River deltas are typical geomorphic landforms created by the interaction between river and ocean dynamics, providing adequate water resources and sediment-associated resources for numerous major cities worldwide (Dai et al., 2018). In general, the morphological changes of river deltas critically depend on the amount of river input, including the water discharge and sediment load delivered to the sea and the coastal environment of the receiving sea. Owing to the spatiotemporal differences in water discharge, sediment load, waves, tides, and Coriolis force among different estuaries and coasts, multiple deltas with distinct geomorphic features are formed (Anthony, 2015; Finotello et al., 2019).

The deposition space of the delta plain and coastal area for the sediment delivered into the sea is crucial for the formation and evolution of river deltas. For deltas without enough deposition space, rivers expand their deposition space by diverting into multiple estuaries, such as the Mississippi River Delta, or constantly changing the estuary position, such as the Yellow River Delta (YRD) (Peng et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2017a; Wu et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2019). The deposition space for sediments is closely related to the movement of the relative sea level (RSL), which is determined by the combined effect of the changes in ocean water volume (eustasy) and the vertical displacements of land (isostasy) (Jørn et al., 2015; Tran et al., 2022). Therefore, the causes of the RSL movement and its influence on the dynamic geomorphology of deltas have attracted attention during recent decades (Peltier, 2001; Peltier and Fairbanks, 2006; Dean et al., 2019). The spatiotemporal differences in RSL movements can reflect a variety of geophysically and climatologically driven processes (Carter, 1988; Maher and Harvey, 2008). Reconstructing the RSL curve will provide additional information about the geomorphological dynamics around coastal regions in the past and support the prediction of future RSL movements due to global warming.

The modern YRD is characterized by adequate sediment input, a relatively weak tidal regime, and frequent migratory estuaries (Zheng et al., 2018). Its geomorphic evolution is closely related to the inflow conditions of the Yellow River Estuary, which is different from that of deltas suffering from a strong tidal current, such as the Changjiang (Dai et al., 2015). Therefore, the migrations of the Yellow River Estuary in the last 2000 years yield significant influences on the evolution of the YRD. Owing to the constant interaction between the river and ocean dynamics in the last 2000 years, the YRD is now composed of several subdeltas downstream Linjin, including current subdeltas, abandoned surface subdeltas, and shallow-buried deltas (Xue, 1993; Bi et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022). In recent decades, extensive studies have been conducted on the morphological evolution of the YRD, including coastline migration, land area changes in the subaerial delta, and the relationship between morphological evolution and river input (Chu, 2014; Zhou et al., 2014; Jiang et al., 2017; Fan et al., 2018). However, the time scale of these studies is mainly tens to hundreds of years. Only a few works focused on understanding the effect of RSL changes on the evolution of YRD in the last 2000 years due to the lack of geological markers indicating the long-term movements of RSL. Therefore, the objectives of the present study are as follows: 1) to determine the positions of sea level during different periods in the last 2000 years by employing boreholes in the YRD that record paleo-coastline migration; 2) to reconstruct the curve of RSL movements in the last 2000 years; and 3) to evaluate the causes and geomorphic effects of RSL movements. The insights gained from this study would aid in comprehensively understanding the geomorphic evolution of the YRD and lay a foundation for predicting the geomorphic evolution of the YRD under the influences of RSL movements and variations in river inputs in the future.

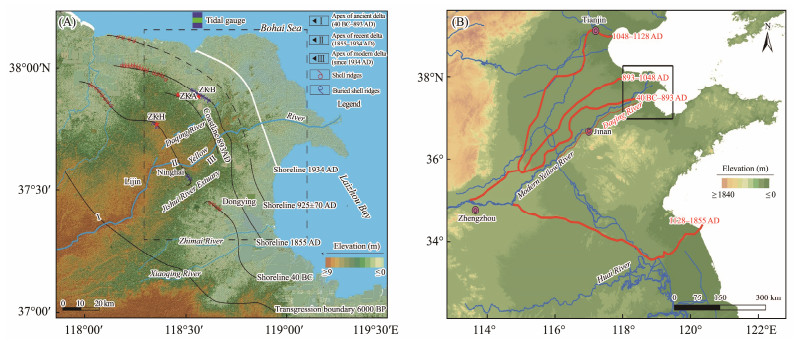

2 Regional Setting 2.1 Geomorphological Evolution of the Yellow River DeltaAs the second largest river in China, the Yellow River originates from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and flows through the Loess Plateau, North China Plain, and finally into the Bohai Sea. After the diversion of the lower Yellow River in 1855, its main channel has generally flowed northeastward, forming a fan-shaped modern YRD (Fig.1). With Ninghai at its vertex, the modern YRD starts from the mouth of the Tao'er River in the north and ends at the mouth of the Zhimai River in the south. Its terrain is mostly flat, although its elevation decreases along the river channel toward the sea (SW-NE). The elevation of the river channel is higher than both of its sides and approximately 2 m higher than the Tao'er River Plain and Xiaoqing River Plain. The modern YRD is located west of the Tancheng-Lujiang fault, a quaternary active fault, and its neotectonic structure is characterized by continuous subsidence, forming a thick basement of Cenozoic loose clastic sediments.

