2) College of Chemical Engineering and Biological Technology, Xingtai University, Xingtai 054001, China;

3) Open Studio for Marine Corrosion and Protection, Pilot National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology (Qingdao), Qingdao 266100, China

The corrosion of metals is viewed as one of the most serious problems faced by the whole world (Yun et al., 2007; de Leon et al., 2012). Various attempts are involved in cathodic protection (Shen et al., 2005; Yun et al., 2007), protective coating (Wessling, 1994; Kilmartin et al., 2002; Antonio et al., 2010; Cui et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2018), corrosion inhibitors (Quraishi et al., 2002; Söylev et al., 2008), or any combination thereof (Kendig et al., 2003; Kumar et al., 2006; Suryanarayana et al., 2008). Protective coatings are one of the most efficient methods of achieving corrosion protection. The number of active sites, for example, can be decreased by organic inhibitors and organic coatings (Kilmartin et al., 2002). Currently, the conducting polymers have been as a potential alternative to environmentally hazardous chromium and phosphate (Beck et al., 1993; Ahmad and MacDiarmid, 1996; Camalet et al., 1998; Zalewska et al., 2000). Among conducting polymers, polyaniline (PANI) and its derivatives have attracted particular interest because of their good corrosion inhibiting properties (Wessling, 1994; Ahmad and MacDiarmid, 1996; Li et al., 1997; Tale et al., 1997; Wessling and Posdorfer, 1999; Bernard et al., 1999; Tallman et al., 2002). PANI helps the formation of a passivation layer on the metal surface and lowers the corrosion rate (DeBerry, 1985; Kinlen et al., 1999; Sazou, 2001; Fenelon and Breslin, 2003; Alvial et al., 2004; Bazzaoui et al., 2004; Martins et al., 2004; Shinde et al., 2005; Yagan et al., 2005). Moreover, different substituted polyanilines, including poly (2, 5-dimethoxy aniline) (Alvial et al., 2004), poly (o-methoxy aniline) (Kilmartin et al., 2002; Sathiyanarayanan and Balakrishnan, 1994), poly (N-ethylaniline) (Shah and Iroh, 2002), poly (2-ethoxyaniline) (Roković et al., 2007), poly (2-methoxy-aniline) (Mattoso et al., 1994), poly (N-methylaniline) (Yağan et al., 2005), poly (aniline-co-2-chloroaniline) (Hür et al., 2006), poly (aniline-co-2-anisidine) (Bereket et al., 2005a), and poly (aniline-co-2-iodoaniline) (Bereket et al., 2005b) also have been investigated to explore the best corrosion protection. More recently, it has been discovered that the hydrophobic groups can facilitate the improvement of the anticorrosion property of polyaniline derivatives (Xing et al., 2014). So, increasing hydrophobicity of conducting polymer can be accepted as a valuable means of improving the anticorrosion properties.

In this paper, poly (aniline-co-2-ethylaniline) (PANI-EA) micro/nanostructures with varied amounts of hydrophobic –C2H5 groups were prepared to further explore the effect of hydrophobic groups in polyaniline derivatives on their anticorrosion performance. The hydrophobic group, –C2H5, was introduced to the molecular chain of PANI by copolymerizing aniline (Ani) and 2-ethylaniline (EA) at different [EA]/[Ani+EA] molar ratios. The corrosion behaviors of carbon steels coated with different PANI-EA copolymer coatings were then investigated in 0.1 mol L-1 H2SO4 solution, and so was the effect of the –C2H5 in the PANI molecular chains on the wettability and corrosion protection of PANI-EA copolymer coatings.

2 Experimental Details 2.1 MaterialsAniline (Beijing Chemical Reagent Co.) has been purified by distillation under vacuum. Other reagents, such as 2-ethyl aniline (EA), phosphoric acid (H3PO4) and ammonium peroxydisulfate (APS) were procured from Beijing Chemical Reagent Co. and used as received. All the reagents were analytical grade unless otherwise stated. In all experiments, the aqueous solutions were prepared with doubly distilled water. The chemical composition (by wt. %) of the A3 carbon steel samples used in this study (10 mm×10 mm×3 mm) was: C (0.14%-0.22%), Si ≤ 0.3%, Mn (0.3%-0.65%), P ≤ 0.045%, S ≤ 0.05% with the balance of iron.

2.2 Synthesis Procedure of PANI-EA CopolymersPANI-EA copolymers were synthesized by copolymerization of Ani and EA at room temperature in aqueous solution. Briefly: Ani and EA were dispersed in deionized water (10 mL) in the ice-water bath under ultrasonication for 1 min to obtain uniform emulsion. Then 5 mL of aqueous solution containing 1 mmoL of H3PO4 was added to the above mixture. After 5 mL APS (0.4 mol L-1) aqueous solution was added, the mixture was continuously stirred for 12 h in the ice bath. The precipitated powder was collected by filtration and washed with H2O, ethanol and ether respectively. Finally, products were dried under vacuum at ambient temperature. Five different molar ratios of [EA] to [Ani+EA] represented by [EA]/[Ani+EA] ratio of 0:1, 0.1:1, 0.5:1, 0.9:1, 1:1 were selected to prepare PANI-EA copolymers with different wettability.

2.3 CharacterizationThe morphologies of the resulting PANI-EA copolymers were measured by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, JSM-6700F). FT-IR and UV-Vis spectroscopy were carried out to study the molecular structures. FT-IR spectroscopy in the range 400-4000 cm-1 of the PANI-EA copolymers sample pellets made with KBr were carried out using an IFS-113V instrument. The resolution of measurements and the number of scans were 4 cm-1 and 16, respectively. UV-Vis spectra of the PANI-EA copolymer in m-cresol were investigated by a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Hitachi UV-3100). The crystal structures of the resulting copolymers were characterized by X-ray diffraction (Micscience Model M18XHF diffractometer). The water contact angles (CAs) were measured on a Mettler Toledo CAM101 system at room temperature. The static water contact angle was measured 5 times at different sites and the mean value was chosen to present the result. The porosities of PANI-EA coatings were tested using the weighing methods (Chen et al., 2015). The conductivity at room temperature was measured using four-probe method with a KEITHLEY 2400 multimeter and a KEITHLEY 2182A nanovoltmeter.

2.4 Preparation of PANI-EA Coated Carbon SteelThe electrochemical impedance and potentiodynamic measurements were carried out on carbon steel electrodes which were spot welded to the copper wire of 15 cm and encapsulated with epoxy resin. The encapsulated carbon steel electrode was polished by using 1000 and 5000-grit emery papers. Prior to the copolymer film coating process, all the carbon steel electrodes were ultrasonically treated in acetone and ethanol to degrease. PANI-EA copolymer coatings were deposited onto carbon steel electrodes by drop-casting technique: PANI-EA powders were dispersed in n-butyl alcohol in an ultrasonic bath for 5 min. Then, the dispersion was spread over the polished electrodes and dried at ambient temperature to obtain thin coatings. The thickness of the coatings was in the range 20-22 μm.

