White shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) has desirable characteristics including fast growth, strong disease resistance, convenient transportation, a large suitable culture area, and a high yield (Rodríguez et al., 2007). Similarly, razor clam (Sinonovacula constricta) benefits from fast growth and high economic value, and is cultivated widely in coastal areas of China (Liu, 2014). Nutrients transformed from artificial feeding residues and L. vannamei faeces in shrimp culture ponds can be fully utilized by phytoplankton, which helps to accelerate phytoplankton growth. In turn, S. constricta can feed on phytoplankton, organic debris, dissolved organic matter and bacteria in water from shrimp ponds, hence mix-culture of shrimp and shellfish is very popular in China.

For traditional mix-culture models, culture capacity is an important factor, which can decline with disease, and further affect yields (Dong et al., 1998). If the density of shrimps is too high, this can result in a significant increase in uneaten feed remnants and faeces, which decreases the water quality. If the density of shellfish is too high, there may be a significant decline in phytoplankton, which may decrease the growth and health of shrimps (Kai et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2018). In addition, in the case of long-term overcast weather and rain, shellfish may consume most of the phytoplankton, and these microorganisms can struggle to recover when it is sunny again. To solve these problems, some new culture-independent models have been developed to maintain the amount of phytoplankton and the quality of the water, and thereby avoid disease outbreaks (Huang, 2001; Liu, 2014). However, effective circular mix-culture models and optimal culture capacities have not been reported.

To construct an effective circular mix-culture model and investigate its culture capacity, we developed a small culture system with a series of connection including four different culture densities of L. vannamei and S. constricta, and monitored the water quality (nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations), growth indices, and digestive and lipid-soluble antioxidant system (LSAS) enzymes activities. Based on these indices, we identified the optimal culture density, and then established a larger system using the optimal culture density, and monitored water quality, growth indices and yields. The results revealed good growth indices and yields with the optimal culture capacity, providing a reference for future mix-culture models of shrimp and shellfish.

2 Materials and Methods 2.1 Culture Density Selection for the Circular Mix-Culture Model (Trial I)L. vannamei and S. constricta were reared in Ningbo, China. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The Animal Care and Use Committee of Ningbo University approved the protocols.

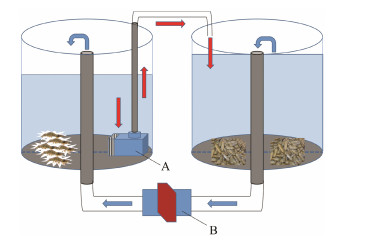

We first constructed a small culture system with a series of connection. L. vannamei and S. constricta were cultured in two independent small plastic tanks (total volume = 10 t, base area = 10 m2; Fig.1) containing 9 tons of filtered seawater in each tank (23℃ ± 1℃, pH 7.89 ± 0.23, dissolved oxygen 6.67 mg L−1 ± 0.33 mg L−1). S. constricta were cultured at the bottom of a substrate sludge tank (about 10 cm height, base area 2.5 m2) which was sunk in the small plastic tank. The water from the L. vannamei tank was delivered to the S. constricta tank by a pump (power 100 W), and the water in the S. constricta tank overflowed back into the L. vannamei tank through a central tube, forming a series of connection between the two independent tanks. There was an air-stone in each tank to supply oxygen, and the water in the S. constricta tank was exchanged completely with water from the L. vannamei tank once a day. We tested four culture densities in the experimental groups (Table 1), and each group included three parallel replicates. The four groups were cultured for 8 weeks (total 56 days). L. vannamei were fed commercial feed (Yuehai, Guangdong, China), and the total amount of feed provided was about 6% of shrimp body weight per day. S. constricta in each tank were fed 2 L of inspissated Chlorella aeruginosa in water (bacterial cell density (8 – 10) × 1010 ind mL−1) twice a day.

|

Fig. 1 Small culture system with a series of connection for L. vannamei and S. constricta. A, pump (power = 100 W); B, valve controlling water flow between the two tanks. The red arrow represents water flow from L. vannamei to S. constricta. The blue arrow represents water flow from S. constricta back to L. vannamei. |

|

|

Table 1 Culture density of the four experimental groups |

Water quality factors (total nitrogen, total phosphorus, ammonium nitrogen, nitrate nitrogen, nitrite nitrogen and active phosphorus) were determined every week according to the marine monitoring standard (GB 12763.4-2007).