|

Fig. 1 Sketch map of the Yellow River Delta: (A) geomorphological evolution of the YRD in the last 2000 years; (B) migrations of the Yellow River Estuary in the last 2000 years. |

The Yellow River is famous for its high sediment concentration and frequent migration of lower courses. The abundant sediment of the Yellow River mainly comes from the Loess Plateau, which mainly controls the types and distribution characteristics of sediment in the delta and coastal area. During the last 2000 years, the sediment delivered to the delta has changed significantly. Its volume was approximately 1 × 108 t yr−1 during 40 BC – 893 AD, no sediment during 893 – 1855 AD, 16 × 108 t yr−1 during 1855 – 1959 AD, and 1.5 × 108 t yr−1 until 2021 AD.

With avulsions occurring frequently in the lower Yellow River, the YRD has had an intermittent development history since the Holocene maximum transgression (Hoitink et al., 2017; Gugliotta and Saito, 2019). Accompanied by the variations in the sediment delivered to the delta, the evolution of YRD can be divided into four periods: ancient YRD (40 BC – 893 AD), abandoned YRD (893 – 1855 AD), recent YRD (1855 – 1934 AD), and modern YRD (1934 AD – present) (Gao et al., 1989). The frequent abandonments and deposition discontinuity caused by the migrations of the Yellow River Estuary are the prominent features during the evolution of YRD, which includes several construction-destruction cycles in different space-time scales during the last 2000 years. The whole YRD experienced two construction periods (40 BC – 893 AD and 1855 BC to date) and a destruction period (893 AD – 1855 AD). On the subdelta scale, four abandoned subdeltas were found during 1934 – 1976 AD and two abandoned subdeltas since 1976 AD; the current subdelta was formed in 1996 AD (Wang et al., 2017b; Zhan et al., 2020).

2.2 Modern and Paleo ClimateThe modern YRD lies within the semihumid monsoon climate zone and has an annual average temperature of 11.7℃ – 12.6℃ and precipitation of 530 – 630 mm. The ocean hydrodynamics of the YRD are characterized by weak tides, strong waves, and frequent storm surges. The annual average wind speed is 3.1 – 4.6 m s−1, and gales (> 17 m s−1) are relatively frequent (Cheng and Gao, 2006). In the last 60 years, storm surges have occurred every 3 years, accompanied by strong winds, strong waves, torrents, and a rise of water level to approximately 2.11 – 5.74 m for 24 – 72 h during storm surges (Wang et al., 2016a). Strong storm surges were prevalent in the Bohai Sea during historical periods, and 43 catastrophic storm surges occurred during 40 BC – 1855 AD (Liu and Zhang, 1991). According to the δ18O and δ13C data recorded in the ky1 stalagmite located in the Kaiyuan Cave, 150 km southwest of Lijin, the YRD experienced Medieval Warm Period (MWP) with strong summer monsoon during 892 – 1482 AD and unstable Little Ice Age (LIA) with weak summer monsoon during 1482 – 1894 AD (Wang et al., 2015).

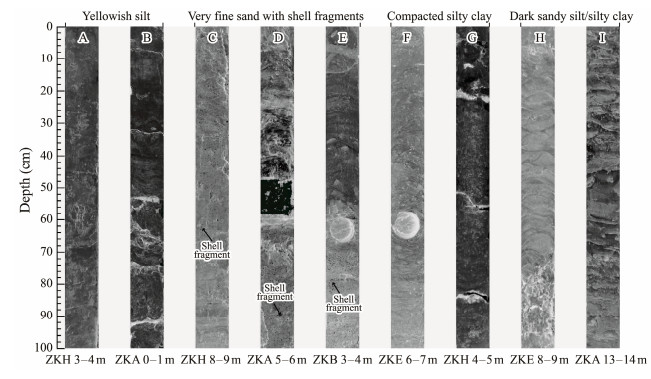

3 Methods and Data 3.1 Geological MarkersThree locations, namely, ZKA, ZKB, and ZKH, were selected for drilling in September 2018, as shown in Fig.1. The boreholes were acquired through the rotary drilling of a single pipe with a diameter of 100 mm. The collected sediment cores were sealed in segments and transported to the laboratory for describing lithology, taking photos, and sampling with an interval of 5 cm. In addition, 16 samples for OSL dating and 746 samples for particle size tests were collected from the three boreholes (Fig.2).

|

Fig. 2 Photographs of representative sedimentary facies of the drilling cores: (A, B) delta plain; (C – E) beach ridge; (F, G) abandoned delta plain; (H, I) delta front. |

In the three boreholes, OSL dating samples were obtained from the layers with high sand concentration by vertically inserting stainless steel metal tubes into the cores. These unexposed samples were pretreated under an infrared light environment by wet-sieving the components of 38 – 63 μm size from the unexposed sample, then adding 10% HCl and 30% H2O2 to remove carbonate and organic matter, adding 35% H2SiF6 to dissolve feldspar, and finally removing fluoride deposition with 10% HCl. The purity of the quartz grains was checked by infrared (IR, l = 830 nm) stimulation. Finally, the isolated quartz grains were mounted as medium-sized (6 mm) aliquots in the center of stainless steel disks using silicone oil.