2.5 Electrochemical MeasurementsCorrosion tests were performed on an AUTOLAB PGSTAT302N. The electrochemical measurements were conducted by using a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference electrode, a Pt sheet (20 mm×20 mm) as the counter electrode and carbon steel as the working electrode in a three-electrode cell. The area of the working electrode was 1 cm2. All electrochemical tests were performed in 0.1 mol L-1 H2SO4 aqueous solutions. The corrosion performance of the PANI-EA copolymers was examined by Tafel polarization and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. The Tafel polarization measurements were carried out by changing linearly the potential automatically from (-250 mVSCE to + 250 mVSCE) versus open circuit potential at a scan rate of 1 mV s-1. Electrochemical impedance measurements were performed in the frequency range of 105 to 10-2 Hz with AC signals of 10 mV amplitude at the constant open circuit potential (OCP).

The protection efficiency (η%) could be evaluated from the following equation:

| $ \eta(\%)=\frac{i_{\text {corr }}-i_{\text {corr }}(\mathrm{C})}{i_{\text {corr }}} \times 100, $ |

where icorr and icorr(C) is the corrosion current density of uncoated and coated specimens, respectively.

The samples were immersed for 30 min before the EIS measurements to make sure that the system is in steady-state. All electrochemical measurements were performed in triplicate at ambient temperature.

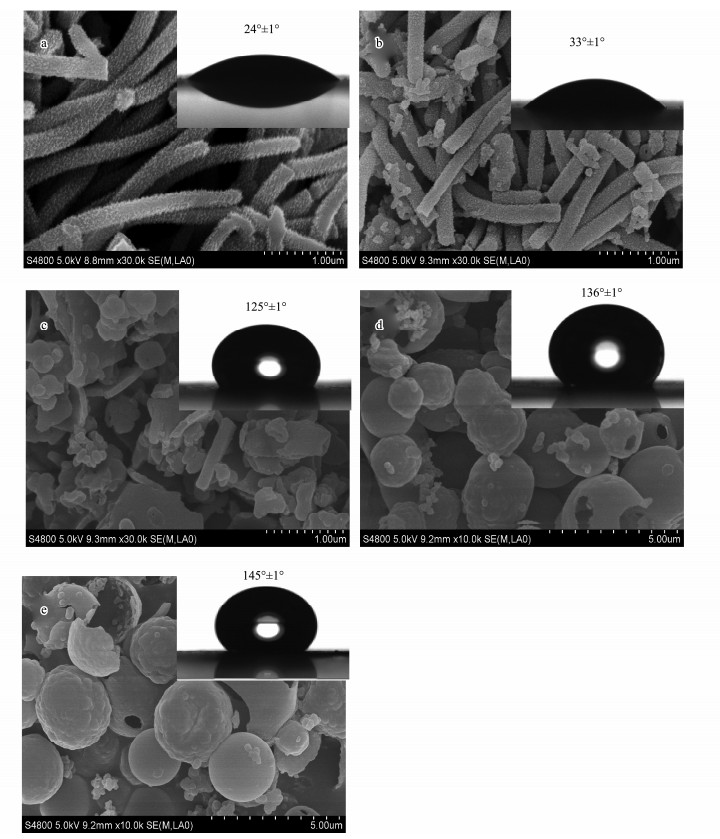

3 Results and Discussion 3.1 The Morphology and Wettability of PANI-EA Copolymer CoatingsThe morphologies of the PANI-EA copolymer products were significantly affected by the molar ratio of [EA] to [Ani+EA] (represented by [EA]/[Ani+EA]). Representative SEM images of the PANI-EA copolymer as-prepared at different [EA]/[Ani+EA] are presented in Fig. 1. It can be clearly seen from Fig. 1a that the PANI presents relatively uniform fibers whose average diameter increases from 110 nm to several micrometers. Fig. 1b indicates that PANI-EA-1 ([EA]/[Ani+EA]=0.1) nanofibers bear similarity to the PANI fibers, but smaller nanoparticles are observed on the surface of the PANI-EA-1 copolymer fibers. And the PANI-EA-1 nanofibers are not as uniform as PANI fibers. When the copolymer was prepared at [EA]/[Ani+EA]=0.5, the product (PANI-EA-2) was made up of accumulated flakes, blocks and granular particles, as shown in Fig. 1c. The PANI-EA-3 ([EA]/[Ani+EA]= 0.9) copolymer and poly(2-ethyl aniline) (PEA) mainly consist of hollow spheres with diameter of 10-30 μm. From the broken hollow spheres, the shell thickness can be estimated to be about 100 nm (Figs. 1d-e).

|

Fig. 1 SEM images of the copolymer synthesized at different [EA]/[Ani+EA] molar ratios. (a), PANI; (b), PANI-EA-1; (c), PANI-EA-2; (d), PANI-EA-3 and (e), PEA. |

The surface wettability of PANI-EA copolymer products was characterized by water CA measurements, as demonstrated in the insets of Fig. 1. The surface of PANI micro/nanostructures is strongly hydrophilic, with a water CA as low as 24° (Fig. 1a). PANI-EA-1 copolymer's water CA of 33° is higher than PANI, exhibiting a hydrophilic character (Fig. 1b). The water CA of the PANI-EA-2 and PANI-EA-3, increased to 125° and 136°, the characteristics of a hydrophobic film, respectively. The –C2H5 groups and relatively rough surface contribute to the hydrophobic properties of the PANI-EA copolymer micro/nanostructures to some extent. For example, PEA has the most –C2H5 groups and shows the highest CA (145°), as shown in Fig. 1e. It is evident that the water CA of the PANI-EA increases with the increase of [EA]/ [Ani+EA] molar ratio. The surface wettability of the coating is governed by both the chemical composition and the surface roughness (Zhu et al., 2006). In Cassie state, the CA of a water droplet on a hydrophobic surface (θr) is associated with the CA (θ) on a smooth surface by the Cassie-Baxter equation (Cassie and Baxter, 1944):

| $ \cos \theta_{r}=f_{1} \cos \theta-f_{2}, $ |

where f1 and f2 is the fractions of solid surface and air in contact with water, respectively (i.e., f1 + f2 = 1). According to the Cassie-Baxter model hypothesis, a droplet of water is suspended on the rough surface, allows air trapping between the rough structures on a surface and thus reduces the water contact with the coatings. For the PANI and PANI-EA-1 copolymer, the low water CA can be attributed to hydrophilic the PANI molecular structure. The increased CA of PANI-EA-2, PANI-EA-3 and PEA may be caused by the increased hydrophobic –C2H5 group on the PANI molecular structure. Besides, the surface roughness becomes larger and larger. For PEA, PEA is most hydrophobic and has the largest water CA. The reasons for the most hydrophobic properties of the PEA are as follows: PEA holds much hydrophobic –C2H5 group on the PANI backbone, confirmed by the FTIR spectra (Fig. 2A), which make PEA have low surface energy. Especially, the microballoon sphere structure can trap more air between the micro-spheres, proved by SEM images.

