the fluid field on the right side of the whole breakwater.

Assuming the fluid has irrotational motion and is both inviscid and incompressible, the fluid motion can be described using velocity potential Φ(x, y, z, t), where t denotes time. The velocity potential for obliquely incident waves may be further formulated like Φ(x, y, z, t) = $\text{Re} [\phi (x, {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} z){{\text{e}}^{{ \text{i}}{k_{0y}}y}}{{\text{e}}^{ - { \text{i}}\omega t}}]$, where Re[] indicates the real part of the value, ϕ(x, z) indicates the complex spatial velocity potential, and $ { \text{i}} = \sqrt { - 1} $.

The modified Helmholtz equation is satisfied by each sub-regional complex spatial velocity potential, and the subscript j is used to indicate the velocity potential of sub-domain j.

|

$ \frac{{{\partial ^2}{\phi _j}(x, z)}}{{\partial {x^2}}} + \frac{{{\partial ^2}{\phi _j}(x, z)}}{{\partial {z^2}}} - k_{0y}^2{\phi _j}(x, z) = 0, {\text{ }}j = 1, {\text{ }}2, {\text{ }}3, {\text{ }}4, {\text{ }}5 . $

|

(1) |

Each sub-domain velocity potential should meet the corresponding boundary conditions, including water surface, seabed, impermeable body surface, and far fields.

|

$ \frac{{\partial {\phi _j}}}{{\partial z}} = K{\phi _j}, K = \frac{{{\omega ^2}}}{g}, z = 0, j = 1, 5, $

|

(2) |

|

$ \frac{{\partial {\phi _j}}}{{\partial z}} = 0, z = −h, j = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, $

|

(3) |

|

$ \frac{{\partial {\phi _2}}}{{\partial x}} = 0, x = b, −a ≤ z ≤ 0, $

|

(4) |

|

$ \frac{{\partial {\phi _3}}}{{\partial z}} = 0, b ≤ x ≤ b + l, z = −a, $

|

(5) |

|

$ \frac{{\partial {\phi _4}}}{{\partial x}} = 0, x = b + l, −a ≤ z ≤ 0, $

|

(6) |

|

$ \mathop {\lim }\limits_{x \to \pm \infty } \left({\frac{\partial }{{\partial x}} \mp { \text{i}}{k_{0x}}} \right)\left({\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

{{\phi _5}} \\

{{\phi _R}}

\end{array}} \right) = 0, $

|

(7) |

where g represents gravitational acceleration, and ϕR represents reflected wave velocity potential.

The following quadratic pressure drop conditions (He et al., 2022) represent the phase change and wave energy dissipation resulting from horizontal perforated plates on a still water surface:

|

$ \begin{array}{r}

\frac{g}{{{\omega ^2}}}\frac{{\partial {\phi _{\text{2}}}}}{{\partial z}} - {\phi _{\text{2}}} = \frac{{8 \text{i} }}{{3{\mathtt{π}}\omega }}\frac{{1 - \varepsilon }}{{2\mu {\varepsilon ^2}}}\left| {\frac{{\partial {\phi _{\text{2}}}}}{{\partial z}}} \right|\frac{{\partial {\phi _{\text{2}}}}}{{\partial z}} + 2C\frac{{\partial {\phi _{\text{2}}}}}{{\partial z}}, \\

z = 0, 0 ≤ x ≤ b,

\end{array}$

|

(8) |

|

$ \begin{array}{r}

\frac{g}{{{\omega ^2}}}\frac{{\partial {\phi _4}}}{{\partial z}} - {\phi _4} = \frac{{8 \text{i} }}{{3{\mathtt{π}}\omega }}\frac{{1 - \varepsilon }}{{2\mu {\varepsilon ^2}}}\left| {\frac{{\partial {\phi _4}}}{{\partial z}}} \right|\frac{{\partial {\phi _4}}}{{\partial z}} + 2C\frac{{\partial {\phi _4}}}{{\partial z}}, \\

z = 0, b + l ≤ x ≤ 2b + l,

\end{array}$

|

(9) |

where ε represents the perforated plate porosity, μ and C respectively denote the discharge and blockage coefficients of the perforated plate. According to previous research, the discharge coefficient μ is obtained from the experimental data. Molin (1993) indicated that the discharge coefficient μ is influenced by the porosity, aperture shape, and Reynolds number. The discharge coefficients μ used in the present study are based on the experimental work by He et al. (2022). Some scholars (Newman, 1969; Mei et al., 1974; Tuck, 1975) discovered that the blockage coefficient C is geometry-dependent. When the porosities of slotted plates are small, their blockage coefficient C can be calculated using the asymptotic analysis method or wave diffraction analysis method. Following the experimental design in Section 4, the value of the blockage coefficient C in this research is determined using an empirical formula derived from Suh et al. (2011), which is:

|

$ C = \frac{\delta }{{2\varepsilon }} . $

|

(10) |

Furthermore, the velocity potentials between adjacent sub-regions must satisfy the matching conditions:

|

$ {\phi _1} = {\phi _2}, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant 0, {\text{ }}x = 0, $

|

(11) |

|

$ \frac{{\partial {\phi _1}}}{{\partial x}} = \frac{{\partial {\phi _2}}}{{\partial x}}, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant 0, {\text{ }}x = 0, $

|

(12) |

|

$ {\phi _2} = {\phi _3}, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant - a, {\text{ }}x = b, $

|

(13) |

|

$ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

{\frac{{\partial {\phi _2}}}{{\partial x}} = 0, {\text{ }}x = b, {\text{ }} - a \leqslant z \leqslant 0} \\

{\frac{{\partial {\phi _2}}}{{\partial x}} = \frac{{\partial {\phi _3}}}{{\partial x}}, {\text{ }}x = b, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant - a}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(14) |

|

$ {\phi _4} = {\phi _3}, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant - a, {\text{ }}x = b + l, $

|

(15) |

|

$ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

{\frac{{\partial {\phi _4}}}{{\partial x}} = 0, {\text{ }}x = b + l, {\text{ }} - a \leqslant z \leqslant 0} \\

{\frac{{\partial {\phi _4}}}{{\partial x}} = \frac{{\partial {\phi _3}}}{{\partial x}}, {\text{ }}x = b + l, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant - a}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(16) |

|

$ {\phi _5} = {\phi _4}, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant 0, {\text{ }}x = 2b + l, $

|

(17) |

|

$ \frac{{\partial {\phi _5}}}{{\partial x}} = \frac{{\partial {\phi _4}}}{{\partial x}}, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant 0, {\text{ }}x = 2b + l . $

|

(18) |

Now, Eqs. (2) – (9) together with (11) – (18) form the complete boundary value problems of scattering for oblique waves with an open-type rectangular breakwater with horizontal perforated plates. The velocity potential decomposition method (Liu and Li, 2011; Liu et al., 2012a) and an iterative algorithm are used to solve the problem in the next section.

3 Iterative Analytical Solution

On the basis of the separating variables method, the complex spatial velocity potentials of sub-domains 2 and 4 are artificially divided into two parts in vertical and horizontal directions, represented by subscripts v and h, respectively:

|

$ {\phi _2} = {\phi _{2, v}} + {\phi _{2, h}}, $

|

(19) |

|

$ {\phi _4} = {\phi _{4, v}} + {\phi _{4, h}} . $

|

(20) |

The modified Helmholtz equation, as well as related boundary equations, are still satisfied by the decomposed velocity potentials.

|

$ \frac{{\partial {\phi _{2, v}}}}{{\partial z}} = 0, {\text{ }}z = 0, {\text{ }}z = - h, $

|

(21) |

|

$ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

{\frac{{\partial {\phi _{2, h}}}}{{\partial x}} = 0, {\text{ }}x = b} \\

{{\phi _{2, h}} = 0, {\text{ }}x = 0} \\

{\frac{{\partial {\phi _{2, h}}}}{{\partial z}} = 0, {\text{ z}} = - h}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(22) |

|

$ \frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, v}}}}{{\partial z}} = 0, {\text{ }}z = 0, {\text{ }}z = - h, $

|

(23) |

|

$ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

{\frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, h}}}}{{\partial x}} = 0, {\text{ }}x = 2b + l} \\

{{\phi _{4, h}} = 0, {\text{ }}x = b + l} \\

{\frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, h}}}}{{\partial z}} = 0, {\text{ z}} = - h}

