2) Laboratory for Marine Fisheries Science and Food Production Processes, Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Qingdao 266237, China

The Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas, is one of the most important commercial mollusks worldwide because of its rapid growth and strong adaptability. Oyster breeding programs in various countries had made mass contributions to increase yield and support the sustainability of the oyster industry. However, spawning of the oyster during the reproductive season can reduce meat quality (Desrosiers et al., 1993) and render it unmarketable. This limited the supply of oysters throughout the year and further expanded production of new oyster varieties with improved traits.

Unlike diploid shellfish, triploid shellfish does not have the reproductive characteristics of massive ovulation in summer, which might increase its yield (Guo, 1994; Benfey, 1999). Triploid oysters can improve its marketability and meat quality due to the decrease of gonadogenesis during the reproductive season (Nell, 2002; Qin et al., 2018). In addition, triploidy can potentially produce oysters with excellent production performance by decreasing reproductive effort (Nell, 2002; Nell and Perkins, 2005; Buestel et al., 2009; Jeung et al., 2016; Qin et al., 2019; Wadsworth et al., 2019).

Triploidy with reduction of gametogenesis is thought to have more energy for growth; however, the superiority in yield of triploid shellfish over diploid shellfish has not been demonstrated in all cases. Wadsworth et al. (2019) found that about 35% of the experiments with chemically induced triploids had no growth advantage than diploids. It is widely believed that ploidy differences affect growth; however, the growth of triploids formed by inhibiting the release of different polar bodies is also different (Stanley et al., 1984; Hawkins et al., 1994). Retaining the first polar body (PB I) can increase gene heterozygosity compared to oysters inhibiting the second polar body (PB II), and whether the additional set of chromosomes comes from homologous chromosomes or non-homologous chromosomes in triploids can influence its performance (Zouros et al., 1988; Wang et al., 2002; Callam et al., 2016). In addition, environmental conditions are also an important aspect. The comparison of triploid and diploid performances is also influenced by their living environmental conditions (Cheney et al., 2000; Smith et al., 2000; Garnier-Géré et al., 2002; Callam et al., 2016). In order to increase the variety of oyster strains and exploit the commercial value of shell color, a breeding program for C. gigas was launched in 2010. After a 6-generation selection, using shell color and shell height as breeding traits, a new strain of C. gigas 'Haida No. 2' with golden shell color and excellent growth performance has been developed (Ge et al., 2015). In order to develop triploid C. gigas 'Haida No. 2', we investigated the effects of triploidy induction on the overall growth, survival and triploid rate of C. gigas 'Haida No. 2' at different developmental stages in the present study.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Parental AnimalsTwo hundred adult individuals of C. gigas 'Haida No. 2' (shell height > 80 mm) that were farmed at Sanggou Bay, China were selected as broodstock. The broodstock were transferred to hatchery for 2 – 3 months to promote gonadal maturation before the experiments. The broodstock were kept in a warm seawater tank (24℃ ± 1℃) for at least 7 days prior to strip-spawning.

2.2 Gametes PreparationThe C. gigas 'Haida No. 2' broodstock were randomly selected. Eggs were collected by 20-μm nylon mesh, and sieved through 80-μm nylon mesh to remove tissue debries and impurities. Collected eggs were suspended in filtered seawater (FSW, with a salinity of 32 practical salinity unit; and a temperature of 24℃ ± 0.5℃) until most of the eggs were near spherical. Sperms were obtained by strip spawning 10 min before insemination. Sperms were sieved through 50-μm nylon mesh and suspended in filtered seawater (FSW).