|

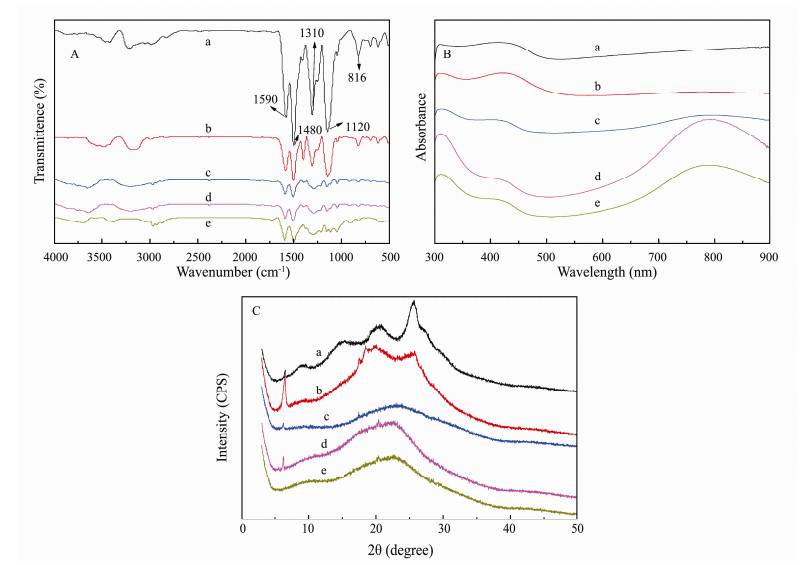

Fig. 2 FTIR (A), UV-Vis absorption spectra (B) and X-ray diffraction patterns (C) of the copolymer synthesized with different [EA]/[Ani+EA] ratios (a), PANI; (b), PANI-EA-1; (c) PANI-EA-2, (d) PANI-EA-3 and (e) PEA. |

It has been established that for a coating to be effective in preventing corrosion of the underlying substrate, it has to be able to prevent the diffusion of water through it. Absorption of water by the coating can form a diffusion pathway for H+. Continuous supply of H+ ensures the cathodic reaction proceeds. It can be reasonably assumed that coatings with water repellant property can be expected to contribute to the prevention of diffusion of water through it and subsequently decrease the corrosion rate of the underlying substrate. To quantitatively measure the corrosion protection efficiency of the coatings, a potentiodynamic polarization and the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) experiments were conducted.

3.2 Structural Characterization of the PANI-EA CopolymersFourier-transform infrared (FTIR) and UV-Visible (UV-Vis) spectrometry were used for investigating the molecular structure of the PANI-EA copolymer micro/nanostructures prepared at different [EA]/[Ani+EA] molar ratios. Firstly, FTIR spectra of the PANI-EA copolymer micro/nanostructures were similar to each other, as shown in Fig. 2A. The peaks at about 1590 cm-1 are due to the C=C double bond of the quinoid rings, whereas the peak at about 1500 cm-1 arises from the vibration of the C=C of the benzenoid ring (Macdiarmid et al., 1985), revealing that the backbone structures of PANI-EA copolymer are composed of amine and imine units. The bands at about 1310 cm-1 and 1120 cm-1 correspond to C-N and C=N stretching vibrations (Zhang and Wan, 2002; Zhu et al., 2009), respectively. The band at 816 cm-1 assigned to the vibration of symmetrically-substituted benzene was also observed in PANI-EA copolymer micro/nanostructures (Tang et al., 1988). Similar peaks are observed for PANI-HCl (Macdiarmid et al., 1985). Thus, it is indicated that the main molecular chain of the PANI-EA copolymers obtained in this study is consistent with PANI doped with HCl. Besides, it is suggested that two bands at 2962 cm-1, 2920 cm-1 and 2877 cm-1 are associated with the asymmetric stretching vibration of methyl group, the asymmetric stretching vibration of methylene group and the symmetric stretching vibration of methyl group (Athawale et al., 1999) can be observed (Fig. 2B-e). It is revealed by the existence of these –CH2CH3 characteristic peaks that 2-ethyl aniline was copolymerized with aniline successfully. On top of that, the intensity of C-H stretching vibration absorption peak increases with the increase of the [EA]/[Ani+EA] molar ratio, indicating that more hydrophobic –CH2CH3 groups were incorporated into the polyaniline chain as the [EA]/[Ani+EA] molar ratio continued to rise.

As shown in Fig. 2B, three peaks centered at about 310 nm, 430 nm and 800 nm are shown by UV-Vis absorbance spectra of the PANI-EA copolymer micro/nano-structures, similar to those of the emeraldine salt form of PANI (Cao et al., 1989). The band at about 310 nm is caused by the overlap of the π-π* transitions of the benzoid rings and the azobenzene moiety of PANI (MacDiarmid and Epstein, 1994). The absorption peak about 430 nm is readily attributed to the partial oxidation of PANI and represents theintermediate state between the emeraldine form containing conjugated quinoid rings and the leucoemeraldine form containing benzenoid rings in the backbone structure of the PANI-EA copolymer. A wide band at around 800 nm is assigned to the polaron band, which typically characterizes protonation. It is worth mentioning that the intensity of band around 800 nm increased with the increase of [EA]/[Ani+EA] molar ratios, suggesting that the intensity of polaron band increased in step with the rising number of –C2H5 groups in the main copolymer chain.

It was found that crystallinity of the copolymer determined by X-ray diffraction measurements (XRD) was influenced, to a large extent, by the –C2H5 groups in the main chain, as shown in Fig. 2C. XRD of PANI has three characteristic peaks centered at 2θ = 15°, 21°and 25°, especially a peak located at 2θ= 9.3°assigned to the scattering along the orientation parallel to the PANI chain (Fig. 2C-a). Two characteristic peaks around 2θ = 20° and 26°, due to the periodicity parallel and perpendicular to the backbone structure of PANI (Sai Ram and Palaniappan, 2004), are observed for PANI-EA-1 (Fig. 2C-b). As shown in Fig. 2C-c, d, e, a broad featureless XRD pattern centered at 2θ = 18°-25° is observed for the PANI-EA-2, PANI-EA-3 and PEA copolymer micro/nanostructures, indicating that the crystallinity of PANI polymer is higher than most of the PANI-EA copolymer micro/nano-structures which are amorphous. In particular, the peak at 2θ = 6.5° for the PANI-EA copolymers is attributed to the regular spacing between the dopant and N atom on main chains, suggesting that there is a short range order between the polymer chain and the counter anion in the PANI-EA copolymer micro/nanostructures. It is confirmed in the XRD that the crystallinity of PANI-EA copolymer was varied, depending on the ANI/EA molar ratios.