\end{array}} \right. . $

|

(24) |

Hence, Eqs. (8) – (18) can be reorganized as

|

$ {\phi _1} = {\phi _{2, v}}, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant 0, {\text{ }}x = 0, $

|

(25) |

|

$ \frac{{\partial {\phi _1}}}{{\partial x}} = \frac{{\partial {\phi _{2, v}}}}{{\partial x}} + \frac{{\partial {\phi _{2, h}}}}{{\partial x}}, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant 0, {\text{ }}x = 0, $

|

(26) |

|

$ {\phi _{2, v}} + {\phi _{2, h}} = {\phi _3}, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant - a, {\text{ }}x = b, $

|

(27) |

|

$ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

{\frac{{\partial {\phi _{2, v}}}}{{\partial x}} = 0, {\text{ }}x = b, {\text{ }} - a < z \leqslant 0} \\

{\frac{{\partial {\phi _{2, v}}}}{{\partial x}} = \frac{{\partial {\phi _3}}}{{\partial x}}, {\text{ }}x = b, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant - a}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(28) |

|

$ \begin{array}{r}

\frac{g}{{{\omega ^2}}}\frac{{\partial {\phi _{2, h}}}}{{\partial z}} - ({\phi _{{\text{2, }}v}} + {\phi _{{\text{2, }}h}}) = \frac{{8 \text{i} }}{{3{\mathtt{π}}\omega }}\frac{{1 - \varepsilon }}{{2\mu {\varepsilon ^2}}}\left| {\frac{{\partial {\phi _{2, h}}}}{{\partial z}}} \right|\frac{{\partial {\phi _{2, h}}}}{{\partial z}} + 2C\frac{{\partial {\phi _{2, h}}}}{{\partial z}}, \\

z = 0, {\text{ 0}} \leqslant x \leqslant b,

\end{array}$

|

(29) |

|

$ {\phi _{4, v}} = {\phi _3}, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant - a, {\text{ }}x = b + l, $

|

(30) |

|

$ \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

{\frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, v}}}}{{\partial x}} + \frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, h}}}}{{\partial x}} = 0, {\text{ }}x = b + l, {\text{ }} - a \leqslant z \leqslant 0} \\

{\frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, v}}}}{{\partial x}} + \frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, h}}}}{{\partial x}} = \frac{{\partial {\phi _3}}}{{\partial x}}, {\text{ }}x = b + l, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant - a}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(31) |

|

$ {\phi _5} = {\phi _{4, v}} + {\phi _{4, h}}, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant 0, {\text{ }}x = 2b + l, $

|

(32) |

|

$ \frac{{\partial {\phi _5}}}{{\partial x}} = \frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, v}}}}{{\partial x}}, {\text{ }} - h \leqslant z \leqslant 0, {\text{ }}x = 2b + l, $

|

(33) |

|

$ \begin{array}{r}

\frac{g}{{{\omega ^2}}}\frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, h}}}}{{\partial z}} - ({\phi _{{\text{4, }}v}} + {\phi _{{\text{4, }}h}}) = \frac{{8 \text{i} }}{{3{\mathtt{π}}\omega }}\frac{{1 - \varepsilon }}{{2\mu {\varepsilon ^2}}}\left| {\frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, h}}}}{{\partial z}}} \right|\frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, h}}}}{{\partial z}} + 2C\frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, h}}}}{{\partial z}}, \\

z = 0, {\text{ }}b + l \leqslant x \leqslant 2b + l .

\end{array}$

|

(34) |

Afterward, the velocity potential of sub-domains 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 that meet the above boundary conditions can be written as

|

$ {\phi _1} = \frac{{ - \text{i} gH}}{{2\omega }}\left[ {{\text{e} ^{ \text{i} {k_{0x}}x}}{Z_0}(z) + {R_0}{\text{e} ^{ - \text{i} {k_{0x}}x}}{Z_0}(z) + \sum\limits_{n = 1}^\infty {{R_n}{\text{e} ^{{k_{nx}}x}}{Z_n}(z)} } \right], $

|

(35) |

|

$ {\phi _{2, h}} = \frac{{ - \text{i} gH}}{{2\omega }}\sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {{A_n}{W_n}(x)} \frac{{\cosh {\beta _{nz}}(z + h)}}{{\cosh {\beta _{nz}}h}}, $

|

(36) |

|

$ \begin{aligned}

& {\phi _{2, v}} = \frac{{ - \text{i} gH}}{{2\omega }} \cdot \\

& \left[ {\sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {{B_n}\frac{{\cosh {\mu _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{b}{2}} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)}}{X_n}(z)} {\text{ + }}\sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {{C_n}\frac{{\sinh{\mu _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{b}{2}} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)}}{X_n}(z)} } \right],

\end{aligned}$

|

(37) |

|

$ \begin{aligned}

& {\phi _3} = \frac{{ - \text{i} gH}}{{2\omega }} \cdot \\

& \left[ {\sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {{D_n}\frac{{\cosh {\lambda _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{{2b + l}}{2}} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\lambda _{nx}}l}}{2}} \right)}}{Y_n}(z)} + \sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {{E_n}\frac{{\sinh{\lambda _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{{2b + l}}{2}} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\lambda _{nx}}l}}{2}} \right)}}{Y_n}(z)} } \right],

\end{aligned} $

|

(38) |

|

$ {\phi _{4, h}} = \frac{{ - \text{i} gH}}{{2\omega }}\sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {{F_n}{U_n}(x)} \frac{{\cosh {\beta _{nz}}(z + h)}}{{\cosh {\beta _{nz}}h}}, $

|

(39) |

|

$ \begin{aligned}

& {\phi _{4, v}} = \frac{{ - \text{i} gH}}{{2\omega }} \cdot \\

& \left[ {\sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {{G_n}\frac{{\cosh {\mu _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{{3b}}{2} - l} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)}}{X_n}(z)} + \sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {{H_n}\frac{{\sinh{\mu _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{{3b}}{2} - l} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)}}{X_n}(z)} } \right],

\end{aligned}$

|

(40) |

|

$ {\phi _5} = \frac{{ - \text{i} gH}}{{2\omega }}\left[ {{T_0}{\text{e} ^{ \text{i} {k_{0x}}(x - 2b - l)}}{Z_0}(z) + \sum\limits_{n = 1}^\infty {{T_n}{\text{e} ^{ - {k_{nx}}(x - 2b - l)}}{Z_n}(z)} } \right] . $

|

(41) |

In Eqs. (35) – (41), Rn, An, Bn, Cn, Dn, En, Fn, Gn, Hn, and Tn (n = 0, 1, 2, ···) are unresolved complex expansion coefficients. Zn(z), Wn(z), Xn(z), Yn(z), and Un(z) (n = 0, 1, 2, ···) are the eigenfunctions shown below:

|

$ {Z_0}(z) = \frac{{\cosh {k_0}(z + h)}}{{\cosh {k_o}h}}, $

|

(42a) |

|

$ {Z_n}(z) = \frac{{\cos {k_n}(z + h)}}{{\cos {k_n}h}}, {\text{ }}n = 1, {\text{ }}2, \cdots, $

|

(42b) |

|

$ {W_n}(x) = \cos {\beta _n}(x - b), {\text{ }}n = 0, {\text{ }}1, {\text{ }}2, \cdots, $

|

(43) |

|

$ {X_0}(z) = \frac{{\sqrt 2 }}{2}, $

|

(44a) |

|

$ {X_n}(z) = \cos {\mu _n}(z + h), {\text{ }}n = 1, {\text{ }}2, \cdots, $

|

(44b) |

|

$ {Y_0}(z) = \frac{{\sqrt 2 }}{2}, $

|

(45a) |

|

$ {Y_n}(z) = \cos {\lambda _n}(z + h), {\text{ }}n = 1, {\text{ }}2, \cdots, $

|

(45b) |

|

$ {U_n}(x) = \cos {\beta _n}(x - 2b - l), {\text{ }}n = 0, {\text{ }}1, {\text{ }}2, \cdots . $

|

(46) |

The above eigenfunctions have orthogonality in their respective regions, wherein kn, βn, μn, λn, knx, βnz, μnx, and λnz (n = 0, 1, 2, ···) are the positive eigenvalues that should match the corresponding formulas:

|

$ K = {\omega ^2}/g = {k_0}\tanh ({k_0}h) = - {k_n}\tan ({k_n}h), {\text{ }}n = 1, {\text{ }}2, \cdots, $

