2) Key Laboratory of Experimental Marine Biology, Center for Ocean Mega-Science, Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China;

3) Laboratory for Marine Drugs and Bioproducts, Qingdao Marine Science and Technology Center, Qingdao 266237, China

Water pollution is getting worse and has been one of the severest environmental challenges (Zhou et al., 2019). Particularly, dyes from the textile, printing, and dyeing industries are one of the primary sources of water pollution (Tang et al., 2020b; Popoola et al., 2021). With the development of industrialization, the use of dyestuffs is increasing, resulting in a corresponding increase in the discharge of dyestuff wastewater. Dye wastewater poses a significant threat to aquatic organisms due to its complex composition and high toxicity (Wang et al., 2005; Kismir et al., 2011; Cao et al., 2018). Congo red (C32H22N6Na2O6S2) is a significant pollutant in printing and dyeing effluents and is a commonly used azo-anionic dye (Cui et al., 2021). Aquatic organisms can metabolize Congo red into benzidine, a carcinogen that can harm humans (Velkova et al., 2018). Due to its complex aromatic structure, it is typically difficult to be degraded (Soni et al., 2020). The coloration of Congo red hurts the photosynthesis of aquatic plants, affecting the ecosystem (Chen et al., 2016). The urgent issue of Congo red wastewater contamination needs to be addressed.

Printing and dyeing wastewater can be treated using various methods, including biological processes (Wu et al., 2023), chemical methods (Cui et al., 2021), adsorption methods (Extross et al., 2023), and photocatalytic degradation methods (Taha et al., 2019). Physical adsorption is widely considered as the most promising method for treating wastewater due to its simple, low-cost, highly efficient, environmentally friendly property (Dinh et al., 2019). Adsorption is a process that transfers hazardous substances from wastewater to the solid phase, which can reduce their potential damage to the aquatic environment (dos Santos et al., 2014). Li and Zhai (2023) shows that modified peanut shells effectively adsorbed Cr3+ from wastewater. El Jery et al. (2024) synthesized an activated carbon adsorbent from rice straw precursor to remove methylene blue dye from wastewater. Adebayo et al. (2022) developed a composite material using coconut shells, raw clay, Fe(Ⅱ), and Fe(Ⅱ) compounds to adsorb Congo red dye from wastewater. Paluch et al. (2023) utilized biochar derived from fennel seeds to eliminate methyl red from an aqueous solution. Using biowaste as an adsorbent has emerged as a new direction in recent years.

In recent years, there has been a significant increase in global aquaculture, with shellfish accounting for a considerable portion (Sicuro et al., 2021). The increasing amount of shellfish farming also generates significant shell waste. It is often discarded as an industrial by-product and food waste (Qin et al., 2016). Shell waste has been a significant environmental issue in coastal regions; however, they are a valuable renewable mineral resource. Shells comprise 95% CaCO3 and 5% organic matter (Srichanachaichok and Pissuwan, 2023). After CO2 emissions and substance decomposition, calcined shells form a complex porous structure that serves as the foundation for their adsorption properties (Dai et al., 2018; Rodríguez-Arellano et al., 2021). Furthermore, shells settle faster, making them more suitable for separating and recovering adsorbents (El Jery et al., 2024).

Mytilus edulis is widely distributed worldwide. In recent years, the scale of M. edulis farming has significantly increased due to technological advancements. M. edulis shells are produced in large quantities as waste products. Finding practical methods to use them is an important issue. In recent years, M. edulis shells have been widely used in many fields, such as catalyst carriers for photocatalytic reactions (Cao et al., 2023), soil conditioners (Hannan et al., 2021), and adsorbents (Trinh et al., 2023). Wang et al. (2021) reported that M. edulis shell powders could adsorb Pb(Ⅱ) from aqueous solution. M. edulis shell is a good adsorbent due to its low cost, high efficiency, and minimal side effects. However, the adsorption result of dye, such as Congo red, onto M. edulis shells is still unknown.

Utilizing waste resources such as shells for decolorizing dye wastewater can not only help address the wastewater treatment issue, but also promote the efficient use of shell waste resources. Thus, the current study aims to employ discarded M. edulis shells for the removal of Congo red. The characteristics of M. edulis shell powders adsorbing Congo red dye were also investigated, including the adsorption conditions, kinetics, and isothermal adsorption models. This research provides a theoretical basis for developing adsorbents using M. edulis shell waste.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 MaterialsM. edulis were collected from Tuandao Seafood Market in Qingdao, Shandong, China. Congo red was from Tianjin Damao Chemical Reagents Factory, and other reagents are analytically pure.

2.2 Preparation and Thermal Modification of M. edulis Shell AdsorbentThe shells of M. edulis were washed to eliminate any insoluble impurities, such as sediment. The shells were dried in an oven at 70℃ for 12 h and then calcined in a muffle furnace at temperatures of 550℃, 700℃, and 900℃ for 3 h respectively. After completing the calcination process, the samples were cooled down to room temperature and weighed to determine their yields. The shells were crushed separately before and after calcination using a high-speed multifunctional grinder. The shell powder was sieved through a 200 mesh sieve, and the powder that passed through was collected.