The single-aliquot regenerative dose (SAR) protocol was used for equivalent dose (De) determination (Murray and Wintle, 2000). Luminescence was stimulated by blue LEDs (l = (470 ± 20) nm) at 130℃ for 40 s using a Risø TL/OSL-DA-20 reader with 90% diode power and detected using a 7.5 mm-thick U-340 filter (detection window 275 – 390 nm) in front of the photomultiplier tube. Irradiations were carried out using a 90Sr/90Y beta source in the reader. Preheat plateau test, dose recovery test, and recuperation ratio and recycling ratio analyses were conducted on representative samples to select a suitable preheat temperature and check the suitability of the SAR protocol.

U, Th, and K concentrations were measured by neutron activation analysis. Water content (mass of moisture/dry mass) was determined by weighing the sample before and after drying with ±5% uncertainties. Dose rates and OSL ages were calculated using the dose rate and age calculator (Durcan et al., 2015).

3.3 Grain Size TestsGrain size was measured using a Malvern Mastersizer 3000 laser grain size analyzer. The pretreatments included adding 10% H2O2 and 10% HCl to remove organic matter and secondary carbonate, adding 10 mL of 0.05 mol L−1 (NaPO3)6 dispersant, and finally ultrasonically vibrating for 10 min before testing.

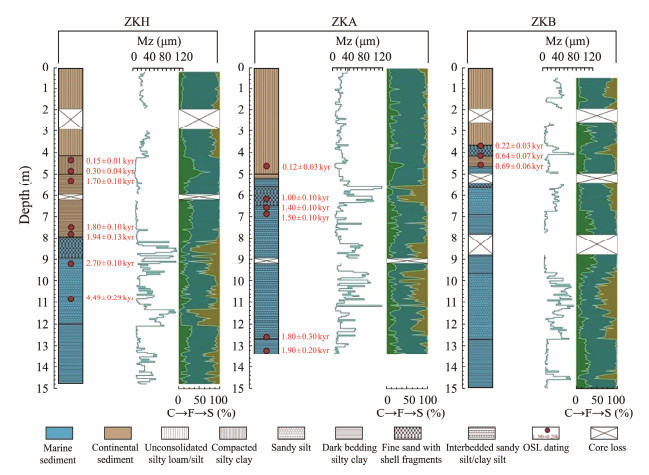

4 Results and Discussion 4.1 Sedimentary Characteristics of the YRDThree boreholes (ZKH, ZKA, and ZKB) were drilled, and the samples were tested to reveal the sedimentary characteristics of the northern YRD. As shown in Fig.3, the samples mainly contain silt (4 – 63 μm), and the mean grain size ranges from silt to very fine sand (63 – 125 μm). The proportion of clay (< 4 μm) is less than 20%, and that of very fine sand ranges from 0 to 90%. According to the lithologic description, the very fine sand layers with abundant shell debris can be found in the three sediment cores: ZKH (at a depth of 8 – 9 m, relative to the ground surface to the modern YRD, same hereinafter), ZKA (at a depth of 5.6 – 6.5 m), and ZKB (at a depth of 3.7 – 4.2 m). In the vertical direction, the sediments in the lower layers are mainly coarse gray-black sands with horizontal bedding, cross bedding, and wavy bedding, and the sediments in the upper layers are mainly yellow silt without clear bedding. These sedimentary characteristics indicate that the upper layers are continental deposits that possibly belong to delta-plain facies, and the lower layers are marine sediments that may be delta-front facies and prodelta facies. The vertical variations in the depositional environment sequences of the three boreholes are consistent with the depositional sequence of the buried shell ridge, which contains the underlying grayish layer of muddy lagoon sediments and the overlying layer of fluvial facies sediments. Therefore, the sediments of the three boreholes can represent the sedimentary sequences of the buried shell ridge.