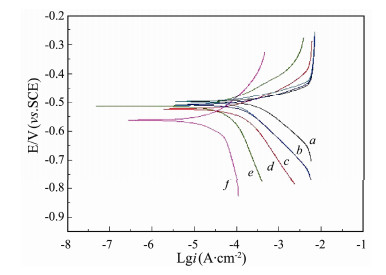

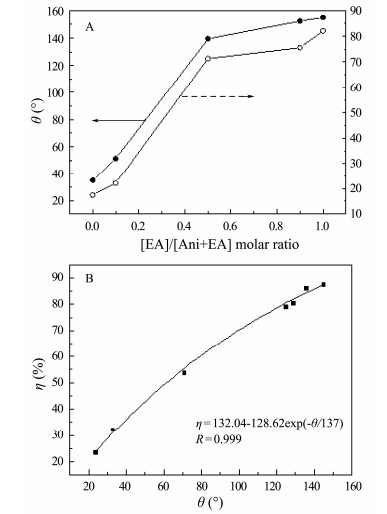

3.3 DC Polarization and EISThe corrosion performance of uncoated and coated carbon steel with PANI-EA copolymer micro/nanostructures was investigated in corrosive medium (0.1 mol L-1 H2SO4 solution). Anticorrosion capability of the copolymer can be analyzed by corrosion current density (icorr), corrosion potential (Ecorr), protection efficiency (η) and polarization resistance (Rp). These parameters are extracted from the Tafel polarization curves and listed in Table 1. It is mentioned that the corrosion potential of carbon steel coated by PANI-PEA copolymers shifts negatively in this work. Similar results have been reported before (Pug et al., 1999; Yağanet et al., 2006). However, the Ecorr of carbon steel coated with PANI presents a positive shift compared to the bare electrode in some papers (Hür et al., 2006; Wang and Tan, 2006; Fang et al., 2007). These differences will be discussed in the following part. The Rp of carbon steel coated with the copolymer increases in the following order: PANI < PANI-EA-1 < PANI-EA-2 < PANI-EA-3 < PEA. Compared to the uncoated carbon steel (42.33 Ω·cm-2), the Rp for PANI and PANI-EA-1 increased to 100.3 and 105.2 Ω cm-2, respectively. Hence, higher –C2H5 content in the copolymer improved carbon steel protection in H2SO4. This was further evidenced by the Rp of PANI-EA-2 and PANI-EA-3. Compared with PANI-EA-2, the Rp of PANI-EA-3 increased from 297.6 to 473.2 Ω cm-2, indicating PANI-EA-3 offered more effective protection to carbon steel in H2SO4 than PANI-EA-2 coatings. The same trend was also seen when comparing the Rp of the PANI-EA-3 and PEA (1068 Ω cm-2). These results conclusively demonstrated that the [EA]/[Ani+EA] molar ratio had strong influence on the anticorrosion performance of PANI-EA copolymer coatings. The polarization curves reveal that corrosion current density (icorr) of electrode coated with PANI-EA copolymers is decreased compared with the bare electrode, as shown in Fig. 3. It can be concluded in the result that carbon steel can be protected by the PANI-EA copolymer micro/nanostructures. Especially, the corrosion current density decreases in the following order of PANI > PANI-EA-1 > PANI-EA-2 > PANI-EA-3 > PEA, as the content of –C2H5 groups on the copolymer chain increases. The corrosion current density (icorr) for bare electrode was identified as 0.235 mA cm-2 and the corrosion current density (icorr) of PANI (0.180 mA cm-2), PANI-EA-1 (0.160 mA cm-2), PANI-EA-2 (0.0439 mA cm-2), PANI-EA-3 (0.0374 mA cm-2) and PEA (0.0299 mA cm-2) decreased by 23.32%, 32.00%, 78.98%, 85.93% and 87.29% (Table 1), respectively. It is apparent that the efficiency of protection can be significantly enhanced by increasing the [EA]/[Ani+EA] molar ratio (Fig. 4A). On the other hand, it is proved by FTIR results (Fig. 2A) that the content of hydrophobic –C2H5 groups in PANI-EA copolymers increases in step with the rise of the [EA]/[Ani+EA] molar ratio. According to the above results, it can be inferred that the –C2H5 group on the PANI-EA copolymer chain is preferable to inhibit the carbon steel from corrosion, and more efficient protection can be produced by the more –C2H5 group on the PANI-EA copolymer chain. The–C2H5 groups' effect on the anticorrosion may be attributed to the lower wettability of PANI copolymer coatings with more hydrophobic–C2H5 groups. For example, the water contact angle of PANI-EA-1 prepared at [EA]/[Ani+EA] of 0.1 increased to 33°, compared with the water contact angles of PANI (CA= 24°). Correspondingly, the protection efficiency shifted considerably from 23.32% to 32.00%. The water CAs of PANI-EA-2 and PANI-EA-3 are 125° and 136°, respectively. Correspondingly, the corrosion current density of PANI-EA-2 and PANI-EA-3 are 0.0494 mA cm2 and 0.0374 mA cm2, respectively, which is equivalent to protection efficiency of 78.98% and 85.93%. The PEA, with the largest contact angles of 145°, offered the best protection efficiency of 87.29% to the carbon steel in 0.1 M H2SO4. It is suggested that a well-fitting correlation between the protection efficiency (η) of the PANI-EA copolymer and their water contact angle theta (θ) can be observed as follows:

| $ \eta=132.04-128.62 \exp (-\theta / 137). $ | (2) |

|

|

Table 1 Tafel polarization curves parameters and water absorption rate for bare carbon steel and carbon steel coated by different PANI-EA copolymers in 0.1 mol L-1 H2SO4 |

|

Fig. 3 Tafel curves plot of carbon steel coated by the copolymer synthesized at different [EA]/[Ani+EA] ratios in 0.1 mol L-1 H2SO4. (a), blank; (b), PANI; (c), PANI-EA-1; (d), PANI-EA-2; (e) PANI-EA-3 and (f) PEA. |

|

Fig. 4 The effect of [EA]/[Ani+EA] molar ratios on the contact angle (θ) and the corrosion efficiency (η) of the PANI-EA copolymer micro/nanostructures coatings (A) and the effect of θ of the PANI-EA copolymer micro/ nanostructures coatings on η of the PANI-EA copolymer micro/nanostructures coatings (B). |

To confirm the applicability of the formula, [EA]/ [Ani+EA] ratio of 0.3:1 and 0.7:1 are chosen to prepare PANI-EA copolymers coatings to protect carbon steel. It is found out that the contact angle of PANI-EA (0.3:1) coatings is 71°, and its corrosion protection efficiency is 53.49%. For PANI-EA (0.7:1), the contact angle is 129° and η is 80.37%, which are in correspondence with the theoretical 55.44% and 81.88% calculated using Equation (2).