For growth indices, we recorded the initial/final weight (IW/FW), and calculated the specific growth rate per day (%) based on the formula:

| $ {\text{Growth rate (%)}} = \frac{{{\text{ln (FW)}} - {\text{ln (IW)}}}}{{{\text{Number of culturing days}}}} \times 100\% . $ |

Four digestive and five LSAS enzymes' activities were measured on the first and final days of trial I using commercial assay kits (Jiancheng Biotechnology Research Institute, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The four digestive enzymes were trypsin, pepsin, lipase and amylase; the five LSAS enzymes were lysozyme, alkaline phosphatase, acid phosphatase, catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD).

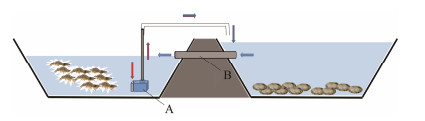

2.3 Construction of the Culture Model with a Series of Connection Using Large Culture Ponds (Trial II)We constructed a similar model using large culture ponds (Fig.2). The effective culturing area of the L. vannamei pond was about 12000 m2 with nanotube oxygenation, and the effective culturing area of the S. constricta pond was about 3000 m2 with a water wheel aerator. The depth of culturing water (23℃ ± 6℃, pH 8.26 ± 1.24, dissolved oxygen 7.24 mg L−1 ± 1.33 mg L−1) was about 1.5 m in the L. vannamei pond and about 0.5 m in the S. constricta pond (earthen bottom). The water in the S. constricta pond was exchanged completely with water from L. vannamei once a day. Based on the results from trial I, we selected the optimal culture density for trial II (averaged from three replicates). Two periods for L. vannamei (about 2 months for both) and one period for S. constricta were tested in the model from June to November (about 4 months). In addition, we included a control involving L. vannamei and S. constricta cultured together in the same pond (about 12000 m2) with the same cell density as that in the model system (trial II).

|

Fig. 2 Culture model with a series of connection for culturing L. vannamei and S. constricta in large ponds. A, pump (power = 1000 W); B, valve controlling water flow between the two ponds. The red arrow represents water flow from L. vannamei to S. constricta. The blue arrow represents water flow from pond with S. constricta back to pond with L. vannamei. |

In trial II of control and experimental groups, water quality factors were determined every 10 days for about 4 months, and initial/final growth indices were calculated as above. The yield was recorded for all cultures and periods.

2.5 Statistical AnalysisStatistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's multiple comparison test (SPSS, version 16.0). The difference was considered significant when P < 0.05.