2.3 Fertilization and TreatmentSix females and three males were used in the experiment. All eggs were pooled before fertilization. The ratio of sperm to egg was adjusted as approximately 50:1. For different triploid induction treatments, the fertilized eggs were equally divided into four groups with different treatments: (A) Cytochalasin B (CB), 0.5 mg L−1 at 10 min post-insemination for 15 min; (B) CB, 0.5 mg L−1 at 15 min post-insemination for 20 min; and (C) CB, 0.7 mg L−1, at 15 min post-insemination for 20 min; and (D) the control group without any CB treatment. For every treatment, three replicates were set up. After the treatment, CB was thoroughly washed off the embryos, and the embryos were rinsed in dimethyl sulfoxide (1 mL L−1) before they were transferred to 60 L tanks.

2.4 Larval Rearing and Spat Grow-outThe D-larvae from every treatment group were collected at 24-h post-insemination and reared in two tanks (60 L) for the measurement of triploid and survival rates, respectively. The initial larval density of each tank was controlled at 5 larvae mL −1. The larvae were reared according to a previously reported culture procedures (Li et al., 2011). When at least 50% of larvae exhibited eyespots, a string of scallop shells was placed in each tank as substrates for settlement. The spats were cultivated in a pond for 1 month before transferred to the oyster farm at Ailian Bay, Rongcheng City, China.

2.5 Ploidy AnalysisThe triploid rate of larvae was examined at 7, 14, 21 and 27 days by flow cytometry during the larval period. Before detection, approximately 300 larvae were collected into a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube and centrifuged gently (300 g) to remove supernatant. Then 1 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS, with the pH of 7.4) was added to the tube to suspend the larvae. Larvae were then disaggregated by gentle repeated pipetting with a 1.5 mL syringe. Cell suspensions sieved by 50-μm nylon mesh and were fixed by cold ethanol. After propidium iodide staining for 30 min, the ploidy level of the fixed cells was analyzed by flow cytometry (Beckman CytoFLEX). Gill fragments were sampled from at least 90 individuals per treatment for flow cytometry at days 120, 330 and 450 until 30 triploid oysters were detected. The shell height and wet weight of each individual were measured. Each individual was labeled with a waterproof label before ploidy was detected.

2.6 Data AnalysisThe survival and growth parameters of larvae were measured according to Kong et al. (2016). The survival and growth parameters were estimated at juvenile and adult stages. From the control and three treatment groups, 90 individuals were randomly selected to estimate survival rate at days 120, 330 and 450. SPSS statistical package 23.0 was used for statistical analysis. P < 0.05 represented significant statistical difference.

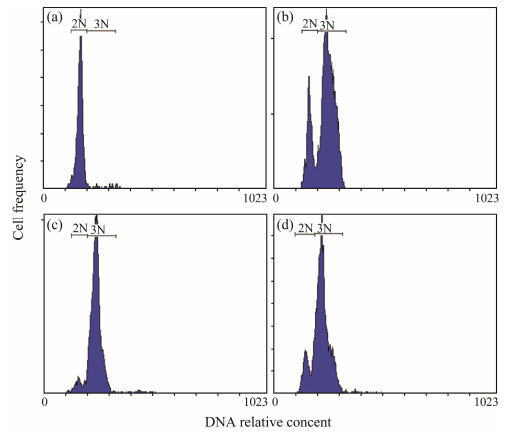

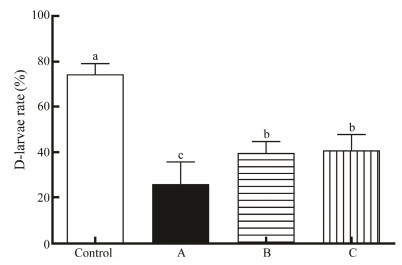

3 Results 3.1 Triploidy, Growth and Survival of LarvaeIn the flow cytometry, the larvae from the control group had only a clear peak of diploid, while diploid and triploid larvae from the treatment groups could be visibly distinguished (Fig.1). The D-larvae rates of the control, treatment A, treatment B and treatment C groups were 74.53%, 25.67%, 39.70% and 40.90%, respectively (Fig.2). The D-larvae rates of the three treatment groups were significantly lower than that of the control group (P < 0.05). The D-larvae rate of treatment A group was significantly lower than those of the treatment B and treatment C groups (P < 0.05), but the D-larvae rate difference between the treatment B and treatment C groups was not significant.