|

Fig. 3 Particle size and OSL dating results of three boreholes in the YRD. |

The shell ridge is formed by the accumulation of marine facies shells under the interactions of land and ocean dynamics. On the landside of the shell ridge is a salt marsh that can be submerged by high tide, and on its seaside is the tidal flat. When the coastline migrates, the shell ridge remains at its location. Hence, the shell ridge can indicate the height of ancient sea level. The multiple shell ridges along the muddy coast of the YRD connect with the northern shell ridge in Tianjin City and Hebei Province, forming a unique shell ridge coast and an island chain. The formation and evolution of these shell ridges are closely related to the long-term subsidence tectonic unit and the deposition of the Yellow River. In the initial stage, the Yellow River carried a large amount of sediment into the delta, causing the high turbidness of the seawater and the low souring ability of waves and resulting in the formation of a wide and flat silty-muddy coast. Thereafter, the decline in sediment supply due to the migration of the Yellow River Estuary has prompted the relatively stable coastline and clear seawater, which contribute to the mass propagation of shellfish. Meanwhile, the strong tides and waves reshape the coast, transport the shells and their debris in the intertidal-neritic zone to the high tide line, and finally form the unique shell ridge along the coastline.

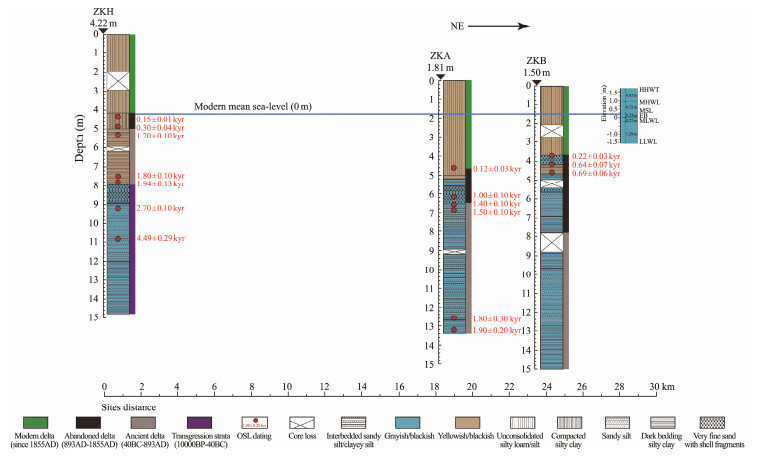

4.2 Formation Age of the Buried Shell RidgeSixteen samples were taken from the three boreholes for OSL dating to determine the formation age of the buried shell ridge. Among these samples, 3 were from the sand layer with shells, 7 from the underlying layers of lagoon facies sediments, 3 from the overlying layer of lagoon facies sediments, and 3 from the lower part of the overlying alluvium layer deposited by the modern Yellow River. According to the OSL dating results (Table 1) and the sedimentary characteristics, the sediment sequences of three boreholes can be divided into four units: transgressive sedimentary layer in Holocene (10000 BP – 40 BC), ancient YRD (40 BC – 893 AD), abandoned YRD (893 – 1855 AD), and modern YRD (1855 AD to date). The YRD has undergone the following transformations of its coastal types in the past 2000 years: tide-dominated silty coast (40 BC – 893 AD), wave-dominated sandy coast (893 – 1855 AD), and tide-dominated silty coast (1855 AD to date) (Wang et al., 2016b). The sand layers containing the shell fragments of ZKH, ZKA, and ZKB formed around 79 BC, 1019 AD, and 1800 AD, respectively. The formation ages of these sand layers indicate the location of the coastline at 1855 AD (ZKB), 893 AD (ZKA), and 40 BC (ZKH), respectively. Therefore, ZKH is located on the coastline of the sandy coast around 40 BC, before the formation of the ancient YRD. ZKA is located on the continental coastline of the initial abandoned YRD around 893 AD. ZKB is located on the coastline of the abandoned YRD before 1855 AD (Fig.4).

|

|

Table 1 OSL dating results of samples from three boreholes |

|

Fig. 4 Correlation of the drilling cores and the reconstructed geomorphology and sedimentary architecture of the shallow-buried abandoned Yellow River Delta. |

Compared with those in the area suffering from tectonic uplift, the markers for the location of paleo-coastline and paleo-sea surface in the subsidence area are relatively scarce. The shell ridge is a typical geomorphological marker. Surface and buried shell ridges can be found in the western area of the Bohai Sea. Their formations are related to the tidal flat erosion caused by the migration of estuary and the abandonment of delta (Wang et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2020). Previous studies on the shell ridge regarded its top as the location of the paleo-coastline and paleo-sea surface (Zhao, 1986; Angustinus, 1989). However, the use of the shell ridge as an indication of sea level and coastline causes uncertainty due to the complex relationship between the attributes of the shell ridge and tide and the subsequent external erosion or soil cementation. The shell ridges (ZKH, ZKA, and ZKB) in the present work are located on the landward side of the historical barrier-lagoon coast, which is well protected from storm surges. In addition, the shell ridges are buried by the sediments from the Yellow River or the intertidal silty sediments, preserving their original height. Therefore, the elevation of the buried shell ridges in our study is close to the mean high water level (MHWL) when these shell ridges are formed. To avoid errors in the absolute elevation of sea level indicated by the chenier shell ridge, we adopted the RSL for analyzing the movements of sea level in history. We tried to determine the location of the MHWL using the top elevation of the shell layer in the buried shell ridge and then reconstruct the movement of the RSL curve.