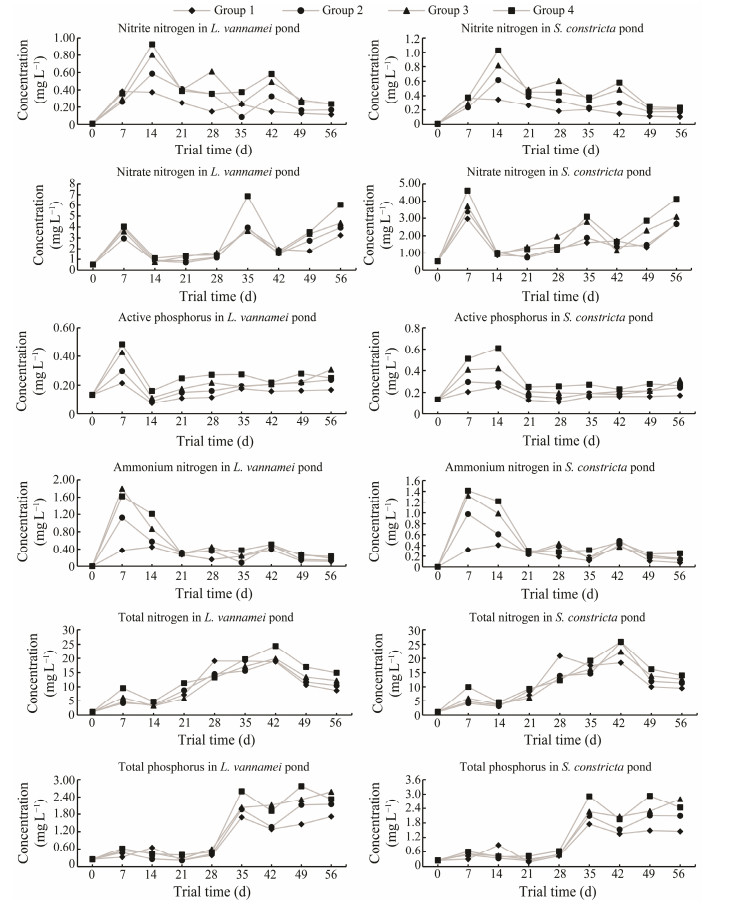

3 Results 3.1 Culture Density Selection Based on Water Quality, Growth Indices and Enzyme Activities from Trial IDuring the 56 days of trial I, we monitored six water quality factors for both L. vannamei and S. constricta culture ponds (Fig.3). Nitrite nitrogen increased in the first 2 weeks, then decreased thereafter. The levels in groups 3 and 4 were much higher than those in groups 1 and 2; however, in the last 2 weeks it was similar in all four groups. Ammonium nitrogen increased in the first week then decreased thereafter. The levels in groups 3 and 4 were much higher than those in groups 1 and 2 in the first 3 weeks; however, in the last 2 weeks it was similar in all four groups. Nitrate nitrogen was increased in the first, fifth and eighth weeks. The level in group 4 was higher than those in the other groups, while it was similar in all four groups in the first 4 weeks. Total nitrogen was increased after 6 weeks then decreased in the last 2 weeks. Active phosphorus was increased in the first 2 weeks then decreased thereafter. The levels in groups 3 and 4 were higher than those in groups 1 and 2 in the first 3 weeks, but after 3 weeks it was similar in all four groups. Total phosphorus was increased after 5 weeks then remained relatively stable thereafter. The levels in groups 3 and 4 were higher than those in groups 1 and 2 after the fifth week, but it was similar in all four groups during the first 4 weeks.

|

Fig. 3 Changes of water quality factors in ponds with L. vannamei and S. constricta. The x-axis represents the days of the trial, and the y-axis represents the levels of water quality factors (mg L−1). |

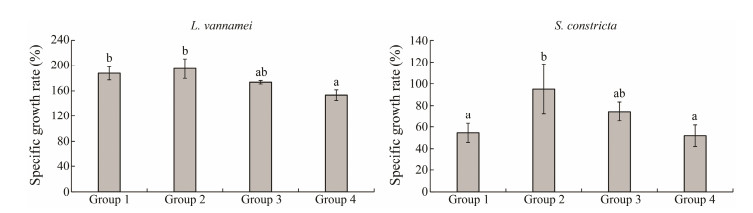

In group 1, the weights of L. vannamei and S. constricta increased from 4.28 g ± 0.20 g to 12.24 g ± 0.64 g and 7.77 g ± 0.12 g to 10.56 g ± 0.67 g, respectively. In group 2, the weights of L. vannamei and S. constricta increased from 4.32 g ± 0.15 g to 12.90 g ± 0.97 g and 7.76 g ± 0.04 g to 13.28 g ± 1.75 g, respectively. In group 3, the weight of L. vannamei and S. constricta increased from 4.35 g ± 0.19 g to 11.5 g ± 0.45 g and 7.81 g ± 0.14 g to 11.85 g ± 0.52 g, respectively. In group 4, the weights of L. vannamei and S. constricta increased from 4.27 g ± 0.16 g to 10.08 g ± 0.26 g and 7.91 g ± 0.13 g to 10.59 g ± 0.59 g, respectively. The specific growth rate per day was the highest in group 2 among the four groups with different culture densities (Fig.4).