|

Fig. 1 Ploidy composition of larvae samples of control group (a), treatment A (b), treatment B (c) and treatment C (d), measured by flow cytometry. 2N, diploids; 3N, triploids. |

|

Fig. 2 C. gigas 'Haida No. 2' D-larvae rates of the control group, and treatment A, treatment B and treatment C groups. Different lowercase letters denote significant difference (P < 0.05). |

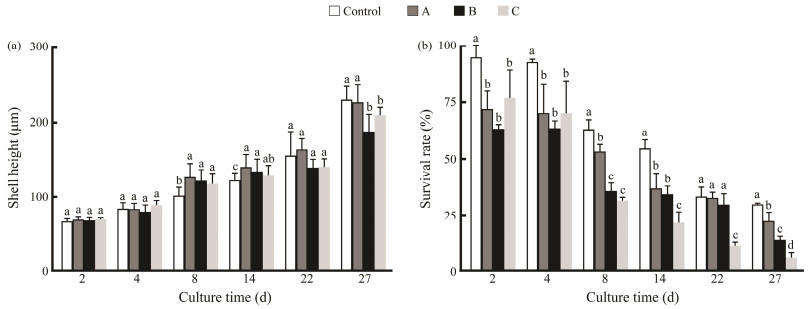

As for growth performance, the shell height between the three treatment groups and the control group showed a significant difference at day 8 (Fig.3). At day 27, the shell height of the larvae reached 231.87 μm in the control group and 229.38 μm in the treatment A group, which were significantly higher than that of the treatment B group (188.25 μm) and treatment C group (210.13 μm) (P < 0.05). During the larval stage, the survival rate of all groups decreased significantly, but the survival rate of the three treatment groups was significantly lower than that of the control group except at day 22. The control group showed the highest survival rate (29.79%), while the lowest value was observed in the treatment B group (6.20%) at day 27.

|

Fig. 3 Shell height (a) and survival rate (b) of C. gigas 'Haida No. 2' larvae from the treatment A, the treatment B and the treatment C groups. Different lowercase letters denote significant difference (P < 0.05). |

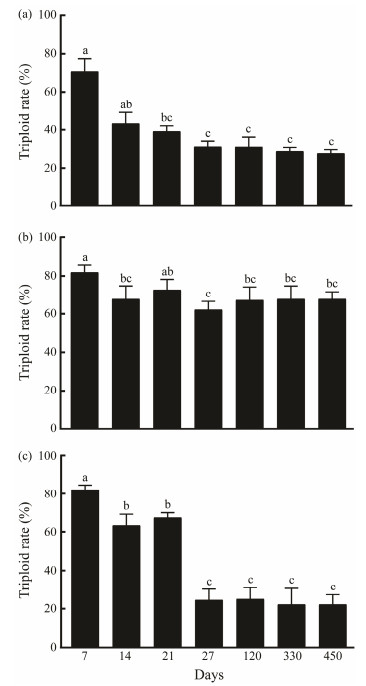

For all treatment groups, the critical period where the triploid rate decreased significantly was the larval stage. During this stage, the triploid rate decreased to 31.22% in the treatment A group, 62.16% in the treatment B group and 24.54% in the treatment C group (Fig.4). Compared with treatment A and treatment C groups, the treatment B group had the higher stability of triploid rate in the larval stage. However, no significant change was observed in all treatment groups in juvenile and adult stages.

|

Fig. 4 Variations of the triploid rate in the treatment A (a), treatment B (b) and treatment C (c) groups. Different lowercase letters denote significant difference (P < 0.05). |