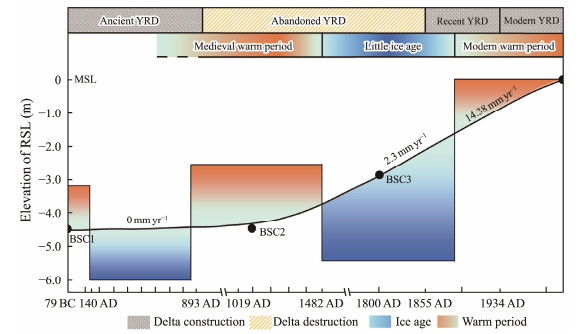

On the basis of the relationship between the MHWL and the mean water level (MWL) of the modern YRD, the MWL elevation in 79 BC, 1019 AD, and 1800 AD was calculated using the top elevation of the sand layer containing shell fragments. The MWL elevation relative to the modern sea level is approximately −4.52, −4.52, and −2.92 m in 79 BC, 1019 AD, and 1800 AD, respectively (Fig.5). The relative height differences are 0, 1.60, and 3.15 m during 79 BC – 1019 AD, 1019 AD – 1800 AD, and 1800 AD to date, respectively. These results indicate that the RSL was almost stagnant during 79 BC – 1019 AD and has risen significantly since 1019 AD. The average rise rate is 2.31 mm yr−1 during 1019 – 1800 AD and 14.38 mm yr−1 from 1800 AD to date. These results showed that the RSL of YRD experienced a continuous long-term rise during the last 2000 years, and its rise rate increased gradually since 1019 AD and significantly after 1800 AD.

|

Fig. 5 Movement curve of the relative sea level of the Yellow River Delta during the last 2000 years. |

The RSL in the YRD is almost stagnant during 79 BC – 1019 AD. This finding does not mean a lack of movement but rather a rise in the early stage and a decline in the later stage. Historical documents and archaeological records show that the RSL is 1.0 – 1.5 m higher than the modern sea level during 79 BC – 140 AD, leading to the large-scale transgression in the North China Plain along the YRD (Wang, 1998; Shang et al., 2015). Since the end of this transgression, the coast of the YRD has experienced regression, and its RSL has consequently declined. The sediment of the ZKE borehole, located 6 km to the east of the ZKA borehole, shows that it was still located in the sea in 719 AD. The coastline extrapolates to the location of the ZKA borehole in 893 AD. This regression occurred during the construction period of the ancient delta and lasted until around 1000 AD, although the ancient YRD was abandoned in 893 AD. Overall, the movement of RSL during 79 BC – 1019 AD is not significant due to its opposite movements in the early and late stages.

The slow rise of RSL during 1019 – 1800 AD is closely related to the reverse change of global climate during the LIA and MWP. According to the oxygen isotope records of Kaiyuan Cave stalagmite, the MWP has extended from 893 AD to 1482 AD, and the LIA has lasted until the early 20th century (Wang et al., 2016b). The RSL in the coast region of the YRD has increased during the MWP and decreased during the LIA. As revealed by the sediments of the ZKA borehole, located on the coastline of 893 AD, the shell layer was buried by the marine sediments formed around 1019 AD. This finding indicates that the coastline moved landward during 893 – 1019 AD due to the transgression during the MWP. Despite the effect of the transgression and the abandonment of the YRD, the coastline moved seaward until 1855 AD, implying the significant decline of the RSL during the LIA.

The significant rise of RSL after 1800 AD is mainly related to the warm period and global warming after the end of the LIA. Accompanied by the natural climate transformation from the LIA to the MWP, human activities have led to an increase in greenhouse gas concentrations, resulting in widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, oceans, and cryosphere since the Industrial Revolution. As a consequence, seawater has been warming and expanding, and terrestrial glaciers and polar ice sheets have been melting rapidly, especially in the last 40 years (Wang et al., 2023). Therefore, human activities also contribute to the significant rise of RSL since the Industrial Revolution.

4.4 Geomorphic Effect of RSL MovementThe RSL movement of the YRD rose during 40 BC – 140 AD but declined during 140 AD – 893 AD. The long reduction period of RSL was conducive to the transport of sediment from rivers into the sea, the extension of estuaries, and the long-term construction of deltas, all of which were important conditions for the long-term stability and development of ancient deltas. The decline of the RSL controlled the slope of the ancient delta. According to the elevation of the sand layer containing shell fragments in ZKH and ZKA, the slope was approximately 0.022‰ when the ancient delta was abandoned around 893 AD. The decline of RSL was beneficial for the stability of the lower reach and estuary of the Yellow River. An example is the long-term stability of the Yellow River since 69 AD when Jing Wang, a famous hydrologist in the Eastern Han Dynasty, prompted a series of regulation works.