|

Fig. 4 Specific growth rate per day for L. vannamei and S. constricta in the four groups. The y-axis is the specific growth rate (%) per day (P < 0.05). |

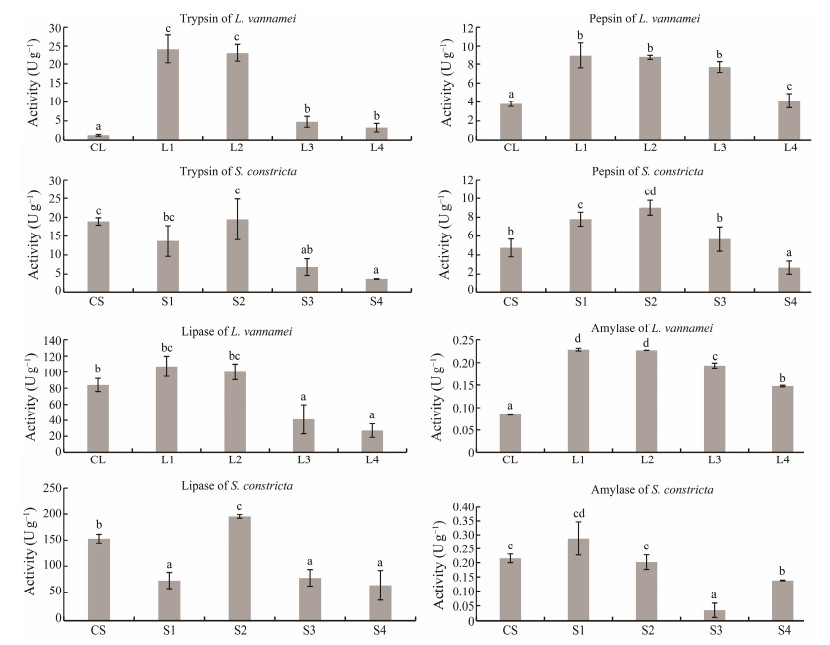

Analyses of digestive enzymes' activities (Fig.5) showed that trypsin activity in L. vannamei was significantly increased in L1 and L2, whereas trypsin activity in S. constricta was significantly decreased in S3/S4. Pepsin activity in L. vannamei was significantly increased in L1, L2 and L3, and pepsin activity in S. constricta was significantly increased in S1 and S2. Lipase activity in L. vannamei was significantly decreased in L3 and L4, and lipase activity in S. constricta was significantly increased in S2. Amylase activity in L. vannamei was significantly increased in L1 and L2. Amylase activity in S. constricta was significantly decreased in S3 and S4. Overall, digestive enzymes in L1 and L2 were more active during the 56 days in trial I.

|

Fig. 5 Changes in the activities of digestive enzymes in L. vannamei and S. constricta. CL, initial L. vannamei values; L1 – 4, final L. vannamei values for groups 1 – 4; CS, initial S. constricta values; S1 – 4, final values for S. constricta in groups 1 – 4 (P < 0.05). |