2.3 Structural Characterization of Shell PowderThe characteristics of M. edulis shell adsorbent was studied with a SU8020 scanning electron microscope. The powdered shells before and after calcination were coated with gold for SEM observation.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of shell powder was conducted using KBr pressing method. The functional groups of the modified adsorbent were determined through this process. The shell powder was analyzed using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS10 Fourier infrared spectrometer with a 4000 – 400 cm–1 scanning range.

2.4 Adsorption ExperimentsA series of standard solutions of Congo red at different concentrations of 5, 20, 35, 50, and 70 mg L–1 were prepared, and their absorbance was measured at 498 nm. The plot of Congo red concentration versus absorbance was illustrated to create the standard curve.

Batch adsorption experiments were conducted using various shell powders. The study investigated the impact of temperature, contact time, and Congo red concentration on adsorption process. The batch experiment steps are outlined as below: 0.1 g of shell powders and 50 mL of Congo red solution at 250 mg L–1 were added into a 100 mL conical flask. The adsorption experiments were conducted at 25℃ with a rotation speed of 150 r min–1 for 12 h in a constant temperature shaker. Subsequently, the adsorbed solution was centrifuged at 10000 r min–1 for 3 min, and then the absorbance of the supernatant was measured. The concentration of Congo red in the adsorbed solution was determined using the standard curve of Congo red. The samples underwent three sets of repetitive parallel adsorption experiments. The average value was calculated, and the adsorption capacity was determined using the following equation (Tang et al., 2020a):

| $ {Q_{\text{e}}} = \frac{{({C_0} {C_t})V}}{m}, $ | (1) |

where C0 is the initial concentration of Congo red solution (mg L–1), Ct is the concentration of Congo red in the solution after adsorption at time t (mg L–1), t is the adsorption reaction time (min), V is the volume of the solution (L), and m is the mass of shell powder (g).

The kinetics of adsorption was conducted at 25℃ with a concentration of 250 mg L–1. The concentration of Congo red in the supernatant was measured at 5, 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 min, respectively. The study of adsorption kinetics can aid in comprehending the mechanisms of adsorption. Adsorption kinetics is concerned with the dispersion characteristics of adsorbent particles. The data is often fitted using the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetic models (Srilakshmi and Saraf, 2016).

The pseudo-first-order kinetic model assumes that the adsorption rate is proportional to the number of unoccupied sites on the adsorbent (Acemioğlu, 2005):

| $ \log ({Q_{\text{e}}}-{Q_t}) = \log {Q_{\text{e}}}-\frac{{{k_1}}}{{2.303}} \times t, $ | (2) |

where Qe and Qt are the unit adsorption capacity (mg g–1) at equilibrium and time t, respectively; k1 is the pseudo-first-order adsorption rate constant (min–1), and t is the adsorption reaction time (min).

The pseudo-second-order kinetic model assumes that the adsorption rate is proportional to the square of the number of unoccupied adsorption sites (Ho and Mckay, 1999):

| $ \frac{t}{{{Q_t}}} = \frac{1}{{{k_2}Q_{\text{e}}^2}} + \frac{1}{{{Q_{\text{e}}}}}t, $ | (3) |

where k2 is the rate constant for quasi-secondary adsorption (g mg–1 min–1). The Qe and k2 values are determined by fitting a linear relationship to a graph with t and t/Qt as horizontal and vertical coordinates, respectively.

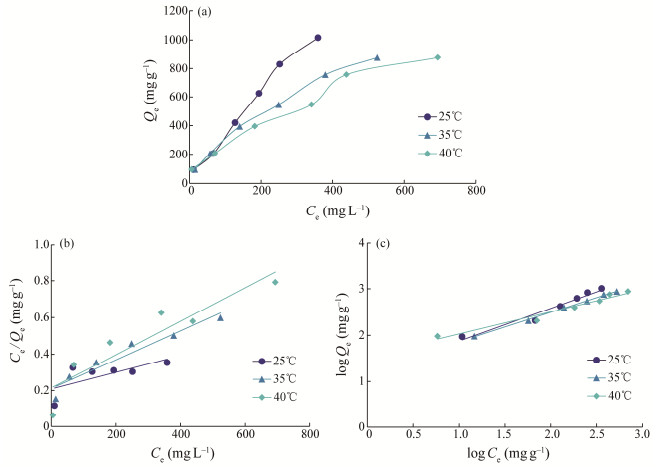

2.5 Adsorption IsothermsThe impacts of varying shell powder concentrations on the adsorption of Congo red were investigated at 25℃, 35℃, and 40℃, respectively. The shell powder was initially presented in 200, 500, 1000, 1500, 2000, and 2500 mg L–1 concentrations. The adsorption isotherm shows the correlation between the adsorbent's equilibrium amount and the solution's remaining concentration. Adsorption equilibrium is achieved when the adsorbate concentration in a bulk solution is in dynamic equilibrium with the adsorbate concentration at the adsorbent interface (Ho and Mckay, 2000). Two adsorption isotherm models, Langmuir and Freundlich equations, were further used to simulate the change of adsorption capacity of shell powder at different initial concentrations of Congo red. The Freundlich model assumes the presence of multiple layers of adsorption sites, and the activity of the adsorption sites is not homogeneous (Li et al., 2015). The equation is:

| $ \log {Q_{\text{e}}} = \log {k_{\text{f}}} + \frac{1}{n}\log {C_{\text{e}}}, $ | (4) |

where Ce (mg L–1) is the concentration of Congo red at adsorption equilibrium, Qe (mg g–1) is the adsorbed amount at the corresponding equilibrium concentration, while n and kf (L g–1) are the heterogeneity factor and Freundlich constant, respectively. The kf and n values are determined by fitting a linear relationship to a graph with logCe and logQe as horizontal and vertical coordinates, respectively.