|

(47) |

|

$ {\beta _n} = \left({\frac{1}{2}{\mathtt{π}} + n{\mathtt{π}}} \right)/b, {\text{ }}n = 0, {\text{ }}1, {\text{ }}2, \cdots, $

|

(48) |

|

$ {\mu _n} = n{\mathtt{π}}/h, {\text{ }}n = 0, {\text{ }}1, {\text{ }}2, \cdots, $

|

(49) |

|

$ {\lambda _n} = n{\mathtt{π}}/d, {\text{ }}n = 0, {\text{ }}1, {\text{ }}2, \cdots, $

|

(50) |

|

$ {k_{0x}} = \sqrt {k_0^2 - k_{0y}^2}, $

|

(51a) |

|

${k_{nx}} = \sqrt {k_n^2 + k_{0y}^2}, {\text{ }}n = 1, {\text{ }}2, \cdots, $

|

(51b) |

|

$ {\beta _{nz}} = \sqrt {\beta _n^2 + k_{0y}^2}, {\text{ }}n = 0, {\text{ }}1, {\text{ }}2, \cdots, $

|

(52) |

|

$ {\mu _{nx}} = \sqrt {\mu _n^2 + k_{0y}^2}, {\text{ }}n = 0, {\text{ }}1, {\text{ }}2, \cdots, $

|

(53) |

|

$ {\lambda _{nx}} = \sqrt {\lambda _n^2 + k_{0y}^2}, {\text{ }}n = 0, {\text{ }}1, {\text{ }}2, \cdots . $

|

(54) |

Substituting Eqs. (35) – (41) into Eqs. (25) – (34), matching the corresponding eigenfunctions, and using algebraic calculations yield the following:

|

$ [{a_{mn}}]\{ {R_n}\} - \{ {B_m}\} + [{b_{mn}}]\{ {C_m}\} = \{ {\varsigma _m}\}, $

|

(55) |

|

$ \{ {R_m}\} + [c{}_{mn}]\{ A{}_n\} + [d{}_{mn}]\{ B{}_n\} + [e{}_{mn}]\{ C{}_n\} = \{ {\gamma _n}\} \;, $

|

(56) |

|

$\begin{aligned}

& [{f_{mn}}]\{ A{}_n\} + [g{}_{mn}]\{ B{}_n\} + [h{}_{mn}]\{ C{}_n\} + \\

& \{ D{}_m\} + [i{}_{mn}]\{ E{}_m\} = 0,

\end{aligned} $

|

(57) |

|

$ [{j_{mn}}]\{ B{}_m\} + [k{}_{mn}]\{ C{}_m\} + [l{}_{mn}]\{ D{}_n\} + [m{}_{mn}]\{ E{}_n\} = 0, $

|

(58) |

|

$ [{n_{mn}}]\{ A{}_n\} + [o{}_{mn}]\{ B{}_n\} + [p{}_{mn}]\{ C{}_n\} = 0, $

|

(59) |

|

$ \{ {D_m}\} - [i{}_{mn}]\{ E{}_m\} + [g{}_{mn}]\{ G{}_n\} - [h{}_{mn}]\{ H{}_n\} = 0, $

|

(60) |

|

$ \begin{aligned}

& [{m_{mn}}]\{ E{}_n\} - [l{}_{mn}]\{ D{}_n\} + [q{}_{mn}]\{ F{}_n\} - \\

& [j{}_{mn}]\{ G{}_m\} + [k{}_{mn}]\{ H{}_m\} = 0,

\end{aligned}$

|

(61) |

|

$ [{r_{mn}}]\{ F{}_n\} - \{ G{}_m\} - [b{}_{mn}]\{ H{}_m\} + [a{}_{mn}]\{ T{}_n\} = 0, $

|

(62) |

|

$ [{d_{mn}}]\{ G{}_n\} - [e{}_{mn}]\{ H{}_n\} + \{ T{}_m\} = 0, $

|

(63) |

|

$ [{s_{mn}}]\{ F{}_n\} + [t{}_{mn}]\{ G{}_n\} + [u{}_{mn}]\{ H{}_n\} = 0, $

|

(64) |

where the expressions of matrix coefficients are specified in the Appendix, and m, n = 1, 2, 3, ···, N.

Owing to the quadratic pressure drop conditions substituted for the horizontal perforated plates on a still water surface, Eqs. (55) – (64) form a nonlinear equation system that cannot be directly solved. The equation system is solved using an effective iterative algorithm, which draws on the work of An and Faltinsen (2012), Molin and Remy (2013), Liu and Li (2017), and He et al. (2022).

Therefore, the reflection coefficient denoted as CR and transmission coefficient denoted as CT for an open-type rectangular breakwater with two horizontal perforated plates are obtained by

|

$ {C_R} = |{R_0}|, $

|

(65) |

|

$ {C_T} = |{T_0}| . $

|

(66) |

The energy-loss coefficient denoted by CE represents the energy consumption of the incident wave. It is expressed as

|

$ {C_E} = 1 - C_R^2 - C_T^2 . $

|

(67) |

Additionally, the vertical wave force FV and horizontal wave force FH are determined by integrating the dynamic pressure of an entire open-type rectangular breakwater with two horizontal perforated plates.

|

$ \begin{aligned}

{F_V} = & \text{i} \rho \omega \int_0^b {\left[ {{\phi _{2, h}}\left({x, {0^ - }} \right) + {\phi _{2, v}}\left({x, {0^ - }} \right) - \frac{1}{K}\frac{{\partial {\phi _{2, h}}\left({x, {0^ + }} \right)}}{{\partial z}} - \frac{1}{K}\frac{{\partial {\phi _{2, v}}\left({x, {0^ - }} \right)}}{{\partial z}}} \right]{\text{d}}x} + \\

& \text{i} \rho \omega \int_{b + l}^{2b + l} {\left[ {{\phi _{4, h}}\left({x, {0^ - }} \right) + {\phi _{4, v}}\left({x, {0^ - }} \right) - \frac{1}{K}\frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, h}}\left({x, {0^ + }} \right)}}{{\partial z}} - \frac{1}{K}\frac{{\partial {\phi _{4, v}}\left({x, {0^ - }} \right)}}{{\partial z}}} \right]{\text{d}}x} + \text{i} \rho \omega \int_b^{b + l} {\left[ {{\phi _{3, h}}\left({x, - a} \right)} \right]{\text{d}}x} \\

& {\text{ = }}\frac{{\rho gH}}{2}\left[ \begin{array}{l}

\sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {\frac{{{{\left({ - 1} \right)}^n}{A_n}}}{{{\beta _n}}} - \frac{1}{K}\left({\sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {{{\left({ - 1} \right)}^n}\frac{{{\beta _{nz}}}}{{{\beta _n}}}{A_n}\tanh {\beta _{nz}}h} } \right){\text{ + }}\sqrt 2 \frac{{{B_0}}}{{{\mu _{0x}}}}\tanh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{0x}}b}}{2}} \right) + \sum\limits_{n = 1}^\infty {{{\left({ - 1} \right)}^n}\frac{{2{B_n}}}{{{\mu _{nx}}}}\tanh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right){\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} } } \hfill \\

+ \sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {\frac{{{{\left({ - 1} \right)}^n}{F_n}}}{{{\beta _n}}}} - \frac{1}{K}\left({\sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {{{\left({ - 1} \right)}^n}\frac{{{\beta _{nz}}}}{{{\beta _n}}}{F_n}\tanh {\beta _{nz}}h} } \right) + \sqrt 2 \frac{{{G_0}}}{{{\mu _{0x}}}}\tanh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{0x}}b}}{2}} \right) + \sum\limits_{n = 1}^\infty {{{\left({ - 1} \right)}^n}\frac{{2{G_n}}}{{{\mu _{nx}}}}\tanh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)} \hfill \\

+ \sqrt 2 \frac{{{D_0}}}{{{\lambda _{0x}}}}\tanh\left({\frac{{{\lambda _{0x}}l}}{2}} \right) + \sum\limits_{n = 1}^\infty {{{\left({ - 1} \right)}^n}\frac{{2{D_n}}}{{{\lambda _{nx}}}}\tanh\left({\frac{{{\lambda _{nx}}l}}{2}} \right)} \hfill \\

\end{array} \right],

\end{aligned}$

|

(68) |

|

$\begin{aligned}

{F_H} & = \text{i} \rho \omega \int_{ - a}^0 {\left[ {{\phi _{2, v}}\left({b, z} \right) + {\phi _{2, h}}\left({b, z} \right) - {\phi _{4, v}}\left({b + l, z} \right) - {\phi _{4, h}}\left({b + l, z} \right)} \right]{\text{d}}z} \\