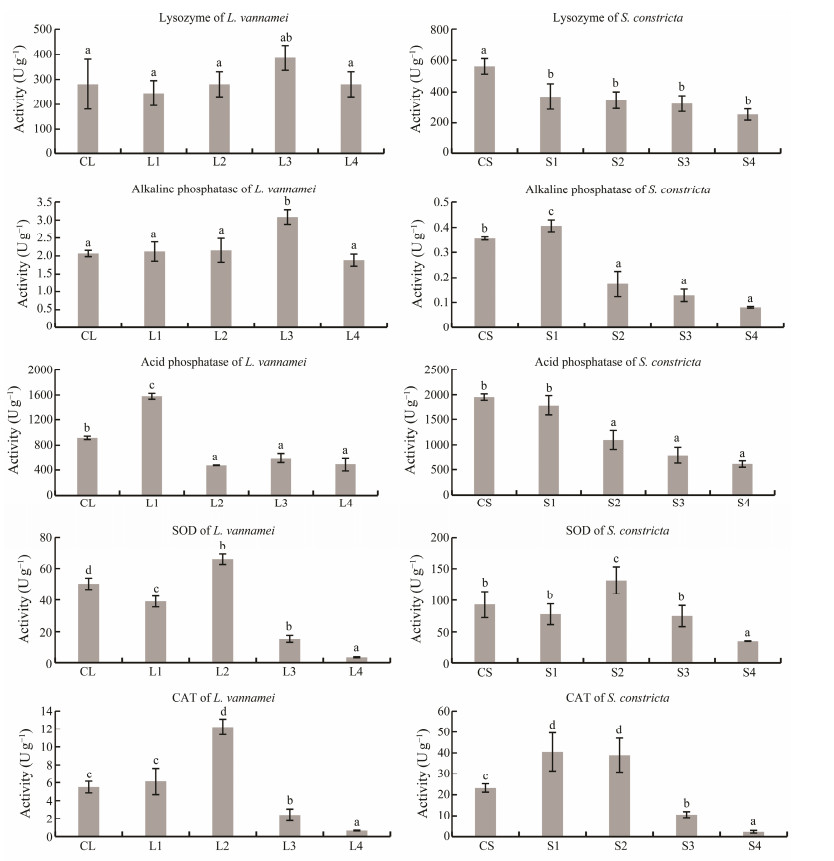

Analysis of immune enzymes (Fig.6) showed that lysozyme activity in L. vannamei was not significantly different, but lysozyme activity in S. constricta was significantly decreased in S1 – 4. Alkaline phosphatase in L. vannamei was significantly increased in L3, while alkaline phosphatase in S. constricta was significantly decreased in S4. Acid phosphatase activity in L. vannamei was significantly increased in L2 – 4, while acid phosphatase activity in S. constricta was significantly decreased in S2 – 4. SOD activity in L. vannamei was significantly increased in L2, while SOD activity in S. constricta was significantly decreased in S2. CAT activity in L. vannamei was significantly increased in L2, and CAT activity in S. constricta was significantly increased in S1 and S2.

|

Fig. 6 Changes in the activities of immune enzymes in L. vannamei and S. constricta. CL, initial values in L. vannamei; L1 – 4, final values in L. vannamei in groups 1 – 4; CS, initial values in S. constricta; S1 – 4, final values for S. constricta in groups 1 – 4 (P < 0.05). |

Based on the water quality measurements, growth indices, and enzyme activities, the culture density of group 2 was selected for trial II.