The Langmuir model assumes homogeneous adsorption site adsorption and describes homogeneous adsorption in monomolecular layers (Langmuir, 1916). The equation is:

| $ \frac{{{C_{\text{e}}}}}{{{Q_{\text{e}}}}} = \frac{{{C_{\text{e}}}}}{{{Q_{\max }}}} + \frac{1}{{{K_{\text{L}}}{Q_{\max }}}}, $ | (5) |

where Qmax (mg g–1) is the maximum adsorption capacity, and KL (L g–1) is the equilibrium constant. The Qmax and KL values are determined by fitting a linear relationship to a graph with Ce and Ce/Qe as horizontal and vertical coordinates, respectively.

2.6 Statistical AnalysesThe statistical evaluation was performed using the SPSS 27.0 software package. The data are presented as the mean ± the standard deviation of three repetitions. No significant differences were found between groups sharing the same letters. Different letters indicated significant differences in multiple comparisons between groups.

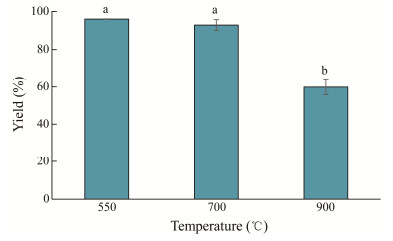

3 Results and Discussion 3.1 Characterization of Calcined M. edulis Shell PowderFig.1 displays the impact of various calcination temperatures on M. edulis shell mass. The shell powder yields were 96% and 92% after calcination at 550℃ and 700℃, respectively. Both of these temperatures just had a negligible effect on changes in shell mass. However, the calcination treatment at 900℃ had a more significant impact on the residue of the shell, resulting in a yield of 60% after calcination.

|

Fig. 1 Shell yields of M. edulis at different calcination temperatures. |

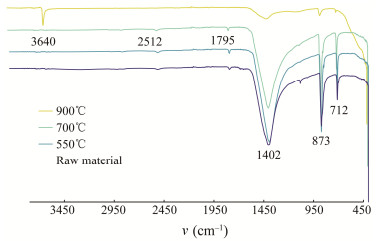

The structural changes in shell powder were characterized using FTIR. Fig.2 shows that the absorption peak at 2512 cm–1 is caused by the vibration of C-H containing organic matter in the uncalcined feedstock. The 1795 cm–1 and 1402 cm–1 peaks correspond to the antisymmetric stretching vibrations of CO32–. The peaks at 712 cm–1 and 873 cm–1 correspond to the in-plane bending vibration and out-of-plane bending vibration of CO32–, respectively (Wu et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2024). In comparison, the peak observed at 2512 cm–1 disappeared after calcination at 900℃, indicating complete degradation of the organic matter at this temperature. The primary constituent of shell powder is CaCO3. The disappearance of the CO32– peak after calcination is primarily due to its conversion to CaO. The 1795 cm–1 and 712 cm–1 peaks persisted after calcination at 550℃ and 700℃ but vanished after calcination at 900℃. After calcination at 900℃, the heights of the peak at 1402 cm–1 and the peak at 873 cm–1 were significantly reduced. These results suggest that shell powder calcined at 550℃ and 700℃ was primarily composed of a mixture of CaCO3 and CaO. At 900℃, CaCO3 decomposed almost entirely into CaO. Furthermore, the shell powder calcined at 900℃ exhibits a significant peak at 3640 cm–1, which was absent in the remaining three shell powders. This peak corresponds to the free-OH stretching vibration. This is because CaO reacts readily with H2O in air to form Ca(OH)2. Therefore, the spectrum of calcined shell powder exhibits a characteristic -OH peak. This group shows good hygroscopicity (Parvin et al., 2019). In comparison with shells treated with 1 mol L–1 KOH at 80℃ (Malik et al., 2020), it was found that the calcined shells in this case had a more complete removal of organic matter. As a result, their pores are more numerous, and their adsorption capacity is relatively higher.

|

Fig. 2 FTIR spectra of four kinds of M. edulis shell powder before and after calcination. |