& = \frac{{\rho gH}}{2}\left[ \begin{array}{l}

\sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {\frac{{{A_n}}}{{{\beta _{nz}}}}\left({\tanh {\beta _{nz}}h - \frac{{\sinh {\beta _{nz}}d}}{{\cosh {\beta _{nz}}h}}} \right)} + \frac{{\sqrt 2 }}{2}a{B_0} + \sum\limits_{n = 1}^\infty {\frac{{{B_n}}}{{{\mu _n}}}\left({\sin {\mu _n}h - \sin {\mu _n}d} \right)} \hfill \\

+ \frac{{\sqrt 2 }}{2}a{C_0}\tanh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{0x}}b}}{2}} \right) + \sum\limits_{n = 1}^\infty {\frac{{{C_n}}}{{{\mu _n}}}\tanh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)\left({\sin {\mu _n}h - \sin {\mu _n}d} \right)} \hfill \\

- \frac{{\sqrt 2 }}{2}a{G_0} - \sum\limits_{n = 1}^\infty {\frac{{{G_n}}}{{{\mu _n}}}\left({\sin {\mu _n}h - \sin {\mu _n}d} \right)} \hfill \\

- \frac{{\sqrt 2 }}{2}a{H_0}\tanh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{0x}}b}}{2}} \right) - \sum\limits_{n = 1}^\infty {\frac{{{H_n}}}{{{\mu _n}}}\tanh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)\left({\sin {\mu _n}h - \sin {\mu _n}d} \right)} \hfill \\

\end{array} \right] .

\end{aligned}$

|

(69) |

The dimensionless vertical wave force CFV and horizontal wave force CFH are defined as follows:

|

$ {C_{FV}} = \frac{{|{F_V}|}}{{\rho g{h^2}}}, $

|

(70) |

|

$ {C_{FH}} = \frac{{|{F_H}|}}{{\rho g{h^2}}} . $

|

(71) |

4 Experimental Tests

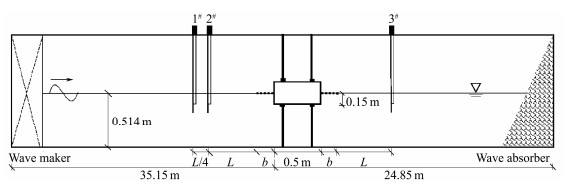

Experimental tests of wave action on an open-type rectangular breakwater with two horizontal perforated plates were conducted in the wave flume at the Shandong Provincial Key Laboratory of Ocean Engineering. The wave flume is 3.0 m in width, 1.5 m in depth, and 60.0 m in length, equipped with a wave maker system and wave attenuation slope at both ends. A thin glass wall was artificially used to separate the flume into two parts along the length direction, with widths of 2.2 m and 0.8 m. The experimental structure was positioned in a 0.8 m wave flume located 35.15 m away from the wave maker system. Fig.2 depicts the experimental setup diagram.

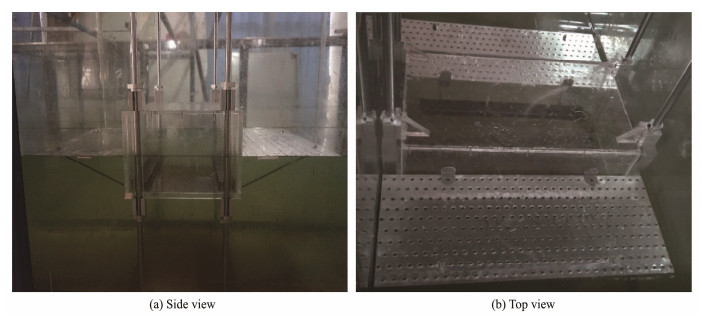

The open-type rectangular breakwater with horizontal perforated plates mainly consisted of a box and two horizontal perforated plates. The box model was made of acrylic plates whose thickness is 12 mm, measuring 0.785 m long, 0.5 m wide, and 0.3 m high. Horizontal perforated plates were made from high-rigidity stainless steel with a thickness of 2 mm, exhibiting no bending deformation during tests. In addition, four chrome-plated straight, smooth rods with a diameter of 25 mm were used to support the breakwater.

The experimental water depth was maintained at 0.514 m, and breakwaters always kept a draft (submergence depth) of half the height of the box (i.e., 0.15 m). The period range of the incident wave was 0.8 to 2.0 s. Each period corresponded to two incident wave heights of 0.02 m and 0.05 m. Two different plate widths with two porosities were designed for the horizontal perforated plates to explore the effect of their width and porosity on the reflection and transmission coefficients of a breakwater. Experimental tests were carried out on a control group, which was an open-type rectangular breakwater without any horizontal perforated plates. Further details regarding the experimental conditions are provided in Table 1.

Table 1

表 1

Table 1 Experimental cases and conditions

| Test parameter |

Symbol |

Values |

| Water depth |

h (m) |

0.514 |

| Wave height |

H (m) |

0.02, 0.05 |

| Wave period |

T (s) |

0.8, 1.0, 1.2, 1.4, 1.7, 2.0 |

| Submerged depth |

a (m) |

0.15 |

| Plate width |

b (m) |

0, 0.25, 0.4 |

| Porosity |

ε |

0.08, 0.15 |

|

Table 1 Experimental cases and conditions

|

On the horizontal stainless steel plates, circular cuts having a diameter of 0.01 m are evenly cut to achieve the desired porosity. The arrangement of these holes is given in Table 2.

Table 2

表 2

Table 2 Hole layout of horizontal perforated plates

| Plates width (m) |

Porosity ε |

Row |

Row spacing (m) |

Column |

Column spacing (m) |

Number of holes |

| 0.25 |

0.08 |

8 |

0.030 |

25 |

0.0310 |

200 |

| 0.15 |

15 |

0.016 |

25 |

0.0310 |

375 |

| 0.40 |

0.08 |

10 |

0.020 |

32 |

0.0245 |

400 |

| 0.15 |

15 |

0.025 |

40 |

0.0190 |

600 |

|

Table 2 Hole layout of horizontal perforated plates

|

After measuring the fixed height of the breakwater, the optical axis fixed seat was used to secure the box, ensuring that the model remained stable under the attack of waves. Stainless steel corner braces were positioned on the front, back, and bottom of the box to prevent the horizontal perforated plates from moving under the action of waves. In addition, the horizontal perforated plate was secured by four stainless steel threaded rods and nuts with a diameter of 8 mm. Fig.3 shows pictures of an open-type rectangular breakwater with horizontal perforated plates in the wave flume.

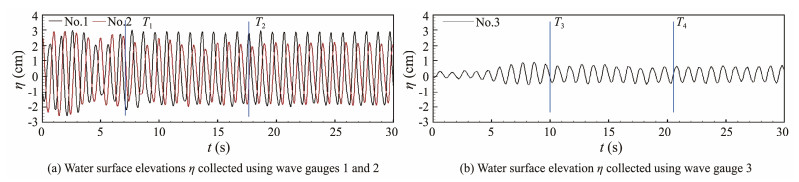

During the experimental tests, three capacitive-type wave gauges (referred to as Nos. 1 – 3) were positioned along the centerline of a water flume to measure water surface elevations, with a 50 Hz sampling frequency. Before the tests, the wave gauges were tested and calibrated to verify the accuracy and precision of the gathered data. Wave gauges 1 and 2 were placed before the breakwater. Wave gauge 2 would always be fixed at the distance of L from the breakwater, and the position of wave gauge 1 would be readjusted so that the distance between them would be maintained at L/4. Wave gauge 3 was positioned at a distance of L from the end of a breakwater. Fig.4 displays a representative time series of water surface elevations. Following a method by Goda and Suzuki (1976) to separate incident and reflected wave heights recorded by wave gauges 1 and 2 during the T1 to T2 period, transmitted wave height was determined utilizing a zero-up-cross analysis method. This method relied on stable surface elevations taken by wave gauge 3 between T3 and T4. Therefore, the above data can be utilized to derive the reflection and transmission coefficients. Each experimental case was repeated three times, and the average values were calculated as the final transmission and reflection coefficients.