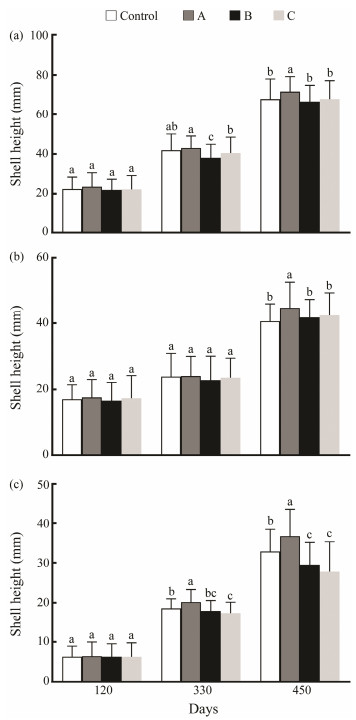

The shell height and shell length of the triploid oysters in the group A were significantly higher than those of the other two treatment groups and the control group at day 450 (P < 0.05) (Fig.5). The wet weight of the diploid oysters in the control group and triploid oysters in the three treatment groups showed no significant difference at day 120. At day 330, the wet weight of diploid oysters from the control group was higher than that of the triploid oysters from the treatment C groups, but lower than that of the triploid oysters in the treatment A group (P < 0.05). The wet weight at day 450 showed a similar pattern to that of day 330, with higher wet weight observed in the treatment A group compared to the other groups.

|

Fig. 5 Growth in shell height (a), shell length (b) and wet weight (c) of triploid and diploid juveniles and adults of C. gigas 'Haida No. 2'. A, triploids from the treatment A group; B, triploids from the treatment B group; C, triploids from the treatment C group. Different lowercase letters denote significant difference (P < 0.05). |

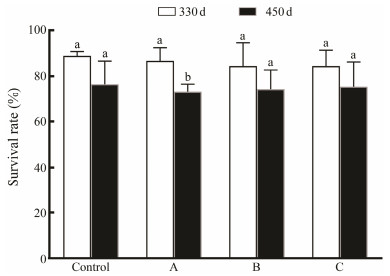

The survival rate between the three treatment groups and the control group was not different significantly at days 330 and 450. At days 330 and 450, the survival rate decreased from 88.89% to 76.67% in the control group, from 86.67% to 73.33% in the treatment A group, from 84.44% to 74.44% in the treatment B group, and from 85.56% to 75.56% in the treatment C group (Fig.6). At day 450, only treatment A group had a significant reduction in survival rate (P < 0.05). The shell color of the juveniles and adults from all groups was golden and aligned with their parents.

|

Fig. 6 Survival rate of C. gigas 'Haida No. 2' juveniles and adults from the treatment A, the treatment B and the treatment C groups. Different lowercase letters denote significant difference (P < 0.05). |

Triploid oysters have been widely used in the oyster culture industry for a few decades in several countries. However, the effects of triploidy induction on production performance of selectively bred strains of the oyster are rarely reported. In order to obtain triploid oysters with outstanding traits, the development of triploid oysters from the selective bred varieties currently is necessary.

In our study, the D-larvae rate in the control group was significantly higher than those of the three treatment groups, which clearly demonstrated that triploidy induction significantly reduced the D-larvae rate of C. gigas 'Haida No. 2'. This is consistent with previous findings (Gerard et al., 1994; Gérard et al., 1999; Supan et al., 2000). The D-larvae rates of the treatment B and C groups were significantly higher than that of the treatment A group. This might be more likely attributed to the case that some of the triploid oysters in the treatment A group were derived from the retaining PB I, as retaining PB I can cause lower survival rate compared to inhibition of PB II (Gérard et al., 1999). In addition, blocking PB I may cause abnormalities in chromosome segregation, resulting in a large number of aneuploidy (Guo et al., 1992).