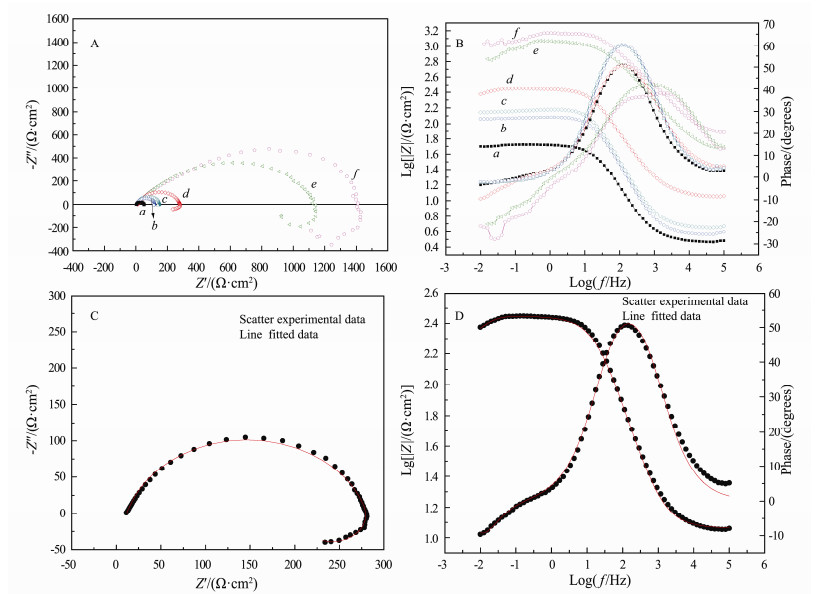

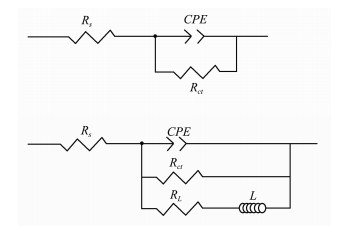

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was employed to understand the anticorrosion performance of PANI-EA copolymer micro/nanostructures. The Nyquist and corresponding Bode plots of log Z-log frequency and phase angle-log frequency are shown in panels A and B in Fig. 5, respectively. To determine the impedance parameters of the carbon steel coated with PANI-EA copolymer, the measured impedance data were analyzed by Nova1.8 impedance analysis software (AUTOLAB PGSTAT302N). Equivalent circuit for these samples is illustrated in Fig. 6 and the impedance parameters are presented in Table 2. The Nyquist and Bode plots for the electrode coated with PANI-EA-2 in 0.1 mol L-1 H2SO4 are presented in Figs. 5C and D, respectively. A good agreement was obtained between the experimental and simulated data. In the equivalent circuit model: Rs and Rct refer to the solution resistance and the charge transfer resistance, respectively. Constant phase element (CPE) has a non-integer power dependence on the frequency, and is required for modeling the frequency dispersion behavior corresponding to different physical phenomena like surface heterogeneity resulting from surface roughness, dislocations, impurities, distribution of the active sites, formation of porous layers and inhibitors adsorption (Noor, 2009).

|

Fig. 5 Nyquist (A) and Bode (B) plot of carbon steel coated by the copolymer synthesized at different [EA]/[Ani+EA] ratios in 0.1 mol L-1 H2SO4. (a), blank; (b), PANI; (c), PANI-EA-1; (d), PANI-EA-2; (e), PANI-EA-3 and (f) PEA. Nyquisit (C) and Bode (D) plots for carbon steel coated by PANI-EA-2 copolymer in 0.1 mol L-1 H2SO4. Plots, experimental data; lines, fitting data. |

|

Fig. 6 Equivalent electric circuits used to simulate the EIS results for (a), bare carbon steel, PANI and PANI-EA-1; (b), PANI-EA-2, PANI-EA-3 and PEA. |

|

|

Table 2 Circuit parameters for bare carbon steel and carbon steel coated by different PANI-EA copolymers in 0.1 M H2SO4 |

As observed in Fig. 5A a-c, the impedance spectrum of the PANI and PANI-EA-1 presents a capacitive-like, semi elliptical (depressed semicircle) with its diameter along the real axis, which is similar to the bare electrode. The Nyquist plots of PANI-EA-2 and PANI-EA-3 coated carbon steel reveal that both of impedance diagrams consist of a large depressed semicircle at high frequency (HF) region and an inductive loop (LP) in the low frequency region, which is a time-dependent process related with the immersion time.

It is evident that marked changes take place in terms of the capacitive-like semicircle diameter of the electrode coated with PANI-EA copolymers compared to that of the bare electrode. Their diameters, associated with the polarization resistance, increased in the following order of PANI < PANI-EA-1 < PANI-EA-2 < PANI-EA-3 < PEA, indicating that the charge transfer resistance (Rct) increases in the order of PANI < PANI-EA-1 < PANI-EA-2 < PANI-EA-3 < PEA. It is believed that the corrosion rate decreases (Peng et al., 2013) as the semicircle diameter (Rct) becomes larger; therefore, most effective protection was offered by the PEA to the carbon steel in 0.1 mol L-1 H2SO4. The increase of Rct might be assigned to different causes, e.g., the formation of a surface oxide induced by PANI-EA copolymers and PEA, the rise of the hydrophobic property of the PANI-EA copolymer, the decreased conductivity of PANI-EA copolymers and PEA or decrease of the porosity. Among them, the possibility of a surface oxide formation can be ruled out because Ecorr has a negative shift (Fig. 3). So it is reasonable that the increase of Rct might be related to the high hydrophobicity and the decreased conductivity (Table 1) of the PANI-EA copolymer and PEA coatings. In the corresponding Bode plots of logZ-log frequency curves (Fig. 5B), it can be seen that logZ in low frequencies region presents a similar tendency to semicircle diameters. These results obtained with electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) experiments are fully in correspondence with those of the potentiodynamic polarization results. The result of the electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) experiments and potentiodynamic polarization indicated that the PEA micro/nanostructures coating showed better anticorrosion performance than other PANI-EA copolymers. The anticorrosion performance of PEA is also superior to that of other previously reported conducting polymer coatings (Pud et al., 1999; Yağan et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2010; Xing et al., 2014). It can be concluded that corrosion resistance of a coating can be increased with the rise of the hydrophobic property.

It has generally been assumed that conducting polymers protect the metals by not only behaving as a barrier but also acting as an effective oxidizer to maintain the metal in the passive state. This mechanism deals with the good electronic conductivity of conducting polymers and redox chemistry (Ahmad et al., 1996; Bernard et al., 1999). Or they serve as an active coating involved in the reaction taking place between the electrolyte and the metal (Moraes et al., 2004; Lu et al., 1995). It is worth noting that the anodic current of electrode coated by PANI-EA copolymer decreased compared to the bare carbon steel, but the corrosion potential (Ecorr) of PANI-EA coated carbon steel electrodes shifts slightly to negative values compared with that of uncoated carbon steel electrode in our work, which is consistent with the previous reports on PANI (Sazou and Georgolios, 1997) and ring-substituted PANI (Sazou, 2001; Yağan et al., 2007). This negative shift of corrosion potential suggests that there was no passivation layer on the metal surface (Pud et al., 1999; Hür et al., 2006; Wang and Tan, 2006; Xing et al., 2014), and also means that there is lack of significant barrier property of the PANI-EA copolymer coatings for the direct contact of the substrate and solution. This negative shift of the corrosion potential seems to be unconducive to the anticorrosion protection of carbon steel. Then, what role did PANI-EA copolymer coatings play in anticorrosion protection?