5 Validation

5.1 Convergence Examination

The analytical solutions established in Sections 2 and 3 underwent testing to ensure their iterative and series convergence, guaranteeing that the calculation results are reasonable and reliable. First, the convergence of the calculation results was checked as the iterative step M increased to ensure that the iterative algorithm was effective and dependable. As the iterative step M increased, the calculated complex expansion coefficients were recorded (Tables 3 and 4). The calculating conditions in both tables are: ε = 0.2, H/L = 0.02, b/h = 0.5, l/h = 1.0, a/h = 0.3, δ/h = 0.002, k0h = 2.0, θ = 30˚, and μ = 0.8, with a truncated number N of 30. These two tables demonstrate that after 13 iterative steps, the calculation results can attain a precision of 10–4. Moreover, the iterative calculation cases in this research typically converge within 20 iterations.

Table 3

表 3

Table 3 Convergence of calculated expansion coefficients R0, A0, C0, and D0 as the iterative step M increases

| M |

Expansion coefficients |

| R0 |

A0 |

C0 |

D0 |

| 0 |

– |

0 |

– |

– |

| 1 |

0.28227 + 0.92189i |

0.68895 + 0.51179i |

1.23603 + 0.90067i |

0.35520 + 0.35753i |

| 3 |

0.18876 − 0.09120i |

0.69139 − 0.08218i |

0.40980 + 0.51418i |

0.31855 + 0.05947i |

| 5 |

0.18626 − 0.08482i |

0.68965 − 0.07865i |

0.41797 + 0.51880i |

0.31871 + 0.06120i |

| 7 |

0.18621 − 0.08490i |

0.68963 − 0.07870i |

0.41806 + 0.51878i |

0.31875 + 0.06112i |

| 9 |

0.18621 − 0.08492i |

0.68963 − 0.07872i |

0.41807 + 0.51877i |

0.31876 + 0.06110i |

| 11 |

0.18621 − 0.08493i |

0.68963 − 0.07872i |

0.41807 + 0.51876i |

0.31876 + 0.06110i |

| 13 |

0.18621 − 0.08493i |

0.68963 − 0.07872i |

0.41807 + 0.51876i |

0.31876 + 0.06110i |

| Notes: ε = 0.2, H/L = 0.02, b/h = 0.5, l/h = 1.0, a/h = 0.3, δ/h = 0.002, k0h = 2.0, θ = 30˚, and μ = 0.8. |

|

Table 3 Convergence of calculated expansion coefficients R0, A0, C0, and D0 as the iterative step M increases

|

Table 4

表 4

Table 4 Convergence of calculated expansion coefficients F0, G0, H0, and T0 as the iterative step M increases

| M |

Expansion coefficients |

| F0 |

G0 |

H0 |

T0 |

| 0 |

0 |

– |

– |

– |

| 1 |

−0.16360 + 0.14611i |

−0.01975 + 0.12133i |

−0.13579 − 0.30569i |

−0.18498 + 0.14166i |

| 3 |

−0.04590 + 0.10737i |

0.04259 + 0.06494i |

−0.16176 − 0.08982i |

−0.03471 + 0.12287i |

| 5 |

−0.04685 + 0.10621i |

0.04265 + 0.06509i |

−0.16094 − 0.08989i |

−0.03487 + 0.12228i |

| 7 |

−0.04688 + 0.10597i |

0.04275 + 0.06505i |

−0.16083 − 0.08964i |

−0.03472 + 0.12215i |

| 9 |

−0.04689 + 0.10593i |

0.04277 + 0.06504i |

−0.16081 − 0.08960i |

−0.03469 + 0.12213i |

| 11 |

−0.04689 + 0.10592i |

0.04277 + 0.06504i |

−0.16081 − 0.08959i |

−0.03469 + 0.12212i |

| 13 |

−0.04689 + 0.10592i |

0.04277 + 0.06503i |

−0.16081 − 0.08959i |

−0.03469 + 0.12212i |

| Note: Same as Table 3. |

|

Table 4 Convergence of calculated expansion coefficients F0, G0, H0, and T0 as the iterative step M increases

|

Subsequently, it is necessary to check whether the analytical solutions converge as the truncated number N increases. Table 5 presents the calculated values of the reflection and transmission coefficients under the same conditions as Table 3. Table 5 concludes that the values of the reflection and transmission coefficients converge slowly as the truncation number increases. Calculation results remain adequate for engineering analysis when the truncation number is N = 40, so it was used in the subsequent calculation.

Table 5

表 5

Table 5 CR and CT converge as the truncated number N increases under different k0h

| N |

k0h = 0.5 |

|

k0h = 1.0 |

|

k0h = 2.0 |

|

k0h = 3.0 |

| CR |

CT |

|

CR |

CT |

|

CR |

CT |

|

CR |

CT |

| 5 |

0.359 |

0.827 |

|

0.451 |

0.485 |

|

0.233 |

0.130 |

|

0.144 |

0.028 |

| 10 |

0.356 |

0.826 |

|

0.445 |

0.484 |

|

0.220 |

0.129 |

|

0.130 |

0.028 |

| 20 |

0.354 |

0.826 |

|

0.440 |

0.482 |

|

0.207 |

0.127 |

|

0.121 |

0.027 |

| 30 |

0.353 |

0.826 |

|

0.438 |

0.482 |

|

0.205 |

0.127 |

|

0.117 |

0.027 |

| 40 |

0.353 |

0.826 |

|

0.437 |

0.482 |

|

0.203 |

0.127 |

|

0.115 |

0.027 |

|

Table 5 CR and CT converge as the truncated number N increases under different k0h

|

5.2 Comparison with Iterative BEM Solutions

An iterative BEM developed by Liu and Li (2017) was employed to resolve the same boundary value problems in this research. The hydrodynamic quantities computed using the proposed analytical solutions for the open-type rectangular breakwater with horizontal perforated plates were compared with the iterative BEM solutions in Fig.5 under the same calculation conditions as Table 3. Fig.5 indicates good consistency between the results of the two solutions.

5.3 Comparison with Experimental Data

The analytical solution formulated in Section 2 specifies the quadratic pressure drop conditions, particularly Eqs. (8) and (9), where the discharge coefficients μ must be known in advance and determined through experimental testing. In the study of He et al. (2022), the discharge coefficients for the horizontal perforated plates with porosity of 0.089 and 0.149 are determined to be 2.6 and 1.1, respectively, through experimental testing. In the experimental tests of the present study, the porosities of the horizontal perforated plates are 0.08 and 0.15, which are very close to the porosities of the plates in He et al. (2022). Therefore, the discharge coefficients in the analytical solutions are taken as 2.6 and 1.1.

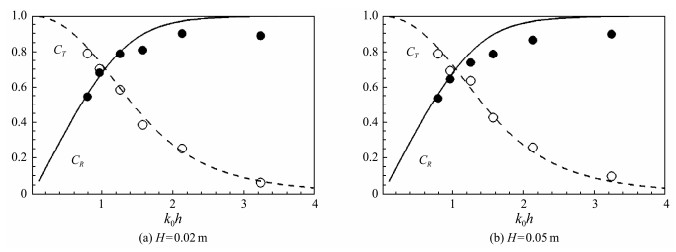

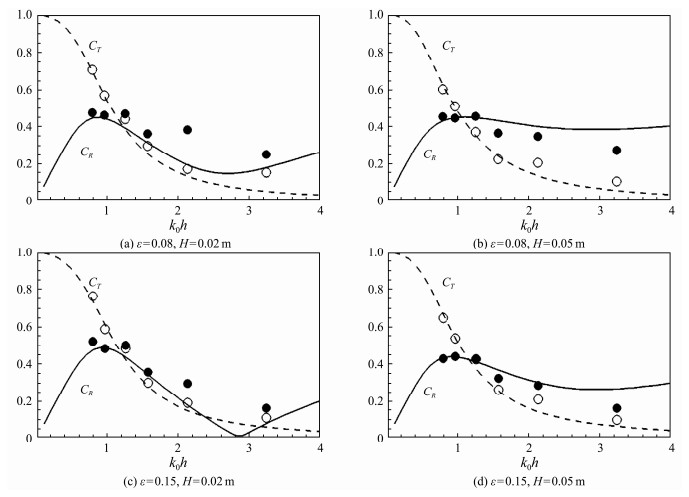

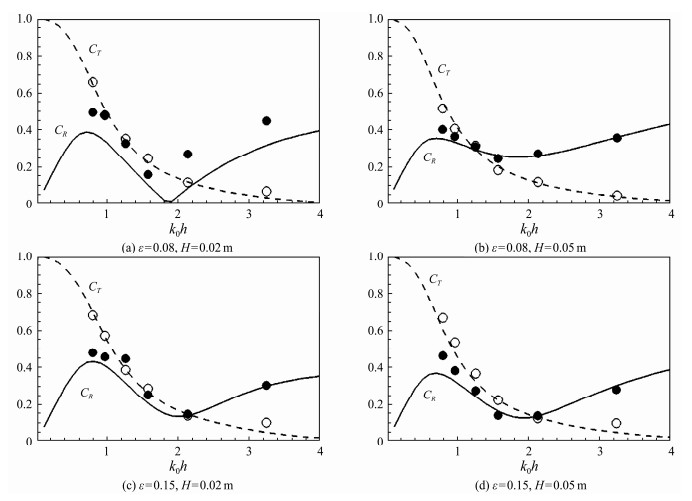

Figs.6 – 8 compare the analytical solutions with experimental values for the new breakwater, considering breakwater models without horizontal perforated plates and two different widths of horizontal perforated plates. The analytical solutions generally match experimental measurement results well, and these two discharge coefficient values are used in subsequent calculations and discussions. These results demonstrate that the proposed analytical solutions can account for the change in reflection and transmission coefficients of an open-type rectangular breakwater with horizontal perforated plates under varying wave heights.