During the larval stage, the survival and triploid rates in the three experiment groups decreased significantly, which was caused by treatment with high CB concentration. Similar results were observed in in a previous study (Melo et al., 2015). Significant differences in the stability of triploid rate among the three treatment groups were also observed. The triploid rate stability of the treatment A group was lower than that of the treatment B group. One possible reason is that treatment A group has massive aneuploidy that is likely to cause this change of ploidy rate, considering aneuploid and triploid have similar chromosome numbers and are often difficult to distinguish by flow cytometry. Aneuploids had higher mortality than normal triploidy, which reduced the triploid rate stability of treatment A group. The differences in CB concentration contributed to the differences in the triploid rate stability between the treatment B group and the treatment C group. The reason is that the treatment C group with high CB concentration led to a high mortality, which caused a significant decrease in the triploid rate. we observed a difference in shell height between the treatment B group and the control group, which agreed with previous studies (Desrosiers et al., 1993; Toro et al., 1995; Yang and Guo 2006). These results support that the rapid growth of triploid is the results of the reduction of gametogenesis. There is no gonadal development in the larval stage, so the triploids may devote almost the same amount of energy for growth as the diploid larvae (Allen and Downing, 1986). Another explanation is that triploid oysters fail to adapt to aberrant chromosomes.

Significant differences in survival rate of juveniles and adults between the three experiment groups and the control group were not observed. However, some studies found that the survival rate of triploid oysters was higher than diploid oysters, and the reason might be that the reduction of gametogenesis allowed it to maintain higher resistance ability during the summer (Gagnaire et al., 2006; Houssin et al., 2019). Therefore, the factors reducing reproductive development could also reduce mortality. In our current study, the food available caused by excessive aquaculture was relatively limited in Ailian Bay. Most triploid oysters are sterile, and the limited food availability is more beneficial to increasing the survival rate of diploid oysters by hindering reproductive development, thus the significant difference in survival rate of juveniles and adults between the three experiment groups and the control group was not observed. The wet weight of triploids in treatment A group was higher than those in the treatment B and C groups. Compared with triploid oysters from the other groups, a portion of triploid oysters in the treatment A group derived from the blocking PB I. Triploid oysters from the blocking PB I had a higher heterozygosity than those from the blocking PB II. One potential explanation is that the increase of gene heterozygosity resulted in heterosis and improved its growth (Stanley et al., 1984). Heterosis acts as a mechanism to improve the whole tissue weight in oysters (Hedgecock et al., 2007). Compared with the larval stage, the triploid rates of the three experiment groups showed no significant difference in the juvenile and adult stages. This might be related to the low mortality in these two stages.

5 ConclusionsThe triploid rates of C. gigas 'Haida No. 2' in the three treatment groups significantly decreased only in the larval stage and the stability of triploid rates under different induction conditions were significantly different. The wet weight of triploid oysters from treatment A group was higher than that of diploid oysters from the control group and triploid oysters from the other two treatment groups after day 330. Meanwhile, the shell color of all triploid adults of C. gigas 'Haida No. 2' was golden. Thus, the study also indicated developing triploid oysters has the potential to increase the yield of C. gigas 'Haida No. 2' without modifying golden shell color.

AcknowledgementsThis work was supported by the grants from the China Agriculture Research System Project (No. CARS-49), and the Earmarked Fund for Agriculture Seed Improvement Project of Shandong Province (Nos. 2020LZGC016, 2021 LZGC027).

Allen Jr., S. K., and Downing, S. L., 1986. Performance of triploid Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg). I. Survival, growth, glycogen content, and sexual maturation in yearlings. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 102: 197-208. DOI:10.1016/0022-0981(86)90176-0 (  0) 0) |

Benfey, T. J., 1999. The physiology and behavior of triploid fishes. Reviews in Fisheries Science, 7: 39-67. DOI:10.1080/10641269991319162 (  0) 0) |

Buestel, D., Ropert, M., Prou, J., and Goulletquer, P., 2009. History, status, and future of oyster culture in France. Journal of Shellfish Research, 28: 813-820. DOI:10.2983/035.028.0410 (  0) 0) |