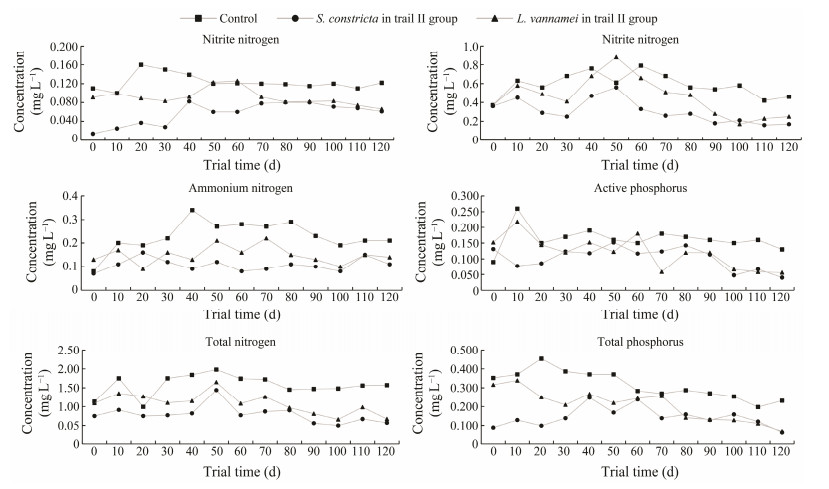

3.2 Water Quality, Growth Indices and Yields for L. vannamei and S. constricta in Trial IIWe set the culture density of L. vannamei and S. constricta in trial II based on group 2 of trial I. During the 120 days of trial II, we monitored six water quality factors in control and trial II groups in L. vannamei and S. constricta ponds (Fig.7). In controls, nitrite nitrogen was increased during the first 20 days then decreased hereafter. In the trial II group, it was raised during the first 2 months then decreased thereafter, but similar in L. vannamei and S. constricta during the last 40 days. Nitrite nitrogen was much higher in controls than in the trial II group after 60 days. In controls, nitrate nitrogen was elevated during the first 60 days then decreased thereafter. In the trial II group, it was raised during the first 50 days then decreased thereafter, and it was similar in L. vannamei and S. constricta during the last 20 days. Nitrate nitrogen was much higher in controls than in the trial II group after 60 days. In controls, ammonium nitrogen was increased during the first 40 days then decreased thereafter. In the trial II group, it was raised during the first 50 days then decreased thereafter. In the last 20 days, it was similar in L. vannamei and S. constricta. Ammonium nitrogen was much higher in controls than in the trial II group after 10 days. In controls, total nitrogen was elevated during the first 50 days then diminished thereafter. In the trial II group, it was raised during the first 50 days, then decreased in subsequent days. In last 40 days, it was similar in L. vannamei and S. constricta. Total nitrogen was much higher in controls than in the trial II group after 20 days. In controls, active phosphorus was raised during the first 10 days then decreased thereafter. In the trial II group, it was raised during the first 50 days then decreased thereafter. In the last 40 days it was similar in L. vannamei and S. constricta. Total nitrogen was much higher in controls than in the trial II group after 70 days. In controls, total phosphorus was elevated during the first 20 days then decreased in subsequent days. In the trial II group, it was raised during the first 40 days then decreased thereafter. In the last month it was similar in L. vannamei and S. constricta. Total phosphorus was higher in controls than the trial II group throughout the experiment.

|

Fig. 7 Changes in water quality factors in control and trial II groups. The x-axis represents the trial days and the y-axis represents the level of water quality factors (mg L−1). |

For controls, the specific growth rate per day during the first period for L. vannamei was 7.01% (0.19 g ± 0.01 g to 12.8 g ±1.78 g); the specific growth rate per day during the second period for L. vannamei was 6.34% (0.31 g ± 0.024 g to 13.88 g ± 1.73 g); the specific growth rate per day for S. constricta was 2.41% (0.19 g ± 0.26 g to 3.41 g ± 0.81 g). The average yield of L. vannamei was 524 g m−2 in one period, and the average yield of S. constricta was 2216 g m−2. In the trial II group, the specific growth rate per day during the first period for L. vannamei was 7.37% (from 0.19 g ± 0.01 g to 15.8 g ± 1.23 g); the specific growth rate per day during the second period for L. vannamei was 6.78% (from 0.31 g ± 0.024 g to 18.1 g ± 2.11 g); the specific growth rate per day for S. constricta was 2.67% (from 0.19 g ± 0.26 g to 4.67 g ± 0.44 g). The average yield of L. vannamei was 701 g m−2 in one period, and the average yield of S. constricta was 6193 g m−2. The growth indices of the trial II group were significantly higher than that of the control (P < 0.05). The yield of L. vannamei was 25.25% higher than that of control, and the yield of S. constricta was 64.22% higher than that of the control.

4 DiscussionNitrogen and phosphorus are important water quality factors for aquaculture that can influence the growth and health of aquatic organisms (Chen et al., 1989; Green and Boyd, 1995). In trial I, nitrogen and phosphorus were typically increased and then decreased. The rise might be due to the instability of the culture model with a series of connection between L. vannamei and S. constricta, and the decline indicates that the water quality was generally stable in this model, consistent with our previous study (Luo et al., 2020). The water quality factors were not very good during the 56 days in trial I compared to the larger system (Wu et al., 2005). The downward trend indicated that this system might be a useful culture model for larger water bodies and longterm culture. The water quality factors were much higher in the high culture density groups (groups 3 and 4), but the growth indices of high culture density groups were lower than those in the low-density groups, which suggests that the optimal culture capacity of this model might be close to group 2.