According to the experimental measurement values shown in Figs.6 – 8, the transmission and reflection coefficients can be effectively decreased by adding horizontal perforated plates at the water surface on both sides of the rectangular breakwater. The two coefficients decrease as the width of the perforated plate increases, indicating that the addition of horizontal perforated plates considerably improved the wave dissipation capacity. The transmission coefficient for the breakwater with horizontal perforated plates, having a porosity of 0.08, is lower than that of the breakwater with a porosity of 0.15 when subjected to longer waves. By contrast, this new open-type rectangular breakwater has a better defense effect against waves with a larger steepness.

6 Further Calculation Results and Discussion

This section presents further analytical solution calculation results that reveal the effects of different parameters on the hydrodynamic quantities for an open-type rectangular breakwater with horizontal perforated plates.

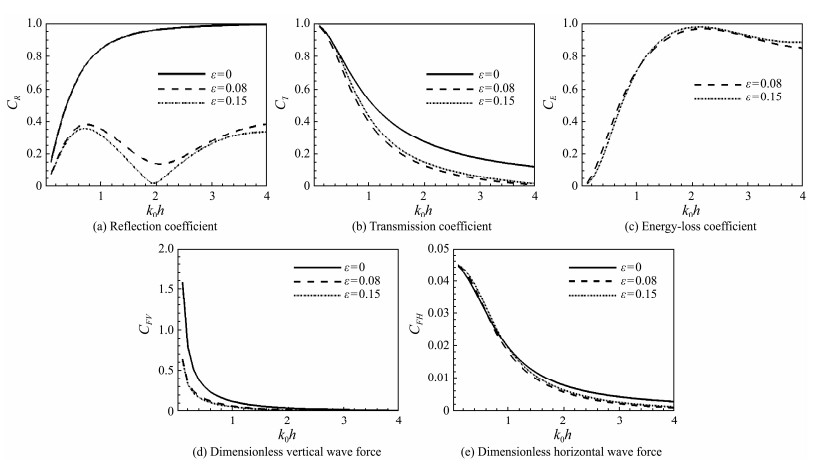

Fig.9 illustrates the variations of the hydrodynamic characteristics for the open-type rectangular breakwater with horizontal perforated plates at different porosity ε and dimensionless wave number k0h. Fig.9(a) indicates the reflection effect of the breakwater gradually enhances as k0h increases when the horizontal plates are solid. However, when the horizontal plates are perforated, the reflection coefficient CR initially increases, then decreases, and then increases again. By contrast, the breakwater with a porosity of 0.15 has a special value of the reflection coefficient CR close to 0. In Fig.9(b), the shielding effect of the breakwater with a porosity of 0.08 is marginally superior to that of the breakwater with a porosity of 0.15. Additionally, a breakwater with horizontal perforated plates has a considerably better shielding effect than the one with solid horizontal plates. Fig.9(c) indicates that this outcome is because the horizontal perforated plates dissipate most of the wave energy. A comparison of Figs.9(d) and (e) reveals that the perforations in the horizontal plate have little effect on the horizontal wave force. However, when suffering from longer waves, the vertical wave force withstood by a breakwater with horizontal solid plates is much stronger than that by a breakwater with horizontal perforated plates. As vertical wave force is too strong compared with its horizontal wave force, more safety consideration should be given to the vertical wave force when designing breakwaters for engineering applications.

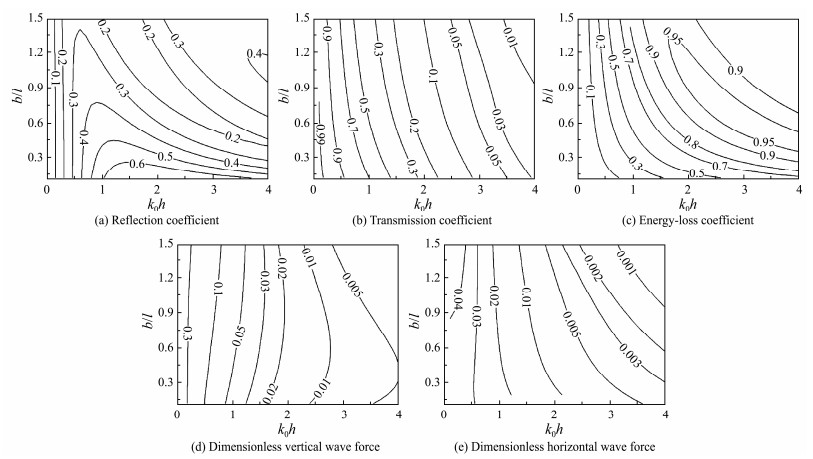

Fig.10 shows the comprehensive influence of relative plate width b/l and non-dimensional wave number k0h on CR, CT, CE, CFV, and CFH for the open-type rectangular breakwater with horizontal perforated plates. The reflection coefficient CR remains almost unchanged as the plate width increases at smaller k0h and decreases with increasing plate width at larger k0h, as shown in Fig.10(a). When the breakwater is not equipped with perforated plates, substantial reflection occurs in front of the breakwater. Fig.10(c) indicates that the variation regularity of energy-loss coefficient CE is opposite to the trend of reflection coefficient CR, and breakwaters with longer perforated plates have a much stronger influence on wave energy dissipation. Figs.10(b), (d), and (e) show with relative plate width rise, the transmission coefficient CT of breakwater reduces, horizontal wave force CFH decreases, and vertical wave force CFV increases slowly.

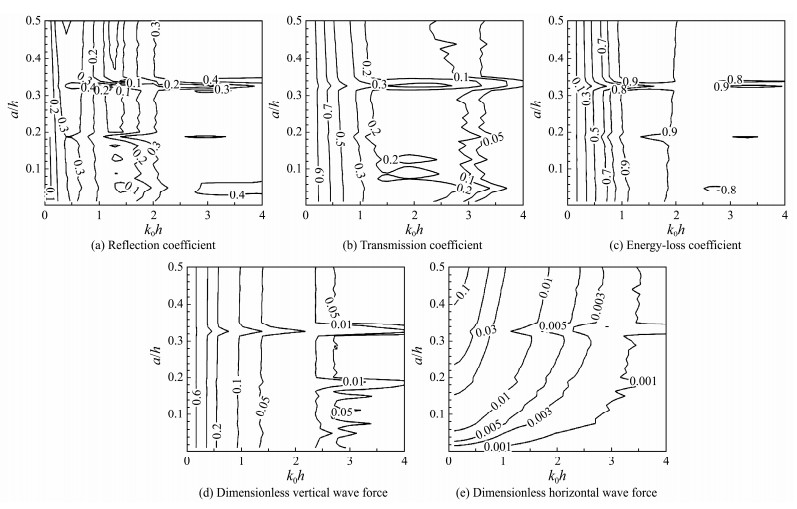

Fig.11 illustrates the hydrodynamic quantities for the open-type rectangular breakwater with horizontal perforated plates at various relative submerged depths a/h and non-dimensional wave number k0h. The figure shows that the breakwater has a considerable defensive effect against longer periodic waves. Except for the horizontal wave force CFH, the other four hydrodynamic parameters of the breakwater are relatively unaffected by changes in relative submerged depth in this condition. Besides, the effect of incident wave number k0h on them is much greater than the relative submerged depth. In general, the shielding effects of a breakwater and the horizontal wave force it bears enhance with the expansion in submerged depth. Fig.11 shows many sharp corners, particularly for short waves. The reason is that the diffraction effect of long waves is strong, and the breakwater can only provide a smaller shielding effect. On the contrary, short waves interact strongly with the breakwater, so the combined effect of the box and the perforated plates results in a relatively complex variation rule for hydrodynamic quantities.