Callam, B. R., Allen Jr., S. K., and Frank-Lawale, A., 2016. Genetic and environmental influence on triploid Crassostrea virginica grown in Chesapeake Bay: Growth. Aquaculture, 452: 97-106. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.10.027 (  0) 0) |

Cheney, D. P., 2000. Summer mortality of Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg): Initial finding on multiple environmental stressors in Puget Sound, Washington, 1998. Journal of Shellfish Research, 19: 353-359. (  0) 0) |

Desrosiers, R. R., Gérard, A., Peignon, J. M., Naciri, Y., Dufresne, L., Morasse, J., et al., 1993. A novel method to produce triploids in bivalve molluscs by the use of 6-dimethylaminopurine. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 170: 29-43. DOI:10.1016/0022-0981(93)90127-A (  0) 0) |

Garnier-Géré, P. H., Naciri-Graven, Y., Bougrier, S., Magoulas, A., Héral, M., Kotoulas, G., et al., 2002. Influences of triploidy, parentage and genetic diversity on growth of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas reared in contrasting natural environments. Molecular Ecology, 11: 1499-1514. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01531.x (  0) 0) |

Ge, J. L., 2015. Selective breeding and genetic analysis of shell color traits in the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. PhD thesis. Ocean University of China (in Chinese with English abstract).

(  0) 0) |

Gérard, A., Ledu, C., Phélipot, P., and Naciri-Graven, Y., 1999. The induction of MI and MII triploids in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas with 6-DMAP or CB. Aquaculture, 174: 229-242. DOI:10.1016/S0044-8486(99)00032-0 (  0) 0) |

Gerard, A., Naciri, Y., Peignon, J. M., Ledu, C., and Phelipot, P., 1994. Optimization of triploid induction by the use of 6-DMAP for the oyster Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg). Aquaculture Research, 25: 709-719. (  0) 0) |

Guo, X. M., and Allen Jr., S. K., 1994. Reproductive potential and genetics of triploid Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg). The Biological Bulletin, 187: 309-318. DOI:10.2307/1542288 (  0) 0) |

Guo, X. M., Cooper, K., Hershberger, W. K., and Chew, K. K., 1992. Genetic consequences of blocking polar body I with cytochalasin B in fertilized eggs of the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas: I. Ploidy of resultant embryos. The Biological Bulletin, 183: 381-386. (  0) 0) |

Hawkins, A. J. S., Day, A. J., Gérard, A., Naciri, C., Ledu, C., Bayne, B. L., et al., 1994. A genetic and metabolic basis for faster growth among triploids induced by blocking meiosis I but not meiosis II in the larviparous European flat oyster, Ostrea edulis L. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 184: 21-40. DOI:10.1016/0022-0981(94)90164-3 (  0) 0) |

JHoussin, M., Trancart, S., Denechere, L., Oden, E., Adeline, B., Lepoitevin, M., et al., 2019. Abnormal mortality of triploid adult Pacific oysters: Is there a correlation with high gametogenesis in Normandy, France?. Aquaculture, 505: 63-71. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.02.043 (  0) 0) |

Jeung, H. D., Keshavmurthy, S., Lim, H. J., Kim, S. K., and Choi, K. S., 2016. Quantification of reproductive effort of the triploid Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas raised in intertidal rack and bag oyster culture system off the west coast of Korea during spawning season. Aquaculture, 464: 374-43809. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.07.010 (  0) 0) |

Kong, L. F., Song, S. L., and Li, Q., 2017. The effect of interstrain hybridization on the production performance in the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Aquaculture, 472: 44-49. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.07.018 (  0) 0) |

Li, Q., Wang, Q. Z., Liu, S. K., and Kong, L. F., 2011. Selection response and realized heritability for growth in three stocks of the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas. Fisheries Science, 77: 643-648. DOI:10.1007/s12562-011-0369-0 (  0) 0) |