To further investigate the conditions of L. vannamei and S. constricta in the four culture density groups, we measured digestive and LSAS enzymes' activities. Culture density greatly influenced the digestive enzyme activities of shrimps (Xiao et al., 2012), and digestive enzyme activities in both L. vannamei and S. constricta were higher in the low culture density groups than those in the high-density groups, which suggests that the feed efficiency might be much higher in low culture density groups, facilitating faster growth. Some studies have reported that the levels of several digestive enzymes can vary synchronously, consistent with our results (Franklin, 1950). Among LSAS enzymes, lysozyme hydrolyses bacterial cell walls and acts as a nonspecific innate immunity molecule against the invasion of bacterial pathogen (Bachali et al., 2002; Hikima et al., 2003). Many pollutants in aquatic environments such as heavy metals and high ammonia nitrogen can stimulate the activities of alkaline phosphatase and acid phosphatase (Chen et al., 2019), and we found that the activities of these three enzymes were higher in high culture density groups. Thus, we speculated that high culture density might induce immune reactions in response to high nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations.

We also measured the activities of SOD and CAT, which were higher in low culture density groups. SOD and CAT are LSAS enzymes that remove excessive oxygen free radicals produced in cells, and their activities are related to the immunity of animals and environmental stress (Hernández et al., 2000), which further indicates that high culture density had a negative effect on the immune systems of L. vannamei and S. constricta. Based on these results, the culture density of group 2 was selected for the larger water body in trial II.

To examine the feasibility of the series-connection culture model in productive practice, we scaled it up to a larger water body. In the larger culture model, we found that the changing trends for nitrogen and phosphorus in ponds were similar to those in trial I, but the water quality was much lower in the trial II model, which might be due to the larger water body. Compared with controls, the difference of water quality diminished in the latter stages of trial II, which indicated that the larger culture model achieved higher water quality. In our previous study, we found that the growth of Chlorophyta might be related to nitrogen and phosphorus in water (Luo et al., 2020), hence a rise in these two water quality factors during the initial stages of trial I and II might promote the growth of these phytoplankton, thereby stimulating the growth of S. constricta. The rising trend in trial II might also be due to the higher temperature in July and August, consistent with other studies (Ren and Schiel, 2008), We therefore speculated that the downward trend in these two water quality factors during the latter stages of trial I and II might be due to the rise in phytoplankton in this model.

In addition, phytoplankton in the L. vannamei pond may help the recovery of the population in the S. constricta pond, which may help to maintain the normal growth of S. constricta in sunny days after the overcast weather. Moreover, the growths and yields of L. vannamei and S. constricta were higher than controls in the trial II group. Some studies have reported that high levels of nitrogen and phosphorus can trigger various diseases (Xiao et al., 2012), hence our series-connection culture model could improve water quality and enhance the survival rate and yield of both L. vannamei and S. constricta.

5 ConclusionsIn the present study, we construct a series-connection culture system and found its optimal culture capacity for L. vannamei (40 ind m−2) and S. constricta (300 ind m−2). Our results showed the good growth, health, and high yields when using the optimal culture capacity, providing a reference for future mix-culture models of shrimp and shellfish.

AcknowledgementsThis work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Plan (No. 2019YFD0900400), the Earmarked Fund for Modern Agro-Industry Technology Research System, China (No. CARS-47), and sponsored by the K. C. Wong Magna Fund in Ningbo University.