The ancient YRD was abandoned during 893 AD – 1855 AD due to the migration of the Yellow River Estuary, and the abandoned delta thus suffered from the long-term RSL rise. As a consequence, the surface elevation of the abandoned delta declined, and the topography changed. The surface elevation of the ancient YRD decreased from southwest to northeast, and the modern YRD shows a similar pattern, while that of the abandoned delta in the SW-NE direction was low in the middle and high on both ends. In particular, the coastal elevation of the abandoned delta was 1.01 m higher than the middle part, causing an inverted slope of 0.144‰, leading to frequent diversions of the estuary and the continuous abandonment and formation of the subdeltas after 1855 AD.

The low-lying land of the delta has been filled continuously by the sediments carried by the Yellow River since 1855 AD. Eventually, the surface elevation of the modern YRD decreases from southwest to northeast with a slope of 0.075‰, which is approximately 3.5 times the critical slope (0.022‰) of the ancient YRD around 893 AD. The large surface gradient of the modern YRD is beneficial for the stability of the Yellow River Estuary, which approaches the equilibrium status between flow energy and sediment load. In addition, the sediment load of the Yellow River has decreased significantly, and the manual regulation of the river has been strengthened recently. Therefore, the Yellow River Estuary is relatively stable, and the modern YRD is far from being abandoned in the future. This finding provides a historical geomorphology basis for the management of the Yellow River Estuary.

5 ConclusionsOn the basis of the sediment sequence and OSL dating of boreholes in the YRD that record paleo-coastline migration, the positions of paleo-coastlines and the movements of RSL in the last 2000 years are reconstructed. The causes and geomorphic effects of RSL movements are then evaluated. The main results are as follows:

1) The sediment sequence of the YRD is divided into Holocene transgressive sedimentary layer (10000 BP – 40 BC), ancient YRD (40 BC – 893 AD), abandoned YRD (893 – 1855 AD), and modern YRD (1855 AD to date). The YRD coast has transformed from a tide-dominated silty coast (40 BC – 893 AD) to a wave-dominated sandy coast (893 – 1855 AD) and back to a tide-dominated silty coast (1855 AD to date) in the last 2000 years.

2) The sand layers consisting of shell fragments indicate the location of the coastline at 1855 AD, 893 AD, and 40 BC, and their top elevations can represent the corresponding MHWL. The sediment sequences of the three boreholes are consistent with the depositional sequence of the buried shell ridge in the YRD, which contains the underlying black layer of muddy lagoon sediments and the overlying layer of fluvial facies sediments.

3) The mean sea level elevations in 79 BC, 1019 AD, and 1800 AD relative to the modern mean sea level were approximately −4.52, −4.52, and −2.92 m, respectively. The RSL was almost stagnant during 79 BC – 1019 AD, rose slowly during 1019 – 1800 AD due to the reverse change of global climate from the LIA to the MWP, and rose significantly after 1800 AD due to the warm period.

4) The movements of RSL are conducive to the stability of the lower Yellow River and can control the slope of the YRD. The surface slope of YRD was approximately 0.022‰ at 893 AD, 0.144‰ at 1855 AD, and 0.075‰ recently. On the basis of these results, the modern YRD is far from being abandoned in the future. The findings provide a historical geomorphology basis for the management of the Yellow River Estuary.

AcknowledgementsThis work was supported financially by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 42330406 and 42476163). The authors would like to thank Mr. Cheng Dong and Mr. Feng Yin for their help with field sampling.

Author Contributions

Qing Wang and Chao Zhan contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Qing Wang, Chao Zhan, Teng Su and Xianbin Liu. The draft of the manuscript was written by Qing Wang, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its additional files.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Angustinus, P., 1989. Chenier and chenier plains: A general introduction. Marine Geology, 90: 219-229. DOI:10.1016/0025-3227(89)90126-6 (  0) 0) |

Anthony, E. J., 2015. Wave influence in the construction, shaping and destruction of river deltas: A review. Marine Geology, 361: 53-78. (  0) 0) |

Bi, N. S., Wang, H. J., Wu, X., Saito, Y., Xu, C. L., and Yang, Z. S., 2021. Phase change in evolution of the modern Huanghe (Yellow River) Delta: Process, pattern, and mechanisms. Marine Geology, 437: 106516. (  0) 0) |

Carter, R., 1988. Coastal Environments. Chapter 6: Sea-Level Changes. Elsevier, 253-267.