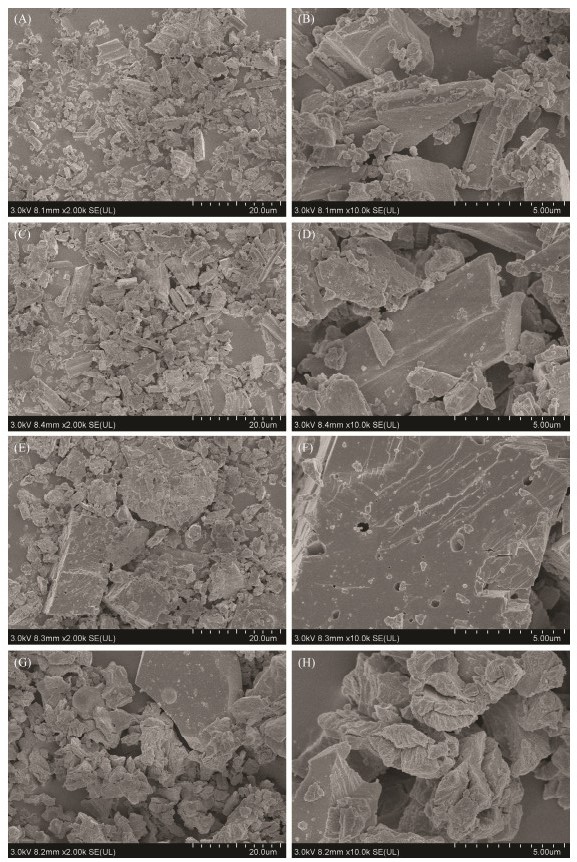

The adsorption capacity of an adsorbent depends not only on the chemical reactivity of the surface functional groups but also on its porosity. The morphological structure of shell powder was measured using SEM as presented in Fig.3. From Figs.3(A) and (B), the raw material of the M. edulis shell powder before calcination is rod-shaped. It has a tighter structure and a smoother surface with almost no pores. Figs.3(C) and (D) show there is no significant change in the M. edulis shell powder after being calcined at 550℃ compared to the raw material. It has a rougher surface after calcination. Figs.3(E) and (F) show that after calcination at 700℃, M. edulis shell powder contains a higher number of micropores, with fuzzy angles and a loose texture. Figs.3(G) and (H) show the morphological structure of shell powder with calcination treatment at 900℃. Its surface is rough and has a loose organization with a significantly increased specific surface area and many pore structures. The FTIR results indicate that CaCO3 from the shell decomposed and released CO2 due to the high temperature of 900℃. And the high temperature causes the organic matter to decompose, creating a complex and porous structure on the surface. These results are also in accordance with the significantly decreased yield of shells calcined at 900℃ as shown in Fig.1.

|

Fig. 3 SEM of M. edulis shell raw material (A, B), and shell powders at 550℃ (C, D); 700℃ (E, F), and 900℃ (G, H). |

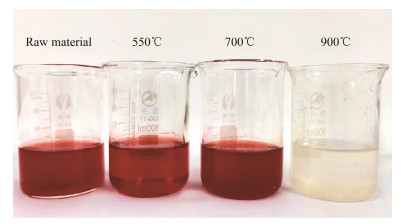

The shells underwent modification through calcination at 550℃, 700℃, and 900℃. Subsequently, experiments were conducted to determine the adsorption of Congo red dye to the modified shells. Fig.4 shows the supernatant obtained after centrifugation. There was no significant dye adsorption observed for shell powder calcined at 550℃ and 700℃ in comparison to uncalcined shell powder. The adsorption capacity of the raw shell material and shells with calcination at 550℃ and 700℃ are 10.77, 21.54, and 11.84 mg g–1, respectively. In contrast, the adsorption of Congo red by shell powder calcined at 900℃ was highly increased and the Congo red solution almost become colorless. Fig.5 shows more than 90% of Congo red has been removed from aqueous solution by calcinated shell powder at 900℃ according to the absorbance difference before and after adsorption treatment. In combination with the SEM and FTIR results, shell powder calcined at 900℃ showed a large pore size and adsorption surface area. Its distinctive O-H bond also may facilitate hydrogen bonding with Congo red molecules, enhancing its adsorption (Yen and Li, 2015). Thus shell powder calcined at 900℃ was selected for further study.

|

Fig. 4 Adsorption of Congo red using M. edulis shell powder without calcintion or calcined at different temperatures: raw material, 550℃, 700℃, and 900℃. |

|

Fig. 5 Scavenging effect of Congo red adsorbed using M. edulis shell powders without calcintion or calcinated at different temperatures: raw material, 550℃, 700℃, and 900℃. |

Fig.6 illustrates the fluctuation of the adsorption capacity of shell powder calcined at 900℃ for Congo red at various time intervals. In the first 10 min, shell powder removed about 77.6% of the Congo red. Then, the rate of adsorption slows down as time increases. This might be because the surface active sites of the adsorbent decrease with decreasing concentration of Congo red. The equilibrium for adsorption was achieved after 150 min, after which the adsorption equilibrium was established and the adsorption capacity remained constant at 112.1 mg g–1 of Congo red. After the equilibrium, 96.2% of Congo red in the solution was adsorbed onto calcined shell powder. It is observed that the adsorption process consists of two stages. The first stage was very fast within the first 10 min, which corresponded to the surface adsorption. In the second stage (10 – 150 min), the adsorption capacity still increased but it has been slowly. Intra-particle diffusion is supposed to occur in this stage (Qadeer, 2012). The potential practical application of M. edulis shell powder is demonstrated by its fast adsorption rate.