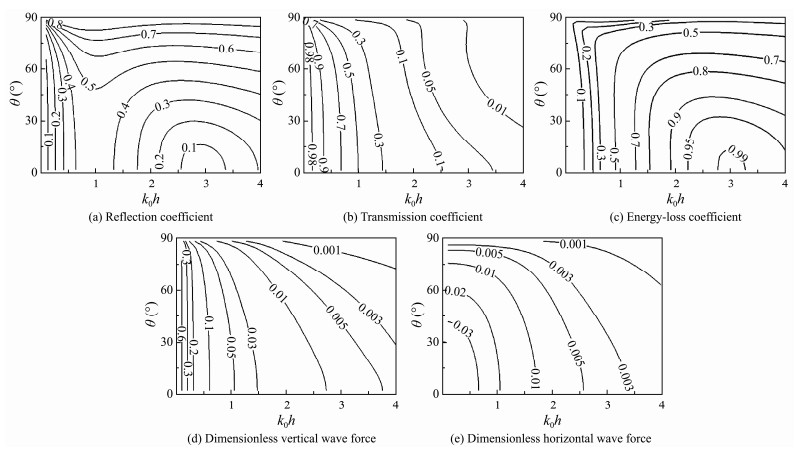

The comprehensive influence of varying incident wave angle θ and non-dimensional wave number k0h on CR, CT, CE, CFV, and CFH for the open-type rectangular breakwater with horizontal perforated plates are shown in Fig.12. Except for the reflection coefficient CR, the other four hydrodynamic quantities decrease as the incident wave angle increases, indicating that the breakwater has better defense against waves with larger incident wave angles and bears less wave force.

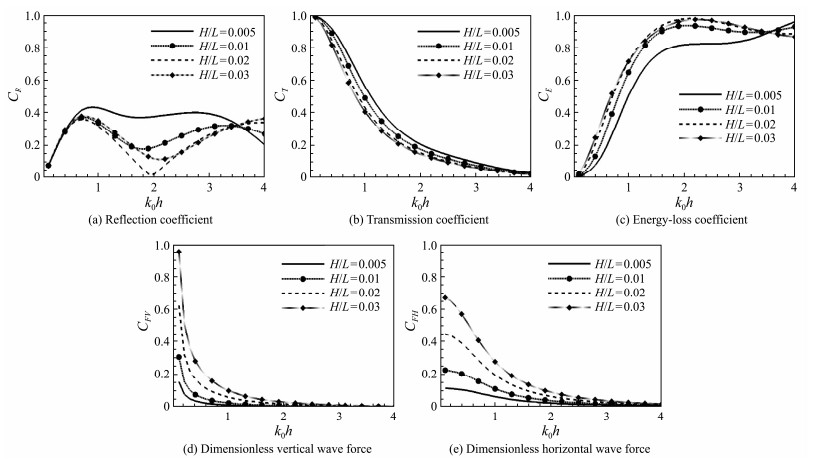

Fig.13 reveals variations of hydrodynamic parameters for an open-type rectangular breakwater with horizontal perforated plates at different incident wave steepness H/L. According to Figs.13(a), (b), and (c), the breakwater has a superior wave dissipation and defense effect on waves with larger wave steepness. Figs.13(d) and (e) illustrate that the horizontal and vertical wave forces rise as wave steepness increases, particularly for longer periodic waves.

7 Concluding Remarks

In this study, a novel open-type rectangular breakwater incorporating two horizontal perforated plates was proposed, and the hydrodynamic characteristics of the breakwater were investigated analytically and experimentally. This research derived the analytical solution of scattering for oblique waves by the new breakwater based on potential theory, using the velocity potential decomposition method and an iterative algorithm. The horizontal perforated plates at a water surface were replaced by the quadratic pressure drop conditions, enabling a direct consideration of the effect of wave height on dissipating wave energy. Moreover, the reflection and transmission coefficients of a breakwater were measured through experimental testing under various wave and structural parameter conditions. The convergence examination of analytical solutions indicated the satisfactory convergence of the series solution and iterative procedure. The level of agreement was exceptional between the analytical and iterative BEM solutions as well as between analytical solutions and experimental test values.

Further calculated results by the proposed analytical solution provided insights into the effects of various parameters on the reflection coefficient, transmission coefficient, energy-loss coefficient, dimensionless vertical wave force, and dimensionless horizontal wave force for an open-type rectangular breakwater with horizontal perforated plates. Based on these findings, the following principal conclusions were drawn:

1) The perforation of horizontal plates enhanced the protective effect of a breakwater and reduced the vertical wave force it bore. Besides, varying the porosity of horizontal plates caused notable disparities in the changes in the reflection coefficient for the breakwater.

2) When the relative width of the breakwater was large, the relative submerged depth had a relatively small influence on the breakwater. Breakwaters exhibited a better energy dissipation effect on waves with large wave steepness. However, the horizontal and vertical wave forces borne by the structure were enhanced, especially for longer waves.

3) The reflection coefficient, transmission coefficient, and horizontal wave force of breakwaters were usually reduced as the perforated plate width increased. By contrast, the energy-loss coefficient and vertical wave force increased.

4) In engineering applications, more consideration should be given to the vertical wave force. The reason is the breakwater bears a much larger vertical wave force than a horizontal wave force.

Last, future studies should focus on the moored rectangular floating breakwater with horizontal perforated plates because of its superior adaptability to water level variation.

Appendix

|

$ {a_{mn}} = \frac{{\int_{ - h}^0 {{X_m}(z){Z_n}(z)} {\text{d}}z}}{{\int_{ - h}^0 {X_m^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}, $

|

(A1) |

|

$ {b_{mn}}{\text{ = }}\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

{0, {\text{ }}m = n = 0} \\

{\tanh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{mx}}b}}{2}} \right), {\text{ }}m = n \ne 0} \\

{0, {\text{ }}m \ne n \ne 0}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(A2) |

|

$ {\zeta _m}{\text{ = }} - \frac{{\int_{ - h}^0 {{X_m}(z){Z_0}(z)} {\text{d}}z}}{{\int_{ - h}^0 {X_m^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}, $

|

(A3) |

|

$ {\tilde k_m} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

{ - { \text{i}}{k_{{\text{0}}x}}{\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt}, {\text{ }}m = 0} \\

{{k_{mx}}, {\text{ }}m \ne 0}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(A4) |

|

$ {c_{mn}} = - \frac{{{\beta _n}}}{{{{\tilde k}_{mx}}}}\frac{{\sin ({\beta _n}b)}}{{\int_{ - h}^0 {Z_m^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}\int_{ - h}^0 {\frac{{\cosh {\beta _{nz}}(z + h)}}{{\cosh ({\beta _{nz}}h)}}{Z_m}(z){\text{d}}z}, $

|

(A5) |

|

$ {d_{mn}} = \frac{{{\mu _{nx}}}}{{{{\tilde k}_{mx}}}}\tanh \frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}\frac{{\int_{ - h}^0 {{X_n}(z){Z_m}(z){\text{d}}z} }}{{\int_{ - h}^0 {Z_m^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}, $

|

(A6) |

|

$ {e_{mn}} = - \frac{{{\mu _{nx}}}}{{{{\tilde k}_{mx}}}}\frac{{\int_{ - h}^0 {{X_n}(z){Z_m}(z){\text{d}}z} }}{{\int_{ - h}^0 {Z_m^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}, $

|

(A7) |

|

$ {\gamma _n}{\text{ = }}\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

{1\;, {\text{ }}n = 0} \\

{0{\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt}, {\text{ }}n \ne 0}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(A8) |

|

$ {f_{mn}} = - \frac{{\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {\cosh {\beta _{nz}}(z + h){Y_m}(z){\text{d}}z} }}{{\cosh {\beta _{nz}}h\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {Y_{^m}^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}, $

|

(A9) |

|

$ {g_{mn}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

{ - \frac{{\sqrt 2 }}{2}\frac{{\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {{Y_m}(z){\text{d}}z} }}{{\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {Y_m^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}{\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt}, {\text{ }}n = 0} \\