Melo, E. M. C., Gomes, C. H. A. M., Silva, F. C. D., Sühnel, S., and Melo, C. M. R. D., 2015. Chemical and physical methods of triploidy induction in Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg, 1793). Boletim do Instituto de Pesca, 414: 889-898. (  0) 0) |

Nell, J. A., 2001. The history of oyster farming in Australia. Marine Fisheries Review, 63: 14-25. (  0) 0) |

Nell, J. A., 2002. Farming triploid oysters. Aquaculture, 210: 69-88. DOI:10.1016/S0044-8486(01)00861-4 (  0) 0) |

Nell, J. A., and Perkins, B., 2005. Studies on triploid oysters in Australia: Farming potential of all-triploid Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas (Thunberg), in Port Stephens, New South Wales, Australia. Aquaculture Research, 36: 530-536. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01229.x (  0) 0) |

Qin, Y. P., Zhang, Y. H., Ma, H. T., Wu, X. W., Xiao, S., Li, J., et al., 2018. Comparison of the biochemical composition and nutritional quality between diploid and triploid Hong Kong oysters, Crassostrea hongkongensis. Frontiers in physiology, 9: 1674. DOI:10.3389/fphys.2018.01674 (  0) 0) |

Qin, Y. P., Zhang, Y. H., Mo, R. G., Zhang, Y., Li, J., Zhou, Y. L., et al., 2019. Influence of ploidy and environment on grow-out traits of diploid and triploid Hong Kong oysters Crassostrea hongkongensis in southern China. Aquaculture, 507: 108-118. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.04.017 (  0) 0) |

Smith, I. R., Nell, J. A., and Adlard, R., 2000. The effect of growing level and growing method on winter mortality, Mikrocytos roughleyi, in diploid and triploid Sydney rock oysters, Saccostrea glomerata. Aquaculture, 185: 197-205. DOI:10.1016/S0044-8486(99)00350-6 (  0) 0) |

Stanley, J. G., Hidu, H., and Allen Jr., S. K., 1984. Growth of American oysters increased by polyploidy induced by blocking meiosis I but not meiosis II. Aquaculture, 37: 147-155. DOI:10.1016/0044-8486(84)90072-3 (  0) 0) |

Supan, J. E., Wilson, C. E., and Allen Jr., S. K., 2000. The effect of cytochalasin B dosage on the survival and ploidy of Crassostrea virginica (Gmelin) larvae. Journal of Shellfish Research, 19: 125-128. (  0) 0) |

Toro, J. E., Sanhueza, M. A., Paredes, L., and Canello, F., 1995. Induction of triploid embryos by heat shock in the Chilean northern scallop Argopecten purpuratus Lamarck, 1819. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 29: 101-105. DOI:10.1080/00288330.1995.9516644 (  0) 0) |

Wadsworth, P., Wilson, A. E., and Walton, W. C., 2019. A metaanalysis of growth rate in diploid and triploid oysters. Aquaculture, 499: 9-16. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.09.018 (  0) 0) |

Wang, Z. P., Guo, X. M., Allen Jr., S. K., and Wang, R. C., 2002. Heterozygosity and body size in triploid Pacific oysters, Crassostrea gigas Thunberg, produced from meiosis II inhibition and tetraploids. Aquaculture, 204: 337-348. DOI:10.1016/S0044-8486(01)00845-6 (  0) 0) |

Yang, H. P., and Guo, X. M., 2006. Polyploid induction by heat shock-induced meiosis and mitosis inhibition in the dwarf surfclam, Mulinia lateralis Say. Aquaculture, 252: 171-182. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2005.07.017 (  0) 0) |

Zouros, E., Romero-Dorey, M., and Mallet, A. L., 1988. Heterozygosity and growth in marine bivalves: Further data and possible explanations. Evolution, 42: 1332-1341. DOI:10.2307/2409016 (  0) 0) |

2023, Vol. 22

2023, Vol. 22