|

Fig. 6 Adsorption capacity of M. edulis shell powder for Congo red at different time. |

Adsorption kinetics studies are informative to elucidate the nature of adsorption process. The results of fitting the adsorption kinetic model can be observed in Figs.7(a) and (b), as well as Table 1. The pseudo-first-order kinetic model showed a low correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.8111), indicating a poor model fit. The correlation coefficient of the pseudo-second-order kinetic model was much higher (R2 = 0.9976), indicating an agreement between the pseudosecond-order kinetic model and the adsorption process. The calculated adsorption capacity Qe (112.4 mg g–1) also closely matches the experimental value (112.1 mg g–1). The results suggest that chemisorption plays a role in the adsorption process through electron sharing or exchange between adsorbent and adsorbate (El Jery et al., 2024).

|

Fig. 7 Curve of the pseudo-first-order kinetics (a) and pseudo-second-order kinetics model (b) for the adsorption of Congo red on calcinated M. edulis shell powder. |

|

|

Table 1 Kinetic model parameters of Congo red adsorption on calcinated M. edulis shell powder |

Adsorption behavior of shell powder may be influenced by temperature depending on the property of the adsorbate and adsorbent. Effect of temperature on the adsorption and the adsorption isotherms of shell powder on Congo red were obtained at 25℃, 35℃, and 40℃ in Fig.8. It is demonstrated that the adsorption capacity of Congo red on shell powder at equilibrium decreases as the temperature increases. The results suggest that the adsorption is an exothermic process. Additionally, it appears that adsorption at 25℃ is more effective, which is also favorable for practical application.

|

Fig. 8 Adsorption isotherm (a) of Congo red by calcinated M. edulis shell powder and Langmuir model simulation of adsorption isotherms (b) as well as Freundlich model simulation of adsorption isotherms (c). |

The adsorption isotherm model fit results are presented in Figs.8(b) and (c), as well as in Table 2. The Freundlich model showed good correlation coefficients ranging from 0.9598 to 0.9980 at the three temperatures, which obviously outperformed the Langmuir model. The results suggest that the adsorption process is multiphase, and each active site binds multiple molecules of the adsorbent simultaneously. Both physical and chemical adsorption are present, with chemical adsorption being the primary form. The parameter n represents the reactivity and heterogeneity of the active sites of the adsorbent. If n = 1, adsorption follows a linear pattern. If n > 1, the adsorption process is primarily chemical (Conde-Cid et al., 2019). The value of n ranges from 1 to 10 for favorable adsorption (Bhaumik et al., 2012). At the three temperatures, the adsorption is multiphase favorable adsorption with inhomogeneous adsorption sites, where 1 < n < 10. The FTIR data indicate that the primary functional group present in the adsorbent is -OH. The adsorbate is removed from the aqueous solution by the adsorbent through various interactions, such as hydrogen bonding and electron interactions. At the same time, the porous structure enhances the surface diffusion rate. The reaction takes place within 10 min, and results in a high adsorption efficiency.

|

|

Table 2 Parameters of adsorption isotherm of Congo red on calcinated M. edulis shell powder |

In particular, at 25℃ and an initial concentration of 2500 mg L–1 Congo red, M. edulis shell powder exhibited a very high adsorption capacity of 1015 mg g–1, as shown in Fig. 8(a). The adsorption capacity may also be increased if a higher initial concentration of Congo red is used. This data showed huge potential of M. edulis shell powder in the application of dye removal. Malik et al. (2020) used 0.5 g of modified rice husk to adsorb 1000 mg L–1 of Congo red, achieving an adsorption ratio of 92.3%. In this case, M. edulis shell powder adsorbed 87.8% of 1000 mg L–1 Congo red (Fig.8(a)), but only 0.1 g absorbent was used in our experiments. The M. edulis shell powder seems to have a comparable or even higher adsorption capacity compared to rice husk. It is also much higher than the adsorption capacity of potato peel powder, while only 72% of the 30 mg L–1 Congo red was removed using 0.6 g of potato peel powder (Akram and Javed, 2023). Additionally, Zhou et al. (2018) treated shrimp shells with NaOH to obtain a modified adsorbent for Congo red, but its maximum adsorption capacity is just 288.2 mg g–1. In the meanwhile, producing modified shrimp shells requires a large amount of water to be repeatedly rinsed until neutral. This process is also cumbersome and has negative impacts on environment. Some new materials were also synthesized to adsorb Congo red. For example, Sakshi et al. (2023) prepared a Chitosan/Moringa oleifera gum hydrogel but its Qmax for Congo red is only 50.25 mg g–1, which is significantly lower than that of M. edulis shell powder in this study. In another experiment, the Ackee apple seed-bentonite composite was tested to adsorb Congo red, with a relatively high Qmax of 1439.9 mg g–1 (Adebayo et al., 2020). However, preparing adsorbents requires significant raw materials and is of high-cost. In contrast, the process preparing the M. edulis shell adsorbent is simple and inexpensive. This shows that M. edulis shell is a promising adsorbent for the removal of Congo red dye.