In acidic solutions, the anodic reaction is the oxidation of the metals to ferrous irons, the process of which is driven by the hydrogen evolution. H3O+ diffuses towards the PANI-EA copolymer coating, or further to the surface of the carbon steel. When H+ receives an electron to generate an H atom, H2 can be formed. In consideration of the conductivity of PANI-EA copolymer micro/nanostructures, H2 can be released from the electrode surface or the PANI-EA copolymers surface. The anodic and cathodic events occurring in the metal/copolymer/solution interface are proposed to be:

The anodic corrosion process:

| $ \mathrm{Fe} \rightarrow \mathrm{Fe}^{2+}+2 \mathrm{e}^{-}. $ | (3) |

The cathodic process:

| $ \mathrm{H}_{3} \mathrm{O}^{+} \rightarrow \mathrm{H}^{+}+\mathrm{H}_{2} \mathrm{O}, $ | (4) |

| $ 2 \mathrm{H}^{+}+2 e \rightarrow \mathrm{H}_{2}, $ | (5) |

| $ \mathrm{H}^{+}+\mathrm{P} \mathrm{ANI}(\mathrm{e}) \rightarrow \mathrm{PANIH}, $ | (6) |

| $ \mathrm{PANIH}+\mathrm{PANIH} \rightarrow \mathrm{H}_{2}+2 \mathrm{PANI}, $ | (7) |

| $ \mathrm{PANIH}+\mathrm{H}^{+}+\mathrm{PANI}(\mathrm{e}) \rightarrow \mathrm{H}_{2}+2 \mathrm{PANI}. $ | (8) |

It has been established that the water can form a diffusion pathway for H+ (Zhang et al., 2011). For a coating which can effectively prevent corrosion of the underlying substrate, it is required to prevent the diffusion of water through it (Weng et al., 2011). Therefore, it can be reasonably assumed that increasing the water repellant property of the coating increases its ability to protect the underlying substrate from corroding (de Leon et al., 2012). In this work, the H2O repellant performance may be decided by two main factors: hydrophobicity and porosity of the PANI-EA coatings. Which one is the decisive factor? The hydrophobicity follows the order of PEA > PANI-EA-3 > PANI-EA-2 > PANI-EA-1 > PANI. This change tendency is same as that of protection efficiency when increasing the [EA]/[ANI+EA] molar ratio. On the other hand, it has been reported that nano/micro pores existed in the coatings may increase the possibility of the electrolyte penetration through the coating via connected sub-channels (Yu and Tian, 2014). So how about the effect of the porosity on the protection for carbon steel? As shown in Table 1, the porosity of PANI-EA has an order of PEA > PANI-EA-3 > PANI-EA-2 > PANI-EA-1 > PANI, which is also in agreement with that of protection efficiency. Besides, the decreased conductivity of PANI-EA copolymers and the PEA also contributes to the good protection, which has been then confirmed by Rct in Nyquist plots.

4 ConclusionsPANI-EA copolymers with varied wettability were prepared by copolymerization of aniline (Ani) and 2-ethy-laniline (EA) at different EA/(Ani+EA) molar ratios via the chemical polymerization method. It is indicated in Tafel polarization curve and EIS that the PANI-EA copolymer micro/nanostructures coatings exhibit effective anticorroison property to the carbon steel electrode. The protective capability of PANI-EA copolymers increased as the hydrophobic property of PANI-EA copolymers rose, and a well-fitted relationship between inhibition efficiency and the water contact angle of PANI-EA copolymers coatings was shown as η = 132.04 – 128.62 exp (-θ/ 137). The PEA micro/nanostructures coating showed best anticorrosion performance with corrosion protection efficiency of 87.29%. The superior anticorrosion performance of PEA could be attributed to its most hydrophobic property (CA=145°), lowest conductivity and lowest porosity.

AcknowledgementsThe authors appreciate the financial supports of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41476059) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (No. E2018108011).

Ahmad, N. and MacDiarmid, A. G., 1996. Inhibition of corrosion of steels with the exploitation of conducting polymers. Synthetic Metals, 78(2): 103-110. DOI:10.1016/0379-6779(96)80109-3 (  0) 0) |

Alvial, G., Matencio, T., Neves, B. R. A. and Silva, G. G., 2004. Blends of poly (2, 5-dimethoxy aniline) and fluoropolymers as protective coatings. Electrochimica Acta, 49: 3507-3516. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2004.03.021 (  0) 0) |

Antonio, F. F., Roderick, B. P. and Rigoberto, C. A., 2010. A conjugated polymer network approach to anticorrosion coatings: Poly(vinylcarbazole) electrodeposition. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 49: 9789-9797. (  0) 0) |

Athawale, A. A., Deore, B., Vedpathak, M. and Kulkarni, S. K., 1999. Photoemission and conductivity measurement of poly (N-methyl aniline) and poly (N-ethyl aniline) films. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 74: 1286-1292. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(19991031)74:5<1286::AID-APP26>3.0.CO;2-I (  0) 0) |

Bazzaoui, M., Martins, J. I., Bazzaoui, E. A., Reis, T. C. and Martins, L., 2004. Pyrrole electropolymerization on copper and brass in a single-step process from aqueous solution. Journal of Applied Electrochemistry, 34: 815-822. DOI:10.1023/B:JACH.0000035610.10869.43 (  0) 0) |

Beck, F., Barsch, U. and Michaelis, R., 1993. Corrosion of conducting polymers in aqueous media. Journal of Electro-analytical Chemistry, 351: 169-184. DOI:10.1016/0022-0728(93)80232-7 (  0) 0) |

Bereket, G., Hür, E. and Şahin, Y., 2005. Electrochemical synthesis and anti-corrosive properties of polyaniline, poly (2-anisidine), and poly (aniline-co-2-anisidine) films on stainless steel. Progress in Organic Coatings, 54: 63-72. DOI:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2005.06.002 (  0) 0) |

Bereket, G., Hür, E. and Şahin, Y., 2005. Electrodeposition of polyaniline, poly (2-iodoaniline), and poly (aniline-co-2-iodoaniline) on steel surfaces and corrosion protection of steel. Applied Surface Science, 252: 1233-1244. DOI:10.1016/j.apsusc.2005.02.087 (  0) 0) |

Bernard, M. C., LeGoff, A. H. and Joiret, S., 1999. Polyaniline layer for iron protection in sulfate medium. Synthetic Metals, 102: 1383-1384. DOI:10.1016/S0379-6779(98)01001-7 (  0) 0) |

Camalet, J. L., Lacroix, J. C., Aeiyach, S., Chane-Ching, K. and Lacaze, P. C., 1998. Electrosynthesis of adherent polyaniline films on iron and mild steel in aqueous oxalic acid medium. Synthetic Metals, 93(2): 133-142. DOI:10.1016/S0379-6779(97)04099-X (  0) 0) |

Cao, Y., Smith, P. and Heeger, A. J., 1989. Spectroscopic studies of polyaniline in solution and in spin-cast films. Synthetic Metals, 32: 263-281. DOI:10.1016/0379-6779(89)90770-4 (  0) 0) |

Cassie, A. B. D. and Baxter, S., 1944. Wettability of porous surfaces. Transactions of the Faraday Society, 40: 546-561. DOI:10.1039/tf9444000546 (  0) 0) |

Chen, H. F., Wang, F. Q. and Han, Y. X., 2015. Gas measurement method and weighing method to measure the core porosity research and comparative analysis. Journal of Engineering, 5(3): 20-26. (  0) 0) |

Cui, X. K., Zhu, G. Y., Pan, Y. F., Shao, Q., Zhao, C., Dong, M. Y., Zhang, Y. and Guo, Z. H., 2018. Polydimethyl-siloxane-titania nanocomposite coating: Fabrication and corrosion resistance. Polymer, 138: 203-210. DOI:10.1016/j.polymer.2018.01.063 (  0) 0) |