(  0) 0) |

Cheng, Y. J., and Gao, J., 2006. Analysis of hydrographic characteristics and changes in scour and silting in the Laizhou Bay area. Coastal Engineering, 25(3): 1-6. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-3682.2006.03.001 (  0) 0) |

Chu, Z., 2014. The dramatic changes and anthropogenic causes of erosion and deposition in the lower Yellow (Huanghe) River since 1952. Geomorphology, 216: 171-179. (  0) 0) |

Dai, Z., Liu, J., and Wen, W., 2015. Morphological evolution of the South Passage in the Changjiang (Yangtze River) estuary, China. Quaternary International, 380: 314-326. (  0) 0) |

Dai, Z., Mei, X., Darby, S. E., Lou, Y., and Li, W., 2018. Fluvial sediment transfer in the Changjiang (Yangtze) river-estuary depositional system. Journal of Hydrology, 566: 719-734. DOI:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2018.09.019 (  0) 0) |

Dean, S., Horton, B. P., Evelpidou, N., Cahill, N., Spada, G., and Sivan, D., 2019. Can we detect centennial sea-level variations over the last three thousand years in Israeli archaeological records?. Quaternary Science Reviews, 210: 125-135. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.02.021 (  0) 0) |

Durcan, J. A., King, G. E., and Duller, G. A. T., 2015. DRAC: Dose rate and age calculator for trapped charge dating. Quaternary Geochronology, 28: 54-61. DOI:10.1016/j.quageo.2015.03.012 (  0) 0) |

Fan, Y. S., Chen, S. L., Zhao, B., Pan, S., and Jiang, C., 2018. Shoreline dynamics of the active Yellow River Delta since the implementation of water-sediment regulation scheme: A remotesensing and statistics-based approach. Estuarine Coastal & Shelf Science, 200: 406-419. (  0) 0) |

Finotello, A., Lentsch, N., and Paola, C., 2019. Experimental delta evolution in tidal environments: Morphologic response to relative sea-level rise and net deposition. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 44(10): 2000-2015. DOI:10.1002/esp.4627 (  0) 0) |

Gao, S., Li, Y., An, F., Wang, Y., and Yan, F., 1989. Formation and Sedimentary Environment of the Yellow River Delta. Science Publishing Company, Beijing, 68-76.

(  0) 0) |

Gugliotta, M., and Saito, Y., 2019. Matching trends in channel width, sinuosity, and depth along the fluvial to marine transition zone of tide-dominated river deltas: The need for a revision of depositional and hydraulic models. Earth-Science Reviews, 191: 93-113. DOI:10.1016/j.earscirev.2019.02.002 (  0) 0) |

Hoitink, A. J. F., Wang, Z. B., Vermeulen, B., Huismans, Y., and Kästner, K., 2017. Tidal controls on river delta morphology. Nature Geoscience, 10(9): 637-645. DOI:10.1038/ngeo3000 (  0) 0) |

Jiang, C., Pan, S., and Chen, S., 2017. Recent morphological changes of the Yellow River (Huanghe) submerged delta: Causes and environmental implications. Geomorphology, 293: 93-107. DOI:10.1016/j.geomorph.2017.04.036 (  0) 0) |

Jørn, B. P., Kroon, A., and Jakobsen, B. H., 2015. Holocene sea-level reconstruction in the Young Sound region, Northeast Greenland. Journal of Quaternary Science, 26(2): 219-226. (  0) 0) |

Liu, A., and Zhang, D., 1991. On the historical storm surges round the Bohai Sea region. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 21(2): 21-36. (  0) 0) |

Liu, L., Wang, H., Yang, Z., Fan, Y., Wu, X., Hu, L., et al., 2022. Coarsening of sediments from the Huanghe (Yellow River) delta-coast and its environmental implications. Geomorphology: 108105. (  0) 0) |

Maher, E., and Harvey, A. M., 2008. Fluvial system response to tectonically induced base-level change during the late-Quaternary: The Rio Alias Southeast Spain. Geomorphology, 100(1-2): 180-192. DOI:10.1016/j.geomorph.2007.04.038 (  0) 0) |

Murray, A. S., and Wintle, A. G., 2000. Luminescence dating of quartz using an improved single-aliquot regenerative-dose protocol. Radiation Measurements, 32: 57-73. (  0) 0) |

Peltier, W. R., 2001. Global glacial isostatic adjustment and modern instrumental records of relative sea level history. In: Sea Level Rise: History and Consequences. Douglas, B. C., et al., eds., Academic Press, San Diego, CA, 342-356.