4 Conclusions1) The adsorption of Congo red was the highest in shell powder that was calcined at 900℃. At equilibrium, 96.2% of the Congo red in the solution is adsorbed. 2) The adsorption process follows the pseudo-second-order model, indicating the presence of chemisorption. 3) The adsorption of Congo red on M. edulis shell powder is exothermic, and lower temperatures promote the adsorption process. At 25℃, M. edulis shell powders showed at least adsorption capacity of 1015 mg g−1. The adsorption isotherm is consistent with the Freundlich model, indicating multiphase-favorable adsorption. Mussel shell powder calcinated at 900℃ can be employed in adsorbing Congo red dye.

AcknowledgementsThis study was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2023YFD2401105), and the Fujian Science and Technology Planning Project-STS Program (No. 2021T3013).

Author Contributions

Xin Wang, methodology, data analysis, raw material preparation, writing-original draft, data curation writing-review and editing. Xiangyun Ge and Siqi Zhu, software and surveys. Weixiang Liu, raw material preparation. Ronge Xing, supervision and funding acquisition. Pengcheng Li, administration and supervision. Kecheng Li, conceptualization, investigation, data analysis, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, funding acquisition, supervision, project administration.

Data Availability

The data and references presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Acemioğlu, B., 2005. Batch kinetic study of sorption of methylene blue by perlite. Chemical Engineering Journal, 106(1): 73-81. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2004.10.005 (  0) 0) |

Adebayo, M. A., Adebomi, J. I., Abe, T. O., and Areo, F. I., 2020. Removal of aqueous Congo red and malachite green using ackee apple seed-bentonite composite. Colloid and Interface Science Communications, 38: 100311. DOI:10.1016/j.colcom.2020.100311 (  0) 0) |

Adebayo, M. A., Jabar, J. M., Amoko, J. S., Openiyi, E. O., and Shodiya, O. O., 2022. Coconut husk-raw clay-Fe composite: Preparation, characteristics and mechanisms of Congo red adsorption. Scientific Reports, 12(1): 14370. DOI:10.1038/s41598-022-18763-y (  0) 0) |

Akram, S., and Javed, T., 2023. Capability of potato peel powder (PPP) for the adsorption of hazardous anionic Congo dye. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology, 45(1): 1-14. DOI:10.1080/01932691.2022.2125006 (  0) 0) |

Bhaumik, R., Mondal, N. K., Das, B., Roy, P., Pal, K. C., Das, C., et al., 2012. Eggshell powder as an adsorbent for removal of fluoride from aqueous solution: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. E-Journal of Chemistry, 9(3): 1457-1480. (  0) 0) |

Cao, J., Ju, P., Chen, Z., Dou, K., Li, J., Zhang, P., et al., 2023. Trash to treasure: Green synthesis of novel Ag2O/Ag2CO3 Z-scheme heterojunctions with highly efficient photocatalytic activities derived from waste mussel shells. Chemical Engineering Journal, 454: 140259. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2022.140259 (  0) 0) |

Cao, Y. L., Pan, Z. H., Shi, Q. X., and Yu, J. Y., 2018. Modification of chitin with high adsorption capacity for methylene blue removal. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 114: 392-399. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.03.138 (  0) 0) |

Chen, B., Liu, Y., Chen, S., Zhao, X., Yue, W., and Pan, X., 2016. Nitrogen-rich core/shell magnetic nanostructures for selective adsorption and separation of anionic dyes from aqueous solution. Environmental Science: Nano, 3(3): 670-681. DOI:10.1039/C6EN00022C (  0) 0) |

Conde-Cid, M., Ferreira-Coelho, G., Arias-Estevez, M., Alvarez-Esmoris, C., Nóvoa-Muñoz, J. C., Nunez-Delgado, A., et al., 2019. Competitive adsorption/desorption of tetracycline, oxytetracycline and chlortetracycline on pine bark, oak ash and mussel shell. Journal of Environmental Management, 250: 109509. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109509 (  0) 0) |

Cui, M., Li, Y., Sun, Y., Wang, H., Li, M., Li, L., et al., 2021. Study on adsorption performance of MgO/Calcium alginate composite for Congo red in wastewater. Journal of Polymers and the Environment, 29(12): 3977-3987. DOI:10.1007/s10924-021-02170-x (  0) 0) |

Dai, L., Zhu, W., He, L., Tan, F., Zhu, N., Zhou, Q., et al., 2018. Calcium-rich biochar from crab shell: An unexpected super adsorbent for dye removal. Bioresource Technology, 267: 510-516. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2018.07.090 (  0) 0) |

Dinh, V. P., Huynh, T. D. T., and Le, H. M., 2019. Insight into the adsorption mechanisms of methylene blue and chromium (Ⅲ) from aqueous solution onto pomelo fruit peel. RSC Advances, 9: 25847-25860. DOI:10.1039/C9RA04296B (  0) 0) |

dos Santos, D. C., Adebayo, M. A., Pereira, S. D. P., Prola, L. D. T., Cataluña, R., Lima, E. C., et al., 2014. New carbon composite adsorbents for the removal of textile dyes from aqueous solutions: Kinetic, equilibrium, and thermodynamic studies. Korean Journal of Chemical Engineering, 31: 1470-1479. DOI:10.1007/s11814-014-0086-3 (  0) 0) |