Bachali, S., Jager, M., Hassanin, A., Schoentgen, F., and Deutsch, J. S., 2002. Phylogenetic analysis of invertebrate lysozymes and the evolution of lysozyme function. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 54(5): 652-664. DOI:10.1007/s00239-001-0061-6 (  0) 0) |

Chen, J. C., Liu, P. C., and Lin, Y. T., 1989. Culture of Penaeus monodon in an intensified system in Taiwan. Aquaculture, 77(4): 319-328. DOI:10.1016/0044-8486(89)90216-0 (  0) 0) |

Chen, S., Yu, Y., Gao, Y., Yin, P., Tian, L., Niu, J., et al., 2019. Exposure to acute ammonia stress influences survival, immune response and antioxidant status of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) pretreated with diverse levels of inositol. Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 89: 248-256. DOI:10.1016/j.fsi.2019.03.072 (  0) 0) |

Dong, S. L., Li, D. S., and Pan, K. H., 1998. On the carrying capacity of mariculture. Journal of Ocean University of Qingdao, 28(2): 253-258 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Franklin, K. J., 1950. Secretory mechanism of the digestive glands. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 26(295): 289-290. DOI:10.1136/pgmj.26.295.289 (  0) 0) |

Green, B. W., and Boyd, C. E., 1995. Chemical budgets for or-ganically fertilized fish ponds in the dry tropics. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 26(3): 284-296. DOI:10.1111/j.1749-7345.1995.tb00257.x (  0) 0) |

Hernández, I., Pérez-Pastor, A., and Lloréns, J., 2000. Ecological significance of phosphomonoesters and phosphomonoesterase activity in a small Mediterranean river and its estuary. Aquatic Ecology, 34(2): 107-117. DOI:10.1023/A:1009930405572 (  0) 0) |

Hikima, S., Hikima, J. I., Rojtinnakorn, J., Hirono, I., and Aoki, T., 2003. Characterization and function of kuruma shrimp lysozyme possessing lytic activity against Vibrio species. Gene, 316(1): 187-195. DOI:10.1016/S0378-1119(03)00761-3 (  0) 0) |

Huang, G., 2001. A new shrimp poly-ponded recirculating polyculture system. Marine Sciences, 25(4): 48-49, 57 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Kai, Z., Li, T. X., Lin, D. S., Jia, D., Jie, F., Peng, H. R., et al., 2015. Nitrogen and phosphorus budgets of polyculture system of Portunus trituberculatus, Litopenaeus vannamei and Ruditapes philippinarum. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 45(2): 44-53 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Liu, Z., 2014. The design and experimental study Sinonovacula constricta farming system with independent feed supply and water storage pond. Fishery Modernization, 41(6): 18-21 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

Luo, Y. H., Li, L. G., Zhao, C. P., Wang, D. L., Xu, S. L., and Xu, J. L., 2020. Relationship between phytoplankton structure and water quality factors in culture pond of Litopenaeus vannamei and Sinonovacula constricta. Oceanologia et Limnologia Sinica, 51(2): 379-387 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.11693/hyhz20191100231 (  0) 0) |

Ren, J. S., and Schiel, D. R., 2008. A dynamic energy budget model: Parameterisation and application to the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas in New Zealand waters. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology & Ecology, 361(1): 42-48. DOI:10.1016/j.jembe.2008.04.012 (  0) 0) |

Rodríguez, S., Regalado, E. M., Pérez, J. C., Pastén, A., and Ibarra, R. S., 2007. Comparison of some reproductive characteristics of farmed and wild white shrimp males Litopenaeus vannamei (Decapoda: Penaeidae). Revista de Biologa Tropical, 55(1): 199. (  0) 0) |

Xiao, M. H., Xiao, Y. P., Wu, Z. Q., and Hu, X. P., 2012. Effects of stocking density on growth, digestive enzyme activities and biochemical indices of juvenile Procambarus clarkii. Journal of Fisheries of China, 36(7): 1088 (in Chinese with English abstract). DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1231.2012.28029 (  0) 0) |

Zhao, Y. B., Lin, Z. H., He, J., and He, L., 2018. The community structure of planktonic ciliates in relation to environmental factors in polyculture-pond. Journal of Biology, 202(2): 47-51, 63 (in Chinese with English abstract). (  0) 0) |

2022, Vol. 21

2022, Vol. 21