(  0) 0) |

Peltier, W. R., and Fairbanks, R. G., 2006. Global glacial ice volume and Last Glacial Maximum duration from an extended Barbados sea level record. Quaternary Science Reviews, 25: 3322-3337. DOI:10.1016/j.quascirev.2006.04.010 (  0) 0) |

Peng, J., Ma, S., Chen, H. Q., and Li, Z. W., 2013. Temporal and spatial evolution of coastline and subaqueous geomorphology in muddy coast of the Yellow River Delta. Journal of Geographical Sciences, 23(3): 490-502. DOI:10.1007/s11442-013-1023-9 (  0) 0) |

Shang, Z. W., Chen, Y. S., Jiang, X., Wang, F., Li, J. F., Shi, P., et al., 2015. New discovery of a fishing site during western Han Dynasty and enlightenment for the 'Western Han Dynasty's Transgression' on the west coast of Bohai Bay. Geological Review, 61(6): 1468-1481. (  0) 0) |

Tran, N., Hung, D. T., and Thu, T. H., 2022. The relationship between sequence stratigraphy and groundwater of Quaternary sediments in relation to global sea-level change in the downstream Red River Delta area. Lithology and Mineral Resources, 57(5): 449-472. (  0) 0) |

Wang, F., Shang, Z. W., and Li, J. F., 2020. Research status and protection suggestions of cheniers on Bohai Bay. North China Geology, 43(4): 293-316. (  0) 0) |

Wang, H., Quan, M., and Xu, W., 2023. Sea level rise projection in China's coastal and offshore areas. Haiyang Xuebao, 45(8): 1-10. (  0) 0) |

Wang, H., Wu, X., Bi, N., Li, S., Yuan, P., and Wang, A., 2017a. Impacts of the dam-orientated water-sediment regulation scheme on the lower reaches and delta of the Yellow River (Huanghe): A review. Global Planet Change, 157: 93-113. (  0) 0) |

Wang, N., Li, G., Qiao, L., Shi, J., Dong, P., Xu, J., et al., 2017b. Long-term evolution in the location, propagation, and magnitude of the tidal shear front of the Yellow River Mouth. Continental Shelf Research, 137: 1-12. (  0) 0) |

Wang, Q., Yuan, G. B., and Zhang, S., 2007. Shelly ridge accumulation and sea-land interaction on the west coast of the Bohai Bay. Quaternary Sciences, 5: 775-786. (  0) 0) |

Wang, Q., Zhong, S. Y., Li, X. Y., Zhan, C., Wang, X., and Liu, P., 2016a. Supratidal land use change and its morphodynamic effects along the eastern coast of Laizhou Bay during the recent 50 years. Journal of Coastal Research, 74(1): 83-94. (  0) 0) |

Wang, Q., Zhou, H. Y., Cheng, K., Chi, H., Shen, C., Wang, C., et al., 2016b. The climate reconstruction in Shandong Peninsula, northern China, during the last millennium based on stalagmite laminae together with a comparison to δ18O. Climate of the Past, 12(4): 871-881. (  0) 0) |

Wang, Q., Zhou, H. Y., Cheng, K., Chi, H., Wang, H. Y., Wang, S., et al., 2015. Stalagmite records of climate and environmental changes on western Shandong Peninsula in the past 1000 years: Lamina thickness. Marine Geology & Quaternary Geology, 35(6): 133-138. (  0) 0) |

Wang, S. C., 1998. The changes of lakes on coastal plain along the Laizhou Bay in historical times. Geographical Research, 4: 88-93. (  0) 0) |

Wu, X., Bi, N., Xu, J., Nittrouer, J. A., Yang, Z., Saito, Y., et al., 2017. Stepwise morphological evolution of the active Yellow River (Huanghe) Delta lobe (1976 – 2013): Dominant roles of riverine discharge and sediment grain size. Geomorphology, 292: 115-127. (  0) 0) |

Xu, K., Bentley, S. J., Day, J. W., and Freeman, A. M., 2019. A review of sediment diversion in the Mississippi River Deltaic Plain. Estuarine Coastal and Shelf Science, 225(30): 1-15. (  0) 0) |

Xue, C., 1993. Historical changes in the Yellow River Delta, China. Marine Geology, 113(3): 321-330. (  0) 0) |

Zhan, C., Wang, Q., Cui, B., Zeng, L., Dong, C., and Li, X., 2020. The morphodynamic difference in the western and southern coasts of Laizhou Bay: Responses to the Yellow River Estuary evolution in the recent 60 years. Global Planet Change, 187(3): 103138. (  0) 0) |

Zhao, X. T., 1986. Development of cheniers in China and their reflection on the coastline shift. Scientia Geographica Sinica, 4: 293-304. (  0) 0) |

Zheng, S., Han, S. S., Tan, G. M., Xia, J. Q., Wu, B. S., Wang, K. R., et al., 2018. Morphological adjustment of the Qingshuigou Channel on the Yellow River. Catena, 166: 44-55. (  0) 0) |

Zhou, L., Liu, J., Saito, Y., Zhang, Z., Chu, H., and Hu, G., 2014. Coastal erosion as a major sediment supplier to continental shelves: Example from the abandoned Old Huanghe (Yellow River) Delta. Continental Shelf Research, 82: 43-59. (  0) 0) |

2025, Vol. 24

2025, Vol. 24