El Jery, A., Alawamleh, H. S. K., Sami, M. H., Abbas, H. A., Sammen, S. S., Ahsan, A., et al., 2024. Isotherms, kinetics and thermodynamic mechanism of methylene blue dye adsorption on synthesized activated carbon. Scientific Reports, 14(1): 970. DOI:10.1038/s41598-023-50937-0 (  0) 0) |

Extross, A., Waknis, A., Tagad, C., Gedam, V. V., and Pathak, P. D., 2023. Adsorption of congo red using carbon from leaves and stem of water hyacinth: Equilibrium, kinetics, thermodynamic studies. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 20(2): 1607-1644. DOI:10.1007/s13762-022-03938-x (  0) 0) |

Hannan, F., Huang, Q., Farooq, M. A., Ayyaz, A., Ma, J., Zhang, N., et al., 2021. Organic and inorganic amendments for the remediation of nickel contaminated soil and its improvement on Brassica napus growth and oxidative defense. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 416: 125921. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125921 (  0) 0) |

Ho, Y. S., and McKay, G., 1999. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochemistry, 34(5): 451-465. DOI:10.1016/S0032-9592(98)00112-5 (  0) 0) |

Ho, Y. S., and McKay, G., 2000. Correlative biosorption equilibria model for a binary batch system. Chemical Engineering Science, 55(4): 817-825. DOI:10.1016/S0009-2509(99)00372-3 (  0) 0) |

Kismir, Y., and Aroguz, A. Z., 2011. Adsorption characteristics of the hazardous dye Brilliant Green on Saklıkent mud. Chemical Engineering Journal, 172(1): 199-206. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2011.05.090 (  0) 0) |

Langmuir, I., 1916. The constitution and fundamental properties of solids and liquids. Part Ⅰ. Solids. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 38(11): 2221-2295. DOI:10.1021/ja02268a002 (  0) 0) |

Li, K. C., Liu, S., Xing, R. E., Yu, H. H., Qin, Y. K., and Li, P. C., 2015. Liquid phase adsorption behavior of inulin-type fructan onto activated charcoal. Carbohydrate Polymers, 122: 237-242. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.01.019 (  0) 0) |

Li, X. D., and Zhai, Q. Z., 2023. Study on the adsorption of Cr3+ by peanut shell: Adsorption kinetics, thermodynamics, and isotherm properties. Chemistry and Biodiversity, 20 (6): e202201095.

(  0) 0) |

Malik, A., Khan, A., Anwar, N., and Naeem, M., 2020. A comparative study of the adsorption of Congo red dye on rice husk, rice husk char and chemically modified rice husk char from aqueous media. Bulletin of the Chemical Society of Ethiopia, 34(1): 41-54. DOI:10.4314/bcse.v34i1.4 (  0) 0) |

Nangia, S., Katyal, D., and Warkar, S. G., 2023. Thermodynamics, kinetics and isotherm studies on the removal of anionic Azo-dye (Congo red) using synthesized Chitosan/Moringa oleifera gum hydrogel composites. Separation Science and Technology, 58(1): 13-28. DOI:10.1080/01496395.2022.2104731 (  0) 0) |

Paluch, D., Bazan-Wozniak, A., Wolski, R., Nosal-Wiercińska. A., and Pietrzak, R., 2023. Removal of methyl red from aqueous solution using biochar derived from fennel seeds. Molecules, 28(23): 7786. DOI:10.3390/molecules28237786 (  0) 0) |

Parvin, S., Biswas, B. K., Rahman, M. A., Rahman, M. H., Anik, M. S., and Uddin, M. R., 2019. Study on adsorption of Congo red onto chemically modified egg shell membrane. Chemosphere, 236: 124326. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.07.057 (  0) 0) |

Popoola, T. J., Okoronkwo, A. E., Oluwasina, O. O., and Adebayo, M. A., 2021. Preparation, characterization, and application of a homemade graphene for the removal of Congo red from aqueous solutions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(37): 52174-52187. DOI:10.1007/s11356-021-14434-z (  0) 0) |

Qin, L., Zhou, Z., Dai, J., Ma, P., Zhao, H., He, J., et al., 2016. Novel N-doped hierarchically porous carbons derived from sustainable shrimp shell for high-performance removal of sulfamethazine and chloramphenicol. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers, 62: 228-238. DOI:10.1016/j.jtice.2016.02.009 (  0) 0) |

Qadeer, R., 2013. Kinetic models applied to erbium adsorption on activated charcoal from aqueous solutions. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry, 295: 1051-1055. DOI:10.1007/s10967-012-1936-2 (  0) 0) |

Rodríguez-Arellano, G., Barajas-Fernández, J., García-Alamilla, R., Lagunes-Gálvez, L. M., Lara-Rivera, A. H., and García-Alamilla, P., 2021. Evaluation of cocoa beans shell powder as a bioadsorbent of Congo red dye aqueous solutions. Materials, 14(11): 2763. DOI:10.3390/ma14112763 (  0) 0) |