{ - \frac{{\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {{X_n}(z)} {Y_m}(z){\text{d}}z}}{{\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {Y_m^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}{\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt} {\kern 1pt}, {\text{ }}n \ne 0}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(A10) |

|

$ {h_{mn}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}

{ - \frac{{\sqrt 2 }}{2}\tanh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)\frac{{\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {{Y_m}(z){\text{d}}z} }}{{\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {Y_m^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}{\kern 1pt}, {\text{ }}n = 0} \\

{ - \tanh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)\frac{{\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {{X_n}(z)} {Y_m}(z){\text{d}}z}}{{\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {Y_m^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}{\kern 1pt}, {\text{ }}n \ne 0}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(A11) |

|

$ {i_{mn}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

{0, {\text{ }}m \ne n} \\

{ - \tanh \frac{{{\lambda _{mx}}l}}{2}\;, {\text{ }}m = n}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(A12) |

|

$ {j_{mn}}{\text{ = }}\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

{0, {\text{ }}m = n = 0} \\

{ - {\mu _{mx}}\tanh \frac{{{\mu _{mx}}b}}{2}, {\text{ }}m = n \ne 0} \\

{0, {\text{ }}m \ne n \ne 0}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(A13) |

|

$ {k_{mn}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

{ - {\mu _{mx}}, {\text{ }}m = n} \\

{0{\kern 1pt}, {\text{ }}m \ne n}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(A14) |

|

$ {l_{mn}} = - {\lambda _{nx}}\tanh \frac{{{\lambda _{nx}}l}}{2}\frac{{\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {{X_m}(z){Y_n}(z){\text{d}}z} }}{{\int_{ - h}^0 {X_m^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}, $

|

(A15) |

|

$ {m_{mn}} = {\lambda _{nx}}\frac{{\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {{X_m}(z){Y_n}(z){\text{d}}z} }}{{\int_{ - h}^0 {X_m^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}, $

|

(A16) |

|

$ {n_{mn}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

\left[ {1 + \left({2C - \frac{1}{K}} \right){\beta _{mz}}\tanh({\beta _{mz}}h)} \right] + \hfill \\

\quad {\beta _{nz}}\tanh({\beta _{nz}}h)\frac{{\int_0^b {\Psi (x){W_m}(x){W_n}(x){\text{d}}x} }}{{\int_0^b {W_m^2(x){\text{d}}x} }}, {\text{ }}m = n \hfill \\

{{\beta _{nz}}\tanh({\beta _{nz}}h)\frac{{\int_0^b {\Psi (x){W_m}(x){W_n}(x){\text{d}}x} }}{{\int_0^b {W_m^2(x){\text{d}}x} }}, {\text{ }}m \ne n}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(A17) |

|

$ \Psi (x) = \frac{{8 \text{i} }}{{3{\mathtt{π}}\omega }}\frac{{1 - \varepsilon }}{{2\mu {\varepsilon ^2}}}\left| {\frac{{ - \text{i} gH}}{{2\omega }}\sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {{\beta _{nz}}{A_n}{W_n}(x)} \tanh({\beta _{nz}}h)} \right|, $

|

(A18) |

|

$ {o_{mn}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

{\frac{{\sqrt 2 }}{2}\frac{1}{{\int_0^b {W_m^2(x){\text{d}}x} }}\int_{\text{0}}^b {\left[ {\frac{{\cosh {\mu _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{b}{2}} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)}}{W_m}(x)} \right]{\text{d}}x, {\text{ }}n = 0} } \\

{\frac{{\cos ({\mu _n}h)}}{{\int_0^b {W_m^2(x){\text{d}}x} }}\int_{\text{0}}^b {\left[ {\frac{{\cosh {\mu _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{b}{2}} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)}}{W_m}(x)} \right]{\text{d}}x, {\text{ }}n \ne 0} }

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(A19) |

|

$ {p_{mn}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

{\frac{{\sqrt 2 }}{2}\frac{1}{{\int_0^b {W_m^2(x){\text{d}}x} }}\int_{\text{0}}^b {\left[ {\frac{{\sinh {\mu _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{b}{2}} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)}}{W_m}(x)} \right]{\text{d}}x, {\text{ }}n = 0} } \\

{\frac{{\cos ({\mu _n}h)}}{{\int_0^b {W_m^2(x){\text{d}}x} }}\int_{\text{0}}^b {\left[ {\frac{{\sinh {\mu _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{b}{2}} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)}}{W_m}(x)} \right]{\text{d}}x, {\text{ }}n \ne 0} }

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(A20) |

|

$ {q_{mn}} = - {\beta _n}\sin ({\beta _n}b)\frac{{\int_{ - h}^{\text{0}} {\cosh {\beta _{nz}}(z + h){X_m}(z){\text{d}}z} }}{{\cosh {\beta _{nz}}h\int_{ - h}^{\text{0}} {X_{^m}^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}, $

|

(A21) |

|

$ {r_{mn}} = - \frac{{\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {\cosh {\beta _{nz}}(z + h){X_m}(z){\text{d}}z} }}{{\cosh {\beta _{nz}}h\int_{ - h}^{ - a} {X_{^m}^2(z){\text{d}}z} }}, $

|

(A22) |

|

$ {s_{mn}}{\text{ = }}\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

\left[ {1 + \left({2C - \frac{1}{K}} \right){\beta _{mz}}\tanh({\beta _{mz}}h)} \right] + \hfill \\

\quad {\beta _{nz}}\tanh({\beta _{nz}}h)\frac{{\int_0^b {\Gamma (x){U_m}(x){U_n}(x){\text{d}}x} }}{{\int_0^b {U_m^2(x){\text{d}}x} }}, {\text{ }}m = n \hfill \\

{{\beta _{nz}}\tanh({\beta _{nz}}h)\frac{{\int_0^b {\Gamma (x){U_m}(x){U_n}(x){\text{d}}x} }}{{\int_0^b {U_m^2(x){\text{d}}x} }}, {\text{ }}m \ne n}

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(A23) |

|

$ \Gamma (x) = \frac{{8 \text{i} }}{{3{\mathtt{π}}\omega }}\frac{{1 - \varepsilon }}{{2\mu {\varepsilon ^2}}}\left| {\frac{{ - \text{i} gH}}{{2\omega }}\sum\limits_{n = 0}^\infty {{\beta _{nz}}{F_n}{U_n}(x)} \tanh({\beta _{nz}}h)} \right|, $

|

(A24) |

|

$ {t_{mn}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

\frac{{\sqrt 2 }}{2}\frac{1}{{\int_{b + l}^{2b + l} {U_m^2(x){\text{d}}x} }} \cdot \hfill \\

\quad \int_{b + l}^{2b + l} {\left[ {\frac{{\cosh {\mu _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{{3b}}{2} - l} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)}}{U_m}(x)} \right]{\text{d}}x, {\text{ }}n = 0} \hfill \\

\frac{{\cos ({\mu _n}h)}}{{\int_{b + l}^{2b + l} {U_m^2(x){\text{d}}x} }} \cdot \hfill \\

\quad \int_{b + l}^{2b + l} {\left[ {\frac{{\cosh {\mu _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{{3b}}{2} - l} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)}}{U_m}(x)} \right]{\text{d}}x, {\text{ }}n \ne 0} \hfill \\

\end{array}} \right., $

|

(A25) |

|

$ {u_{mn}} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}}

\frac{{\sqrt 2 }}{2}\frac{1}{{\int_{b + l}^{2b + l} {U_m^2(x){\text{d}}x} }} \cdot \hfill \\

\quad \int_{b + l}^{2b + l} {\left[ {\frac{{\sinh {\mu _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{{3b}}{2} - l} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)}}{U_m}(x)} \right]{\text{d}}x, {\text{ }}n = 0} \hfill \\

\frac{{\cos ({\mu _n}h)}}{{\int_{b + l}^{2b + l} {U_m^2(x){\text{d}}x} }} \cdot \hfill \\

\quad \int_{b + l}^{2b + l} {\left[ {\frac{{\sinh {\mu _{nx}}\left({x - \frac{{3b}}{2} - l} \right)}}{{\cosh \left({\frac{{{\mu _{nx}}b}}{2}} \right)}}{U_m}(x)} \right]{\text{d}}x, {\text{ }}n \ne 0} \hfill \\

\end{array}} \right. . $

|

(A26) |

AcknowledgementsThis study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52201345, and 52001293), and the New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the XPLORER PRIZE.

0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 0)

0) 2024, Vol. 23

2024, Vol. 23