DeBerry, D. W., 1985. Modification of the electrochemical and corrosion behavior of stainless steels with an electroactive coating. Journal of the Electrochemical Society, 132: 1022-1026. DOI:10.1149/1.2114008 (  0) 0) |

de Leon, A. C., Pernites, R. B. and Advincula, R. C., 2012. Superhydrophobic colloidally textured polythiophene film as superior anticorrosion coating. ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, 4: 3169-3176. DOI:10.1021/am300513e (  0) 0) |

Fang, J. J., Xu, K., Zhu, L. H., Zhou, Z. X. and Tang, H. Q., 2007. A study on mechanism of corrosion protection of poly-aniline coating and its failure. Corrosion Science, 49: 4232-4242. DOI:10.1016/j.corsci.2007.05.017 (  0) 0) |

Fenelon, A. M. and Carmel, B. B., 2003. The electropolymerization of pyrrole at a CuNi electrode: Corrosion protection properties. Corrosion Science, 45(12): 2837-2850. DOI:10.1016/S0010-938X(03)00104-5 (  0) 0) |

Hür, E., Bereket, G. and Şahin, Y., 2006. Corrosion inhibition of stainless steel by polyaniline, poly (2-chloroaniline), and poly(aniline-co-2-chloroaniline) in HCl. Progress in Organic Coatings, 57(2): 149-158. DOI:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2006.08.004 (  0) 0) |

Kendig, M., Hon, M. and Warren, L., 2003. 'Smart' corrosion inhibiting coatings. Progress in Organic Coatings, 47(3-4): 183-189. DOI:10.1016/S0300-9440(03)00137-1 (  0) 0) |

Kilmartin, P. A., Trier, L. and Wright, G. A., 2002. Corrosion inhibition of polyaniline and poly (o-methoxyaniline) on stainless steels. Synthetic Metals, 131(1-3): 99-109. DOI:10.1016/S0379-6779(02)00178-9 (  0) 0) |

Kinlen, P. J., Menon, V. and Ding, Y. W., 1999. A mechanistic investigation of polyaniline corrosion protection using the scanning reference electrode technique. Journal of the Electrochemical Society, 146(10): 3690-3695. DOI:10.1149/1.1392535 (  0) 0) |

Kumar, A., Stephenson, L. D. and Murray, J. N., 2006. Self-healing coatings for steel. Progress in Organic Coatings, 55(3): 244-253. DOI:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2005.11.010 (  0) 0) |

Li, P., Tan, T. C. and Lee, J. Y., 1997. Corrosion protection of mild steel by electroactive polyaniline coatings. Synthetic Metals, 88(3): 237-242. DOI:10.1016/S0379-6779(97)03860-5 (  0) 0) |

Lu, W. K., Elsenbaumer, R. L. and Wessling, B., 1995. Corrosion protection of mild steel by coatings containing polyaniline. Synthetic Metals, 71(1-3): 2163-2166. DOI:10.1016/0379-6779(94)03204-J (  0) 0) |

MacDiarmid, A. G., Chiang, J. C., Halpern, M., Huang, W. S., Mu, S. L., Nanaxakkara, L. D., Wu, S. W. and Yaniger, S., 1985. 'Polyaniline': Interconversion of metallic and insulating forms. Molecular Crystals and Liquid Crystals, 121(1-4): 173-180. DOI:10.1080/00268948508074857 (  0) 0) |

MacDiarmid, A. G. and Epstein, A. J., 1994. The concept of secondary doping as applied to polyaniline. Synthetic Metals, 65: 103-116. DOI:10.1016/0379-6779(94)90171-6 (  0) 0) |

Martins, J. I., Reis, T. C., Bazzaoui, M., Bazzaoui, E. A. and Martins, L., 2004. Polypyrrole coatings as a treatment for zinc-coated steel surfaces against corrosion. Corrosion Science, 46(10): 2361-2381. DOI:10.1016/j.corsci.2004.02.006 (  0) 0) |

Mattoso, L. H. C., Faria, R. M., Bulhoes, L. O. S. and Macdiarmid, A. G., 1994. Synthesis, doping, and processing of high molecular weight poly (O-methoxyaniline). Journal of Polymer Science: Part A: Polymer Chemistry, 32: 2147-2153. DOI:10.1002/pola.1994.080321117 (  0) 0) |

Moraes, S. R., Vilca, D. H. and Motheo, A. J., 2004. Charac-teristics of polyaniline synthesized in phosphate buffer solution. European Polymer Journal, 40(9): 2033-2041. DOI:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2004.05.016 (  0) 0) |

Noor, E. A., 2009. Evaluation of inhibitive action of some quaternary N-heterocyclic compounds on the corrosion of Al-Cu alloy in hydrochloric acid. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 114(2-3): 533-541. DOI:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2008.09.065 (  0) 0) |

Peng, C. W, Chang, K. C., Weng, C. J., Lai, M. C., Hsu, C. H., Hsu, S. C., Hsu, Y. Y., Hung, W. I., Wei, Y. and Yeh, J. M., 2013. Nano-casting technique to prepare polyaniline surface with biomimetic superhydrophobic structures for anticorrosion application. Electrochimica Acta, 95: 192-199. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2013.02.016 (  0) 0) |

Pud, A. A., Shapoval, G. S., Kamarchik, P., Ogurtsov, N. A., Gromovay, V. F., Myronyuk, I. E. and Kontsur, Y. V., 1999. Electrochemical behavior of mild steel coated by polyaniline doped with organic sulfonic acids. Synthetic Metals, 107: 111-115. DOI:10.1016/S0379-6779(99)00155-1 (  0) 0) |

Quraishi, M. A. and Rawat, J., 2002. Inhibition of mild steel corrosion by some macrocyclic compounds in hot and concentrated hydrochloric acid. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 73: 118-122. DOI:10.1016/S0254-0584(01)00374-1 (  0) 0) |

Roković, M. K., Kvastek, K., Horvat-Radošević, V. and Duić, L. J., 2007. Poly (ortho-ethoxyaniline) in corrosion protection of stainless steel. Corrosion Science, 49(6): 2567-2580. DOI:10.1016/j.corsci.2006.12.010 (  0) 0) |

Sai, Ram M. and Palaniappan, S., 2004. A process for the preparation of polyaniline salt doped with acid and surfactant groups using benzoyl peroxide. Journal of Materials Science, 39(9): 3069-3077. DOI:10.1023/B:JMSC.0000025834.43498.cf (  0) 0) |

Sathiyanarayanan, S., Balakrishnan, K., Dhawan, S. K. and Trivedi, D. C., 1994. Prevention of corrosion of iron in acidic media using poly (o-methoxy-aniline). Electrochimica Acta, 39(6): 831-837. DOI:10.1016/0013-4686(94)80032-4 (  0) 0) |

Sazou, D., 2001. Electrodeposition of ring-substituted polyani-lines on Fe surfaces from aqueous oxalic acid solutions and corrosion protection of Fe. Synthetic Metals, 118: 133-147. DOI:10.1016/S0379-6779(00)00399-4 (  0) 0) |

Sazou, D. and Christos, G., 1997. Formation of conducting polyaniline coatings on iron surfaces by electropolymerization of aniline in aqueous solutions. Journal of Electro-analytical Chemistry, 429: 81-93. DOI:10.1016/S0022-0728(96)05019-X (  0) 0) |