Sicuro, B., 2021. World aquacult diversity: Origins and perspectives. Reviews in Aquaculture, 13(3): 1619-1634. DOI:10.1111/raq.12537 (  0) 0) |

Soni, S., Bajpai, P. K., Mittal, J., and Arora, C., 2020. Utilisation of cobalt doped iron based MOF for enhanced removal and recovery of methylene blue dye from waste water. Journal of Molecular Liquids, 314: 113642. DOI:10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113642 (  0) 0) |

Srichanachaichok, W., and Pissuwan, D., 2023. Micro/nano structural investigation and characterization of mussel shell waste in Thailand as a feasible bioresource of CaO. Materials, 16(2): 805. DOI:10.3390/ma16020805 (  0) 0) |

Srilakshmi, C., and Saraf, R., 2016. Ag-doped hydroxyapatite as efficient adsorbent for removal of Congo red dye from aqueous solution: Synthesis, kinetic and equilibrium adsorption isotherm analysis. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials, 219: 134-144. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2015.08.003 (  0) 0) |

Taha, K. K., Al Zoman, M., Al Outeibi, M., Alhussain, S., Modwi, A., and Bagabas, A. A., 2019. Green and sonogreen synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles for the photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue in water. Nanotechnology for Environmental Engineering, 4: 1-11. DOI:10.1007/s41204-018-0045-z (  0) 0) |

Tang, J., Zhang, Y. F., Liu, Y., Li, Y., and Hu, H., 2020b. Efficient ion-enhanced adsorption of Congo red on polyacrolein from aqueous solution: Experiments, characterization and mechanism studies. Separation and Purification Technology, 252: 117445. DOI:10.1016/j.seppur.2020.117445 (  0) 0) |

Tang, K., Li, Y., Zhang, X., Li, M., Du, Q., Li, H., et al., 2020a. Synthesis of citric acid modified β-cyclodextrin/activated carbon hybrid composite and their adsorption properties toward methylene blue. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 137(4): 48315. DOI:10.1002/app.48315 (  0) 0) |

Trinh, H. N., Nguyen, T. C., Tran, D. M. T., Ngo, T. C. Q., Phung, T. L., Nguyen, T. D., et al., 2023. Investigation on methylene blue dye adsorption in aqueous by the modified Mussel shells: Optimization, kinetic, thermodynamic and equilibrium studies. Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 111(4): 46. DOI:10.1007/s00128-023-03793-7 (  0) 0) |

Velkova, Z. Y., Kirova, G. K., Stoytcheva, M. S., and Gochev, V., 2018. Biosorption of Congo red and methylene blue by pretreated waste Streptomyces fradiae biomass – Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society, 83(1): 107-120. DOI:10.2298/JSC170519093V (  0) 0) |

Wang, Q., Jiang, F., Ouyang, X. K., Yang, L. Y., and Wang, Y., 2021. Adsorption of Pb(Ⅱ) from aqueous solution by mussel shell-based adsorbent: Preparation, characterization, and adsorption performance. Materials, 14(4): 741. DOI:10.3390/ma14040741 (  0) 0) |

Wang, S., Boyjoo, Y., Choueib, A., and Zhu, Z. H., 2005. Removal of dyes from aqueous solution using fly ash and red mud. Water Research, 39(1): 129-138. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2004.09.011 (  0) 0) |

Wu, M., Zhang, Y., Feng, X., Yan, F., Li, Q., Cui, Q., et al., 2023. Fabrication of cationic cellulose nanofibrils/sodium alginate beads for Congo red removal. Iscience, 26(10): 107783. DOI:10.1016/j.isci.2023.107783 (  0) 0) |

Wu, S., Liang, L., Zhang, Q., Xiong, L., Shi, S., Chen, Z., et al., 2022. The ion-imprinted oyster shell material for targeted removal of Cd(Ⅱ) from aqueous solution. Journal of Environmental Management, 302: 114031. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.114031 (  0) 0) |

Yen, H. Y., and Li, J. Y., 2015. Process optimization for Ni(Ⅱ) removal from wastewater by calcined oyster shell powders using Taguchi method. Journal of Environmental Management, 161: 344-349. (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Y., Li, A., Tian, T., Zhou, X., Liu, Y., Zhao, M., et al., 2024. Preparation of amino functionalized magnetic oyster shell powder adsorbent for selective removal of anionic dyes and Pb(Ⅱ) from wastewater. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules, 260: 129414. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.129414 (  0) 0) |

Zhou, Y., Ge, L., Fan, N., and Xia, M., 2018. Adsorption of Congo red from aqueous solution onto shrimp shell powder. Adsorption Science and Technology, 36(5-6): 1310-1330. DOI:10.1177/0263617418768945 (  0) 0) |

Zhou, Y., Lu, J., Zhou, Y., and Liu, Y., 2019. Recent advances for dyes removal using novel adsorbents: A review. Environmental Pollution, 252: 352-365. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.05.072 (  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 24

2025, Vol. 24