Shah, K. and Iroh, J., 2002. Electrochemical synthesis and corrosion behavior of poly (N-ethyl aniline) coatings on Al-2024 alloy. Synthetic Metals, 132(1-2): 35-41. (  0) 0) |

Shen, G. X., Chen, Y. C. and Lin, C. J., 2005. Corrosion protection of 316 L stainless steel by a TiO2 nanoparticle coating prepared by sol-gel method. Thin Solid Films, 489(1-2): 130-136. DOI:10.1016/j.tsf.2005.05.016 (  0) 0) |

Söylev, T. A. and Richardson, M. G., 2008. Corrosion inhibitors for steel in concrete: State-of-the-art report. Construction and Building Materials, 22(4): 609-622. DOI:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2006.10.013 (  0) 0) |

Suryanarayana, C., Rao, K. C. and Kumar, D., 2008. Preparation and characterization of microcapsules containing linseed oil and its use in self-healing coatings. Progress in Organic Coatings, 63(1): 72-78. DOI:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2008.04.008 (  0) 0) |

Tale, A., Passiniemi, P., Forsen, O. and Ylaaari, S., 1997. Polyaniline/epoxy coatings with good anti-corrosion properties. Synthetic Metals, 85: 1333-1334. DOI:10.1016/S0379-6779(97)80258-5 (  0) 0) |

Tallman, D. E., Spinks, G., Dominis, A. and Wallace, G. G., 2002. Electroactive conducting polymers for corrosion control. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry, 6(2): 73-84. DOI:10.1007/s100080100212 (  0) 0) |

Tang, J. S., Jing, X. B., Wang, B. C. and Wang, F. S., 1988. Infrared spectra of soluble polyaniline. Synthetic Metals, 24: 231-238. DOI:10.1016/0379-6779(88)90261-5 (  0) 0) |

Shinde, V., Sainkar, S. R. and Patil, P. P., 2005. Corrosion protective poly (o-toluidine) coatings on copper. Corrosion Science, 47(6): 1352-1369. DOI:10.1016/j.corsci.2004.07.041 (  0) 0) |

Wang, T. and Tan, Y. J., 2006. Understanding electrodeposition of polyaniline coatings for corrosion prevention applications using the wire beam electrode method. Corrosion Science, 48(8): 2274-2290. DOI:10.1016/j.corsci.2005.07.012 (  0) 0) |

Weng, C. J., Chang, C. H., Peng, C. W., Chen, S. W., Yeh, J. M., Hsu, C. L. and Wei, Y., 2011. Advanced anticorrosive coatings prepared from the mimicked xanthosoma sagitti-folium-leaf-like electroactive epoxy with synergistic effects of superhydrophobicity and redox catalytic capability. Chemistry of Materials, 23(8): 2075-2083. DOI:10.1021/cm1030377 (  0) 0) |

Wessling, B., 1994. Passivation of metals by coating with polyaniline: Corrosion potential shift and morphological changes. Advanced Materials, 6(3): 226-228. DOI:10.1002/adma.19940060309 (  0) 0) |

Wessling, B. and Joerg, P., 1999. Corrosion prevention with an organic metal (polyaniline): Corrosion test results. Electrochimica Acta, 44(12): 2139-2147. DOI:10.1016/S0013-4686(98)00322-3 (  0) 0) |

Xing, C. J., Zhang, Z. M., Yu, L. M., Zhang, L. J. and Bowmaker, G. A., 2014. Electrochemical corrosion behavior of carbon steel coated by polyaniline copolymers micro/ nanostructures. RSC Advances, 4(62): 32718-32725. DOI:10.1039/C4RA05826G (  0) 0) |

Yağan, A., Pekmez, N. Ö. and Yildiz, A., 2005. Electropoly-merization of poly (N-methylaniline) on mild steel: Synthesis, characterization and corrosion protection. Journal of Electro-analytical Chemistry, 578(2): 231-238. DOI:10.1016/j.jelechem.2004.12.039 (  0) 0) |

Yağan, A., Pekmez, N. Ö. and Yildiz, A., 2007. Investigation of protective effect of poly (N-ethylaniline) coatings on iron in various corrosive solutions. Surface and Coatings Technology, 201(16-17): 7339-7345. DOI:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2007.01.047 (  0) 0) |

Yağan, A., Pekmez, N. Ö. and Yildiz, A., 2006. Corrosion inhibition by poly (N-ethylaniline) coatings of mild steel in aqueous acidic solutions. Progress in Organic Coatings, 57(4): 314-318. DOI:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2006.09.010 (  0) 0) |

Yang, X. G., Li, B., Wang, H. Z. and Hou, B. R., 2010. Anti-corrosion performance of polyaniline nanostructures on mild steel. Progress in Organic Coatings, 69(3): 267-271. DOI:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2010.06.004 (  0) 0) |

Yu, D. Y. and Tian, J. T., 2014. Superhydrophobicity: Is it really better than hydrophobicity on anti-corrosion?. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 445: 75-78. (  0) 0) |

Yun, H., Li, J., Chen, H. B. and Lin, C. J., 2007. A study on the N-, S- and Cl-modified nano-TiO2 coatings for corrosion protection of stainless steel. Electrochimica Acta, 52(24): 6679-6685. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2007.04.078 (  0) 0) |

Zalewska, T., Lisowska-Oleksiak, A., Biallozor, S. and Jasulaitiene, V., 2000. Polypyrrole films polymerised on a nickel substrate. Electrochimica Acta, 45: 4031-4040. DOI:10.1016/S0013-4686(00)00497-7 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, F., Chen, S. G., Dong, L. H., Lei, Y. H., Liu, T. and Yin, Y. S., 2011. Preparation of superhydrophobic films on titanium as effective corrosion barriers. Applied Surface Science, 257(7): 2587-2591. DOI:10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.10.027 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Y. X., Zhao, M., Zhang, J. X., Shao, Q., Li, J. F., Li, H., Lin, B., Yu, M. Y., Chen, S. G. and Guo, Z. H., 2018. Excellent corrosion protection performance of epoxy composite coatings filled with silane functionalized silicon nitride. Journal of Polymer Research, 25(5): 130-142. DOI:10.1007/s10965-018-1518-2 (  0) 0) |

Zhang, Z. M. and Wan, M. X., 2002. Composite films of nanostructured polyaniline with poly (vinyl alcohol). Synthetic Metals, 128: 83-89. DOI:10.1016/S0379-6779(01)00669-5 (  0) 0) |

Zhu, Y., Ren, G. Q., Wan, M. X. and Jiang, L., 2009. 3D hollow microspheres assembled from 1D polyaniline nanowires through a cooperation reaction. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics, 210(23): 2046-2051. DOI:10.1002/macp.200900317 (  0) 0) |

Zhu, Y., Zhang, J., Zheng, Y., Huang, Z., Feng, L. and Jiang, L., 2006. Stable, superhydrophobic, and conductive polyaniline/polystyrene films for corrosive environments. Advanced Functional Materials, 16(4): 568-574. DOI:10.1002/adfm.200500624 (  0) 0) |

2019, Vol. 18

2019, Vol. 18